Introduction

Historical trauma is never merely a relic of the past. Across diverse societies, collective memories of violence, war, repression, and colonial domination continue to shape how people interpret the present and imagine the future of their nation. A growing body of research has documented the enduring legacies of historical trauma, particularly political violence, in shaping contemporary political attitudes. For instance, xenophobic sentiments and support for radical right-wing parties in Germany are disproportionately concentrated around former Nazi concentration camps (Homola et al. Reference Homola, Pereira and Tavits2020). Studies of colonialism have shown that its institutional imprint continues to affect macro-level development outcomes (Banerjee and Iyer Reference Banerjee and Iyer2005; Dell Reference Dell2010; Nunn Reference Nunn2008; Dell and Olken Reference Dell and Olken2020). At the micro level, the consequences of violence extend to political norms, beliefs, and behaviors transmitted across generations (Nunn and Wantchekon Reference Nunn and Wantchekon2011; Acharya et al. Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018; Lupu and Peisakhin Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017; Charnysh and Peisakhin Reference Charnysh and Peisakhin2022; Rozenas et al. Reference Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov2017; Wayne and Zhukov Reference Wayne and Zhukov2022). Yet in everyday life, these memories often lie dormant. Collective trauma is embedded in national consciousness but remains latent, surfacing only when triggered by external cues or symbolic narratives (Fouka and Voth Reference Fouka and Voth2023). This latent quality raises a question: when and how do reminders of past violence shape contemporary political attitudes?

This study investigates how reminders of past political violence shape emotional reactions and political attitudes among the broader public. Rather than focusing solely on those directly affected by historical violence, this paper examines the broader societal impact of victimhood narratives, explaining how collective memory, once activated, can elicit emotional responses that influence attitudes toward the nation, its boundaries, and its leadership. Drawing on an original survey experiment, the study assesses the immediate effects of exposure to symbolic reminders of past injustice, with a particular focus on how they trigger discrete emotions and shift political preferences.

The analysis advances two main arguments. First, historical memories operate at both factual and affective levels. They serve not only as repositories of information but also as emotional archives, blending objective recollections of violence with subjective feelings rooted in group identity. Thus, historical victimhood cues elicit distinct emotional responses, such as anger and fear. Second, the emotional responses these memories evoke play a critical role in shaping downstream political attitudes. Anger, in particular, consistently predicts stronger expressions of national attachment and hardline stance in response to victimhood narratives.

Empirical findings support these arguments. Exposure to victimhood narratives intensifies emotional responses, especially anger and fear. Among these, anger, but not fear, is consistently associated with increased national pride, support for stronger political leadership, and endorsement of protective policies such as trade barriers. By contrast, detailed factual descriptions of past atrocities do not significantly shift political attitudes, underscoring the role of emotional resonance in shaping public opinion. These results suggest that collective memories, once emotionally activated, have a durable impact on how individuals relate to collective identity and policy preferences. By presenting the divergent effects of anger and fear, this study advances our understanding of how affect conditions the legacy of historical trauma.

This study contributes to the growing literature on the political consequences of historical trauma by foregrounding the emotional mechanisms through which collective memories shape public consciousness and political preferences. Although collective memory is often buried in complexity and ingrained in everyday consciousness, it can be reactivated through symbolic narratives that evoke strong emotional responses. This process helps explain how trauma becomes embedded in political culture, shaping not only private memory but public opinion. By exploring the persistence and activation of collective victimhood, the study highlights how carefully curated narratives can foster a sense of shared grievance and mobilize the public. It thus carries an implication for the study of the rise of populist and nationalist sentiments in both democratic and authoritarian contexts (Norris and Inglehart Reference Norris and Inglehart2019).

Furthermore, this paper refines existing insights in two key ways. First, it shows that the political effects of historical memory depend on the specific emotions it elicits. Although both are negative emotions, anger and fear lead to divergent outcomes: anger is associated with both national pride and hawkish preferences, while fear has no comparable effects. This emotional differentiation offers a more nuanced perspective than approaches that treat trauma of grievance as uniform drivers of political behavior. Second, by focusing on South Korea, a context in which state institutions have actively shaped and disseminated victimhood narratives, the study demonstrates how historically salient narratives influence emotional responses and political engagement. This contributes to broader debates on memory politics in post-authoritarian societies, where not only grassroots memory transmission but also state-led commemoration and education play a central role (Fouka and Voth Reference Fouka and Voth2023; Wayne and Zhukov Reference Wayne and Zhukov2022). The findings clarify when and how historical trauma becomes politically consequential, offering a mechanism-based account of how collective memory, emotion, and political behavior are linked.

Historical traces of the trauma and contemporary political attitudes

A growing body of research documents the enduring legacies of political violence on individuals’ perceptions, behaviors, and attitudes. Using increasingly fine-grained micro-level data, scholars have demonstrated that traumatic experiences are not only deeply personal but also socially and politically consequential, with effects transmitted across time and space (Charnysh et al. Reference Charnysh, Finkel and Gehlbach2023; Walden and Zhukov Reference Walden and Zhukov2020). While violence imposes immediate physical and psychological harm, such as post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD), its broader impact often unfolds over time through shifts in identity, collective memory, and political expression (Canetti-Nisim et al. Reference Canetti-Nisim, Halperin, Sharvit and Hobfoll2009; Lerner Reference Lerner2022).

