Introduction

No longer confined to digital platform work, algorithmic management (AM) (Lee et al Reference Lee, Kusbit, Metsky and Dabbish2015), or the data-driven automation and augmentation of functions previously executed by human managers, is commonplace in many sectors of the economy (Baiocco et al Reference Baiocco, Fernández-Macías, Rani and Pesole2022; Milanez et al Reference Milanez, Lemmens and Ruggiu2025). While AM could benefit workers, for example, by detecting safety risks and burnout (Staccioli and Enrica Virgillito Reference Staccioli and Enrica Virgillito2024), it also poses challenges to occupational safety and health (OSH) (Bérastégui Reference Bérastégui2021; Parent-Rocheleau and Parker Reference Parent-Rocheleau and Parker2022; Staccioli and Enrica Virgillito Reference Staccioli and Enrica Virgillito2024; Vignola et al Reference Vignola, Baron, Abreu Plasencia, Hussein and Cohen2023; Todolí-Signes Reference Todolí-Signes2021). Compared to other sectors of non-platform work using AM, logistics – such as transportation and warehousing – stands out as an early adopter that is well documented in the literature (Aloisi and De Stefano Reference Aloisi and De Stefano2022; Duggan et al Reference Duggan, Sherman, Carbery and McDonnell2020; Fernández-Macías et al Reference Fernández-Macías, Urzì Brancati, Wright and Pesole2023; Gent Reference Gent2018; Rani et al Reference Rani, Pesole and González Vázquez2024; Hennum Nilsson et al Reference Hennum Nilsson, Matilla-Santander, Lee, Brulin, Bodin and Håkansta2025a, Reference Hennum Nilsson, Bodin, Strauss-Raats, Matilla-Santander, Badarin, Brulin and Håkansta2025b, Wood Reference Wood2021). Challenges identified in this paper are therefore likely indicative of emerging trends in other industries – thus meriting particular attention, especially as AM is spreading across the labour market (Milanez et al Reference Milanez, Lemmens and Ruggiu2025).

Recent research has advanced our knowledge about how industrial relations actors engage with AM, but the focus on their safety and health effects remains limited. Some studies have begun to acknowledge that AM does not simply imply an extension of managerial prerogatives and power over labour (Krzywdzinski et al Reference Krzywdzinski, Schneiß and Sperling2024; Dupuis Reference Dupuis2024). Drawing on labour process theory, power resources theory, and workplace regimes theory, these studies demonstrate that AM is a context-bound political process influenced by power dynamics between a range of actors (not just workers and managers). They also present strategies used by actors to further their interests in relation to new technologies, including negotiations, contestation, and collaboration.

Another strand of research has had an explicit OSH focus and has drawn on work design (Parent-Rocheleau and Parker Reference Parent-Rocheleau and Parker2022) and psychosocial health theory (Lippert et al Reference Lippert, Kirchner and Saunders2023a; Mbare et al Reference Mbare, Perkiö and Koivusalo2024) to analyse the effects of AM on worker wellbeing. While these scholars specifically consider the impact of AM on health, their models are insufficiently sensitive to wider dimensions of work relations that affect health (Quinlan Reference Quinlan2025).

This paper responds not only to the need to consider the wider politico-economic forces that explain the effects of AM but also the need to link AM to OSH. Besides a few studies that consider economic and regulatory contexts (Bender and Söderqvist Reference Bender and Söderqvist2022; Ilsøe et al Reference Ilsøe, Larsen, Mathieu and Rolandsson2024; Doellgast et al Reference Doellgast, Wagner and O’Brady2023; Krzywdzinski et al Reference Krzywdzinski, Schneiß and Sperling2024; Schaupp Reference Schaupp2021), accounts of industrial relations are largely missing from the AM literature. This is despite calls for stronger inclusion of social partners in policies addressing AM (Nurski and Hoffmann Reference Nurski and Hoffmann2022), the appropriateness of collective bargaining for regulating AM (De Stefano and Doellgast Reference De Stefano and Doellgast2023; De Stefano and Taes Reference De Stefano and Taes2023), and proposals to draw on trade union insights to increase the understanding of how AM influences work (Vignola et al Reference Vignola, Baron, Abreu Plasencia, Hussein and Cohen2023). Additionally, due to the dominance of AM studies on digital platform work, which is characterised by precarious employment conditions, there is a need for more research into conventional work settings (Fernández-Macías et al Reference Fernández-Macías, Urzì Brancati, Wright and Pesole2023; Rani et al Reference Rani, Pesole and González Vázquez2024; Staccioli and Enrica Virgillito Reference Staccioli and Enrica Virgillito2024), where AM has different characteristics (Lippert et al Reference Lippert, Kirchner and Meiner2023b) and where the influence of industrial relations differ.

Drawing on interviews with industrial relations actors in the Swedish logistics sector (trade union and employer organisation representatives, managers, and labour inspectors) and government documents, this study responds to these gaps. The aim of this article is to examine how these actors assess AM-associated OSH risks, how they respond to these challenges, and the barriers they face in negotiating the healthy use of AM.

To frame our results, we apply the Pressure, Disorganisation, and Regulatory failure (PDR) framework (Bohle et al Reference Bohle, Quinlan, McNamara, Pitts and Willaby2015; Knox and Bohle Reference Knox and Bohle2024; Strauss-Raats Reference Strauss-Raats2019). This model integrates structural dimensions and power relations to analyse how work organisation impacts OSH. In contrast to the dominant work-health models, PDR incorporates broader contextual factors of interest to IR scholars, including power dynamics, collective bargaining, and the roles of trade unions and government (Quinlan Reference Quinlan2025). Moreover, in contrast to studies on AM that adopt a labour process perspective (Krzywdzinksi et al Reference Krzywdzinski, Schneiß and Sperling2024; Dupuis Reference Dupuis2024; Kellogg et al Reference Kellogg, Valentine and Christin2020; Huang Reference Huang2023; Schaupp Reference Schaupp2021), PDR has an explicit focus on safety, health, and wellbeing rather than working conditions and rights generally.

This article makes an empirical contribution by studying the industrial relations of AM, specifically the strategies and negotiation processes involved, as well as the barriers and opportunities for reshaping AM to reduce occupational risks. This empirical contribution also has theoretical implications because it highlights how the PDR dimensions are not static but constantly renegotiated. The study contributes to the development of the PDR model by moving beyond the workplace level to study the actors with power to co-create institutions and regulations that govern work organisation at national, sectoral, and workplace levels. In this study, this relates to the application of Swedish law at the national level and collective bargaining at the sectoral and workplace levels. Applying PDR to explore how different stakeholders deal with AM can furthermore yield new insights into the ‘politics of algorithmic management’ (Gent Reference Gent2018; Krzywdzinski et al Reference Krzywdzinski, Schneiß and Sperling2024) and inform interventions with potential to strengthen safety, health, and wellbeing in algorithmically managed work.

The pressure, disorganisation, and regulatory failure model

The Pressure, Disorganisation and Regulatory failure (PDR) model explains how work organisation affects OSH (Bohle et al Reference Bohle, Quinlan, McNamara, Pitts and Willaby2015; Quinlan et al Reference Quinlan, Bohle and Rawlings-Way2015; Quinlan et al Reference Quinlan, Mayhew and Bohle2001). It has been applied to a range of occupations and contexts including precarious work (Quinlan Reference Quinlan2013; Gregson and Quinlan Reference Gregson and Quinlan2020), temporary agency work (Cajander et al Reference Cajander, Sandblad, Stadin and Raviola2022, Strauss-Raats and Adăscăliței Reference Strauss-Raats and Adăscăliței2025, Underhill and Quinlan Reference Underhill and Quinlan2011), and, recently, in a comparative study of algorithmically managed logistics work to analyse differences in the effects of AM (Hennum Nilsson et al Reference Hennum Nilsson, Matilla-Santander, Lee, Brulin, Bodin and Håkansta2025a). In the present article, we use PDR differently by applying it to industrial relations actors rather than workplaces or worker groups.

