1. Introduction

The creative design process has been a subject of high interest for diverse fields, including engineering, design, management, and product development, by fostering innovation across these areas. The significance of creativity is not limited to innovation, but it is also an essential driving force in problem-solving. Throughout the broad literature on creativity, many definitions for creativity have been formulated (Runco et al. Reference Runco, Millar, Acar and Cramond2010), expressing creativity as “fluency, flexibility, originality and elaboration of ideas.” Core components of creativity are characterised by the outcome of products that are novel and useful (Sternberg Reference Sternberg1999; Sarkar & Chakrabarti Reference Sarkar and Chakrabarti2011). In the design ideation process, creative thinking is essential for exploring the design concept space and promoting flexible thinking, with analogical reasoning playing a crucial role in expanding the solution space and drawing cross-domain inspirations (Jia et al. Reference Jia, Becattini, Cascini and Tan2020). In recent years, there have been significant advancements in Design-by-Analogy (DbA) methodologies and support tools, where traditional approaches like biomimetics, TRIZ, and Synectics are integrated with state-of-the-art computational tools leveraging Generative AI – Large Language Model (LLM) and Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Hu, Wood and Luo2022). LLMs have brought a significant evolution in co-creative systems with dynamic idea-generation and problem-solving capabilities across diverse domains such as concept generation (Ren, Ma, & Luo Reference Ren, Ma and Luo2025), (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Song, Guo, Sun, Childs and Yin2025), management and innovation (Bouschery, Blazevic, & Piller Reference Bouschery, Blazevic and Piller2023; Meincke et al. Reference Meincke, Girotra, Nave, Terwiesch and Ulrich2024), and the ideation process (Tholander & Jonsson Reference Tholander and Jonsson2023), highlighting their potential in augmenting the creativity process. The motivation for leveraging LLMs in analogy-based ideation processes stems from their potential to address human limitations, such as accessing far-field knowledge and enhancing analogical reasoning capabilities (Webb, Holyoak, & Lu Reference Webb, Holyoak and Lu2023; Jiang & Luo Reference Jiang and Luo2024). A limited number of studies have explored the analogical capabilities of LLMs in the context of scientific and creative tasks (Bhavya, Xiong, & Zhai Reference Bhavya, Xiong and Zhai2022; Ding et al. Reference Ding, Srinivasan, MacNeil and Chan2023); however, they highlight the need for empirical quantitative insights into concepts generated by LLMs’ assistance and the benchmarked evaluations of LLM-generated content in analogical reasoning tasks. Recent research indicates that the creativity and reasoning patterns in LLM-generated output are primarily dependent on the training data, having limited empirical evidence on the language model’s performance in analogical and creative tasks (Shojaee et al. Reference Shojaee, Mirzadeh, Alizadeh, Horton, Bengio and Farajtabar2025). Existing evaluation methods in reasoning models also need to be investigated, highlighting their fundamental inability to achieve generalizable real-world problem-solving capabilities. The performance of these models in creative tasks is often ambiguous and poorly studied. Without comprehensive evaluation and creativity benchmarks, there is difficulty in assessing the model’s strengths and weaknesses, which are crucial in developing reliable support systems. Furthermore, studying human–AI collaboration of the support tools is equally important in the design ideation process, as the collaboration style, initiative, turn-taking patterns, and communication styles directly impact co-creative outcomes (Rezwana & Maher Reference Rezwana and Maher2023). Studies on interaction patterns (Oh et al. Reference Oh, Song, Choi, Kim, Lee and Suh2018; Tholander & Jonsson Reference Tholander and Jonsson2023) highlight the need for bidirectional communication and integration of multiple modalities in design support tools as LLMs often lack contextual understanding of human knowledge and level of experience. Combining the generative power of LLMs with external knowledge, design patterns and human expertise may provide the relevant contextual understanding of the problem at hand and enhance the outcome of the creative process (Ding et al. Reference Ding, Srinivasan, MacNeil and Chan2023). In our study, we propose a conceptual design framework leveraging the generative capabilities of LLMs with analogical and dialectical thinking models for concept generation. We further leverage this framework in a design support tool – Analogical LLM Ideation Agent (ALIA) – to facilitate co-creative ideation sessions between human designers and LLMs (Kokate, Kompella, & Onkar Reference Kokate, Kompella, Onkar, Chakrabarti, Singh, Onkar and Shahid2025). We conducted controlled experiments with 24 novice designers to evaluate the framework’s effectiveness in ideation sessions. Expert evaluation of the concepts generated in the experiments revealed that the groups assisted by ALIA generated significantly higher-rated novel ideas than baseline groups, suggesting the positive impact of LLM-assisted analogical reasoning. The study further dives deeper to examine the creativity of LLMs by introducing the Analogy Creativity Task (ACT), designed to benchmark model performance across various creative dimensions. Our findings reveal notable variations in the creative capabilities of LLMs, which differ in characteristics, providing practical insights that are helpful for language model benchmarking in creative tasks. The contributions from these experiments form the foundation for our study’s objectives, focusing on a systematic assessment and analysis of creative output.

2. Objectives

This study examines the role of Generative AI, specifically LLMs, in creative analogical ideation within a design context. The research addresses the following objectives: (i) To investigate how synectics ideation and dialectical methods can be integrated with LLMs to generate analogical stimuli for ideation. (ii) To develop a co-creative analogical ideation framework assisting human–AI collaboration in ideation sessions and assess the impact of a support tool based on the framework. (iii) To examine how different LLMs varying in architecture and training data influence creativity dimensions when prompted with synectics trigger analogies. (iv) To identify the role of human–AI interaction paradigms – turn-taking, intervention strategies and initiatives to design co-creative support tools effectively.

2.1. Significance

This work will contribute towards AI-assisted ideation, human-AI collaboration and the broader field of computational creativity in learning environments. Through this study, we (i) evaluated the role of LLM-generated content in cross-domain analogical reasoning, where future studies can leverage the insights for building relevant creative support tools across problem-solving tasks; (ii) proposed a framework that will encourage leveraging creative and critical thinking patterns in the computational learning process, promoting AI-literacy; and (iii) identified a gap in standard benchmarking and evaluation methods for LLM-generated content’s creative performance and have proposed a benchmarking method for analogical creativity tasks.

3. Literature review

3.1. Creativity with analogy and dialectics

The creative design process has been a subject of high interest for the design community. Prior research has extensively explored and contributed to the broader field of design creativity, its crucial role in fostering innovation and enhancing problem-solving capabilities. Studies on creativity (Finke, Ward, & Smith Reference Finke, Ward and Smith1996) have often proposed analogical thinking as one of the crucial components that encourage transferring information from a familiar domain to a seemingly new and unfamiliar domain for the construction of new ideas. In a problem-solving task where analogical thinking is utilised, people first access the existing information in a known domain and then map the similarities between the source and target domains. Analogies in design ideation play a crucial role in facilitating creative thinking and expanding the potential solution space (Jia et al. Reference Jia, Becattini, Cascini and Tan2020). Research in analogical thinking and innovative design (Dahl & Moreau Reference Dahl and Moreau2002; Chan et al. Reference Chan, Fu, Schunn, Cagan, Wood and Kotovsky2011) has emphasised the effectiveness of cross-domain analogies in facilitating creative output and producing high-quality concepts. Design-by Analogy (DbA) methodology has proven to benefit designers by reducing design fixation and improving ideation by generating novel ideas (Moreno et al. Reference Moreno, Hernández, Yang, Otto, Hölttä-Otto, Linsey, Wood and Linden2014a, Reference Moreno, Yang, Blessing and Wood2014b). By transferring a design problem (source) to a solution (target) in a distant domain, DbA promotes exploration of space and semantically distant concepts (Finke et al. Reference Finke, Ward and Smith1996). Researchers have highlighted the importance of analogical thinking in new product development and innovation (Goel Reference Goel1997) and usage of functional and form analogies for creative tasks (Sarlemijn & Kroes Reference Sarlemijn and Kroes1988). The synectics approach for ideation makes use of personal, symbolic, fantasy and direct analogies to tap the psychological states and promote creative activity in problem identification and problem-solving tasks (Gordon Reference Gordon1961). A philosophical construct, Hegelian dialectics, uses a contradiction-conflict-resolution mechanism to resolve the tension between contradictory elements, leading to a creative outcome. The construct involves three stages: a thesis states a factual statement; the antithesis states a contrasting fact to the given statement; and the synthesis combines the thesis and antithesis to propel the discussion forwards. The implications of dialectical thinking on creativity (Ward Reference Ward1995; Rothenberg Reference Rothenberg1996) reported that such resolution of contradictory statements often leads to surprise. Correlation between dialectical thinking and problem-finding (Arlin Reference Arlin1989) suggested that eventually, by enabling deeper examination of the problem through dialectical thinking leads to better creativity. Synectics and dialectics employ convergent and divergent thinking phases to generate novel and often unexpected insights. The interactive capabilities of LLMs can effectively leverage these iterative and multi-turn structures. Limited empirical work examines how these structured ideation models can be leveraged in an LLM-assisted design ideation process, which this study aims to investigate.

3.2. Design ideation with LLMs

LLMs have been an interesting and transformational development in Artificial Intelligence, with a visible impact on the general population. Various DbA methods have been utilised for concept generation – Biomemetics (Hacco & Shu Reference Hacco and Shu2002), IdeaInspire (Siddharth & Chakrabarti Reference Siddharth and Chakrabarti2018), Wikilink (Zuo et al., Reference Zuo, Jing, Song, Sun, Childs and Chen2022) – exhibiting a positive contribution to analogical reasoning. Furthermore, usage of emerging technologies like Generative Pre-trained Transformers (GPT), Graph Neural Network (GNN) and Generative Adversarial Networks (GANs) has been proposed to enhance analogical reasoning in creative design contexts (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Hu, Wood and Luo2022). Cross-domain LLM-generated analogies for problem reformulation are helpful in creative tasks (Ding et al. Reference Ding, Srinivasan, MacNeil and Chan2023), highlighting the importance of prompt engineering and carefully curated prompts. LLMs possess an emergent capability for analogical reasoning with zero-shot prompts by using a source analogy to solve a target problem (Webb et al. Reference Webb, Holyoak and Lu2023). The effectiveness of LLMs’ reasoning capabilities has been demonstrated by automating the TRIZ methodology for design ideation (Jiang & Luo Reference Jiang and Luo2024), showing potential to include other DbA methods like SCAMPER, WordTree, Synectics, and so forth. Investigating the creative role of LLMs (Franceschelli & Musolesi Reference Franceschelli and Musolesi2024) pointed out the probabilistic and autoregressive nature of LLMs as one of the reasons preventing them from reaching transformational creativity. Motivation, intention and thinking are some of the crucial intrinsic parts of a creative process (Amabile & Mueller Reference Amabile and Mueller2024; Collins Reference Collins2025). Current research shows that LLMs inherently do not possess these faculties, differentiating their output content generation from traditional creative activity. Although extensive work exists in LLM-assisted design ideation in studies by Bouschery et al. (Reference Bouschery, Blazevic and Piller2023); Ding et al. (Reference Ding, Srinivasan, MacNeil and Chan2023) and Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Song, Guo, Sun, Childs and Yin2025), there is a lack of systematic quantitative evaluation of LLM-generated outputs for creativity dimensions such as novelty, quality and usefulness. This has been addressed to some extent by a few studies – qualitative analysis of how designers use LLMs in co-creative workshops (Tholander & Jonsson Reference Tholander and Jonsson2023); empirical evaluation and comparison of LLMs against human students (Meincke et al. Reference Meincke, Girotra, Nave, Terwiesch and Ulrich2024); and evaluation of interface on human’s ideation output (Duan et al. Reference Duan, Karthik, Shi, Jain, Yang and Ramani2024), which lacks the isolated evaluation analogical content. A limited number of studies have investigated the analogical capabilities of LLMs in the context of creative tasks. For instance, LLMs can generate cross-domain analogies in ideation (Ding et al. Reference Ding, Srinivasan, MacNeil and Chan2023); however, the evaluation was conducted by a single PhD researcher and the interaction with the model was in a static one-way format. The feasibility of analogy generation in scientific contexts (Bhavya et al. Reference Bhavya, Xiong and Zhai2022) lacked evaluation within ill-structured problem domains and also quantifiable creative metrics. Similarly, automation of the TRIZ methodology with LLMs lacked quantitative analysis of creative metrics (Jiang & Luo Reference Jiang and Luo2024). Popular newly launched models go through extensive LLM benchmarking tests to evaluate how well the model performs across different tasks, ranging from language skills and reasoning – HellaSwag (Zellers et al. Reference Zellers, Holtzman, Bisk, Farhadi and Choi2019), MMLU (Hendrycks et al. Reference Hendrycks, Burns, Basart, Zou, Mazeika, Song and Steinhardt2020), for mathematical tasks – GSM8K (Cobbe et al. Reference Cobbe, Kosaraju, Bavarian, Chen, Jun, Kaiser, Plappert, Tworek, Hilton, Nakano, Hesse and Schulman2021), MATH (Hendrycks et al. Reference Hendrycks, Burns, Kadavath, Arora, Basart, Tang, Song and Steinhardt2021) and MBPP (Austin et al. Reference Austin, Odena, Nye, Bosma, Michalewski, Dohan, Jiang, Cai, Terry, Le and Sutton2021) and for coding – HumanEval (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Tworek, Jun, Yuan, de Oliveira Pinto, Kaplan, Edwards, Burda, Joseph, Brockman, Ray, Puri, Krueger, Petrov, Khlaaf, Sastry, Mishkin, Chan, Gray, Ryder, Pavlov, Power, Kaiser, Bavarian, Winter, Tillet, Such, Cummings, Plappert, Chantzis, Barnes, Herbert-Voss, Guss, Nichol, Paino, Tezak, Tang, Babuschkin, Balaji, Jain, Saunders, Hesse, Carr, Leike, Achiam, Misra, Morikawa, Radford, Knight, Brundage, Murati, Mayer, Welinder, McGrew, Amodei, McCandlish, Sutskever and Zaremba2021). The performance of these models in creative tasks is often ambiguous and not well studied. Although various studies have explored the LLM-based ideation methodologies and tools, there remains a notable absence of empirical evidence on the analogical performance of LLMs and benchmarking in creative tasks, a gap that this study seeks to address.

3.3. Co-creativity support tools

Design support tools have been developed employing analogies to facilitate ideation and concept generation. There are few non-LLM computational creativity tools like the “Combinator” (Han et al. Reference Han, Shi, Chen and Childs2018), which combines unrelated ideas to produce textual and visual imagery prompts; the Generative Adversarial Network (GAN) for developing semantic ideation networks for visual and textual stimuli (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Wang, Dong, Shi, Han, Guo, Childs, Xiao and Wu2019); the WikiLink, an encyclopaedia-based semantic network for providing cross-domain resources for innovation; generation of patentable concepts with PatentGPT with evaluation on IP-related benchmarks (Ren et al. Reference Ren, Ma and Luo2025); and stimulus provided by nature and biological systems for concept generation with the searchable knowledge base tool, IdeaInspire 4.0 (Siddharth & Chakrabarti Reference Siddharth and Chakrabarti2018). At the core of all such tools are knowledge bases (KBs), which have a curated collection of data specific to an industry or field. As the KBs are confined to a specific domain, applying their information in cross-domain novel contexts is challenging, as novelty is one such crucial measure in any creative process. Knowledge updation and maintenance of the KBs need significant resources and time from domain experts (Siddharth & Chakrabarti Reference Siddharth and Chakrabarti2018), and combining several KBs is a complex task as there is no standard structure, terminologies and representation and so forth These limitations of KBs can hinder the general purpose and broader use-cases, especially in analogical ideation, where cross-domain knowledge has been shown to provide higher flexibility in ideas. LLM’s architecture, the training process on a massive corpus of data from the internet, and deeper semantic understanding of concepts allow it to create implicit connections across diverse domains, directly overcoming the limitations of static KBs. Support tools leveraging LLMs have been developed for concept generation. Visual knowledge graphs that are interfaces for designers to manage and visualise their design concepts (Duan et al. Reference Duan, Karthik, Shi, Jain, Yang and Ramani2024) have been developed; however, this study lacked the inclusion of analogical reasoning. AutoTRIZ (Jiang & Luo Reference Jiang and Luo2024) is guided by an internal fixed knowledge base of TRIZ parameters and principles in contrast to the open-ended ‘brainstorming’ approaches. Hence, our study aims to build upon the growing use of LLMs in concept-generation support tools and address the lack of quantitative practical implications of these tools in DbA ideation settings.

