Introduction

In 2024, the province of Almería, in southeastern Spain, consolidated its position as ‘Europe’s market garden’, exporting 2.73 million tonnes of fruit and vegetables valued at €3.85 billion.Footnote 1 The majority of this production was grown in solar greenhouses, which cover a total provincial area of nearly 33,000 hectares.Footnote 2 Andalusia, the southernmost autonomous community and home to Almería, reached 59,413 hectares of greenhouses in 2022.Footnote 3 This places Spain second in the global rankings for greenhouse coverage with 70,000 ha, behind only China, whose surface area reached 82,000 ha.Footnote 4 Consequently, Almería has become the European region with the highest concentration of greenhouses and the primary supplier of fresh fruit and vegetables for the European market (Figure 1).

Figure 1. Province of Almeria (Andalusia-Spain).

Source: Author’s own (mappinggis.com).

From the second half of the 20th century, the Almería coastline underwent a rapid agricultural transformation, evolving into an immense ‘sea of plastic’ specialised in the early-season production of fruit, vegetables, and flowers.Footnote 5 Notably, greenhouse surface area is concentrated in the Poniente coastal regionFootnote 6 and the Níjar/Bajo Andarax region. In 2021, these two areas accounted for 95.7% of the province’s total greenhouse coverage. According to the latest data from the Andalusian government, the Poniente comprised 22,189 ha (67.6%) and Níjar 9,228 ha (28.1%), out of a total of 32,827 ha.Footnote 7

This specialisation is particularly remarkable when examining land distribution in the 2020 agricultural census. Farms smaller than five hectares are predominant: the Poniente records 11,161 such farms covering 16,449 ha, while the Níjar region has 3,884 farms covering 5,954 ha.Footnote 8 However, Eastern Andalusia has traditionally been characterised by small and medium-sized holdings; the 1962 census indicated that farms of less than 5 ha accounted for 69% of the total, compared to 55% in the west (Figure 2).Footnote 9

Figure 2. Region of Poniente and Bajo Andarax/Níjar (Province of Almería).

Source: Author’s own (google.com/maps).

The objective of this study is to examine the causes and key factors that prompted the creation of such a singular and pivotal agrarian space for the European agri-food system, highlighting the role of the smallholder peasantry and land fragmentation. This modernisation process began in the mid-20th century with the intervention of the Francoist state through its colonisation schemes. Furthermore, the timeframe for this study concludes in the second half of the 1980s for two reasons: firstly, basic technological improvements and the commercialisation framework were already fully consolidated; and secondly, Spain’s accession to the European Economic Community (EEC) in 1986 triggered the transformation of existing family agriculture into a new hyper-capitalised, hyper-technified model dependent on migrant labour.

Underpinning the article are a range of key archival and data sources, such as agrarian censuses and diverse statistical information, for instance from the National Statistics Institute (INE) or the Institute of Statistics and Cartography of Andalusia (IECA).We have also analysed data concerning the colonisation plans for the Almería coast drawn from INC reports, the evolution of land prices and markets, and the process of technological modernisation itself. Archival sources such as the Archivo de la Diputación de Almería, the Archivo Histórico Provincial de Almería or the Archivo General de la Administración have been consulted.Footnote 10 Our aim is to put into perspective the key factors and their degree of importance in the shaping of this agricultural zone monopolised by small and medium-sized farmers.

Background: resources, limitations and exploitation of the Almeria coastline

The province of Almería has been a land of small farmers since the Muslim period, favoured by the socio-economic structure of the Nasrid Kingdom of Granada (1238–1492) and, subsequently, by the limited nature of the repartimientos (land distributions) carried out after the conquest by the Catholic Monarchs.Footnote 11 The continuity of the Moorish population in the old Nasrid kingdom, who retained most of their possessions, constrained the land available for distribution among the Christian conquerors. Larger plots were distributed among high-ranking officials, giving rise to the creation of some important lordships. In contrast, squires and labourers obtained an average of 1.7 ha and 1 ha respectively, alongside areas of olive groves divided into smaller units. This situation perpetuated the previous agrarian structure and contributed to land fragmentation.Footnote 12

However, a divergent trend developed in subsequent years. On the one hand, land subdivisions increased; on the other, land concentration occurred around ecclesiastical lordships. Despite this, it is worth noting that while large estates existed in Eastern Andalusia, they were neither as extensive nor as productive as those in the west.Footnote 13 Furthermore, the disentailments of Mendizábal (1835) and Madoz (1855) had a moderate impact on the region, mainly affecting clergy and municipal properties.Footnote 14 The bourgeoisie and large local landowners were the prominent purchasers; however, their acquisitions were characterised by dispersion, which prevented land concentration. Except for coastal estates, which fetched high prices, most properties were rainfed.Footnote 15 Similarly, the geographical conditions in which the former Nasrid Kingdom developed had a profound influence on both land tenure and farming practices. The essentially mountainous nature of southeastern Spain, with its heartland in the Sierra Nevada and its ranges extending through the present-day provinces of Málaga, Granada, and Almería, was a determining factor in the development of small-scale agriculture. Thus, since time immemorial, the land has been characterised by smallholdings and terraced agriculture.

