Statement of Research Significance

Research Question(s) or Topic(s): Given previous studies on the adverse effect of chronic stress on cognition, we explored the potential effects of childhood war exposure on late-life cognition and the development of mild cognitive impairment and/or dementia. Our cohort was born before or during World War II (1940–1944) or the subsequent Greek Civil War (1946–1949) and, at the time of their assessment, were over 64 years of age. Main Findings: We found better late-life cognition and lower risk for developing mild cognitive impairment and dementia among those who were in middle childhood or adolescence, relative to those who were in early childhood during a war. Study Contributions: Our findings show that early childhood war exposure is linked to weaker resilience and poorer late-life cognitive outcomes relative to exposure in middle childhood or adolescence, suggesting the importance of resilience-building interventions as a means of prevention for those at high risk.

Introduction

War experiences can, undoubtedly, rank among the most traumatic events for individuals, particularly when exposed during early-life stages (El-Khodary & Samara, Reference El-Khodary and Samara2020). While previous research has indicated that trauma in early childhood can have detrimental effects on cognitive function later in late life (Nilaweera et al., Reference Nilaweera, Freak-Poli, Gurvich, Ritchie, Chaudieu, Ancelin and Ryan2022), there is a gap in our understanding of the specific effects of exposure to war. Moreover, the few available studies on the subject have yielded conflicting results, with at least one, paradoxically, indicating cognitive advantages among people exposed to such events (Tom et al., Reference Tom, Phadke, Hubbard, Crane, Stern and Larson2020).

Numerous studies have established that early-life stressful experiences can have adverse effects on the developing brain (Herzberg & Gunnar, Reference Herzberg and Gunnar2020; Tian et al., Reference Tian, Li, Zhang, Wang, Liu, Wan, Fang, Wu, Zhou and Zhu2021). Some studies have suggested that these effects may extend to late stages of life. For instance, recent research revealed that individuals who experienced abuse or financial difficulties during childhood demonstrated slowed psychomotor speed and poor verbal fluency in old age (Nilaweera et al., Reference Nilaweera, Freak-Poli, Gurvich, Ritchie, Chaudieu, Ancelin and Ryan2022), but no associations with dementia prevalence. In contrast, other studies have shown that stress in childhood was associated with an increased risk of dementia in old age after controlling for confounding variables (Donley et al., Reference Donley, Lönnroos, Tuomainen and Kauhanen2018; Tani et al., Reference Tani, Fujiwara and Kondo2020).

War, marked by a series of adverse experiences (e.g., loss of loved ones, abuse, threat to life, displacement, and malnutrition) which, individually, have been previously linked to cognitive impairment (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Xu, Li, Cao, Tan, Yu and Zhu2019), has been a focal point in this research domain. Challenges in data collection, however, have contributed to a scarcity of studies examining the associations between exposure to war during childhood and late-life cognition. Hence, the limited number of studies exploring this topic.

Interestingly, research on adult war survivors has indicated a connection between war trauma and cognitive impairments. For instance, one study demonstrated an elevated risk of dementia among individuals who had been prisoners of war. The risk was even more pronounced among people who were also experiencing Post-Traumatic Stress Disorder (PTSD) (Meziab et al., Reference Meziab, Kirby, Williams, Yaffe, Byers and Barnes2014). Consistent findings were demonstrated in other studies, showing an increased occurrence of dementia among war veterans, influenced by factors such as depression and other mental disorders (Iacono et al., Reference Iacono, Lee, Edlow, Gray, Fischl, Kenney, Lew, Lozanoff, Liacouras, Lichtenberger, Dams-O’Connor, Cifu, Hinds and Perl2020; Rafferty et al., Reference Rafferty, Cawkill, Stevelink, Greenberg and Greenberg2018; Veitch et al., Reference Veitch, Friedl and Weiner2013).

While research on young populations is very limited, an examination of male Holocaust and Nazi concentration camp survivors exposed to war events during late adolescence and adulthood revealed no association between such exposure and the development of dementia in old age (Ravona-Springer et al., Reference Ravona-Springer, Beeri and Goldbourt2011). Conversely, a different study showed that older men who had experienced the Holocaust during adolescence and also had a history of coronary heart disease exhibited poorer cognitive performance in old age than their peers (Weinstein et al., Reference Weinstein, Lutski, Keinan-Boker, Goldbourt and Tanne2021). Finally, in line with the Meziab and colleagues (2014) investigation in adults, a study conducted on former Swiss child laborers revealed an association between PTSD symptoms and impaired cognitive function in old age (Burri et al., Reference Burri, Maercker, Krammer, Simmen-Janevska and Schmidt2013).

The time period around World War II (WWII) has also been investigated in this research domain. A longitudinal study involving over 4000 individuals in Seattle found that those born between 1929 and 1949, including the Great Depression era, WWII, and the postwar period in the US exhibited a lower incidence of dementia compared to individuals born between 1921 and 1928, suggesting that childhood and adolescent experiences may have played a more determinative role with respect to late-life cognition than factors during childhood (Tom et al., Reference Tom, Phadke, Hubbard, Crane, Stern and Larson2020). Given what is known currently regarding the negative impact of early life adversity on brain development (for a review, see National Scientific Council on the Developing Child, 2008), this seemingly contradictory discovery was characterized as an enigma by Knopman (Reference Knopman2020), who ascribed it to a selection bias (survivors having higher cognitive reserve than non-survivors), adaptation leading to the development of crucial for survival cognitive skills, as well as improvements in medical care, reductions in multimorbidity, and enhanced socioeconomic status and educational opportunities within the 1929–1949 cohort compared to the pre-Great Depression cohort. Of course, the later cohort may have benefited from the boost to the US economy provided because of WWII, as well as increased educational opportunities and medical advances relative to the earlier cohort. Thus, these studies would appear to suggest that later childhood experiences may have played an enhancing role with respect to late-life cognition, rather than the possibility that early-life stressors adversely affected it.

Another factor that may account for the differential findings regarding childhood war cohorts may relate to education. To the extent that education sets the foundation for the strengthening of cognitive reserve (Seyedsalehi et al., Reference Seyedsalehi, Warrier, Bethlehem, Perry, Burgess and Murray2023), one might expect positive effects of systematic elementary education relative to inconsistent and/or delayed formal education. While most research regarding the effect of education on cognitive reserve focuses on the amount attained (i.e., number of years or level of education), here we refer to the functional and structural effects of education on the brain (Castro-Caldas et al., Reference Castro-Caldas, Petersson, Reis, Stone-Elander and Ingvar1998; Petersson et al., Reference Petersson, Reis and Ingvar2001). These effects may enhance overall cognition through creating a foundation on which to continue to build over the course of one’s life, education, and other experiences.