3.4. Human AI co-creativity

Co-creative systems foster collaboration among the multiple entities within the system to contribute to and drive the creative process across the various domains, including education, art, gaming and decision-making. The role of AI in co-creative systems enables humans to collaborate with an AI agent, which contributes to the process in a manner distinct from traditional co-creative systems. A review and analysis of 92 existing co-creative systems (Rezwana & Maher Reference Rezwana and Maher2023) highlighted the interaction design gap in communication between the human co-creators and the AI system. The study underscored the importance of collaboration style, initiative in shaping effective communication and positively contributing towards achieving higher levels of co-creativity. Most co-creative systems lacked bi-directional communication, turn-taking mechanisms and contextual adaptability. The need for iterative multi-turn interactions for complex tasks like creativity scenarios is discussed in a study of mapping the design space of interactions in text-generation activities (Ding et al. Reference Ding, Srinivasan, MacNeil and Chan2023), where they proposed the usage of multiple modalities in developing support tools, combining the generative power of LLMs with design patterns and external sources of knowledge. Initiative patterns and user experience of human–AI co-creation in a creative context study conducted by Oh et al. (Reference Oh, Song, Choi, Kim, Lee and Suh2018) found that participants want to lead the communication while delegating repetitive tasks to AI. Any unexpected, surprising contributions from the AI are positively received and often perceived as source of inspiration as long as they are contextually relevant and did not dominate the co-creative process. The structured drawing task-oriented approach of this study limited its ability to capture the open-ended, bi-directional communication dynamics essential in a creative context. A study on design ideation in AI (Tholander & Jonsson Reference Tholander and Jonsson2023) examined the influence of interaction paradigms on participants’ engagement in the ideation process, interaction dynamics and human–AI collaboration. When interacting with such generative machine learning systems, the users must understand how to articulate their queries to make the system respond in a way the users expect. However, this study also highlighted the lack of contextual sense of AI systems and the need to integrate modalities. Despite the growing number of studies exploring various interaction mediums within support tools, there remains a lack of empirical studies conducted on the turn-taking role between humans and AI in an analogy-driven co-creative session using multi-modal interactions.

4. Methodology

This section outlines the methodological steps conducted in the study and explains the following subsections in detail: (i) the research questions this study aims to address based on the major findings from the literature review; (ii) development of a creative support tool (ALIA) based on the proposed framework, (iii) systematic experimental evaluation – Analogical Creativity Task (ACT) of the analogies generated by different LLMs and comparison of their creative output; and (iv) experimental design including participant sampling, data collection and procedure.

4.1. Major findings from the literature

The major findings are: (i) In creative ideation, cross-domain analogies are important and positively contribute to creative breakthrough and high-quality concept generation (Dahl & Moreau Reference Dahl and Moreau2002; Chan et al. Reference Chan, Fu, Schunn, Cagan, Wood and Kotovsky2011; Jia et al. Reference Jia, Becattini, Cascini and Tan2020). (ii) Several analogical support tools developed make use of a KB, limiting their ability to produce information from a different and novel domain. Restricting the KB to a single domain can potentially limit the variety of possible analogies generated. (iii) The human cognitive mechanisms, like reasoning, empathy, motivation and evaluation, contribute towards shaping a fruitful creative design process. However, as AI systems rely on algorithmic processes for content generation rather than the mechanisms involved in the human creative process, there is a fundamental difference in output generation. (iv) Fewer studies exist that explore the role of LLMs for analogical creative design ideation, and there is a lack of methods for evaluation and benchmarking of language models in creativity tasks. (v) Bi-directional communication, explainability of AI suggestions and contextually aware cues can contribute to achieving higher levels of collaborative creativity (Rezwana & Maher Reference Rezwana and Maher2023).

4.2. Research questions

RQ1: How effective is the impact of LLM-generated synectic triggers and the dialectical thinking process on the novelty of ideas compared to those generated without any support tool?.

![]() $ {Ho}_1 $

: There is no significant difference between the novelty of ideas generated with and without the support tool.

$ {Ho}_1 $

: There is no significant difference between the novelty of ideas generated with and without the support tool.

![]() $ {Ha}_1 $

: The novelty of ideas generated using the synectic triggered support tool will be higher than those produced without any support tool. The introduction of a tool utilising synectic triggers can help expand the creative concept space of designers. Random inspirations and tangential thoughts can enhance creativity (Nolan Reference Nolan2003), and the usage of analogical thinking is highlighted for new product development and innovation (Goel Reference Goel1997). As synectics promote out-of-the-box thinking by making the familiar strange and the strange familiar, this process contributes to linking concepts that have a far-field conceptual distance, thereby increasing the likelihood of producing novel outcomes.

$ {Ha}_1 $

: The novelty of ideas generated using the synectic triggered support tool will be higher than those produced without any support tool. The introduction of a tool utilising synectic triggers can help expand the creative concept space of designers. Random inspirations and tangential thoughts can enhance creativity (Nolan Reference Nolan2003), and the usage of analogical thinking is highlighted for new product development and innovation (Goel Reference Goel1997). As synectics promote out-of-the-box thinking by making the familiar strange and the strange familiar, this process contributes to linking concepts that have a far-field conceptual distance, thereby increasing the likelihood of producing novel outcomes.

RQ2: How do patterns of turn-taking and initiative control between humans and AI affect the outcomes of a co-creative ideation process?.

![]() $ {Ha}_2 $

: The participants of the ideation process would have a higher sense of interaction with the tool in a spontaneous decision-making flow. Focussing on the interaction patterns in a collaborative process, Oh et al. (Reference Oh, Song, Choi, Kim, Lee and Suh2018) stressed the importance of interaction styles and modality for designing co-creative systems. The support utilises timely triggers and dynamic context gathering to monitor user discussions and provide feedback. The user-centred approach ensures that participants have greater control over the AI tool and can determine when the system should intervene in their creative process.

$ {Ha}_2 $

: The participants of the ideation process would have a higher sense of interaction with the tool in a spontaneous decision-making flow. Focussing on the interaction patterns in a collaborative process, Oh et al. (Reference Oh, Song, Choi, Kim, Lee and Suh2018) stressed the importance of interaction styles and modality for designing co-creative systems. The support utilises timely triggers and dynamic context gathering to monitor user discussions and provide feedback. The user-centred approach ensures that participants have greater control over the AI tool and can determine when the system should intervene in their creative process.

RQ3: How do different combinations of synectics analogies (Fantasy, Direct, Personal) influence the creative dimensions (Novelty, Usefulness, Direct)?

![]() $ {Ho}_3 $

: There is no significant influence of synectics analogy triggers on the dimensions of creative output.

$ {Ho}_3 $

: There is no significant influence of synectics analogy triggers on the dimensions of creative output.

![]() $ {Ha}_3 $

: There is a significant influence of synectics analogy triggers on one or more dimensions of creative output. The rationale is that synectics encourages the use of unfamiliar and unconventional concepts as an approach to ideation, thereby distancing the original problem context with the help of analogies from diverse and unrelated domains. Direct analogies, as they represent functional similarities in the relationships, may lead to more useful analogies. In contrast, Fantasy analogies may promote higher novel analogies by drawing a forced connection between unimaginable concepts.

$ {Ha}_3 $

: There is a significant influence of synectics analogy triggers on one or more dimensions of creative output. The rationale is that synectics encourages the use of unfamiliar and unconventional concepts as an approach to ideation, thereby distancing the original problem context with the help of analogies from diverse and unrelated domains. Direct analogies, as they represent functional similarities in the relationships, may lead to more useful analogies. In contrast, Fantasy analogies may promote higher novel analogies by drawing a forced connection between unimaginable concepts.

RQ4: Which architecture of models perform better for improving creativity metrics?

![]() $ {Ha}_4 $

: Transformer-based models tend to achieve overall better performance. Comparing Transformer and Mixture of Experts (MoE) models, dense transformer architectures have higher coherence and deeper contextual understanding, while the MoE architecture offers potential for greater knowledge breadth, diversity of specialised domain expertise, and generating varied ideas. Thus, the holistic activation of all parameters in dense transformers ensures consistency across all creativity metrics, while the MoE models activate only a few parameters across their expert sub-networks, allowing access to border knowledge, leading to higher novel concepts but at the cost of coherence and consistency lapses.

$ {Ha}_4 $

: Transformer-based models tend to achieve overall better performance. Comparing Transformer and Mixture of Experts (MoE) models, dense transformer architectures have higher coherence and deeper contextual understanding, while the MoE architecture offers potential for greater knowledge breadth, diversity of specialised domain expertise, and generating varied ideas. Thus, the holistic activation of all parameters in dense transformers ensures consistency across all creativity metrics, while the MoE models activate only a few parameters across their expert sub-networks, allowing access to border knowledge, leading to higher novel concepts but at the cost of coherence and consistency lapses.

