State formation and democratization have proven to be inherently organic, long-term, and complex processes that are extremely difficult to impose from the outside. Post-conflict countries are the least favorable environments in which strong and effective governance can take root and democracy can flourish. They are typically quite poor, having lost years of potential economic growth and development; they have low levels of institutional and human capacity that have been further attenuated by extended conflict; and they are home to populations with sociopolitical cleavages that have led to, and become hardened by, violent civil conflict. Nevertheless, the international community, led by the United Nations, acts on the belief that a strong state and a democratic political system are best suited to managing political conflict and presumes to be able to build the necessary administrative and democratic institutions to underpin modern political order and peace in these fragile countries.

The crux of the puzzle addressed in this book is why the international community has been relatively unsuccessful in building the peace it thinks it is building in post-conflict states. This chapter lays the foundation for the book's approach to this puzzle and describes the manner in which it builds its conceptual, empirical, and practical contributions. It begins with an overview of the practice of international peacebuilding interventions, defining, in particular, the aspirational underpinnings of the transitional governance approach to transformative peacebuilding that is the focus of this inquiry. Next, through a brief review of the existing literature I make the case that we need to better understand the limitations of transformative peacebuilding, and I outline the unique argument this book builds in doing so. The chapter then outlines the empirical approach underlying this research, describing the outcomes of interest and the logic behind the case selection and research design.

What is Peacebuilding?

Peacebuilding is the most extensive and transformative type of peacekeeping intervention undertaken by the international community. Where traditional peacekeeping entails international assistance to maintain a ceasefire among former combatants, peacebuilding constitutes a project to transform a post-conflict country's sociopolitical landscape so as to prevent the possible recurrence of conflict. In the aftermath of the Cold War, the UN's peacekeeping and peacebuilding portfolio became one of its fastest-growing and most distinctive endeavors for two main reasons. First, violent civil conflict around the globe peaked in the early 1990s as the stability wrought by the Cold War ended, although the proportion of countries embroiled in civil conflict then started to decline steadily.Footnote 1 Second, the end of the bipolar global rivalry between the United States and the Soviet Union meant that the UN Security Council could finally begin to agree to peacekeeping mandates under Chapters VI and VII of the UN Charter.Footnote 2 The Security Council tripled the peacekeeping operations it mandated between 1987 and 1994 and the UN's annual peacekeeping budget climbed from $230 million to $3.6 billion in the same period.Footnote 3 The figure is double today: the approved UN peacekeeping operations budget in the fiscal year from July 2014 to June 2015 was just over $7 billion. Over the past two decades, the UN's peacekeeping budget has been about triple its regular operating budget.Footnote 4 Moreover, peacebuilding is essentially a UN affair: its interventions are by far the predominant form of multilateral peace operation since 1945.Footnote 5

The broad mandate of the UN Department of Peacekeeping Operations covers a large range of activities – including ceasefire monitoring, humanitarian assistance, military demobilization, power-sharing arrangements, support for elections, transitional administration, and operations to strengthen the rule of law and promote economic and social development.Footnote 6 Former UN Secretary-General Boutros Boutros-Ghali laid out the conceptual foundations of the newly ambitious and growing UN role in peace and security that he presided over as the Cold War ended in his seminal report, An Agenda for Peace.Footnote 7 He detailed the interdependent roles – preventive diplomacy, peacemaking, peacekeeping, and post-conflict peacebuilding – that he foresaw the UN carrying out in the rapidly evolving international system. Over the course of the past quarter-century, the practice of peace operations has indeed grown in complexity and ambition, as Boutros-Ghali anticipated. Although this evolution has not been strictly chronological, a number of analysts have fruitfully classified UN peacekeeping strategies in generational paradigms.Footnote 8 The bulk of the UN's peace operations since the end of the Cold War have focused on post-conflict peacebuilding, which Boutros-Ghali defined as “action to identify and support structures which will tend to strengthen and solidify peace in order to avoid a relapse into conflict.”Footnote 9 Similarly, the influential Brahimi Report on UN peace operations defined peacebuilding as “activities undertaken on the far side of conflict to reassemble the foundations of peace.”Footnote 10

The Transitional Governance Approach to Transformative Peacebuilding

This book defines peacebuilding, following scholarly and practical convention, as the international community's attempts to transform a post-conflict country through intervention. What I term transitional governance, the focus of this book, is a specific type of peacebuilding endeavor for a particular environment: it is a transformative approach to forging sustainable peace in nations riven by civil war by crafting the administrative and political governance institutions to underpin lasting peace. Often other important peacebuilding dimensions – such as improving internal security, resettling refugees and internally displaced persons, and reconstructing a market-based approach to economic development – go hand in hand. The presence of an international coercive force, represented iconically by UN blue helmet troops and police but sometimes handled by NATO and other alliances, is often a crucial element of multidimensional peace operations.Footnote 11 Here, nevertheless, I restrict the analytical lens to focus on the engineered attempt at simultaneous statebuilding and democratization in post-conflict countries. Via this form of peacebuilding through transitional governance, the UN pursues state effectiveness and democratic legitimacy as the two essential ingredients of modern political order and the necessary underpinnings of lasting peace.

