Introduction

Structural ageing has become a hallmark of Western European societies. In Italy, the proportion of residents aged 65+ rose from 9.3 per cent (4.5 M) in 1961 to 22.5 per cent (13.7 M) in 2021. Structural ageing is a multifaceted issue with localized effects, but it is also closely linked to broader political-economic processes (Walker and Foster Reference Walker and Foster2014). Among the various challenges it poses, older adults’ experiences of urban living – and their capabilities to age in place (Buffel and Phillipson Reference Buffel and Phillipson2024) – are shaped by initiatives aimed at mitigating their socio-economic impacts. Such initiatives are often inspired by internationally circulating policy models that promote age-friendly planning strategies designed to foster ‘active’ and ‘successful’ forms of ageing (Rowe and Kahn Reference Rowe and Kahn1997).Footnote 1 Nonetheless, critical gerontological studies argue that Western ‘active ageing’ policies are consistently informed by neo-liberal logics of self-responsibility, independence and individualism (Rubinstein and de Medeiros Reference Rubinstein and de Medeiros2015). Furthermore, various forms of exclusion related to class, race, gender and other inequalities intersect with normative definitions of ‘good ageing’ (Finlay et al. Reference Finlay, Gaugler and Kane2020).

A compelling issue relates to how older adults navigate urban spaces, including their interactions with variegated mobility systems, the features of their living environments and their psycho-physical conditions of (im)mobility (Cheng et al. Reference Cheng, Wang and Paez2023). Although mobilities studies are considered to be an innovative field in contemporary social sciences (Sheller Reference Sheller2021), they have only intermittently explored older adults’ experiences (Luoma-Halkola Reference Luoma-Halkola2025). While this literature draws on a range of international contexts, the present article is empirically grounded in research conducted in the city of Brescia (Northern Italy). Yet the field still lacks approaches that comprehensively address the challenges older adults face in their everyday urban (im)mobilities (Ciobanu and Hunter Reference Ciobanu and Hunter2018), as well as integrated theory-making efforts bridging critical gerontology and mobilities studies (Gatrell Reference Gatrell, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2017; Murray and Robertson Reference Murray and Robertson2015). Understanding the relationships between older adults’ diverse conditions of being (im)mobile and ageing processes contributes to shaping more effective and equitable mobility policies. Integrating reflections on the socio-environmental production of ageing processes with discussions on mobility justice (Sheller Reference Sheller2018) expands our understanding of older adults’ experiences. This broadens the scope of (im)mobile experiences, framing them as crucial to ageing processes (Luoma-Halkola Reference Luoma-Halkola2025). It also questions under-theorized connections drawn between older adults’ specific conditions of (im)mobility and (supposedly) corresponding definitions of agency or passivity, autonomy or dependency, and movement or stillness (Sheller Reference Sheller2021) – with driving often taken to quintessentially represent autonomous mobility, and its cessation equated with immobility and passivity (e.g. Pellichero et al. Reference Pellichero, Lafont, Paire-Ficout, Fabrigoule and Chavoix2021). This article focuses on older adults’ diverse experiences of automobility, conceptualizing mobilities and ageing as mutually constitutive. Specifically, automobilities primarily emerge as relational fields where ageing processes unfold, revealing the complexity of crafting policies enhancing ‘altermobilities’ (Manderscheid Reference Manderscheid2014b) that account only for how ageing processes influence mobility (Mansvelt Reference Mansvelt, Adey, Bissell, Hannam, Merriman and Sheller2014), without addressing how mobility practices themselves crucially shape experiences of ageing. This article explores the relational systems embedded in older adults’ automobilities in Brescia. By examining older adults’ everyday practices and narratives, it emphasizes the need to move beyond a simplistic focus on movement alone, towards a conceptualization of being (im)mobile that recognizes the relational, situated and processual dimensions of ageing.

Older adults, ageing processes, mobilities

In international transport literature, older adults’ mobility is a significant sub-field of research (Villena-Sanchez and Boschmann Reference Villena-Sanchez and Boschmann2022). Key themes include older adults’ travel choices and behaviours (e.g. Musselwhite and Murray Reference Musselwhite, Murray, Potoglou and Spinney2024); the characteristics of built environments (e.g. Yuan et al. Reference Yuan, Xu and Zhao2023) and different forms of ‘capital’ (Musselwhite and Scott Reference Musselwhite and Scott2019) that either enhance or constrain practices; gendered ageing (im)mobilities (e.g. Büscher et al. Reference Büscher, Sheller and Tyfield2016); driving and driving cessation (e.g. Ang et al. Reference Ang, Oxley, Chen, Yap, Song and Lee2019); and the connections between mobility and well-being (e.g. Ziegler and Schwanen Reference Ziegler and Schwanen2011). While transport studies have contributed to understanding older adults’ behaviours, focusing on the relational dynamics of (im)mobilities enriches ongoing debates on experiences of ageing (Luoma-Halkola Reference Luoma-Halkola2025). Indeed, mobilities are embedded in social, cultural and spatial networks and power relations, which shape – and are shaped by – non-linear conditions of movement and stillness (Sheller Reference Sheller2021).

Mobilities-informed studies have examined older adults’ mobilities and how they interweave with wellbeing (among others: Borsellino et al. Reference Borsellino, Charles-Edwards, Bernard and Corcoran2024; Elsamani and Kajikawa Reference Elsamani and Kajikawa2024; Ziegler and Schwanen Reference Ziegler and Schwanen2011). Nonetheless, most studies focus on (im)mobilities without delving into the contradictory experiences that shape mobile practices together with ageing processes (Cuignet et al. Reference Cuignet, Perchoux, Caruso, Klein, Klein, Chaix, Kestens and Gerber2020; Darlington-Pollock and Peters Reference Darlington-Pollock and Peters2021; Mansvelt Reference Mansvelt, Adey, Bissell, Hannam, Merriman and Sheller2014; Pantelaki et al. Reference Pantelaki, Maggi and Crotti2021). Although this research gap has been acknowledged (Gatrell Reference Gatrell, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2017), both mobilities studies and critical social gerontology have yet to fully engage with the stratified relationalities that co-produce experiences of ‘being (im)mobile’ insofar as they are ‘ageing’ – and vice versa (Luoma-Halkola Reference Luoma-Halkola2025; Parviainen Reference Parviainen2021).

Mobilities studies provide a framework to complement critical gerontology by developing approaches to examine how mobilities shape lived experiences, material realities and affective geographies through ageing (Gatrell Reference Gatrell, Skinner, Andrews and Cutchin2017). In turn, critical gerontology deconstructs narratives surrounding ‘successful ageing’ by fostering reflections on (im)mobilities that emerge across lifecourses (Buffel and Phillipson Reference Buffel and Phillipson2024). It adopts flexible approaches to examining how older adults develop mobility capabilities and agency that transcend conventional notions of movement or stillness (Mansvelt Reference Mansvelt, Adey, Bissell, Hannam, Merriman and Sheller2014), thereby paving the way for strategies of integrated theory-making. Specifically, this disciplinary interaction should focus on problematizing perspectives that frame older adults’ (im)mobilities ‘simply’ as a consequence of ageing processes. Instead, mobilities should be understood as constitutive elements of ageing itself, co-producing variegated and even ‘unexpected’ conditions of being mobile (e.g. Luoma-Halkola and Häikiö Reference Luoma-Halkola and Häikiö2022). Recognizing this relationship as mutually productive means understanding the complex relationalities that unfold through (im)mobilities as experiences, practices and representations that play a fundamental role in processes of ageing and subject-making (Sheller Reference Sheller2021).