The number of studies in this field is limited, preventing a comprehensive understanding of the reasons behind the observed discrepancies in outcomes among individuals exposed to the stress of war in early life. In the present study, we addressed this gap by examining the associations between war exposure in childhood and cognitive function and the prevalence of dementia in old age. Additionally, we explored the influence of socioeconomic status, education, multimorbidity, and other potentially confounding factors. Our exploratory study focused on older adults who experienced either or both WWII (1940–1944) and the subsequent Civil war (1946–1949) in Greece during their childhood. These periods were characterized by chronically stressful conditions including famine, threat to life and bodily integrity, and multiple losses, as well as particular stressful events such as illnesses and atrocities, such as mass retaliatory executions (during WWII) and the forced expatriation of children for political reasons (during the Civil war). The cumulative effect of these events resulted in a humanitarian crisis with profound consequences for the well-being of children.

Methods

Data for the study were collected as part of the large-scale epidemiological study (Hellenic Longitudinal Investigation of Aging and Diet (HELIAD) conducted in the prefecture of Larissa and in Maroussi, a suburb of Athens, Greece (for a description, see Dardiotis et al., Reference Dardiotis, Kosmidis, Yannakoulia, Hadjigeorgiou and Scarmeas2014). The objective in undertaking the HELIAD study was to explore the occurrence and relationship between subjective cognitive decline, Mild Cognitive Impairment (MCI), Alzheimer’s Disease (AD), and other forms of dementia in the older population residing in Greece on the one hand, and factors such as demographic characteristics, dietary habits, genetics, medical history, and lifestyle on the other.

Participants were randomly selected from the population through municipal rolls and invited to take part in the study. All participants provided written informed consent, and no financial incentives were provided. The research procedures adhered to the principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki for the protection of human research participants and were approved by the institutional ethics review boards of the University of Thessaly and the National and Kapodistrian University of Athens.

Participants provided details regarding their demographic characteristics (date and place of birth, sex, and educational attainment in terms of number of years of school completed), lifestyle (including current or past smoking habits and duration of smoking), historical and current sociodemographic features (pre-retirement occupation and the occupational history of their parents), a comprehensive medical history (covering existing health conditions, medications, and comorbidities and including blood work), as well as indications of a family history of dementia.

Certified neurologists and trained neuropsychologists examined each participant and administered a full neurological exam and a comprehensive neuropsychological assessment during face-to-face meetings. The presence and stage severity of dementia symptoms were assessed with the Clinical Dementia Rating (CDR) Scale (Morris, Reference Morris1993). The scale assesses five domains of cognitive and functional performance on a five-point scale; CDR = 0 denotes no cognitive impairment, and CDR = 4 denotes severe cognitive impairment. It also provides a global rating score. Neuropsychological assessment included the Mini-Mental State Examination (MMSE) (Folstein et al., Reference Folstein, Folstein and McHugh1975) as a gold-standard measure to determine overall cognitive functioning, but also a series of tests examining several cognitive domains. Specifically, the Medical College of Georgia Complex Figure Test (MCG) – immediate and delayed recall and recognition (Kosmidis et al., Reference Kosmidis, Vlahou, Panagiotaki and Kiosseoglou2004) – and the Greek Verbal Learning Test (GVLT) (Vlahou et al., Reference Vlahou, Kosmidis, Dardagani, Tsotsi, Giannakou, Giazkoulidou, Zervoudakis and Pontikakis2013) were used to assess visuospatial and verbal memory. A shortened version of the Judgment of Line Orientation test (JLO) (Benton et al., Reference Benton, Sivan, Hamsher de, Varney and Spreen1994), the Clock Drawing Test (Bozikas et al., Reference Bozikas, Giazkoulidou, Hatzigeorgiadou, Karavatos and Kosmidis2008), and the MCG copy condition (Lezak et al., Reference Lezak, Howieson, Loring and Fischer2004) were administered to assess visuospatial perception. Semantic and phonological verbal fluency (Kosmidis et al., Reference Kosmidis, Vlahou, Panagiotaki and Kiosseoglou2004), subtests of the Greek version of the Boston Diagnostic Aphasia Examination-short form (Borod et al., Reference Borod, Goodglass and Kaplan1980; Tsapkini et al., Reference Tsapkini, Vlahou and Potagas2009), namely, the Boston Naming Test-short form, and selected items from the Complex Ideational Material Subtest were used to assess language ability. Attention and information processing speed were evaluated with the Trail Making Test (TMT) Part A (Armitage, Reference Armitage1946; Vlahou & Kosmidis, Reference Vlahou and Kosmidis2002). Finally, executive functioning was evaluated with the TMT-Part B, verbal fluency, anomalous sentence repetition, a graphical sequence test, and the ratio of speedy recitation of months backwards over forwards (Lezak et al., Reference Lezak, Howieson, Loring and Fischer2004). Diagnostic classification of participants with MCI or dementia was determined at diagnostic consensus meetings of the research group based on the Diagnostic and Statistical Manual of Mental Disorders, 4th edition, Text Revision (DSM IV-TR) (American Psychiatric Association, 2000). MCI diagnosis was based on the Petersen criteria (Petersen, Reference Petersen2004).

To assess participants’ symptoms of anxiety and depression, we employed both the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) (Zigmond & Snaith, Reference Zigmond and Snaith1983) and the Geriatric Depression Scale Short Form, consisting of 15 items (GDS-15) (Yesavage et al., Reference Yesavage, Brink, Rose, Lum, Huang, Adey and Leirer1982; Yesavage, Reference Yesavage1988).

Finally, blood tests provided information regarding participants’ current health status; the only blood parameter relevant to the present study, however, was the identification of one or two ε4 alleles of the apolipoprotein E (Apo-E) in the participants’ genotype.

