Introduction

The introduction of glyphosate-resistant (GR) sugar beet in 2007 ushered in a new postemergence chemical weed control option for growers in North America (Green Reference Green2009). Field trials in Scottsbluff, Nebraska, confirmed that GR sugar beet resulted in improved weed control to about 95% compared with 55% to 90% in non-GR sugar beet, while minimizing crop injury and reducing herbicide costs (Kniss et al. Reference Kniss, Wilson, Martin, Burgener and Feuz2004). Kniss et al. (Reference Kniss, Wilson, Martin, Burgener and Feuz2004) observed that glyphosate applied postemergence two times to a GR sugar beet variety trial increased net return by US$435 ha−1 compared to any conventional or micro-rate herbicide program (repeated applications of low-dose herbicide mixture with oil adjuvants), although differences in seed costs were not available at the time of that research. Following commercialization, Kniss (Reference Kniss2010) documented a US$576 ha−1 advantage of GR sugar beet over conventional weed management practices, accounting for differences in herbicide, tillage, labor, and seed costs.

Given the constraints of conventional herbicides and the economic advantages of GR sugar beet, it was not surprising that the adoption of GR sugar beet was rapid after its commercialization. Except for California, 95% of sugar beet seeds sown in all sugar beet–growing states within the United States in the 2009/2010 crop year were GR, compared to the 60% sown in the 2008/2009 crop year (USDA-ERS 2021). By 2012, adoption rates across the United States had risen to 97% (James Reference James2012). Commercialization of GR sugar beet was an opportunity for growers to switch from intensive herbicide applications in conventional sugar beet to a less-intensive herbicide program (Morishita Reference Morishita2017). However, the overreliance on glyphosate for weed management in regions where sugar beet is grown has resulted in the selection for GR weeds.

By the end of 2008, 10 GR weed species had been reported in 29 states, including Michigan, Minnesota, Nebraska, and North Dakota, states where sugar beets are produced (Heap Reference Heap2024a, Reference Heap2024b). By 2024, at least one GR weed had been confirmed in sugar beet fields across the western sugar beet production region of Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Oregon, and Wyoming (Heap Reference Heap2024a); and Nebraska (Lawrence and Kniss Reference Lawrence and Kniss2021). Kochia, waterhemp [Amaranthus tuberculatus (Moq.) Sauer], and Palmer amaranth have become especially problematic in the western states where sugar beets are grown. GR waterhemp has been reported in Idaho and Nebraska; GR kochia in Idaho, Oregon, Wyoming (Heap Reference Heap2024b), Nebraska (Lawrence and Kniss Reference Lawrence and Kniss2021), and Colorado (Araujo et al. Reference Araujo, Westra, Shergill and Gaines2024); and GR Palmer amaranth in Colorado, Idaho (Heap Reference Heap2024b), and Nebraska (Lawrence and Kniss Reference Lawrence and Kniss2021). Dicamba-resistant Palmer amaranth has been reported in Colorado, Nebraska, and Wyoming (Araujo et al. Reference Araujo, Westra, Shergill and Gaines2024). Dicamba-resistant kochia has been reported in Colorado, Idaho, Montana, Nebraska, and North Dakota (Heap Reference Heap2024b).

Currently, available herbicide options for weed control in sugar beet crops are inadequate due to widespread glyphosate resistance reported in the western sugar beet production region (Beiermann et al. Reference Beiermann, Creech, Knezevic, Jhala, Harveson and Lawrence2021; Kumar et al. Reference Kumar, Felix, Morishita and Jha2018; Morishita Reference Morishita2017). Sugar beet growers in Idaho, Nebraska, Oregon, and Wyoming would benefit from alternative preemergence and postemergence herbicide options to control GR Palmer amaranth and kochia in fields where sugar beet is grown (Beiermann et al. Reference Beiermann, Creech, Knezevic, Jhala, Harveson and Lawrence2021; Schultz and Lawrence Reference Schultz and Lawrence2021).

Dicamba and glufosinate are herbicides used for weed control in dicamba- and glufosinate-resistant crops, with glufosinate providing nonselective postemergence weed control and dicamba providing selective control when applied preemergence or postemergence (Shaner Reference Shaner2014). In a research trial in Kansas, dicamba and glufosinate applied postemergence provided 90% control of GR Palmer amaranth, with 8% improvement in control when dicamba applied postemergence was followed by an application of glufosinate to dicamba-, glyphosate-, and glufosinate-resistant soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] (Liu et al. Reference Liu, Kumar and Lambert2022). Similarly, Striegel et al. (Reference Striegel, Eskridge, Lawrence, Knezevic, Kruger, Proctor, Hein and Jhala2020) reported >95% control of Palmer amaranth, common lambsquarters, velvetleaf (Abutilon theophrasti Medik.), bristly foxtail (Setaria verticillata L.), giant foxtail (Setaria faberi Hermm.), yellow foxtail [Setaria pumila (Poir.) Reom. and Schult.], large crabgrass [Digitaria sanguinalis (L.) Scop.], and field sandbur [Cenchrus longispinus (Hack.) Fernald.] by dicamba + glyphosate and glufosinate applied postemergence to soybean field trials in Nebraska.