The novelty of this approach to older adults’ automobilities is twofold. First, a mobilities-informed perspective challenges the assumption that older adults’ (im)mobilities stem primarily from, and depend on, transportation (Sheller Reference Sheller2018). Instead, it argues that (im)mobilities emerge through socio-economic, political, environmental and cultural relationships that shape specific contexts – relations upon which transport systems themselves also rely (Adey Reference Adey2017). These relations involve infrastructures and transit means, but also one’s ‘mobility of the self’ (Ziegler and Schwanen Reference Ziegler and Schwanen2011), living environments, social networks and the interactions among these dimensions (Sheller Reference Sheller2018, Reference Sheller2021).

Second, while previous studies have explored how older adults remain ‘mobile’ after giving up driving (among others, Musselwhite and Scott Reference Musselwhite and Scott2019), they often reproduce what might be called an ‘automobility hierarchy’, where driving is central and other practices – for example passengering – are framed as ‘coping’ mechanisms. Developing frameworks to identify the factors and practices that enable non-driving older adults to ‘remain mobile’ certainly offers valuable insights. Yet such accounts remain partial in capturing the range of being-(im)mobile experiences embedded in the mutually constitutive and non-linear relationships between (im)mobilities and ageing. This article instead advances a fully relational and non-hierarchical understanding of automobility. This approach enables comprehensive analyses of practices, experiences and relationships mediated by – and constituted through – the car (Adey et al. Reference Adey, Bissell, McCormack and Merriman2012; Sheller Reference Sheller2004). It opens up the possibility of recognizing important experiences of being mobile, alongside the complex relationships they generate and express. These would otherwise remain obscured were automobilities reduced to transport alone, with driving as their normative expression.

Methodology

This article draws from INDEPENDENT AGE (I-AGE), an ongoing research project involving four Italian universities (Ferrara, Brescia, Salerno and Salento). The I-AGE project is supported by national research funding and the EU-financed National Recovery and Resilience Plan (PRIN-PNRR). The Research Unit at the University of Brescia (RU_UniBs) is conducting a qualitative study to investigate how the city’s strategies of urban governance influence the capabilities for urban ageing in place among older adults residing in Via Milano – a working-class and ethnically diverse yet gentrifying neighbourhood in Brescia.

As of January 2025, the RU_UniBs has completed a critical analysis of local and national documents orienting urban and mobility planning. It has been complemented by 14 interviews with managers of various municipal departments. A further 36 dialogical interviews (Lamendola Reference Lamendola2009) have been conducted with residents aged 60+ in the neighbourhood, integrated by participant observation of the neighbourhood’s life. Each participant took part in a single semi-structured interview exploring how daily practices unfold across multiple scales – home, building, block, neighbourhood, city and digital space – and how physical and/or digital (im)mobility enhanced or constrained their movement. Interviews encouraged storytelling by adopting ‘dialogical’ interviewing techniques (Lamendola Reference Lamendola2009).Footnote 2 As no sensitive or medical topics were directly addressed, only informed consent was required by RU_UniBs’s guidelines. Participants were anonymized throughout and pseudonyms are used in this article. All data and recordings were stored in compliance with the General Data Protection Regulation to ensure confidentiality. Interviews were conducted with attention to participants’ wellbeing and could be discontinued without consequence.

Participants were selected based on age (60+) and residence in the study area. Interviews, conducted by the author, lasted 50–70 minutes each and took place in participants’ homes, or at the offices of a social co-op involved in the research project. With participants’ consent, interviews were audio-recorded, transcribed and thematically coded.

Recruitment followed three main channels: (1) Congrega Apostolica – a Catholic organization providing subsidized housing in Porta Milano – supplied a list of residents who agreed to participate, plus I undertook (2) snowball sampling via diverse gatekeepers and (3) collaborations with local cooperatives. This allowed for a diverse sample in terms of class, migrant background, gender, age, health conditions and residence. Participants ranged from 60 to 92 years old. Rather than seeking statistical representativeness, we explored diverse practices of ageing in place through situated narratives, rooted in different experiences within a changing neighbourhood.

This article focuses on four interviews selected for their insights into the relationalities of ageing co-produced through practices of automobility. These interviews are intended to be neither representative nor exhaustive. Nonetheless, they foster critical reflections to inform novel connections between critical gerontology and mobilities studies (Joelsson et al. Reference Joelsson, Balkmar and Henriksson2025). This choice is grounded in the richness and complexity of the experiences shared by our interviewees. Other interviews could have been equally insightful: had other interviews been selected, different themes might have emerged, or the same ones approached through different experiences. Nonetheless, the central reflection of this article would have remained unchanged: that automobilities constitute complex relational fields where experiences, practices and conditions of being (im)mobile and ageing unfold as interwoven, non-linear and mutually constitutive. Automobilities also play a decisive role in shaping the interplay between the ‘mobile self’, the surrounding environment, social relationships and the multifaceted entanglements among these dimensions. What makes this approach meaningful is its focus on the everyday nature of those experiences (Grenier Reference Grenier2023; Manderscheid Reference Manderscheid2014a). This framework enhances situated understandings of the interplays between (im)mobile subjectivities alongside their experiences of ageing processes. Indeed, it focuses on conditions, practices and relations that co-produce (im)mobilities in daily life and across lifecourses (Phoenix and Bell Reference Phoenix and Bell2019). This approach is grounded in the situated ways in which ageing subjects navigate through and, consequently, produce their lived realities, senses of the self, affective geographies and relationalities of mobilities (Sheller Reference Sheller2021). The generalizability of the findings is very limited, as the interviews can be understood only when situated within the specific context of Brescia. Nonetheless, this article offers an original interpretation that enriches multi-disciplinary debates on older adults’ (im)mobilities, by moving beyond interpretations based on causal and unidirectional links between (im)mobilities and ageing processes, as well as under-problematized associations between older adults’ (im)mobilities and transportation (Sheller Reference Sheller2018).

