1. Introduction

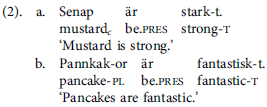

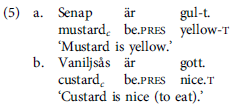

In Swedish, as in Norwegian and Danish, a predicative adjective agrees with the subject in gender and number. Footnote 1 Footnote 2 With the common gender noun senap ‘mustard’ as head of the subject noun phrase, the adjective thus has the singular common gender form, (1a), and with the plural noun pannkakor ‘pancakes’, the adjective has the plural form, (1b):

In all three languages, it is also the case, however, that when the subject is a bare indefinite noun phrase, as in (2), the predicative adjective typically does not appear with the expected gender or number marking, but takes the t-ending otherwise associated with neuter gender:Footnote 3

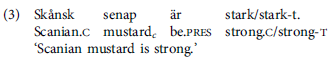

Sentences like those in (2) are known as pancake constructions (henceforth pcs)Footnote 4 and have been discussed widely in the literature since Beckman (Reference Beckman1904); for different approaches, see e.g. Wellander (Reference Wellander1949, Reference Wellander1955), Widmark (Reference Widmark1966), Faarlund (Reference Faarlund1977), Malmgren (Reference Malmgren1984), Källström (Reference Källström1993), Teleman et al. (Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999), Enger (Reference Enger2004), Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2006, Reference Josefsson2009, Reference Josefsson2014a,b, in preparation), Haugen & Enger (Reference Haugen and Enger2014, Reference Haugen and Enger2019), and Åkerblom (Reference Åkerblom2020). Although the analyses of pcs differ, the consensus seems to be that there is agreement rather than ‘disagreement’ in pcs, and the issue is rather what kind of agreement it is (see Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2014:173). The focus in previous studies of pcs has mostly been theoretical. In this article, we contribute empirical data from an acceptability study, a production study, and a corpus study. In all three studies, we look at pcs with subjects in the singular, as in (2a). The results from the three studies are discussed in relation to the predictions that fall out from two of the theoretical approaches to pcs: the semantic approach in Enger (Reference Enger2004) (see also Enger Reference Enger2013, Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2014, Reference Haugen and Enger2019) and the syntactic approach in Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2006, Reference Josefsson2009, Reference Josefsson2014a,b, in preparation). These approaches differ both in what kind of mechanism is assumed for t-agreement and in what is predicted regarding agreement marking in pcs with a modified subject, as in (3):

While pre-modification of the subject has been identified as a factor that can affect agreement preferences, the form of the verbal predicate has not been discussed much in the literature. We had the intuition that the presence of a modal verb could affect agreement preferences in pcs and wanted to investigate whether this was indeed the case:

To the best of our knowledge, modality has not previously been mentioned in the literature on pcs (but see Enger Reference Enger2004 for discussion of restrictions on the verb). In order to find out whether modality plays any role for agreement patterns, we thus included it in our studies.

The aim of the three studies that we conducted was to shed some light on the empirical question of what agreement marking native speakers of Swedish accept and produce in different types of pc, and to see to what extent the empirical data is explained by the two approaches to pcs.

2. Properties of pancake constructions

pcs express properties that hold in general, that is, they are not restricted to just one particular instantiation of the property (e.g. Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2019:533). In that sense they are generic constructions (Carlson & Pelletier Reference Carlson and Jeffrey Pelletier1995). Based on the type of property that they express, pcs can be categorised as either substance-denoting (nominal) or situation-denoting (propositional) (Josefsson Reference Josefsson2009, Josefsson in preparation). Semantically, substance-denoting pcs name an inherent property of the subject, i.e. a property that is ascribed directly to the subject, as in (5a), while situation-denoting pcs name a property of the subject that is event-bound, i.e. realised in a situation, as in (5b) (Wechsler Reference Wechsler, Hofmeister and Norcliffe2013, discussed in Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2014:175).Footnote 5

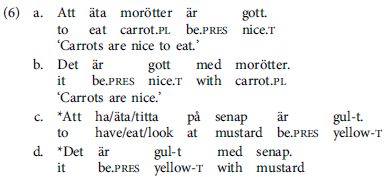

As discussed in Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2009), situation-denoting pcs can often be rewritten with an infinitival att-clause (‘to’-clause), (6a), or as an expletive construction with the subject in a med-phrase, as in (6b). This is generally not possible with substance-denoting constructions, (6c)–(6d):

Another difference between the constructions is that situation-denoting pcs, but not substance-denoting ones, allow for more than one phrase preceding the verb, (7a) vs. (7b) (cf. Josefsson Reference Josefsson2009:45).

In (7a) the phrases till korven and på lördagsbrunchen must be a part of a bigger constituent, senap till korven på lördagsbrunchen, since there is no violation of the V2 constraint. Crucially, this involves a situation interpretation of the constituent, indicated by gott ‘good’. An adjective like gul ‘yellow’ is semantically incompatible with the situation reading of the subject in (7b). Here the same phrases lead to a V2 violation, indicating that there is more than one constituent preceding the finite verb. Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2009) explains this difference between the two types of pc in structural terms, as will be discussed in Section 2.1 below.

Whether the pc is of the substance or situation type thus depends on both the subject and the predicative adjective. For substance-denoting pcs to arise, the subject needs to be able to get a substance or a concept interpretation and the adjective needs to denote an inherent, typically physical, property of this entity. For the situation-denoting type to arise, what is crucial is that the adjective can be used to evaluate processes (Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2014:178) and the subject must be compatible with a situation reading.

pc subjects are typically bare nouns, but they can also appear with pre-modifiers. Pre-modifying adjectives agree in number and gender with their head noun (see e.g. Faarlund Reference Faarlund1977:242, Teleman et al. Reference Teleman, Hellberg and Andersson1999:vol. III, 67). That is, they display regular agreement rather than t-agreement:

When a modifier is present, the agreement preferences for the predicative adjectives change. Åkerblom (Reference Åkerblom2020:95–98) investigated this in two corpus studies, one on unmodified and one on modified pcs. Looking at the first 100 relevant hits generated by the two search strings in the subcorpus Bloggmix 2016 (Borin et al. Reference Borin, Forsberg and Roxendal2012), he found that regular agreement was rare in unmodified pcs (13%) but almost as common (47%) as t-agreement in modified pcs. As will be discussed below, the two approaches to pcs that we look at make different predictions for how modification should affect the two types of pc. On the semantic approach, pre-modification should affect pcs across the board, making regular agreement more acceptable (Enger Reference Enger2004, Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2019). On the syntactic approach, pre-modification should affect agreement in substance-denoting pcs but not in situation-denoting ones.