The political consequences of historical trauma can be broadly categorized into two types: exclusive and inclusive effects. On the one hand, traumatic experiences often foster exclusive political attitudes manifested in animosity toward perpetrators. State-sponsored repression, such as civil wars or mass purges, has been shown to reduce trust in political institutions and fuel rejection of the regime among survivors and witnesses (Grosjean Reference Grosjean2014; De Juan and Pierskalla Reference De Juan and Pierskalla2016; Balcells Reference Balcells2012). These backlash reactions may take the form of explicit public protest (Fouka and Voth Reference Fouka and Voth2023; Rozenas et al. Reference Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov2017) or more subtle expressions of disaffection and silence (Wang Reference Wang2021; Kuran Reference Kuran1991). Arguably, these effects often extend beyond direct victims, reaching geographically distant bystanders who experience psychological dissonance or moral injury (De Juan et al. Reference De Juan, Gläßel, Haass and Scharpf2023). Furthermore, this broader pattern has been observed across diverse contexts, where past violence continues to shape political discontent and regime skepticism (Lupu and Peisakhin Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017). While these effects tend to be strongest shortly after the violence, they often re-emerge during moments of political contestation, suggesting that trauma remains latent and conditional on the opportunity structure (Rozenas et al. Reference Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov2017).

Trauma also has inclusive effects, strengthening solidarity within the victimized group. Research shows that exposure to violence can increase civic cooperation, altruism, and collective action within affected communities (Bauer et al. Reference Bauer, Blattman, Chytilová, Henrich, Miguel and Mitts2016). In some cases, shared suffering fosters empathy toward other victimized groups, particularly when the trauma is framed in moral or humanitarian terms (Dinas et al. Reference Dinas, Fouka and Schläpfer2021; Wayne and Zhukov Reference Wayne and Zhukov2022; Hong et al. Reference Hong, Mo and Paik2025). These inclusive effects are often rooted in localized collective memory and transmitted across generations via family networks and community institutions (Lupu and Peisakhin Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017; Wang Reference Wang2021; Fouka and Voth Reference Fouka and Voth2023). Furthermore, the inclusive tendencies frequently coexist with exclusionary ones. Trauma can reinforce parochial altruism which strengthens bonds within the group while sharpening boundaries against outsiders. Feelings of existential threat and vulnerability rooted in collective memories of violence and trauma increase the desire for national strength and cohesion, leading to increased support for security-oriented, nationalist, or conservative positions (Canetti-Nisim et al. Reference Canetti-Nisim, Halperin, Sharvit and Hobfoll2009; De Juan et al. Reference De Juan, Haass, Koos, Riaz and Tichelbaecker2024). Historical victimization often intensifies exclusionary attitudes toward out-groups and fuels hardline and hawkish preferences in foreign and economic policy (Kupatadze and Zeitzoff Reference Kupatadze and Zeitzoff2021; Xu and Zhao Reference Xu and Zhao2023; Acharya et al. Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018; Ko Reference Ko2022). These reactions are not purely reactive but are often sustained by public narratives that frame the group’s suffering as morally exceptional or historically redemptive.

The dual legacy of historical trauma, both binding in-group solidarity and sharpening the boundaries between in-group and out-group, provides a mechanism for understanding how collective memory informs the formation of political attitudes. In particular, such trauma may not only sustain a sense of shared grievance but also heighten sensitivity to perceived external threats, thereby shaping contemporary preferences for specific political orientations. These include patriotism, understood as affective attachment to the nation and its people (Huddy and Khatib Reference Huddy and Khatib2007); protectionism, as a symbolic defense of national economic interests and sovereignty (Mansfield and Mutz Reference Mansfield and Mutz2013); and support for strong leadership, which often emerges in response to perceived insecurity, instability, or national decline (Merolla and Zechmeister Reference Merolla and Zechmeister2009; Wayne and Zhukov Reference Wayne and Zhukov2022).

Emotional legacies of historical trauma and political consequences

This study asks how narratives of historical victimhood shape political attitudes through emotional mechanisms. To address this question, I draw on theories of collective memory and its transmission (Halbwachs Reference Halbwachs1992). I argue that historical memory becomes embedded in public consciousness through a dual process of factual recollection and emotional resonance, blending objective information with subjective affect. This dynamic is especially potent in societies with a legacy of political violence, where victimhood narratives deepen both cognitive understanding of the past and emotional reactions such as anger, fear, or humiliation. These emotional responses, in turn, shape individual perceptions and sustain a shared sense of collective identity.

I extend this argument by proposing that collective memory, particularly narratives of victimhood, plays a dual role. Victimhood mentality, which interprets the world through a victim–perpetrator lens, functions both as a unifying force and a boundary marker. Internally, it fosters national solidarity and patriotic sentiment by emphasizing a shared sense of collective anguish. Externally, it cultivates exclusionary attitudes toward perceived out-groups or threats, polarizing perceptions between “us” and “them.” In this way, collective trauma simultaneously consolidates internal cohesion and sharpens intergroup distinctions.

Building on this framework, I advance two hypotheses. First, I argue that historical victimhood cues elicit distinct emotional responses, particularly anger and fear. Second, I posit that anger triggered by such narratives reinforces collective identity and assertive policy preferences by enhancing in-group cohesion and a shared sense of historical grievance. By activating emotional reactions, collective memory retains its mobilizing influence on political attitudes.

How collective memory mobilizes: Narrative, emotion, and identity

In what ways does collective memory of political violence continue to mobilize political attitudes in the present? To answer this question, I begin by examining the nature of memory itself. Memory is neither static nor uniform. It is fragmented, selective, and context-dependent (Nora Reference Nora1989). It operates on multiple levels, influencing how individuals process and respond to the past. A defining feature of memory is its dual function. It serves as both a repository of factual knowledge and a source of emotional resonance. On the one hand, memory acts as an archive of knowledge, which refers to the storage capacity of facts and events from the past. Memory records the relevant information at the moment and retrieves the preserved narratives that align with current needs or interpretations. Unlike digital or archival data, human memory is not cumulative but curated (Han Reference Han2024). It is an interpretive reconstruction rather than passive recall. On the other hand, it acts as an archive of emotion or sentiment, which makes human memory distinct from other types of memory. Remembering is a fundamentally retrospective process of recalling the stored knowledge and is thus subject to personal interpretation and reproduction. This inevitably leads to the formation of emotional states such as fear and anger or sentiments of pride and satisfaction. Thus, remembering proceeds as an amalgamation of facts and feelings, where not only the facts matter but also how they are selected, preserved, and emotionally processed in the formation of memories.

