Introduction and context

This research project seeks to examine, using approaches drawn from a case study, how oral storytelling within the classroom can influence various aspects of narrative writing. Therefore, certain teaching strategies and oral activities were implemented in a sequence of lessons which aimed to develop the style and content base of students’ narrative writing.

I decided to undertake my research in this area of teaching as it reflects my awareness of the integral place of speaking and listening within an educational classroom context. This recognition of the importance of the spoken word and talk for learning has stemmed from my previous assignments and readings from researchers such as Robin Alexander (Reference Alexander2008) and Jerome Bruner (Reference Bruner1983). Moreover, my interest in oracy and the more specific form of oral storytelling was instigated when studying Classics at university: the exploration of Ancient Greek oral culture and Ciceronian literature demonstrated the fundamental place of oracy to empower and educate. Therefore, I am interested to examine how oral storytelling as an educational medium can be an advantageous tool to develop narrative writing.

This research was collected in my second Professional Placement school which is a 11–18 mixed, comprehensive (non-selective) school located in Cambridgeshire. The student demographic is multi-cultural and there is a high percentage of English as an Additional Language (EAL) learners with a range of language competencies. The particular Year 8 class that I worked with for this project is a group of 30 students who reflect this diversity, as a third of the class are on the EAL register. The class is an academically high-achieving top set, and therefore have a high attainment range of 6B-7A, apart from one student who has been placed in the class for behavioural reasons whose attainment grade is a 5C. The majority of the students in the class are extremely vocal during whole-class questioning and group or pair work and are able to concentrate and work effectively through a prolonged writing task. There are a few individuals who are less vocal and struggle to start and sustain writing tasks, but brief encouragement or intervention normally prompts their verbal or written work.

I began to teach the class full-time when they began the War with Troy (WWT) unit at the end of January. This unit is part of a bigger scheme called the Iliad Project, set up by the Cambridge School Classics Project (CSCP) in 2000, which aims to ‘introduce pupils to the world of the ancient Greeks and to develop literacy skills, particularly speaking and listening’ (Reedy & Lister, Reference Reedy and Lister2007). This unit therefore lent itself noticeably well to the research I was keen to undertake.

My research methods are drawn from a case study, and I have collected data from a whole class through questionnaires, as well as through in-depth analysis coding of five students’ written work. The case study participants I selected for the in-depth scrutiny of written work were aimed to span a range of abilities and personalities within the classroom for a greater comparison of validity to a larger sample.

Literature Review

Oracy as a tool for learning and life

Wilkinson (Reference Wilkinson1965) introduces the term ‘oracy’ as an encompassment of both the oral skills of speaking and listening (p.14). This skill-set has been argued by numerous scholars to be an essential part of education, and many have attempted to give spoken language comparable status to reading and writing (Reedy & Lister, Reference Reedy and Lister2007; Mercer & Littleton Reference Mercer and Littleton2013; Mercer et al., Reference Mercer2016; Hibbin, Reference Hibbin2016a). For instance, Alexander (Reference Alexander2008) argues that talk is a twofold necessity within learning and life:

Students need, for both learning and life, not only to be able to provide relevant and focused answers but also to learn how to pose their own questions and how to use talk to narrate, explain, speculate, imagine, hypothesise, explore, evaluate, discuss, argue, reason and justify. (Alexander, Reference Alexander2008, p.4)

This crucial role of talk is supported by theorists such as Vygotsky (Reference Vygotsky1962) who maintain that talk is integral to a child's social development, as it is through this that children develop their vocabularies, make sense of the external world and become active learners. Moreover, Bruner (Reference Bruner1983) argues that adults can provide a framework for children's learning, as ‘through ritualised dialogue and constraints and through questioning and feedback to the child, the adult prepares the cognitive base on which language is acquired’ (McDonagh & McDonagh, Reference McDonagh, McDonagh, Marsh and Hallet2008, p.1). Mercer and Littleton explore how spoken language enables an ability to ‘interthink’: for people to think creatively and productively together (Mercer & Littleton, Reference Mercer and Littleton2013, p.1).

In recent years, this emphasis on the importance of talk has been highlighted by researchers in developmental psychology, linguistics and education for its stimulation of children's cognitive development, and its use as both a cognitive and social tool for learning and social engagement (Mercer et al., Reference Mercer2016). In Alexander's Dialogic Teaching he argues that talk is the foundation of learning and consequently has ‘always been one of the essential tools of teaching’ (2014, p.9). Therefore, classroom talk and oral activities are essential to empower pupils both as thinkers and active agents in their own learning. There is now a significant amount of robust evidence which confirms that good-quality classroom talk improves standards of education across all core subjects (Alexander, Reference Alexander2012).

Talk is also crucial as a means to prepare children for the communicative skills of adult life, which is part of the ‘adults need’ view on the Cox Report (1989) of teaching English. Researchers examining the functional component of English found that employers regarded ‘speaking clearly in different contexts’ as one of the most important skills for students to learn before entering employment (Child et al., Reference Child, Johnson, Mehta and Charles2015, p.156). Furthermore, a dialogic classroom can extend much further than just between teacher and child or child and child: it is also between individual and society. Discussion and talk within the classroom is the means by which we develop students who will engage and participate within a democratic society (Alexander, Reference Alexander2010; Mercer et al., Reference Mercer2016). Lastly, studies have also started to show that there is a strong relationship between oral competence and social acceptance and status, meaning that the development of oracy could influence students’ future social mobility (Mercer et al., Reference Mercer2016; Hibbin, Reference Hibbin2016b).

Oracy within the British National Curriculum

In the 1960s, a growing awareness of the importance of speaking and listening, through the influence of researchers such as Wilkinson (Reference Wilkinson1965) and Vygotsky (Reference Vygotsky1962), meant that it was ‘gradually afforded greater status and made a compulsory part of the assessment of English in the General Certificate of Secondary Education’ (Cliff-Hodges, Reference Cliff-Hodges, Davison, Dowson, Davison and Dowson2014, p.49). However, since then many National Curriculum reforms have taken a ‘backwards step’ (ibid.) in the eyes of many teachers, as suggested changes have included narrowing the view of spoken language and then once again the processes of language interaction (ibid.).

