In the late 1930s, children living in three villages in central Nyasaland (contemporary Malawi) were subjected to a peculiar test devised by Dr. Benjamin Platt, a colonial nutrition scientist leading the Nyasaland Nutrition Survey. Platt provided a detailed account of how he constructed an apparatus that ‘could be used in the field [to test for vitamin A deficiency] without laboratory services and…with simple natives without causing alarm’.Footnote 1 He assembled this device from everyday materials on hand, including a five-pound tea-box, a piece of fabric, round discs cut from magazine advertisements, and sticking plaster. This tea-box assemblage was a modified version of the standard adaptometer ophthalmologists used to measure retinal cone cells’ adaptation to light, a marker of vitamin A sufficiency or deficiency.Footnote 2 Such tests are based on the fact that vitamin A is a critical factor in the cure of nutritional night-blindness. Platt recorded in meticulous step-by-step fashion how and from which materials he built this adaptometer (‘the main compartment is made out of a five pound tea box…with a sliding lid arranged so as to leave a variable aperture at the edge of the box…’), even specifying the measurements for each component (‘a series of small discs of 0.5 centimetres diameter, cut from the background of magazine advertisements and graded according to the amount of white surface showing from untouched paper to a dark grey appearance’). Platt noted that African test subjects were outfitted with the tea-box contraption after emerging from the interior of a dark ‘native hut;’ the researcher manipulated light exposure levels, using a stopwatch to record the time it took subjects’ eyes to adjust and accurately identify the number of discs pasted onto black paper inside the box. While Platt’s instructions help us conjure what the apparatus may have looked like, they are sterile and disembodied. They do not give any sense of the research encounter between scientist and participant, nor do they provide insight into how the test subjects interpreted or interacted with the tea-box creation.

Enclosing Africans in this tea-box contraption one after the other produced data points (time of light adaptation), inscription devices that might convincingly conjure an easily remedied problem (vitamin A deficiency).Footnote 3 Confident that he would discover deficiencies even before he collected any readings with his apparatus, Platt carried British Drug Houses’ vitamin A capsules to the field.Footnote 4 Amid international enthusiasm generated by the discovery and isolation of vitamins, capsules were a technical solution that conveniently averted criticisms of structural factors that contributed to malnutrition and narrowly defined success as the achievement of appropriate levels of individual nutrients.Footnote 5 The Survey data, however, indicated caloric consumption deficiencies during some, but not all, months of the year (such as during times of intensive agricultural labour that required high stores of energy). Nonetheless, economic circuits and imperial corporate interests – in tea and medicine capsules, respectively – met when the adaptometer was fitted over Africans’ heads (and eyes), making them amenable to measurement, calculation, and improvement. The tea-box test was one of many modes of data collection employed by a Survey team of multidisciplinary researchers (including a botanist, agriculturalist, and anthropologist) who gathered data on health and illness, farming and eating practices, anthropometry, and economies from residents of three villages over about two years.Footnote 6

