1. Introduction

The question of why learning a native language (L1) is typically more efficient than acquiring a second language (L2) has long intrigued linguists and educators. The theory of embodied cognition offers a plausible explanation for this phenomenon. According to Barsalou (Reference Barsalou2008), linguistic signs are not arbitrarily linked to the external world but are grounded in perceptual experience. In other words, language learning involves activating not only verbal representations but also various nonverbal modal representations such as vision, movement and emotion (Barsalou, Reference Barsalou2008; Bechtold et al., Reference Bechtold, Cosper, Malyshevskaya, Montefinese, Morucci, Niccolai, Repetto, Zappa and Shtyrov2023; Steinhaeusser et al., Reference Steinhaeusser, Zehe, Schnetter, Hotho and Lugrin2024; Zwaan, Reference Zwaan and Ross2003).

To understand differences in learning efficiency between L1 and L2, it is essential to examine the distinct environments in which these languages are acquired. L1 is typically learned through daily, real-life interactions over many years. During this process, language acquisition is closely tied to gestures, eye movements and the physical orientation of described entities (Bot et al., Reference Bot, Lowie and Verspoor2007; Glenberg & Gallese, Reference Glenberg and Gallese2012; Ibáñez et al., Reference Ibáñez, Kühne, Miklashevsky, Monaco, Muraki, Ranzini, Speed and Tuena2023). This sensorimotor approach to learning establishes a close association between words and their referents. Additionally, L1 proficiency develops in parallel with children’s cognitive growth, fostering strong connections between perception and conceptual understanding through everyday experiences.

In contrast, L2 learning often occurs in formal, structured classroom settings among older children, adolescents or adults who already have a dominant L1. The classroom environment is typically more structured and less immersive, lacking the real-world context that characterizes L1 acquisition. Consequently, L2 learners have fewer opportunities to integrate language with physical and emotional experiences, resulting in weaker perceptual representations than those formed in L1 (Chen et al., Reference Chen, Wang, Zhang and Liu2020; Norman & Peleg, Reference Norman and Peleg2022). This disparity in learning environments helps explain why L1 learning is generally more efficient than L2 learning (Dylman & Bjärta, Reference Dylman and Bjärta2018; Ivaz et al., Reference Ivaz, García and Martínez2016).

Conceptual processing is thought to involve two interconnected systems: the linguistic system and the simulation system (Barsalou, Reference Barsalou2003; Louwerse, Reference Louwerse2008; Paivio, Reference Paivio1971; Solomon & Barsalou, Reference Solomon, Barsalou, Hiraga, Turner and Wilcox2004). The linguistic system conveys meaning through word associations, while the simulation system draws on nonverbal sensorimotor knowledge to recreate real-world experiences. Together, these systems facilitate language comprehension (Barsalou et al., Reference Barsalou, Santos, Simmons, Wilson, de Vega, Glenberg and Graesser2008; Bechtold et al., Reference Bechtold, Cosper, Malyshevskaya, Montefinese, Morucci, Niccolai, Repetto, Zappa and Shtyrov2023; Borghi, Reference Borghi2010; Louwerse, Reference Louwerse2011; MacNiven & Tench, Reference MacNiven and Tench2024; Simmons et al., Reference Simmons, Hamann, Harenski, Hu and Barsalou2008). According to Barsalou’s (Reference Barsalou2008) language and situated simulation (LASS) theory, the linguistic system enables individuals to express stored concepts by forming networks of semantically related words, encompassing various word classes and conceptual relationships. Beyond these linguistic associations, comprehension also engages simulation processes, which reenact perceptual and motor experiences associated with described concepts.

Building on this theoretical framework, studies have shown that native-language comprehension spontaneously activates perceptual visual information matching the visual features of objects described in sentences, thereby facilitating semantic integration (Ahn & Jiang, Reference Ahn and Jiang2018; Sato et al., Reference Sato, Schafer and Bergen2013; Wang et al., Reference Wang, Kay, Naselaris, Tarr and Wehbe2022; Winter & Bergen, Reference Winter and Bergen2012). This process integrates input with linguistic and real-world knowledge to construct complete sentence meaning. Sentence–picture verification (SPV) tasks are frequently used to examine this phenomenon. In such tasks, participants read or listen to a sentence (e.g., ‘There is an eagle in the sky’) and then verify whether a subsequent picture matches the described object. The visual characteristics of the object (e.g., an eagle with outstretched wings) are implied by the sentence context (e.g., the sky) rather than explicitly described. Participants respond faster when the picture’s visual features match those implied by the sentence, indicating that native speakers typically simulate the visual properties of linguistic content (Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Tresh and Leblond2012; Jones & Trott, Reference Jones and Trott2024; Ostarek et al., Reference Ostarek, Joosen, Ishag, de Nijs and Huettig2019; Pecher et al., Reference Pecher, Zanolie and Zeelenberg2007; Zwaan & Madden, Reference Zwaan, Madden, Pecher and Zwaan2005). An important question is whether such simulation-based effects operate similarly in a second language, where conceptual access may differ (de Koning et al., Reference de Koning, Wassenburg, Bos and van der Schoot2017).

Extending these insights to bilingual contexts, both L1 and L2 processing involve the linguistic and simulation systems, but the strength of their connections differs. According to second-language acquisition theory, associations between L1 words and concepts are more direct and robust than those between L2 words and concepts (Hayakawa et al., Reference Hayakawa, Bartolotti, van den Berg and Marian2019; Kroll & Stewart, Reference Kroll and Stewart1994). L2 words are typically associated with concepts via L1, and the strength of these associations increases with L2 proficiency (Kroll & Stewart, Reference Kroll and Stewart1994). Thus, L1 processing strongly activates the simulation system, whereas L2 processing relies more on the linguistic system, resulting in weaker embodied effects (Baumeister, Reference Baumeister2019). An open question is how these system preferences manifest in language-switching situations, where prior processing in one language may affect subsequent processing in another (Dijkstra & Van Heuven, Reference Dijkstra and Van Heuven2002).