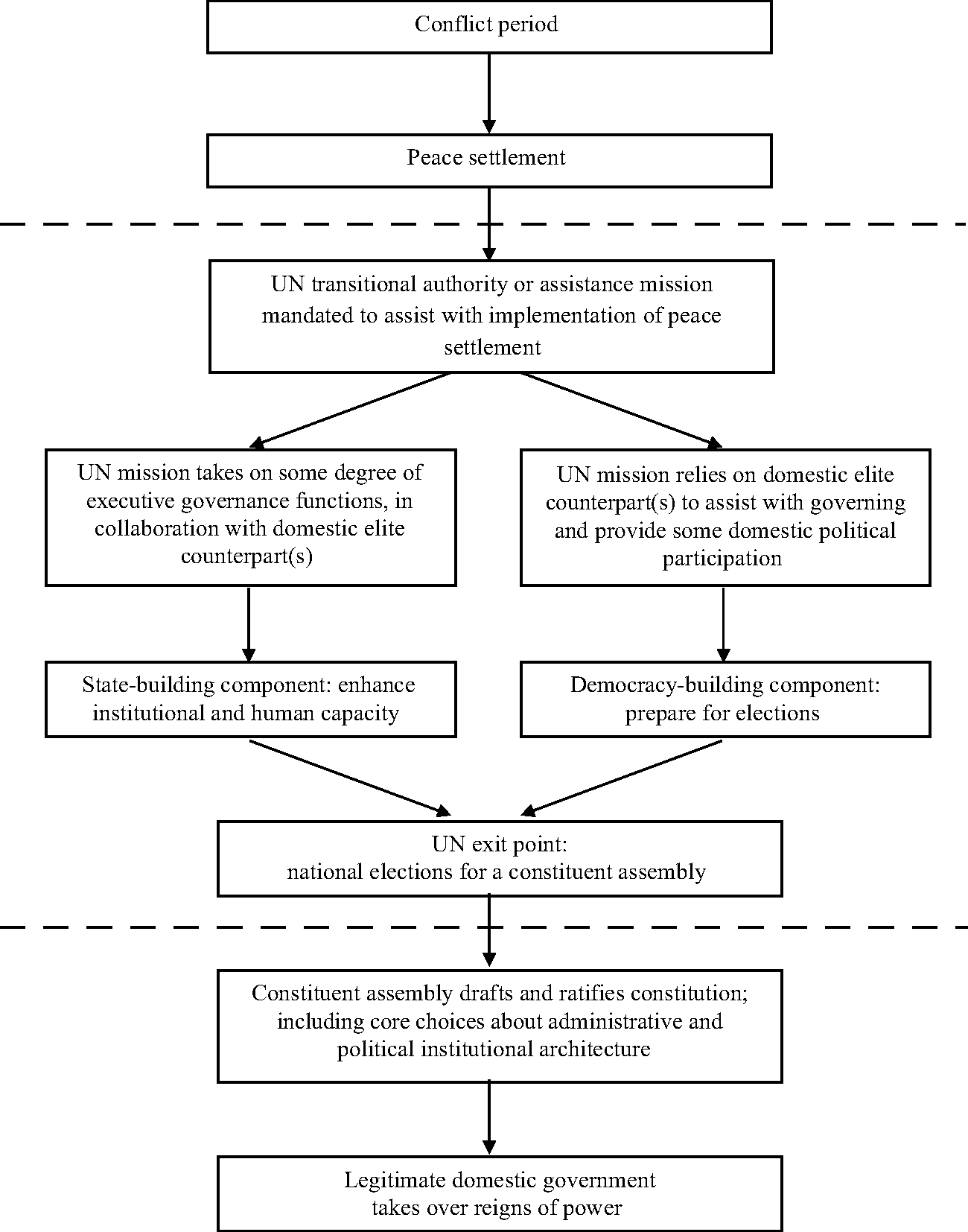

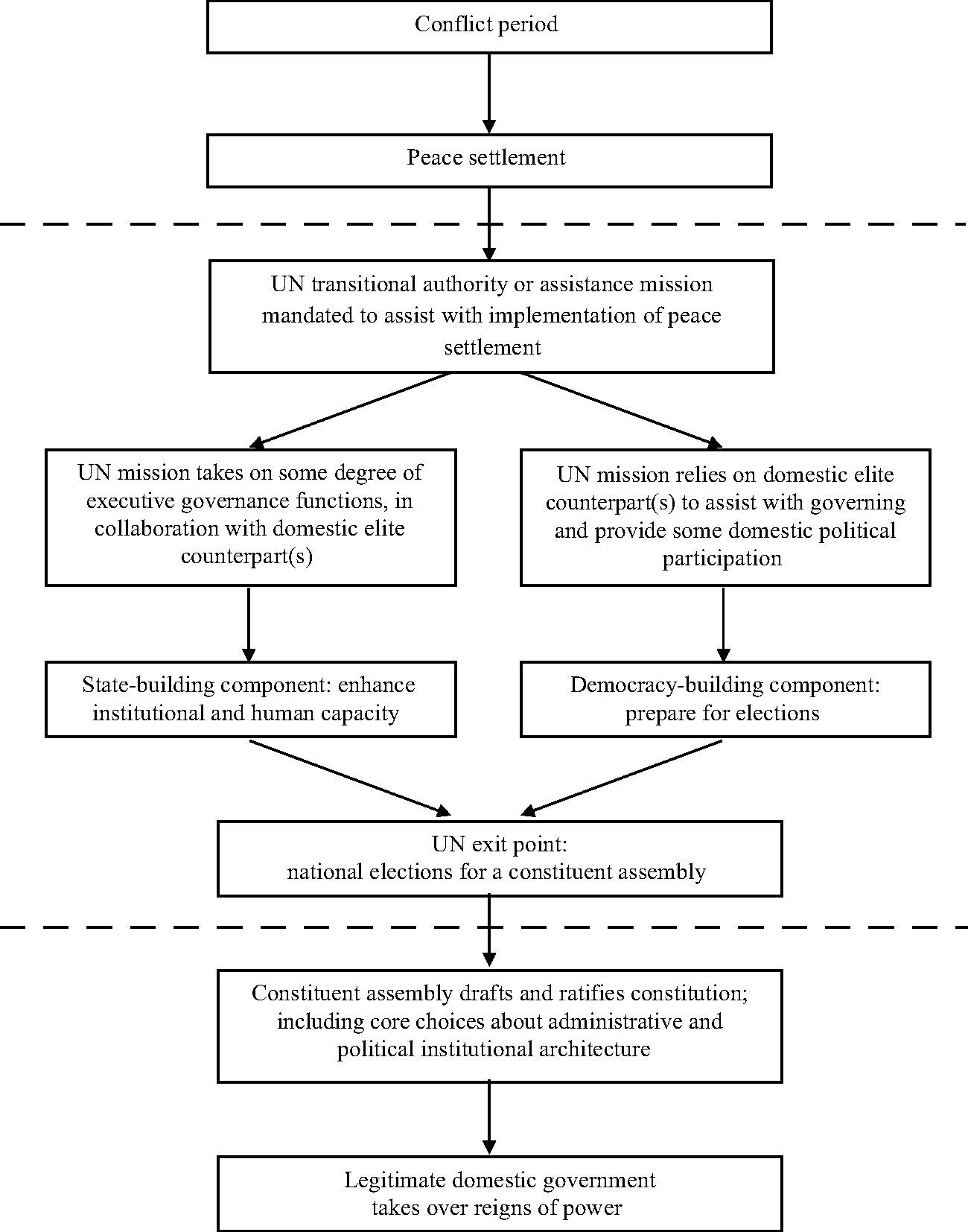

To date, the UN has not laid out an explicit model of transitional governance. Hence, I offer here an inductive definition, built through an examination of the mandates of the peace operations that attempt this manner of transformative peacebuilding.Footnote 12 A negotiated peace settlement among warring elites, typically brokered by the United Nations, marks the end to violent civil conflict. Transformative peacebuilding through transitional governance begins, subsequently, when a UN transitional authority or assistance mission is mandated by the UN Security Council to assist with the implementation of the peace agreement over a specified transitional period, typically two to three years. The hallmark of transitional governance – distinguishing it from other, less transformational versions of multidimensional peacekeeping – is that the appointed mission is responsible, to some degree, for performing the executive functions of the state.Footnote 13 Over the course of the transitional period the UN relies on a small group of domestic counterparts – sometimes a body that explicitly shares power among competing local groups – to assist with governance and to provide some form of domestic political participation in the process. Simultaneous processes of statebuilding and democratization are thus embedded in the transitional governance approach. Finally, the transitional period culminates in a UN-organized national election for a constituent assembly.Footnote 14 Once that representative body deliberates and ratifies a new constitution, making core choices about institutional architecture along the way, it is transformed into a new, post-conflict national legislature. At this point, while the UN and many international aid organizations remain involved in various forms of post-conflict assistance, a legitimate domestic government takes hold of the reins of administrative power. Figure 1.1 depicts the staged process that comprises the transitional governance approach between dotted lines showing its relationship to what comes immediately before and after this period.

Figure 1.1 The transitional governance approach to transformative peacebuilding

The UN's strategy of peacebuilding through transitional governance represents the conviction that transformative peacebuilding is possible. It also represents an implicit theory: the notion that an engineered process of simultaneous state- and democracy-building is the strategy through which international interventions can help conflict-affected countries to transform the sociopolitical dynamics that activated and perpetuated conflict. In turn, the formal institutions pursued in post-conflict countries are the trappings of Weberian, rationalized bureaucracy and procedural liberal democracy because these forms of governance fit the international community's model of statehood. In other words, international norms concerning what is effective and legitimate domestic governance play a major role in shaping the UN's choice of the transitional governance strategy and the formal institutional outcomes it seeks in mounting post-conflict interventions to build sustainable peace.Footnote 15 The international organizations that undertake different elements of peace operations – including the United Nations, the World Bank, and multilateral security groupings such as the North Atlantic Treaty Organization (NATO) – are, in turn, the repositories and promulgators of such international norms.Footnote 16 These norms persist even in the face of evidence from developing countries that the formal structures of bureaucracy and democracy are often fairly ineffective at performing their intended governance functions.Footnote 17

This book tells a particular story about how these international norms and objectives about modern political order meet reality on the ground in recipient post-conflict countries. The theoretical framework advanced in the following chapter, along with the empirical investigation of peacebuilding through transitional governance in Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan, explain and illustrate why and how domestic political elites adapt and use the symbols, resources, and institutions associated with peacebuilding in constructing, instead, their own version of political order, one rooted in neopatrimonialism. Each chapter deals with one particular phase of the peacebuilding pathway, describing the international objectives animating that part of the sequence and then illustrating systematically how pursuit of those objectives was co-opted and upended by domestic elites. I turn now to a brief review of the existing literature in order to explain how this book's argument builds upon and adds to our understanding of peacebuilding.

What Do We Know About Peacebuilding?