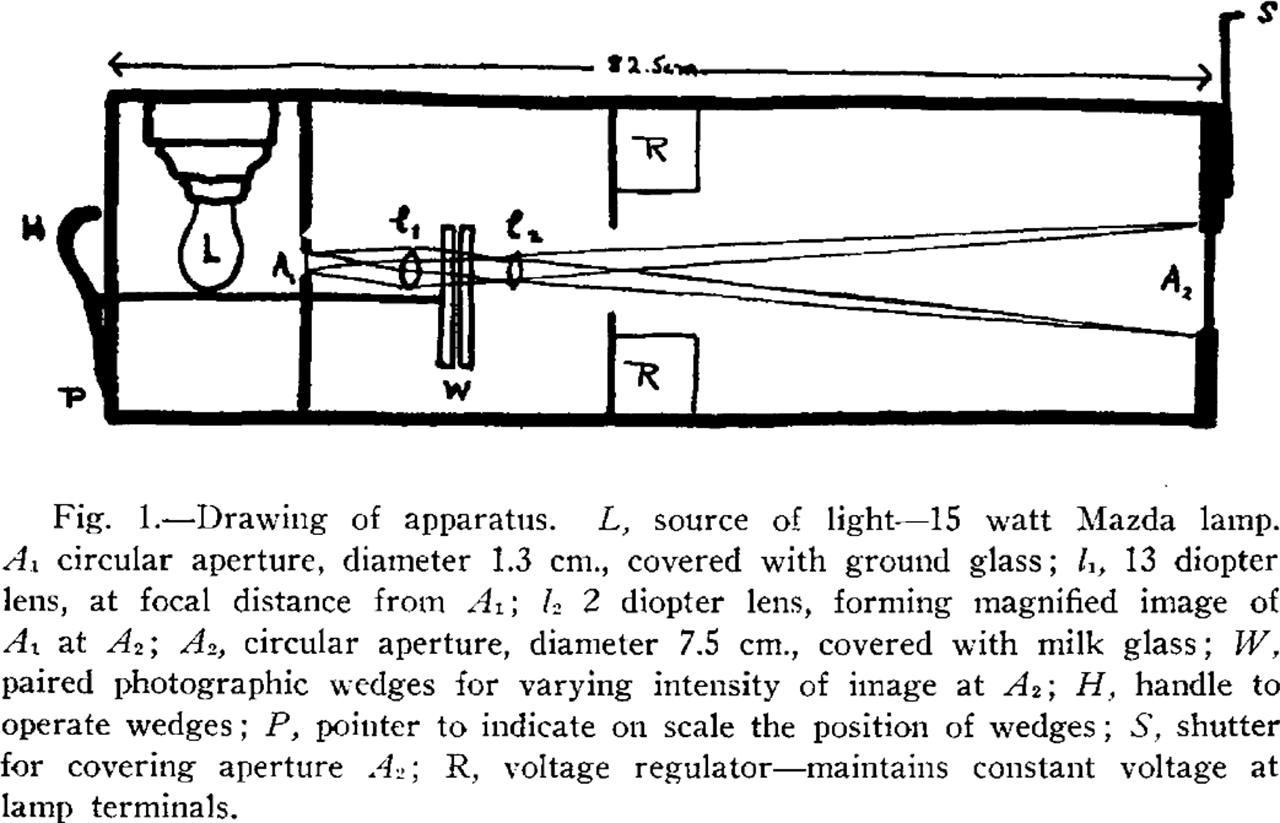

The image of Africans outfitted with this tea-box contraption in the name of nutrition science speaks, first, to how African populations were and are testing grounds for experimental methods, technologies, and theories.Footnote 7 It also gestures at the difficulties of doing science in the field, an out-of-doors place constructed as fundamentally different from the ideal-type laboratory where the purity of scientific processes and the functionality or availability of technologies and instruments are taken for granted.Footnote 8 Platt, like other field scientists before and after him, grappled with challenges posed by conducting scientific work in a faraway place fraught with unpredictable climatic, geographical, and social conditions that could threaten his experiments, instruments, and data collection.Footnote 9 Platt was invested in devising new techniques and methods that would maintain scientific rigor without ‘elaborate equipment’;Footnote 10 the International Institute of African Languages and Cultures that supported the Survey saw it as a testing ground for fieldwork methodologies, ‘an experiment to the methods of research best suited to the African conditions’.Footnote 11 While it was a humble imitation of standard adaptometers in use at the time (Figure 1),Footnote 12 Platt’s meticulous step-by-step assembly instructions mark the tea-box contraption as apparently scientific.Footnote 13 His pride in the field-readiness and efficacy of this device gave his Frankensteinian creation a pre-emptive longevity in its possible re-creation by future field researchers. His orientation to the field – as the new frontier for nutrition science – demonstrates faith in the universal applicability of Western science and its instruments, even if cobbled together from simple materials.Footnote 14

Figure 1. A sketch of an adaptometer and its parts reproduced from George S. Derby, Paul A. Chandler, Louise L. Sloan, ‘A Portable Adaptometer’, Transactions of the American Ophthalmological Society 27 (1929), 35.

This article takes the curious commingling of commodity objects and scientific materials (where a discarded tea-box finds new life as an experimental technology) as an entry point for examining how scientific practices are woven from threads that are semiotic and material and demonstrating how heterogeneous social and material elements overlap and influence one another.Footnote 15 Moving outwards from Platt’s tea-box technology, I trace the layered meanings of ‘tea’ that circulated in 1930s Nyasaland to show how racialised anxieties wove their way into the design, implementation, and discourse around the Survey. Attending to the material culture of science permits us to move beyond the textual sources that guide archival research to home in on scientific routines, practices, and relations.Footnote 16 I interpret the tea-box’s integration into the Survey not as incidental, but rather as a serendipitous clue. The tea-box reminds us that colonial nutrition research was happening alongside and through imperial circuits and towards imperial economic advancement in the register of human capital; science (and a scientific device) ‘bears the imprint of its location’.Footnote 17 For instance, at the time of data collection, tea was a commodity crop indicative of Nyasaland’s health and entangled with economic and labour concerns tied to the problem of African nutrition. Following work such as Robert Kohler’s on field biologists,Footnote 18 this article first analyses how Platt’s tea-box adaptometer – and the discourses and ambitions framing the Survey – imagined a new kind of nutrition research, hinged to the space of the field rather than the laboratory. It then proceeds to consider how the tea-box, an incipient manifestation of ‘appropriate technology’, points us towards the more tacit ways that tea wove itself into the fabric of the Survey and colonial society, as a gustatory discourse steeped in racial anxiety. Throughout, the article models how attending to the ‘stuff’ of historical scientific work helps us understand how data and the instruments that produce them are constituted by local contexts, discourses, and relations.

