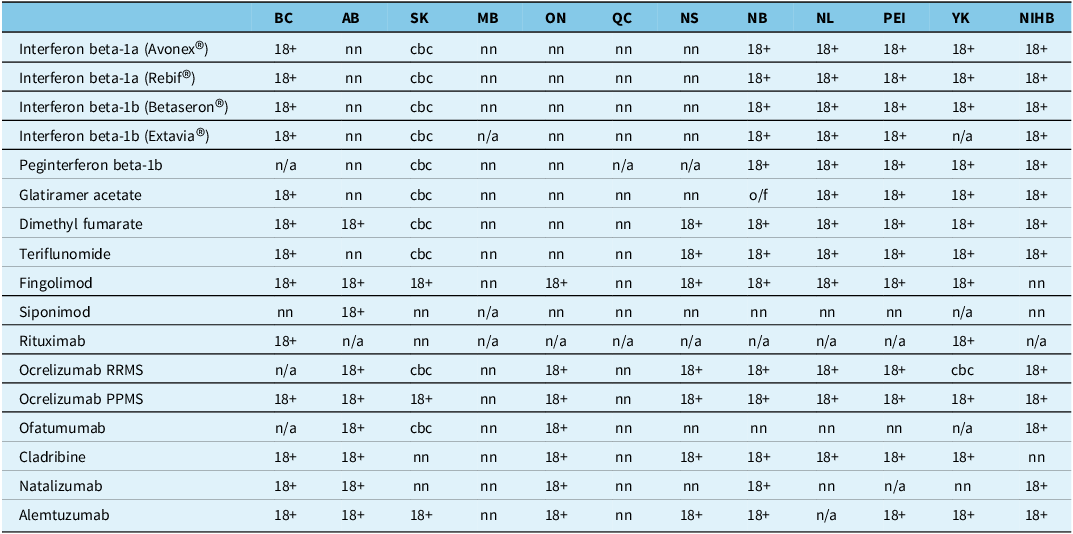

Government drug plan policies often provide access to the disease-modifying therapies (DMTs) used to treat multiple sclerosis (MS) only to those ≥ 18 years old. Reference Glennie1 Current Canadian drug plan policies provide a salient example of such age-related restrictions (Table 1). However, 5–10% of individuals with MS have disease onset < 18 years old Reference Yan, Balijepalli, Desai, Gullapalli and Druyts2 and reach key disability milestones at younger ages. Reference Renoux, Vukusic and Mikaeloff3,Reference Jakimovski, Awan, Eckert, Farooq and Weinstock-Guttman4 Strong evidence exists that early, effective DMT use limits long-term disability in pediatric-onset MS (POMS). Reference Benallegue, Rollot and Wiertlewski5 It is important to determine whether drug plan medication access restrictions are creating barriers to the appropriate treatment of POMS.

Table 1. Summary of multiple sclerosis disease-modifying therapy age restriction policies by Canadian government drug plans (as of June 18, 2025)

18+ = for adult patients 18 years or older; n/a = not available/not funded; nn = not noted, no explicit age criteria in the public domain; cbc = case-by-case consideration of requests for patients < 18 years old; o/f = on formulary, no prescribing restrictions.

Other abbreviations: AB = Alberta; BC = British Columbia; MB = Manitoba; NB = New Brunswick; NIHB = Non-Insured Health Benefits (i.e., for First Nations and Inuit people); NL = Newfoundland; NS = Nova Scotia; ON = Ontario; PEI = Prince Edward Island; PPMS = primary progressive MS; QC = Quebec; RRMS = relapsing-remitting MS; SK = Saskatchewan; YK = Yukon.

To better define and document the challenges associated with accessing medications for POMS, an online Canada-wide survey of DMT-related access was distributed via the Canadian Network of MS Clinics (CNMSC) as well as to prescribers at Canadian pediatric hospitals treating POMS (November 2022–May 2023). The challenges assessed via the survey focused on the ability of clinicians to secure funding for and/or access to DMTs for POMS via drug plans (e.g., government or private payer) or compassionate use programs (CUPs).