We selected covariates based on their well-established relevance to cognitive outcomes in aging and dementia research. Anxiety and depression symptoms were measured using the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale and the Geriatric Depression Scale because mood disorders have been shown to influence cognitive performance and increase dementia risk (Santabarbara et al., Reference Santabarbara, Lipnicki, Villagrasa, Lobo and Lopez-Anton2019). Genetic risk was captured by assessing ApoE ε4 allele status, given its strong and consistent association with Alzheimer’s disease and cognitive decline (van der Lee et al., Reference van der Lee, Wolters, Ikram, Hofman, Ikram, Amin and van Duijn2018). The Multicomorbidity Index was created to reflect the burden of multiple coexisting health conditions, which are known to affect cognitive function (Calvin et al., Reference Calvin, Conroy, Moore, Kuźma and Littlejohns2022). To improve model specificity, a genetic predisposition to dementia variable was included, integrating both ApoE ε4 status and family history of dementia. Finally, occupational categories of participants and their parents served as proxies for socioeconomic status and cognitive reserve, factors influential in late-life cognition (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Hu, Wang, Ma, Dong, Tan, Yu and Zhu2020). These covariates allowed us to control for key biological, psychological, and social confounders in examining the association between early-life war exposure and late-life cognitive outcomes.

War exposure was determined based on the individual’s date of birth. Considering the widespread impact of both WWII and the subsequent Civil war across all Greek regions, we hypothesized that individuals born within the timeframes of these conflicts would have experienced the effects of war events. WWII lasted from October, 1940, to October, 1944, and the Civil war from March, 1946, to October, 1949. To calculate individuals’ age during one or both wars and duration of exposure, we subtracted the person’s date of birth from each war’s end date. Age was then categorized into two ranges: a) > 0 months to 60 months of age by the end of the war, representing exposure in early childhood, b) 61 months to 120 months of age by the end of the war, signifying exposure in middle childhood, and c) 121 months to 216 months of age by the end of the war, defined as exposure during adolescence.

Standardized scores were calculated for all individual psychometric test scores and grouped into five main cognitive composite scores. The composite scores included memory, attention/processing speed, language, executive functioning, and visuospatial perception composite scores, and all were combined under a total cognitive composite score. Also, the MMSE total score, CDR total score, and the researchers’ diagnostic consensus regarding meeting the diagnostic criteria for MCI or dementia, as well as its subtype, were used as variables to examine the link between war exposure on the one hand and cognitive functioning and clinical status on the other.

We computed the cumulative scores for both the HADS and GDS scales. Subsequently, through collaborative decision-making among clinicians, a consensus was reached to determine whether the severity of existing depression and anxiety symptoms had the potential to impact cognition. Two variables were then generated: severe anxiety (potentially affecting cognition) and severe depression (potentially affecting cognition), each with binary values (0 for no and 1 for yes). The two variables will henceforth be referred to as Anxiety and Depression, respectively.

In addition, participants’ self-reported comorbidities were consolidated into a single variable representing the total number of comorbidities, referred to as the Multicomorbidity Index. Lastly, a variable called Genetic Predisposition to Dementia was calculated, taking on values of 0 (no) or 1 (yes). This variable indicated the presence of either one or two ApoE ε4 alleles and/or a family history of dementia.

Finally, participants’ reported occupations, encompassing both their own and their parents’ professions, were categorized into 13 main groups. These categories include homemaker, farmer, herder, worker (in factory, production, etc.), craftsperson (e.g., blacksmith, seamstress), self-employed (trade, salesperson), civil servant in office (e.g., white-collar employees, such as bank clerks, telecommunication companies), civil servant manual laborer (e.g., roadworks), work in a private office (e.g., lawyer), teacher, manager, unemployed, or other (e.g., flight attendant).

The characteristics of the samples can be found in Table 1.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the age groups in WWII and civil war samples

Statistical analyses were carried out using the Statistical Package for Social Sciences (SPSS-Version 25.0). To examine whether cognitive performance predicted the likelihood of exposure to WWII during early and middle childhood and adolescence, we conducted binary logistic regression analyses. Specifically, each of the three exposure periods (early childhood, middle childhood, and adolescence) was treated as a dichotomous dependent variable within dyads (i.e., early vs. middle childhood and middle childhood vs. adolescence). The predictors included both categorical and continuous variables such as the MMSE total score, clinical diagnosis of dementia, CDR total score, and cognitive domain composite scores. Covariates considered in all analyses were current age, sex, and years of education.

In adjusted models, additional control was implemented for current smoking, total years of smoking, Multicomorbidity Index, anxiety and depression potentially affecting cognition, and parents’ occupation – a proxy for childhood socioeconomic status. Chi-squared tests were also conducted to examine associations between war exposure age groups and participants’ occupation pre-retirement as an index of adulthood achievement, as well as their genetic predisposition to dementia, the prevalent subtype of dementia, and percentage of illiterate individuals.

Separate logistic regression analyses were performed for each war (WWII and the Civil war) across the three childhood age ranges, analyzed in dyads (i.e., early vs. middle childhood and middle childhood vs. adolescence). Furthermore, the dataset was also stratified by sex to discern any variations in the impact of war exposure on cognitive outcomes between men and women.

Results

WWII

When comparing individuals exposed to WWII in early versus middle childhood, none of the cognitive measures significantly predicted exposure group (Memory: B = .144 (S.E. = .131), p > .05, OR:1.155, 95%CI:.893–1.493, Executive functioning: B = .073 (S.E. = .149), p > .05, OR:1.076, 95%CI:.804–1.440, and visuospatial perception: B = .010 (S.E. = .130), p > .05, OR:1.011, 95%CI:.783–1.304). Higher Language composite scores, however, were associated with increased odds of belonging to the middle-childhood exposure group relative to the early-childhood group (B = .316 (S.E. = .152), p = .038, OR:1.372, 95%CI:1.018–1.849). When analyzed separately by sex, better language performance significantly predicted membership in the middle-childhood exposure group for men but not for women. Specifically, for men, higher language scores were associated with increased odds of belonging to the middle-childhood group (B = .680 (S.E. = .235), p = .004, OR:1.974, 95%CI:1.247–3.126), whereas no significant predictive values were found for women (B = −.036 (S.E. = .221), p > .05, OR:.965, 95%CI:.626–1.487). Also, while attention/speed and total cognitive scores did not significantly predict exposure group membership in the full sample (attention/speed: B = .184 (S.E. = .113), p > .05, OR:1.202, 95%CI:.964–1.498, total cognitive: B = .238 (S.E. = .160), p > .05, OR:1.268, 95%CI:.926–1.737), sex-stratified analyses revealed significant associations among men. For men, higher attention/speed (B = .818 (S.E. = .269), p = .002, OR:2.265, 95%CI:1.337–3.838) and higher total cognitive scores (B = .536 (S.E. = .261), p = .040, OR:1.709, 95%CI:1.026–2.849) were associated with increased odds of being in the middle-childhood exposure group. No significant predictive values were found for women (attention/speed: B = .001 (S.E. = .135), p > .05, OR:1.000, 95%CI:.768–1.303 and total cognitive score: B = −.017 (S.E. = .225), p > .05, OR:.983, 95%CI:.633–1.528).