Since PDR considers societal forces beyond the workplace, it can arguably provide more robust explanations for why OSH risks emerge compared to the widely used Job-Demands-Resources (JDR) or Job-Control-Support models, which have previously been applied to AM (Lippert et al Reference Lippert, Kirchner and Saunders2023a; Mbare et al Reference Mbare, Perkiö and Koivusalo2024). These models have been criticised for focusing narrowly on psychological workplace issues and remedies, while ignoring the relevance of political, economic, and regulatory factors shaping OSH (Dollard et al Reference Dollard, Dormann, Idris, Dollard, Dormann and Awang Idris2019; Quinlan Reference Quinlan2025). In an AM context, this means neglecting the political and malleable characteristics of technology, the importance of which is argued for in this paper and elsewhere (Jarrahi et al Reference Jarrahi, Newlands, Lee, Wolf, Kinder and Sutherland2021). Studies drawing on these psychosocial models have documented why AM can cause certain wellbeing outcomes, such as through enhanced or restricted autonomy and work intensification. However, they fail to tease out the economic and regulatory preconditions that configure AM practices in the first instance.

The first element of the PDR model, Pressure, entails two components: economic pressure, such as job insecurity, irregular income, and pressure to work long hours, and reward pressure, such as, piece-rate payment, which encourages behaviours that prioritise productivity over safety and health. The second element, Disorganisation, refers to disruptions caused by inadequate training, poor communication, and procedural failures. These issues can lead to higher injury rates and anxiety (Quinlan and Bohle Reference Quinlan and Bohle2008; Strauss-Raats Reference Strauss-Raats2019). The third dimension, Regulatory failure, refers to poor application of laws, gaps in regulatory coverage, non-compliance, and poor knowledge about rights and obligations (Quinlan et al Reference Quinlan, Bohle and Rawlings-Way2015; Strauss-Raats Reference Strauss-Raats2019). These three factors contribute to the erosion of OSH management observed in many enterprises that rely heavily on contingent or precarious labour. However, they could also offer valuable explanatory value for poor OSH in more conventional work environments with predominantly stable employment relationships. Additionally, with AM spreading to firms with conventional business models, the PDR framework could provide insights into the factors driving the controlling or enabling potentials of AM (Noponen et al Reference Noponen, Feshchenko, Auvinen, Luoma-aho and Abrahamsson2023) and subsequently explain why OSH risks do or do not arise in different contexts.

Algorithmic management and industrial relations in standard work settings

Algorithmic management now performs a range of tasks, including screening job applicants (Meijerink and Bondarouk Reference Meijerink and Bondarouk2023), predicting optimal staffing levels, and generating corresponding schedules (Burgert et al Reference Burgert, Windhausen, Kehder, Steireif, Mütze-Niewöhner and Nitsch2024). Algorithms are also used to allocate tasks, track, and instruct workers in real-time, evaluate performance, and, in some cases, sanction or automatically dismiss workers (Baiocco et al Reference Baiocco, Fernández-Macías, Rani and Pesole2022; Kellogg et al Reference Kellogg, Valentine and Christin2020; Nurski and Hoffmann Reference Nurski and Hoffmann2022).

A systematic review (Noponen et al Reference Noponen, Feshchenko, Auvinen, Luoma-aho and Abrahamsson2023) found that AM is predominantly used for controlling rather than supporting workers. This could explain the overwhelmingly negative view of AM from a worker-centred perspective, and lends some support to neologisms such as ‘digital Taylorism’ (Parenti Reference Parenti2001), ‘algorithmic panopticon’ (Woodcock Reference Woodcock2021), and ‘algorithmic cage’ (Rahman Reference Rahman2019). However, these effects are not predetermined (Noponen et al Reference Noponen, Feshchenko, Auvinen, Luoma-aho and Abrahamsson2023). Indeed, AM could benefit workers with intentional design (Zhang et al Reference Zhang, Boltz, Wang and Lee2022). Echoing Jarrahi et al (Reference Jarrahi, Newlands, Lee, Wolf, Kinder and Sutherland2021), we see AM outcomes as emerging dynamically through interactions between digital technologies and the actors who design, implement, (re)configure, and engage with these systems. From this sociotechnical perspective, the implications of AM for OSH depend fundamentally on these actors’ interests and actions, highlighting power structures and the inherently negotiable nature of technologies.

This perspective becomes all the more important considering the significant differences between conventional work settings and digital labour platforms. Research is needed on the challenges and opportunities of AM in conventional work settings, where regulations, structures, traditions, institutions, and power dynamics established prior to the introduction of AM can modify the use and effects of algorithms on work organisation (Jarrahi et al Reference Jarrahi, Newlands, Lee, Wolf, Kinder and Sutherland2021; Rani et al Reference Rani, Pesole and González Vázquez2024).

AM has the capacity, to an extent, to automate functions previously executed by human managers (Gillespie Reference Gillespie2014; Lee et al Reference Lee, Kusbit, Metsky and Dabbish2015; Wood Reference Wood2021). In traditional work settings, AM tends to extend managerial prerogatives rather than replace human managers (Delfanti Reference Delfanti2021). It enables management to increase both the span and detail of its control of labour via continuous and remote digital monitoring, assessment, instructions, incentives, and discipline (Kellogg et al Reference Kellogg, Valentine and Christin2020; Möhlmann and Zalmanson Reference Möhlmann and Zalmanson2017; Nurski and Hoffmann Reference Nurski and Hoffmann2022). As such, algorithmic systems not only supersede the capacity of human supervision (Aloisi and De Stefano Reference Aloisi and De Stefano2022) and the top-down control in the organisation of work, but also automate management by enabling autonomous decisions, sometimes without the need for managers’ active interference (Alizadeh et al Reference Alizadeh, Hirsch, Benlian, Wiener and Cram2023). However, even if advanced AM can operate semi-autonomously, the design, implementation, and (re)configuration of such technologies are still the responsibility of human actors (Benlian et al Reference Benlian, Wiener, Cram, Krasnova, Maedche, Möhlmann, Recker and Remus2022).

AM has been criticised for lacking the ability to show empathy for workers in the way human managers could (Noponen et al Reference Noponen, Feshchenko, Auvinen, Luoma-aho and Abrahamsson2023). Moreover, the unintelligibility of algorithms due to technical illiteracy, black-box systems, and corporate secrecy entails information asymmetries between labour and capital (Kellogg et al Reference Kellogg, Valentine and Christin2020; Möhlmann and Zalmanson Reference Möhlmann and Zalmanson2017; Rosenblat and Stark Reference Rosenblat and Stark2016). One consequence of the lack of worker influence is the risk of ‘function creep’, where AM initially or purportedly is used for one purpose (such as safety monitoring), but incrementally or in practice is used for other ends (Cefaliello et al Reference Cefaliello, Moore and Donoghue2023; Mantello and Ho Reference Mantello and Ho2024; Oxford Analytica 2022).

While the study context is the logistics sector in Sweden, many AM practices are not industry or country-specific. As elsewhere, in the Swedish transport sector AM is used for GPS and biometric surveillance, monitoring of driving behaviour, and tracking active working time, ostensibly for safety and environmental purposes. It is also used for automated route direction and evaluation of performance (Håkansta et al Reference Håkansta, Lind, Strauss-Raats and Blüme2024). In warehouses in Sweden, algorithms are used for task allocation, instructing workers automatically via headsets, and constant performance monitoring and productivity assessment (Håkansta et al Reference Håkansta, Lind, Strauss-Raats and Blüme2024; Hennum Nilsson et al Reference Hennum Nilsson, Matilla-Santander, Lee, Brulin, Bodin and Håkansta2025a). Previous research suggests that the use of AM in the logistics sector in Sweden is linked to an elevated risk of mental distress (Hennum Nilsson et al Reference Hennum Nilsson, Matilla-Santander, Lee, Brulin, Bodin and Håkansta2025a).