The research field

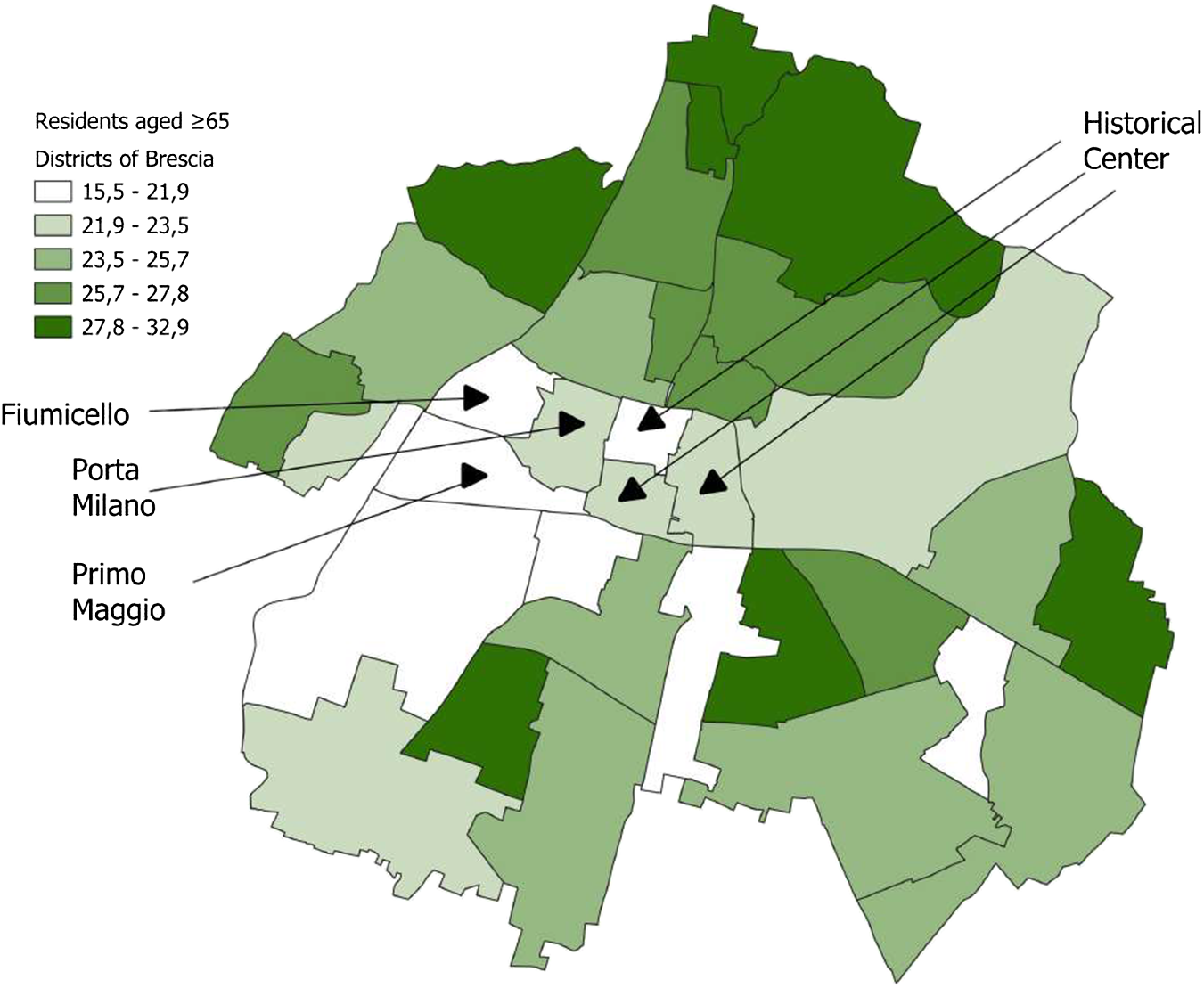

Brescia is a Northern Italian city with 200,000 residents. Once a major industrial hub, it has undergone significant de-industrialization. Currently, 24.7 per cent of its population is aged 65+, unevenly distributed across the city’s districts (Figure 1). About 20 per cent of residents are classified by the Municipality as ‘foreigners’, primarily from Eastern Europe, North Africa and South-East Asia. Municipal data indicate that the average age of ‘foreign’ residents (34yo) is significantly lower than that of Italian citizens (45), with nearly 80 per cent of ‘foreigners’ under the age of 49 (Colombo and Santagati Reference Colombo and Santagati2024). Data from the national Ministry of Transportation show that in 2018 – the most recent available – between 20,000 and 25,000 of the city’s 65,000 active driving licences were held by individuals aged 65+.Footnote 3

Figure 1. Percentage of residents aged 65 or older in the population of each neighbourhood. Author’s elaboration of municipal data.

