1 Sums of finite sets of integers

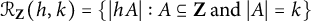

An additive abelian semigroup is simply a nonempty set G with a commutative and associative binary operation, written additively. For every nonempty subset A of the semigroup G, the h-fold sumset of A is the set of all sums of h not necessarily distinct elements of A, that is,

We define

![]() $0A = \{0\}$

. A core part of additive number theory is the study of sumsets of finite subsets of additive abelian semigroups. We define the sumset size set

$0A = \{0\}$

. A core part of additive number theory is the study of sumsets of finite subsets of additive abelian semigroups. We define the sumset size set

A basic problem is to understand this set.

We consider the set

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

of sumset sizes of finite sets of integers. The dilation of a set A by

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

of sumset sizes of finite sets of integers. The dilation of a set A by

![]() $\lambda $

is the set

$\lambda $

is the set

![]() $ \lambda \ast A = \{\lambda a : a \in A\}$

. Sets A and B are affinely equivalent if there are numbers

$ \lambda \ast A = \{\lambda a : a \in A\}$

. Sets A and B are affinely equivalent if there are numbers

![]() $\lambda \neq 0$

and

$\lambda \neq 0$

and

![]() $\mu $

such that

$\mu $

such that

If A and B are affinely equivalent, then

and so

![]() $|hB| = |hA|$

. Because sumset size is an affine invariant, we have

$|hB| = |hA|$

. Because sumset size is an affine invariant, we have

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k) = \mathcal R_{ \mathbf N _0}(h,k)$

. It is proved in [Reference Nathanson9] that

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k) = \mathcal R_{ \mathbf N _0}(h,k)$

. It is proved in [Reference Nathanson9] that

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z^n}(h,k) = \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

for all positive integers n.

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z^n}(h,k) = \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

for all positive integers n.

There are simple lower and upper bounds for

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

. We have

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

. We have

and, if

![]() $ A \subseteq \mathbf Z \text { and } |A| = k $

, then

$ A \subseteq \mathbf Z \text { and } |A| = k $

, then

![]() $|hA| = hk-h+1$

if and only if A is an arithmetic progression of length k. Similarly, if A is a

$|hA| = hk-h+1$

if and only if A is an arithmetic progression of length k. Similarly, if A is a

![]() $B_h$

-set, that is, a set all of whose h-fold sums are distinct, then

$B_h$

-set, that is, a set all of whose h-fold sums are distinct, then

![]() $|hA| = \binom {h+k-1}{h}$

and

$|hA| = \binom {h+k-1}{h}$

and

Beginning with the work of Freiman [Reference Freiman3, Reference Freiman4, Reference Nathanson7], a large research literature has investigated finite sets whose sumsets are very small, that is, close to the minimum size. There is also a large research literature [Reference O’Bryant11] on sets whose sumsets are close to the maximum size.

What is surprising is the lack of attention to the full range of sumset sizes of finite sets of integers. Possibly, the only published statement related to this problem occurs in a 1983 paper by Erdős and Szemerédi [Reference Erdős and Szemerédi1] about the number of sums and products. They wrote:

Let

![]() $2k-1 \leq t \leq \frac {k^2+k}{2}$

. It is easy to see that one can find a sequence of integers

$2k-1 \leq t \leq \frac {k^2+k}{2}$

. It is easy to see that one can find a sequence of integers

![]() $a_1 < \cdots < a_k$

so that there should be exactly t distinct integers in the sequence

$a_1 < \cdots < a_k$

so that there should be exactly t distinct integers in the sequence

![]() $a_i+a_j, 1 \leq i \leq j \leq k$

.

$a_i+a_j, 1 \leq i \leq j \leq k$

.

Theorem 1 refines this assertion. For real numbers u and v, define the integer interval

Theorem 1 (Nathanson [Reference Nathanson8])

For all positive integers k,

Moreover, for all

![]() $t \in \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(2,k)$

, there exists a set

$t \in \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(2,k)$

, there exists a set

![]() $A \subseteq \left [0,2^k -1 \right ]$

such that

$A \subseteq \left [0,2^k -1 \right ]$

such that

![]() $|A| = k$

and

$|A| = k$

and

![]() $\left | 2A \right | = t$

.

$\left | 2A \right | = t$

.

Here are two important observations. First, the set of sumset sizes

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(2,k)$

is known exactly, and it is an integer interval: There is no “missing number” between

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(2,k)$

is known exactly, and it is an integer interval: There is no “missing number” between

![]() $\min \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(2,k)$

and

$\min \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(2,k)$

and

![]() $\max \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(2,k)$

. Second, there is a finite, albeit exponential, upper bound on the amount of computation needed to find a set A with

$\max \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(2,k)$

. Second, there is a finite, albeit exponential, upper bound on the amount of computation needed to find a set A with

![]() $|A| = k$

and

$|A| = k$

and

![]() $|2A| = t$

for all

$|2A| = t$

for all

![]() $t \in \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(2,k)$

. For all

$t \in \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(2,k)$

. For all

![]() $h \geq 2$

, the set

$h \geq 2$

, the set

![]() $ \mathcal R(h,k)$

is finite and so there exists an integer N such that, for all

$ \mathcal R(h,k)$

is finite and so there exists an integer N such that, for all

![]() $t \in \mathcal R(h,k)$

, there is a set A with

$t \in \mathcal R(h,k)$

, there is a set A with

![]() $|A| = k$

,

$|A| = k$

,

![]() $|hA| = t$

, and

$|hA| = t$

, and

![]() $A \subseteq [0,N]$

. Let

$A \subseteq [0,N]$

. Let

![]() $N(h,k)$

be the least such number. By Theorem 1,

$N(h,k)$

be the least such number. By Theorem 1,

![]() $N(2,k) < 2^k$

. For

$N(2,k) < 2^k$

. For

![]() $h \geq 3$

, there is the following exponential upper bound.