2.1 Agreement in pancake constructions

The observation that we get t-agreement in pcs has been accounted for in different ways and from different theoretical perspectives. In the following, we look at one semantic approach and one syntactic approach. The approaches share the view that the nature of the subject is at the heart of the issue, albeit in quite different ways in the two approaches. In the semantic one, the interpretation of the subject leads to a special type of agreement mechanism, distinct from regular syntactic agreement. In the syntactic approach, the subject in pcs has a different feature set-up from subjects in other constructions, and this is reflected in the morphological output of the agreement process.Footnote 6

2.1.1 A semantic approach: (un)boundedness

The notion of boundedness is crucial in the semantic approach argued for by Haugen & Enger (Reference Haugen and Enger2019). Entities differ with regard to whether they are bounded or unbounded. The entity ‘book’, for instance, is bounded, while ‘sand’ is unbounded. Bounded entities are typically countable, i.e. can appear in both the singular and the plural (one book, two books) and they have a high degree of individuation (the property of not being something else, while at the same time being distinguishable from other things of the same type; see Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2019:541). Unbounded entities, on the other hand, are uncountable masses, i.e. lack number, and have a low level of individuation. Unbounded entities are also very low on the animacy hierarchy, while the most individuated entities, human entities, are at the top of this hierarchy (see also Corbett Reference Corbett1991, Dahl Reference Dahl, Unterbeck, Rissanen, Nevalainen and Saari2000). On the semantic view on gender that Haugen & Enger (Reference Haugen and Enger2019) adopt for the Scandinavian languages, neuter is the gender used for mass entities and entities that are low on the animacy hierarchy.

Crucially, the subjects of both the substance- and situation-denoting types of pc are interpreted as unbounded entities, and this is what leads to the special kind of agreement (Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2019:547). Due to this interpretation, the lexical gender specification of the nouns and the normal agreement mechanism are overridden. Instead, there is semantic agreement in the neuter between the subject and the predicative adjective.Footnote 7

It is possible to be more or less bounded, according to Haugen & Enger (Reference Haugen and Enger2019:546). If a noun is modified, it is perceived as being more bounded than if it is not modified, but crucially, the difference in boundedness is in the qualitative domain (see Langacker Reference Langacker2008) rather than the spatial. A modified mass noun thus differs from its unmodified counterpart in qualitative aspects, making the extension of the modified noun more restricted than the unmodified one. Because modifiers make the subject entities more bounded on this view, both regular agreement and neuter gender agreement are possible in modified pcs (example from Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2019:545):Footnote 8

According to Haugen & Enger (Reference Haugen and Enger2014:174), subjects of substance- and situation-denoting pcs are of the same type. What they seem to have in mind is subjects that denote unbounded masses, like ‘mustard’ and ‘custard’ in (5). Since modification has an effect on the boundedness interpretation of these subjects, we furthermore expect the effect of modification to be the same in substance- and situation-denoting pcs. An important subtype of situation-denoting pcs (see footnote 2) have de-verbal nouns as subjects, however, like ‘cycling’ or ‘dancing’ (Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2019:548f). These differ from mass entities in that they refer to ‘ungrounded processes’ in pcs. Like subjects that denote mass entities, these de-verbal nouns are ‘conceptualized as virtual things’ in pcs (Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2019:560). That is, they do not refer to specific instantiations, but refer generically. The effect of modification of such nouns is not explicitly discussed by Haugen & Enger (Reference Haugen and Enger2019), but we assume that the qualitative change in boundedness induced by modification of mass nouns should apply to de-verbal nouns too.

To sum up, on Haugen & Enger’s (Reference Haugen and Enger2019) account, subjects in pcs are interpreted as unbounded entities and therefore trigger semantic neuter gender agreement. If the subjects are modified, however, they become less unbounded and therefore regular agreement is also possible.

Based on this, we expect speakers to produce the t-form in unmodified pcs and to prefer t-agreement to regular agreement when rating pcs in our studies. In modified constructions, we expect speakers to produce either the t-form or regular agreement, and they should be more willing to accept regular agreement when rating sentences. What is not clear, however, is whether regular agreement should actually be produced more than t-agreement and should be rated as even better than t-agreement in the modified cases.

2.1.2 A syntactic approach: the absence of number

On the syntactic analysis of t-agreement proposed by Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2006, Reference Josefsson2009, Reference Josefsson2014a,b, in preparation), agreement proceeds in the usual way as a syntactic relation between a noun phrase and a predicative adjective. What makes t-agreement different from regular agreement is the feature specification on the nominal. Regular agreement arises when the noun phrase is specified for number, while t-agreement arises when it lacks number or the number feature is too deeply embedded in the phrase to be visible on the nominal head.

In a similar vein to Haugen & Enger (Reference Haugen and Enger2019), Josefsson argues that pcs have non-specific subjects. The non-specific reading emerges in the presence of a Class(ifier) head at the top of the nominal projection (Josefsson Reference Josefsson2014a:67f). Footnote 9,Footnote 10

The Class head can take complements of different size, as shown in (10),Footnote 11 accounting both for the difference between subjects in substance- and situation-denoting pcs and for the difference between modified and unmodified ones.

In unmodified substance-denoting pcs, the Class head takes an NP complement with no number specification, resulting in t-agreement on the predicative adjective. When the subject is modified, however, the nominal must be specified for number (Josefsson Reference Josefsson2009:41–42). Pre-modifying adjectives always show regular agreement, i.e. they agree with their head noun in number and gender, (11), and they therefore require the presence of number in the nominal. The Class head thus takes a number phrase, NbP, as its complement in modified substance-denoting pcs.

In modified substance-denoting pcs, where the complement of the Class head is thus a NbP, according to Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2014b), the number feature will be visible at the ClassP level, and regular rather than t-agreement will be the result on the predicative adjective (for discussion, see Josefsson, in preparation).

In situation-denoting pcs, the Class head has more structure in its complement, typically a verb phrase or a small clause, explaining why adverbial modification inside the subject, as in (7a) above, is possible. Since the noun phrase is more deeply embedded in situation-denoting pcs, appearing inside the verb phrase or small clause, the presence of a pre-modifying adjective should have no effect for agreement with the predicative adjective (Josefsson Reference Josefsson2009:41–42). That is, the number phrase will be too deeply embedded to be visible at the ClassP level.

On the syntactic approach then, we expect both substance- and situation-denoting pcs to have t-agreement when they are unmodified, reflected both in what forms are produced and how the sentences are rated in our three studies. In modified constructions, however, we expect to see a difference between the pc types. In modified substance-denoting pcs, speakers should produce regular agreement and rate this as better than t-agreement, while in situation-denoting pcs, we expect t-agreement, regardless of modification.

In sum, in our understanding, the semantic and syntactic approaches make the same prediction for unmodified pcs: speakers should produce t-agreement rather than regular agreement, and they should rate sentences with this type of agreement as more well-formed than sentences with regular agreement. For modified pcs, on the other hand, the predictions diverge for the two approaches. On the semantic approach, regular agreement should be equally possible in both types of modified construction, so that regular agreement should be produced more and be rated as more acceptable. On the syntactic approach, modification should have a much more substantial effect on production and rating in substance-denoting pcs than in situation-denoting pcs. In the following, we present the results from three studies where we investigate how speakers rate pc with t-agreement and regular agreement, respectively, and what agreement forms are produced.

