Introduction

The long-tailed goral Naemorhedus caudatus is a montane ungulate that dwells in rocky terrain and forests at high altitudes, where it forages on mosses, grasses, herbs and shrubs (Won, Reference Won1967; Mead, Reference Mead1989; Cho et al., Reference Cho, Kim, Kim, Lee, Son and Jung2016). Within this environment, it prefers steep cliffs or high slopes with good vantage points from which to watch for predators (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Baccus and Koprowski2018). Males are usually solitary, whereas females form small groups with their kids (Lovari & Apollonio, Reference Lovari and Apollonio1994; Mishra & Johnsingh, Reference Mishra and Johnsingh1996).

Naemorhedus spp. are distributed across Asia from the Russian Far East through China to the Himalayas (Mead, Reference Mead1989) in areas with mean annual temperatures < 12 °C (Kim, Reference Kim2023). The long-tailed goral Naemorhedus caudatus is restricted to the Korean Peninsula and adjacent regions in China and Siberia at high altitudes with low temperatures (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Baccus and Koprowski2018). In South Korea, long-tailed gorals have been reported in Gangwon, Chungbuk and Gyeongbuk Provinces (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Baccus and Koprowski2018). There have been some regional studies (Mead, Reference Mead1989), and Won (Reference Won1990) estimated there were < 30 long-tailed gorals remaining in the wild, in the demilitarized buffer zone between North and South Korea. No nationwide survey of goral distribution had been conducted in South Korea prior to this study.

Since the beginning of the 21st century, the Korean National Park Service has been working on a recovery project for gorals in Mt Seorak National Park in the north-east and Mt Wolak National Park in central South Korea. Captive breeding and release are carried out by both the National Park Service and some local governments, such as in Yanggu-gun county in the north. As a result of these recovery efforts, the current population of gorals in South Korea is estimated to be c. 1,000, concentrated in the north-east (Bragina et al., Reference Bragina, Kim, Zaumyslova, Park and Lee2020). The main threats to their survival in South Korea are habitat loss and poaching (National Institute of Biological Resources, 2012; Bragina et al., Reference Bragina, Kim, Zaumyslova, Park and Lee2020).

Several studies underpin goral conservation efforts in South Korea. These include works on home range and seasonal habitat use in Mt Wolak National Park and local-scale habitat modelling in Mt Wolak and Mt Seorak National Parks (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Kim, Gyun, Yang, Lee and Gyun2014, Reference Cho, Kim, Kwon, Kim, Lee and Son2015a,Reference Cho, Kim, Kwon, Kim, Lee, Song and Parkb). The influence of forest type, slope, altitude, aspect, roads and water on goral distribution have been assessed (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Kim, Kwon, Kim, Lee and Son2015a,Reference Cho, Kim, Kwon, Kim, Lee, Song and Parkb) as have the impacts of anthropogenic disturbance and climate variables (Park, Reference Park2011; Lee et al., Reference Lee, Kim and Bhang2019). Few studies have addressed the distribution and habitat use of gorals at the landscape level, especially in East Asia, but it is expected that habitat availability will decrease as a consequence of climate change (Hotta et al., Reference Hotta, Tsuyama, Nakao, Ozeki, Higa and Kominami2019). Habitat loss and fragmentation are considered major threats (Cho et al., Reference Cho, Kim, Kwon, Kim, Lee, Song and Park2015b), with paved roads and railways a particular cause of habitat fragmentation for all wildlife (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee, Woo, Kim, Wallace and Jo2021). Gorals are highly sensitive to disturbance and are rarely seen by people, although they have been observed in the vicinity of power-transmission towers and military installations (B. Jo, pers. comm., 2022).

Naemorhedus caudatus is categorized as Vulnerable on the IUCN Red List and the species is listed on CITES Appendix I (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Baccus and Koprowski2018; Bragina et al., Reference Bragina, Kim, Zaumyslova, Park and Lee2020; CITES, 2025). It is listed as Category I in the Russian Red Data Book; as Natural Monuments No. 293 and No. 356 (1980) in North Korea, together with its habitat; as Endangered Species Category I (1997) and Natural Monument No. 227 (1968) in South Korea; and as Protection Class II in China (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Baccus and Koprowski2018; Bragina et al., Reference Bragina, Kim, Zaumyslova, Park and Lee2020). Population recovery plans are in place in these countries, but without more ecological information, conservation and management efforts are constrained (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Won, Fritts, Wallace and Baccus2017).

