Introduction

Parental posttraumatic stress symptoms (PTSS) are a significant risk factor for child emotion regulation (ER) difficulties and impaired socioemotional functioning (Bosquet Enlow et al., Reference Bosquet Enlow, Kitts, Blood, Bizarro, Hofmeister and Wright2011; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Holzer and Hasbun2014), with growing evidence highlighting impaired parenting as a potentially salient mechanism underlying this intergenerational transmission process (Christie et al., Reference Christie, Hamilton-Giachritsis, Alves-Costa, Tomlinson and Halligan2019). Increasingly, researchers recognize emotion socialization – parents’ efforts to shape their children’s abilities to identify, express, and regulate their emotions – as a key process that may be associated with both parental PTSS (Giff et al., Reference Giff, Renshaw, Denham, Martin and Gewirtz2024; Gurtovenko & Katz, Reference Gurtovenko and Katz2020) and child ER (Breaux et al., Reference Breaux, McQuade and Musser2022; Chronis-Tuscano et al., Reference Chronis-Tuscano, Bui and Lorenzo2022). However, no longitudinal studies, to date, have examined the links between parental PTSS, emotion socialization, and child ER difficulties. Further, although PTSS are highly comorbid with depressive symptoms, most studies have not accounted for the role of unique dimensions of trauma-related distress, such as avoidance and intrusion symptoms, in parenting and child outcomes. Addressing this critical gap, the present study examined whether chronic elevations in parental trauma-related distress rooted in pregnancy and unfolding across early childhood – a period characterized by increased risk for PTSS – contributed to child maladaptive ER at the transition to formal schooling through parental emotion socialization processes during the preschool years.

Emotion socialization as a lens for understanding the impact of posttraumatic stress symptoms on child emotion regulation

Eisenberg and colleagues (Reference Eisenberg, Cumberland and Spinrad1998) proposed that parents teach children to regulate emotions through three key processes: emotion expression, discussions of emotion, and responses to children’s emotions. Building on this work, the tripartite model of ER posits that parents impact child ER through the overall emotional climate (e.g., quality of the interparental and parent–child relationships, family emotion expression), modeling of ER (e.g., parents’ emotional displays and interactions), and emotion-related socialization behaviors (ERSBs; Morris et al., Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers and Robinson2007). ERSBs, which comprise both general discussions of emotion (i.e., emotion talk) and specific responses to children’s emotional expressions, represent a salient mechanism through which parents promote child ER. Parental emotion talk fosters greater emotional awareness, knowledge, language, understanding, and self-regulation in children (Denham et al., Reference Denham, Bassett and Wyatt2007; Denham, Reference Denham2023), whereas children whose parents discourage or avoid emotion talk may have fewer opportunities to reflect on and understand their emotions, thereby interfering with their emotion knowledge and self-regulation. Parents’ responses to children’s negative emotions similarly shape child ER, with supportive responses (e.g., accepting and validating negative emotions, providing comfort/distraction, or helping problem-solve) promoting adaptive ER and nonsupportive responses (e.g., dismissing emotions, becoming distressed, or punishing) conferring risk for ER difficulties (Perry et al., Reference Perry, Dollar, Calkins, Keane and Shanahan2020; Shaffer et al., Reference Shaffer, Suveg, Thomassin and Bradbury2012; Tan et al., Reference Tan, Oppenheimer, Ladouceur, Butterfield and Silk2020). Indeed, during toddlerhood and preschool age, nonsupportive responses to children’s negative emotions interfere with child emotion knowledge, ER, and socioemotional functioning (Ornaghi et al., Reference Ornaghi, Pepe, Agliati and Grazzani2019; Thompson et al., Reference Thompson, Zalewski, Kiff, Moran, Cortes and Lengua2020).

Although research on emotion socialization in the context of PTSS is limited, the meta-emotion framework posits that parents’ thoughts and feelings about their own emotions shape their responses to their children’s emotions (Gottman et al., Reference Gottman, Katz and Hooven1996; Katz et al., Reference Katz, Maliken and Stettler2012); that is, parental emotion dysregulation – a key factor in the development and maintenance of PTSS and other psychopathology (Tull et al., Reference Tull, Vidaña and Betts2020) – directly impacts ERSBs. Indeed, a recent systematic review found that parental emotion dysregulation consistently predicted more nonsupportive and fewer supportive responses to children’s negative emotions across both cross-sectional and longitudinal studies, although results for emotion talk were mixed (Edler & Valentino, Reference Edler and Valentino2024). In the context of PTSS, the meta-emotion framework suggests that parents may experience negative emotions as harmful and engage in maladaptive ER strategies (e.g., avoidance, suppression) to manage unwanted thoughts, feelings, and memories (Seligowski et al., Reference Seligowski, Lee, Bardeen and Orcutt2015; Tull et al., Reference Tull, Vidaña and Betts2020). Further, parents who avoid their own emotions may avoid discussing emotions with their children and respond in a more nonsupportive manner to their children’s negative emotions. Notably, research demonstrates that parental PTSS are positively correlated with distress avoidance (e.g., minimizing, ignoring, or displaying low empathy in response to child’s distress; Brockman et al., Reference Brockman, Snyder, Gewirtz, Gird, Quattlebaum, Schmidt, Pauldine, Elish, Schrepferman, Hayes, Zettle and DeGarmo2016), and PTSS may also hinder mindful parenting, which longitudinally predicts ERSBs (McKee et al., Reference McKee, Parent, Zachary and Forehand2018), by impeding emotional awareness during parent–child interactions (Laifer et al., Reference Laifer, DiLillo and Brock2023a).

Despite the potential for PTSS to impact emotion socialization, only two cross-sectional studies have examined this association, with mixed findings. Specifically, Gurtovenko and Katz (Reference Gurtovenko and Katz2020) found that mothers with higher PTSS and decreased physiological ER were more likely to engage in nonsupportive responses with their school-aged children (ages 6 to 12), and maternal PTSS were indirectly associated with fewer supportive responses via lower self-reported ER. In contrast, in a military sample of deployed fathers and non-deployed mothers with children ranging from age 4 to 13, Giff and colleagues (Reference Giff, Renshaw, Denham, Martin and Gewirtz2024) found that fathers’ PTSS were not correlated with their own emotion socialization; however, fathers’ PTSS were associated with more adaptive maternal emotion socialization (e.g., highest levels of supportive responses and expression of positive emotions) when controlling for contextual factors. Because these studies are cross-sectional, the longitudinal impact of PTSS on emotion socialization and subsequent child ER remains unknown. Rigorous longitudinal, multi-method studies examining the impact of parental PTSS on ERSBs – both general emotion talk and specific responses to child distress – and subsequent child ER have the potential to isolate key targets for prevention and intervention efforts to promote optimal parent and child functioning. Given the importance of the early caregiving environment (Humphreys et al., Reference Humphreys, Garon-Bissonnette, Hill, Bailes, Barnett and Hare2024), research examining how chronic elevations in PTSS beginning prior to the birth of the child impact subsequent ERSBs and child ER is critical for preventing the intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation.

Examining posttraumatic stress symptoms across pregnancy and early childhood: methodological considerations

Although pregnancy is often a stressful transition for the family system (Cowan & Cowan, Reference Cowan and Cowan1995), the childbirth experience has been largely overlooked in contemporary psychology research (Saxbe, Reference Saxbe2017). Given that rates of posttraumatic stress disorder (PTSD; i.e., severe and persistent PTSS consistent with diagnostic criteria) are elevated among women during pregnancy and the postpartum (Seng et al., Reference Seng, Rauch, Resnick, Reed, King, Low, McPherson, Muzik, Abelson and Liberzon2010), understanding the impact of PTSS across the perinatal period (i.e., pregnancy to 1-year postpartum) on parenting and early child outcomes is an important endeavor. Indeed, research points toward pregnancy, postpartum, and early parenthood as a potential period of recalibration in the stress response system, which has been implicated in risk for PTSD (Bowers & Yehuda, Reference Bowers, Yehuda and Fink2016), such that women exposed to early life stress may be particularly vulnerable to stressors experienced during the perinatal period, thereby increasing risk for psychopathology (Howland, Reference Howland2023). Further, childbirth itself can be a potentially traumatic event, particularly for women who experience greater objective (e.g., pregnancy and delivery complications) and subjective stress (Dekel et al., Reference Dekel, Stuebe and Dishy2017), with up to one third of women experiencing childbirth-related PTSS (Creedy et al., Reference Creedy, Shochet and Horsfall2000). Although most research focuses on mothers, emerging work suggests fathers may also experience childbirth as traumatic and develop clinically significant PTSS (Golubitsky et al., Reference Golubitsky, Weiniger, Sela, Mouadeb and Freedman2024; Webb et al., Reference Webb, Smith, Ayers, Wright and Thornton2021).

Further demonstrating the importance of research investigating PTSS across pregnancy and early childhood, the perinatal interactional model highlights pregnancy as a critical window for disrupting the intergenerational transmission of trauma symptoms (Lang & Gartstein, Reference Lang and Gartstein2018). According to this model, parental expressiveness, a key component of the family emotional climate, may impact child ER by modeling more intense expressions of emotion and maladaptive ER strategies (e.g., avoidance, withdrawal). PTSS may also confer risk for nonsupportive ERSBs (i.e., insensitivity to child distress) across infancy and early childhood, thereby contributing to both greater child distress and ER difficulties.

Despite growing recognition of the perinatal period as a time of heightened risk for PTSS and a key opportunity for prevention efforts, extant research is limited by key methodological constraints. First, although PTSD is highly comorbid with depression (Flory & Yehuda, Reference Flory and Yehuda2015), few studies have isolated the unique effects of perinatal PTSS on parenting and child outcomes after accounting for depressive symptoms, yielding mixed findings. Some research has linked maternal perinatal PTSS to infant emotion dysregulation and impaired toddler socioemotional development (Bosquet Enlow et al., Reference Bosquet Enlow, Kitts, Blood, Bizarro, Hofmeister and Wright2011; Garthus-Niegel et al., Reference Garthus-Niegel, Ayers, Martini, von Soest and Eberhard-Gran2017), as well as deficits in mindful parenting during toddler age (Laifer et al., Reference Laifer, DiLillo and Brock2023a); other studies attribute bonding impairments primarily to depression, regardless of PTSD comorbidity (Muzik et al., Reference Muzik, Morelen, Hruschak, Rosenblum, Bocknek and Beeghly2017). Second, research tends to focus on childbirth-related PTSD, thereby overlooking the potential for routine stressors across pregnancy and childbirth (e.g., pregnancy and delivery complications) to trigger or exacerbate PTSS (Grekin & O’Hara, Reference Grekin and O’Hara2014; Laifer et al., Reference Laifer, O’Hara, DiLillo and Brock2023b). Finally, theoretical conceptualizations of perinatal PTSS do not adequately address the overlap between trauma-related symptoms, depression, and normative postpartum experiences (i.e., irritability and sleep disturbances; Grekin & O’Hara, Reference Grekin and O’Hara2014). Thus, research conducted within a dimensional framework is integral to understanding how specific dimensions of PTSS impact subsequent parenting and child ER difficulties.