A triple-stacked dicamba-, glufosinate-, and glyphosate-resistant sugar beet trait (Truvera) is currently being developed by KWS Seeds, LLC (Bloomington, MN) in cooperation with Bayer (St. Louis, MO), to provide additional options for controlling GR weeds and difficult-to-control broadleaf weeds that grow among sugar beet plants (Felix Reference Felix2022). The objective of this research was to compare various preemergence and postemergence combinations of dicamba, glufosinate, and glyphosate for weed control in sugar beet.

Materials and Methods

Site Description

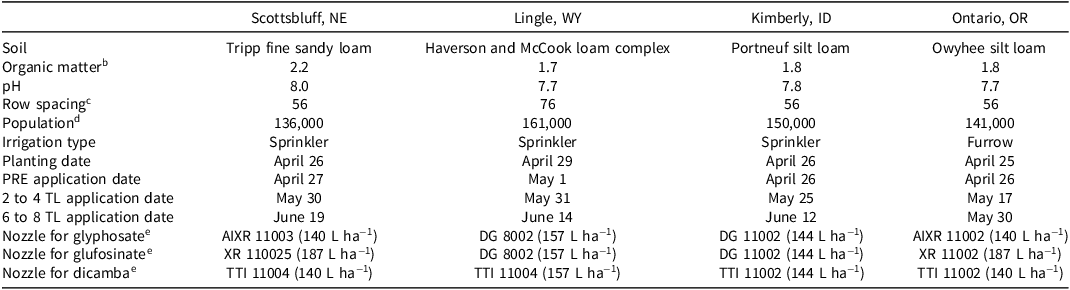

Regulated field trials were conducted to evaluate weed control at four locations: University of Nebraska-Lincoln Panhandle Research and Extension Center near Scottsbluff, Nebraska (41.89°N, 103.68°W); University of Wyoming James C. Hageman Sustainable Agriculture Research and Extension Center near Lingle, Wyoming (42.13°N, 104.39°W); University of Idaho Kimberly Research and Extension Center near Kimberly, Idaho (42.55°N, 114.35°W); and Oregon State University, Malheur Experiment Station, Ontario, Oregon (43.98°N, 117.02°W) in 2023. The soils and organic matter (OM) of soils across trial sites ranged from a Haverson fine loam (mesic Aridic Ustifluvents) with 1.7% OM near Lingle, Wyoming; Tripp fine sandy loam (mesic Aridic Haplustolls) with 2.2% OM in Scottsbluff, Nebraska; Portneuf silt loam (mesic Durinodic Xeric Haplocalcids) with 1.8% OM in Kimberly, Idaho; and Owyhee silt loam (mesic Xeric Haplocalcids) with 1.8% OM near Ontario, Oregon (Table 1). Irrigation was necessary to produce sugar beet at all locations. In Oregon, furrow irrigation was used, while at the remaining sites, overhead irrigation was used (Table 1). The trial site near Scottsbluff, Nebraska, had a natural infestation of common lambsquarters and GR Palmer amaranth. The remaining trial sites had natural infestations of common lambsquarters, redroot pigweed, and GR kochia.

Table 1. Site description of trial locations, herbicide application timing, and spray nozzles used in sugar beet weed control trial in 2023. a

a Abbreviatons: PRE, preemergence; TL, true leaf sugar beet growth stage.

b Organic matter content is presented as a percent.

c Row spacing is presented in centimeters.

d Population is presented as plants per hectare.

e Spray nozzles were supplied by TeeJet Technologies (Glendale Heights, IL). Spray volumes are shown in parentheses.