The Survey was carried out in the late 1930s, but a final, formal report was never published.Footnote 19 In 1992, the wife of a former member of the Survey team published the surviving papers as a collection. Several scholars have engaged the Survey papers in their explorations of colonial nutrition and other questions in Malawi. Luke Messac, for instance, analyses the Survey as a laboratory for cutting-edge research and interventions that aimed to make colonised labour healthier and productive across the British Empire; he demonstrates how concerns about productivity articulated in the register of poor nutrition minimised the possibility that workers were engaging in foot-dragging rooted in resentment of poor working conditions.Footnote 20 The London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (LSHTM) Archives have used the Survey papers to build an interactive online exhibit to show how colonial attitudes and beliefs informed the Team’s work.Footnote 21 Megan Vaughan is using the Survey to explore the dynamics of what she terms ‘colonial metabolism’ – the interchanges and transfers of energy and extraction that characterised relationships between human bodies (and gut microbiomes) and colonial political economy.Footnote 22

Historian Cynthia Brantley’s book-length examination of the Survey illuminates the tensions between researchers and between African livelihoods and European ways of conceiving them.Footnote 23 She underscores the limitations of interdisciplinary development work, despite rising enthusiasm at the time, and demonstrates how British misreading of African social life – such as what a ‘household’ was or assumptions that villages were discrete and autonomous units – inflected the data they collected. While she observes that the Survey team exhibited paternalism and blamed malnutrition on African ignorance rather than colonial disruptions to their social worlds, Brantley does not explicitly consider how data themselves were forged in and through racialised truisms and anxieties that Team members held about the problem of ‘African nutrition’ and Africans more broadly. Nor does she attend closely to the ins and outs of scientific work and the relations, material culture, and political ecologies in which the Survey was carried out. Towards this end, I referenced the published papers of the Survey and secondary literature cited herein, and correspondence, reports, and other documents pertinent to the planning and implementation of the Survey in the Malawi National Archives in Zomba and the Society of Malawi Reference Library and Archives in Blantyre.

The Nyasaland Nutrition Survey in context

The Nyasaland Nutrition Survey, carried out between 1938 and 1943 in three villages in Nkhotakota district in north-central Malawi,Footnote 24 came about at a time when the problem of nutrition among the peoples living under the British Empire was a rising concern. In 1936, a circular authored by the Secretary of State for the Colonies indicated that nutrition was ‘regarded one of the most important aspects of public health work in all countries’.Footnote 25 The ‘discovery’ of malnutrition in the colonies between the wars generated anxieties about the sustainability or reproduction of imperial networks;Footnote 26 in Malawi, anxieties coalesced specifically around the feasibility of extracting labour from able-bodied males on local plantations or exported to mines or farms in neighbouring southern African locales.Footnote 27 In the late 1930s, a labour crisis left thousands of pounds of tea in Nyasaland unplucked, for instance, generating significant investment on the part of the colonial government in finding ways to keep Malawian men at home amid what was perceived by colonial officials to be a ‘mass exodus’ that threatened commodity crop economies; such economies were indicators of Nyasaland’s ‘health’.Footnote 28

In 1939, the Committee on Nutrition published the lengthy First Report on Nutrition in the Colonial Empire, which presented summaries of the problem of nutrition across forty-eight territories based on individually submitted reports. The Report argued that improving nutrition was central to the health of the Empire and a sound investment, given widespread concerns about the ‘inefficiency of labour in industry and agriculture’Footnote 29 and shortages of labour. So, too, would greater consumption of foodstuffs across the Empire ‘increase the local market for local food products’. While the first draft of the Report presented malnutrition as a matter of political economy, the second emphasised ignorance and poor management of agricultural land, a narrative that minimised imperial responsibility for malnutrition.Footnote 30

The Report was a watershed moment in its call for multidisciplinary field surveys that would take a holistic perspective on the problem of nutrition, encouraging a move away from laboratory-focused research. A 1938 proposed scheme for the survey in Nyasaland explicitly juxtaposed its focus on ‘natives living under tribal conditions’ with prior research on nutrition in Africa, which had been confined to ‘artificially induced conditions such as hospitals, labour camps, and prisons’. The Secretary of State emphasised that the ‘chief need at the present time is not for elaborate laboratory research on such questions as the rates of energy exchange in tropical races… but for field survey work on the diet of both rural and urban people’.Footnote 31 His words gesture at a nascent global shift, beginning in the inter-war years, away from pathological medicine and towards surveillance medicine, whereby apparently healthy individuals are screened, often outside the clinic or laboratory, for hidden abnormalities or conditions.Footnote 32

The conjunction of scientific knowledge and British colonial development agendas in the 1930s meant the field sciences like demography or anthropology were conceived as key to producing knowledge and experiments that would enable Britain to better govern and understand its peoples.Footnote 33 Indeed, the Nyasaland Survey’s investment in employing multidisciplinary approaches to understand the social and environmental conditions of rural communities in Nyasaland was commendable, and might be read as an early example of the very kinds of interdisciplinary research that are in vogue in global health today, even if they are laden with the very same struggles of meaningful integration and coordination that beleaguered the Survey team.Footnote 34 The growing infrastructure and councils for colonial research marked the emergence of a ‘heterogeneous system of expertise’ and multidisciplinary approach that necessitated new methods for collecting data in field settings;Footnote 35 it heralded what Bryceson Nkhoma has termed the second colonial occupation of agricultural, veterinary, and nutrition experts.Footnote 36

Prototyping field research and appropriate technologies: making a tea-box scientific