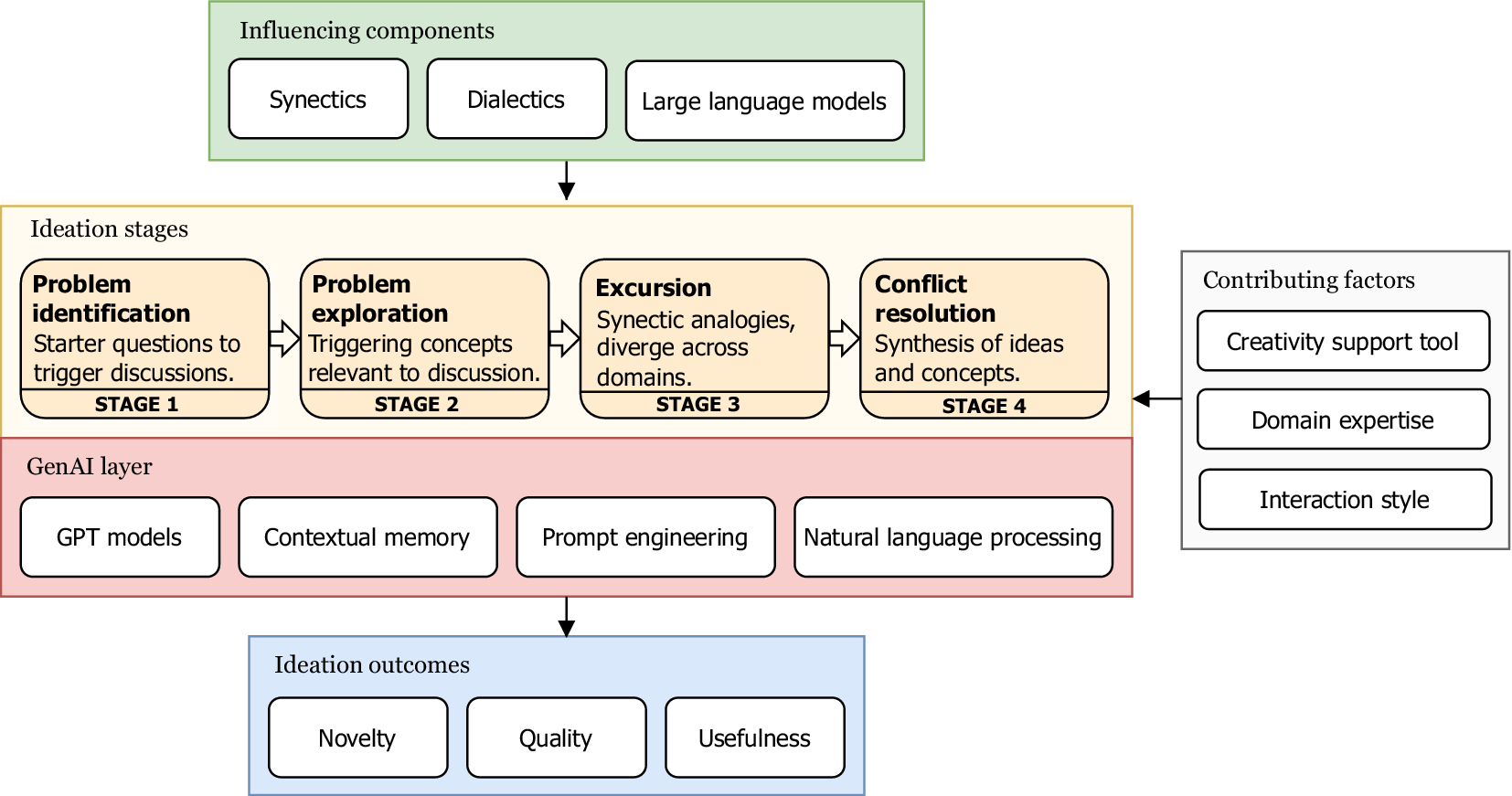

4.3. Conceptual framework

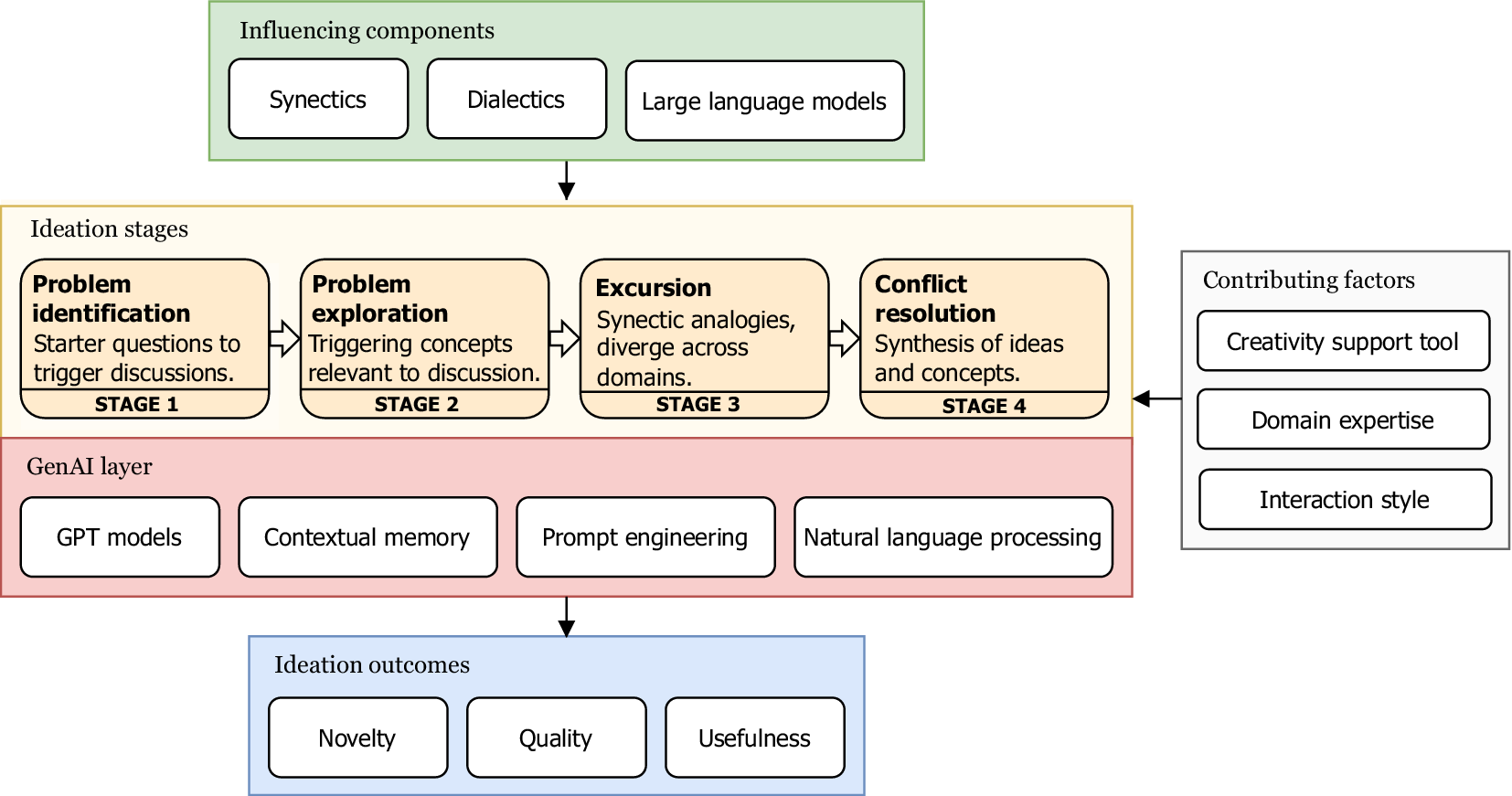

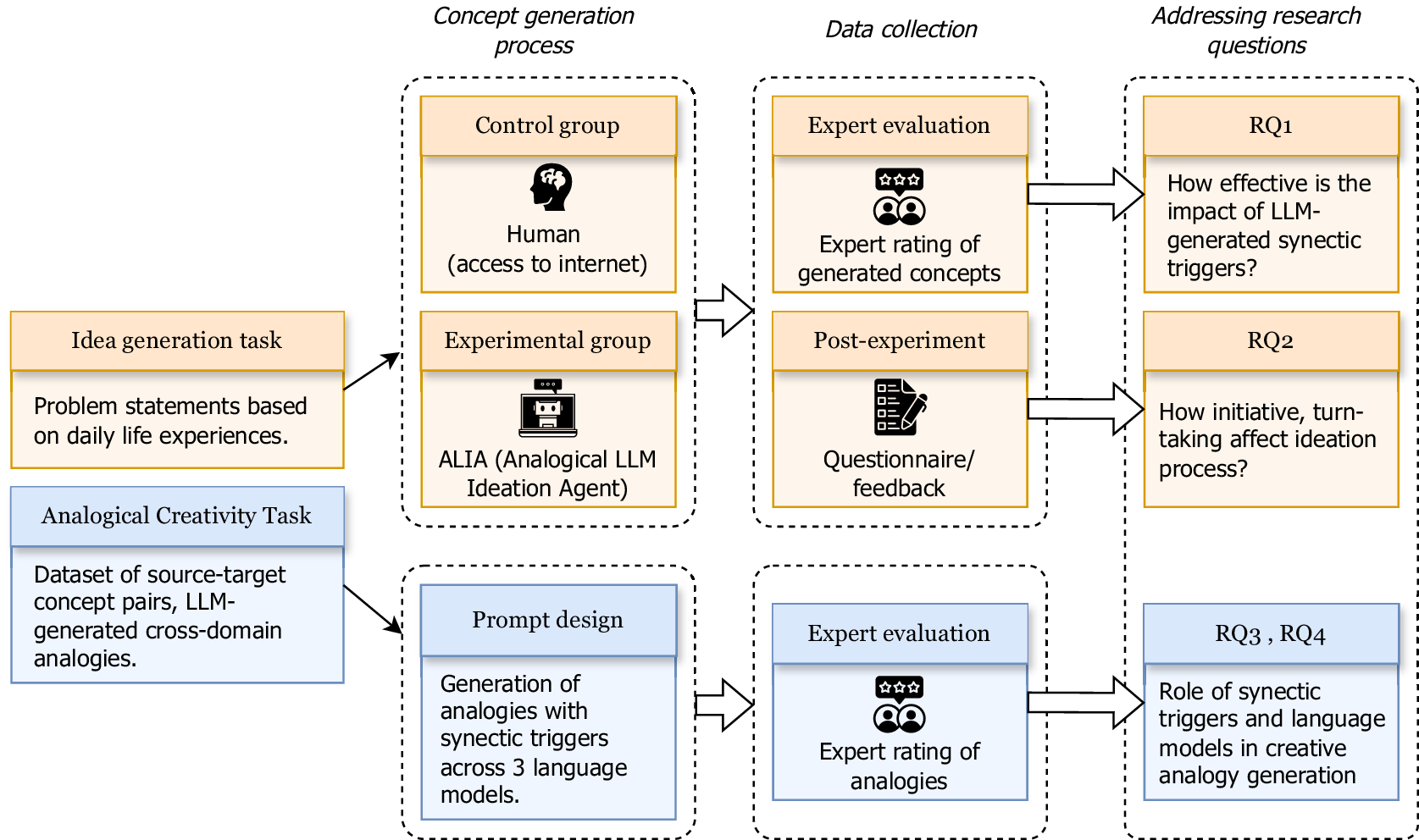

In this study, we propose a conceptual framework (see Figure 1) that integrates LLMs into a structured DbA process, based on synectics and dialectical reasoning. The core ideation stages provide an iterative phase of convergent-divergent thinking for exploring flexible idea domains and conflict resolution mechanisms helpful in synthesizing the concepts.

Figure 1. Conceptual framework for LLM-assisted analogical creativity.

A Generative AI (GenAI) layer serves as the foundation for contextually relevant content generation, utilising Generative Pre-trained (GPT) models to produce relevant output, prompt engineering to guide the model, and Natural Language Processing (NLP) methods to enable linguistic operations such as speech-to-text and conversation summarisation. The GenAI layer operates across all the ideation stages and serves two primary purposes: first, gathering contextual information of the topic being discussed; second, generating content in the form of textual stimuli based on the ideation stage and context gathered. The framework takes into consideration external contributing factors that generally affect any co-creative ideation session. The existence of a creativity support tool, human–machine interaction paradigms, and the domain expertise of the participants are some of the moderating factors that may affect the overall creative output. In the study, we further explain how each of these variables is addressed using the support tool for achieving higher creative outcomes. The framework employs four ideation stages – Stage 1 (Problem identification): the initial stage works on building a common understanding of the problem statement and familiarisation of the topic among all the contributors. “How-might-we” questions are derived from the problem statement early in the process, encouraging preliminary discussion and reframing of the topic to ensure alignment. This step addresses the differences in domain knowledge or experience that may affect the initial understanding of the needs and goals. By establishing a common ground, this stage provides initial triggers to overcome mental blocks and form a consistent level of knowledge about the topic before proceeding to the next ideation stage. Stage 2 (Problem exploration): this stage generates contextually relevant keywords based on the initial discussion and the defined problem statement. This facilitates exploration of related domains based on insights by utilising conversation summaries as contextual input for the language model, which generates a list of words. Here, discussion is encouraged for selecting the keyword that aligns with the group’s interests and proceeding with exploration in the chosen avenue. This process initially converges and then diverges the conceptual space while maintaining the scope relevant to the core problem and previous group discussions. Stage 3 (Excursion): this stage employs the synectics approach for ideation, introduced by Gordon (Reference Gordon1961), which makes use of specific triggers in the form of analogies to tap the psychological states, promoting a creative activity in problem identification and problem-solving tasks. This process involves making the strange familiar and making the familiar strange. Being open and receptive to random inspiration and tangential thoughts can enhance creativity (Nolan Reference Nolan2003). Synectics alienates the original problem context through analogical thinking. Blosiu (Reference Blosiu1999) employed synectics in their study as an idea seeding technique, where they explored the usage of metaphors and analogies to stimulate imagination and creativity. The types of analogies employed in synectics are as follows – personal: finds relationships between the individual and known phenomenon or imagines oneself as an object, element or part of the problem; direct: relationship between two unrelated phenomena without self-involvement; symbolic: a logical unit represented by a symbol, which can be natural objects, humans, or abstract ideas; fantasy: relationships that may be unrealistic and push the boundaries of conventional thinking. Stage 4 (Conflict resolution): Conflict resolution employs the dialectical thinking method to apply concepts and ideas discussed in earlier stages of the session. Leveraging Hegelian dialectical philosophy, this stage aims to analyse the concepts from a holistic approach by considering the proposition and its negating view, which are driven by the thesis and antithesis statements, respectively. The tension created between opposing statements of thesis and antithesis propels the discussion forward, generating a synthesis.

4.4. Analogical LLM Ideation Agent (ALIA)

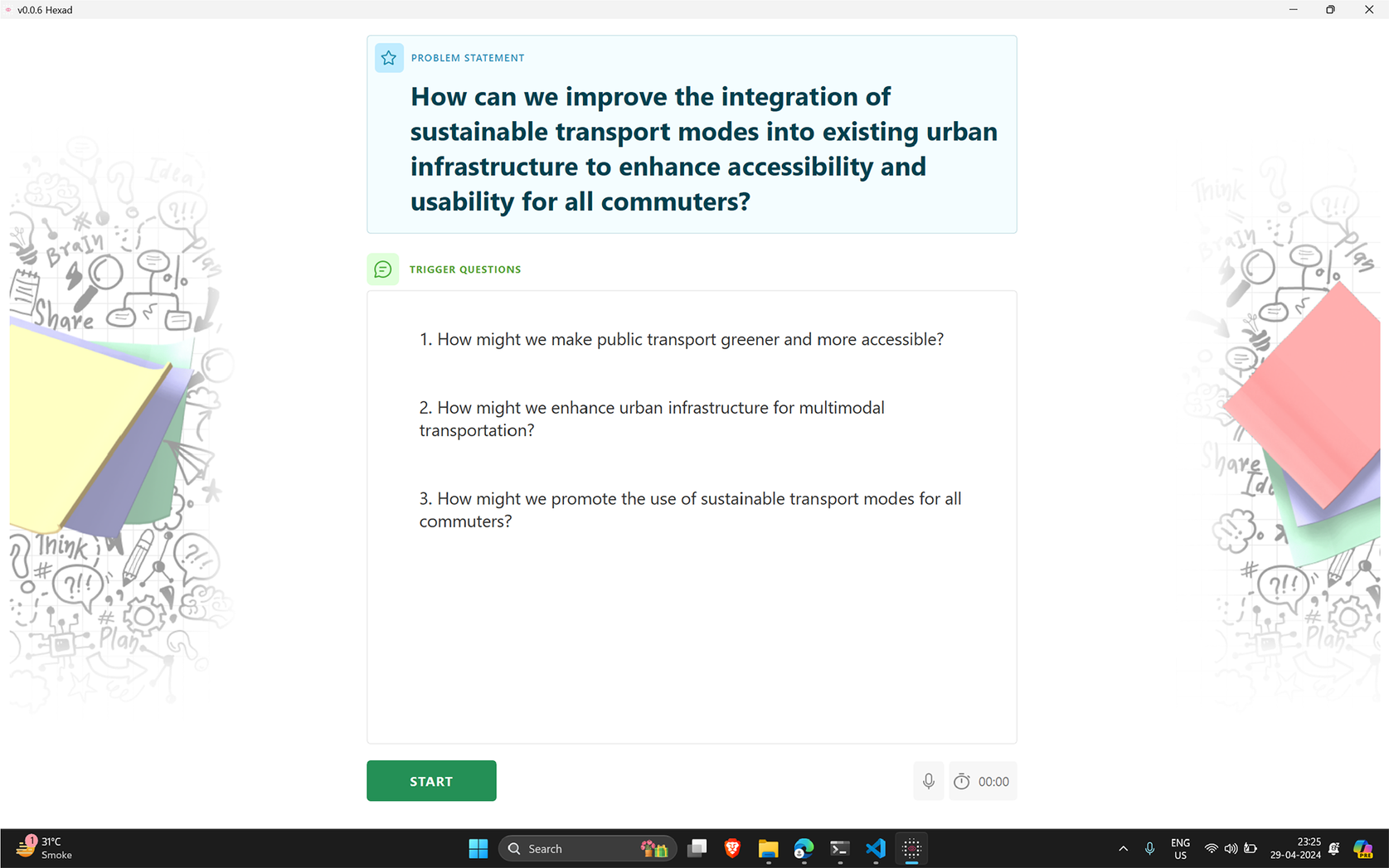

Analogical LLM Ideation Agent (ALIA) is a desktop-based application (see Figure 2) to be used in a group ideation session. The tool utilises generative AI technologies, including LLMs, speech-to-text algorithms, text summarisation and prompt engineering techniques to generate responses in the form of analogies and dialectical statements in real-time, acting as an active participant in the ideation session. This section explains how ALIA works, its objectives and its role in ideation sessions.

Figure 2. User interface of ALIA showing one of the stages of ideation.

4.4.1. System overview

The ALIA support tool serves as an active collaborator during ideation sessions, leveraging LLM-generated responses to drive the creative process (see Figure 3). ALIA operates by providing contextually relevant stimuli in the form of trigger questions, analogies and dialectical statements throughout the ideation session. The process is intended to generate diverse cross-domain concepts and support conflict resolution within the groups. Ideation sessions with ALIA facilitate integration of human involvement and system-level contributions within a collaborative physical space. At the human level, participants actively engage in the discussion by applying their creative thought process to the problem statement provided. The list of problem statements is reported in Appendix A. In parallel, ALIA contributes by analysing the participant discussion and generating contextual stimuli – analogies and responses by leveraging the text-generation capabilities of LLMs. The interaction is further enhanced by incorporating both digital and physical mediums, where participants utilise physical artefacts like sticky notes and a canvas for scribbling, visualising the concepts. Simultaneously, ALIA delivers prompts on the screen, thereby fostering a hybrid mode of brainstorming where participants can rely on a digital medium to augment tasks and also utilise physical methods for better articulation and higher collaboration. Prior research (Jensen et al. Reference Jensen, Thiel, Hoggan and Bødker2018) indicates a hybrid approach where a combination of physical artefacts and digital systems can improve collaboration, articulation and engagement among the participants during creative ideation tasks. The ongoing demand inspires the system design of ALIA in the design research community of hybrid co-creative systems.

Figure 3. Participants using ALIA in an ideation session.