Furthermore, higher MMSE total scores (B = .130 (S.E. = .040), p = .001, OR:1.139, 95%CI:1.052–1.233), lower CDR total scores (B = −6.260 (S.E. = .394), p = .003, OR:.002, 95%CI:.000–.119), and a lower likelihood of receiving a clinical diagnosis of MCI or dementia (B = −2.793 (S.E. = .225), p = .014, OR:.061, 95%CI:.007–.562) were all associated with higher odds of being in the middle-childhood exposure group.

These findings were generally stronger in men than in women (Women: MMSE total score: B = .084 (S.E. = .055), p > .05, OR:1.088, 95%CI:.977–1.211, CDR Scale score: B = −1.170 (S.E. = .535), p = .029, OR:.310, 95%CI:.109–.885, Diagnosis of MCI or dementia: B = 1.570 (S.E. = .292), p > .05, OR:4.806, 95%CI:.499–46.308, Men: MMSE total score: B = .186 (S.E. = .064), p = .004, OR:1.204, 95%CI:1.062–1.365, CDR Scale score: B = −2.426 (S.E. = .596), p = .017, OR:.088, 95%CI:.012–.647, diagnosis of MCI or dementia: B = −1.450 (S.E. = .288), p = .015, OR:.235, 95%CI:.073–.754).

When adjusting for the Multicomorbidity Index (adjusted model 1), the effects of MMSE, CDR, and, marginally, the Language composite score on middle-childhood exposure remained significant. Attention/speed (B = .811 (S.E. = .271), p = .003, OR:2.251, 95%CI:1.322–3.832) and the total cognitive composite score (B = .535 (S.E. = .265), p = .043, OR:1.708, 95%CI:1.017–2.868) remained significant only for men. Similar results were found when both anxiety and depression (adjusted model 2) were included in the model. As in adjusted model 1, in the adjusted model 2 attention/speed (B = .805 (S.E. = .268), p = .003, OR:2.237, 95%CI:1.323–3.784) and the total cognitive composite score (B = .522 (S.E. = .258), p = .044, OR:1.685, 95%CI:1.015–2.796) remained significant only for men.

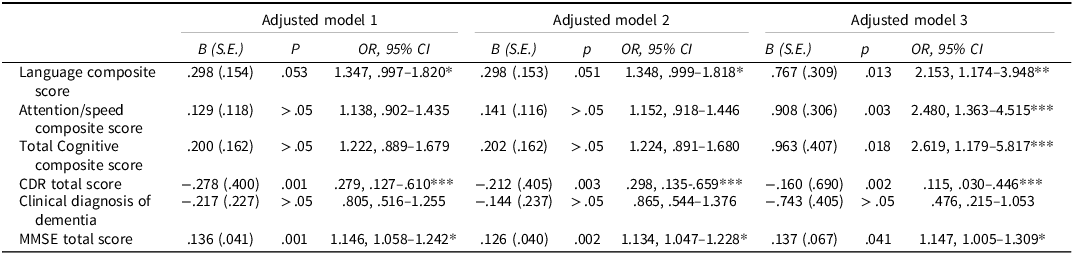

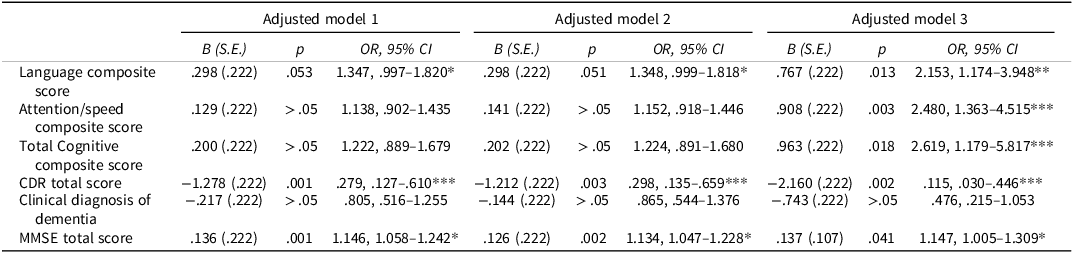

All analyses, with the exception of the clinical diagnosis of MCI or dementia, remained statistically significant when incorporating current smoking and total years of smoking into the models (adjusted Model 3, see Table 2). The covariates by themselves did not appear to explain the variance in the dependent variable in any of the analyses.

Table 2. Logistic regression analyses, controlling for covariates within the early- and middle-childhood exposure groups in the WWII sample

Adjusted Model 1 controls for current age, sex, years of education, and the Multicomorbidity Index. Adjusted Model 2 controls for current age, sex, years of education, anxiety, and depression. Adjusted Model 3 controls for current age, sex, years of education, current smoking status, and total years of smoking.

* Small effect size (OR 1.1–1.5 or 0.67–0.90 inverse), ** Moderate effect size (OR 1.5–2.5 or 0.40–0.67 inverse), *** Large effect size (OR > 2.5 or < 0.40 inverse)

Given the obstacles to attending school at the time, we wondered whether group differences might reflect differential percentages of illiteracy in the two groups. Indeed, chi-squared analyses revealed statistically significant differences with respect to the percentage of illiterate people between the two groups (χ 2 (1) = 18.188, p < .001, Cramér’s V = .127), indicating a higher prevalence of illiterate individuals among those in the group exposed to WWII during middle childhood than those exposed during early childhood. Furthermore, significant differences between the two age groups were found in relation to their mothers’, but not their fathers’, occupation (mothers’ occupation: χ 2 (10) = 21.565, p = .017, Cramér’s V = .138; fathers’ occupation: χ 2 (11) = 7.435, p > .05, Cramér’s V = .082). Specifically, mothers of individuals exposed to war in middle childhood were more likely to be engaged in homemaking, while mothers of those exposed in early childhood tended to be employed as laborers and white-collar civil servants. Participants did not differ in terms of their pre-retirement occupations (χ 2 (11) = 7.099, p > .05, Cramér’s V = .079), genetic predisposition to dementia (χ2(1) = .214, p > .05, Cramér’s V = .030) or the MCI and dementia subtype they were likely to present (MCI subtype: χ 2 (7) = 7.361, p > .05, Cramér’s V = .063, dementia subtype: χ 2 (5) = 6.208, p > .05, Cramér’s V = .037).