However, the coastal plains of the southeast offered ideal climatic conditions for agricultural development, despite lacking a fundamental resource: water. The west-east orientation of the Sierra Nevada places a large part of the Almería coastline in its rain shadow, causing a shortage of rainfall and contributing to its extreme aridity. As Christian Mignon noted, ‘the agriculture developed in the south-east of the peninsula is conditioned by its mountainous character and is therefore an agriculture that is the child of the mountains’.Footnote 16 One of the physical factors explaining the development of intensive agriculture in Almería, rather than in other areas, lies in its exceptional climatic conditions. The combination of over 3,000 hours of annual sunshine, mild winter temperatures, and low relative humidity created an ideal microclimate for greenhouse crops, particularly in winter, as it maximises solar radiation and minimises crop diseases.Footnote 17

In summary, until the end of the 19th century, agriculture in the province of Almería was predominantly confined to mountainous areas where water resources were available. These activities were limited to smallholdings and largely dedicated to subsistence farming. Conversely, the coastal plains, deficient in water and possessing extremely arid soils, remained mainly uncultivated. They were marginally utilised for livestock grazing or, in exceptional cases, for snail gathering.Footnote 18

The first irrigation infrastructure on the Almeria coast

Although for most of the 19th century, Almería’s economy was primarily based on lead and iron miningFootnote 19, attempts were made to expand irrigation.Footnote 20 In its last quarter, the province entered a new economic cycle based on the agricultural sector. The grape business, specializing in the cultivation of an indigenous variety called ‘Ohanes’Footnote 21, became such a profitable enterprise that it spread throughout the province.Footnote 22 This new economic era provided renewed impetus to initiatives that sought to develop the under-utilised coastal plains, especially in the Poniente. Consequently, the need to obtain new sources of water to increase the agricultural area meant the search for a new ‘El Dorado’. From the first quarter of the 19th century onwards, various attempts aimed to irrigate the Poniente region, although, due to their difficulty, they failed.Footnote 23

It was towards the end of the 19th century that the hydraulic infrastructure of the San Miguel de Fuente Nueva gallery was planned. A company formed by residents of the municipal territory of Dalías applied for a mining concession to extract water; this was granted in 1891, and after several years of work, the new water flow was brought onstream in 1894. The aim was to transport water resources from the Sierra de Gádor to the farms of the company’s shareholders on the plains, in the vicinity of the present-day municipal territory of El Ejido. By 1900, 27 km of irrigation channels had already been constructed to carry water to Las Norias de Daza, in the south of the El Ejido municipal territory.

Following this enterprise, private initiative once again focused its efforts on expanding irrigation in the region. This subsequent project was led by Fernando García Espín and several businessmen from the province of Granada, who, in 1930, obtained a concession to exploit the groundwater of the Adra River, creating the company ‘Aguas y Cauce de San Fernando S.A.’. Their operations enabled the irrigation of the Dalías countryside from Adra through the progressive construction of 53 km of channels. Estimates made by the Geominero Technological Institute of Spain (ITGE) in 1984 established that the combined contribution of the two systems was approximately 4.5 hm3: 2 hm3 from Fuente Nueva and 2.5 hm3 from the San Fernando channel.Footnote 24 Both companies facilitated the creation of ‘green’ corridors where grape and vegetable agriculture, as well as the communities dedicated to their cultivation, rapidly flourished.

During the 1920s, the company ‘Fuerzas Electromotrices del Valle de Lecrín’ pioneered groundwater extraction in the Poniente region. Utilising energy from its hydroelectric facilities, it supplied public lighting to towns in the area and established mechanised pumping stations for irrigation. However, despite the company’s extensive efforts to construct mechanised wells during the 1930s and 1940s, most fell into disuse. This was due to low demand from farmers, primarily attributed to the poor quality of the water supplied and its high cost.Footnote 25

The high cost of water presented a significant barrier for such an impoverished region; consequently, farmers could afford to irrigate only small plots. When the National Institute of Colonisation (INC) commenced operations in the Poniente region in the 1950s, the irrigated area covered just 2,400 hectares. This supply was sourced from the Dalías surplusFootnote 26, the Fuente Nueva and San Fernando channels, and, to a lesser extent, wells scattered throughout the region.

The INC in Almería and its role in the creation of the ‘plastic sea’

Following the dismantling of the Second Republic’s legal framework and its agrarian reform by the insurgent forces, the newly established dictatorial state deployed various interventionist instruments. For the agricultural sector, the National Institute of Colonisation (INC) was established with the aim of transforming underutilised areas. This was achieved by extending irrigation to new lands and settling colonists, often within newly created villages.Footnote 27 These measures were integral to the autarkic policies the dictatorship sought to implement, driven by ideological imperatives and constrained by international relations during the Second World War.

Before the end of 1939, the Law of 26 December 1939 regarding the colonisation of large areas was enacted, laying the foundations for State intervention in many of the country’s districts.Footnote 28 This was succeeded by the Law of 25 November 1940 on colonisations of local interest, which aimed to intervene in smaller areas not covered by the 1939 legislationFootnote 29, including the Poniente region.Footnote 30These laws marked the onset of state intervention across Spain’s agricultural zones. Generally speaking, the propaganda value of Franco’s colonisation policy—typified by the inauguration of new towns and hydroelectric dams—far outweighed its tangible impact.Footnote 31 While initiatives were launched to transform numerous regions and settle large numbers of colonists, practical results were limited, save for a few exceptions such as the Poniente. Most areas remained underdeveloped; allocated plots were often insufficient for family subsistence; patronage heavily influenced plot distribution; and large landowners profited from land appreciation or the sale of poor-quality terrain to the State at inflated prices.Footnote 32 Notwithstanding these shortcomings, colonisation policies in Andalusia successfully transformed 250,000 hectares into irrigated land and resulted in the construction of 130 new villages.Footnote 33

As previously noted, land ownership in the Poniente was not highly concentrated when the INC commenced operations, although some large holdings owned by absentee landlords existed. The Institute’s multifaceted approach included infrastructure development, the provision of irrigation, and the settlement of colonists. Its most fundamental contribution to the Almería coast was the expansion of the water supply through the construction of mechanised wells. This development enabled many farmers, previously priced out of the market, to access irrigation. In the 1950s, water prices stood at 0.238 ptas/m3 from the San Fernando Canal; 0.308 ptas/m3 (summer) and 0.185 ptas/m3 (winter) from the Fuente Nueva Canal; and 0.20 ptas/m3 from the ‘Valle de Lecrín’ wells. Following the INC’s drilling of the first mechanised wells, the introduction of new flows drastically reduced the price to 0.0395 ptas/m3. This affordability provided the primary stimulus for bringing previously abandoned land into production.Footnote 34

The transformation area was divided into different sectors, starting the works from an east-west axis, that is, from Aguadulce (Sector I) to Adra. The first search for settlers in the 1950s did not find much support among the population of Almería due to ideological issues, as the poorest members of society distrusted the social initiatives of a dictatorial regime.Footnote 35 However, after the first interventions of the INC there was a pull effect, shifting from not even half of the places being filled in its first search for settlers, to subsequently receiving a flood of applications. Even so, the data on the settlement of settlers and the distribution of land in this region are modest.