Species distribution models are essential for documenting change and guiding conservation planning (Trisurat et al., Reference Trisurat, Bhumpakphan, Reed and Kanchanasaka2012). We present the first distribution map for the species in South Korea, and identify predictors of goral presence, to help address the general scarcity of ecological information on this species and provide data to guide its conservation.

Study area

Since World War II and the Korean War, South Korea has occupied the southern half of the Korean Peninsula between 33–38°N and 125–131°E (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Won, Fritts, Wallace and Baccus2017). There were c. 51 million inhabitants in June 2024, with 90% of the population concentrated in urban regions (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Won, Fritts, Wallace and Baccus2017). Over 70% of the country is covered by forested mountains, mainly lying along the Baekdudaegan Mountain Range in the north-east. Jiri Mountain at 1,915 m is the highest peak of mainland South Korea (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee, Woo, Kim, Wallace and Jo2021). The climate of South Korea is temperate, with four distinct seasons. Monthly mean temperatures are 6–16 °C, with regional differences between continental and coastal areas dependent upon variations in topography, latitude and air currents (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Won, Fritts, Wallace and Baccus2017). The total annual mean precipitation is 1,200 mm, with 50–60% of rainfall occurring during the summer monsoon of June–August (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Baccus and Koprowski2018). Land cover comprises 38.2% deciduous forest, 25.6% coniferous forest, 27.6% agricultural land 4.5% grasslands, and 4.1% urban and unvegetated areas (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Won, Fritts, Wallace and Baccus2017). The main vegetation zones are warm temperate forest, cool temperate forest (southern, central and northern) and subarctic forest (Yim & Kira, Reference Yim and Kira1975).

Methods

Firstly, we compiled available occurrence information on the long-tailed goral to use as input data for modelling the species’ distribution and thus identify sites for field surveys, from the results of which we then developed a distribution map (Fig. 1). Secondly, we modelled goral presence using a suite of environmental and anthropogenic predictors.

Fig. 1 Schematic illustration of the method used to derive a distribution map of the long-tailed goral Naemorhedus caudatus in South Korea.

Distribution map

We obtained the coordinates of long-tailed goral sightings during 2008–2017 from the National Institute of Biological Resources wildlife and endangered species surveys and the Korean National Parks Service monitoring surveys covering every national park in South Korea. Field data were mainly gathered from signs and camera traps. To reduce spatial bias, we retained only one point when several locations were recorded within 50 m of each another, deleting nearby points, resulting in 641 records to be used as the response variable.

To focus our field surveys on potential goral habitat in South Korea, we developed a distribution model based on these records, using the maximum entropy method, with MaxEnt 3.4.3 (Phillips et al., Reference Phillips, Dudik and Schapire2004), to select sites. We used 23 raster datasets as potential predictors of goral presence (Table 1). These comprised 19 bioclimatic variables, elevation and land-cover data, anthropogenic disturbance (human footprint) and light pollution (see Table 1 for all sources). All datasets were standardized to 30 × 30 m using the Extract by Mask function in ArcGIS 10.5 (Esri, USA) so that they had the same shape and geographical dimensions as the land-cover map of South Korea.

Table 1 Environmental variables used in MaxEnt to model the distribution of the long-tailed goral Naemorhedus caudatus in South Korea for the identification of sites for field surveys.

1 WorldClim 2.1 (Fick & Hijmans, Reference Fick and Hijmans2017). 2SEDAC (2025). 3EGIS (2025). 4NCEI (2025).

In MaxEnt, we set random test per cent to 25, replicates to 50, maximum iterations to 5,000, selected subsample for replicated run type, and random seed; the MaxEnt defaults were used for other settings. We used the area under the receiver operating characteristic curve (AUC) to test model fitness.

After creating the MaxEnt distribution model, we categorized values on a scale from unsuitable habitat (0) to the most suitable habitat (10) using the Reclassify function in ArcGIS. The reclassified model was overlaid with a nationwide 10 × 10 km Universal Transverse Mercator (UTM) grid, comprising 1,027 cells (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Won, Fritts, Wallace and Baccus2017). We selected grid cells with MaxEnt values > 5 (median value of habitat suitability) for field investigation. We excluded UTM grid cells from islands as there were no records of gorals in these locations.