Safety and health consequences

Knowledge about the OSH effects of AM in non-platform work is limited. On the positive side, OSH experts are increasingly seeing the potential of AM to detect and prevent safety risks and burnout. There is also evidence of AM being perceived as fairer compared to tasks delegated by humans. However, despite identifying these positive potentials (Staccioli and Enrica Virgillito Reference Staccioli and Enrica Virgillito2024; Bai et al Reference Bai, Dai, Zhang, Zhang and Hu2022; Wang et al Reference Wang, Harper and Zhu2020), most of the current literature raises concerns about intrusive surveillance and strict control imposed on workers by AM (Kellogg et al Reference Kellogg, Valentine and Christin2020), with detrimental effects on various aspects of job quality. These include impacts on work intensity, skills use and discretion, social work environment, and fairness (Baiocco et al Reference Baiocco, Fernández-Macías, Rani and Pesole2022; Christenko Reference Christenko2022; Howard Reference Howard2022; Lee et al Reference Lee, Kusbit, Metsky and Dabbish2015; Vignola et al Reference Vignola, Baron, Abreu Plasencia, Hussein and Cohen2023), as well as wellbeing and job satisfaction (Fernández-Macías et al Reference Fernández-Macías, Urzì Brancati, Wright and Pesole2023; Howard Reference Howard2022; Jarrahi et al Reference Jarrahi, Newlands, Lee, Wolf, Kinder and Sutherland2021; Kinowska and Sienkiewicz Reference Kinowska and Sienkiewicz2023; Vignola et al Reference Vignola, Baron, Abreu Plasencia, Hussein and Cohen2023). Studies on the OSH implications of AM suggest that it is associated with increased psychosocial risks, including monotony (Fernández-Macías et al Reference Fernández-Macías, Urzì Brancati, Wright and Pesole2023; Kinowska and Sienkiewicz Reference Kinowska and Sienkiewicz2023), accelerated working pace, restrictions on workers’ autonomy (Kinowska and Sienkiewicz Reference Kinowska and Sienkiewicz2023; Lippert et al Reference Lippert, Kirchner and Meiner2023b) as well as lack of influence, transparency, accountability, organisational trust, task significance, and good workplace relations (Parent-Rocheleau and Parker Reference Parent-Rocheleau and Parker2022; Vignola et al Reference Vignola, Baron, Abreu Plasencia, Hussein and Cohen2023). There are also studies demonstrating associations between AM and poorer physical and psychological health (Hennum Nilsson et al Reference Hennum Nilsson, Matilla-Santander, Lee, Brulin, Bodin and Håkansta2025a, Reference Hennum Nilsson, Bodin, Strauss-Raats, Matilla-Santander, Badarin, Brulin and Håkansta2025b).

Study context: Swedish model of labour market relations

Sweden is characterised by a highly self-regulatory industrial relations model, high levels of affiliation to workers’ and employers’ organisations, and collective agreement coverage (Anxo Reference Anxo2021; Kjellberg Reference Kjellberg, Müller, Vandaele and Waddington2023). Like other Nordic countries, Sweden has strong social partners with extensive co-determination rights. Most labour laws in Sweden are dispositive, meaning they can be overridden by clauses in collective bargaining agreements, including in wage formation and (often) working time (Medlingsinstitutet 2023). Although union density and collective agreement coverage remain high in comparison internationally, they have declined amongst blue-collar workers from 88% in 1995 to 59% in 2023 (Larsson Reference Larsson2024). In logistics, the degree of unionisation was 59% in 2023 (Larsson Reference Larsson2024).

OSH is a notable exception to dispositive labour law (Swedish Work Environment Act (Arbetsmiljölagen [1977:1160]; Swedish Parliament 2021). Health and safety representatives (appointed by the employees and often connected to the local union clubs) and labour inspectors (working for the Swedish Work Environment Authority, SWEA) act to ensure compliance with OSH regulations and collective agreements. Thus, the social partners and other actors, i.e., managers, health and safety representatives, and labour inspectors, are instrumental in shaping OSH in much of the Swedish labour market.

Research design and methods: thematically analysed interviews and documents

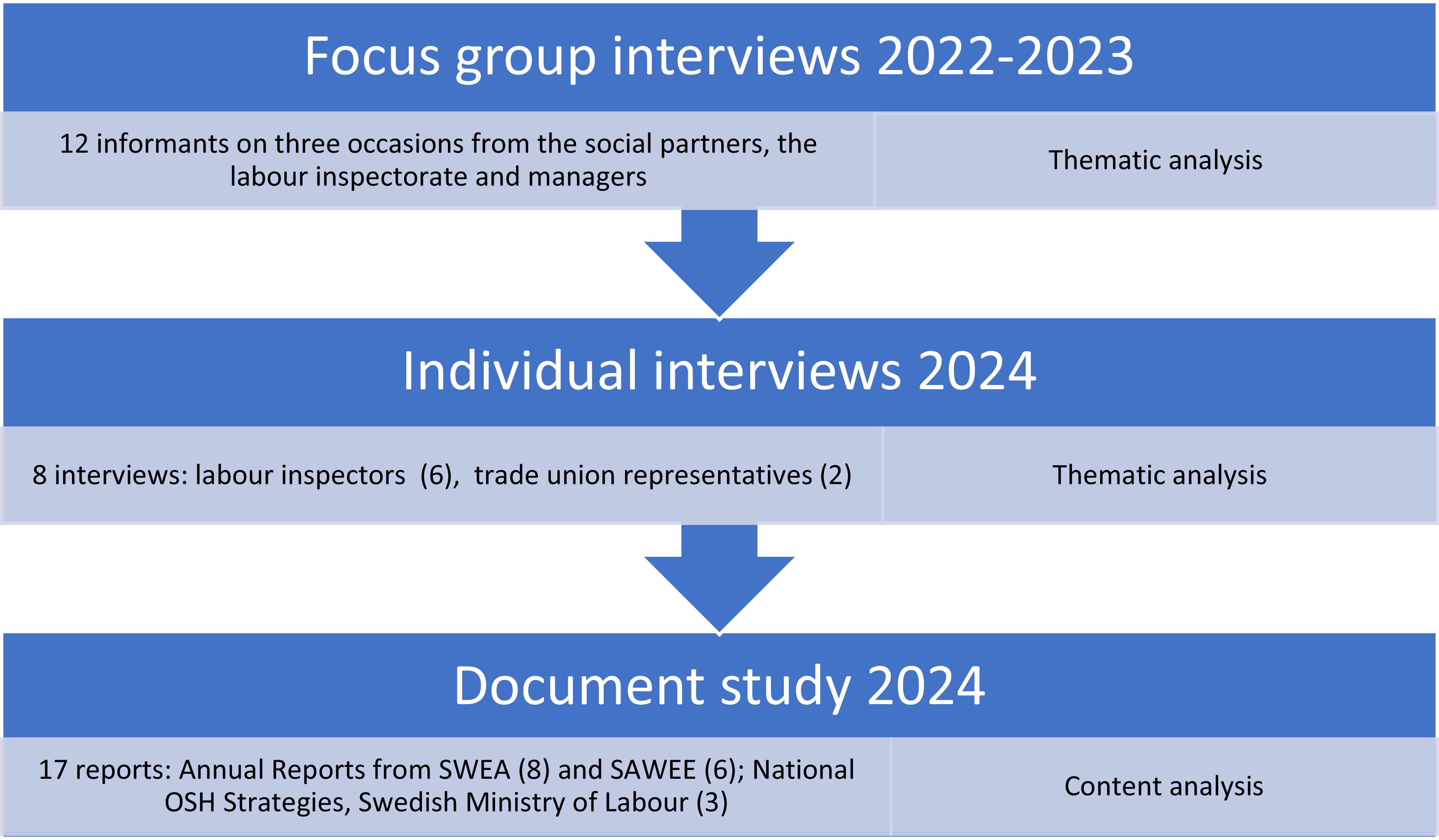

This study is based on qualitative data collected in 2022 and 2024 (see Figure 1 below).

Figure 1. Overview of collected data and analytical methods.

The 2022 data was gathered in the context of a research project on the health and safety effects of AM in the Swedish logistics sector (Ethical approval no. 2022-00169-01). The 2024 trade union interviews were conducted in a research project exploring the response of Swedish workers and trade unions to AM (Ethical approval no. 2024-0080502). The 2024 interviews with labour inspectors and document analysis were carried out without ethical approval but involved no collection of sensitive personal data.

Data collection

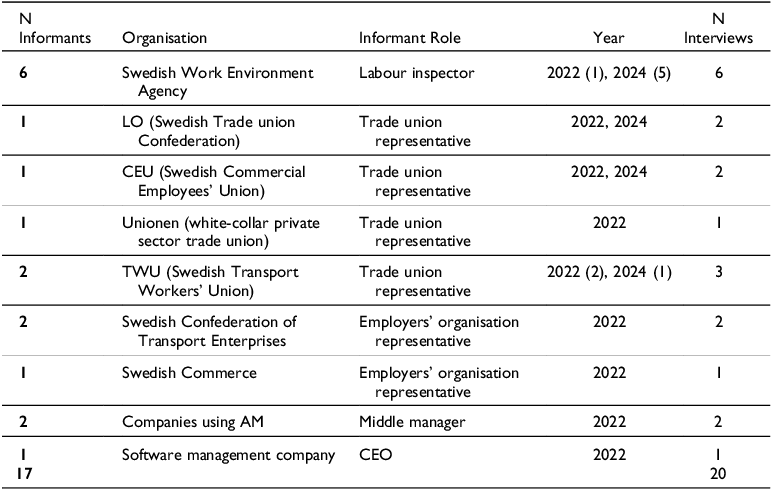

In order to capture how the social partners assess AM-related OSH risks and strategies to counter these risks, focus group interviews were organised in 2022 (see Table 1). The recruitment was purposeful as we needed informants with insights into safety and health in the logistics sector. We carefully selected and recruited informants from logistics trade unions and employer organisations at the branch and national levels, and managers active in organisations using AM. Because two key informants from the transport union had to cancel their in-person participation, we complemented the focus group interviews with an online interview with those participants. Informants were recruited via e-mail with an aim to represent the labour market actors in the logistics sector. Of the 17 people invited, 12 participated.