Second, memory operates at both the individual and collective levels. Memory is a mixture of shared experiences and personal elements. At the individual level, memory begins with a private encounter, an event or moment experienced in solitude. This encounter gains meaning through repeated reflection and emotional attachment, forming an authentic experience rooted in time and space (Benjamin Reference Benjamin and Arendt2019). Then, what becomes a collective memory? It is not merely an accumulative combination of individual memories but rather shared knowledge formed through an intersubjective understanding of the past (Jo Reference Jo2022, 772). This points to the notion that collective memory is socially constructed over long periods of time (Halbwachs Reference Halbwachs1992). Events at any given moment do not automatically translate into collective memory; only selected aspects of the past are transmitted and preserved as collective memory and allowed to embody symbolic significance.

Narratives are particularly crucial in the selection and creation of collective memory (Gellner Reference Gellner1983). While information alone intensifies the experience of contingency by highlighting the uncertainty and unpredictability inherent in isolated facts, narratives serve to mitigate this uncertainty and are subject to being interpreted solely within their specific context (Jo Reference Jo2022). Narratives offer a cohesive understanding by providing direction and orientation on how to interpret the past and structure the memory through stable meanings and identities, unlike an aggregation of information presented to the public. Historical narratives forge a shared consciousness that ultimately shapes the collective identity in the present. Therefore, collective memory and narratives, emerging from the interplay of facts and feelings, serve as a powerful binding and mobilizing force. Through remembering, memory ties individuals to specific regions and nations (Assmann Reference Assmann2011). Symbolic representations, such as memorials, museums, and commemorations, act as tools to sustain and transmit collective memory across generations, allowing it to survive beyond specific time and place.Footnote 1

Emotional pathways of political violence and collective memory

Collective memory rooted in political violence has long been recognized as a powerful force shaping public attitudes (Lupu and Peisakhin Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017; Lin Reference Lin2024). Traumatic events, such as (in)discriminate violence, massacres, and systemic repression, leave lasting psychological and political imprints. These memories persist beyond the individual level, transforming into collective experiences through narratives that endow them with symbolic meaning and emotional attachment. While individual physical wounds may heal, some scars become social wounds embedded in the relationships and shared consciousness of the affected community (Kwon Reference Kwon2020).

To explain how historical violence influences contemporary politics, I focus on a particular mechanism of victimhood mentality. Victimhood mentality is a long-term outcome of political and historical trauma, characterized by a persistent worldview that interprets events through a victim–perpetrator dichotomy. This mindset emerges through a deliberate process of narrative construction, in which specific historical injustices are selected, moralized, and passed on as collective knowledge. Victimhood narratives identify perpetrators, emphasize harm and suffering, and frame the events in ways that sustain a moral judgment (Lim Reference Lim2023). They are not neutral reflections of the past but emotionally charged frameworks that shape political cognition and behavior in the present.Footnote 2

These narratives arguably generate emotionally distinct reactions which subsequently influence political attitudes. In this study, I focus on two negative emotions, anger and fear, which differ in their cognitive triggers and behavioral consequences. Anger tends to arise when individuals perceive a moral violation committed by a clearly identifiable actor. It is associated with high levels of certainty and perceived control, and often leads to approach-oriented reactions such as support for retaliation, punishment, or demands for compensation (Petersen Reference Petersen2010; Wayne Reference Wayne2023). Fear, on the other hand, emerges when threats are uncertain or uncontrollable, leading to risk-averse and avoidance-oriented responses (Druckman and McDermott Reference Druckman and McDermott2008; Rehm Reference Rehm2016; Lin Reference Lin2024).

Victimhood narratives can elicit both anger and fear, as they reactivate memories of intentional harm and collective trauma. However, anger is more likely to be triggered when these narratives emphasize moral violation and assign blame to a specific perpetrator group. This fosters a sense of grievance and motivates calls for justice or retribution. Fear, by contrast, may become dominant when narratives emphasizes continued vulnerability or highlights the ongoing coercive power of the former perpetrator. In such contexts, communities may perceive dissent as dangerous and instead opt for political compliance (Rozenas and Zhukov Reference Rozenas and Zhukov2019). Thus, the same memory cue can activate multiple emotions, but the dominant response and its political consequences may differ depending on how the threat is cognitively appraised.

I also argue that anger has uniquely cohesive and defensive effects on collective identity. First, anger defines the moral boundaries of the in-group by singling out those responsible for past injustice. Second, when anger is channeled and amplified through public institutions, such as education, media, or commemoration, it becomes a shared emotional register that binds individuals to a collective identity. These expressions of nationalism and patriotism are not rooted in triumphalism, but in a shared sense of historical grievance and collective anguish.Footnote 3

The unifying role of victimhood narratives has been widely documented. Suffering becomes transgenerational once framed in national terms, strengthening internal solidarity and deepening group identification. Narratives such as China’s “century of humiliation” are known to boost national pride and legitimize state authority by reinforcing collective memory (Xu and Zhao Reference Xu and Zhao2023; Wang Reference Wang2008). By emphasizing the idea that “we” have suffered together, victimhood narratives enhance loyalty to the group, mobilize collective emotion, and intensify patriotic commitment (Huang and Liu Reference Huang and Liu2018). Furthermore, recent research shows that the political consequences of nationalist memory depend on how such narratives are framed. For instance, Ko (Reference Ko2022) finds that while expressions of national pride do not necessarily shift foreign policy preferences, historical trauma narratives elicit more hawkish attitudes among Chinese citizens. This illustrates that victimhood memory can also produce exclusionary effects. By defining perpetrators as outsiders, such narratives intensify the distinction between “us” and “them,” sharpen group boundaries, and justify suspicion, often leading to discriminatory or aggressive policy preferences. As trauma narratives emphasize power asymmetries and national humiliation, they increase perceptions of insecurity, perceived threat, and demand for protection or retribution (Rozenas et al. Reference Rozenas, Schutte and Zhukov2017; Canetti-Nisim et al. Reference Canetti-Nisim, Halperin, Sharvit and Hobfoll2009; Lerner Reference Lerner2022). These dynamics help explain why victimhood memory can generate both inclusive outcomes, such as increased national pride and patriotic attachment, and exclusionary responses, such as stronger group boundaries and support for hawkish security policies.

