Highlights

-

• Typically developing children marked focus with pitch, duration and intensity.

-

• Autistic children marked focus with duration but did not use pitch or intensity.

-

• Greater L1 exposure improved pitch/intensity modulation in autistic children.

-

• L2 experience did not affect autistic children’s focus production in L1.

1. Introduction

It is well established that exposure to two languages during early development does not negatively impact typical language acquisition (e.g., De Houwer, Reference De Houwer1995; Deuchar & Quay, Reference Deuchar and Quay2000; Genesee et al., Reference Genesee, Nicoladis and Paradis1995; Müller & Hulk, Reference Müller and Hulk2001; Paradis & Genesee, Reference Paradis and Genesee1996; Yip & Matthews, Reference Yip and Matthews2007). Although the impact of bilingualism has been extensively examined in typically developing (TD) children, systematic investigation into its impact on children with autism spectrum disorder (ASD) remains limited. As a neurodevelopmental disorder, ASD significantly affects children’s communication skills (e.g., Demetriou et al., Reference Demetriou, Lampit, Quintana, Naismith, Song, Pye, Hickie and Guastella2018; Eigsti et al., 2011; Tager-Flusberg et al., 2005). Language development in autistic children is typically marked by substantial delays and difficulties across multiple linguistic domains, including prosody, pragmatics and morphosyntax (e.g., Eigsti et al., 2011; Tager-Flusberg et al., 2005). These language challenges often lead parents and professionals to question whether exposure to two languages might impose additional burden on autistic children’s first language (L1) acquisition (Hampton et al., Reference Hampton, Rabagliati, Sorace and Fletcher-Watson2017; Kay-Raining Bird et al., Reference Kay-Raining Bird, Lamond and Holden2012; Yu, Reference Yu2013). Given the growing number of children, including those diagnosed with ASD, being raised bilingually from an early age, it is crucial to explore how bilingual exposure influences L1 acquisition in autistic children.

In the last decade, there has been growing attention on bilingual language acquisition in autistic children (e.g., Dai et al., Reference Dai, Burke, Naigles, Eigsti and Fein2018; Gonzalez-Barrero & Nadig, Reference Gonzalez-Barrero and Nadig2017, Reference Gonzalez-Barrero and Nadig2019; Hambly & Fombonne, Reference Hambly and Fombonne2012; Kay-Raining Bird et al., Reference Kay-Raining Bird, Lamond and Holden2012; Ohashi et al., Reference Ohashi, Mirenda, Marinova-Todd, Hambly, Fombonne, Szatmari and Thompson2012; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Marinova-Todd and Mirenda2012; Reetzke et al., Reference Reetzke, Zou, Sheng and Katsos2015; Valicenti-McDermott et al., Reference Valicenti-McDermott, Tarshis, Schouls, Galdston, Hottinger, Seijo and Shinnar2013; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Munson, Greenson, Hou, Rogers and Estes2019). Contrary to common assumptions, emerging evidence indicates that bilingualism does not negatively impact autistic children’s language acquisition, including their vocabulary, syntax and pragmatics (Beauchamp et al., Reference Beauchamp, Rezzonico and Macleod2020; Dai et al., Reference Dai, Burke, Naigles, Eigsti and Fein2018; Hambly & Fombonne, Reference Hambly and Fombonne2012; Meir & Novogrodsky, Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2020, Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2021; Ohashi et al., Reference Ohashi, Mirenda, Marinova-Todd, Hambly, Fombonne, Szatmari and Thompson2012; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Marinova-Todd and Mirenda2012; Reetzke et al., Reference Reetzke, Zou, Sheng and Katsos2015; Skrimpa et al., Reference Skrimpa, Spanou, Bongartz, Peristeri, Andreou and Papadopoulou2022; Valicenti-McDermott et al., Reference Valicenti-McDermott, Tarshis, Schouls, Galdston, Hottinger, Seijo and Shinnar2013; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Munson, Greenson, Hou, Rogers and Estes2019). Some studies even suggest that bilingual autistic children may outperform monolingual autistic peers in areas such as total vocabulary size (Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Marinova-Todd and Mirenda2012), verbal fluency (Gonzalez-Barrero & Nadig, Reference Gonzalez-Barrero and Nadig2017), focus production (Ge et al., Reference Ge, Lee, Liu, Yuen and Yip2024) and narrative skills (Peristeri et al., Reference Peristeri, Baldimtsi, Andreou and Tsimpli2020).

Despite the growing number of research, the focus has largely been on morphosyntactic abilities, with comparatively little attention given to prosody. Prosody refers to suprasegmental features of speech, such as pitch, duration, intensity and voice quality. The various functions of prosody include verbal punctuation or phrasing, expressing emotions, indicating utterance type (question, statement, invitation) and highlighting the focal element of an utterance (Roach, Reference Roach2000). Atypical prosody is a core feature of ASD (Baltaxe & Simmons, Reference Baltaxe, Simmons, Schopler and Mesibov1992; Tager-Flusberg, Reference Tager-Flusberg2001) and is commonly included as a diagnostic characteristic in clinical assessments (Lord et al., Reference Lord, Rutter, DiLavorce, Risi, Gotham and Bishop2012; Rutter et al., Reference Rutter, LeCouteur and Lord2003). Autistic children often demonstrate a wide heterogeneity in prosody, including variations in speech rate, rhythm, volume, intonation, or lack of register change (Rice et al., Reference Rice, Warren and Betz2005; Shriberg et al., Reference Shriberg, Paul, McSweeny, Klin, Cohen and Volkmar2001).

Given the well-documented prosodic difficulties in autistic children, it is important to examine whether exposure to a second language (L2) imposes additional challenges on their prosodic skills in their L1, especially when L1 and L2 differ typologically in the use of prosody. This study investigated prosodic focus production in Cantonese-English bilingual autistic children in Hong Kong. Studying bilingual autistic children in Hong Kong is particularly significant not only because this population remains understudied but also because Hong Kong offers a unique bilingual environment, with two typologically distinct languages – Cantonese and English – acquired early in life. Although both languages use prosody to mark focus, they differ considerably in the acoustic correlates and strategies involved. English typically marks focus with an accent to the focal element(s), manifested in expanded pitch range, increased intensity and longer duration (Gussenhoven, Reference Gussenhoven1983; Xu & Xu, Reference Xu and Xu2005). In contrast, Cantonese primarily relies on duration and intensity to mark focus (Fung & Mok, Reference Fung and Mok2018; Gu & Lee, Reference Gu and Lee2007; Leung & Peng, Reference Leung and Peng2015; Wu & Xu, Reference Wu and Xu2010). More importantly, Cantonese heavily relies on morphosyntactic devices such as focus particles and word order to mark focus, making the use of prosody optional in this regard (Lee, Reference Lee2019; Matthews & Yip, 2011).

These typological differences in prosodic focus marking raise important questions regarding whether acquiring English (L2) influences bilingual autistic children’s prosodic focus marking in Cantonese (L1). Specifically, this study aims to explore potential bilingualism effects or adaptations in prosody due to bilingualism and whether ASD moderates these patterns. In Hong Kong, most children are sequential early bilinguals who typically acquire Cantonese at home as L1 and begin learning English as L2 in kindergartens before the age of 3. This early bilingual exposure provides a naturalistic setting to examine how bilingualism intersects with ASD in shaping prosodic production across two typologically distinct languages. Addressing this question will not only fill a critical gap in bilingualism and autism research but also inform educators and clinicians concerned about language development in bilingual autistic populations, particularly regarding concerns over English L2 acquisition affecting Cantonese L1 prosody.