$h \geq 3$

, there is the following exponential upper bound.

Theorem 2 (Nathanson [Reference Nathanson9])

For all

![]() $h \geq 3$

and

$h \geq 3$

and

![]() $k \geq 3$

,

$k \geq 3$

,

It would be of interest to know if, for fixed h, there is a subexponential or even polynomial upper bound for

![]() $N(h,k)$

.

$N(h,k)$

.

We have

and

Theorem 1 describes

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(2,k)$

. Thus, the problem is to understand

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(2,k)$

. Thus, the problem is to understand

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k) $

for

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k) $

for

![]() $h \geq 3$

and

$h \geq 3$

and

![]() $k \geq 3$

.

$k \geq 3$

.

Let

![]() $k = 3$

. From (1) and (2), we have

$k = 3$

. From (1) and (2), we have

In particular,

We have

$$ \begin{align*} 3\{0,1,2\} = [0,6] & \operatorname{\mathrm{\qquad\text{and}\qquad}} |3\{0,1,2\} | = 7 \\ 3\{0,1,3\} = [0,7] \cup \{9\} & \operatorname{\mathrm{\qquad\text{and}\qquad}} |3\{0,1,3\} | = 9 \\ 3\{0,1,4\} = [0,6] \cup \{8,9,12\} & \operatorname{\mathrm{\qquad\text{and}\qquad}} |3\{0,1,4\} | = 10 \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} 3\{0,1,2\} = [0,6] & \operatorname{\mathrm{\qquad\text{and}\qquad}} |3\{0,1,2\} | = 7 \\ 3\{0,1,3\} = [0,7] \cup \{9\} & \operatorname{\mathrm{\qquad\text{and}\qquad}} |3\{0,1,3\} | = 9 \\ 3\{0,1,4\} = [0,6] \cup \{8,9,12\} & \operatorname{\mathrm{\qquad\text{and}\qquad}} |3\{0,1,4\} | = 10 \end{align*} $$

and so

Where is 8? A computer search failed to find a set A of integers with

![]() $|A| = 3$

and

$|A| = 3$

and

![]() ${|3A| = 8}$

. Nathanson [Reference Nathanson8] proved that

${|3A| = 8}$

. Nathanson [Reference Nathanson8] proved that

![]() $8 \notin \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(3,3)$

, that is,

$8 \notin \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(3,3)$

, that is,

Why is there no 8 in

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(3,3)$

? There is a proof but not a reason.

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(3,3)$

? There is a proof but not a reason.

More generally, we have the following “missing number” result.

Theorem 3 (Nathanson [Reference Nathanson8])

For all

![]() $h \geq 3$

and

$h \geq 3$

and

![]() $k \geq 3$

,

$k \geq 3$

,

and so the sumset size set

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

is not an interval.

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

is not an interval.

Theorems 1 and 3 inspire this field of research. For

![]() $h \geq 3$

and

$h \geq 3$

and

![]() $k \geq 3$

, the sumset size set

$k \geq 3$

, the sumset size set

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

is not the integer interval defined by its minimum and maximum values. What is it? One can generate random sets A of size k, compute their sumset size

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

is not the integer interval defined by its minimum and maximum values. What is it? One can generate random sets A of size k, compute their sumset size

![]() $|hA|$

, and generate subsets of the set

$|hA|$

, and generate subsets of the set

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

. From these tables, one can formulate conjectures. Observation of gaps in tables of the sumset sizes of random subsets suggested the following result, which was proved by Vincent Schinina.

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

. From these tables, one can formulate conjectures. Observation of gaps in tables of the sumset sizes of random subsets suggested the following result, which was proved by Vincent Schinina.

Theorem 4 (Schinina [Reference Schinina14])

For all

![]() $h \geq 3$

and

$h \geq 3$

and

![]() $k \geq 3$

,

$k \geq 3$

,

and

For sets of size 3, there is the following result.

Theorem 5 (Nathanson [Reference Nathanson8])

For all positive integers h,

Thus, the sumset sizes of 3-element sets are differences of triangular numbers. We know

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,3)$

, but the set

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,3)$

, but the set

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,4)$

of sumset sizes of 4-element sets is still a mystery.

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,4)$

of sumset sizes of 4-element sets is still a mystery.

While the computation of the sumset sizes of random finite sets of integers generates elements of the sumset size sets

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

, it is useful and important to have explicit constructions of finite sets and explicit families of sumset sizes in

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

, it is useful and important to have explicit constructions of finite sets and explicit families of sumset sizes in

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

. In Theorems 6 and 7 and Corollaries 1–7, we construct infinite families of such sets, and, in particular, interesting elements of

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

. In Theorems 6 and 7 and Corollaries 1–7, we construct infinite families of such sets, and, in particular, interesting elements of

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,4)$

.

