Pregnancy is a period marked by significant biological, psychological and behavioural changes that increase women’s vulnerability to a range of mental health disorders, including stress, anxiety and depression(Reference Tang, Lu and Hu1,Reference Andhavarapu, Orwa and Temmerman2) . However, the causes of stress, individual responses to it and coping mechanisms vary greatly among women. Those who are undernourished or of low socio-economic status are particularly at risk for developing mental health conditions compared with their more advantaged counterparts(Reference Ngandu, Momberg and Magan3,Reference Victora, Adair and Fall4) . Additionally, factors such as exposure to trauma, fear of childbirth and lack of social support can further exacerbate stress levels during pregnancy(Reference Andhavarapu, Orwa and Temmerman2,Reference Sara, Ryesa and Muzayyana5) .

Maternal mental disorders have been linked to a range of negative outcomes in offspring, including developmental delays, impaired attachment and difficulties with social interaction(Reference Vigod, Villegas and Dennis6). Despite the significant burden of these disorders, mental health conditions remain under-reported and undertreated in low- and middle-income countries(Reference Gelaye, Rondon and Araya7). Antenatal stress and depression are associated with an increased risk of adverse birth outcomes, including miscarriage, preterm birth, low birth weight and cesarean delivery(Reference Răchită, Strete and Suciu8). Moreover, women experiencing higher levels of perceived stress are more likely to engage in poor dietary practices and unhealthy eating behaviours, such as meal skipping, emotional eating or excessive caloric intake(Reference Sara, Ryesa and Muzayyana5).

The Coronavirus Disease 2019 (COVID-19), which first emerged in Indonesia in March 2020, disrupted many aspects of life, including food systems and healthcare services. Physical distancing and mandatory lockdown limited the access of pregnant women to social support(Reference Suárez-Rico, Estrada-Gutierrez and Sánchez-Martínez9). Social support is a multidimensional concept that includes emotional (e.g. encouragement, compassion and reassurance), instrumental (e.g. assistance with household chores, caregiving) and and informational (e.g. information exchange, problem-solving) support, and it has been considered a key indicator of women’s physical and mental well-being during pregnancy and after childbirth(Reference Żyrek, Klimek and Apanasewicz10). Maintaining good mental well-being throughout pregnancy can help lower the risk of adverse outcomes such as shorter gestational age, preterm birth, preeclampsia and neonatal morbidity, as maternal stress can otherwise compromise both maternal and fetal health and nutrition, increasing the likelihood of these complications(Reference Traylor, Johnson and Kimmel11). In addition to the pandemic, limited local job opportunities often require men to work away from their home regions. As a result, many were unable to return due to travel restrictions, leaving pregnant women feeling more isolated and unsupported during this period(Reference Nurrizka, Nurdiantami and Makkiyah12).

Evidence suggests that consuming a healthy, high-quality diet can improve mental health and mood(Reference Wu, Zhang and Li13,Reference Yelverton, Rafferty and Moore14) . During pregnancy, adherence to a healthy dietary pattern, characterised by high intake of pulses, nuts, vegetables, fruits, fish, shellfish, seafood products and dairy, has been associated with a decreased risk of depression(Reference Wu, Zhang and Li13). This also indicated increasing intake of key nutrients such as B vitamins (B1, B2, B6, B12 and folate) to help protect against depression(Reference Wu, Zhang and Li13). In addition, vitamin D, zinc (Zn), magnesium (Mg), selenium (Se), iron (Fe), calcium (Ca) and n-3 fatty acids have a significant effect on the brain and nervous system, which might influence the appearance of depressive symptoms(Reference Zielińska, Łuszczki and Dereń15).

A linear programming analysis by Fahmida et al. (2022), conducted as part of the National Monitoring of Nutrient Consumption (Pemantauan Konsumsi Gizi) across ten stunting-prioritised districts in Indonesia, identified Fe, folate and Ca as key problem nutrients among pregnant women(Reference Fahmida, Pramesthi and Kusuma16). This finding aligns with the high prevalence of anaemia during pregnancy in the region(17). Similarly, a recent systematic review found that energy and macronutrient intakes were generally below the recommended dietary allowance, with most pregnant women did not meet the estimated average requirements for vitamin D (< 70 %), vitamin E (< 50 %), water-soluble vitamins (< 80 %), as well as Ca, potassium and Fe (< 60 %)(Reference Agustina, Rianda and Lasepa18). However, adequate intakes of vitamin A, Zn and phosphorus were observed. Regarding dietary pattern, the Rhea Birth Cohort study in Greece (2007–2009) found that women adhering to a ‘health-conscious’ dietary pattern, rich in vegetables, fruits, legumes, nuts, dairy, fish and olive oil, had significantly lower Edinburgh Postnatal Depression Scale (EPDS) scores (highest v. lowest tertile: β-coefficient = −1·75, P = 0·02)(Reference Chatzi, Melaki and Sarri19).

Fe status is critically important during pregnancy due to physiological changes such as haemodilution, which can influence maternal health outcomes(Reference Calje and Skinner20). A previous study conducted among mothers in the Gaza Strip demonstrated an increased risk of postpartum depression in women with iron deficiency(Reference Hameed, Naser and Al Ghussein21). A cross-sectional study analysing data from the USA National Health and Nutrition Examination Survey 2005–2010 found that somatic symptoms of depression were more prevalent among nonpregnant women of reproductive age (20–44 years) with iron deficiency, indicated by elevated transferrin receptor levels, particularly those with low income(Reference Ciulei, Ahluwalia and McCormick22).