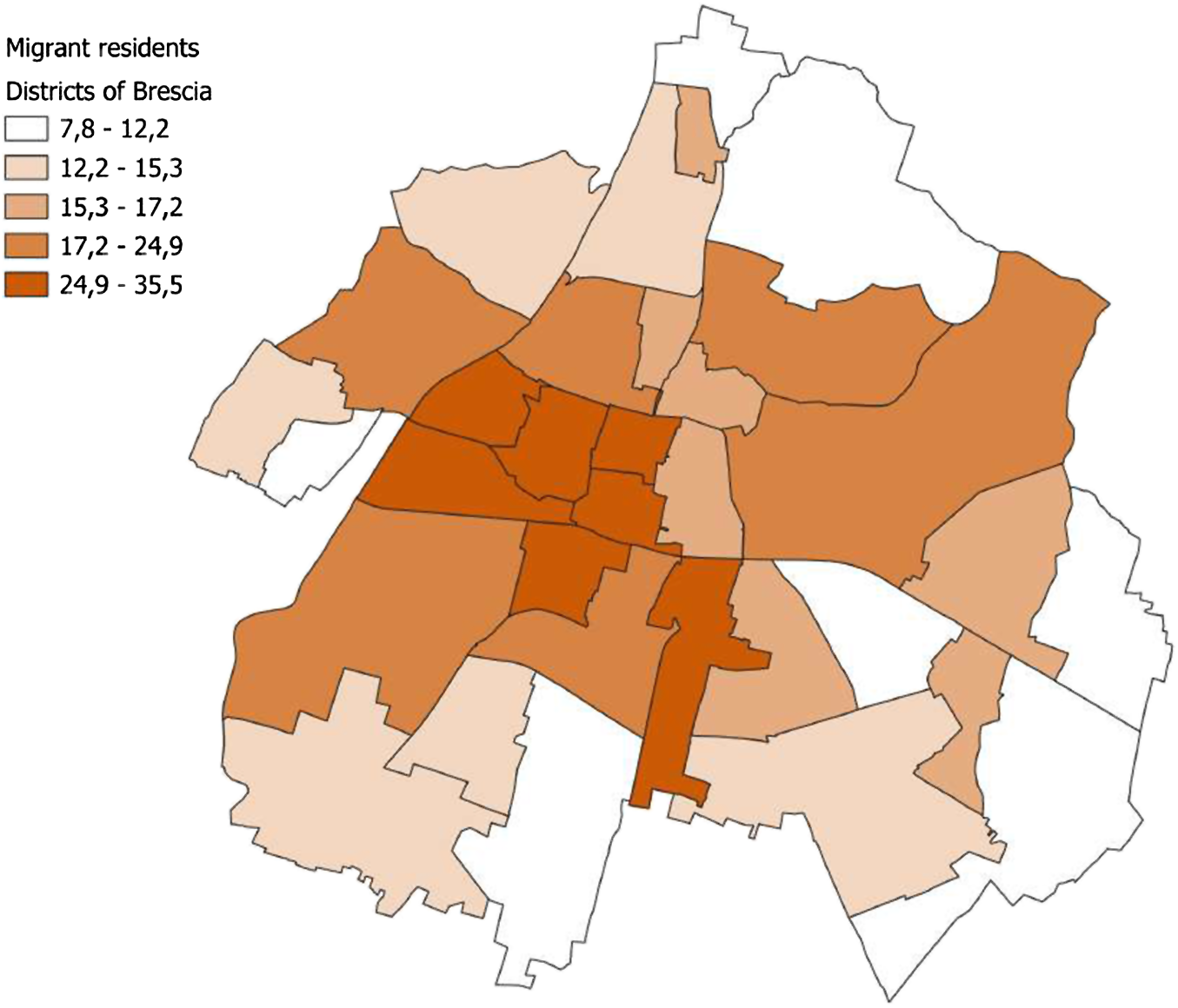

Via Milano is a long-standing working-class and ethnically diverse neighbourhood located immediately west of the historic centre. Since 2017 it has been targeted by a state-funded urban regeneration project (Alioni doi:10.1080/07352166.2025.2492704). The neighbourhood comprises the arterial road Via Milano and the districts of Porta Milano (north-east), Fiumicello (north-west) and Primo Maggio (south). Home to around 16,000 residents, the area has the city’s lowest proportions of residents aged 65+ (22 per cent). It also shows the highest share of residents without Italian citizenship (around 37 per cent) (Figure 2), with an average household income (€22,281 in 2023) below the city’s average. The regeneration project is exerting gentrifying pressures on those districts, complicating residents’ relationships with the neighbourhood’s built and symbolic environments (Alioni and Badiani Reference Alioni and Badiani2024).

Figure 2. Percentage of ‘foreign’ residents in the population of each neighbourhood. Author’s elaboration of municipal data.

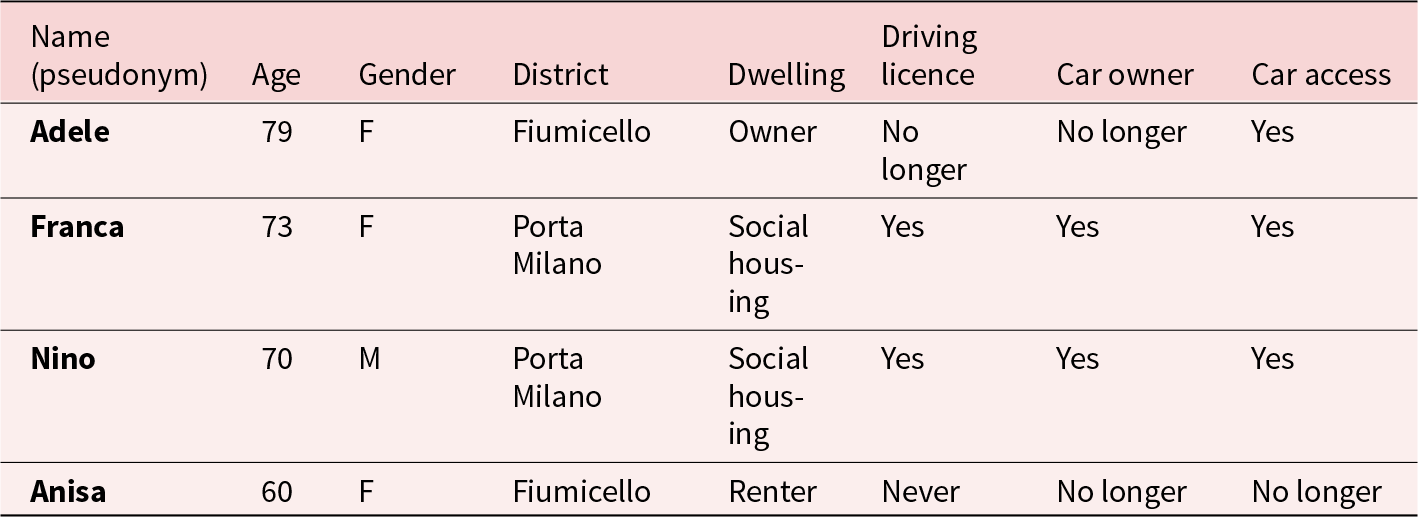

Among the 36 interviews conducted to date (January 2025), four were selected to explore participants’ automobilities (Table 1). In each case, a range of intersecting factors – such as class, gender, ethno-national belonging and (dis)abilities – complicate the intricate conditions of ‘ageing’ and ‘being (im)mobile’ as co-constructed through automobilities (Sheller Reference Sheller2021). This article does not provide an exhaustive explanation of how these conditions interact with (auto)mobilities (Sheller Reference Sheller2004) and ageing processes (Buffel and Phillipson Reference Buffel and Phillipson2024). Rather, it focuses on the relationalities that mutually configure older adults’ everyday automobilities, the experiences of ageing and the dynamic construction of both ‘ageing selves’ and ‘being mobile’.

Table 1. List of interviewees considered in the article

Relationalities of automobility

The results are organized around four cases that illustrate different configurations of ageing and automobility in Brescia. Drawing on narratives and reflections, each case highlights how older adults negotiate the challenges and possibilities of everyday (auto)mobility. Together, they capture the relational complexity of mobility practices and their intersections with ageing. This sets the stage for the following discussion, which situates our findings within wider debates in critical gerontology and mobilities studies.

Adele

Adele, 79, has spent her entire life in Fiumicello, where she was born, living with her sister (89) and brother (77). During the interview, Adele described the division of tasks that structures their family life:

I cook, my sister cleans up the house, and my brother drives us around whenever and wherever we need.

None of the siblings ever married or had children, forming a household bound by a lifetime of routines, practices and memories. Adele’s entire life has been deeply connected to the local Catholic parish, which evolved into a lifelong commitment. She has long been part of the group that supports the priest in managing the parish community centre – a role that shapes her daily life and sustains her ties to the community. For Adele, the parish is not just a place of worship but a vital space of belonging and service, deeply woven into the fabric of her identity.

In 2022, Adele experienced a severe loss of physical mobility that left her nearly unable to walk. In her interview, she described how she suddenly lost much of her ability to walk and stand. While she does not need a wheelchair, Adele relies on crutches and needs assistance for short trips or simple tasks requiring both hands – like moving pots from the stove. She also described how her family adapted their house by installing handles and supports in every room to help her navigate around independently, also moving Adele’s bedroom to make it easier to access.

While Adele used to drive frequently, her loss of physical mobility forced her to stop:

At my age, in my condition, why would I bother with a new car? [I thought about buying] one of those with special controls on the wheel … But with all the traffic out there, and for the few times I might really need to drive by myself … But buying a new type of car and learning how to drive again? Now? It’s out of the question.

Although she considered buying a car adapted for people with leg disabilities, Adele eventually accepted that she was ‘too old to drive’, acknowledging that driving no longer held the same essential role in her life. She made the difficult decision to stop driving altogether and sold her car. Yet, her sudden physical disability and the end of her driving did not coincide with a complete abandoning of active automobility:

I used to do groceries by myself, but now I no longer can take care of it …. [However], we have a dog that always causes chaos when left home alone. So now, it often happens that I go with my brother to do grocery shopping, and while he is in the supermarket, I stay in the parking lot, sitting in the car with the dog.

