Introduction

Sludge is an emerging concept in behavioural economics that refers to various types of perceived frictions faced by decision-makers due to the specific characteristics of choice contexts. According to key thinkers in behavioural science, Richard Thaler and Cass Sunstein, these frictions and the costs related to them prevent people from making good decisions, so sludge needs to be reduced or eliminated (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2019; Thaler, Reference Thaler2018). Sludge is usually associated with mandatory actions that must be performed because they are institutionally prescribed (e.g., annoying administrative procedures and confusing forms to fill out) or are required by the design of choice options (e.g., user-unfriendly online interfaces and shrouded product attributes). Sludge exists in both the public and private sectors. Sludge is everywhere people choose, make decisions, and interact (see typology of sludge in Table A1 in the online Appendix).

Behavioural scientists have found that sludge has much in common with transaction costs, which are often considered the economic analogue of physical friction (Williamson, Reference Williamson1985). Sina Shahab and Leonhard Lades (Reference Shahab and Lades2024) were the first to shed light on studying sludge through insights from institutional economics: they interpret sludge as a source of subjective transaction costs and provide transaction cost–inspired recommendations for sludge audits. At the same time, such a transaction cost approach to sludge is based on atomistic individualism, which leads to the neglect of many important non-individual factors in decision-making and choice. This limitation also applies to behavioural economics and behavioural science in general, which focus predominantly on individual reasoning and decision-making. Moreover, sludge researchers use a classical paradigm of cognitive science (internalism), which places decision-making exclusively inside the brain and ignores the role of institutions in cognition.

Recently, several behavioural pioneers have come up with the path-breaking idea to frame behavioural research not in individualistic (i-frame) but in systemic (s-frame) terms (Chater and Loewenstein, Reference Chater and Loewenstein2023; Connolly et al., Reference Connolly, Loewenstein and Chater2025). The shift to the s-frame would allow a change in focus from individual-level to system-level causes of behavioural problems, including ‘the flawed laws and institutions that are, in fact, largely responsible for almost all the problems that i-frame interventions seek to address’ (Connolly et al., Reference Connolly, Loewenstein and Chater2025: 594). Although the vast majority of behavioural economists do not consider behavioural economics beyond the i-frame, the s-frame perspective is gaining popularity. An s-frame revolution is urgently needed in sludge research as well.

The overall dominant individualistic and internalistic strand of sludge research I call the ‘i-sludge approach’. Shahab and Lades have significantly advanced the i-sludge approach by adapting classical ideas of the transaction cost theory. But modern institutional economics has powerful potential to help sludge researchers move from the i-frame to the s-frame. The key idea of the s-frame for sludge research is that sludge is not only subjective but also social. I propose the ‘s-sludge approach’ based on understanding sludge as a product of entire rule systems, rather than specific burdensome procedures. The s-sludge approach views decision-making as a socially extended cognitive process (interwoven with cognitive institutions) rather than an outcome of the single individual mind. The s-sludge approach takes into account not only sludge-related transaction costs but also transaction benefits and their uneven distribution among heterogeneous actors of rule systems. The s-sludge approach rejects the idea of passive agency (individuals as ‘victims of sludge’) and interprets decision-makers as resourceful users of external cognitive resources and co-producers of cognitive norms for sludge perception. Although in contemporary i-sludge literature the focus is on individuals, not systems, the s-sludge approach proposes to analyse sludge by combining individual-level and system-level perspectives.

Institutional economists should also examine the concept of sludge more closely. First, sludge provides a broad empirical domain for exploring subjective transaction costs, which remain understudied in transaction cost theory. Second, sludge analysis highlights the cognitive mechanisms underlying decision-making and choice, aligning with the growing interest in cognitive institutions and extended cognition within institutional economics. Third, emotions remain neglected in institutional analysis, but in sludge research, emotional (psychological) costs are recognised as a significant component of subjective transaction costs. Thus, sludge analysis represents a promising field for institutional economics and could give a new lease of life to transaction cost theory, whose development has clearly stagnated.

This paper discusses how to reorient sludge research toward the s-frame. The section ‘From individualistic to systemic view of sludge: introducing the s-sludge approach’ argues for broadening the notion of sludge to include both subjective and social aspects. The section ‘Sludge and transaction costs’ discusses how sludge relates to subjective transaction costs and provides an extended typology of them. The section ‘Sludge and transaction benefits’ emphasises the value-adding side of sludge and explores the interplay between sludge-related transaction costs and benefits. Finally, the section ‘Sludge and cognitive institutions’ presents a shift to a socially extended cognition approach to sludge, focusing on the role of social cognitive systems and cognitive institutions in decision-making.

From individualistic to systemic view of sludge: introducing the s-sludge approach

Behavioural economists deal with immediate choice contexts, so-called ‘choice architectures’, which provide the set of choice options available to the individual at the moment of choice. Examples of choice architectures are the display of goods in a shop window, the terms of a contract, a website’s design, and so on. The type of intervention favoured by behavioural economists is nudges: subtle changes in choice architectures that can improve decision-making without restricting the choice set. Like most behavioural economists, sludge researchers focus on choice architectures and interpret them as the main source of sludge. This is the cornerstone of the i-sludge approach, because sludge is ‘any aspect of choice architecture consisting of friction that makes it harder for people to obtain an outcome that will make them better off (by their own lights)’ (Thaler and Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2021: 153). Since choice architecture refers to minor contextual factors of decision-making, sludge is reduced to small frictions, slight hassles, and minor burdens (see, for example, Bearson and Sunstein, Reference Bearson and Sunstein2025; Grieder et al., Reference Grieder, Kistler and Schmitz2025). Of course, ‘small burdens can be a big deal’ (Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Herd and Harvey2014: 47), but they are not enough for a holistic understanding of sludge. At the core of many behavioural problems lies a causal structure that goes beyond the narrow confines of the choice architecture (Meder et al., Reference Meder, Fleischhut and Osman2018). The individualistic i-frame behavioural economics too often obscures the systemic causes of decision-making problems by shifting the blame to ‘predictably irrational’ individuals (Mills and Whittle, Reference Mills and Whittle2025). Behavioural interventions are traditionally associated with technocratic tweaks (Hansen, Reference Hansen2018; Sanders et al., Reference Sanders, Snijders and Hallsworth2018) like nudges, that is, small changes in non-economic incentives, and do not imply legal restrictions or direct economic stimulus. However, a lot of behavioural problems cannot be solved at the individual level but require the elimination of deficiencies and failures in institutions and infrastructures.