Scholars have delved deeply into what began in the early 1990s as a relatively new theoretical space at the intersection of international relations, comparative politics, and public administration in order to examine the increasingly regular and significant phenomenon of post-conflict peacebuilding. Resting on various subdisciplinary perspectives, research on peacebuilding has evolved from the initial set of largely descriptive and policy-prescriptive assessments of peace operations to work that develops a deeper emphasis on the interaction of international and local actors and a more nuanced approach to the politics of peacebuilding. Nevertheless, thinking on peacebuilding tends to inadequately capture the agency of domestic elites on long-term governance outcomes because it underemphasizes the importance of taking a historical perspective on the central challenge of building political order. The bulk of the peacebuilding scholarship, as I illustrate in this section, comes from perspectives that place the peace operations themselves at the center of the inquiry. They thereby explain outcomes on the basis of an intervention's scope, its size, the way it is organized, and so on, contextualized within the constellation of factors that condition its success or failure. My argument differs from these rival explanations in that the analysis privileges the role played by post-conflict elites – their interests, their actions, their agreements – in dealing with international interventions along the temporal sequence represented by the peacebuilding pathway.

The study of peacekeeping has its genealogical roots in international relations, originating with a body of work concerned with explaining when and why interventions successfully achieve and maintain peace. The first wave of research in this field was focused squarely on the peace operations themselves, with a view to understanding why some failed where others succeeded, and primarily based on a case-by-case analysis of post-conflict countries.Footnote 18 Single-country case studies of peace operations abound, many written by experienced practitioners. These are rich in empirical description but pre-theoretical, tending to underplay the causal mechanisms leading to success in outcomes as well as the interaction of international peacebuilding strategies with the domestic political environments in which they unfold. Another line of inquiry focuses on the machinery and processes of transformative peacebuilding – comparing the various mechanisms through which the international community has attempted to aid post-conflict states.Footnote 19 These studies typically come from a liberal internationalist perspective that takes as given the appropriateness of the norms pursued and, while acknowledging the importance of political context in shaping outcomes, many are oriented as evaluations geared toward improving policy and practice. Thus they tend to attribute the relative success of peacebuilding exercises less to causal political dynamics and more to technocratic details subject to policy manipulation such as the scope and implementation of the operational mandates themselves.

The second wave of research on peacebuilding approached similar questions through the adoption of a more deliberate focus on methodological and theoretical rigor, with the aim of developing systematic causal arguments that can be generalized across cases.Footnote 20 Much of this work was concerned with the extent to which peace lasts in post-conflict countries, with the inquiry focused on the factors that either impede or enhance the prospects for peace. The analytical logic driving this work is thus typically probabilistic or what Paul Diehl has termed “behavioral.”Footnote 21 One line of scholarship has essentially confirmed the simple and important finding that peacekeeping operations lengthen the duration of peace after civil wars – peace lasts longer when there are international forces deployed than when former parties to conflict are left to themselves.Footnote 22 Other path-breaking research has identified a number of key determinants limiting the success of peace operations in terms of the incidence of violence and the success of democratization and reconstruction efforts.Footnote 23 These approaches tend to be rationalist, focusing on the degree to which optimal interaction was achieved between the characteristics of an intervention and the context in which it is undertaken. In general, however, this strand of peacebuilding scholarship is restricted to binary outcome measures of the presence or absence of peace and democracy at some relatively short remove from the end of an intervention.Footnote 24 The probabilistic, rationalist, and variable-centered nature of this body of work has yielded important knowledge about the likelihood of specific governance outcomes obtaining in a given timeframe after a peace operation. Yet, overall, this analytical approach has fallen short of developing a causal understanding of longer-term governance outcomes. We still lack a comprehensive explanation of the conditions under which a genuine transformation takes place in post-conflict societies, or a causally reasoned account of why that so often fails to transpire – a gap that the conjunctural and contingent logic of this book's approach seeks to fill.