Addressing these limitations, the Hierarchical Taxonomy of Psychopathology (HiTOP) model conceptualizes the comorbidity of PTSS and depressive symptoms as the result of underlying negative affectivity shared across internalizing disorders (Conway et al., Reference Conway, Forbes, Forbush, Fried, Hallquist, Kotov, Mullins-Sweatt, Shackman, Skodol, South, Sunderland, Waszczuk, Zald, Afzali, Bornovalova, Carragher, Docherty, Jonas, Krueger and Eaton2019; Rademaker et al., Reference Rademaker, van Minnen, Ebberink, van Zuiden, Hagenaars and Geuze2012). Within this framework, avoidance and intrusion symptoms are recognized as specific dimensions of trauma-related distress, whereas other PTSS (i.e., hyperarousal and negative alterations in cognition and mood, both of which overlap with depressive symptoms and normative postpartum experiences) are neither specific to nor necessary for diagnosing PTSD (Watson & O’Hara, Reference Watson, O’Hara, Watson and O’Hara2017). This dimensional approach also addresses limitations of prior research, which largely collapses across symptom clusters and focuses on individuals who meet diagnostic criteria or have higher rates of PTSD (e.g., military populations), thereby overlooking the potential for subthreshold elevations in specific dimensions of trauma-related distress to uniquely impact parenting and child outcomes.

Finally, existing work has not examined perinatal PTSS beyond 1-year postpartum (Heyne et al., Reference Heyne, Kazmierczak, Souday, Horesh, Lambregtse-van den Berg, Weigl, Horsch, Oosterman, Dikmen-Yildiz and Garthus-Niegel2022). Given research demonstrating that (a) both the chronicity and severity of parental psychopathology impact child outcomes (Brennan et al., Reference Brennan, Hammen, Andersen, Bor, Najman and Williams2000) and (b) parental psychopathology across the early childhood years predicts socioemotional outcomes across childhood (Maughan et al., Reference Maughan, Cicchetti, Toth and Rogosch2007; Vakrat et al., Reference Vakrat, Apter-Levy and Feldman2018), there is a clear need for research examining chronic elevations in trauma-related distress across pregnancy and early childhood using repeated measures designs. Because parents engage more regularly with the healthcare system during pregnancy and across early childhood and may have increased motivation for change (Lindqvist et al., Reference Lindqvist, Lindkvist, Eurenius, Persson and Mogren2017), such work could clarify the value of screening for trauma-related distress during obstetric and well-child visits and guide preventive interventions to prepare pregnant couples for the pregnancy–postpartum transition.

The present study

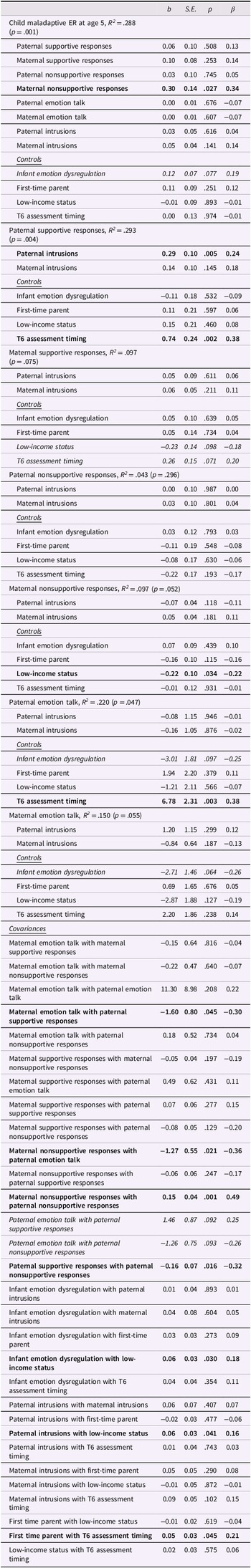

The present study sought to investigate whether specific dimensions of parental trauma-related distress (i.e., avoidance and intrusions) across pregnancy and early childhood (i.e., toddler age) increase risk for child maladaptive ER at the transition to formal schooling through parental emotion socialization processes during the preschool years (see Figure 1). Building on past research and theory, we hypothesized that parental trauma-related distress would be associated with fewer supportive responses to children’s negative emotions, more nonsupportive responses, and less emotion talk. We also hypothesized that more supportive responses and emotion talk would be associated with lower levels of child maladaptive ER, whereas more nonsupportive responses would be associated with greater child maladaptive ER. Further, we expected that nonsupportive responses to children’s negative emotions would emerge as a unique and salient mechanism through which chronic elevations in parental trauma-related distress confer risk for child maladaptive ER when controlling for other ERSBs (i.e., within an integrated model). The present study incorporates several strengths. First, the longitudinal design spanning the prenatal period to the transition to formal schooling has the potential to isolate salient early risk factors for maladaptive child outcomes. Second, by examining both mothers and fathers as socializing agents, the present study provides an opportunity to understand how chronic elevations in trauma-related distress across pregnancy and early childhood impact ERSBs and child ER within a family systems framework. Third, research examining emotion socialization as a multifaceted construct allows for the identification of unique pathways through which parental trauma-related distress confers risk for child maladaptive ER. Fourth, the preschool years represent a sensitive period for parental ERSBs, with supportive responses promoting socioemotional adjustment among preschoolers but not school-age children (Mirabile et al., Reference Mirabile, Oertwig and Halberstadt2018). Finally, the transition to formal schooling represents a unique period of risk, during which children confront new academic, socioemotional, and behavioral challenges (Rimm-Kaufman et al., Reference Rimm-Kaufman, Curby, Grimm, Nathanson and Brock2009; Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, Reference Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta2000). Thus, research examining early developmental pathways that confer risk for maladaptive ER at the transition to formal schooling is vital. Taken together, this research has the potential to inform prevention and intervention efforts promoting parental wellbeing across the perinatal period, adaptive parenting during early childhood, and child ER at the transition to formal schooling.

Figure 1. Conceptual model linking parental trauma-related distress spanning pregnancy to toddler age (i.e., 2-years postpartum) to child maladaptive emotion regulation at the transition to formal schooling (i.e., 5 years) through emotion-related socialization behaviors (ERSBs) at preschool age (i.e., 3 years).

Method

Participants and procedure

Participants were recruited via flyers and brochures and were eligible if they were (a) 19 years of age or older (legal age of adulthood in Nebraska), (b) English speaking, (c) pregnant at the time of the initial appointment, (d) both biological parents of the child, (e) pregnant with one child, and (f) in a committed relationship and cohabiting. One hundred sixty-two mixed-sex couples enrolled during pregnancy. Three couples were excluded due to either ineligibility or invalid data, resulting in a sample of 159 couples (159 women and 159 men). Demographic characteristics of the sample are reported in a supplemental table available here: https://osf.io/x2avn/. All participants identified as cisgender at study entry, and the majority of couples were married (84.9%). Upon study entry, mothers were, on average, 28.67 years of age (SD = 4.27), and fathers were 30.56 years of age (SD = 4.52). Most mothers (83.6%) and fathers (84.3%) identified as White and non-Hispanic/Latino; 5.7% of mothers and 3.2% of fathers identified as White and Hispanic/Latino; 0.6% of mothers and 3.8% of fathers identified as Black or African American; 2.5% of mothers and fathers identified as Asian; 0.6% of mothers and fathers identified as American Indian or Alaskan Native; and 6.9% of mothers and 5.7% of fathers identified as more than one race. Modal education was a bachelor’s degree (46.5% of mothers and 34.6% of fathers). Annual household income ranged from less than $9,999 to more than $90,000, with a median household income of $60,000 to $69,999. After adjusting for household size, nearly half (49.1%) of couples met federal guidelines for low-income status. Although the sample was not selected for trauma exposure, 67% of mothers and 70% of fathers reported direct exposure to a potentially traumatic event (e.g., natural disaster, physical assault, sexual assault) as defined by an affirmative response to at least one item on the Life Events Checklist for DSM-5 (LEC-5; items 1 – 16; Weathers et al., Reference Weathers, Blake, Schnurr, Kaloupek, Marx and Keane2013) at study enrollment. At follow-up assessments, it was determined that one mother experienced a miscarriage, and one child had been diagnosed with trisomy 21. As such, those participants were excluded for a final sample of 157 families with typically developing children (50.3% female, n = 149).

Data were collected across seven waves spanning pregnancy to child age 5. Mothers and fathers completed self-report measures assessing parental trauma-related distress during pregnancy (M = 28.03 weeks, SD = 7.75) and at 1-month (M = 1.12 months, SD = 0.29), 6- months (M = 6.32 months, SD = 0.36), 1-year (M = 12.80 months, SD = 0.76), and 2-years postpartum (M = 24.50 months, SD = 0.66). With regards to attrition, 92.4% of eligible families participated at 1-month postpartum, 89.2% participated at 6-months postpartum, and 77.1% participated at 1-year and 2-years postpartum. When children turned 3 years of age (M = 44.28 months, SD = 2.50), families attended a 3.5-hour laboratory visit, during which parents completed a questionnaire assessing specific responses to child distress and parent–child dyads completed the Emotion Picture Book task (van der Pol et al., Reference van der Pol, Groeneveld, Endendijk, van Berkel, Hallers-Haalboom, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Mesman2016) to assess parental emotion talk. Notably, the 3-year assessment was underway when the United States declared a national emergency in response to the coronavirus disease 2019 (COVID-19), and 25 families had already completed the in-person laboratory appointment. To approximate in-person procedures, parents who participated after the COVID-19 pandemic began (41 mothers and 29 fathers) were shown the Emotion Picture Book via Zoom and were instructed to say “next” or “back” to turn the pages of the book during the virtual appointment. Of the 157 eligible families, 54.8% participated in at least one part of the assessment (i.e., questionnaire alone or the questionnaire and observational task). Finally, when children turned 5 years of age (M = 65.13 months, SD = 0.87), mothers and fathers completed a questionnaire assessing child ER, with 62.4% of eligible families participating in the assessment. Each parent was compensated up to $475 ($50 at pregnancy, $25 at 1 month, $50 at 6 month, $100 at child ages 1 through 3, and $50 child age 5).

Measures

Parental trauma-related distress across pregnancy and toddler age

Mothers and fathers completed the Inventory of Depression and Anxiety Symptoms (IDAS-II; Watson et al., Reference Watson, O’Hara, Naragon-Gainey, Koffel, Chmielewski, Kotov, Stasik and Ruggero2012) to assess trauma-related distress across five timepoints spanning pregnancy to 2-years postpartum. Participants indicated the extent to which they experienced symptoms over the past two weeks on a scale ranging from 1 (not at all) to 5 (extremely). The IDAS-II includes two 4-item scales assessing traumatic avoidance (e.g., attempts to avoid distressing thoughts, memories, and external reminders related to the trauma) and traumatic intrusions (e.g., nightmares, flashbacks), with total scores for each subscale ranging from 4 to 20 (αs ranging from .75 to .89 across waves). The IDAS-II subscales show significant convergent validity with and demonstrate stronger criterion validity and better diagnostic specificity for PTSD than the avoidance and intrusions subscales of the PTSD Symptom Checklist (Watson & O’Hara, Reference Watson, O’Hara, Watson and O’Hara2017). Further, consistent with the HiTOP model, these subscales allow researchers to isolate specific dimensions of trauma-related distress that are not confounded with higher-order negative affectivity (Stasik-O’Brien et al., Reference Stasik-O’Brien, Brock, Chmielewski, Naragon-Gainey, Koffel, McDade-Montez, O’Hara and Watson2019). In the present sample, participants who did not report direct exposure to a potentially traumatic event on the LEC-5 endorsed virtually no trauma-related distress (median = 4, mode = 4).