In Sector I, 142 plots were distributed between 1958 and 1961, with an average of 2.1578 ha, with a total area of 306.40 ha, together with 22 vegetable plots of 0.4036 ha on average, covering an area of 8.9791 ha. It should be borne in mind that these first plots that the Institute allocated were theoretically around 3.5 ha in size, although the difficulties this entailed due to the actual limits of the area led to the allocation of quite disparate plots. From 1961 onwards, 122 colonists settled in Sector II on an area of 229.7420 ha (with an average of 1.8831 ha) and 53 vegetable plots averaging 0.3125 ha on an area of 17.14 ha. In Sector III, settlements began in 1971 after the construction of new villages and the process of adapting the expropriated lands, settling some 70 families (average of 2.1395 ha) on an area of 149.7678 ha and 23 family gardens with an average of 0.3419 ha, on an area of 11.01 ha.

Finally, the extension of Sector III became the transformation sector where most land was irrigated. Moreover, the expropriation process was most prominent in this area. According to the data provided by Rivera for this sector, the total area expropriated and transformed into family plots was 742.4931 ha, 738.0236 ha divided between 289 colonists (with an average of 2.5537 ha per holding) and 12 family orchards (with an average of 0.372 ha) covering an area of 4.4695 ha.Footnote 36 In short, the colonisation developed in the Poniente, especially concerning the expropriation and settlement of families, resulted in the installation of 773 colonists, 623 in plots and 110 in family gardens, with a total area of 1,461.8132 ha. It should be noted that, in this process of land allocation, only men were designated as settlers, while women were subordinated to the male head of the household. Although this gender inequality was exacerbated with the rise of the dictatorship, it had already begun in the early 20th century through state policies and the introduction of capitalism into Spanish agriculture.Footnote 37

In addition, there were four more sectors where INC-IRYDA intervened in their transformation, although in a different way.Footnote 38 These new sectors were in the west of the Poniente, but here the land was already distributed in a fairly balanced way. In addition, a large number of holdings had their own wells or water from the Fuente Nueva and the San Fernando Canal. From Sector IV onwards, no more land was expropriated and there were no new settlers, largely because private initiative had already opted for intensive agriculture and the marketing of land, and irrigation was spreading. Also, the colonisation policy planned in 1941 for the settlement of colonists was rapidly changing in favour of a more productivist stance.

Broadly speaking, the colonisation policy planned by the Francoist state did not have the desired effect. The State’s lack of interest and the scant investment made resulted in the poor development of this initiative, with only 9,886 ha of the 576,891 ha that had been declared of national interest being transformed between 1940 and 1951.Footnote 39 However, action on local colonisation achieved better results, transforming 58,000 ha in the same period and improving irrigation on a further 7,000 ha.Footnote 40 Generally, from 1950 onwards, state intervention was oriented towards improving agricultural techniques and productivity, leaving aside colonisation policies, as occurred in the colonisation of the Poniente.Footnote 41

From 1972 onwards, IRYDA’s actions were limited to providing new groundwater flows and constructing the corresponding canalisations.Footnote 42 The flow provided was greater than expected and allowed the Institute to programme the creation of sectors V and VI. However, the problems encountered in the construction of the Benínar reservoir meant that Sector V was not completed, but it was possible to intervene in Sector VI, which was mainly supplied by groundwater. The intervention was extended until the end of the 1970s and was limited to the irrigation and channelling of available water. Overall, the great achievement of INC-IRYDA since the 1950s in the region was the irrigation of some 12,387 ha (Figure 3).

Figure 3. Region of Poniente, towns and sectors.

Source: Author’s own (google.com/maps).

The technological revolution: sand, plastic and water

As this section will demonstrate, the swift adoption of technological innovations, combined with the diffusion of traditional farming techniques, was a pivotal factor in the rapid development of the Poniente. This stands in contrast to other areas where state intervention occurred via colonisation schemes. Almería consolidated its position as Europe’s leading winter agricultural powerhouse, driven by a synergy of ideal climatic conditions, technical innovation, and the strong cooperative capacity of its smallholders. These factors enabled the region to outperform competitors that benefited from state protection, most notably the large estate owners of the Canary Islands. Although the archipelago had pioneered greenhouse cultivation and attempted to curb Almería’s rise through disputes such as the ‘Cucumber and Tomato Wars’, Almería ultimately prevailed, owing to superior productivity and efficient European distribution channels (Figure 4).Footnote 43

Figure 4. Evolution of vegetable production (main cultivated products) in the province of Almería.

Source: Author’s own elaboration based on AEA (MAPAMA) data.

Another of the INC’s functions was to experiment with new agricultural techniques to circumvent the limitations of these areas. Beyond the previously mentioned scarcity of water resources, the poor quality of the land for cultivation posed a further challenge. In this respect, the Almería coastline was extremely arid, with high salinity and highly alkaline soils composed of a 20 to 50 cm layer of limestone crust (hardpan), which rendered them largely infertile.Footnote 44 Consequently, soil suitability became the second major obstacle to developing prosperous agriculture.

To address this, one of the first techniques the Institute began to experiment with was ‘enarenado’ (sand mulching). This traditional cultivation method originated on the Granada coast (Pozuelo and La Rábita) but had already been observed in Adra and along the Balerma-Balanegra coastline.Footnote 45 Furthermore, the initial failure to fill the settler positions offered in Sector I led the INC to recruit families from other localities within the Poniente. Many of these local settlers brought with them the ‘enarenado’ technique in a more or less standardised form. Fundamentally, this consisted of placing a layer of sand, approximately 8 to 12 cm thick, over layers of manure and clay, a practice that offered numerous advantages.