3. Study 1: Acceptability study

At the same time as both the semantic and the syntactic approach to pcs predict unmodified pcs to appear with t-agreement, findings from two corpus studies show that there is variation in agreement forms produced (Åkerblom Reference Åkerblom2020). Given the somewhat unclear status of unmodified pcs with regular agreement, and the even more unclear picture of what agreement preferences should hold for modified pcs, we conducted an acceptability study to assess how speakers rate such sentences. The aim of Study 1 was thus to find out to what extent speakers find the two types of agreement acceptable in pcs and what effect the presence of a pre-modifier in the subject noun phrase has on ratings. We were also interested to see whether a change in the verb phrase has an effect on agreement preferences. As mentioned, we had the impression that the presence of a modal verb makes regular agreement more acceptable, and we wanted to see whether this was reflected in ratings more generally. Thus, in order to investigate the effects of modality, we included sentences with an overt modal(-like) verb.

3.1 Method and material

We constructed 160 experimental items of eight sentences each, as in (12) (thus in total 1280 sentences). All sentences had a non-plural, common gender subject. The sentences were manipulated along three dimensions: agreement (regular agreement, reg, vs. t-agreement, t) on the predicative adjective, pre-modification (modified, +mod, vs. unmodified, −mod), and modal(-like) verb (+modal vs. −modal). The modal verbs that we used were bör ‘should’, får ‘may’, kan ‘can’, lär ‘is said/known to’, måste ‘must’, and ska ‘should’. We also included the verb brukar ‘usually do’, which is aspectual rather than modal, but which has a meaning that is similar to one of the readings of kan ‘can’.

The eight sentences in each item were distributed across four lists, such that each list contained an equal number of each manipulation. There were thus 320 sentences on each list. In order not to make the session too long for the participants, no filler sentences were added. The two sentences from the same item that appeared on the same list always differed in more than one feature. That is, sentences (12a) and (12b), or sentences (12c) and (12d), for instance, never appeared on the same list. Forty-eight of the items were substance-denoting and 112 were situation-denoting pcs. The sentences were categorised for subtype by the authors independently. They were analysed as substance-denoting if the property given was one that holds irrespective of the existence of an event, while they were analysed as situation-denoting if the property was dependent on the existence of an event. In the few cases where there were discrepancies between the authors in their categorisations, a discussion of the most likely interpretation took place to agree on the analysis.

We recruited thirty-five native speakers of Swedish for this study, and each one was assigned one of the four experimental lists. The participants were placed in a computer lab where they read sentences (implemented in Google forms) on a computer screen at their own pace and rated them on a Likert scale from 1 (‘really weird’) to 7 (‘perfectly natural’). There was no time limit but the participants were asked not to dwell too long on each sentence but rate them according to their immediate reaction; for the use of similar methodology, see Heinat & Klingvall (Reference Heinat and Klingvall2019) and Klingvall & Heinat (Reference Klingvall and Heinat2021, Reference Klingvall and Heinat2022a, Reference Klingvall and Heinat2024b).