Additional analyses were conducted including individuals exposed to WWII during adolescence, to help clarify the reasons for the differences in the two childhood-exposure groups. Higher MMSE scores were associated with increased odds of belonging to the adolescence-exposure group relative to the middle-childhood group B = .028 (S.E. = .038), p = .028, OR:1.086, 95%CI:.1.009–1.169. No significant results were found for clinical diagnosis, CDR total score or composite scores (clinical diagnosis: B = −.228 (S.E. = .203), p > .05, OR:.796, 95%CI:.535–1.185, CDR total score: B = −.166, (S.E. = .299), p > .05, OR:.847, 95%CI:..471–1.521, composite scores: B = .235 (S.E. = .180), p > .05, OR:1.265, 95%CI:.889–1.799, attention/speed B = .113 (S.E. = .109), p > .05, OR:1.119, 95%CI:.904–1.385, language B = .132 (S.E. = .168), p > .05, OR:1.142, 95%CI:.821–1.587, visuospatial B = .138 (S.E. = .115), p > .05, OR:1.148, 95%CI:.917–1.437, Executive B = .107 (S.E. = .163), p > .05, OR:1.112, 95%CI:.807–1.533, memory B = .029 (S.E. = .155), p > .05, OR:1.029, 95%CI:.760–1.393). Sex-stratified analyses indicated that higher MMSE scores predicted increased odds of belonging to the adolescence-exposure group for men B = .123 (S.E. = .050), p = .014, OR:1.131, 95%CI:.1.025–1.248 but not for women B = .039 (S.E. = .055), p > .05, OR:1.040, 95%CI:.933–1.158. The results were marginally significant in adjusted models B = .075 (S.E. = .131), p = .051, OR:1.078, 95%CI:.1.000–1.163.

Civil war

Individuals with better cognitive performance were more likely to belong to the middle-childhood Civil war-exposure group relative to those exposed in early childhood. Specifically, higher visuospatial perception scores (B = .544 (S.E. = .165), p = .001, OR:1.723, 95%CI:1.246–2.381) and higher MMSE total score (B = .134 (S.E. = .057), p = .020, OR:1.143, 95%CI:1.021–1.297) predicted membership in the middle-childhood group. Moreover, lower CDR total scores (B = −2.107 (S.E. = .571), p < .001, OR:.122, 95%CI:.040–.372) and lower odds of a clinical diagnosis of MCI or dementia (B = −.840 (S.E. = .327), p = .010, OR:.432, 95%CI:.227–.819) were also predictive of middle-childhood exposure.

Sex stratification showed that the effects were more pronounced for women than men (Women: visuospatial score: B = .474 (S.E. = .260), p = .012, OR:1.606, 95%CI:1.108–2.329, MMSE total score: B = .185 (S.E. = .072), p = .010, OR:1.204, 95%CI:1.046–1.385, CDR Scale score: B = −2.016 (S.E. = 6.702), p = .003 OR:.133, 95%CI:.035–.499, diagnosis of MCI or dementia: B = −.829 (S.E. = 2.537), p = .044, OR:.436, 95%CI:.194–.980, Men: visuospatial score: B = .798 (S.E. = 2.856), p = .015, OR:2.220, 95%CI:1.167–4.222, MMSE total score: B = .041 (S.E. = .100), p > .05, OR:1.042, 95%CI:.857–1.267, CDR Scale score: B = −2.276 (S.E. = 3.475), p = .024, OR:.103, 95%CI:.014–.744, diagnosis of MCI or dementia: B = −.832 (S.E. = 4.194), p > .05, OR:.435, 95%CI:.153–1.238).

No statistically significant results were found in regard to the memory (B = .050 (S.E. = .154), p > .05, OR:1.051, 95%CI:.778–1.422), executive functioning (B = −.075 (S.E. = .215), p > .05, OR:.928, 95%CI:.609–1.415), language (B = .259 (S.E. = .195), p > .05, OR:1.296, 95%CI:.883–1.901), attention/speed (B = .100 (S.E. = .152), p > .05, OR:1.105, 95%CI:.820–1.488), and total cognitive (B = .339 (S.E. = .221), p > .05, OR:1.404, 95%CI:.911–2.163) composite scores.

Analyses remained significant when adjusting for the Multicomorbidity Index (adjusted model 1) and anxiety and depression (adjusted model 2) but only the visuospatial perception composite score remained significant when incorporating current smoking and total years of smoking into the models (adjusted model 3, see Table 3). The covariates by themselves did not appear to explain the variance in the dependent variable in any of the analyses.

Table 3. Logistic regression analyses, controlling for covariates within the early- and middle-childhood exposure groups in the civil war sample

Adjusted Model 1 controls for current age, sex, years of education, and the Multicomorbidity Index. Adjusted Model 2 controls for current age, sex, years of education, anxiety, and depression. Adjusted Model 3 controls for current age, sex, years of education, current smoking status, and total years of smoking.

* Small effect size (OR 1.1–1.5 or 0.67–0.90 inverse), ** Moderate effect size (OR 1.5–2.5 or 0.40–0.67 inverse), *** Large effect size (OR > 2.5 or < 0.40 inverse).

For statistically significant findings, we assessed practical relevance by interpreting ORs alongside p-values. To classify effect sizes, we used Cohen’s conventional benchmarks for standardized mean differences (d = 0.2 small, 0.5 medium, 0.8 large) and converted these to equivalent OR values using the formula: OR = exp[d × (π/ √ (3))] derived from the original d = [ln(OR) × √ (3)]/π (Cohen, Reference Cohen1988).