INC technicians observed the benefits of this technique during the early 1950sFootnote 46, and from the following decade onwards, ‘enarenado’ became an integral component of all farms on the Almería coast.Footnote 47 The extensive adoption of sand mulching from the 1960s onwards significantly influenced the development of the colonisation schemes. The higher productivity achieved by these farms reduced the land area required for a family to subsist. As a result, the INC reduced the plot size from 3.5 to 2 ha.Footnote 48 This reduction in plot size was implemented in Sector II (1961), resulting in greater land fragmentation and an increased density of settlers within the same area.

It also had a decisive influence on expanding the area suitable for irrigation. While the colonisation plans had initially determined that only 10,000 ha of the approximately 30,000 ha in the Poniente could be transformed into irrigated land, the ‘enarenado’ technique overcame this physical barrier.Footnote 49 Affordable access to water resources and the construction of this artificial soil—which guaranteed agricultural productivity—encouraged private enterprise to invest in this new sector.Footnote 50 Moreover, these new elements, combined with subsequent innovations, rapidly transformed the orientation of the traditional agriculture projected by the Francoist state in its colonisation plans, evolving into a capitalist agricultural model dedicated mainly to exports.Footnote 51

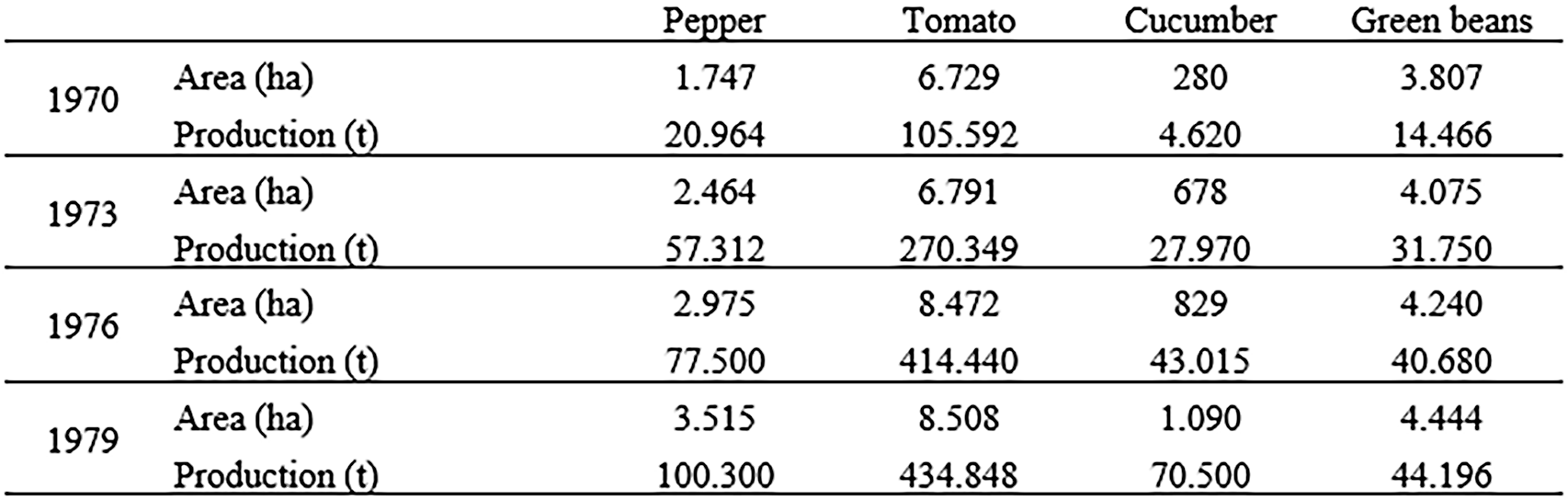

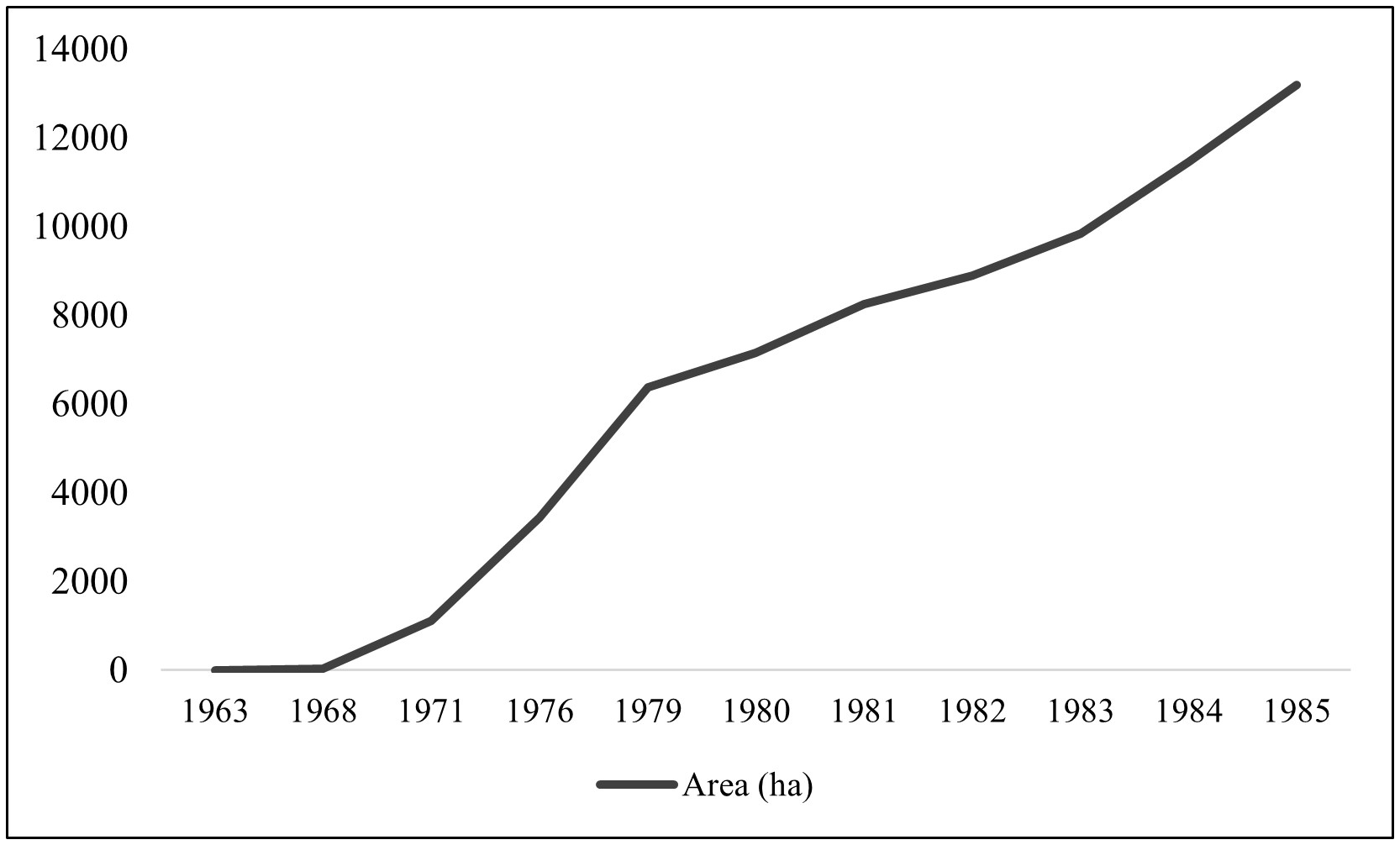

Another of the experiments carried out by the INC on the Almería coast was the introduction of plastic on farms, used both as a windbreak and to control the temperature. In this context, during the 1960s, the first greenhouses and plastic roofs for agriculture were standardised. However, the pioneers in the construction of solar greenhouses in Spain, which were mainly made of polyethylene, were the farmers of the Canary Islands. These first greenhouses were developed from 1958 onwards for growing vegetables, mainly tomatoes and cucumbers.Footnote 52 In the case of Almería, technicians tested plastic coverings on sand-mulched surfaces from 1963 onwards, building the first greenhouse in Roquetas de Mar with an area of 0.5 ha. By 1968, the INC was still testing an area of 30 ha of greenhouses, which also had the particular feature of combining new technological advances with the traditional techniques of the province (Figure 5).Footnote 53

Figure 5. Old vine arbour and Almería-style greenhouse.

Source: Author’s own (Almería Provincial Council Archives).

The cultivation of the Ohanes table grape, spanning the 19th and 20th centuries, radically transformed the province’s landscape and economy through the construction of terraces and an export model predicated on the fruit’s exceptional keeping qualities. Following decades of prosperity—punctuated by cyclical crises stemming from market saturation and wartime conflicts—the sector ultimately declined in the final third of the 20th century. This was driven by the advent of refrigerated transport, shifting consumer preferences, and rising labour costs. Nevertheless, this historical cycle bequeathed a