1.1. Bilingualism as a continuum

Bilingualism is commonly defined as proficiency in two or more languages (Marian, 2018). Traditionally, research in this area has relied on a categorical distinction, classifying speakers as either monolingual or bilingual, for the purpose of group comparison. In such studies, bilingual children are often evaluated against monolingual norms, with any observed differences in language use frequently interpreted as errors or deficits. However, this binary approach fails to capture the rich variability and complexity inherent in bilingual experiences, which can differ widely in aspects including proficiency levels, age of acquisition and daily patterns of language use (DeLuca et al., 2019).

In response to drawbacks of the categorical approach, recent researchers advocate for a more nuanced and dynamic conceptualization of bilingualism. Rather than viewing bilingualism as a fixed category, researchers now emphasize its fluid and evolving nature, shaped by individual experience and sociolinguistic contexts (Wiese et al., 2022). A growing consensus warns against direct monolingual-bilingual group comparisons, as such dichotomy risk obscuring the diversity of language experience and its cognitive implications (De Houwer, Reference De Houwer2023; Kremin & Byers-Heinlein, Reference Kremin and Byers-Heinlein2021; Leivada et al., Reference Leivada, Rodríguez-Ordóñez, Parafita Couto and Perpiñán2023; Rothman et al., Reference Rothman, Bayram, DeLuca, González Alonso, Kubota, Puig-Mayenco, Luk, Anderson and Grundy2023; Xia et al., Reference Xia, Sorace, Vega-Mendoza and Bak2025). By describing bilingualism along a continuum, this approach acknowledges variations in language knowledge, exposure and usage in different social contexts. Importantly, such continuous framework allows researchers to detect subtle effects of bilingual experience on cognition that may be masked by rigid groupings.

In Hong Kong, almost all Cantonese-speaking children are exposed to English since kindergarten, but exposure levels vary widely. Aligned with these recent developments, this study adopts a continuous measure of bilingual experience, operationalized as the cumulative exposure in each language assessed through detailed parental reports.

1.2. Prosodic focus marking in English and Cantonese

Focus is a key concept of informational structure, typically referring to new or contrastive information in a sentence (Chafe, Reference Chafe and Li1976; Gussenhoven, Reference Gussenhoven, Lee, Gordon and Büring2006; Krifka, Reference Krifka2008; Lambrecht, Reference Lambrecht1994). For example, the focus dog in (1) presents merely non-presupposed information, while the focus pig forms a contrast with the alternative dog mentioned in the question.

It has long been recognized that languages differ in both the linguistic devices they use to realize focus and the extent to which the same linguistic devices are used. In English, a Western Germanic language, focus is primarily realized by assigning an accent to the focal element(s). Accents are manifested primarily in expanded pitch range, accompanied by increased intensity and longer duration (Gussenhoven, Reference Gussenhoven1983; Xu & Xu, Reference Xu and Xu2005). Moreover, English exhibits post-focus compression, where pitch range and intensity are reduced after the focused element (Xu, Reference Xu2011; Xu et al., Reference Xu, Chen and Wang2012). For instance, the answer to question (2) would typically be uttered as (3), where PIG is accented (capitalization denotes accentuation) and correctly signals contrastive focus. However, accentuation on the object BUBBLES is infelicitous, as in (4).

In contrast, unlike English, the use of prosody to mark focus is highly constrained in Cantonese, a tonal language with six contrastive lexical tones (Chao, Reference Chao1947). In Cantonese, on-focus pitch expansion is not clearly demonstrated (Fung & Mok, Reference Fung and Mok2018; Man, Reference Man2002; Wu & Xu, Reference Wu and Xu2010), whereas on-focus lengthening and higher intensity are more evident (Fung & Mok, Reference Fung and Mok2018; Gu & Lee, Reference Gu and Lee2007; Leung & Peng, Reference Leung and Peng2015; Wu & Xu, Reference Wu and Xu2010). Importantly, Cantonese compensates for limited prosodic cues by employing rich morphosyntactic strategies, particularly through an extensive system of focus particles (FPs) and flexible word order adjustments (Lee, Reference Lee2019; Matthews & Yip, 2011). These particles explicitly indicate focus and can optionally co-occur with prosodic cues, making prosody less obligatory than in English.

The typological differences in focus marking between English and Cantonese have significant implications for bilingual acquisition in Cantonese-English children, both with and without ASD. For bilingual TD children, these differences might present a challenge in acquiring the distinct cue weightings and integrating language-specific focus marking strategies, in addition to the development of pragmatic competence to produce contrastive focus appropriately in each language. This interface domain might be vulnerable for cross-linguistic influence in bilingual children (Serratrice et al., 2004; Sorace & Filiaci, 2006; Sorace & Serratrice, 2009), manifested in transfer from one language to the other, or language delay or acceleration. Autistic children, who often exhibit difficulties in prosody and pragmatics, may face additional challenges navigating these cross-linguistic differences. Consequently, Cantonese-English bilingual autistic children might show delayed or divergent patterns in focus marking, reflected in less consistent use of prosody.

1.3. Prosodic focus production in autistic children

There is a paucity of research on how autistic children produce prosodic focus. Early investigations mainly relied on subjective judgement. A key study by Paul et al. (Reference Paul, Augustyn, Klin and Volkmar2005) used an experimental protocol to examine contrastive accent production in natural speech among English-speaking autistic individuals aged 14–21. Participants first listened to a sentence (e.g., “He wore the red tie for you”) and then read a second sentence aloud (e.g., “I prefer BLUE ties on gentlemen”) as if responding to the first sentence. Their spoken responses were prerecorded and later scored as correct or incorrect by an examiner blind to the participants’ diagnostic status. Results showed that autistic speakers made significantly more errors in placing contrastive accents to mark focus appropriately compared to their TD peers. Another series of studies used the Profiling Elements of Prosodic System – Children (PEPS-C; Peppé & McCann, Reference Peppé and McCann2003) to assess prosodic abilities related to focus production. In the task, children first viewed a picture (e.g., black sheep holding a ball) and heard a sentence that did not match the picture (e.g., “The black cow has the ball”). They were then asked to correct the sentence (e.g., “No, the black SHEEP has the ball”). Using the PEPS-C, Peppé et al. (Reference Peppé, Hare and Rutherford2007) tested the production of contrastive focus in 6- to 13-year-old English-speaking children with ASD. The participants’ responses were judged as correct or incorrect. The results showed that the ASD group made significantly more errors than the TD group, indicating great challenges for autistic children to produce prosodic focus correctly.

While the previous studies have highlighted the value of acoustic analysis over behavioural judgement for detecting subtle prosodic differences in speech (Diehl & Paul, Reference Diehl and Paul2009, Reference Diehl and Paul2013; McCann & Peppe, Reference McCann and Peppe2003; Paul et al., Reference Paul, Augustyn, Klin and Volkmar2005), acoustic measurements of prosodic focus in autistic children remain scarce, with only a few studies available so far (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang, Zhou, Chan, Li, Li, Tang, Chun and Chen2024; Diehl & Paul, Reference Diehl and Paul2013; Nadig & Shaw, Reference Nadig and Shaw2015). Using the PEPS-C, Diehl and Paul (Reference Diehl and Paul2013) investigated English-speaking autistic individuals aged 8–16 and found significant differences in their prosodic profiles compared to their TD peers. Specifically, autistic children exhibited significantly greater pitch ranges and higher intensity, suggesting a more exaggerated use of prosodic contrasts, although their average pitch did not differ from that of the TD group. In contrast, research by Nadig and Shaw (Reference Nadig and Shaw2015) revealed a different pattern. Using an interactive task, they found that both English-speaking children with ASD (ages 8–14) and their TD peers used duration and intensity effectively to mark focus, but neither group consistently used pitch changes to mark the contrast. Their study suggested that some prosodic parameters may be more salient or accessible than others for focus marking in autistic children.