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,4)$

.

2 Arithmetic progressions of intervals

Let

![]() $ \mathbf N _0 = \{0,1,2,3,\ldots \}$

be the set of nonnegative integers. For positive integers h and k, let

$ \mathbf N _0 = \{0,1,2,3,\ldots \}$

be the set of nonnegative integers. For positive integers h and k, let

$$\begin{align*}\mathcal X_{h,k} = \left\{ (x_1,\ldots, x_k) \in \mathbf N _0^k: \sum_{j=1}^k x_j = h\right\}. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\mathcal X_{h,k} = \left\{ (x_1,\ldots, x_k) \in \mathbf N _0^k: \sum_{j=1}^k x_j = h\right\}. \end{align*}$$

The set

![]() $ \mathcal X_{h,k}$

is invariant under permutations: For all

$ \mathcal X_{h,k}$

is invariant under permutations: For all

![]() $\sigma \in S_k$

, we have

$\sigma \in S_k$

, we have

![]() $(x_1,\ldots , x_k) \in \mathcal X_{h,k}$

if and only if

$(x_1,\ldots , x_k) \in \mathcal X_{h,k}$

if and only if

![]() $(x_{\sigma (1)},\ldots , x_{\sigma (k)}) \in \mathcal X_{h,k}$

.

$(x_{\sigma (1)},\ldots , x_{\sigma (k)}) \in \mathcal X_{h,k}$

.

Let

![]() $A = \{a_1,\ldots , a_k\} \subseteq \mathbf Z$

with

$A = \{a_1,\ldots , a_k\} \subseteq \mathbf Z$

with

![]() $|A| = k$

and let

$|A| = k$

and let

![]() $ \mathbf a = (a_1,\ldots , a_k) \in \mathbf Z^k$

. For

$ \mathbf a = (a_1,\ldots , a_k) \in \mathbf Z^k$

. For

![]() $ \mathbf x = (x_1,\ldots , x_k) \in \mathcal X_{h,k}$

, we define

$ \mathbf x = (x_1,\ldots , x_k) \in \mathcal X_{h,k}$

, we define

$$\begin{align*}\mathbf x \cdot \mathbf a = \left(x_1,\ldots, x_k) \cdot (a_1,\ldots, a_k \right) = \sum_{j=1}^k x_ja_j. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\mathbf x \cdot \mathbf a = \left(x_1,\ldots, x_k) \cdot (a_1,\ldots, a_k \right) = \sum_{j=1}^k x_ja_j. \end{align*}$$

Then,

![]() $ \mathbf x \cdot \mathbf a \in hA$

and

$ \mathbf x \cdot \mathbf a \in hA$

and

The vector

![]() $\mathbf a$

depends on the ordering of the elements of the set A, but, because

$\mathbf a$

depends on the ordering of the elements of the set A, but, because

![]() $ \mathcal X_{h,k}$

is

$ \mathcal X_{h,k}$

is

![]() $S_k$

-invariant, the sumset

$S_k$

-invariant, the sumset

![]() $hA$

is independent of the ordering of A.

$hA$

is independent of the ordering of A.

It is straightforward to check that, for all positive integers h and k,

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal X_{h,k} = \bigcup_{x_k=0}^{h} \left\{ (x_1,\ldots, x_{k-1}, x_k): (x_1,\ldots, x_{k-1}) \in \mathcal X_{h - x_k,k-1} \right\}. \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} \mathcal X_{h,k} = \bigcup_{x_k=0}^{h} \left\{ (x_1,\ldots, x_{k-1}, x_k): (x_1,\ldots, x_{k-1}) \in \mathcal X_{h - x_k,k-1} \right\}. \end{align} $$

The following terminology is useful. Let

![]() $u_1 \leq u_2$

. We say that there is a gap between integer intervals

$u_1 \leq u_2$

. We say that there is a gap between integer intervals

![]() $[u_1,v_1]$

and

$[u_1,v_1]$

and

![]() $[u_2,v_2]$

if there is an integer n such that

$[u_2,v_2]$

if there is an integer n such that

The integer intervals

![]() $[u_1,v_1]$

and

$[u_1,v_1]$

and

![]() $[u_2,v_2]$

have no gap if

$[u_2,v_2]$

have no gap if

![]() $u_2 \leq v_1+1$

or, equivalently if

$u_2 \leq v_1+1$

or, equivalently if

![]() $[u_1,v_1] \cup [u_2,v_2] $

is an integer interval.

$[u_1,v_1] \cup [u_2,v_2] $

is an integer interval.

