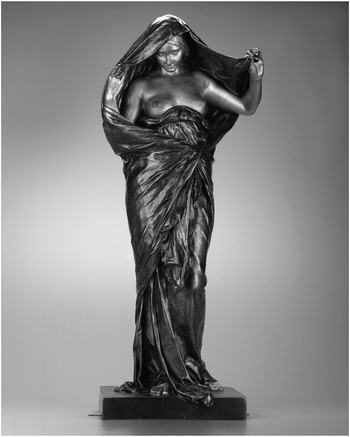

In Boston’s Museum of Fine Arts stands a two-foot-tall bronze statuette of a woman lifting a large mantle over her head, with her face, shoulders, and breasts exposed to the viewer (Fig. I.1). Louis-Ernest Barrias created this replica in 1899, modeling it after a more life-sized marble-and-onyx statue, now in the Musée d’Orsay, that the French government originally commissioned to grace the grand staircase of the Conservatoire National des Arts et Métiers in Paris.Footnote 1 The statue’s title, Nature Unveiling Herself before Science (La Nature se dévoilant), reflects a standard idea of the time in which nature – imagined as a woman – (willingly? reluctantly?) reveals herself to the scientist – figured as male.Footnote 2 The sculpture is an allegory. A woman undressing before the inquisitive gaze of the viewer means something other (the Greek word for “other” is allos – from which we get the word “allegory”). The other, “true” meaning of the sculpture is that nature, which is hidden, reveals its secrets to the scientist.

Fig. I.1. Louis-Ernest Barrias, Nature Unveiling Herself before Science, French, about 1899, bronze, Museum of Fine Arts, Boston, Edwin E. Jack Fund.

As I looked at this sculpture in the Frances Vrachos Gallery of the Museum of Fine Arts, children from a local elementary school filed by, glancing over to glimpse this partially clad woman in bronze. How curious, I thought, to be a child, gaining one’s footing in science class, taking a field trip to the local art museum, and then encountering this late nineteenth-century bronze, which dictates that nature is a half-naked woman unveiling herself before science. I recalled, too, my study in my years as an undergraduate philosophy major, reading about the trope that truth is a woman, hidden among veils. The philosopher – the seeker of truth and lover of wisdom – is he who wields the power of unveiling woman and possessing truth. In the opening paragraph of the preface to his 1886 book, Beyond Good and Evil, Friedrich Nietzsche poses the question: “Supposing truth is woman – what then?” Thus opens his critique of dogmatic philosophers, whom he accuses of being “inexpert about women.” Nietzsche exposes their “gruesome seriousness” and “clumsy obtrusiveness with which they have usually approached truth so far” as just another “awkward and improper method for winning a woman’s heart.”Footnote 3

The trope that nature is a woman who hides or reveals herself has been around for a long time. “Nature loves to hide,” quipped the presocratic philosopher Heraclitus (d. c. 475 BCE). In The Veil of Isis, Pierre Hadot follows the thread of this trope from antiquity to the twentieth century, tracing the genealogy of human attitudes toward nature “solely from the perspective of the metaphor of unveiling.”Footnote 4 Notions and metaphors such as these – the nakedness of truth, the veiling or unveiling of nature – have long influenced how writers have portrayed the pursuit of truth, whether medieval allegorists speculating on the nature of the divine or an Enlightenment-era scientist asserting an objective truth about the natural world.