In its early incarnations, a large body of the peacebuilding scholarship was fused to the desire of peacebuilding practitioners to be more successful. Practice and theory on this topic emerged contemporaneously and many of the first crop of peacebuilding analysts were themselves also practitioners concerned with policy results. Roland Paris argued that this quirk of the peacebuilding scholarship led to a “cult of relevance” that limited theoretical and empirical advances in the field.Footnote 25 A third wave of peacebuilding research connects itself more deliberately, by contrast, to broader debates in international relations theory. Some scholars have, for example, framed the pursuit of peacebuilding goals and norms in relation to broader thinking about the construction and transmission of international norms. Deploying a constructivist or sociological institutionalist lens, these studies have focused on issues such as the replication of externally legitimate norms of statehood, the mechanisms of organizational learning at the United Nations, and the operative frames employed by expatriate peacebuilders working in post-conflict contexts.Footnote 26 Others have considered from a more rationalist ontological perspective the implications of theories of international governance and state sovereignty for peacebuilding practice and policy.Footnote 27

The peacekeeping literature rooted in international relations generally stops short of analyzing the dynamics of transitional governance processes in terms of how international objectives interact with domestic forces. Turning to comparative politics for insight on these domestic dynamics of peacebuilding, other theoretical shortcomings become clear. Scholars have much to impart about the effects of elections and constitutional design on post-conflict peace as well as the connection between peacebuilding and democratization.Footnote 28 Externally imposed and managed interim governments in post-conflict countries have been analyzed in comparison to other types of provisional governance arrangements during major regime transitions.Footnote 29 There has been much lively debate on whether power-sharing, in its various forms, is a valuable post-conflict peacebuilding tool – an intellectual legacy of the predominance of ethnicized civil conflict in the post-Cold War period.Footnote 30 Yet while this focus on institutional form is certainly warranted, it is also essential to explicitly consider the interaction of institutions with the political environment in which they exist and the agency of domestic elites who both control and are constrained by them.

This latter point is made in a different manner by a final group of scholars, who have turned a critical theoretical eye on the very concept and practice of peacebuilding. Some have focused their critique on the implementation of peacebuilding through “neotrusteeship,” or the imposition of governance by an external power, and on the mechanics of international involvement and donor-driven assistance.Footnote 31 Others have reappraised the “liberal peacebuilding” model itself, questioning the international community's motivation in applying it and the appropriateness of its content – Weberian bureaucracy, liberal democracy, and neoliberal economics – in the post-conflict countries in which it is attempted.Footnote 32 One strand of this critique focuses on expatriate peacebuilders’ myopia about local, indigenous practices of peace and governance, arguing that peacebuilding should better resonate with the actual needs of the society emerging from conflict.Footnote 33 Overall, this most critical strand of the literature focuses on how international norms and objectives are externally imposed on a recipient country.

In sum, in theorizing about peacebuilding and studying its outcomes, analysts have tended to focus on the processes and institutional forms comprising the practice of peacebuilding. There are notable exceptions advancing the perspective that peacebuilding attempts can be improved only by better apprehending the political incentives of domestic elites – and emphasizing, contrary to the conventional assumption, that the strategic interests of international and domestic actors rarely coincide.Footnote 34 Yet the various strands of the peacebuilding literature tend overall to suffer from a short-term focus, a probabilistic or variable-centered logic, and an overemphasis on the institutional forms associated with peacebuilding. In order to truly understand whether peacebuilding approaches can and do achieve their objectives of building sustainable and lasting peace, it is necessary to explain longer-term governance outcomes by focusing on the causal and conjunctural mechanisms through which domestic elites interact with interventions and continue to build political order in their aftermath.

This book thus emphasizes how domestic post-conflict elites have been extremely adept at co-opting international peacebuilding interventions for their own political concerns and objectives. The approach of peacebuilding through transitional governance is not undertaken in a political vacuum even when formal institutional structures have collapsed. On the contrary, peacebuilding is a hyperpolitical undertaking; and the political–economic incentives facing domestic elites in the course of peacebuilding are crucial in explaining outcomes. Recognizing this issue in practice, the policy community on peacebuilding and development has recently converged on the broad consensus that the ability of an institution to deliver good governance – in the sense of producing public services and achieving legitimacy – is not simply a technocratic matter; instead, successful institution building is embedded in political processes, power structures, and societal sources of legitimacy.Footnote 35 The narrative presented in this book pays careful empirical attention to the elite incentives that define and condition their pursuit of political order. In particular, it examines how post-conflict elites garner political support and legitimacy, focusing on how they use political and administrative institutions to deliver the various benefits that underpin their compact with society.

Rethinking the Peacebuilding Puzzle

What explains the relative disappointment in the pursuit of effective and legitimate governance through peacebuilding interventions despite the tremendous financial, human, and intellectual resources devoted to this endeavor? The answer presented here rests upon two theoretical innovations that help to reframe the peacebuilding puzzle. Uniquely, I approach the study of peacebuilding through a temporal perspective, adopting a historical institutionalist lens. The book's causal narrative – as outlined briefly below – is structured around the pathway of three critical peacebuilding phases that form the course of international interventions: (1) the settlement phase, which marks an end to outright violent conflict; (2) the transitional governance period, over which a transformative peacebuilding intervention is implemented, in tandem with domestic elites, with the intent of creating a sustainable peace through statebuilding and democratization; and (3) the aftermath of the intervention and the pivot of a “post-conflict” country to a “normal development” phase. Emphasizing the temporal dimensions of political phenomena in this manner – viewing political processes “in time” as Paul Pierson coins it – can be essential to uncovering elements of the causal mechanisms at hand.Footnote 36 One crucial insight that emerges from the temporal causal picture presented here is that international peacebuilding efforts do not, contrary to their implicit logic and expressed goals, bring about a fundamental break with the political patterns of the past. Instead, we can only achieve a true understanding of the outcomes of peacebuilding when we see these efforts in temporal continuity. Over the course of the peacebuilding pathway that forms the narrative arc of this study, the manner in which domestic elites interact with an international peacebuilding intervention in shaping political order – unintended consequences and all – comes into sharp relief.