Lemma 1 For all positive integers h and k,

$$\begin{align*}\mathcal I_{h,k} = \left\{ \sum_{j=2}^{k} (j-1) x_j : (x_1,\ldots, x_{k}) \in \mathcal X_{h,k} \right\} = [0, (k-1) h ]. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\mathcal I_{h,k} = \left\{ \sum_{j=2}^{k} (j-1) x_j : (x_1,\ldots, x_{k}) \in \mathcal X_{h,k} \right\} = [0, (k-1) h ]. \end{align*}$$

Proof The proof is by induction on k. For

![]() $k=1$

, we have

$k=1$

, we have

![]() $ \mathcal X_{h,1} = \{(h)\}$

and

$ \mathcal X_{h,1} = \{(h)\}$

and

![]() $ \mathcal I_{h,1} = \{0\} = [0,0]$

. For

$ \mathcal I_{h,1} = \{0\} = [0,0]$

. For

![]() $k =2$

, we have

$k =2$

, we have

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal X_{h,2} &= \left\{ (x_1,x_2) \in \mathbf N _0^2: x_1+x_2= h\right\} \\ & = \left\{ (h-x_2,x_2) \in \mathbf N _0^2: x_2 \in [0,h] \right\} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal X_{h,2} &= \left\{ (x_1,x_2) \in \mathbf N _0^2: x_1+x_2= h\right\} \\ & = \left\{ (h-x_2,x_2) \in \mathbf N _0^2: x_2 \in [0,h] \right\} \end{align*} $$

and so

Let

![]() $k \geq 3$

and assume that

$k \geq 3$

and assume that

![]() $ \mathcal I_{h,k-1} = [0, (k-2) h ]$

for all

$ \mathcal I_{h,k-1} = [0, (k-2) h ]$

for all

![]() $h \geq 1$

.

$h \geq 1$

.

If

![]() $x_k \in [0,h-1]$

, then

$x_k \in [0,h-1]$

, then

It follows that there is no gap between the integer intervals

and

and so their union is the integer interval

Applying relation (4), we obtain

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal I_{h,k} & = \left\{ \sum_{j=2}^{k} (j-1) x_j : (x_1,\ldots, x_k) \in \mathcal X_{h,k} \right\} \\ & = \left\{ (k-1)x_k+ \sum_{j=2}^{k-1} (j-1) x_j : (x_1,\ldots, x_k) \in \mathcal X_{h,k} \right\} \\ & = \bigcup_{x_k=0}^h \left\{ (k-1)x_k+ \left\{ \sum_{j=2}^{k-1} (j-1) x_j : (x_1,\ldots, x_{k-1}) \in \mathcal X_{h - x_k,k-1} \right\} \right\} \\& = \bigcup_{x_k=0}^h \left\{ (k-1)x_k+ \mathcal I_{h - x_k,k-1} \right\} \\ & = \bigcup_{x_k=0}^h \left\{ (k-1)x_k+ [0, (k-2) (h - x_k) ]\right\} \\ & = \bigcup_{x_k=0}^h \left[ (k-1)x_k, (k-2)h + x_k \right]. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \mathcal I_{h,k} & = \left\{ \sum_{j=2}^{k} (j-1) x_j : (x_1,\ldots, x_k) \in \mathcal X_{h,k} \right\} \\ & = \left\{ (k-1)x_k+ \sum_{j=2}^{k-1} (j-1) x_j : (x_1,\ldots, x_k) \in \mathcal X_{h,k} \right\} \\ & = \bigcup_{x_k=0}^h \left\{ (k-1)x_k+ \left\{ \sum_{j=2}^{k-1} (j-1) x_j : (x_1,\ldots, x_{k-1}) \in \mathcal X_{h - x_k,k-1} \right\} \right\} \\& = \bigcup_{x_k=0}^h \left\{ (k-1)x_k+ \mathcal I_{h - x_k,k-1} \right\} \\ & = \bigcup_{x_k=0}^h \left\{ (k-1)x_k+ [0, (k-2) (h - x_k) ]\right\} \\ & = \bigcup_{x_k=0}^h \left[ (k-1)x_k, (k-2)h + x_k \right]. \end{align*} $$

Because there is no gap between consecutive pairs of these

![]() $h+1$

intervals, we obtain

$h+1$

intervals, we obtain

This completes the proof.

Theorem 6 Let k, a, b, and

![]() $\ell $

be positive integers with

$\ell $

be positive integers with

![]() $k=a\ell $

and

$k=a\ell $

and

![]() $a \leq b$

. Let

$a \leq b$

. Let

be the

![]() $\ell $

-term arithmetic progression with difference b and smallest element 0. Let A be the

$\ell $

-term arithmetic progression with difference b and smallest element 0. Let A be the

![]() $\ell $

-term arithmetic progression of translates of the interval

$\ell $

-term arithmetic progression of translates of the interval

![]() $[0, a-1 ]$

:

$[0, a-1 ]$

:

$$ \begin{align*} A & = P+[0,a-1] = \bigcup_{j=1}^{\ell} \left( (j-1)b + [0,a-1] \right). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} A & = P+[0,a-1] = \bigcup_{j=1}^{\ell} \left( (j-1)b + [0,a-1] \right). \end{align*} $$

Then,

![]() $|A| = k$

.

$|A| = k$

.

