Introduction

Herbicides that inhibit acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACCase) are systemic compounds that are absorbed through foliar tissues and translocated primarily via the phloem to meristematic regions, where they accumulate and exert herbicidal activity (Takano et al. Reference Takano, Ovejero, Belchior, Maymone and Dayan2021). Although translocation occurs at a slow rate, this process is crucial for delivering active compounds to growing tissues (Shaner et al. Reference Shaner, Jachetta, Senseman, Burke, Hanson, Jugulam, Tan, Reynolds, Strek, McAllister, Green, Glenn, Turner and Pawlak2014). Upon reaching the target site, the ACCase inhibitor disrupts cellular membrane integrity within meristematic zones, inhibiting cell division and elongation. This disruption impairs the development of young leaves, ultimately halting growth in susceptible species and leading to plant mortality by interrupting lipid biosynthesis (Kukorelli et al. Reference Kukorelli and Reisinger2013). The ACCase-inhibiting herbicides exhibit limited residual activity in the soil due to their high solid-liquid partitioning coefficient (K d ) and adsorption potential (K oc ). These characteristics cause the herbicides to bind tightly to soil particles, minimizing their mobility and residual persistence (Takano et al. Reference Takano, Ovejero, Belchior, Maymone and Dayan2021). Consequently, these herbicides pose a lower risk of leaching and contribute minimally to long-term soil contamination, further enhancing their selectivity and efficacy.

