The long-term legacies of wartime violence are central to understanding why some countries achieve lasting peace while others remain trapped in repeated cycles of conflict. Wartime violence can entrench countries in these cycles, often driven by worsening structural problems and deepening societal polarization. While some nations escape this so-called “conflict trap” (Collier and Sambanis Reference Collier and Sambanis2002; Collier et al. Reference Collier, Elliot, Hegre, Hoeffer, Reynal-Querol and Sambanis2003; Hegre, Nygård, and Ræder Reference Hegre, Nygård and Ræder2017), others remain stuck. What are the legacies of wartime violence? Does exposure to wartime violence erode or strengthen civic and prosocial engagement? Does it generally harden group boundaries and political attitudes? These questions lie at the center of a growing scholarly debate on the consequences of armed conflict for political and social life. Yet the existing literature on these effects remains fragmented and often contradictory, with findings ranging from war-induced altruism to enduring hostility and polarization.

A prior effort to synthesize this literature is the influential meta-analysis by Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Blattman, Chytilová, Henrich, Miguel and Mitts2016). Their study examined the impact of exposure to political violence on prosocial behavior, trust, political interest, and civic and political engagement. Based on 16 eligible papers published up to 2015, they found that wartime violence tended to foster prosociality and cooperation, concluding that “while the human costs of war are horrific, there may at least be some reason for optimism once the violence ends” (272). Despite its important contribution, this early review was necessarily limited in scope and evidentiary base, conducted at a time when the field was still emerging.

Building on this foundation, I offer the most systematic synthesis to date of the attitudinal and behavioral legacies of wartime violence. Using a two-stage individual participant data meta-analysis (IPD-MA), often regarded as the gold standard for evidence synthesis, I harmonize original data from 172 quantitative studies across 154 manuscripts, covering more than 50 countries. This approach enhances measurement consistency and allows for fine-grained comparisons across model specifications, including full (covariate-adjusted), bivariate (zero-order), and quasi-experimental (causal) subsets. I examine 22 outcomes grouped into four domains: (1) civic and political engagement, prosociality, and trust; (2) attitudinal hardening toward wartime enemies; (3) identification with one’s own wartime-aligned group; and (4) generalized attitudinal hardening, such as institutional mistrust or authoritarian values. In contrast to earlier work, this meta-analysis substantially expands both the breadth of outcomes examined and the number of studies included, allowing for a more comprehensive evaluation of the legacies of violence.

The findings reveal a mixed picture for civic and political engagement, prosociality, and trust.Footnote 1 The most consistent positive effects emerge for social group participation, with consistently positive estimates across full, bivariate, and quasi-experimental models. Political participation also shows broadly positive effects, though these are less stable in the quasi-experimental subset. However, while these results suggest that while wartime violence may spur certain forms of engagement, particularly those tied to social networks and mobilization, this engagement does not generalize into greater trust, altruism, or other forms of democratic participation. In this regard, meta-estimates for outcomes such as community leadership, voting, generalized trust, political interest or knowledge, and normative prosociality yield negative, null, or inconsistent effects across specifications. Moderator analyses suggest that self-reported exposure often produces stronger effects than objective measures, pointing to possible recall bias, and publication bias diagnostics indicate that the positive effects for social group participation may be overstated after adjusting for small-study effects. Overall, these findings indicate that the relationship between wartime violence and engagement, trust, and prosociality is less consistent than previously thought.

By comparison, the evidence for attitudinal hardening toward former adversaries and stronger ingroup identification is more consistent. Individuals exposed to wartime violence report significantly higher levels of antagonism toward wartime enemies, heightened perceptions of threat, and increased intergroup distrust or discriminatory behavior. These effects are statistically significant across full and bivariate models and remain largely intact when restricted to quasi-experimental studies. In parallel, wartime exposure is associated with stronger ingroup attachment, reflected in higher levels of group-based voting, expressed identification with one’s wartime-aligned group, and trust in ingroup members. These effects remain positive and statistically significant across most model specifications, including those based on quasi-experimental designs. Moderator and sensitivity analyses confirm that these findings are not substantively affected by exposure measure type, time since conflict, or study design quality. Publication bias tests further indicate that the associations are unlikely to be artifacts of selective reporting. Overall, the results indicate a dual pattern in the attitudinal legacies of violence: simultaneous intensification of outgroup hostility and reinforcement of ingroup solidarity.

Generalized attitudinal hardening, understood as shifts in attitudes toward groups not directly tied to wartime conflict actors, appears weaker and inconsistent. Across all outcomes studied under this category, few systematic effects emerge. Institutional mistrust is the only outcome to reach statistical significance in both full and bivariate models, but the effect is substantively small and disappears in the quasi-experimental subset, likely due to reduced statistical power. All other outcomes produce null or inconsistent estimates across specifications. Moderator analyses do not alter these conclusions, as effects are generally unaffected by study design quality, measurement type, or time since exposure. Publication bias tests also reveal no evidence of systematic inflation of results, and sensitivity analyses confirm that the findings are not driven by outliers or country-specific clusters. These results suggest that even though wartime violence reliably shapes intergroup attitudes and ingroup affiliations, it has limited and context-dependent effects on broader political worldviews.

Taken together, these meta-analyses challenge optimistic perspectives that emphasize the civic benefits of wartime exposure. While exposure to wartime violence can increase certain forms of engagement, such as participation in social groups, this engagement does not necessarily translate into bridging social capital that fosters trust and cooperation across divides. More often, heightened engagement appears alongside intensified outgroup antagonism and stronger ingroup solidarity, patterns that risk reinforcing social boundaries rather than eroding them. The persistence of hardened attitudes toward wartime adversaries long after conflicts end underscores the deep-seated mistrust and hostility that can sustain the “conflict trap” and complicate peacebuilding efforts (Collier and Sambanis Reference Collier and Sambanis2002; Collier et al. Reference Collier, Elliot, Hegre, Hoeffer, Reynal-Querol and Sambanis2003; Hegre, Nygård, and Ræder Reference Hegre, Nygård and Ræder2017).

PRIOR LITERATURE

Early research on the consequences of war focused heavily on economic and health outcomes, with comparatively little attention to social and institutional impacts. In 2010, Blattman and Miguel (Reference Blattman and Miguel2010) described these domains as “the least understood of all war impacts” (42). Since then, the study of wartime violence’s social and political legacies has expanded dramatically, encompassing a wide range of attitudes and behaviors across diverse contexts.

Despite this growth, fundamental questions remain unresolved. Two in particular have generated persistent debate. First, does violence erode the social fabric or foster solidarity and cohesion? Second, does it increase intergroup hostility and political polarization, or can it promote cross-group empathy?

To address the first question, many studies challenged the once-prevailing view of war as exclusively destructive. Beyond physical devastation and loss of life, armed conflict unexpectedly gives rise to prosocial behaviors like altruism. These studies show that exposure to wartime violence has prosocial, pro-participatory effects among victims in disparate settings, such as Uganda (Blattman Reference Blattman2009), Nepal (Gilligan, Pasquale, and Samii Reference Gilligan, Pasquale and Samii2014), or Sierra Leone (Bellows and Miguel Reference Bellows and Miguel2009), even in the longue durée in Vietnam (Barceló Reference Barceló2021). However, others have emphasized how conflict experiences may, if anything, depress social trust in Kosovo (Freitag, Kijewski, and Oppold Reference Freitag, Kijewski and Oppold2019) and community participation in Japan (Harada, Ito, and Smith Reference Harada, Ito and Smith2024), among others.

As for the second question, a growing body of research has examined how exposure to wartime violence shapes intergroup dynamics and political attitudes in post-conflict societies. One of the most frequently discussed findings in this literature is the so-called hardening effect, which defines a tendency for individuals exposed to violence to develop more negative views of outgroups and stronger attachments to their own group (Canavan and Turkoglu Reference Canavan and Turkoglu2023; Grossman, Manekin, and Miodownik Reference Grossman, Manekin and Miodownik2015; Mironova and Whitt Reference Mironova and Whitt2018; Nair and Sambanis Reference Nair and Sambanis2019), although the evidence for this is sometimes ambiguous.Footnote 2

A prominent perspective argues that the hardening effect of wartime violence is specifically directed toward former wartime enemies, exacerbating antagonistic attitudes, hostility, and mistrust toward outgroups associated with the perpetrators. This effect is reflected in outcomes, such as increased antagonism toward former adversaries, intergroup distrust, bias or discrimination, and heightened perceptions of threat from enemy groups (Balcells Reference Balcells2012; Lupu and Peisakhin Reference Lupu and Peisakhin2017), collectively defining the hardening effect toward wartime enemies.