4.4.2. User flow

Throughout all the stages of ideation, ALIA continuously runs a real-time speech-to-text service that captures the participant’s discussion and transcribes it into a summary over the course of the session. The system aims to leverage the speech modality for a concise and contextually relevant understanding of the participant’s discussion. A summarised conversation is fed to the LLM as a prompt for generating trigger questions and analogies. The LLM serves as the backbone of the system, undertaking tasks such as summarisation and real-time response generation. The ideation session with ALIA lasts 30 minutes, during which participants are exposed to the ideation stages, starting from understanding the problem statement and generating concepts, and reflecting on their ideas using sticky notes (see Appendix B, Figure B1 for concepts generated by a group). In prior studies, researchers have studied the relationship between time pressure and creativity. Amabile & Mueller (Reference Amabile and Mueller2024) found that by applying time pressure, creative thinking is hindered as the quality and originality of ideas are reduced. Moreover, based on feedback from pilot tests, participants suggested that 30 minutes is the ideal duration for the idea-generation task. The input and task analysis of participants helped the researchers determine the duration of the task. In individual settings, time pressure can enhance creativity, whereas in groups, it may decrease (Paulus & Dzindolet Reference Paulus and Dzindolet2008). Although time pressure increases productivity, a time constraint can compromise creativity levels and ultimately suggest a controlled and thoughtful imposition of time constraints (Liikkanen et al. Reference Liikkanen, Björklund, Hämäläinen and Koskinen2009). Hence, each stage of the ideation session is divided into specific time intervals. Each ideation stage has a predefined duration – for instance, Stage 1 is conducted for 6 minutes, after which participants are shown visual feedback with an LED indicator. Participants may either proceed to the next stage or continue their discussion of the current stage as needed. Similarly, Stages 2, 3, and 4 have predefined durations of 8 minutes, 6 minutes, and 8 minutes, respectively. These times are determined based on preliminary studies with a pilot group, with the objective of achieving a relatively balanced contribution and engagement from all stages within the overall 30-minute ideation session.

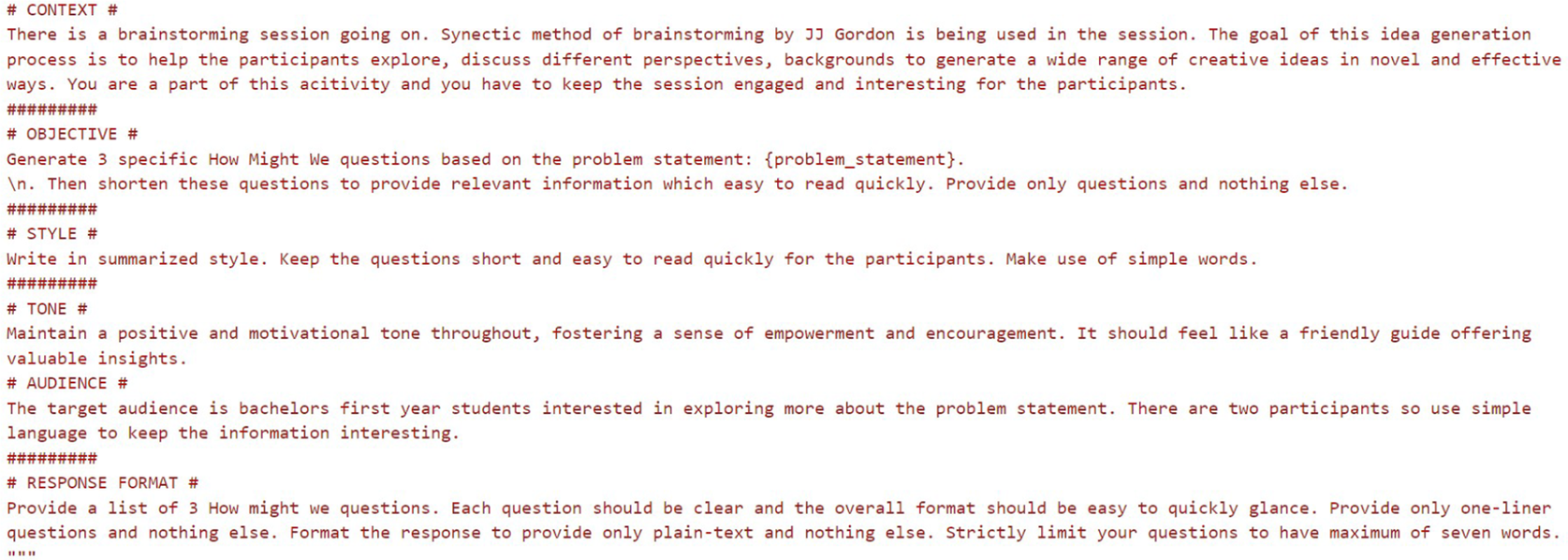

4.4.3. Prompt engineering

Prompt templates were created to elicit suggestions from the LLM in the form of analogies, trigger questions, and dialectics, among other approaches. The LLM was given natural language instructions as prompts, which included specific aims, goals, objectives, and various other parameters. Structuring the prompts is a crucial step in the system for formulating effective instructions to guide the LLM in generating contextually relevant content. For this study, the COSTAR (Context, Objective, Style, Tone, Audience, Response) prompting template was used to craft effective prompts (see Figure 4). COSTAR follows a step-by-step approach in detailing the information that needs to be explained to the LLM. This approach enables the language model to capture the required context and generate responses that align with user expectations. Iterations of the template were evaluated for a desirable response and accuracy across all four stages of the ideation process. The generated content was tested across various open-source language models, where the evaluation criteria – quality of analogies generated, accuracy of response format followed, and general language – were used by the researchers to evaluate and choose the model for inference in the tool.

Figure 4. COSTAR prompt template used in ALIA.

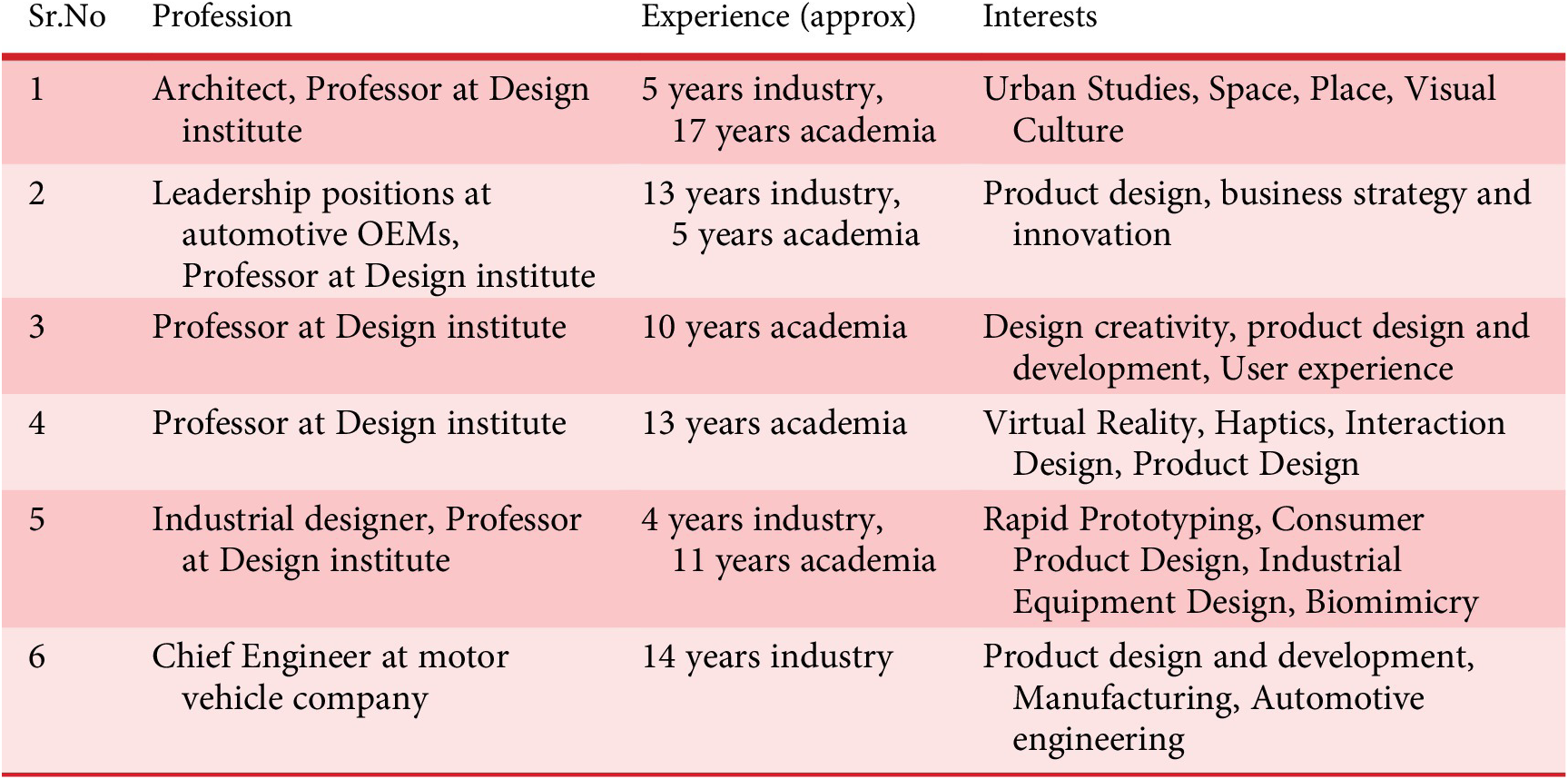

4.4.4 Expert evaluation of ideas

Six professional, industry-experienced designers with more than 10 years of work experience in the design industry were recruited as expert raters to evaluate the ideas and concepts generated during the ideation sessions. The profiles of the expert raters are mentioned in Appendix C (Table C1). For the evaluation, a total of 36 idea solutions from the ideation experiment were shortlisted. The ideas were divided into two sets, each consisting of 18 unique ideas, to balance the workload and ensure reliability checks. All three raters in a set had to evaluate the same 18 ideas. In a set, an equal number of ideas, that is, nine from the control and experimental group, were included and randomly ordered for evaluation. Evaluations were conducted on a custom web-based platform. Raters were initially shown the problem statement, and then after a brief interval, the corresponding idea solution and a 5-point Likert scale. The raters were asked to rate each idea based on the novelty and quality criteria, as well as to provide optional descriptive comments in the field. The requirements were defined as: (i) Novelty: How unique is the idea compared to existing solutions in this context to you? and (ii) Quality: How feasible, practical and useful is the idea within the context?. The entire evaluation process was conducted online, where the raters had to fill out their ratings on the web platform. Upon completing the evaluation, a spreadsheet of the responses would be downloaded onto their system, which they were instructed to send back to the researchers.

4.5. Analogical Creativity Task (ACT)

To address the gap of standardised creativity benchmarks for LLM-generated analogies, systematic cross-domain analogy tasks were conducted. The aim was to evaluate our proposed method of triggering creativity with synectic triggers and study the fundamental nature of LLMs when exposed to analogical creativity tasks. The tasks involved generating a dataset of analogies and conducting human evaluations of output content for benchmarking different language models and trigger combinations.

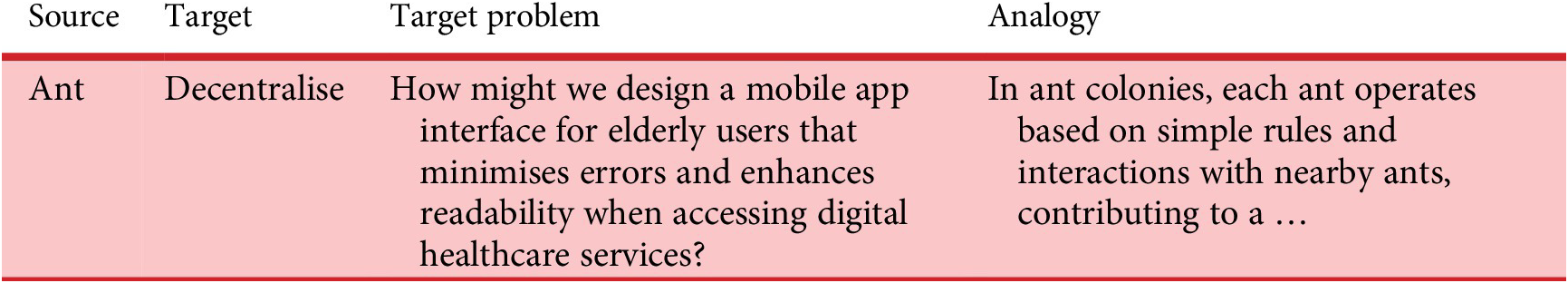

4.5.1. Dataset of analogical concepts

A dataset consisting of a source concept and a target concept with a far-field conceptual distance, a target problem and the generated LLM output was curated. The source concepts were from diverse domains – science, nature and art and culture, whereas the target concepts consisted of practical design concepts. From this dataset, a subset of 18 concept pairs was selected to create structured prompts and generate output analogies (Table 1). The models were prompted with the given concept pairs, and responses were recorded for each model across different synectic trigger mechanisms – direct, personal and fantasy. Each prompt was engineered with tailored instructions to apply the synectic trigger, explicitly directing the model to describe and state the relationship between the source and target concepts in the context of the problem. For each synectic trigger category, 40 analogies were generated using the three selected language models, resulting in a pool of 120 analogy datasets suitable for performance comparison in terms of creativity metrics. Across all models, a total of 360 analogies were generated as a dataset of far-field LLM-generated analogies for problem-based ideation. A comparative analysis of language models was conducted to investigate the impact of model architecture, parameter size and training data on the generated output in creative tasks. The study focused on two main architectural paradigms: Transformer-based models and MoE models. Within these categories of models, ChatGPT gpt-4o (OpenAI 2025), Claude 3.5 Haiku (Anthropic 2025) and Mixtral-8x7B (Jiang et al. Reference Jiang, Sablayrolles, Roux, Mensch, Savary, Bamford, Chaplot, de las Casas, Hanna, Bressand, Lengyel, Bour, Lample, Lavaud, Saulnier, Lachaux, Stock, Subramanian, Yang, Antoniak, Scao, Gervet, Lavril, Wang, Lacroix and Sayed2024) were systematically assessed for their analogy content generation in a creative context. A standardised temperature setting of value 0.80 was configured across all the models to ensure consistency in output variability and a uniform experimental setting. To generate the responses through each model, the respective APIs provided by OpenAI, Claude and Ollama (Ollama 2025) were accessed via Python scripts for analogy generation.

Table 1. Sample analogy pairing dataset

4.5.2. Human evaluation of ACT

Human evaluation was conducted, where five expert raters assessed the analogies based on the creativity criteria of novelty, usefulness and elaboration quality. Expert raters recruited for this task were PhD scholars with formal academic design training, specialising in design research, product and service design and human–computer interaction. From the overall dataset, 18 analogies – six per language model – were sampled for detailed analysis and presented to the evaluators. The evaluation was conducted through a web-based platform similar to the one used in the idea-evaluation process. Experts were instructed to rate analogies using a 5-point Likert scale across three metrics: (i) Novelty: How original or surprising is this analogy in this context? (ii) Usefulness: How helpful is this analogy for sparking relevant ideas? And (iii) Elaboration quality: How well does the brief clarify the connection and its potential? Following the evaluation task, the raters’ responses were analysed for further comparative insights into the effectiveness of language models across different synectic triggers and cross-domain analogical generation in creative ideation contexts.