The present book is about veils in their material and metaphoric sense in the era known as late antiquity. The early chapters consider veils as pieces of cloth used to cover bodies (typically women’s bodies), architectural openings (doorways, windows, peristyles), and other mundane and sacred objects. Among other things, these chapters trace the uses and meanings of veiling in the wider late ancient Mediterranean world, the world that birthed and nurtured the “religions” of Christianity, Judaism, and, by the seventh century, Islam. The last two chapters explore the role of the veil as metaphor in the work of two early Christian thinkers, Origen of Alexandria and Gregory of Nyssa. These late ancient intellectuals helped form the idea that God and God’s Word were veiled, and they built exegetical, ascetic, and theological frameworks around the theory that the properly disciplined Christian could unveil divine truth. In a broad scope, this book seeks to place such allegorical endeavors of early Christian thinkers in a context of veils, textiles, and women’s things. This book explores the practice of veiling in all its social, ritual, gendered, and material complexity. How might we understand Origen’s and Gregory’s allegorical projects if we foreground the veils and textiles that color their writings? What might be illuminated if we “think with” the veil as object, gesture, and metaphor?

Veils as Women’s Things: Allegory and Veiling

Some of the earliest Greek literature depicts veils as “women’s things.” In Homer’s Odyssey, Helen, Hecabe, Andromache, Penelope, Nausicaa, Thetis, Hera, Ino, Circe, and Calypso – mortal and immortal women – wear veils.Footnote 5 The beautiful sea nymph Calypso, whose name means “she who hides” or “she who veils,”Footnote 6 dresses herself after spending the night beside Odysseus:

The young Nausicaa and her girlfriends, after bathing and picnicking on the beach, “threw off their veils” and began playing ball (Od. 6.100). The sea nymph Ino gives Odysseus an immortal, life-saving veil (krēdemnon) when he abandons his raft to swim to shore (Od. 5.346), and Penelope, Odysseus’s wife, held a “shining veil” before her face when she addressed the suitors in her house (Od. 1.334). In Homeric epic, women and girls adjust cloth around their heads and faces in gestures of modesty and allure; they throw off their veils in delight (Nausicaa) or anguish (Andromache). Women conceal and reveal, and the veil is a primary vehicle through which these coverings and revelations occur in the narrative.

The association of women with veiling and the idea that veils are primarily “women’s things” have persisted for many centuries – through Assyrian, Greek, Roman, Byzantine, and medieval times right up to our own – and were widespread over much of the ancient Mediterranean and Western Asian worlds. Lloyd Llewellyn-Jones concludes his study of veiling in ancient Greece with these words: “In Greek culture from the archaic era through to the Roman period, the veiling of women was routine. An ideology of veiling … was probably adhered to by most women in Greek society as a matter of daily practice, at least when they appeared out of doors or at home in the company of strange men.”Footnote 8 Similarly, the idea that nature or truth was hidden behind veils – and that truth required unveiling – was persistent and widespread in the ancient Mediterranean and the various cultures that it nurtured. This idea continues to shape the way that we think about philosophical pursuit, allegorical interpretation, and scientific endeavor to this day.

Plato and his followers understood the role of the philosopher as one who excavates the hidden truths of nature and reality, deciphering between corporeal images and incorporeal forms. It was a first-century Greek Jewish Platonist, Philo of Alexandria, who first harkened back explicitly to Heraclitus’ aphorism that “nature loves to hide.” In his exposition of an allegorical method with which to understand the true meaning of the Jewish scriptures, Philo differentiated between those who dwell on literal interpretations and those who understand that “nature loves to hide,” who search for another, hidden meaning of the biblical text.Footnote 9 The “physical reality designated by the text” points to “spiritual realities that can be conceived as sources in the figurative sense.”Footnote 10 One of the ways that Philo conceived of the difference between physical and spiritual, literal and allegorical, was through images of surface and depth. Taking his cue from an allegorical reading of biblical wells in Genesis, Philo writes that “the well is the symbol of knowledge; for the nature of knowledge is not situated at the surface, but it is deep. It does not sprawl in daylight but loves to hide in secret, and it is not found easily, but with a great deal of difficulty.”Footnote 11 The dynamic play between surface and depth along with the insistence that the plumbing of the depths requires a superior intellect together inform Christian allegorists in the late ancient period. Following Philo’s lead, Christian intellectuals such as Origen of Alexandria and Gregory of Nyssa, for example, both equate the literal reading of the Bible with the surface reading, and they associate this reading with the masses of untrained and undisciplined readers. A deeper, spiritual truth is unveiled only by those who have a disciplined body, mind, and soul.

