In 1906, naturalist author Shimazaki Tōson published his first novel, The Broken Commandment (Hakai). The story explored the predicament of Segawa Ushimatsu, a schoolteacher in Japan coming from an outcast (burakumin) background. Segawa was struggling between the necessity to hide his burakumin identity in order to live a normal life and his desire to challenge the social prejudices faced by the outcast community. He eventually announced his burakumin identity in public, only to realize that there was no end in sight for his struggles against discrimination. By pure chance, an exhausted Segawa learned about an opportunity for him to migrate to Texas to embark upon a career in agriculture. The novel ended with Segawa departing for Texas in an attempt to escape from his hopeless struggles in Japan once and for all.

Segawa’s decision to migrate across the Pacific testified to the image of the United States as the proverbial land of opportunity in the discourse of overseas migration in Japan at the time.Footnote 1 The United States as a country was indeed seen as a land of egalitarianism that provided boundless opportunities by ambitious but underprivileged Japanese men. However, it was telling that Shimazaki, the author of the novel, specifically chose Texas to be the protagonist’s promised land of racial equality. This setup revealed that contemporary Japanese writers and observers were well aware of the existence of anti-Japanese racism on the American West Coast.Footnote 2 Thus it was Texas, not the states on the West Coast, that was portrayed as a utopia with no prejudice.

Equally significant was the fact that Segawa ultimately decided to pursue a career in farming. This move away from industrial labor toward agriculture mirrored the beginning of a significant transformation of Japan’s migration-based expansionist discourse. While the United States remained the most attractive migration destination in the minds of the heimin expansionists, they were losing interest in labor migration. They believed that because Japanese migrant laborers had no intention to stay for long or to contribute to the local society, their migration could only incite anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. Instead, they assumed, common but ambitious Japanese men could find their footing in America through farming, and such a long-term career would demonstrate to white men that these Meiji subjects were indeed the salt of the earth.

The promotion of agricultural migration to Texas was not only a response to anti-Japanese campaigns on the American West Coast but also a result of the growing tension between the agricultural sector and the industry-centered model of development of the Meiji empire at the turn of the twentieth century. Alarmed by Japan’s loss of self-sufficiency in rice supply and increasing concentration of farmland, agrarian thinkers argued that it was important to protect agriculture as the foundation of the Japanese economy and the owner-farmers as the backbone of the nation. Identifying the issue of overpopulation as the main cause for the crises in the Japanese countryside, agrarian expansionists proposed for common farmers to migrate overseas; they believed such a move would both stimulate Japanese agricultural productivity at home and plant the root of expansion for the empire abroad.

This chapter examines the origin, development, and demise of the short-lived campaign of Japanese farmer migration to Texas in the 1900s. Similar to the movement of labor migration to the United States that took place around the same time, the call for agricultural migration to Texas was also grounded in the discourse of personal success, inviting the common Japanese to become self-made men through migration. Though it was a part of the heimin migration wave, the Texas campaign marked the beginning of a paradigm shift in Japanese migration-driven expansion from labor to agriculture. Subsequently, the failure of this project prompted Japanese expansionists to cast their gaze farther south, paving the way for Japanese farmer migration into South America in the decades to come.

The Debate on the Role of Agriculture

Both laborers and farmers were key components of heimin, the class of commoners with no inherited privilege in Meiji Japan. The growth of their presence in the public discourse heralded the decline of shizoku’s political influence. In the eyes of heimin activists, there was a substantial overlap between the categories of farmers and laborers, as migrants from the countryside constituted the main body of the burgeoning working class in the cities. The majority of migrants who made their way overseas by following the teaching of heimin expansionists like Tokutomi Sōhō, Katayama Sen, and Shimanuki Hyōdayū were young men who had grown up in the countryside.

However, the respective rise of laborers and farmers as political forces revealed different social changes within the Japanese society. The calls for labor migration reflected the growth of the Japanese urban working class at the end of the nineteenth century. The emergence of farmers in the discourse of Japanese expansionism, on the other hand, was a result of agriculture’s shrinking importance in an increasingly industrialized empire.

In the minds of Meiji empire builders, the agriculture sector was an essential contributor to Japan’s quest of modernization but not a direct beneficiary. The passage of the Land Tax Reform Law of 1873 legalized land ownership, allowing lands to be freely bought and sold. The government’s land survey that came with the law registered a substantial amount of new land to be taxed, and the government’s land tax income increased by 48 percent.Footnote 3 For most of the Meiji period, the agricultural sector remained the biggest source of the state’s income, which in turn was used to finance industrial development. The privatization and marketization of land resulted in a concentration of landownership. The Matsukata Deflation in 1881 accelerated this process by causing a sharp drop in the prices of rice and silk. As a result, between 1884 and 1886, 70 to 80 percent of farming households in the Japanese countryside were in debt.Footnote 4 Many owner-farmers had no choice but to sell their land in order to pay off debts. After losing their land, they either stayed in the countryside as tenant farmers or migrated to urban areas to seek employment as wage laborers. Japan in the last two decades of the nineteenth century thus experienced both a rapid shrinkage of the owner-farmer population and an increase in landlord-tenant disputes.

The outbreak of the Sino-Japanese War dealt yet another blow to Japanese agriculture. The war boosted industrial development and lured even more people away from the countryside. The growing urban population and the rising standard of living turned Japan from a rice exporter into a rice importer. From the late 1890s, rice from Taiwan and later the Korean Peninsula began to flow into the Japanese market.Footnote 5 Shrinkage of the owner-farmer population and growing insufficiency in rice production received immediate attention from Japanese thinkers. Figures from both inside and outside of the policymaking circle warned the nation about the importance of farming and sought to improve the position of agriculture in the national economy.