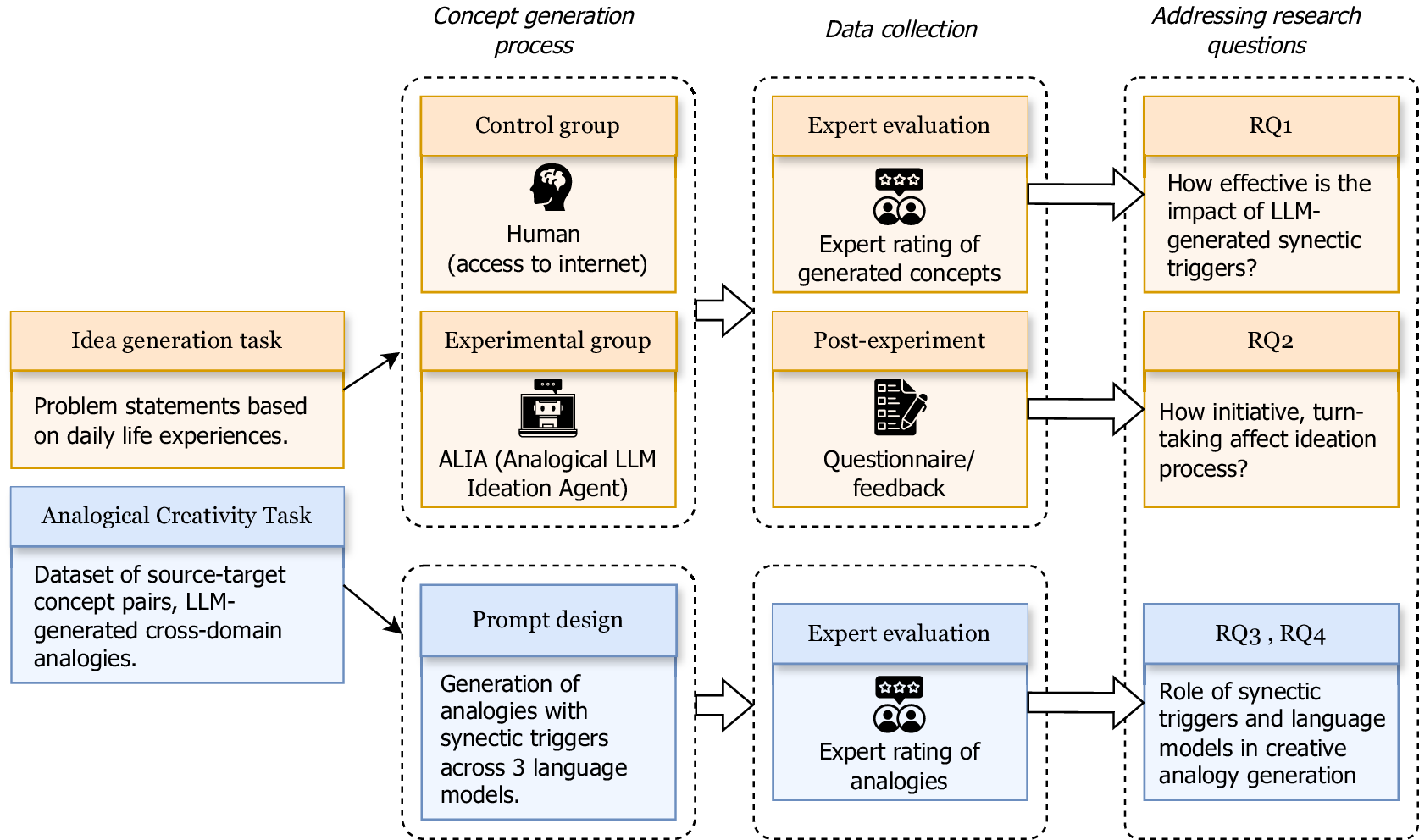

4.6. Experimental design

The experiment design involves an idea-generation task utilising ALIA (Analogical LLM Ideation Agent) and ACT (Analogical Creativity Task) to assess the effectiveness of LLM-generated output in the context of the creative ideation process (see Figure 5). Data collection includes the concepts and ideas generated by participants, along with qualitative feedback on the ideation process and interaction with the support tool. The concepts were evaluated by human experts and analysed to answer RQ1, while the analysis of qualitative feedback on the ideation activity and support tool was used to address RQ2. In ACT, expert raters evaluated a curated dataset of analogies generated by the researchers. The analysis of expert ratings is used to answer RQ3 and RQ4.

Figure 5. Overview of experimental study design.

4.6.1. Participant sampling

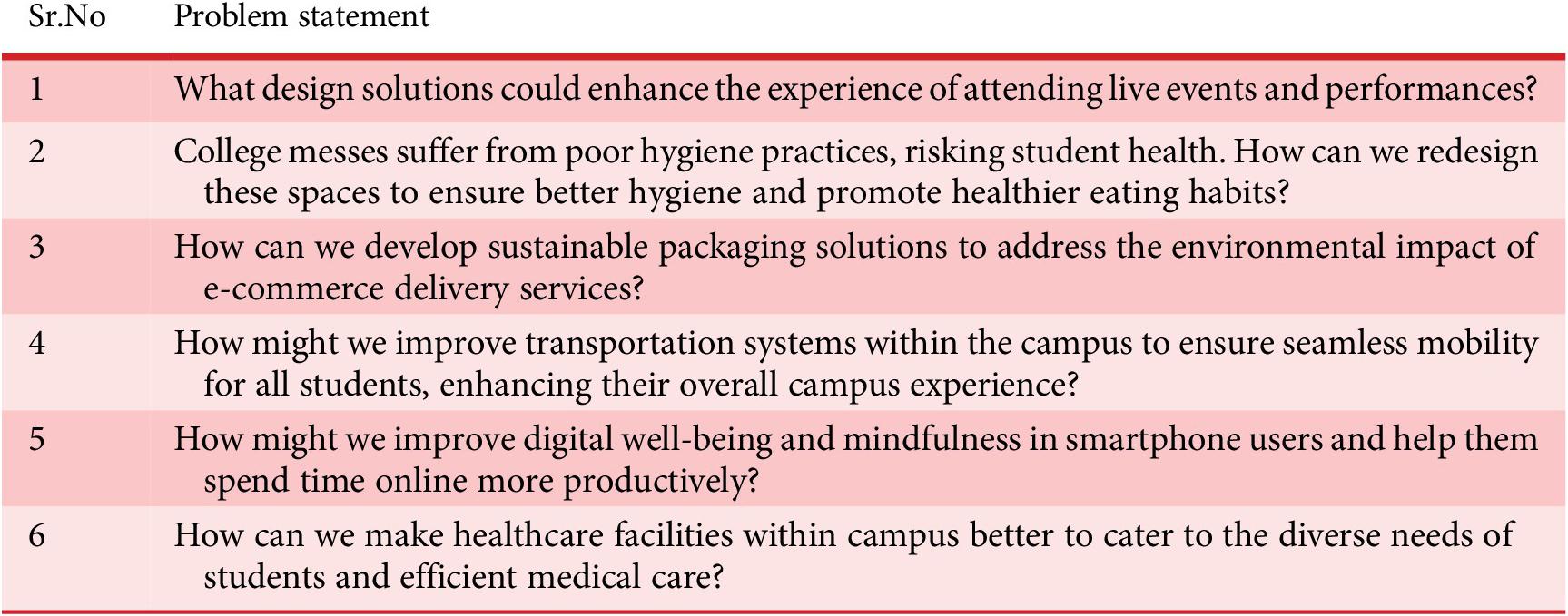

A total of 24 first-year undergraduate design students from the Indian Institute of Technology Hyderabad, were selected for the idea-generation tasks. In this study, we consider students to be the novice designers and participants of the experiment based on their limited design learning experience and lack of prior working experience on projects involving a complete design process (Deininger et al. Reference Deininger, Daly, Sienko and Lee2017). Similarly, supporting studies have investigated students as a subset of novice designers (McRobbie, Stein, & Ginns Reference McRobbie, Stein and Ginns2001); students with less than 4 years of design learning experience as novice designers (Chen et al. Reference Chen, Song, Guo, Sun, Childs and Yin2025); and students from a first-year engineering design course as novice designers (Alsager Alzayed et al. Reference Alsager Alzayed, Starkey, Ritter and Prabhu2025). Studies have highlighted a varying difference between novice and expert designers during the concept-evaluation process. Novices are more likely to use design heuristics related to the given concept, whereas experts tend to rely on heuristics based on past domain knowledge (Dixon & Bucknor Reference Dixon and Bucknor2019). Novices are open to learning from immediate feedback (McRobbie et al. Reference McRobbie, Stein and Ginns2001), adopting a “trial and error” approach (Ahmed-Kristensen, Wallace, & Blessing Reference Ahmed-Kristensen, Wallace and Blessing2003) to build understanding, exhibiting reliance on external instructional support and benefitting from it (Reimlinger et al. Reference Reimlinger, Lohmeyer, Moryson and Meboldt2020; Budinoff, McMains, & Shonkwiler Reference Budinoff, McMains and Shonkwiler2024). In contrast, experts generally rely on internal domain knowledge and generative reasoning to propose solutions in the early stages of ideation (Lloyd & Scott Reference Lloyd and Scott1994; Ahmed-Kristensen et al. Reference Ahmed-Kristensen, Wallace and Blessing2003; Chen, Yan-Ting, & Chia-Han Reference Chen, Yan-Ting and Chia-Han2022), making them less reliant on tool feedback (Budinoff et al. Reference Budinoff, McMains and Shonkwiler2024). In the context of our study, experts may rely on leveraging their existing knowledge to enhance concepts rather than the suggestions provided by the LLM, making it difficult to isolate and evaluate the LLMs’ impact on ideation activity. Thus, based on these observations, novices tend to engage with the external support tool in an unbiased manner, making them suitable candidates for independently evaluating the framework and the tool’s effectiveness. Focusing on novice designers would offer deeper insights into the potential role and impact of LLMs in the ideation process. All participants were randomly paired to form teams and then divided into either the control or experimental group. Each of the six teams was presented with six distinct problem statements during the idea-generation task, and the same set of problem statements was given to both the baseline and control groups.

4.6.2. Data collection and procedure

The primary outcome of the idea-generation experiments was a set of ideas generated by the participants across the control and experimental groups. In the control group, participants were presented with a problem statement displayed on a screen and instructed to generate concepts without using any prescribed ideation method. Participants were permitted to access online resources, such as Wikipedia and ChatGPT, during the session. Generic problem statements related to everyday life experiences were presented to the participants (see Appendix A). In the experimental group, participants were instructed to use ALIA as an assistive tool in the creative process. The role of ALIA was to moderate the session by presenting the problem statement, generating idea suggestions and creative triggers, managing time and providing stage-specific prompts aligned with the conceptual framework proposed. Across both groups, all ideas from the sticky notes were gathered, digitised and stored in spreadsheet format for later analysis. All the ideation sessions were audio-video recorded and transcribed to supplement the ideation concepts output. Digital folders for each participant pair were created, which included their digitised documents, audio transcriptions and audio-video recordings. Physical documents, such as sticky notes and consent forms, were organised in a separate file. Personal information of the participants, such as names and contact details, was only registered on the consent forms and was subsequently removed during the digitisation process in spreadsheets. Unique IDs were assigned to each participant across control and experimental groups, where the mapping was known to the researchers and managed in a separate sheet. After each ideation session, all the participants completed a post-experiment questionnaire on Google Forms, designed to capture their feedback on the process, their interaction levels with ALIA and the overall effectiveness of the tool in generating ideas. The questionnaire is detailed in Appendix D. Spreadsheet data of the questionnaire feedback was utilised for performing qualitative analysis.

4.6.3. Ethical approval

We have studied the ethical guidelines described in the ICMR National Ethical Guidelines (Mathur & Swaminathan Reference Mathur and Swaminathan2017). Based on these guidelines, we have taken consent from the participants for their participation in the study. Participants were given detailed task instructions, followed by an informed consent form that outlined the study’s purpose, aim, data handling details, and voluntary enrolment in the experiment (see Appendix E, Figure E1). The participants were clearly informed in the consent form that their audio and video would be recorded during the ideation session and would be processed anonymously for research purposes only. Participants had the right to withdraw from the study at any time. A copy of the informed consent form and task instruction sheet is provided in the appendix.

5. Results

In this section, the findings are presented addressing the research questions based on the analysis of evaluation tasks. Initially, we analyse the tool performance in the ideation process to answer RQ1. Secondly, RQ2 is addressed by examining the interaction and collaboration patterns between the human and the AI creativity support tool. To evaluate the analogical creativity, the Analogical Creativity Task (ACT) was employed as a structured benchmarking test. The outcomes of the evaluation conducted on ACT are reported, which discusses the comparative studies of different language models and their performance in analogical tasks. Analysis of the ACT evaluations is used to address RQ3 and RQ4.

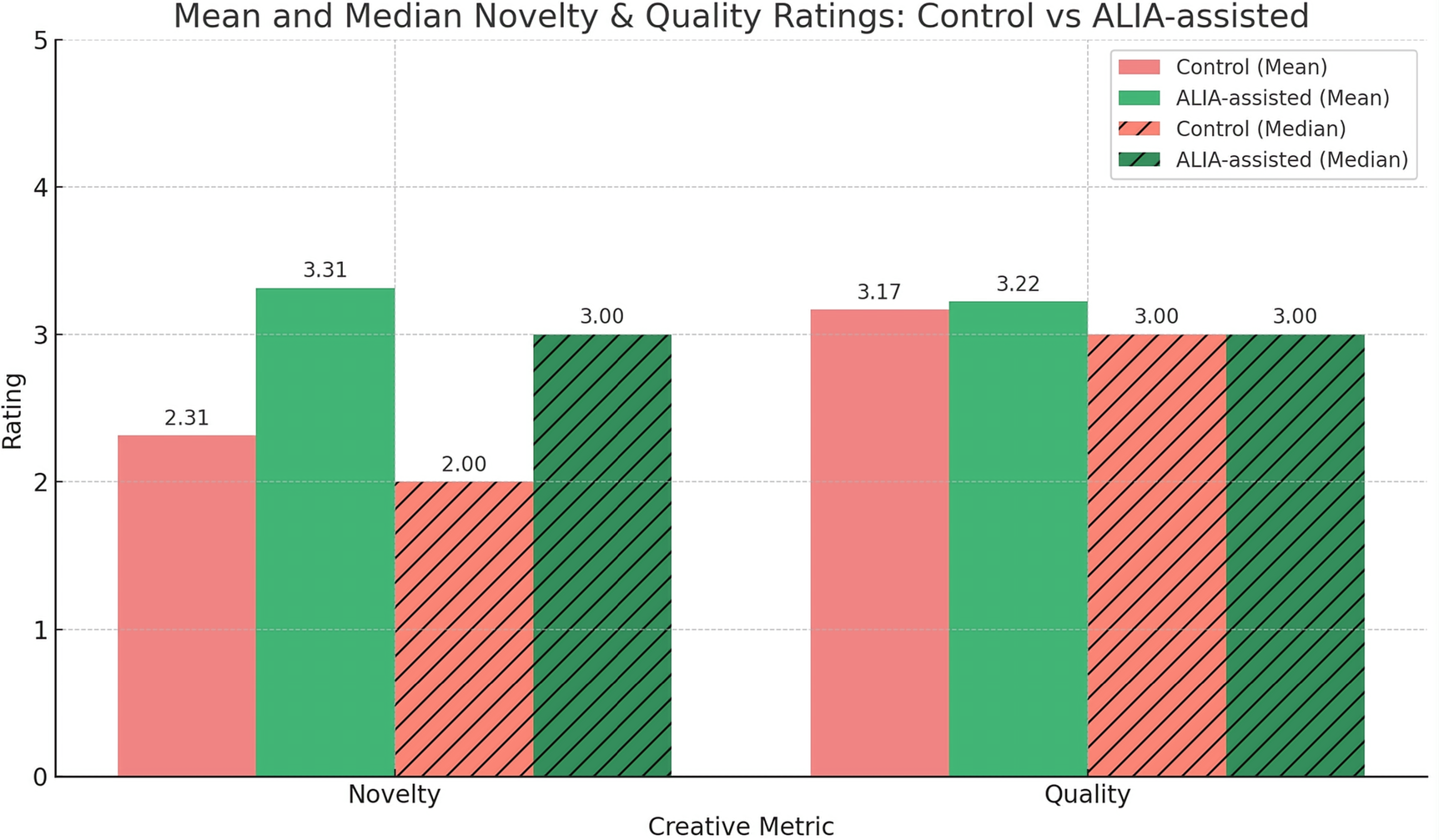

5.1. RQ1: How effectively do creative heuristics drive the LLM support tool

This section outlines the assessments of the creativity support tool and a comparative analysis of the ideation performance of participants across the control and ALIA-assisted ideation group. To evaluate the reliability of expert ratings across two groups, each idea was independently assessed by three experts per set (a total of six raters across the two sets). For data analysis, the internal consistency of ratings was first evaluated using Cronbach’s alpha, yielding acceptable values for both novelty (