The idea arose to adapt a systemic, s-frame perspective for behavioural research (Chater and Loewenstein, Reference Chater and Loewenstein2023; Connolly et al., Reference Connolly, Loewenstein and Chater2025), shifting attention from choice architecture to the broader systemic conditions of decision-making: we can call them ‘choice environment’.Footnote 1 Real-world choice environments encompass both deliberatively designed and spontaneously evolved elements, including a wide range of institutions and infrastructures (Whitman, Reference Whitman2022). Choice environments significantly influence individuals’ decisions, but changing them is much more difficult than designing choice architectures. If a choice architecture offers individuals a choice between alternative options within given individuals’ choice sets, then the choice environment is associated with a change in the choice sets (see also Shreedhar et al., Reference Shreedhar, Moran and Mills2024). Thus, we can define sludge as the friction-generating features of the choice environment that lead to subjective costs (and benefits).

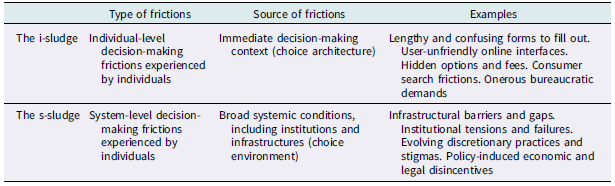

Almost all sludge researchers rely on the i-frame, but some of them explicitly or implicitly acknowledge that analysing sludge solely at the individual level is too narrow. Subjectively experienced minor frictions often manifest significant institutional tensions. Well-designed behavioural interventions, like nudges, most often struggle to overcome infrastructural and institutional barriers (Schmidt, Reference Schmidt2024). Sludge occurs not only within narrow and static choice architectures (I will call it the ‘i-sludge’) but much more often within broad and evolving choice environments (the ‘s-sludge’). The s-sludge covers frictions in decision-making triggered by factors beyond choice architecture (see Table 1).Footnote 2

Table 1. A brief comparison of the i-sludge and the s-sludge

The i-sludge approach (like any approach) has its advantages and disadvantages. The main advantage is its conceptual simplicity, which makes it easy to explain this approach to practitioners. Sludge audits based on the i-sludge approach do not require significant efforts and resources; they allow fixing bugs and improving minor imperfections that hinder good decision-making. The disadvantages of the i-sludge approach follow from its advantages. This is a distinctly applied, practitioner-centric approach: it is adapted to the knowledge and skills of typical choice architects, such as street-level bureaucrats and middle managers. Of course, these practitioners need rather simple solutions to pressing problems, and the i-sludge approach provides them with such solutions. But these solutions often do not eliminate the underlying causes of sludge. In this sense, sludge audits are similar to cosmetic repairs. However, if a wall in an apartment has cracked, then there is no point in covering it with new wallpaper: we need major repairs.

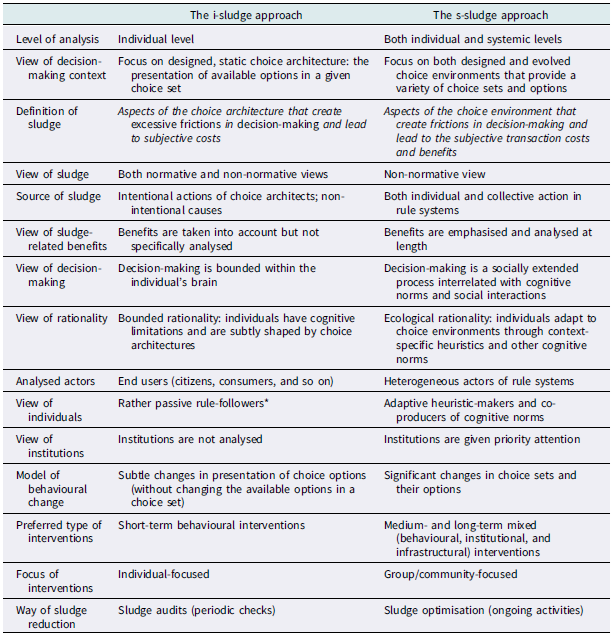

The differences between the i-sludge and s-sludge approaches are significant (see Table 2). The main idea of the s-sludge approach is that we should not understand sludge as narrower than it actually is. We can draw an analogy with transaction costs: these costs at the micro- and macro-level are qualitatively different but are designated by the same term. Sludge at the individual and systemic levels is still sludge. Sludge covers not only minor inefficiencies but also system failures, not only unnecessary paperwork but also institutional pathologies.

Table 2. Focuses of the i-sludge and the s-sludge approaches

Note: *In the i-sludge approach, individuals cannot influence rules (institutions) and merely follow the actions prescribed by them.

Let’s start with a definition of sludge. The i-sludge approach defines sludge as aspects of choice architecture that generate excessive frictions for decision-makers (Shahab and Lades, Reference Shahab and Lades2024; Thaler and Sunstein, Reference Thaler and Sunstein2021).Footnote 3 The s-sludge approach offers a broader and non-normative definition: sludge is any aspect of an evolving choice environment that creates decision-making frictions and related transaction costs and benefits. First, we are talking not only about immediate choice architectures but also about broad, real-world choice environments. Second, sludge is associated with frictions for decision-makers, but these frictions are not always excessive (they can be justified) and not necessarily harmful (they can be beneficial). Some i-sludge researchers also understand this. Next, the i-sludge approach looks at sludge through the eyes of an individual decision-maker: ‘Observing that a person experiences costs that are due to the choice architecture the person navigates in is enough for us to claim that we have identified sludge’ (Shahab and Lades, Reference Shahab and Lades2024: 337). The choice architecture concept takes the wider system as given (Connolly et al., Reference Connolly, Loewenstein and Chater2025). On the contrary, the s-sludge approach views sludge as a product of rule systems: sludge results from institutions, social interactions, power, and inequality. Rule systems can be of different scales; they cover a broad spectrum of institutions, so sludge reduction can occur through changes in both societal institutions (e.g., consumer protection regulations and plain language laws) and micro-institutions (e.g., heuristic rules, cost perception frames, social norms, and so on). The s-sludge approach does not ignore individuals; instead, it emphasises the role of active individual agency. However, sludge is not only a problem of individual perceptions of frictions but also a collective action problem.

The i-sludge approach focuses only on frictions in immediate choice architecture, which are subjectively perceived by decision-makers. Therefore, objective causes of sludge are ignored. However, sludge arising at the systemic level includes objective causes of decision-making frictions, e.g., institutional failures, charges and commissions, or infrastructural barriers. Of course, these causes of sludge are perceived subjectively. This is important because sludge in behavioural science is associated specifically with the subjective experience of costs. But the s-sludge approach also takes into account objective causes and sources of sludge (see Figure 1).