Two schools of thought emerged at this moment. Both of them emphasized the centrality of agriculture, but each had a different blueprint for Japan’s national destiny in relation to the West. One school of thought was represented by Yokoi Tokiyoshi, a professor of agronomy at Tokyo Imperial University. In an 1897 essay titled “Agricultural Centralism” (“Nōhonshugi”), Yokoi launched a radical attack on the early Meiji principle of national development centering on industrialization and Westernization. The Western model of development was destined to fail, he argued, because its one-sided industrial development would inevitably widen the social gap. With increasingly flagrant disparity between the different segments of society, Western societies would eventually head down a path of revolution and chaos. Due to its blind imitation of the Western model, Yokoi believed, Japan’s industrialization was also being built on the sacrifice of the agricultural population. Attached to the soil, farmers were naturally the most patriotic subjects and most qualified soldiers of the empire. Yet as urbanization drained both human and material resources from the countryside, these farmers were losing their land and becoming mired in poverty. To avert potential chaos, Yokoi argued, the government should make the development of agriculture – instead of industry – its top priority.Footnote 6

The other school of thought was represented by Nitobe Inazō, the founder of the School of Japanese Colonial Policy Studies. In 1898, a year after Yokoi published his essay, Nitobe authored On the Foundation of Agriculture (Nōgyō Honron).Footnote 7 This book-length study was not as widely known as some of his other works, but it profoundly influenced the evolutionary course of Japanese colonialism and expansionism in the following decades. The book, like Yokoi’s essay, emphasized agriculture’s role as the very foundation of the empire. While sharing some of Yokoi’s criticisms about the government’s neglect of domestic agriculture, Nitobe firmly believed that Japan was destined to follow the path of the West and become an industrialized empire. Unlike Yokoi, Nitobe drew the conclusion that agriculture was not to replace industry as the top policy priority. Instead, Nitobe called for more attention to the development of agriculture in order to secure Japan’s progress in industrialization.

Nitobe criticized the Western European powers such as the United Kingdom and France for achieving rapid industrialization at the price of sacrificing their agricultural sectors. As a result, he argued, the European empires eventually lost their agricultural self-sufficiency; they had no choice but to meet their domestic need for agricultural products through importation from their overseas colonies. Nitobe urged Japan to avoid falling into the same trap, as agriculture was the empire’s very foundation on which all other achievements – such as cultural progress, urbanization, and the improvement of public health – could be built. It was thus imperative for the Empire of Japan to maintain its agricultural self-sufficiency.

Nitobe’s interest in agriculture, stemming from his study at Sapporo Agricultural College in Hokkaido and his personal connection with Tsuda Sen’s Association of Studying Agriculture (Gakunō Sha), was infused with both Malthusian expansionism and colonial ambition. He believed that rapid population growth was essential for Japan’s development as a civilized and expanding empire, and a flourishing agricultural sector was the key to keeping the population growing because it guaranteed sufficient food supply.Footnote 8 The protagonists in Nitobe’s blueprint for Japanese empire building were no longer the shizoku of yesterday or the bourgeoning urban working class, but the owner-farmers (jisakunō) from the countryside. Working in the field on a daily basis, Nitobe argued, the owner-farmers were healthier and physically stronger than the urban dwellers and would make better soldiers for the empire. Moreover, they also enjoyed a higher fertility rate and longer life expectancy than the urban residents.Footnote 9 As both the primary food supplier for the nation and the biggest source of manpower for the imperial army, they should be protected from falling into poverty and performing excessive labor.Footnote 10

Nitobe’s agenda was better received than Yokoi’s because most national leaders both within and outside of the government still saw Western-style industrial imperialism as the example to emulate for Japan. Within ten years after its original publication, On the Foundation of Agriculture was reprinted five times. Nitobe’s idea of emphasizing the fundamental role of agriculture in Japan’s development into an industrial empire also won him many supporters and converts among the thinkers and doers of Japanese expansion. On Japanese Agricultural Centralism (Nihon Nōhon Ron), authored by agronomist Hiraoka Hikotarō four years after the publication of Nitobe’s book, for example, wholeheartedly accepted Nitobe’s notion of agriculture as the foundation of Japan’s national progress. It further offered several ways to reverse the agricultural sector’s decline, including lowering the land tax, imposing protective tariff on imported agricultural products, as well as modernizing farming management techniques and equipment.Footnote 11 More importantly, Hiraoka also proposed the migration of Japanese farmers overseas. The migration and resettlement of a certain amount of rural population overseas, he argued, would speed up Japan’s agricultural mechanization process and increase agricultural productivity. The growth of overseas Japanese communities would also increase the export of Japanese agricultural products abroad.Footnote 12 As a leading thinker and professor of colonial studies, Nitobe also trained and influenced a group of colonial thinkers. Among his protégés were Tōgō Minoru and Ōkawadaira Takamitsu, whose works demonstrated the impacts of both the Russo-Japanese War and the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States. As the following pages demonstrate, their writings marked the beginning of farmer-centered Japanese expansionism.

Japanese Exclusion in the United States and the Emergence of Farmer Migration

At the turn of the twentieth century, while Japanese intellectuals were trying to grapple with the empire’s agricultural issues, anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States also began to swell. Japanese laborers, who constituted the majority of the overall Japanese immigrant population of the day, became the primary targets of anti-Japanese campaigns in America. These laborers were seen in the same light as the Chinese immigrants who were already excluded; they were labeled as lacking in social manners and education, and they were accused of being reluctant to contribute to the local community due to a lack of commitment to the new life.

Anti-Japanese sentiment on the American West Coast grew even stronger after Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War, when the exclusionists began to link the threat of the racially inferior Japanese immigrants to the American labor market with the threat that the Empire of Japan potentially posed to American national security. Japanese mass media paid close attention to the anti-Japanese campaigns on the American West Coast and expressed indignation toward the United States after the agreement was sealed. In June 1907, a popular journal of satire cartoons named Tokyo Puck published a special issue titled “The Issue of Anger toward the United States” (“Taibei Haffun Gō”), criticizing Americans’ hypocrisy by juxtaposing their self-professed principles of humanism, justice, and freedom with the reality of American immigration restrictions, racism, and corrupted politics. Novels imagining a war between Japan and the United States, ending with total victory for Japan, also began to appear in 1907,Footnote 13 allowing the Japanese public to take a measure of fictional revenge against the hypocritical Americans.