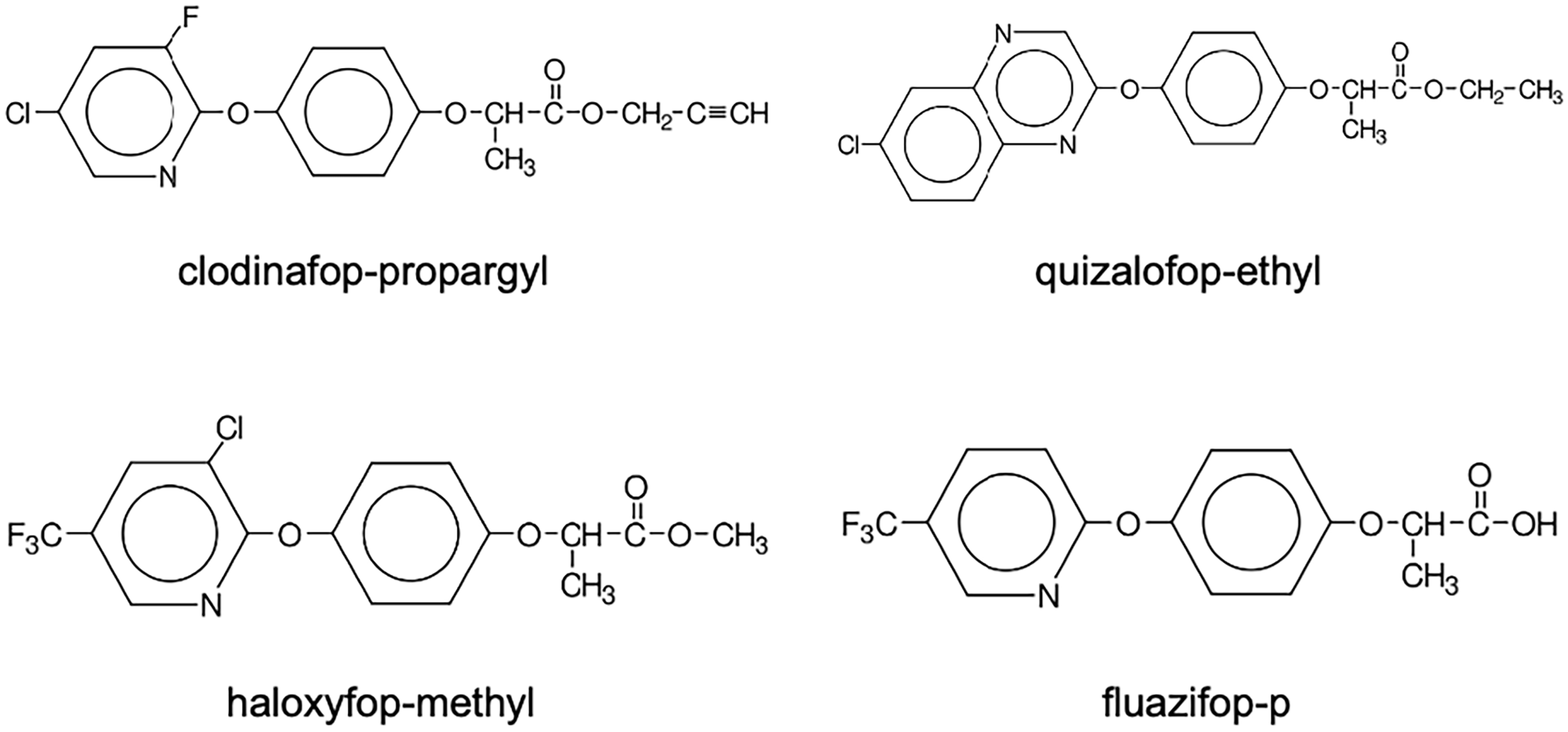

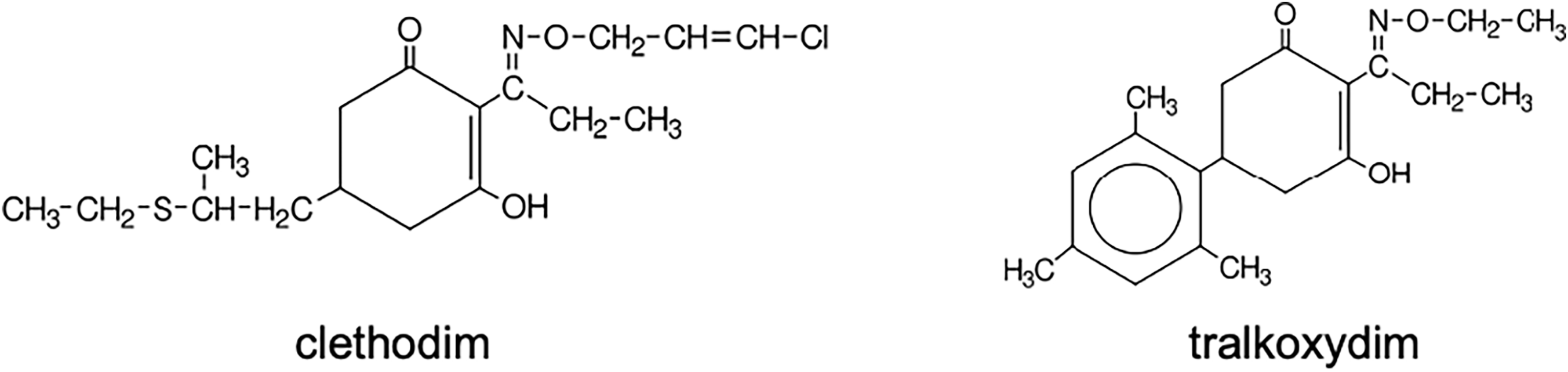

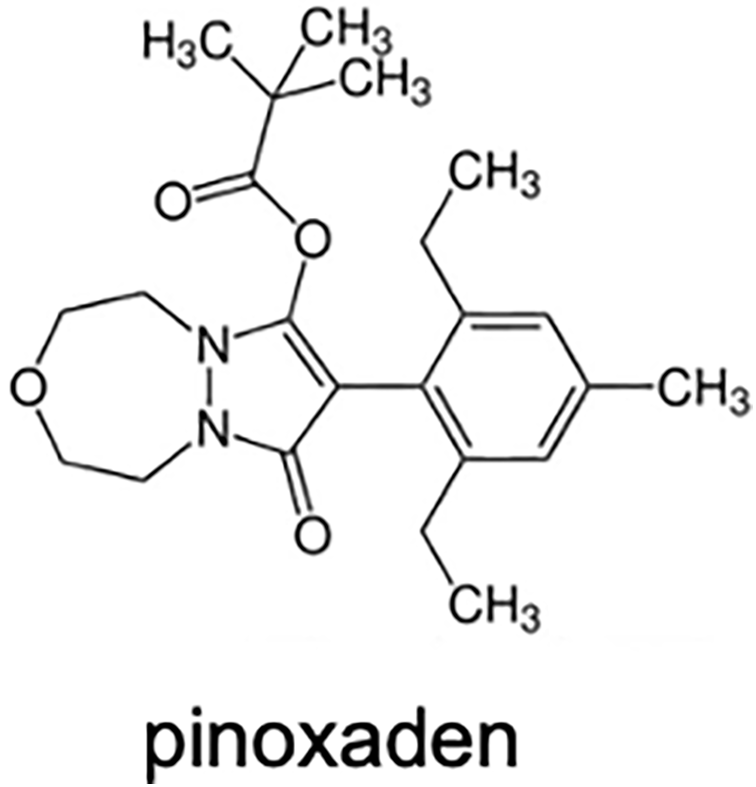

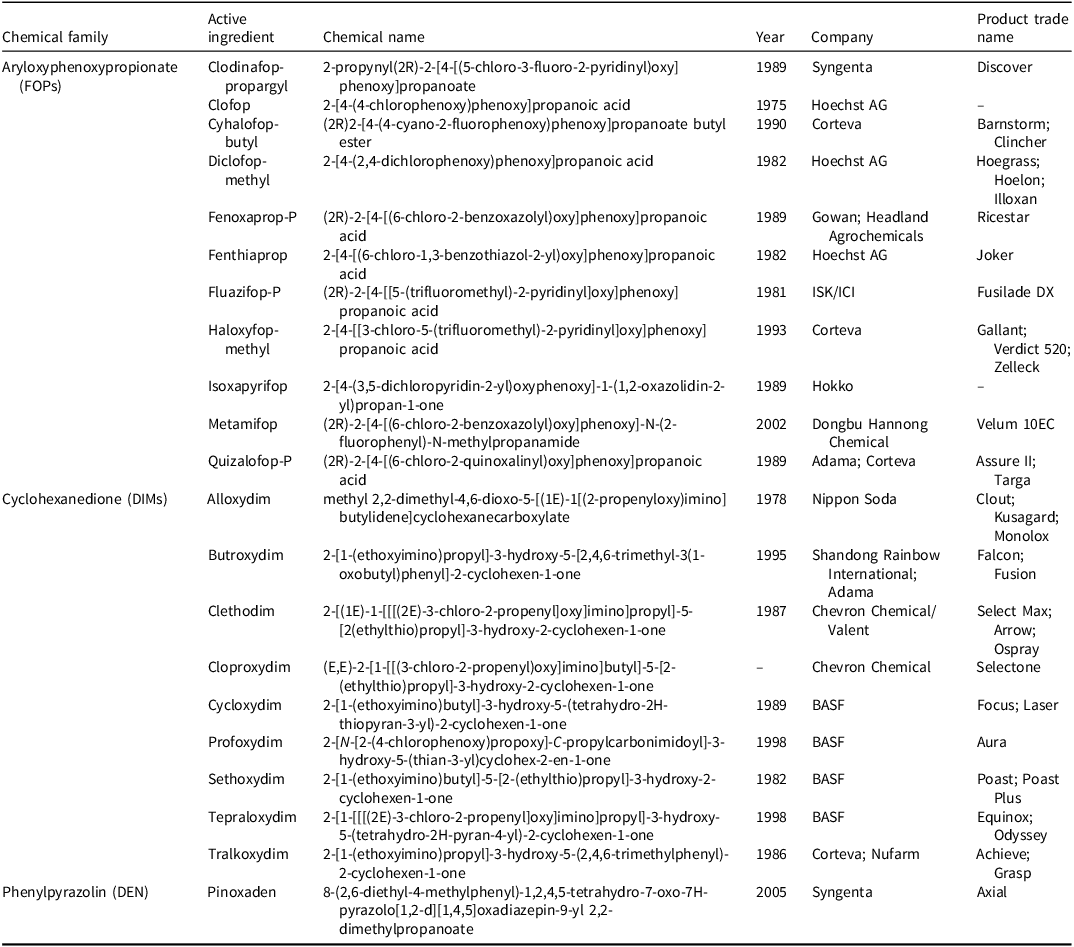

ACCase-inhibiting herbicides are classified into three chemical families: aryloxyphenoxypropionates (AOPPs or commonly known as FOPs; Figure 1), cyclohexanediones (CHDs or commonly known as DIMs; Figure 2), and phenylpyrazolins (PPZs or commonly known as DENs; Figure 3) (Table 1). They are designated as Group 1 (or Group A) herbicides by the Weed Science Society of America and the Herbicide Resistance Action Committee (Mallory-Smith and Retzinger Reference Mallory-Smith and Retzinger2003). While FOPs and DIMs were introduced in the late 1970s and 1980s (Secor et al. Reference Secor, Cseke and Owen1989), the DEN family, consisting of pinoxaden, was launched in 2005 (Hofer et al. Reference Hofer, Muehlebach, Hole and Zoschke2006). Molecules within these chemical groups share a hydrophobic carbon skeleton with polar substituents, though structural variations exist across families (Figures 1, 2, and 3) (Délye Reference Délye2005).

Figure 1. Chemical structure of aryloxyphenoxypropionates (FOPs) herbicides.

Figure 2. Chemical structure of cyclohexanediones (DIMs) herbicides.

Figure 3. Chemical structure of pinoxaden, a phenylpyrazoles (DENs) herbicide.

Table 1. Acetyl-CoA carboxylase-inhibiting herbicide chemical family, active ingredient, chemical name, year discovered/commercialized, company name, and product name.a,b

a Abbreviations: DEN, cyclohexanedione family; DIN, phenylpyrazole family, FOP, aryloxyphenoxypropionate family.

b Sources: https://wssa.net/wssa/weed/herbicides/ (last modified May 5, 2021); Shaner et al. (Reference Shaner, Jachetta, Senseman, Burke, Hanson, Jugulam, Tan, Reynolds, Strek, McAllister, Green, Glenn, Turner and Pawlak2014); Lewis et al. (Reference Lewis, Tzilivakis, Warner and Green2016).

The FOPs are selective postemergence herbicides that primarily target grass weeds in broadleaf crops. These herbicides are commonly formulated as esters to enhance foliar uptake; however, their herbicidal activity is attributed to the carboxylic acid form (Gerwick et al. Reference Gerwick, Jackson, Handly, Gray and Russell1988; Walker et al. Reference Walker, Ridley, Lewis and Harwood1988). Notably, metamifop, a newer FOP herbicide for controlling grass weeds in rice (Oryza sativa L.), is formulated as an amide rather than an ester (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Chang, Kim, Hwang, Hong, Kim, Cho, Myung and Chung2003b). Metamifop is not yet registered for application to crops in the United States. While FOPs exhibit excellent selectivity in broadleaf crops, their application to cereal crops often requires the addition of safeners, such as mefenpyr-ethyl, isoxadifen, or cloquintocet-mexyl, to achieve selectivity in monocots.

The DIMs include herbicides such as sethoxydim and clethodim (Rosinger et al. Reference Rosinger, Bartsch, Schulte, Krämer, Schirmer, Jeschke and Witschel2011; Wenger et al. Reference Wenger, Niderman, Mathews, Wailes, Jeschke, Witschel, Krämer and Schirmer2019). While DIMs and FOPs share the same site of action, inhibition of the ACCase enzyme, their core chemical structures differ fundamentally. The DIMs are cyclohexanedione herbicides, featuring a cyclic diketone structure (a six-membered cyclic diketone). The FOPs are aryloxyphenoxypropionates, featuring an aryl ether and propionate ester structure. Widely used on broadleaf crops such as soybean, cotton (Gossypium hirsutum L.), and oilseed rape (Brassica napus L.), DIMs effectively control grass weeds. However, unlike FOPs, DIMs do not respond favorably to safeners, making selectivity in monocot crops more challenging. Although some DIMs such as tralkoxydim and profoxydim are used on cereals and rice, respectively, their limited success in monocots restricts their broader application.

The DENs include a single commercial herbicide, pinoxaden, which serves postemergence-herbicide-targeting grass weeds in wheat (Triticum aestivum L.) and barley (Hordeum vulgare L.) (Wenger et al. Reference Wenger, Niderman, Mathews, Wailes, Jeschke, Witschel, Krämer and Schirmer2019). Despite extensive research into other DEN compounds, pinoxaden is the only commercial member of this class as of 2025.

The objectives of this review were to summarize 1) the history and use of ACCase-inhibiting herbicides in the United States; 2) ACCase-inhibitor-resistant weeds, their mechanisms of resistance, and management strategies; and 3) the future of ACCase-inhibiting herbicides.

History of ACCase-Inhibiting Herbicides

The history of ACCase-inhibiting herbicides dates back to the late 1970s and early 1980s when agrochemical companies sought to develop herbicides that could be safely applied to broadleaf crops for grass weed control. The discovery process involved extensive screening of various chemical compounds, ultimately leading to the serendipitous identification of FOPs. Shortly after, a second class of ACCase inhibitor, DIMs, was discovered. The introduction of DIMs significantly expanded the applicability of ACCase inhibitors because they provided unique efficacy profiles and broader usage options compared to FOPs.

In 1973, Hoechst AG filed patents on FOPs, claiming the selective herbicidal properties of this chemical group (Table 1; Ye et al. Reference Ye, Wu and Liu2009). Hoechst subsequently developed three related compounds: diclofop, clofop, and trifop (Evans Reference Evans1992). Diclofop and clofop were selective grass herbicides for use on cereal crops, while trifop was intended for controlling grass weeds in broadleaf crops. Of these three compounds, only diclofop-methyl was commercialized (Takano et al. Reference Takano, Ovejero, Belchior, Maymone and Dayan2021) and was first introduced in the United States in 1982 for controlling wild oat (Avena fatua L.) and annual grasses in wheat and barley (Chow Reference Chow1978; Miller and Nalewaja Reference Miller and Nalewaja1980; USEPA 2000a). It was also approved for controlling goosegrass [Eleusine indica (L.) Gaertn.], also known as silver crabgrass, in established golf courses (USEPA 2000b). Diclofop-methyl was marketed under the trade names Hoegrass EC 500, Hoelon, and Illoxan (Shaner et al. Reference Shaner, Jachetta, Senseman, Burke, Hanson, Jugulam, Tan, Reynolds, Strek, McAllister, Green, Glenn, Turner and Pawlak2014; Table 1). The R-enantiomer, diclofop-P-methyl, exhibits greater ACCase inhibition than the S-enantiomer; the R-enantiomer was introduced in 2005 (Székács Reference Székács, Mesnage and Zaller2021; Ye et al. Reference Ye, Wu and Liu2009). Quizalofop-P-ethyl was registered for use on soybean crops in the late 1980s and on cotton crops in the early 1990s (Shaner et al. Reference Shaner, Jachetta, Senseman, Burke, Hanson, Jugulam, Tan, Reynolds, Strek, McAllister, Green, Glenn, Turner and Pawlak2014).

Fluazifop-butyl, another FOP herbicide, was discovered by Ishihara Sankyo Kaisha and subsequently cross-patented by Kaisha and the plant protection division of Imperial Chemical Industries (now Syngenta AG). Fluazifop-butyl and its R-enantiomer, fluazifop-P-butyl, were commercialized in the early 1980s (Hong Reference Hong and Petrov2009; Székács Reference Székács, Mesnage and Zaller2021). Fluazifop-P-butyl, initially marketed under the trade name Fusilade, is widely used for postemergence control of perennial and annual grass weeds in broadleaf crops (Syngenta 2019b).

Since 1972, companies have been evaluating the herbicidal properties of cyclohexane-1,3-dione derivatives. Alloxydim-sodium was the pioneering DIM herbicide, discovered and commercialized by Nippon Soda in 1978 (Iwataki Reference Iwataki, Draber and Fujita1992; Sevilla-Morán et al. Reference Sevilla-Morán, López-Goti, Alonso-Prados, Sandín-España, Proce and Kelton2013). Sethoxydim, discovered by Nippon Soda Co Ltd, was the second herbicide from this group, later developed by BASF and commercialized as Poast in the United States in 1982 (Shaner et al. Reference Shaner, Jachetta, Senseman, Burke, Hanson, Jugulam, Tan, Reynolds, Strek, McAllister, Green, Glenn, Turner and Pawlak2014; USEPA 1982). Another widely used DIM herbicide, clethodim, was patented by Chevron Chemical Company in Great Britain in 1987 (Durkin Reference Durkin2014). In the United States, the patent was held by Valent Biosciences Corporation. Since the patent expired, several chemical companies have begun marketing clethodim (Zollinger and Howatt Reference Zollinger and Howatt2005). Profoxydim, introduced by BASF in 1998, was among the last DIM herbicides to reach the market (Cobos-Escudero et al. Reference Cobos-Escudero, Pla, Cervantes-Diaz, Alonso-Prados, Sandin-España, Alcamí and Lamsabhi2024; Lewis et al. Reference Lewis, Tzilivakis, Warner and Green2016). Pinoxaden (trade name Axial), a unique ACCase inhibitor distinct from FOPs and DIMs, belonging to the DEN family, was commercialized by Syngenta in 2005 for grass weed control in small grain cereal crops (Kaundun Reference Kaundun2021; USEPA 2005). Pinoxaden was commercialized for selective control of grass weeds such as blackgrass (Alopecurus myosuroides Huds.), canary grass (Phalaris canariensis L.), foxtails (Setaria spp.), ryegrass (Lolium spp.), silky windgrass [Apera spica-venti (L.) Beauv.], and wild oat in wheat and barley. It is an effective herbicide with a field use rate of 30 to 60 g ha‒1 and a wide application window, extending from early to late postemergence (Singh et al. Reference Singh, Maity, Abugho, Swart, Drake and Bagavathiannan2020). Weed control efficacy and crop safety are further enhanced by the addition of methylated rapeseed oil-based adjuvants and the safener cloquintocet-mexyl (Muehlebach et al. Reference Muehlebach, Boeger, Cederbaum, Cornes, Friedmann, Glock, Niderman, Stoller and Wagner2009, Reference Muehlebach, Cederbaum, Cornes, Friedmann, Glock, Hall, Indolese, Kloer, Le Goupil, Maetzke, Meier, Schneider, Stoller, Szczepanski, Wendeborn and Widmer2011).