Limited research has been conducted in Indonesia examining the impact of maternal nutrition (both dietary intake and nutritional status) on mental health outcomes. Findings from the Indonesia Basic Health Research (2018) indicated that among pregnant women, common mental disorders (CMD) were significantly associated with first-trimester pregnancy, a history of pregnancy complications and low mid-upper arm circumference. In postpartum mothers, significant factors associated with CMD included rural residence, unwanted pregnancy, history of abortion, spontaneous delivery, pregnancy and postpartum complications, inadequate antenatal care and contraceptive use(Reference Ariasih, Budiharsana and Ronoatmodjo23). This study aims to investigate the association between determinants, including socio-demographic, anaemia, iron deficiency, pregnancy-related and dietary-related factors, with mental health outcomes (i.e. maternal stress, depression and common mental disorders) during pregnancy.

Methods

Study design and population

This cross-sectional study is a part of the observational cohort study in Indonesia entitled Action Against Stunting Hub, conducted in four rural sub-districts of East Lombok (2019–2024). The Action Against Stunting Hub study investigates interdisciplinary determinants of maternal and child nutrition, health and well-being using a ‘whole child’ approach. It conducts longitudinal assessments across pregnancy, lactation and the complementary feeding period to identify key factors influencing child growth and development. These assessments include (1) anthropometry, (2) biomarkers of nutritional and health status, (3) dietary intake, (4) fetal growth and development, (5) infant morbidity, (6) infant and young child feeding practices and (7) maternal stress, depression and social support during the perinatal period(Reference Davies-Kershaw, Fahmida and Htet24). East Lombok district was purposively selected as the study area due to its high prevalence of stunting (above 30 %)(17). East Lombok is one of the largest and most densely populated districts in the province, with an estimated total population of 1,200,612 in 2019(25). The majority of inhabitants work in agriculture, fisheries and some are involved in trading sectors(25). Of the twenty-one sub-districts, Aikmel, Lenek, Sikur and Sakra sub-districts were selected as our study area due to their high stunting prevalence (above 30 %)(17), representation of different geographic typology, e.g. mountainous and coastal regions, and access to the laboratory within 2 hours from the time of biological sample collection.

Pregnant women were recruited between February and September 2021. Eligible participants were 18–40 years old, at 16–20 weeks of gestation, of Sasak ethnicity, planning to reside in East Lombok district for the following 30 months and provided informed consent to participate. Data collection was done in the second (T2) and third (T3) trimester of pregnancy from February 2021 to January 2022.

Data collection

This study reports findings on maternal nutritional status and mental health based on data collected during the second and third trimesters of pregnancy. Pregnant women were recruited during their second trimester. We collected baseline characteristics and nutritional status of mothers during the second trimester, including socio-demographic and pregnancy characteristics. Subsequently, during the follow-up period (third trimester), pregnant women were interviewed using questionnaires to investigate the mental health status of the mothers EPDS, Global Measure of Perceived Stress (GMPS), Multidimensional Scale of Perceived Social Support (MSPSS) and Self-Reporting Questionnaire (SRQ) and had blood samples collected. Enumerators fluent in the local Sasak language, each with an educational background of at least a diploma in nutrition, were recruited and trained for electronic data capture using a tablet-based app (www.commcarehq.org). Household socio-demographic information, maternal and paternal characteristics were collected using standard questionnaires from previous studies and national surveys, including the National Socioeconomic Survey (SUSENAS)(26), Indonesian Basic Health Survey (RISKESDAS)(17) and the cohort study in East Java, Indonesia (BADUTA project)(Reference Dibley, Alam and Fahmida27).

Socio-demographic and pregnancy-related characteristics

Socio-demographic characteristics included (i) age of pregnant women and husband, (ii) education level, (iii) employment status, (iv) family size, (v) tobacco smoke exposure and (vi) wealth index. Exposure to tobacco smoke was assessed based on whether women were actively smoking during pregnancy or were exposed to environmental tobacco smoke as passive smokers. The wealth index was calculated using PCA based on variables from the 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Surveys, including housing amenities, household assets and transportation ownership.

Pregnancy-related characteristics included: (i) unplanned pregnancy, (ii) number of antenatal care (ANC) visits and (iii) consumption of Fe and folic acid supplements. Unplanned pregnancy was categorised as ‘Yes’ if the current pregnancy was unplanned or undesired and ‘No’ if it was planned and desired. The number of ANC visits was classified as adequate if the woman attended at least six visits during pregnancy and inadequate if fewer than six. The consumption of Fe and folic acid supplements was categorised as ‘Yes’ if the woman had taken the supplements in the past 30 days and ‘No’ otherwise.

Maternal stress, depression and common mental disorders

Several psychometric instruments were employed in this study to assess common mental health disorders (CMD), stress, depression and the level of social support among pregnant women. These instruments are widely used and have been validated in Indonesia(Reference Hutauruk28,Reference Prasetio, Triwahyuni and Prathama29) . The SRQ is a twenty-item scale developed by the WHO to measure symptoms of CMD(Reference Beusenberg and Orley30). This screening test has been validated for use during pregnancy and is widely applied in various settings, including the Indonesian National Health Survey(Reference Idaiani, Mubasyiroh and Suryaputri31). The tool measures both psychological symptoms (items 4, 6, 8 and 9–17), such as feeling unhappy, frightened, worthless and low-energy, as well as common physical/somatic symptoms associated with anxiety and depression (items 1–3, 5, 7 and 18–20), such as headaches, sleep problems, low appetite and poor digestion(Reference Sanfilippo, Glover and Cornelius32). A higher score of SRQ denotes higher levels of symptoms, which was converted into a binary variable where 1 = equal or greater than six ‘yes’ answers and 0 = less than six ‘yes’ answers(Reference Idaiani, Mubasyiroh and Suryaputri31).