Recent studies have explored how language-switching contexts influence engagement of the linguistic and simulation systems during L1 and L2 processing. For example, when late bilinguals – who primarily acquired and used their L2 in formal settings – perform sentence-reading tasks in both L1 (Hebrew) and L2 (English), a significant embodied effect appears only in L1. This finding suggests that L1 comprehension activates perceptual visual simulations to a greater extent than L2 comprehension. Moreover, task order modulates this difference: When participants first complete the L1 task and then the L2 task, the L1-embodied effect is significant; however, when the order is reversed, the L1-embodied effect disappears. This pattern indicates that prior L2 processing affects the degree of system involvement during subsequent L1 processing (Norman & Peleg, Reference Norman and Peleg2022). These observations raise important questions about whether such effects reflect inherent differences in system preferences between L1 and L2 (Wentura et al., Reference Wentura, Shi and Degner2024).

Following from these findings, we propose that the L1 system shows an inherent preference for the simulation system, as its natural acquisition through everyday use cultivates strong perception–concept connections. In contrast, L2 learning typically occurs in formal settings and lacks immersive experiences that strengthen perceptual representations; consequently, it exhibits an intrinsic preference for the linguistic system. Drawing on the findings of Norman and Peleg (Reference Norman and Peleg2022), we further infer that in bilingual switching contexts, the system activated by the language processed first influences the system subsequently engaged by the following language. For instance, when switching from L2 to L1, the activation of the linguistic system during L2 processing may lead L1 to rely more heavily on the same system in subsequent processing, thereby weakening embodied effects.

A critical factor likely to shape this system-preference mechanism is L2 proficiency. Zhao et al. (Reference Zhao, Huang, Chen, Jiao, Marmolejo–Ramos, Wang and Xie2019) examined modality-switching costs in high- and low-proficiency bilinguals and found that the magnitude of these costs was modulated by L2 proficiency. When processing L1, high-proficiency bilinguals exhibited smaller modality-switching costs than low-proficiency bilinguals, whereas the reverse pattern emerged in L2 processing.

In summary, while existing evidence points to different activation patterns in the linguistic and simulation systems when bilinguals switch languages, prior studies have not rigorously controlled for L2 proficiency, leaving unclear how proficiency modulates the activation of visual simulations during sentence comprehension in bilingual contexts. Further research is needed to clarify this relationship.

2. The purpose of the present study

This study investigates how L2 proficiency affects embodied effects in L1 and L2 processing within bilingual contexts. To this end, a typical SPV task was employed, in which participants read sentences and then responded to target pictures. All sentences described an object (e.g., a carrot) in a specific context (e.g., soup) and implied its shape (e.g., carrot slices). After each sentence (e.g., ‘The woman saw the carrot in the soup’), a picture of an object (e.g., carrot) was presented, and participants decided whether the pictured object had been mentioned in the sentence. In critical trials, the pictured object corresponded to the one mentioned in the sentence. When the sentence and picture matched, the pictured shape corresponded to that implied by the sentence (e.g., carrot slices), whereas in the mismatch condition, the shape differed (e.g., a whole carrot). If participants mentally simulate the described situation and strongly activate visual shape information during sentence comprehension, they should exhibit a significant embodied effect, reflected in faster responses under matching than mismatching conditions. Conversely, if participants rely mainly on linguistic mechanisms without constructing visual simulations, their response latencies should not differ between conditions.

Based on this task setup, we used a 2 × 2 × 2 × 2 mixed experimental design to examine four two-level factors: target language (Chinese as L1 versus English as L2), shape type (match versus mismatch), L2 proficiency (low versus high) and experimental block (first versus second). The target language factor examined the differential roles of Chinese and English in processing. Shape type distinguished performance with and without visual congruence, assessing the impact of visual cues. To mitigate potential sequence effects, the experiment consisted of two blocks, with one group completing Chinese first and English second and the other group the reverse.

Based on this design, we hypothesize that under the L2 → L1 condition, bilinguals with different proficiency levels will differ in their L1 processing patterns. For low-proficiency bilinguals, limited training in the linguistic system should mean that L2 processing does not affect subsequent L1 processing, allowing L1 to maintain its embodied effect. For high-proficiency bilinguals, the stronger linguistic system may cause prior L2 processing to influence subsequent L1 processing, leading to the disappearance of the L1 embodied effect.

3. Method

3.1. Participants

In this study, 30 participants with low L2 proficiency and 30 with high L2 proficiency were recruited. All were students at South China Normal University, aged between 18 and 24 years (M = 22). To evaluate participants’ second-language proficiency, a three-step assessment was administered: a language history questionnaire, a self-assessment scale and an online vocabulary decision test. The language history questionnaire assessed participants’ language background and usage history, while the self-assessment scale required them to rate their bilingual proficiency. These initial assessments were followed by an objective online vocabulary decision test, which verified whether participants’ L2 proficiency met the stringent inclusion criteria for each group.

3.2. L2 Proficiency measure

The low-proficiency group comprised 30 English learners who either failed the College English Test (CET)-4 or scored below 500, indicating limited English proficiency. The high-proficiency group included 30 advanced English learners who scored 580 or above on the CET-6 or passed the CET-8, reflecting advanced English skills. All participants were right-handed, had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and reported no cognitive impairments. The study was approved by the Ethics Committee of South China Normal University, and all participants provided written informed consent before participation. After screening, based on these criteria, all participants were eligible to participate in the investigation of bilingual processing mechanisms.

3.3. Pretests

To ensure the comprehensibility and validity of the experimental materials, several pretesting procedures were conducted with separate groups of participants. (1) Sentence comprehensibility. An additional 20 participants who did not take part in the main experiment were recruited to translate all English sentences into Chinese. Only sentences that were correctly translated by at least 80% of these participants were included in the formal experiment, ensuring that the critical English sentences were generally comprehensible. (2) Picture naming consistency. Another group of 20 native Chinese speakers, who were also not involved in the main experiment, were recruited to name each picture. Only pictures that received the standard name from at least 80% of the participants were retained, guaranteeing that the critical pictures evoked the intended concepts. (3) Picture–sentence correspondence. Furthermore, a third group of 20 participants, distinct from those in the main experiment and prior pretests, was recruited to evaluate the materials. Following the procedure of Connell (Reference Connell2007), they judged the correspondence between pictures and sentences. Only picture–sentence pairs selected as matching by at least 80% of the participants were included in the experiment, ensuring that the critical sentences effectively implied the target object’s shape.