Use of ACCase-Inhibiting Herbicides

Aryloxyphenoxypropionates (FOPs)

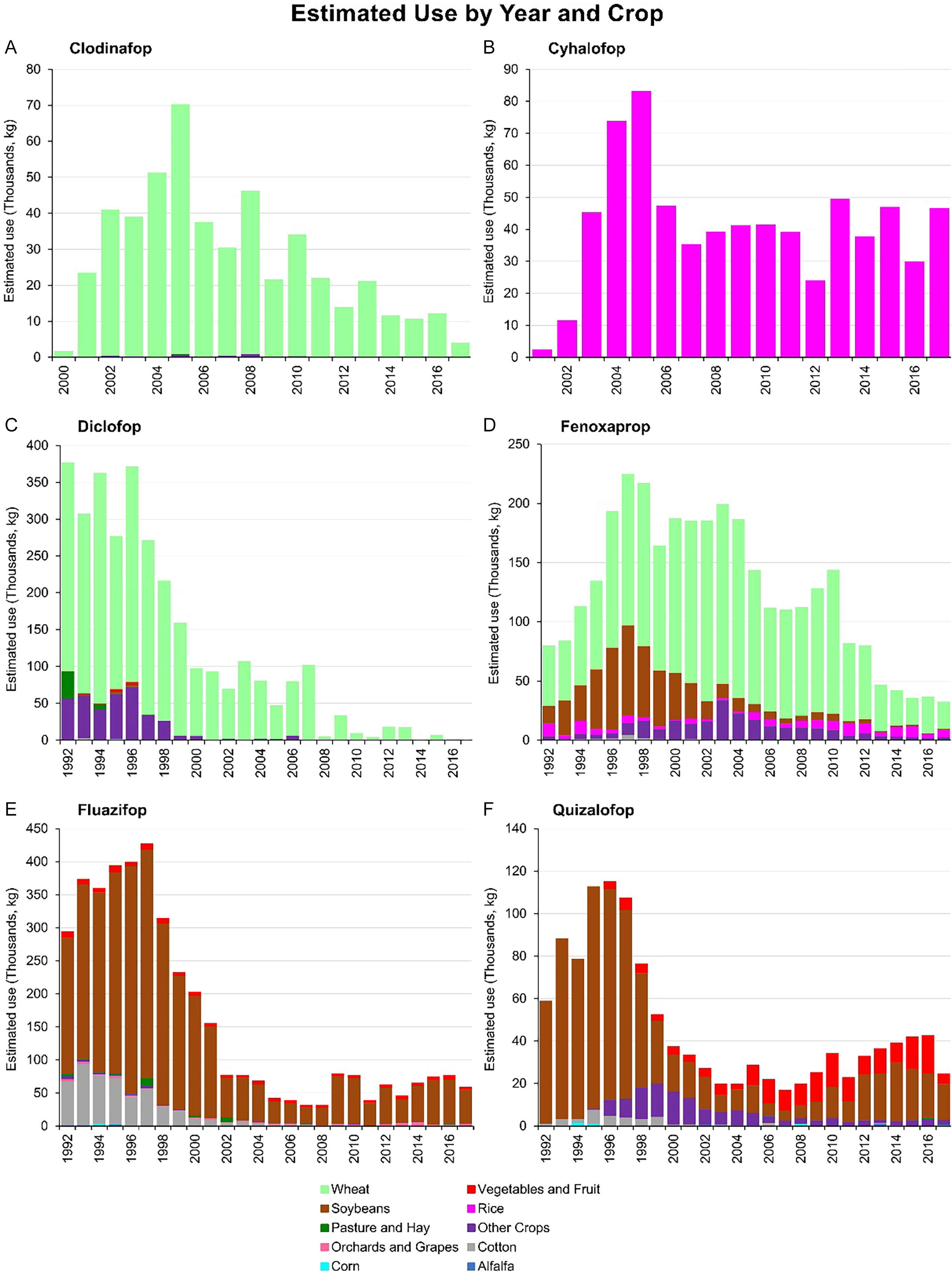

Clodinafop-propargyl. Clodinafop-propargyl is used to control grass weeds in wheat, including volunteer wheat and wild oat, barnyardgrass [Echinochloa crus-galli (L.) P. Beauv.], Persian darnel (Lolium persicum Boiss. & Hohen.), foxtails, canary grass, and annual bluegrass (Poa annua L.) (Syngenta 2019a; Shaner et al. Reference Shaner, Jachetta, Senseman, Burke, Hanson, Jugulam, Tan, Reynolds, Strek, McAllister, Green, Glenn, Turner and Pawlak2014). The total annual use of clodinafop-propargyl in the United States was reported to be 1,726 kg in 2000, peaking at 70,327 kg in 2005 (Figure 4A). However, its use gradually declined, reaching 4,070 kg in 2017. A survey in 2022 by the U.S. Department of Agriculture reported that 4,082 kg of clodinafop-propargyl was applied to 4% of the area planted with durum wheat (Triticum durum Desf.) in the United States (USDA-NASS 2023a).

Figure 4. The estimated use by year and crop of A) clodinafop, B) cyhalofop, C) diclofop, D) fenoxaprop, E) fluazifop, and F) quizalofop in the United States. The pesticide use data (low estimates) were downloaded from Wieben (Reference Wieben2019). The graphs were adapted from USGS (2018).

Cyhalofop-butyl. Dow AgroSciences LLC registered cyhalofop-butyl for use on rice crops in the United States in 2002 (USEPA 2002). Corteva Agrisciences now produces the herbicide under the trade name Clincher CA. It is used for selective postemergence control of grass weeds, including barnyardgrass, broadleaf signalgrass [Urochloa platyphylla (Munro ex C. Wright) R.D. Webster], junglerice [Echinochloa colona (L.) Link], large crabgrass [Digitaria sanguinalis (L.) Scop.], and red sprangletop [Dinebra panicea (Retz.) P. M. Peterson & N. Snow] in both dry-seeded and water-seeded rice (Corteva Corteva, 2022). In 2002, a total of 11,641 kg of cyhalofop-butyl was applied to crops in the United States, with usage peaking at 83,251 kg in 2005 (Figure 4B). Between 2006 and 2017, annual usage ranged from 24,025 to 49,546 kg. The most recent survey reported that 48,988 kg of cyhalofop-butyl was applied to 14% of the rice-planted area in the United States in 2021, with an average application rate of 325 g ha⁻1 (USDA-NASS 2022).

Diclofop-methyl. The highest recorded total annual use of diclofop-methyl in the United States was 377,153 kg in 1992, exceeding 250,000 kg per year until 1997 (Figure 4C). However, its application declined thereafter, ranging between 5,216 kg and 107,301 kg annually during the first decade of the 21st century. More recently, its use has decreased substantially, dropping to less than 7,000 kg per year after 2013. By 2017, only 337 kg of diclofop-methyl was applied to wheat. Diclofop-methyl was discontinued in the United States in 2018 following a voluntary request by Bayer Crop Science and Bayer Environmental Science to cancel the registration of products containing this herbicide (Federal Register 2015).

Fenoxaprop-ethyl. Fenoxaprop-ethyl is a postemergence herbicide used for controlling grass weeds in soybean, turf, wheat, barley, rice, cotton, vegetables, and other crops (NCBI 2024; USEPA 1988). The total annual use of fenoxaprop-ethyl in the United States was reported to be 79,813 kg in 1992, progressively increasing each year to a peak of 224,920 kg in 1997 (Figure 4D). Usage remained greater than 150,000 kg per year until 2004 and greater than 100,000 kg per year until 2010. However, its use steadily declined from 81,883 kg in 2011 to 32,458 kg in 2017. Fenoxaprop-ethyl was primarily applied to wheat crops, followed by soybean (1992–2001), other crops (2002–2010), and rice (2011–2017). In 2022, 3,175 kg of fenoxaprop-P-ethyl was reported to have been applied to 6% of the area planted with durum wheat (USDA-NASS 2023a), and 10,886 kg was applied to 7% of the area planted with other spring wheat (USDA-NASS 2023b).

Fluazifop-butyl. Fluazifop-butyl is a postemergence herbicide used for controlling annual and perennial grasses, including barnyardgrass, broadleaf signalgrass, crabgrass, downy brome (Bromus tectorum L.), fall panicum (Panicum dichotomiflorum Michx.), Texas panicum [Urochloa texana (Buckley) R. Webster], field sandbur (Cenchrus spinifex Cav.), foxtail, goosegrass, Italian ryegrass [Lolium perenne L. ssp. multiflorum (Lam.) Husnot], johnsongrass [Sorghum halepense (L.) Pers.], quackgrass (Elymus repens L. Gould), volunteer cereals, and wild oat (Shaner et al. Reference Shaner, Jachetta, Senseman, Burke, Hanson, Jugulam, Tan, Reynolds, Strek, McAllister, Green, Glenn, Turner and Pawlak2014; Syngenta 2019a). Fluazifop-butyl can be applied to crops such as cotton, soybean, dry bean (Phaseolus vulgaris L.), asparagus (Asparagus officinalis L.), banana (Musa L.), peanut (Arachis hypogaea L.), pecan (Carya illinoinensis Wangenh. K. Koch), stone fruits, sugar beet (Beta vulgaris L.), and plantation crops (Shaner et al. Reference Shaner, Jachetta, Senseman, Burke, Hanson, Jugulam, Tan, Reynolds, Strek, McAllister, Green, Glenn, Turner and Pawlak2014; Syngenta 2024). It is also approved for application to turf and ornamental plants (Syngenta 2016). The total annual use of fluazifop-butyl in the United States was reported at 294,405 kg in 1992, peaking at 427,422 kg in 1997 (Figure 4E). After this peak, its use progressively declined, reaching 32,389 kg in 2008. However, in 2017, annual usage increased to 59,578 kg. Fluazifop-butyl is predominantly applied in soybean cultivation. In 2023, a total of 82,100 kg was used on 2% of the soybean-planted area in the United States, with an average application rate of 146 g ha⁻1 (USDA-NASS 2024).

Quizalofop-P-ethyl. Quizalofop is a postemergence herbicide used to control annual and perennial grass weeds in broadleaf crops such as soybean and cotton. Quizalofop-resistant crops have been developed such as Enlist corn (Zea mays L.), Fullpage and Provisia rice, Co-axium wheat, and Double Team sorghum (AMVAC 2021; Lancaster et al. Reference Lancaster, Norsworthy and Scott2018). In the United States, quizalofop usage was reported at 58,977 kg in 1992, reaching its highest recorded use of 115,146 kg in 1996 (Figure 4F). Between 2000 and 2017, annual usage remained less than 43,000 kg. Quizalofop is primarily applied to soybean crops, with 9,072 kg reported to have been used on soybean fields in 2020 (USDA-NASS 2021).