The second instrument, the GMPS, also known as Perceived Stress Scale, was used to determine maternal stress during the second trimester of pregnancy. Each item has a rating on a five-point Likert scale, where 0 represents ‘never’ and 4 represents ‘very often.’ The scale is clustered into two subscales, which are the positive subscale (items nos. 4, 5, 6, 7, 9, 10 and 13) and the negative subscale (items nos. 1, 2, 3, 8, 11, 12 and 14). The negative subscale, which comprises negatively stated items, is intended to assess a lack of control and negative reactions (perceived distress). The positive subscale measures the ability of individuals to cope with current stressors (coping capacity)(Reference Huang, Wang and Wang33). Seven positive items were reverse-coded (e.g. 0 = 4, 1 = 3, 2 = 2 and 3 = 1, 4 = 0). The total score was calculated by summing the scores of all fourteen items, with a higher score indicating higher perceived stress. Scores ranging from 0–18 were classified as low stress, 19–37 as moderate stress and 38–56 as high stress, based on the categorisation established by Higgins(Reference Higgins34). In this study, maternal stress was categorised as low stress (score 0–18) and moderate to high stress (score 19–56). Previous research reported that the Perceived Stress Scale demonstrated good internal consistency (Cronbach’s α > 0·70) and test-retest reliability (> 0·70) for measuring stress among pregnant women(Reference Santiago, Roberts and Smithers35).

The third instrument, the EPDS, is a validated self-reported instrument comprising ten items. Each item is rated on a four-point Likert scale ranging from 0 (‘No, not at all/never’) to 3 (‘Yes, most of the time’)(Reference Cox, Holden and Sagovsky36). The total EPDS score ranges from 0 to 30, with higher scores indicating greater severity of depressive symptoms. The instrument demonstrated strong reliability and validity, with a Cronbach’s α of 0·86 and an AUC of 0·73(Reference Joshi, Lyngdoh and Shidhaye37). It has been widely used as a screening tool for antenatal depression. In this study, the prevalence of antenatal maternal depression during the second trimester was estimated using a cut-off score of 9 out of a maximum of 30. The scores were then dichotomised into a binary variable, where 1 indicated a score greater than 9 (indicating depression) and 0 indicated a score of 9 or less(Reference Røysted-Solås, Hinderaker and Ubesekara38).

Social support

Social support of pregnant women was measured using the MSPSS. There are three subscales: (a) family: items 3, 4, 8, 11; (b) friends: items 6, 7, 9 and 12 and (c) significant other: items 1, 2, 5 and 10, each of which addresses a different source of support. Each item was scored on a seven-point Likert scale (1 = ‘very strongly disagree’ to 7 = ‘very strongly agree’)(Reference Wang, Wan and Huang39). The overall score was calculated by summing all twelve items, and the complete score ranges from 12 to 84. The score was then divided by 12 and categorised into a binary variable: 0 = high support (scores > 5) and 1 = low to moderate support (scores ≤ 5)(Reference Zimet, Dahlem and Zimet40). This instrument demonstrated excellent internal consistency, with a Cronbach’s α of 0·93(Reference Sharif, Zaidi and Waqas41).

Biomarkers

Maternal venous blood samples were collected by phlebotomists during the third trimester to assess Hb level and Fe status (measured by ferritin concentration). Since plasma ferritin levels can be affected by inflammatory processes, not accounting for this may result in inaccurate estimates of true Fe status(Reference Grant, Wanjala and Low42). Therefore, acute-phase proteins, i.e., C-reactive protein (CRP) and α-1-acid glycoprotein (AGP)(Reference Thurnham, McCabe and Northrop-Clewes43), were also measured to adjust ferritin levels accordingly. The ferritin adjustment was performed following the standard methods recommended by the WHO(44).

Blood samples were transported from study sites to the laboratory of Universitas Mataram Hospital for processing and Hb measurement. Subsequent analyses of Fe status and inflammatory markers were conducted at the SEAMEO RECFON laboratory using the Q-Plex Human Micronutrient 7-Plex ELISA assay (Quansys Biosciences). Subclinical inflammation was defined by CRP > 5 mg/l and AGP > 1 g/l(Reference Andersen, Tadesse and Bromage45). The cut-off for ferritin < 12 μg/l was used to determine iron deficiency (ID), and Hb < 11 g/dl to determine anaemia during the third trimester of pregnancy(46). Serum ferritin levels were adjusted for inflammation using the BRINDA approach(Reference Namaste, Rohner and Huang47). Iron deficiency anaemia was defined as having both an adjusted ferritin level < 12 μg/l and Hb < 11·0 g/dl(46).

Dietary assessment

Dietary data were collected from pregnant women during the second trimester using the 24-h dietary recall with a four-pass multistage interviewing technique(Reference Namaste, Rohner and Huang47). The four-pass 24-hour dietary recall consisted of: (1) recalling and listing all foods and beverages consumed the previous day; (2) collecting details on ingredients, cooking methods, composite foods and any other relevant information; (3) estimating portion sizes using food weighing and/or a food photobook and (4) verifying the recalled foods for completeness(Reference Gibson and Ferguson48).

To estimate portion sizes, trained enumerators followed a strict protocol that involved either weighing equivalent amounts of foods consumed or using a food photobook to approximate the portion sizes reported by mothers for the previous day. This approach aimed to improve accuracy while differing from the weighed food record method, which involves real-time weighing of foods as they are consumed. Weighing is one of several portion size estimation methods used in 24-h dietary recalls. Other portion size estimation methods included asking respondents to estimate portion of food samples, using food photographs and household measurement units(Reference Vossenaar, Lubowa and Hotz49).

Enumerators brought food samples such as rice, noodles and bread or used foods available in the household. Respondents were asked to estimate the amounts of food and beverage consumed, after which the enumerators weighed the actual foods using a Tanita digital scale (model KD-160, precision ±1 g; Tanita Corporation, www.tanita.com). The food photobook, adapted from the 2014 Indonesian ‘Total Diet Study’ and modified to include locally typical foods, displayed gram weight equivalents for portion sizes alongside common kitchen utensils (e.g. tablespoon, cup and bowl) for reference(Reference Htet, Fahmida and Do50). These methods were employed to minimise bias from over- or under-reporting.

