Introduction

An increasing number of archaeological investigations in the Maya area and new breakthroughs in hieroglyphic decipherment have shown that pre-Hispanic Maya centres occupied positions of differing and shifting prominence in complex socio-political networks. Evidence for such hierarchical organisation—including relationships of vassalage and dependency—are being identified in the art, architecture and iconography of ancient Maya communities (e.g. Martin & Grube Reference Martin and Grube2000). This premise can be examined through a pair of recently discovered ballplayer panels from the Maya centre of Tipan Chen Uitz, Belize. Ultimately, we argue that iconography offers insights into inter-polity relationships, that the ballgame was an important mechanism for macro-political affiliation in the Maya area and that the data from Tipan are useful in considering archaeological approaches to ancient interaction spheres in general.

Since its inception in 2009, the Central Belize Archaeological Survey has pursued a regional approach to studying ancient Maya cultural development in the area between the Caves Branch and Roaring Creek drainages of the Cayo District, Belize (e.g. Andres et al. Reference Andres, Wrobel, Morton and González2011a; Wrobel et al. Reference Wrobel, Andres, Morton, Shelton, Michael and Helmke2012, Reference Wrobel, Shelton, Morton, Lynch and Andres2013; Morton Reference Morton2015). This project expands upon the efforts of the Western Belize Regional Cave Project that operated in the Roaring Creek Valley between 1997 and 2001 (e.g. Awe Reference Awe1998, Reference Awe1999; Awe & Helmke Reference Awe and Helmke2007; Helmke Reference Helmke and Nielsen2009). Surface sites recorded to date range in size from isolated house mounds, to patio-focused residential clusters, to large conglomerations of monumental architecture that can be classed as first- and second-order central places (Helmke & Awe Reference Helmke and Awe2012; Andres et al. Reference Andres, Helmke, Morton, Wrobel and González2014).

Of particular relevance to our research is the civic-ceremonial centre of Tipan Chen Uitz, first documented in 2009 (Andres et al. Reference Andres, Wrobel and Morton2010, Reference Andres, Helmke, Morton, Wrobel and González2014). In addition to its large size and architectural complexity, Tipan is distinguished by its physical integration with surrounding minor centres via an extensive network of causeways (or sacbeob) (Figure 1). Tipan's position at the hub of this network provides perhaps the most tangible evidence that the site functioned as the head of a regional polity (Andres et al. Reference Andres, Morton, González, Wrobel, Andres and Wrobel2011b).

Figure 1. Map of the Roaring Creek Works showing the causeway system integrating Tipan with the secondary centres of Yaxbe and Cahal Uitz Na (map by Shawn G. Morton and Christophe Helmke).

Among the most notable discoveries to date have been four hieroglyphic monuments, all recovered on structure A-1 at the entrance to the community's palatial complex. Two of these—monuments 1 and 2—both of which are fragmentary and exhibit incomplete texts, have been discussed elsewhere (Andres et al. Reference Andres, Helmke, Morton, Wrobel and González2014; Helmke & Andres Reference Helmke and Andres2015). Here we consider monuments 3 and 4, which were recovered during the 2015 field season. These monuments are both ballplayer panels—the first to be found in Belize—and display short but complete hieroglyphic captions. When considered in combination, these panels confirm that Tipan was the seat of an influential royal court, able to commission well-executed monuments produced by literate scribes. The court actively employed the same symbolic vocabulary in terms of monumental forms and compositions of image and text that was characteristic of the most important Late Classic dynasties.

More significantly still, these ballplayer panels may reflect a greater system of allegiances cemented in part by public performances involving vassals and overlords participating in the ballgame. Thus, our research investigates the premise that Tipan may have been part of this greater system of vassalage, tying it to the Maya centre of Naranjo and thereby—however indirectly—to the Snake-Head dynasty focused at the still larger site of Calakmul. As discussed below, Tipan's interaction with Naranjo may well imply such a relationship, as Naranjo's Late Classic kings offered fealty to their overlords at Calakmul (Martin & Grube Reference Martin and Grube2000: 74–80, 105–111; Grube Reference Grube2004; Helmke & Kettunen Reference Helmke and Kettunen2011).