For example, Smith and Foley (Reference Smith and Foley2015) argue that the presence of Speaking and Listening in the new 2014 Key Stage 3 and 4 curricula has ‘devalued speaking and listening at GCSE’, and the change in terminology from Speaking and Listening to spoken language ‘seems to ignore the “listening” element altogether’ (Smith & Foley, Reference Smith and Foley2015, p.61). Presently, spoken language does not contribute to the result of the GCSE English Language qualification, but instead is a separate endorsement limited only to presentations (Ofqual, 2013). The reasoning behind these changes has been attributed to the difficulties of ensuring ‘fair outcomes for students overall’ (ibid.). The issues and hesitancies surrounding oracy which are preventing a reinstatement of a bigger weighting within the curriculum stem from its transient nature – unless recorded – and challenges for teachers to teach it effectively and to assess it pragmatically, reliably and equitably (Mercer et al., Reference Mercer2016). However, these problematic areas are being tackled by researchers – the Cambridge Oracy Assessment Project has produced ‘an Assessment Toolkit that combined research-based validity with a practical ease of use for teachers’ (Mercer et al., Reference Mercer2016, p.1) – and many continue to debate for its reinstatement within the curriculum (Mercer et al., 2014; Alexander, Reference Alexander2008).

Defining oral storytelling and its rationale within the classroom

The National Council of Teachers of English have defined oral storytelling as ‘relating a tale to one or more listeners through voice and gesture’ (1992). This definition emphasises the need for a listening audience, the importance of paralinguistic features alongside the spoken word, and the implicit denial of a script. When I refer to oral storytelling as a medium within the classroom, I am referring to the processes included in the roles of students as oral performers as well as attentive listeners.

Hibbin contends that oral storytelling is the oldest form of education and has been the medium used from time immemorial to pass down beliefs, traditions and history. Based upon this claim she argues that the process and activity is our ‘innate predisposition’ and that ‘we are literally hard wired for story’ (Hibbin, Reference Hibbin2016a, p.53). Similarly Cox claims ‘children construct the world through story’ (Cox, Reference Cox1989, p.94). Moreover, Brice Heath (Reference Heath1983) has demonstrated, through various research and case studies, that the very nature of language development establishes oracy's inextricable link to literacy practices, indicative of its integral place in the classroom.

As a form of speaking and listening, oral storytelling is also currently a learning tool that has little status or visibility in school, especially within secondary education ( Smith & Foley, Reference Smith and Foley2015; Hibbin, Reference Hibbin2016a). Smith and Foley agree that ‘it appears the idea of storytelling is seen as an unnecessary luxury in today's assessment-driven culture’ (Smith & Foley, Reference Smith and Foley2015, p.63). However, efforts have been made to challenge these views within the English classroom and to reassert and ‘promote speaking and listening and storytelling… to reclaim and champion oracy and story as an element of English teachers’ principled practice’ (ibid).

Oral Storytelling as a tool for learning and writing

Many researchers have made strong cases for how different types of talk can support learning within a classroom setting for all ages. This specific section will analyse the research that has examined the range of learning benefits from oral storytelling with a specific emphasis on writing.

One of these research ventures into oral storytelling within the classroom has been the Iliad Project, set up by Cambridge School Classics Project in 2000. This comprises an oral resource (three-set CD and online), called War with Troy, via two professional storytellers who created their own version of the story of the Trojan War. It was devised with the aims of developing pupils’ speaking and listening skills, whilst also keeping alive the Classics and promoting the study of the Iliad within the classroom (Lister, Reference Lister2007). The findings from this project were recorded from an extensive research project which took place in six primary schools in London with classes of 9–11 year-old pupils. The first finding was the way the project engaged students through its oral nature: ‘listening to the story had enabled them to imagine (literally) both characters and scenes in great detail’ (Reedy & Lister, Reference Reedy and Lister2007, p.4). Inclusion within the classroom was also a key finding: as the resource implicitly prioritises aural, rather than reading, skills, and the initial response to the recordings was always oral discussion; participation was placed ‘on a level footing’ as all students, irrespective of their reading abilities, could and wanted to contribute in the discussions and dialogue surrounding the oral resource (Reedy & Lister, Reference Reedy and Lister2007, p.5). Therefore, the speaking and listening benefits gained from these activities included pupils’ increased quality of discussion, sustained concentration and confidence to express views with specific supporting evidence. However, the benefits were not only in improving students’ speaking and listening skills but also in their enthusiasm for other modes of literacy. The oral text provided a stimulus for students to write and encouraged reluctant readers to explore printed texts. Moreover, as students found they could contribute significantly to this story orally, ‘it in turn gave them the confidence to engage with reading and writing often unprompted’ (Reedy & Lister, Reference Reedy and Lister2007, p.5). The findings from this project make a convincing case through interviews with teachers and pupils to show how both aural and oral activities can be successful in the classroom to improve learning in a range of areas. However, as the research was primary school-based, these findings cannot be reliably generalised to students in my secondary school case study.

In 2012, the CSCP extended its work to encompass the KS3 English classrooms and two studies were conducted with trainee teachers: 1) 28 trainees explored activities where they themselves performed as storytellers; 2) 202 trainees completed questionnaires about storytelling; 3) 60 trainees attended a day's workshop on classic storytelling. The results from these research projects were trainees’ reflections on oral storytelling as a resource for ‘deep learning’, its ‘potential as a communal practice’, as an ‘inclusive practice’, as a means to ‘develop oracy in meaningful ways’ (Smith & Foley, Reference Smith and Foley2015, pp. 67–69). Smith and Foley make strong claims for the importance of good oral work as a learning tool and thus oral storytelling's potential as an effective pedagogic tool. However, the final claim that ‘oral storytelling by both teacher and learner promotes a rich collective experience’ (Smith & Foley, Reference Smith and Foley2015 pp. 67–69) is arguably unsubstantiated due to a lack of in-school and thus learner evidence.