Table 1. Number and year of interviews and affiliation and role of interviewees in individual and focus group interviews

The aim of the focus group interviews was to bring together actors with distinct roles and OSH knowledge in the first explorative phase of our study. Focus group interviews are ideal for dynamic discussions between a selected number of informants (Krueger and Casey Reference Krueger and Casey2009). The interviews lasted 60-70 minutes each and included questions on AM discussions in their respective organisations, experiences of effects of AM on OSH, and whether they were aware of action or strategies related to managing OSH risks stemming from AM. The method was conducive to the explorative nature of the study and generated rich, comprehensive data (Johannessen and Tufte Reference Johannessen and Tufte2002) that we used to obtain perceptions in the defined area of AM and OSH in logistics. The informants in each interview were asked to speak freely about their own experiences and reflections, and not as representatives of the views held by their employers. The participants were divided into a ‘worker and state actors’ group and an ‘employer actors’ group to avoid a situation where social actors with contradictory interests debated each other instead of feeling comfortable in ‘a permissive, nonthreatening environment’ (Krueger and Casey Reference Krueger and Casey2009). Since there was only one representative from the SWEA, we included this informant in the group of trade union representatives.

In response to an increasing societal debate about AM in Sweden during 2024, we conducted a second phase of data collection to complement our initial focus group interviews (Table 1). In addition to conducting semi-structured interviews with selected trade union representatives, we supplemented the single interview conducted with a labour inspector in 2022 by including further data on the government position, thereby shifting from a bipartite to a more comprehensive tripartite perspective.

In 2024, semi-structured interviews were carried out with three of the trade union representatives interviewed in 2022. These informants were from the Swedish Trade Union Confederation (LO), the Swedish Transport Workers’ Union (TWU), and the Swedish Commercial Employees’ Union (CEU). The purpose was to explore changes over time in their engagement with issues related to AM and OSH. Despite repeated attempts, we were unable to secure interviews with employer organisations in 2024. However, informal communication via telephone conversations and e-mail exchanges provided insights into their positions. Additionally, to expand beyond the single labour inspector participating in the 2022 focus group, we conducted five individual online interviews with labour inspectors from different regional offices of the Swedish Work Environment Agency (SWEA). These interviews, facilitated by SWEA centrally, focused on how digitalisation has affected the inspectors’ professional roles and how they address digital work environment concerns, including AM. In total, 17 informants participated in the study through focus groups and semi-structured interviews (Table 1).

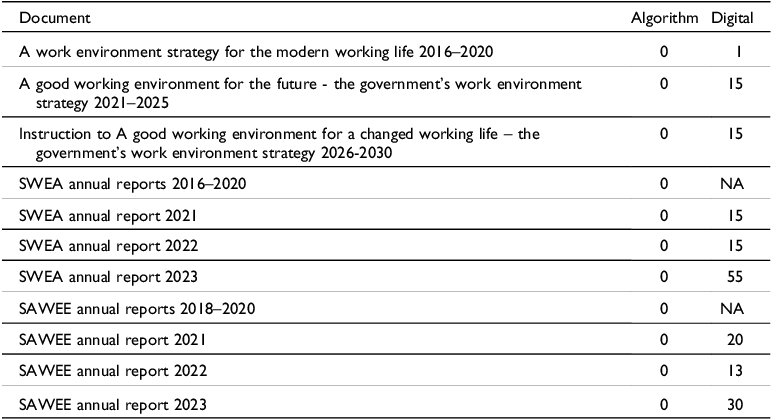

To understand the broader government position on AM and OSH, complementing the labour inspector interviews, we asked the Ministry of Employment for an interview. The request was declined, and an e-mail from a civil servant suggested we find information in existing documents and from the labour inspectorate (SWEA). We identified two types of useful documents (detailed in Table 3): the five-yearly work environment strategies of the government and annual reports of the two government agencies active in OSH, SWEA, and the Swedish Agency for Work Environment Expertise (SAWEE). The national OSH strategies are important because they set the budget and work plans for SWEA and SAWEE. The Annual Reports, in turn report on achievements and budget, thus providing an overview of government policy and priorities over time. While recognising that neither strategies nor annual reports cover all details and politics behind the documents, they nevertheless offer an illustration of how and to what extent the government discourse includes AM.

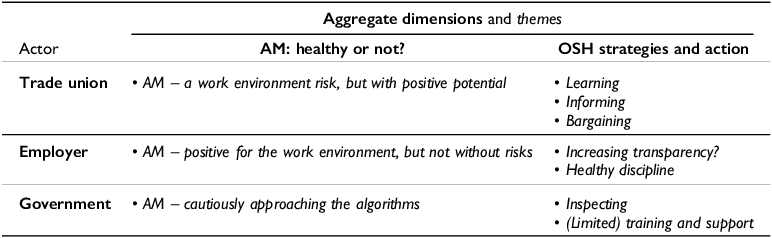

Table 2. Overview of themes divided by two aggregate dimensions and three actors: trade unions, employers, and government

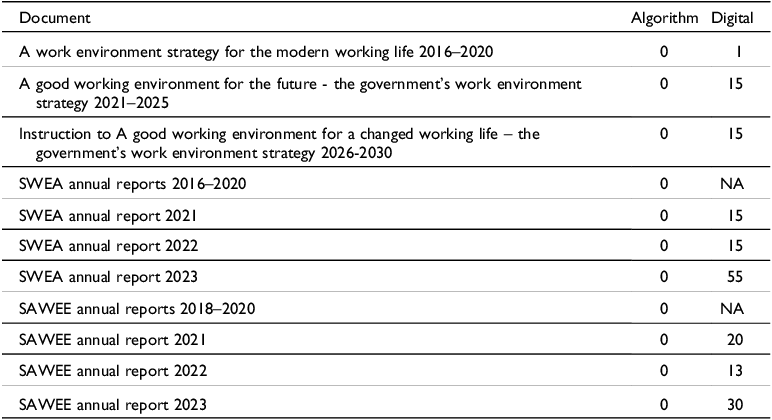

Table 3. Word count of ‘digital’ and ‘algorithm’ in OSH strategy documents and annual reports of government organisations SWEA and SAWEE

Data management and analysis

The focus group and individual interviews were audio recorded and transcribed in ‘intelligent verbatim’ (McMullin Reference McMullin2023). Information that could enable the identification of individuals was pseudonymised. Transcribing was outsourced to a professional service, and all data was stored at secure local servers only accessible to the authors.

Focus group and individual interviews were analysed thematically. Following Braun and Clarke’s (Reference Braun and Clarke2006, Reference Braun and Clarke2019) reflexive approach to thematic analysis and Naeem et al’s (Reference Naeem, Ozuem, Howell and Ranfagni2023) insights, we used inductive coding while consciously drawing upon existing knowledge from the AM and OSH literature and the specific context of Swedish industrial relations.

We actively engaged with the data rather than merely summarising patterns (Braun and Clarke Reference Braun and Clarke2006). Throughout the iterative process of coding and theme generation, we focused on the experiences of AM, the perceived effects of AM on OSH, and actions or strategies the informants had experienced or suggested for the future. After creating an initial set of themes, these were reviewed by the whole research group, and new themes were created while others were scrapped or redefined depending on their relevance to our research aims. In the analysis of the focus group interviews, we searched for patterns of shared meaning across the themes for each of the three stakeholder groups. This was done to create aggregate dimensions encompassing actions, strategies, and perspectives on the effects of AM. According to Wæraas (Reference Wæraas, Espedal, Jelstad Løvaas, Sirris and Wæraas2022), ‘aggregate dimensions could clarify certain shared aspects of the values or highlight common underlying assumptions’. We use aggregate dimensions to bring together similar themes across the three actor groups to facilitate comparison between them. The 2024 complementary one-to-one interviews with labour inspectors (n = 6) and trade union officials (n = 3) were thematically analysed in the same way, but with greater focus on changes over time than on inter-group comparisons, to add to the 2022 interviews and document study.