Context of discovery

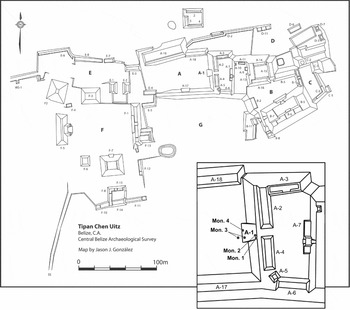

Structure A-1 forms the lowest level of acropolis A, and served as the formal entrance to Tipan's paramount palatial complex, via a Passage Range Structure (or audiencia) (Figure 2). The two large fragments of monument 3 were found lying face down on the surface of a secondary platform, just south of a looters’ trench in this structure, and on the nearby plaza (Figures 3 & 4). Monument 4 was discovered face up, on the opposite side of the looters’ trench, and had also clearly been displaced in antiquity from its original context; much like monument 3, it was found resting atop terminal-phase architecture and sealed beneath collapse debris. Fortunately, the illicit excavations passed between the monuments without disturbing either. Exposure of structure A-1’s west face revealed a poorly preserved pair of secondary terraces, or lateral stair blocks, constructed over the upper parts of the earlier stairs (see Figures 3 & 4). In both cases, these architectural units lack facings, and their destabilised dry-laid core was collapsing down the building. The available evidence suggests that monuments 3 and 4 were probably integrated into the upper reaches of the building, and may have faced portions of these deteriorated architectural units. The implications of this context are considered below.

Figure 2. Map of the monumental epicentre of Tipan Chen Uitz showing the location of the community's acropoline palatial complex (acropolis A) and the location of the monuments discovered on structure A-1 (map by Jason J. González; inset by Christophe Helmke and Christopher R. Andres).

Figure 3. Isometric reconstruction of structure A-1 at Tipan Chen Uitz showing the context of recovery of monuments 1, 2, 3 and 4 (reconstruction by Christopher R. Andres, drafted by Shawn G. Morton).

Figure 4. Photograph of structure A-1 showing architectural features exposed during the 2015 excavations (photograph by Christopher R. Andres).

Monument 3

Monument 3 would have measured up to around 1.44m wide, 0.66m high and approximately 0.2m thick when complete (Figure 5); approximately 90 per cent of the original monument is preserved. It is fortunate that the monument and its subtle carving—rendered in low relief, with foreground and background distinguished by no more than 5mm and details rendered in shallow 1mm lines—suffered only minor damage and moderate weathering. It is unknown if the breakage was accidental, the result of structural collapses or was deliberate. Defacement of the entire carved figure and differential spalling of the panel support the latter interpretation.

Figure 5. Monument 3, Tipan Chen Uitz, Belize (photograph and drawing by Christophe Helmke).

That the panel's iconography represents a ballplayer is demonstrated by the individual's pose and distinctive protective belt, and by their juxtaposition with a large circular ball. The panel may depict a ballgame that was celebrated within the ballcourt at Tipan Chen Uitz (Figure 2), or commemorates such a game played at an allied site. Although the figure's garments and headdress are mostly effaced, he holds in his left hand a staff-like object that terminates in a circular element embellished by streamers. Similar examples of this object at sites in the Usumacinta area have been identified as fans (see Houston et al. Reference Houston, Escobedo, Golden, Scherer, Vásquez, Arroyave, Quiroa and Meléndez2006: 89–92, figs 5–6). A Late Classic polychrome vase, depicting perhaps the start or the end of a ballgame, includes the bleachers above, wherein figures blow trumpets, while another figure holds precisely the same type of fan (Kerr Reference Kerr1992: 437). This presents an interesting parallel to the iconography of monument 3.

Figure 6. Monument 4, Tipan Chen Uitz, Belize (photograph and drawing by Christophe Helmke).