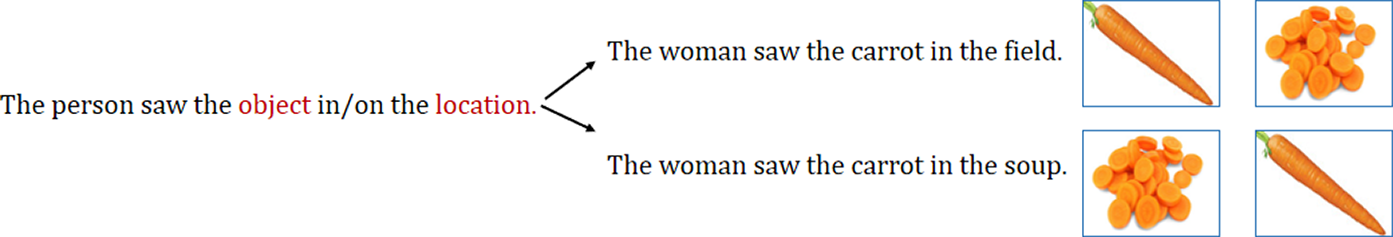

3.4. Materials

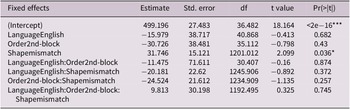

The experimental materials consisted of 48 pairs of images, each depicting two distinct shapes of the same object (e.g., a whole carrot versus carrot slices), along with 24 pairs of Chinese sentences and 24 corresponding English translations. As shown in Figure 1, all sentences shared the same structure: ‘Someone saw something somewhere’. Each sentence pair described the same object in two different locations (e.g., ‘A woman sees the carrot in the field’ versus ‘A woman sees the carrot in the soup’), implying two distinct object shapes.

Figure 1. Experimental material design.

To operationalize the match and mismatch conditions, each sentence was paired with two pictures depicting different object shapes. In the match condition, the pictured shape corresponded to the sentence’s implied shape, whereas in the mismatch condition, it did not. The factors – target language (L1 Chinese versus L2 English), sentence version (Shape 1 versus Shape 2) and picture version (Shape 1 versus Shape 2) – were balanced across eight experimental lists. Each participant saw only one list of 48 key items, divided equally between the Chinese and English tasks (24 per language, 12 match and 12 mismatch trials). See Figure 2.

Figure 2. Sample experimental material.

To balance responses and minimize biases, 96 filler trials were added (48 in Chinese and 48 in English). In each language, 12 fillers required a ‘yes’ response and 36 required a ‘no’. To prevent participants from focusing solely on the object, ‘yes’ fillers presented pictures of locations (e.g., a book bag after ‘The boy saw the book in the bag’).

This design ensured that any response differences between match and mismatch conditions reflected recognition of distinct representations of the same object rather than visual discrepancies.

3.5. Procedure

As outlined in the study design, we adopted a 2 (target languages: L1 – Chinese and L2 – English) × 2 (shape types: match and mismatch) × 2 (L2 proficiency levels: low and high) × 2 (experimental blocks: first and second) mixed experimental design. Following this design, high- and low-proficiency participants completed the experiment in separate groups. All participants were tested individually in a soundproof room, seated 57 cm from a computer screen with head position stabilized by a chin rest. They completed two language tasks consecutively: the L1 and L2 tasks. The order of the two tasks was counterbalanced, with half the participants performing the L1 Chinese task first and the other half starting with the L2 English task. Each participant was randomly assigned one list consisting of two key object sublists, one per language task. Stimuli appeared in randomized order within each sublist, and eight different experimental lists were evenly distributed among participants. We ensured that each participant saw each key object only once.

The experiment lasted about 30 minutes and consisted of six sections performed in a fixed order: (1) handedness assessment using a computerized version of the Edinburgh Handedness Inventory (Oldfield, Reference Oldfield1971); (2) completion of L2 history and self-assessment questionnaires; (3) performance of the SPV task in L1 (Chinese) or L2 (English); (4) performance of the SPV task in the other language; (5) completion of an English–Chinese translation posttest; and (6) completion of the online English version of LexTALE (Lemhöfer & Broersma, Reference Lemhöfer and Broersma2012).

At the start of each language block, participants were instructed to respond as quickly and accurately as possible. In each trial, participants judged whether the object in the picture had been mentioned in the preceding sentence by pressing a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ button. Experimental instructions were presented for both blocks in Chinese. After reading the instructions, participants were shown four sentence–picture matching examples, presented either in Chinese (first-language block) or in English (second-language block). Participants then completed a short practice session of six sentence–picture combinations, half requiring a ‘yes’ response and half ‘no’, in the respective language block. Visual feedback on accuracy was provided at the end of the practice.