Experimental Design and Herbicide Treatment

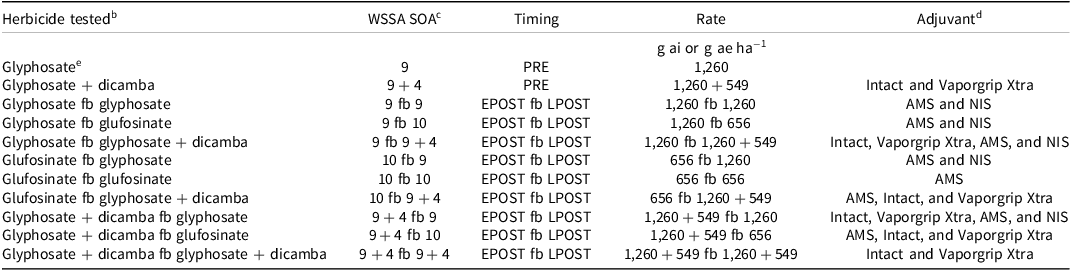

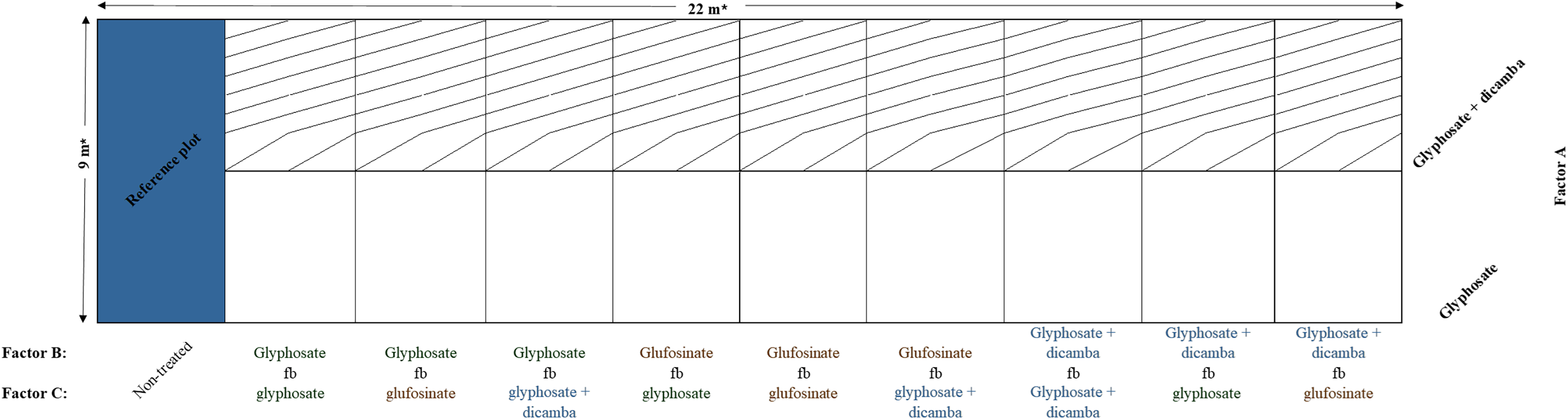

This trial was designed as a three-way factorial (preemergence herbicides by early postemergence herbicide by late postemergence herbicide combinations), randomized complete block design, set as a strip-split-plot design, along with two comparison treatments: preemergence (dicamba + glyphosate or glyphosate applied alone) + no postemergence (all possible combinations of dicamba + glyphosate, glufosinate, and glyphosate), and a nontreated plot with four replications at each trial location. Preemergence herbicides were set in strips, while early and late postemergence herbicides were set as split-plots (Table 2 and Figure 1).

Table 2. Common names, trade names, WSSA classification, application timing, rate, adjuvants, and manufacturers of herbicides evaluated in the sugar beet study. a

a Abbreviations: AMS, ammonium sulfate; EPOST, early postemergence applied at the 2 to 4 true leaf stage of sugar beet; fb, followed by; LPOST, late postemergence applied at the 6 to 8 true leaf stage; NIS, nonionic surfactant; PRE, preemergence; SOA, site of action; WSSA, Weed Science Society of America.

b Herbicide manufacturers: glyphosate (Roundup PowerMax; Bayer CropScience, St. Louis, MO); dicamba (XtendiMax; Bayer CropScience); glufosinate (Liberty 280 SL; BASF Corporation, Research Triangle Park, NC).

c See Shaner (Reference Shaner2014).

d Adjuvants: NIS, 2.5 mL L−1; AMS, 18 g L−1; Intact (Precision Laboratories, Waukegan, IL), 5 mL L−1; VaporGrip Xtra (Bayer CropScience), 1.46 L ha−1. Glyphosate applied postemergence was mixed with AMS and NIS. Dicamba + glyphosate was applied with Intact and Vaporgrip Xtra; and glufosinate was mixed with AMS only.

e Glyphosate was applied alone PRE as a burndown to control existing weeds.

Figure 1. Experimental design indicating a randomized complete block design arranged as a three-way factorial: Factor A, preemergent herbicide application; Factor B, postemergence herbicide application at the 2 to 4 true leaf stage of sugar beet; Factor C, postemergence herbicide application at the 6 to 8 true leaf stage of sugar beet.

Abbreviation: fb.

* Plot dimensions varied depending on location, featuring 22 m wide by 9 m long in Scottsbluff, Kimberly, and Ontario; and 30 m wide by 9 m long in Lingle.