Regarding Cantonese-speaking autistic children, Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Zhang, Zhou, Chan, Li, Li, Tang, Chun and Chen2024) examined the acoustic correlates of prosodic focus produced by autistic children aged 6–10 and their TD counterparts, using a speech elicitation task. They found that Cantonese-speaking autistic children showed insufficient on-focus expansion in fundamental frequency (f0) and duration relative to TD children, indicating reduced prosodic prominence where focus should be emphasized. Interestingly, there was no significant difference between the ASD and TD groups in intensity measures. Their findings might suggest language-specific prosodic strategies or differences in how prosodic correlates are employed in Cantonese focus marking.

For bilingual autistic children, the research on focus production is even more limited. Two recent studies have addressed this population. Using a picture elicitation task, Ge et al. (Reference Ge, Lee, Liu, Yuen and Yip2024) examined the production of focus in 5- to 9-year-old Cantonese-English monolingual and bilingual autistic children’s L1 Cantonese. The results showed that although bilingual autistic children had significantly lower accuracy than TD children in producing focus in subject and object positions, they outperformed their monolingual autistic peers in the production of object focus with a significantly higher accuracy. In addition, both monolingual and bilingual autistic children tend to make use of less prosodic means to produce focus, compared to their TD peers, indicating that prosody might be a more challenging domain for autistic children. Importantly, the total amount of English exposure did not relate to the accuracy of focus production in autistic and TD children. However, the study depended solely on perceptual judgement rather than acoustic measures, underlining the need for objective analyses in bilingual contexts.

Wang et al. (Reference Wang, Chen, Zhou, Liu, Xiao, Chan and Tang2024) expanded on this by employing acoustic measures to examine prosodic focus marking in English among 8- to 10-year-old Cantonese-English-Mandarin trilingual autistic and age-matched trilingual TD children. They found that the trilingual TD group had post-focus compression patterns via reducing mean duration, narrowing f0 range and lowering mean f0, f0 curve and mean intensity for words under both narrow and contrastive post-focus conditions, while the trilingual ASD group only had shortened mean duration and lowered f0 curves. However, neither the trilingual ASD nor the trilingual TD group showed much of on-focus expansion patterns in their L2 English. Although this work shed light on the acoustic correlates of focus marking in trilingual autistic children, it did not explore how varying degrees of trilingual exposure might relate to their prosodic performance.

In summary, while acoustic analysis is established as a critical tool for revealing subtle prosodic differences, objective data on prosodic focus production by autistic children – especially in bilingual contexts – remain limited. Furthermore, the effects of bilingual exposure on the prosodic abilities of autistic children have yet to be systematically examined, highlighting an important gap for future research.

2. The current study

To fill the gaps, this study used acoustic measurements to examine prosodic focus production in L1 Cantonese by Cantonese-English bilingual children with and without ASD. In addition, this study explored how bilingualism influences prosodic focus production in autistic children’s L1 Cantonese.

We focused on autistic children aged 5–9 because this period represents a key stage in the development of prosodic focus-marking abilities. TD children at the age of 4–5 have already acquired adult-like use of certain pitch and duration cues (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Szendrői, Crain and Höhle2019; Yang & Chen, Reference Yang and Chen2018), while autistic children aged 6–10 still have non-TD-like performance in prosodic marking. Therefore, focusing on this age group allows for meaningful examination of emerging prosodic skills and developmental variability in autistic children.

Investigating prosodic focus production allows us to explore how bilingual Cantonese-English speakers manage different cue weighting in two typologically distinct languages. Specifically, we raised two research questions:

-

(I) How do bilingual autistic children use pitch, duration and intensity to produce prosodic focus in their L1 Cantonese, compared to their bilingual TD peers and adults?

-

(II) How do bilingual proficiency and exposure influence their performance?

Regarding the first research question, we predict that bilingual TD children might use duration and intensity to mark focus in their L1, given that Cantonese primarily relies on these two prosodic correlates to mark focus. If cross-linguistic influence occurs from English to Cantonese, they might also use pitch to mark focus in production. For bilingual autistic children, we predict that they might differ from their TD peers, as prosodic focus production has been shown to be difficult for autistic children in general. To be more specific, they might use less pitch, duration or intensity in marking focus or have failed to use these prosodic means to mark focus at all. For the second research question, we predict that L2 English experience and exposure will not adversely affect the focus production in these bilingual autistic children, according to the previous findings.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

A power analysis was conducted to determine the minimum sample size required to detect group differences in our primary outcomes with adequate statistical power. The analysis was performed using G*Power software (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Buchner and Lang2009; version 3.1.9.7). We specified a medium effect size (Cohen’s d = 0.5), a significance level (α) of 0.05 and a desired power of 0.80. This effect size was informed by prior research on focus production in Cantonese-English bilingual children with and without ASD (e.g., Ge et al., Reference Ge, Lee, Liu, Yuen and Yip2024; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Chen, Zhou, Liu, Xiao, Chan and Tang2024), which reported group differences of comparable magnitude in similar prosodic measures. Based on these parameters and a two-tailed independent group comparison, the estimated sample size required per group was 26. Therefore, this study involved 46 autistic children, 60 TD children and 28 adults. Four autistic and four TD children were excluded for not completing testing, leaving 42 autistic and 56 TD children for analysis. All children and adults were sequential bilingual. There was no family history of developmental disorders among the TD children and adults. Autism screening was conducted for both TD children and adults using the Autism Spectrum Quotient in Cantonese: Children’s Version (AQ-Child; Auyeung et al., Reference Auyeung, Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright and Allison2008) and the Autism Spectrum Quotient (AQ-Adult; Baron-Cohen et al., Reference Baron-Cohen, Wheelwright, Skinner, Martin and Clubley2001), respectively. None of the participants in the TD or adult groups showed any indicators of being at risk for ASD. The study was approved by the University’s ethical research committee. Informed consent was obtained from parents of the children and adult participants.

As mentioned, this study adopts a continuous approach to bilingualism, since the degree of bilingual exposure varies significantly across Hong Kong bilingual children in different communicative contexts. To capture this variability, information on children’s bilingual exposure across the home, school and community settings was collected through a detailed parental report. Parents reported the language(s) spoken to their child by parents/caregivers and teachers and their child’s average weekly exposure to Cantonese and English, respectively, at home, school and community. This approach allowed us to place participants on a continuum of bilingual exposure levels.

Children’s non-verbal IQs were assessed with the Primary Test of Nonverbal Intelligence (PTONI; Ehrler & McGhee, Reference Ehrler and McGhee2008). Their Cantonese receptive vocabulary was measured by the Cantonese Receptive Vocabulary Test (CRVT; Cheung et al., Reference Cheung, Lee and Lee1997), and working memory was evaluated by the Backward Digit Span task based on the procedure included in the McCarthy Scales of Children’s Abilities (McCarthy, Reference McCarthy1972). Socioeconomic status was determined by maternal education. ASD diagnoses were validated with Module 3 of the Autism Diagnostic Observation Schedule, Second Edition (ADOS-2; Lord et al., Reference Lord, Rutter, DiLavorce, Risi, Gotham and Bishop2012), classifying those with a score of 7 or above as ASD. Demographic information for the three groups is summarized in Table 1.

Table 1. Demographic information of participants (SD in parentheses)

a Maternal education on a 1–4 scale: 1 = high school; 2 = associate degree; 3 = university; 4 = master/doctorate degree.

b Listening on a 1–5 scale: 1 = barely understand; 2 = poor, have difficulty in understanding and can only understand basic vocabulary and play simple games; 3 = fair, able to understand simple conversations, such as answering simple instructions, 4 = good, able to understand longer conversations, such as video programmes; 5 = very good, able to understand conversations in almost all situations.

c Speaking on a 1–5 scale: 1 = barely speak; 2 = poor, have difficulty expressing and can only use basic vocabulary and expressions to play simple games; 3 = fair, able to have simple communication; 4 = good, relatively fluent and able to hold conversations and communicate effectively; 5 = very good, very fluent and able to handle conversations in almost all situations.