crucial technical legacy: the trellis structures (parrales) and specific farming techniques provided the direct foundation for the transition to the current, highly profitable model of intensive agriculture under plastic.Footnote 54 Plastic sheeting was installed directly onto the structures that had previously supported grapevines, effectively securing the province’s future economic mainstay. Like sand mulching, the greenhouse offered numerous advantages. It enhanced moisture retention, minimising evaporation losses; it raised temperatures and dampened sudden diurnal thermal fluctuations; and it acted as a far more efficient windbreak than traditional cane reeds in a region characterised by persistent, strong winds. These attributes enabled Almería’s farmers to cultivate vegetables out of season, advancing and controlling the crop cycle to secure a significant commercial advantage.Footnote 55 Just as sand mulching had spread in the 1960s, the 1970s witnessed the large-scale expansion of plastic greenhouses. While only 30 ha of greenhouses existed in the province in 1968, by 1971 this figure had surged to 1,114 ha (Graph 1).Footnote 56

Graph 1. Evolution of greenhouse area in the province of Almería (1963-1985).

Source: Author’s own based on data from Gómez (1999: 63).

The third pivotal innovation on the Almería coast consolidated the agricultural model into its current form. This was the widespread adoption of localised irrigation, commonly known as ‘drip irrigation’.Footnote 57 Imported from Israel, this system enabled a significant reduction in water consumption compared to traditional flood irrigation. In 1970, the owners of the ‘Las Fresas’ farm in Vícar pioneered this system to optimise the use of scarce water resources. Although its diffusion was more gradual than that of sand mulching or greenhouses, localised irrigation gained traction during the 1970s and intensified significantly during the 1980s.Footnote 58 Beyond reduced water costs, its benefits included minimised evaporation losses and more efficient nutrient application (fertigation).Footnote 59

Beyond the reduction in water consumption and the consequent decrease in costs, the advantages were manifest. Minimising the wetted area reduced the degradation of the sand mulch caused by flood irrigation, thereby extending its lifespan and reducing the need for replacement. It also facilitated the application of fertilisers through the pipes (fertigation), thus extending the intervals between organic manure applications. Furthermore, it enabled the available water resources to irrigate a significantly larger area than originally planned.Footnote 60 The words of José Antonio Fernández, president of the Federation of Irrigators of Almería (FERAL), illustrate the significance of localised irrigation for the province: ‘If we were still irrigating by blanket irrigation, as 30% of Spain still does, instead of 30,000 hectares of greenhouses, we would have around 7,000’.Footnote 61 From 1977 onwards, the INC, which had previously channelled water through an extensive network of open ditches, began utilising pressurised pipes to supply new irrigated lands. Over the following decades, the open channel system was completely replaced.