The purpose of the document analysis was to complement the information gathered from the labour inspector interviews. A content analysis (Bryman Reference Bryman2016) was performed on government strategies and annual reports from SWEA 2016-2024 and SAWEE 2018-2024 to examine patterns in how AM is described in relation to OSH over time. The 2024 report was not published at the time of the analysis (Swedish Agency for Work Environment Expertise (Myndigheten för arbetsmiljökunskap, Mynak 2024). We wished to identify passages that could inform us of action and strategies, as well as position on AM-related OSH risks (Bowen Reference Bowen2009). To identify relevant excerpts and as a proxy for government interest in and attitudes towards AM, we searched for occurrences of the term ‘algorithm’ in the documents.

As this exercise did not result in any relevant passages, we instead searched for the broader term ‘digital’. Table 3 illustrates the results of this exercise. Annual reports of SWEA and SAWEE from the years 2016-2021 were excluded from the table because the word digital did not occur at all in relation to the digitalisation of work.

In the discussion section, we have applied the PDR model to elucidate the underlying factors conditioning the main findings, i.e., the role of Pressure, Disorganisation, and Regulatory failure in influencing government and social partner action and strategies related to AM and OSH.

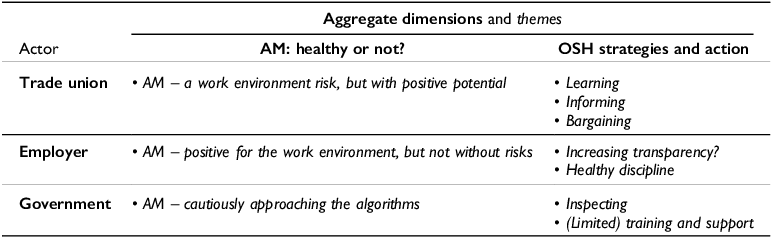

Results: strategies and attitudes among employers, trade unions, and government

The results section is divided into three subsections presenting the attitudes and strategies of each actor – government, trade unions, and employers. Each subsection is organised around two aggregate dimensions: AM – healthy or not? (three themes) and OSH strategies and action (seven themes). Since data from social partners were collected at different times, comparisons over time are also presented. Table 2 illustrates these themes across actors and aggregate dimensions, showing how actors’ strategies generally reflect their attitudes towards AM and OSH.

Trade union strategies: from mobilising to action mode

The interview data from 2022 showed that the trade unions were more proactive than the government and employers’ organisations in mobilising efforts addressing AM. Under the aggregate dimension AM: healthy or not?, our analysis showed that trade union representatives perceived AM as a work environment risk, but with positive potential. Representatives identified both the job threat posed by AM and the positive potential in technological development. They ultimately viewed AM in overwhelmingly negative terms, being more concerned about risks than positive potential.

We have a special working group that looks at this type of problem […] [I]t is not the advantages of these systems that we are looking at, but of course the disadvantages and how it affects individuals, but also how it affects the way of working, the way of organising work, how it affects the union strength. (LO Representative)

Concerns included fear of standardisation and control leading to monotonous and strenuous work, increased replaceability, job insecurity, and reduced autonomy. The representatives also discussed perceived OSH risks, such as psychological and physiological strain from work intensification and privacy infringements. One informant said that ‘surveillance in itself is a work environment hazard’, referring to the anxiety experienced by workers from digital monitoring. Alienation and social disconnection were also highlighted as risks arising from AM, as workers allegedly felt dehumanised by the meticulous recommendations and restrictions enacted by digital picking systems.Footnote 1

Faulty decisions or inaccurate estimations of worker performance were said to be the result of systems failing to consider the complexity of work processes, including contextual factors or unforeseen events. Informants also highlighted that the quantification of work tasks was only measured through parameters programmed into the systems, leading workers to feel stressed, frustrated, and unfairly assessed. Overall, the informants perceived AM systems, despite being introduced to enhance efficiency, as frequently malfunctioning and producing ineffective outcomes.

Other perceived risks related to function creep and illegitimate use of data. The informants expressed fear of illegitimate data use by management and difficulties in preventing employers from collecting, using, or storing information that was either illegal or, in other ways, threatened the well-being of workers. A TWU representative illustrated this challenge with a complaint from a member who had had dashcams installed in his vehicle, ostensibly for safety reasons. The system provided the manager with extensive information about the driver’s behaviour, which was used to legitimise his termination. A reported challenge for unions in such cases was employers using AM systems and worker data with discretion, sometimes in violation of labour laws, the EU’s General Data Protection Regulation (GDPR), and collective agreements.

Informants saw impending risks of data collection undermining workers’ rights and employment security. Knowing of previous instances where function creep had occurred, there was suspicion about data collection in general, regardless of whether the rationale provided by managers was related to safety, environmentalism, efficiency, fairness, or making jobs more stimulating. Informants perceived management’s official reasons for implementing AM as insidious.

…the employer says it’s about road safety, but it’s about efficiency… the technology is often sold with the idea that it will lead to better work environment and that we will get more developing jobs. (TWU Representative 1)

Though overwhelmingly concerned about the OSH risks entailed by AM, union representatives also considered the positive potential inherent in technological innovations. The informants did not think that data collection and automated decision-making were detrimental to workers per se – they highlighted how data could potentially be used for workers’ benefit, such as demanding more humane target quotas, staffing levels, or pay increases, since metrics could be used as a bargaining tool in negotiations. A precondition for data to be used for improved working conditions, however, was that workers and unions had access to the data, which was often not the case.

The informants also saw technologies as malleable, stressing that algorithmic systems could easily be designed to take OSH into account. However, despite the potential of AM to improve the work environment, they had not seen it realised in practice. Instead, they implied that managers (re)modified systems for control purposes without consulting workers. One trade union representative expressed frustration that managers removed helpful features in systems that gave workers a better overview of their workday and tasks, including information about walking distance, weight of items, and rate of completion.

…suddenly the employer has reprogrammed the system so that you don’t get this information. And this is a problem because often the employer is in control over the system. They reprogram, perhaps without consulting the employees. (CEU Representative)

Under OSH strategies and action, three themes stood out: learning, informing, and bargaining. Learning entailed survey and interview studies carried out by trade unions at a central level and in the transport and warehousing sectors. These looked at which technologies were used, what effects they had on working conditions, and how workers experienced the technologies.

Informing consisted of outreach to members about AM-related risks and rights via awareness-raising campaigns, and when meeting with members. For example, the TWU warned about hazards related to sharing personal data with employers and informed members about data protection rights stipulated in the GDPR. The transport and white-collar union representatives were concerned about the naïveté amongst their members about such risks. The white-collar union representative claimed that risk awareness was low and that the habit of sharing personal information on the Internet made employees less cautious of managerial data collection. TWU representatives stated that workers became fully aware of the risks only when managers began using data for disciplinary actions, such as dismissing employees. However, these problems were attributed not only to workers’ failure to recognise AM-related risks but also to information asymmetries arising from employers not disclosing data collection, how data was used, and the use of opaque black-box systems. Unions also acknowledged that both they themselves and employers frequently failed to recognise AM as a fundamental issue of work organisation and OSH, requiring appropriate responses and adherence to established OSH procedures and regulations. As one informant expressed, ‘You may not realise that these are classic union issues […] or that the employers don’t really think of it that way either’ (LO Representative). Consequently, preventive strategies were difficult to implement.

Another obstacle was that new EU regulations (the AI Act and Platform Work Directive) could negatively impact the legibility of legislation as well as the attention to national regulations, with product safety risk assessments given precedence over OSH risk assessments:

…some companies may think that “now it’s just this risk management thing we have to do,” and forget completely that there is work environment management to do, thinking that it [The AI Act] trumps this. It is the same with the Platform Directive. There are also so many regulations that actually already exist […] which means that it can get confusing. (LO Representative)

Informing was approached as a second-best alternative to more far-reaching interventions, such as prohibiting specific high-risk AM systems. One proposed strategy was to leverage data collection to increase trade unions’ understanding of AM systems and to use these insights to safeguard members’ interests:

If we can’t stop Pick-by-Voice [an AM system], for example, we think about how we can make sure to program it so that we can get more information and say no to certain things. (CEU Representative)

Bargaining entailed negotiating AM by invoking existing regulations, e.g., GDPR, co-determination rights, work environment regulations, and collective agreements. For example, in the case of an employer using dashcam surveillance data to terminate an employee’s contract, TWU pointed out that such invasive data collection was illegal. In a subsequent collective bargaining process, TWU pushed for restrictions on data collection, allowing information to be gathered and analysed at the group level only. This was confirmed by a manager, who said they were not allowed to track or evaluate workers individually. According to union representatives, however, individual monitoring and performance reviews still occurred. Unions also bargained to restrict employers’ access to data and to ensure AM was used exclusively for agreed-upon purposes. However, this strategy was fraught with difficulties since employers often used multiple AM systems simultaneously.