Another interesting piece of research that aimed to bring oral storytelling into the classroom, as well as similarly challenging the curriculum's set of canonised texts handed down from teacher to student, was conducted by Nikki Railton (Reference Railton2015). In her case study, she used oral storytelling as a medium for her class to explore and share their own culture and oral traditions within the classroom, as well as becoming oral storytellers themselves. Railton drew upon Brice Heath's work to validate her research: oral storytelling has pronounced advantages for writing, helping children employ the exact skills her students struggled with e.g. structure; using varied punctuation; using varied sentence structure etc. The class was a Year 10, low-attaining group with a mixture of EAL (English as an Additional Language) and SEN (Special Educational Needs) students. They were asked to prepare a story from their oral cultural heritage and these stories were then told to the rest of the class in a circle formation. The findings from this case study were wide-ranging and had a variety of results for different students. Railton maintained that students obtained valuable knowledge about culture and the oral tradition, which demonstrated that an understanding of the world can be acquired in different ways – one of these being through a shared social experience – not only through the more restrictive texts and methodologies that the curriculum encompasses. However, the research lends itself well to theories explored by Alexander (Reference Alexander2008) through its ideology of students and teachers discovering and learning together the importance of connecting home and school: ‘An absorbing interest in students’ cultural heritages… should form the very foundation of our teaching’ (Railton, 2016, p.58).

Barrs and Cork (Reference Barrs and Cork2001) researched the links between literature and writing development in a Year 5 classroom, and found that skilful reading aloud within the classroom improved students’ writing. Indicators in this study included the ability to ‘maintain the narrative voice and viewpoint that they were adopting in the piece of writing’, an ability to imagine their invented worlds more vividly, a heightened sense of reader needs: using writing ‘to tell stories for a listener or reader’ (pp. 200–202) and children's ability to draw on a literary source through the echoes within their own writing. Moreover, they found that traditional tales, many which have an oral basis, ‘have a particularly important role to play in children's narrative education, providing a bridge from oracy to literacy for young children’ (Barrs & Cork, Reference Barrs and Cork2001, p.215). This is because these texts have strong narrative structures, which are easy for students to remember and thus they can use similar patterns in their own writing. However, Barrs and Cork were convinced that the texts really had the impact because they were brought to life through skilful reading aloud. They emphasise that the more these stories are told to children, the more they see how a story is built up, which is in turn the power that ‘help[s] children as writers’ (Barrs & Cork, Reference Barrs and Cork2001, p.216). These processes have similarities to the aural relay of stories in the CSCP, and also demonstrate how students’ own narrative structure and content can be developed through patterns and features within traditional tales.

Similarly, Heath (Reference Heath1983) studied children's language development at home and at school in two disparate communities in the eastern USA. She examined the connection between types of literacy: ‘The modes of speaking, listening and writing are tightly interrelated as children learn…’ (p.256). She found that oral storytelling has pronounced advantages for writing within school in terms of clarity in narrative structure; placing emphasis and meaning; using varied punctuation, vocabulary and sentence structure.

Oral Storytelling in its own right

Hibbin argues that ‘oral and written forms interrelate and spoken language provides children with the building blocks they require to master reading and writing’ (Hibbin, Reference Hibbin2016a, p.55), and this can also be glimpsed through the research of Heath, Lister and Railton above. The National Curriculum also endorses the advantage of using spoken language to develop reading and writing: ‘Spoken language continues to underpin the development of pupils’ reading and writing during key stage 3 and teachers should therefore ensure pupils’ confidence and competence in this area continue to develop’ (DfE, 2013).

In my project, I am exploring how the oral form of storytelling can be used to develop narrative writing in a constructive and educationally useful way. However, it is important to acknowledge that the frequent practice of oracy as a precursor to written work has been criticised by many educational researchers. Hibbin argues that there is a legitimate concern that in attaching literacy-based outcomes to oral work in school ‘may alter the very nature and the qualitative experience of the oral event’ (2016a, p.61), i.e. if children write down their ideas down before speaking them, their focus may be on memorisation rather than spoken delivery. Moreover, if reading and writing are seen as more senior in relation to orality, ‘the degree to which pupils are likely to engage with oral work on a serious and sustained basis becomes questionable’ (Hibbin, Reference Hibbin2016a, p.56). Thus, though there is considerable value in attaching oral work to written outcomes, oracy should also be unattached to literacy-based outcomes so it can be assessed properly in its own right, and not simply a foundation for the other ‘more important’ forms of literacy (Alexander, 2006; Reedy & Lister Reference Reedy and Lister2007; Mercer et al., Reference Mercer2016).

Defining narrative writing

In The Cambridge Introduction to Narrative Porter Abbott (Reference Porter Abbott2008) seeks to explore the concept of ‘narrative’ within the Arts and through the ordinary course of people's lives. Simply put, narrative can be defined as ‘the representation of an event or a series of events’, which allows clear distinctions between other forms of writing such as a ‘description’ or an ‘argument’ (p.13). This can be broken down further by the narrative, story and narrative discourse: ‘narrative is the representation of events, consisting of story and narrative discourse; story is an event or sequence of events (the action); and narrative discourse is those events as represented’ (p.19). Moreover, Bruner, in his theoretical examination of the mind and human acts of imagination, considers that narrative content ‘deals in human or human-like intention and action and the vicissitudes and consequences that mark their course’ (1986, p.13). This involves a subject matter of organised structures that depict the world of human experience and meaning. Similarly, Porter Abbott (Reference Porter Abbott2008) discusses the importance of the characters or entities involved in narratives – ‘What are events but the actions or reactions of entities?’ (Porter Abbott, Reference Porter Abbott2008, p.19). However, the language of the discourse, as well as the plot and its structure, is also essential to convert narrative into powerful stories. This type of language included may be the language of evocation and ambiguity, thus dealing with figurative techniques and devices (Bruner, Reference Bruner1986, p.24). The narrative must also give an indication to a listener or reader in order to ‘recruit the reader's imagination’ and make it ‘possible for the reader to “write” his own text’ (Bruner, Reference Bruner1986, p.25). Metaphors are one way in which a writer can create implicit or open discourse to harness an implicit vision for the reader.