Importantly, this hardening also manifests in another dimension, strengthened identification with and favoritism toward one’s own wartime-aligned group. Rather than purely a negative response toward outgroups, exposure to conflict frequently reinforces ingroup cohesion, resulting in increased trust among ingroup members, greater support for group-aligned political actors (group-based voting), and stronger group identification. While these two dimensions often coexist, they can also operate independently, each differently influencing postwar reconciliation and intergroup relations.

Extending beyond group-specific dynamics, scholars have examined a generalized hardening effect, whereby exposure to wartime violence influences broader political beliefs not limited to wartime enemies. This may include increased support for extreme nationalist or ideological movements that emphasize security and exclusion (Canetti et al. Reference Canetti, Elad-Strenger, Lavi, Guy and Bar-Tal2017; Grossman, Manekin, and Miodownik Reference Grossman, Manekin and Miodownik2015; Zeitzoff Reference Zeitzoff2014), as well as rising mistrust in state institutions (De Juan and Pierskalla Reference De Juan and Pierskalla2016). In some contexts, it may also be linked to heightened hostility toward marginalized or minority groups (Hadzic and Tavits Reference Hadzic and Tavits2021) and a shift toward more authoritarian values (Dyrstad Reference Dyrstad2013).

Yet these patterns are not universal. Some studies have found that experiences of violence can foster greater empathy toward outgroups. Victims have expressed increased support for refugees (Hartman and Morse Reference Hartman and Morse2020), and descendants of displaced persons in Greece and the United States have shown similar openness (Dinas, Fouka, and Schläpfer Reference Dinas, Fouka and Schläpfer2021; Wayne and Zhukov Reference Wayne and Zhukov2022). However, in Israel, the impact of family victimization on outgroup attitudes appears minimal (Wayne, Damann, and Fachter Reference Wayne, Damann and Fachter2023), underscoring the variation in individual and collective responses to past violence.

Overall, the literature highlights important patterns but also reveals fragmentation and contradictions across studies. Thus, a systematic synthesis is needed to adjudicate between competing claims and assess whether effects vary by context or research design, motivating the meta-analytic approach used here to bring together existing evidence in the field.

RESEARCH DESIGN

To provide such a systematic synthesis, I employ a two-stage IPD-MA, often regarded as the gold standard for evidence synthesis (Stewart and Parmar Reference Stewart and Parmar1993). While a standard meta-analysis is “a statistical method for calculating the mean and the variance of a collection of effect sizes across studies” (Plonsky and Oswald Reference Plonsky, Oswald, Mackey and Gass2012, 275), a two-stage IPD-MA uses the original unit-level data rather than only reported study-level estimates. This design improves the precision of overall effects, enhances measurement consistency across studies, allows inclusion of outcomes not reported in the original studies, and provides flexibility in within-study model estimation.

Conducting an IPD-MA involves four essential steps: (1) identification of outcome measures, where researchers define and select specific outcomes from various studies; (2) data collection, compiling unit-level datasets from both published and unpublished research on the relationship of interest; (3) data coding and processing, re-estimating study-specific effect sizes on a common scale to ensure comparability across studies; and (4) model estimation. I will now elaborate on each of these steps.Footnote 3

Outcome Measure Identification

I constructed 22 standardized outcome variables across the studies in the sample. These outcomes capture a wide range of social and political behaviors and attitudes, which I organize into four broad domains for descriptive purposes.Footnote 4 These domains are also commonly understood to reflect distinct underlying mechanisms linking exposure to violence with subsequent responses: (a) civic and political engagement, prosociality, and trust, capturing how violence may reshape orientations toward community and political life; (b) attitudinal hardening toward wartime enemies, where violence can foster antagonism, bias, and perceptions of threat toward former adversaries; (c) strengthening of identification with one’s own wartime-relevant group, reflected in reinforced solidarity, trust, and support for the ingroup; and (d) generalized attitudinal hardening, encompassing broader worldviews that may shift toward skepticism of peace, authoritarian preferences, extreme ideology, institutional mistrust, or intolerance.Footnote 5 What follows is a description of each standardized outcome within its corresponding domain.

Civic and Political Engagement, Prosociality, and Trust

-

1. Altruism. Other-regarding preferences, benevolence, or prosocial dispositions in anonymous, non-strategic contexts, including behaviors, such as hosting refugees or donating money unconditionally. Also captures giving behavior in dictator or public goods games. Typical measures include survey questions, such as “How often do you give money charitably, without expecting anything in return?”, or reported actions, such as “Have you contributed money to a sick family in the past month?”

-

2. Community leadership. Active engagement in leading community mobilization efforts or holding leadership positions within community-based or broader political organizations. Representative measures include survey items, such as “Have you participated in mobilizing your community for collective action in the past year?” or “Are you actively involved in organizing community meetings or activities?”

-

3. Generalized trust. Extent to which individuals perceive others as trustworthy, regardless of their social or ethnic backgrounds. Includes behavior in trust games, reflecting both willingness to trust and beliefs about others’ trustworthiness. A prototypical measure is: “Generally speaking, would you say that most people can be trusted, or that you can’t be too careful in dealing with people?”

-

4. Normative prosociality. Tendency to uphold fairness norms, contribute to collective welfare, and enforce social expectations. In ultimatum games, it reflects acceptance of unequal offers or restraint from punitive rejection; in punishment and reverse dictator games, it aligns with reduced sanctioning or taking behavior.

-

5. Political participation. Engagement or willingness to engage in political activities, such as protests, signing petitions, demonstrations, strikes, or contacting elected representatives. Representative measures include: “Attends political and community meetings regularly” or “Has participated in a peaceful demonstration.”

-

6. Political interest and knowledge. Extent to which one engages with current political issues through discussion or concern, or accurately understands current and historical political topics. Representative survey items include: “How interested would you say you are in politics?” and “How frequently do you discuss politics or current affairs with others?”

-

7. Social group participation. Involvement in civic and social groups, such as community organizations, environmental associations, or sports clubs, measured as the number of groups actively participated in, or through binary membership indicators. A typical measure is: “Are you a member of any civic, social, or community group?”

-

8. Voting. Individual participation in elections, whether a single event or cumulative participation across multiple electoral levels or periods. A typical survey question is: “Did you vote in the last presidential (or general) election?”

Attitudinal Hardening Toward Wartime Enemies

-

9. Antagonism toward wartime enemies. Strength of negative attitudes (e.g., unwillingness to trust) or behaviors (e.g., unwillingness to share post-conflict institutions) toward wartime adversaries. Representative measures include: “How much sympathy do you feel toward members of paramilitary groups involved in the conflict?” or “To what extent do you support the actions of [enemy country or group]?”

-

10. Intergroup distrust, bias, or discrimination. Differential trust or prosocial behavior toward wartime enemies compared to one’s own group, measured through self-reports or behavioral experiments. Examples include differences in dictator-game allocations between coethnic and non-coethnic recipients or gaps in perceptions of trustworthiness between ingroup and outgroup members.

-

11. Perceived threat from wartime enemies. Anxiety or fear regarding conflict resurgence or erosion of post-conflict peace. Typical survey items include: “How fearful are you of demobilized ex-combatants?” or “To what extent do you perceive [enemy country or group] as a threat to your country’s security?”

Ingroup Identification and Favoritism

-

12. Ingroup trust. Extent of trust toward members of one’s wartime-relevant ingroup, captured through attitudinal or behavioral measures. A representative item is the perception that “most coethnics can be trusted.”

-

13. Group-based voting. Voting behavior favoring one’s wartime-aligned group, often via support for group-affiliated political parties. Representative measures include survey items assessing support among Crimean Tatars for Tatar versus non-Tatar politicians, preferences in actual vote-choice scenarios involving real candidates, or conjoint experiments with hypothetical candidates differing in ethnic identity.

-

14. Group identification. Strength of identification, expressed closeness, or support for one’s wartime-aligned social group or related political organizations. Representative measures include questions, such as support for ethnic-based parties, preference of ethnic over national identity, or ranking of ethnic identity as most important.

Generalized Attitudinal Hardening

-

15. Antagonism toward peace. Rejection of peaceful conflict resolution, such as voting against peace referendums or expressing skepticism toward peace agreements, especially when perceived as benefiting wartime adversaries. Representative measures include the reversed scale: “Extent of support for peace talks.”

-

16. Authoritarian or anti-democratic attitudes. Preferences for governance systems other than democratic rule. Representative measures include reversed survey items, such as “Extent of support for democracy as preferable to other forms of government.”