Parental emotion socialization

When children were 3 years of age, mothers and fathers completed the Coping with Children’s Negative Emotions Scale (CCNES; Fabes et al., Reference Fabes, Poulin, Eisenberg and Madden-Derdich2002) to assess their typical responses to their preschoolers’ negative emotions (e.g., anger, sadness, fear). Parents indicated how likely they were to respond to their child’s negative emotions on a scale of 1 (very unlikely) to 7 (very likely) for 12 age-appropriate, hypothetical scenarios. The CCNES consists of six subscales corresponding to theoretically distinct responses to children’s negative emotions: distress reactions, punitive reactions, expressive encouragement, emotion-focused reactions, problem-focused reactions, and minimization reactions. Consistent with established procedures, scores were aggregated across supportive (expressive encouragement, emotion-focused reactions, and problem-focused reactions; α=.94) and nonsupportive subscales (distress reactions, punitive reactions, and minimization reactions; α = .87).

Mothers’ and fathers’ discussions of emotion were observed during the Emotion Picture Book task (van der Pol et al., Reference van der Pol, Groeneveld, Endendijk, van Berkel, Hallers-Haalboom, Bakermans-Kranenburg and Mesman2016). Consistent with established procedures, two versions of the book (A and B) were used, and both books consisted of drawings of gender-neutral children displaying anger, fear, sadness, and happiness. The child completed version A with one parent and version B with the other, and the order in which parents completed the task was counterbalanced. Each parent was given five minutes to discuss the pictures in the book without further instructions. Two research assistants transcribed the parent–child interactions, and parental emotion talk was assessed using the Parent–child Affect Communication Task coding system (Zahn-Waxler et al., Reference Zahn-Waxler, Ridgeway, Denham, Usher and Cole1993), which has demonstrated reliability and validity with preschoolers (e.g., Denham et al., Reference Denham, Cook and Zoller1992; Zahn-Waxler et al., Reference Zahn-Waxler, Ridgeway, Denham, Usher and Cole1993). Two coders counted words referring to discrete positive or negative emotions (e.g., sad, happy) or to behavioral expressions of emotion (e.g., crying). After a consistent pattern of agreement was observed among coders, approximately 20% of cases were double coded to establish reliability. We created a total score of emotion talk by summing words across emotion categories, and scores demonstrated adequate interrater reliability (mean ICC = .96; ICCs > .76 across emotion categories).

Child maladaptive emotion regulation

When children turned 5 years of age, mothers and fathers completed the Emotion Regulation Skills Questionnaire (ERSQ; Mirabile & Thompson, Reference Mirabile and Thompson2011; Mirabile, Reference Mirabile2014). Parents rated the extent to which their child engaged in specific behaviors in response to different feelings (i.e., anger, sadness, fear, and happiness) on a scale of 0 (not true) to 4 (almost always). The ERSQ consists of 13 subscales and two composite scores reflecting adaptive and maladaptive regulatory strategies. For our primary analyses, we computed an aggregate score for maladaptive ER specific to negative emotions (i.e., anger, sadness, and fear; α = .78) to mirror the format of the CCNES. We also computed an aggregate score for adaptive regulatory strategies specific to negative emotions (α = .83), which was examined as an outcome variable in sensitivity analyses. Maternal and paternal reports of child ER were significantly correlated (r = .42 for both maladaptive and adaptive ER) and were aggregated to create robust measures of child maladaptive and adaptive ER. Aggregating scores from multiple informants produces a less biased and more reliable estimate while also favoring parsimony and increasing statistical power (Hoyt, Reference Hoyt2000; Lengua et al., Reference Lengua, Bush, Long, Kovacs and Trancik2008). To control for early emotion dysregulation, we regressed maladaptive ER at age 5 on the 6-item falling reactivity subscale of the Infant Behavior Questionnaire-Revised (IBQ-R; Gartstein & Rothbart, Reference Gartstein and Rothbart2003) at 6-months and 1-year postpartum. We reverse scored the falling reactivity subscale, such that higher scores reflected greater infant emotion dysregulation (α = .81 and .85 at 6-months and 1-year postpartum, respectively). Maternal and paternal scores were aggregated across time to create robust scores of infant emotion dysregulation.

Covariates and inclusion of disrupted families

Several theoretically relevant demographic variables (e.g., age, minoritized racial/ethnic identity, adjusted low-income status, first-time parenthood, child sex, parental separation at child age 5) were considered as covariates. Variables that were significantly associated with both a predictor and an outcome variable were included as covariates. We included timing of the 3-year assessment (pre-pandemic = 0, post-pandemic onset = 1) as a covariate.

Data analytic plan

Longitudinal structural equation modeling was used in Mplus Version 8.6 (Muthén & Muthén, Reference Muthén and Muthén2017), and we implemented maximum likelihood estimation with robust standard errors (MLR) to address missing data and non-normality. With regard to missing data, covariance coverage (i.e., proportion of available data for a given pair of variables) ranged from 0.32 to 1.00. No demographic variables had correlations with missingness that exceeded the recommended threshold for inclusion as auxiliary variables to address systematic missingness (r > .40; Enders, Reference Enders2010). Data were analyzed using actor-partner interdependence modeling for distinguishable dyads (Kenny et al., Reference Kenny, Kashy, Cook, Kenny, Kashy and Cook2006), such that the couple was the unit of analysis. There were two actor effects (e.g., paternal trauma-related distress → paternal ERSBs; maternal trauma-related distress → maternal ERSBs) and two partner effects (e.g., paternal trauma-related distress → maternal ERSBs; maternal trauma-related distress → paternal ERSBs) to link any two variables together in the model. There were no a priori hypotheses for partner effects. The model also included correlations between (a) exogenous variables (e.g., maternal trauma-related distress and paternal trauma-related distress) and (b) residuals of endogenous variables (e.g., maternal ERSBs and paternal ERSBs). Mediation was tested with a nonparametric resampling method (bias-corrected bootstrapping) with 10,000 resamples to derive the 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for indirect effects.

As a preliminary step, we created separate latent variables for each dimension of maternal and paternal trauma-related distress (i.e., avoidance and intrusions) using five repeated measures spanning pregnancy to toddler age, thereby capturing stability and consistency of trauma-related distress. Given the analytic complexity of the mediation models tested, relative to sample size, factor scores for the latent trauma-related distress variables were exported and modeled as observed variables in subsequent analyses. Notably, factor scores had near perfect or perfect correlations with the latent variables (rs ranged from .999 to 1.00). Child maladaptive ER at age 5 was regressed on parental ERSBs at preschool age, infant emotion dysregulation, and the exported factors scores for maternal and paternal trauma-related distress. Parental ERSBs were also regressed on infant emotion dysregulation to account for the potential for infant regulatory difficulties to undermine parenting (Bailes & Leerkes, Reference Bailes and Leerkes2023). We tested separate models for avoidance and intrusions, respectively.

Data management and analytic procedures for this project were preregistered at https://osf.io/hprk8. Given that we had prior knowledge of data from this longitudinal study, we did not preregister study hypotheses. The original sample of 159 couples and their children was powered to detect relatively small effects in regression analyses (effect size r = .19, power = .80, α = .05). Using pilot data with proxy measures for study variables, we obtained parameter estimates for the hypothesized models to use in Monte Carlo simulations to estimate statistical power for the present study (Thoemmes et al., Reference Thoemmes, MacKinnon and Reiser2010). We selected estimates of missing data based on prior waves of data collection and directly modeled this in the power analysis. The final analytic sample of n = 157 resulted in sufficient power (ranging from .841 to .866) to detect even the smallest hypothesized effects (standardized estimates as low as 0.25) despite attrition.

We also conducted analyses to determine whether hypothesized effects differed across mothers and fathers. Specifically, we constrained any two parallel paths (e.g., maternal trauma-related distress→ maternal ERSBs; paternal trauma-related distress→ paternal ERSBs) to be equal across partners and compared the model fit to the fit of a model with all paths freely estimated. Because we used MLR, we computed Satorra–Bentler scaled chi-square difference tests (Satorra & Bentler, Reference Satorra and Bentler2010). A non-significant chi-square difference test suggests that model fit is not improved by allowing paths to differ across partners.

Results

Descriptive statistics and correlations between repeated measures of trauma-related distress are reported in Supplemental Table 1. To obtain scores of chronic elevations in trauma-related distress, we modeled repeated scores of trauma-related distress at pregnancy and four postpartum timepoints as indicators of latent variables for paternal avoidance, maternal avoidance, paternal intrusions, and maternal intrusions. Ultimately, scores at 1-year postpartum were excluded from the latent variable models, as the paternal models would not converge with an admissible solution due to severely restricted ranges in scores. Model results are reported in Supplemental Table 2 and demonstrate excellent global fit, with factor loadings ranging from 0.27 to 1.00. Factor scores were then exported and included as observed variables in the subsequent analyses.