We have examples of regulating certain systems, for example “this information is collected through the picking system and only this supervisor or this person has access to it”, and then you feel like “now we got this”. But then you discover that there is another system […] that collects the same or similar data that you have not regulated. (CEU Representative)

The interviews in 2024 were consistent with the strategies from 2022: Learning, Informing, and Bargaining, though with a notable shift towards a more operative approach. For example, the unions were engaged in negotiations related to the EU AI Act and the Platform Work Directive, objecting to statutory legislation due to a preference for regulation through collective agreements. Another reason for scepticism towards supranational regulation was the Swedish social partners’ traditionally positive attitude toward structural transformation, leading to caution about imposing laws regarding the introduction of new technologies.

To address the challenges of low compliance with relevant regulations due to ignorance among unions themselves and employers, LO also continued with learning and informing strategies. This included mapping AM prevalence via the sectoral unions, conducting awareness-raising activities, and developing general-purpose tools, such as checklists to assess risks associated with digitalisation and AM.

A sign towards a more proactive stance was concrete policy recommendations in union survey reports. The CEU report asked for skills development and suggested increased use of existing legislation, including GDPR, the co-determination and OSH laws (Wrangborg and Söderberg Talebi Reference Wrangborg and Söderberg Talebi2023). The TWU report (TWU 2024) concluded that ‘[e]mployees are surveilled, a majority of employers do not comply with applicable law regarding integrity, and employees are not involved to a sufficient degree when new technologies are introduced’, and that this risked leading to safety and health hazards (TWU 2024). Moreover, it demanded that employers guarantee worker influence in all stages of implementing technology, echoed the emphasis on skills development, and suggested a change in the Swedish implementation of GDPR so that trade unions, not only private individuals, could lodge complaints to the Swedish Authority for Privacy Protection (IMY).

Employer organisations: passive but interested

Under AM – healthy or not?, the theme capturing the views of employers and their representatives was AM – good for the work environment, but not without risks. The group generally believed that monotonous and menial tasks could be rendered more rewarding due to the enhanced feedback opportunities provided by AM, and that workers even requested algorithmic performance evaluation for this reason.

It’s interesting that many employees request this, too […] [F]rom a work environment perspective, there is a big gain in being able to say “Today I have done what was expected of me. I picked 1000 books,” unlike the other end of the spectrum: “Today I know that I was in the premises for eight hours.” It might not be as fulfilling. (Middle Manager 1)

Another general belief was that AM alleviates job demands and strain, e.g., due to optimised distribution of products, shelves and routes in warehouses and distribution chains, and route-optimisation and driving recommendations in transportation.

It’s obvious that algorithms improve your work environment, that they make you walk shorter distances […] Bestselling products are often placed in a central location and at a convenient height […] All of that should be experienced positively. (Middle Manager 1)

The same manager also stressed improved fairness, stating that AM divided work tasks more evenly than a human foreman could, thus promoting equity in task distribution:

Five years ago, [we] had these paper lists […] you could riffle through and select a specific picking and so on. All that disappears and it becomes more equal between people. Everyone has the same chance or risk to do the same type of task. (Middle Manager 1)

As with unions seeing positive potential in AM technologies, the employer actors acknowledged the existence of risks of AM. Concerns highlighted potentially negative consequences of worker surveillance; anxiety caused by uncertainty related to what data was collected, for what purposes, and how it was used; strain from work intensification in the wake of increased demands since workers ‘feel they want to do more’ when they were directed and evaluated by AM systems; and perceived job insecurity due to potential redundancies as AM optimised labour processes. Yet another example, illustrated by the quote below, concerns the perceived frustration experienced by algorithmically managed employees due to the opacity and unintelligibility of constant and instant instructions conveyed by digital technology.

it could be that you don’t really understand this picking route and think that you get sent here and there[…] and you experience […] a frustration that you don’t understand. (Middle Manager 2)

Compared to the initiative-taking stance of the trade unions vis-à-vis AM, there were few signs of action from the employers’ organisations. In conversations over mail and telephone in October 2024, our request for an interview with one employers’ organisation was declined on the grounds that they did not get involved in how their member companies organise or which machines or tools they wish to use in their operations. The question of AM had not been raised by member organisations. The inertia of the employers’ organisations in the 2022 focus group interview did not seem to have changed significantly.

Managers in the 2022 focus groups with experience of working with AM saw AM as a necessity to survive cut-throat competition and as a potential means to improve OSH. Under OSH strategies and action, one theme was increasing transparency of data collection and usage, based on the suggestion that this would counteract potential stress due to digital monitoring and performance evaluation. However, there was no consensus on this strategy, as evidenced by a manager expressing that transparency and explainability were redundant:

[the worker] understands the problem that needs to be solved, but [the worker] doesn’t understand how it is solved […] and there is no need for that either. You understand that it’s based on customer orders, which products we’ve sold, what’s being picked, and what products I have in proximity, so to speak. But what type of algorithm is used… We don’t even try to go into that. (Middle Manager 1)

Another strategy was healthy discipline, to incentivise compliance with algorithmic recommendations by reasonable goal setting. One manager described how young, unexperienced workers often worked faster and took risks when trying to complete target quotas in advance, whereas older, experienced workers usually performed tasks with consideration to ergonomics and safety. Using data to identify and address those who ‘overperformed’, thus putting their health and safety at risk, had become a strategy to nudge workers towards risk reduction. One way of disincentivising workers from overexertion was not allowing them to leave the workplace before the end of their shift and allocating extra tasks if quotas were completed. If a worker consistently surpassed the algorithmically calculated average, this was addressed in assessment talks where managers suggested that the worker slowed down. Thus, the set working time, location, and correctional meetings strived towards stricter control over the employees’ working pace and geared incentives towards a safe pace and execution.

Government strategies: slowly approaching the algorithms

Under the aggregate dimension AM – healthy or not?, the theme capturing the government’s stance was AM – cautiously approaching the algorithms. This was mainly based on the document analysis of national OSH strategies and instructions to the two government agencies involved in OSH matters: SWEA and SAWEE. Since 2016, government OSH policy in Sweden has been guided by five-year work environment strategies, developed by the Ministry of Employment in consultation with other ministries, government agencies, and social partners. These strategies mirror government ambitions and serve as guidance for the annual budgets and assignments allocated to SWEA and SAWEE. The annual reports of SWEA and SAWEE consist of financial outcomes and other types of results required by the government for the past year.

In our search for words including ‘algorithm’ and ‘digital’ in the documents (Table 3), we found that ‘algorithm’ was absent. The number of times ‘digital’ appeared in the national OSH strategies increased from one in the first strategy (for the years 2016-2020) to many more in the current strategy (for 2021-2025) and in the instructions to the next OSH strategy (2026-2030). The annual reports of SAWEE and SWEA displayed a similar increase over time. In the annual reports before 2021, we did not find any use of the word ‘digital’ in relation to OSH. This changed over the years 2021 – 2023, as the use ‘digital’ changed from featuring predominantly in the context of the government digitalisation, to a quantitative and qualitative increase in described activities related to OSH and digitalisation in the workplace.