-

17. Extreme ideology. Support for political positions located at ideological extremes, measured by self-placement on ideological scales or voting for parties holding extreme positions (e.g., below 3 or above 8 on a 1–10 ideological scale).

-

18. Hawkish security preferences. Support for strengthened domestic or international security measures, defense alliances, military-focused policies, or prioritization of security over other policy areas. Representative measures include statements, such as “Regards policing as the most important policy issue,” “Supports a robust military solution to post-war security,” or “Believes that defense is paramount.”

-

19. Institutional mistrust. Lack of confidence in formal political institutions, including governments, judicial systems, police, military, or public administration. Typical measures include reversed items, such as “Trusts the [country] government” or “Extent of trust in national or local government.”

-

20. Political intolerance. Unwillingness to respect or extend political rights to members of different groups (e.g., Finkel, Lee, and Humphries Reference Finkel, Lee, Humphries, Robinson, Shaver and Wrightsman1999). Representative measures include reversed items like: “Supports greater rights for minority Albanians,” “Favors government support for minority ethnic groups,” or “Supports extending political rights to Sinhalese.”

-

21. Punitive justice. Support for retributive justice, particularly measures aimed at punishing groups involved in violence, especially in post-conflict contexts. A typical measure is: “Supports more stringent punitive measures against violent groups.”

-

22. Social intolerance. Unwillingness to socially engage with or accept marginalized or minority groups, such as immigrants, women, or same-sex couples. Representative measures include: “Foreign labor should not be allowed to push Danes out of jobs,” “Foreigners should not be able to own land in Denmark,” or reversed items such as “Willingness to support female candidates in elections.”

Data Collection

I sought to collect all manuscripts that studied the relationship between exposure to wartime violence (independent variable), excluding other types of violence, such as terrorism, state repression, or genocide occurring outside the context of warfare—and the social and political outcomes outlined above (dependent variable) among individuals or communities. Section A of the Supplementary Material presents a general overview of the inclusion and exclusion criteria for this meta-analysis.

To gather relevant studies, I issued calls for published and unpublished work through academic networks, such as Twitter, the POLMETH email list, and the APSA Connect forum, and directly contacted scholars in the field.Footnote 6 Additionally, I conducted comprehensive searches of electronic databases using broad search terms and updated the search in July 2022. After merging all lists and removing duplicates, I identified 246 studies—from 225 manuscripts—that met the criteria. I coded various characteristics of these studies using a comprehensive codebook and attempted to obtain the original datasets and replication codes. Ultimately, I was able to obtain the necessary materials for inclusion in the meta-analysis for 172 unique studies derived from 154 different manuscripts.Footnote 7

Data Coding and Standardization

To estimate this causal effect in a way that allows for cross-study comparability, I began by acquiring the original datasets and replication codes from each study and standardizing the variables of interest to align all effect sizes on a common scale.Footnote 8 For the main predictor—exposure to wartime violence—I used each study’s primary indicator, preserving consistency with the authors’ empirical intentions. These measures include self-reported, experimental, and administrative indicators. When studies treated multiple types of violence indicators as equally important, I included each as a distinct variable in the analysis.Footnote 9

To preserve internal validity and remain faithful to the underlying research designs, I first re-analyzed each dataset using the original authors’ preferred model specification. This approach included the authors’ selected control variables, weighting schemes, and methods for clustering standard errors, similar to the replication strategy described by Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Blattman, Chytilová, Henrich, Miguel and Mitts2016). The rationale behind following the authors’ original specifications is that the authors themselves are best positioned to determine the most theoretically and methodologically appropriate model for their empirical context. Respecting these modeling choices, aside from some harmonization to ensure standardization of effect sizes, helps maintain the integrity of each study’s unique contribution, while still enabling cross-study comparability. For consistency across studies, I excluded post-treatment covariates, such as PTSD, psychological distress, or health status.

While manuscripts often report multiple coefficients, I extracted only the coefficient most central to the primary treatment effect. I retained multiple coefficients from a single study only in the following specific cases: (1) when studies examined substantively distinct forms of violence exposure (e.g., self-reported vs. objectively measured indicators); (2) when studies reported results separately for multiple countries, extracting one coefficient per country unless the number of countries exceeded five, in which case results were aggregated; and (3) when studies reported estimates from multiple sample years, extracting one coefficient per year unless the number of years exceeded nine, in which case estimates were combined.

Acknowledging concerns that relying exclusively on original model specifications could yield heterogeneous estimates across studies, I conducted an additional analysis using a simpler and more uniform specification. Specifically, I re-estimated each study’s effects as simple bivariate associations between exposure to wartime violence and the respective social or political outcome. In these analyses, both the predictor and outcome variables were standardized, and no additional control variables were included. This simpler specification removes design-based inference, particularly from quasi-experimental studies, and isolates the zero-order correlation between exposure and outcome. As shown in the main results tables and discussed in the results section, the bivariate estimates closely mirror those from the authors’ original specifications. This convergence is notable, especially given the extensive efforts in this literature to address omitted variable bias and endogeneity through sophisticated modeling. The similarity suggests that the substantive conclusions are robust to model specification and are not driven primarily by covariate or design-based adjustments.

Building on this exercise and consistent with the broader discussion about causal inference in the wartime legacy literature, I conducted an additional subset analysis restricted to studies employing quasi-experimental designs. Specifically, this subset includes studies using difference-in-differences, instrumental variables, regression discontinuity, interrupted time series with exogenous treatment timing, and other design-based sampling strategies.Footnote 10 While quasi-experimental designs constitute only 27.6% of the studies in the meta-analysis, they still cover a substantial range of outcomes. While the number of studies available for some outcomes is limited, which reduces statistical power, the findings from this subset show remarkable consistency with those from the full-model and bivariate analyses. This consistency indicates that variability in observed effect sizes does not appear to depend heavily on research design quality or modeling choices.

Ultimately, the primary estimand in this literature is the average causal effect of exposure to wartime violence on social and political outcomes; a goal pursued, whether explicitly stated or not, by most studies in the field. Yet these studies vary considerably in research design, measurement quality, and identifying assumptions, all of which shape the credibility of their causal claims. Because none rely on randomized assignment, and even the most rigorous quasi-experimental designs remain vulnerable to residual confounding, the field lacks a practical “gold standard” akin to the randomized controlled trials (RCTs) commonly used in medicine or psychology. Ethical and logistical constraints make such trials unfeasible in the study of wartime violence.

Rather than treating studies as either “credible” or “not credible,” it is more useful to situate them along a continuum of causal credibility. At one end of this continuum lies the “ideal experiment,” in Angrist and Pischke’s (Reference Angrist and Pischke2009) terms, which remains a valuable conceptual benchmark even if unattainable in practice. Some studies approximate this ideal more closely through quasi-experimental designs or plausibly exogenous sources of variation, while others depend more heavily on observational strategies that require stronger identifying assumptions. In light of this variation, and in the absence of a single methodological anchor, this meta-analysis adopts an inclusive approach: it synthesizes evidence across the full range of available studies while explicitly accounting for differences in design, measurement, and modeling choices.Footnote 11

To reflect this variation, the analysis reports three types of estimates: (1) full model estimates based on the original authors’ preferred specifications; (2) bivariate estimates that capture zero-order correlations without covariate adjustment; and (3) a restricted set of coefficients from studies using experimental or quasi-experimental designs, which offer stronger causal identification at the cost of reduced statistical power due to smaller samples.

ESTIMATION TECHNIQUE

To estimate the average effect sizes of exposure to violence on social and political outcomes across multiple studies, I employ a three-level random-effects meta-analytic model. This approach is particularly well suited for situations where effect sizes are hierarchically structured. In many cases, multiple estimates are drawn from the same study and are therefore not statistically independent.

Traditional random-effects meta-analysis models account for between study heterogeneity but assume that each effect size is independent. This assumption is often violated in practice. Many studies contribute more than one effect size to a meta-analysis, either because multiple outcomes were measured, different methods were used, or estimates were derived from the same sample under varying specifications. In this project, I limited the inclusion of coefficients to those favored by the study authors, rather than using all reported results. Nevertheless, dependencies still arise, particularly in the three scenarios described in the previous section that led to the extraction of multiple coefficients from a single study. As a result, these within-study correlations must be appropriately modeled.