Medieval European authors inherited the association of allegorical method with veiling and unveiling from their early Christian and Neo-Platonist forefathers. In a work on medieval poetics, Carolyn Dinshaw describes “the standard medieval analysis of the allegorical text: it contains truth veiled by obscurity.” She continues:

Augustine, Lactantius, Isidore of Seville, Vincent of Beauvais, Petrarch, Dante, Boccaccio use this figure of the veil to describe passages in both biblical and secular literature … the spiritually healthy reader will discover the truth under the veil of fiction, under the covering of poetical words. As Boccaccio argues, fiction pleases even the unlearned by its surface blandishments, and it exercises the minds of the learned in the discovery of its beautiful, hidden truth.Footnote 12

As Dinshaw indicates, the text or truth in these cases is figured as a veiled woman. Allegorical interpretation is “undressing the text – unveiling the truth, revealing a body figuratively represented as female.”Footnote 13 This gendered understanding of allegorical method entails “the concomitant representation of various literary acts – reading, translating, glossing, creating a literary tradition – as masculine acts performed on [a] feminine body.”Footnote 14

In Seeing through the Veil: Optical Theory and Medieval Allegory, Suzanne Conklin Akbari compares etymology and allegory in such a way that deepens our understanding of allegory’s relationship to veiling. She writes that whereas etymology “reveals truth by revealing the origin of a word, implicitly, of the thing it represents, allegory reveals truth by clothing an otherwise inexpressible meaning in words whose literal sense is at odds with the figurative sense.”Footnote 15 Akbari elaborates:

Allegory is closing, wrapping or clothing in a veil. Allegorical interpretation or allegoresis, on the other hand, is very similar to etymology, for both are interpretive endeavors dedicated to unveiling truth … Both the writer who performs allegoresis on a classical text and the reader who interprets an allegorical fiction extract the kernel of the truth from the husk, removing the veil or integumentum that conceals the meaning.Footnote 16

We can find this understanding of allegory expressed in John Bunyan’s 1678 Christian allegory (and widely popular English novel), Pilgrim’s Progress. The hero of the book, Christian, concludes Part I with these words: “Put by the Curtains, look within my Vail/Turn up my Metaphors and do not fail:/There, if thou seekest them, such things to find/As will be helpful to an Honest mind.”Footnote 17 The “Honest mind” of the Christian pilgrim will be rewarded for its diligent work of allegorical interpretation envisioned here as the drawing back of curtains and parting of a veil.

Allegorical reading is thus gendered work: the unveiler is male, the unveiled female. A hierarchized, sexualized shadow is cast over allegoresis. Daisy Delogu, in her work on allegory in late medieval French literature, argues that gender is a “useful lens through which to examine the practice of allegory.”Footnote 18 She writes:

The very processes of allegorical writing and reading are imagined by their practitioners in gendered terms … Allegorical reading in the Middle Ages was a generative process, one in which the (male) exegete drew forth meaning from God’s fecund allegorical texts – Scripture and the world. The allegorical text was often said to be veiled, like a chaste or modest woman, and it was the object of the (again male) reader to strip allegory of its covering, to lay bare and possess allegory’s hidden meaning.Footnote 19

The gendering of the text and the sexualization of the acts of reading and interpreting not only have roots in ancient and medieval thinking, they also inform allegorical projects in the Renaissance, Enlightenment, and modernity more generally, as suggested by Barrias’s popular statue, Nature Unveiling Herself before Science, with which this chapter began.Footnote 20 Barrias’s statue provokes some of the initial philosophical questions of this book, but another context drives some of the questions that I pursue in regard to gender, virtue, and freedom. It is to this political context that I now turn.