The moral economy that had shaped Adele’s relationships with her siblings allowed them to develop new ways of sharing family and community life. This not only highlights the relative significance of the (assumed) ‘absolute independence’ largely associated with driving but also challenges the (assumed) passivity often attributed to passengering (Adey et al. Reference Adey, Bissell, McCormack and Merriman2012). Adele’s transition into an active passenger role coincided with her recognition that she was now too old to (re)learn driving in a completely different way. Being a passenger has reshaped the specific tasks she performs to fulfil her family roles amid worsening health conditions – without reducing her to conditions of immobility or passivity.

Although becoming a passenger required a reorganization of family duties, her relationship with this condition reflects continuity between her (albeit altered) practices of automobility and her engagement with the city and Catholic community. She shared that driving had always been more than a means of transportation – it was closely tied to her sense of personal safety while navigating the neighbourhood:

Since I started getting old, around the age of 50, I’ve never walked in the neighbourhood again – it happened only a few times and only with other people. I’ve always driven since then because I’ve always been afraid that someone could rob me. Getting into the car was a way for me to feel safer, even if my house is less than 10 minutes’ walking away from the parish.

For Adele, driving was a foundational medium between her (ageing) sense of self and her sense of belonging to the Catholic community. It helped her navigate feelings of ‘frailty’ and ‘vulnerability’ associated with ageing through the perceived ‘dangers’ of her neighbourhood. While this role of driving as a critical infrastructure for social participation has been taken over by her brother’s automobility and her role as a passenger, Adele frames this shift as active involvement in their household’s moral economy. For example, considering herself ‘digitally proficient’, Adele handles tasks such as downloading and printing her siblings’ medical prescriptions sent via email by their family doctor, while her brother drives her to the parish every day so that she can continue helping to manage the community centre. In this sense, Adele and her brother act as each other’s infrastructure: her brother makes her mobile in the physical space through his driving, while she makes him mobile in the digital space. Moreover, for Adele, passengering becomes an opportunity to share spiritual moments with him:

He drives me [to the parish] every day at 2 and comes back at 4, every single day. If I feel good enough, I also come here on Sundays for Mass, and sometimes my brother joins too. I really like it when that happens.

Interpreting Adele’s practices and ageing processes through a relational understanding of automobilities illustrates how driving cessation, passengering, the loss of ‘autonomous’ (auto)mobility and familial relationships intersect to shape her identity, roles and daily dynamics through later life. Adele’s transition from driver to passenger reflects a redefinition of her agency within her household’s moral economy, allowing her to fulfil her responsibilities and maintain her connection to the Catholic community. While her current reliance on her brother underscores specific limitations imposed by ageing and disability, it highlights how automobility remains integral to community participation and a crucial condition of being mobile, albeit through non-normative practices. Indeed, despite her changed circumstances, it is the reciprocal support within her family and her continued engagement in the community that illustrate her capacity to reconfigure personal identity and agency while navigating ageing, physical disability, driving cessation and redefined conditions of being mobile.

Franca

Aged 73, Franca has been living since 2011 in a Congrega’s apartment. Although she ‘fell in love twice in [her] life’, she has never married and has no children. While her housing arrangement protects her from the economic challenges brought on by her low social pension, Franca struggles to establish reliable connections with the surrounding neighbourhood.

Although she has limited contact with family members, Franca maintains long-standing friendships. These relationships are characterized by daily interactions, exchanges of favours and emotional support. Franca owns and drives an old car, but her practices of automobility are shaped by several factors, including her self-perceptions of ageing, her worsening health, economic constraints and the significance she attributes to different relationships.

First, various practices of automobility have become Franca’s only reliable source of movement that also mitigates her fears about the neighbourhood in specific moments of the day. These fears are explicitly tied to her perceptions of ageing and how certain mobility practices, like walking or biking, leave her more vulnerable to threats:

I used to bike, but now I am scared of falling. And I don’t like walking in the neighbourhood, because ten years ago I would have been able to react to threats, I could have kicked a robber, or hit them with my bag. But now I am 73, I am old, I would no longer be able to react quickly, so I do not walk around in the evening or early in the morning.

Driving allows Franca to manage essential tasks such as grocery shopping. She explained that, ‘as any other elderly should do’, having access to a car enables her to stock up on a substantial number of groceries. This helps her avoid situations where she might run out of essential items while not feeling well enough to do her groceries. Automobility serves as an ‘infrastructure of prevention’, allowing her to anticipate and mitigate the effects of sudden health setbacks that increasingly compromise her ability to meet her needs. However, this need for prevention is relatively recent and directly linked to her perception of herself as an ageing subject – one who is becoming more vulnerable to external risks, as well as to the ‘unpredictable paths that life might take’, as she put it.

Driving enables Franca to move beyond the economic constraints of her immediate surroundings. In the interview, she harshly criticized the high prices of the small shops within walking distance of her apartment. For this reason, she relies on driving to reach the cheaper supermarkets located around 1–1.5 km away. Unwilling to take buses – owing to fears about ‘the kinds of people you meet while travelling in the neighbourhood’ – she says that driving remains her only reliable source of mobility, enabling her to manage essential tasks beyond both financial and perceived safety constraints. Franca’s reliance on automobility brings into focus her worsening health, which increasingly shapes the rhythms and intensities of the practices and relations she has developed through automobilities over the years. Furthermore, she now suffers from leg pain and serious vision problems. Although high-prescription glasses and using eye drops offers some relief, she can only drive in the morning and avoids unfamiliar routes, which she finds increasingly daunting. This also aligns with her desire to spend time at home during the afternoon and the evening, as

managing basic tasks has now become really difficult, as I get tired soon and during the afternoons I just need to rest from the fatigue I accumulate in the mornings.

While automobility allows Franca to physically and symbolically overcome various economic constraints, the combination of worsening health and her low socio-economic status prevents her from consistently relying on driving to move beyond her immediate surroundings. She voiced frustration about the high parking fees near major health-care facilities, their limited availability and the distance of free or cheaper parking spaces. As Franca put it, she cannot afford to view automobility as a reliable resource for all her needs. Instead, it can become a barrier, hindering her access to essential services that support her health and wellbeing. Although she values ‘independence’ and ‘autonomy’ as core elements of her ageing self, for specific tasks she ‘accepts’ being ‘demoted’ to the role of passenger. This also requires her to adapt to others’ schedules, with only limited flexibility to adjust them to her own needs:

Since parking [next to the hospital] is expensive, and since you have no idea what kind of people you can find in the neighbourhood early in the morning, I usually ask my friends to give me a ride before they go to work. Even though I arrive there much earlier than expected, I end up sitting at the bar in the hospital, drinking my coffee, eating my pastry, and waiting for my turn. Then, somehow, I manage to get back home by myself, but walking around the neighbourhood at 11am is not the same as doing it at 7.

Ultimately, the practices and constraints of automobility described by Franca reveal that automobility is an active effort that reflects her willingness to nurture specific relationships (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Sheller and Wind2015), as well as the ways she negotiates her own and others’ ageing processes in light of the expectations of mutual aid and solidarity, which she believes ‘should be at the core of meaningful relationships’. Her family and closest friends live in two different towns, both about 10–12 km from Brescia. While Franca often drives to visit her friends – describing it as a ‘real pleasure’ and a way to ‘feel connected to each other’ – she also admitted that she ‘[does not have] enough energy’ to drive to her brothers’. Indeed, as she argued,

I am getting old and tired; you cannot expect me to take care of you. I need to think about myself first, and my problems. My brothers have children, and I tell you, it’s really different to get old with or without children. They need to stop asking me favours. With my friends it’s different, they are alone too, but if you have children you should not ask me anything!