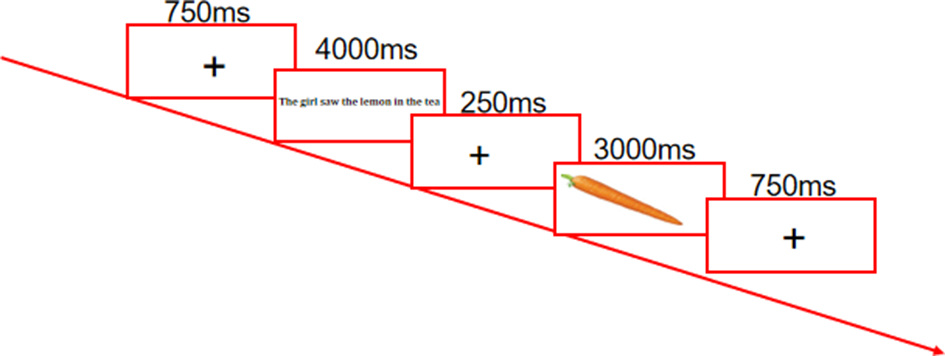

All trials followed the same sequence. As shown in Figure 3, a central fixation cross was displayed for 750 milliseconds, followed by a centrally presented sentence for 4000 milliseconds, allowing sufficient processing time. Next, a central fixation cross appeared for 250 milliseconds, followed by a centrally presented picture displayed for 150 milliseconds. Finally, a white screen was shown until a response was made or until 3000 milliseconds elapsed. Response time (RT) was recorded from picture onset, and accuracy was logged. We programmed and ran the task using E-Prime software (version 10.242; Psychology Software Tools, Pittsburgh, PA). Sentences were displayed in black Times New Roman font on a white background in Chinese or English. Pictures occupied a 6 × 6 cm square surrounded by a 1-cm white frame and were displayed on a gray background. Reaction time (RT) and error data for each response were collected using the Psychology Software Tools (PST) serial response box.

Figure 3. Sentence–picture matching task flow chart.

3.6. English–Chinese translation posttest

To ensure participants understood the exact meaning of the key English sentences, at the end of the experiment, they translated all key sentences from the L2 English task into Chinese.

4. Results

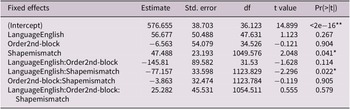

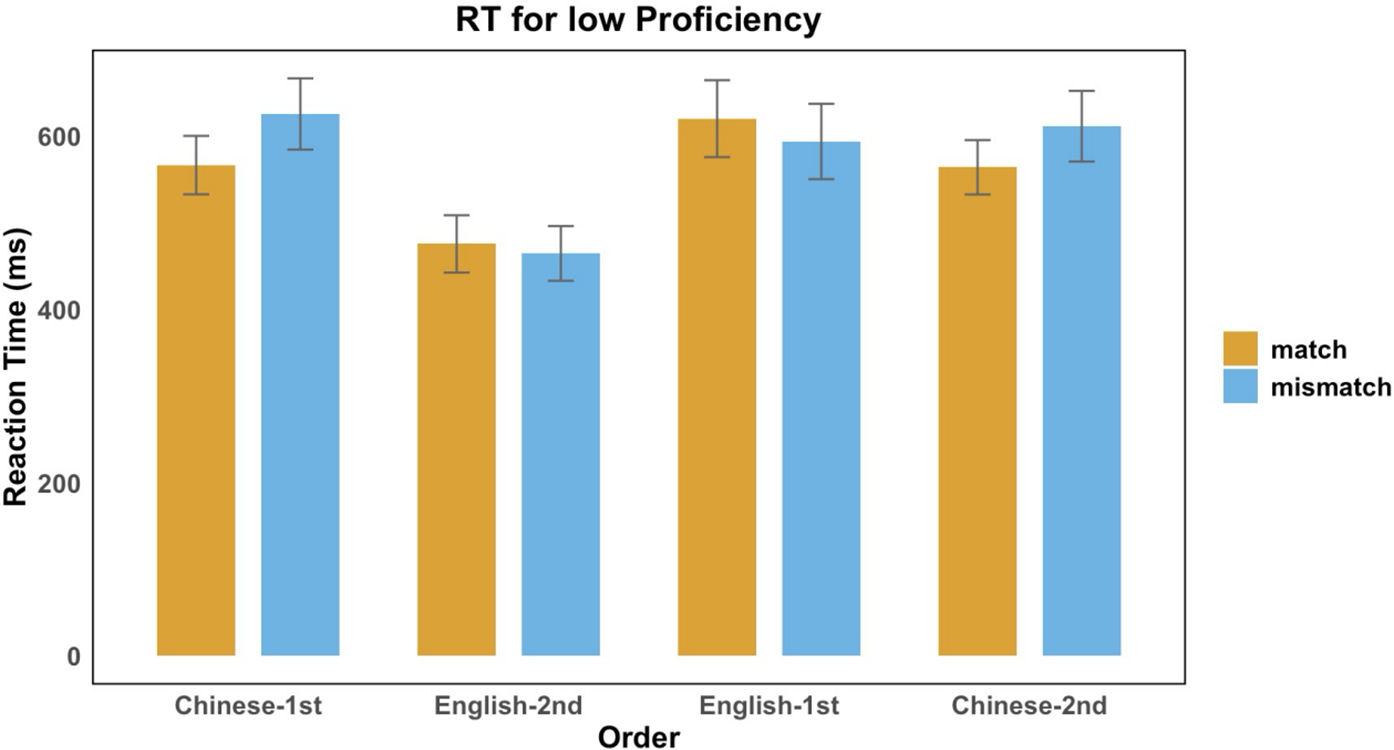

We excluded the following trials from the analysis: (1) fifteen English trials that were incorrectly translated in the English–Chinese translation posttest, (2) trials with RTs ≥3000 ms or ≤200 ms, (3) trials with RTs falling outside two standard deviations from the mean and (4) trials with incorrect responses. We then analyzed the RT data using a linear mixed-effects (LMEs) model (Baayen et al., Reference Baayen, Davidson and Bates2008) implemented via the ‘lmer’ function in the ‘lme4’ package in R (version 4.4.0). The data analysis focused on the fixed effects of language type, shape condition (match/mismatch), L2 proficiency and language block, as well as their interactions. See Table 1.

Table 1. Descriptive statistical results

We fit a full model to the RT data, including language type, shape type, experimental condition, L2 proficiency and all possible interactions to accurately estimate the effects of each variable. To test which model fit the data better, we compared models using the likelihood ratio test via the ‘ANOVA’ function, which yields chi-square statistics. We then selected the model that best fit the data for further analysis. Effect sizes were calculated using Cohen’s d, computed as the mean difference divided by the pooled standard deviation, with small-sample bias corrected according to Lakens’ (Reference Lakens2013) adjustment method. To assess the significance of the main effects and interactions in the selected model, we calculated a type II analysis of variance (ANOVA) with the Wald chi-square test via the ‘ANOVA’ function. Finally, we used the ‘test Interactions’ function to conduct chi-square tests with the Bonferroni adjustment for pairwise comparisons of factor interactions.