In this equation, y

ij

represents the observed effect size i from study j, and μ denotes the overall average effect size across all studies. The term u

j

∼

![]() $ \mathcal{N} $

(0, τ

2) captures the random effect at the study level, accounting for between-study variance. The component w

ij

∼

$ \mathcal{N} $

(0, τ

2) captures the random effect at the study level, accounting for between-study variance. The component w

ij

∼

![]() $ \mathcal{N} $

(0, σ

2) reflects the variability between effect sizes within the same study. Finally, ϵ

ij

∼

$ \mathcal{N} $

(0, σ

2) reflects the variability between effect sizes within the same study. Finally, ϵ

ij

∼

![]() $ \mathcal{N} $

(0, s

ij

2) represents the sampling error associated with each individual effect size.

$ \mathcal{N} $

(0, s

ij

2) represents the sampling error associated with each individual effect size.

$ {y}_{ij}=\mu +{u}_j+{w}_{ij}+{\varepsilon}_{ij},{u}_j\sim \mathcal{N}(0,{\tau}^2),\ {w}_{ij}\sim \mathcal{N}(0,{\sigma}^2),\ {\varepsilon}_{ij}\sim \mathcal{N}(0,{s}_{ij}^2). $

$ {y}_{ij}=\mu +{u}_j+{w}_{ij}+{\varepsilon}_{ij},{u}_j\sim \mathcal{N}(0,{\tau}^2),\ {w}_{ij}\sim \mathcal{N}(0,{\sigma}^2),\ {\varepsilon}_{ij}\sim \mathcal{N}(0,{s}_{ij}^2). $

For robustness, I also estimate a two-level random-effects model. While the fixed-effects model assumes all studies estimate the same true effect size (with observed variation due only to sampling error), the two- and three-level random-effects models allow for heterogeneity across studies, and in the three-level model, also within studies.

In sum, the three-level random-effects model is my preferred specification, as it most appropriately reflects the nested structure of the data, accounts for both within- and between-study heterogeneity, and provides a more realistic estimate of the average effect of exposure to violence across contexts and study designs.

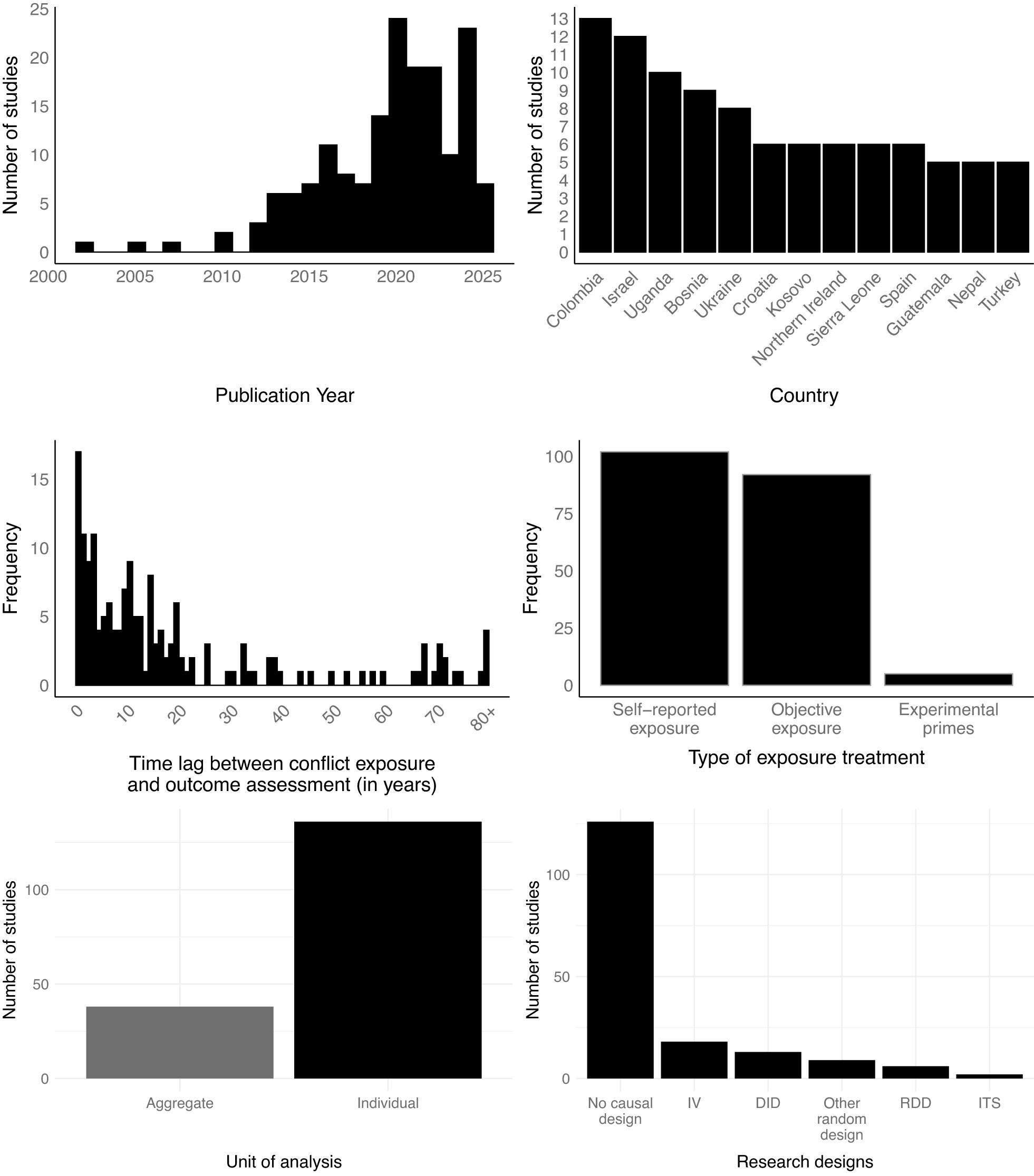

Existing Studies in the Field

Having collected a comprehensive body of literature on the attitudinal and behavioral consequences of violence, I now highlight gaps in our knowledge of the field. Figure 1 provides descriptive visualizations that summarize the number of studies by country, year of publication, type of exposure or treatment, outcome assessment strategies, time elapsed between exposure and measurement, and the research designs employed.

Figure 1. Descriptive Overview of Studies on the Attitudinal and Behavioral Consequences of Wartime Violence

Note: Panels display: (top left) number of published studies by year; (top right) geographic distribution of study cases; (middle left) distribution of time lags between violence exposure and outcome measurement; (middle right) types of exposure or treatments examined; (bottom left) unit of analysis of outcomes assessed; and (bottom right) research designs employed.

The top-left panel of Figure 1 illustrates the field’s growth, as evidenced by a steady increase in publications since 2001. The earliest study for which replication materials were obtained is Hayes and McAllister (Reference Hayes and McAllister2001), which examined the impact of political violence on attitudes toward warring parties in Northern Ireland. The field gained significant momentum following the publication of studies by Bellows and Miguel (Reference Bellows and Miguel2006; Reference Bellows and Miguel2009) on Sierra Leone and Blattman (Reference Blattman2009) on Northern Uganda. These studies identified a then-unexpected positive relationship between wartime exposure and civic or political engagement, prompting substantial interest from both political scientists and economists. Building on this foundation, Balcells (Reference Balcells2012) extended the analysis of the legacies of violence to the Spanish Civil War, contributing to a shift in focus toward political attitudes, identities, and behaviors. Since 2012, there has been a notable rise in publications, reflecting growing interest and greater research activity in the field.Footnote 12

While the rise in the number of studies is undeniable, it has not been geographically uniform. As in many areas of research, scholars have clustered around certain countries and neglected others. The top right panel of Figure 1 shows that research efforts are concentrated in a few cases—Colombia, Israel, Uganda, Bosnia, and Ukraine are the most studied—with the top ten countries accounting for more than 47 percent of all studies.

Several factors may explain the uneven geographic concentration of research efforts observed in the literature. To better understand what drives scholars to study specific countries more intensively, I estimated regression models on all conflict episodes active for at least one year since 1989 (detailed in Section E of the Supplementary Material). The analyses reveal that conflicts characterized by longer durations and higher numbers of total battle deaths attract significantly greater research attention. Additionally, conflicts in English-speaking countries or regions tend to be studied more extensively, likely due to greater accessibility for international researchers, availability of English-language data, and fewer barriers to fieldwork. Conversely, conflicts in regions such as Africa and Asia remain systematically understudied, even after accounting for conflict intensity and duration. This disparity likely reflects logistical constraints, security risks, and limited research infrastructure rather than theoretical irrelevance.