During January 2019–May 2022, we surveyed the 364 of the 1,027 grid cells that had a MaxEnt value > 5. These field surveys were paused for biosecurity during an African swine fever outbreak in wild boar Sus scrofa in Korea from October 2019 to March 2020. To ensure reliabilty, only field mammalogists with > 10 years experience conducted the surveys, supported by 1–2 assistants. The team investigated potential goral habitat patches, specifically rocky areas and cliffs with trails, which gorals frequently use. These areas were intensively searched for goral signs such as droppings, footprints and horn rubs, which are readily identifiable by experienced mammalogists as there are no other wild bovids in Korea. Where goral presence was detected, coordinates were recorded. To avoid sampling bias, if multiple signs were found within 50 m, only one coordinate point was retained. Because each surveyed grid cell often contained several potentially suitable habitat patches, a total of 1,232 sites were searched.

We set up camera traps (BTC-8A, Browning, USA; Reconyx Hyperfire PC900, Reconyx Inc., USA; Moultrie M990i, Moultrie, USA; Mini301, SuntekCam, Shenzhen Qiyue Intelligent Technology, China) on potential goral trails in 241 survey grid cells where we found no evidence of goral presence. During January 2019–May 2022, we operated the cameras for 6–24 months, and re-investigated camera-trapping sites for goral signs a second time upon retrieval of the cameras. In cases where a camera was lost (disappeared or broken), we replaced it but at a different location in the same grid cell. We deployed a total of 340 camera traps in 241 of the 364 grid cells where the field surveys did not reveal any sign of gorals. Grid cells were classified as detections or non-detections depending upon goral presence.

Predictors of goral presence

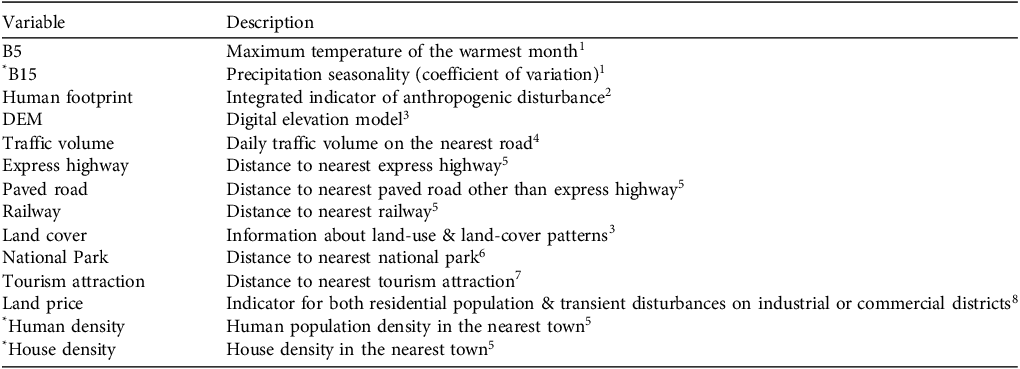

We considered a set of 14 environmental and anthropogenic factors as potential explanatory variables for modelling the presence of the long-tailed goral (see Table 2 for all sources). For each variable we added its respective value to the detection/non-detection data points (892 and 340, respectively; see Results).

Table 2 Environmental and anthropogenic variables used to determine the habitat requirements, with linear mixed-effects models, of the long-tailed goral in South Korea.

* Variables with high correlation (r > 0.9) and/or a variance inflation factor > 10 were omitted from the regression model because of high multicollinearity.

We selected the top three variables that contributed > 5% to the MaxEnt model (maximum temperature of the warmest month, precipitation seasonality, human footprint), and digital elevation model (DEM), to reflect the species’ preference for high altitudes. We used the Extract multi values to points function in ArcGIS to add the raster values of each variable.

As in South Korea the long-tailed goral mostly inhabits undisturbed montane habitats (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Baccus and Koprowski2018), we selected four additional variables representing anthropogenic disturbance. No incidents of goral fatalities were reported in a road-kill survey during 2007–2017, despite the dense road system in South Korea (Lee, Reference Lee2023). Other threatened mammals such as the leopard cat Prionailurus bengalensis, Eurasian otter Lutra lutra and yellow-throated marten Martes flavigula were recorded as road-kill, suggesting gorals may avoid traffic. Therefore, we considered traffic volume and distance to the nearest express highway, other paved road and railway as habitat variables. For traffic volume, we added daily traffic data from 2021 collected from 3,840 traffic monitoring stations using the Spatial join function in ArcGIS and selecting options Join one to one and Closest. We calculated distances to the nearest express highway, paved road and railway using the Near function in ArcGIS with the Geodesic option.