Franca’s experience highlights the complex interplay between ageing, automobility, economic status and relational dynamics. As her health declines, driving becomes essential not only for managing daily tasks but also for coping with the sense of insecurity stemming from the perceived weakening of her body. Moreover, her reliance on the car reflects the intricate ways in which ageing shapes her mobility practices – enabling her to navigate economic constraints and various perceived risks. However, increasing financial and physical limitations related to parking and health conditions reveal that automobility, while a source of autonomy, is also a constrained and at times burdensome resource, one that makes manifest her low economic status and related challenges. Indeed, it is precisely the ambivalence of her relationship with driving that shapes both her ‘(im)mobile’ and ‘ageing’ selves, in the context of her precarious economic and health conditions. Furthermore, her evolving relationships suggest that ageing affects not only how one navigates physical spaces but also how roles and expectations are negotiated – with support becoming more selective and grounded in reciprocity rather than familial obligation.

Nino

Nino, 70, was born in Bari (Southern Italy) but has lived in Brescia since the early 1970s. Once a successful entrepreneur, Nino faced severe economic challenges in recent years, losing much of his wealth. After he became divorced in the 1990s, his daughters cut ties with him. In the early 2000s, Nino met his second wife and they married. However, in 2016 she began to suffer from serious health conditions that eventually left her bedridden and in need of frequent hospital care. The couple lived in a fourth-floor apartment in an upper-class neighbourhood, in a building without a lift. As her condition worsened and Nino’s financial situation declined further, caring for her became unmanageable and the apartment unaffordable. In 2020, shortly before the Covid-19 pandemic, the couple applied for a subsidized municipal unit, in coordination with Congrega. Given the couple’s severe circumstances, they were promptly housed in a Congrega apartment equipped with a lift spacious enough to fit a hospital bed. However, his wife’s health deteriorated further and she passed away in 2022. Nino still lives alone in the same apartment.

In recent years, Nino has been dealing with various health issues that intermittently limit his ability to take care of himself, particularly affecting walking and driving. Although he describes himself as someone ‘who’s always on the move’, he acknowledges that in recent years he has had to significantly scale back his activities. For example:

I used to go to Apulia every year, but now I’ve stopped. I have a pacemaker now, and two years ago I hurt my foot on the beach by stepping on a rock. The wound got infected, and I almost lost it. I need to stay calm now.

Nino has also had to adapt to new rhythms of life after losing most of his vision, which has posed several challenges – especially while driving. His vision impairment has also resulted in several falls, which frightened him, making him reluctant to walk long distances:

I no longer drive at night because of my vision problems, and because I felt a few times now I’m scared to walk around during daylight too. Actually, I’ve discovered that I enjoy staying at home just as much as going out.

Although Nino has managed to make some friends by regularly visiting a few cafés near his home, he does not have strong ties with the neighbourhood, having spent most of his life in other parts of the city. Most of his close ties are still in another district, and he regularly drives there to visit them. However, his worsening vision increasingly forces him to contemplate a future in which he may no longer be able to drive – a prospect closely linked, as he put it, to his fear of ‘getting old’ and of the ‘coercive (im)mobilities’ he has witnessed in the lives of others:

I still don’t need to use public transit, I don’t even know where those lines go, but maybe one day I will, but, for example, there’s this old lady living in my building. Her daughters come every morning, take her to a social centre in the neighbourhood and bring her back in the evening. For me, that would feel like going to jail. If I were to get old like that, I’d rather take a shot of insulin and say goodnight to everybody.

Nino’s perceptions of his own ‘mobile’ ageing are closely mediated by his ability to drive, which enables him to consider himself as an autonomous subject and to maintain meaningful relationships – though these are increasingly threatened by his deteriorating health. However, the relationship between autonomy, his mobile self, ageing and driving is complicated by a deep sense of loneliness, which becomes acute when he is unable to drive:

It is what it is, worst case scenario, I jump in a cab, but it’s the only thing I can do when I cannot drive if there’s nobody ready to help me.

Although Nino says he has friends who could drive him to the hospital when undergoing treatments that affect his vision, he often finds himself forced to take a cab – an option he can barely afford (€30 per round-trip). This condition of ‘forced’ reliance on cabs starkly contrasts with his self-image as an ‘always-on-the-move’ subject and his frequent references to a wide network of friends and relatives. The tension lies not in movement per se but in the resources he must mobilize to actualize his potential for movement (Kaufmann Reference Kaufmann2017). This situation highlights his growing awareness of the challenges of ageing in an existential context marked by the absence of close familial ties and his deep dependence on driving to mitigate the economic burden of cabbing. This reliance is further complicated by his worsening vision, which has almost entirely impaired his ability to use his smartphone and laptop to access digital services – despite his self-perception as ‘digitally proficient’. As a result, Nino increasingly depends on driving not only for medical treatments but also to collect the results of tests, which he must undergo regularly. Nino’s precarious automobility thus mirrors – and reinforces – the broader existential precarity in which he finds himself, shaped by deteriorating health, evolving perceptions of independence and ageing processes compounded by loneliness. While driving remains central in his sense of autonomy, it represents a fragile equilibrium underpinning his day-to-day existence. This balance is now under constant threat as his deteriorating health is undermining both his mobility and his self-perception as an ‘always-on-the-move’, independent subject. For Nino, driving is more than a practical necessity – it is a lifeline for maintaining relationships, accessing essential health care and managing everyday life. Losing this ability would limit his mobility by affecting his identity and his ability to navigate the world autonomously. His reliance on driving creates a paradox: it sustains his perceived autonomy, yet places him in an increasingly precarious position where any further decline in health could mean a loss of ‘control’ over his life. Nino’s precarious automobility becomes emblematic of his broader existential struggles. It is both a reflection of his current vulnerabilities and a contributing factor to his ongoing precarity – underscoring the complex interplay between his being (im)mobile, health, independence and ageing. Should he lose the ability to drive, the delicate balance that sustains his identity and autonomy could collapse, leaving him even more isolated and dependent on external systems that he currently sees as inadequate.

Anisa

Aged 60, Anisa lives on Via Milano. Originally from Morocco, she moved to Italy with her husband in 1999. The couple, who had no children, lived in various cities – including Mantua, where her brother resides – relocating frequently owing to her husband’s work. In 2023, Anisa became an Italian citizen. Then in 2022, after enduring over a year of severe illness, her husband passed away, leaving Anisa to navigate life alone.

In 2014 they bought an apartment on the third floor of a building without a lift, but financial difficulties eventually forced them to sell it before repaying the mortgage. Anisa now rents the same apartment, covering the cost with unemployment benefits. She never obtained a driver’s licence – her husband opposed the idea, believing that it was inappropriate for a married woman to drive.

Anisa tells me, ‘I wanted to learn how to drive, but my husband wouldn’t allow it. He was the one who drove, and he didn’t think it was right for his wife to drive.