* p < .05; ** p < .01; *** p < .001.

The two groups of children were matched in non-verbal IQ, Cantonese receptive vocabulary, working memory and maternal education. Our autistic children demonstrated relatively strong language and cognitive abilities, as reflected in their demographic data and mild symptom severity indicated by their ADOS-2 scores. They were significantly older than TD children (p = .008) and began acquiring English later (p = .041). Autistic children’s Cantonese listening (p < .001) and speaking skills (p < .001) were lower than TD’s, whereas the two groups did not differ in English speaking and listening according to parental reports. Both groups received similar amount of Cantonese input at home, school and in the community. However, autistic children received significantly less English input at home (t(96) = −3.73, p < .001), school (t(96) = −2.43, p = .017), community (t(96) = −2.22, p = .029) and as a total (t(96) = −4.26, p < .001).

3.2. Task and materials

We conducted a picture elicitation task to generate participants’ focus production. The recordings were conducted in a quiet, carpeted room to provide a child-friendly and naturalistic testing environment. Children were seated on a stable chair at an approximate distance of 15 cm from the built-in microphone of a Zoom H2n recorder, which was placed on a stable surface at a consistent height and monitored by the experimenter to maintain a stable setup. Although minor variations in mouth-to-microphone distance are inevitable with young children, the primary research questions focus on within-participant prosodic contrasts (e.g., relative changes in pitch, intensity or duration across focus conditions for a given speaker). For these relative, intra-speaker measures, small absolute variations in intensity are expected to have a negligible impact on the results.

Each participant first viewed a picture, as shown in Figure 1.

Figure 1. Example of picture stimuli.

Then, experimenter A described the picture using a consistent SVO sentence (e.g., zyu1zyu1 ceoi1 bo1bo1 “The pig blows bubbles”). Participants then recalled the sentences. Afterwards, experimenter B, pretending not to see the pictures, guessed the content of the pictures and asked participants to describe them, incorrectly substituting subjects, verbs and objects. This yielded four questions that elicited broad and narrow focus in three locations (subject, verb and object). When experimenter B described a picture incorrectly, participants were expected to correct the description with appropriate prosodic prominence on focus. Expected correct responses with appropriate prosodic devices are shown in (5).

Twenty-seven experimental pictures and paired sentences were constructed in three different tones. Only three lexical tones, that is, T1, T3 and T4 representing the high, mid and low tones in Cantonese, were included to streamline testing. The rising tones T2 and T5 were avoided, as well as T6, which is known to be merging with T3 (Mok et al., Reference Mok, Zuo and Wong2013). Pictures were randomly assigned to three lists, with each participant completing one list of nine experimental pictures (three pictures per tone) and two practice pictures. Participants’ responses were recorded for acoustic analysis. The experiment took each participant approximately 10 minutes to complete. Participants were unaware of the study’s purpose and received cash coupons as compensation.

3.3. Data analysis

Sound files were annotated using ProsodyPro (Xu, Reference Xu2013 [Version 5.7.8.7]). Intervals were labelled by the syllable. Markings of vocal pulses were manually checked and rectified to ensure accurate tracking of f 0. ProsodyPro then generated acoustical measurements including median f 0, duration, mean intensity, jitter and shimmer values for statistical analysis. We chose median f 0 over mean f 0 as the latter can be more easily skewed by outliers.

For the first research question, we fitted linear mixed-effects models to the aforementioned five dependent variables using the R package lmerTest (Kuznetsova et al., Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017, ver. 3.1–3) with the bottom-up approach: starting with the simplest model and progressively adding fixed and random effects to identifying the best-fitting model. To assess the goodness of the models, we compared nested models using the χ2-distributed likelihood ratio and its associated p-value to determine the better-fitting model. Post hoc analyses were conducted using the emmeans package (Lenth, Reference Lenth2020). The main fixed factors included Group (ASD, TD [baseline], Adult), Focus (narrow versus broad [coded 0.5, −0.5]), Location (subject[baseline], object, verb) and Tone (T1[baseline], T3, T4). Random intercepts and slopes for Focus (for all models) and Tone (for Table 2) were included by Subject, capturing within-subject variability in these predictors. In addition, random intercepts for Item were included to model between-item variations. Where there was an interaction involving Group, we further fitted linear mixed-effects models to the data of each Group subset, following the same procedures.

Table 2. Linear mixed-effects model on median pitch (f 0)

Note: Median_Pitch ~ Group + Focus + Location + Tone + Group:Focus + Group:Tone + Focus:Location + (1 + Focus + Tone | Subject) + (1 | Item).

*p< .05; **p< .01; ***p< .001.

For the second research question, bilingualism-related fixed factors on age of acquisition (AoA) of English, bilingual proficiency (Cantonese listening and speaking, English listening and speaking) and bilingual exposure (Cantonese and English exposure in home, school and community settings) were included for the ASD and TD groups, in addition to the fixed factors and random slopes. These bilingualism factors were drawn from the questionnaire completed by the parents.

4. Results

4.1. Median pitch (f0)

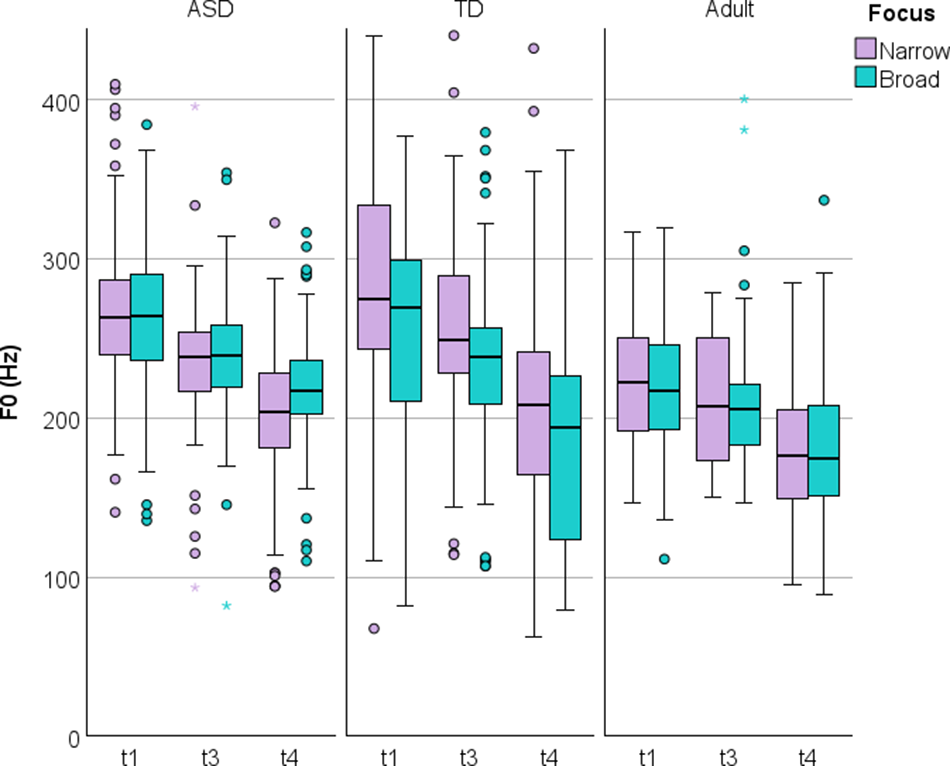

Figure 2 shows the median f 0 of on-focus marking in three groups of participants.