Research Questions

The overall title I aimed to explore is:

‘A critical investigation, using approaches drawn from a case study, into how Year 8 students’ narrative writing skills are developed through the learning medium of oral storytelling.’

In order to focus my research, I chose three specific research questions to focus my data analysis around:

Research Question 1: To what extent can Year 8 students’ narrative writing be supported through the use of oral storytelling activities?

Research Question 2: What are Year 8 students’ perceptions of how oral storytelling activities have influenced their narrative writing?

Research Question 3: What are Year 8 students’ perceptions of writing an oral story that is familiar and/or personal to them?

Teaching Sequence

War with Troy within the classroom

The War with Troy resources comprises 12 audio clips and accompanying teacher's guide. In these audios, Daniel Morden and Hugh Lupton, two of Britain's leading professional storytellers, retell Homer's Iliad for a modern audience, whilst the guide offers complementary teaching ideas and activities to explore the oral resources.

In nearly every lesson of this teaching sequence, students would listen to one of these audio clips. The students collectively decided beforehand, that during these audios they would like the classroom lights off and the choice of closing their eyes to enhance their listening. They would then subsequently investigate and analyse the oral content through a variety of writing, reading, drama and speaking and listening tasks. For instance, students would orally recap the audio using question prompts and then analyse the content in terms of the plot, characterisations and language, as well as the oral features in which this part of the story was expressed (tone, pace, emphases etc.).

Lesson one

I was influenced by the article by Railton (Reference Railton2015), and the ideology behind using students to bring their own stories or ancestral experiences into the classroom as learning resources. Therefore, in a similar method, I asked students to prepare an oral story for the next lesson. The specific brief was that students find a story that had been told to them orally, and that they knew very well: this could be a cultural or religious story or fable.

For this lesson, the classroom was rearranged, and the students and myself sat in a circle of chairs. Expectations of respect and learning were laid out beforehand, and the role of the listener was emphasised. Students then told their stories to the rest of the class one by one, whilst their peers listened.

Lesson two

In this lesson, various oral activities were aimed at different aspects of oral storytelling. At the end of every activity that was carried out, students discussed why they thought the task was relevant to being an oral storyteller, and committed to practise incorporating this into their own oral storytelling performance.

The first activity was about description and painting a vivid picture. Students were placed in groups of four, and one person in this group was given a picture which they were told to hide from the rest of the members in their group. They had five minutes in which to describe the picture as carefully as they could, whilst the other members of the group had to draw what was being said on a piece of paper. The aim was to get their drawings as close as possible to the real picture, through carefully spoken description, the inclusion of figurative language techniques and attentive listening.

The second activity was aimed at the variation of sentence lengths in order to build suspense and tension. In their groups, students were given a starting sentence and then took turns in adding extra short/long/a mixture of sentences. They then each had to say the effect this had on the oral story they had produced.

The third activity was about being an oral storyteller that was engaging, believable and persuasive. The students had to use their words in order to convince their partner of something that lay within a box displayed on the desk.

Similar tasks were carried out demonstrating repetition, structure and action.

Lesson three

Students were given one lesson in which to plan and structure their oral stories before their subsequent performance and assessment. At the start, a ‘success criterion’ was devised as a whole class activity: students were asked to recall and examine what content and delivery tools the oral storytellers from the WWT audios employed in order to make their performances engaging to their intended audience. The success criterion for content included figurative language, short sentences, repetition, stock phrases (i.e. ‘imagine’) and epithets. Students also argued that the story needed to include descriptive language to illustrate setting and characterisation. The success criterion for the delivery of the performance included that the speaker was to: speak loudly and clearly, use hand gestures, maintain eye contact and vary the speed and tone.

Students were given cue cards on which they were allowed to write six bullet points to demonstrate a clear structure to their story and to act as memory prompts during the performance.

Lesson four

Students performed their orally prepared stories one by one to the rest of the class, and were assessed on these, using KS3 speaking and listening ‘talking to others.’

Students were prompted to harness language devices present in the WWT storytelling audios and explored through activities in the previous lesson – for example: figurative language, stock phrases such as ‘imagine’, repetition – in order to make their performances as vivid and engaging as possible.

Lesson five

Students were given 30 minutes at the start of the lesson to create a written version of the oral story that they had performed – no other guidelines were given. Students subsequently completed a questionnaire on their experiences of these oral storytelling activities and perceptions on their writing.

Methodology

The methodology I chose for my assignment was focused on a case study because I was interested in exploring a specific topic in-depth with a spotlight on a few particular phenomena (Denscombe, Reference Denscombe2014). The case was limited to four research lessons, and therefore a ‘fairly self-contained entity’ with ‘distinct boundaries’ (Denscombe Reference Denscombe2014, p.74). The sample size was small and my rationale was to focus on specific instances within a natural setting to gain deeper insight and discovery. Therefore, as a case study ‘offers the opportunity to go into sufficient detail to unravel the complexities of a given situation’ (Denscombe, Reference Denscombe2014, p.75), this seemed like an appropriate method.

Research methods

Pupil product: written work

To gain an insight into how oral activities may influence narrative writing, it was evident that an analysis of students’ written work must be undertaken. As I had chosen a case study methodology, I wanted to focus on specific instances with this research method in order to gain an in-depth insight. Therefore, though all students took part in the writing activities, I only analysed the work of one-sixth of the students in detail which worked out as five students. I picked the students I wanted to focus on beforehand, as I was keen to select a range of students in terms of ability, gender and whether they had English as an additional language or not.