Following this logic, I propose the following testable statements:

H1. Narratives of historical victimhood elicit distinct emotional responses, such as anger and fear.

H2. Anger triggered by victimhood narratives simultaneously increases inclusive attitudes and exclusive attitudes, while fear has weaker or inconsistent effects.

The politics of historical trauma and emotional mobilization in South Korea

Korea provides a valuable case for examining how historical memories of violence continue to shape collective attitudes and mobilize emotions. Japanese colonization remains central to Korean national identity, rooted in historical trauma and public memory (Shin and Sneider Reference Shin and Sneider2011; Shin and Sneider Reference Shin and Sneider2016). Although generational differences exist, especially among younger Koreans exposed to cultural exchange, the persistence of historical grievances is notable. Survey data consistently show low levels of affinity toward Japan and identify colonization and war as defining historical hardships (Korean General Social Survey 2023; Korea Identity Survey 2005). These attitudes reflect lasting anti-Japanese sentiment shaped by institutionalized remembrance across generations, despite the passage of time and generational change. Notably, colonial memory often outweighs more recent economic events, such as the 1997 IMF crisis, in shaping national identity.

While the legacy of violence may have been disrupted by events such as wartime displacement (Kwon Reference Kwon2020), migration (Kim Reference Kim2010), and the stigma surrounding victimization (Lee Reference Lee2021), memories continue to persist through other channels. Studies on transgenerational trauma suggest that the loss of direct victims can weaken familial transmission of collective memory (Volkan Reference Volkan2001; Kidron Reference Kidron2009). The relocation and dispersion of affected populations may have diluted these narratives. Yet public sentiment in Korea still reflects the imprint of historical violence. One explanation lies in institutional mechanisms, such as education, media, and government commemoration, that preserve and reinforce these memories.Footnote 4 These channels help embed collective trauma into national identity, despite generational change and geographic dispersal.

In 2019, for example, historical memory visibly shaped individual behavior in South Korea through the “No Japan” movement—a grassroots boycott of Japanese products sparked by a trade dispute (Ko and Kim Reference Ko and Kim2023). Japan’s export restrictions reignited longstanding grievances, triggering public backlash rooted in colonial-era trauma. Imports of Japanese beer and cars declined sharply compared to 2018 (Korea Customs Service 2019). This episode highlights how collective anguish can extend into consumer behavior, reflecting deeper political and diplomatic attitudes. (Fouka and Voth Reference Fouka and Voth2023) documents a similar pattern in Greece, where memories of German wartime atrocities resurfaced during the 2009 debt crisis, affecting German car sales and political sentiment. Both cases underscore how institutionalized memory, when activated by external shocks, can turn latent historical grievances into political action from below (De Juan et al. Reference De Juan, Gläßel, Haass and Scharpf2023).

Korea’s national narrative of Japanese colonization is framed through a victim–perpetrator lens, reinforcing anti-Japanese sentiment in public discourse (Lim Reference Lim2010; Shin and Sneider Reference Shin and Sneider2011; Shin and Sneider Reference Shin and Sneider2016). Japan is depicted as a perpetual aggressor, while Korea is portrayed as a unified victim bound by shared suffering. This framing sustains public indignation and demands for redress. Revelations of atrocities, such as Unit 731’s biological warfare, made widely known in the late 1990s through media coverage (Kristof Reference Kristof1995; Harris Reference Harris1995), have intensified these emotions. History education highlights heroic resistance during the colonial period while drawing a sharp moral distinction between anti-colonial activists and pro-Japanese collaborators (Ministry of Patriots and Veterans Affairs 2024). This division continues to structure social status and moral judgment in the present.

The 2022 Korean Perceptions of East Asia Survey, conducted by Hankook Research on behalf of the East Asia Institute, reveals that more than half of respondents report a negative impression of Japan. Among those with negative views, 60 percent cite Japan’s failure to properly acknowledge its colonial rule as the primary reason, ranking well above other issues such as territorial disputes or political disagreements. These results suggest that unresolved historical grievances remain central to South Korean public opinion. When asked what steps are necessary to improve bilateral relations, a majority of respondents prioritize resolving colonial-era issues, such as those involving comfort women or forced labor, over policy-oriented concerns like economic or military cooperation. Furthermore, over 60 percent of the public evaluates current Korea–Japan relations as poor, attributing the tension to Japan’s perceived lack of contrition. These attitudes are not confined to specific demographic groups, but rather reflect a broad public consensus across age and gender. This pattern underscores the extent to which institutionalized memory of Japanese colonization continues to inform collective identity and political discourse. Even in the absence of direct personal/familial experience, historical narratives persist as emotionally and politically salient forces in contemporary South Korea.

This pattern is not unique to Korea. Rather, South Korea serves as an analytically useful case for understanding how institutionalized memory can activate emotional and political responses. Accordingly, the findings of this study are generalizable to societies where the memory of historical trauma is embedded in formal institutions, victimhood narratives are politicized and publicly salient, and intergroup boundaries between former perpetrators and victims remain morally charged in the present. For example, in the case of Holocaust remembrance, family testimony remains important, but education and media have played an outsized role in institutionalizing the trauma across generations (Wayne and Zhukov Reference Wayne and Zhukov2022). In such contexts, memory operates not as a private inheritance but as a public repertoire.

Empirics

Evidence from survey experiment

This section presents evidence from an original survey experiment designed to examine how historical memories of violence influence emotional responses and political attitudes. The study tests whether narratives of past trauma function not only as repositories of factual knowledge but also as emotionally charged stimuli that shape contemporary beliefs. The study tests two core claims. First, historical memories are embedded in both factual and affective narratives:

H1. Narratives that recall historical violence elicit distinct negative emotions, particularly anger and fear.