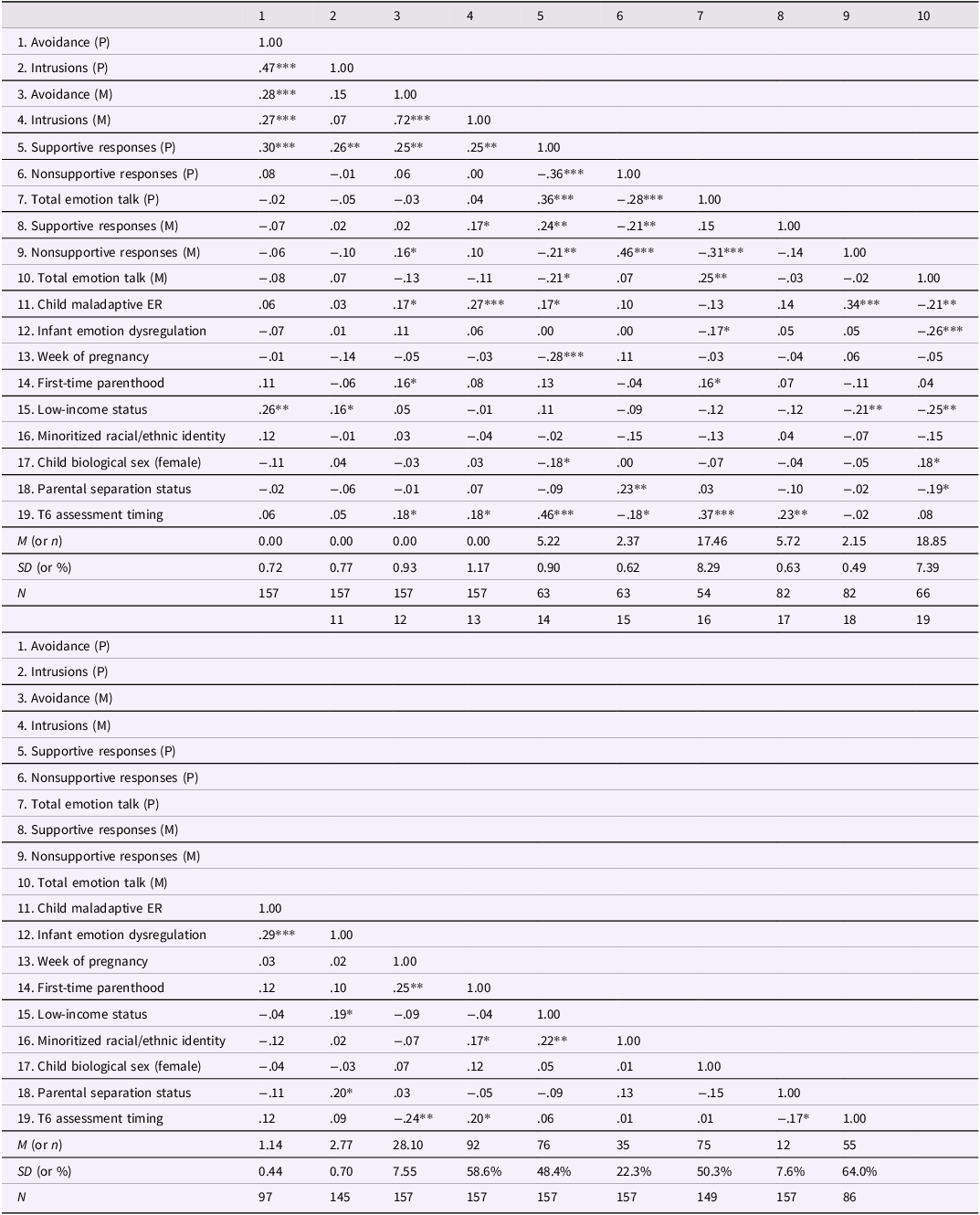

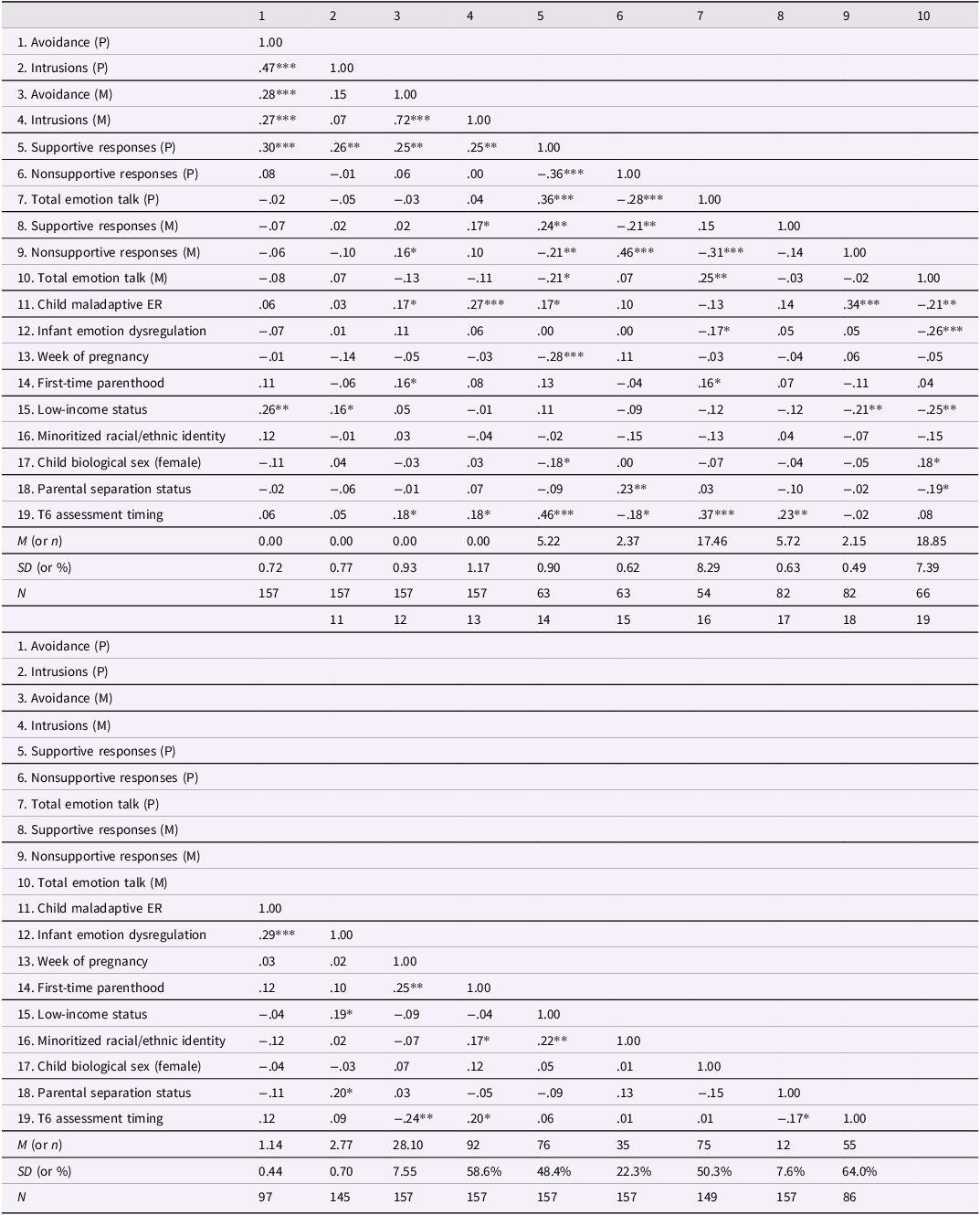

Correlations between the exported factor scores, primary study variables (i.e., parental ERSBs and child maladaptive ER), and potential covariates are presented in Table 1. Contrary to expectations, at the bivariate level, paternal trauma-related distress was significantly correlated with greater paternal supportive responses, and no significant associations emerged between paternal trauma-related distress and nonsupportive responses or emotion talk. Maternal avoidance was significantly correlated with greater maternal nonsupportive responses, and maternal intrusions were significantly correlated with greater maternal supportive responses. Greater paternal supportive responses, greater maternal nonsupportive responses, and less maternal emotion talk were significantly correlated with greater child maladaptive ER. Paired sample t-tests revealed that, on average, there were not significant differences in chronic trauma-related distress levels between mothers and fathers. However, on average, mothers endorsed more supportive responses than fathers, t(58) = −3.89, p < .001, whereas fathers endorsed more nonsupportive responses than mothers, t(58) = 4.72, p < .001. Mothers and fathers did not significantly differ in total observed emotion talk.

Table 1. Descriptive statistics and correlations for primary study variables and potential covariates

Note. P = paternal, M = maternal, ER = emotion regulation, T6 = child age 3. Avoidance and intrusions reflect exported factor scores. Parental separation status was measured at child age 5 and coded as 0 (in tact) or 1 (separated). T6 assessment timing was coded as 0 (pre-pandemic) and 1 (post-pandemic onset). Low-income status was dichotomized based on the median household income (relative to household size) in Nebraska at the time of study enrollment. Minoritized racial/ethnic identity was coded as 0 (both parents identified as White and non-Hispanic/Latino) or 1 (at least one parent identified as non-White or Hispanic/Latino).

* p < .05, ** p < .01, *** p < .001.