In a broader imperial discourse around nutrition, the Nyasaland Nutrition Survey, already underway when the Report on Nutrition was published, was seen as a prototype field survey and received outsize support.Footnote 37 With hubris, Platt envisioned himself as pioneering best practices for the field, evident in his preoccupation with developing functional techniques that could act as templates for future researchers.Footnote 38 The Team’s efforts to quantify and document everything aimed to help a fledgling field-based nutrition science attain credibility.Footnote 39 The Colonial Office placed great faith in Platt’s ability to ‘establish the methods to be followed in similar surveys elsewhere’.Footnote 40 Platt even suggested that the area in which the Survey was carried out might be ‘developed into an experimental ‘Colony’ in which almost all of Government’s aims for native betterment might be tried out’.Footnote 41

It is unsurprising that Nyasaland, one of Britain’s poorest dependencies, was deemed an apt site for the field survey. A few years before its initiation, the British Central Africa Company’s manager speculated that if left to their own devices, Africans living in Nyasaland would starve to death. Meanwhile, Nyasaland’s Governor advocated for the Survey to be carried out there for the positive attention it would draw and the funds it would bring in the wake of the Great Depression,Footnote 42 providing evidence to the Committee that Malawian peasants ate unbalanced diets lacking in protein and adhered to a ‘random’ or ‘irregular’ eating schedule.Footnote 43 But so, too, did the Survey’s focus on nutrition – seen as key to efficient and productive labourers – align with the interests of the Nyasaland government and planters. In a 1939 meeting of the Native Welfare Committee, for instance, the attendees debated whether lack of foodstuffs was responsible for emigration and a shortage of labourers; the Director of Medical Services argued that dams could play a valuable role in ensuring that more permanent crops could be grown, helping ‘to keep natives in this country’. They also noted that one reason why local planters found difficulty in securing labour was because they did not feed their workers as well as South African and Southern Rhodesian employers; the Governor expressed similar sentiments in 1937 when he opined that ‘labourers who return [to Nyasaland] are invariably stronger and healthier than when they went to the Rand [South Africa]’.Footnote 44 One backdrop to these discussions about labour, nutrition, and emigration was the growing success of tea cultivation and the labour needs of planters in 1930s Nyasaland. While the Team was in the field, Nyasaland implemented concerted efforts to create internal markets for its tea.

It is thus no coincidence that the tea-box was on hand, lying around waiting to be transformed into an experimental tool by Platt. The headquarters of the survey party were in a house at a mission station halfway between the survey villagesFootnote 45 where white team members likely partook in tea-drinking and socializing on breaks from their work in the field. Tea advertisements in The Nyasaland Times, an English-language newspaper, indicate that tea grown on local estates was packed in nets stuffed into wooden cases,Footnote 46 so we might assume that Platt’s five-pound tea-box took this form. The box’s shape, a good ‘fit’ for its intended test subjects and forming a vessel within which the innards of this makeshift technology could be assembled, likely caught Platt’s attention and prompted him to fashion it into the scientific device it became.

Interestingly, however, even as Platt aimed to devise universally applicable methods and best practices that future field surveys elsewhere could copy, his work on the ground required an appreciation of the specific conditions and context of Nyasaland. While histories of ‘appropriate technology’ locate the concept’s origins in a 1960s-era enthusiasm for small and simple technologies deployed to solve problems in the global South,Footnote 47 Platt’s tea-box adaptometer embodied these principles of technical minimalism, a legacy continued by researchers studying dark adaptation in Kenya and Bangladesh today who work to design ‘compact, low cost, and easily operated device[s]’ for use under ‘difficult field conditions’.Footnote 48 Although Platt’s device took shape through his combination of specific objects and materials found in Nyasaland at the time and his detailed instructions for its re-creation encourage a fidelity to design by future researchers, his tea-box adaptometer assumes a certain fluidity in which, say, the tea-box could be replaced by any number of objects, depending on what is on hand, with similar dimensions and qualities.Footnote 49 Notably, Platt’s enthusiasm for his device christens it as a kind of technology birthed by white, Western ingenuity, a machine that extends measurable things and experiments into the field, even as it reinforces his flawed assumptions that Africa is ‘technology-poor’ and obscures the fact that Africans have themselves been innovative makers of technological things for generations.Footnote 50

Colonial sociotechnical systems, including the equipment and instruments of the Survey, embedded racial difference.Footnote 51 In Platt’s account of the adaptometer and his attempt to craft a technology ‘appropriate’ for African conditions, the figure of the ‘simple native’ looms large. The phrase divests individual subjects of personhood and corrals them under the homogenizing logic of racial and intellectual difference, making individuals into interchangeable units of experimentation. Yet, the test subjects are not passive; they are compelled to participate in the experiment by learning to ‘appreciate what is required [of them]’. Platt indicates that if a subject fails to cooperate with his role as a research subject, he is ‘too stupid to be of any value’. Such characterisations were commonplace in colonial discussions of African patients in biomedical encounters, where Africanness was associated with stupidity, ignorance, unreasonableness, and obstinance.Footnote 52 While Platt celebrates his do-it-yourself (DIY) adaptometer as a portable and easy-to-use scientific device, it is notable that his framings of the Africans whom it would be measuring indicate that a technology is not a bounded off thing comprised only of its mechanical parts; the adaptometer encompasses, as well, the worlds and relations into which it enters. So, too, the data points it produces are not merely replicable measurements but come to entangle and gain meaning with reference to their contexts of production.