In the first OSH strategy (2016–2020), only one passage comes close to AM. It appears in the section New ways of organising work in relation to problems of applying the OSH legislation to digital labour platform work (Ministry of Employment 2016, 24-25). In this context, SWEA is requested to carry out pilot inspections on digital platform work and umbrella companies, and to produce a literature review on the potential OSH risks linked to digital work, crowd work, and the sharing economy (Ministry of Employment 2016, 25). In the current strategy, focus on the psychosocial work environment (which also appeared in the previous one) is placed more specifically on cognitive strain from digital work:

Today’s working life places increasing demands on cognitive abilities. We work increasingly with information. Not only in white-collar professions, but also, for example, in industry, crafts, and healthcare. (Ministry of Employment 2021, 4)

The text calls for technology that takes employees into consideration and future OSH management to adapt to the new challenges and conditions (Ministry of Employment 2021, 25). A new OSH strategy (2026–2030) was underway when writing this paper. In the government directives, digitalisation is, for the first time, specifically mentioned as a relevant OSH factor. The general, ‘neutral’ attitude towards AM as an OSH factor is illustrated by the following quote highlighting both risks and positive potential in digital technologies:

Purposeful digitalization and the use of artificial intelligence can simplify and facilitate the work in many businesses but can also entail the need for competence development and restructuring of the workforce as well as adaptation of the work environment. (Ministry of Employment 2024, 5)

As an EU member state, Sweden must change national regulations in accordance with EU law. One plausible reason for government cautiousness is that the negotiations for the EU Platform Work Directive and the EU AI Act, adopted in 2024, stalled Swedish initiatives to reform current OSH legislation – as it was not known whether or how much the EU regulations would affect Swedish law.

The increased attention to digitalisation and OSH in the 2023 annual reports of SAWEE and SWEA is partly linked to the EU-OSHA campaign Safe and healthy work in the digital age. The two organisations are responsible for action in relation to the strategy, such as the literature review on Artificial intelligence, robotisation and the work environment (Swedish Agency for Work Environment Expertise 2022b) and the commissioning of two more (to be published in 2025): Ethical and legal challenges in the use of artificial intelligence for work management purposes and Prevention of work environment risks in connection with platform work.

Regarding OSH strategies and action, we generated two themes. The first, Inspecting, captures the increased consideration of AM in labour inspections. The labour inspector in the 2022 focus group interview had been involved in inspections of the e-commerce segment in 2019-2022, resulting in approximately 1300 inspections. This campaign originated from signals of OSH risks in this growing segment from inspectors, media, and social partners (Swedish Work Environment Agency 2022). As SWEA did not provide training related to digital technology at the time, the inspector’s strategy was to take personal initiatives to stay up to date with developments and take digital aspects into account when conducting inspections.

Related to this was the second theme, (Limited) training and support. The five labour inspectors interviewed in 2024 confirmed the upswing in interest in digitalisation in the annual reports from SWEA due to the European Campaign. They described how they, until then, had lacked both the know-how and tools to inspect OSH risks associated with digital technology. In 2023, that changed as all inspectors were involved in an inspection campaign, resulting in 1,557 workplace inspections (Swedish Work Environment Agency 2023). Inspections focused on OSH risks and systematic OSH management in relation to digital work methods, with particular emphasis on psychosocial risks, including cognitive risks. The informants said that the preparatory training had been welcome, yet it was insufficient to secure the insights needed to understand OSH risks beyond cognitive strain, and to grasp the risks associated with distinct types of digital technology, including AM.

Discussion

The aim of this study was to understand how industrial actors view and strategise around AM and OSH, as well as the conditions influencing their strategies. Perspectives ranged from trade unions viewing AM as a work environment risk but with positive potential, employer actors seeing it as positive for the work environment but not without risks, whereas the government cautiously approached the algorithms. While one could view these attitudes as governing the respective strategies, another perspective could posit that attitudes reflect material interests and that strategies in turn are conditioned by structural constraints and opportunities. Here, the results are discussed in the light of the PDR model to explore the wider industrial relations context that conditions the tripartite stakeholders’ actions and how these affect OSH outcomes theoretically.

Economic and reward pressure

While the original use of the PDR model mainly focuses on pressures within the workplace, in this study, the employer organisations and managers emphasised pressure from the wider market context of harsh competition, due not least to the rise of e-commerce as the driving force to adopt AM in logistics. This mirrors the logic of scientific management as analysed by labour process scholars (Burawoy Reference Burawoy2012; Edwards Reference Edwards1979; Friedman Reference Friedman1977), with extensions of managerial control and degrading work organisation resulting from profit-seeking and firm survival imperatives. Economic Pressure explicitly conceptualised at the macro-level provides an explanation for the emergence of ‘digital Taylorism’ (Parenti Reference Parenti2001) as well as the documented overall controlling application of AM (Noponen et al Reference Noponen, Feshchenko, Auvinen, Luoma-aho and Abrahamsson2023). It is also in line with previous research on the retail and logistics sector, showing that unpredictable demand, labour-intensive operations, high costs, and slim profit margins in the e-commerce sector encourage companies to adopt systems that transfer these pressures onto workers (Gutelius and Pinto Reference Gutelius and Pinto2023; Gutelius and Theodore Reference Gutelius and Theodore2019). Economic Pressure, moreover, has explanatory power regarding the design of AM for controlling purposes (Noponen et al Reference Noponen, Feshchenko, Auvinen, Luoma-aho and Abrahamsson2023) as management reconfigures systems in ways that strip workers of supporting functions, as explained by trade union representatives. The employer informants also argued that AM enabled them to fight off international competition, thus preventing job displacement, which they saw as an impending risk in a market characterised by automation and competition from platform firms.

Although recognising market pressure experienced by the employers, the trade union representatives did not find it a valid excuse for transferring these pressures on workers via AM. They pointed out how the current design of AM increases Reward Pressure on workers, causing significant psychological and physical strain even when not linked to a payment-by-results system. Both arguments are in line with concerns expressed in the literature about the negative impact of AM on job quality (Baiocco et al Reference Baiocco, Fernández-Macías, Rani and Pesole2022; Christenko Reference Christenko2024; Fernández-Macías et al Reference Fernández-Macías, Urzì Brancati, Wright and Pesole2023; Howard Reference Howard2022; Jarrahi et al Reference Jarrahi, Newlands, Lee, Wolf, Kinder and Sutherland2021; Vignola et al Reference Vignola, Baron, Abreu Plasencia, Hussein and Cohen2023).

Disorganisation

The unintelligible functioning of AM systems and the technical illiteracy of managers, workers, union representatives, and labour inspectors alike – largely due to the novelty of AM as a work environment phenomenon – permeated the discussions and strategies of all three actors. The employer organisations acknowledged ignorance of the effects of AM on OSH, but were rather passive, with few incentives to act. The government seemed similarly hesitant to take action, causing frustration among inspectors, who called for training and tools enabling them to inform about and inspect OSH risks related to AM and other digital technologies.

Trade unions proved by far the most proactive in raising knowledge among their members, appraising potential, and gathering information on AM-related OSH hazards. Unions were also calling for increased employer awareness and action in ensuring safe and healthy use of AM. They reported insufficient risk assessments, with employers’ failure to acknowledge and control AM risks reflecting Disorganisation within workplaces. Based on our data, Disorganisation was grounded in a lack of knowledge about the potential OSH impact of AM. This deficient awareness cut across all three labour market actors, making an efficient risk assessment or systematic OSH management, including AM risks, unlikely. Existing power imbalances between workers and managers are likely to increase due to extended managerial prerogatives and information asymmetries (Kellogg et al Reference Kellogg, Valentine and Christin2020; Möhlmann and Zalmanson Reference Möhlmann and Zalmanson2017; Rosenblat and Stark Reference Rosenblat and Stark2016). These imbalances further complicate the matter as workers’ ability to organise and make grievances gets suppressed if they are kept in the dark about data collection and system functioning, hindering the effectiveness of a critical element of OSH management within the Swedish model. There are some proposed strategies aimed at redressing Disorganisation, e.g., one manager’s suggestion to increase transparency through clear communication about data collection, or the unions’ work in raising workers’ knowledge of data rights. However, not all the employer informants agreed that this was necessary or practically possible. On the one hand, previous research has found mediating effects of transparency and worker involvement on the negative impacts of AM on wellbeing (Doellgast et al Reference Doellgast, Wagner and O’Brady2023; Wrangborg and Söderberg Talebi Reference Wrangborg and Söderberg Talebi2023), with current findings suggesting such strategies indeed could remedy the effect of Disorganisation and related OSH hazards. Employers’ resistance to transparency, on the other hand, reinforces an information imbalance between employers and employees, undermining effective regulation by weakening workers’ and unions’ ability to meaningfully engage in standard-setting and monitoring processes at different levels of regulation.