As the long-tailed goral has a preference for rocky areas and cliffs (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Baccus and Koprowski2018), we used the most recent (2013) high-resolution land-cover map (5 × 5 m). We used the Extract multi values to points function in ArcGIS to add land-cover raster values.

We selected five additional variables to examine the impacts of anthropogenic activities on the long-tailed goral: the most recent data on distances to the nearest national park and tourist attraction, land price, human density and house density. We calculated distances using the Near function in ArcGIS and added house density, human density and land price values using the Spatial join function with the Intersect option.

Although presence-only raster-based species distribution models such as MaxEnt (which we used to identify sites for field surveys) are commonly used for predicting presence because of their ease of use (Braunisch et al., Reference Braunisch, Coppes, Arlettaz, Suchant, Schmid and Bollmann2013; Álvarez-Martinez et al., Reference Álvarez-Martínez, Suárez-Seoane, Stoorvogel and de Luis Calabuig2014), they have limitations such as being dependent on spatial resolution and susceptible to sampling bias (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Won, Fritts, Wallace and Baccus2017). To overcome these shortcomings, we employed a presence–absence model (Brotons et al., Reference Brotons, Thuiller, Araújo and Hirzel2004), using presence (detection) and absence (non-detection) points in a linear mixed-effects model to predict goral presence (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee, Woo, Kim, Wallace and Jo2021).

We used a binomial response variable, where detection points were coded as 1 and non-detection points as 0. To address multicollinearity, we first removed any highly correlated environmental or anthropogenic variables (correlation coefficient > 0.8). We then further assessed collinearity of continuous predictors using the variance inflation factors (VIF), eliminating variables with high correlation (r > 0.9) and/or high VIF (> 10; Zuur et al., Reference Zuur, Ieno and Elphick2010). After this selection process, we removed precipitation seasonality, human density and house density, leaving 11 non-correlated explanatory variables. We standardized each by subtracting its mean and dividing by its standard deviation.

We generated linear mixed-effects models using LME4 in R 4.2.1 (R Core Team, 2022). We generated 2,048 models representing all possible combinations of the 11 explanatory variables. Models were compared using the conditional Akaike information criterion (cAIC, adjusted for a mixed-effects model) with the package cAIC4. Following standard procedure (Burnham & Anderson, Reference Burnham and Anderson2002), we only present the models with strong support (ΔcAIC < 2) for further interpretation.

Results

Distribution map

We identified goral presence at 892 (72.4%) of the 1,232 sites searched during our field survey and confirmed presence in 123 of the 364 surveyed grid cells (33.8%; Fig. 2). Gorals were not detected by the 340 camera-trap stations within 241 survey grid cells, nor were any signs of presence found in the second field survey in these grid cells following camera trapping. Gorals were mostly confined to the north-eastern and central-eastern mountains. Despite extensive search efforts in the southern mountains, we detected no signs of goral presence south of latitude 36°16′N.

Fig. 2 Long-tailed goral detection (presence) and non-detection (absence) locations in South Korea (2019–2022). The map shows goral presence and absence at 892 and 340 sites, respectively, across a 10 × 10 km grid system. Dark grey grid cells are those where the species was detected at ≥ 1 survey sites within the cell (123 cells), and light grey grid cells are those where the species was not detected at any survey site within the cell (241 cells).

The MaxEnt distribution model used to identify sites for the field survey was a relatively good fit (AUC 0.963 ± SD 0.003). The variables contributing most to the model were maximum temperature of the warmest month (46.2%), precipitation seasonality (16.8%), human footprint (12.5%), precipitation of coldest quarter (3.7%), and mean diurnal temperature range (3.0%). The other 18 variables, including land cover (1.3%), elevation (1.1%) and light pollution (0.2%), contributed < 3% to the model in total.

The mean elevation of sites where we detected the goral was 589 ± SD 241 m, (range 10–1,305 m, median 580 m), with 69.1% of sites located at 400–800 m (< 400 m, 12.2%; > 800 m, 18.7%). The mean elevation at non-detection sites was 551 ± SD 286 m (median 543 m). We detected most gorals (97.7%) in forest (56.6% coniferous forest, 24.4% deciduous forest, 16.7% mixed forest). Grassland (0.7%), wetland (0.7%), barren land (0.3%), roads (0.3%) and cultivated fields (0.2%) occurred in < 1% of the sites where gorals were found.