Cyclohexanediones (DIMs)

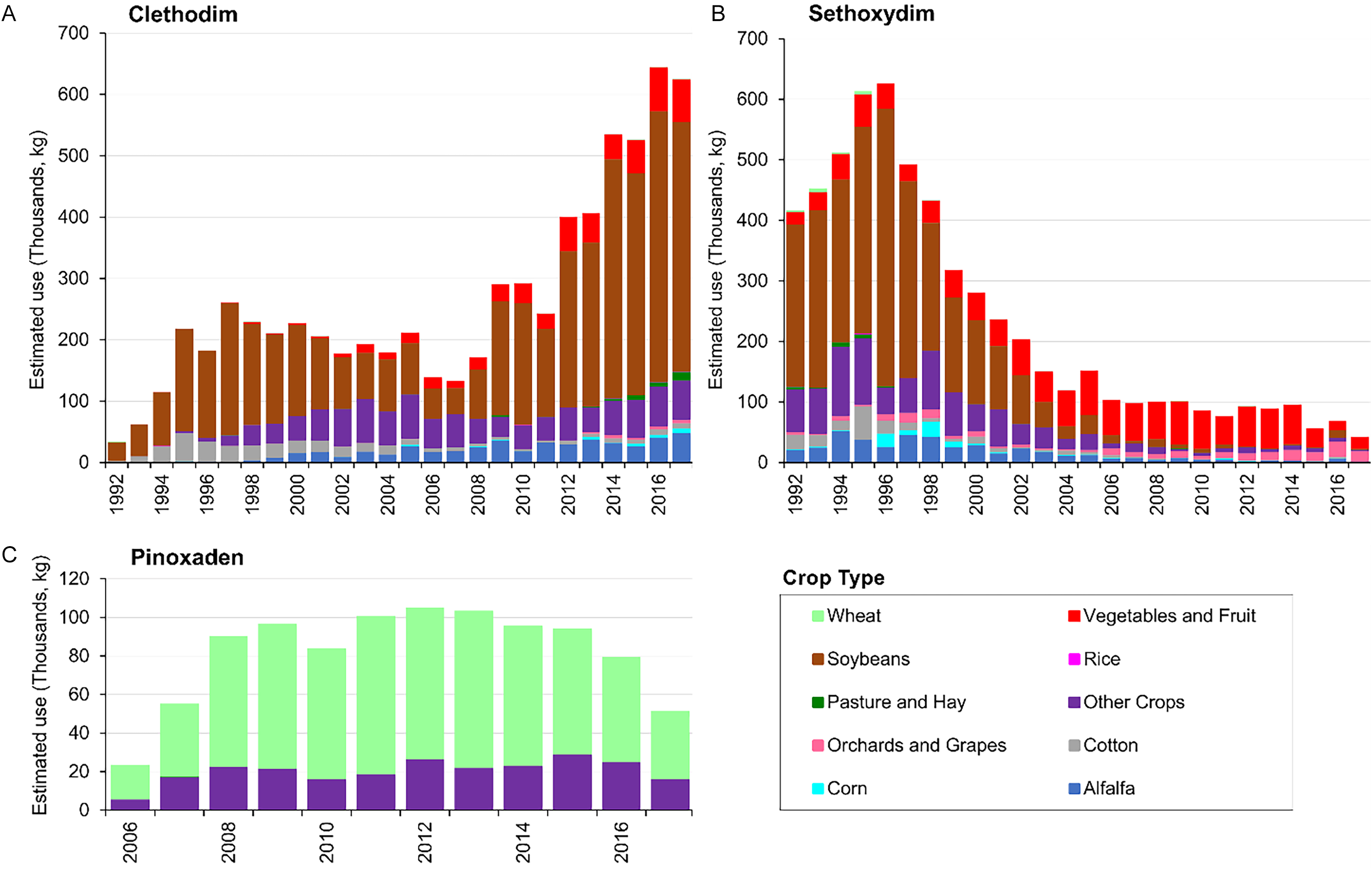

Clethodim. Clethodim is a selective postemergence herbicide used for grass weed control in soybean, cotton, alfalfa (Medicago sativa L.), peanut, sugar beet, and various other broadleaf crops (Valent 2021). The total annual use of clethodim in the United States was at its lowest in 1992, with 34,009 kg applied (Figure 5A). However, its usage increased significantly over the years, exceeding 625,000 kg by 2016 and 2017—an 18- to 19-fold increase compared with 1992. The highest quantity of clethodim was consistently applied to soybean. Notably, in 2018, clethodim usage on soybean alone (634,122 kg at an application rate of 123 g ha⁻1 yr⁻1, covering 15% of the soybean-planted area) exceeded the total amount used across all other crops in 2017 (625,597 kg) (USDA-NASS 2019). This trend continued, with clethodim usage in soybean production increasing to 724,387 kg (134 g ha⁻1 yr⁻1; 17% of the planted area) in 2020, and more recently to 920,339 kg (179 g ha⁻1 yr⁻1; 16% of the planted area) in 2023 (USDA-NASS 2021, 2024).

Figure 5. The estimated use by year and crop of A) clethodim, B) sethoxydim, and C) pinoxaden, in the United States. The pesticide use data (low estimates) were downloaded from Wieben (Reference Wieben2019). The graphs were adapted from USGS (2018).

Sethoxydim. Sethoxydim is a selective postemergence herbicide used on soybean, peanut, alfalfa, cotton, carrot (Daucus carota L. var. sativus Hoffm.), dry bean, sugar beet, sunflower (Helianthus annuus L.), certain fruits and vegetables, nonagricultural land, and other crops (BASF 2020). Sethoxydim usage in the United States reached 416,354 kg in 1992, increasing to a peak of 626,058 kg in 1996 (Figure 5B). However, after this peak, its use declined steadily, dropping to 119,472 kg in 2004. From 2005 onward, annual usage remained less than 103,000 kg until 2017. Although sethoxydim was predominantly used on soybean crops until 2002, its primary application shifted to vegetables and fruit crops in subsequent years.

Phenylpyrazolin (DENs)

Pinoxaden. Pinoxaden was initially granted conditional registration in the United States in July 2005 for postemergence grass weed control in wheat and barley (Syngenta 2022; USEPA 2005). In 2006, the total annual use of pinoxaden in the United States was 23,627 kg (Figure 5C). The annual amount increased to 55,248 kg in 2007 and remained above 80,000 kg per year until 2015. However, usage declined to 79,717 kg in 2016 and further to 51,565 kg in 2017. From 2006 to 2017, wheat accounted for 69% to 81% of total pinoxaden usage. In 2022, 8,618 kg of pinoxaden was applied to winter wheat at an average rate of 45 g ha⁻1 yr⁻1, covering 2% of the planted area. Additionally, 42,638 kg was used on spring wheat (excluding durum wheat) at an average rate of 56 g ha⁻1 yr⁻1, covering 17% of the planted area (USDA-NASS 2023b, 2023c).

Interaction of ACCase Inhibitors with Other Herbicides

ACCase-inhibiting herbicides are commonly mixed with other herbicides to achieve broad-spectrum weed control or enhance efficacy. However, such combinations can result in additive, antagonistic, or synergistic effects on grass weed control. When mixed herbicides provide similar control to their independent applications, the effect is considered additive (Colby Reference Colby1967). If weed control exceeds the sum of individual effects, the interaction is synergistic, a desirable outcome (de Sanctis and Jhala 2021). Conversely, if weed control is lower than expected, the interaction is antagonistic, which is an undesirable outcome (Singh et al. Reference Singh, Kumar, Knezevic, Irmak, Lindquist, Pitla and Jhala2023).