While anger and vengefulness were the mass media’s general response to American anti-Japanese sentiment, Japanese intellectuals, particularly those who were trained in Western colonial theories, sought to reconcile Japanese exclusion in the United States with the image of the United States as a righteous leader of the West that Japan sought to follow. They faithfully accepted the logic of the white exclusionists and saw temporary labor migration as an undesirable model of Japanese expansion in the United States. The rise of agricultural centralism and growing landlord-tenant disputes in Japan naturally drew their attention to agricultural migration as an alternative.

Malthusian expansionism provided an easy solution to Japanese thinkers who lamented the agricultural sector’s decline while maintaining the necessity for industrial and commercial primacy. They attributed the fundamental cause of rural depression to overpopulation in the Japanese countryside, which in turn had led to an overall decline in agricultural productivity. The fact that Japan lost its main staple food self-sufficiency was seen as damning evidence of this overpopulation crisis.Footnote 14 Based on this assumption, they argued that the Japanese agricultural sector could be revived by relocating the surplus rural population overseas with no major changes to the existing economic structure of the country.

Two studies on colonialism that appeared right after the Russo-Japanese War marked the beginning of this shift in intellectual thought.Footnote 15 Both Nihon Imin Ron (On Japanese Emigration) and Nihon Shokumin Ron (On Japanese Colonial Migration) were written under the auspices of Nitobe Inazō. Authored respectively by Ōkawadaira Takamitsu in 1905 and Tōgō Minoru in 1906, these works were among the earliest original studies of colonialism by Japanese scholars, who previously had relied heavily on the existing colonial studies done by Western scholars. Produced during the formative years of the colonial policy studies in Japan (Shokumin Seisaku Kenkyū), these two works laid the foundation for the discourse of expansionism both in and beyond Japanese academic circles in the decades to come.

For both Ōkawadaira and Tōgō, the anti-Japanese campaigns in the United States served as lessons for Japan’s further expansion. They believed that in order to avoid being excluded again in the future, Japanese emigrants should do away with their sojourning mentality (dekasegi konsei) and aim to settle abroad permanently. Under the sojourning mentality, the previous Japanese migrants to the United States planned to stay overseas only temporarily; after they saved a certain amount of wealth, they would return home. As a result, the authors asserted, they were unwilling to assimilate into American culture or make any contribution to their host country. Their self-isolation from the mainstream society became a major cause of anti-Japanese sentiment. The solution to this problem, Ōkawadaira and Tōgō argued, was for Japanese emigrants to prepare to resettle their lives abroad permanently; they should consider the host country their home and actively contribute to its development. Only in this way could they be accepted as equal members in the host country and secure new citizenship, thereby gaining voting rights and the ability to forestall any anti-Japanese policy in the future. Taking it a step further, they would also be able to make long-term contributions to Japan by swaying the politics of the host country and facilitating bilateral trade relations between the two states.Footnote 16

Aside from dictating the appropriate mind-set for migrant overseas settlement, Ōkawadaira and Tōgō also contended that the model of Japan’s migration-based expansion should be agrarian. Unlike other types of expansion that could achieve only temporary results, agriculture-centered expansion, they believed, would bring permanent benefits to the empire. Tōgō quoted the words of German historian Theodor Momsen in the beginning of his book: “That which is gained by war may be wrested from the grasp by war again, but it is not so with conquests made by the plough.”Footnote 17

The ideal candidates for migration were farmers in the countryside who were victims of continuous rural depression.Footnote 18 The deterioration of the farmers’ quality of life was accompanied by Japan’s loss of self-sufficiency in rice supply beginning at the end of the nineteenth century, leading to increasing concerns among Japanese policymakers and intellectuals about food shortages. It was in this context that Malthusian expansionism, an ideology that had already for decades served as the logical foundation for Japanese expansion, was offered up as the easiest explanation: rural depression and food shortage were the natural result of overpopulation in the Japanese countryside, and the only remedy was for the empire to expand further by relocating the surplus farmers abroad. Useless in Japan, they would acquire more land outside of the archipelago and work them to the empire’s benefit.Footnote 19

Tōgō shared classic Malthusianism’s belief that a given size of earth had a certain limit on the food it could produce. If the population size exceeded what the earth could support, the earth would begin to lose its fertility, leading to economic crisis and subsequently moral crisis. At the same time, like most intellectuals of his day, Tōgō maintained that population growth was absolutely necessary because it was a critical indicator of national strength. Japan’s high fertility rate proved the nation’s racial superiority, making them comparable to the Caucasians.Footnote 20 He believed that there was an intrinsic relationship between the increase of food production and that of population.Footnote 21 In order to sustain the current speed of demographic increase, Tōgō argued, Japan had to increase its agricultural productivity. At the same time, the current low productivity in agriculture was due to its excessive farming population: there were too many farmers and not enough arable land. Relocating these surplus peasants overseas to acquire and farm new lands would not only increase the efficiency of agriculture at home but also provide more food supplies from abroad.Footnote 22

Tōgō further categorized expansion into two types: nonproductive and productive. Unlike nonproductive expansions such as military conquest, agricultural migration was a type of productive expansion because it aimed for long-term benefits and permanent settlement. While it could not provide a quick payoff due to the very nature of agriculture, it could steadily develop and consistently yield profits for a long time. Spanish expansion into South America had failed because their nearsighted colonists were satisfied with temporary profits, paying attention only to mining precious minerals; in contrast, the British had successfully expanded into North America due to their long-term investment into land settlement: having voyaged cross the Atlantic Ocean with plows and pruning hooks, they started their new lives by cultivating the land first.Footnote 23 Since agriculture was the foundation for population growth and the development of both industry and commerce, promotion of agricultural migration should be a top priority for the Japanese government in terms of its overseas expansion policies.Footnote 24

Like Tōgō, Ōkawadaira also believed that Japan’s rural depression was a result of overpopulation in the countryside. As there were too many farmers and not enough arable land in Japan, he argued, the rural economy suffered from unhealthy competition among the farmers and an overall decline in agricultural productivity.Footnote 25 The already oversaturated labor market in rural Japan took another blow when more than half a million veterans returned from the battlefields of the Russo-Japanese War. Ōkawadaira agreed with Tōgō in that relocating the “extra” farmers overseas was the best solution to Japan’s rural depression.Footnote 26

Both Tōgō and Ōkawadaira imposed certain standards for prospective migrants, stipulating that the candidates should be carefully selected and trained. For example, tenant farmers who had little land or money were not qualified because the trip itself and land acquisition abroad required a certain amount of capital. Only owner-farmers could meet the financial requirement. Land ownership also correlated with a certain degree of education, therefore the owner-farmers were more politically conscious as imperial subjects; they were more likely to be prepared to present Japan as a civilized empire to the foreigners.