3.2 Results

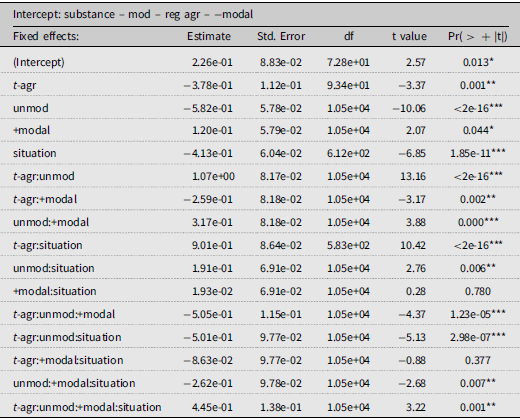

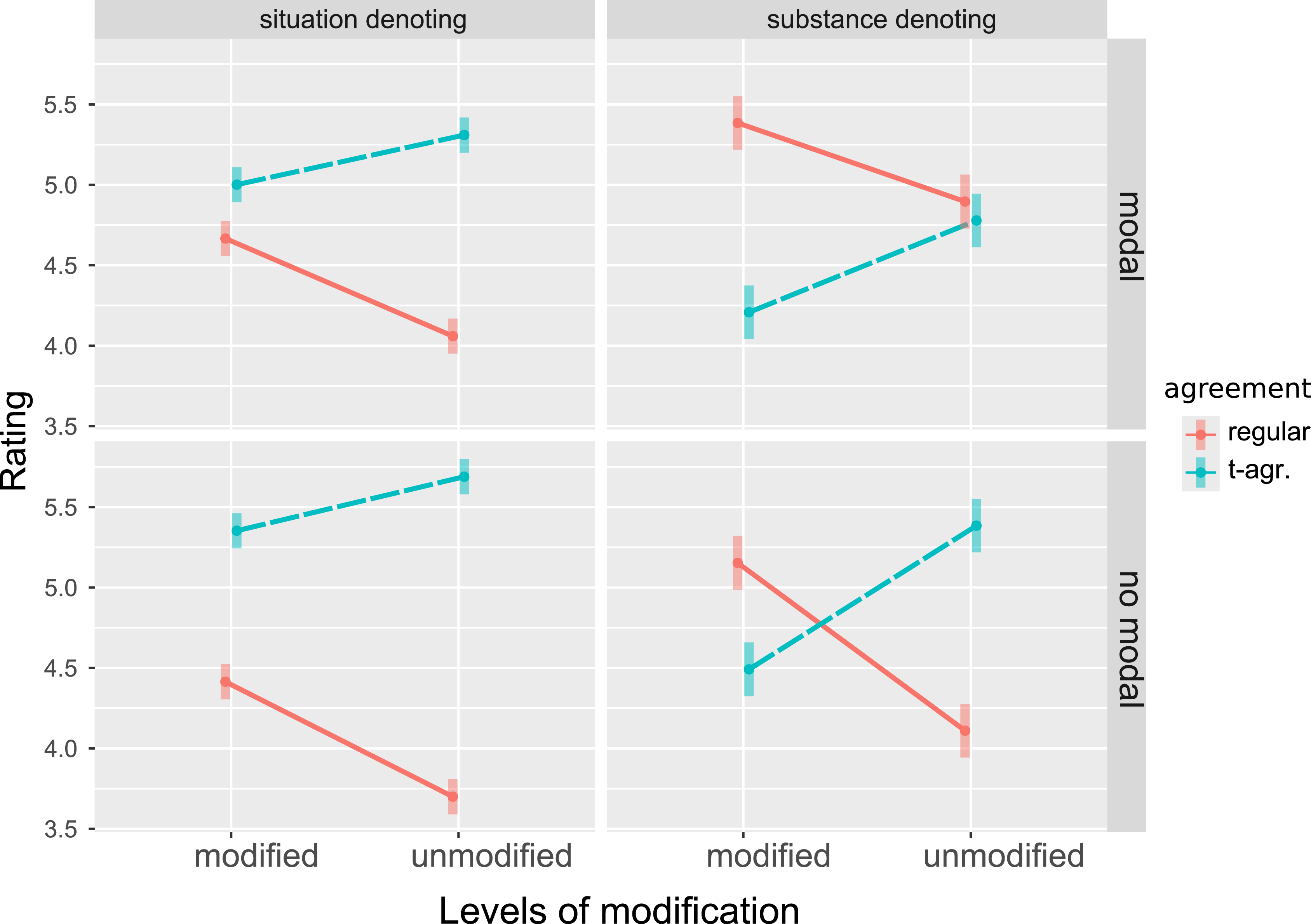

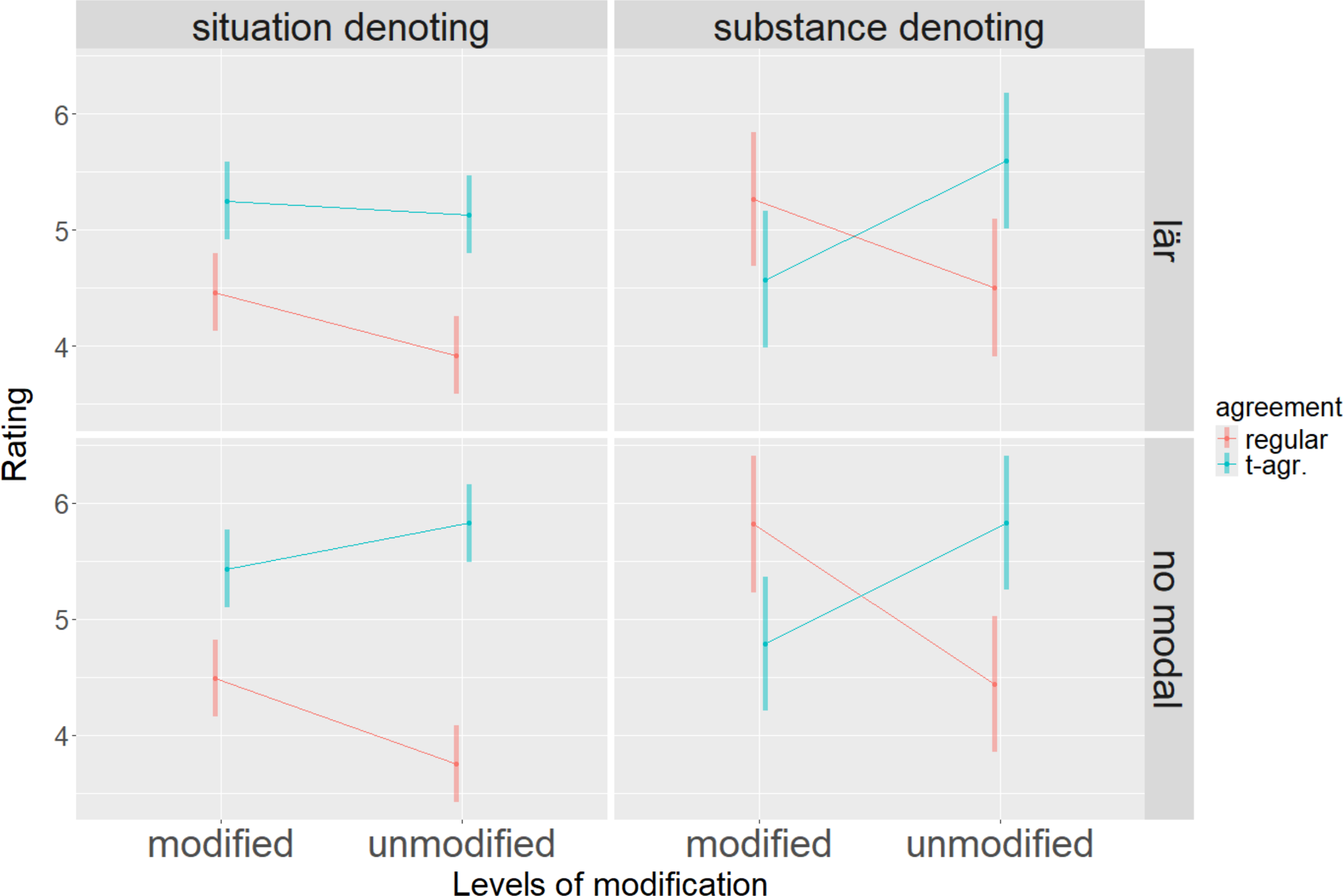

The plots for Study 1 are based on the results from the linear mixed effects model and its estimated means, as shown in Table A1 in the Appendix.