The Politics of Veiling

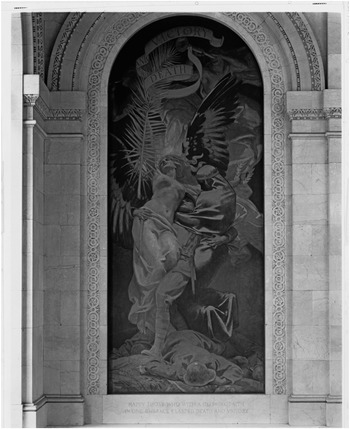

In 1922, John Singer Sargent was commissioned to paint two murals that would adorn the landing in the central staircase of Widener Memorial Library at Harvard University. The murals were commissioned to commemorate members of Harvard’s community who had died in World War I. One of the murals, Death and Victory, depicts a dying soldier as he carries two figures, Death and Victory, on a mythic battlefield (Fig. I.2). Victory and Death are figured as women – the woman on the left a winged, white woman, golden locks flowing, holding a palm and a laurel wreath, gazing upward to the heavens. Victory’s silk covering has dropped to her waist, revealing her naked torso.Footnote 21 Death, on the right, is characterized by a large black mantle that covers her entire body, face and feet included. Victory is light, unveiled, and she lifts the soldier upward to glory; Death is wrapped in black and weighs the soldier down while strangling his neck. The images of Victory and Death attest to Sargent’s participation not only in a long artistic tradition of using women to personify abstract concepts, but also in a more contemporary movement to use figures of goddesses and female personifications to promote governmental, military, and commercial projects. Such figures are especially present in war propaganda.Footnote 22

Fig. I.2 John Singer Sargent, Death and Victory, Harvard Portrait Collection, anonymous gift to Harvard University, photo © President and Fellows of Harvard College.

I am interested, however, in an international twenty-first century viewing community of the Sargent murals, one that includes students, workers, librarians, scholars, and teachers, an increasing number of whom cover their heads for religious, social, or political purposes. Sargent’s association of the unveiled woman, Victory, with whiteness and life and the association of the covered woman with blackness and death strikes a particularly insidious note for those concerned with the imbrication of sexism, anti-black racism, and anti-Muslim hate here over a century after the dedication of the murals.Footnote 23

An examination of early Muslim head-covering practices lies just beyond the scope of this book, but the myriad discourses and debates on Muslim women’s “veiling” form the political context in which I write. In the lead-up to the US war in Afghanistan, the “liberation” of Afghan women was used as a justification of American foreign and military policy in the Middle East. For many Westerners, the image of a liberated Afghan woman was an unveiled Afghan woman. Veiling, according to this way of thinking, signaled women’s oppression, religious dogmatism, and cultural “backwardness”; the success of the US mission in Afghanistan would be measured, in part, by the unveiling of its women. In 2004, in the midst of the so-called affaire du foulard, French legislators forbade the wearing of the headscarf and other “ostentatious” signs of religious affiliation in public schools. As Jennifer Heath writes in the introduction to the 2008 edited volume The Veil: Women Writers on Its History, Lore, and Politics: “Veiling has become globally polarizing, a locus for the struggle between Islam and the West and between contemporary and traditional interpretations of Islam.”Footnote 24 It is worth recalling, as Heath does, that the history of women’s veiling predates the rise of Islam. Veiling practices were commonplace, though not universally so, in the ancient Mediterranean and Western Asia, and these practices continued in Greek, Roman, Christian, and Jewish communities. Moreover, women from Canada to Argentina, Morocco to Indonesia, India to Norway – not all of them Muslim, not all of them religious – veil their heads in the present day. Veiling is irreducible to a single meaning, religious affiliation, time period, location, idea of freedom, or experience of gendered oppression.