![]() $ \alpha $

= 0.632) in set 1 and (

$ \alpha $

= 0.632) in set 1 and (

![]() $ \alpha $

= 0.715) in set 2. Following the establishment of rating consistency, we tested whether the novelty and quality scores for the Experimental and Control groups differed significantly (see Figure 6). As a Likert scale was used for novelty and quality ratings, non-parametric independent Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted due to the ordinal nature of the data. The results revealed a significant difference in the novelty scores between the groups (U = 770.0,

$ \alpha $

= 0.715) in set 2. Following the establishment of rating consistency, we tested whether the novelty and quality scores for the Experimental and Control groups differed significantly (see Figure 6). As a Likert scale was used for novelty and quality ratings, non-parametric independent Mann–Whitney U tests were conducted due to the ordinal nature of the data. The results revealed a significant difference in the novelty scores between the groups (U = 770.0,

![]() $ p<0.05\Big) $

, whereas for quality (U = 1431.0,

$ p<0.05\Big) $

, whereas for quality (U = 1431.0,

![]() $ p>0.05 $

) (see Table 3). The experimental ALIA-assisted group scored higher mean novelty ratings (M = 3.31, SD = 1.02) with a median of 3.00, while the control group resulted in lower novelty ratings (M = 2.21, SD = 1.11) with a median of 2.00. The 95% confidence interval for mean novelty in the ALIA-assisted group was [3.04, 3.59], whereas for the control group it was [2.01, 2.62]. In terms of the quality dimension, both conditional groups showed similar central tendencies - the control group (M = 3.17, SD = 1.48) with a median of 3.00, and the ALIA-assisted group (M = 3.22, SD = 1.25) with the same median value of 3.00. The median values reflect no apparent difference in the central tendency of idea quality across both conditions. Summarising, the results indicate that the ALIA-assisted group yielded higher-rated novel ideas, while the idea quality across both groups was comparable. These findings provide support for rejecting the null hypothesis (

$ p>0.05 $

) (see Table 3). The experimental ALIA-assisted group scored higher mean novelty ratings (M = 3.31, SD = 1.02) with a median of 3.00, while the control group resulted in lower novelty ratings (M = 2.21, SD = 1.11) with a median of 2.00. The 95% confidence interval for mean novelty in the ALIA-assisted group was [3.04, 3.59], whereas for the control group it was [2.01, 2.62]. In terms of the quality dimension, both conditional groups showed similar central tendencies - the control group (M = 3.17, SD = 1.48) with a median of 3.00, and the ALIA-assisted group (M = 3.22, SD = 1.25) with the same median value of 3.00. The median values reflect no apparent difference in the central tendency of idea quality across both conditions. Summarising, the results indicate that the ALIA-assisted group yielded higher-rated novel ideas, while the idea quality across both groups was comparable. These findings provide support for rejecting the null hypothesis (

![]() $ {H}_1o $

) and accepting the alternative hypothesis (

$ {H}_1o $

) and accepting the alternative hypothesis (

![]() $ {H}_1o $

), indicating that the LLM-generated synectic and dialectical thinking support tool has a significant positive effect on the novelty of ideas.

$ {H}_1o $

), indicating that the LLM-generated synectic and dialectical thinking support tool has a significant positive effect on the novelty of ideas.

Figure 6. Comparing average novelty and quality ratings across Control and Experimental groups.

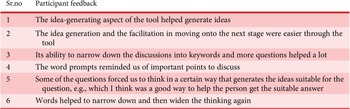

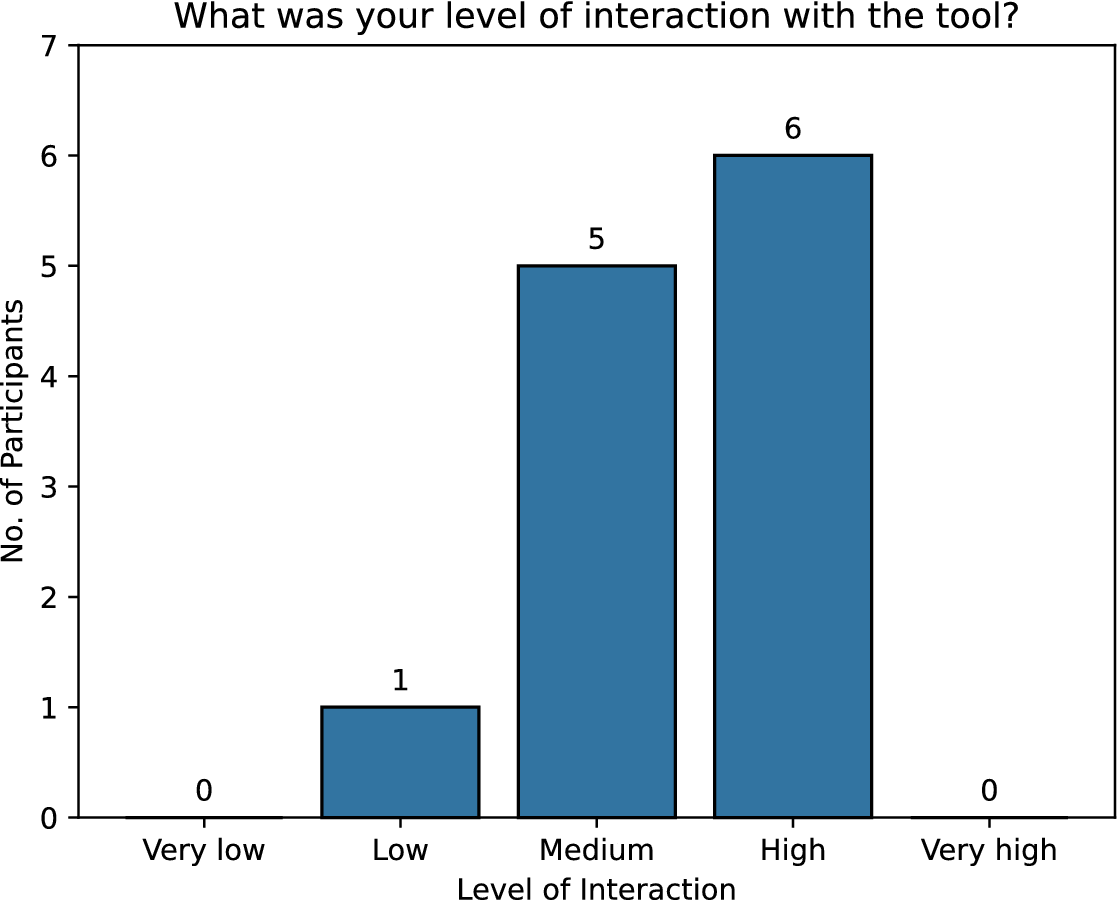

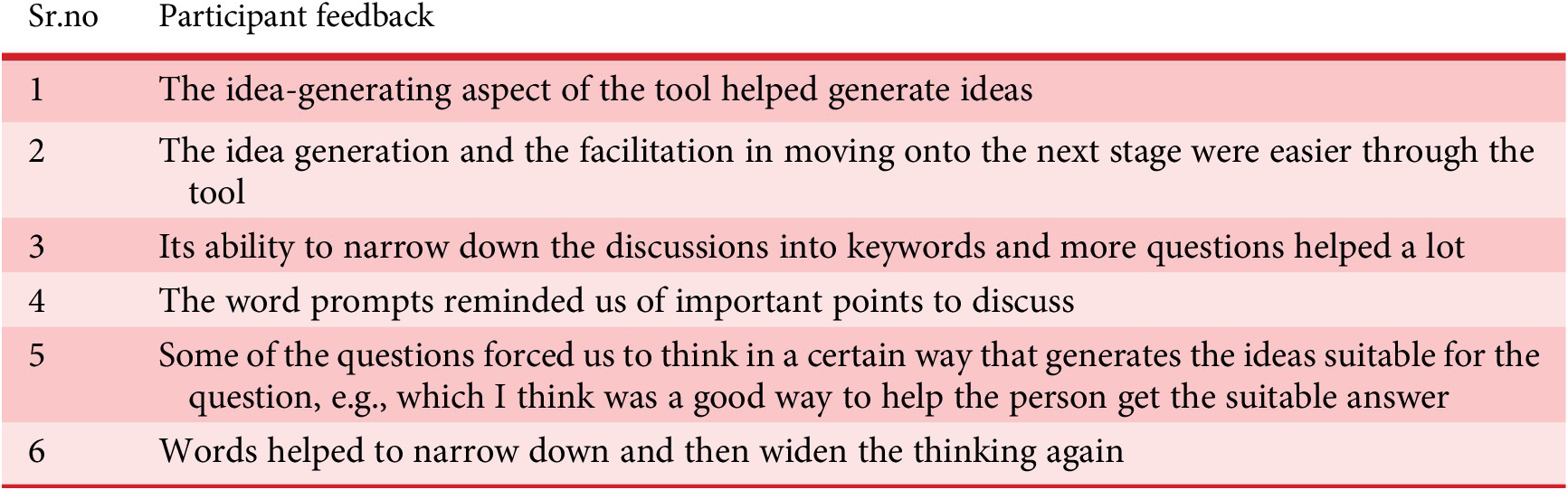

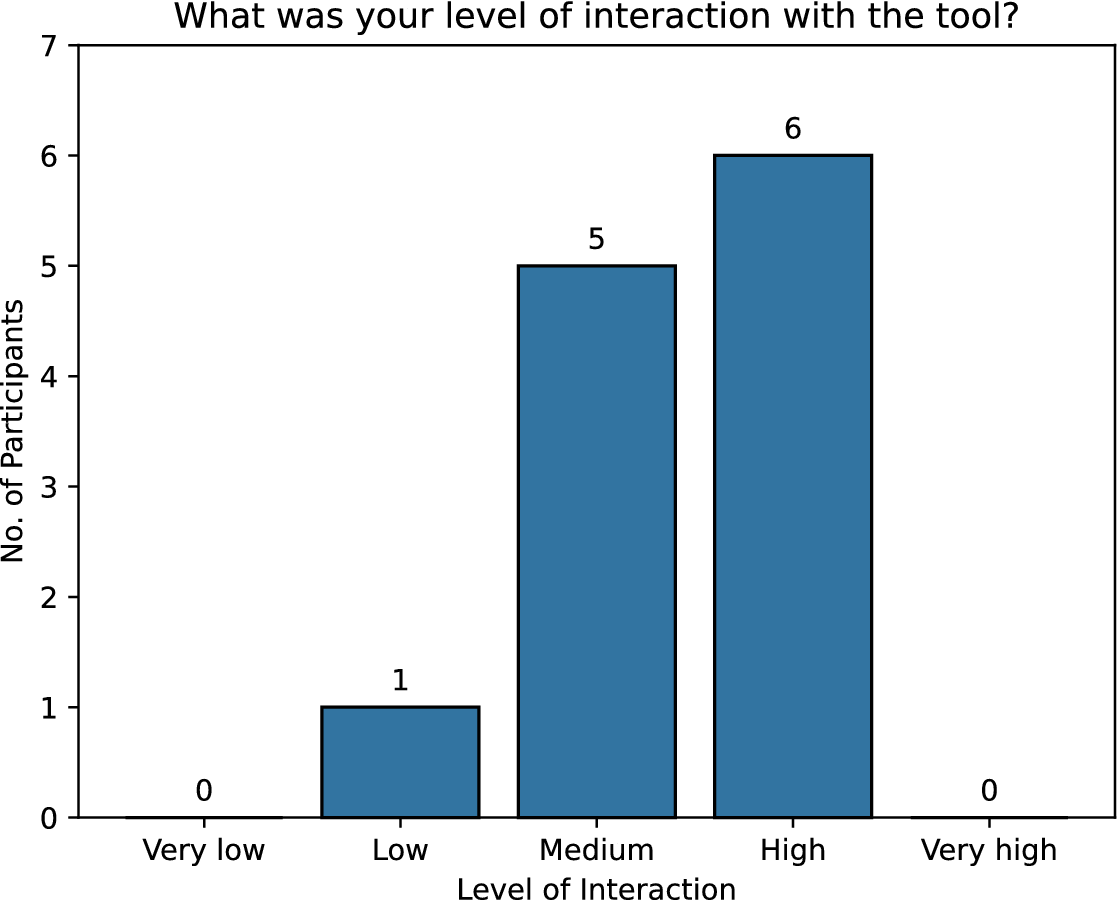

5.2. RQ2: Investigating the role of human–AI interaction style

A qualitative feedback survey was conducted with the participants after the ideation session to assess the degree of interaction with the ALIA support tool. Using a 5-point Likert scale ranging from Very Low to Very High, participants were asked to rate their level of interactivity with the tool. Among the 12 participants in the ALIA-assisted group, almost 50% (6 participants) had a “High” degree of interaction, while 5 participants exhibited “Medium” levels of interaction with the tool (Figure 7). The participants highlighted their experiences using the tool during the ideation session, across mainly themes of: idea-generation support, structured thinking and progression and cognitive scaffolding with prompts (see Table 2). The participants affirmed the tool’s ability to direct ideas (P1), with special mention of its utility in fostering new ideas (idea-generation aspect). Additionally, they acknowledged the tool for promoting a smooth transition between idea-generation phases (P2), indicating the dynamic and continuous progression towards idea development. Participant 3 noted the tool’s capacity to “narrow down the discussions into keywords and more questions helped a lot,” indicating how the tool assisted them in organising a structured approach with timely trigger questions. Similarly, Participant 6 emphasised how the prompts helped “narrow down and then widen the thinking again,” suggesting the roles of divergent-convergent phases of the tool in augmenting divergent thinking among participants. Feedback was related to the prompting nature of the tool “word prompts reminded us of important points to discuss” (P4) and forcing the participants to frame their thoughts in a suitable and appropriate manner to guide the person with the task at hand.

Table 2. Participant feedback on using the tool during the ideation session

Table 3. Descriptive statistics of model comparisons across creativity dimensions

Figure 7. Interaction of participants with the ALIA tool.