For every positive integer h, let

be the

![]() $(h(\ell -1) +1)$

-term arithmetic progression with difference b and smallest element 0. The sumset

$(h(\ell -1) +1)$

-term arithmetic progression with difference b and smallest element 0. The sumset

![]() $hA$

is an

$hA$

is an

![]() $(h(\ell -1) +1)$

-term arithmetic progression of translates of the interval

$(h(\ell -1) +1)$

-term arithmetic progression of translates of the interval

![]() $[0, h(a-1)]$

:

$[0, h(a-1)]$

:

and

$$ \begin{align} |hA| = \begin{cases} (a+ b(\ell-1) - 1)h+1 & \text{if } a \leq b \leq (a-1)h+1 \\ (a-1)(\ell-1)h^2 + (a+\ell-2)h +1 & \text{if } b \geq h(a-1) +1. \end{cases} \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} |hA| = \begin{cases} (a+ b(\ell-1) - 1)h+1 & \text{if } a \leq b \leq (a-1)h+1 \\ (a-1)(\ell-1)h^2 + (a+\ell-2)h +1 & \text{if } b \geq h(a-1) +1. \end{cases} \end{align} $$

Proof We have

$$ \begin{align*} A & = P+[0,a-1] \\ & = \bigcup_{j=1}^{\ell} [ (j-1)b, \ a -1 + (j-1)b ] \\ & = \bigcup_{j=1}^{\ell } L_j, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} A & = P+[0,a-1] \\ & = \bigcup_{j=1}^{\ell} [ (j-1)b, \ a -1 + (j-1)b ] \\ & = \bigcup_{j=1}^{\ell } L_j, \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $L_j$

is the integer interval

$L_j$

is the integer interval

and

![]() $|L_j|=a$

. The inequality

$|L_j|=a$

. The inequality

![]() $a \leq b$

implies

$a \leq b$

implies

![]() $a -1 +(j-1)b < jb$

for all

$a -1 +(j-1)b < jb$

for all

![]() $j \in [1,\ell ]$

and so the integer intervals

$j \in [1,\ell ]$

and so the integer intervals

![]() $L_j$

are pairwise disjoint and

$L_j$

are pairwise disjoint and

![]() $|A| = \sum _{j=1}^{\ell } |L_j| = a\ell = k$

.

$|A| = \sum _{j=1}^{\ell } |L_j| = a\ell = k$

.

If

![]() $ (x_1,\ldots , x_{\ell }) \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell }$

, then

$ (x_1,\ldots , x_{\ell }) \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell }$

, then

![]() $\sum _{j=1}^k x_j = h$

. Applying Lemma 1 with

$\sum _{j=1}^k x_j = h$

. Applying Lemma 1 with

![]() $k=\ell $

, we have

$k=\ell $

, we have

$$ \begin{align*} hA & = h\left(\bigcup_{j=1}^{\ell } L_j \right) = \bigcup_{ \mathbf x = (x_1,\ldots, x_{\ell}) \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell} } \left(x_1 L_1 + \cdots + x_{\ell} L_{\ell} \right) \\ & = \bigcup_{ \mathbf x \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell} } \sum_{j=1}^{\ell} [ (j-1) x_j b, (a-1) x_j + (j-1) x_j b ] \\ & = \bigcup_{ \mathbf x \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell}} \left[ \sum_{j=1}^{\ell } (j-1) x_j b, \sum_{j=1}^{\ell } (a-1) x_j + \sum_{j=1}^{\ell } (j-1) x_j b \right] \\ & = \bigcup_{ \mathbf x \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell}} \left[ \sum_{j=2}^{\ell } (j-1) x_j b, h(a-1) + \sum_{j=2}^{\ell } (j-1) x_j b \right] \\ & = \bigcup_{ \mathbf x \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell}} \left( b \sum_{j=2}^{\ell } (j-1) x_j + \left[ 0, h(a-1) \right] \right) \\ & = \left\{ b \sum_{j=2}^{\ell } (j-1) x_j : \mathbf x \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell}\right\} + \left[ 0, h (a-1) \right] \\ & = b\ast \mathcal I_{h,\ell} + \left[ 0, h (a-1) \right] \\ & = b\ast [0, (\ell -1) h ] + \left[ 0, h (a-1) \right] \\ & = Q + \left[ 0, h (a-1) \right]. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} hA & = h\left(\bigcup_{j=1}^{\ell } L_j \right) = \bigcup_{ \mathbf x = (x_1,\ldots, x_{\ell}) \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell} } \left(x_1 L_1 + \cdots + x_{\ell} L_{\ell} \right) \\ & = \bigcup_{ \mathbf x \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell} } \sum_{j=1}^{\ell} [ (j-1) x_j b, (a-1) x_j + (j-1) x_j b ] \\ & = \bigcup_{ \mathbf x \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell}} \left[ \sum_{j=1}^{\ell } (j-1) x_j b, \sum_{j=1}^{\ell } (a-1) x_j + \sum_{j=1}^{\ell } (j-1) x_j b \right] \\ & = \bigcup_{ \mathbf x \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell}} \left[ \sum_{j=2}^{\ell } (j-1) x_j b, h(a-1) + \sum_{j=2}^{\ell } (j-1) x_j b \right] \\ & = \bigcup_{ \mathbf x \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell}} \left( b \sum_{j=2}^{\ell } (j-1) x_j + \left[ 0, h(a-1) \right] \right) \\ & = \left\{ b \sum_{j=2}^{\ell } (j-1) x_j : \mathbf x \in \mathcal X_{h,\ell}\right\} + \left[ 0, h (a-1) \right] \\ & = b\ast \mathcal I_{h,\ell} + \left[ 0, h (a-1) \right] \\ & = b\ast [0, (\ell -1) h ] + \left[ 0, h (a-1) \right] \\ & = Q + \left[ 0, h (a-1) \right]. \end{align*} $$

This proves (5).