The whole-plot treatments encompassed the entire width of the study block, with dimensions varying by study location (Figure 1). Whole-plot treatments were applied across the entire block, spanning 22 m wide by 9 m long in Scottsbluff, Kimberly, and Ontario; and 30 m wide by 9 m long in Lingle (Figure 1). Split-plots were assigned perpendicularly to the whole-plot across all locations. Split-plot dimensions were 2.2 m wide by 9 long in Scottsbluff, Kimberly, and Ontario; and 3 m wide by 9 m long in Lingle.

Preemergence herbicides were applied on the same day of planting or within 3 d after planting, depending on trial location (Table 1), due to variation in environmental conditions such as wind at the time of planting. Early postemergence herbicide treatments were applied when sugar beet reached the 2 to 4 true leaf (TL) growth stage at each trial location, as determined by hand-counting true leaves on five randomly selected plants in the nontreated plot. Late postemergence herbicides were applied when sugar beet reached the 6 to 8 TL growth stage (Table 2). The rates of glyphosate + dicamba, glyphosate, and glufosinate were the same across treatments, and all possible combinations of preemergence and early-and late postemergence herbicide treatments were included, resulting in a balanced three-way factorial design.

Sugar beet was planted between April 25 and 29, 2023, at densities between 136,000 and 161,000 seeds ha−1 in 56 cm or 76 cm row spacing, depending on study location (Table 1). Planting dates, seeding rates, and plant spacing were within the typical range for sugar beet production in the western sugar beet production regions of Idaho, Nebraska, Oregon, and Wyoming (Adjesiwor, Reference Adjesiwor2025; Adjesiwor et al. Reference Adjesiwor, Felix and Morishita2021; Kniss et al. Reference Kniss, Sbatella and Wilson2012; Yonts et al. Reference Yonts, Wilson, Smith, Wilson, Smith and Jasa2013).

Glyphosate applied postemergence was mixed with 18 g of ammonium sulfate per liter and 2.5 mL L−1 nonionic surfactant (Table 2). Dicamba + glyphosate tank-mixture was mixed with 5 mL L−1 of Intact (Precision Laboratories, Waukegan, IL), and 1.46 L ha−1 of Vaporgrip Xtra (Bayer CropScience St. Louis, MO). Glufosinate was mixed with 18 g of ammonium sulfate per liter (Table 2). Preemergence and postemergence herbicide treatments evaluated near Scottsbluff, Kimberly, and Ontario, and postemergence treatments in Lingle were applied using a CO2-pressurized backpack sprayer, while preemergence treatments were applied using a tractor-mounted compressed-air sprayer. Applications with the tractor-mounted compressed-air sprayer were made at a constant speed of 6 km h−1 with the spray boom maintained 51 cm above the ground, while CO2-pressurized backpack sprayer applications were made at 5 km h−1 with the spray boom maintained at 46 cm above the ground. Herbicide spray volume and TeeJet nozzles (TeeJet Technologies, Glendale Heights, IL) used varied by trial location (Table 1).

Data Collection

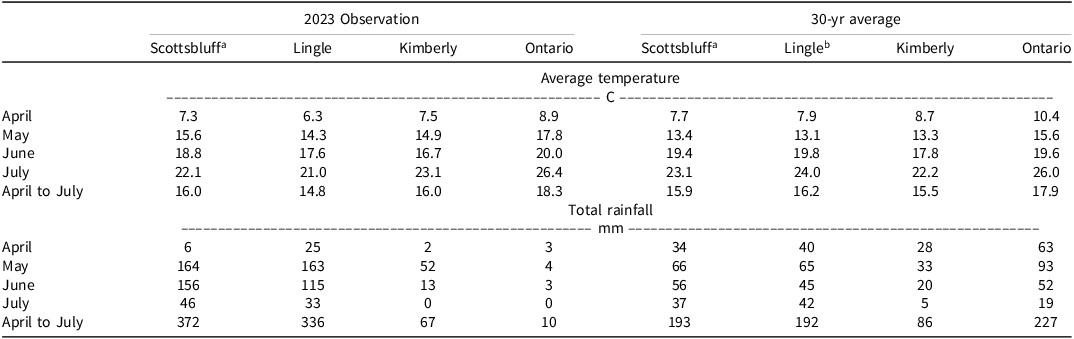

Temperature and rainfall for the trial period and 30-yr averages for Scottsbluff, Kimberly, and Ontario, together with a 23-yr average for the Lingle location were obtained from the nearest weather station (Table 3). Weed density was assessed on the day of the late postemergence application, and 16 and 28 (±3) d after the late postemergence application, depending on trial location. Two 0.5-m2 quadrats were randomly placed in each split-plot and weeds were identified by species and counted. Trials were terminated following weed control evaluation, and yield was not determined under the terms of trial regulations.

Table 3. Estimated average monthly air temperature and total rainfall during the 2023 growing season compared with 30-yr averages.

a Air temperature and precipitation data were collected from the High Plains Regional Climate Center weather station, located within 1 km of the experiment. Source: (https://hprcc.unl.edu/).

b Data for Lingle are the 23-yr average.