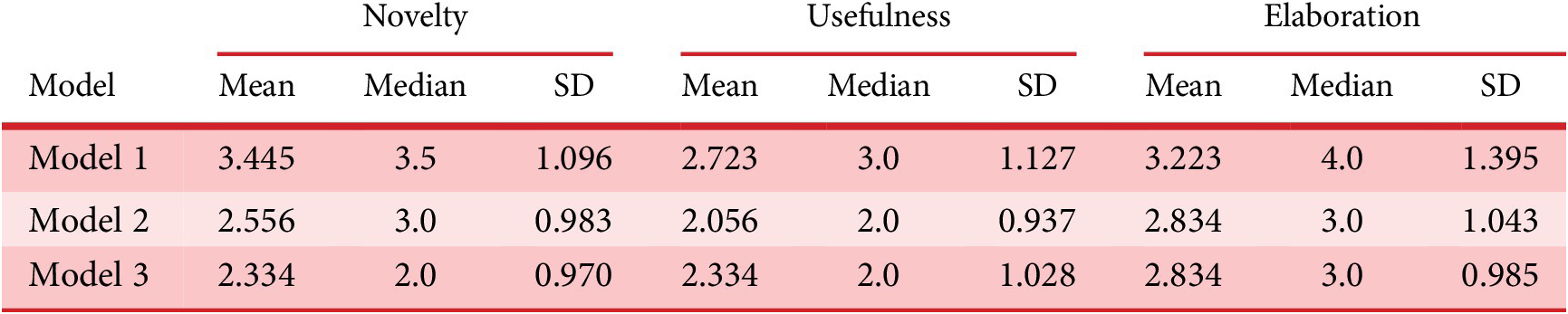

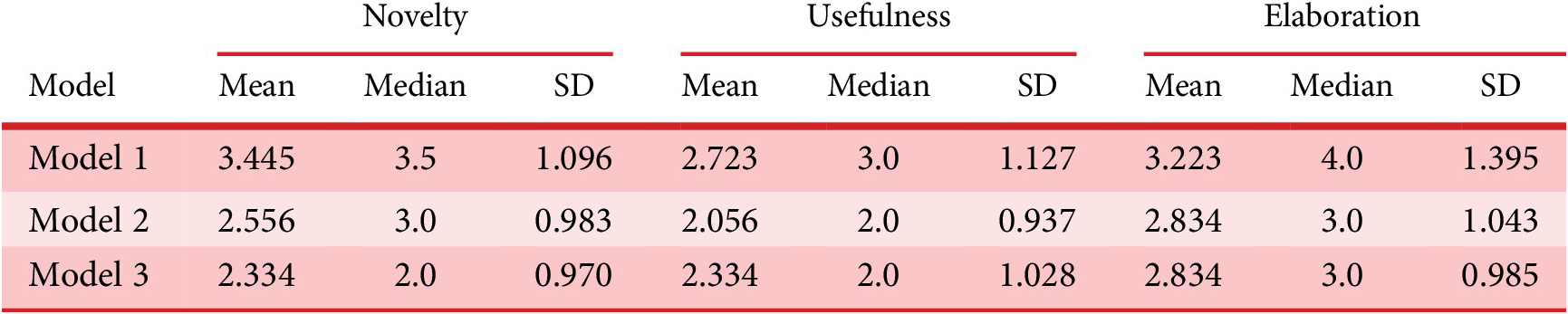

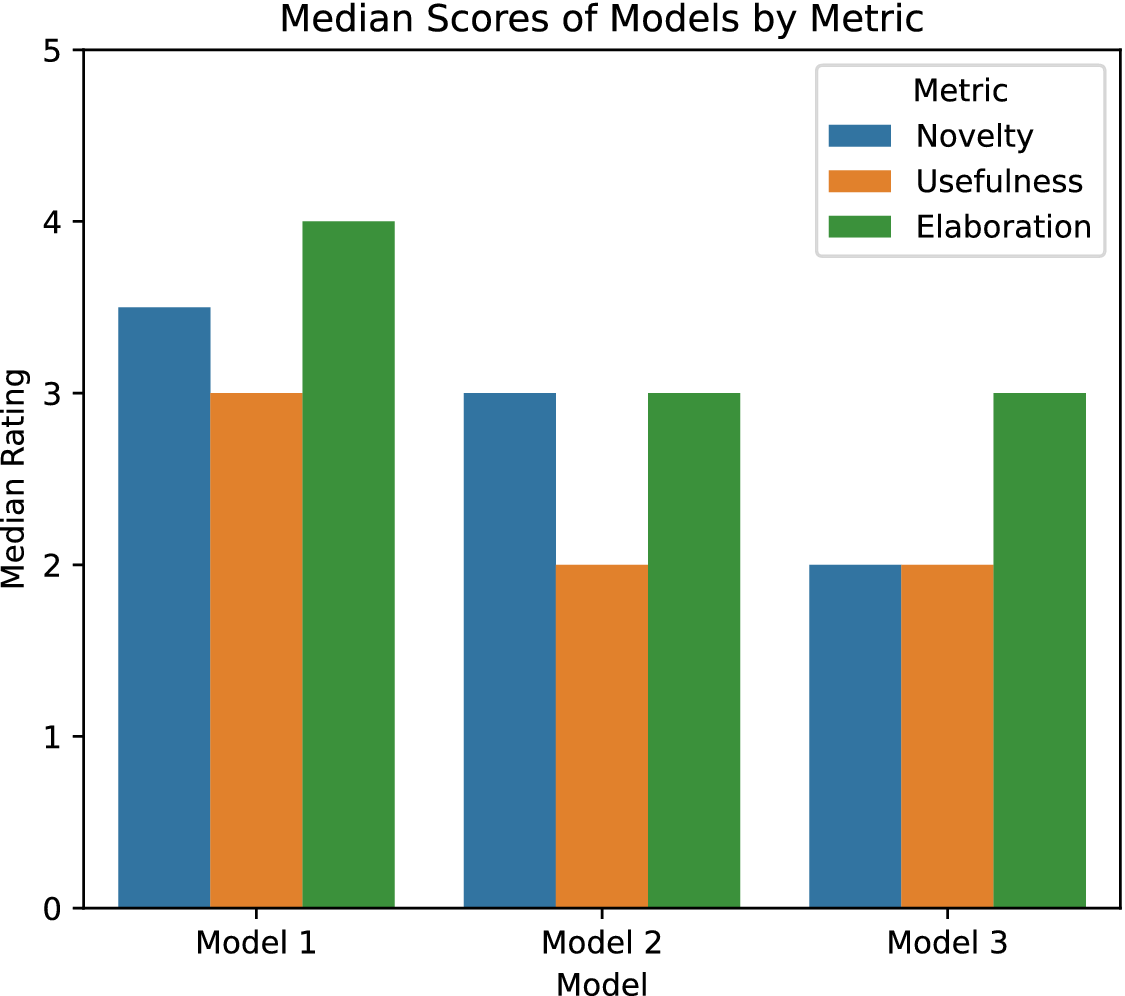

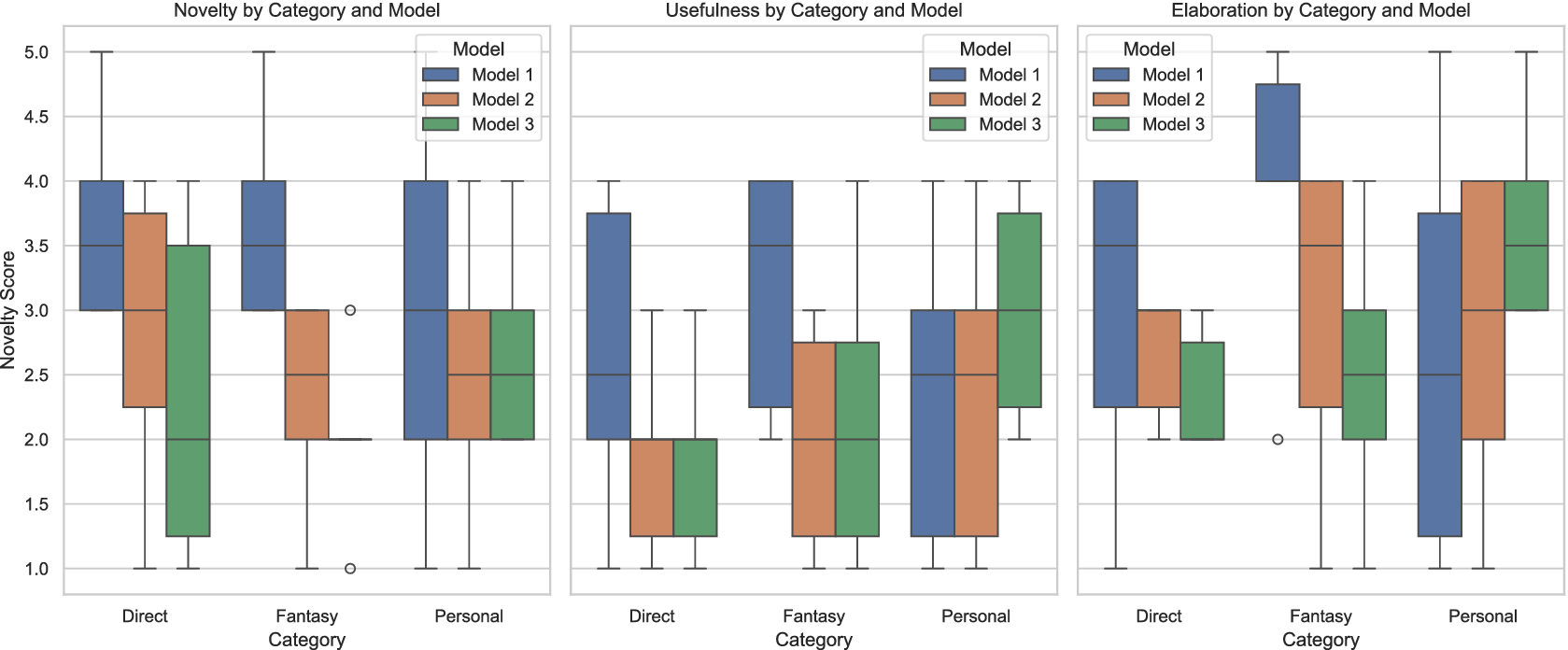

5.3. RQ3, RQ4: Investigating the role of language models and synectic prompt strategies

Addressing RQ3 and RQ4, the comparative performance of the large language models using the three synectic prompt strategies – direct, personal and fantasy – is evaluated across the three key dimensions: Novelty, Usefulness and Elaboration. Statistical measures are computed for the type of Models used (Model 1, Model 2, Model 3), which differ in their architecture and provider. These tests are conducted to assess the impact of the model type on the predefined three creative dimensions. Furthermore, the descriptive tests check the influence of the synectic prompt category (personal, fantasy, direct) on the creative dimensions.

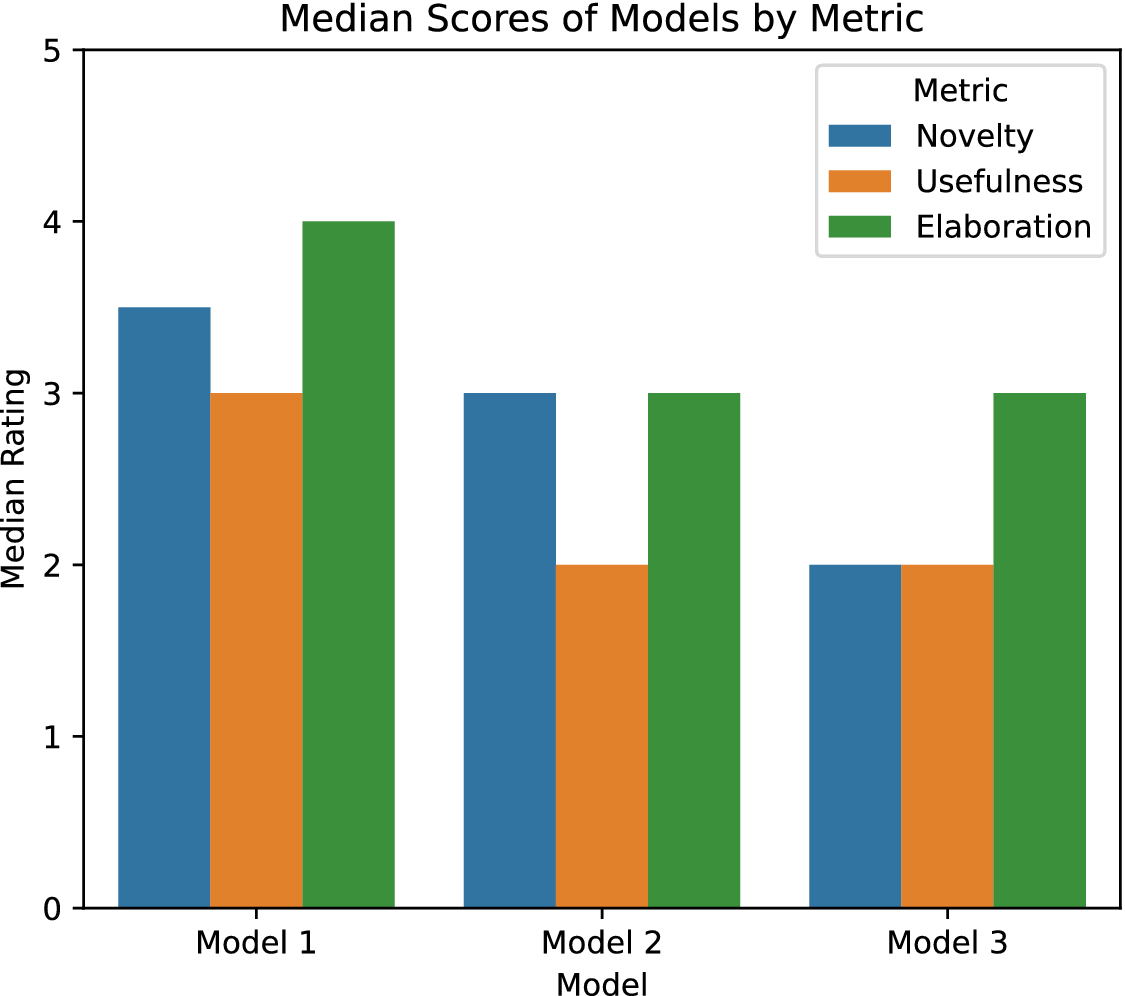

5.3.1. Evaluation of language models

Descriptive statistics for each dimension are presented in Table A1. The three LLMs studied are coded as Model 1(ChatGPT gpt4o), Model 2(Claude haiku) and Model 3(Mixtral8x7), comparison shown in Figure 8. In terms of novelty, Model 1 scored highest (M = 3.445, SD = 1.096), followed by Model 2 (M = 2.556, SD = 0.983) and the lowest was for Model 3 (M = 2.334, SD = 0.970). Similar trends are seen across usefulness and elaboration dimensions, where Model 1 consistently outperforms the other models. Usefulness scores varied across the models, with Model 1 having a mean usefulness rating (M = 2.723, SD = 1.127, Mdn = 3.0), followed by Model 2 and Model 3. Furthermore, Model 1 again scored the highest rating for elaboration quality across the three models. This hints at the effectiveness of Model 1 across multiple dimensions. Non-parametric tests on the three dependent dimensions were conducted to assess further whether the model type affected the creative dimensions of generated ideas. The Kruskal–Wallis H test was used to examine any significant variations in the scores of the three models. Checking the statistical differences in Novelty (

![]() $ {\chi}^2(2)=9.826,\hskip0.5em p=0.007 $

), the tests showed that a specific type of model generated concepts with significantly different Novelty scores than others, indicating the strong influence of model type on the novelty metrics of generated ideas. No significant differences were found in Usefulness (

$ {\chi}^2(2)=9.826,\hskip0.5em p=0.007 $

), the tests showed that a specific type of model generated concepts with significantly different Novelty scores than others, indicating the strong influence of model type on the novelty metrics of generated ideas. No significant differences were found in Usefulness (

![]() $ {\chi}^2(2)=3.358,\hskip0.75em p>0.05 $

) and Elaboration (

$ {\chi}^2(2)=3.358,\hskip0.75em p>0.05 $

) and Elaboration (

![]() $ {\chi}^2(2)=1.576,\hskip0.5em p>0.05 $

) dimensions across the models.