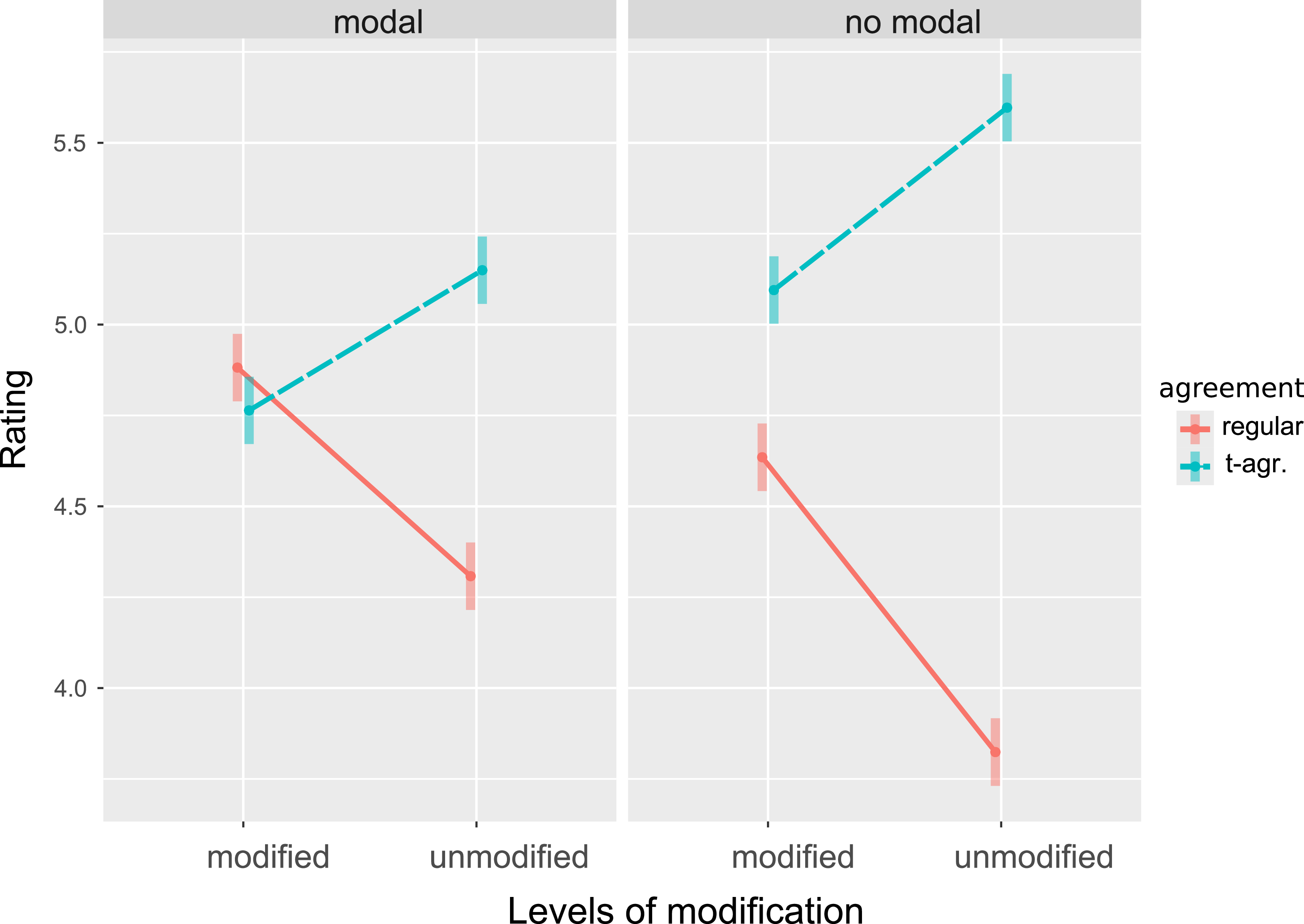

Figure 1 shows the result for substance-denoting and situation-denoting pcs taken together.Footnote 12 The overall result was that t-agreement (green dashed line) is preferred over regular agreement (red solid line) unless the subject was modified and there was also a modal verb present. In that case, t-agreement and regular agreement were rated as equally good. Although both types of agreement were affected by modification, the effect was most pronounced for regular agreement.

Figure 1. Ratings of all sentences together. Bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

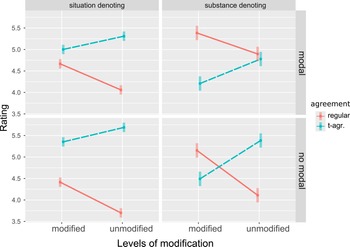

Somewhat different results hold when substance-denoting and situation-denoting pcs are considered separately, as shown in Figure 2 and Table 1. In substance-denoting pcs, t-agreement was preferred over regular agreement only in bare pcs, i.e. those without a pre-modifier in the subject and with no modal verb present. Whenever the subject was modified or a modal verb was present, regular agreement was either preferred (with modification and with or without a modal) or was rated as equally good as t-agreement (with a modal but without modification). The effect of modification was much larger when no modal verb was present, affecting t-agreement negatively and regular agreement positively. Similarly, the effect of modality was strongest in the absence of modification, again affecting t-agreement negatively and regular agreement positively.

Figure 2. Ratings of situation-denoting and substance-denoting sentences. Top panels with a modal; bottom panels without a modal. Bars indicate 95% confidence interval.

Table 1. Results of Study 1: mean ratings of substance- and situation-denoting pcs.

In situation-denoting pcs, t-agreement was always preferred, although regular agreement was rated as almost as good when the subject was modified and there was a modal verb present. The presence of a pre-modifier had a positive effect on regular agreement both in the conditions with a modal verb and in those without. For t-agreement, modification did not affect ratings very much. While modality, too, did not have a strong effect in situation-denoting pcs, it did affect both types of agreement to the same extent, although in different directions (t-agreement negatively, regular agreement positively).

The overall pattern for modality was that it affected t-agreement negatively and regular agreement positively. The effects were strongest in unmodified pcs and in particular in substance-denoting ones. The verb lär ‘is said/known to’ diverged from this pattern in that it neither had the negative effect on t-agreement nor the positive effect on regular agreement otherwise observed (see Figure A1 in the Appendix). In unmodified substance-denoting pcs, t-agreement was thus rated as more acceptable than regular agreement.

3.3 Discussion

The aim of Study 1 was to investigate the acceptability of pcs with t-agreement and regular agreement, respectively, and to see what effects pre-modification and the presence of a modal verb had on the ratings. Not surprisingly, t-agreement was rated as more acceptable than regular agreement for all bare pcs, i.e. those that did not have a pre-modifier or a modal verb. This is what is predicted by both the syntactic and semantic approaches to pcs. Interestingly however, although regular agreement received much lower ratings than t-agreement in bare pcs, the ratings were still quite high. Given the number of sentences to rate for each participant, we did not include any filler items and we therefore do not know how the sentences with regular agreement compare to other cases of agreement mismatches, such as the following (with definite subjects in (13a)–(13b) and a pc with a neuter gender subject in (13c)):

Although these sentences are ill-formed with the non-agreeing form of the predicative adjectives, it is still an empirical question what ratings participants would actually give them. Notably, acceptability judgements are well known to reflect much more than morpho-syntactic well-formedness; see, among others, Schütze (Reference Schütze1996), Schütze & Sprouse (Reference Schütze, Podesva and Sharma2013:46–47), and Sprouse et al. (Reference Sprouse, Messick and David Bobaljik2022:373). For instance, sentences that are structurally complex and therefore hard to process typically have lower perceived acceptability even if they are fully grammatical, and conversely, sentences that are not fully grammatical but are semantically well-formed often have higher perceived acceptability than expected on purely syntactic terms. In our study, all sentences are fully interpretable and easy to process, and these factors are likely to affect the acceptability judgements in a positive direction, even for the sentences with unexpected agreement forms. What is clear is that regular agreement is less acceptable than t-agreement in bare pcs.Footnote 13

Modification

Looking at the effect of modification when there was no modal verb present, we see that it mattered to a much larger extent in substance-denoting pcs than in situation-denoting ones. In substance-denoting pcs, modification had an effect on both regular agreement and t-agreement – a positive effect in the former and a negative effect in the latter. As a result, regular agreement was preferred over t-agreement in these cases. In situation-denoting pcs, on the other hand, modification had a strong effect on regular agreement but only a small effect on t-agreement. While regular agreement thus improved in the presence of a modifier, the preference for t-agreement still remained.

Looking at these findings in light of the two approaches to pcs discussed above, we can see that neither of them explains all the data. On the semantic approach, modification should make regular agreement more acceptable because the subjects are interpreted as less unbounded when they are modified. This is indeed what we see if we look at the constructions overall. However, the clear differences that we also see between the subtypes do not fall out from this approach.

On the syntactic approach, modification should affect agreement in substance-denoting pcs but not in situation-denoting ones. In substance-denoting pcs, the subject has much less structure than in situation-denoting pcs. The number feature that the modifier necessarily comes with is therefore visible for agreement in the substance-denoting type but not the situation-denoting type, in which it is more deeply embedded. t-agreement arises when no number feature is visible. Indeed, as predicted on this analysis, both regular agreement and t-agreement are affected by the presence of a modifier in substance-denoting pcs. The fact that there is a difference in this regard between substance- and situation-denoting pcs also falls out from the analysis. What needs to be explained, however, is why regular agreement improves in situation-denoting pcs in the presence of modification, as the presence or absence of modification should be syntactically invisible from the perspective of agreement.