Second, these emotional responses play a mobilizing role:

H2. Anger triggered by victimhood narratives simultaneously increases inclusive attitudes and exclusive attitudes, while fear has weaker or inconsistent effects.

Data and measurement

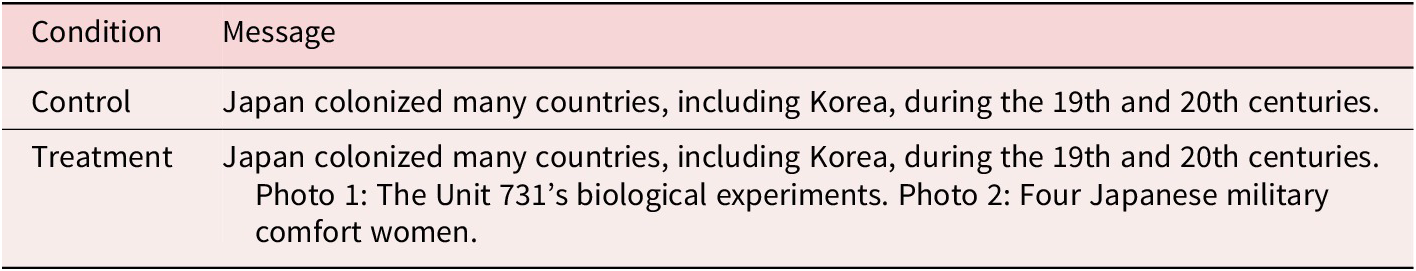

This study draws on an original online survey experiment conducted in March 2024 with 1,000 adults from a nationally representative sample in South Korea. Prior to treatment assignment, respondents completed baseline questions on sociodemographics (age, gender, education, income) and historical knowledge. Respondents were randomly assigned to a control or treatment group. The treatment group was exposed to a brief symbolic prime: two photographs accompanied by short descriptions. The first showed Unit 731’s biological experiments; the second depicted Korean comfort women. The content reflects historical narratives found in Korean education (Lee and Park Reference Lee and Park2024) and the treatment was designed primarily as a graphic and symbolic reminder of historical atrocity. Covariate balance tests (Table A.6) indicate that treatment and control groups are well balanced in terms of prior pride in Korean history, democracy, and economic achievement, perceived qualities for leadership, and historical knowledge, suggesting that randomization mitigates the concern of systematic pre-treatment differences.

After reading the treatment message, respondents were asked to report their emotional responses and political attitudes related to Japanese colonization. Both groups were prompted to reflect on the historical memory of Japanese colonization (1910–1945) and were then asked five separate emotion-related questions. Each question asked: “To what extent does recalling Japanese colonization make you feel [afraid/scared/angry/hateful/resentful]?” Responses were recorded on a 5-point Likert scale. Drawing on prior work that distinguishes core negative emotions (Petersen Reference Petersen2010; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Brader, Groenendyk, Gregorowicz and Hutchings2011; Druckman and McDermott Reference Druckman and McDermott2008; Wayne Reference Wayne2023), I grouped these items into two validated categories: anger (angry, resentful, hateful; Cronbach’s

![]() $ \alpha =0.90 $

) and fear (afraid, scared; Cronbach’s

$ \alpha =0.90 $

) and fear (afraid, scared; Cronbach’s

![]() $ \alpha =0.93 $

). Exploratory factor analysis confirmed that these items loaded onto two separate factors, reflecting distinct emotional dimensions. This categorization also allows me to assess whether anger and fear, two key but theoretically distinct emotional responses to historical trauma, differentially affect support for nationalist or protective policy preferences.

$ \alpha =0.93 $

). Exploratory factor analysis confirmed that these items loaded onto two separate factors, reflecting distinct emotional dimensions. This categorization also allows me to assess whether anger and fear, two key but theoretically distinct emotional responses to historical trauma, differentially affect support for nationalist or protective policy preferences.