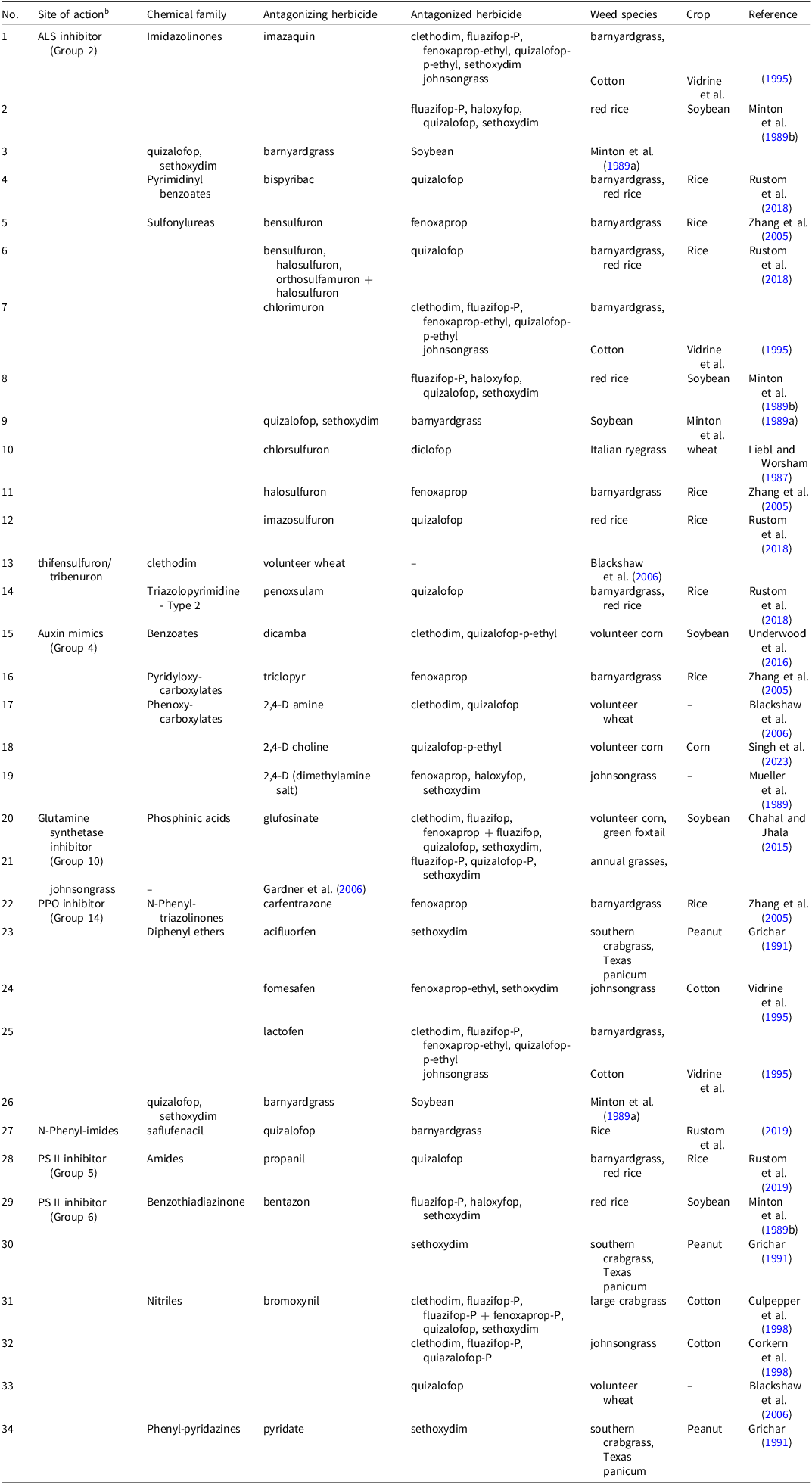

Unfortunately, ACCase inhibitors are frequently antagonized by auxin mimic herbicides (Blackshaw et al. Reference Blackshaw, Harker, Clayton and O’Donovan2006; Lancaster et al. Reference Lancaster, Norsworthy, Scott, Gbur and Norman2019; Mueller et al. Reference Mueller, Witt and Barrett1989; Singh et al. Reference Singh, Kumar, Knezevic, Irmak, Lindquist, Pitla and Jhala2023; Underwood et al. Reference Underwood, Soltani, Hooker, Robinson, Vink, Swanton and Sikkema2016; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Webster, Blouin and Leon2005). Other herbicide groups reported to antagonize ACCase inhibitors include inhibitors of acetolactate synthase (ALS) (Blackshaw et al. Reference Blackshaw, Harker, Clayton and O’Donovan2006; Lancaster et al. Reference Lancaster, Norsworthy, Scott, Gbur and Norman2019; Liebl and Worsham Reference Liebl and Worsham1987; Minton et al. Reference Minton, Kurtz and Shaw1989a, 1989b; Rustom et al. Reference Rustom, Webster, Blouin and McKnight2018; Vidrine et al. Reference Vidrine, Reynolds and Blouin1995; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Webster, Blouin and Leon2005), the glutamine synthetase inhibitor glufosinate (Chahal and Jhala Reference Chahal and Jhala2015; Gardner et al. Reference Gardner, York, Jordan and Monks2006), photosystem II (PS II) inhibitors (Blackshaw et al. Reference Blackshaw, Harker, Clayton and O’Donovan2006; Corkern et al. Reference Corkern, Reynolds, Vidrine, Griffin and Jordan1998; Culpepper et al. Reference Culpepper, York, Jennings and Batts1998; Grichar Reference Grichar1991; Minton et al. Reference Minton, Shaw and Kurtz1989b; Rustom et al. Reference Rustom, Webster, Blouin and McKnight2019), and protoporphyrinogen oxidase (PPO) inhibitors (Grichar Reference Grichar1991; Minton et al. Reference Minton, Kurtz and Shaw1989a; Rustom et al. Reference Rustom, Webster, Blouin and McKnight2019; Vidrine et al. Reference Vidrine, Reynolds and Blouin1995; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Webster, Blouin and Leon2005) (Table 2). Glyphosate has been reported to antagonize or synergize ACCase inhibitors. Harre et al. (Reference Harre, Young and Young2020) found that glyphosate reduced clethodim efficacy (35 and 70 g ha–1) by 61% for control of glyphosate-resistant volunteer corn. Interestingly, they observed an additive interaction between dicamba and clethodim when applied in a mixture but an antagonistic effect when glyphosate was included in the mix. The frequent reports of antagonism involving ACCase inhibitors are likely due to their unique selective grass weed control properties. Additionally, they are widely used postemergence herbicides in mixtures with broadleaf herbicides for broad-spectrum weed management in many agronomic crops (Barbieri et al. Reference Barbieri, Young, Dayan, Streibig, Takano, Merotto and Avila2023; Leise et al. Reference Leise, Singh, LaMenza, Knezevic and Jhala2025; Singh et al. Reference Singh, Kumar, Knezevic, Irmak, Lindquist, Pitla and Jhala2023).

Table 2. A list of interaction of acetyl-CoA carboxylase inhibitors when mixed with other herbicides. a

a Abbreviations: ALS, acetolactate synthase; PPO, protoporphyrinogen oxidase; PS II, photosystem II.

b Herbicide are categorized into groups by the Herbicide Resistance Action Committee and Weed Science Society of America.

The interaction between ACCase-inhibiting herbicides and other herbicides can be weed-specific. The response may also vary with the weed growth stage. Minton et al. (Reference Minton, Shaw and Kurtz1989b) observed that chlorimuron (9 g ha–1) antagonized quizalofop (28 g ha–1) when applied to 5- to 6-leaf stage red rice (29% vs. 44%) but had a neutral effect when applied at the 2- to 3-leaf stage (70% vs. 83%) at 7 d after treatment (DAT). However, by 21 DAT, the interaction became additive for rice at both the 2- to 3-leaf stage (84% vs. 91%) and the 5- to 6-leaf stage (63% vs. 74%). Additionally, herbicide formulations can influence interactions. Blackshaw et al. (Reference Blackshaw, Harker, Clayton and O’Donovan2006) reported that 2,4-D amine was more antagonistic than 2,4-D ester when mixed with clethodim or quizalofop for volunteer wheat control (Table 2).

While antagonism is a common concern, synergism between ACCase inhibitors and other herbicides has been reported. For example, Minton et al. (Reference Minton, Shaw and Kurtz1989b) observed synergism between acifluorfen and fluazifop, haloxyfop, and sethoxydim for controlling red rice in soybean. Similarly, Harker and O’Sullivan (Reference Harker and O’Sullivan1991) documented synergistic interactions between fluazifop and sethoxydim for controlling annual grasses.

Several factors have been reported in the literature as causes of antagonism by ACCase-inhibiting herbicides. These include reduced uptake and/or translocation (Baerg et al. Reference Baerg, Gronwald, Eberlein and Stucker1996; Culpepper et al. Reference Culpepper, York, Jordan, Corbin and Sheldon1999; Ferreira et al. Reference Ferreira, Burton and Coble1995; Gerwick Reference Gerwick1988; Mueller et al. Reference Mueller, Barrett and Witt1990; Olson and Nalewaja Reference Olson and Nalewaja1982; Qureshi and Born Reference Qureshi and Born1979; Young et al. Reference Young, Hart and Wax1996), altered metabolism (either reduced or increased) (Han et al. Reference Han, Yu, Cawthray and Powles2013; Ottis et al. Reference Ottis, Mattice and Talbert2005), decreased photosynthetic rates (Burke and Wilcut Reference Burke and Wilcut2003), chemical interactions with other herbicides (Wanamarta et al. Reference Wanamarta, Penner and Kells1989), and the anti-auxin role of ACCase inhibitors (Barnwell and Cobb Reference Barnwell and Cobb1993).

Because antagonism of ACCase inhibitors can result in reduced or failed grass control, a few strategies are recommended to minimize or eliminate this issue:

-

Increase the rate of ACCase inhibitors, within label limits (Mueller et al. Reference Mueller, Witt and Barrett1989; Singh et al. Reference Singh, Kumar, Knezevic, Irmak, Lindquist, Pitla and Jhala2023; Underwood et al. Reference Underwood, Soltani, Hooker, Robinson, Vink, Swanton and Sikkema2016).

-

Separate applications of the ACCase inhibitor and broadleaf herbicides by 3 to 7 d (Burke et al. Reference Burke, Askew, Corbett and Wilcut2005; Corkern et al. Reference Corkern, Reynolds, Vidrine, Griffin and Jordan1998; Culpepper et al. Reference Culpepper, York, Jennings and Batts1998; Gardner et al. Reference Gardner, York, Jordan and Monks2006).

-

Use more effective or activator adjuvants (Harre et al. Reference Harre, Young and Young2020; Kammler et al. Reference Kammler, Walters and Young2010).

-

Apply herbicides when grass weeds are at early growth stages (Burke et al. Reference Burke, Askew, Corbett and Wilcut2005; Minton et al. Reference Minton, Shaw and Kurtz1989b).

-

Use sequential applications rather than tank mixes (Singh et al. Reference Singh, Kumar, Knezevic, Irmak, Lindquist, Pitla and Jhala2023; Leise et al. Reference Leise, Singh, LaMenza, Knezevic and Jhala2025). Note that ACCase inhibitor rates cannot exceed the maximum labeled rate per application or cumulative rate per year.

-

Apply an ACCase inhibitor and broadleaf herbicide simultaneously through separate tank and boom systems (Merritt et al. Reference Merritt, Ferguson, Brown-Johnson, Reynolds, Tseng and Lowe2020; Leise et al. Reference Leise, Singh, LaMenza, Knezevic and Jhala2025).

ACCase Inhibitor-Resistant Weeds and Their Mechanism of Resistance

The ACCase-inhibiting herbicides are an effective option for postemergence control of monocot weeds, particularly those that are resistant to glyphosate. However, exclusive reliance on these herbicides accelerates the evolution of ACCase inhibitor-resistant weeds (Devine Reference Devine, Hirai, Wakabayashi and Boger2002; Vidal and Fleck Reference Vidal and Fleck1997). The first documented case of resistance to an ACCase inhibitor occurred in 1982 in rigid ryegrass (Lolium rigidum Gaud.) in an Australian wheat field (Heap and Knight Reference Heap and Knight1982). As of April 2025, a total of 51 grass weed species worldwide have been documented as being resistant to ACCase-inhibiting herbicides, including 16 in the United States (Heap Reference Heap2025). Notably, some Australian rigid ryegrass biotypes were found to have resistance to pinoxaden before it was commercially released in 2006 (Boutsalis et al. Reference Boutsalis, Broster and Preston2012). Resistance mechanisms in ACCase inhibitor-resistant weed biotypes include target site and non–target site mechanisms. These mechanisms have been comprehensively reviewed by Takano et al. (Reference Takano, Ovejero, Belchior, Maymone and Dayan2021); therefore, this review focuses on documented important cases of ACCase-inhibitor resistance in weed species.

Target Site Resistance to ACCase-Inhibiting Herbicides

Target-site mutations in the ACCase gene, leading to amino acid substitutions, are a common resistance mechanism to ACCase-inhibiting herbicides in several grass weeds. However, the first reported case of ACCase gene amplification-based target site resistance was identified in large crabgrass (Laforest et al. Reference Laforest, Soufiane, Simard, Obeid, Page and Nurse2017). In a goosegrass biotype, two ACCase gene mutations conferred cross-resistance to FOPs, DIMs, and DENs (McCullough et al. Reference McCullough, Yu, Raymer and Chen2016). The Asp-2078-Gly substitution was the primary resistance mechanism, while Thr-1805-Ser was also present but had a lesser effect (McCullough et al. Reference McCullough, Yu, Raymer and Chen2016). Similarly, cross-resistance due to target site mutations has been reported in southern crabgrass [Digitaria ciliaris (Retz.) Koeler], a problematic turfgrass weed (Basak et al. Reference Basak, McElroy, Brown, Gonçalves, Patel and McCullough2020). The Ile-1781-Leu substitution conferred high-level resistance by altering the carboxyl transferase domain of the plastidic ACCase enzyme, reducing herbicide sensitivity (Basak et al. Reference Basak, McElroy, Brown, Gonçalves, Patel and McCullough2020).

The first documented case of ACCase-inhibitor resistance (up to 36-fold) in downy brome was reported in Oregon in the United States (Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Brunharo, Mallory-Smith, Walenta and Barroso2023). Resistant plants exhibited Ile-2041-Thr and Gly-2096-Ala mutations, conferring resistance to FOPs and DIMs (Ribeiro et al. Reference Ribeiro, Brunharo, Mallory-Smith, Walenta and Barroso2023). Similar resistance cases have been reported in Italian ryegrass in the United States. Tehranchian et al. (Reference Tehranchian, Nandula, Jugulam, Putta and Jasieniuk2018) documented high-level cross-resistance (>120-fold) due to mutations at position 1,781. Martins et al. (2014) identified the Asp-2078-Gly mutation in Oregon populations, providing a high level of resistance to multiple ACCase-inhibiting herbicides. Some plants also carried the Ile-2041-Asn mutation, which confers moderate-level resistance to clethodim and sethoxydim. Depetris et al. (Reference Depetris, Muñiz Padilla, Ayala, Tuesca and Breccia2024) found Italian ryegrass populations with the Ile-2041-Asn mutation that conferred high-level resistance to FOPs, moderate-level resistance to DENs, but susceptibility to DIMs.

Barnyardgrass populations with multiple ACCase-inhibitor resistance due to target site mutations, including Ile-1781-Leu and Asp-2078-Gly, have been reported (Amaro-Blanco et al. Reference Amaro-Blanco, Romano, Palmerin, Gordo, Palma-Bautista, De Prado and Osuna2021; Fang et al. Reference Fang, He, Liu, Li and Dong2020). In American sloughgrass [Beckmannia syzigachne (Steud.) Femald], resistance has been linked to several ACCase gene mutations. Trp-2027-Cys in the carboxyltransferase domain conferred resistance to multiple ACCase-inhibiting herbicides (Li et al. Reference Li, Du, Liu, Yuan and Wang2014). Ile-1781-Leu and Asp-2078-Gly provided broad-spectrum resistance, including to DIMs. Trp-2027-Cys and Ile-2041-Asn conferred resistance mainly to FOPs and DENs (pinoxaden), with low-level resistance to DIMs. Gly-2096-Ala resulted in high-level resistance to FOPs but moderate-level resistance to DIMs and pinoxaden (Du et al. Reference Du, Liu, Yuan, Guo, Li and Wang2016).