Statistical Analysis

Data were analyzed using R statistical software (v. 4.4.1; R Core Team 2023). Common lambsquarters, redroot pigweed, and kochia density (plants m−2) across the Lingle, Kimberly, Scottsbluff, and Ontario locations were analyzed using a linear mixed-effects model (LMM) with the lmer function in the lme4 package version 1.1-37 (Bates et al. Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015). Palmer amaranth density (plants m−2) was analyzed using linear model (LM) with the lm function in the stats package (v. 4.4.1; R Core Team 2024), because Palmer amaranth was present at the Scottsbluff location only and blocking criteria (random effect) did not improve the model. Interaction effect between preemergence and early and late postemergence factors were set as fixed effect in both LMM and LM (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015; R Core Team 2024), and study location as random effect in the LMM (Bates et al., Reference Bates, Maechler, Bolker and Walker2015). Analysis of Variance was performed using Type III sum of squares for the LMM, and Type I sum of squares for the LM, due to the difference in error structure provided by the model (Kniss and Streibig Reference Kniss and Streibig2018). All tests were performed at a 0.05 significance level using the anova function in the lmerTest package (v. 3.1-3; Kuznetsova et al. Reference Kuznetsova, Brockhoff and Christensen2017). ANOVA assumptions of normality and homogeneity of variances (homoscedasticity) were tested by visually inspecting Pearson’s residuals versus fitted values and sample versus theoretical quartiles plots (Onofri et al. Reference Onofri, Carbonell, Piepho, Mortimer and Cousens2010). In the presence of a significant effect of early and late postemergence and preemergence treatment factors or an interaction between any of the aforementioned factors, post hoc mean separation was conducted at a 5% significance level using the emmeans function in the emmeans package (v. 2.0.0) within the significant treatment factors (Lenth and Piaskowski Reference Lenth and Piaskowski2025). Compact letter display was generated within the significant factors using the cld method for emmGrid objects, which applies the Piepho (Reference Piepho2004) algorithm to summarize statistically distinct treatment means based on pairwise comparisons. The nontreated check was excluded from statistical analysis to avoid an unbalanced ANOVA; however, the check plot was included in mean separation tables as a reference, because it provides important context for interpreting treatment effects.

Results and Discussion

The use of postemergence treatments reduced weed density by 39% to 98% relative to the nontreated check for every weed species. The discussion will focus on differences between treatments that contained a herbicide and mean of nontreated check plots will be presented in all tables as a reference.

Common Lambsquarters

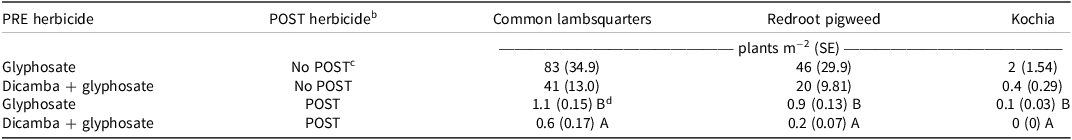

Preemergence herbicide application significantly affected common lambsquarters density (P < 0.05) (Table 4). Dicamba + glyphosate applied preemergence reduced common lambsquarters density by 45% compared with glyphosate alone (Table 5). These results corroborate previous findings by Fuerst et al. (Reference Fuerst, Barrett and Penner1986) who reported control of common lambsquarters by dicamba applied preemergence to corn (Zea mays L.).

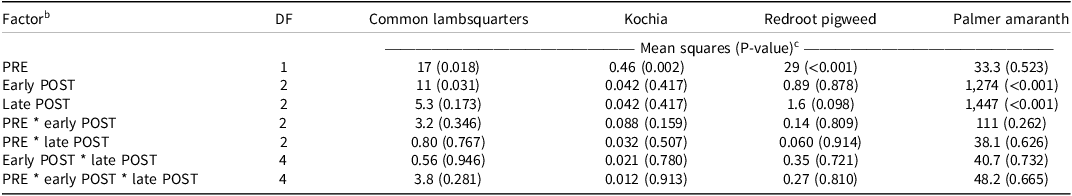

Table 4. Partial analysis of variance for the effect of herbicide application timings on weed density in Truvera sugar beet field trials. a

a Abbreviations: DF, degrees of freedom; POST, postemergence; PRE, preemergence.

b POST herbicides were applied at the 2 to 4 true leaf stage; late POST herbicides were applied at the 6 to 8 true leaf stage. PRE * early POST indicates an interaction effect between PRE and early POST; PRE * late POST indicates an interaction effect between PRE and late POST; early POST * late POST indicates an interaction effect between early and late POST; PRE * early POST * late POST indicates an interaction effect between PRE, early, and late POST herbicide applications.

c P-values were based on chi-square tests for common lambsquarters, kochia, redroot pigweed, and Palmer amaranth.