Intertwined with the historical institutionalist approach, this book imports a new political economy perspective to the study of peacebuilding. The study of intra-state conflict was revolutionized by an attention to the economic incentives that influenced the behavior of warring parties.Footnote 37 The study of how societies end and recover from conflict requires a similar emphasis on the political–economic motivations orienting the parties to peace. The vast majority of post-conflict countries are developing countries in which the central governance challenge is the construction of a viable modern political order conducive to economic productivity. Yet those who study post-conflict peacebuilding, typically rooted in the study of violent conflict and its resolution through peacekeeping and institutional engineering, have paid scant attention to the study of the political economy of development – which is focused on how institutions and resources shape elite incentives, the state–society compact, political order, and economic development. We cannot fully explain post-conflict governance outcomes unless we understand the incentives motivating elites as they attempt to construct political order and see how the choices of these actors are conditioned by context – features that come into sharp relief over the course of the peacebuilding pathway.

The empirical chapters in this book advance the following causal argument through a comparative analysis of UN peacebuilding experiences and post-intervention outcomes in three countries: Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan. First, I examine how warring elites come to a peace settlement in the context of the grievances and competing claims to governing legitimacy that contributed to conflict in the first place. Mediating a peace settlement is the first step taken by the international community in an attempt at transformative peacebuilding – and, in turn, serves as the basic agreement upon which the rest of the peacebuilding intervention is then predicated and implemented. Previous scholarship has emphasized that the settlement phase of peacebuilding is best understood as a conditional elite pact, yet the literature typically views and assesses these peace settlements in the limited context of marking an end to violence. A post-conflict settlement deal should, more importantly, be interpreted as a critical juncture marked by exceptionally fluid politics that, in turn, initiates a new pathway featuring heightened elite conflict in the political arena. The way elite settlements are typically pursued has the perverse effect of freezing in place an unstable equilibrium of power; this makes it more likely for elites to perceive the immediate post-conflict period as a “winner takes all” game with short time horizons. A sharper understanding of elite political contest leading into and coming out of the conflict becomes central to understanding how domestic elites embarked, in tandem with the international community, on reshaping post-conflict political order.

Second, I demonstrate how the simultaneous state- and democracy-building approach pursued by the archetypal transformative peacebuilding intervention empowers particular domestic elites to capture the legitimate political space and concentrate state resources in their own hands. In order to quickly establish basic state functions, the international community chooses specific elites with whom to govern, undermining the creation of a level political playing field to promote democratization. The new political pathway initiated by the peace settlement thus locks in advantages to a small group of elites. In turn, a self-reinforcing dynamic is established whereby these early winners continue to gain benefits in a manner that leads to a permanent reshaping of the power balance. Peacebuilding interventions themselves deliver sources of patronage to these specific political actors in the form of financial and other resources and the conferral of legitimate power. Perhaps most crucially, these elites are also centrally involved in the process of institutional engineering that takes place over the transitional governance period itself. Thus, over the course of an intervention and in the election that marks its endpoint, a small group of elites benefits from gradually increasing returns to power, while actively nurturing a political coalition and shaping institutions to their continued advantage.

Third, I explain how and why post-conflict countries tend to consolidate neopatrimonial political orders in the post-intervention phase. The UN's peacebuilding model rests on the liberal ideal that well-functioning, democratic states will deliver the public goods and services and shared prosperity that are pillars of sustainable peace. In reality, however, the political–economic incentives motivating post-conflict elites make it easier and more profitable for them to distribute public rents and patronage goods to their clients in exchange for political support. When time horizons are short and citizens cannot hold elites accountable for their commitments to provide public goods, elite incentives privilege narrow benefit provision to specific clients instead of public goods that benefit all citizens. Under these conditions, elites can channel their appeal to citizens through hierarchical patron–client networks. The formal structures of authority – such as government agencies and institutionalized political parties – are undermined, in turn, because elites do not need to build credibility with the broader populace. The patterns of political contestation evidence an inter-elite battle to gain political authority, as well as the struggle to use political power to continue to reinforce advantage.Footnote 38 This neopatrimonial political–economic order is an obviously suboptimal one that privileges the short-term interests of elites and their networks over the long-term welfare of society at large. Even as a return to violent conflict is forestalled, genuine improvements in state capacity and democratization prove to be illusory.

Rethinking the peacebuilding experiences in Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan through the lens of this narrative demonstrates the contest between two competing visions – international and domestic – of political order. Quite simply, during the course of transitional governance powerful domestic elites co-opt the UN-led process of institutional design, which is intended to serve as the basis for lasting peace, and subsequently consolidate their holds on power through various discernible strategies, damaging the prospects for democratic governance. Peacebuilding operations bring with them significant resources and, in turn, the allocation and control of those resources become a new site of power for elites.Footnote 39 In Cambodia today, the hegemonic ruling party quashes dissent and controls all the levers of administrative, economic, and political power in a situation of grand state capture. In East Timor, a nascent peace was upended by continuing elite factional battles that turned violent and the subsequent political–economic settlement remains contentious. In Afghanistan, competing elites maintain a pitched battle for control of the state and the country's resources – a struggle framed by the political dominance of ethnoregional patron–client networks. In subtly different ways, each country's trajectory reveals how elites faced a political–economic calculus that oriented their incentives toward the construction of a neopatrimonial political order characterized by discretionary rule-making, weak state capacity, and compromised democratic accountability.

Viewed in time and with the role and incentives of post-conflict elites firmly in mind, it becomes evident that the international peacebuilding endeavor paradoxically fails at achieving its goal of sustainable peace through state- and democracy-building because these elites instead succeed at using the peacebuilding intervention for their own ends. I wish to be clear at the outset that those ends are not unquestionably negative. In each of the three cases in this book – as well as in other countries – the post-intervention political order is undoubtedly better than the conflict that preceded it, with elements of more political stability, government efficacy, and democratic accountability. But these outcomes fall short of what the international community believed itself capable of achieving. The contention here is that viewing post-conflict peacebuilding interventions as sequenced contests between two competing visions of political order explains why the desired results of the transformative peacebuilding enterprise are not fully met as well as the outcomes we see in place. Next, I discuss how I construct this argument.

A Unique Approach to Understanding Peacebuilding

This study hews to the three defining features of comparative-historical analysis identified by James Mahoney and Kathleen Thelen and their collaborators in their recent, thorough, and eloquent case for the approachFootnote 40 – which has often, until relatively recently, also been referred to as historical institutionalism. First, this book adopts a firmly macroscopic orientation to the study of peacebuilding, focusing on large-scale political outcomes and causal patterns, along with a configurational logic, whereby the mode of explanation emphasizes variables combining in patterns defined by context. Second, the study was inspired by a desire to focus on problem-driven, case-based research, geared toward the explication of causal mechanisms through deep understanding and retelling of case empirics as opposed to a stylized rendering of cases coded on isolated variables of interest. Third, the analysis in this book presents a temporal emphasis, whereby the timing and sequencing of when specific things occur matter a great deal to the way that outcomes play out, as much as any other element of context.