Platt, in his thorough laying out of the particulars of his experiment, is clearly invested in its precision, its replicability, and its scientific value.Footnote 53 Yet, even as the tea-box seems to achieve a certain threshold of scientific validity and authority by virtue of its ability to produce data points in a standardised manner, its numerical outputs did not stand alone as evidence or not of malnutrition or vitamin A deficiency. Rather, they were read through white experts’ imaginations of what healthy (and unhealthy) Africans looked like, making the DIY device material cover for those preconceptions. Physician Dr. W.T.C. Berry makes this clear in a letter he wrote to Platt (who was away in London) from the field. His letter expresses alarm over the fact that he used Platt’s apparatus in his absence and found some grave inconsistencies in the readings it provided, even after he made adjustments to the device.Footnote 54 Notably, he couches his concerns about the apparatus’ function in his sense of which subjects are healthy or not, based on their appearance: ‘A series of ten scaly folliculotic brats…gave performances just as good as my healthy clerks!’Footnote 55 he writes. His observation of ‘scaly’ skin as a symptom of vitamin A deficiency is, of course, aligned with knowledge of clinical symptoms; in the 1930s, researchers studying the condition called attention to the ‘dry, scaly, shriveled condition of the skin among infants affected with [deficiency]’.Footnote 56 Yet, even though the readings he collects indicate ‘good’ performances or vitamin A sufficiency, his preconceived assumptions that African children he pejoratively termed ‘brats’ must be less ‘healthy’ than his clerks reveals how numbers or data become entangled with wider discourses. In this case, Berry rejects the data produced by Platt’s adaptometer because it seems impossible that African ‘brats’ could be healthy. Medical forms employed by the Survey were ten pages long and included thirty-three clinical criteria that could show malnutrition; while the Team did not find any cases of classical deficiency diseases like beriberi or pellagra, they did find ‘physical signs of malnutrition’.Footnote 57 As Brantley notes, however, ‘even when expectations were different from findings, they [the Team] proceeded based…on [their] expectations and preconceived notions’.Footnote 58 The reliability and accuracy of Platt’s device, then, does not stand outside the investigator’s impressions of the health of the subjects being tested.

Indeed, physical symptoms of African research subjects were diagnosed in a broader context of racial anxieties, stereotypes, and tropes. John Nott suggests that dermatological signs of malnutrition – sometimes described as ‘crazy-pavement dermatitis’ – were made more dramatic by their presentation on black skin, as well as by the white-colonial obsession with blackness.Footnote 59 Rana Hogarth, in her analysis of mid-nineteenth-century concerns about the nutrition and declining vigour of enslaved labourers on Caribbean plantations, shows that plantation physicians were especially attentive to changes in skin colour associated with diet that, in some cases, transformed blackness into lighter complexioned variants.Footnote 60 Elsewhere, I analyse how African hair became, for the Survey researchers, potential evidence of poor nutrition.Footnote 61 For example, the Team repeatedly used the term ‘staring’ to describe those Africans whose hair was deemed to be abnormal, a term that connotes roughness or a bristling nature and whose etymologies lie in livestock science. Hair texture and style have long been important markers of proximity to whiteness.Footnote 62 Berry’s worry over the failure of Platt’s apparatus betrays the abiding racial taxonomies through which he and other colonial nutrition scientists encountered their research subjects. Scaly skin or ‘staring’ hair are markers of malnutrition or poor health in the context of the Survey (even when numerical data may have indicated otherwise), but the technology of classification is the colonial order of things, an order that the tea-box’s scientific ambitions simultaneously obscure and reproduce. The tea-box contraption and the explicit discussion around its material qualities and efficacy in the Survey’s pages reveal how racial hierarchies and imaginaries of African racial difference became attached to and embedded in technologies (and data) themselves, informing the making of colonial nutrition knowledge and assessments of African subjects’ health status.Footnote 63 Yet, the tea-box, emptied of its original cargo and transformed into a scientific apparatus, also points us towards more tacit ways in which tea wove itself into the fabric of the Survey and colonial society as a gustatory discourse steeped in racial anxiety.

Gustatory anxieties: ‘the cup of tea and scone type of diet’

While the tea industry in Nyasaland initially struggled to produce high quality tea and lacked a local market,Footnote 64 between 1930 and 1940, Nyasaland’s white tea planters began to enjoy some prosperity: in this decade, the total acreage of land under tea doubled and tea became the Protectorate’s largest export earner and most valuable cash crop in 1938–39.Footnote 65 Amid a ‘miniscule white and impoverished black population’, the Tea Market Expansion Board, founded in 1937, sought to increase local consumption, including among Black Africans, through propaganda.Footnote 66 A traveling canteen gave demonstrations of tea-making in Nyasaland markets and kiosks established at railway stations and distributed over one hundred thousand free cups of tea and scones; tea was also issued to African tea pluckers themselves.Footnote 67 Permanent tea shops were erected at railway stations across the country and granted free firewood from the Forestry Department to ease their operations. Tea was added to the diet sheets of institutions such as the King’s African Rifles, prisons, and hospitals in the Protectorate; a canteen was erected at a customs post in southern Malawi for the ‘convenience of natives passing through’.Footnote 68 Such campaigns to increase African tea consumption appear to have brought success, even if the Chairman of the International Tea Market Expansion Board cautioned Nyasaland’s African Tea Association against expecting ‘too quick results’.Footnote 69