In terms of results, 19 clinicians responded, representing almost all provinces – 37% from Ontario (7/19); 16% from Alberta (3/19); 10% (2/19) each for Manitoba, Quebec and Nova Scotia; and 5% (1/19) each for British Columbia, Saskatchewan and Newfoundland. Respondent practice settings included adult MS clinics (7/19; 37%), specialized POMS clinics (6/19; 32%) and general pediatric neurology clinics (6/19; 32%).

The survey found that 6/19 (30%) of practitioners were not able to access DMTs for POMS. Those that were able to access these medications leveraged one of three mechanisms: private payer drug plans, government drug plans or pharmaceutical company CUPs. Patterns of DMT access differed among these mechanisms. For instance, first-generation DMTs (e.g., beta-interferon, glatiramer acetate) appeared to be easier to access via government drug plans than second-generation DMTs (e.g., ocrelizumab). In contrast, survey results indicated that at least one respondent was able to access a given DMT via a private drug plan, except in the case of cladribine and alemtuzumab. Access through CUPs was reported for 17/21 (80%) of DMTs evaluated, with ocrelizumab and natalizumab being the therapies most frequently accessed via this mechanism.

In terms of specific DMTs, B-cell depletors – specifically, ocrelizumab, ofatumumab and rituximab – were the most challenging products for clinicians to access (Figure 1). Access issues also differed by age: 10/19 (53%) and 13/19 (68%) respondents noted challenges accessing DMTs for patients < 10 and between 10 and 16 years old, respectively, while only 7/19 (37%) respondents had challenges for 17-year-olds.

Figure 1. Disease-modifying therapy access challenges. MS = multiple sclerosis.

DMT access for POMS was variable across Canada, raising health equity concerns and barriers to optimal care. Understanding the underlying causes of this variability is important in order to drive effective policy change.

Canada, like many parts of the world, does not have a regulatory framework that requires submission of pediatric data and formulations, even when pediatric use is anticipated. Reference Gilpin, Bérubé and Moore-Hepburn6 As a result, most DMTs prescribed in POMS are used off-label, with only fingolimod having regulatory approval for pediatric use in Canada. 7 The absence of pediatric-specific regulatory approval also has negative downstream impacts on government drug plan reimbursement of products. Lack of regulatory approval traditionally precludes an evaluation and funding recommendation by Canadian health technology assessment bodies. In the absence of such a recommendation, there is no formal funding – and, thus, no patient access – through government drug plans.

Some Canadian government drug plans have created case-by-case review mechanisms to address off-label use (see Table 1). In such cases, the clinician must make a submission and present the case to support funding of a specific drug in a specific patient. Some survey respondents (data not shown) cited sporadic case-by-case approval of access to some DMTs, despite the fact that published drug plan criteria are silent on age and/or prevent access for patients < 18 years old. Government drug plan policy changes to explicitly enable case-by-case review of drug access requests for those under 18 years old (e.g., as per Saskatchewan) would improve transparency and potentially enable equity of access to DMTs for this population.

Responding clinicians were leveraging all options available – including private drug plans, government drug plans and/or CUPs – to secure access to DMTs for their pediatric patients in Canada. The degree of access to DMTs for POMS was highly variable and inconsistent by DMT and/or by jurisdiction, raising health equity concerns. Differences in access between government and private drug plans create inherent inequity for patients who rely on government drug programs, based on their economic status.

In terms of limitations, while efforts were made to ensure that the survey reached all Canadian POMS DMT prescribers, it was possible that some were missed. Future studies could consider in-depth interviews with more detailed and qualitative reporting to better understand the nuances of DMT access challenges in this patient population. Areas such as the level of effort required to get access for a specific DMT, success rates for access to first- versus second-generation DMTs, financial barriers or other delays in access or administration would be of value to examine in future work.

To summarize, DMT access for POMS was challenging and highly variable across Canada, raising health equity concerns and creating potential barriers to optimal care. The survey results show some of the challenges associated with accessing DMTs in POMS.