To obtain the sumset size formula (6), we write

![]() $hA$

as a union of intervals:

$hA$

as a union of intervals:

$$ \begin{align*} hA &= \bigcup_{j=0}^{ (\ell -1) h} \left[ bj, bj + h (a-1) \right]. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} hA &= \bigcup_{j=0}^{ (\ell -1) h} \left[ bj, bj + h (a-1) \right]. \end{align*} $$

If

![]() $b \geq h(a-1)+1$

, then the

$b \geq h(a-1)+1$

, then the

![]() $(\ell -1) h +1$

intervals are pairwise disjoint and

$(\ell -1) h +1$

intervals are pairwise disjoint and

If

![]() $a \leq b \leq h(a-1)+1$

, then there are no gaps between successive intervals and so

$a \leq b \leq h(a-1)+1$

, then there are no gaps between successive intervals and so

and

This completes the proof.

The following results are immediate consequences of Theorem 6.

Corollary 1 Let h and k be positive integers. If a and

![]() $\ell $

are positive integers such that

$\ell $

are positive integers such that

![]() $k=a\ell $

, then the sumset size set

$k=a\ell $

, then the sumset size set

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

contains the arithmetic progression

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

contains the arithmetic progression

Corollary 2 For every positive integer h, the sumset size set

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,4)$

contains the h-term arithmetic progression

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,4)$

contains the h-term arithmetic progression

![]() $\{bh+1:b\in [3,h+2] \}$

.

$\{bh+1:b\in [3,h+2] \}$

.

Corollary 3 If

![]() $k = a^2$

, then

$k = a^2$

, then

![]() $\left ((a-1)h+1\right )^2 \in \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

.

$\left ((a-1)h+1\right )^2 \in \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

.

3 Sums of intervals of different lengths

Consider a finite set that is the union of two intervals of different lengths. Let a, b, and c be nonnegative integers with

![]() $a < b$

and

$a < b$

and

![]() $a \neq c$

, and let

$a \neq c$

, and let

![]() $A = [0,a] \cup [b,b+c]$

. The set A is affinely equivalent to the set

$A = [0,a] \cup [b,b+c]$

. The set A is affinely equivalent to the set

$$ \begin{align*} A' & = (-1)\ast A + b+c \\ & = [0,c] \cup [ b+c-a, b+c] \\ & = [0,a'] \cup [b', b'+c'] \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} A' & = (-1)\ast A + b+c \\ & = [0,c] \cup [ b+c-a, b+c] \\ & = [0,a'] \cup [b', b'+c'] \end{align*} $$

with

![]() $a'=c < b+c-a = b'$

, and

$a'=c < b+c-a = b'$

, and

![]() $c' = a$

. If

$c' = a$

. If

![]() $a < c$

, then

$a < c$

, then

![]() $a'> c'$

. Moreover,

$a'> c'$

. Moreover,

![]() $|A| = |A'|$

and

$|A| = |A'|$

and

![]() $|hA| = |hA'|$

. Thus, it suffices to consider only the case

$|hA| = |hA'|$

. Thus, it suffices to consider only the case

![]() $a>c$

.

$a>c$

.

Note that the case

![]() $a=c$

(that is,

$a=c$

(that is,

![]() $A = [0,a] \cup [b,b+a] = \{0,b\}+[0,a]$

) is a special case of Theorem 6.

$A = [0,a] \cup [b,b+a] = \{0,b\}+[0,a]$

) is a special case of Theorem 6.

The integer part (also called the floor) of the real number w, denoted

![]() $[w]$

, is the unique integer n such that

$[w]$

, is the unique integer n such that

![]() $n \leq w < n+1$

. There should be no notational confusion between

$n \leq w < n+1$

. There should be no notational confusion between

![]() $[u,v]$

and

$[u,v]$

and

![]() $[w]$

.

$[w]$

.

Theorem 7 Let a, b, and c be integers with

![]() $0 \leq c < a < b$

and let

$0 \leq c < a < b$

and let

Let

![]() $h \geq 2$

and

$h \geq 2$

and

If

![]() $b> ha$

, then

$b> ha$

, then

$$ \begin{align} |hA| = (h+1)\left( 1 + \frac{h(a+c)}{2} \right). \end{align} $$

$$ \begin{align} |hA| = (h+1)\left( 1 + \frac{h(a+c)}{2} \right). \end{align} $$

If

![]() $a < b \leq ha$

, then

$a < b \leq ha$

, then

Proof We have

$$ \begin{align*} hA & = \bigcup_{i=0}^h \left( (h-i) [0,a] + i[b,b+c] \right) \\ & = \bigcup_{i=0}^h [ib, (h-i)a+ i(b+c)] \\ & = \bigcup_{i=0}^h L_i, \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} hA & = \bigcup_{i=0}^h \left( (h-i) [0,a] + i[b,b+c] \right) \\ & = \bigcup_{i=0}^h [ib, (h-i)a+ i(b+c)] \\ & = \bigcup_{i=0}^h L_i, \end{align*} $$