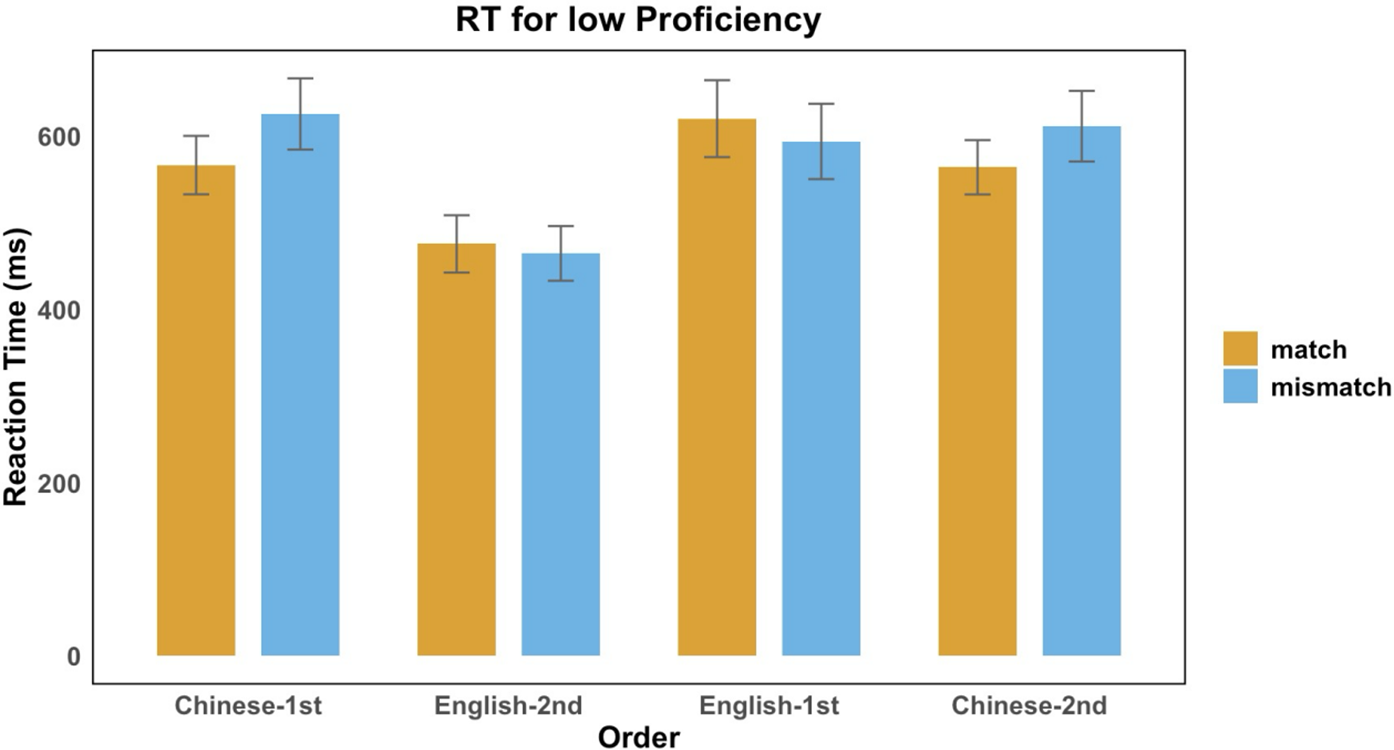

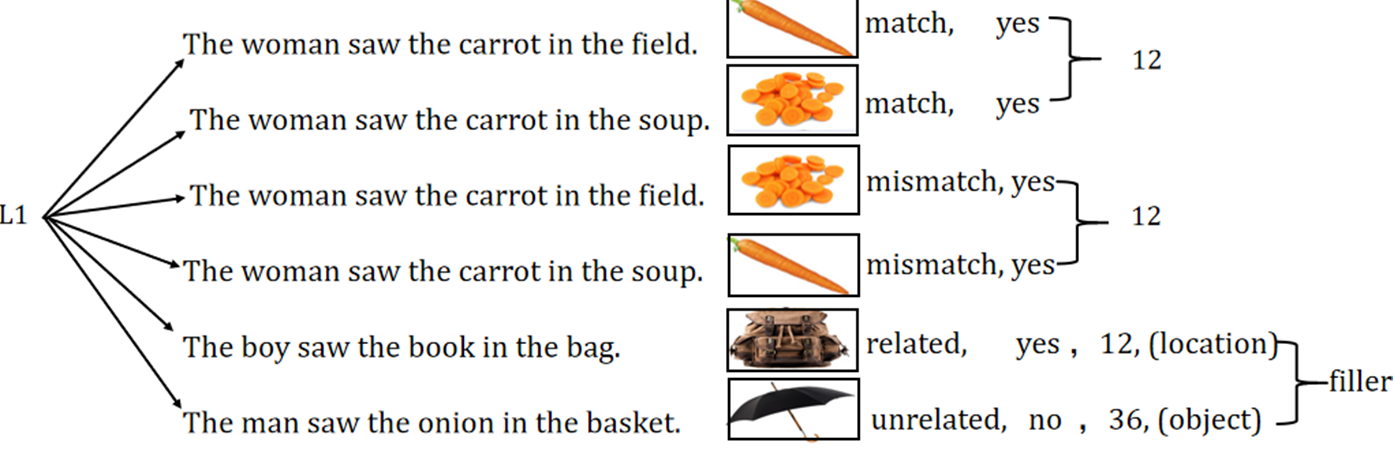

To analyze the data of participants with low proficiency, we fit an LME model, lmer(RT ~ Language × Order × Shape + (1 + Language | sub) + (1 | Item)), to the RT data that shown in Figure 4. The model includes the fixed effects of language (Chinese and English), order (Block 1 and Block 2) and shape (match and mismatch), as well as all their interactions. The model also accounted for random intercepts and random slopes for subjects (sub), as well as random intercepts for items, to capture grouping variability in the data. Table 2 shows the results of the LME model for low-proficiency bilinguals. Language (English) did not significantly affect RT (p = 0.267). The effect of the second block on RT was not significant relative to the first block (p = 0.904); therefore, sequential change had no significant effect on RT. The mismatched shape significantly increased RT relative to the matched shape (β = 47.488, standard error [SE] = 23.198, t = 2.048, p = 0.041). Thus, RT increased significantly when shapes did not match. The interaction between language (English) and block order (second block) had no significant effect on RT (p = 0.114). There was no significant interaction between order and shape (p = 0.905). The three-way interaction among language (English), block order (second block) and shape (mismatch) was not significant (p = 0.578). However, the interaction between language (English) and shape (mismatch) was significant (β = −77.157, SE = 33.598, t = −2.296, p = 0.022). No other factors or interactions significantly affected RT.