There are a number of limitations when attempting to interpret learners’ productions, as the things that students write only provide indirect evidence of how far (if at all) their understanding and learning have developed (Taber, Reference Taber2007). Especially when analysing a limited number of students’ work, it is likely to reflect only ‘a facet of a repertoire of available ways of thinking’ (Taber, Reference Taber2007, p.146), and it is difficult to know if any learning is a development or pre-existing. Therefore, it is very important to recognise that this type of data should be seen as ‘one “slice of data” to be triangulated against other informative data sources’ (Taber, Reference Taber2007, p.147).

Moreover, when doing a comparative study of written work, there is always a risk of subjectivity and precision when ascertaining data from these. Therefore, I decided to use a coding method to identify any patterns in the piece of narrative writing and to reduce the subjectivity of my data and to allow the collection of precise quantitative data.

Questionnaires

As my second and third research questions aimed to discover students’ perceptions of the impact of oral storytelling activities on their narrative writing, it was essential to collect data which would indicate student opinions. This questionnaire was distributed to students straight after their second narrative writing piece was completed in an attempt to gauge information on their opinions of the process of the task, and how oral activities affected it, whilst it was still fresh in their minds.

Data presentation, analysis and evaluation

Research Question 1: To what extent can Year 8 students’ narrative writing be influenced through oral storytelling?

As I chose case study methodology, I decided to select five students’ written work to analyse in order to get a more detailed, in-depth study. To attempt to study the influence of oral storytelling, this data analysis aimed to discover if there were any echoes of features from oral activities and stories in students’ written work. Due to the issues of validity and subjectivity surrounding the use of data collection from student work, I decided to analyse the students’ writing using a coding system which focused on specific features of oral practice to obtain more precise data.

The oral features that were explored by students in oral storytelling activities – both orally and aurally – that I decided to focus upon were:

– Initial detailed description - over two sentences describing the setting at the start of the writing

– A series of short sentences - two or more short sentences of five words or less

– Repetition -the same word repeated more than once within a paragraph – excluding articles and prepositions.

– Epic similes - an ‘extended simile’: over five words including ‘like’/‘as’

– Epithets - an adjective or phrase expressing a quality or attribute regarded as characteristic of the person or thing mentioned.

I used these to distinguish the presence or absence of these features in students’ narrative writing to demonstrate the students’ ability within their narrative to ‘recruit the reader's imagination’ (Bruner, Reference Bruner1986, p.25) and paint a vivid story. The stories which the students orally explored and performed were wide-ranging: Student A – ‘The three little pigs’; Student B – ‘The birth of Ganesh’; Student C – ‘Jack and the Beanstalk’; Student D – ‘Rapunzel’; Student E – ‘Adam and Eve’.

Initial detailed description

The first oral activity completed by students was aimed at exploring vivid description to paint a picture for their listeners. Therefore, I wanted to see if detailed descriptions, especially in relation to setting and character, were evident in their writing.

Four out of the five students started their story with the word ‘imagine’ and followed this with a detailed description of the setting in a similar form to oral practice. For example:

Student E: ‘Imagine a garden, where plants grew wild, where rivers flow free, where animals were ragged’;

Student B: ‘Imagine a snow-peaked mountain…’;

Student C: ‘Imagine an old and tiny cottage beside a dazzling lake…’: and

Student D: ‘Imagine glowing, golden, glamorous hair!’

The descriptive language from these students was extended, and varied in length from about three to five sentences long before moving forward with the plot. Student A did not include detailed description, but instead dived straight into the action of what the three little pigs did.

This verb ‘imagine’ is a clear reflection of the audio from War With Troy, and was present in the oral performances of many students. Moreover, the inclusion of the initial description in the work of the students suggests that students are also incorporating features of their oracy practice into their writing.

Short sentences

The second oral activity completed by students was aimed at the use of successive, short sentences for tension, suspense and other effects.

Student B, alone, was the only student to incorporate this orally practised skill into his written work: ‘Along came Shiva. Ganesh would not let him in. Shiva was furious. He banged on the door.’

Repetition

Repetition was also an area that was focused orally within the classroom. Four out of five students utilised this device in their writing to emphasise different aspects such as grief, the influence of God and the length of a path:

Student A: ‘He blew and blew and blew’;

Student B: ‘She cried and she cried and she cried’;

Student E: ‘Created by God, kept by God, loved by God’; and

Student C: ‘He began to walk down and down and down the winding and twisting, muddy pathway.’

The extracts from Students A, B, C and E appear to structurally echo examples of repetition sentences from War With Troy – e.g. ‘gold upon gold upon gold’, ‘she wept and she wept and she wept’.

Epic similes

Epic similes were a device frequently used in the audio of War With Troy, and in the oral storytelling activities within the classroom. Similes and metaphors are devices that have a considerable focus in the English classroom from KS2, whereas epic similes are a classic device of oral storytelling.

All five students included this definition of extended similes in their writing:

Student A: ‘Like a terrifying hurricane that twisted and turned’;

Student B: ‘Like a small child screaming and crying for its mother to come home’;

Student C: ‘A dazzling lake which glinted like the stars in the sky as the sun shone upon it’;

Student D: ‘Bright blue eyes as blue as a sapphire gem sparkling under a spotlight’; and

Student E: ‘Like a kaleidoscope so random and purposeful with shapes and colours everywhere.’

Epithets

The final feature of oral storytelling that I looked at in the students’ writing was an attachment of an epithet to a main character. These are drawn upon greatly in War With Troy - e.g. Zeus the Cloud-Compeller, or Voluptuous Aphrodite – and many oral activities within the class have focused on these. However, this oral device was only utilised once by Student A in the written narrative: The big bad wolf.