Predictors of goral presence

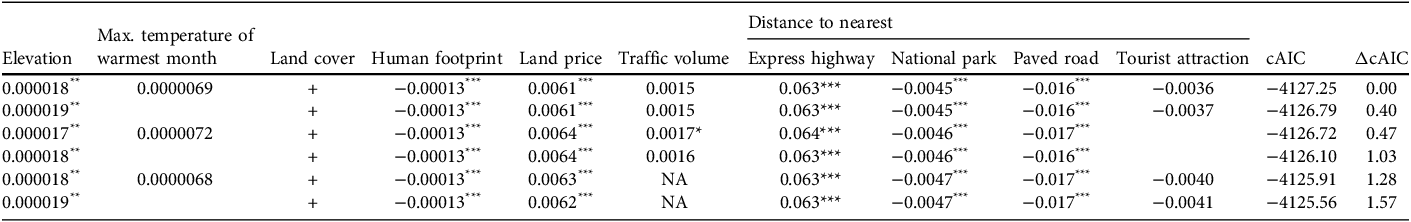

Six of the 2,048 linear mixed-effects models had ΔcAIC < 2 (Table 3), and all included elevation, land-cover type, human footprint, land price, and distances to nearest express highway, other paved road and national park. Traffic volume and distance to nearest tourist attraction had strong support in four of the six models, and maximum temperature of the warmest month was included in three models. Although distance to the nearest railway appeared frequently in the top 48 models (ΔcAIC < 2), this variable did not appear in the top six models.

Table 3 In ascending order of their conditional Akaike information criterion (cAIC), the table shows the coefficients for the top six linear mixed-effects models (i.e. ΔcAIC < 2 compared to the best-performing model) for the prediction of long-tailed goral occurrence (based on both presence and absence) from 11 environmental and anthropogenic variables. Distance to the nearest railway was not included in any of these top six models. Blank cells indicate the absence of a variable in that model.

*** P < 0.001; **P < 0.01; *P < 0.05.

+ indicates a categorical variable (i.e. there is no coefficient value).

Discussion

Our study is the first comprehensive nationwide survey of the distribution of the long-tailed goral in South Korea. Although earlier regional surveys of Mt Seorak National Park and Uljin-Samcheok in the east found evidence of gorals, other potential areas were overlooked (Yang, Reference Yang2002; National Institute of Biological Resources, 2012, 2020; Cho, Reference Cho2013). It is likely that goral distribution in South Korea has been previously underestimated because of low search effort. Using a combination of distribution modelling and field surveys, we were able to build a distribution map that, in combination with the model that identifies the predictors of goral presence, can be used to monitor and protect the remaining goral populations.

Although elevation made a minor contribution to the MaxEnt model (1.1%, ranked 14th of 22 variables), it was a significant component in all top six linear mixed-effects models, reflecting the species’ preference for rugged terrain in undisturbed montane habitats (Jo et al., Reference Jo, Won, Fritts, Wallace and Baccus2017). Our field surveys corroborated this, with more detections at higher elevations. Note that these results reflect both the concentration of surveys in mountainous areas and habitat suitability (J.W. Duckworth, pers. comm., 2024). It is evident that the distribution of the long-tailed goral in South Korea overlaps with the Baekdudaegan mountain range and its western branches. Although gorals are typically found in colder regions, they tend to prefer rocky areas that have higher temperatures during the warmest month, and the inclusion of maximum temperature of the warmest month in the linear mixed-effects models had a marginally positive relationship with goral detection.

The long-tailed goral showed a strong preference for forested areas, particularly coniferous forests, similar to its congener, the Himalayan goral Naemorhedus goral (Sherpa, Reference Sherpa2016). Coniferous forests, comprising species such as Korean red pine Pinus densiflora and Korean pine Pinus koraiensis, have an open understorey that provides good visibility and helps gorals remain vigilant for predators. Note that although we primarily recorded goral signs in rocky or barren areas, these presence points were classified as forest on the land-cover map because of the map’s low-resolution (30 × 30 m) scale.