Figure E.2 in the Supplementary Material further illustrates these trends by plotting residuals from the regression models, highlighting countries studied more or less than predicted based solely on conflict characteristics, such as type, duration, total casualties, and time since the last conflict event. The analysis reveals that conflicts like the Colombian Armed Conflict, European conflicts, including the Troubles in Northern Ireland, post-Yugoslav wars (e.g., the Croatian and Kosovo wars), the Russo–Ukrainian conflict, and the Israeli–Palestinian conflict are notably overrepresented relative to their conflict severity and duration. Conversely, numerous significant conflict episodes remain underrepresented, particularly those in some of the poorest African countries, such as the Angolan and Somali Civil Wars, as well as conflicts in Algeria, the Philippines, and India’s Maoist/Naxalite conflict. These conflicts have caused substantial casualties over extended periods yet have received disproportionately little scholarly attention.

Beyond mapping patterns of research attention, this analysis also provides a window into the broader structure of knowledge production in political science and related fields. It shows how conflict research has been shaped not only by theoretical interest or humanitarian concern, but also by institutional access, linguistic alignment, and global academic hierarchies. This meta-analytic lens thus contributes not only to our understanding of wartime violence but also to ongoing discussions about the geography, selectivity, and representativeness of empirical social science. The pronounced imbalance documented here highlights a critical limitation in the existing literature and underscores the need for a more inclusive and geographically diverse research agenda to enhance the generalizability and policy relevance of findings.

Turning to the temporal dimension, the middle-left panel of Figure 1 examines the distribution of time lags between conflict exposure and outcome assessment. The literature reveals substantial variation: some studies measure outcomes as soon as 15 days after exposure, while others examine effects centuries later, as in Ochsner and Roesel (Reference Ochsner and Roesel2024), which investigates the legacy of violence more than 400 years after the event. Despite this wide range, the median time lag is 11 years. The interquartile range shows that half of the studies assess outcomes between 4 and 22 years after exposure, indicating a predominant focus on effects measured within the first two decades. Notably, only 26.7% of studies explore very long-term consequences beyond 20 years.

Methodologically, the literature exhibits a near even split between studies that rely on self-reported individual experiences of violence (51.2%) and those that use objectively measured indicators from administrative or secondary sources (46.2%), with only a small fraction (2.5%) employing experimental manipulations. Furthermore, as shown in the bottom left panel of Figure 1, most analyses are conducted at the individual level (78.2%), while a smaller share (21.8%) examines outcomes at more aggregate levels. Importantly, the literature shows a consistent effort to address the inferential challenges of identifying the causal effect of violence—most obviously, the problem of self-selection into victimization. While most studies rely on observational data, a substantial portion employs quasi-experimental approaches. In total, studies with an identifiable causal design represent 27.6% of the studies in the sample, with instrumental variable and difference-in-differences designs being the most common strategies used to strengthen causal claims.Footnote 13

These patterns not only highlight both the progress made and the limitations that remain, pointing to areas where future research can broaden its scope. Furthermore, the heterogeneity in country coverage, study design, and temporal focus also illustrates how the meta-analytic conclusions presented here are shaped by what scholars have chosen to study—and, just as importantly, what they have not. The current body of research pools evidence from diverse conflict settings, that span different types of cleavages, intensities, durations, and geographic regions. To assess whether this diversity systematically conditions the estimated effects, I report a series of moderator analyses. These models examine variation in outcomes based on conflict characteristics such as type of violence, cleavage structure, and time since exposure and study characteristics such as unit of analysis and use of self-reported versus objective exposure measures. While most of these moderators are statistically insignificant and do not substantively alter the overall findings, some exceptions exist. I discuss those exceptions in greater detail in the results section that follows.

RESULTS

Figure 2 presents the results of eight separate meta-analyses, each estimating the effect of wartime violence on a separate outcome related to social or political engagement, prosocial behavior, or generalized trust. Together the analyses incorporate 358 coefficient estimates from 112 unique studies, though the number of contributing studies varies by outcome. Each meta-analysis employs a three-level random-effects model, which accounts for the nesting of multiple estimates within studies and produces an average effect size for each outcome. For every outcome, results are presented under three model specifications: covariate-adjusted models (“full models,” shown in red), bivariate associations between violence and the outcome (blue), and a restricted set including only estimates from quasi-experimental or experimental designs (green). Each point in the figure represents a study-level estimate from the full regression model, while each “X” represents a corresponding estimate from the bivariate association, with sizes proportional to the inverse of their standard errors to reflect precision and relative weight in the pooled analysis.

Figure 2. The Effects of Wartime Violence on Civic and Political Engagement, Prosociality, and Trust Outcomes

Note: k refers to the number of individual coefficients; N refers to the number of unique studies represented in each outcome. All refers to all studies in the dataset and QE refers to estimates resulting from employing experimental or quasi-experimental designs. Outcomes are ordered by the magnitude of the effect in the full models. Significance levels: *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

, and ***

$ p<0.01 $

, and ***

![]() $ p<0.001 $

.

$ p<0.001 $

.

Exposure to wartime violence yields the most consistently positive findings for social group participation, with supportive, though less consistent, evidence for political participation and community leadership. Social group participation shows the most robust pattern, with standardized effects of

![]() $ 0.07 $

(p < 0.01) in the full models and

$ 0.07 $

(p < 0.01) in the full models and

![]() $ 0.08 $

(p < 0.01) in the bivariate models, based on 58 coefficients from 43 unique studies. This effect remains statistically significant and similar in magnitude (0.07, p < 0.05) when the analysis is restricted to 12 studies using quasi- or fully experimental designs. Similarly, political participation also shows broadly positive effects, with identical estimates of

$ 0.08 $

(p < 0.01) in the bivariate models, based on 58 coefficients from 43 unique studies. This effect remains statistically significant and similar in magnitude (0.07, p < 0.05) when the analysis is restricted to 12 studies using quasi- or fully experimental designs. Similarly, political participation also shows broadly positive effects, with identical estimates of

![]() $ 0.06 $

(p < 0.01) in both the full and bivariate models from 33 coefficients across 23 studies. However, the effect falls to

$ 0.06 $

(p < 0.01) in both the full and bivariate models from 33 coefficients across 23 studies. However, the effect falls to

![]() $ 0.04 $

and becomes not significant (

$ 0.04 $

and becomes not significant (

![]() $ p=0.29 $

) in the nine quasi-experimental studies. Evidence for community leadership is weaker and based on fewer studies, 11 in total contributing 14 coefficients, with a significant effect emerging only in the bivariate model (0.07, p < 0.05), whereas estimates from the full and quasi-experimental models (based on five studies and seven coefficients) are smaller and not statistically significant.

$ p=0.29 $

) in the nine quasi-experimental studies. Evidence for community leadership is weaker and based on fewer studies, 11 in total contributing 14 coefficients, with a significant effect emerging only in the bivariate model (0.07, p < 0.05), whereas estimates from the full and quasi-experimental models (based on five studies and seven coefficients) are smaller and not statistically significant.

Other outcomes exhibit more modest or null effects. For altruism, estimates are marginally significant and positive in both the original (0.05,

![]() $ p=0.06 $

) and bivariate (0.04,

$ p=0.06 $

) and bivariate (0.04,

![]() $ p=0.06 $

) models, but become negative and statistically insignificant when the analysis is restricted to quasi-experimental designs. Similarly, interest in politics or political knowledge shows a marginally significant effect in the original specification (

$ p=0.06 $

) models, but become negative and statistically insignificant when the analysis is restricted to quasi-experimental designs. Similarly, interest in politics or political knowledge shows a marginally significant effect in the original specification (

![]() $ 0.05 $

,

$ 0.05 $

,

![]() $ p=0.09 $

), yet remains non-significant in both the bivariate and quasi-experimental subsamples. By contrast, voting and generalized trust yield consistently null effects across all model types: point estimates hover near zero, and confidence intervals include the null. These findings draw on 57 studies (101 coefficients) for voting—including 19 studies (46 coefficients) using quasi-experimental methods—and 43 studies (66 coefficients) for generalized trust, of which 10 studies (17 coefficients) are quasi-experimental. Finally, for normative prosociality, results indicate a substantively negative association with wartime violence: effect estimates are −0.09 in the full model and −0.06 in the bivariate model, both marginally significant at the 90% confidence level, yet these effects rely on only 10 studies, and the absence of quasi-experimental studies for this outcome limits the robustness of this finding.Footnote

14

$ p=0.09 $

), yet remains non-significant in both the bivariate and quasi-experimental subsamples. By contrast, voting and generalized trust yield consistently null effects across all model types: point estimates hover near zero, and confidence intervals include the null. These findings draw on 57 studies (101 coefficients) for voting—including 19 studies (46 coefficients) using quasi-experimental methods—and 43 studies (66 coefficients) for generalized trust, of which 10 studies (17 coefficients) are quasi-experimental. Finally, for normative prosociality, results indicate a substantively negative association with wartime violence: effect estimates are −0.09 in the full model and −0.06 in the bivariate model, both marginally significant at the 90% confidence level, yet these effects rely on only 10 studies, and the absence of quasi-experimental studies for this outcome limits the robustness of this finding.Footnote

14

Taken together, the modest positive evidence for outcomes related to engagement, most notably social group participation, and to a lesser extent political participation and community leadership, invites at least two contrasting interpretations. On the one hand, individuals exposed to wartime violence may become more actively involved in rebuilding community structures and reinforcing social networks, thereby contributing to postwar recovery and collective resilience. On the other hand, this increased engagement may reflect a retreat into in-group solidarity, where participation is mobilized against former adversaries and contributes to heightened out-group hostility. In such contexts, engagement may strengthen bonding rather than bridging social capital, limiting its potential to foster trust and cooperation across divided communities.