In Sex and Secularism, Joan Wallach Scott writes that the “twenty-first-century discourse of secularism rests on an opposition between the West and Islam articulated in terms of a contrast between uncovered and covered women’s bodies. Uncovered women are presumed free to follow their desire, whereas covered women are not.”Footnote 25 She elaborates on secularism’s bifurcation of women into uncovered/free and covered/unfree, writing:

The popular Western representation of Muslim women portrays them as sexually repressed while their secular Western counterparts are sexually liberated (“they” are trapped in a past from which “we” have escaped; “they” lack access to the truth that “we” know how to discover). The focus is on women … as the embodiment of Western liberation on the one side, and as victims of Islamic oppression on the other. Women, once “the sex” and excluded from citizenship on those grounds, now – still as “the sex” – provide the criteria for inclusion, the measure of liberated sexuality, and, ironically, for gender equality.Footnote 26

As Scott demonstrates, one of the primary ways that we measure liberty in the twenty-first century West is by sexual emancipation. According to this line of thinking, the subject of freedom is a subject of a liberated sexual desire. For many so-called secular societies, the image of the covered Muslim woman showcases the opposite of this sexual liberation. In other words, the image of the veiled woman now stands in as a (or the) marker of the opposite of freedom, the one to whom liberation must be brought. This seems to be an important and evolving addition to Sargent’s linkages of a fully veiled woman with death, error, and darkness, on the one hand, and of an unveiled, partially clad white woman with life, victory, truth, and enlightenment, on the other. In the early twenty-first century, an association of unveiling with freedom and gender equality – and veiling with oppression and women’s subjection – provides another politicized nuance to long-standing notions of veils as signifiers of ignorance, error, surface meaning, and death.

In the Politics of Piety: The Islamic Revival and the Feminist Subject, an ethnographic study of the women’s piety movement in the mosques of Cairo in the 1990s, Saba Mahmood notes that “the veil, more than any other Islamic practice, has become the symbol and evidence of the violence Islam has inflicted upon women.” When she presented her research on head covering as an agentive practice of piety to audiences in the United States and Western Europe, Mahmood was “struck by [their] lack of curiosity about what else the veil might perform in the world beyond its violation of women.”Footnote 27 Mahmood’s question – What else might the veil perform in the world? – became a guide for me as I explored texts and images of veiling in late antiquity. It is, in other words, a guiding question for this book.

As I argue in the following chapters, the veil is and has been a complex, overdetermined symbol characterized by “excesses of meaning,” “confusion of boundaries,” slipperiness, and contradiction.Footnote 28 It has signified death, terror, and violence, and it has connoted life, femininity, marriage, and fertility. Veils simultaneously hide and reveal beauty. They signal modesty and erotic allure. As Eve Kosofsky Sedgwick has commented:

The veil itself … is also suffused with sexuality. This is true partly because of the other, apparently opposite set of meanings it hides: the veil that conceals and inhibits sexuality comes by the same gesture to represent it, both as a metonym of the thing covered and as a metaphor for the system of prohibitions by which sexual desire is enhanced and specified.Footnote 29

The veil has, at different times in history, played a part in the hiding or display of strong emotions, including sadness and shame; shifts in status, as in the lifting of the veil in a marriage ceremony; the performance of piety; the justification of war, as in the calls to unveil (and thereby liberate) Afghan women after 9/11; and resistance to and defiance of colonization and anti-Muslim hate and policy.Footnote 30 For some, the veil is a part of their practice of freedom, and for some it is decidedly not.

The primary focus of this book is the multiple functions and meanings of veiling in the late ancient Mediterranean (roughly, the third century to seventh century CE). These centuries witnessed multiple political realignments, technological developments, and cultural shifts – including the emergence of Christianity as the religion of the Roman Empire; the growth and development of rabbinic Judaism in Roman Palestine and Sasanian Mesopotamia; the continued sway of traditional Greek, Roman, Syrian, and Egyptian practices and pantheons, among others; and the persistent pull of intellectual traditions from Platonism to Stoicism. Amidst these large-scale transformations, I am curious about the meanings – large and small – of a particular material object: one comprised of cloth of linen, wool, or silk thrown about the shoulders, draped over the head, hung from a doorway, or arranged over an altar. As mentioned above, women’s veiling practices were an important feature of ancient life in the Mediterranean world and thus predate women’s versatile veiling practices in Islamic cultures of the early Middle Ages.