Evaluative comments

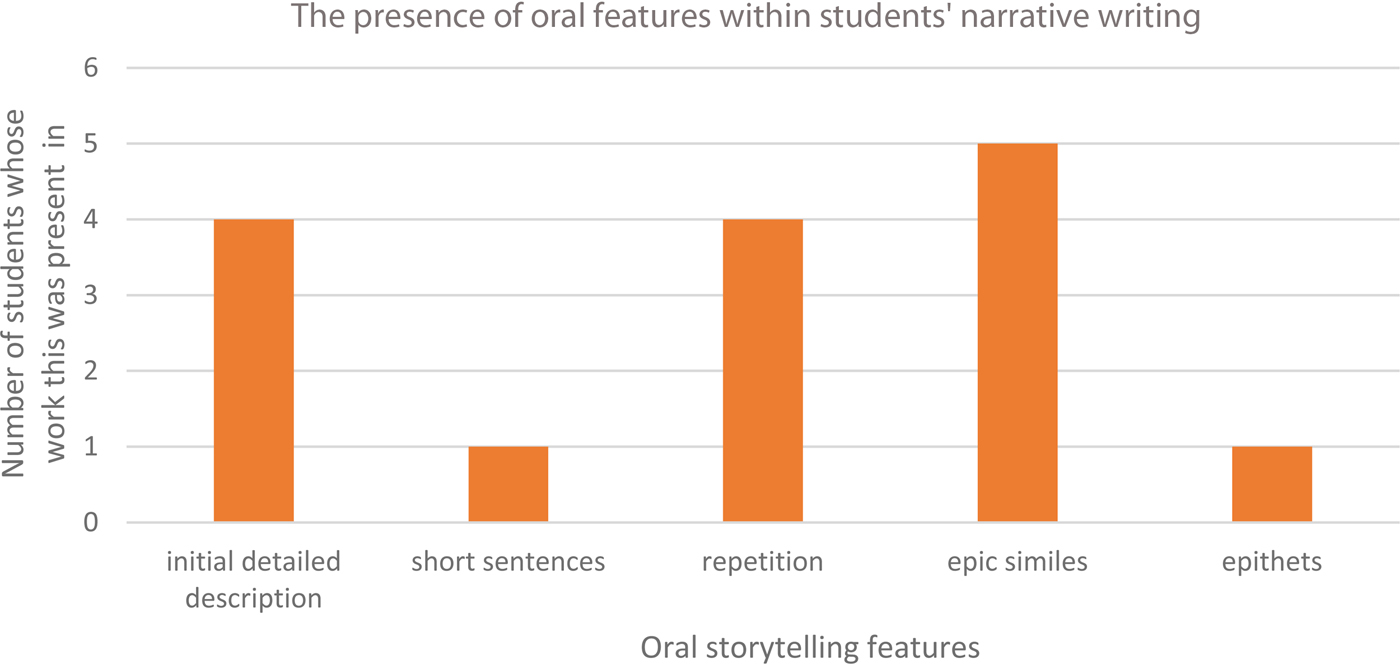

The frequency of students using these oral features within their writing is illustrated in the table below (Figure 1). This demonstrates that there is a pattern showing that many features of oral storytelling were present in the students’ written work. This is a finding similar to research by Heath (Reference Heath1983) and Barrs and Cork (Reference Barrs and Cork2001), who also found echoes from oral stories within the students’ writing. The use of epic similes, initial detailed description and repetition were evident in the majority of students’ work, whilst short sentences and epithets were only used by one student.

Figure 1. | The presence of oral features within students’ narrative writing.

One possible reason for the discrepancy between the frequency of these devices is that the use of short sentences and epithets may be harder skills for students to understand and feel confident to use within their work. On the other hand, students may equally have gathered the skill-set from these oral activities, but for this particular task decided not to use them within their story (Taber, Reference Taber2007). It is also difficult to verify whether the short sentences used in Student B's narrative were the intentional use of a device for effect or an accidental feature. Similarly, the use of the epithet in Student A's narrative is arguably an existing feature of the traditional tale chosen to retell, rather than a development of oral storytelling features. As I am basing my analysis on only one pupil product, I am unable to see whether a stronger pattern may emerge if I were to examine students’ work over a longer period of time. Moreover, my coding process was limited to only five oral storytelling features, which do not definitively demonstrate all the influences and benefits that oral storytelling could have on writing. It is also difficult to distinguish whether the appearance of these features in students’ writing is due to oral storytelling activities and the influence of War with Troy or the result of other influential variables (Denscombe, Reference Denscombe2014). For example, students may have added these devices into their narrative writing because they were influenced by a book they were reading, or by a creative writing lunchtime class that they attend. Or indeed whether their learning was developmental or pre-existing (Taber, Reference Taber2007). Moreover, due to the small sample size, and disparity of the results, it is difficult to reliably generalise these findings to the rest of the class narrative writing.

Research Question 2: What are Year 8 students’ perceptions on how oral storytelling activities have influenced their narrative writing?