This yielded approximate thresholds of OR ≈ 1.44 for a small effect, OR ≈ 2.48 for a medium effect, and OR ≈ 4.27 for a large effect, with inverse associations being the reciprocal of these values. For practical interpretation in epidemiological research, we rounded these values to broader ranges: OR 1.1–1.5 (or 0.67–0.90 for inverse associations) as small, 1.5–2.5 (or 0.40–0.67 inverse) as medium, and > 2.5 (or < 0.40 inverse) as large. For example, in the WWII sample, the association between middle-childhood exposure and higher CDR total scores (OR = 0.28, 95%CI:0.13–0.61) indicates a large effect. Similarly, the total cognitive composite score (OR = 2.62, 95%CI:1.18–5.82) and attention/speed scores (OR = 2.48, 95%CI:1.36–4.52) correspond to medium-to-large effects. In contrast, the association with language composite scores (OR = 1.35, 95%CI:1.00–1.82) reflects a small effect size.

Similarly to WWII groups, chi-squared analyses revealed statistically significant differences with respect to the percentage of illiterate people between the two Civil war-exposure groups (χ 2 (1) = 5.283, p = .022, Cramér’s V = .075), with the group exposed during middle childhood having a higher prevalence of illiteracy than the group exposed during early childhood. Participants also exhibited differences in terms of their pre-retirement occupations (χ 2 (12) = 48.140, p < .001, Cramér’s V = .227). Individuals exposed in middle childhood were more likely to be manual laborers and farmers, while those exposed in early childhood tended to occupy white collar positions like managers and to work in private office settings.

In the childhood age groups exposed to the Civil war, distinctions emerged in terms of the father’s occupation (χ 2 (11) = 45.009, p < .001, Cramér’s V = .222). Fathers of individuals exposed in middle childhood were more likely to be farmers and livestock herders, but fathers of those exposed in early childhood tended to be employed in white-collar positions, like managers, and to work in private office settings. There were no significant differences, however, in terms of the mother’s occupation (χ 2 (10) = 17.331, p > .05, Cramér’s V = .137). After controlling for father’s occupation, the previous significant associations persisted. Specifically, the significant relationships observed in the MMSE total score, CDR total score, clinical diagnosis, and visuospatial perception composite score remained robust. Groups did not differ in terms of their genetic predisposition to dementia (χ 2 (1) = 1.406, p > .05, Cramér’s V = .027), the subtype of dementia they presented (χ 2 (4) = 2.509, p > .05, Cramér’s V = .051) or the subtype of MCI (χ 2 (6) = 7.075, p > .05, Cramér’s V = .086).

Additional analyses included individuals exposed to the Civil war during adolescence to further examine differences between childhood- and adolescence-exposure groups. Higher MMSE scores B = .128 (S.E. = .040), p = .001, OR:1.136, 95%CI:.1.051–1.229 and lower CDR total score B = −1.253 (S.E. = .387), p = .001, OR:.286, 95%CI:.134–.610 predicted increased odds of belonging to the adolescence-exposure group compared to the middle-childhood group. No significant results were observed in terms of clinical diagnosis, or composite scores (clinical diagnosis: B = −.221 (S.E. = .224), p > .05, OR:.801, 95%CI:.526–1.222, Total cognitive composite score: B = .219 (S.E. = .160), p > .05, OR:1.245, 95%CI:.909–1.706, attention/speed B = .169 (S.E. = .113), p > .05, OR:1.184, 95%CI:.949–1.477, language B = .297 (S.E. = .152), p > .05, OR:1.345, 95%CI:.999–1.812, visuospatial B = .011 (S.E. = .130), p > .05, OR:1.011, 95%CI:.783–1.304, executive B = .064 (S.E. = .149), p > .05, OR:1.066, 95%CI:.796–1.428, memory B = .125 (S.E. = .131), p > .05, OR:1.134, 95%CI:.876–1.466). for clinical diagnosis of MCI or dementia (B = −0.221, SE = 0.224, p > .05, OR = 0.80) or cognitive composite scores including total cognitive (B = 0.219, SE = 0.160, p > .05, OR = 1.25), attention/speed (B = 0.169, SE = 0.113, p > .05, OR = 1.18), language (B = 0.297, SE = 0.152, p > .05, OR = 1.35), visuospatial (B = 0.011, SE = 0.130, p > .05, OR = 1.01), executive functioning (B = 0.064, SE = 0.149, p > .05, OR = 1.07), or memory (B = 0.125, SE = 0.131, p > .05, OR = 1.13).

Sex-stratified analyses indicated that higher MMSE scores predicted adolescence-exposure for men B = .180 (S.E. = .063), p=.004, OR:1.197, 95%CI:.1.058–1.355 but not for women B = .083 (S.E. = .054), p > .05, OR:1.087, 95%CI:.977–1.208. The results remained significant in adjusted models B = .131 (S.E. = .040), p = .001, OR:1.140, 95%CI:.1.053–1.234. The results for CDR total score were statistically significant for both sexes (men: B = −1.344 (S.E. = .579), p = .020, OR:.261, 95%CI:.084–.811, women: B = −1.167 (S.E. = .525), p = .026, OR:.311, 95%CI:.111–.871) and remained significant in adjusted models B = −1.164 (S.E. = .393), p = .004, OR:.312, 95%CI:.142–.687.

Discussion

Our findings showed that lower scores on late-life language and attention/speed measures (but not other major cognitive domains) and poorer global screening ratings (with a pronounced male disadvantage) were associated with higher odds of having belonged to early-childhood WWII-exposure (born 1939–1944; under 6 years of age during the war), compared to middle-childhood exposure (born 1934–1938; 6–10 years of age) group. Similarly, having a clinical diagnosis of dementia and a high dementia severity score in old age was associated with higher odds of having belonged to the early-childhood WWII-exposure group. While multicomorbidity, mental health issues, and lifestyle habits (such as smoking) played a significant role in the models, the key results remained significant even after adjusting for these factors. Interestingly, better global cognitive screening scores predicted membership in the adolescence-exposure group (born before 1934) relative to the middle-childhood group, while other cognitive measures did not show significant associations.