The ball is captioned by a glyph block of three signs, including the numeral ‘nine’ and a hand with outstretched fingers that represents the logogram nahb, for ‘handspan’ (Kevin Johnston pers. comm. to Stephen Houston 1985; Coe Reference Coe, Dominici, Orsini and Venturoli2003; Zender Reference Zender2004). Below the hand is a large scrolled sign representing a rubber ball that is partially embellished by cross-hatching (see Stone & Zender Reference Stone and Zender2011: 164–65). The whole glyph reads ‘nine handspan ball’, thereby providing an unusually complete designation for a rubber ball. While this qualifier clearly records a size gradation, it remains unclear whether the handspans refer to the length of the latex strip used to manufacture the ball, or, more probably, to the circumference of a large rubber ball (see Zender Reference Zender2004; Helmke Reference Helmke2007).

The glyphic text framing the scene is remarkably well preserved and, most unusually, appears to be complete. The clause is headed by a calendrical notation, recording a typical Calendar Round date, the juncture between ritual and the solar calendars (A1–A2). Together, these can be translated as ‘[On the day] 7 Kimi and 14 Sek’. This Calendar Round combination commemorates an historical event on an ‘uneven’ date, rather than a period-ending celebration on an ‘even’ date in the Long Count calendar. Anchoring this date to the Long Count is difficult, as this Calendar Round date re-occurs six times in the Late Classic between AD 560 and 820. Nevertheless, the closest possible date to the anchor provided by monument 1 (which commemorates the period-ending of 9.14.0.0.0 or AD 711), is 9.14.4.9.6, or 18 May AD 716 (using a GMT+2 correlation; see Martin & Skidmore Reference Martin and Skidmore2012). This is a significant anchor, as dates on particular structures and in discrete areas of sites tend to cluster together. There are, however, additional reasons for preferring this date above the other possibilities, as mentioned below.

The verb is written in a somewhat abridged form as ch'amaw (A3), involving the root ch'am: ‘grasp, take’. In other contexts, this verb is usually seen in statements of royal accession, wherein an incumbent ruler takes a sceptre that symbolises the ascent to power and new office (e.g. Schele Reference Schele1980). As Maya texts are essentially self-referential, commonly naming the very objects upon which they appear, we assume that the ‘grasping’ here refers to the ballplayer's fan. It is unusual to see such a pairing, not least because we know of no other examples showing a similar pairing of ballplayer and fan. Then again, the verb ch'am is not usually represented on ballplayer panels either, and therefore must have been significant enough to merit a careful mention. It is, therefore, possible that this represents a variant of the game involving a fan, or a heretofore unknown phase of the game.

The last two glyph blocks appear to record the name of the subject—probably the individual represented on the panel. In the first collocation (B1a), the main sign represents an anthropomorphic profile with exaggerated and elongated lips. From examples in texts at Caracol, Copan and Palenque, it would appear to name a particular wind deity, but is used here as an anthroponym (see Stuart Reference Stuart2005: 25, no. 3). The glyph below this main sign is partly eroded and therefore cannot be conclusively identified.

The final glyph block (C1) represents the profile of a feline with a water lily draped above its head. Whereas the literature usually refers to this feline as a “waterlily jaguar” (Schele & Miller Reference Schele and Miller1986: 51), glyphic captions in other texts clearly show that this is a hix or ‘ocelot’, another lesser spotted feline (Houston & Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1989: 6). The qualifying elements preceding the head of the feline (B1b) include the undeciphered waterscroll sign, with its common phonetic complement below. This logogram undoubtedly represents a body of water, or even a wave. Unfortunately, the dictionary entries of lowland Mayan languages are insufficient to provide a plausible decipherment. The combination of a waterscroll sign and an ocelot is a well-attested nominal sequence for a supernatural entity, a spiritual co-essence known as a way or wahy creature (see Houston & Stuart Reference Houston and Stuart1989; Grube & Nahm Reference Grube, Nahm and Kerr1994: 690; Helmke & Nielsen Reference Helmke and Nielsen2009; Stone & Zender Reference Stone and Zender2011). The example provided here is one of the first instances in which this nominal sequence is applied to an historical individual, although a comparable example is known from a text at Copan (Bíró Reference Bíró2010: 24). Accordingly, the individual represented on the panel, in the act of playing ball, may warrant the nickname Waterscroll Ocelot. Unfortunately, the titles that this individual bore are not recorded. This in turn implies that the figure was sufficiently well known to the original target audience that this was unwarranted, suggesting that the figure could be the ruler of Tipan. With the discovery of monument 4, however, it is unclear which, if any, of the individuals represented on these monuments was the local ruler.