Main results

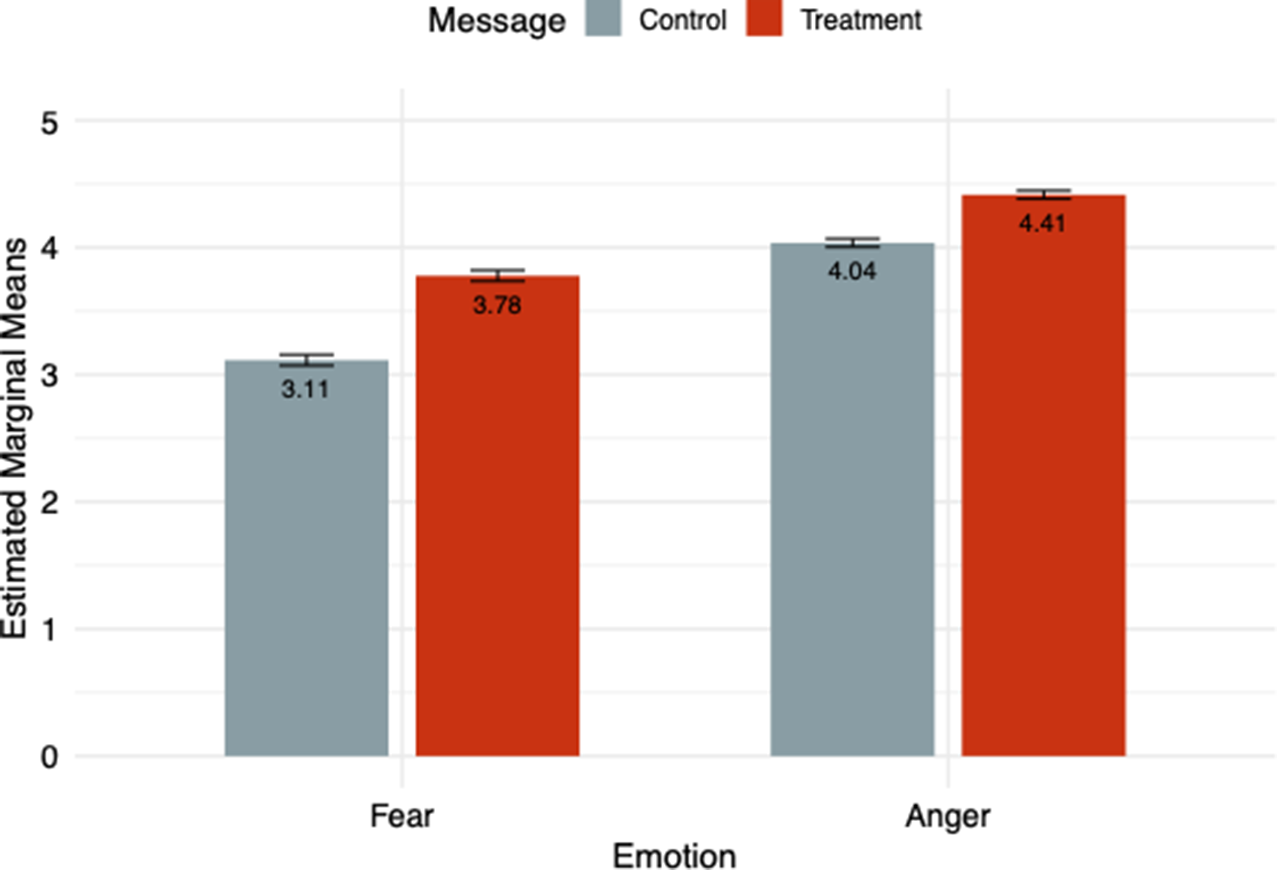

To evaluate H1, Table 2 presents OLS regression results estimating the effect of treatment on anger and fear, controlling for age, gender, education, and income. The treatment significantly increases both emotions. Respondents exposed to graphic reminders of colonial atrocities report significantly higher levels of anger (+0.38) and fear (+0.66), both statistically significant at

![]() $ p<0.001 $

. Figure 1 further illustrates these results using estimated marginal means. In the control condition, where respondents are simply reminded of colonization, average levels of fear and anger are already moderately high (3.11 and 4.04, respectively), reflecting the emotional salience of historical trauma. However, in the treatment group, which received vivid reminders of specific atrocities (Unit 731 and comfort women), emotional intensity rises notably. Fear increases by approximately 21 percent (to 3.78), and anger rises by 9 percent (to 4.41).Footnote

5 These findings support H1 that emotionally charged historical narratives intensify the affective dimension of collective memory, reactivating latent emotions embedded in public consciousness.

$ p<0.001 $

. Figure 1 further illustrates these results using estimated marginal means. In the control condition, where respondents are simply reminded of colonization, average levels of fear and anger are already moderately high (3.11 and 4.04, respectively), reflecting the emotional salience of historical trauma. However, in the treatment group, which received vivid reminders of specific atrocities (Unit 731 and comfort women), emotional intensity rises notably. Fear increases by approximately 21 percent (to 3.78), and anger rises by 9 percent (to 4.41).Footnote

5 These findings support H1 that emotionally charged historical narratives intensify the affective dimension of collective memory, reactivating latent emotions embedded in public consciousness.

Table 1. Experimental conditions

Figure 1. Estimated marginal means of emotional responses by treatment condition.

Table 2. Estimated effects of victimhood narrative treatment on emotion

Note:*p<0.05; **p<0.01; ***p<0.001.

Next, I examine how emotional responses to historical victimhood shape political attitudes. I assess whether emotions, especially anger and fear, serve as affective mechanisms that unify the in-group and mobilize exclusionary preferences toward out-groups. Drawing on theories of trauma-driven identity formation, I analyze how these emotions influence preferences for national identity, domestic leadership, security posture, and economic protectionism. Respondents rated their agreement on a 5-point Likert scale (1 = Strongly Disagree, 5 = Strongly Agree) with the following statements: (1) “I feel a strong sense of pride in the Korean identity” (National Pride); (2) “A strong patriotism and national identity for the prosperity of the nation are needed” (Patriotic Sentiment); (3) “We need a strong leader to handle the misfortunes of the nation” (Support for Strong Leadership); (4) “South Korea should implement a stronger foreign policy and security measures to prepare for external threats and invasions” (Support for Hawkish Security); (5) “To protect domestic industries, tariffs should be imposed on Japanese products such as beer and automobiles” (Support for Trade Barriers).Footnote 6

Table 3 presents the results of a causal mediation analysis testing whether emotional responses mediate the effects of historical trauma exposure on five outcome variables (Imai et al. Reference Imai, Keele and Tingley2010; Tingley et al. Reference Tingley, Yamamoto, Hirose, Keele and Imai2014). The analysis yields two key findings. First, anger partially mediates political outcomes, while the direct effect of treatment is weak. Across several outcomes, the Average Causal Mediation Effects (ACME) through anger are positive and statistically significant. For example, treatment-induced anger increases support for trade protectionism by 0.144 points (

![]() $ p<0.001 $

), and patriotic sentiment by 0.085 points (

$ p<0.001 $

), and patriotic sentiment by 0.085 points (

![]() $ p<0.001 $

). However, the total treatment effects are generally small and statistically insignificant, suggesting that while anger intensifies political preferences, the treatment itself does not directly shift attitudes in a uniform or robust way. This distinguishes between the role of emotion and the informational content of treatment that the treatment activates latent emotions, and those emotions, rather than the treatment alone, shape political reactions.

$ p<0.001 $

). However, the total treatment effects are generally small and statistically insignificant, suggesting that while anger intensifies political preferences, the treatment itself does not directly shift attitudes in a uniform or robust way. This distinguishes between the role of emotion and the informational content of treatment that the treatment activates latent emotions, and those emotions, rather than the treatment alone, shape political reactions.