Figure 4. The reaction time of low-proficiency bilinguals.

Table 2. The results of a linear mixture model of low-proficiency bilinguals

Note: Sig. codes (p-values): *p<.05, **p<.01.

Further simple effects were also analyzed. As shown in Table 2, in the first block under Chinese conditions, RT for matched shapes was faster than for mismatched shapes, showing a significant effect (β = −47.49, SE = 23.2, t = −2.047, p = 0.041, Cohen’s d = 0.243). In the first block under English conditions, shape matching had no significant effect on RT (p = 0.224). In the second block under Chinese conditions, RT for matched shapes was faster than for mismatched shapes, but the effect was marginally significant (β = −43.62, SE = 22.8, t = −1.915, p = 0.0558, Cohen’s d = 0.223). In the second block under English conditions, shape matching had no significant effect on RT (p = 0.732). These results suggest that under Chinese conditions, shape matching facilitated RT, especially in the first block, whereas under English conditions this effect was not significant.

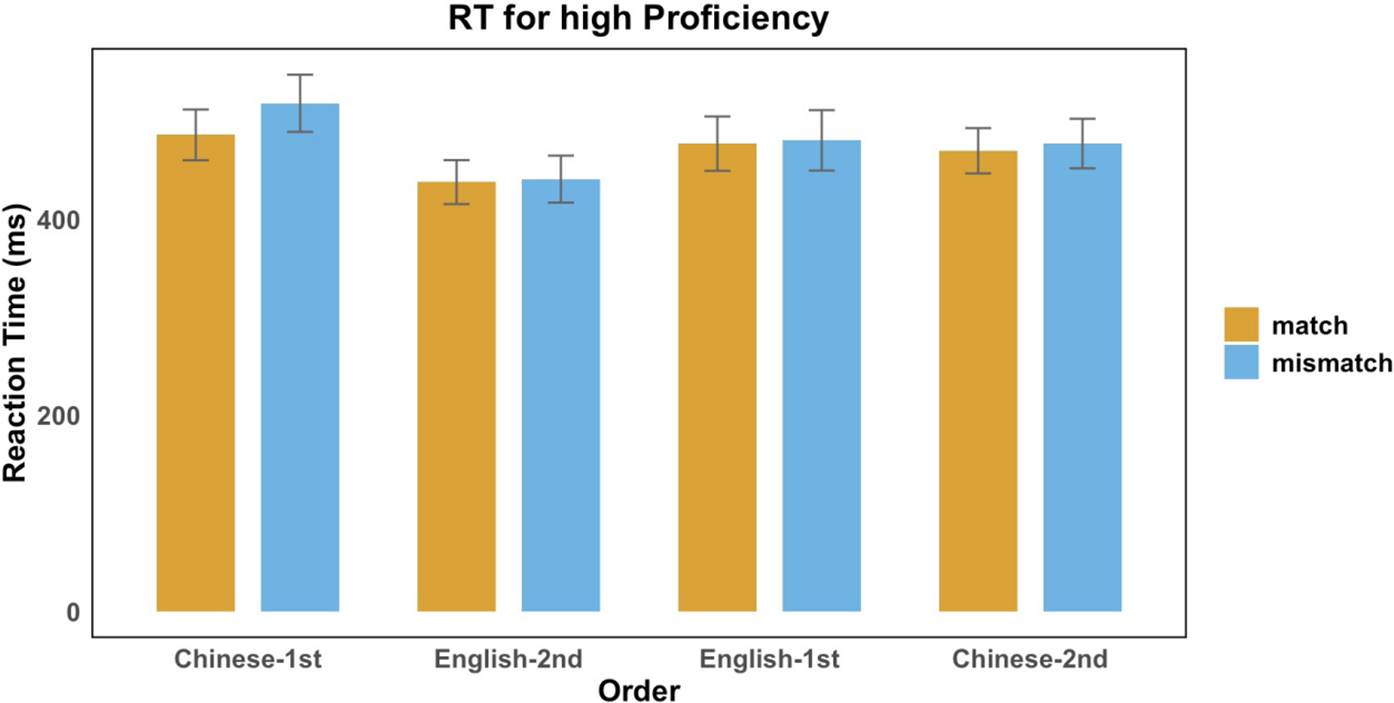

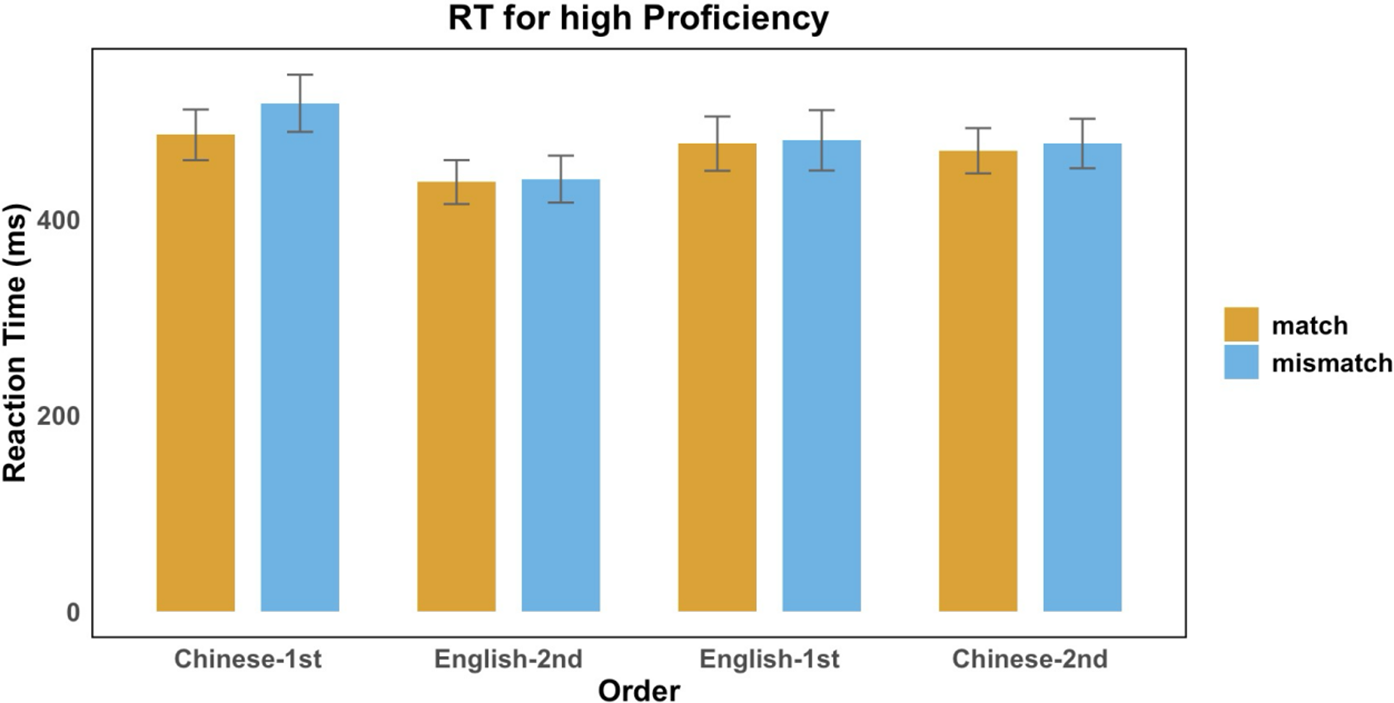

We fit the same LME model to the RT data (Figure 5) to analyze participants with high proficiency. Table 3 shows the results of the LME model for high-proficiency bilinguals. Language (English) did not have a significant effect on RT compared to the reference language (p = 0.682). Similarly, the second block had no significant effect relative to the first block (p = 0.43), indicating that block order did not significantly influence RT. However, mismatched shapes significantly increased RT compared to matched shapes (β = 31.746, SE = 15.121, t (1201.012) = 2.099, p = 0.036). Thus, RT increased significantly when shapes did not match. The interaction effects between language and block order (p = 0.874), language and shape (p = 0.372), order and shape (p = 0.257) and the three-way interaction among language, order and shape (p = 0.745) were all nonsignificant. In conclusion, compared to low-proficiency bilinguals, high-proficiency bilinguals showed a significant increase in RT for shape mismatches, but language and block order effects were not significant. This suggests that highly proficient bilinguals may be more sensitive to shape mismatches, while language switching exerted little influence on their RT.

Figure 5. The reaction time of high-proficiency bilinguals.

Table 3. The results of a linear mixture model of high-proficiency bilinguals

Note: Sig. codes (p-values): *p<.05, ***p<0.001.

We further analyzed simple effects for highly proficient bilinguals under different language and block order conditions. In the first Chinese block, RT was significantly faster for matched shapes than for mismatched shapes (β = −31.75, SE = 15.1, t (1024) = −2.098, p = 0.036, Cohen’s d = 0.237). However, in the first English block, shape matching did not significantly affect RT (p = 0.486). Similarly, in the second blocks of both Chinese (p = 0.646) and English (p = 0.846), shape matching showed no significant effect. These results indicate that among highly proficient bilinguals, shape matching significantly facilitated RT only in the first Chinese block; in all other conditions, no significant effect was observed.