I argue that in late antiquity veils hid and revealed, marked boundaries between spaces, and signaled the virtue and piety of their wearers and the mystery and sacrality of that which they covered. They thus played a role in the construction of what we would now term “the religious.” In the hands of late ancient allegorists, veils proved particularly useful to describe how the surface meaning of words concealed (and yet revealed) hidden depths of meaning. The allegorical projects of Christian biblical interpreters are thus caught up in – and mutually informed by – the materiality of the daily and ritual lives of the late ancients. It is this nexus of allegorical reading practices, biblical images, men’s and women’s veiling practices, and veils as material objects that this book explores. In sum, I argue that the textual and visual evidence of veiling summons up the world of late antiquity – the splendid array of practices of piety, the various choreographies of rank and respect, the weight given to boundary making and crossing, and the “blossoming scriptural imagination” of late ancient Jews and Christians.Footnote 31

Plan of the Book

The book’s first chapter, “Veiling in the Ancient Mediterranean,” familiarizes readers with the diverse veiling practices, terms, instructions, and images of the ancient Mediterranean. I situate ancient Greek, Roman, and Israelite practices of veiling within cultural conceptions of gender, social status, the body, sexuality, marriage, fashion and aesthetics, and practices of piety. I argue that the Greek concept of aidōs – often translated as “shame” or “modesty” – and its Latin cognate, pudicitia, are helpful guides as we think through the manifold meanings of ancient veiling. Aidōs signals one’s sensitivity to and knowledge of social rules and status differentials. By displaying aidōs in the action of covering the head, an ancient woman could signal her virtue and excellence, her bodily self-control and chastity, and her beauty, poise, discretion, and piety. An ancient man could signal his piety, leadership, and power and his proper deference to the gods, or he could cover up an intense emotion (such as grief or anger) that made social interaction momentarily problematic.

In Chapter 1, vase paintings, portrait statues, and grave steles are put in conversation with literary examples from Homeric epic, myth, Socratic dialogues, histories, the Tanakh (Hebrew Bible), and moral advice. The Tanakh contains no law directing women to veil and no evidence that veiling was or was not a frequent or traditional practice for men or women in ancient Israel. Yet veils appear in the Hebrew biblical texts, and they are most often mentioned in relation to women. Considering the variety of sources from the ancient Mediterranean, I assert that veiling practices were ordinary (part of daily life) and extraordinary (part of special ritual occasions). Veils were versatile objects that were used in a variety of everyday and ritual settings, and performances of veiling must be considered in relation to these complex social contexts.

The second chapter, “Veils in Corinth: Paul’s First Letter to the Corinthians,” examines an influential and far-reaching passage on women’s veiling from the New Testament. In 1 Cor 11:2–16, Paul crafts a complex argument to instruct women in the ekklēsia of Corinth to put a head-covering over their heads when they pray or prophesy in church. He instructs men to have their heads uncovered during these rituals. Along with considering Paul’s instruction in its social and historical contexts, I examine the history of twentieth- and twenty-first century feminist interpretations of this passage, with a particular emphasis on historical reconstructions of the un/veiling women’s position in the ancient Corinthian ekklēsia. I show how many twentieth- and twenty-first century scholars represent the unveiling Corinthian women (to whom they believe Paul aims his instruction) as resisting male ideologies that insist on women’s subordination to men. I then compare these historical reconstructions with late twentieth-century US representations of the unveiling of Muslim women, in which unveiling functioned as a paradigmatic sign of women’s freedom from gendered and religious oppression. This chapter in particular explores how current debates about women, religion, secularism, and freedom shape the understanding and representation of women’s practices of veiling, both then and now. My argument in this chapter is largely cautionary: I advise that we must be wary of imposing a framework in which veiling signals subjugation and unveiling signals liberation on the first-century Corinthian community. Not only does such a framework limit the prolific multivalence of women’s covering practices in antiquity, but it also participates in and perpetuates (inadvertently or not) Orientalist narratives that denigrate Muslim women in particular. I conclude Chapter 2 by arguing that the Corinthian women’s veiling and unveiling practices remain largely opaque to modern readers; like other women in the first-century Mediterranean world, these women most likely veiled and unveiled for a variety of reasons having to do with fashion and beauty, comfort, status differentials, and performances of virtue, piety, and deference. We must refuse Paul’s logic that seeks to fix the meaning of women’s veiling as symbolic of a gendered hierarchy in which men function as the authority, or head, of women.