Table 3. Causal mediation analysis: Treatment

![]() $ \to $

Emotion

$ \to $

Emotion

![]() $ \to $

Political Attitudes

$ \to $

Political Attitudes

Note: ACME = Average Causal Mediation Effect; ADE = Average Direct Effect.

Significance levels: * p<0.05, ** p<0.01, *** p<0.001. Bootstrap simulations = 1000.

Second, fear does not function as a mediator and appears less politically consequential than anger. The mediation pathways through fear are statistically insignificant across all outcomes. For example, the ACME of fear on national pride is negative but not significant, and its estimated effect on trade protection is also insignificant. However, the total effect of the treatment is negative in some cases, suggesting that the treatment in this setting may elicit responses such as unease, withdrawal, or disappointment in the state’s historical role. These reactions may weaken symbolic attachments like national pride or patriotic sentiment. That said, these effects are inconsistent and not robust across all outcomes, indicating that fear does not systematically shape political attitudes. Rather, fear may at times coincide with attitudinal dampening, but it does not mediate the political consequences of historical trauma exposure.

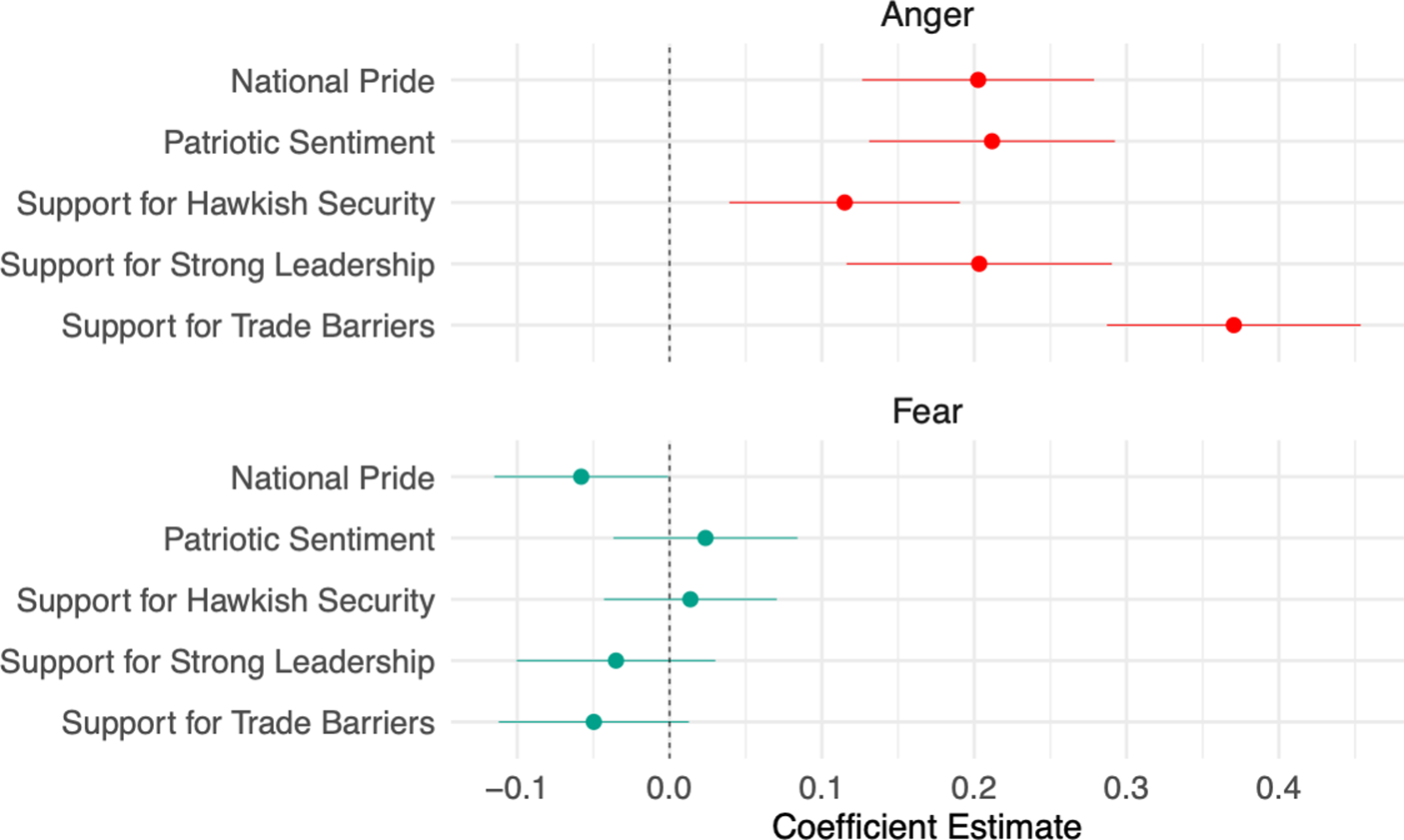

To further explore how emotions independently shape political attitudes (H2), I examine the direct associations between anger, fear, and key outcomes regardless of treatment status. Figure 2 visualizes the relationship between emotions and individual political attitudes. This model does not assume full mediation but illustrates the potential pathways through which memory-induced emotions may influence preferences. Higher levels of anger and fear indicate stronger negative emotions associated with the memory of Japanese colonization. Figure 2 reveals that anger is positively correlated with an increased emphasis on pride in Korean identity and patriotism, while fear and treatment are not significantly associated with different levels of national pride and patriotic moods. Additionally, anger is positively linked to support for a strong government role in security, trade, and leadership.

Figure 2. Effects of anger and fear on inclusive and exclusive political attitudes.

These findings reveal two important patterns. First, emotional responses, especially anger, play a central role in linking collective victimhood to political preferences. Second, the lack of treatment effects suggests that emotions tied to historical trauma are already deeply internalized, so that an additional graphic and symbolic reminder in the treatment has minimal marginal impact. This bolsters the theoretical expectation that historical memory operates through emotional channels, rather than factual correction or updating.