As adherents of Malthusian expansionism, Tōgō and Ōkawadaira maintained that in order for agriculture-based migration to be successful, the migrants’ destinations must have vast amounts of fertile land. Tōgō believed that Hokkaido and Taiwan, the two existing destinations, were no longer fertile enough to house Japan’s rapidly growing peasant population. Though they were not opposed to migration to the United States, Tōgō and Ōkawadaira believed that the empire had to find alternative destinations beyond the reach of the Anglo-Saxons. Tōgō considered the Korean Peninsula and Manchuria, two territories that came under Japan’s sphere of influence after the Russo-Japanese War, as the ideal targets for agricultural expansion.Footnote 27 Ōkawadaira, on the other hand, believed that Asia was already too densely populated, therefore South America was a better choice.Footnote 28

As Tōgō and Ōkawadaira’s plans demonstrated, the Japanese expansionists were operating on a global scale in their searches for settlement locations. Eventually, the state of Texas in the United States became the first test site for the idea of Japanese farmer migration, an experiment that was carried out with cooperation between the imperial government and a number of social groups. The campaign for Texas migration attracted nationwide attention in Japan and paved the way for Japanese agricultural migration to Asia and South America from 1908 onward.

From Laborers to Farmers

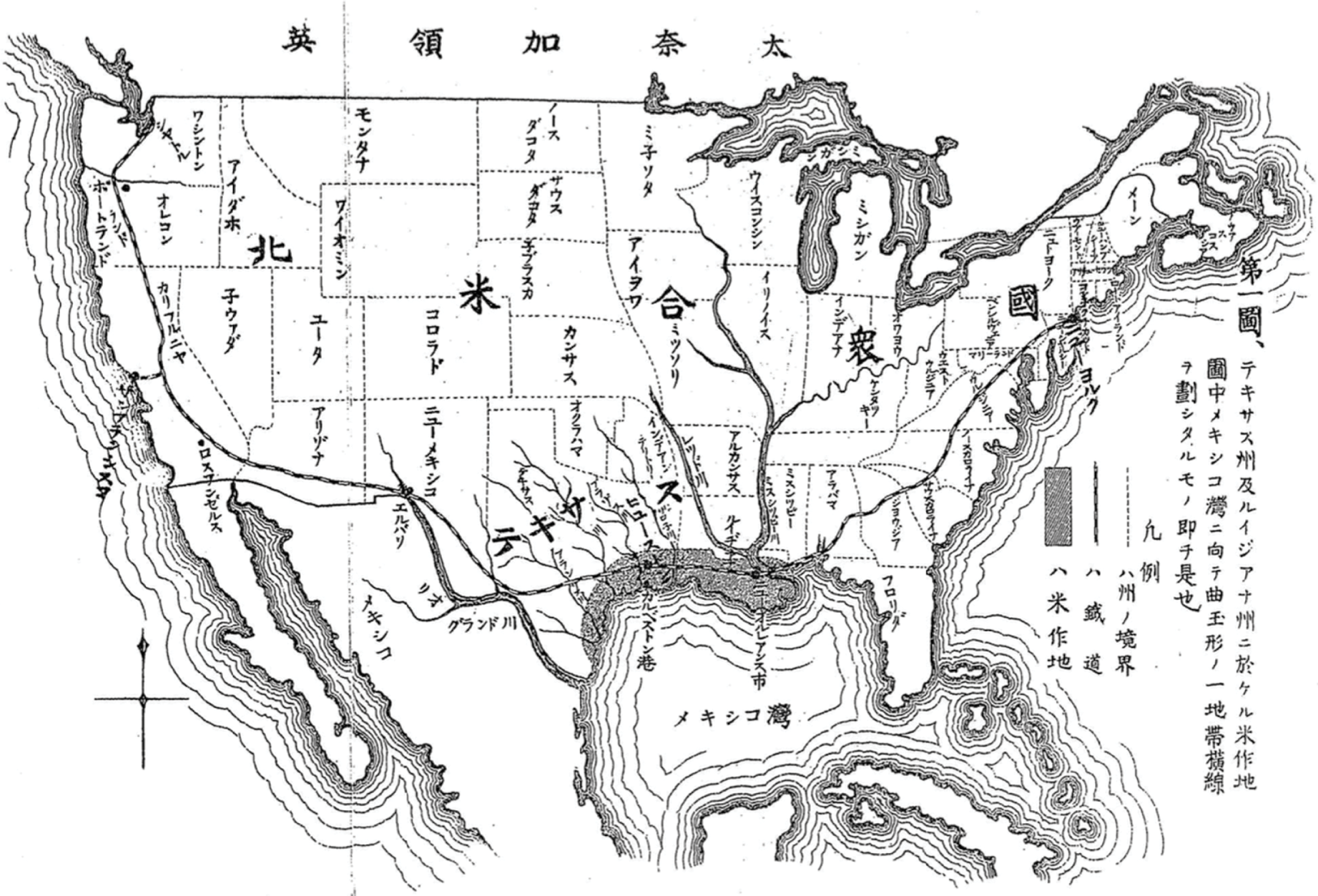

Japanese Texas migration constituted the initial step in the transformation of Japanese migration-driven expansion. Not only did it put the idea of farmer migration into practice, it also paved the way for Japanese farmer migration to Latin America. Texas came under the radar of Japanese expansionists due to the efforts of Japanese diplomats. In response to the anti-Japanese sentiment on the American West Coast, the Japanese Ministry of Foreign Affairs began to tighten its control on emigration in order to avoid further provoking anti-Japanese sentiment in the United States.Footnote 29 At the same time, however, Japanese diplomats were also looking for ways to continue Japanese migration to the United States. In 1902, Uchida Sadatsuchi, the Japanese consul in New York, made a pitch to Tokyo about relocating Japanese farmers to Texas for rice cultivation. Reprinted in mass media, Uchida’s report triggered a boom in Texas migration from Japan that lasted from 1902 to 1908.Footnote 30