Figure 1. The subject area of the s-sludge approach.

For the i-sludge approach, institutions are of no scientific interest: ‘The i-frame takes the rules and institutions within which people operate as fixed’ (Connolly et al., Reference Connolly, Loewenstein and Chater2025: 595). If institutions are the ‘rules of the game’ (North, Reference North1990), then choice architecture is the ‘design of the game’ (Shahab and Lades, Reference Shahab and Lades2024) on which the i-sludge approach is focused. There is no doubt that the design of the game matters, since ‘some designs can make it harder to follow the rules than other designs’ (ibid.: 331). However, for the s-sludge approach, both the design of the game and the rules of the game matter. Consider football (soccer) as an example. In this case, the design of the game is the work of the referee (interpreting game situations in terms of compliance with the rules; verbal warnings; awarding yellow or red cards, etc.). The referee acts as a kind of choice architect: he controls the flow of the game and compliance with the rules of the game and maintains order and discipline. The referee can judge the game very strictly and enforce every minor infraction, or he can give the players more freedom of action – these are different designs of the game. But many behavioural problems in football require changes to the rules of the game. For example, players’ constant simulating of injuries led to them being punished with yellow and even red cards since 1999. Frequent errors by referees in interpreting complex game situations led to the implementation of Video Assistant Referee (VAR) technology in 2018. Regular delays in the game by goalkeepers led to a new rule in 2025: having caught the ball in his hands, the goalkeeper has only 8 seconds to put the ball into play; otherwise, a corner kick is awarded. Such systemic behavioural problems cannot be solved by a choice architect (referee), no matter how often the referee blows his whistle.

Sludge and transaction costs

Shahab and Lades (Reference Shahab and Lades2024) have created the most advanced version of the i-sludge approach, enriching it with ideas from institutional economics. The problem is that i-sludge researchers use transaction cost theory only to study individual perceptions of sludge. However, both transaction cost theory and, more broadly, institutional economics have much greater potential: they were created to analyse complex, evolving institutional systems full of heterogeneous actors. We could harness the potential of institutional economics to a much greater extent and take sludge research beyond the i-frame.

Leading i-sludge researchers highlight the importance of the subjective experience of transaction costs (Shahab and Lades, Reference Shahab and Lades2024). It must be admitted that institutional economists have paid insufficient attention to this issue. Nevertheless, subjective transaction costs could well be part of the transaction cost theory. The founder of transaction cost analysis, Ronald Coase, in a series of articles published in 1938, emphasised the subjective nature of any costs (Coase, Reference Coase, Buchanan and Thirlby1981). Oliver Williamson’s proposed research agenda for transaction cost economics initially included opportunities for developing the Austrian view of transaction costs (this was explicitly, although briefly, pointed out in Williamson, Reference Williamson1985: 46–47).Footnote 4 Austrian economics assumes subjective interpretations of costs by decision-makers at the moment of choice. As the Austrians point out, ‘costs are inherently subjective and not subject to objective measurement’ (Pasour, Reference Pasour1978: 327). In other words, ‘[c]ost cannot be measured by someone other than the chooser since there is no way that subjective mental experience can be directly observed’ (Buchanan, Reference Buchanan, Buchanan and Thirlby1981: 15). Many transaction-cost researchers have relied on the implicit understanding of transaction costs as subjective costs (see review in McMackin et al., Reference McMackin, Chiles and Lam2022). Despite this, the subjectivist strand of transaction cost theory has not been deeply developed, so when institutional economists talk about transaction costs, they most often mean ‘objective transaction costs when assessed ex post by an outside observer’ (Chiles and McMackin, Reference Chiles and McMackin1996: 78). The sludge concept is a good reason to return transaction cost theory to a subjectivist path where subjective perceptions of costs are central to analysis (see also Buckley and Chapman, Reference Buckley and Chapman1997).Footnote 5

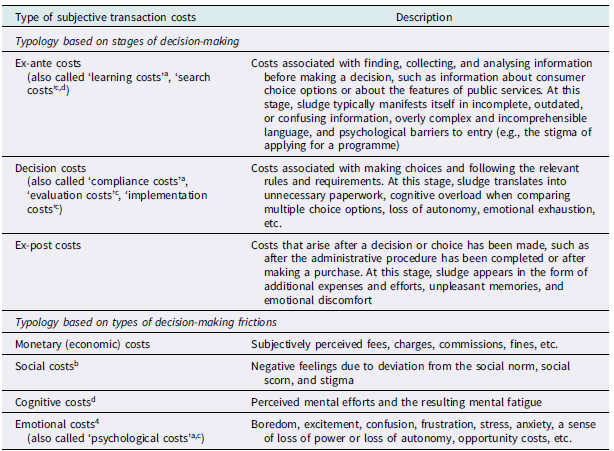

Coase supported Carl Dahlman’s typology of transaction costs (Coase, Reference Coase1988: 6). According to Dahlman (Reference Dahlman1979: 148), transaction costs include ‘search and information costs, bargaining and decision costs, and policing and enforcement costs’. This typology fits perfectly with the individualistic i-sludge approach. Shahab and Lades (Reference Shahab and Lades2024) use Dahlman’s typology as a basis for classifying sludge-related transaction costs and add psychological costs to them. This may sound unusual to institutional economists, but psychological costs are transaction costs in the form of emotional efforts to perform prescribed actions and procedures. The emotional experience of decision-making frictions is a blind spot in transaction cost theory, and this should be recognised as a significant omission. For example, bureaucratic red tape is closely intertwined with numerous negative emotions, from confusion to anger, which have a strong influence on how citizens perceive and follow bureaucratic rules. In the private sector, a variety of ‘confusopolies’, marketing obfuscations, and dark patterns also increase the emotional burden on consumers when making transactions. Psychological transaction costs need serious exploration.

While productively expanding the notion of subjective transaction costs to include psychological costs, the i-sludge approach simultaneously narrows this notion by excluding monetary incentives or disincentives (e.g., taxes and fines) and legal restrictions (e.g., bans and mandates) from the definition of sludge (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2022). The reason is that behavioural public policy based on the i-frame does not deal with economic and legal (dis)incentives; it only affects the psychological factors of decision-making, and its tools are small changes in immediate choice architectures. Therefore, from the i-sludge viewpoint, broking fees/commissions, legal fees, and administrative charges are irrelevant to sludge, since they are not directly linked to choice architecture (Shahab and Lades, Reference Shahab and Lades2024). However, they are linked to the broad choice environment, which is in the spotlight of s-sludge researchers. From the s-sludge viewpoint, fees, charges, and commissions are sludge-related transaction costs. These monetary transaction costs can be subjectively perceived in different ways: as reasonable, excessive, offensive, etc. Despite the fact that the sources of these costs are far beyond the individual’s choice architecture, these costs are important for decision-making, and they matter precisely as subjectively experienced transaction costs.