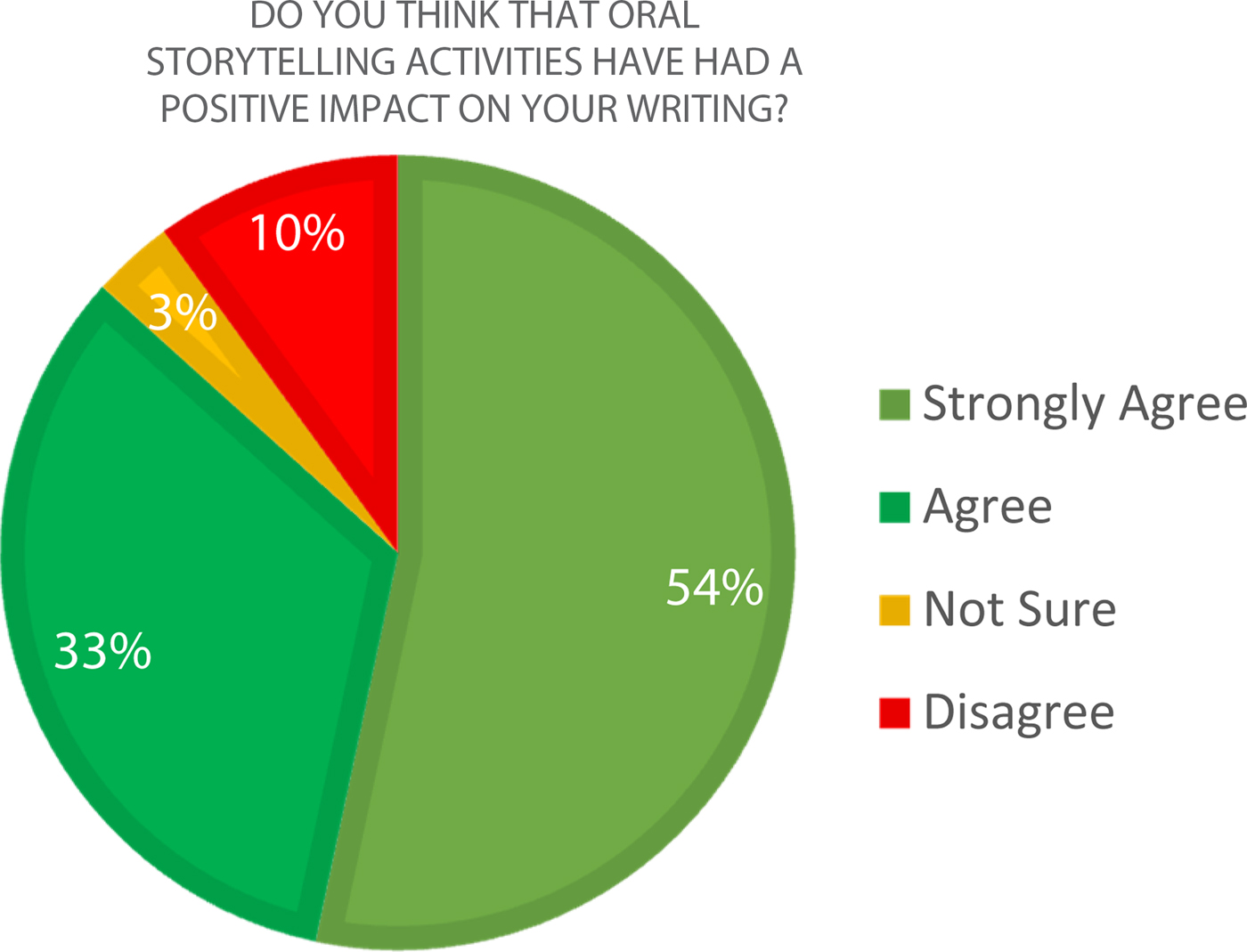

The data from the questionnaires and interviews were used to explore my second and third questions. The first question that was asked in my questionnaire was ‘Do you think that oral storytelling activities have had a positive impact on your writing?’. The oral storytelling activities were defined under this question to remind students of the previous lesson. Students here had the option of selecting a box ranking from - 5 Strongly agree, 4 Agree, 3 Not Sure, 2 Disagree, 1 Strongly disagree - to give students a range of options, rather than a simple Yes / No selection. From this question, there was an overwhelmingly positive result as 26 students selected either Strongly agree or Agree. Only one student selected 3 Not sure and three selected 2 Disagree (See Figure 2 above).

Figure 2. | Pie Chart showing students’ positive responses towards the impact of storytelling activities on their writing.

In order to gauge a richer response and reasoning for their selection, I opted for a following ‘open’ question to ask for an initial answer. This allowed students to freely state their opinions, without prompts, as closed questions can have the potential to ‘lead’ students’ answers, or restrict them. Many students listed multiple answers and explanations which are listed in the table below (Table 1):

Table 1. | ‘Do you think that oral storytelling activities have had a positive impact on your writing?’

The majority of the students noted that they were able to draw upon techniques and devices, such as repetition, figurative language, varied sentence lengths, that they had practised orally and reflected this in their writing. This finding is similar to that of Heath's (Reference Heath1983), who found that oracy improved these skills in the writing of the students she studied. Many students noted the effect of these particular devices such as: ‘It is more suspenseful’, ‘Things are made more emotional and believable’, ‘The time goes faster’. By listening to oral stories, as well as utilising these devices in their own speech, students may appreciate the relevance and effect of these devices on their audience more.

An increased confidence with writing was the second most frequent explanation that students gave in answer to question 2. This is a finding synonymous with Reedy & Lister's (Reference Reedy and Lister2007) research into oral storytelling within the classroom, as they also found that oral contributions allowed students to engage with writing unprompted. This perception of improved confidence in writing can also be supported by my own observational notes within the classroom. Though the set are high-ability, when previously given writing tasks that have been drafted and planned prior to the task, they have concerns about whether they are doing the ‘right’ thing, and multiple individuals often need frequent reassurance. However, when asked to write a story they had verbally explored, practised and performed, not a single question was raised, and students diligently got on with their written task in silence. Of course, this observation may have been attributable to other factors, such as the clarity of my instructions, or because it was a lesson before lunch. However, this may also have been due to the students’ confidence and familiarity in their oral performance, helped by exploration and practice, which could in turn benefit their writing.

Another explanation that had a high occurrence was students’ reference to their ‘sense of a reader’, a finding similar to the research conducted by Barrs and Corks (2001) The Reader in the Writer. However, the interesting difference was that this finding was gleaned from data analysis of the students’ writing, whilst my data was from students themselves: ‘It has made me more aware about how I should engage the reader’; ‘It makes it more dramatic for the person reading it’; ‘I know how to make it interesting with short sentences so it is more interesting for the audience’; and ‘I am able to add more description to put a vivid picture in someone's head’. I had not expected this level of meta-awareness from students, which may have stemmed from the implicit nature of oral storytelling's speaker/listener format, and the oral activities carried out that have the listener at the centre the whole time. For example, the arrangement in Lesson 2 required students to face one another whilst telling their stories, which meant that the speaker had a very tangible audience to seek to engage. These students have thus consciously recognised their experiences as speaker and listener, and have proceeded to reflect this over to reader and writer.