$ {\chi}^2(2)=1.576,\hskip0.5em p>0.05 $

) dimensions across the models.

Figure 8. Comparison of creativity metrics across models.

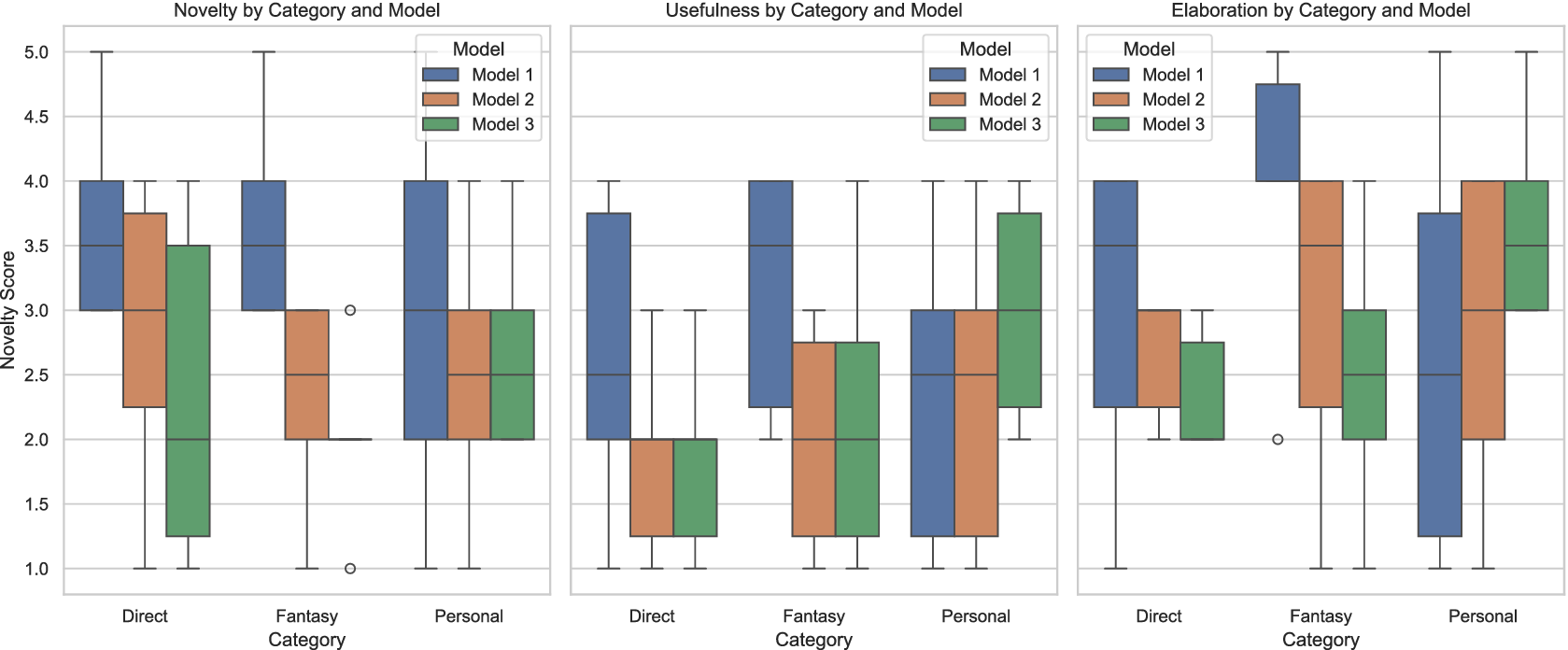

5.3.2. Evaluation of synectics prompting strategies

The three synectic prompt strategies – personal, fantasy and direct – are evaluated across the three model types for the defined creativity dimensions to investigate the influence of the strategies (see Figure 9). For Novelty, the Direct category exhibits a broader range of scores across models, where Model 1 scores the highest, reaching up to a maximum score of 5. Although Model 3 performs most weakly in the Direct category (Mdn = 1.5), it slightly improves in Personal contexts (Mdn = 2.5), suggesting that the model type may struggle with straightforward instructional tasks. Similarly, for the Fantasy category of analogies, Model 1 showed a higher novelty median as compared to other models. In contrast, the Personal analogies score is consistent across models. Across all the models, the Fantasy category yielded the most inconsistent novelty scores, indicating the difficulty in consistently generating innovative outputs. For Usefulness, the overall distribution of the Direct category shows that Model 1 scores substantially higher than the other models. Whereas Models 2 and 3 both show comparatively less usefulness when using direct analogies. Across the Fantasy category, Model 1 still maintains higher Usefulness (Mdn

![]() $ \sim $

4), while Models 2 and 3 although having a wide spread of distribution have a lower central tendency. In the Personal category, Model 3 appears to perform better (Mdn

$ \sim $

4), while Models 2 and 3 although having a wide spread of distribution have a lower central tendency. In the Personal category, Model 3 appears to perform better (Mdn

![]() $ \sim $

3), contrasting its weakness across the Novelty dimension, suggesting that prompts seem more useful when generated by Model 3. Summarising, although Fantasy analogies contribute to usefulness primarily because of Model 1, Personal analogies also tend to produce higher-rated useful analogies (Mdn

$ \sim $

3), contrasting its weakness across the Novelty dimension, suggesting that prompts seem more useful when generated by Model 3. Summarising, although Fantasy analogies contribute to usefulness primarily because of Model 1, Personal analogies also tend to produce higher-rated useful analogies (Mdn

![]() $ \sim $

3–4), better than Direct and Fantasy, mainly when using Model 3. Thus, depending on the combination of model type and category used, when using Model 1, Direct and Fantasy analogy prompting yields higher useful analogies; when using Model 3, Personal analogy prompting yields higher useful analogies. The Elaboration dimension primarily investigates how well a generated analogy brief clarifies the relationship and its potential. As seen previously, this is also the case here, where Model 1 dominates the elaboration quality in Direct analogies, possibly due to its richer capabilities in understanding instructional tasks. In Fantasy analogies, Model 2 and Model 3 score lower than Model 1; however, they both perform well in Personal analogies. Model 1 has a broader spread in Personal prompts, indicating inconsistency in ratings. Thus, making use of Model 2 and Model 3, along with Personal analogical prompts, produces better-elaborated briefs explaining the analogical relationships, indicating that these models may be optimised for detailed and specific responses.

$ \sim $

3–4), better than Direct and Fantasy, mainly when using Model 3. Thus, depending on the combination of model type and category used, when using Model 1, Direct and Fantasy analogy prompting yields higher useful analogies; when using Model 3, Personal analogy prompting yields higher useful analogies. The Elaboration dimension primarily investigates how well a generated analogy brief clarifies the relationship and its potential. As seen previously, this is also the case here, where Model 1 dominates the elaboration quality in Direct analogies, possibly due to its richer capabilities in understanding instructional tasks. In Fantasy analogies, Model 2 and Model 3 score lower than Model 1; however, they both perform well in Personal analogies. Model 1 has a broader spread in Personal prompts, indicating inconsistency in ratings. Thus, making use of Model 2 and Model 3, along with Personal analogical prompts, produces better-elaborated briefs explaining the analogical relationships, indicating that these models may be optimised for detailed and specific responses.

Figure 9. Comparison of grouped synectic prompt categories across models on creativity dimensions.

Analysing the categorical patterns – Fantasy prompts amplify novelty in Model 1, Direct prompts perform well, especially for the usefulness and elaboration dimensions in Model 1, and Personal prompts boost elaboration and usefulness when used for Model 3 and Model 2. To investigate the significance of prompt categories on the creativity dimensions, a Kruskal–Wallis H test was conducted, which showed no significant difference (

![]() $ p>0.05\Big) $

in using a specific analogy prompt alone for influencing the creativity dimensions. This suggests that the prompt categories used in combination with the language model contribute towards achieving the desired creativity results. Addressing RQ3: How do different combinations of synectics analogies (Fantasy, Direct, Personal) influence the creative dimensions (Novelty, Usefulness, Direct)? It can be concluded that the synectics categories alone may not contribute for the creative dimensions thus retaining the null hypothesis (

$ p>0.05\Big) $

in using a specific analogy prompt alone for influencing the creativity dimensions. This suggests that the prompt categories used in combination with the language model contribute towards achieving the desired creativity results. Addressing RQ3: How do different combinations of synectics analogies (Fantasy, Direct, Personal) influence the creative dimensions (Novelty, Usefulness, Direct)? It can be concluded that the synectics categories alone may not contribute for the creative dimensions thus retaining the null hypothesis (

![]() $ {H}_3o $

), but require the presence of a specific language model for effective results across creative dimensions. Addressing RQ4: Which architecture of models performs better for improving creativity metrics?, the transformer-based architecture (Model 1) showed dominance and consistent performance in novelty and elaboration, particularly for Direct and Fantasy analogies. Model 1 scored a higher median novelty and elaboration scores relative to the Mixture-of-Experts-based Model 3 (Mixtral). Transformer-based architecture, due to its dense attention-based contextual reasoning, may support diverse idea exploration across analogy prompts. Whereas Model 3 demonstrated selective results, having generally a lower novelty score, yet showed competitive usefulness and elaboration for personal analogies. This insight may suggest that the specialised subnetworks in Mixtral may perform better in capturing contextually grounded prompts to generate relatable analogies. Overall, the results indicate that transformer-based architectures are more effective in generating novel and elaborated analogical content, whereas MoE models show creative potential in personalised situations. These insights highlight that the architecture of a language model may play a critical role in generating creative inspiration.

$ {H}_3o $

), but require the presence of a specific language model for effective results across creative dimensions. Addressing RQ4: Which architecture of models performs better for improving creativity metrics?, the transformer-based architecture (Model 1) showed dominance and consistent performance in novelty and elaboration, particularly for Direct and Fantasy analogies. Model 1 scored a higher median novelty and elaboration scores relative to the Mixture-of-Experts-based Model 3 (Mixtral). Transformer-based architecture, due to its dense attention-based contextual reasoning, may support diverse idea exploration across analogy prompts. Whereas Model 3 demonstrated selective results, having generally a lower novelty score, yet showed competitive usefulness and elaboration for personal analogies. This insight may suggest that the specialised subnetworks in Mixtral may perform better in capturing contextually grounded prompts to generate relatable analogies. Overall, the results indicate that transformer-based architectures are more effective in generating novel and elaborated analogical content, whereas MoE models show creative potential in personalised situations. These insights highlight that the architecture of a language model may play a critical role in generating creative inspiration.

6. Discussion

6.1. AI co-creativity leveraging design heuristics

Leveraging LLMs to generate analogical stimuli based on creative heuristics like synectics and dialectical reasoning enhanced the creative output of novice designers. Designers using the support tool produced higher-rated novel ideas as compared to those working without our tool’s intervention. However, the quality of ideas generated by the support tool groups was slightly better, but the difference was not significant. This indicates that AI systems, when posed as creative partners, can foster analogical creativity in ideation tasks to produce novel ideas. Building upon the findings of existing studies on the effect of analogical creativity with LLMs, this study emphasises the quantitative and qualitative evaluation of the concepts based on creativity metrics in design ideation tasks.

In the growing body of studies on cross-domain analogical ideation for innovative and breakthrough idea generation (Dahl & Moreau Reference Dahl and Moreau2002; Chan et al. Reference Chan, Fu, Schunn, Cagan, Wood and Kotovsky2011; Jia et al. Reference Jia, Becattini, Cascini and Tan2020), our framework addresses the challenges of guiding analogy generation across ideation contexts, unlike prior creative support tools that rely on static knowledge bases (KBs) and domain-limited retrieval for analogy generation. This framework leverages the generative and dynamic content-generation capabilities of LLMs to simulate creative leaps across diverse domains. Based on the results of the idea-generation activity, groups using the ALIA support tool generated more novel and innovative ideas. The median novelty and quality ratings of ideas were higher across ALIA-assisted groups. Inferential tests highlighted the significant difference in creative outputs between ALIA-assisted groups and no-support tool groups. In design practice, this method can be effectively incorporated in structured ideation sessions, where the prompting strategies used in the study can be leveraged in existing LLM providers for higher creative output and diversified concept generation. By leveraging cross-domain analogies guided by synectics and conflict-resolution mechanisms based on dialectical philosophy, this study contributes to theories of human–AI co-creativity by suggesting that generative models can utilise design heuristics for augmenting the ideation process.

Additionally, we observed unexpected, amusing and surprising feedback during the ideation process. Often, participants found a few suggestions amusing and surprising in the given context, leading to laughter and confusion. This observation could be attributed to the probabilistic content-generation process of LLMs and the nature of the synectics process. Synectics prompts expand the conceptual bounds by promoting unexpected associations, while dialectical statements produce tension and lead to the synthesis of ideas. The individual influence of design heuristics and language models on creative performance requires further study. Future research studies can investigate how moments of unexpectedness and surprise triggered by LLM-generated inspirational stimuli impact the creative output of an ideation task.

6.2. Language model benchmarking for creative tasks

There is a considerable difference in the creative performance of different language models, suggesting the need for dedicated creative benchmarking tests. The creative performance of analogies varied across different types of language model architectures. A transformer-based architecture model having a large number of parameters (knowledge learned during training) makes use of all the available parameters for content generation, making it computationally expensive, yet consistent across creative output. Whereas the MoE-based model, where a few “expert” networks are routed through a gating mechanism for content generation, could result in unexpected and creative outputs, as a few specialised experts from diverse domains (sci-fi, romance, science) may be selected for content generation. This nature may be the contributing factor for a slightly better performance of Model 3 in certain situations.

The current scenario of benchmarking in language models highlights a gap between the metrics that are easily measured and those that the end users may actually value. All available models undergo extensive LLM benchmarking tests to evaluate their performance across various tasks, including language skills and reasoning (ARC, HellaSwag), coding (HumanEval, MBPP) and math (GSM8K, MATH). Most benchmarks focus on tasks that generate quantitative metrics and follow an automatic process for evaluation. For instance, MMLU evaluates the LLMs’ problem-solving capabilities across general topics like maths, history and law, consisting of standardised test questions. The quantitative evaluation nature of this test raises questions regarding its validity across real-world use cases where the context varies across diverse domains. This approach is problematic in use cases such as creativity and innovation, where the output quality may be highly subjective, depending on the end users’ contextual background and interpretation. There is a need for qualitative benchmarking techniques of language models in open-ended, multi-step tasks, where the answer quality may be subjective to different users and contexts (Morris Reference Morris2025). The importance of developing benchmarking metrics with ecological validity in real-world use cases is highlighted, which is essential for the development and the ultimate goal of Artificial General Intelligence (AGI) systems.