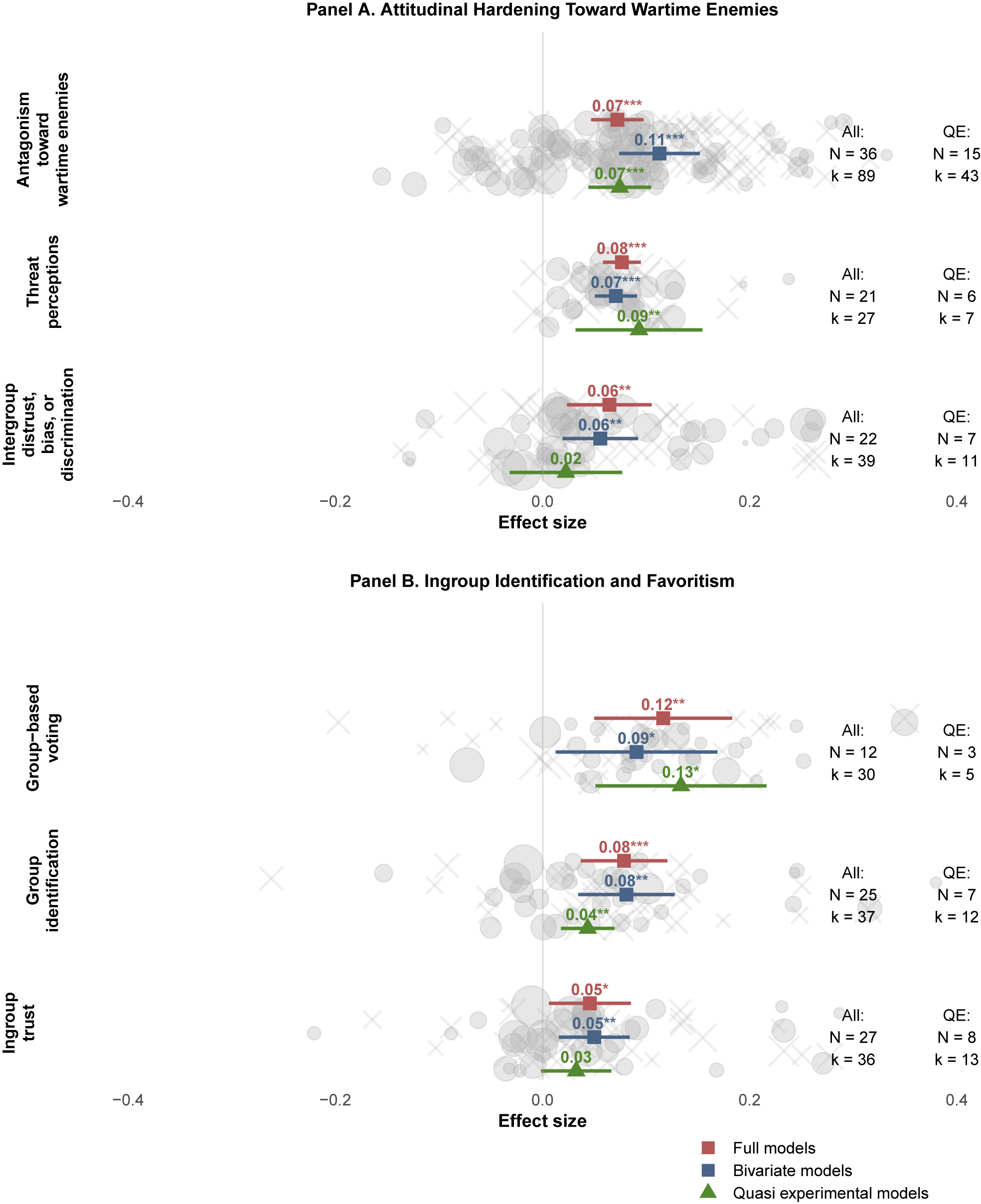

To explore these alternative interpretations more directly, Figure 3 examines the effects of wartime violence in two related domains: attitudinal hardening toward wartime enemies and increased identification or favoritism toward one’s own group. Panel A focuses on the former, analyzing how exposure influences antagonism, perceived threat, and intergroup distrust. Across outcomes, the analyses incorporate 155 coefficient estimates from 64 unique studies, although the number of contributing studies varies by outcome.

Figure 3. Effects of Wartime Violence on Hardening Attitudes Toward Wartime Enemies and Identification with One’s Own Wartime-Aligned Group

Note: k refers to the number of individual coefficients; N refers to the number of unique studies represented in each outcome. Outcomes are ordered by the magnitude of the effect in the full models. Significance levels: *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

, and ***

$ p<0.01 $

, and ***

![]() $ p<0.001 $

.

$ p<0.001 $

.

The results reveal a clear and consistent pattern: individuals exposed to wartime violence hold significantly more negative attitudes toward groups associated with former adversaries. This pattern appears consistently across three indicators. First, exposure is associated with increased antagonism toward wartime enemies, with standardized effect sizes of

![]() $ 0.07 $

(p < 0.001) in full models and

$ 0.07 $

(p < 0.001) in full models and

![]() $ 0.11 $

(p < 0.001) in bivariate models (89 coefficients across 36 studies). This association remains statistically significant (

$ 0.11 $

(p < 0.001) in bivariate models (89 coefficients across 36 studies). This association remains statistically significant (

![]() $ 0.07 $

,

$ 0.07 $

,

![]() $ p<0.01 $

) even when restricted to quasi-experimental designs. Second, individuals report heightened perceptions of threat from adversaries, with effect sizes of

$ p<0.01 $

) even when restricted to quasi-experimental designs. Second, individuals report heightened perceptions of threat from adversaries, with effect sizes of

![]() $ 0.08 $

(p < 0.001) in the original models and

$ 0.08 $

(p < 0.001) in the original models and

![]() $ 0.07 $

(

$ 0.07 $

(

![]() $ p<0.001 $

) in bivariate models (27 coefficients across 21 studies). Among the six quasi-experimental studies contributing seven estimates, the effect remains similar (

$ p<0.001 $

) in bivariate models (27 coefficients across 21 studies). Among the six quasi-experimental studies contributing seven estimates, the effect remains similar (

![]() $ 0.09 $

,

$ 0.09 $

,

![]() $ p<0.01 $

). Third, respondents demonstrate greater intergroup distrust, bias, or discriminatory attitudes, though with somewhat smaller effect sizes (

$ p<0.01 $

). Third, respondents demonstrate greater intergroup distrust, bias, or discriminatory attitudes, though with somewhat smaller effect sizes (

![]() $ 0.06 $

in both full and bivariate models,

$ 0.06 $

in both full and bivariate models,

![]() $ p<0.05 $

; 39 coefficients across 22 studies). This is the only outcome where the quasi-experimental evidence diverges from the broader pattern; the effect reduces to

$ p<0.05 $

; 39 coefficients across 22 studies). This is the only outcome where the quasi-experimental evidence diverges from the broader pattern; the effect reduces to

![]() $ 0.02 $

and is no longer statistically significant, possibly reflecting methodological or sample-size limitations. Overall, the magnitude of these effects aligns closely with meta-analytic estimates from related literature. For instance, bivariate standardized effect sizes for outgroup hostility in terrorism exposure range between 0.09 and 0.13 (Godefroidt Reference Godefroidt2023), comparable to the bivariate estimates observed here (ranging from 0.06 to 0.11).Footnote