The s-sludge approach considers sludge in relation to economic and legal (dis)incentives.Footnote 6 For example, in cases of starting up a new business or registering property, monetary transaction costs are an integral part of the required procedures, and, therefore, these perceived costs should be classified as sludge. Obtaining a visa is an example of sludge (often used by Sunstein), where a complex, oppressive procedure is organically combined with (subjectively experienced) monetary costs and fees. The s-framed behavioural public policy could combine behavioural interventions with both economic and legal ones. For example, norm nudges (that steer individuals toward good decisions by appealing to social norms) may require changes in economic and legal incentives for a new social norm to become widely adopted.

Consider an extended typology of sludge-related transaction costs that could be used by s-sludge researchers (see Table 3). My typology combines Shahab-Lades’s view with approaches by other i-sludge researchers (Mills, Reference Mills2023; OECD, 2024) and earlier similar ideas from administrative burden theory (Moynihan et al., Reference Moynihan, Herd and Harvey2014). I propose to take into account the experienced monetary transaction costs of decision-making and ex-post transaction costs that arise after a decision is made (additional efforts and costs, as well as psychological ‘aftertaste’). This typology emphasises that different types of subjective transaction costs may arise at each stage of decision-making: monetary (economic), social, cognitive, and emotional (psychological) costs.

Table 3. Typology of subjective transaction costs in the s-sludge approach

Source: aMoynihan et al. (Reference Moynihan, Herd and Harvey2014); bMills (Reference Mills2023); cShahab and Lades (Reference Shahab and Lades2024); dOECD (2024).

Transaction costs have been associated with negative frictions from the very beginning. George Stigler was the first to liken the imaginary physical world of zero friction to an economy with zero transaction costs (Stigler, Reference Stigler1972). In turn, Oliver Williamson (Reference Williamson1985: 2) defined transaction costs as the ‘economic counterpart of friction’ and inscribed the metaphor of friction on the banner of new institutional economics. The main criticism against mainstream economists concerned the unrealistic assumption of frictionless markets (Williamson, Reference Williamson1975). Williamson (Reference Williamson1996: 92) later made the reservation that he avoided comparing real institutions and forms of organisation with frictionless ideals. Nevertheless, it was precisely frictionless (or low-cost) institutions that implicitly came to be regarded as the ideal. This is unsurprising: new institutional economics views economic institutions through the lens of transaction-cost economisation, as the main purpose of institutions is to reduce transaction costs (Williamson, Reference Williamson1985).

Like transaction costs in institutional economics, sludge in the i-sludge approach is most often interpreted as excessive, harmful frictions: ‘It is helpful to reserve the term ‘sludge’ for impositions that have a negative valence’ (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2022: 660). Therefore, sludge-related costs are most often considered as wasted expenditure, ‘just like transaction costs are the costs that make a transaction happen but do not create value’ (Shahab and Lades, Reference Shahab and Lades2024: 335). The ideal is ‘a sludge-free government or company’ (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2022: 670). Of course, i-sludge researchers acknowledge that decision-making frictions can be justified by related benefits, so the optimal level of sludge ‘is not zero. Some sludge is good or even essential’ (Sunstein and Gosset, Reference Sunstein and Gosset2020: 75). Shahab and Lades emphasise that ‘determining whether sludge is welfare-reducing (i.e., unjustified and excessive) or welfare-enhancing requires a broader cost–benefit analysis that also integrates benefits to all involved parties’ (Shahab and Lades, Reference Shahab and Lades2024: 337).

The word ‘benefits’ is very important here. Transaction cost economics provides a distinctly one-sided view of institutions (rule systems) in terms of cost minimisation; as a consequence, this view often ‘neglects the benefits which are the primary reason for making a transaction’ (Cartier, Reference Cartier1994: 194). As Dahlman emphasised, ‘transaction costs are productive in precisely the same way that resources used up in the physical transformation of inputs into outputs are productive’ (Dahlman, Reference Dahlman1979: 145). Excessive reduction of transformation (production) costs will inevitably lead to a decrease in the quality of the product; if transformation costs are reduced to zero, the product will simply not be produced. Similarly, any transactions and social interactions are costly in terms of resources, effort, and time. Rule systems (that facilitate transactions and interactions) are costly too: e.g., the functioning of markets or governance structures requires transaction costs. Some of these costs may be considered excessive and should be reduced. However, a significant part of transaction costs is the payment for the transaction benefits that are created in transactions governed by a particular rule system. In other words, transaction costs produce corollary benefits (Wallis and North, Reference Wallis and North1988). Transaction costs are objectively necessary for rule systems to perform their useful functions, and ‘[r]educing transaction costs carries risks of reducing the benefits that these costs purchase’ (Driesen and Ghosh, Reference Driesen and Ghosh2005: 64). Therefore, by combating excessive, unnecessary, and unjustified sludge-related transaction costs, we can easily reduce transaction benefits that are delivered to decision-makers when they perform prescribed actions and procedures.Footnote 7

Sludge and transaction benefits

Arguments for the need to introduce transaction benefits into institutional analysis can be found in legal research (Driesen and Ghosh, Reference Driesen and Ghosh2005; Komesar, Reference Komesar1994, Reference Komesar2014; Markovits, Reference Markovits2021; Trachtman, Reference Trachtman1997), management science (Blomqvist et al., Reference Blomqvist, Kyläheiko and Virolainen2002; Zajac and Olsen, Reference Zajac and Olsen1993), and international studies (Paul and Vandeninden, Reference Paul and Vandeninden2012; Sandler and Cauley, Reference Sandler and Cauley1977; Sandler, Reference Sandler2001). Many institutional economists have argued against the static and cost-focusing approach of transaction cost economics (Eggertsson, Reference Eggertsson2005; Greif and Kingston, Reference Greif, Kingston, Schofield and Caballero2011; Hodgson, Reference Hodgson2004, Reference Hodgson, Klein and Sykuta2010). If we consider institutions as evolving objects, then transaction cost-economising is not the only and universal way of explanation (Langlois and Foss, Reference Langlois and Foss1999), and the benefit side of rule systems should be taken into account as a matter of priority (Dietrich, Reference Dietrich2008). But all ‘protest’ voices were drowned out by the chorus of transaction cost researchers: in the overwhelming majority of works, a huge variety of transaction benefits is reduced to transaction-cost-minimising benefits.