As a result of Uchida’s report, the Ministry of Foreign Affairs showed a strong interest in the prospect of Japanese migration to Texas and began to publish relevant reports in its official journals.Footnote 31 The imperial government’s interest in the idea was echoed by public enthusiasm in mass media. By 1908, countless reports and stories of Japanese rice farming (beisaku) in Texas had appeared in different types of journals and newspapers at both national and local levels. Among these media outlets were leading migration journals such as Amerika, Tobei Zasshi, and Shokumin Sekai, mainstream media such as Chūō Kōron and Tōyō Keizai Shinpō, as well as those targeting specific or professional audiences such as Kyōiku Jiron (Education Times) and Nōgyō Sekai (Agricultural World).Footnote 32 Influenced by passionate rhetoric from both the government and mass media, hundreds of Japanese sailed across the Pacific and landed in southern Texas to pursue a career in rice farming.Footnote 33 Among these trans-Pacific rice farmers were some prolific writers who broadcasted their success, in rather exaggerated styles, to their countrymen back in Japan, further fueling the fever for Texas.

One of the most vocal proponents for agricultural migration was Yoshimura Daijirō, a Malthusian expansionist who had been enthusiastically encouraging Japanese youth to achieve personal success by leaving overpopulated Japan for United States to seek work-study opportunities.Footnote 34 He formed the Society of Friends of Overseas Enterprises (Kaigai Kigyō Dōshi Kai) in Osaka in 1903, aiming to assist Japanese farmers for migration to Texas.Footnote 35 Together with other society members, Yoshimura purchased 160 acres of land in League City, Texas, and established a rice farm there in 1904.Footnote 36 Though the farm was bankrupted the same year, this experience allowed Yoshimura to pen three guidebooks on American migration for Japanese readers between 1903 and 1905 that highlighted the promising future for rice farming in Texas. These guidebooks provide a valuable prism for us to analyze this phase of transition for the Japanese expansion discourse in the mid-1900s, when the empire moved away from labor migration and promoted agricultural migration in its stead. They also reveal that Malthusian expansionism continued to serve as the fundamental driving force in this new stage of Japan’s migration-based expansion in the decades to come, with the agricultural sector at its front and center.

Texas as Japanese Frontier: Rice, Race, and History

How did Texas become an ideal target for Japanese agricultural expansion? There are a number of reasons for this phenomenon, all of them embedded in the historical contexts of both countries. First, the Lone Star State was an alternative to the American West Coast, which up to this point had been the most attractive destination for Japanese labor migrants. In response to the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment on the West Coast, migration promoters in Japan began to cast their eyes eastward to inland America. Yoshimura, for example, saw American exclusionism as a natural result of the arrival of a huge number of immigrants “who raided the coastal areas like locusts.” He believed that Japanese immigrants would be welcomed if they moved to inland states such as Colorado, Texas, and Louisiana, places that had not yet received many Asian immigrants. In addition, these inland states’ vast and rich lands were currently occupied by only very few residents.Footnote 37

The attention shift of Japanese expansionists from the West Coast to inland America also matched the rise of the discourse of farmer migration in Japan that began to replace the discourse of labor migration. In his report to Tokyo, Uchida Sadatsuchi described the migration of Japanese farmers to Texas as a better alternative to labor migration to the West Coast. Unlike the unenlightened and low-class laborers who would only provoke the white residents’ wrath, Uchida emphasized, the key to Japanese success in the United States was to export owner-farmers who had both a fair amount of wealth to purchase land and the resolution to settle in the United States permanently.Footnote 38 Texas, situated far away from the centers of anti-Japanese sentiment in the West Coast, looked particularly promising to Japanese expansionists. According to Yoshimura, the state of Texas was roughly twice as big as Japan but was occupied by only a small number of settlers.Footnote 39 Blessed with a pleasant climate, it was a cornucopia waiting for Japanese farmers to explore and develop.Footnote 40

Second, Texas was singled out as the most promising destination for Japanese migrants because it was beginning to take part in American agricultural capitalism’s trans-continental expansion. Even though livestock husbandry remained Texas’s economic engine when it became the twenty-sixth state in 1845, Texas quickly became a primary cotton supplier in the country by the turn of the twentieth century, and it had begun to supply cotton to the fledgling Japanese textile industry by the end of Sino-Japanese War.Footnote 41 After its neighbor Louisiana became the top producer of rice in the United States in 1889 by attracting rice farmers to work the coastal lands along the Gulf of Mexico, the Texan government sought to do the same in the southern part of the state, an area that shared the coastline with Louisiana. The completion of the Southern Pacific Railroad, connecting New Orleans with Los Angeles and running straight through Texas, also expedited agricultural settlement and the transportation of farm products. The Southern Pacific Railroad Company had obtained a large amount of Texan land along the railway lines. Motivated by profit, it spared no effort to attract agricultural settlers to the Lone Star State who would purchase its land for rice farming.Footnote 42 Originally tasked with investigating the conditions for cotton cultivation in the American South, Uchida was approached by leaders of agriculture in Texas. These Americans expressed an interest in attracting Japanese farmers to the state in order to jumpstart its own rice cultivation industry.

The opportunity of rice farming in Texas coincided with the rising calls for “rescuing” agriculture in Japan. For Japanese expansionists, relocating farmers from the overcrowded archipelago to Texas to grow rice was a masterful move that would kill two birds with one stone. The emigration of surplus population would help to balance Japan’s domestic farmer-land ratio and improve its agricultural productivity. Moreover, Japanese success in rice farming in Texas would reaffirm the centrality of agriculture to the Japanese national identity, something that was endangered by Japan’s loss of self-sufficiency in rice.