Monument 4

Only the rightmost portion of monument 4 has been recovered, representing up to two-thirds of the original panel. It measures approximately 0.56m high, 0.205m thick and was originally over 0.81m wide. Its similarity in size and composition to monument 3 clearly suggests that the two monuments formed part of a set (Figure 6). As with monument 3, the carving is shallow, ranging between 1 and 6mm in depth, and a plain frame encloses the iconographic scene accompanied by a glyphic caption. As panels adorning the face of an architectural unit, these monuments may represent elements of a hieroglyphic stair, although this designation requires more conclusive evidence from future excavation.

Monument 4 also depicts a ballplayer in a dynamic pose: this figure lunges forward and braces his left knee, leaning on his left hand as though attempting to strike a ball. The marked dynamism of the scene is evident in the placement of the knee and the hand, as they burst out of the ground line defined by the lower edge of the frame. The figure wears the large and distinctive ballplayer belt, again composed of three large segments, and is lavishly adorned with regalia. Much of the attire is lost, as the left portion of the scene is eroded and suffered extensively from the breakage of the monument. The area around the face is also quite weathered and may have been deliberately hammered off. Similar damage has been noted on other contemporaneous monuments in the Maya lowlands, such as the stelae of Xunantunich (see Helmke et al. Reference Helmke, Awe, Grube, LeCount and Yaeger2010) and panel 3 of Cancuen (Normark Reference Normark2009).

Fortunately, the right portion of monument 4 suffered only moderate and even weathering suggestive of natural taphonomy. The glyphic caption is composed of five glyph blocks. The first glyph block (A1) is read ubaah, ‘it is his portrait’ (literally head), the common predicate for captions accompanying iconographic scenes. The following two glyph blocks contain the name of the individual depicted, one Janaab Ti’ Chanal K'ahk’, or ‘bird of prey is the mouth of celestial fire’. Interestingly, a partial glyphic text from a fragmentary ballcourt ring found at Naranjo (see Graham Reference Graham1980: 187), the nearest supra-regional capital in the area, also records the segment ti’ chanal k'ahk’. This piece of evidence is intriguing because at Tipan this individual is represented as a ballplayer, and at Naranjo, part of the same name appears on a ballcourt ring. It is possible, although by no means certain, that these monuments name the same individual, thus providing a further connection between Tipan and Naranjo (see Andres et al. Reference Andres, Helmke, Morton, Wrobel and González2014); in this case, in the explicit context of the ballgame.

The final glyph block (B3) represents the full geometric form of the regal title ajaw, while the preceding block (B2) is read nahho'chan, for ‘first five skies’ or perhaps ‘great five skies’. This segment provides the name of a supernatural location that is known from the textual corpus as the celestial abode for a range of deities, or as a title of particular patron deities (Schele & Miller Reference Schele and Miller1986: 52; Stuart & Houston Reference Stuart and Houston1994: 71). Nevertheless, it is rarely used as a title for historical individuals, although examples are known from Tikal and possibly Naj Tunich (see Jones & Satterthwaite Reference Jones and Satterthwaite1982: fig. 8a; MacLeod & Stone Reference MacLeod, Stone and Stone1995: 167, 178, 183).

Ballplayer panels usually depict local individuals squaring off against foreign exalted elites from distant sites. While we cannot be sure which of the two individuals represented on the panels is local and which is foreign, the features tying monument 4 to Naranjo may suggest that the depicted individual was from the latter site, while the monument 3 individual was possibly a local figure. A glyphic reference at Naranjo may support this conclusion, as discussed below.