Similarly, the i-sludge literature typically focuses on the benefits of sludge reduction (Hortal and Pérez Martínez, Reference Hortal and Pérez Martínez2024; Mills, Reference Mills2023; Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2022) and ignores all other transaction benefits. For example, the OECD report ‘Fixing frictions: ‘sludge audits’ around the world’ (OECD, 2024) contains over 90 mentions of the word ‘frictions’, almost 80 mentions of the words ‘cost/costs’ and only 13 mentions of the word ‘benefits’, mostly referring to the benefits of sludge audits, while the benefits of administrative procedures are not mentioned at all. This is all you need to know about understanding the importance of transaction benefits in the i-sludge approach.Footnote 8 If i-sludge researchers observe that an individual experiences decision-making frictions and related costs, and that these frictions and costs are due to choice architecture, then they identify sludge, ‘independent of whether the sludge also leads to benefits’ (Shahab and Lades, Reference Shahab and Lades2024: 337). Certainly, leading i-sludge researchers understand that ‘sludge also leads to benefits for the individual, for the choice architect, or for society’ (ibid.: 336), so, for instance, ‘[t]he benefits of paperwork burdens must justify their costs’ (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2021: 19). Nevertheless, the overwhelming focus of the i-sludge approach is on sludge-related costs. Even the definition of sludge is cost-focused: sludge is defined as ‘aspects of the choice architecture that lead to the experience of costs’ (Shahab and Lades, Reference Shahab and Lades2024: 329). But why only costs and not benefits? After all, when interacting with any environment, people experience both costs and benefits. It could be said that in choice environments with high levels of sludge, most people feel more costs than benefits. And yet, we should not ignore the benefits if we really want to understand sludge.

It is undeniable that many transaction benefits are associated with reductions in transaction costs. Many, but not all. Transaction benefits can also result from the fact that certain types of transaction costs replace other types, or that some transaction costs substitute production costs (Langlois, Reference Langlois2006). Many transaction benefits are not related to the reduction or reconfiguration of transaction costs but to the improvement of the quality of transactions and social interactions. For example, the firm not only allows some economic activities to be carried out with lower transaction costs than the market, but, in addition, ‘the firm can provide an organisational environment, consisting of routines, images, artefacts and information, which can enhance the capabilities of workers’ (Hodgson and Knudsen, Reference Hodgson and Knudsen2007: 337). In other words, the firm creates transaction benefits (value-adding features of the organisational environment), and these are not benefits related to transaction cost economising. These are transaction benefits that improve the quality of interactions within the firm and, as a result, improve its business processes (decision-making, innovation creation, employee training, etc.). In turn, the market not only reduces transaction costs but also provides transaction benefits – various affordances and additional cognitive resources – for market participants. The market encompasses both the price system and related third-party institutions (including comparison websites, online product reviews, consumer ratings, consultants, and experts) that help consumers overcome sludge. In particular, comparison websites provide additional cognitive resources for those trying to cope with a confusopoly (see empirical evidence in Earl et al., Reference Earl, Friesen and Shadforth2017).

In transaction cost economics, the dominant view of transaction costs is as impediments to transactions, deadweight losses, or even waste; this leads to a fetishisation of low-cost institutions (e.g., cheaper markets). The i-sludge researchers also adopted the same view. However, a rule system can be more expensive but more productive than its lower-cost counterpart: in this case, the rule system adds more transaction benefits by improving the qualitative features of transactions and social interactions. Generally, the quality of regulations (i.e., transaction value added) is more important than the simplification of administrative formalities, i.e., economising on transaction costs (see also OECD, 2013). Simplifying many administrative procedures and reducing sludge can lead to a reduction in the transaction benefits received by individuals. Transaction benefits should justify transaction costs, and, in particular, ‘the benefits of regulations are generally required to justify their costs’ (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2019: 1846). For example, although such forms of dispute resolution as settlement and arbitration ‘involve lower transaction costs than adjudication, they also fail to generate adjudication’s valuable transaction benefits’ (Markovits, Reference Markovits2021: 633), including openness, procedural intensity, impact on legal norm production, etc. Sludge-reducing plain language in official documents is very convenient for citizens, but from the viewpoint of lawyers, it is an oversimplified language, unable to express complex legal ideas and unreasonably prioritising clarity over accuracy (Blasie, Reference Blasie2022); in this case, the reduction in transaction costs led to a reduction in the transaction benefits provided by the legal system. Simple and low-cost procedures do not always benefit people in the long term. Thus, we should analyse rule systems and their elements (e.g., prescribed procedures) with an emphasis on the interplay between transaction benefits and transaction costs.

In addition, we should take into account psychological transaction benefits, such as satisfying curiosity, obtaining positive emotions and valuable experiences, and increasing the perceived meaningfulness of actions. Reducing many types of decision-making frictions (and subjective transaction costs) leads to a reduction in related psychological benefits. Entrepreneurs usually strive to offer consumers frictionless customer experiences and seamless transactions, believing that people do not want to face frictions in the market. However, a human is not an infantile creature who wants to avoid exerting effort and get everything they want ready-made. A human is an active being who wants to overcome (meaningful) obstacles and thereby develop themselves. People want to follow the intricate plot of a detective story and not immediately find out who the killer is. People want to watch a tense match and root for their favourite team, and not just find out the final score. People want to learn how to fry a delicious steak themselves and not just order it in a restaurant. Using a language learning app, people want to really improve their language skills and not just get rewards for completing easy tasks. There are a huge number of such examples. Overcoming many frictions provides people with psychological transaction benefits. In many cases, customer effort, deliberation, participation, and co-creation enable people to achieve ‘benefits of having friction as a part of the customer experience’ (Padigar et al., Reference Padigar, Li and Manjunath2025: 24).

The idea of transaction benefits should not be taken too simply. It is not enough to acknowledge that administrative procedures and processes are functional and produce benefits for their participants. This is an obvious fact accepted by behavioural scientists who share Sunstein’s position on the optimal level of sludge (Sunstein and Gosset, Reference Sunstein and Gosset2020). Incorporating transaction benefits into the picture of sludge, we must recognise that sludge is a difficult (im)balance between subjective transaction costs and benefits. This leads to two conclusions that expand the cost-focused view of sludge. First, decision-makers may not understand their benefits, which are created at the systemic level, that is, at the level of the rule system as a whole. Second, transaction benefits are not created exclusively for decision-makers (rule-system users), and decision-makers may not understand the benefits received by other actors involved in the rule system’s functioning. In these problematic cases, decision-makers may perceive choice environments as more sludgy (in the negative sense of the term) than they actually are.