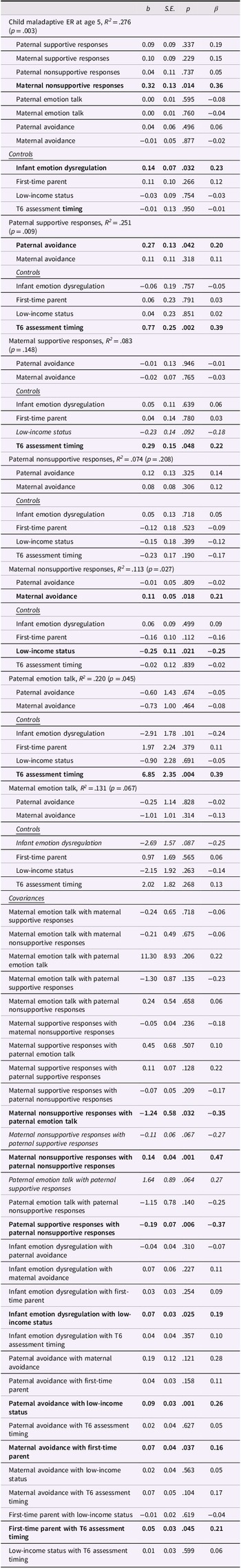

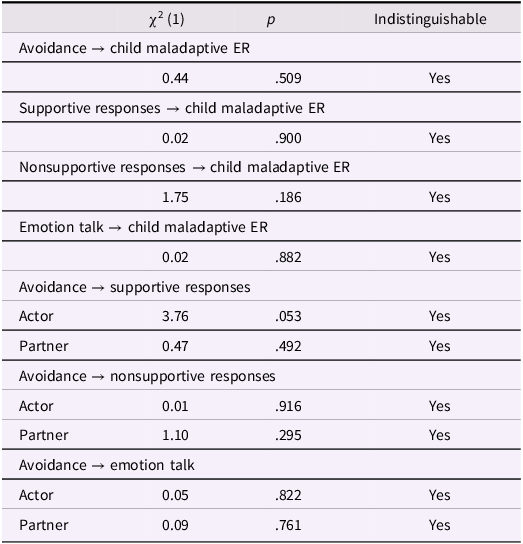

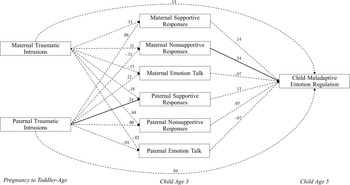

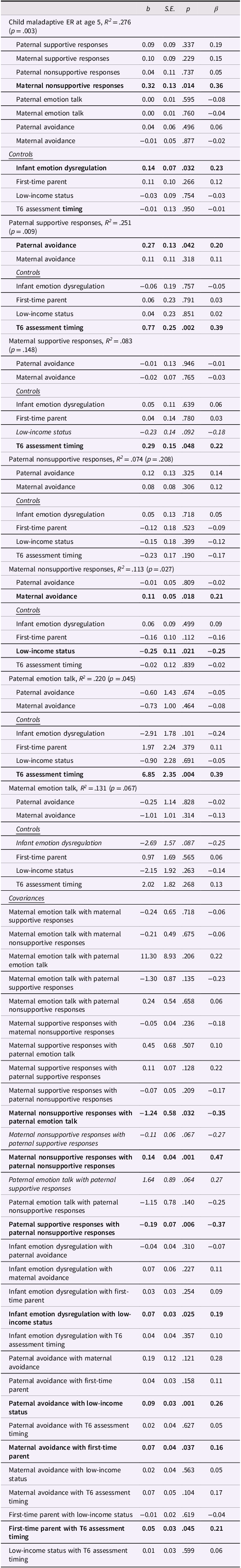

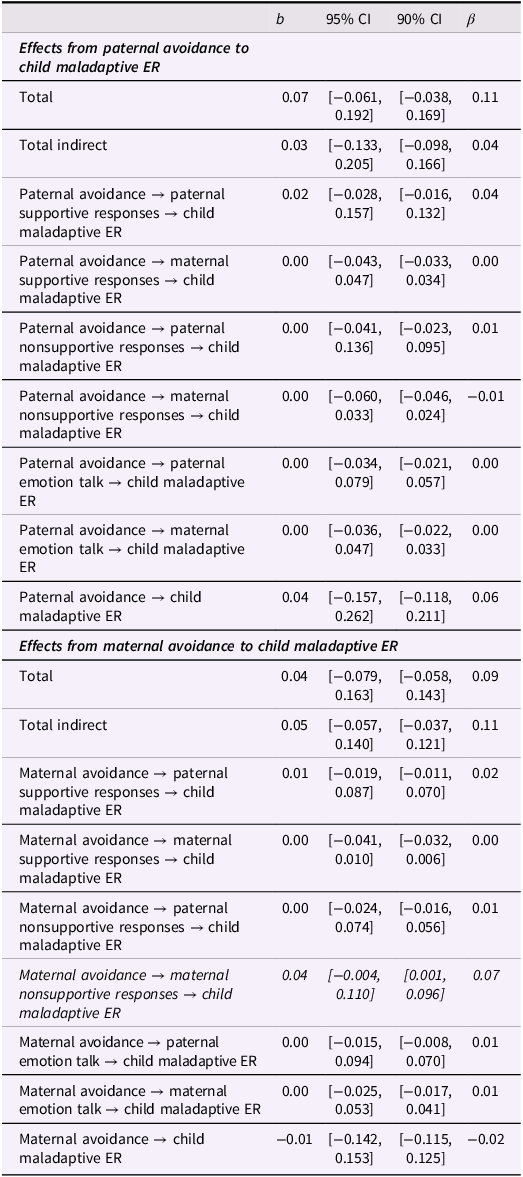

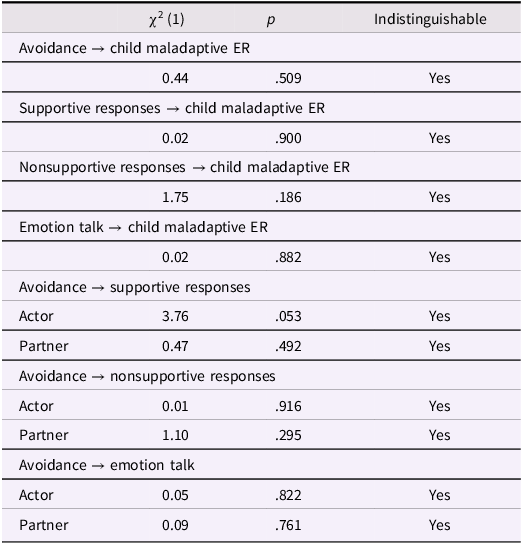

Full model results for avoidance are reported in Table 2 and depicted in Figure 2. Controlling for infant emotion dysregulation, first-time parenthood, low-income status, and timing of the preschool-age assessment, there was a significant effect of maternal avoidance across pregnancy and toddler age on maternal nonsupportive responses (b = 0.11, S.E. = 0.05, p = .018), and, in turn, maternal nonsupportive responses were significantly associated with greater maladaptive ER at child age 5 (b = 0.32, S.E. = 0.13, p = .014). Although the indirect effect of maternal avoidance on greater child maladaptive ER through nonsupportive responses was not significant based on the 95% CI [−0.004, 0.110], the 90% CI did not contain zero [0.001, 0.096]. Notably, higher levels of paternal avoidance uniquely predicted greater paternal supportive responses (b = 0.27, S.E. = 0.13, p = .042) within the integrated model. No partner effects emerged; that is, one parent’s avoidance symptoms were not significantly associated with the other parent’s ERSBs. Total and indirect effects are reported in Table 3. Tests of indistinguishability suggested that there were no significant differences in the unstandardized estimates for paths between partners apart from the path from intrusions to supportive responses to children’s negative emotions (see Table 4).

Table 2. Integrated model results for avoidance

Note. b = unstandardized estimate, β = standardized estimate, ER = emotion regulation, T6 = child age 3. Significant effects based on p < .05 are bolded, and significant effects based on p < .10 are italicized.

Figure 2. Results of Integrated Model for Avoidance. Note. Model results controlling for infant emotion dysregulation, first-time parenthood, low-income status, and whether the preschool-age assessment occurred after the onset of COVID. Significant paths are depicted by solid lines. Exogenous variables were allowed to covary in the model but were not significant. Residuals for endogenous variables were correlated at each time point but are omitted from the figure for ease of presentation.

Table 3. Total, direct, and indirect effects from avoidance to child maladaptive emotion regulation

Note. b = unstandardized estimate, β = standardized estimate, ER = emotion regulation. Significant effects based on the 90% CI (90% CI does not include zero) are italicized.

Table 4. Indistinguishability of specific paths in integrated model for avoidance

Note. ER = emotion regulation. Paths were tested for indistinguishability across mothers and fathers. Actor = within person effect (e.g., maternal avoidance predicting maternal supportive responses). Partner = across partner effect (e.g., maternal avoidance predicting paternal supportive responses).