Wild oat populations with target site resistance to ACCase-inhibiting herbicides have been documented. A biotype from Chile with the Asp-2078-Gly mutation conferred resistance to FOPs, DIMs, and DENs. A biotype from Mexico with the Ile-2041-Asn mutation exhibited resistance to FOPs and DIMs but remained susceptible to DENs (pinoxaden) (Cruz-Hipolito et al. Reference Cruz-Hipolito, Osuna, Domínguez-Valenzuela, Espinoza and De Prado2011). In winter wild oat (Avena sterilis subsp. ludoviciana) from Iran, the Ile-2041-Asn substitution conferred cross-resistance to multiple ACCase inhibitors (Hassanpour-Bourkheili et al. Reference Hassanpour-Bourkheili, Gherekhloo, Kamkar and Ramezanpour2021). Smooth barley (Hordeum glaucum Steud.) populations from southern Australia exhibited TS resistance:

-

Ile-1781-Leu conferred high-level resistance to FOPs;

-

Ile-2041-Asn provided moderate resistance to FOPs and lower-level resistance to clethodim; and

-

Gly-2096-Ala, found in one population, showed moderate level resistance to FOPs (Shergill et al. Reference Shergill, Malone, Boutsalis, Preston and Gill2017).

Blackgrass populations have evolved various target site mutations. A novel Ile-1781-Thr mutation conferred low-level resistance to FOPs, DIMs, and DENs (Délye et al. Reference Délye, Zhang, Chalopin, Michel and Powles2005). Ile-1781-Leu conferred high cross-resistance to multiple ACCase-inhibiting herbicides (Délye Reference Délye2005; Kaundun et al. Reference Kaundun, Hutchings, Dale, Baily and Glanfield2011).

Recently, cross-resistance to ACCase inhibitors due to the Trp-2027-Cys mutation was reported in sourgrass [Digitaria insularis (L.) Mez ex Ekman] populations from Brazil (Takano et al. 2020). That study suggested that replacing tryptophan (a hydrophobic amino acid) with cysteine (a polar amino acid) alters the binding pocket’s physical properties. This modification disrupts the hydrophobic interaction required for FOP herbicide (e.g., haloxyfop) binding, rendering it ineffective. However, DIMs (e.g., clethodim) remain effective because their binding is unaffected (Takano et al. 2020).

The first case of target site resistance to sethoxydim due to ACCase gene amplification and overexpression was reported in a large crabgrass population (Laforest et al. Reference Laforest, Soufiane, Simard, Obeid, Page and Nurse2017). This marked the second known example of herbicide target gene amplification-based resistance, following glyphosate resistance. The resistant biotype exhibited a 5- to 7-fold increase in ACCase gene copy number and a 3- to 9-fold increase in ACCase transcript level compared to a susceptible biotype (Laforest et al. Reference Laforest, Soufiane, Simard, Obeid, Page and Nurse2017).

Non–Target Site Weed Resistance to ACCase-Inhibiting Herbicides

While target site resistance is widespread in ACCase inhibitor-resistant weeds, several cases of metabolic resistance to these herbicides have been reported. In silky windgrass, transcriptomic analyses identified the upregulation of genes involved in herbicide detoxification, including UDP-glucosyltransferases (UGT75K6, UGT75E2) and glutathione-S-transferases (GSTU1, GSTU6), suggesting that metabolic resistance predominates in this species (Wrzesinska-Krupa et al. Reference Wrzesinska-Krupa, Szmatola, Praczyk and Obrepalska-Steplowska2023). Similarly, indirect enzyme-inhibition assays using malathion (a cytochrome P450 [CYP] inhibitor) and 7-chloro-4-nitrobenz-2-oxa-1,3-diazole (NBD-Cl) (a glutathione S-transferase [GST] inhibitor) revealed increased sensitivity in E. phyllopogon and E. crus-galli populations, indicating metabolic resistance to metamifop (Sun et al. Reference Sun, Niu, Lan, Yu, Cui, Chen and Li2023; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Wang, Du, Deng, Bai and Ji2023).

Direct evidence of CYP involvement in metabolic resistance to ACCase inhibitors has been documented in Echinochloa spp. In cyhalofop-butyl-resistant barnyardgrass, CYP81A21 expression was 2.5 times higher in resistant plants than in susceptible ones (González-Torralva and Norsworthy Reference González-Torralva and Norsworthy2024). RNA sequence analysis confirmed increased expression of CYP81A68 in resistant barnyardgrass (Pan et al. Reference Pan, Guo, Wang, Shi, Yang, Zhou, Yu and Bai2022). Transcriptomic studies of Japanese foxtail (Alopecurus japonicus Steud.) identified upregulation of CYP genes along with target site mutations (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Xu, Zhang, Bai and Dong2018). In another Japanese foxtail population, CYP75B4, an ABC transporter (ABCG36), and a LAC gene (LAC15) were upregulated, contributing to metabolic resistance (Xu et al. Reference Xu, Ye, Liang, Cheng, Leng, Sun, Su, Xue, Dong and Wu2023). Li et al. (Reference Li, Liu, Wang, Chen, Bai and Pan2022) reported constitutive upregulation of three glycosyl-transferases and three ABC transporters, conferring metabolic resistance to fenoxaprop in a Japanese foxtail population from China. Enhanced diclofop-ethyl metabolism has been observed in a wild oat population from Western Australia (Ahmad-Hamdani et al. Reference Ahmad-Hamdani, Yu, Han, Cawthray, Wang and Powles2013).

Interestingly, some CYP genes confer metabolic resistance across multiple herbicide sites of action For example, Han et al. (Reference Han, Yu, Beffa, González, Maiwald, Wang and Powles2021) identified a single CYP gene (CYP81A10v7) that provided cross-resistance to five different herbicide sites of action, including ACCase inhibitor, in rigid ryegrass from Australia. In Echinochloa phyllopogon, overexpression of CYP81A12 and CYP81A21, previously linked to ALS-inhibitor resistance, was also found to confer ACCase-inhibitor resistance (Iwakami et al. Reference Iwakami, Kamidate, Yamaguchi, Ishizaka, Endo, Suda, Nagai, Sunohara, Toki, Uchino, Tominaga and Matsumoto2019).

Coexistence of Target Site and Non–Target Site Mechanisms

The coexistence of target site and non–target site resistance mechanisms has been reported in several weed species, which has complicated efforts to understand the physiology, biology, and genetics of herbicide resistance (Jugulam and Shyam Reference Jugulam and Shyam2019). In ACCase inhibitor-resistant short-spiked canary grass (Phalaris brachystachys Link), multiple populations have been found to exhibit both target site and non–target site resistance mechanisms (Golmohammadzadeh et al. Reference Golmohammadzadeh, Rojano-Delgado, Vázquez-García, Romano, Osuna, Gherekhloo and De Prado2020; Vázquez-García et al. Reference Vázquez-García, Torra, Palma-Bautista, Alcántara-de la Cruz and De Prado2021). Similarly, the coexistence of target site and non–target site resistance has been documented in several Lolium species (Ghanizadeh et al. Reference Ghanizadeh, Buddenhagen, Harrington, Griffiths and Ngow2022; Torra et al. Reference Torra, Montull, Taberner, Onkokesung, Boonham and Edwards2021; Yanniccari et al. Reference Yanniccari, Gigón and Larsen2020). In blackgrass populations, metabolic resistance has been reported alongside target site mutations (Cocker et al. Reference Cocker, Moss and Coleman1999; Hall et al. Reference Hall, Moss and Powles1997; Franco-Ortega et al. Reference Franco-Ortega, Goldberg-Cavalleri, Walker, Brazier-Hicks, Onkokesung and Edwards2021). While target site resistance is more common in wild oat, one population from China was found to exhibit both target site and non–target site resistance mechanisms (Han et al. Reference Han, Sun, Ma, Wang, Lan, Gao and Huang2023).

Management of ACCase Inhibitor-Resistant Weeds

Italian ryegrass leads with 20 reported cases of resistance to ACCase inhibitors, followed by wild oat with eight cases, primarily from wheat fields (Heap Reference Heap2025). Other significant ACCase inhibitor-resistant grass weeds include johnsongrass, giant foxtail (Setaria faberi Herrm.), and Echinochloa spp., which have evolved resistance primarily in soybean, cotton, and rice fields. The management strategies discussed here focus on controlling ACCase inhibitor-resistant Italian ryegrass and wild oat in wheat, as well as johnsongrass in soybean and cotton.

Management of ACCase inhibitor-resistant Italian Ryegrass and Wild Oat in Wheat

Managing ACCase inhibitor-resistant Italian ryegrass and wild oat in wheat production requires an integrated, multifaceted approach to address evolving herbicide resistance (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Singh, Martins, Ferreira, Smith and Bagavathiannan2021). Effective management strategies should combine cultural, mechanical, and chemical control methods to reduce seed production and limit seed bank accumulation.

Cultural and Mechanical Control

Crop rotation is one of the most effective strategies for managing ACCase inhibitor-resistant Italian ryegrass. Rotating wheat with broadleaf crops that allow the use of alternative herbicides helps break the weed’s life cycle and reduces seedbank accumulation (Beckie and Harker Reference Beckie and Harker2017). Additionally, modifying planting geometry by increasing wheat planting density or using competitive wheat varieties can suppress Italian ryegrass growth by limiting its access to light, water, and nutrients (Hashem et al. Reference Hashem, Radosevich and Roush1998; Medd et al. Reference Medd, Auld, Kemp and Murison1985).

Other effective management techniques include:

-

Preplant tillage, which disrupts seedling emergence;

-

Mowing at critical growth stages, which can reduce seed production (Walsh and Powles Reference Walsh and Powles2007); and

-

Harvest weed seed control techniques, such as chaff lining and impact mills, which deplete the soil seed bank by preventing weed seeds from returning to the field at harvest (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Young, Schwartz-Lazaro, Korres, Walsh, Norsworthy and Bagavathiannan2022a; Shergill et al. Reference Shergill, Schwartz-Lazaro, Leon, Ackroyd, Flessner, Bagavathiannan, Everman, Norsworthy, VanGessel and Mirsky2020; Walsh et al. Reference Walsh, Harrington and Powles2013).

These strategies help reduce the persistence of resistant populations, ensuring long-term weed management and sustainable crop production.