Modality

The effect of modality on agreement preferences in pcs is interesting and has not previously been discussed. As with modification, t-agreement was negatively affected by the presence of a modal-like verb, while regular agreement was positively affected. These effects were strongest when there was no modifier present and much stronger in substance-denoting pcs than in situation-denoting ones. Like modification, modality affects the interpretation of pcs. Rather than stating properties that hold generically, pcs with modals express properties that hold in those possible worlds picked out by the modals.Footnote 14 On the semantic approach, this change in meaning could perhaps affect agreement in a similar way to modification although the changes in meaning are not the same. As is the case with modification, however, the systematic difference between the two subtypes in how modality affects agreement needs to be explained.

On the syntactic approach, the explanation for why modality plays a role must be different from why modification matters. There seem to be certain tendencies with regard to agreement form and a deontic or an epistemic reading of the modal. If these modal readings can also be related to different scopal properties of modals, they might also differ syntactically. As is well known, many modal verbs can give rise to both deontic and epistemic readings. The two types of agreement seem to lend themselves to one or the other of the modal readings more readily, at least in the context of pcs. With regular agreement, a deontic reading for the verb ska ‘should’, for instance, seems more close at hand (and perhaps the only possibility), (14a), while with t-agreement, an epistemic reading seems to be more readily available, although a deontic reading is also possible, (14b) (our interpretations):

If these tendencies hold more generally, speakers might be pushed towards a deontic reading when the adjective has regular agreement, and perhaps towards an epistemic reading with t-agreement. Such readings might be more or less felicitous in the individual cases and therefore affect ratings. For instance, the verb lär ‘is said/known to’ can get an epistemic (or evidential) reading, but cannot get a deontic reading. To us, it also seems degraded with regular agreement, (15a) (our judgements), although this needs to be more systematically investigated:

While the presence of a modal verb generally had a positive effect on regular agreement and a negative effect on t-agreement, this was not the case for lär. More specifically, in substance-denoting pcs, the modal did not have the usual positive effect on regular agreement and did not have the usual negative effect on t-agreement. From our study, we cannot draw any firm conclusion about the behaviour of particular modal(-like) verbs, since they were not factors in the study. We only manipulated the presence or absence of any modal(-like) verb, not the particular verbs themselves. We think, however, that the results can serve as pointers to what should be looked into in more detail in future studies.

4. Study 2: Production study

Study 1 investigated the extent to which speakers accept pcs with t-agreement and regular agreement, respectively. In Study 2, we instead investigated what speakers’ agreement preferences are in production of pcs with and without a pre-modifier in the subject and with and without a modal(-like) verb.

4.1 Method and material

Study 2 was a sentence-completion task where participants were presented with a prompt as in (16) and were asked to write a continuation of it (which could consist of one or more words). Each participant saw only one prompt and thus wrote only one continuation. The number of participants was 501, of which 12 were excluded from the analysis for not being native speakers of Swedish; for the use of similar methodology, see Klingvall & Heinat (Reference Klingvall and Heinat2022b, Reference Klingvall and Heinat2024a).

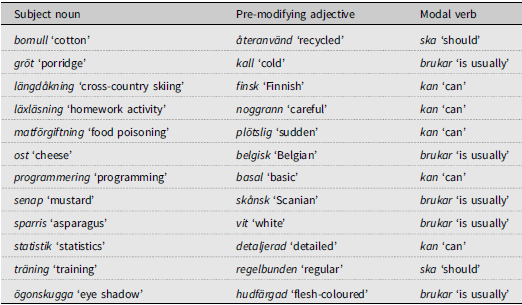

Twelve frames as in (16) were constructed. Each prompt consisted of two sentences, the second of which was incomplete (‘…’). The prompts were manipulated in a 2

![]() $\times $

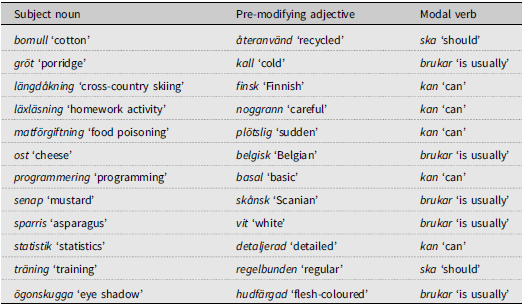

2 design: modification of the embedded subject (modified vs. unmodified) and the presence of a modal(-like) verb (+modal vs. −modal). The subject nouns, with their modifying adjectives and modal verbs, are given in Table 2.

$\times $

2 design: modification of the embedded subject (modified vs. unmodified) and the presence of a modal(-like) verb (+modal vs. −modal). The subject nouns, with their modifying adjectives and modal verbs, are given in Table 2.

Table 2. Nouns, pre-modifying adjectives, and modal verbs in Study 2.

In total, then, there were 48 different prompts and a minimum of 10 responses for each one of them.

4.2 Results

Based on the overall reading that was obtained with the adjectives produced, the complete sentences were analysed as either substance- or situation-denoting pcs by the authors individually. In a few cases where the authors did not agree on the categorisation, the sentences were placed in an ‘indeterminate’ group (unclear). In those cases where a participant had written more than one adjective, e.g. krämig och god ‘creamy and nice’, the response was counted twice, one for each adjective.

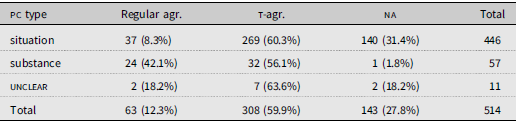

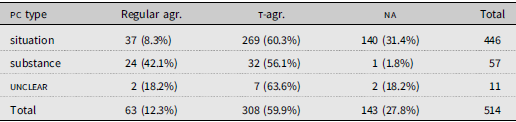

Table 3 shows the number of substance-denoting, situation-denoting, and indeterminate pcs, respectively, as well as what type of agreement they featured. As seen in the table, a number of adjectives had an invariable form, i.e. an adjective for which there are no morphological gender or number distinctions. These were placed in the category gender not applicable (na) and are not included in the rest of the tables. Most pcs were of the situation-denoting type, with a much smaller number of substance-denoting pcs. As regards agreement patterns, t-agreement was the most common agreement type (59.9%) overall. In the substance-denoting category, however, regular agreement was present in 42.1% of the cases.

Table 3. Overall results from Study 2.

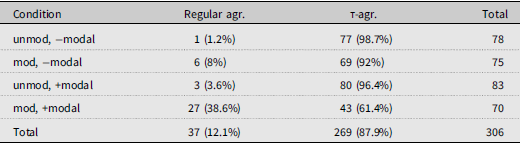

Tables 4 and 5 show the results for situation-denoting and substance-denoting pcs separately. As seen in Table 4, t-agreement was the most common agreement pattern for situation-denoting pcs in all conditions. Regular agreement was however more common in the condition with both modification and a modal verb (at 38.6%) than it was in the other conditions.

Table 4. Results for situation-denoting pcs.