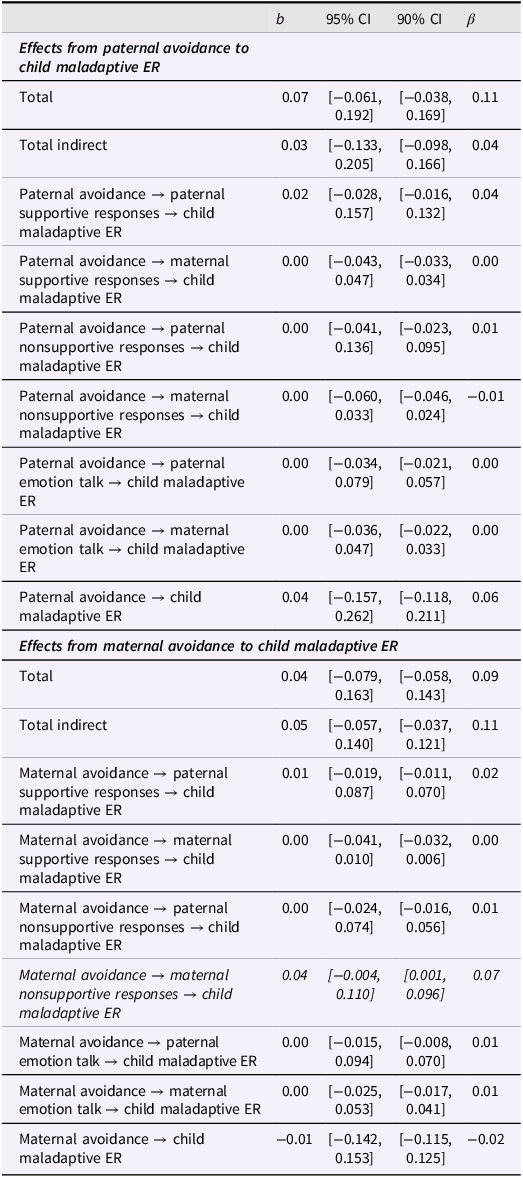

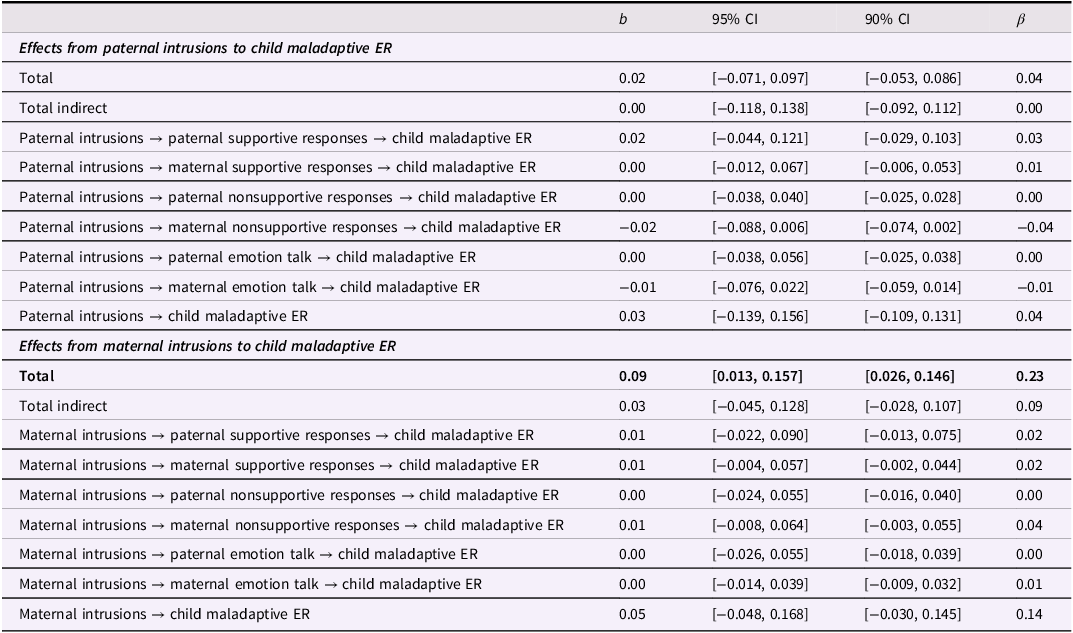

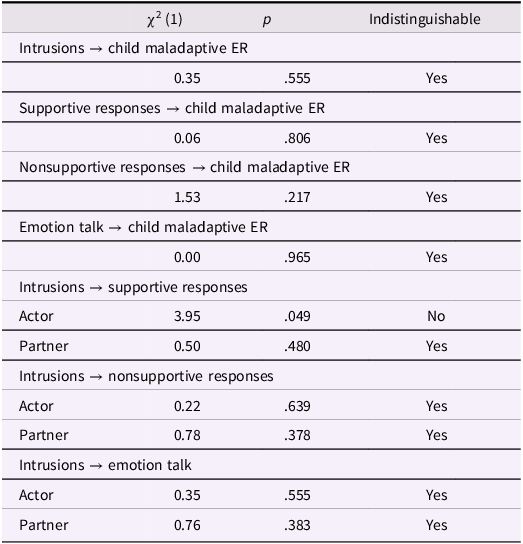

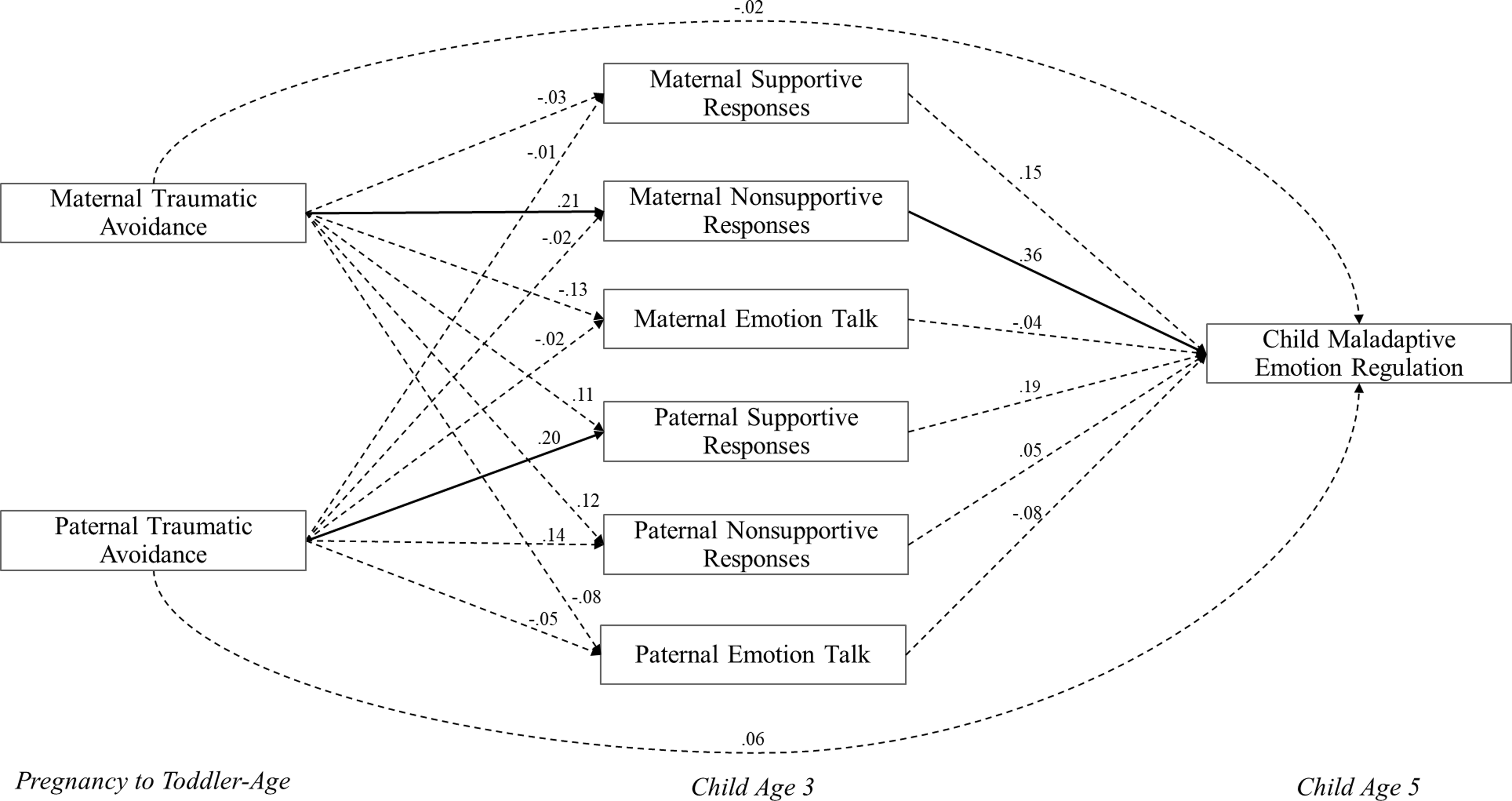

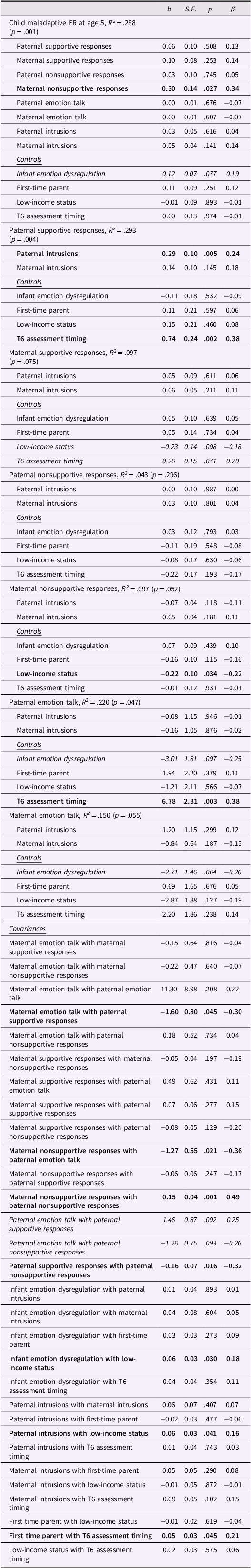

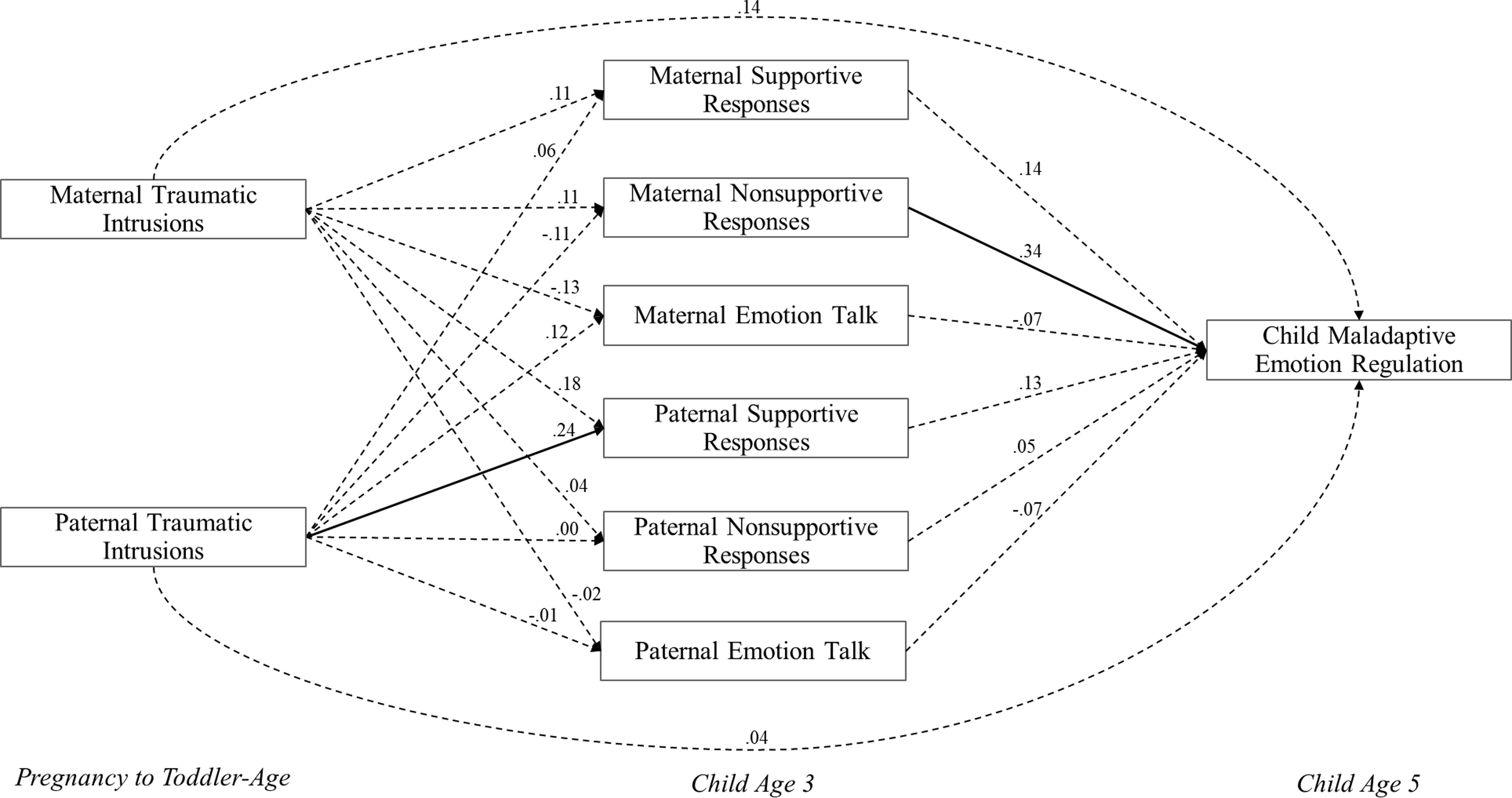

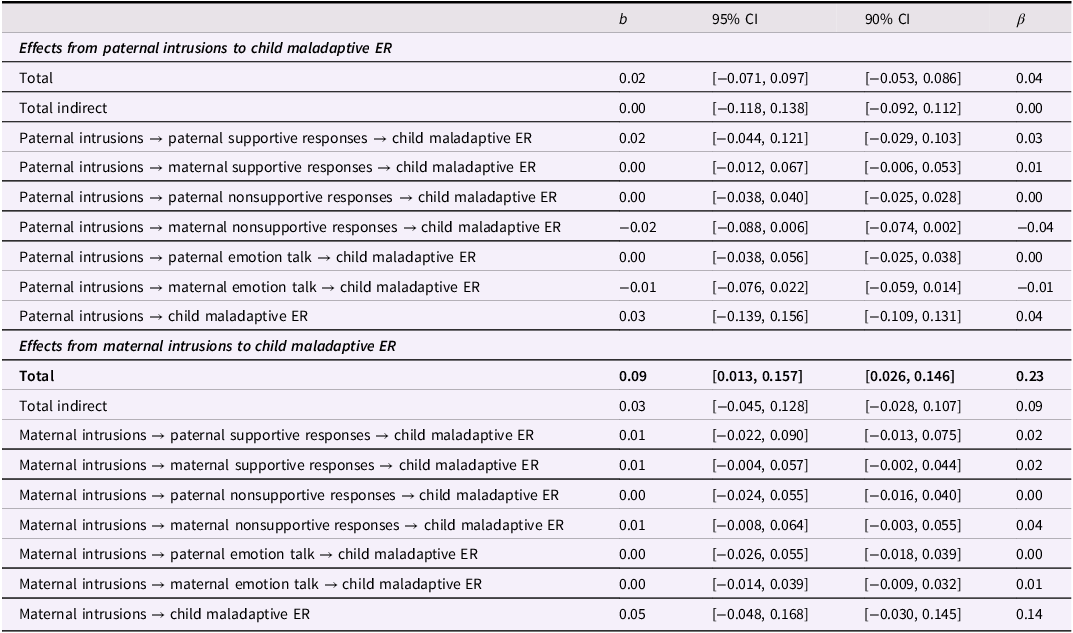

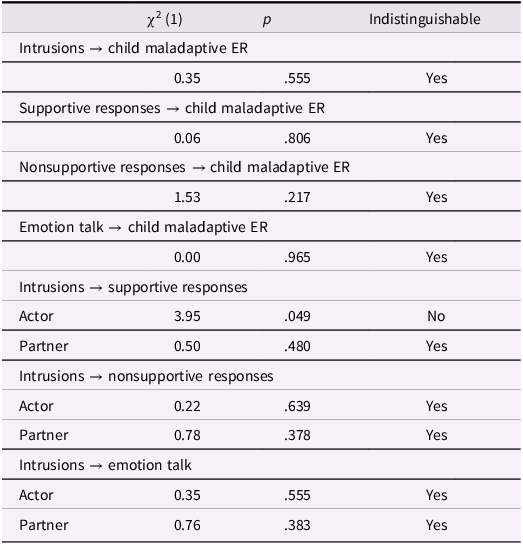

Full model results for intrusions are reported in Table 5 and depicted in Figure 3. Paternal intrusions predicted greater paternal supportive responses (b = 0.29, S.E. = 0.10, p = .005), and maternal nonsupportive responses predicted greater maladaptive ER at child age 5 (b = 0.30, S.E. = 0.14, p = .027). The total effect of maternal intrusions across pregnancy and toddler age on child maladaptive ER (through ERSBs and the unique direct effect) was significant, 95% CI [0.013, 0.157]. No partner effects emerged; that is, one parent’s intrusion symptoms were not significantly associated with the other parent’s ERSBs. Total and indirect effects are reported in Table 6. Tests of indistinguishability suggested that there were no significant differences in the unstandardized estimates for paths between partners (see Table 7).