Sludge emerges in fairly complex, polycentric rule systems with heterogeneous actors. These actors have different roles, interests, beliefs, and expectations, so they all perceive various kinds of sludge differently. What is a high level of sludge for immigrants can be interpreted by officials as part of the government’s fight against illegal immigration. High licensing requirements may be welcomed by existing market entrants but viewed as sludge by new entrants (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2022). The digitalisation of tax services reduces transaction costs for digitally advanced taxpayers but creates additional frictions for marginalised groups (Lawton and Massey, Reference Lawton and Massey2024). Rigorous product quality control procedures, for example, official crash testing programmes, are a burden (sludge) for manufacturers but a protection for consumers. Moreover, if these procedures were not in place, consumers would still need to have their cars inspected for safety, which could result in greater costs (and frictions) than they would save on cheaper, red-tape-free cars. What for scientists is a complicated set of requirements and barriers, for scientific foundations’ officials is an effective system for selecting high-quality grant applications. A scientist applying for a grant for the first time perceives the procedure as containing many cumbersome and unnecessary frictions, whereas an experienced grant recipient perceives the level of sludge as much lower because he/she has accumulated knowledge and competencies in repeatedly going through this procedure. Since bureaucratic red tape is most often cited as an example of sludge, it is interesting that the famous red tape researcher Herbert Kaufman emphasised that ‘one person’s red tape is another’s sacred protection’ (Kaufman, Reference Kaufman1977: 50). Moreover, public employees also deal with sludge and experience cognitive-affective strain (Stenderup, Reference Stenderup2024). In turn, dark patterns for consumers are sludge-increasing deception, while for managers and shareholders, they represent clever, value-adding, and low-cost business practices (Sin et al., Reference Sin, Harris, Nilsson and Beck2025).

Sludge, like transaction costs, is a product of entire rule systems, not of isolated procedures or processes. The distinction between the individual and systemic levels of sludge analysis is important. What appears as bad sludge at the individual level (e.g., when an individual performs a certain prescribed procedure) may well be necessary and value-adding at the systemic level, where all procedures are linked into a whole rule system. Rule systems are multifunctional systems, so many functions, tasks, activities, and related procedures may be incomprehensible to individuals and may be perceived by them as sludge. For instance, paperwork burdens are often justified by such system-level transaction benefits as ensuring programme integrity, privacy, data collection, and so on (Sunstein, Reference Sunstein2019), which can only be viewed from a systemic lens. Here is an example: filling out an additional form (perceived by the individual as redundant paperwork) may be aimed at obtaining additional information about citizens by the state to improve the quality of this or other public services. In the case of grant applications, sludge plays a kind of de-marketing role at the systemic level: it deters many potential applicants (since they have to fill out complex forms) and reduces the cognitive overload of assessors, allowing them to perform their job more efficiently. Consider peer review in academic journals: what appears as delays in publication and petty criticism at the individual (author) level, at the systemic (journal’s community) level, ensures high-quality articles and journal prestige.Footnote 9 Patients in public hospitals may perceive long lines and waiting times for doctors as uncomfortable frictions (sludge). Still, these frictions are a consequence of the way the hospital operates as a system. Doctors wear many hats: they not only diagnose and treat diseases but also engage in scientific and educational work, participate in consultations, maintain medical records, perform administrative duties, and so on; they may also be called upon to see urgent patients or perform surgery. In turn, time ‘wasted’ in meetings (from the perspective of the organisation’s employees) leads to the development of organisational routines for collective decision-making. Complex but effective organisational rules (e.g., safety management systems) are often perceived as overregulation due to accountability and audit demands. In other words, ‘[s]ludge may be sludge for the common good even if it frustrates individuals’ (Madsen et al., Reference Madsen, Mikkelsen and Moynihan2022: 380). So, sludge may not be a bug but a feature of rule systems. This does not mean that all rule systems are perfect and have no shortcomings. Nor does it mean that subjective perceptions of rule systems are unimportant. I merely argue that a straightforward identification of sludge with excessive, harmful frictions is far from always correct. Transaction benefits matter.

Moreover, rule systems are complex systems of interrelated formal and informal rules, procedures, and practices. Therefore, fixing frictions (the title of the first OECD report on sludge) may not be as simple as it seems. Rule systems are very often based on several governing logics (or institutional logics) that operate simultaneously. Institutional logics are frameworks of fundamental values, shared visions, and guiding principles that unite different groups of actors within a rule system. These logics can conflict and generate ongoing tensions that manifest as sludge. For instance, healthcare organisations are a well-studied case of conflicting institutional logics that create multiple coexisting norms and multiple misalignments between norms, values, and shared meanings (see review in Vivier et al., Reference Vivier, Robinson, Jenkins and Smit2024). Much of the decision-making friction and its sources are informal and are not the focus of i-sludge researchers. Informal sources of sludge (e.g., conflicts of institutional logics) influence formal sources and vice versa. Reducing sludge in formal procedures and processes can be offset by an increase in sludge during informal interactions and practices. We should see a more complex picture of sludge creation.

The s-sludge approach is opposed to the technocratic (politically neutral) view of sludge. The key question here is who bears the costs and who benefits from the sludge? Sludge driven by vested interests and rent-seeking (often called ‘bad/evil nudges’, see Mills, Reference Mills2023; Thaler, Reference Thaler2018) has repeatedly come to the attention of i-sludge researchers but has been considered exclusively from an individualistic viewpoint. However, what i-sludge researchers deal with – design (of the game) flaws – is only the tip of the ‘frictional iceberg’.Footnote 10 Sludge is an object of negotiations and struggle, and its level is the result of ongoing institutional work by many actors with different interests and powers. Confusing banking forms and unclear language of contracts are a problem not of particular administrative processes or even of individual banks, but of the banking system as a whole, exploiting the limited bargaining power of consumers. The mobile market, with its high power asymmetry, is a classic example of confusopoly: companies use a variety of tricks to obfuscate their consumers and push them towards welfare-reducing decisions (Nicolle et al., Reference Nicolle, Genakos and Kretschmer2023). The inability to refuse to press the ‘I agree’ button is a consequence of the total power of digital monopolies. If the i-sludge approach combats easily identifiable sludge, the most important task of s-sludge researchers is to identify the ‘invisible sludge’ that is widespread in the digital economy and imperceptibly exerts a colossal influence on people’s decisions and choices. Until now, both judges and legislatures ‘lack a systematic understanding of how evil nudges influence internet users, let alone how the law should respond’ (Lavi, Reference Lavi2020: 6); here, evil nudges are a form of sludge. Many imposed decision-making frictions result from market rules established by powerful digital corporations and integrated into technology interfaces. As a result, taxi drivers ‘voluntarily’ become independent contractors and agree to the absence of traditional social guarantees, and also ‘voluntarily’ become objects of constant and intrusive algorithmic management (like other types of gig workers). In turn, Internet users ‘voluntarily’ donate personal data to digital platforms, contributing to their enrichment and power concentration (so-called ‘surveillance capitalism’; see Zuboff, Reference Zuboff2019). What is needed to counteract many types of sludge is not sludge auditors but institutional entrepreneurs.