Land prices and the property market

Both the intervention of the INC and the standardisation of technological advances had an immediate effect on land appreciation. Anticipated profits from the new farms encouraged many landowners to put their land into production as direct cultivators; however, this also triggered intense speculation and land trading.Footnote 62 Under such circumstances, land values soared as the INC increased the irrigated area. As previously noted, of the 12,387 ha that the INC brought under irrigation in the region, only 1,461 ha were distributed among colonists, while the remaining 10,926 ha were put into production by private initiative. This private sector benefited from incentives associated with the area’s designation as a zone of ‘National Interest for Colonisation’, including low-interest loans and, frequently, non-repayable grants. However, for private enterprise to transform the Almería wasteland, a fundamental actor was required: credit institutions. Both savings banks and, above all, credit cooperatives were essential for the capitalisation of the Almería sector. In this context, the creation of the Caja Rural Provincial de Almería in 1966 is particularly notable, as it became the primary credit institution for farmers from the 1970s onwards. Indeed, its growth is intrinsically linked to the expansion of the greenhouse horticulture sector on the coast.Footnote 63

The transformation of the initial sectors drove a progressive appreciation of land values, as landowners recognised the potential unlocked by access to irrigation. Beyond water access, the higher yields offered by sand mulching and, subsequently, greenhouses—coupled with the premium prices for extra-early produce in European markets—enabled numerous smallholders to establish profitable family farms. However, the Campo de Dalías had been designated a colonisation zone in 1941, and the associated decree restricted the subdivision and sale of land. These restrictions were only lifted in 1963, following the approval of the general transformation plan for Sector III. The decree’s final provisions effectively suspended the declaration of ‘National Interest’ for the colonisation of the Campo de Dalías.Footnote 64 Consequently, the removal of constraints allowed landowners to dispose of their property freely, triggering a surge in the land market from that point onwards.

In this regard, the INC paid the highest prices relative to the private sector.Footnote 65 In Sector I, prices varied depending on land quality, with prime land costing between 2,000 and 3,500 ptas/ha. By the time valuations were conducted for the transformation of Sector II, prices had already risen due to farmers’ anticipation of irrigation benefits, reaching a range of 7,500 to 17,000 ptas/ha.Footnote 66 Driven by the direct and indirect effects of the colonisation schemes, a large number of farmers transformed the formerly unproductive land in a relatively egalitarian manner, establishing the Family Agricultural Enterprise (EFA) model.Footnote 67 Consequently, the transition from dictatorship to democracy from 1975 onwards had a significant impact politically, but less so economically, as the adoption of capitalism and integration into international markets had been underway since the 1960s. Furthermore, certain Francoist institutions persisted after the arrival of democracy, as was the case with IRYDA, which was not dissolved until 1995 (Graph 2).

Graph 2. Evolution of land prices in the Poniente of Almería between 1952 and 1982.

Source: Author’s own based on data provided in: José Rivera Menéndez, op. cit.

Collective action as the backbone of agrarian consolidation

Another element revealing the success and consolidation of intensive agriculture was the farmers’ collective response to the sector’s crises. Against a backdrop of early instability, the associative network established by farmers proved to be the instrument that provided them with solid bargaining power before government bodies and monopolies. Furthermore, this associative phenomenon manifested itself through a wide range of organisations encompassing two main fronts: socio-political advocacy and economic management.

On the advocacy front, Professional Agricultural Organisations (OPAs) were decisive in the dialogue with the State to drive infrastructure modernisation and the optimisation of the productive fabric. The various OPAs not only structured agrarian protest but also acted as ‘schools of democracy’, propelling their leaders into municipal political leadership. Through assembly-based practices and constant mobilisation, farmers ceased to be passive subjects and became political actors capable of negotiating with the Administration and demanding necessary improvements in terms of commercialisation or fiscal security. Far from weakening the sector, competition between these groups energised participation, forcing each union to refine its strategies, whether through direct confrontation or institutional participation.Footnote 68

In parallel, within the economic sphere, the consolidation of intensive agriculture would have been unfeasible without commercial associativism. The creation of cooperatives, Agrarian Transformation Societies (SATs), and the grouping of exporters under organisations such as COEXPHAL, allowed the sector to overcome the fragmentation of family production and organise itself cohesively. These structures equipped the countryside with the necessary mechanisms to compete in European markets, professionalising sales and defending the sector’s interests against third-country competition and Community regulations.Footnote 69

Farmers had to incur debt to adopt the new technologies that enhanced farm productivity, while the associative framework consolidated both administrative and commercial improvements. This brought cohesion to the farming community and allowed Almería’s agriculture to transition from precariousness to a solid socio-economic model and an international benchmark. This socio-economic phenomenon left its mark on the territorial configuration, details of which were recorded in the Agrarian Censuses. Through these records, it is possible to trace how the structure of property was redefined and how irrigation was consolidated in the final decades of the century.

Agricultural censuses as a reflection of agricultural transformation and the expansion of irrigation

As the following section will demonstrate, the phenomena previously discussed were reflected in agricultural censuses and the evolution of property structure and tenure patterns during the second half of the 20th century.

The 1962 agricultural census, which coincided with the onset of INC intervention, confirms that the Poniente was already characterised by a structure of small farms, except for some large estates exceeding 100 ha. There were some 4,345 ha of farms with an area of less than 5 ha. While the number of farms between 5 and 100 ha (medium-sized holdings) was about 1,258, the majority of them—around 1,024—were smaller than 20 ha. Conversely, large holdings exceeding 100 ha numbered 61. In the latter case, the municipal territory of Dalías stood out with 25 holdings, followed by Enix and Vícar with 13 and 11, respectively.

Bearing in mind that irrigation was being introduced during the 1960s and 1970s, most holdings were still rainfed. For this year, we found that the number of farms in the region was 5,664. Generally, in the province of Almería, of the 242,068 ha cultivated, only 37,238 ha were irrigated, while uncultivated land corresponded mainly to large estates, which, on average, utilised only 11% of their total land.