Table 5. Integrated model results for intrusions

Note. b = unstandardized estimate, β = standardized estimate, ER = emotion regulation, T6 = child age 3. Significant effects based on p < .05 are bolded, and significant effects based on p < .10 are italicized.

Figure 3. Results of Integrated Model for Intrusions. Note. Model results controlling for infant emotion dysregulation, first-time parenthood, low-income status, and whether the preschool-age assessment occurred after the onset of COVID. Significant paths are depicted by solid lines. Exogenous variables were allowed to covary in the model but were not significant. Residuals for endogenous variables were correlated at each time point but are omitted from the figure for ease of presentation.

Table 6. Total, direct, and indirect effects from intrusions to child maladaptive emotion regulation

Note. b = unstandardized estimate, β = standardized estimate, ER = emotion regulation. Significant effects based on the 95% CI (95% CI does not include zero) are bolded.

Table 7. Indistinguishability of specific paths in integrated model for intrusions

Note. ER = emotion regulation. Paths were tested for indistinguishability across mothers and fathers. Actor = within person effect (e.g., maternal intrusions predicting maternal supportive responses). Partner = across partner effect (e.g., maternal intrusions predicting paternal supportive responses).

Sensitivity analyses

To assess the robustness of our findings, we examined whether the significant associations between emotion socialization processes and child maladaptive ER that emerged in our primary analyses varied as a function of parent report. Maternal nonsupportive responses – the only ERSB that significantly predicted maladaptive ER – were significantly associated with both maternal (r = .36) and paternal (r = .26) reports of child maladaptive ER, and the magnitude of these associations did not significantly differ (z = 0.96, p = 0.337). We also tested two alternative models examining whether parental trauma-related distress and ERSBs predicted child adaptive ER. Interestingly, in the integrated model for avoidance, paternal supportive responses predicted greater child adaptive ER at age 5 (b = 0.23, S.E. = 0.06, p < .001) despite a non-significant association between paternal supportive responses and maladaptive ER in the primary models; however, the indirect effect of paternal avoidance on greater child adaptive ER was not significant, 95% CI [−0.022, 0.147]. The same pattern emerged in the intrusions model: paternal supportive responses were significantly associated with greater adaptive ER at child age 5 (b = 0.22, S.E. = 0.07, p = .002). The indirect effect of paternal intrusions on greater child adaptive ER through supportive responses was not significant based on the 95% CI [0.000, 0.170], although the 90% CI did not contain zero [0.010, 0.148].

Discussion

Despite research demonstrating the detrimental impact of PTSS on parenting and child outcomes (Christie et al., Reference Christie, Hamilton-Giachritsis, Alves-Costa, Tomlinson and Halligan2019; Lambert et al., Reference Lambert, Holzer and Hasbun2014), limited work has examined PTSS and emotion socialization, with mixed findings (Giff et al., Reference Giff, Renshaw, Denham, Martin and Gewirtz2024; Gurtovenko & Katz, Reference Gurtovenko and Katz2020). The present study demonstrated that chronic elevations in specific dimensions of maternal trauma-related distress spanning pregnancy to toddler age contributed both directly and indirectly to child maladaptive ER at the transition to formal schooling. However, paternal trauma-related distress and ERSBs were not associated with child maladaptive ER; instead, chronic elevations in paternal trauma-related distress predicted more supportive responses to children’s distress during the preschool years. This study builds on existing cross-sectional research by demonstrating unique longitudinal associations between specific facets of parental trauma-related distress (i.e., avoidance and intrusions) across the perinatal period, subsequent ERSBs, and child maladaptive ER.

Consistent with study hypotheses, elevations in maternal trauma-related distress contributed both directly and indirectly to child maladaptive ER. Chronic elevations in maternal intrusions spanning pregnancy to 2-years postpartum contributed to greater child maladaptive ER at the transition to formal schooling when controlling for infant emotion dysregulation, first-time parenthood, and low-income status. Whereas maternal intrusions had a unique direct effect on child maladaptive ER, maternal avoidance contributed indirectly to child maladaptive ER through more nonsupportive responses to children’s negative emotions during the preschool years, suggesting that maternal nonsupportive responses uniquely undermine child ER at the transition to formal schooling. Although the 95% CI of the overall indirect effect included zero, each component path was significant, underscoring maternal nonsupportive responses as a potential pathway through which maternal avoidance ultimately contributes to greater child maladaptive ER. Overall, this finding aligns with existing work demonstrating robust associations between parental emotion dysregulation and nonsupportive responses (Edler & Valentino, Reference Edler and Valentino2024) and expands on cross-sectional research suggesting that nonsupportive responses mediate the association between maternal and child emotion dysregulation (Morelen et al., Reference Morelen, Shaffer and Suveg2016).

Taken together, results extend both the tripartite model of ER (Morris et al., Reference Morris, Silk, Steinberg, Myers and Robinson2007) and the perinatal interactional model (Lang & Gartstein, Reference Lang and Gartstein2018). Specifically, findings suggest that mothers with chronic elevations in trauma-related distress may contribute to greater child maladaptive ER by not only modeling more intense negative emotionality and more maladaptive regulatory strategies, but also responding more nonsupportively to their children’s negative emotions. Consistent with the meta-emotion framework, mothers with chronic elevations in avoidance may experience their children’s negative emotions as particularly upsetting and react in a nonsupportive manner (e.g., by punishing their child or minimizing the problem) as a means of avoiding or distancing themselves from their children’s distress. However, chronic avoidance seems to uniquely affect nonsupportive responses without undermining other ERSBs. In contrast, the effect of maternal intrusions on child maladaptive ER did not unfold through ERSBs. Thus, in addition to modeling processes, it may be that maternal intrusion symptoms across pregnancy and toddler age contribute to child maladaptive ER through biological mechanisms (e.g., genetics, prenatal programming of fetal development), early caregiving pathways outside of emotion socialization (e.g., mother-infant bonding), or a combination of these processes (Bush, Reference Bush2024; Leen-Feldner et al., Reference Leen-Feldner, Feldner, Knapp, Bunaciu, Blumenthal and Amstadter2013). This finding could also reflect a shared biological vulnerability for emotion dysregulation among mothers and their children that may be reinforced through observational learning processes (Thompson, Reference Thompson2019).

Whereas maternal trauma-related distress contributed to child maladaptive ER at the transition to formal schooling, findings suggest that paternal trauma-related distress and ERSBs did not exert such effects. Though somewhat unexpected, this finding aligns with research suggesting that certain aspects of caregiving continue to fall disproportionately on mothers (Hodkinson & Brooks, Reference Hodkinson and Brooks2020) despite fathers playing an important role in caregiving and child development (Cabrera et al., Reference Cabrera, Volling and Barr2018). Indeed, recent qualitative work with primary or equal caregiver fathers suggests that, in dual-parent mixed-sex households, mothers still play a central role in emotional aspects of caregiving, including responding to children’s distress (Hodkinson & Brooks, Reference Hodkinson and Brooks2020). Thus, for children who rely predominantly on their mothers for comfort and support when they experience negative emotions, maternal nonsupportive responses may uniquely contribute to maladaptive ER. Relatedly, given that mothers (both in the present study and in the literature more broadly) tend to engage in nonsupportive responses less than fathers, maternal nonsupportive response may be particularly important for child ER. Another possibility is that paternal ERSBs contribute to the overall emotional climate of the family rather than directly impacting child maladaptive ER (Kiel & Kalomiris, Reference Kiel and Kalomiris2015). However, tests of indistinguishability suggested that, on the whole, there were no significant differences between maternal and paternal paths, so caution should be taken when drawing conclusions about the differential impacts of maternal and paternal trauma-related distress on ERSBs and child outcomes. Future work should explore the associations between parental trauma-related distress, ERSBs and child maladaptive ER in a larger sample of dual-parent, mixed-sex households, as statistically significant differences may emerge in studies designed to detect sex differences.

Although paternal trauma-related distress was unrelated to nonsupportive responses and emotion talk, chronic elevations in these symptoms predicted more supportive responses to children’s negative emotions, which could have longer-term implications for child adjustment. In fact, sensitivity analyses revealed that paternal supportive responses predicted greater child adaptive ER at the transition to formal schooling. There are several potential explanations for this unexpected finding. First, paternal trauma-related distress may not be maladaptive at subclinical levels, particularly in a community sample not selected for trauma exposure. For instance, fathers experiencing chronic, subclinical elevations in intrusion symptoms may be confronted with their own negative emotions more regularly – but not to an overwhelming extent – which could foster greater awareness of their children’s distress and allow them to respond more supportively. Second, consistent with the meta-emotion philosophy, fathers with chronic elevations in trauma-related distress who engage in avoidance to manage intrusions and associated negative emotions may perceive their children’s distress as overwhelming and engage in more supportive responses in an attempt to reduce their children’s distress (Pereira et al., Reference Pereira, Barros, Roberto and Marques2017). However, because this finding was unexpected, future research is needed before making more definitive conclusions.