I have chosen to define this book's analytical logic as resting on a foundation of historical institutionalism even though “comparative-historical analysis” has perhaps become the dominant label for this approach in the political science scholarship. This choice reflects the wish to emphasize the metatheoretical reframing that the historical institutionalist approach affords the study of peacebuilding, especially through its temporal and configurational causal logic, over other, more granular methodological concerns being addressed by those in the vanguard of comparative-historical analysis.Footnote 41 This section thus makes a particular case for a temporal understanding of peacebuilding, characterizing the international community's model of peacebuilding through transitional governance as a critical juncture and emphasizing the value of a path-dependent approach to the study of this transformational experience. It then specifies the macropolitical and institutional variables that are of interest in the study and discusses the configurational mode of explanation. Finally, it explains the selection of the Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan cases and outlines the case-intensive empirical research design underpinning the study.

Viewing Peacebuilding in Time

One of the central aims of this book is to make an original contribution to the study of peacebuilding by grounding it “in time.”Footnote 42 To deepen our understanding of peacebuilding and political order in post-conflict states, this book emphasizes the importance of temporal causal sequences and mechanisms and views institutions – formal rules, policy structures, and norms – as both the legacies of the concrete political struggles of the past and the contours of the political arena of the present.Footnote 43 In this light, the temporal location of peacebuilding interventions is crucial, in relation both to the conflict and political landscape that precedes them and also to their aftermath and the political dynamics and outcomes they set in motion. The analysis here is thus differentiated from the more common approach to the study of peacebuilding, which favors a probabilistic logic and typically treats interventions as exogenous treatments to be assessed in terms of the extent to which they met their objectives. Adopting an in time approach helps to expand our conjunctural and contingent understanding of where institutional change comes from, opening it up to endogenous change shaped by the interaction of specific actors, and avoids the risk of an improperly truncated analysis.Footnote 44

This book embeds the abrupt transformational experience represented by a peacebuilding intervention in a longer view of the gradual building of political order. In so doing, it recognizes that as consequential for political outcomes as the critical junctures at which wholesale change occurs is the slow and piecemeal adaptation in and around institutions that follows.Footnote 45 The rich literature on state formation and the building of political and institutional order has taught us that the sequencing of political and institutional choices and processes is central to explaining outcomes.Footnote 46 In particular, causal conjunctures – the interaction effects between causal sequences – are especially important for understanding the effects of competition over political space.Footnote 47 Institutions, in the narrative I build in this book, are both an outcome of interest and important intervening variables in generating other outcomes – they emerge from temporal processes of political struggle and are deeply embedded in social context, shaping both going forward. In short, institutions – including those that are at the heart of peacebuilding interventions – are the path-dependent products of both continuity and change.Footnote 48 When we view peacebuilding efforts in temporal perspective it becomes clear that the formal institutions they transplant into post-conflict states interact with the patterns of the past instead of serving as a break with them.

A peacebuilding intervention is a transformative moment from its inception (via peace settlement and UN mandate) through to its close (exit via elections), encompassing its implementation on the ground through transitional governance. A peacebuilding operation of this nature is thus fruitfully treated as a watershed event that, like a classic critical juncture, “establish[es] certain directions of change and foreclose[s] others in a way that shapes politics for years to come.”Footnote 49 Such an intervention, like a critical juncture, can be seen as both a structural phenomenon that reshapes the polities in which it is undertaken, as well as a moment of contingent choice for the agents involved in the transformation.Footnote 50 Indeed, Giovanni Capoccia notes that the defining feature of a critical juncture is contingency – because of the uncertainty as to what institutional arrangements will come to look like, “political agency and choice…play a decisive causal role in setting an institution on a certain path of development, a path that then persists over a long period of time.”Footnote 51 What makes a peacebuilding intervention a particularly interesting type of critical juncture is that it represents a series of wide-ranging institutional choices superimposed by an external actor upon the fluid political landscape of a post-conflict country.

Peacebuilding Outcomes: Institutions and Governance

The transformative aspirations of the broader peacebuilding project are represented in the belief that the international community can, in a relatively short period of time, establish the institutional underpinnings for rule-bound, effective, and legitimate government. Animated by the objective of building the foundations for lasting peace, international interventions focus operationally on the construction of the formal institutional structures of the administrative and political arenas. Yet those institutional structures are transposed onto dynamic political contexts, hence eventual governance outcomes are a product of the domestic political game. The results of peacebuilding interventions are decidedly mixed, therefore, with a notable gap between the formal institutions transplanted through transitional governance and the eventual governance outcomes in the aftermath of intervention. Open contestation around formal institutional choice is only the tip of the iceberg in terms of the real power battles that are going on under the surface – such that the politics of initial institutional adoption are often very different from the politics of later implementation and adaptation.Footnote 52 Thus, I examine two sets of outcomes: the formal institutional choices surrounding statebuilding and democratization; and the extent to which effective and legitimate governance are consolidated in the post-intervention phase.

Formal Institutional Choices

In undertaking peacebuilding that aims to resolve the roots of conflict, the international community has come to believe that a political solution to stalemated civil conflict cannot be “all or nothing,” and that institutional design is the major policy instrument available for reconciling previously warring segments of a population. With the eventual aim of building a stable and lasting peace by establishing the foundations for democratic governance, two sets of institutional structures are emphasized in peacebuilding through transitional governance: administrative structures – the set of institutions through which a government exerts control or broadcasts authority over its population; and constitutional arrangements – the set of institutions through which a governing authority administers a polity with legitimacy. Agreement on the institutional architecture of the modern state – including an administrative structure, a constitution, and the design of an electoral system – represents the outcome of crucial political negotiations among domestic elites, as well as a critical step in the longer process of building rule-bound, legitimate, and effective government.