Chemical Control

Alternative herbicides such as ALS inhibitors (e.g., mesosulfuron, pyroxsulam), glyphosate, and trifluralin, can help reduce selection pressure on ACCase inhibitors, thereby minimizing the likelihood of cross-resistance to multiple herbicides (Beckie and Harker Reference Beckie and Harker2017). Sulfonylureas and triazines applied preemergence can be effective (Boutsalis et al. Reference Boutsalis, Broster and Preston2012). The ALS inhibitors applied postemergence can control ACCase inhibitor-resistant Italian ryegrass, but overuse should be avoided to prevent the evolution of resistance. Ellis et al. (Reference Ellis, Steckel, Main, De Melo, West and Mueller2010) demonstrated effective control of Italian ryegrass with chlorsulfuron applied preemergence (71% to 94% control), flufenacet + metribuzin applied preemergence (84% to 96% control), pendimethalin applied preemergence or delayed preemergence showed variable control (Ellis et al. Reference Ellis, Steckel, Main, De Melo, West and Mueller2010; Maity et al. Reference Maity, Young, Schwartz-Lazaro, Korres, Walsh, Norsworthy and Bagavathiannan2022a). The postemergence herbicides such as pinoxaden, mesosulfuron, flufenacet + metribuzin, and chlorsulfuron + flucarbazone provided >80% control. In Texas and Arkansas, a premix of flufenacet (305 g ai ha−1) + metribuzin (76 g ai ha−1) mixed with pyroxasulfone (89 g ai ha−1) applied early postemergence followed by pinoxaden (59 g ai ha−1) applied in spring, in combination with narrow windrow burning, a harvest weed seed control technique, reduced Italian ryegrass density to near zero by the end of a 4-yr trial (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Young, Schwartz-Lazaro, Korres, Walsh, Norsworthy and Bagavathiannan2022a).

Triallate and pyroxasulfone applied preemergence are particularly effective when applied before wild oat emergence (Martinson et al. Reference Martinson, Durgan, Gunsolus, Sothern and Forcella2014; O’Donovan et al. Reference O’Donovan, Harker, Clayton and Maurice2007). These herbicides inhibit the growth of germinating wild oat seeds, reducing population density before crop establishment and providing a valuable alternative in fields where ACCase inhibitors are no longer effective. Mixing ACCase inhibitors with other herbicides such as ALS inhibitors can improve wild oat control. The combination of two different herbicide modes of action reduces the likelihood of resistant individuals surviving, because the probability of weeds being resistant to both mechanisms is lower (Owen et al. Reference Owen, Martinez and Powles2015). For postemergence control of ACCase inhibitor-resistant wild oat, mesosulfuron-methyl (an ALS inhibitor) is an effective option (Beckie et al. Reference Beckie, Thomas and Stevenson2001). Travlos et al. (Reference Travlos, Giannopolitis and Economou2011) reported 97% control of ACCase inhibitor-resistant wild oat with a mixture of mesosulfuron and iodosulfuron. Fluroxypyr, a synthetic auxin herbicide, though not typically used for wild oat control, can be included in a mixture to improve control, particularly in fields where broadleaf weeds need management (Beckie et al. Reference Beckie, Lozinski, Shirriff and Brenzil2019).

Johnsongrass Control in Soybean and Cotton

As of March 2025, there have been 12 reported cases of ACCase-inhibiting herbicide-resistant johnsongrass, with six cases documented in the United States (Heap Reference Heap2025). Managing ACCase inhibitor-resistant johnsongrass in corn and soybean presents a challenge. However, most resistant populations do not exhibit cross-resistance (Smeda et al. Reference Smeda, Snipes and Barrentine1997), allowing the use of alternative ACCase inhibitors for control. For example, González-Torralva and Norsworthy (Reference González-Torralva and Norsworthy2024) reported that clethodim provided 100% control of fluazifop-resistant johnsongrass. Scarabel et al. (Reference Scarabel, Panozzo, Savoia and Sattin2014) found that cycloxydim achieved 90% control of fluazifop-resistant johnsongrass. Bradley and Hagood (Reference Bradley and Hagood2001) documented a johnsongrass population in Virginia that is resistant to fluazifop, quizalofop, and sethoxydim, but susceptible to clethodim. These findings suggest that clethodim and cycloxydim remain effective options for controlling fluazifop-resistant johnsongrass, emphasizing the importance of rotating ACCase inhibitor to delay the evolution of resistance.

The ALS-inhibiting herbicides can effectively control ACCase inhibitor-resistant johnsongrass; however, documented cases of ALS inhibitor-resistant johnsongrass populations highlight the need for caution in overreliance on ALS inhibitors (Maity et al. Reference Maity, Young, Subramanian and Bagavathiannan2022b). Alternative control options include the following:

-

Atrazine, which is widely used on corn, has been shown to control johnsongrass, particularly when applied preemergence (Shaw and Owen Reference Shaw and Owen2012).

-

S-metolachlor can provide effective preemergence control, as reported by Webster and Grey (Reference Webster and Grey2015).

-

Spot treatments or manual removal of small patches are recommended to prevent further spread (Burgos et al. Reference Burgos, Kuk and Talbert2008).

-

Scarabel et al. (Reference Scarabel, Panozzo, Savoia and Sattin2014) found that fluazifop-resistant johnsongrass was effectively controlled by S-metolachlor and nicosulfuron when applied 1 and 4 d after soybean planting.

Johnsongrass is more susceptible to control measures at the early seedling stage than at maturity (Vila-Aiub et al. Reference Vila-Aiub, Goh and Powles2019). However, preemergence herbicides such as S-metolachlor, pendimethalin, flufenacet, and clomazone, which are labeled for use on soybean and corn, are effective only on seedlings from seeds and not on those emerging from rhizomes (Scarabel et al. Reference Scarabel, Panozzo, Savoia and Sattin2014). The postemergence herbicides capable of controlling johnsongrass from both seeds and rhizomes in soybean or cotton are ACCase inhibitors such as fluazifop, propaquizafop, and quizalofop. In contrast, the only effective herbicides for use on cereal crops, including corn, are ALS inhibitors, specifically sulfonylureas. In soybean- and cotton-dominant cropping systems, if a FOP-resistant johnsongrass survives a postemergence herbicide, it can produce rhizomes that are not susceptible to any preemergence or postemergence herbicide recommended for these crops. This facilitates the spread of FOP-resistant johnsongrass, because resistant rhizomes proliferate under reduced- or no-till conditions, leading to localized patches of resistant plants. Early identification and eradication of resistant patches are critically necessary for preventing the spread of FOP-resistant johnsongrass biotypes.

Scarabel et al. (Reference Scarabel, Panozzo, Savoia and Sattin2014) cautioned that once FOP-resistant johnsongrass becomes established, management options become severely limited. Potential control strategies include:

-

Stale seedbed techniques;

-

Application of nonselective herbicides before sowing.

-

Crop rotation with corn.

-

Fallow periods.

-

Applying sulfonylureas postemergence to manage ACCase inhibitor-resistant weeds may accelerate the evolution of multiple herbicide resistance, making this approach only a short-term solution (Collavo et al. Reference Collavo, Strek, Beffa and Sattin2013).

-

A medium- to long-term strategy should focus on integrated chemical and agronomic practices to prevent or slow the spread of FOP-resistant johnsongrass.

Herbicide Resistance Management Programs and Decision Support Tools

The formation and promotion of state- or university-aided integrated weed management programs that monitor and manage herbicide resistance at the regional level, preferably at the county level, are increasingly important. These programs must involve regular field surveys for new and existing weeds and the use of weed resistance testing to track the abundance and spread of resistant weed populations and provide growers with specific recommendations (McDonald et al. Reference McDonald, Sarangi, Rees and Jhala2023). Development and use of rapid resistance-testing methods can allow the early detection of herbicide resistance (Kaundun et al. Reference Kaundun, Hutchings, Dale, Baily and Glanfield2011), enabling growers to make informed decisions about alternative management strategies (Owen et al. Reference Owen, Martinez and Powles2014). In this context, decision support tools (DSTs) play a crucial role in managing ACCase inhibitor-resistant weeds, particularly in cereal and soybean-cotton cropping systems. These tools leverage data on weed populations, field history, herbicide application history, and environmental conditions to guide farmers for developing weed resistance management strategies (Davis et al. Reference Davis, Shrestha and Riar2016). By analyzing factors such as weed life cycles and mechanisms of resistance, DSTs can recommend integrated approaches that include diverse herbicide rotations, cultural practices, and alternative control methods (Heap Reference Heap2022). Additionally, DSTs can simulate various scenarios to evaluate the long-term impact of management practices on weed resistance evolution, enabling farmers to make data-driven decisions that reduce selection for resistant biotypes (Jhala et al. Reference Jhala, Singh, Shergill, Singh, Jugulam, Riechers, Ganie, Selby and Norsworthy2024; Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Oliveira and Santos2012). Ultimately, the adoption of DSTs can enhance the sustainability of herbicide programs and improve crop yield by effectively managing ACCase inhibitor-resistant weeds (de Sanctis and Jhala Reference de Sanctis and Jhala2025).

Furthermore, studying the genetic mechanisms underlying herbicide resistance can help identify molecular targets for future weed control strategies (Gaines et al. Reference Gaines, Duke, Morran, Rigon, Tranel, Kupper and Dayan2020). Biotechnological approaches, such as gene-editing tools (e.g., CRISPR-Cas9), offer the potential to develop herbicide-resistant crop varieties that can outcompete or suppress the growth of ACCase inhibitor-resistant grass weeds. Sustainable crop production in regions affected by ACCase inhibitor-resistant weeds will require integrated weed management strategies, combining advances in chemical control, genetic innovations, machine learning technologies, and judicious use of existing herbicides. Continued research and innovation in these areas will be essential for long-term management of ACCase-inhibiting herbicide-resistant weeds.

Future of ACCase-Inhibiting Herbicides

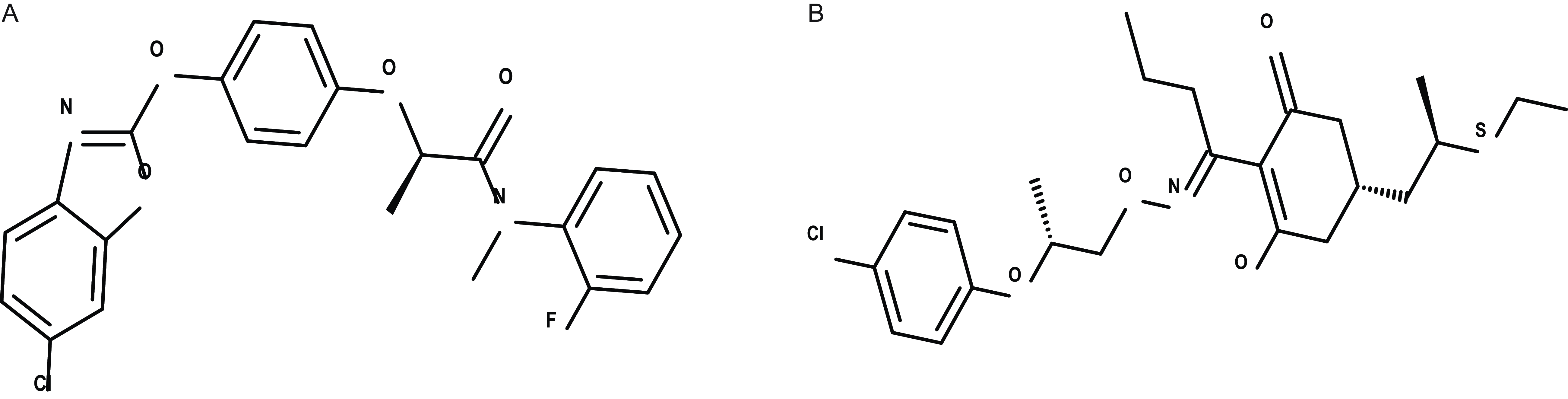

The FOPs and DIMs are the two major chemical classes of ACCase-inhibiting herbicides, extensively used for grass weed control over several decades. A notable recent development in the FOP class is the commercialization of metamifop (Figure 6A) by Dongbu Hannong Chemical Co Ltd (Seoul, Korea) in 2008 for postemergence control of barnyardgrass in rice (Kim et al. Reference Kim, Chang, Ko, Ryu, Woo, Koo, Kim and Chung2003a; Xia et al. Reference Xia, Tang, He, Kang, Ma and Li2016). The evolution of ACCase inhibitor-resistant weed species has intensified the need for novel grass herbicides. A recent advancement in the DIM class is feproxydim (Figure 6B), developed by CYNDA for controlling grass weeds resistant to ALS inhibitors, the FOP class of ACCase inhibitors, and quinclorac in paddy rice (Wang et al. Reference Wang, Liu, Sun, Chen, Li, Zou and Zhang2020).