Figure 2. Median f0 of on-focus marking in three groups.

Evaluation of the model showed that the inclusion of Group (χ2 (2) = 8.982, p = .011), Focus (χ2(1) = 14.173, p < .001), Location (χ2 (2) = 79.113, p < .001), Tone (χ2(2) = 474.977, p < .001), two-way Group × Focus interaction (χ2(2) = 14.003, p < .001), two-way Group × Tone interaction (χ2(4) = 16.449, p = .002) and two-way Focus × Location interaction (χ2 (2) = 6.034, p = .049) significantly contributed to the model (see Table 2). The model also revealed that the main effects of Tone and Location were the strongest predictors of median pitch. In contrast, the effect of Focus was significant but small, indicating that while focus condition does modulate pitch, its magnitude is considerably smaller than tonal and positional effects.

Subsequent analyses indicated a significant difference between narrow and broad focus in the TD group (Estimate = 12.915, SE = 3.928, t(494.776) = 3.288, p = .001) across tones and focus locations. However, this pattern was not observed in autistic children and adults. The results suggest that TD children consistently used on-focus raising of median f 0, unlike adults and autistic children. Critically, the Group × Focus interactions showed small effect sizes, suggesting that while both groups differed slightly from TD children in how they marked narrow focus prosodically, these differences were modest.

Across groups, T1 syllables had the highest f 0, followed by T3 syllables and T4 syllables (T1-T3: p < .001; T1-T4: p < .001; T3-T4: p < .001). Median f 0 in three locations also showed similar patterns across groups, with focus on subject location having the highest f 0, followed by verb focus and object focus (subject-verb: p = .047, subject-object: p < .001, object-verb: p < .001) .

Within the TD group, the inclusion of AoA of English (χ 2(1) = 4.2063, p = .040) and Cantonese listening (χ 2(1) = 10.093, p = .002) significantly contributed to the model. TD children with higher proficiency of Cantonese listening and earlier AoA of English significantly lowered their median f 0.

Within the ASD group, the inclusion of Cantonese exposure at school (χ 2(1) = 8.979, p = .004) significantly improved model fitting. It suggests that bilingual autistic children with more Cantonese exposure at school produced lower median f 0 in general.

4.2. Duration

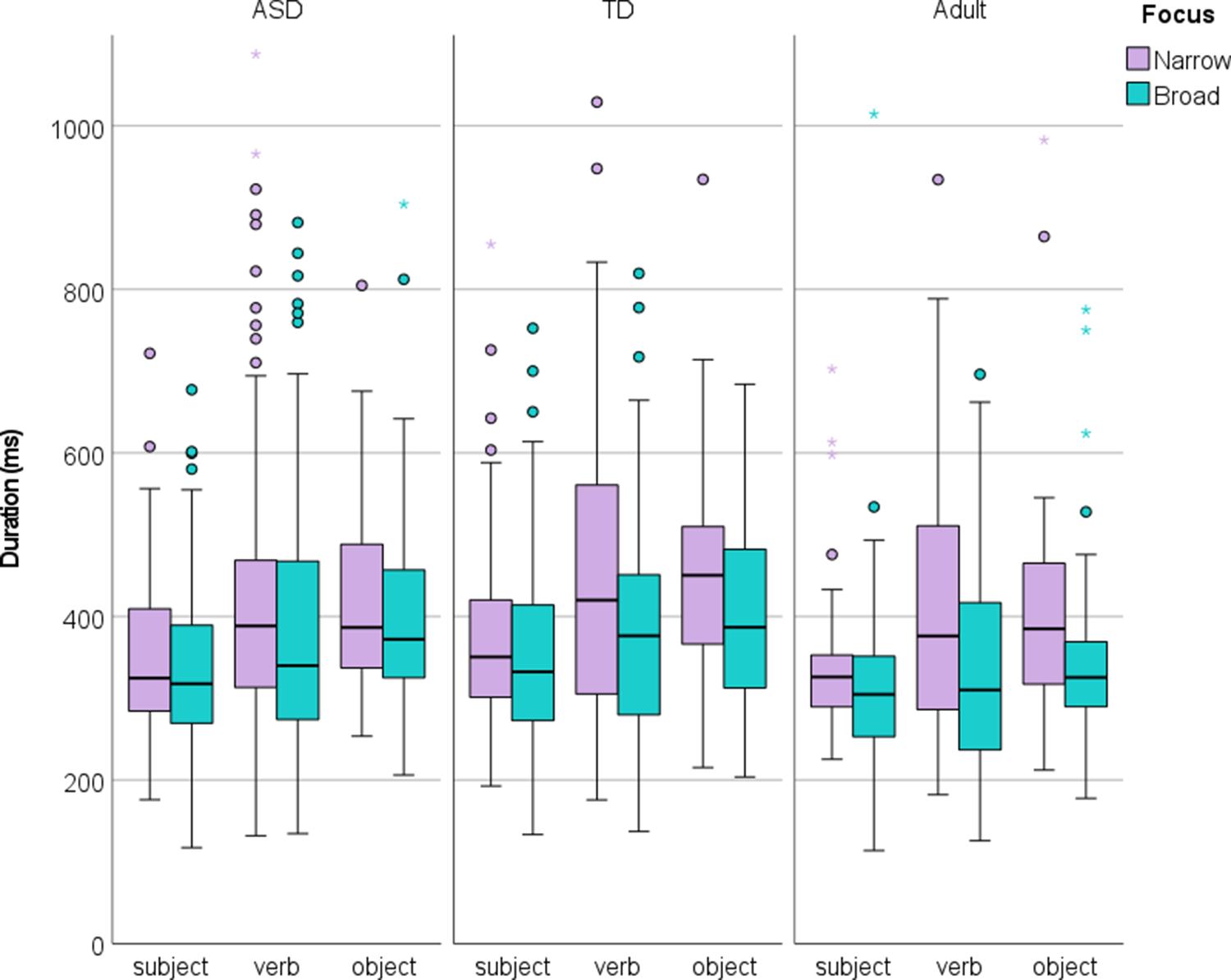

Figure 3 shows the mean duration of the focused element in three groups.

Figure 3. Mean duration of on-focus marking in three groups.

Evaluation of the model showed that the inclusion of Group (χ2(2) = 6.6546, p = .036), Focus (χ2(1) = 41.87, p < .001), Location (χ2(2) = 70.033, p < .001), Tone (χ2(2) = 8.4738, p = .014), the two-way interaction between Focus and Location (χ2(2) = 6.9594, p = .031) and the two-way interaction between Tone and Location (χ 2(4) = 29.467, p < .001) significantly contributed to the model (see Table 3). The model further revealed that Location was the strongest predictor, with medium to large effect sizes. In contrast, the main effect of Focus showed a very small effect size, indicating that focus condition alone contributed minimally to durational variation. The significant interactions involved Focus × Location and Location × Tone, reflecting how duration patterns were jointly shaped by syntactic position, focus and tone, rather than by group.

Table 3. Linear mixed-effects model on duration

Note: Duration ~ Group + Focus + Location + Tone + Focus:Location + Tone:Location +(1 + Focus|Subject) + (1|Item).

*p< .05; **p< .01; ***p< .001.

Post hoc analyses showed significant differences between narrow and broad focus across all three groups (ps < .001), indicating that all groups produced on-focus words longer in narrow focus than in broad focus. Adults produced the target on-focus syllables significantly faster than the TD group (p = .021) and marginally faster than the ASD group (p = .066). No difference was found between ASD and TD children. Across the groups, subject focus has a shorter duration than verb focus (p < .001) and object focus (p < .001), whereas verb focus and object focus had similar duration of on-focus lengthening.