Many students also explained that oral storytelling work encouraged more creativity and imagination which was then transferred to their narrative writing. Two extracts from students are: ‘I can imagine things a lot easier talking, so it is easier to write down’ and ‘It made me think about things differently and be creative in my writing’. These opinions are in line with Alexander's views on talk as an exploratory tool, which gives students more freedom to explore the ‘territory which it covers’, and to ‘imagine’ (Alexander, Reference Alexander2008, p.31).

Six students mentioned that the oral storytelling activities were useful as they were a way of sharing ideas; one student put it succinctly: ‘we could take ideas off other people and use them in our own stories’. The very nature of talk and thus any oral storytelling activities is the act of sharing and listening to the ideas of one's peers. Apart from peer feedback, students will rarely have an opportunity to hear stories created or manipulated by their own peers. This benefit of talk is also a key feature of a dialogic classroom when students ‘listen to each other, share ideas and consider alternative viewpoints… children build on their own and each other's ideas and chain them into coherent lines of thinking and enquiry’ (Alexander, Reference Alexander2008, p.28).

The other benefits that students recorded are also significant. They include ideas supported by relevant research, such as experimenting with vocabulary (Heath, Reference Heath1983) and being quicker to start the story (Reedy & Lister, 2014). If this investigation were carried out with a bigger sample size, there would be more value in going into further detail in these areas.

Lastly, the answers from Not Sure / Disagree are also noteworthy. One student commented that ‘It helped [my] speaking get better not my writing as much’, which corresponds to the arguments of Alexander (Reference Alexander2008), Mercer (2016) and Hibbin (Reference Hibbin2016a). They argue that oracy, or, as Hibbin argues specifically, ‘oral storytelling’ should act as tools to improve talk, rather than act as a precursor to reading and writing. Moreover, another student commented: ‘When I wrote, I wrote the story as if it was being spoken so some parts didn't make a lot of sense because I was used to drafting things I was going to say…’ This opinion furthers these views that oral storytelling and talk should be assessed as a separate entity itself, and that there is not always a need for it to be a foundation to other aspects of learning (Hibbin, 2016).

Evaluative comments

Many of the results collected through the questionnaire demonstrate that the majority of students agree that talk and oral storytelling are beneficial and enjoyable learning tools within the classroom. Moreover, the answers given by students, to varying extents, show levels of similarities to other research conducted in this area of education.

Research Question 3: What are Year 8 students’ perceptions of writing a story that is familiar and/or personal to them?

The third question that was asked in the questionnaire was: ‘Was there anything different about writing a story that you knew well and was familiar to you?’ This question yielded a range of answers in the Table 2 below:

Table 2. | ‘Was there anything different about writing a story that you knew well and was familiar to you?’

The majority of students found that the act of re-telling a familiar story was a different experience to other narrative writing tasks in class.

A large number of students commented on the ability it gave them to focus and incorporate particular language and literary devices, as they were less worried about the plot. For example, one student reported: ‘I found it easier because I knew the story and could focus more on the description and suspense than the story line’. Creativity was not limited at all, and many referenced how it gave them a sense of ownership over the story, e.g. ‘It makes you feel like it's your story and you can add/change things’, as well as the freedom to modify aspects: ‘I was able to tweak bits and make it my own’, and ‘put my own spin on it.’ This reflected their understanding of the fluidity of traditional and oral stories, as they perceived their malleable nature so they could harness stories for their own purposes and with their own creativity.

Evaluative comments

The results gathered here suggest that students have a perception on how writing a familiar oral story can have a range of benefits for their writing. Generally, students found that it allowed them a space or further ease in their writing to either include more language devices, manipulate the story for their own purpose or not get stuck on the plot. Though these perceptions are evidently positive, it is still difficult to assess and justify whether the students’ writing had actually developed as a result of this.

Concluding comments

My research into oral storytelling as a resource for narrative writing within the classroom has shown that there are potentially many positive outcomes when using it as a learning medium.

The analysis of the students’ work demonstrated that there were echoes of oral storytelling within the students’ written work. However, this research method was restricted due to its limited focus on only five oral devices, and small sample of students. Therefore, though a positive result was found, I am unable to draw satisfactory conclusions from it. It would have been more effective to additionally interview these five students to strengthen the validity of my results which would have resulted in a ‘triangulation approach’ of research methods. This is characterised by Cohen et al. as ‘a mixed-method approach to a problem in contrast to a single-method approach’ (Cohen et al., 1980, p.195), which can allow data to be collected from a variety of angles to increase perspective.

The results generated from the questionnaire demonstrate that students perceive oral storytelling as an enjoyable activity as well as an effective tool for their writing and other parts of their learning, such as improving their oral skills. Moreover, I discovered a wide range of student opinions, which make a convincing case for directing students to use a re-tell, a familiar story in their written work. As narrative writing does demand a wide skill-set, by allowing students to retell a familiar plot, it may allow them the space to focus on other skill-sets that may be limited due to its multi-faceted nature. This is not a method that should be employed always, but may have positive results if used occasionally within the classroom.

I have learnt through my literature review, as well as the results from my own case study approach, that oral storytelling within the classroom has the potential to influence students’ writing as well as other areas of learning that are yet to be explored. However, as my results only focused a small sample of students in one school in Cambridgeshire, it would beneficial to replicate similar research through a ‘triangulation approach’ with another cohort of students in a different school.

Appendix 1

Questionnaire

1. Do you think that oral storytelling activities have had a positive impact on your writing?

Please circle an answer below:

Strongly Agree/ Agree/ Not Sure/ Disagree/ Strongly disagree

2. Please give reasons for your answer to Question 1.

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

3. Was there anything different about writing a story that you knew well and was familiar to you?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………….

4. Do you have any other comments about oral storytelling or writing?

……………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………………..

Thank you for completing this questionnaire ☺