In deference to him, she never questioned it. Instead, Anisa became adept at navigating the city’s bus network, even while working night and early morning shifts as a full-time care-giver.

Over recent years, worsening heart and leg issues have made walking increasingly difficult. During her interview, Anisa spoke of the profound loneliness of widowhood – intensified by the loss of access to automobility. This loss, she explained, sharpened the emotional and sensory experience of her husband’s absence, deepening her grief:

It has become very hard for me to do even daily life things [without her husband’s support] …. I can’t even go back to work because I’ve lost my patience and courage – I can’t focus. I’m always thinking about him. I wasn’t, and I’m still not, ready [to face life without him].

Exploring Anisa’s intricate relationship with automobility reveals how her ‘mobile self’ and her self-perceptions – as a wife, a widow and an ageing subject – are deeply interconnected. For Anisa, being a wife meant being a passenger: not a position of mere dependence or passivity but one of active participation in the moral and functional economy of the household. In this light, widowhood signifies a double loss – not only of her husband but of automobility as well – a practical and symbolic extension of their marital life. Anisa must now rely on her physical capacity, hindered by worsening health, and her familiarity with the public bus system. Her daily routines have become fragmented, restructured into smaller, more manageable tasks that reflect her declining health and the absence of a car (Sheller Reference Sheller2004): ‘I need to go frequently to the supermarket because I can only carry a few things each time. I can’t walk or take the bus if my trolley is too heavy’.

Anisa’s relationship with her brother offers a different experience of being a passenger. When he visits Brescia for work and stays overnight, he drives her to the supermarket and helps carry groceries upstairs – it is a relation of mutual aid rooted in reciprocity. Yet, when he opts to stay in a hotel with his co-workers, this support disappears. This shift underscores how Anisa’s identity as a passenger has evolved through widowhood (Adey et al. Reference Adey, Bissell, McCormack and Merriman2012). While she values her brother’s help and their bond, her passengering is now conditional and intermittent – no longer the consistent, spousal form of passengering she once shared with her driving husband.

These dynamics underscore Anisa’s evolving sense of self as she navigates widowhood and ageing, shaped by shifting relationships to automobility and the growing constraints of her health. The death of her husband coincided with the loss of reliable, steady transportation, further complicating her ability to manage everyday tasks. Her widowhood thus brought with it a self-reflexive reckoning with her past identity as a ‘passengering wife’ – a role that had come to define her experience of automobility. In losing both the car and her husband, Anisa confronts not only the practical absence of support but also the emotional rupture of her marital relationship. In retrospect, her understanding of wifehood had been intimately tied to the act of being a passenger, a connection that continues to shape her current sense of self. Yet, within the entangled realities of carlessness, grief and physical pain, there also emerges a space for reimagining her identity, routines and everyday life – beyond the passive echoes of widowhood as a fixed and inevitable extension of her former life as a wife: ‘Now that I got old, it is time for me to get a driving licence and drive my own car!’.

Smiling with visible pride during the interview, she shared her strong desire to get a driver’s licence and drive – a decision she describes as a practical response to her advancing age, but one that also signals a profound shift. No longer content to be a wife-passenger and mostly carless-widow, she now seeks to become – literally and symbolically – a person who drives, fully able to take care of herself as she navigates the challenges of ageing. This transformation reflects her determination to emancipate herself from the constraints of being a forced passenger and to expand her autonomy, without relying on others’ automobilities and beyond her physical limitations. In embracing this ‘potential’ automobility, Anisa is reimagining her identity and her future, transcending the psychological, physical and political confines of both wifehood and widowhood, and reclaiming her agency as a person who drives her life, even as she acknowledges the unprecedented challenges she must now face alone.

Yet Anisa’s desire to escape the role of ‘carless passenger’ is deeply entwined with her experiences of wifehood and widowhood. For her, driving represents a potential site of negotiation, shaped by her evolving subjectivity, her sense of the world, her needs and her declining health, which she associates with ageing, remarking that she is ‘finally getting old’. Simultaneously, her actions reveal a lasting attachment to her identities as both a wife and a widow. For example, after her husband died, she replaced their king-sized bed with a twin, explaining: ‘The only person I could ever want to share a bed with is no longer in this world’.

This paradox vividly highlights the complex relationships between Anisa’s evolving ‘sense of self’, her emotional and physical suffering, automobilities and the layered experiences that shape her identity as a wife, widow and person who now urgently needs to drive because – as she puts it – she is ‘getting old’.

Anisa’s experiences reveal the deep interconnections between her changing mobility practices, her health challenges and her evolving sense of self as she moves from wife to widow. Her identity as a passenger – once shaped by her role as a wife – has become fragmented, now dependent on her brother’s intermittent assistance, which lacks the reliability that her husband once provided. Her decision to pursue a driver’s licence represents a significant shift. More than a practical response to her declining health, it is a symbolic and active reconfiguration of her being mobile and her ageing identity in this peculiar phase of her life. This shift – from passenger to potential driver – expresses her desire to transcend the limitations imposed by widowhood and physical condition. In seeking to drive, Anisa is not only addressing material needs but also asserting her agency by reshaping her life beyond the constraints of practices related to specific understandings of her relational roles that have now become obstacles to her wellbeing.

Discussion: relational understandings of automobilities and ageing

A deep exploration of the complex relationalities embedded in, co-produced by and emerging through automobilities challenges straightforward connections between driving and conditions usually associated with ageing and (im)mobility (Schwanen et al. Reference Schwanen, Banister and Bowling2012). These often under-problematized links reinforce dichotomous understandings of (im)mobility that are observable on the ground (Salazar Reference Salazar2021; Stjernborg et al. Reference Stjernborg, Wretstrand and Tesfahuney2015). Common interpretations still equate older adults’ ability to drive with independence and ‘active’ ageing (Perez et al. Reference Perez, Rashidi, Boni, Hyun, Farrokhi and Park2024), while cessation and car-lessness are framed as immobility, dependence and passivity (Waitt Reference Waitt2022). Practices related to automobility but distinct from driving are normatively interpreted as ‘coping mechanisms’. However, the analysis here highlights active practices of passengering (Adele and Anisa; Adey et al. Reference Adey, Bissell, McCormack and Merriman2012), parking (Franca; Merriman Reference Merriman2016) and cabbing (Nino; Adey Reference Adey2017), together with experiences of ageing co-produced by relational automobilities. The central concern explored here lies in the interplay between conditions of being (im)mobile and ageing processes. As illustrated by the participants’ experiences, this interplay involves both everyday practices and relational configurations that co-produce their conditions of being mobile through ageing. These findings align with research on the relationality of mobilities (e.g. Sheller Reference Sheller2021), but extend it by showing how older adults negotiate these dynamics in Brescia. My analysis suggests that mutually constitutive relationships between ageing and being (im)mobile cannot be reduced to transport behaviours alone, but must be understood as processes embedded in broader relations, interactions and urban conditions (Holdsworth Reference Holdsworth2013; Manderscheid Reference Manderscheid2014a; Piatkowski and Marshall Reference Piatkowski and Marshall2023). By grounding the analysis in detailed narratives, the study contrasts with research that treats driving and driving cessation as universal markers of autonomy or dependence (e.g. Musselwhite and Scott Reference Musselwhite and Scott2019), revealing instead how these categories are situationally and continually redefined through daily practices that extend beyond automobility in itself. In doing so, this article provides an empirical counterpoint to accounts that focus narrowly on transport behaviours and interpret mobility transformations as consequences of ageing, demonstrating instead how socio-material conditions and diverse relationalities actively shape the lived interplay of ageing and (im)mobility. What emerges from this analysis is thus a stratified understanding of both the relationalities of automobility as well as of automobilities as relationalities.