Within the TD group, the optimal model indicated that the inclusion of Focus (χ2(1) = 13.626, p < .001), Location (χ2(2) = 20.726, p < .001) and English speaking proficiency (χ2(2) = 5.160, p < .023) significantly improved the model fitting. Specifically, TD children showed a longer on-focus duration in narrow focus than in broad focus (Estimate = 40.22, SE = 19.42, t(38.90) = 2.071, p = .045). Post hoc analysis revealed shorter mean duration of subject focus than verb focus (Estimate = −30.16, SE = 7.32, t(477) = −4.118, p < .001) and object focus (Estimate = −31.31, SE = 7.51, t(479) = −4.168, p < .001). But verb focus and object focus did not differ in terms of mean duration (Estimate = −1.14, SE = 7.41, t(474) = −0.154, p = .877). Moreover, TD children with higher English speaking had shorter duration of on-focus words (Estimate = −30.15, SE = 12.99, t(36.41) = −2.321, p = .026).

For the ASD group, the inclusion of Focus (χ2(1) = 15.675, p < 0.001) and Location (χ2(2) = 47.973, p < .001) significantly improved the model. To be more specific, the mean duration of narrow focus was significantly longer than that of broad focus in autistic children (Estimate = 39.361, SE = 13.15, t(23.164) = 2.994, p = .006), regardless of the location. Post hoc analysis showed that the mean duration of subject focus was significantly shorter than that of verb focus (Estimate = −31.663, SE = 5.07, t(675) = −6.246, p < .001) and object focus (Estimate = −31.465, SE = 5.15, t(674) = −6.111, p < .001), with no difference between verb focus and object (Estimate = 0.198, SE = 5.11, t(672) = 0.039, p = .969). This pattern is similar to TD children’s. The inclusion of Cantonese and English proficiency (listening and speaking) and Cantonese and English exposure in different settings did not contribute to the model fitting.

Among the participant groups, on-focus expansion of duration appeared to be less for ASD (narrow less broad focus: 23.3 ms) than TD (52.7 ms) and Adults (56.9 ms), although the interaction between Group and Focus was not found to be statistically significant.

4.3. Intensity

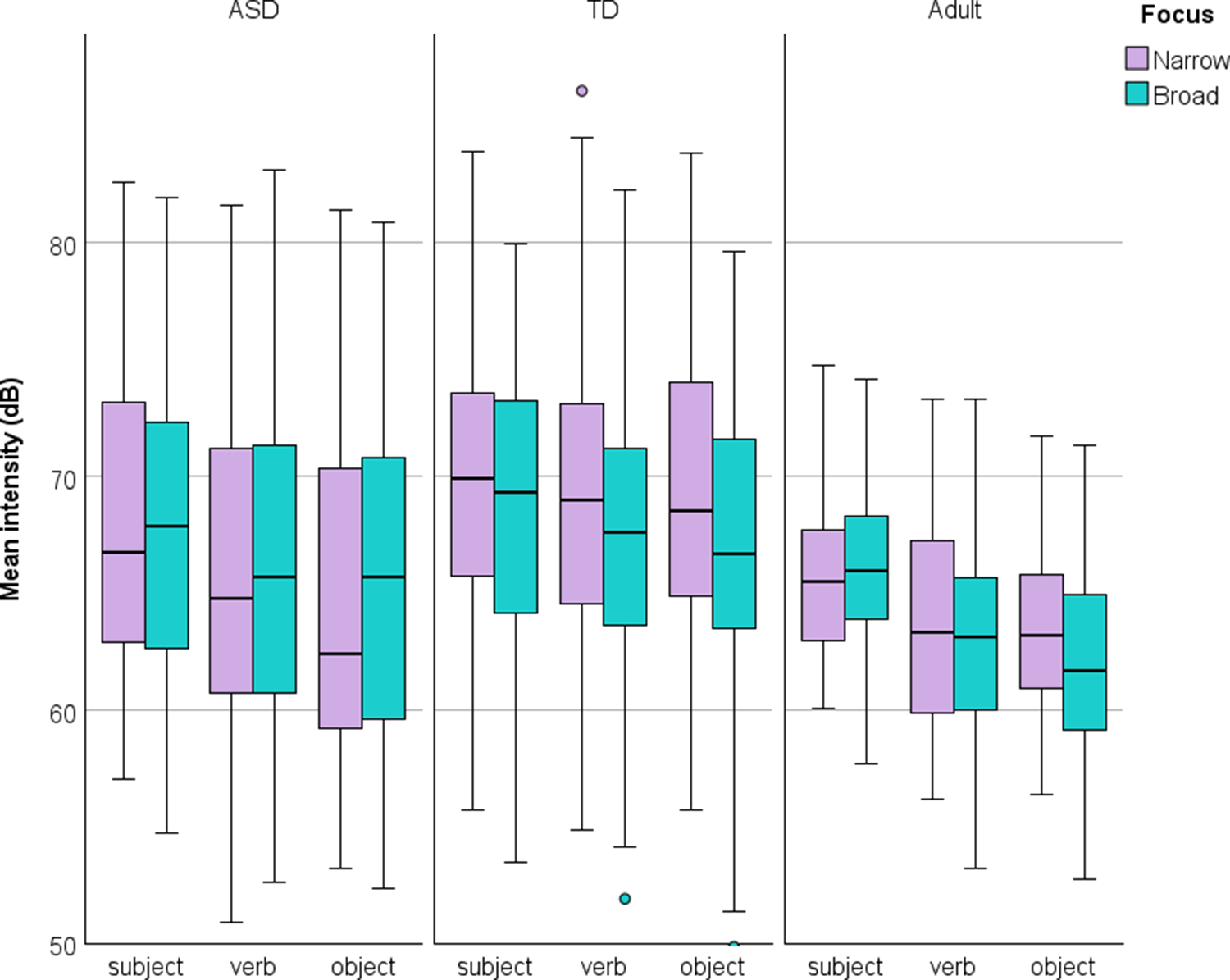

Figure 4 shows the mean intensity of the focused element in three groups.

Figure 4. Mean intensity of on-focus marking in three groups.

Evaluation of the model showed that the inclusion of Group (χ 2(2) = 6.409, p = .041), Focus (χ 2(1) = 15.031, p < .001), Location (χ 2(2) = 128.543, p < .001), Tone (χ 2(2) = 82.822, p < .001), the two-way interaction between Group and Location (χ 2(4) = 11.466, p = .022) and the two-way interaction between Group and Focus (χ 2(2) = 6.440, p = .039) significantly contributed to the model (see Table 4). The model on intensity revealed that Tone and Location were the strongest predictors, showing small to medium effect sizes. In contrast, the main effect of Focus was significant but very small, indicating that focus condition contributed minimally to intensity variation relative to tonal and positional factors.

Table 4. Linear mixed-effects model on intensity

Note: Intensity ~ Group + Focus + Location + Tone + Group:Location + Group:Focus +(1 + Focus|Subject) + (1|Item).

*p< .05; **p< .01; ***p< .001.

Post hoc analyses on each group showed a significant difference between narrow focus and broad focus in the TD group (Estimate = 1.496, SE = 0.496, t(28.870) = 3.016, p = .005) regardless of tones and focus locations, but not in the other two groups. Critically, the Group × Focus interactions were small and non-significant for both adults and autistic children, suggesting that neither group differed meaningfully from TD children in how they modulated intensity to mark narrow focus. It seems that only TD children significantly increased intensity on the focused word, whereas adults and autistic children did not.