Table 5. Common lambsquarters, redroot pigweed, and glyphosate-resistant kochia density as affected by pre- and postemergence herbicides in field trials. a – d

a Abbreviations: POST, postemergence; PRE, preemergence; SE, standard error.

b POST includes all POST treatments (glyphosate, glufosinate, and dicamba) combined.

c Comparison treatments with no POST herbicides are presented for reference, but were excluded from the statistical analysis to maintain a balanced design.

d Estimated means (within a column) followed by the same letter indicates no significant difference between treatments at α = 0.05.

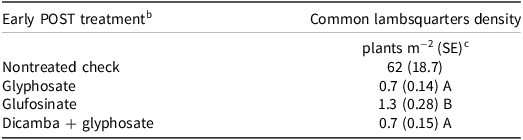

There was a significant effect of early postemergence treatment on common lambsquarters density (Tables 4 and 6). Glyphosate, glufosinate, and glyphosate + dicamba applied early postemergence resulted in similar common lambsquarters density (Table 6). Our results differ from those observed in a greenhouse study when glyphosate + dicamba applied postemergence improved control of GR common lambsquarters by >90% relative to glyphosate applied alone (Chahal and Johnson Reference Chahal and Johnson2012). Previous research trials have shown that common lambsquarters is effectively controlled by glyphosate or glufosinate applied postemergence in susceptible populations. For example, Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Yonts and Smith2002) reported >70% common lambsquarters control in a glufosinate- and glyphosate-resistant sugar beet trial in Nebraska. Similarly, glufosinate applied early followed by late postemergence provided 74% common lambsquarters control in glufosinate-resistant soybean (Aulakh and Jhala Reference Aulakh and Jhala2015).

a Abbreviations: POST, postemergence; PRE, preemergence; SE, standard error.

b Early POST herbicide treatments were applied at the 2 to 4 true leaf stage of dicamba, glyphosate, and glufosinate-resistant sugar beet.

c Estimated means (within a column) followed by the same letter indicates no significant difference treatments at α = 0.05. SE indicates the standard deviation of the sample mean. The nontreated check is included in the mean separation table as a reference, however, it was excluded from statistical analysis to avoid an unbalanced ANOVA.

Palmer Amaranth

Dicamba + glyphosate applied preemergence did not significantly reduce GR Palmer amaranth density at Scottsbluff (Table 4). In contrast, dicamba applied preemergence was reported to provide >90% Palmer amaranth control (Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Norsworthy, Young, Steckel, Bradley, Johnson, Loux, Davis, Kruger, Mohammad, Ikley, Douglas and Thomas2015). Cahoon et al. (Reference Cahoon, York, Jordan, Everman, Seagroves, Culpepper and Eure2015) also reported significant control of Palmer amaranth by dicamba included in a tank-mix partner with acetochlor relative to acetochlor applied alone preemergence. In a similar trial, glyphosate + dicamba applied preemergence did not influence the control of GR waterhemp [Amaranthus tuberculatus (Moq.) Sauer] (Hedges et al. Reference Hedges, Soltani, Hooker, Robinson and Sikkema2019). Given the low rainfall and moderate temperature in Scottsbluff at the time of preemergence application (Tables 1 and 3), conditions that enhance the persistence and residual effect of dicamba (Smith Reference Smith1973), the reduced efficacy of dicamba + glyphosate applied preemergence on GR Palmer amaranth could be attributed to the dissipation of dicamba at the time of GR Palmer amaranth emergence. Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Young, Matthews, Marquardt, Slack, Bradley, York, Culpepper, Hager, Al-Khatib, Steckel, Moechnig, Loux, Bernards and Smeda2010) reported 98% and 90% control of early emerging weeds: common lambsquarters and horseweed (Erigeron canadensis L.), respectively, by dicamba applied preemergence. However, weed control of late-emerging weeds: velvetleaf, Palmer amaranth, common waterhemp, giant ragweed (Ambrosia trifida L.), and ivyleaf morningglory (Ipomoea hederacea Jacq.) was less than 60%.