Broader significance

The form and content of monuments 3 and 4 provide a basis for identifying specific actors within Tipan's political network. Similar panels are known for the sites of La Corona, Uxul, El Perú, Yaxchilan, Zapote Bobal, Dos Pilas, and farther afield at Tonina and Quirigua, among others (Graham Reference Graham1982: 155–64; Miller & Houston Reference Miller and Houston1987; Houston Reference Houston1993: fig. 3–22; Tunesi Reference Tunesi2007; Crasborn et al. Reference Crasborn, Marroquín, Fahsen, Vega, Arroyo, Paiz and Mejía2012; Stuart Reference Stuart2013; Grube & Delvendahl Reference Grube, Delvendahl, Helmke and Sachse2014; Lee & Piehl Reference Lee, Piehl, Navarro-Farr and Rich2014: 95–98; Stuart et al. Reference Stuart and Canuto2015) (Figure 7). Many of the sites are also known to have been vassals of the Snake-Head dynasty that had its seat of power at Calakmul during the Late Classic period (Martin Reference Martin2005). A comparable ballplayer panel has recently been found at Calakmul proper, which dates stylistically to the start of the eighth century AD (Martin Reference Martin and Skidmore2012: 160), thereby making it contemporaneous with the Tipan monuments.

Figure 7. The distribution of archaeological sites in the Maya area with hieroglyphic stairs (blue dots) and the location of sites with ballplayer panels (red triangles). Site density is indicated by purple shading (map by Eva Jobbová).

Evidence of a possible connection with Calakmul, perhaps reflecting performances focused within specific architectural contexts (such as the ballcourt at Tipan), is not necessarily unexpected when considering the ‘superpower’ status of the Snake-Head dynasty and its far-reaching influence during the Late Classic, including at supra-regional centres such as Caracol to the south of Tipan (Martin & Grube Reference Martin and Grube2000: 88–95, 105–106). At Naranjo, stela 25 records a clear statement of overlordship when it relates that Tuun K'ab Hix, king of Calakmul, presided over the accession of Naranjo's incumbent ruler in AD 546 (Martin & Grube Reference Martin and Grube2000: 72, 104). Calakmul also politically eclipsed Tikal during the sixth century AD, displacing its patronage and resulting in a shift of allegiances with former allies aligning themselves with Calakmul. Tipan's Middle Classic ceramics may provide evidence of the community's status as a client state of Tikal (Andres et al. Reference Andres, Helmke, Morton, Wrobel and González2014: 54–55). Following the defeat of Tikal by Calakmul and its allies in AD 562, Naranjo's influence increased, especially in this part of the Maya area (Martin & Grube Reference Martin and Grube2000: 74–81; Helmke & Awe Reference Helmke and Awe2012: 74–80). We previously suggested that the large monolithic panels that face the stair-side outsets at Tipan (and at its satellite sites of Yaxbe and Cahal Uitz Na) represent a regional tradition originating in the Pasión area of Guatemala, perhaps introduced to this part of the lowlands by Lady Six Sky of Dos Pilas when she moved to Naranjo in AD 682 (Martin & Grube Reference Martin and Grube2000: 74–75; Andres et al. Reference Andres, Helmke, Morton, Wrobel and González2014). This intriguing possibility gains further support from Tipan monument 3; specifically, the mention to Waterscroll Ocelot on monument 3 may echo another in the eroded text of Naranjo stela 31. Here, an individual appearing to bear the same name is cited in connection with an event in AD 719 (see Graham Reference Graham1978: 84). In addition, the name of the figure depicted on monument 4, and the repetition of the same name on the fragmentary ballcourt sculpture at Naranjo, provides yet another link between these two sites. At present, we cannot be certain that the individuals mentioned at Tipan and at Naranjo are one and the same. Considering the rarity of the names, and the contemporaneity of the monuments, however, we find this conclusion compelling.