Post-Intervention Governance Outcomes

Transformative peacebuilding focuses, in the peace settlement and transitional governance implementation phases, on the construction of the administrative and political institutions discussed above. Its objectives, however, are to resolve the roots of conflict and thereby build a stable peace. The degree to which those institutions are the channel through which effective and legitimate governance is built and thereby serve as a stepping stone to sustainable peace can only be assessed by looking at consolidated governance outcomes in terms of state capacity and democratization. We know a strong state and its hallmarks when we see them in action. The Weberian ideal state is one that is effective, resting in turn on the autonomy and internal organization or rationalization of the bureaucracy.Footnote 53 The state is also in constant interaction with society, both shaping and being shaped by it.Footnote 54 Theda Skocpol thus argues that analysis of the state should also include the “Tocquevillian” dimension of state strength that emphasizes the state's connections with society.Footnote 55 Peter Evans captures this two-sided conception of strong state capacity with the notion of embedded autonomy, a term that echoes Michael Mann's distinction between “extensive” and “intensive” power.Footnote 56 The widely used working definition of a consolidated democracy developed by Juan Linz and Alfred Stepan captures the notion of democratization in a similarly inductive manner. Briefly, a democratic regime is consolidated behaviorally, when no significant actors attempt to create a nondemocratic regime or turn to violence; attitudinally, when a strong majority of the public believes that democratic procedures and institutions are the best way to govern their collective life; and constitutionally, when governmental and nongovernmental forces alike are habituated to conflict resolution within the laws, procedures, and institutions laid out by the new democratic process. In short, consolidated democracy is a political situation in which democracy has become “the only game in town.”Footnote 57

It is worth noting here that the criteria outlined above – especially the latter set, concerning the consolidation of effective and legitimate governance – constitute a higher bar than most analysts of peacebuilding have adopted in assessing its outcomes. Most scholars and practitioners, while acknowledging that the situation often deteriorates as time elapses, have judged the success of UN peace operations mainly by assessing the degree to which peace obtained at the point the UN exited the country or a few short years later. There are good reasons for the adoption of this conventional approach. Some have pleaded that not enough time has elapsed to realistically analyze consolidation. Others claim that state- and democracy-building are, by their very nature, extremely difficult and time-consuming processes, and thus assessments of consolidation are based on unreasonably high standards of peacebuilding success that cannot properly be attributed to the implementation of the peace operation itself.Footnote 58 These are certainly complex and lengthy processes and evaluating proximate cause is indeed methodologically difficult.Footnote 59 Yet assessing the outcomes of peacebuilding operations in achieving their own objectives means examining critically what happens after peacebuilders leave the country in addition to understanding what they did while they were there. Fortunately, an assessment of longer-term peacebuilding records has now become possible as more time has elapsed since the close of the UN transitional governance missions considered here. Lengthening our perspective in this manner – alongside a macroscopic and conjunctural perspective, in contrast to a more probabilistic and evaluative logic – enables a critical assessment of the international community's assumption that a transformative process of elite peace settlement followed by simultaneous state- and democracy-building will achieve sustainable peace.

Case Selection

Transitional governance interventions are rare events. To recap, these are the transformative operations in which the UN pursues lasting peace through a strategy of simultaneous statebuilding and democratization, enacted via the implementation mechanism of shared international and domestic governance over a transitional period that begins with a peace settlement and ends with a first post-conflict election. In common with most scholars in this area, I focus on the UN as the major actor undertaking and coordinating international peacebuilding interventions. Moreover, UN transitional governance serves implicitly, due to its multidimensional and transformative nature, as an umbrella rubric for the post-conflict activities of other global actors – including international financial organizations, bilateral development agencies, and international nongovernmental organizations. Since 1948 the UN has mounted a total of 70 peace operations, 55 of which have taken place since the end of the Cold War in 32 different countries, with a number of countries having hosted multiple operations.Footnote 60 Christoph Zürcher et al. classify 19 of these as major peacebuilding operations – they meet this definition if they lasted over 6 months, comprised more than 500 personnel, and were intended to maintain peace at least in part by facilitating socio-political change.Footnote 61 Of these 19, only 6 meet the criteria established here for transitional governance: these are, in chronological order, Cambodia, Bosnia, Croatia, Kosovo, East Timor, and Afghanistan.Footnote 62

This book focuses on the transitional governance interventions that were deployed by the UN in Cambodia (1991–1993), East Timor (1999–2002), and Afghanistan (2002–2005). Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan are the only three developing countries with weak institutional capacity in which the transitional governance approach has been implemented. The analysis in this book does not includes the three remaining instances of transitional governance peacebuilding – Bosnia, Croatia (Eastern Slavonia), and Kosovo.Footnote 63 All of these countries are more wealthy and institutionally advanced than the three developing nations I consider here – nevertheless, the transitional governance strategy itself remains similar in these cases, which should thus provide an opportunity for the further testing of the findings of this book. I also do not systematically examine major peacebuilding operations that do not meet the definition of transitional governance because they were not governed in tandem with the UN through a civil administration component to the peace operation, even if they encompassed UN-run elections and some elements of statebuilding. These cases would include, chronologically, Namibia, Mozambique, Haiti, Rwanda, Tajikistan, Angola, Macedonia, the Central African Republic, Sierra Leone, the Democratic Republic of the Congo, Liberia, Côte d'Ivoire, Burundi, South Sudan, and Mali.Footnote 64

The lack of an African transitional governance case is analytically unfortunate for this book, since Africa is the region where by far the most peacebuilding occurs.Footnote 65 Namibia was the first country in which a major peacebuilding operation was undertaken and some would consider it the first case of transitional governance. Per my reading of the intervention's mandate, however, the United Nations Transition Assistance Group (UNTAG, 1989–1990) in Namibia does not meet the definition of a transitional governance mission advanced here because it did not comprise a civil administration component responsible for a broad scope of governance functions. UNTAG did, in practice, take on some executive governance roles, but the range of those functions was relatively circumscribed, at best qualifying the intervention as a proto version of the more full-blown transitional governance interventions that were mandated soon after.Footnote 66 The two most recent major peace operations, in South Sudan (2011–present) and Mali (2013–present), are similarly multidimensional in scope and transformative in ambition, but with circumscribed governance functions for the UN in terms of implementation. Nevertheless, the empirical chapters below incorporate, where possible, conclusions from published research on major African peacebuilding operations that shed some light on the theoretical generalizability and empirical validity of the arguments advanced here.

Peacebuilding through transitional governance is uncommon. It does not occur very often in part because of what it entails – big, expensive, ambitious operations in countries where civil war has contributed to the disintegration of governance. To date, the East Timor intervention represents the high-water mark of the approach – and it is entirely possible that the peacebuilding ground has shifted enough over the decade since it concluded that we will no longer see such transitional governance attempts. Yet it is precisely the ambitious nature of these instances of transformative peacebuilding – and the contemporary international aspirations they represent – that makes them an important object of study.Footnote 67 This book's argument and implications will remain relevant even as the precise manner in which the international community's transformative peacebuilding endeavor is pursued continues to evolve.