Yoshimura Daijirō argued that in the preceding decades, the demand for food had grown rapidly in the United States as the country’s population skyrocketed. Out of many types of staple foods, rice was a particularly popular choice in the United States because its advantages had been amply demonstrated by Japanese robustness and productivity. “The courage of Japanese soldiers, the vigor of Japanese rickshaws, and the physical strength of Japanese women,” Yoshimura proudly claimed, were all results of rice eating (beishoku).Footnote 43 He also believed that rice farming in Texas would further prove that the Japanese were the world champion in agriculture. While the demand for rice kept growing, Yoshimura pointed out, the white settlers preferred commerce and industry to agriculture. For this reason, the Japanese would be welcomed in Texas because they were the nature-anointed kings of rice farming.Footnote 44

Third, Texas was seen as the new frontier of Japanese expansion because of its own colonial history. In Yoshimura’s imagination, the past and present of Texas were not only relevant but also closely connected to Japanese expansion at its moment of paradigm change. The history of Texas, he argued, was a tale of colonial competition and racial struggle. The land of Texas had changed hands from the Native Indians to Latin Europe colonists, the Mexicans, and eventually the Anglo-Saxons. The American expansion experience in Texas was particularly instructive to the Japanese because it was a testament to the merits of long-term settler expansion. The old colonial expansion, exemplified by the Spanish Empire, was conducted through military conquest and invasion.Footnote 45 Yet the era of military invasion had ended, announced Yoshimura, and the civilized powers now wrestled through peaceful means as migration became the primary method of expansion in this new era. For Japanese expansionists, Texas’s recent history demonstrated the power of migration and settlement: The American migrants first arrived in this part of Mexico without any support from their national government. Through diligence and perseverance, they were able to entrench themselves in this foreign land and make it their own. Operating under the natural principle of survival of the fittest, they were eventually enthroned as the owners of Texas.Footnote 46 The colonization of Texas, Yoshimura contended, represented the overall model of American settler expansion that the Japanese should emulate. The key to such a successful venture was replacing temporary laborers with farmers who were prepared for long-term settlement in foreign lands.

If the colonial history of Texas offered a lesson for Japanese expansionists, the campaign for Japanese farmer migration to Texas was an indispensable part in their blueprints of the empire’s expansion. It was expected that success in rice farming in Texas would allow the Japanese to claim a primary role in rice production, a field that would be of vital importance to the US economy in the future.Footnote 47 The victory of the Japanese farmers over white settlers in Texas would herald the success of Japanese expansion in the following decades in East Asia, Southeast Asia, and South America, new arenas of global colonial competition in the dawning century.Footnote 48

Based in Osaka, the Society of Friends of Overseas Enterprises was established by Yoshimura and his peers to ensure the success of this new model of Japanese expansion in Texas. Yoshimura believed that like the American settlers who colonized Mexican Texas, the new Japanese migrants should have to resolve to make American Texas into a permanent home of the Japanese. The society’s goal was to provide guidance to these empire builders to make long-term plans of settlement and help them to overcome temporary hardships while abroad.Footnote 49 Not only did the society have plans to build several branches in the United States, it also aimed to branch into Asia.Footnote 50 Even though this organization quickly collapsed, its vision for Japanese empire building demonstrated that under this new direction of agricultural expansion, Japanese migration to the United States was still intrinsically tied to Japanese expansion into the other parts of the Pacific Rim.

The involvement of Katayama Sen, a central leader of Japanese labor migration to the United States, in the movement of rice planting in Texas testified that Japanese migration-based expansion had become irreversibly centered on agriculture. In 1904, after investigating the existing Japanese farms in Texas, Katayama penned four consecutive articles in the Oriental Economist (Tōyō Keizai Shinpō) that passionately promoted agricultural migration to Texas.Footnote 51 At the same time, with the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment on the American West Coast in mind, Katayama offered his readers some words of caution. He pointed out that while Texas was a superior alternative to the West Coast because the Japanese were welcomed there and the procedure for them to purchase land was simple, not every Japanese could succeed. Temporary laborers were not qualified for rice farming in Texas because they did not have the specialized knowledge needed to choose the land, prepare farm facilities, and manage a farm. Farmers with limited means were also unsuitable, as they did not have enough money to purchase lands in Texas. The most desirable migrants for this project were thus those who owned sizeable land themselves in Japan with both the expertise in crops cultivation and the means to secure sufficient startup capital.Footnote 52

Katayama soon put his rhetoric into practice. Between 1905 and 1907, he made several attempts at establishing rice farms in Texas and recruiting farmers from Japan, none of which succeeded. Ironically, his failure stemmed from his own inability to meet the two preconditions that he had laid out in his analysis: he had neither agricultural expertise nor stable financial support. When his long-term donor Iwasaki Kiyoshichi withdrew his money, Katayama had no choice but to end his Texas campaign once and for all.Footnote 53

Subverting Racism through Farming

In order to raise money for their projects, Katayama Sen relied on big donors while Yoshimura Daijirō used collective funding. In contrast, many other Japanese farm owners in Texas were wealthy enough to establish their businesses in Texas with their own money. The most successful and influential Japanese farm in Texas was established and managed by Saibara Seitō and his family.

Saibara Seitō’s life path illustrated the multidimensional connections between Japanese trans-Pacific migration and Japan’s colonial expansion in Asia. An activist in the Freedom and People’s Rights Movement, he was elected as a member of the Imperial Diet in 1898 and became the president of Doshisha University in the next year. A Malthusian expansionist, he began his career as a colonist in 1896 by funding a migrant farm in Hokkaido named the Society of Northern Light (Hokkō Sha).Footnote 54 Disappointed by the domestic political climate and stimulated by the fever of migration to America, Saibara resigned his positions in Japan and moved to the United States for a new start in 1902. Inspired by Uchida’s report on Japanese rice farming in Texas and established his own farm on three hundred acres of land in Webster, Texas, at the end of 1903.