Sludge and cognitive institutions

The i-sludge approach is based on the classical paradigm of cognitive science that combines atomistic individualism and internalism. From this perspective, decision-making and other cognitive processes are internal: they are located in the individual’s brain. Individuals’ interactions with the external environment are reduced to information processing (the environment is only a source of information); external artefacts, other people, and institutions play a very limited role in cognition.Footnote 11 However, in modern cognitive science, a paradigm shift is gaining momentum: the internalist-individualistic view of cognition is being challenged by a socially extended cognition. This approach fundamentally rethinks the current understanding of cognition by emphasising social interactions and cognitive institutions and could be used by s-sludge researchers.Footnote 12

Cognitive processes of individuals are not only a neural phenomenon, and they are not located only in the brain. Cognitive processes are dynamic mind-environment interactions, including social interactions.Footnote 13 Cognition is interactive by nature and involves active use of environmental resources. Choice environments consist not only of constraints and frictions but primarily of cognitive resources – opportunities, affordances, cues and clues, etc. Decision-makers are not single, isolated individuals; decision-making is not done alone. Decision-makers actively and creatively interact with the environment, including other people. Consider an airport – a sludgy and teeming environment with an enormous number of administrative procedures and required actions.Footnote 14 Imagine a poorly educated Otto about to fly on an airplane for the first time in his life. For Otto, an airport is a completely incomprehensible and frightening environment. However, we can be almost 100% sure that Otto will successfully complete a complex cognitive task and board his flight on time. To do this, Otto will actively interact with the airport environment – he will ask other passengers and airport employees for help, he will read instructions and follow electronic boards, and he will navigate using signs and voice announcements. In other words, Otto is using a lot of external cognitive resources to compensate for his cognitive limitations and lack of flying experience. If we had interviewed Otto as he first entered the airport, he would have described a catastrophically high level of sludge. However, Otto managed to overcome the sludge in a way that real people do every day – using socially extended cognition.

Leaving aside extreme cases like Robinson Crusoe on a desert island or Mowgli raised by wolves, an individual’s cognition always occurs inside social cognitive systems: dynamic networks of minds, cognitive institutions (sets of cognitive norms), cultural practices, artefacts, infrastructures, etc. Any rule system is simultaneously a social cognitive system, ranging from a bank, an airport, and a digital platform to a market, a legal system, and science. Social cognitive systems are strongly based on normativity, and cognitive institutions play a crucial role: without interconnected cognitive norms, it is impossible to coordinate the huge number of elements involved in socially extended cognitive processes (Petracca and Gallagher, Reference Petracca and Gallagher2020). Cognitive norms include socially constructed and accepted beliefs, frames, conventions, narratives, decision-making rules, cultural lenses, social meanings, market categories, and so on (Frolov, Reference Frolov2024; Greif and Mokyr, Reference Greif and Mokyr2017; Menary, Reference Menary2007). Subjective understanding, perception, and engagement with sludge are mediated by cognitive norms that provide affordances for various cognitive processes.

The i-sludge approach relies on bounded rationality theory. Herbert Simon (Reference Simon1990) proposed the scissors metaphor to describe bounded rationality as consisting of two modules: the cognitive and the environmental. Economists typically use a narrow version of this theory – cognitively bounded rationality – ignoring the influence of environmental, external factors on decision-making (Petracca, Reference Petracca2021). For example, in Williamson’s transaction cost economics, ‘[b]ounded rationality refers to the rate and capacity of individuals to receive, store, retrieve, and process information without error’ (Sent and Kroese, Reference Sent and Kroese2022: 185). Behavioural economists (including i-sludge researchers) go further: they also consider the environmental module but use a very static and narrow notion of the environment as an immediate choice architecture. Instead, the s-sludge approach offers an ecological view of rationality. Decisions are only rational relative to choice environments: there are distinct environments that support varied types of ecological rationality. In some environments, it is (ecologically) rational to collect as much information as possible, while in others, it is rational to ignore available information. In some environments, it is (ecologically) rational to use slow, complex, and deliberative reasoning, while in others, it is rational to rely on intuition and simple rules (e.g., fast-and-frugal heuristics; see Gigerenzer, Reference Gigerenzer2021).Footnote 15 Sludge operates differently across different choice environments due to their institutional, technological, social, and cultural characteristics. Moreover, real-world environments are often ill-defined, ambiguous, messy, teeming, and turbulent. Ecological rationality, therefore, involves finding and using cognitive norms that are adapted to specific choice environments: these norms enable individuals’ cognitive processes and make decisions more effective (Frolov, Reference Frolov2023). I emphasise that what is rational is not the passive adherence to an ecologically rational cognitive norm, but the active use of environmental cognitive resources, guided by such a norm.

Let’s get back to our Otto. While still planning his flight, he could have used sludge-reducing cognitive norms – collectively accepted tips and tricks for getting through airport procedures faster: for this, Otto would have only to enter a phrase like ‘airport top tips’ into the search bar. Otto would have discovered that cognitive norms (guides, instructions, checklists, and so on) are very diverse: they can be both simple and quite complex, and they can be designed for both beginners and experienced travellers. The main thing is that cognitive norms enable the use of accumulated social experience of following prescribed procedures, thereby saving cognitive efforts, emotional costs, time, and money. However, if a cognitive norm does not fit a specific environment, then not only does it not reduce sludge, but it can also become a source of sludge.Footnote 16 If Otto were observant, he would have noticed that a very significant proportion of the passengers were coming from different cultural systems. Their cognitive norms often conflict with existing airport norms generally accepted in the Western world. Otto might have noticed constant tensions and conflicts related to religious beliefs, race and ethnic differences, gender stereotypes, and other cultural features. He would have noticed that the equality norms are increasingly challenged and many passengers demand special status and privileges based on their social identities (see also Majlergaard, Reference Majlergaard2024). On the one hand, cultural tensions and conflicts (and related psychological costs) are the result of using inappropriate cognitive norms in Western airport environments. On the other hand, constant cultural clashes and unsatisfied travellers challenge existing cognitive norms, causing incremental institutional changes in airports’ social cognitive systems, so sludge drives the evolution of cognitive norms.