Figure 6. Example of recent research and development activity in two major ACCase-inhibiting herbicide families—aryloxyphenoxypropionate (FOPs) and cyclohexanediones (DIMs) A) metamifop: FOP herbicide for rice; B) feproxydim: DIM herbicide in development for rice.

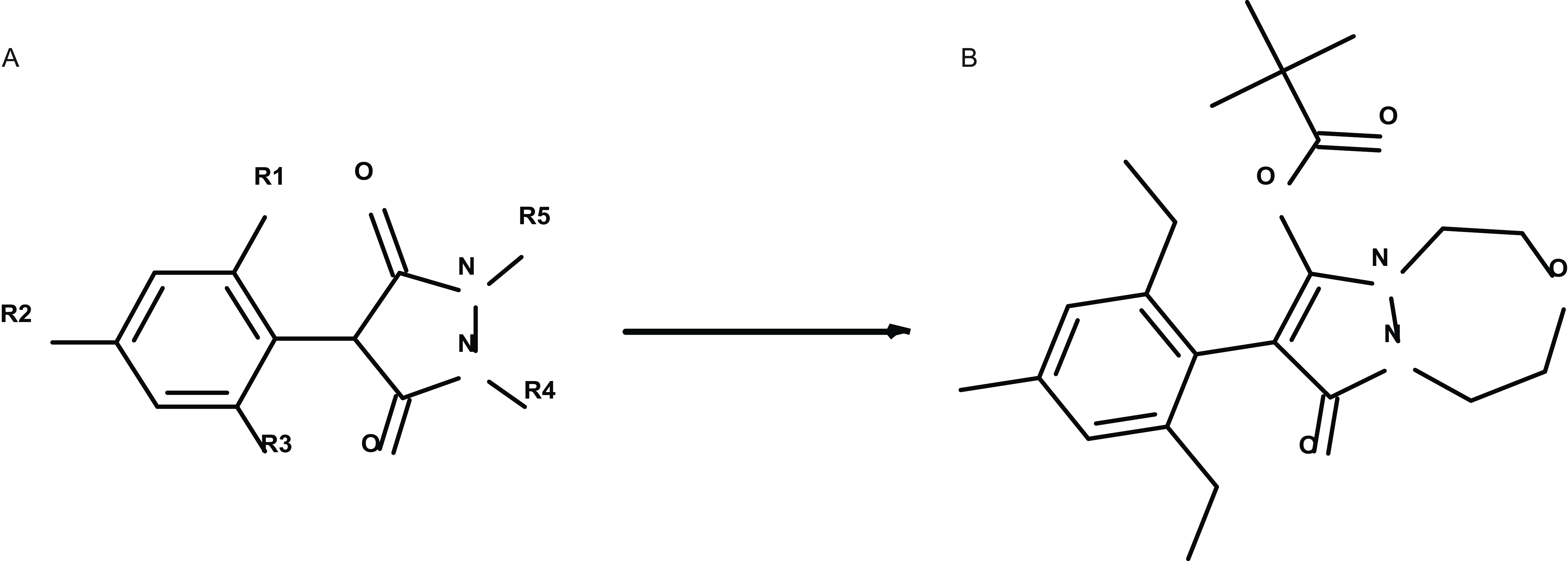

A major breakthrough in the ACCase-inhibiting herbicide site of action was the discovery and introduction of pinoxaden by Syngenta, marking the first member of the DEN. This was achieved by refining the structure-activity relationship, optimizing aryl, dione, and hydrazine components of 4-aryl-pyrazolidine-3,5-diones (Figure 7A) to enhance efficacy. By incorporating a [1,4,5] oxadiazepine ring, Syngenta improved selectivity for cereal crops, leading to the optimized molecule—pinoxaden (Figure 7B) (Muehlebach et al. Reference Muehlebach, Boeger, Cederbaum, Cornes, Friedmann, Glock, Niderman, Stoller and Wagner2009). Following the discovery of pinoxaden, research efforts continued to focus on phenylpyrazoles and 2-aryl-1,3-diones, leading to nearly 100 patents claiming postemergence grass weed control in cereal crops (Barber Reference Barber2023). Several distinct chemotypes have been reported in patent literature, including 2-aryl-cyclopentane-1,3-diones, 2-aryl-cyclohexane-1,3-diones, 2-aryl-tetramic, 2-aryl-tetronic acids, aryl pyran, piperidinedones, 2-aryl-pyrazolo-1,3-diones, and 2-aryl-pyridazine-1,3-diones (Wenger et al. Reference Wenger, Niderman, Mathews, Wailes, Crop Protection Compounds, Jeschke, Witschel, Kramer and Schirmer2020).

Figure 7. General structure of Syngenta’s starting point A) 4-aryl-pyrazolidine-3,5-dione and B) optimized compound pinoxaden that was commercialized for broad-spectrum grass weed control in cereals.

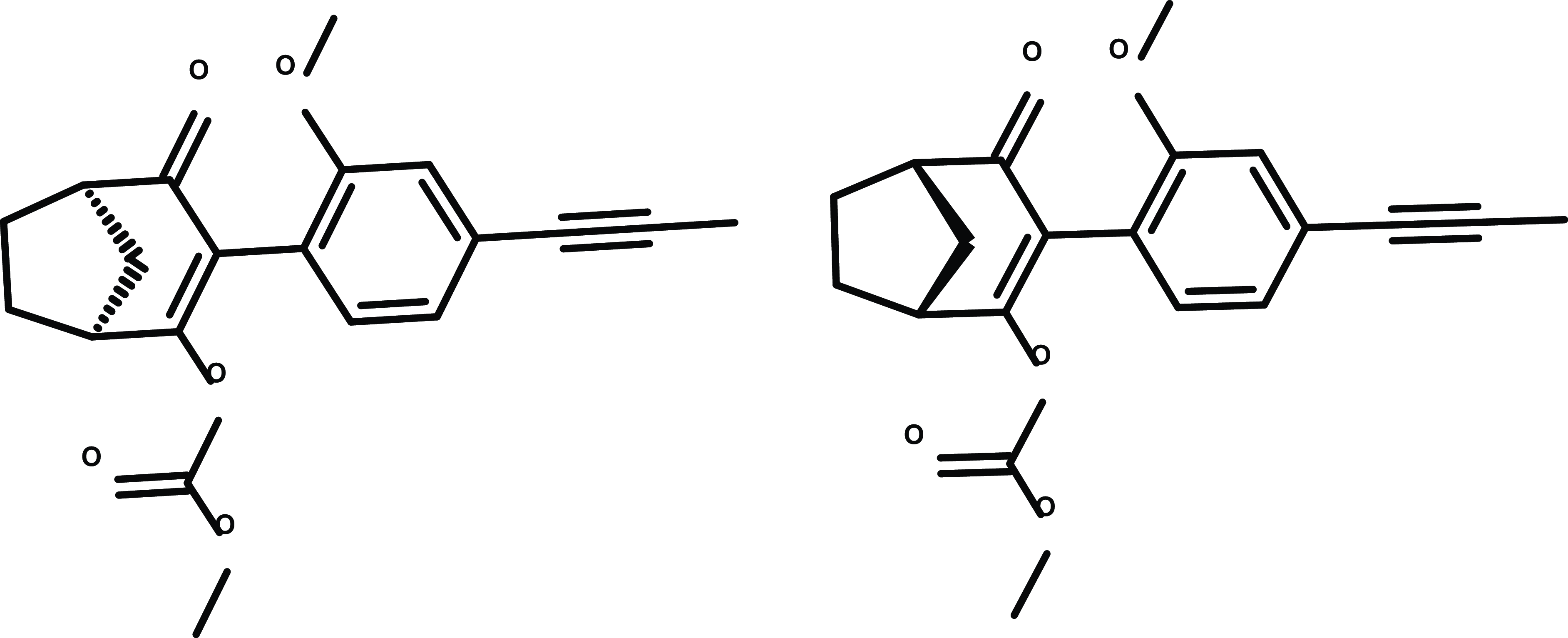

A recent advancement in the development of ACCase inhibitors has been the discovery of metproxybicyclone for soybean and other dicot crops (Scutt et al. Reference Scutt, Willetts, Campos, Oliver, Hennessy, Joyce, Hutchings, Goupil, Colombo and Kaundun2024). The approach began with cyclohexane-1,3-dione and bicyclo[3.2.1]octane-2,4-dione to establish basic structure-activity relationships (Figure 8). Metproxybicyclone will be the first carbocyclic aryl-dione herbicide in a new ACCase inhibitor family. It will be commercialized for postemergence control of sensitive and ACCase inhibitor-resistant grass weeds in dicotyledonous crops, including soybean, cotton, and sugar beet (Scutt et al. Reference Scutt, Willetts, Campos, Oliver, Hennessy, Joyce, Hutchings, Goupil, Colombo and Kaundun2024).

Figure 8. Chemical structure of metproxybicyclone, the first carbocyclic aryl-dione herbicide from Syngenta that will be commercialized for the postemergence control of sensitive and herbicide resistant grass species in dicotyledonous crops.

Metproxybicyclone can potentially control target site and non–target site ACCase inhibitor-resistant populations of goosegrass and Italian ryegrass in greenhouse studies (Scutt et al. Reference Scutt, Willetts, Campos, Oliver, Hennessy, Joyce, Hutchings, Goupil, Colombo and Kaundun2024). It has proven highly effective against key grass weeds, including sourgrass, johnsongrass, and barnyardgrass, which dominate soybean weed spectra in major production regions such as Brazil and Argentina (Scutt et al. Reference Scutt, Willetts, Campos, Oliver, Hennessy, Joyce, Hutchings, Goupil, Colombo and Kaundun2024). Another new class of ACCase inhibitor, α-aryl-keto-enol (aryl-KTE) was explored by Bayer Crop Science as a possible solution for the control of ACCase inhibitor-resistant grass weeds (Lee et al. Reference Lee, Payne, Rees, Ahrens, Arve, Asmus, Bojack, Arsequell, Gatzweiler, Helmke, Kallus, Laber, Lange, Lehr, Menne, Rosinger, Schulte, Sommer and Barber2025). Structural features of aryl-KTE class of ACCase inhibitor compounds have the potential to provide high selectivity in soybean while providing control of resistant grass weeds. As ACCase inhibitors and glyphosate-resistant grass weeds continue to spread, the demand for novel ACCase-inhibiting herbicides will become increasingly critical. The limited availability of grass-active herbicides further underscores the need for innovative solutions to combat herbicide-resistant weeds.

Acknowledgments

We thank the reviewers and associate editor for their useful comments.

Funding

Support for this project was provided by the U.S. Department of Agriculture–National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Crop Protection and Pest Management award 2024-70006-43500 for the Nebraska Extension Implementation Program.

Competing Interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.