As we have noted, the colonisation plans helped modify the structure of the land, fragmenting farms larger than 5 ha, and, thus, increasing the cultivated area. In the 1972 agricultural census, there were 5,802 farms of less than 5 ha, an increase of 34% over the 1962 census. Likewise, farms between 5 and 50 ha decreased by 18%, just as farms between 50 and 100 ha dropped by 19%, corroborating this downward trend. The number of holdings larger than 100 ha remained practically unchanged at 62, decreasing in Enix and Vícar, but increasing in the municipal territory of Dalías. Likewise, there was a notable increase of 21% in the number of holdings, reaching 6,879 ha this year.

While the censuses of 1962 and 1972 evidence an incipient fragmentation of land ownership, the most significant transformation occurred during the 1980s. This shift was driven by the definitive entry of private enterprise into agricultural development. Furthermore, from this decade onwards, the countryside became predominantly irrigated through INC-IRYDA interventions, which significantly facilitated the expansion of the cultivated area. As previously noted, the reduction in holding size is particularly noteworthy, resulting from both colonisation schemes and the enhanced productivity delivered by technical advances—most notably, the greenhouse (Graph 3).

Graph 3. Evolution of agricultural holdings between 1962 and 1972.

Source: Author’s own based on agricultural censuses.

The 1982 agricultural census demonstrates a clear trend towards smaller farm sizes, recording 9,844 farms of less than 5 ha. This represents a 70% increase in such holdings over the decade compared to the 1972 census. In contrast, holdings between 5 and 50 ha decreased by 50%. Regarding farms larger than 50 ha —already catalogued as large irrigated properties—only 50 remained. Notably, 12 were located in Enix and 11 in Dalías, marking a 45% reduction compared to the previous census. In total, the number of farms recorded in this census was 10,384 (Figure 6).

Figure 6. Poniente región, satellite Aerial 1977–1984.

Source: Author’s own, https://javier.jimenezshaw.com/mapas/mapas.html

In the 1989 census, holdings of less than 5 ha continued to increase, albeit at a slower rate than in the previous decade, reaching 11,670 holdings (a 25% increase). Medium-sized holdings also continued to decline, although, as with small holdings, at a much slower rate than in previous censuses, showing a 4% reduction. Large holdings generally continued to decline, with the exception of the municipal territory of Adra, where the census reports a significant increase from 9 to 34 holdings exceeding 50 ha, only to drop again in the 1999 census to 12 holdings. Consequently, this data indicates an overall increase of 24% in large holdings, contrasting with the trend recorded in previous censuses. However, if we exclude this municipal territory, we find that in the other towns of the Poniente, large estates continued to decline, decreasing by 32%. In summary, the 1989 census shows that the number of farms registered in the region increased by 2,475 to reach 12,858 (Graphs 4 and 5).

Graph 4. Evolution of farms smaller than 20 ha from 1962 to 1989.

Source: Author’s own compilation based on agricultural censuses (INE).

Graph 5. Evolution of farms larger than 20 ha from 1962 to 1989.

Source: Author’s own based on agricultural censuses.

The agricultural censuses thus reveal a clear trend towards the fragmentation of landholdings, accompanied by a particularly significant decline in the number of farms exceeding 5 hectares. This pattern, thoroughly documented in statistical records between 1962 and 1989, reflects the profound technical and structural transformations that reshaped the agricultural sector during the study period.

The tenure regime

Turning to the land tenure regime and its evolution during this period, the direct exploitation of the land increased by more than 80%, positioning the peasant farmer above other regimes in Eastern Andalusia.Footnote 70 Even in areas where large estates coexisted, the exploitation of the land was directly linked to these small peasant farmers. This type of agriculture is the pillar of family farming and the technical and social basis of these rural areas.

The case of indirect exploitation—referring to categories appearing in agricultural censuses as leasing, sharecropping, or other regimes—is governed by more complex rules.Footnote 71 For instance, these depend on the existence of large estates or the varying availability of water resources. In rainfed areas, direct cultivation tends to predominate, carried out by owner-occupiers, except where large estates are present; in such cases, land is typically parcelled out into smallholdings. Conversely, indirect exploitation tends to be more widespread in irrigated areas and for specific crop types, such as horticultural produce, even in the absence of large estates. Indirect farming is crucial not only in smallholdings within irrigated zones, such as fertile plains, but also in rainfed areas where large landholdings exist. This dynamic also depends on the minimum area a family unit requires for subsistence, which is determined by the type of cultivation practised. This subsistence threshold is achieved by renting additional plots to supplement family income or by maximising the use of family labour capacity. Regardless of the ownership structure, the farm tends to be modelled on the ideal of family tenure. Conversely, property is effectively broken up into small units as soon as its size clearly exceeds the family’s labour capacity.Footnote 72

Sharecropping constitutes another traditional form of indirect tenure worthy of particular attention, given its persistence into the 1960s. It represented a mutually advantageous arrangement for both the landowner and the sharecropper, as small farmers often preferred surrendering a portion of their harvest to paying cash rent. Moreover, these arrangements frequently became hereditary, often existing without any formal contract. This system facilitated risk-sharing, whereby both cultivation costs and harvest proceeds were typically divided equally. Notably, the province of Almería distinguished itself from other Andalusian provinces regarding this tenure type, recording 172,714 ha in the 1962 census.

Finally, the category termed ‘Other Regimes’ in the agricultural censuses comprises less common forms of tenure, although they are of particular relevance in the Poniente. These include holdings held in trust, precarious tenancy, land under litigation, emphyteusis, rabassa morta, quitrents (censos), forums (foros), or land cultivated rent-free.Footnote 73 This category also encompassed the status of INC settlers: specifically, the allocation of family plots and complementary garden plots to farmers under state tutelage through the colonisation schemes. Their legal status as concessionaires was defined as a ‘tutelage regime’ or ‘access to ownership’, meaning they could not yet be classified as full owners.Footnote 74 This classification significantly influenced the data on land tenure in agricultural censuses from 1962 onwards, revealing several subsequent trends. Consequently, it is clearly observable that between 1962 and 1989, the fundamental trend was a process of ‘proprietarisation’ regarding agricultural holdings.