Minimum dietary diversity for women (MDD-W) was calculated using the dietary data. The ten MDD-W food groups, including (1) starchy staples (e.g. grains, white roots, tubers and plantations); (2) pulses (beans and peas); (3) nuts and seeds; (4) milk and dairy products; (5) meat, fish and poultry; (6) eggs; (7) dark green leafy vegetables; (8) vitamin A-rich fruits and vegetables; (9) other vegetables and (10) other fruits. Women received a score of 1 if they consumed at least 15 grams of food from each food group; otherwise, they received a score of 0. The dietary diversity score was calculated by adding all food group values, which were then converted into the binary MDD-W, where 0 = inadequate (< 5 food groups per day) or 1 = adequate (≥ 5 food groups per day)(51).

Dietary pattern analysis was based on the original ten food groups defined by the FAO MDD-W. To identify different dietary patterns potentially associated with mental health outcomes, a more detailed classification was applied. Categories previously grouped together, such as meat, fish and poultry, were separated into three distinct groups. Additional food groups were included: (i) oils and fats, (ii) sweet foods, (iii) sugar-sweetened beverages, (iv) condiments, herbs and spices and (v) other beverages(51), resulting in a total of eighteen food groups for analysis.

Anthropometry measurement

Mid-upper arm circumference (MUAC) was used as a proxy to determine maternal nutritional status. MUAC was measured by trained enumerators, on the upper left arm, using a flexible and non-stretchable tape (SECA 201), positioned at the marked midpoint between the olecranon and acromion processes and measured to the nearest 0·1 cm(52). Throughout the study period, all anthropometric instruments were calibrated regularly in accordance with the user’s manual. MUAC tape calibration was performed using a 30 cm stainless-steel ruler to ensure measurement accuracy and consistency. Chronic energy deficiency (CED) was defined as MUAC < 23·5 cm, while values > 23·5 cm were classified as normal nutritional status(17).

Ethical approval

The Action Against Stunting Hub Indonesia birth cohort study was conducted in accordance with the ethical principles outlined in the Declaration of Helsinki (2013). Ethical approval was obtained from the Institutional Ethics Committee of the London School of Hygiene and Tropical Medicine (Reference: 17915/RR/17513) and the Health Research Ethics Committee of the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Indonesia–Cipto Mangunkusumo Hospital (FKUI-RSCM) (Reference Number: ND-914/UN2.F1/ETIK/PPM.00.02/2021). All participants provided written informed consent prior to enrollment. For those unable to sign, a witnessed thumbprint was obtained. Only pregnant women aged 18 years or older were eligible for recruitment, ensuring that minors were not included and that parental or guardian consent was not required.

Prior to data collection, trained enumerators clearly explained the study’s objectives and procedures. Informed consent was obtained from participants who agreed to take part. Participants were assured of the confidentiality and anonymity of their data, which were coded and used exclusively for research purposes. They were also informed that participation was entirely voluntary and that they could withdraw from the study at any time without any consequence.

Data analyses

Descriptive results for categorical variables, such as socio-economic and maternal characteristics, were presented as frequencies with corresponding percentages. Dietary patterns were derived from eighteen food groups using PCA, with varimax rotation applied to achieve orthogonal (uncorrelated) factors. Food groups with absolute factor loadings ≥ 0·20 were considered to have strong associations with a given pattern and were used to define and label each dietary pattern(Reference Steenweg-de Graaff, Tiemeier and Steegers-Theunissen53). The number of retained factors was determined based on eigenvalues (> 1·0), scree plot inspection and interpretability. The suitability of the dietary data for factor analysis was assessed using the Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin measure and Bartlett’s test of sphericity. The Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin value was 0·536, and Bartlett’s test yielded a P value < 0·001, indicating that the data were appropriate for factor analysis (acceptable criteria: Kaiser–Meyer–Olkin > 0·50 and P < 0·05). Five major dietary patterns with eigenvalues > 1·0 were identified, collectively explaining 19 % of the total variance in dietary intake. Adherence to each dietary pattern was categorised into quartiles: quartile 1 (low intake), quartile 2 (low-medium), quartile 3 (medium-high) and quartile 4 (high intake). For multivariable analysis, Q1 and Q2 were grouped as low adherence, while Q3 and Q4 were categorised as high adherence.

The PCA was also used to estimate the wealth index of study participants. The analysis used variables similar to those included in the 2017 Indonesia Demographic and Health Surveys(54), such as housing quality (materials used for floors, walls and roofs), source of drinking water, type of cooking fuel, type of toilet facility, ownership of durable assets (e.g. television, refrigerator, bicycle, motorcycle and car) and other wealth-related indicators (e.g. ownership of a house, land or livestock). These variables served as explanatory inputs for the PCA. The overall wealth index score was categorised by tertile for analysis, where 1 = lowest wealth and 3 = highest wealth.

The χ 2 test was used to assess associations between categorical variables. Multiple logistic regression analyses were conducted to identify factors associated with maternal stress, depression and common mental disorders. Variables with a P value < 0·20 in bivariable analysis were retained for inclusion in the multivariable models(Reference Mickey and Greenland55). To avoid multicollinearity, highly intercorrelated variables were not included together; instead, variables with strong associations with the outcomes and/or those recognised as underlying risk factors for maternal mental health were prioritised. Statistical significance was set at P < 0·05. All analyses were performed using Stata version 16·0 (StataCorp).