Saibara was well educated in specialized knowledge and in possession of substantial wealth. Though born to a shizoku family, he was an ideal candidate for success in this wave of heimin-centered agricultural migration and indeed became one of the most eminent Japanese settlers in Texas. From 1904 to 1907, his farm almost tripled in size and its output quadrupled. Due to Saibara’s effort in seed refinement and the exploration of alternative crops, his farm was able to enhance its rice productivity and survive several natural disasters as well as unexpected drops in the price of rice, even while some other Japanese farms went bankrupt.Footnote 55

Self-styled as a torchbearer of the Japanese agricultural expansion in the United States, Saibara became a spokesperson for Texas rice farming in Japan. Traveling back and forth between Texas and Japan, he persuaded his family members to join his cause and recruited farmers (mainly from Kōchi, his native prefecture) to work on his farm. He further participated in Texas migration promotion in Japan by advertising his success to the Japanese public: he made public speeches and wrote articles for various domestic journals to share tips with his countrymen who planned to follow his footsteps. Widely reported on and celebrated in migration circles, Saibara became the symbol of Japanese agricultural migration to Texas. His farm became an exhibition site of Japanese nationalism and expansionism that attracted visits from Japanese intellectuals, entrepreneurs, and politicians when they visited the United States for the Louisiana Purchase Exhibition in 1904.Footnote 56 Students in Japanese agricultural colleges saw Saibara as an idol, as one of their popular songs described their ideal postgraduation career path based on his story:Footnote 57

Aside from the success of his farm, other factors also contributed to the ascension of Saibara Seitō as the face of Japanese agricultural expansion. Aware of the rise of anti-Japanese sentiment on the West Coast, he understood that obtaining American citizenship and the associated political rights was crucial to the migration endeavor in the long run, thus he immediately applied for naturalization after the land purchase in Texas. However, as the Naturalization Act of 1870 permitted the naturalization of only Caucasian and African immigrants, the immigration authority in the state of Texas received Saibara’s application without giving him a clear answer.Footnote 59 The ambivalent attitude of Texas authority led the Japanese expansionists to believe that there was a possible pathway to naturalization for them. In their imaginations, Saibara’s success in developing rice farming in Texas and his resolution of permanent settlement would eventually earn him citizenship in the most civilized country of the world.

To the Japanese expansionists, the development of rice farming and the existing race relations in Texas made the state a perfect place for the Japanese to subvert white racism. After an investigation of Saibara’s farm, politician Matsudaira Masanao observed that unlike the West Coast, Texas did not have a lot of Chinese or black people due to racial animosity; in contrast, the Japanese migrants were welcomed by the white settlers. Armed with their world-famous expertise in rice farming, the Japanese were treated even better than Caucasians from Italy and Spain.

While the lower-class Japanese laborers were targeted by white exclusionists on the West Coast, Matsudaira believed that capable and educated Japanese migrants like Saibara could easily gain American citizenship in Texas. As Japanese success in Texas would prove their assimilability into the white men’s world, it would win for Japanese the right of naturalization in the entire country. Such a development would allow the Japanese settlers to participate in American politics in order to consolidate Japanese frontiers in the United States.Footnote 60

Seeing rice farming in Texas as a promising model that could bring about a better future for Japanese migrants in the United States, Japan’s Ministry of Foreign Affairs also provided political support to the movement. At the turn of the twentieth century, in order to avoid provoking further anti-Japanese sentiment on the American West Coast, the ministry had reduced Japanese labor migration to the United States. However, it gave a green light to those who intended to migrate to Texas as farmers, including both wealthy men like Saibara who would become big farm owners and small owner-farmers who would like to collectively manage a farm by pooling together their funds and labor. The Ministry of Foreign Affairs categorized the latter as collective farmers (kumiai nōfu) and managed to negotiate for their rights to migrate under the Gentlemen’s Agreement.Footnote 61 As a result, the doors of Texas remained open to Japanese agricultural migration, at least in theory, until the passage of Immigration Act of 1924.

The End of the Texas Migration Campaign

To the severe disappointment of most Japanese expansionists of the day, the wave of Texas migration quickly ebbed and faded out from Japanese public discourse before the first decade of the twentieth century came to an end. While natural disasters and drops in rice prices due to overproduction had dealt substantial setbacks to Japanese farms in Texas,Footnote 62 it was the shortage of labor that fundamentally doomed these ventures. Matsuhara Ichio, the Japanese consul in Chicago, observed in a report to Tokyo in 1908 that after migrating to the United States, many Japanese farmhands quickly abandoned their posts. Most of them left for California, where they picked up better-paying labor jobs.Footnote 63 The lack of leisure facilities in rural Texas was another reason why Japanese migrants were eager to quit the farm life and move elsewhere.Footnote 64

These migrants had high mobility because of the particular way in which they were recruited. Since it was difficult to persuade those who had either fortune or land to abandon their properties in Japan, Japanese farm owners in Texas did not require their employees to make any financial commitment to the farm. As a result, contrary to the expectation of the Japanese agricultural expansionists, Japanese farms in Texas ended up recruiting laborers, not shareholding farmers, from Japan. In order to circumvent the government restrictions on labor migrants, these farm laborers applied for their passports as collective farmers and presented themselves as small shareholders of Japanese farms in Texas. However, with little actual commitment to the farms, it was easy for these farm laborers to quit and move on.Footnote 65

Most Japanese farm owners preferred migrants from Japan to the local white, black, or Mexican farmers for two reasons. First, they trusted the farming skills of their compatriots because most of these migrants were previously farmers in Japan. Second, there was a language barrier between the Japanese farm owners and the locals.Footnote 66 The migrants from Japan thus constituted the primary labor source for Japanese farms in Texas, and their remigration to California and urban Texas left the farms mired in crisis.

Japanese farm owners responded to this crisis by working together to form the Texan Japanese Association (Tekisasu Nihonjin Kyōkai) in 1908. Immediately after its establishment, the association submitted an appeal to Japan’s minister of foreign affairs, Komura Jutarō, urging the imperial government to stop the remigration of the Japanese farm laborers from Texas through diplomatic means. However, this effort was doomed from the start because there were no legal ways for Tokyo to control the mobility of its subjects outside of the imperial territory.

The failure of the Texan Japanese Association’s appeal announced the end of Japanese agricultural migration in Texas. Faced with both a labor shortage and a drop in the price of rice, most Japanese farms went bankrupt before the end of the 1910s; their employees and owners either returned to Japan or remigrated to California.Footnote 67 Only a handful of them, including the farm owned by Saibara Seitō, were able to survive by reducing size and cultivating alternative crops.