A comparable set of findings emerged in the case of the Civil war. Lower late-life cognitive performance, and, specifically, lower visuospatial perception and MMSE scores, meeting criteria for MCI or dementia, and greater severity of clinical dementia symptoms, were associated with higher odds of having belonged to the early-childhood war-exposure (born 1944–1949) relative to the middle-childhood-exposure (1939–1943 cohort) group. As with WWII, mental health issues and multicomorbidity did not substantially alter these associations, although smoking (both current use and duration) did adversely influence outcomes. In this case, fathers of those exposed during middle childhood were more likely to have occupations in farming and livestock herding, whereas fathers of those exposed in early childhood were more often employed in white-collar positions, such as managerial roles or work in private office settings. To account for potential early socioeconomic status disparities, father’s occupation was incorporated into the analysis. While it was a significant factor in all models, its inclusion did not alter the significance level and pattern of our results. Interestingly, better global and clinical cognitive screening scores predicted adolescence-exposure (born before 1939) relative to middle-childhood exposure group membership, while other cognitive measures did not show significant associations.

Thus, our findings overall indicated that lower cognitive performance and higher dementia prevalence in old age were associated with belonging to the early-childhood, war-exposure group, relative to those exposed later in childhood or in adolescence. The assessment of childhood socioeconomic status, though based solely on parents’ occupation, did not appear to be related to the findings. In fact, in some instances it was even lower in high-risk groups and higher in low-risk groups, but still exerted no effect. Moreover, multimorbidity did not have a significant impact on the results. Current smoking and total years of smoking, however, did affect the outcomes. The inclusion of these variables in the analyses led to the disappearance of many associations. While previous studies have identified smoking as a risk factor for dementia (Johnson et al., Reference Johnson, Nystrom, Piper, Cook, Norton, Zuelsdorff, Wyman, Flowers Benton, Lambrou, O’Hara, Chin, Asthana, Carlsson, Gleason and Pase2021), it is important to highlight that in our study, the low-risk groups reported a longer duration of smoking and a higher prevalence of current smoking than the high-risk groups. Whether matching the groups in terms of smoking habits in future studies would alter the outcomes remains unknown. Additionally, there were no significant differences among the groups regarding genetic predisposition to dementia (presence of one or two ε4 alleles or a family history of dementia).

Addressing the hypotheses regarding the underlying reasons for the findings discussed by Knopman (Reference Knopman2020), we identified these differences irrespective of multimorbidity, age, sex, education, mental health issues, and family socioeconomic status during their youth. While there may be additional factors influencing people’s cognitive reserve throughout their lifespan, our findings suggest that the cognitive differences between these cohorts persist regardless of early socioeconomic and current lifestyle, psychological, and medical factors.

Our initial expectation when undertaking the present study was that cognitive benefits would be more pronounced among individuals who had had the opportunity to attend elementary school (1–6 years of school) before experiencing the stress of warfare, thus establishing foundational cognitive skills. Indeed, our study revealed that individuals who might have had some primary schooling during or before the war (the middle childhood and adolescence exposure groups; typically, schools during WWII in Greece operated inconsistently or with long gaps) demonstrated advantages over those who had been too young to have begun school (the early-childhood exposure group), having experienced WWII during infancy and toddlerhood. Yet, paradoxically, the middle-childhood cohort included a higher percentage of illiterate individuals than the early-childhood group with no schooling at all.

This finding suggests that while formal education is generally protective, the timing of exposure to severe early-life stress may have a stronger and more lasting impact on cognitive development. It is possible that the critical brain development occurring in early childhood is especially vulnerable to disruption, which educational attainment later cannot fully offset these detrimental effects. In fact, studies regarding ‘sensitive periods’ of brain development highlight the potential negative impact on the architecture of the developing brain under adverse environmental conditions and experiences (Knudsen, Reference Knudsen2004), with consequent effects on cognition. One biological mechanism underlying this vulnerability may involve dysregulation of the hypothalamic-pituitary-adrenal (HPA) axis. Severe stress during early sensitive periods can lead to prolonged elevation of cortisol and other stress hormones, which negatively affect brain regions critical for cognition such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex. Relevant research has shown that early-life adversity-induced HPA axis dysregulation results in structural and functional brain changes that persist into adulthood, thereby impairing cognitive function despite later environmental enrichment, including education (Huang et al., Reference Huang, Jordan and Zhang2023; Lupien et al., Reference Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar and Heim2009; Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Bhutta, Harris, Danese and Samara2020). This may have been worse for those who were infant-toddlers during WWII, leading to lower resilience than those who were already a little older, the middle-childhood group. This is corroborated by our findings of near equivalence of the adolescence-exposure group to the middle-childhood group, as both presumably were not exposed to the stressful conditions of war and foreign occupation. Thus, our findings may also reflect differential resilience and coping skills in middle versus early-childhood groups. Moreover, previous research has reported the phenomenon of adaptive resilience among children who had experienced cumulative exposure to trauma (Masten et al., Reference Masten, Narayan, Silverman and Osofsky2015).

Similarly supportive of the “adaptive resilience theory” is that the same pattern occurred for the two Civil war cohorts (those exposed in adolescence and middle childhood had better cognitive and clinical/diagnostic outcomes relative to those exposed in early childhood). Interestingly, the middle-childhood cohort in the Civil war comparison was the same as the early-childhood cohort in the WWII comparison meaning that the 1939–1943 cohort had exposure to war in both early- and again in middle childhood (though during middle childhood this group of children were presumably able to attend school). Thus, this pattern might be considered to preclude the interpretation of early exposure and reduced resilience to stress adversely affecting late-life cognition), leaving as the most likely interpretation, that of the enhancing effect of schooling. Yet, as described above, the middle-childhood cohort in this comparison had a higher percentage of illiterate individuals than the early-childhood exposure group, thus vitiating the schooling interpretation.

Of course, the present paradoxical findings may instead reflect cohort differences in mortality rates. Indeed, previous studies have shown that cohorts during war periods had increased infant mortality rates (Gavalas, Reference Gavalas2008), which may have yielded a selection bias in terms of survivors with greater resilience and/or physical/cognitive reserve. Another potential interpretation for the better outcome of the adolescent and middle-childhood WWII cohorts, relative to the younger cohort, may relate to the aftermath of war, which might have had a greater (additive) impact on the latter group, than the active period. There may have been a delayed negative effect inflicted upon children postwar – i.e., war exposure to chemical substances previously found to be inversely associated with visuospatial performance (Proctor et al., Reference Proctor, Heaton, Heeren and White2006). Substances, like carbamates and organophosphates, used as chemical weapons in WWII may have had long-lasting postwar effects. If this were the case, it should have affected all our groups, but differentially relative to their age at the time, with the younger cohorts presumably more vulnerable and the older cohorts more resilient to the chemical effects. In addition, an alternative explanation not discussed by previous scholars relates to potential psychological and/or physical effects of the war aftermath during sensitive developmental periods. While the active period triggers survival skills, in the aftermath, people are left to process, rebuild, and cope with psychological and material losses during early childhood, even infancy. Although no research has examined which period of the two is more traumatizing for children, there is a substantial literature focusing on the period following disasters as crucial for helping children regain stability and process trauma (Osofsky & Osofsky, Reference Osofsky and Osofsky2018), a support system not available during the historical periods of WWII and the Civil war. If this were the case, we would expect it to have affected all our groups, but most likely, again, differentially relative to age, with those who were exposed in adolescence and middle childhood perhaps more resilient than those exposed in early childhood.