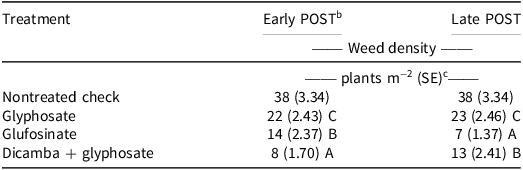

All early and late postemergence treatments significantly affected GR Palmer amaranth density (Table 4). Differences among treatments were observed with Palmer amaranth density reduction at 2 to 4 TL and 6 to 8 TL applications (P < 0.001 for each). Dicamba + glyphosate and glufosinate reduced GR Palmer amaranth density by 64% and 36%, respectively, relative to glyphosate applied alone, when sprayed at the 2 to 4 TL stage, while application of dicamba + glyphosate and glufosinate applied at the 6 to 8 TL sugar beet stage reduced GR Palmer amaranth density by 43% and 70%, respectively, relative to glyphosate-alone (Table 7). Palmer amaranth control by dicamba + glyphosate declined by 21% between the 2 to 4 TL and 6 to 8 TL sugar beet stages. The decline in dicamba + glyphosate efficacy can be attributed to regrowth of Palmer amaranth after the early postemergence application and an increase in size of Palmer amaranth at the time of the late postemergence application, which could be due to high rainfall weeks preceding late postemergence application (Tables 1 and 3). Our observation agrees with reports that dicamba activity decreases as Palmer amaranth increases in size and that regrowth from axillary buds is common after failed herbicide exposure (Cuvaca et al. Reference Cuvaca, Currie, Roozeboom, Fry and Jugulam2020; Meyer et al. Reference Meyer, Norsworthy, Young, Steckel, Bradley, Johnson, Loux, Davis, Kruger, Mohammad, Ikley, Douglas and Thomas2015).

Table 7. Palmer amaranth density in response to early and late POST herbicide treatment in a field trial conducted near Scottsbluff, Nebraska. a

a Abbreviations: POST, postemergence; SE, standard error.

b Early POST herbicide treatments were applied at the 2 to 4 true leaf stage; late POST herbicide treatments were applied at the 6 to 8 true leaf stage of dicamba, glyphosate, and glufosinate-resistant sugar beet.

c Estimated means (within a column) followed by the same letter indicates no significant difference treatments at α = 0.05. SE indicates the standard deviation of the sample mean. A nontreated check was included in the mean separation table as a reference, however, it was excluded from statistical analysis to avoid an unbalanced ANOVA.

Conversely, control by glufosinate alone increased by 34% during this period. The enhanced late postemergence activity of glufosinate may be attributed to larger weed leaf surface area above the sugar beet canopy, thereby improving glufosinate contact. At the 2 to 4 TL spray timing, Palmer amaranth have been too small, which reduced the ability of glufosinate to contact the weed. Consistent with our observation, Steckel et al. (Reference Steckel, Wax, Simmons and Phillips1997) observed effective common lambsquarters and common cocklebur (Xanthium strumarium L.) control when glufosinate was applied when weeds were 10 cm tall compared with 5 cm.

In contrast to our findings, Vann et al. (Reference Vann, York, Cahoon, Buck, Askew and Seagroves2017) observed up to 8% decline and 20% increase in Palmer amaranth control by glufosinate alone and dicamba treatments, respectively. Similar to our observation, Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Kumar and Lambert2022) reported sequential postemergence application of glufosinate and glufosinate followed by dicamba provided >85% control of GR Palmer amaranth in XtendFlex soybean. The consistent observations may be due to the use of postemergence combinations with different sites of action (SOAs). The use of effective herbicide SOA mixtures has the potential to improve herbicide resistance management and sustainability of herbicide-tolerant crops (Kniss et al. Reference Kniss, Mosqueda, Lawrence and Adjesiwor2022). Similar to our findings, the use of multiple SOAs reduced GR Palmer amaranth density in glyphosate- and glufosinate-resistant soybean (Miller and Norsworthy Reference Miller and Norsworthy2016; Shyam et al. Reference Shyam, Chahal, Jhala and Jugulam2021).

The highest Palmer amaranth density occurred when glyphosate was applied alone compared to other postemergence applications (Table 7), as was expected, given that Palmer amaranth at the Scottsbluff location is resistant to glyphosate (Lawrence and Kniss Reference Lawrence and Kniss2021). Norsworthy et al. (Reference Norsworthy, Korres, Walsh and Powles2016) reported ≥80% control of GR Palmer amaranth with glufosinate-based treatments compared to glyphosate-based treatments. Liu et al. (Reference Liu, Kumar and Lambert2022) found that glyphosate-only treatments used on XtendFlex soybean did not manage GR Palmer amaranth.

Although dicamba + glyphosate applied preemergence did not reduce Palmer amaranth density, integrating a preemergence herbicide may enhance the efficacy of postemergence applications and reduce GR Palmer amaranth density when emergence occurs earlier in the year (Norsworthy et al. Reference Norsworthy, Korres, Walsh and Powles2016).

Kochia

Dicamba + glyphosate applied preemergence significantly affected kochia density (P < 0.01) (Tables 4 and 5). A preemergence application of dicamba has been described as the foundation of kochia control; however, a follow-up postemergence herbicide application is needed to ensure season-long kochia control (Kumar and Jha Reference Kumar and Jha2015). Ou et al. (Reference Ou, Thompson, Stahlman and Jugulam2018) reported similar findings, when dicamba applied preemergence controlled more than 90% of dicamba-resistant (DR) kochia in XtendFlex soybean. Brachtenbach (Reference Brachtenbach2015) observed more than 83% kochia mortality when dicamba was applied preemergence.