The third chapter, “Women’s Veiling Practices in Late Antiquity,” focuses on the extant textual and material evidence for veiling among the late ancients, with special attention paid to the writings of early Christian leaders and rabbis. Several studies in late ancient history, including those by Kate Wilkinson, Kristi Upson-Saia, Carly Daniel-Hughes, Alicia Batten, and Kelly Olson have explored late ancient Christian writers’ and rabbis’ advice to women on dress, veiling, and modesty.Footnote 32 This chapter builds on these previous studies to collect Greek and Latin textual evidence on women’s veiling practices in the second through fifth centuries CE, and examine it in light of material artifacts and ritual practices. Late ancient Christianity developed in dynamic relation to Judaism and the burgeoning rabbinic movement, and I consider rabbinic recommendations for women’s head-covering practices alongside the instructions for veiling authored by male Christian writers. I argue that late ancient Christian and Jewish male writers largely agreed with Roman and Greek moralists that head covering was a way for women to signify modesty, chastity, piety, discretion, and virtues of self-control (aidōs, pudicitia, sōphrosynē, and enkrateia). These virtues continued to be prized by the late ancients, and as many early Christian writers increasingly emphasized the holiness of the virginal state, they put their own stamp on these virtues as they related to women virgins in particular. Moreover, as we move into the fourth and fifth centuries, we will see that Christian writers increasingly drew upon the language of Paul in 1 Cor 11:2–16. In their exhortations for women’s veiling, many of these writers built on Paul’s language to insist on veiling as a way that women could signal their submission to men – their “proper” place in gendered hierarchy. This chapter traces, in part, the entrenchment of gendered hierarchies of power in late ancient discourses of veiling and the development of un/veiling rituals among late ancient Jews and Christians.

Chapter 3 is bookended by an examination of visual evidence for women’s veiling in the late ancient Mediterranean. Some art historical studies have explored the role of women’s veiling, in ancient Greek art in particular, but to date there is no comprehensive study of the visual evidence for early Christian veiling.Footnote 33 Building on the work of scholars who examine images of women in early Christian funerary art (Nicola Denzey Lewis, The Bone Gatherers, and Christine Schenk, Crispina and Her Sisters),Footnote 34 I analyze the representation of women’s head-covering practices in late ancient material culture: the paintings in the Christian baptistery and synagogue of Dura Europos, the Roman and Neapolitan catacombs, mosaics of late Roman Christian buildings, and depictions of women on sarcophagi and late ancient textiles. I argue that, taken together, the visual and textual evidence indicates the continued significance, complexity, opacity, beauty, and versatility of veiling practices among the late ancients. Moreover, I show that, insofar as veiling was entwined with performances of social status, honor, shame, scrupulousness, deference, and obligations to others and the gods, it was part and parcel of the formation of religious and liturgical subjects in the late ancient imaginary.