Finally, the existence of a possible hieroglyphic stair at Tipan may provide insight into the nature of this hypothesised relationship with Calakmul. The context of Tipan's ballplayer panels raises questions about their original position on structure A-1, although the scale and horizontal format of monuments 3 and 4 suggest that they certainly could have functioned as stair risers. Sites with hieroglyphic stairs often have ballplayer panels (see Boot Reference Boot2011). The distribution of these sites seems far from coincidental, and probably represents the material imprint of greater socio-political networks of alliances and vassalage, also evidenced in the glyphic corpus (Figure 7). Thus, wide stretches of the lowlands to the east and west of Tikal exhibited either hieroglyphic stairs and/or ballplayer panels. This probably reflects the influence of the Snake-Head kingdom. Of particular interest here is a consideration of Calakmul's apparently variable levels of involvement in affairs of communities throughout the lowlands during the Late Classic (see Grube & Delvendahl Reference Grube, Delvendahl, Helmke and Sachse2014). Calakmul kings clearly exerted their influence at locations as distant as Cancuen and Quirigua. Yet in contrast with patterns evident at other sites, the political involvement of the Snake-Head dynasty does not appear to have significantly affected the agendas and trajectories of these communities (Grube & Delvendahl Reference Grube, Delvendahl, Helmke and Sachse2014: 93–94). Likewise, the absence of unequivocal evidence for Calakmul influence on Tipan's architecture and site layout suggests an indirect and less active role of Snake-Head kings in central Belize.

The far-reaching influence of Calakmul evident at Naranjo, and perhaps at Tipan, is significant relative to broader considerations of peer-polity relationships, client states and ancient interaction spheres (e.g. Renfrew & Cherry Reference Renfrew and Cherry1986). When considered alongside portable objects, architectural markers, depictions of foreign emissaries and historical documentation of inter-community and/or inter-cultural interactions in such cases as Cahokia in mid-continental North America (Griffin Reference Griffin1993; Stoltman Reference Stoltman and Ahler2000), Teotihuacan in the Valley of Mexico (see papers in Braswell Reference Braswell2003), and Hellenistic Greece (Ma Reference Ma2003), the ballplayer panels discussed here expand scholarly appreciation of the impressive range of expressions of these ancient interactions.

Investigations at Tipan have only recently begun, and direct references to Calakmul rulers in the site's hieroglyphic corpus are yet to be documented. Nevertheless, a conspicuous lack of stelae at Tipan, at least to date, combined with the presence of panels—together a hypothesised signature of Calakmul vassalage (Grube & Delvendahl Reference Grube, Delvendahl, Helmke and Sachse2014: 93)—may reflect Tipan's membership in a sphere of interaction that was presided over by the Snake-Head kings. Although the current evidence does not support strongly hegemonic relations between Calakmul and Tipan, future investigations should yield finds that will clarify the place of Tipan in the networks of allegiances connecting centres in the central Maya lowlands.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank the Belize Institute of Archaeology for granting us permission to conduct the reported research. This research has been supported and funded by a variety of institutions, including the University of Mississippi at Oxford, Indiana University-Purdue University Fort Wayne, Indiana University's New Frontiers in the Arts and Humanities programme, the University of Calgary, Michigan State University, and the Internationalisation Committee of the Institute of Cross-Cultural and Regional Studies, University of Copenhagen. We are grateful to the residents of Springfield and Armenia, Belize, for their support; and to David Hayles for granting us access to Tipan. Many thanks to Dmitri Beliaev, Guido Krempel, Felix Kupprat, Sebastián Matteo, Alexandre Tokovinine and Verónica Vázquez López for their help and comments on the hieroglyphic texts. Our gratitude also goes to Eva Jobbová, who kindly produced Figure 7 in ArcGIS. The excavation and recovery of monuments 3 and 4 would not have been possible without assistance from Franz Harder and Hugo Claro. Our thanks go to John Morris and Jaime Awe for encouraging our research in the Roaring Creek Works. Finally, we are grateful to the two anonymous reviewers for providing insightful feedback that has helped to strengthen this paper. Any shortcomings of fact or interpretation are ours alone.