Results

Among the 724 pregnant women who met the eligibility criteria twenty-two declined to participate, resulting in a final sample size of 702 women (participation rate of 96.9 %). Complete data for the second trimester were obtained from all 702 participants. By the third trimester, the sample size decreased to 659 due to moving residence, miscarriage, molar pregnancy, maternal death or withdrawal from the study. Baseline characteristics of pregnant women, including nutritional status, socio-demographic and pregnancy-related characteristics, are presented in Table 1. The mean age of women was 28 years. Over half had completed secondary education (8–12 years), and the majority were housewives. Most fathers had attained secondary education (50·2 %) and were employed (98·3 %). More than 60 % of households consisted of 3–5 family members. None of the pregnant women were active smokers; however, a large majority (79·8 %) were exposed to secondhand tobacco smoke. Some pregnancies were unplanned, and nearly one-fifth (19·6 %) had fewer than six ANC visits. Additionally, 16·9 % did not consume Fe-folic acid supplements during pregnancy. Almost half (48·6 %) of the participants reported not receiving government assistance in the past 12 months. Approximately one-quarter of the women had inadequate dietary diversity, as defined by failing to achieve the MDD-W of consuming fewer than five of the ten food groups per day.

Table 1. Baseline characteristics of pregnant women in rural areas of East Lombok, Indonesia

T2, Trimester 2; T3, Trimester 3; ANC, Antenatal care; CED, Chronic energy deficiency; ID, Iron deficiency; ID, Iron deficiency anemia.

Cut-off for CED: MUAC < 23·5 cm; Anemia at T3: Hb < 11 g/dl; ID: ferritin < 15 mcg/l† or ferritin < 12 mcg/l‡; IDA: anemia and ferritin < 12 mcg/l; Low-grade (systemic) inflammation: CRP > 5 mg/l; Chronic inflammation: AGP > 1 g/l.

* Number of subjects for each variable, T2:702, T3:659.

Antenatal stress was reported by a majority of pregnant women, with 86·3 % perceiving elevated stress levels. Depression was identified in 26·5 % of women during the second trimester (T2), while 29·7 % experienced CMD in the third trimester (T3). Regarding social support, approximately 34·8 % of participants perceived low to moderate levels during pregnancy (T2). The proportion of women with CED was 22·5 % and 14·7 % at T2 and T3, respectively. The prevalence of anaemia was high (> 40 %), and one-third of the pregnant women had iron deficiency anaemia.

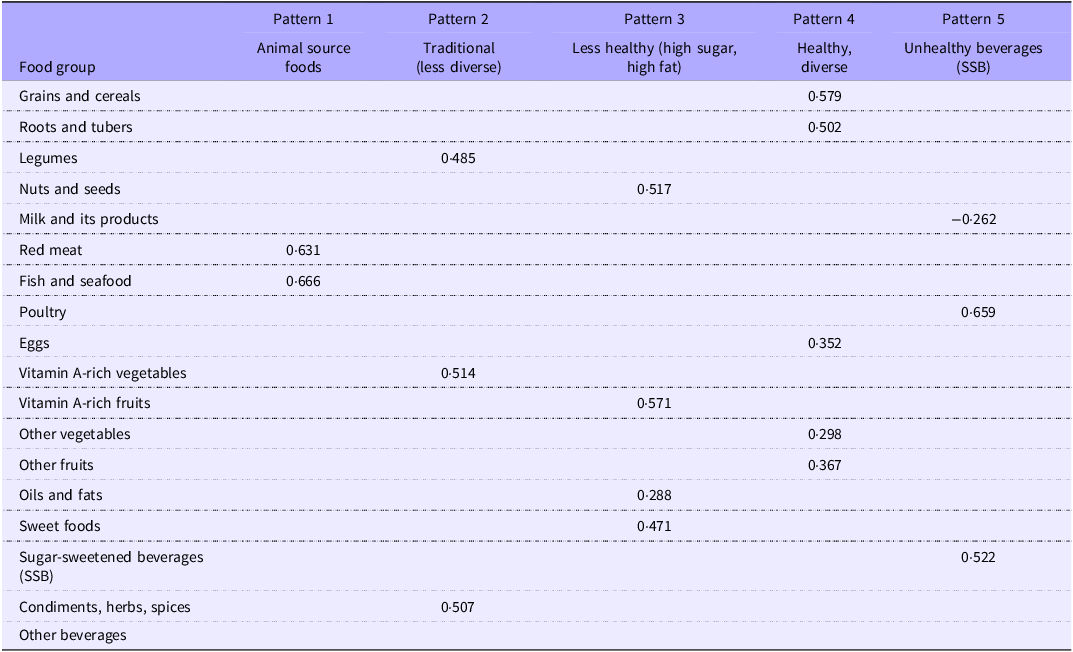

Table 2 presents the dietary pattern of pregnant women along with their corresponding factor loadings. Five major dietary patterns were identified including Pattern 1: animal source foods, Pattern 2: traditional (less diverse), Pattern 3: less healthy (high sugar, high fat), Pattern 4: Healthy and diverse and Pattern 5: unhealthy beverages (high consumption of sugar-sweetened beverages).

Table 2. Dietary patterns of pregnant women and factor loadings using principal component analysis

Items with factor loadings ≥ |0·2| are presented in the table.

The first dietary pattern was characterised by a high intake of animal-source foods, including fish (e.g. skipjack tuna and freshwater fish), seafood and beef. The second pattern reflected a predominantly plant-based diet, marked by high consumption of vitamin A-rich vegetables (e.g. spinach, water spinach, moringa leaves, cassava leaves, carrots), legumes (e.g. tempeh, tofu, pigeon peas, soybeans) and a variety of condiments, herbs and spices (e.g. garlic, shallots, onions and chili peppers). The third pattern was distinguished by a high intake of vitamin A-rich fruits (e.g. mangoes, papayas), nuts and seeds (e.g. peanuts), as well as sweet foods (e.g. foods or dishes made with white or palm sugar, jelly, wafers) and fats/oils. This included fried foods and spicy dishes prepared with coconut milk, grated coconut or peanut-based sauces, which are commonly consumed as part of the traditional diet in East Lombok. The fourth pattern represented a healthy and diverse diet, comprising grains and cereals (e.g. rice, bread, cakes, tapioca crackers), tubers and roots (e.g. cassava, sweet potatoes), eggs (e.g. chicken and quail eggs), a variety of other vegetables (e.g. tomatoes, yard-long beans, eggplants, bean sprouts) and other fruits (e.g. dates, oranges, apples and bananas). The fifth pattern was characterised by high consumption of unhealthy beverages (e.g. iced drinks with sweetened condensed milk, coffee drinks, artificially flavored juices), high intake of poultry (particularly fried chicken) and low consumption of milk and dairy products, including formula milk intended for pregnant women.