Furthermore, our study sex-specific differences in cognitive outcomes following early-life war exposure. Specifically, lower cognitive performance in men, including language, attention/speed, and total cognition, was predictive of belonging to the early-childhood WWII-exposure group, while for women more severe dementia symptoms predicted early- versus middle childhood war exposure group membership but did not show any other significant associations. Conversely, for women exposed to the Civil war, greater resilience, particularly in visuospatial abilities and global cognitive measures, such as the MMSE and clinical dementia ratings, were predictive of middle- versus early childhood war exposure group membership.

The observed patterns in the WWII cohort may reflect underlying sex-specific neurodevelopmental differences. For example, studies have shown that women typically have larger language-related brain regions and greater language processing capacity than men (Lenroot & Giedd, Reference Lenroot and Giedd2010). This neuroanatomical advantage may provide women with greater cognitive reserve in the language domain, potentially buffering them against the detrimental effects of early-life trauma. As a result, men, who generally have smaller language-related brain areas, may be more vulnerable to the impact of war exposure during early childhood, leading to more pronounced deficits in language, attention, and related cognitive functions later in life.

Moreover, sex differences in the HPA axis stress response may contribute to these outcomes. Females generally exhibit heightened and more prolonged cortisol responses to stress compared to males (Kudielka & Kirschbaum, Reference Kudielka and Kirschbaum2005), potentially influencing neural plasticity and cognitive reserve in sex-specific ways. Dysregulation of the HPA axis during sensitive periods of brain development is known to impact regions such as the hippocampus and prefrontal cortex, which are critical for cognition (Lupien et al., Reference Lupien, McEwen, Gunnar and Heim2009). It is plausible that males and females adapt differently to chronic stress exposure during childhood thus, exhibiting distinct cognitive trajectories.

Psychosocial and gender-related prevailing circumstances during wartime also likely played a role in these sex differences. For example, in WWII Greece middle-childhood males might have engaged more than females and younger children in survival-related activities or cognitively demanding tasks, leading to a development of these domains. In contrast, women during the Civil war may have developed and relied upon visuospatial and multitasking skills to manage household and caregiving responsibilities under conditions of severe stress. Additionally, differences in social support and cognitive engagement after the war may further modulate these effects. For example, women typically develop stronger social networks and engagement in varied cognitive activities might underlie the observed advantages in visuospatial function and global cognition after Civil war exposure, despite early adversity (Fratiglioni et al., Reference Fratiglioni, Paillard-Borg and Winblad2004).

Although the precise reasons underlying the outcomes of the present study remain unclear, our findings and conclusions converge on the themes of resilience and adaptability during or after disasters and crises. The implications of our findings emphasize the necessity of gaining a deeper understanding of resilience during childhood, particularly for those who undergo war-related trauma. This knowledge would have practical applications in the development of targeted programs, a consideration especially relevant in the context of recent conflicts throughout the world, where children may face exposure to war-related traumatic events. It also highlights the importance of considering life experiences and their effects on an individual when conducting a clinical neuropsychological assessment, as individual performance is not independent of the context of one’s life.

Existing research indicates that individuals cope with and are impacted by trauma in diverse ways, constituting a potential influencing factor that we did not account for in our analyses. However, our study did uncover sex differences, highlighting the importance of considering this factor in future research. Future studies should also incorporate prospective longitudinal research, especially focusing on individuals exposed to recent war events. Additionally, it is imperative to evaluate the impact of resilience-building programs. In this context, resilience is viewed as a process rather than specific factors, allowing for the development of prevention and intervention strategies that are developmentally sensitive.

Limitations

Our study has certain limitations, including the non-homogeneous nature of the study samples, which may impact the generalizability and reliability of the results. Moreover, reliance on self-reported data for various variables such as occupation, education, comorbidities, and parents’ occupations may have introduced potential biases due to memory difficulties and other limitations related to self-report. It is crucial to note, however, that our primary variables, including cognitive performance, clinical diagnosis of dementia, psychological status, genetic predisposition to dementia, and date of birth, were based on rigorous criteria. These criteria involved the use of neuropsychological and psychological tests and questionnaires, clinical evaluations, state-issued identification cards for birth date verification, and blood analyses. Furthermore, a limitation of our study is the relatively small sample size of participants who were adolescents during WWII. This was primarily due to the age eligibility criteria, as individuals needed to be at least 121 months old by 1940 to be classified in this group, meaning they would have been born around 1930 or earlier. Given the limited number of very elderly participants in our cohort, the adolescent subgroup for WWII exposure is smaller than other groups. This reduced sample size may limit the statistical power and generalizability of findings related to adolescent war exposure, and these results should therefore be interpreted with caution. Nevertheless, they still provide an interesting and useful direction for future research.

Moreover, although we found statistically significant associations between early-life war exposure and later cognitive outcomes, some of the effect sizes were small. This suggests that while the findings are unlikely due to chance, their practical impact may be limited and may not necessitate changes in clinical practice or public health policy. In contrast, medium to large effects observed in some outcomes indicate more meaningful implications for cognitive health policy and interventions.

Funding statement

Alzheimer’s Association, IIRG-09-133014 (NS); Ministry for Health and Social Solidarity and ESPA-EU program Excellence Grant (ARISTEIA), 189 10276/8/9/2011 and Δϒ2β/oικ.51657/14.4.2 (NS); Reinforcement of Research Activities at AUTh, Action D: Reinforcement of Research Activities in the Humanities, Research Committee, Aristotle University of Thessaloniki, Code 89272 (MHK); Research Committee University of Thessaly, Code 2845 (ED).

Competing interests

The authors have no competing interests to report.