Human footprint is an integrated indicator of anthropogenic disturbance (Venter et al., Reference Venter, Sanderson, Magrach, Allan, Beher and Jones2016) and was a significant negative predictor of goral presence in all six top linear mixed-effects models. Although there was a negative relationship between goral presence and distance to the nearest express highway, distance to the nearest railway was not a significant predictor of goral distribution. In Mongolia, railways have significant effects on the Mongolian gazelle Procapra gutturosa and wild ass Equus hemionus, with these animals rarely crossing them (Ito et al., Reference Ito, Lhagvasuren, Tsunekawa, Shinoda, Takatsuki, Buuveibaatar and Chimeddorj2013), and there is a high incidence of ungulate mortality around railways (D. Lkhagvasuren, pers. comm., 2023). However, railways in South Korea rarely penetrate goral habitat. In contrast, the road system is well developed, extending into remote montane areas, including the rugged terrain that gorals prefer, and paved roads were consequently a significant predictor of goral presence. In the civilian control zone adjacent to the demilitarized buffer zone with North Korea, where hunting and poaching is impossible, gorals are frequently observed on paved roads.

Highways not only result in wildlife–vehicle collisions but also act as a barrier, reducing available habitat and discouraging gorals from approaching where traffic levels are high (Gagnon et al., Reference Gagnon, Schweinsburg, Dodd, Irwin, Nelson and McDermott2007). Daily traffic volume should be a good indicator of anthropogenic activity (Lee et al., Reference Lee, Lee, Woo, Kim, Wallace and Jo2021) but even though traffic volume was a predictor of goral presence in four of the top six models, it was positive rather than negative, as expected. This may be because the traffic volume monitoring stations were not close to goral habitats and therefore traffic volume data did not directly reflect this anthropogenic disturbance.

Land price was a significant predictor of goral distribution. Both detection and non-detection points are in undeveloped montane regions far from urban areas and with uniform land prices. Conversely, there was a positive relationship between goral detection and proximity to National Parks (in all six top models) and tourist attractions (in four of the top models). Long-tailed gorals have been reintroduced to some national parks, increasing their numbers and the likelihood of detection.

The value of the linear mixed-effects models is that they identified a suite of variables that differed between detection and non-detection points, confirming in particular that gorals are sensitive to various indicators of anthropogenic disturbance and avoid locations where people are present. As South Korea is densely populated, wildlife disturbance is ubiquitous but we were able to identify key habitat features for gorals that provide practical criteria for selecting potential recovery sites; in particular, highlands with low human activity and areas distant from express highways.

Poaching of the long-tailed goral in South Korea has diminished in recent decades: historical data show c. 3,000 gorals were poached in 1965 (Won, Reference Won1967), whereas according to a report by the Ministry of Environment only two goral poaching cases were officially reported between 2019 and 2023 (authors, unpubl. data). However, alongside habitat loss, the construction of fences to halt the spread of African swine fever (from late 2019 to 2022) presents a new threat to the species by exacerbating habitat fragmentation and isolation. Consequently, small goral populations could shrink further. Areas beyond national parks are challenging habitats for this sensitive species. To effectively conserve the goral population in South Korea, and to facilitate its recovery, connecting populations within national parks must be prioritized. Our model of the predictors of goral presence could be used to design suitable habitat corridors that mitigate anthropogenic disturbance.

In summary, we found signs of the long-tailed goral in 72% of the field sites surveyed and confirmed their presence in 34% of 364 survey grid cells across South Korea. Goral presence was concentrated in the north-eastern and central-eastern mountains north of latitude 36°16′N, in rocky areas and forests at 400–800 m elevation. Proximity to protected areas and low levels of anthropogenic disturbance were also important. We recommend that future research focuses on refining predictive models and expanding survey efforts to cover other potential habitats across the species’ range in South Korea. Our approach could also be of value for studies investigating goral distribution and habitat in other countries.

Author contributions

Study design: YSJ; fieldwork: HJL, OSL, CUC, YSJ, HBP; data analysis: YSJ; writing, revision: YSJ.

Acknowledgements

This study was supported by the National Institute of Biological Resources and the Korea National Park Service of South Korea. We thank J.W. Duckworth for valuable comments and insights; G. Kim for help with the references; and the reviewers for their invaluable feedback.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards.

Data availability

The data supporting this study are available from the wildlife survey report at the Ministry of Climate, Energy and Environment (2025).