We observed no significant effect of postemergence treatments on kochia density (Table 4). This may be due to low kochia density at the time of postemergence applications; most kochia plants that were present were controlled by a preemergence application early in the season. However, in situations in which kochia emerges after a preemergence herbicide application has dissipated, postemergence applications would be needed to control kochia. In the literature, dicamba applied postemergence has been reported to control dicamba-susceptible kochia population by up to 80% (Ou et al. Reference Ou, Thompson, Stahlman and Jugulam2018).

Redroot Pigweed

Redroot pigweed density was significantly affected by dicamba + glyphosate applied preemergence (P < 0.001) (Table 4). Dicamba + glyphosate applied preemergence reduced redroot pigweed density by 78% relative to glyphosate alone (Table 5). Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Young, Matthews, Marquardt, Slack, Bradley, York, Culpepper, Hager, Al-Khatib, Steckel, Moechnig, Loux, Bernards and Smeda2010) reported 50% redroot pigweed control when dicamba was applied preemergence. However, in that study, dicamba applied preemergence followed by subsequent dicamba applications further improved redroot pigweed control by an additional 45% or more (Johnson et al. Reference Johnson, Young, Matthews, Marquardt, Slack, Bradley, York, Culpepper, Hager, Al-Khatib, Steckel, Moechnig, Loux, Bernards and Smeda2010).

Late postemergence applications did not influence redroot pigweed control (Table 4). This may be due to good suppression of emergence by herbicides applied preemergence and the absence of late flushes of redroot pigweed after preemergence herbicides had dissipated. In the literature, Wilson et al. (Reference Wilson, Yonts and Smith2002) has reported ≥69% control of redroot pigweed by applications of glyphosate and glufosinate.

At all locations, common lambsquarters was the most common weed species, likely due to its early and wider emergence window compared to other early emerging weeds observed. The early emergence of common lambsquarters may also explain the effectiveness of dicamba + glyphosate applied preemergence at all locations. Similarly, Johnson et al. (Reference Johnson, Young, Matthews, Marquardt, Slack, Bradley, York, Culpepper, Hager, Al-Khatib, Steckel, Moechnig, Loux, Bernards and Smeda2010) reported 98% control of common lambsquarters when dicamba was applied preemergence to dicamba-resistant soybean. Fuerst et al. (Reference Fuerst, Barrett and Penner1986) reported control of common lambsquarters by dicamba applied preemergence.

Dicamba + glyphosate, glyphosate alone, or glufosinate applied early postemergence reduced common lambsquarters density. Similar to our observations, Oliveira et al. (Reference Oliveira, Feist, Eskelsen, Scott and Knezevic2017) reported broadleaf weed control by using different herbicide mode of action combinations in glyphosate- and glufosinate-tolerant soybean. The advantage of preemergence followed by postemergence herbicide treatments with multiple effective modes of action for broadleaf weed control has been previously documented (Jhala et al. Reference Jhala, Sandell, Sarangi, Kruger and Knezevic2017).

Practical Implications

Truvera sugar beet that is resistant to dicamba, glufosinate, and glyphosate will provide growers with additional herbicide options for the control of common lambsquarters, GR kochia, redroot pigweed, and GR Palmer amaranth. A preemergence application of dicamba will provide a residual effect to suppress weed emergence until postemergence herbicides are applied, and this will reduce selection pressure for glyphosate resistance in stand-alone glyphosate systems. Also, dicamba applied preemergence could extend the effectiveness of postemergence treatment applications (Knezevic et al. Reference Knezevic, Elezovic, Datta, Vrbnicanin, Glamoclija, Simic and Malidza2013). Results from this study suggest that postemergence applications of glufosinate and a tank-mixture of glyphosate + dicamba would manage GR Palmer amaranth, relative to glyphosate-only applications. Despite the uncertainties surrounding future dicamba labels allowing postemergence applications to dicamba-resistant crops, dicamba applied preemergence will provide improved weed control in sugar beet, while postemergence applications of glufosinate will improve control of GR Palmer amaranth (Bayer 2025).

Based on the findings of this trial, Truvera sugar beet will allow additional SOAs to be used both preemergence and postemergence, providing improved weed control compared to currently available technology. Stewardship of the Truvera sugar beet trait will be important for growers to diversify their weed management efforts that include mechanical and cultural weed control practices to reduce the selection for glyphosate-, dicamba-, and glufosinate-resistant weed populations.

Acknowledgments

Sugar beet seeds for this research were provided by KWS Seeds, Inc., and adjuvants and herbicides used for the study were provided by Bayer CropScience. We thank the two anonymous reviewers whose comments improved the quality of this manuscript.

Funding

Funding for this research was provided by KWS Seeds, Inc.

Competing Interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.