Research Design

The research design underpinning this book is a comparative case study approach that traces the process of how transformative peacebuilding interventions in Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan led to a series of unintended political–economic consequences that shaped post-intervention governance outcomes. I present the argument thematically, instead of in case-narrative format, delivering a structured, focused comparison of the three cases at three critical peacebuilding phases – peace settlement, transitional governance, and the aftermath of intervention. The analytical strategy for doing so echoes Charles Call's insight that the transition from warfare to peace, in general, goes through a series of temporal junctures or critical moments, at which typical clusters of decisions arise.Footnote 68 Peacebuilding disappointments in post-conflict states are overdetermined; the odds are stacked against success and numerous causal pathways can be identified in leading to failure. But a robust comparative methodological approach that also relies upon process-tracing can be used to identify a plausible causal chain. Employed together, a controlled comparison and process-tracing offer a “middle ground” approach between heavily ideographic descriptions of particular cases and overstylized cross-case comparisons that lose granular texture.Footnote 69

My purpose is to assess the merits of the international community's approach to post-conflict intervention through a critical analysis of the process it applies in interaction with domestic elites in attempting to achieve its stated outcomes. This purpose forms the basis of the structured, focused methodology employed to examine the cases. The logic of the method is straightforward: the empirical research was guided by a series of questions asked of each case intended to collect evidence on the outcomes of interest and potential causal patterns. In turn, this makes possible both systematic comparison across cases and cumulative conclusions.Footnote 70 Within-case analysis through process-tracing helps to strengthen the argument that, rather than the pre-existing conditions in each case, it was the interaction between the international intervention and domestic elite incentives that led to the observed outcomes. The approach underpinning this study is particularly well suited to generating new hypotheses about understudied phenomena, carrying out contextualized comparison, and dealing with causal complexity. Like many historical institutionalist works, the approach here begins with a specific empirical puzzle in a limited number of cases sharing a unified political experience and focuses on developing mid-range theory on the topic.Footnote 71

The case-comparative approach grounded in historical institutionalism is sometimes regarded as being difficult to falsify. Although this is not inherently true, the criticism may apply to a specific empirical investigation – hence it is worth being explicit about what could falsify my argument. In short, empirical inklings that domestic elite incentives and actions are not truly path dependent, or linked temporally, would prove the argument wrong. Evidence that would support a more rationalist and probabilistic logic, for example, would be signs that domestic elites were repeating rounds of interaction among themselves or with the international intervention with little impact from the outcomes of previous rounds; or that powerful actors were able to impose their instrumental designs on institutions such that their preferred functions were achieved quite perfectly. My analysis of the evidence from the cases, as presented in the empirical chapters, instead supports the conjunctural, path-dependent logic that allows for, among other things, explanations for the high level of institutional ambiguity and mismatch seen in the cases. Moreover, any limitations of the approach adopted here with regards to Popperian falsifiability are, I believe, outweighed by the benefits of a problem-driven, case-oriented approach that is geared toward generating a theoretically informed causal account of the peacebuilding outcomes across these three cases.Footnote 72

Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan display a substantial degree of variance in pre-intervention pathways, in terms of their trajectories into conflict and the nature of the peace settlement that ended conflict. The three countries thus serve as a set of “most different systems” cases in terms of many potential explanatory variables, including: the nature of the conflict; the configuration of competing groups and elites that engaged in conflict and came to a peace settlement; and the nature of sociopolitical cleavages and macrohistorical context. In Cambodia, three major coherent factions opposed to each other on ideological grounds fought a 21-year civil war against the backdrop of Cold War geopolitics and a genocidal regime. The peace settlement of 1991 was the result of a mutually hurting stalemate between still hostile groups. In East Timor, the settlement marking the end of a 24-year resistance struggle against Indonesian occupation was the independence vote in 1999. The revolutionary front served as an umbrella group that, albeit quite incoherent, dominated the political landscape in the transitional phase. Afghanistan emerged in 2001 from 22 years of conflict that saw an anti-imperialist struggle morph into civil war among many fairly coherent ethno-tribal groupings. A peace agreement was struck among a coalition that had come together, aided in the end by the US military, to defeat the Taliban – but political, financial, and armed resources in the country continued to be spread widely across still hostile groups.

Despite the many differences between the cases, each country underwent the transformative critical juncture of a peacebuilding intervention through transitional governance. My argument here thus emerges from the method of agreement:Footnote 73 the shared transformational experience that all three countries went through is the transitional governance process – hence any similarities in outcomes that result from that process should be more compelling given their differences. While the comparative case material presented here generates a causal logic, it cannot rigorously demonstrate the external validity of that logic.Footnote 74 The theory-building research objective here is a heuristic, building-block approach that seeks to inductively identify causal patterns to better understand peacebuilding.Footnote 75 As discussed above, the transitional governance approach is one type of broader peacekeeping and peacebuilding intervention. The scope of the research here is necessarily limited; nevertheless, the analysis I develop in this book fills a gap in and contributes to the more general theory of peacebuilding being developed by scholars and practitioners today. In addition, this book generates a theory of the politics of international intervention and its interaction with domestic elite incentives that is generalizable beyond the issue of peacebuilding.

My analysis rests on the approximately one hundred personal interviews I conducted from 2002–2014 in Cambodia, East Timor, and Afghanistan, as well as in Canberra, London, New York, and Washington, DC.Footnote 76 Each interview lasted between one and two hours and was conducted on a semi-structured basis using an interview guide adapted for each country or for other specific purposes. Interviewees were identified using snowball sampling – i.e., a nonrepresentative chain of referrals – and included legislators, government officials, national- and provincial-level civil servants, journalists, civil society and private sector representatives, scholars, natural resource sector experts, and officials representing international organizations, bilateral development agencies, and international nongovernmental organizations. Almost all of my interviewees requested that they not be quoted directly and that they not be identified in relation to specific responses. In the text below interviewees are therefore identified only by their general role in relation to certain findings; the appendix to this book provides a full list of all interviews. The analysis also draws upon the rich case study evidence available in published work and policy reports on international peacebuilding interventions.

The research was organized as a series of questions that map to the three critical phases along the peacebuilding pathway, around which sequence this book is structured: the peace settlement phase; the transitional governance period; and the aftermath of intervention. It is during these critical moments marking the course of an intervention that the dynamics of interaction between the international community and domestic elites are thrown into sharp relief – and political and administrative institutions serve as a crucial arena in which these interactions play out. The following chapter establishes the theoretical framework that orients the study, presenting it in terms of the peacebuilding pathway.