The divergence between anger and fear reflects their distinctive cognitive and motivational profiles. Anger is often associated with active motivations such as seeking justice, punishment, or redress in response to perceived moral violations, even when the harm is vicarious. In contrast, fear tends to generate avoidance, passivity, or risk aversion, which are less politically activating. In the context of this study, anger appears to be more politically mobilizing because it is socially constructed and sustained through institutionalized narratives of national suffering that encourage moral outrage and collective solidarity. Fear, while also intensified by the memory of colonization, lacks this directive or action-oriented framing. As a result, anger, not fear, emerges as the more consistent and impactful driver of political attitudes across the domains examined here.

Consistent with recent work on memory saturation (Shelef and vanderWilden Reference Shelef and vanderWilden2024; Lee and Park Reference Lee and Park2024), the results suggest that reminders of collective trauma no longer shift attitudes when emotional interpretations of the past are already internalized. Simply invoking memory elicits affective reactions that shape preferences. In this context, historical memory becomes a reservoir of emotion, not just fact, sustaining nationalist sentiment and support for assertive policy responses. The findings emphasize the endurance of emotion-laden memory and the limits of informational framing in reshaping public attitudes.

Heterogeneous effects

I examine whether treatment effects vary by education and income, two key indicators of socioeconomic status that shape political engagement and responsiveness. In additional analyses, I also consider political ideology, measured on a left–right scale (0–10). Prior studies suggest that lower-status groups are more vulnerable to political disengagement or alienation and may therefore be more responsive to populist appeals and framing strategies (Gidron and Hall Reference Gidron and Hall2017). Tables A.9 and A.10 report heterogeneous treatment effects on anger and fear. Across all subgroups, the treatment consistently increases both emotions, indicating that emotional responses are not confined to particular socioeconomic or ideological segments.

Tables A.11–A.15 examine how emotions affect political outcomes across subgroups. Anger remains the most consistent predictor of national identity and policy preferences. However, notable subgroup differences emerge. For example, fear has a negative effect on pride in Korean identity among respondents with lower education and income, but this effect does not appear among higher-status groups (Table A.11). Conversely, anger predicts stronger support for hawkish security policies among those below college or below the income median, indicating that grievance-driven assertiveness is more pronounced among lower-status groups (Table A.14). Across the remaining outcomes, anger effects are consistently positive, whereas fear effects remain inconsistent or null. These findings not only reinforce the central role of anger but also demonstrate that socioeconomic status conditions the translation of emotional responses into political attitudes. Beyond socioeconomic status, I also examine whether emotional effects vary by political ideology (left–right, 0–10 scale). Among right-leaning respondents, anger is positively associated with support for strong leadership and a strong foreign policy, whereas fear reduces support for strong leadership (Tables A.13–A.14).

Discussion

This study investigates the emotional legacy of historical trauma and its influence on contemporary political attitudes. It asks how emotionally charged narratives of historical trauma, especially those institutionalized through education and state-led commemoration, influence national identity, patriotic mood, and policy preferences in the present. Drawing on a survey experiment in South Korea, the study focuses on memories of Japanese colonial violence and the emotional responses they elicit. The theoretical framework centers on victimhood mentality as a socially constructed interpretive lens through which individuals make sense of historical injustice. Rather than treating memory as a passive inheritance, the study conceptualizes it as an active force, made politically consequential through emotional resonance. Collective memory fosters a sense of belonging not simply through shared facts, but through the shared recognitions that others carry the same historical grievance and collective anguish. This affective connection sustains a collective identity anchored in past suffering. The empirical findings show that anger, more than fear, plays a central role in translating historical trauma into both inclusive and exclusive political outcomes. Anger enhances national pride and patriotic sentiment by emphasizing moral unity and group cohesion, yet it also fuels suspicion toward out-groups and support for hardline stance.

The findings have an implication for understanding how the past is mobilized in the present. Historical trauma can unify a nation around shared suffering and become victimhood nationalism (Lim Reference Lim2010), but they can also polarize, justify exclusion, and intensify antagonism (Ko Reference Ko2022). Political elites, both democratic and autocratic, often invoke historical trauma selectively to advance present-day goals and consolidate authority by attributing hardship to external enemies and demanding national atonement. While this study focuses on the victim’s perspective, future research may investigate how narratives of perpetration evolve, particularly amid rising efforts to ‘detoxify’ national memory and reject collective guilt (The Economist 2024). Such counter-narratives may illuminate the emotional and political consequences of historical denial, apology, or reappropriation (Kitagawa and Chu Reference Kitagawa and Chu2021).

Furthermore, this study sheds light on the dual impact of historical trauma in post-conflict societies. While it can mobilize political engagement, it may also deepen social and ideological divisions. The effect of reinvigorating emotionally laden memories of trauma may vary depending on individuals’ social position. For example, results presented in the appendix (Table A.14) show that anger is more strongly associated with hawkish policy preferences among those with lower educational attainment or below-median income, suggesting that grievance-driven assertiveness resonates more deeply with lower-status groups. This may reflect a broader trend in contemporary domestic politics, where emotional appeals to collective victimhood can activate political participation while simultaneously heightening support for exclusionary, nationalist, and/or far-right agendas. In this way, the mobilizing function of memory can become a source of polarization, as historical grievance is unevenly processed and politically expressed across socioeconomic lines (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Rogowski and Sutherland Reference Rogowski and Sutherland2016).

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/jea.2025.10017.

Acknowledgements

The author thanks Erin Lin, Sarah Brooks, Jan Pierskalla, Marcus Kurtz, Hyeok Yong Kwon, and two anonymous reviewers for their helpful comments and feedback. Any remaining errors are the author’s own.

Competing interests

The author declares none.

Seobin Han is a Ph.D. candidate in Political Science at The Ohio State University. Her research examines how state narratives, collective memory, and historical trauma shape political attitudes and mobilization in East Asia.