These data will be used to engage government policy makers with recommendations to improve DMT access for POMS across Canada, to ensure transparent, consistent and evidence-based DMT access for POMS across the country. The Canadian experience may also provide insights into an issue that is relevant to many regions worldwide.

Author contributions

Conceptualization: BC, JJ, PS, HT, EAY

Methodology: JG, BC, JJ, HT, EAY

Data Collection: ME

Analysis: ME, JG

Writing: JG

Review and Editing: LS, BC, JJ, HT, EAY

Funding statement

This work was carried out under the auspices of the Pediatric Subgroup of the CNMSC Drug Access Working Group Project, which is sponsored through unrestricted grants from Amgen Canada Inc., Biogen Canada Inc., EMD Serono Inc., Novartis Pharmaceuticals Inc., Hoffman-LaRoche Limited and Sanofi Genzyme Inc. This funding provided support for the research, analysis, engagement and project management requirements of this initiative.

Competing interests

-

Judith Glennie (JG) is a consultant to the CNMSC, with work for this project funded via unrestricted grants from Amgen Canada Inc., Biogen Canada Inc., EMD Serono Inc., Novartis Pharmaceuticals Inc., Hoffman-LaRoche Limited and Sanofi Genzyme Inc. This funding provided support for the research, analysis, engagement and project management requirements of this initiative.

-

Lauren Strasser (LS): The author has received a SPRINT endMS Grant and a CMSC MS Mentorship Scholarship.

-

Beyza Ciftci (BC): The author participated in an Amgen NMOSD medical advisory board meeting.

-

Joley Johnstone (JJ): The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

-

Michelle Eisner (ME): The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

-

Penelope Smyth (PS): The author declares no potential conflicts of interest with respect to the research, authorship and/or publication of this article.

-

Helen Tremlett (HT): The author has received research support from the National Multiple Sclerosis Society, the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, MS Canada, the Multiple Sclerosis Scientific Research Foundation and the EDMUS Foundation (‘Fondation EDMUS contre la sclérose en plaques’). In addition, HT has had travel expenses or registration fees prepaid or reimbursed to present at CME conferences or attend meetings (e.g., as a member of the International Advisory Committee on Clinical Trials in Multiple Sclerosis) from the Consortium of MS Centres (2023), the Canadian Neurological Sciences Federation (2023), National MS Society (2022–2025), ECTRIMS/ ACTRIMS (2017–2025), MS Canada (2023, 2025) and the American Academy of Neurology (2019). Speaker honoraria are either declined or donated to an MS charity or to an unrestricted grant for use by HT’s research group.

-

E.A. Yeh (EAY) has received research funding from MS Canada, National MS Society, MS Alliance, OMS Life, Garry Hurvitz Foundation, SickKids Foundation, Peterson Foundation, Canada’s Drug Agency, Stem Cell Network, NIH and the Leong Center. Payment or honoraria for lectures, presentations, etc.: CMSC, AAN, PRIME and Medscape. Support for attending meetings and/or travel: AAN, CMSC, ECTRIMS, ACTRIMS, IMSVisual, MSARD/Elsevier, University of Chile (Santiago), SOPNIA congress, OMSLife foundation, University of Ottawa, New Brunswick Neurological Society, Johns Hopkins University, Michael Smith Foundation and Stem Cell Network. Participation in clinical trials: Roche, Alexion and Horizon Therapeutics. Participation on a Data Safety Monitoring Board or Advisory Board: Pipeline Therapeutics, Roche and IQVIA. Leadership or fiduciary role in other boards, societies, committees, etc.: IMS Visual, RareKids CAN, Cantrain, MS Canada, NMSS and MSARD.

Ethical standard

Ethical approval was not required for this project as there was no patient information collected as part of the survey.

Consent to participate

Consent to participate was inferred based on the physician’s willingness to respond to the survey. No patient information was collected as part of the survey.

Data availability

The data supporting this study have not been shared in a repository. Given the small number of respondents from some jurisdictions, sharing the data could reveal the identity of a specific respondent. Data can be requested and accessed from the corresponding author.