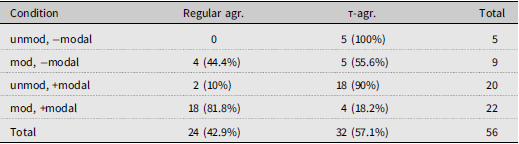

Table 5. Results for substance-denoting pcs.

As shown in Table 5, the distribution between regular agreement and t-agreement was more even for substance-denoting pcs. In the two conditions with modification, regular agreement was either nearly as common as t-agreement (4 vs. 5 sentences, with no modal present) or was much more common than t-agreement (when there was also a modal verb). It was only when no modifier was present that t-agreement was clearly more common than regular agreement.

4.3 Discussion

In the production study, the main tendency was for the participants to complete the sentence so that it turned into a situation-denoting pc and to use t-agreement on the adjective. Although both substance- and situation-denoting pcs would in principle have been possible for all of the prompts, it is fair to say that the prompting sentences in most cases led the participants to focus on events in which some property was instantiated, rather than on inherent, physical properties of the subject nouns. The item in (16), above, is an example of that: speakers naturally comment on what it is like to eat mustard.

Regarding regular agreement, the results show that the participants used it somewhat more in the presence of a modifier (and only very rarely without one), in particular if there was also a modal verb present, and more so in substance-denoting constructions than in situation-denoting ones. These results accord well with how speakers rated sentences in Study 1. In relation to the theories we presented earlier, we can say that the results showing that modification (on its own) promotes regular agreement to some extent in both substance- and situation-denoting pcs are in line with the approach in Haugen & Enger (Reference Haugen and Enger2019), as we interpret it. At the same time, the effect of modification was small in situation-denoting pcs. This difference between the pc types is in accordance with the analysis in Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2009, Reference Josefsson2014a).

5. Study 3: Corpus study

While the production study investigated what agreement form speakers use when they produce pcs, the contexts were already given and in that sense restricted speakers in their continuations. In Study 3, we therefore conducted a larger corpus investigation of a subset of the subject nouns appearing in Study 2. In that way we got a much larger set of production data for the selected nouns.

5.1 Method and material

For the corpus study, we selected six nouns from Study 2: gröt ‘porridge’, läxläsning ‘homework activity’, ost ‘cheese’, programmering ‘programming’, senap ‘mustard’, and träning ‘training’. Out of these, gröt ‘porridge’, ost ‘cheese’, and senap ‘mustard’ are concrete nouns that can easily be the subject of both substance-denoting and situation-denoting pcs. Läxläsning ‘homework activity’, programmering ‘programming’, and träning ‘training’, on the other hand, are nominalisations of verbs and are therefore very naturally connected to events, thus lending themselves easily to situation-denoting pcs.Footnote 15 Even nominalisations, however, have the ability to refer to entities (Grimshaw Reference Grimshaw1990), so they could in principle also form substance-denoting pcs.

The searches were made in Korp (Borin et al. Reference Borin, Forsberg and Roxendal2012).Footnote 16 The search string picked out data in which the subject noun could (but did not have to) be pre-modified, and allowed for one word to appear between the subject noun and (a form of) the verb vara ‘be’ so that strings with a modal verb were included.Footnote 17 Since we restricted our searches to strings with at most one word appearing between the subject and the verb vara, we did not get any hits with, for instance, both a modal verb and negation (e.g. Ost kan inte vara laktosfri ‘Cheese cannot be lactose-free’). This choice was made to limit our data to a reasonable amount and to make Study 3 more comparable to Studies 1 and 2. Once the corpus data was extracted, duplicate hits, non-pcs, pcs with coordinated subjects, and pcs with an invariable predicative adjective were manually removed. After that, each remaining hit was annotated for the presence (or absence) of a pre-modifying adjective (in this category we also included quantifying determiners that did not make the NP definite)Footnote 18 and of a modal verb, as well as the type of agreement on the predicative adjective. Following that, the hits were analysed in terms of pc type (substance-denoting or situation-denoting) by the three authors independently. Some hits were potentially ambiguous between the two pc types. In these cases, the context surrounding the pc was considered carefully to arrive at the most plausible classification. Cases where the authors could not agree on the most plausible reading were removed from the analysis.

5.2 Results

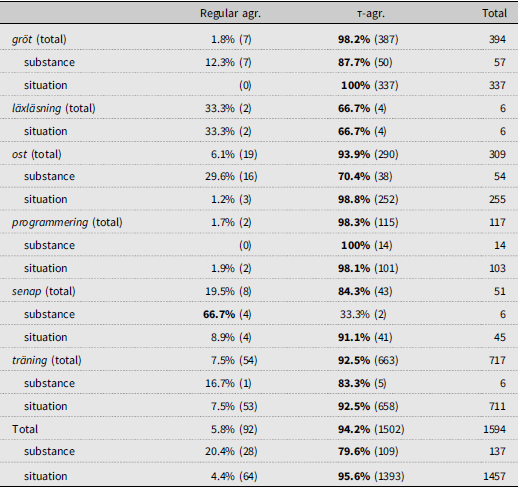

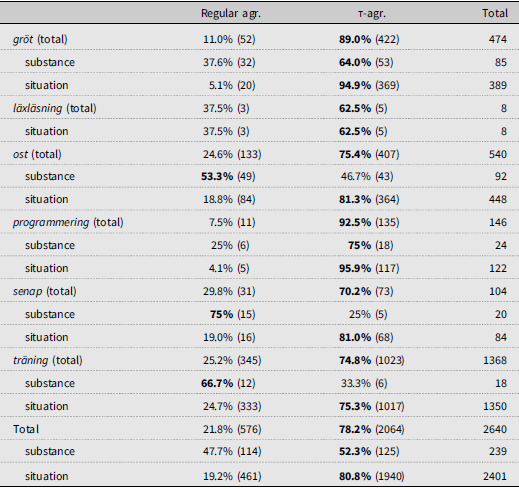

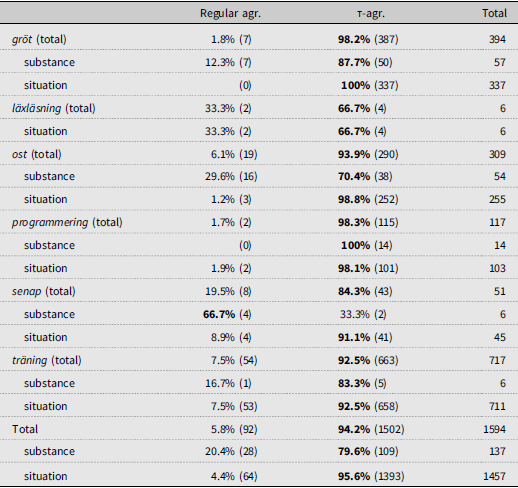

Table 6 shows that the number of hits for each noun varied substantially: for läxläsning ‘homework activity’ there were only 8 relevant hits, while for träning ‘training’ there were 1368 remaining hits.