5. Discussion

The present research examined how L2 proficiency influences embodied effects in L1 (Chinese) and L2 (English) within bilingual contexts. The findings provide three key insights. First, low-proficiency bilinguals exhibited stronger sensorimotor simulation effects in L1 than in L2. When switching from L1 → L2, embodied effects were observed in L1 but not in L2; in the L2 → L1 sequence, L2 again showed no embodied effects, whereas L1 displayed a marginally significant effect, suggesting that L2 processing may have influenced L1, although the effect appears weak. Second, high-proficiency bilinguals demonstrated a distinct pattern: While embodied effects persisted in L1 during L1 → L2 switching, they disappeared entirely in the L2 → L1 sequence. This pattern may result from the activation of the linguistic system during L2 processing, which promotes greater reliance on this system in subsequent L1 tasks or inhibits engagement of the simulation system. Third, the effect of L2 processing on L1 emerged only in high-proficiency bilinguals, likely because their linguistic system is more fully developed. Consequently, the influence of the linguistic system is stronger. Together, these findings suggest that bilingualism does not merely attenuate embodied processing but dynamically reorganizes system engagement depending on proficiency level and language-switching context.

Our findings are consistent with previous studies examining embodiment effects in L1 and non-L1 languages. Many studies have reported the dominance of the simulation system in L1 (Nijhof & Willems, Reference Nijhof and Willems2015; Zwaan, Reference Zwaan2016). Using delayed SPV tasks, Chen et al. (Reference Chen, Wang, Zhang and Liu2020) found significant perceptual–match effects only in L1, with weaker or absent effects in L2 and L3. They concluded that non-L1 languages operate within more constrained perceptual representations. Similarly, Norman and Peleg (Reference Norman and Peleg2022) observed an embodied effect in L1 – Hebrew but not in L2 – English among late bilinguals, attributing this to cross-language influences from sequential task performance. However, their study did not rigorously control for L2 proficiency, leaving a gap in understanding how proficiency modulates these effects. Recent work has highlighted proficiency as a crucial moderator: Wang and Zhao (Reference Wang, Zhao and Kubincová2024) reported that higher L2 proficiency strengthens perceptual-match effects, whereas lower proficiency yields reduced or absent embodiment (Grauwe et al., Reference Grauwe, Willems, Rüschemeyer, Lemhöfer and Schriefers2014). The present study directly addresses this limitation by explicitly manipulating proficiency levels and comparing system engagement across switching directions.