The rising popularity of tea is evident in the Survey Papers, where it seems to have taken on outsize importance in relation to the question of African nutrition. Margaret Read, the anthropologist employed by the Survey, reported in her fieldnotes that Africans were ‘imitating [the British] diet’ by buying tea and sugar and making scones.Footnote 70 She hypothesised that Africans eat ‘European foods such as tea, sugar, and bread’ – ‘imitat[e] our diet’ – because they admire ‘our [British, European] health and energy’. Health and energy were two of the variables that were of central interest to the Survey researchers, measured scientifically using a metric called man equivalent hours (MEH), which assigned men, women, and children to one of three classes of productivity (based on how much work could be completed in one hour), assessed against ‘good men in the village who were considered to be equivalent to standard men with a value of unity’ or ‘top grade man’. The relative labour values of each class were compiled by Platt into a table of ‘efficiency coefficients of men, women, and children in agricultural operations’.Footnote 71 Such a metric, read alongside the qualitative assessments about the health and energy of Nyasaland Africans made by Survey team members, cloaks colonial notions of African difference in scientific garb. It obscures how imaginaries and definitions of health or energy rely on and mobilise tropes and stereotypes about Africans, evident in the taken-for-granted assumption that the British team members (‘standard man’) were healthy and energetic, and Africans were not. Food and drink were taken to be variables with the ability to enhance or degrade the energy, vigour, or health of Africans.Footnote 72 Driven by a clear desire to improve African eating habits and preferences, the Team aimed to advise their research subjects about good and bad foods (and drinks). For instance, team dietitian Jessie Barker (later Williamson) authored a lengthy handbook of nutrition (titled Tiyene Tikadye!, Come, let’s eat!) meant to be used by African teachers. While it was never published, its didactic tone and hand-drawn images reveal much about European imaginaries of African nutrition, decision-making, and morality. In the manual, she suggested, ‘there is no nutritive value’ in tea unless milk or sugar are added, though she admitted tea was a good way to warm the body on a cold day or to revive the spirits.Footnote 73

For the Survey team, tea, part and parcel of Britishness, became a site of anxieties documented by scholars working elsewhere in British colonial Africa that Africans might copy them so well as to collapse social, status, and racial differences between them; even as Europeans wished to ‘civilise’ Africans, they were invested in upholding social hierarchies.Footnote 74 In Nyasaland, such dynamics came to a head during Malawi’s violent anti-colonial uprising in 1915, where African minister John Chilembwe led his followers from his church to a cotton plantation where they killed three Europeans. Chilembwe often went about in a three-piece suit and bow tie and critiqued Christian teachers for allowing their wives to dress in simple village clothes. Europeans found Chilembwe’s vestiary aesthetics to be a disturbing mimicry of power by the ‘native Christian’. Europeans often debased well-dressed middle-class Africans by asking whose slave they were or insisting Africans greet them on the road by removing their hats. These indignities surfaced as primary agitators of the uprising in Africans’ testimonies in the Commission of Inquiry after the event and demonstrate Europeans’ simultaneous desire for and fear of Africans’ modernisation.Footnote 75 Commodities often played a central role in colonial mimicry or imitation, as we see here, where consumption of scones, tea, and sugar see Africans ingesting foodstuffs coded as British and symbolic of civility and whiteness. Consuming tea and scones, while unremarkable for some, becomes a charged cultural act, a form of ingestion that is racialised in and through the larger political discourse and imperial economies.Footnote 76 Colonial discourse about tea and other commodities like soap, sugar, or clothing reveal the ambivalence and anxiety that the prospect of Africans using the same commodities in the same way as British counterparts generated.Footnote 77 On the one hand, missionaries and colonial officials desired to convert their African subjects into proper British subjects. As Warwick Anderson has shown, the colonial space was one of somatic disciplining, where the colonised body was imagined as a pliable canvas for the designs of the coloniser.Footnote 78 As early as the 1880s, missionary David Clement Scott of Blantyre mission cultivated in his parishioners a desire for afternoon tea rituals and aimed to mould them into proper British subjects: ‘Every Saturday afternoon…senior boys or girls were invited to the Manse for tea…he taught the young folk how to behave easily in European company’.Footnote 79 Yet, on the other hand, the normalisation of tea consumption among Africans was a source of colonial handwringing. Even as creating a local market for and popularizing tea (and milk and sugar) among Africans was a key interest of tea companies restricted by export quotas,Footnote 80 the Survey Team’s notes and reflections frame tea consumption among Africans as threatening to their nutrition and well-being, as faddish, and as incongruent with British assumptions of fundamental African dietary difference, which they linked to rural and agricultural spaces. As Lynn Thomas shows, reactions to African uptake of mannerisms, behaviours, and commodities were highly ambivalent; in South Africa, the figure of the ‘modern girl’, for instance, was vexed, seen as a sign of racial uplift or a poor imitation of white, coloured, or Indian women.Footnote 81