Specific automobilities often relegated to ‘dependent’ practices by the ‘rules’ of automobility (Sheller and Urry Reference Sheller and Urry2000) emerge as active experiences of ageing. These contradictions become visible through our participants’ narratives: Adele’s mobility actively derived from relational ties; Franca’s and Nino’s daily practices complicated normative links between autonomy and driving; Anisa’s experiences challenged assumptions that carlessness equals inexorable lack of agency. Acknowledging such multiple mobilities challenges normative ideals of ‘good’ ageing (Finlay et al. Reference Finlay, Gaugler and Kane2020).

The analysis here considered the ‘affective economies and emotional geographies of automobility’ (Sheller Reference Sheller2004, 223), shaped by the flows, circulations and intensities of emotions shared among people, objects and places. In car-centred societies, automobilities not only structure interactions within physical and social spaces (Urry Reference Urry2004) but also become mediums through which older adults co-create relations, emotional geographies (Sheller and Urry Reference Sheller and Urry2000), selves (Ziegler and Schwanen Reference Ziegler and Schwanen2011) and ways of inhabiting urban life (Sheller Reference Sheller2004). For example, Adele’s changing automobility redefined her role in her family’s moral economy; Franca reconfigured meaningful relationships and made evident her low socio-economic status; Nino’s declining driving abilities reshaped his self-perceptions about autonomy, loneliness and being on the move; Anisa’s conceptualizations of wifehood and widowhood informed how her ageing and (im)mobilities unfolded. Thus, our participants experience automobilities as extensions of themselves, and also as fields in which multiple dimensions of their lives – including their living environments, sense of ‘ageing selves’, conditions of being (im)mobile, meaningful relationships, personal roles and spatial trajectories – are constituted, sustained and negotiated (Adey Reference Adey2017).

A final consideration is that car-centric environments can be seen as socio-technical systems pushing urbanites into conditions of ‘forced flexibility’ (Manderscheid Reference Manderscheid2014b; Sheller and Urry Reference Sheller and Urry2000; Urry Reference Urry2004). Yet our interviews show not only adaptations to car-related constraints but also ‘unexpected’ relationalities and conditions of being (im)mobile emerging from multiple automobilities developed by subjectivities usually confined at the margins of ‘kinetic hierarchies’ (Mansvelt Reference Mansvelt, Adey, Bissell, Hannam, Merriman and Sheller2014). Therefore, automobilities emerged not as individualized behaviours but as relational fields revealing complex interconnections between ageing and (im)mobilities. Exploring these dimensions is important because it unsettles approaches that equate driving with autonomy and its cessation with passivity, calling instead for a broader understanding of the relational and situated ways in which older adults negotiate (im)mobility and ageing through their daily experiences.

Conclusions

This article has examined the relational systems embedded in older adults’ automobilities in Brescia, drawing on selected narratives. By situating the analysis in this context, it shows how social ties, socio-economic circumstances, self-perceptions and infrastructural arrangements intertwine ageing processes with complex conditions of being (im)mobile – a dimension often overlooked in the international literature (Mansvelt Reference Mansvelt, Adey, Bissell, Hannam, Merriman and Sheller2014). While much research assumes a linear relationship between driving and autonomy, the findings here reveal more nuanced and articulated experiences of (im)mobility, in which agency and dependency are relationally and situationally negotiated in everyday life. The study demonstrates the importance of examining older adults’ automobilities as relational and socio-material processes that shape – and are shaped by – the ageing process. The concept of relational automobilities highlights how (auto)mobilities are embedded within complex relationships, making them central to understanding older adults’ experiences of (im)mobilities and ageing. This mobilities-informed perspective shows that diverse conditions of being (im)mobile are crucial to how older adults ‘navigate’ urban life and their ageing selves. Considering how mobility practices shape the experiences of ageing provides a more nuanced account of their dynamic and mutually constitutive relationships. The analysis reveals that relational automobility is intertwined with the affective economies and materialities of everyday life: reliance on cars both reflects and reinforces the multifaceted interdependencies that characterize ageing. These practices expose vulnerabilities but simultaneously highlight older adults’ active capabilities to interpret challenges posed by health issues, economic constraints and urban life.

Bridging critical gerontology and mobilities studies, this article rethinks how ageing is co-constituted through everyday mobility practices and their relational entanglements. The narratives presented here destabilize binaries such as active versus passive ageing and independence versus dependence, revealing instead how older adults construct meaningful lives through ambivalent and evolving conditions of being (im)mobile. By engaging with older adults’ lived realities, this study foregrounds the moral economies, affective attachments and socio-material experiences through which ageing is experienced and reconfigured through mobilities. It contributes to critical gerontology’s broader aim of decentring individualized models of ageing by demonstrating ageing as a continuously negotiated, situated and multi-dimensional process. In doing so, the article offers new tools for conceptualizing the relationship between ageing and mobilities beyond simplistic links between practices and (supposedly corresponding) conditions – such as activity versus passivity, or autonomy versus dependency. This work invites engagement with emerging and non-linear conditions of being (im)mobile as generative terrains through which ageing unfolds. By reframing how ageing and (im)mobility are interpreted, the study advances an agenda that brings mobilities studies and critical gerontology into promising dialogue. While it has no direct policy implications, the study situates automobilities within broader relational contexts, suggesting new ways of observing older adults’ (im)mobilities and their implications for urban settings – particularly where political initiatives encourage residents to give up their cars in favour of sustainable transportation.

The study is necessarily limited by the small sample size and its location in a single city. Rather than offering generalizable claims, the findings should be read as situated insights into the relational dynamics of ageing and (im)mobility, aiming to advance a critical understanding of how older adults’ everyday automobilities co-constitute and are co-constituted by ageing processes.

Acknowledgements

I would like to thank Professor Barbara Badiani (University of Brescia) and Dr Richard Lee Peragine (University of Ferrara) for their valuable comments on the original version of this article. I would also like to thank Professor Maria Giulia Bernardini and Professor Orsetta Giolo (University of Ferrara) for the stimulating conversations on the themes of this research. I am grateful, too, to the two anonymous reviewers and the editors for their insightful suggestions. Finally, my sincere thanks go to all of the research participants.

Financial support

We acknowledge financial support under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan (NRRP), Mission 4, Component 2, Investment 1.1, Call for Tender No. 1409 published 14 September 2022 by the Italian Ministry of University and Research (MUR), funded by the European Union – NextGenerationEU – with the project title The right to independent living as a new frontier of justice: older people, urban spaces and the law – P20228MERB – CUP D53D23022220001 – Grant Assignment Decree No. 1375 adopted 1 September 2023 by the MUR.

Competing interests

The author(s) report that there is no competing interest.

Ethical standards

Ethical approval was not required for submission of this article.