Within the TD group, the inclusion of Focus (χ2(1) = 15.412, p < .001), Location (χ2(2) = 17.544, p < .001) and Tone (χ2(2) = 20.857, p < .001) significantly improved the model, while AoA of English and bilingual proficiency and exposure did not. Within the ASD group, the inclusion of Location (χ2(2) = 60.040, p < .001) and Tone (χ2(2) = 50.774, p < .001) significantly improved the model fitting. Surprisingly, Cantonese exposure at school also significantly improved the model (χ2(1) = 9.037, p = .003), indicating that autistic children with more Cantonese input in the school setting tended to produce focus with higher intensity. There was no effects of other bilingual proficiency and exposure found in the model fitting for autistic children.

5. Discussion

The current study examined the acoustic realization of focus in 5- to 9-year-old Cantonese-English bilingual autistic children, compared to their bilingual TD peers and adults. Both groups of children are matched in non-verbal IQ, Cantonese receptive vocabulary, working memory and maternal education. This study also explored how AoA of English, bilingual proficiency and exposure influence these acoustic correlates in bilingual autistic children.

5.1. Group differences in prosodic focus marking

Our first research question explored how bilingual autistic and TD children as well as bilingual adults use f 0, duration and intensity to produce prosodic focus in their L1 Cantonese. For bilingual adults, the results revealed that they did not employ wider pitch expansion or increased intensity to mark prosodic focus. Instead, they consistently relied on duration, lengthening focused words, to mark focus. These findings align with previous research on focus production by Cantonese-speaking adults (Fung & Mok, Reference Fung and Mok2018; Gu & Lee, Reference Gu and Lee2007; Leung & Peng, Reference Leung and Peng2015; Man, Reference Man2002; Wu & Xu, Reference Wu and Xu2010), which identified duration as the primary acoustic cue for focus marking in Cantonese, whereas pitch plays a minimal role.

It is noteworthy that the adults in our study were early sequential bilinguals, having started to acquire English before the age of three. This raises the question of whether their long-term exposure to L2 English might influence their use of pitch in L1 Cantonese focus marking. However, our findings suggest that L2 English has little impact on their prosodic focus marking in L1 Cantonese. This is consistent with prior research showing that Cantonese-English bilingual adults do not use pitch as native speakers of English do for on-focus expansion or post-focus compression in their L2 English (Fung & Mok, Reference Fung and Mok2014; Wu & Chung, Reference Wu and Chung2011). These patterns are likely attributable to negative transfer from their dominant L1 Cantonese to their non-dominant L2 English. Consequently, it is unsurprising that cross-linguistic influence from English (non-dominant) to Cantonese (dominant) was not observed in our bilingual adults.

In contrast to bilingual adults, bilingual TD children exhibited a broader use of prosodic cues for focus production. They consistently raised on-focus pitch, lengthened duration and increased intensity on focused words. These findings are consistent with Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Zhang, Zhou, Chan, Li, Li, Tang, Chun and Chen2024), which reported that Cantonese-speaking TD children used multiple prosodic cues, including pitch, duration and intensity, to mark focus. By early school age, bilingual TD children appear capable of using a range of prosodic strategies to mark focus in L1 Cantonese. The observed divergence between bilingual TD children and adults likely reflect developmental progression. While bilingual adults have fully acquired the language-specific realization of prosodic focus in Cantonese, typically doing so without relying on pitch expansion, bilingual TD children may still be in the process of exploring and refining their prosodic focus marking. Such developmental differences are not surprising, as the acquisition of prosodic focus marking continues into late childhood. For instance, previous research has shown that Mandarin-speaking children do not achieve adult-like use of pitch-related cues for focus marking until around 11 years of age (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Szendrői, Crain and Höhle2019).

Regarding autistic children, our findings show that they primarily used duration to mark focused words, similar to their bilingual adult counterparts. However, their degree of on-focus expansion was smaller relative to that of TD children and adults. This is in line with the existing studies reporting that autistic children produce less prominent contrast between on-focus and non-focus constituents (Diehl & Paul, Reference Diehl and Paul2009, Reference Diehl and Paul2013; Grossman et al., Reference Grossman, Bemis, Plesa Skwerer and Tager-Flusberg2010; Nadig & Shaw, Reference Nadig and Shaw2015; Paul et al., 2008). Critically, unlike their bilingual TD peers, autistic children did not exhibit higher pitch or increased intensity. Given that duration is considered the primary cue for focus marking in Cantonese (Fung & Mok, Reference Fung and Mok2018; Gu & Lee, Reference Gu and Lee2007; Leung & Peng, Reference Leung and Peng2015; Wu & Xu, Reference Wu and Xu2010), it is plausible that bilingual autistic children might heavily rely on this primary cue to mark prosodic focus in Cantonese while showing weaker use of secondary cues like pitch and intensity. This hypothesis is further supported by an addition analysis of creakiness (see Supplementary Materials), which is an important secondary cue for distinguishing T4 from other tones (Ho, Reference Ho2023). Our results on creakiness suggest that bilingual autistic children were less effective than their TD and adult counterparts in using creakiness to mark T4. Therefore, it appears that bilingual autistic children may depend predominantly on primary cues (i.e., duration) for prosodic focus marking, while secondary cues like pitch and intensity remain more challenging.

The performance profile of the bilingual autistic children in the current study is largely consistent with previous research examining prosodic focus marking in English-speaking and Cantonese-speaking autistic children (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Zhang, Zhou, Chan, Li, Li, Tang, Chun and Chen2024; Diehl & Paul, Reference Diehl and Paul2013; Nadig & Shaw, Reference Nadig and Shaw2015; Paul et al., Reference Paul, Augustyn, Klin and Volkmar2005; Peppé et al., Reference Peppé, Hare and Rutherford2007). Across languages, duration may emerge as a particularly salient cue for focus marking among autistic children, suggesting a cross-linguistic pattern favouring this prosodic dimension.

It is worth pointing out that autistic children demonstrated adult-like performance while TD children did not. One possibility is that in Cantonese, prosody plays a secondary role in focus marking compared to morphosyntactic devices such as focus particles and word order (Chao, Reference Chao1947; Fung, Reference Fung2000; Lee, Reference Lee2019; Matthews & Yip, 2011). This possibility is further supported by our findings that tone and syntactic position yielded substantially larger effect sizes than focus or group-by-focus interactions, across all three acoustic measures (pitch, duration and intensity). Critically, Group × Focus interactions were consistently small and largely non-significant across measures. These findings may suggest that prosodic focus marking in Cantonese is primarily achieved through structural and lexical-tonal strategies rather than prosodic devices. This language-specific strategy of focus marking is also observed in other tonal languages like Mandarin, in which where syntactic and morphological cues also prominently mark focus (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Szendrői, Crain and Höhle2019; Xu, Reference Xu2004). Previous study showed that Cantonese-speaking autistic children aged 5–9 are sensitive to these language-specific focus marking in comprehension (Ge et al., Reference Ge, Liu, Yuen, Chen and Yip2023). They perform comparably to TD children in using syntactic cues (i.e., focus particle) for focus comprehension but have greater difficulties in making use of prosodic cues for the same purpose.

5.2. Bilingualism effects

Our second research question examined how bilingualism affects the acoustic correlates of prosodic focus in autistic children. We examined the role of AoA of English, Cantonese and English proficiency, and Cantonese and English exposure in home, school and community settings. Our findings demonstrate that bilingual autistic children received similar amount of Cantonese exposure across various settings but significantly less English exposure in different settings compared to matched bilingual TD children. This discrepancy likely reflects ongoing concerns among parents and professionals in Hong Kong about the potential challenges that bilingualism poses for autistic children’s language development, consistent with prior research reporting caregivers’ cautiousness regarding bilingual exposure in autistic children (Hambly & Fombonne, Reference Hambly and Fombonne2012; Kay-Raining Bird et al., Reference Kay-Raining Bird, Lamond and Holden2012; Yu, Reference Yu2013).