Yet, even as colonial figures fixated on Africans’ supposed desire to copy them, commodities and other material culture imagined as having originated with Europeans were semiotic shapeshifters in the relations, meaning making, and hands of Africans, producing worlds, stories, and possibilities for self-fashioning that transgressed or escaped the confines of colonial assumptions about such objects.Footnote 82 On the colonial Zambian Copperbelt, for instance, young girls who adopted modern and stylish apparel turned these garments into expressions of Christian modernity and respectability, despite missionaries’ vexation about such sartorial choices that, for them, signified immorality, cultural degeneration, and a renunciation of Christianity.Footnote 83 So, too, is it worth noting that the ‘invention’ of commodity objects like soap or tea were not ‘Houdini acts of white people’ but, rather, the results of a long history of translation and mobility of African (and other) knowledge and practices via the circuits of imperial domination and extraction.Footnote 84 Given the overwhelming weight of apprehensions about Africans and their engagements with tea, their mobility (for labour), their supposed disinterest in farming, and their ideas about nutrition that are well-preserved in colonial discourse on these topics, we are reminded of the difficulty of knowing how the interventions and discourse that characterised the Survey were interpreted by Africans themselves, as Meghan Vaughan has also noted for colonial biomedicine.Footnote 85

In the Survey papers, tea (and the risks of Africans mimicking European diets) figures prominently into discussions about African health and nutrition.Footnote 86 The Team observed that the rise of the canteen – a new ‘fashion in food’ (sponsored by the Government, as discussed above) – was ‘popularising the cup of tea and scone type of diet’ [my emphasis]. Data collected in the context of household goods inventories documented a growing number of ‘teapots…appearing in the villages’.Footnote 87 The drinking of tea and purchasing of teapots – among other gustatory ingestions and forms of commodity consumption – were seen as harbingers of change in African society that would lead to poor health and malnutrition. Such trends were blamed on Africans’ exposure to European sensibilities and commodities through work as cooks or house help, which indicated their desire to ‘progress in the direction of European foods’ and portended a loss of interest in ‘village resources and how to make the best use of them’.Footnote 88 Because European foods required cash, money figured into the Team’s assessments of shifts in African diet. Team members worried about the growing tendency of Africans with money earned abroad to purchase rather than grow their own food, even if, ironically, the Survey’s presence (via their need for local labour and the remitted hut taxes) increased the money circulating in the area. ‘If this practice [buying food] spreads’, they hypothesised, ‘the reduced crops consequent on the reduced acreage under cultivation will lead to a shortage and…famine’.Footnote 89 In her manual, Williamson advised Africans that although ‘there are many kinds of European foods in the stores and some of these, such as condensed milk and sardines, you like very much… they are expensive to buy and you should only buy them as a treat on very special occasions’.Footnote 90 She adds a cautionary note: ‘Many [South Africans] have lived in towns for so long that they have forgotten many of their old good foods and prefer to eat less nourishing European kinds’.Footnote 91

Despite their anxieties about African uptake of European food and habits, the Team did not hesitate to employ commodities as incentives to induce participation in their data collection activities.Footnote 92 Common salt, then produced on the East African coast and imported from Portuguese East Africa,Footnote 93 facilitated the collection of anthropomorphic data at households: ‘A pinch of salt helps in winning the co-operation of a fractious child and the mother is usually rewarded for her help with a small amount of salt’, Platt wrote.Footnote 94 The Survey clinician observed, ‘for salt, the children come up, have their gums examined’.Footnote 95 Salt as payment for research cooperation reprises a history of commodities like calico cloth, salt, and soap being paid as barter goods in exchange for African labour, including on Nyasaland’s tea plantations.Footnote 96 In the early twentieth century, Malawian missionary Harry Kambwiri Matecheta distributed salt to those who attended his church services.Footnote 97 Whereas local salts and potashes made from ash from organic materials were produced by women to season and soften food during cooking, commodity salt (mchere wa chizungu, white people’s salt, common salt) was a distinct colonial commodity purchased in pennyworths from Indian stores.Footnote 98 Dietitian Jessie Williamson noted that ‘when an [African] man buys a bag of common salt for sale in the village, he will give all the villagers a pinch to taste before he starts to sell it’.Footnote 99 So too did anthropologists and colonial officials fixate on the less savoury cultural superstitions around salt, which continues to be seen as a dangerous vehicle for transmission of various sicknesses if used improperly or added to foods by a woman who is menstruating. Salt, like tea, was at once a commodity to be sold to Africans, a product through which discourses of racial anxiety manifested, and a dietary component to be measured and converted into data. As Platt instructed, ‘Descriptions of cooking methods should include the nature of components in the preparation of a dish, the use of common salt and native ‘pot ashes’ …’Footnote 100

Much as European commodities and foodstuffs captured the Team’s attention, researchers were also preoccupied with backwards dietary practices they deemed to be of little nutritive value. Barker and Platt worried over earth eating, especially by African women and children, who allegedly ate mud from hut walls and ant hills in ‘bits about the size of a lump of sugar’, prompting them to request information from the Department of Agriculture about the composition of earths eaten by Africans.Footnote 101 Earth or dirt eating has long been a preoccupation on the part of white people about Black people. Plantation physicians in the Caribbean feared it would weaken slaves on plantations, casting it as a racial pathology called Cachexia Africana (dirt eating). Cachexia Africana ‘reinforced white fantasies of black bodily potential for slaves suffering from this complaint failed to meet the standard expectation of an idealised productive black body’.Footnote 102 Coding the practice as backwards or pathological, given that it was observed to occur mostly in women and children, reinforced narratives like those in the Report on Colonial Nutrition about the inability of Black women to properly feed themselves or their children.Footnote 103 In the antebellum American south or in colonial Malawi, discourses about dirt-eating, which scholars have suggested was a sensationalised practice that occurred much less frequently than experts suggested, affirmed that Black people’s bodies were peculiar, pathological, and in need of white care and intervention. In this regard, dirt and tea alike become gustatory idioms of difference, the former anchored in imaginaries of African backwardness and the latter hinged to a too-modern African.