Social cognitive systems arise from social interactions; therefore, individuals play an enactive role by actively exploring, interpreting, using, and co-constructing the choice environments they engage with (Frolov, Reference Frolov2023; Petracca and Gallagher, Reference Petracca and Gallagher2020). Therefore, social cognitive systems are inherently dynamic and do not have static, fixed properties and elements. Decision-makers are bottom-up institutional innovators who constantly reassemble and co-produce social cognitive systems. They try to adapt to sludgy environments by creating practices of reducing frictions and bypassing barriers. When shared between decision-makers, such practices become cognitive norms. On the Internet, we can see numerous heuristic rules, life hacks, tips, instructions, and sample forms related to different administrative procedures and processes. These are the digital traces of cognitive norms’ co-producers; from this institutional ‘raw material’, cognitive institutions arise. When decision-makers cannot influence the sludge reduction, they gradually develop cognitive norms that normalise the current level of sludge. Through the prism of these cognitive norms (e.g., norms of stigmatised language), sludge becomes legitimate, which leads to an increase in the sludge tolerance of decision-makers and reduces their psychological costs. Following such cognitive norms is ecologically rational because then decisions in a sludgy environment will not be perceived as difficult, unpleasant, and costly. Thus, queues in socialist countries constituted a mass phenomenon, yet they were perceived as the norm – acceptable frictions – despite occupying a significant portion of people’s time budgets. A queue at a modern bank or store is perceived as an anomaly, but a queue at the airport is considered the norm. These are examples of different choice environments with different ecologically rational cognitive norms.

In sum, the socially extended cognition paradigm offers sludge researchers a move from an internalist and individual-centred picture of decision-making to a much more realistic view. Sludge should be analysed considering the specificity of the social cognitive systems in which it emerges. Sludge research could focus on ecological rationality mediated by various co-produced cognitive norms. This would add sociality, normativity, and dynamism to the understanding of decision-making. In practice, when conducting sludge analysis, s-sludge researchers need to get answers to a number of research questions. How does decision-making occur in terms of ecological rationality? What context-specific norms of rationality are supported by the social cognitive system? What heuristic rules do decision-makers use to adapt to frictions and overcome barriers? What are the cognitive norms of transaction costs and benefits perception? What are the cognitive norms that legitimise sludge and increase the sludge tolerance of decision-makers? What are the cognitive norms that delegitimise sludge and reduce sludge tolerance? What institutional and infrastructural barriers influence decision-making, and how are they enabled? Answers to these questions will allow us to understand how sludge arises in social interactions and how it is entangled with cognitive institutions. We should also take into account the heterogeneity of environments (each choice environment has its own cognitive norms for decision-making), the heterogeneity of actors (different actors perceive sludge differently and have varying interests in relation to sludge), and the heterogeneity of the sludge itself and its sources. There is a need to develop far more sophisticated and nuanced methods for measuring sludge than those currently available.

Conclusion

The sludge concept was proposed by then-newly-minted Nobel laureate Richard Thaler (Reference Thaler2018) to describe subjectively perceived decision-making frictions. Behavioural scientists have attempted to apply classical ideas from transaction cost economics to sludge analysis. However, sludge research could be significantly improved by adopting more advanced ideas from modern institutional economics.

Sludge is a complex phenomenon that requires analysis at both the individual and systemic levels. But behavioural economics is dominated by the i-frame: an individualistic and internalist view of decision-making. The strand of sludge research based on the i-frame (i-sludge approach) considers sludge in terms of transaction costs perceived by individual decision-makers. The i-sludge researchers focus on a rather narrow choice architecture (‘design of the game’), abstracting from the role of institutions (‘rules of the game’) and the social aspects of decision-making. Since behavioural science is debating the idea of moving from the individualistic i-frame to the systemic s-frame, I propose a research agenda for the systemic s-sludge approach.

In the i-sludge approach, sludge is defined as excessive frictions in decision-making and related subjective transaction costs. However, any rules, procedures, and entire rule systems not only impose transaction costs but also generate transaction benefits. The perception of received transaction benefits affects the evaluation of sludgy choice environments no less than the subjective experience of related costs. Sludge is often a payment for transaction benefits, so excessive sludge reduction is unacceptable. Sludge should be analysed in terms of both (subjective) transaction costs and (subjectively experienced) transaction benefits.

Sludge is usually associated with certain procedures, e.g., waiting in line, filling out forms, and so on. However, sludge is the outcome of rather complex rule systems that integrate rules, procedures, and processes into a single whole. Moreover, rule systems involve not only end users but also various other actors with specific interests and perceptions. Different actors have specific perceptions of the transaction costs and benefits associated with certain mandatory procedures. Transaction benefits often justify sludge at the systemic level, whereas at the individual level, sludge may be subjectively perceived as excessive friction and costs. Therefore, evaluating sludge related to isolated required actions or procedures (subjectively experienced by users only) is a reductionist way. We need a more holistic picture: sludge should be analysed at both the individual and systemic levels, taking into account the perceptions of all kinds of actors involved in the rule systems.

Although sludge is subjectively experienced by individuals, it is fundamentally a social phenomenon. Therefore, rule systems (as sludgy choice environments) should be considered as social cognitive systems that provide affordances and other cognitive resources for ecologically rational decisions. Individual decision-making strongly relies on others’ knowledge crystallised in context-specific cognitive norms (e.g., shared frames, collective beliefs, social narratives, heuristic rules, etc.). Individuals perceive sludge via cognitive institutions: when faced with sludge, decision-makers use heuristics and other cognitive norms to fit the sludgy environment. The i-sludge approach portrays individuals as rather passive victims of sludge, but in the s-sludge approach, individuals are creative and inventive choice-environment testers and bottom-up institutional innovators. Real people actively seek ways to adapt to sludge, avoid it, or reduce it to an acceptable level: along the way, they jointly co-construct sludge-reducing cognitive norms. Therefore, sludge should be analysed through the prism of socially extended cognition with an emphasis on dynamic social interactions and collectively reassembled cognitive institutions. Studying the interplay between cognition and institutions should be a top priority in sludge research.

Supplementary Material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at https://doi.org/10.1017/S1744137425100350