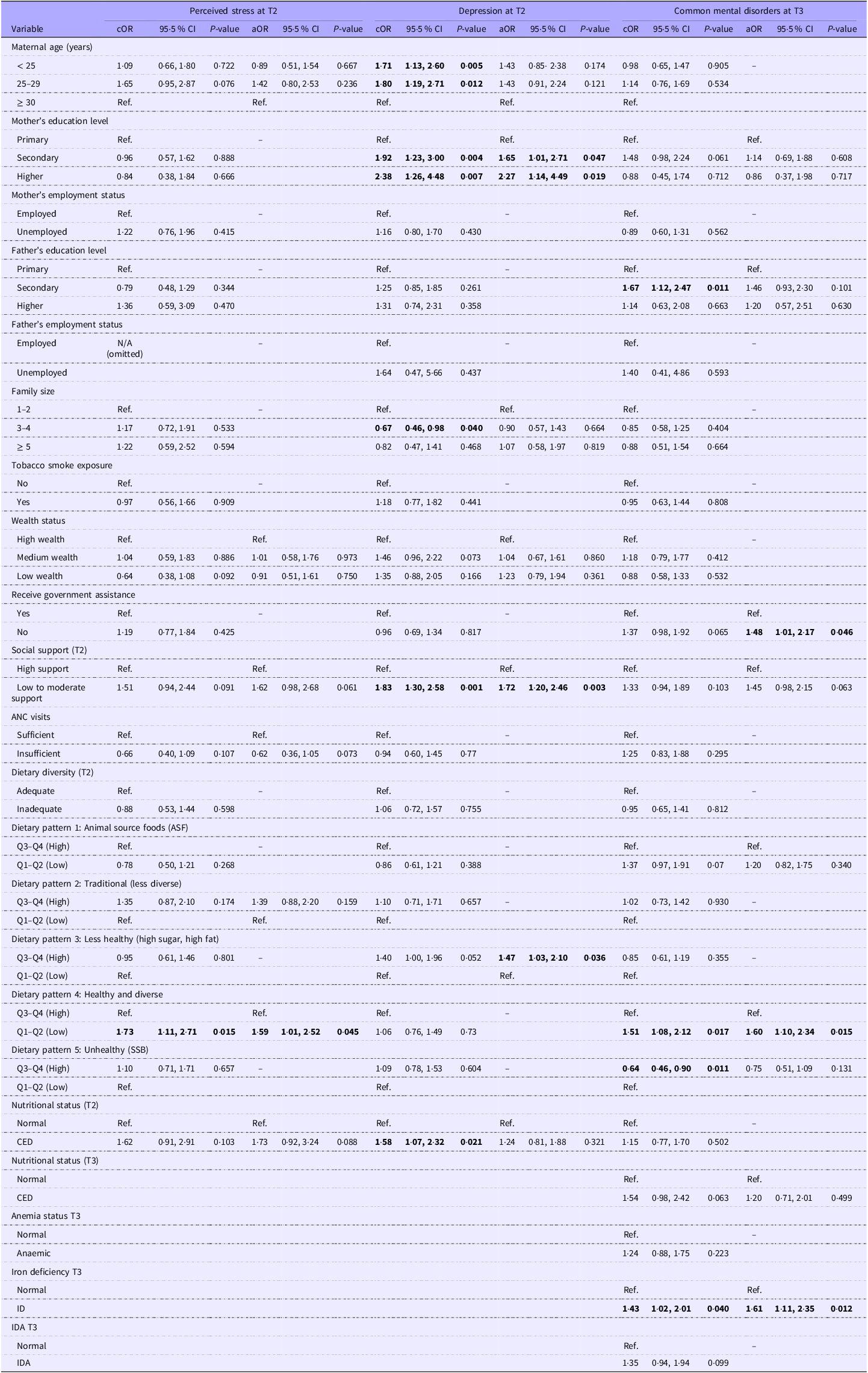

Table 3 presents the results of multivariable logistic regression analyses examining the associations between socio-demographic, pregnancy-related and dietary factors with stress, depression and CMD among pregnant women in East Lombok, Indonesia. After adjusting for covariates, low adherence to dietary Pattern 4 (healthy and diverse) was significantly associated with increased odds of antenatal stress at T2 (aOR 1·59, 95 % CI 1·01, 2·52). In addition, maternal undernutrition or chronic energy deficiency (CED, aOR 1·73, 95 % CI 0·92, 3·24) and low to moderate support (aOR 1·62, 95 % CI 0·98, 2·68) demonstrated marginal associations with antenatal stress.

Table 3. Determinants of maternal depression, stress and common mental disorders in pregnancy

ANC, Antenatal care; CED, Chronic energy deficiency; cOR, crude odd ratio; aOR, adjusted odd ratio; T2, trimester 2; T3, trimester 3; Ref., reference; Q, quartiles; SSB, sugar-sweetened beverages; ID, iron deficiency, IDA, iron deficiency anaemia.

The bold ones are the variables that have p-value <0.05 that indicates a significant association.

* Statistical analysis was performed using logistic regression. Variables with a P value < 0·2 in the bivariable analysis were included in the multivariable model.