Conclusion

‘All that is needed is the desire on your part to be well fed and the will to carry out the necessary thought and work. If you have this desire and the necessary will power then you can feed yourself and your family well and help to breed a fine healthy race of Africans in Nyasaland’.Footnote 104

In her manual, Jessie Williamson encouraged Africans to find the willpower to feed themselves well. Her advice reduced nutrition to a bounded phenomenon, a set of processes of energy exchange contained in the body proper that an individual might manage well or poorly. Mind over matter, she emphasises. Such body-centric renderings of nutrition underpinned the entire Survey, which presumed that poor nutrition was a problem of Africans’ ignorance, poor food choices, or inadequate farming practices. These assumptions rhetorically abstracted bodies, food, labour, and farming practices from their political, cultural, and economic surroundings. While metabolism was a central concern of the Survey Team, Megan Vaughan notes that the data they left behind inadvertently reveal that ‘metabolism was more than calories in, calories out’, more than a calculation of daily protein and energy expenditure.Footnote 105 Confining metabolism to the body overlooks how nutrition, calorie counts, or energy expenditure are entangled in larger colonial economies and exploitations and racial capitalism.Footnote 106 Hannah Landecker reminds us that human historical events and processes, including colonialism, materialise as biological events, processes, and ecologies.Footnote 107 Neither biology nor metabolism is contained in bodily packages.Footnote 108 Yet, the Survey’s data practices reveal a preoccupation with bounding off the problem of African nutrition from its larger contexts, as apparent in their presumptions that the villages themselves were viable and comparable units of production and consumption.Footnote 109 They operated to isolate the African body as an object of study. Platt’s makeshift tea-box adaptometer, for example, housed Africans in a dark experimental chamber, closing them off from the wider worlds to which they belonged, making them amenable to measurement and datafication. Likewise, the Survey aimed to reduce the complex determinants of good or bad nutrition into a dataset. Yet, the problem of African nutrition was not fully captured by the tools the Survey team devised or the data they collected.Footnote 110 Further, as this article has shown, the team members brought their assumptions, racial taxonomies, and hierarchies of knowledge to their research encounters in the field, and those assumptions constituted the data points amassed (as with Berry’s dismissal of performance data that indicated the health of children who, to the clinician’s gaze, looked unhealthy). The fact that Platt built his device using a tea-box, rather than something else, shows how colonial science was an endeavour entangled with Nyasaland’s imperial economies, the tea industry, in this case. As Science and Technology Studies (STS) scholars argue, attending to the location and situatedness of science is crucial to understanding how it comes to be.Footnote 111 Tea planters in Nyasaland, in concert with the colonial government, were busy promoting tea-drinking among Africans, the effects of which seeped into the Team’s data about food and drink (wherein, e.g. they documented increasing numbers of teapots and scones in native households). Tea drinking was a semiotically rich practice; while it was natural that the British Survey team members would drink tea in the field, Africans drinking tea caused great alarm.

When I encountered Platt’s peculiar DIY tea-box adaptometer in the Survey papers, I was struck by the care he took in constructing it and his dedication to recording, step-by-step, how future researchers might reconstruct it; in this way, the tea-box is a trace of a historical moment when nutrition research was transitioning from the laboratory to the field, and its practitioners’ efforts to validate its status and data as scientific. Yet, the makeshift tea-box technology also points us towards the broader discursive universe of tea and tea drinking and the imperial economies in which colonial nutrition research took shape. This article contends that attending to the ‘stuff’ of scientific work has a methodological payoff: the makeshift adaptometer fashioned from a tea-box cued me to broader imperial and economic circuits, interests, discourses, and hierarchies that infused the data the Survey Team collected and the instruments they used in the field. This seemingly insignificant discarded tea-box that became part of the Survey’s data collection infrastructure helps us home in on discourses, practices, and contexts crucial to the making of ‘African nutrition’ as a scientific problem ‘steeped’ in tea, as anxious discourse and commodity crop.

Acknowledgements

I am grateful to the three anonymous reviewers whose careful feedback and suggestions improved this article. Thanks also to colleagues who provided feedback on this project at the 2024 Niagara Seminar (especially Yesmar Oyarzun and Maggie MacDonald) and the 2023 Data and Disease in Historical Perspective Workshop in Edinburgh (especially Tarquin Holmes). The paper has benefited from astute comments and conversations about earlier versions from John Nott, Zoë Groves, and Lyndsey Beutin. The staff at the National Archives of Malawi and the Society of Malawi Archives helped locate historical sources.