For bilingual autistic children, our findings showed that increased L1 Cantonese exposure at school correlated with a lower median f 0 and higher intensity during prosodic focus marking. One possible explanation is that because Cantonese typically relies less on pitch to mark focus compared to other languages, autistic children exposed to more L1 Cantonese might compensate by placing greater emphasis on other prosodic cues, such as intensity. This compensation could result in a deliberate or subconscious lowering of their median f0 to enhance or exaggerate the use of intensity as a means of signalling focus or emphasis. In other words, our autistic children may be adapting their focus production strategies to align with the Cantonese input they receive, favouring cues that are more salient in their L1 Cantonese, which could plausibly explain the observed reduction in median f0 and increased intensity. However, Cantonese proficiency and Cantonese exposure in home and community settings did not significantly affect prosodic correlates in autistic children. Conversely, L2 English variables, including AoA of English, English proficiency and English exposure across all settings, did not significantly affect prosodic features in bilingual autistic children’s L1 Cantonese. This finding is consistent with the growing consensus that L2 proficiency and exposure does not negatively impact L1 skills in autistic children (Beauchamp et al., Reference Beauchamp, Rezzonico and Macleod2020; Dai et al., Reference Dai, Burke, Naigles, Eigsti and Fein2018; Ge et al., Reference Ge, Lee, Liu, Yuen and Yip2024; Gonzalez-Barrero & Nadig, Reference Gonzalez-Barrero and Nadig2017; Hambly & Fombonne, Reference Hambly and Fombonne2012; Meir & Novogrodsky, Reference Meir and Novogrodsky2020; Ohashi et al., Reference Ohashi, Mirenda, Marinova-Todd, Hambly, Fombonne, Szatmari and Thompson2012; Petersen et al., Reference Petersen, Marinova-Todd and Mirenda2012; Valicenti-McDermott et al., Reference Valicenti-McDermott, Tarshis, Schouls, Galdston, Hottinger, Seijo and Shinnar2013; Zhou et al., Reference Zhou, Munson, Greenson, Hou, Rogers and Estes2019).

In contrast, the effects of bilingualism were more pronounced among bilingual TD children. In terms of L1 experience, bilingual TD children with stronger Cantonese listening proficiency exhibited lower median f0 in production. This pattern was similar to what found in bilingual autistic children, suggesting that increased L1 experience and proficiency may facilitate an adjustment towards Cantonese focus marking strategies in both groups of children. They might thus lower their median f0 in order to enhance other use of prosodic cues in focus production. Crucially, while no L2 effects were found in bilingual autistic children, our bilingual TD children showed divergent patterns: earlier AOA of English demonstrated lower median f0 in production, while those with higher English speaking proficiency produced shorter durations for on-focus words. These results were consistent with research on typical bilingual development, where cumulative bilingual experience and proficiency shape the acoustic realization of prosody – including pitch, segmental features and intonation – in both languages (Hambly et al., Reference Hambly, Wren, McLeod and Roulstone2013; Lee & Zhang, Reference Lee and Zhang2023; Queen, Reference Queen2001; Schmidt & Post, Reference Schmidt and Post2015a,Reference Schmidt and Postb; Zembrzuski et al., Reference Zembrzuski, Marecka, Otwinowska, Zajbt, Krzemiński, Szewczyk and Wodniecka2020). This cross-linguistic prosodic adjustment is notable given the typological differences between Cantonese and English in focus realization.

Our findings indicate that bilingualism may affect autistic and TD children in a different way in terms of prosodic focus production. One possible explanation is that bilingual autistic children in our study received significantly less English exposure and began learning English much later than their bilingual TD peers. More specifically, this earlier exposure and greater experience in L2 in our bilingual TD children likely accounts for the stronger bilingualism-related prosodic effects observed in this group. In contrast, the later and reduced English exposure in autistic children probably contributes to their dominance in Cantonese. Since language dominance was found to be a factor to determine the directionality of cross-linguistic influence in bilingual language acquisition (Ge et al., Reference Ge, Matthews, Cheung and Yip2017; Yip & Matthews, Reference Yip and Matthews2000), it is plausible that dominance in Cantonese might make language transfer unlikely to occur from a less dominant language (English) to a more dominant language (Cantonese) in the production of bilingual autistic children in the present study. Collectively, these findings illustrate that the interaction between bilingual exposure and ASD impacts prosodic focus marking in complex ways.

5.3. General discussion, limitations and future directions

This study examined prosodic focus production in Cantonese-English bilingual autistic children aged 5–9, comparing their abilities to those of their bilingual TD peers and adults. Our findings suggest that while bilingual autistic children can use duration to produce prosodic focus in L1 Cantonese, they showed different cue-weighting patterns within L1 Cantonese prosody compared to their TD peers. We found no evidence that L2 English exposure was adversely related to L1 Cantonese prosodic focus correlates (pitch, duration and intensity) in autistic children, and effects on focus production were limited to L1 Cantonese exposure correlations.

Overall, our findings complement and extend the previous research in numerous ways. First, our study provides new empirical evidence of how bilingual autistic children produce prosodic focus from the perspective of objective acoustic measurements. Second, our study is among the few to explore how bilingual exposure and proficiency affects autistic children exposed to two typologically different languages. Our findings further indicate that bilingualism does not impede autistic children’s prosodic focus marking in their L1. These findings can guide parents, clinicians, educators and other professionals who make language decisions for autistic children in bilingual communities. Parents and professionals can engage autistic children in bilingual environments, as bilingual exposure does not appear to negatively affect L1 Cantonese focus production in autistic children, based on the acoustic measures examined in this study.

The current study has several limitations that should be considered. First, it examined the effects of bilingualism on ASD using only one linguistic structure and in one language, which limits the generalizability of the findings. Future research can investigate a broader range of linguistic structures across both languages of bilingual autistic children to provide a more comprehensive understanding. Second, our sample consisted of autistic children with relatively strong language and cognitive skills, which may have masked differences compared to TD peers. Further studies are needed to explore the impact of bilingual exposure on autistic children with more pronounced verbal communication challenges.

Another consideration is whether the task employed in this study accurately reflects naturalistic prosodic use or whether performance may have been influenced by task demands such as memory or cognitive load. Furthermore, since Cantonese relies more heavily on morphosyntactic strategies for focus marking, it is possible that participants who did not use acoustic cues might have instead employed morphosyntactic means, indicating different marking preferences rather than impairments. This highlights the need for further research to disentangle these effects.

Our finding that bilingual autistic children used duration cues but not intensity contrasts with some previous studies, suggesting that prosodic cue weighting may vary depending on population and language context. More comparative research is required to better understand these differences. It is also important to recognize that bilingualism is neither strictly categorical nor easily quantifiable. Parent reports of language proficiency, particularly when parents are non-native speakers of one language, may be subjective or biased, potentially affecting the accuracy of bilingualism assessments. Finally, while this study concentrated on prosodic production, investigating speech perception in bilingual autistic children would provide valuable complementary insight, as perception and production are closely interconnected in language development.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/S1366728925100953.

Data availability statement

The data that support the results of this study are available upon request and approval from the Research Ethics Committee of Hong Kong Metropolitan University.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the children and their families who participated in this study and gratefully acknowledge the support from Heep Hong Society. We thank Arlene Lau and Christina Chan for their assistance with the study. This work was substantially supported by a grant to the first author from the Hong Kong Metropolitan University – Research and Development Fund (Project Reference No.: RD/2021/02).

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ethics statement

This study was approved by the University Ethics Committee of Hong Kong Metropolitan University (No.: HE-RD2021/02).