Regulatory failure

Two underlying problems emerged in this study: how to apply or adapt existing legislation to AM, and the more context-bound problem of the Swedish model and long-winded EU negotiations. Both employers and trade unions struggled with the first. Trade unions criticised employers for misusing and implementing AM with discretion, often disregarding existing regulations of co-determination and OSH management, including risk assessments. Meanwhile, government enforcement of existing laws was limited by a lack of knowledge about AM, as well as deficient training and support to labour inspectors. This illustrates Regulatory Failure in both deploying AM and enforcing mitigation of its potential risks through legal means. Because Swedish labour law is technology-neutral, it ought in theory to apply to AM.

In addition to AM being a relatively new and sometimes overlooked phenomenon to the social partners, we suggest that this is also linked to the legal boundary-spanning nature of AM, incorporating legal acts not traditionally considered in the context of OSH (such as data protection laws). While legislation was invoked by trade unions in negotiations around AM, they found that AM was not considered an OSH issue by employers, which led to insufficient involvement of workers and unions, as well as poor application of existing laws to AM. Another reason for Regulatory Failure seems to be the information asymmetries between trade unions and employers with regard to AM. As it was oftentimes not transparent to unions which systems were deployed or how they functioned, it was difficult to bargain over their regulation. According to the unions, negotiating limits to one specific system was generally not enough to ensure non-hazardous AM usage, as employers generally applied a myriad of different overlapping AM systems within the same company.

In the OSH context, we suggest that another factor that may complicate the regulation of AM is the unfamiliar hybrid between work organisation (associated with psychosocial health risks in Swedish OSH law) and technology (associated with physical health risks in Swedish OSH law). Regarding the second underlying problem, the Swedish model and new EU legislation, this study highlights how strategic action seemed to have been put on hold due to the long negotiations of the EU AI Act and Platform Work Directive. Ironically, another EU initiative, consisting of a campaign about OSH and digitalisation that started in 2023, appears to have had the opposite effect and spurred some action in the government OSH agencies.

Strategies

The trade unions were overwhelmingly sceptical of AM out of concern for risks that reflect those previously documented in the literature, including integrity breaches, work intensification, lack of autonomy, deskilling, social isolation, job insecurity, flawed systems, information asymmetries, and function creep (Kellogg et al Reference Kellogg, Valentine and Christin2020; Parent-Rocheleau and Parker Reference Parent-Rocheleau and Parker2022; Vignola et al Reference Vignola, Baron, Abreu Plasencia, Hussein and Cohen2023). The union representatives in this study argued that AM, in its current application, amplified existing risks akin to those arising from scientific management (Altenried Reference Altenried2019) and generated new ones, such as unprecedented forms of surveillance (Alizadeh et al Reference Alizadeh, Hirsch, Benlian, Wiener and Cram2023). However, the unions also held the view that algorithmic systems were not OSH hazards per se. It could therefore be argued that Swedish unions remain technology-neutral (De Vylder Reference De Vylder1996), viewing AM from a sociotechnical perspective (Jarrahi et al Reference Jarrahi, Newlands, Lee, Wolf, Kinder and Sutherland2021). Thus, employer and union actors agreed on the potential of AM for enabling purposes (Noponen et al Reference Noponen, Feshchenko, Auvinen, Luoma-aho and Abrahamsson2023), including improving OSH, even if their perspectives on job control are radically different, as demonstrated by the promotion of healthy discipline by managers. The trade unions believed that AM technologies had unrealised potential for improving OSH if information asymmetries were levelled by workers’ and unions’ access to data. This suggests an affinity with including the active participation of the government, workers, and their representatives in negotiations at all stages of AM implementation and configuration to mitigate or eliminate AM’s OSH risks.

Conclusion

This study bridges perspectives on the politics of AM (Krzywdzinski et al Reference Krzywdzinski, Schneiß and Sperling2024; Dupuis Reference Dupuis2024) and the OSH risks caused by AM by applying the PDR model in the Swedish IR context. Economic Pressure drives AM adoption and Reward Pressure built into the current productivity-enhancing design of AM incentivises trade unions to learn, inform, and bargain around AM. Disorganisation was present among all three actors in the ignorance of how AM affects OSH and, in the case of trade unions and government, the functioning of AM. This was likely due to the novelty and complexity of AM, and the suppression of workers’ ability to organise around the issue due to information asymmetries. Regulatory Failure resulted in part from this Disorganisation and the unwillingness to properly apply existing regulations to AM. The position of AM between work and technology makes it difficult to disentangle how regulation with a technology focus could be applied to OSH and how OSH regulation should be applied to technology. New EU regulations could have further complicated interpretation and stalled enforcement.

Our contribution lies in extending and modifying the PDR model, which we believe bridges shortcomings in both labour process theory and psychosocial health models that have been applied to AM, as it links structural and institutional power relations with worker health. The extension consists of applying it to an emerging phenomenon with important safety and health consequences, and to IR actors rather than workplaces or sectors. The modification consists of widening the dimension of Economic Pressure beyond the workplace to include market forces external to the organisation. In applying PDR to IR actors, we capture how Pressure, Disorganisation, and Regulatory Failure condition OSH strategies and highlight how stakeholders renegotiate regulations and AM use to address the OSH risks posed by AM.

In showing how Economic Pressures and work Disorganisation shaped stakeholder opportunities and motivation to engage with the potential risks related to AM, this paper opens a discussion on interventions – for example, through mitigating vulnerability to economic pressures through stable employment, disincentivising rule-breaking by employers through improved knowledge of regulations applying to AM, and levelling information asymmetries. Addressing extra-organisational drivers of unhealthy use of AM could prove more impactful than workplace-centred remedies often provided by psychosocial health theories like the Job-Demands Resources and Job-Control Support models (Quinlan Reference Quinlan2025).

Limitations and future research

One limitation is that the sample is small, and most of the empirical data come from trade unions. This is partly because their interest in AM and OSH exceeds that of the government and employers. The employer organisations were unwilling to participate in the follow-up interviews in 2024. Another limitation is the focus on logistics. Although this affects the transferability of the findings, our study nevertheless provides an empirical contribution in the form of in-depth insights into stakeholder perspectives and strategies in relation to AM and OSH in an early-adopter sector. Indeed, while differences in technologies and work organisation exist, the AM functions in logistics mirror those in, e.g., contact centres and health care (Doellgast et al Reference Doellgast, O’Brady, Kim, Walters, Acevedo, Dragsbaek, Hegeman, Ivanovski, Mccormick, Rana, Starcevic, Wagner and Kylasam Iyer2023b; Rani et al Reference Rani, Pesole and González Vázquez2024). The inclusion of government and central-level trade unions also demonstrates wider perspectives than sector-specific interests. In doing so, this study paves the way for future research exploring industrial relations in the context of AM. We encourage future studies to include more stakeholders in other non-platform sectors. There is also a need to investigate stakeholder strategies in other industrial relations models. Future studies could benefit from analysing the power resources available to different labour market actors, which shape their strategic options, as well as evaluating interventions that labour market actors implement to improve the work environment in algorithmically managed work.

Funding statement

This article is part of the research project AMOSH: Algorithmic management and occupational safety and health in logistics, funded by AFA Insurance.

Competing interests

The authors declare none.

Ruben Lind is a PhD candidate in occupational medicine at the Karolinska Institute, researching the effects of algorithmic management on safety and health in the ALGOSH research programme.

Karin Hennum Nilsson is a PhD candidate in occupational and environmental medicine and licensed psychologist, conducting her PhD research in the AMOSH project.

Pille Strauss is a postdoctoral researcher in the ALGOSH research programme at the Karolinska Institute. She holds a PhD in organisational health psychology from the Univerisity of Gothenburg.

Michael Quinlan is emeritus professor in industrial relations at the School of Management and Governance and Director of the Industrial Relations Research Centre. His major expertise is the field of occupational health and safety (OHS) and risk, particularly aspects related to work organisation, management and regulation. He is also part of the ALGOSH research programme.

Emma Brulin is an associate professor in occupational and environmental medicine and doctor of health sciences, conducting research on physical and psychosocial risk factors in the work environment, symptom development of stress-related diseases and rehabilitation for return to work in case of sick leave for burnout.

Min Kyung Lee is an assistant professor in the School of Information at the University of Texas at Austin. Dr. Lee has conducted some of the first studies that empirically examine the social implications of algorithms’ emerging roles in management and governance in society, looking at the impacts of algorithmic management on workers as well as public perceptions of algorithmic fairness. She is also part of the ALGOSH research programme.

Carin Håkansta is an associate professor in occupational medicine at the Karolinska Institute, and the principal investigator of the AMOSH and ALGOSH projects which explore algorithmic management, work environment, safety and health