A New Beginning: Farmer Migration and Brazil

Although the Texas campaign was short-lived, it marked a turning point in the evolution of Japanese Malthusian expansionism. It opened up a new chapter in the history of Japan’s migration-driven expansion marked by farmer migration. In response to anti-Japanese campaigns in North America and the deterioration of Japan’s rural economy during the first decades of the twentieth century, Japan’s migration-driven expansion underwent a major paradigm shift from labor migration to agrarian settlement.

Due to their diverse social and political backgrounds, during the previous decades Malthusian expansionists had imagined very different futures for Japan’s migrants—from businessmen to company employees, from plantation owners to farm laborers. The failure of the Texas campaign, however, convinced a growing number of Malthusian expansionists that becoming land-owning farmers was the only viable career path for Japanese migrants. This paradigm change was further cemented by the failed Japanese American enlightenment campaign in the 1910s and 1920s, a subject that will be examined in the next chapter.

The failure in Texas also forced Japanese expansionists to explore alternative destinations, leading them to cast their gaze on the “empty and rich lands” of Latin America. The initial architect of Texas campaign Uchida Sadatsuchi became the Japanese consul in the state of São Paulo, Brazil, in 1907. He immediately found Brazil to be a more suitable place for Japanese migration than the United States due to a perceived absence of racism. He did not hesitate to support migration leader Mizuno Ryū through diplomatic means, enabling him to bring the first official group of Japanese migrants to Brazil on the ship Kasato-maru in 1908.Footnote 68 The growing Japanese communities in Brazil also attracted the attention of Saibara Seitō. Disappointed by the rejection of his citizenship application in the United States, Saibara entrusted his Texan farm to his son and joined Japanese expansion in Brazil by starting a farm in the state of São Paulo in 1918. While his farming career in São Paulo was not as successful as expected, he moved north to the state of Pará in 1928 as an employee of Japan’s South America Colonization Company (Nanbei Takushoku Kabushiki Gaisha) to experiment with Japanese farming at the mouth of the Amazon River.Footnote 69

Conclusion

At the end of the 1906 novel The Broken Commandment, protagonist Segawa Ushimatsu decides to sail to Texas and start his new life there as a rice farmer. Though a work of fiction, this book was an example of the Japanese general public’s awareness of the opportunity of taking up rice farming in Texas. The rise of Japanese farmer migration to Texas, while similar to the wave of labor migration to the US West Coast in terms of its heimin-centered base, represented a turning point in the evolution of Japanese migration-based expansion. It marked the beginning of farmer-centered expansion with the goal of long-term agricultural settlement.

At the end of the nineteenth century, Japan lost its self-sufficiency in rice. As a result, it had to import its main staple food from Taiwan and the Korean Peninsula. The decline of the agricultural sector triggered a debate on agriculture’s importance to the nation. Representing two opposing sides of the debate, Yokoi Toshiyoki and Nitobe Inazō held contrasting views on the nation’s best course of development, but they both believed that agriculture had a fundamental role to play in Japan’s overall economic growth, arguing for agriculture’s centrality in both Japan’s national identity and cultural tradition.

Malthusian expansionism provided a convenient solution for Japanese thinkers who sought to reverse the decline of agriculture while maintaining that the development of industry and commerce was vital to the empire’s success. They attributed the fundamental cause of rural depression to overpopulation in the countryside, which in turn led to the overall decline of agricultural productivity. Based on this assumption, they argued that the revival of agriculture could be achieved by relocating the surplus population overseas without major changes in the existing economic structure in society. Moreover, these surplus farmers in Japanese countryside, through migration and farming, would become powerful vanguards of the empire’s expansion project.

Aside from the calls for “rescuing” Japanese agriculture, the promotion of farmer migration to Texas was also a response to rising anti-Japanese sentiment on the American West Coast that primarily targeted Japanese labor migrants. In this context, rice farming in Texas was deemed as the best alternative because Japanese farmers, the expansionists believed, would find a warmer welcome in the United States than would laborers. Moreover, they were better equipped to put down permanent roots, thereby establishing the Japanese as an expansionist race in the American frontier. They expected that the success of Japanese rice farmers in Texas would reassert the racial superiority of the Japanese in the world through their achievements in agriculture.

However, a structural labor shortage quickly led to the decline of Japanese rice farming in Texas. The failure of this project and the enactment of the Gentlemen’s Agreement forced the Japanese expansionists to revise their blueprint of agricultural migration. The Gentlemen’s Agreement had shut America’s doors to Japanese migrant laborers, but it was still possible for Japanese to migrate to America through familial relations. It thus ushered in the era of picture brides, when hundreds of thousands of Japanese women moved to the US West Coast. Japanese migration leaders strived to appease the anti-Japanese sentiment by encouraging Japanese Americans, through education and moral suasion, to assimilate into the mainstream – in other words, Caucasian – society. At the same time, thinkers and doers of Japanese expansion began to explore alternative migration destinations in Northeast Asia, Latin America, and the South Seas to carry out their versions of farmer-centered expansion.

In response to the ongoing Japanese exclusion campaigns in the United States represented by the promulgation of Alien Land Laws in a few states in the American West, Japanese policymakers, intellectuals, and migration movement leaders conducted heated debates that redefined the meaning, pattern, and direction of the empire’s future expansion. Yoshimura Daijirō’s failure to sustain his Texan farm and the enactment of the Gentlemen’s Agreement did not hamper his zeal for embracing Western civilization. He participated in the activities of the Great Japan Civilization Association (Dai Nihon Bunmei Kyōkai), an organization founded by leading politician Ōkuma Shigenobu with the goal of winning Japan membership in the white men’s world.Footnote 70 The mission of the Great Japan Civilization Association was similar to that of another organization formed in 1914, the Japanese Emigration Association (Nihon Imin Kyōkai), in which Ōkuma also played a central role. As the next chapter discusses at length, the Emigration Association became a headquarters for campaigns launched by Japanese expansionists to facilitate Japanese American assimilation into white American society. The next chapter also discusses how the model of farmer migration evolved in the years between the enactment of the Gentlemen’s Agreement and the passage of the Immigration Act of 1924, when the American doors were completely shut to Japanese immigration. It explains in detail why, among the different campaigns in various areas around the Pacific Rim, it was in Brazil that the Japanese farmer migration turned out to be the most successful.