Limitations and future directions

Results of the present study should be considered alongside several limitations. First, study aims were pursued in a community sample of mothers and fathers who, on average, reported relatively low levels of trauma-related distress; therefore, results may not generalize to samples experiencing higher levels of trauma-related distress. Given that exposure to certain types of traumatic events (e.g., childhood sexual or physical abuse; interpersonal vs. non-interpersonal trauma; reproductive and childbirth-related trauma) may differentially impact not only trauma-related distress across pregnancy and early childhood, but also parental ERSBs, studies examining these processes among clinical samples are warranted. Second, the sample consisted of mixed-sex couples, and participants largely identified as White and non-Hispanic/Latino, thereby limiting the generalizability of our results. Future research pursuing study aims in a more racially and ethnically diverse sample is critical given the well-documented racial and ethnic disparities in trauma exposure and PTSD (Asnaani & Hall-Clark, Reference Asnaani and Hall-Clark2017; Seng et al., Reference Seng, Kohn-Wood, McPherson and Sperlich2011). Indeed, this work is key considering the vast disparities in obstetric complications and maternal morbidity and mortality between pregnant women of color and non-Hispanic/Latina White women (Bornstein et al., Reference Bornstein, Eliner, Chervenak and Grünebaum2020; Holdt Somer et al., Reference Holdt Somer, Sinkey and Bryant2017), which have the potential to contribute to or exacerbate trauma-related distress (Wang et al., Reference Wang, Glazer, Sofaer, Balbierz and Howell2021) and impact subsequent parenting and child outcomes (Fuchs et al., Reference Fuchs, Resch, Kaess and Moehler2022).

Although the present study focused on the impact of parental trauma-related distress on emotion socialization and child maladaptive ER, other factors may account for the intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation. For instance, parents’ emotions in the context of caregiving may be the most proximal predictors of ERSBs (Hajal & Paley, Reference Hajal and Paley2020); thus, trauma-related distress may indirectly contribute to ERSBs by undermining parents’ abilities to regulate their emotions when confronted with child distress. Parental ERSBs and child ER may also be impacted by contextual factors (e.g., parent and child characteristics, cultural factors) that were not accounted for in the present study. Indeed, given that most research has focused on White, middle-class parents, future research should explore how race and ethnicity influence emotion socialization and subsequent child outcomes. In addition to differing cultural norms for emotion expression and regulation, parents with minoritized racial or ethnic identities have endured and continue to face oppression (e.g., racism, discrimination), which may shape their ERSBs (Labella, Reference Labella2018). For instance, African American parents may be more likely to respond nonsupportively to their children’s negative emotions because publicly expressing such emotions can carry negative – and potentially dangerous – social consequences (Nelson et al., Reference Nelson, Leerkes, O’Brien, Calkins and Marcovitch2012). However, these nonsupportive responses may be adaptive, rather than maladaptive, for children with minoritized racial or ethnic identities, underscoring need for future research examining the associations between parental trauma-related distress, ERSBs, and child ER in larger, more diverse samples.

It was also notable that parental supportive responses and emotion talk were not associated with lower levels of child maladaptive ER in the present study. One possibility is that supportive responses mitigate the intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation by moderating, rather than mediating, the association between parental trauma-related distress and child maladaptive ER (Lee et al., Reference Lee, O’Brien, Binion, Lewis and Zalewski2022). Alternatively stated, supportive responses to children’s negative emotions may only reduce risk for child maladaptive ER when parental trauma-related distress is high. Another possibility is that supportive responses reduce risk for child maladaptive ER among children with more secure early attachment relationships, who may be more receptive to parental support (Boldt et al., Reference Boldt, Goffin and Kochanska2020; Kochanska et al., Reference Kochanska, Boldt and Goffin2019). Importantly, although this study focused on early pathways of risk for child maladaptive ER, it may be that parental supportive responses contribute to more adaptive ER without reducing risk for maladaptive ER, as suggested by our sensitivity analyses demonstrating that paternal supportive responses were, in fact, associated with greater adaptive ER in the present sample.

Similarly, emotion talk may not directly impact child maladaptive ER; rather, it may foster other aspects of emotional competence, such as emotion understanding and knowledge (Denham et al., Reference Denham, Bassett and Wyatt2007), and contribute to child ER without shaping specific maladaptive ER strategies. Further, it may be that the function of emotion talk, rather than the mere frequency, uniquely contributes to child ER. For instance, parents commenting on emotions without explaining their causes and consequences may hinder the development of children’s emotion knowledge and, in turn, confer risk for maladaptive ER. Indeed, research has found that more emotional attributions during mother–child reminiscing about past emotional events were associated with greater child internalizing symptoms, whereas the degree to which mothers provided sensitive guidance was associated with higher language abilities and lower internalizing and externalizing symptoms among children (McDonnell et al., Reference McDonnell, Lawson, Speidel, Fondren and Valentino2022). Thus, future studies exploring these possibilities are warranted.

Finally, parents’ typical responses to their children’s negative emotions do not always fit neatly into categories of “supportive” or “nonsupportive” (McKee et al., Reference McKee, DiMarzio, Parent, Dale, Acosta and O’Leary2022). Indeed, as demonstrated by the present study, although mothers with chronic elevations in avoidance symptoms engaged in more nonsupportive responses, they did not necessarily engage in less supportive responses or emotion talk. One possibility is that parental trauma-related distress may influence person-level patterns of ERSBs, which subsequently impact child ER. Further, within dual-parent households, parental trauma-related distress may impact shared patterns or profiles of emotion socialization strategies used by both parents, which, in turn, contribute to child outcomes. Given the potential for a complex combination of ERSBs, employed by both parents as part of a broader family system, to contribute to child ER (Miller-Slough et al., Reference Miller-Slough, Dunsmore, Zeman, Sanders and Poon2018), future research employing family-centered approaches may be particularly informative for clarifying the associations between patterns of ERSBs and child outcomes.

Clinical implications

The present study has several implications for clinical practice. Results underscore the importance of screening for parental trauma-related distress across pregnancy and early childhood, which has downstream consequences for ERSBs and child maladaptive ER. Current screening recommendations for pregnancy and the postpartum period primarily target maternal depression and anxiety (American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists, 2023); however, fathers are often overlooked (Dhillon et al., Reference Dhillon, Sasidharan, Dhillon and Babitha2022), and screening for PTSD remains uncommon (Padin et al., Reference Padin, Stevens, Che, Erondu, Perera and Shalowitz2022). Because the perinatal transition is a critical window for promoting both parent and child mental health (Davis & Narayan, Reference Davis and Narayan2020), comprehensive screening efforts that explicitly assess for trauma-related distress could curb the intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation by enabling timelier referrals and opportunities for intervention prior to childbirth. Findings also support interdisciplinary screening approaches (i.e., incorporating providers across obstetrics and gynecology, pediatrics, and psychiatry; Cox et al., Reference Cox, Sowa, Meltzer-Brody and Gaynes2016) to support extended screening efforts up to 2-years postpartum.

Given that parents regularly engage with the healthcare system and may be more motivated to change during the perinatal period, prevention and intervention efforts targeting parental trauma-related distress and associated emotion dysregulation across the pregnancy–postpartum transition are vital. Fortunately, research demonstrates the efficacy of several attachment-based interventions that can be delivered in early childhood to promote both parental ER and parenting (see Hajal & Paley, Reference Hajal and Paley2020 for a review). Recent work also points towards the utility of prevention efforts fostering parental self-regulation and adaptive parenting prior to childbirth (Mihelic et al., Reference Mihelic, Morawska and Filus2018). For parents with clinically elevated trauma-related distress, Written Exposure Therapy (WET; Sloan & Marx, Reference Sloan and Marx2019), a 5-session treatment, may be a particularly promising evidence-based approach given emerging research that WET may be effective in treating maternal PTSD during pregnancy (Nillni et al., Reference Nillni, Baul, Paul, Godfrey, Sloan and Valentine2023) and can be implemented in obstetric care (Valentine et al., Reference Valentine, Godfrey, Gellatly, Paul, Clark, Giovannini, Saia and Nillni2023). Results also highlight the utility of interventions that directly target parental nonsupportive responses to children’s distress. Thus, existing evidence-based emotion socialization parenting interventions, which have demonstrated efficacy in improving parental emotion socialization and ER in young children (i.e., 0 to 6 years of age; England-Mason et al., Reference England-Mason, Andrews, Atkinson and Gonzalez2023), may be crucial for preventing the intergenerational transmission of emotion dysregulation.

Conclusion

Despite evidence that PTSS impacts parenting and child outcomes, extant research has largely overlooked the potential for PTSS to undermine parental emotion socialization and contribute to child maladaptive ER. The present study examined whether chronic elevations in trauma-related distress (i.e., avoidance and intrusions) spanning pregnancy to toddler age and ERSBs during the preschool years contributed to child maladaptive ER at the transition to formal schooling, a unique period of heightened academic and socioemotional risk (Rimm-Kaufman et al., Reference Rimm-Kaufman, Curby, Grimm, Nathanson and Brock2009; Rimm-Kaufman & Pianta, Reference Rimm-Kaufman and Pianta2000). Findings revealed that chronic elevations in maternal trauma-related distress contributed directly and indirectly to child maladaptive ER, whereas paternal trauma-related distress did not. Taken together, results underscore the importance of screening for trauma-related distress across the perinatal period and up to 2-years postpartum, as well as prevention and intervention efforts that reduce parental trauma-related distress, strengthen parental ER, and enhance adaptive emotion socialization, thereby mitigating risk for child maladaptive ER and promoting adaptive socioemotional development.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S095457942510103X.

Data availability statement

This study complied with Transparency and Openness Promotion (TOP) Guidelines. Raw data and code necessary to reproduce the analyses presented here are not publicly accessible, though data is presented in aggregate form (i.e., correlation matrices). The study PI, Rebecca L. Brock (rebecca.brock@unl.edu), should be contacted to request access to research materials, analysis code, and data to support meta-analyses and replication studies.

Acknowledgements

We thank the families who participated in this research and the entire team of research assistants who contributed to the study. In particular, we thank Michelle Ebrahim and Maddy Smethurst for the many hours they spent transcribing and coding parent–child interactions for this project; Rachel Beck, Jennifer Blake, Kailee Groshans, and Erin Ramsdell for project coordination; and Allison Sparpana for her help preparing figures and checking tables. We also thank Dr Susanne Denham for her consultation on the coding system used for this project and Dr Patty Kuo for her valuable feedback.

Funding statement

This research was funded by several internal funding mechanisms awarded to PI Rebecca Brock from the UNL Department of Psychology, the Nebraska Tobacco Settlement Biomedical Research Development Fund, and the UNL Office of Research and Economic Development. This research was also supported by the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health & Human Development (F31HD107948), the National Institute of General Medical Sciences (1U54GM115458), and the National Institute of Mental Health (T32MH018269) of the National Institutes of Health. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Pre-registration statement

Data management and analysis procedures for this project were preregistered at https://osf.io/hprk8, and we made no deviations from that plan. Because we had prior knowledge of data from this longitudinal study, we did not preregister our hypotheses, nor did we preregister the specific analyses for the present study. Some of the data included in the present study have been published elsewhere (e.g., Laifer et al., Reference Laifer, DiLillo and Brock2023a; Laifer et al., Reference Laifer, DiLillo and Brock2023b); however, this is the first article to examine how parental trauma-related distress spanning pregnancy and early childhood impacts subsequent child outcomes.

Active link: https://osf.io/hprk8

Date stamped: August 13, 2022

AI statement

AI was not used in the preparation of this manuscript.