where

![]() $L_i$

is the integer interval

$L_i$

is the integer interval

$$ \begin{align*} L_i & = [ib, (h-i)a+ i(b+c) ] \\ & = [ib, ha +i(b-a+c)] \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} L_i & = [ib, (h-i)a+ i(b+c) ] \\ & = [ib, ha +i(b-a+c)] \end{align*} $$

and

Because

![]() $b \geq 1$

, the lower bounds of the intervals

$b \geq 1$

, the lower bounds of the intervals

![]() $L_0, L_1,\ldots , L_h$

are strictly increasing. Let

$L_0, L_1,\ldots , L_h$

are strictly increasing. Let

![]() $i \in [0,h-1]$

. Because

$i \in [0,h-1]$

. Because

![]() $a> c$

, the intervals

$a> c$

, the intervals

![]() $L_i$

and

$L_i$

and

![]() $L_{i+1}$

are disjoint if and only if

$L_{i+1}$

are disjoint if and only if

if and only if

Let

Thus, for

![]() $i \in [0,h-1]$

, the intervals

$i \in [0,h-1]$

, the intervals

![]() $L_i$

and

$L_i$

and

![]() $L_{i+1}$

are disjoint if and only if

$L_{i+1}$

are disjoint if and only if

Thus, the

![]() $h+1$

intervals

$h+1$

intervals

![]() $L_i$

are pairwise disjoint if and only if

$L_i$

are pairwise disjoint if and only if

![]() $i_0 \leq -1$

or, equivalently, if and only if

$i_0 \leq -1$

or, equivalently, if and only if

![]() $b> ha$

. In this case,

$b> ha$

. In this case,

$$ \begin{align*} |hA| & = \left| \bigcup_{i=0}^h L_i \right| = \sum_{i=0}^h \left| L_i \right| \\ & = \sum_{i=0}^h \left( ha + 1 - i (a-c) \right) \\ & = (h+1) \left( ha + 1 \right) - \frac{h(h+1)(a-c)}{2} \\ & = (h+1)\left( 1 + \frac{h(a+c)}{2} \right). \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} |hA| & = \left| \bigcup_{i=0}^h L_i \right| = \sum_{i=0}^h \left| L_i \right| \\ & = \sum_{i=0}^h \left( ha + 1 - i (a-c) \right) \\ & = (h+1) \left( ha + 1 \right) - \frac{h(h+1)(a-c)}{2} \\ & = (h+1)\left( 1 + \frac{h(a+c)}{2} \right). \end{align*} $$

If

![]() $b \leq ha$

or, equivalently, if

$b \leq ha$

or, equivalently, if

![]() $i_0 \geq 0$

, then the

$i_0 \geq 0$

, then the

![]() $h-i_0-1$

intervals

$h-i_0-1$

intervals

![]() $L_{i_0+2},L_{i_0+3}, \ldots , L_h$

are pairwise disjoint and

$L_{i_0+2},L_{i_0+3}, \ldots , L_h$

are pairwise disjoint and

![]() $L_i \cap L_{i+1} \neq \emptyset $

for

$L_i \cap L_{i+1} \neq \emptyset $

for

![]() $i \in [0,i_0]$

. It follows that

$i \in [0,i_0]$

. It follows that

$$\begin{align*}L_0^* = \bigcup_{i=0}^{i_0+1} L_i = [0, ha + (i_0+1)(b-a+c)] \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}L_0^* = \bigcup_{i=0}^{i_0+1} L_i = [0, ha + (i_0+1)(b-a+c)] \end{align*}$$

and

Moreover,

$$ \begin{align*} \left| \bigcup_{i=i_0+2}^h L_i \right| & = \sum_{i=i_0+2}^h |L_i | = \sum_{i=i_0+2}^h( ha + 1- i (a-c)) \\ & = (h-i_0-1)(ha + 1) - \frac{(h+i_0+2)(h-i_0-1)(a-c)}{2} \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} \left| \bigcup_{i=i_0+2}^h L_i \right| & = \sum_{i=i_0+2}^h |L_i | = \sum_{i=i_0+2}^h( ha + 1- i (a-c)) \\ & = (h-i_0-1)(ha + 1) - \frac{(h+i_0+2)(h-i_0-1)(a-c)}{2} \end{align*} $$

and

$$\begin{align*}L_0^* \cap \left( \bigcup_{i=i_0+2}^h L_i \right) = \left( \bigcup_{i=0}^{i_0+1} L_i \right) \cap \left( \bigcup_{i=i_0+2}^h L_i \right) = \emptyset. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}L_0^* \cap \left( \bigcup_{i=i_0+2}^h L_i \right) = \left( \bigcup_{i=0}^{i_0+1} L_i \right) \cap \left( \bigcup_{i=i_0+2}^h L_i \right) = \emptyset. \end{align*}$$

We obtain

$$ \begin{align*} |hA| & = \left| \bigcup_{i=0}^h L_i \right| = \left| L_0^* \right| + \sum_{i=i_0+2}^h \left| L_i \right| \\ & = (i_0+1)(b-a+c) + (h-i_0)(ha + 1) \\ & \qquad - \frac{(h+i_0+2)(h-i_0-1)(a-c)}{2} \\ & = (i_0+1) b + (h-i_0)( ha + 1) - \frac{(h+i_0+1)(h-i_0)(a-c)}{2}. \end{align*} $$

$$ \begin{align*} |hA| & = \left| \bigcup_{i=0}^h L_i \right| = \left| L_0^* \right| + \sum_{i=i_0+2}^h \left| L_i \right| \\ & = (i_0+1)(b-a+c) + (h-i_0)(ha + 1) \\ & \qquad - \frac{(h+i_0+2)(h-i_0-1)(a-c)}{2} \\ & = (i_0+1) b + (h-i_0)( ha + 1) - \frac{(h+i_0+1)(h-i_0)(a-c)}{2}. \end{align*} $$

This completes the proof.