A period of ‘proprietarisation’ (1962-1989)

This stage was characterised by an increase in the number of owner-occupied holdings and a steady decline in other tenure regimes. As discussed throughout this work, this shift was driven by various factors, such as state intervention schemes, which facilitated the fragmentation of large estates and enabled access to land for a significant segment of the population. Moreover, the development of the new agricultural model necessitated hyper-capitalisation, both for the construction of infrastructure and for the adaptation to new techniques and access to inputs. Consequently, there was a heavy dependence on credit institutions to provide the capital required to ensure farm viability. This substantial investment led to significant indebtedness among farmers; understandably, only landowners were willing to incur such debt in the hope of eventually paying off the improvements.Footnote 75 In contrast, tenants did not typically make such large investments because their relationship with the property was temporary, risking the inability to amortise costs. Furthermore, lending institutions required collateral—usually land and/or housing—to disburse loans; thus, ownership became a sine qua non. Finally, this process of proprietarisation was closely linked to the appreciation of land values driven by access to irrigation and the rise of greenhouses, which prompted landowners to reclaim their land for direct cultivation or speculative purposes.Footnote 76

The 1962 census provides data on land tenure confirming that this region was fundamentally characterised by owner-occupancy, which accounted for 77% of the total land, while leasehold stood at 11%, sharecropping at 8%, and other regimes at only 3%. The subsequent census confirms this trend towards proprietarisation, which increased to 89%, while leasing dropped considerably to 3% and sharecropping to 1%. However, the ‘other regimes’ category rose to 9%, largely due to the status of Institute settlers, as previously noted. The 1982 census data requires careful interpretation; although the downward trend of leasehold continued, reaching 1% of the total, sharecropping increased slightly to 2%. A notable feature of this census is the significant surge in ‘other regimes’, which continued its upward trend to reach 28% of the total land. This phenomenon corresponds to INC settlers accessing land under this specific tenure arrangement. However, approximately 20% of this group would transition to full ownership by the next census in 1989. Nevertheless, the trend of the most common regimes in Spain—leasehold and sharecropping—followed a downward trajectory until 1982, when leasehold began to increase gradually. As previously observed, in irrigated areas (Graph 6).

Graph 6. Percentage of land area by tenure type. Censuses of 1962, 1972, 1982 and 1989. Author’s own.

Source: Andalusian Institute of Statistics and Cartography.

Instead, large estates along the Almería coastline were typically subdivided and rented out due to the lack of access to irrigation, fundamentally becoming rentier estates. These large properties gradually disappeared in favour of smaller holdings, a process accelerated both by state colonisation laws and by rising land values and market dynamics.

Conclusions

Although the ownership structure had been fragmented since the Early Modern period, events from the late 19th century onwards had a decisive impact on reducing farm sizes and increasing the number of smallholders in Almeria. The progressive access to irrigation water provided by private companies facilitated an increase in the number of farms until the INC implemented comprehensive irrigation from the 1950s onwards. However, land distribution and the settlement of colonists were more modest than the Institute had originally intended. Alongside these actions, technical advances also influenced the reduction in holding sizes and enabled more farmers to access land. The higher productivity per hectare—obtained first with sand mulching and subsequently with greenhouses—considerably reduced the farm size required to support a family unit. Later, localised irrigation optimised water consumption and further expanded the irrigable area. These elements spurred private enterprise to invest early in the agricultural sector, leading to a significant rise in land prices and intense land market activity.

All this was reflected in the agricultural censuses from 1962 onwards, regarding both land ownership structure and tenure regimes. We have observed a downward trend in the number of farms larger than 5 ha and a considerable increase in the number of farms smaller than 5 ha until the 1990s. Likewise, the tenure regime between 1962 and 1989 focused mainly on proprietorship and owner-occupancy, with a reduction in indirect regimes. However, from the 1989 census onwards, the trend began to shift towards a slow but progressive increase in leasing. This was favoured by the consolidation of the sector, the ‘de-familialisation’ of the farm, and the massive introduction of migrant labour.

Ultimately, the development of the ‘Sea of Plastic’, also known as the Garden of Europe, was made possible from the 1950s onwards by a combination of public and private investment, the mass adoption of technological advances by peasant families, and significant collective action. All of this resulted in a reduction in the size of agricultural holdings required to ensure profitability, thereby creating a landscape defined by small and medium-sized farmers.

The case of Almería transcends the provincial scale, offering a model of agrarian transformation applicable to other arid regions suffering from water scarcity. In contrast to other state-led colonisation schemes that failed due to their inherent rigidity, success in this instance was rooted in hybridisation: an initial public intervention that provided essential infrastructure—specifically wells and irrigation systems—followed by the rapid adoption of technological innovations by private enterprise. This study demonstrates that land fragmentation, far from being an impediment, fostered a Family Agricultural Enterprise (EFA) model which proved more efficient than the large estates (latifundia) found in other regions, such as the model employed in the Canary Islands.

Whilst the ‘sea of plastic’ originated from an initial mistrust of the dictatorship’s policies among the most humble sectors, the ultimate economic benefit was widely distributed across the local peasantry. The establishment of a robust associative and cooperative network (such as Caja Rural or COEXPHAL), bolstered by the work of Professional Agrarian Organisations (OPAs), ensured that smallholders were not displaced by large corporations, thereby becoming the primary beneficiaries of the export boom despite the high level of financial indebtedness among families. Nevertheless, this success brought with it notable social downsides and changes: in its final consolidation phase, the model was underpinned by a growing reliance on migrant labour, thus initiating a period of defamiliarisation and a transformation towards modern agricultural entrepreneurship.