Bivariable analysis showed that the likelihood of antenatal depression during the second trimester (T2) was higher among women with CED (cOR 1·58, 95 % CI 1·07, 2·32), young age i.e. 18–25 years (cOR 1·71, 95 % CI 1·13, 2·60), women with higher educational attainment (cOR 2·38, 95 % CI 1·26, 4·48) and those reporting low to moderate levels of social support (cOR 1·83, 95 % CI 1·30, 2·58). Conversely, women living in households with 3–4 members (cOR 0·67, 95 % CI 0·46, 0·98) were less likely to experience depression. In the multivariable analysis, significant determinants of antenatal depression included higher maternal education (aOR 2·27, 95 % CI 1·14, 4·49), low to moderate social support (aOR 1·72, 95 % CI 1·20, 2·46) and high adherence to dietary Pattern 3, characterised as a less healthy diet high in sugar and fat, which was associated with increased odds of depression (aOR 1·47, 95 % CI 1·03, 2·10).

Multivariable logistic regression analysis showed that pregnant women with iron deficiency (aOR 1·61, 95 % CI 1·11, 2·35), those who did not receive government assistance (aOR 1·48, 95 % CI 1·01, 2·17) and those with low adherence to a healthy and diverse dietary pattern (Pattern 4) (aOR 1·60, 95 % CI 1·10, 2·34) were at significantly higher risk of CMD during the third trimester.

Discussion

In this study, the majority of pregnant women (over 86 %) reported perceived stress, and approximately 30 % experienced antenatal depression and CMD. Nutritional factors associated with increased risks of stress and CMD were low adherence to a healthy and diverse dietary pattern, as well as iron deficiency (for CMD only). In contrast, antenatal depression was more strongly associated with non-nutritional factors, including low social support and higher maternal education.

Our findings are consistent with those of a study conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, which reported stress and depression in 70 % and 31 % of pregnant women, respectively(Reference Yan, Ding and Guo56). These prevalence rates are notably higher than those observed under non-pandemic conditions, as shown in cross-sectional studies from Indonesia and China, where the proportions of maternal stress and depression were 55·6 % and 29·6 %, respectively(Reference Ayu, Rachmawati and Ungsianik57,Reference Chen, Cross and Plummer58) . The lockdowns, physical distancing and other containment measures implemented during the pandemic have been associated with an increased risk of psychological distress among women, due to psychosocial stressors such as fear of illness, social isolation and economic uncertainty(Reference Ladekarl, Olsen and Winckler59). Moreover, disruptions in healthcare systems may have limited pregnant women’s access to ANC, resulting in inadequate counseling on health and nutrition, as well as reduced emotional support, factors that are crucial for both maternal mental well-being and the health of the baby(Reference Nguyen, Sununtnasuk and Pant60).

Limited access to ANC exacerbates existing health challenges, such as iron deficiency during pregnancy, which remains a significant public health issue in low- and middle-income countries(Reference Tan, He and Qi61,Reference Abd Rahman, Idris and Isa62) . Iron deficiency has been shown to significantly influence the development and management of depression(Reference Dama, Van Lieshout and Mattina63). Although no association was found between iron deficiency and depression in our study, it was identified as a risk factor for CMDin the third trimester. Pregnant women with iron deficiency had a 1·6-fold increased risk of developing CMD, suggesting its involvement in physiological processes affecting mental health(Reference Shayganfard64). Previous studies have indicated that low Fe levels may cause hypomyelination of neurons, impairing the production and release of neurotransmitters such as dopamine and serotonin, which are essential in the pathophysiology of depression(Reference Lee, Chao and Huang65,Reference Tandon, Jain and Malhotra66) . Iron deficiency, the leading cause of anaemia in low- and middle-income countries, especially during pregnancy, necessitates the inclusion of standard health education messages during ANC visits that encourage pregnant women to consume Fe-rich foods and take Fe-containing supplements.

In the bivariable analysis, women suffering from CED were 1·58 times more likely to experience depression during pregnancy. This finding is consistent with a cross-sectional study conducted in Kenya, which reported a positive association between poor nutritional status (MUAC < 23 cm) and maternal depression(Reference Madeghe, Kogi-Makau and Ngala67). These findings suggest that inadequate diet quality during pregnancy contributes to poor nutritional status, which in turn increases the risk of maternal depression.

A diverse diet is essential for supporting both physical and mental health. A systematic review by Głabska et al. found that a high intake of fruits and vegetables, particularly subgroups such as berries, citrus and green leafy vegetables, may reduce psychological distress and protect against depressive symptoms(Reference Głąbska, Guzek and Groele68). Additionally, study shows that consuming a nutritionally adequate diet is associated with improved mental health outcomes(Reference Matsuura, Saito and Takahashi69). Thus, low adherence to a healthy and diverse diet, comprising ASF (particularly eggs), grains/tubers, fruits and vegetables, was associated with an increased risk of CMD and stress in this study. Conversely, pregnant women with high adherence to a diet high in sugar and fat were more likely to experience depression (aOR 1·47).

Our findings align with a recent systematic review by Khaled et al., which reported a significant association between stress and unhealthy dietary patterns, characterised by high intake of fat, salt and fast food, alongside low intake of fish, vegetables, fruits and unsaturated fats(Reference Khaled, Tsofliou and Hundley70). Similarly, a study conducted among Japanese women found that low intake of eggs and vegetables had a significantly higher likelihood of experiencing depression(Reference Kitabayashi, Umetsu and Suzuki71). Egg yolks and dark green leafy vegetables are rich sources of methyl donor nutrients, including folate, riboflavin, vitamin B6, vitamin B12, methionine, betaine and choline(Reference Shaheen, Nowar and Islam72,Reference Zahidi, Abbasi and Surkan73) . These nutrients are essential for brain function and neurotransmitter regulation (particularly dopamine, serotonin and norepinephrine). Deficiencies in methyl donors can disrupt one-carbon metabolism and methylation processes, thereby contributing to the development of depressive disorders(Reference Madeghe, Kogi-Makau and Ngala67,Reference García-Montero, Ortega and Alvarez-Mon74) . These findings underscore the importance of promoting dietary diversity during pregnancy as part of nutrition education messages to support maternal mental health.