In the fourth chapter, “Draping the Sacred: Veils in Late Ancient Ritual, Art, and Architecture,” I cast a wider net to consider the diverse roles of veiling and unveiling in late antiquity in general and early Christian practice in particular. I explore liturgical uses of veils to cover holy objects or aid in the performance of ritual, as architectural features within churches and homes, as ritual objects to drape over head and hands, and as signifiers of the separation of the earthly from the divine realm. The textual evidence in this chapter ranges from early manuals of church order to the vitae of holy women and the writings of Christian leaders of the third, fourth, and early fifth centuries. Visual evidence is also central to the argument of this chapter; I trace the representation of curtains, drapery, and other architectural veils in early Christian art from the earliest Christian frescoes to the catacombs and sarcophagi of the fourth and fifth centuries, to the mosaic programs of sixth-century Ravenna and Rome. With this range of materials, I examine the multiple uses and weighted meanings of textiles and coverings in early Christian practice, and I introduce the performative aspects and theological uses of veiling and unveiling. I argue that one of the ways that veiling increasingly signified in this period was to intimate mystery, sacrality, and hiddenness while hinting at the promise of revelation and discovery.

The fifth chapter, “Origen’s Veils: The Askēsis of Interpretation,” examines metaphors of veiling and unveiling in allegorical interpretations of the Bible in the work of a prominent third-century theologian, Origen of Alexandria. I explore biblical allegory more generally and trace the beginnings of the imagery of the “unveiling” of spiritual truth in early Jewish and Christian texts, including the letters of Paul. Turning to Origen, I show how he used the image of the veil to describe the relation between the “letter” of the text and its hidden, spiritual meaning. Origen constructed a theory of biblical interpretation that relied on the imagery of the veil and the hiddenness of the truth of scripture; his biblical interpretations consistently privileged the Christian “spirit” of the text over what he calls the Jewish “letter,” or “flesh,” of the text. The jointly authored book Veils, by Hélène Cixous and Jacques Derrida, serves as a touchpoint throughout this chapter for interrogating the role of the visual, the textural, the covered, and the performative theatricality of uncovering in Origen’s writing and allegorical theory.

The sixth chapter, “Gregory’s Veils: Gregory of Nyssa’s Homilies on the Song of Songs,” examines the role of veil imagery in a set of homilies by Gregory of Nyssa, a fourth-century Christian intellectual from an illustrious Cappadocian family who was shaped by Origen’s allegorical writings. As an inheritor of Origen’s thought, Gregory produced some of the foundational works of Christian mysticism, drawing on allegorical theories that privileged metaphors of sight and touch and conceived of the soul’s desire for God as an infinite, enrapturing unveiling. For Gregory, veils and revelations become part of the way to illustrate the soul’s pursuit of divine love and union. I argue that the numerous veils of the biblical book the Song of Songs become the threads with which Gregory weaves not only his mystical reflections on the soul’s unrelenting desire for God but also his description of the allegorist’s pursuit. In this way, I strive to follow the bright collision points of the intellectual worlds of allegory and biblical hermeneutics (represented here by Origen and Gregory) with the material worlds of sumptuous veils.

Whereas the first part of the book (Chapters 1–4) situates the veil in its ancient Mediterranean context, including the rich visual cultures of Greeks, Romans, and late ancient Jews and Christians, the second part (Chapters 5 and 6) explores the ramifications of theological associations of veils with the “letter,” the feminine, Judaism, eroticism, and the flesh, on the one hand, and unveiling with the construction of the sacred and the pursuit of truth and divinity, on the other. The veil, I argue, is a pivotal image in diverse early Christian understandings of gender, orthodox identity, Jewish–Christian difference, biblical interpretation, and ritual performance. The veiling and unveiling of truth (and the idea of truth-as-woman) has informed much of Western philosophy and theology over a long span of centuries – a beguiling subject that is beyond the scope of this book but which nevertheless makes brief appearances in the final chapters and the epilogue, “Derrida’s Tallit.”