15

$ 0.02 $

and is no longer statistically significant, possibly reflecting methodological or sample-size limitations. Overall, the magnitude of these effects aligns closely with meta-analytic estimates from related literature. For instance, bivariate standardized effect sizes for outgroup hostility in terrorism exposure range between 0.09 and 0.13 (Godefroidt Reference Godefroidt2023), comparable to the bivariate estimates observed here (ranging from 0.06 to 0.11).Footnote

15

In parallel, panel B draws on 103 coefficient estimates from 45 unique studies to assess the effects of wartime violence on ingroup identification and favoritism. The results also reveal a consistent pattern: individuals exposed to violence report significantly stronger alignment with ingroup members across several indicators. Group-based voting behavior displays the strongest associations, with estimated effects of

![]() $ 0.12 $

(

$ 0.12 $

(

![]() $ p<0.001 $

) in the full models and

$ p<0.001 $

) in the full models and

![]() $ 0.09 $

(

$ 0.09 $

(

![]() $ p<0.05 $

) in the bivariate model (30 coefficients across 12 studies). However, quasi-experimental evidence for this outcome is more limited—five estimates from three studies—although the effect is relatively large (

$ p<0.05 $

) in the bivariate model (30 coefficients across 12 studies). However, quasi-experimental evidence for this outcome is more limited—five estimates from three studies—although the effect is relatively large (

![]() $ 0.13 $

) and statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. Similarly, exposure to wartime violence consistently strengthens identification with one’s own group by a standardized effect size of

$ 0.13 $

) and statistically significant at the 95% confidence level. Similarly, exposure to wartime violence consistently strengthens identification with one’s own group by a standardized effect size of

![]() $ 0.08 $

(p < 0.001) both using original authors’ full and bivariate models (37 coefficients across 25 studies), an effect that remains statistically significant among quasi-experimental studies, though smaller in magnitude (

$ 0.08 $

(p < 0.001) both using original authors’ full and bivariate models (37 coefficients across 25 studies), an effect that remains statistically significant among quasi-experimental studies, though smaller in magnitude (

![]() $ 0.04 $

,

$ 0.04 $

,

![]() $ p<0.01 $

; 12 coefficients across seven studies). Lastly, for ingroup trust, the estimated effect is

$ p<0.01 $

; 12 coefficients across seven studies). Lastly, for ingroup trust, the estimated effect is

![]() $ 0.05 $

(

$ 0.05 $

(

![]() $ p<0.05 $

) in the estimate using the full models and

$ p<0.05 $

) in the estimate using the full models and

![]() $ 0.05 $

(p < 0.01) using the bivariate models, based on 36 coefficients across 27 studies. This association persists, albeit slightly attenuated, in the quasi-experimental subsample (

$ 0.05 $

(p < 0.01) using the bivariate models, based on 36 coefficients across 27 studies. This association persists, albeit slightly attenuated, in the quasi-experimental subsample (

![]() $ 0.03 $

,

$ 0.03 $

,

![]() $ p<0.10 $

; 13 coefficients across eight studies).Footnote

16

$ p<0.10 $

; 13 coefficients across eight studies).Footnote

16

Overall, these findings indicate that exposure to wartime violence significantly shapes long-term social attitudes by simultaneously reinforcing ingroup cohesion and exacerbating outgroup antagonism. Individuals who experience violence consistently report more negative attitudes toward former adversaries and stronger identification with their own group. This dual pattern, heightened animosity toward outgroups alongside increased ingroup trust and favoritism, suggests that wartime exposure tends to solidify social boundaries rather than bridge them, potentially undermining efforts at post-conflict reconciliation and broader societal cohesion.

Turning to outcomes that capture more generalized forms of attitudinal hardening not explicitly directed at wartime adversaries, Figure 4 summarizes results across eight such outcomes. The analyses draw on 313 coefficients from 108 unique studies and reveal a pattern that is largely null and inconsistent. Among the eight outcomes analyzed, namely authoritarian attitudes, institutional mistrust, hawkish security preferences, political intolerance, social intolerance, support for punitive justice, extreme ideology, and antagonism toward peace,Footnote 17 only institutional mistrust shows any statistically significant relationship. In this case, exposure to wartime violence is marginally associated with increased mistrust in the full models (significant at the 90% confidence level) and reaches statistical significance in the bivariate models (significant at the 95% level), based on evidence from 44 studies contributing 73 coefficients. However, when restricting the analysis to quasi-experimental designs, the effect size remains similar but is no longer statistically significant, likely reflecting the smaller sample size (14 studies, 20 coefficients). These findings suggest that, with few exceptions, wartime violence does not systematically harden attitudes in domains unrelated to the wartime outgroup.Footnote 18

Figure 4. Effects of Wartime Violence on Generalized Attitudinal Hardening

Note: k refers to the number of individual coefficients; N refers to the number of unique studies represented in each outcome. Outcomes are ordered by the magnitude of the effect in the full models. Significance levels: *

![]() $ p<0.05 $

, **

$ p<0.05 $

, **

![]() $ p<0.01 $

, and ***

$ p<0.01 $

, and ***

![]() $ p<0.001 $

.

$ p<0.001 $

.

Moderator Analysis

To better understand variation in the effects of wartime violence on prosociality, intergroup dynamics, and generalized attitudes, I conducted moderator analyses examining five key factors: the measurement type of violence exposure, the nature of the conflict cleavage (territorial versus government incompatibility), study design quality, the time elapsed since exposure, and the unit of analysis (individual versus aggregate). Each moderator helps to identify specific conditions that might strengthen, weaken, or alter the observed relationships (full details in Section F of the Supplementary Material).

Overall, most results were robust across different moderator conditions, highlighting consistency in key findings, especially regarding intergroup dynamics. However, notable exceptions emerged concerning the measurement type of exposure: for several engagement and attitudinal outcomes, including social group participation, community leadership, and normative prosociality, effects were significantly larger when exposure was self-reported rather than objectively measured, raising concerns about recall biases inflating some positive results. By contrast, outcomes related to attitudes toward wartime enemies and ingroup favoritism remained consistent irrespective of measurement strategies, reinforcing the conclusion that wartime violence reliably intensifies ingroup attachment and outgroup hostility.

Other moderators showed few systematic effects. The nature of the conflict cleavage rarely moderated outcomes, except for exposure to violence from territorial conflicts, which produced stronger intergroup distrust, bias, and discrimination. Similarly, variations in study design quality, time since exposure, and unit of analysis generally had minimal influence, reinforcing the robustness of the main conclusions. A few isolated exceptions appeared, such as higher effects of violence exposure on political intolerance in the medium-term post-conflict period. However, these exceptions are typically driven by a single or very few observations and, overall, do not substantially alter the core findings.

Publication Bias

To formally assess potential publication bias, I conducted several diagnostic tests adapted to the hierarchical, three-level structure of the data. First, I applied the p-curve method to examine the distribution of significant p-values, helping to distinguish genuine effects from those influenced by selective reporting. Second, I employed Egger’s regression test with clustered standard errors to detect funnel plot asymmetry, indicative of potential publication bias. Finally, I used Rücker’s Limit Meta-Analysis to adjust estimates for possible small-study effects (full details in Section G of the Supplementary Material).

Overall, it is reassuring to find only limited evidence of systematic publication bias in this emerging literature. Specifically, p-curve analyses consistently indicated right-skewed distributions, suggesting that significant findings generally represent genuine relationships rather than biased reporting practices. Nevertheless, Egger’s test revealed funnel plot asymmetry for 4 of the 22 outcomes in the full models—social groups participation, attitudes toward wartime enemies, ingroup trust, and group identification. Importantly, this asymmetry did not emerge in the bivariate models and appeared only for social groups participation in the quasi-experimental models.Footnote 19

Applying Rücker’s correction resulted in modest reductions in several effect sizes. Most notably, after adjustment, the effect on social groups participation remained positive but was no longer statistically significant in both the full and quasi-experimental models. Likewise, the effect on group identification lost statistical significance in the full model, although it remained positive; while continuing to be both positive and statistically significant in the bivariate model. However, the effects on attitudes toward wartime enemies and ingroup trust remained robust, positive, and statistically significant across all model specifications. Thus, the primary conclusion, that exposure to wartime violence intensifies both outgroup hostility and ingroup attachment, remains largely unaltered.

Sensitivity Analysis

To further evaluate the robustness of my main findings, I conducted sensitivity analyses that systematically excluded observations characterized by extreme effect sizes, high variances, and disproportionate representation from specific countries. Specifically, I removed estimates exceeding the 90th percentile for absolute effect size and variance within each outcome category, and I also re-estimated models excluding data from the most frequently studied country for each outcome. These additional checks help determine whether any single study or subgroup disproportionately influences the overall conclusions (full details in Section I of the Supplementary Material).