The relationship between dietary intake and maternal mental health may be reciprocal: poor mental health can lead to a poor diet, including low dietary diversity, while a good diet can promote more positive emotions and improved mental well-being(Reference Głąbska, Guzek and Groele68). During pregnancy, it is recommended to consume at least 2–3 portions of ASF and 4–5 portions of fruits and vegetables daily, consistent with the Indonesian balanced dietary guidelines(75).

In our study, pregnant women who did not receive government assistance (whether through cash transfers or food aid) had a 1·48 times higher risk of developing CMD during the third trimester. Since 2007, the Indonesian government has implemented the conditional cash transfer program, Program Keluarga Harapan (PKH), which supports impoverished families with pregnant women and/or young children. Additionally, the Bantuan Pangan Non Tunai (BPNT) provides food aid, including rice, eggs, poultry, meat and vegetables. These programmes play a crucial role in protecting women from lower socio-economic backgrounds, particularly during the pandemic, by improving their access to diverse and nutritious diets(76).

We found that the risk of antenatal depression increased approximately 2·4-fold among women with higher education (college level or above). This finding aligns with previous studies conducted before the pandemic, which reported that women with higher education were more likely to experience antenatal depression compared with those with lower education levels(Reference Chen, Cross and Plummer58,Reference Di Florio, Putnam and Altemus77) . Di Florio et al. further observed that women with higher education levels are more prone to self-harm, excessive crying and irrational worries(Reference Di Florio, Putnam and Altemus77). A plausible explanation is that women with higher education tend to have greater access to various media sources (e.g. television, social media and newspapers), exposing them to extensive health information about health knowledge and making them more attentive to their mental health(Reference Chen, Cross and Plummer58).

Social support emerged as a significant factor influencing mental health in this study. Low levels of social support were strongly associated with an increased risk of antenatal depression, consistent with findings from a previous cohort study in China(Reference Tang, Lu and Hu1). Adequate social support has been shown to buffer against stress by attenuating physiological stress responses, including reductions in sympathetic nervous system activation, hypothalamic–pituitary–adrenal axis activity and inflammatory reactivity(Reference Pao, Guintivano and Santos78). This study was conducted during the COVID-19 pandemic, a period during which many women may have experienced heightened isolation, particularly those lacking support from partners, family members or other relatives. Mothers of young children who received assistance with household tasks and newborn care had a significantly lower risk of depression compared with those who experienced disruptions in support system during the pandemic(Reference Gildner, Uwizeye and Milner79).

Strengths and limitations

One of the key strengths of this study is its longitudinal design, as part of the Action Against Stunting Hub Indonesia project, which allowed for comprehensive data collection from pregnant women over time. Direct interaction with participants through door-to-door visits helped minimise attrition and maintain data quality, while adhering to social distancing protocols during the COVID-19 pandemic. The cohort achieved a high participation rate (96.9%) and adhered to standardised operational procedures throughout the data collection process, resulting in a robust dataset and enhancing the reliability of our findings. To our knowledge, this is the first study in Indonesia to assess maternal mental health using three validated mental health scales among pregnant women. The use of standardised, validated instruments further strengthens the reliability and validity of the data collected. However, several limitations should be acknowledged. Due to the observational nature of the study, causal inferences between the determinants of maternal stress and depression cannot be established. Additionally, since data collection took place during the COVID-19 pandemic, the findings may not fully reflect experiences during non-pandemic conditions.

Conclusions

Our findings indicate that a substantial proportion of pregnant women experienced perceived stress, depression and CMD and underscore the importance of preventing iron deficiency and promoting healthy, diverse diets as strategies to reduce the risk of psychological distress during pregnancy. Nutrition-specific interventions, including dietary diversification, food-based recommendations and Fe-folate supplementation, are essential during this critical period and may have positive effects on both the mental and physical well-being of pregnant women. In addition, our results highlight the critical role of social support in mitigating the risk of depression and mental disorders during pregnancy, which can have adverse implications for child development(Reference Ladekarl, Olsen and Winckler59). Integrated approaches that combine nutrition-specific interventions, government assistance for economically disadvantaged households and enhanced social support from family, friends and the community are recommended to improve maternal mental health during pregnancy.

Acknowledgments

We extend our sincere gratitude to the Faculty of Medicine, Universitas Mataram (UNRAM) and Universitas Mataram Hospital for their partnership in conducting the laboratory analyses. We are especially grateful to all study participants, village midwives, health cadres, enumerators, field officers and field supervisors for their valuable contributions to this study. Our appreciation also goes to the local government of East Lombok for their support and permission to carry out this research.

The authors thank the South East Asian Ministers of Education Organization Regional Centre for Food and Nutrition (SEAMEO RECFON) for funding the publication of this article. This study was funded by the United Kingdom Research and Innovation Global Challenges Research Fund (UKRI CGRF, grant number MR/S01313X/1).

The author’s contribution were as follows: U. F. and M. K. H. contributed to conceptualisation, analysing and interpreting the data, writing – the draft manuscript and writing – reviewing and editing the manuscript. A. S. A. contributed to analysing the data, writing – the draft manuscript and writing – reviewing and editing the manuscript. T. C. A. contributed to analysing the data and writing – reviewing and editing the manuscript. R. K., H. D-K., E. F. contributed to writing – reviewing and editing the manuscript. All listed authors reviewed and approved the final version of the manuscript.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.