To interpret these differences between low- and high-proficiency bilinguals, we draw on the LASS theory (Barsalou, Reference Barsalou2008), which posits that language comprehension engages both the linguistic and the simulation systems. Low-proficiency bilinguals’ reliance on the simulation system for L1 and on the linguistic system for L2 mirrors Chen et al.’s (Reference Chen, Wang, Zhang and Liu2020) findings of L1 dominance. Conversely, high-proficiency bilinguals’ reduced activation of the simulation system during L2 → L1 switching aligns with Norman and Peleg’s (Reference Norman and Peleg2022) observations of cross-language interference while introducing proficiency as a moderating factor. This finding suggests that higher L2 proficiency enables bilinguals to adjust system preferences dynamically during language switching – a mechanism not fully examined in prior research.

The divergence in system activation between low- and high-proficiency bilinguals further supports the LASS framework. For low-proficiency bilinguals, L1 processing remains rooted in the simulation system due to its strong sensorimotor grounding, whereas L2 processing relies more heavily on weaker linguistic associations. In contrast, among high-proficiency bilinguals, the attenuation of simulation effects in L1 during L2 → L1 switching suggests a proficiency-driven reconfiguration of system dominance, possibly reflecting the emergence of L2-specific conceptual representations (Kroll & Stewart, Reference Kroll and Stewart1994). These results collectively underscore that proficiency modulates not only the strength of embodied effects but also the direction of cross-linguistic influence.

The observed cross-lingual contextual effects among high-proficiency bilinguals further highlight the role of dynamic system preference in language switching. Such flexibility supports the view that prior language use shapes subsequent processing through transient shifts in system activation. High-proficiency bilinguals thus experience stronger cross-linguistic interference due to robust engagement of the linguistic system, whereas low-proficiency bilinguals show minimal interference owing to their limited reliance on that system. This nuanced pattern clarifies why only highly skilled bilinguals exhibit L2 → L1 modulation of embodied effects in our data.

While this study advances understanding of the role of L2 proficiency in embodied effects, several limitations warrant consideration. First, the use of a controlled laboratory task (SPV) may not fully capture real-world bilingual language use, where contextual and social factors play substantial roles. Second, the binary classification of proficiency (high versus low) oversimplifies the continuum of L2 mastery. Future research should therefore employ continuous proficiency measures (e.g., standardized test scores) to explore gradational effects and their nonlinear impacts.

The precise mechanism through which L2 proficiency modulates simulation system activation remains an open question. One possibility is that higher proficiency strengthens L2-specific conceptual representations; another is that it enhances general cognitive control, which, in turn, modulates cross-language interference. Previous studies suggest that cognitive control may shape bilingual switching performance (Liu et al., Reference Liu, Yang, Jiao, Schwieter, Sun and Wang2019). Thus, to elucidate these underlying processes, future research could integrate neuroimaging techniques (e.g., functional magnetic resonance imaging [fMRI]) to examine the neural correlates of simulation and linguistic system activation, assess whether intensive L2 immersion enhances embodied effects by reinforcing sensorimotor associations and explore how individual differences interact with L2 proficiency to influence language processing.

Although the present findings are grounded in embodied cognitive frameworks, these theories have traditionally underemphasized the role of cognitive control and environmental exposure. The contrast between naturalistic L1 acquisition and classroom-based L2 learning, while informative, cannot fully capture the influence of language frequency and contextual diversity in everyday use. Furthermore, the hypothesized trade-off in resource allocation between simulation and linguistic systems currently lacks direct empirical validation. Thus, future studies should combine behavioral, neurocognitive and ecological approaches to examine how learning environment and usage patterns jointly shape system engagement in bilingual minds.

6. Conclusion

This study proposes that the linguistic and simulation systems operate synergistically during language processing and that the system activated first influences engagement in subsequent processing. The findings confirm that L2 proficiency significantly modulates embodied effects in bilingual contexts. Specifically, when switching from L2 to L1, bilinguals with higher L2 proficiency exhibit stronger reliance on the linguistic system, whereas those with lower proficiency depend more on the simulation system. Critically, the system activated during prior language use (e.g., the L2 linguistic system) influences subsequent language processing (e.g., L1) and does so most strongly among highly proficient bilinguals in L2 → L1 switching scenarios. This result underscores the dynamic interplay between language proficiency and processing mechanisms, demonstrating that the system of the initially used language can shape processing strategies in the subsequent language.

By validating these hypotheses, the present study advances understanding of how bilinguals adapt embodied processing strategies during language switching, emphasizing L2 proficiency as a key determinant of system balance. These insights refine theoretical frameworks of embodied bilingual cognition (e.g., LASS theory) and highlight the importance of examining how proficiency-driven changes in conceptual representations shape sensorimotor simulation across languages. Future work should explore whether L2 immersion or sensorimotor training can enhance embodied effects in L2, thereby clarifying the plasticity of interactions between the simulation and linguistic systems.

Data availability statement

All R scripts, data files and output are available on the OSF: https://osf.io/29bnw/overview?view_only=41aa2716760b4b84825d906ead187296. None of the work in this study was preregistered.

Acknowledgements

This research was supported by the National Natural Science Foundation of China (32371114); Guang Dong Basic and Applied Basic Research Foundation(2024A1515012354); Grant from Research Center for Brain Cognition and Human Development, Guangdong, China (No. 2024B0303390003); and Striving for the First-Class, Improving Weak Links and Highlighting Features (SIH) Key Discipline for Psychology in South China Normal University.

The research was approved by the Institutional Review Board of the School of Psychology at South China Normal University.

Author contribution

Yuying Xiao and Si Liu contributed equally to this work and share first authorship.

Competing interests

We have no conflicts of interest to report.