Corollary 4 Let

![]() $h \geq 2$

and

$h \geq 2$

and

![]() $k \geq 3$

.

$k \geq 3$

.

If

![]() $b> h(k-2)$

, then the set

$b> h(k-2)$

, then the set

![]() $A= [0,k-2] \cup \{b\}$

satisfies

$A= [0,k-2] \cup \{b\}$

satisfies

$$\begin{align*}|hA| = (h+1)\left( 1 + \frac{h(k-2)}{2} \right). \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}|hA| = (h+1)\left( 1 + \frac{h(k-2)}{2} \right). \end{align*}$$

If

![]() $b \in [k-1, h(k-2)]$

, then there exist unique integers

$b \in [k-1, h(k-2)]$

, then there exist unique integers

![]() $i_0 \in [0,h-2]$

and

$i_0 \in [0,h-2]$

and

![]() ${r \in [0,k-3]}$

such that

${r \in [0,k-3]}$

such that

and the set

![]() $A= [0,k-2] \cup \{b\}$

satisfies

$A= [0,k-2] \cup \{b\}$

satisfies

Proof This follows directly from Theorem 7 with

![]() $a=k-2$

and

$a=k-2$

and

![]() $c=0$

.

$c=0$

.

Corollary 5 For all

![]() $h \geq 2$

,

$h \geq 2$

,

and, for all

![]() $i_0 \in [0,h-2]$

and

$i_0 \in [0,h-2]$

and

![]() $r \in [0,1]$

,

$r \in [0,1]$

,

Proof Apply Corollary 4 with

![]() $k=4$

. Let

$k=4$

. Let

![]() $A= [0,2] \cup \{b\}$

. If

$A= [0,2] \cup \{b\}$

. If

![]() $b> 2h$

, then

$b> 2h$

, then

If

![]() $i_0 \in [0,h-2]$

and

$i_0 \in [0,h-2]$

and

![]() $r \in [0,1]$

, then

$r \in [0,1]$

, then

Conversely, if

![]() $b \in [3, 2h]$

, then there exist unique integers

$b \in [3, 2h]$

, then there exist unique integers

![]() $i_0 \in [0,h-2]$

and

$i_0 \in [0,h-2]$

and

![]() ${r \in [0,1]}$

such that

${r \in [0,1]}$

such that

Setting

![]() $A = [0,2] \cup \{b\}$

, we obtain

$A = [0,2] \cup \{b\}$

, we obtain

This completes the proof.

Corollary 6 For all

![]() $h \geq 2$

and

$h \geq 2$

and

![]() $k \geq 3$

,

$k \geq 3$

,

Proof Applying Corollary 4 with

![]() $i_0 = h-2$

and

$i_0 = h-2$

and

![]() $r = k-4$

, we obtain

$r = k-4$

, we obtain

![]() $b=k$

,

$b=k$

,

![]() $A = [0,k-2]\cup \{k\}$

, and

$A = [0,k-2]\cup \{k\}$

, and

![]() $|hA| = hk$

. This completes the proof.

$|hA| = hk$

. This completes the proof.

Corollary 7 Let

![]() $h \geq 2$

and

$h \geq 2$

and

![]() $k \geq 3$

. For all

$k \geq 3$

. For all

![]() $i_0 \in [0,h-2]$

, the sumset size set

$i_0 \in [0,h-2]$

, the sumset size set

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

contains the arithmetic progression

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

contains the arithmetic progression

for

![]() $b \in [ (h-i_0)(k-2) - (k-3), (h-i_0)(k-2)]$

.

$b \in [ (h-i_0)(k-2) - (k-3), (h-i_0)(k-2)]$

.

In particular,

![]() $ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

contains the integer interval

$ \mathcal R_{\mathbf Z}(h,k)$

contains the integer interval

$$\begin{align*}\left[ \frac{ h^2 (k - 2)}{2} + \frac{hk}{2} - k + 3 , \frac{ h^2 (k - 2)}{2} + \frac{hk}{2} \right]. \end{align*}$$

$$\begin{align*}\left[ \frac{ h^2 (k - 2)}{2} + \frac{hk}{2} - k + 3 , \frac{ h^2 (k - 2)}{2} + \frac{hk}{2} \right]. \end{align*}$$

Proof This follows directly from Corollary 4.

For related work on sumset sizes, see [Reference Fox, Kravitz and Zhang2, Reference Hegyvári5, Reference Kravitz6, Reference Nathanson10, Reference O’Bryant12, Reference Péringuey and de Roton13].