The results largely confirmed the robustness of the core findings. Civic and political engagement outcomes, particularly social group participation and political participation, generally retained their significance and direction, though the quasi-experimental evidence showed less reliability. Attitudinal hardening toward wartime enemies and ingroup favoritism effects were remarkably stable, consistently remaining positive and significant across almost all specifications and subsamples. In contrast, generalized attitudinal hardening outcomes mostly remained null or inconsistent, underscoring that the primary conclusions, especially regarding strengthened ingroup identification and increased hostility toward wartime adversaries, seem to be robust to exclusions of outliers in effect size, precision, or predominance of a country evidence.

CONCLUSION

The study of how wartime violence shapes social and political attitudes has advanced considerably over the past decade. An earlier meta-analysis by Bauer et al. (Reference Bauer, Blattman, Chytilová, Henrich, Miguel and Mitts2016) offered a cautiously optimistic view, suggesting that war can foster participatory, prosocial, and cooperative behaviors. Yet their conclusions were necessarily tentative, constrained by a limited evidence base and a focus primarily on within-group dynamics.

Building on this foundation, the present meta-analysis substantially broadens the scope, reviewing 172 studies across 154 manuscripts, and incorporating a wider range of outcomes, including not only prosocial behavior but also group dynamics, social identities, and political attitudes. This expanded examination provides a more comprehensive understanding of the diverse ways in which wartime experiences shape post-conflict social and political life.

These findings introduce a note of caution to earlier optimistic interpretations. While exposure to wartime violence is associated with greater participation in civic organizations, community leadership, and non-electoral political engagement, it does not enhance generalized trust, voting behavior, or altruism. This pattern suggests that heightened engagement may reflect greater mobilization around identity-based or divisive issues rather than broad-based social cohesion. Moreover, the analysis indicates that the association between violence exposure and civic engagement is sensitive to modeling assumptions, weaken when limiting to quasi-experimental designs, and may be inflated by publication bias. Once these factors are accounted for, many positive effects become indistinguishable from zero.

More consistently, the evidence shows that wartime violence intensifies negative attitudes toward former enemies while reinforcing identification with one’s own group. This attitudinal hardening manifests across several indicators: rejection of groups tied to former wartime adversaries, heightened threat perceptions toward wartime enemies, and increased intergroup mistrust, bias, and discrimination. At the same time, individuals exposed to violence report higher ingroup trust, stronger group identification, and a higher likelihood of voting for group-affiliated parties. Together, these findings reveal a core pattern: wartime violence deepens social divides and strenghtens group polarization, posing a serious obstacle to reconciliation and sustainable peace.

Importantly, these hardened attitudes are durable. Across studies, the effects persist long after the conflict has ended, with little evidence of attentuation over time. Moderator analyses show limited variation by conflict type or methodological features, suggesting that the social and political consequences of wartime exposure are broadly consistent across diverse contexts. Notably, however, these effects do not appear to generalize to social groups or institutions unrelated to the original conflict, indicating a small but meaningful boundary to the reach of attitudinal hardening.

Taken together, the findings lend support to the “conflict trap” hypothesis (Collier and Sambanis Reference Collier and Sambanis2002; Collier et al. Reference Collier, Elliot, Hegre, Hoeffer, Reynal-Querol and Sambanis2003; Hegre, Nygård, and Ræder Reference Hegre, Nygård and Ræder2017). Exposure to wartime violence appears to entrench societal divisions and perpetuate patterns of hostility, rather than fostering the kinds of trust and cooperation necessary for stable postwar governance. While some forms of engagement do increase, they are unlikely to translate into broader prosocial behavior or bridging social capital. Instead, the data suggest that violence reinforces ingroup solidarity while fueling outgroup antagonism, making the transition to post-conflict reconciliation more difficult.

This meta-analysis also exposes significant gaps in the literature. Research remains heavily concentrated in a handful of countries, such as Colombia, Israel, Uganda, Bosnia, Northern Ireland, and Ukraine, many of which have received disproportionately high levels of scholarly attention relative to the duration and intensity of the conflicts. In contrast, other conflict episodes, particularly those occurring in harder-to-reach regions or in settings with greater research barriers, remain underrepresented in the existing evidence base. This imbalance raises concerns about the generalizability of the findings and underscores the need for future research to address geographic gaps. Although no significant differences emerged based on the time elapsed since exposure, the limited number of studies examining very long-term effects constrains the confidence of this conclusion. Encouragingly, publication bias appears modest: while some outcomes show signs of selective reporting, the core findings remain robust across specifications.

Beyond these geographic and temporal imbalances, the analysis also illustrates the broader challenge of cumulating knowledge in a field where most studies are rooted in specific historical and geographical contexts. As Kalyvas has noted, research on political violence often suffers from “myopic microinvestigations” that provide persuasive evidence for particular mechanisms but struggle to specify how findings generalize and cumulate across settings (Kalyvas Reference Kalyvas2025, 266–7). Individual papers may identify credible effects within their scope, yet the boundaries of those effects often remain unclear, complicating their contribution to larger theoretical debates. Meta-analysis helps overcome this limitation by pooling results across diverse cases, allowing researchers to move from context-specific findings toward more generalizable patterns. At the same time, the heterogeneity uncovered in this study cautions that null or inconsistent findings in the aggregate do not imply that violence is inconsequential; rather, its influence may be strong in some contexts, absent in others, and even operate in opposite directions depending on local mechanisms. This variation cautions against making broad, generalizable causal claims from single studies, however well-identified, and demonstrates the value of meta-analytic synthesis for distinguishing contextual effects from systematic regularities.

Finally, these findings carry direct policy implications for investment decisions, program design, and the prioritization of peacebuilding initiatives in post-conflict settings. For institutions, such as the World Bank and other development agencies (Holtzman, Elwan, and Scott Reference Holtzman, Elwan and Scott1998), a clear understanding of the psychological, political, and social legacies of violence is essential for crafting effective interventions. Investments should extend beyond rebuilding to directly address the deep-seated mistrust and hostility that persist after conflict. Projects must intentionally promote social cohesion, support reconciliation processes, and reduce perceived threats from former adversaries. Peacebuilding initiatives should therefore prioritize activities that soften hardened attitudes and bridge divides between former enemies. By integrating these insights into post-conflict recovery planning, policymakers can allocate resources more strategically, design more impactful interventions, and create conditions more conducive to durable peace.

In conclusion, while the human costs of war are undisputed, this meta-analysis shows that wartime violence tends to deepen social divisions rather than promote inclusive cohesion. These findings carry important implications for post-conflict reconstruction and peacebuilding: effective interventions must go beyond physical rebuilding to confront entrenched animosities, reduce polarization, and foster reconciliation. Achieving lasting peace will require sustained efforts not only to repair what has been destroyed but also to mend the fractured social fabric of war-affected communities.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/S0003055425101299.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the American Political Science Review Dataverse: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/BPVYFD. The underlying dataset can also be explored through an interactive Shiny app (https://joanbarcelosoler.shinyapps.io/wartime_effects_metaanalysis/). The app also includes a simple tool that lets users enter results from their own analyses, using exposure to wartime violence as the predictor and any of our outcomes as the dependent variable, to see where their estimates fall relative to the meta-analysis. The tool also shows how adding that effect size would change the pooled estimate.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

I extend my heartfelt gratitude to Sarah Moore for her invaluable contributions during the early stages of this project. Special thanks to Lee Guantai for his exceptional support with data collection and organization. I also deeply appreciate the research assistance provided at various stages by Dino Kolonic, Wiktoria Niewiadomska, Maxwell Olander, and Maria Wani, whose efforts greatly advanced the project’s progress. Additionally, I am grateful to Daniel De Kadt, Robert Kubinec, Connor Huf, Simon Hug, Jacob Montgomery, Ariel Reichard, Dickson Ajisafe, and Margit Tavits for their insightful feedback, as well as to panelists and discussants at the 2024 Midwest Political Science Association and American Political Science Association conferences. Finally, my sincere thanks to all scholars who have generously made their replication materials publicly available, as well as to those who willingly provided replication data, survey instruments, code, or datasets upon request.

FUNDING STATEMENT

This research was funded by the New York University Abu Dhabi Social Science Division.

CONFLICT OF INTEREST

The author declares no ethical issues or conflicts of interest in this research.

ETHICAL STANDARDS

The author affirms this research did not involve human participants.

Comments

No Comments have been published for this article.