Table 6. Results of Study 3: agreement overall.

gröt ‘porridge’, läxläsning ‘homework activity’, ost ‘cheese’,

programmering ‘programming’, senap ‘mustard’, träning ‘training’

Table 6 also shows that, overall, t-agreement was much more common than regular agreement (78.2% vs. 21.8%). When splitting the pcs into their two subtypes, however, we can see that the strong bias for t-agreement was predominantly present for situation-denoting pcs. In substance-denoting pcs, the distribution of agreement forms was more even, in some cases even favouring regular agreement.

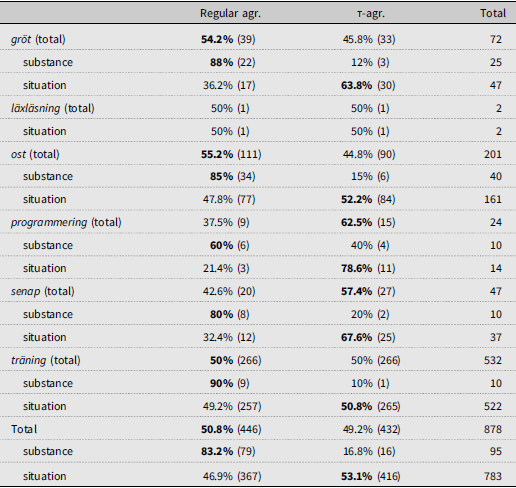

When looking at bare (i.e. unmodified, modal-less) and modified pcs separately, different patterns also emerge: Table 7 shows that in bare pcs, t-agreement was by far the most common type, except for substance-denoting pcs with senap as subject. In pcs with a pre-modified subject, on the other hand, regular agreement and t-agreement were equally common (50.8% for regular agreement vs. 49.2% for t-agreement), as seen in Table 8. The effect is driven by agreement in substance-denoting pcs, in which regular agreement was much more common than t-agreement (83.2% vs. 16.8%). In situation-denoting pcs, in contrast, t-agreement was slightly more common than regular agreement (53.1% vs. 46.9%).

Table 7. Results of Study 3: agreement in bare pcs.

gröt ‘porridge’, läxläsning ‘homework activity’, ost ‘cheese’

programmering ‘programming’, senap ‘mustard’, träning ‘training’

Table 8. Results of Study 3: agreement in pre-modified pcs.

gröt ‘porridge’, läxläsning ‘homework activity’, ost ‘cheese’,

programmering ‘programming’, senap ‘mustard’, träning ‘training’

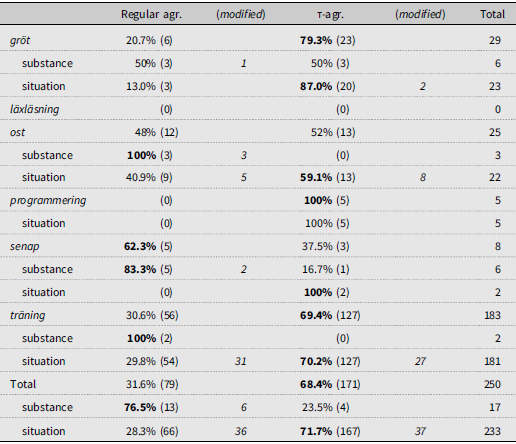

pcs with a modal verb were quite rare in the data and two-thirds of these had t-agreement, as shown in Table 9. In those substance-denoting pcs that contained a modal, however, regular agreement was more common than t-agreement (76.5% vs. 23.5%). The distribution in situation-denoting pcs was the opposite (28.3% regular agreement vs. 71.7% t-agreement). Notably, a good number of the sentences with a modal verb also included a pre-modifier in the subject, as shown in the table.

Table 9. Results of Study 3: agreement in pcs with a modal verb.

gröt ‘porridge’, läxläsning ‘homework activity’, ost ‘cheese’, programmering ‘programming’

senap ‘mustard’, träning ‘training’

Across the nouns, the vast majority of pcs with t-agreement had bare subjects: 1502 hits with bare subjects (Table 7: t-agr., Total)Footnote 19 vs. 432 hits with pre-modified subjects (Table 8: t-agr., Total). For regular agreement, it was the other way around: 446 hits with pre-modified subjects (Table 8: Regular agr., Total) vs. 92 hits with bare subjects (Table 7: Regular agr., Total).

Zooming in on substance-denoting pcs for the different nouns, we see that there were only 16 hits showing t-agreement with pre-modified subjects (Table 8: t-agr., Total, sub), and there were also relatively few cases, 28 hits, of regular agreement with bare subjects (Table 7: Regular agr., Total, sub).

5.3 Discussion

In the corpus study, we looked at the agreement patterns of pcs with the nouns gröt ‘porridge’, läxläsning ‘homework activity’, ost ‘cheese’, programmering ‘programming’, senap ‘mustard’, and träning ‘training’ as subject in the presence and absence of a pre-modifier and a modal verb. For all these nouns, t-agreement was overall more common than regular agreement and this was also the case when only bare pcs were taken into account. This is what is expected on both the semantic and the syntactic accounts of pcs and is also what Åkerblom (Reference Åkerblom2020) found in his corpus study.

When the constructions had a pre-modifier in the subject, the cases of regular agreement increased for both types of pc, although much more substantially for substance-denoting ones. For the semantic approach, the difference between the two subtypes of pc in how they were affected by modification is not immediately obvious and calls for an explanation, while for the syntactic approach it is the fact that situation-denoting pcs were also affected by modification that should be explained.

Nouns like gröt, ost, senap ‘porridge, cheese, mustard’ get a mass interpretation in pcs, and when these nouns are modified they become more bounded, i.e. more restricted in reference, according to the semantic account (Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2019:546). Such nouns should thus be affected in the same way in both substance- and situation-denoting pcs, in our understanding. One might hypothesise that the nouns läxläsning, programmering, träning ‘homework activity, programming, training’, on the other hand, should behave in a different way because they are de-verbal nouns. However, if modification has the effect of making mass nouns more bounded because they are qualitatively more specified, it seems to us that the same thing should apply to de-verbal nouns. In other words, unless otherwise stated, modification should have the same effect for both types of noun in both subtypes of pc. However, it seems that some other property of situation-denoting pc needs to be invoked to explain the difference between the two subtypes. On the other hand, what does fall out neatly from the analysis in Haugen & Enger (Reference Haugen and Enger2019) is the fact that not only substance-denoting pcs but also situation-denoting ones are affected by modification.

The fact that regular agreement is more common in modified than in unmodified situation-denoting pcs is a problem for the syntactic analysis (Josefsson Reference Josefsson2009, Reference Josefsson2014a). The number feature associated with modification should be too deeply embedded to be visible at the highest node (the Class level) of the noun phrase. On the other hand, the two predictions for substance-denoting pcs that fall out from the syntactic approach, namely that there should not be any cases of regular agreement in bare ones, and that there should not be any cases of t-agreement in modified ones, are largely borne out in the corpus study, even if there are exceptions. Examples in our data of the unexpected patterns are given in (17). The example in (17a) is a modified situation-denoting pc with regular agreement. As discussed above, this agreement form is unexpected under Josefsson’s syntactic analysis but possible under Haugen & Enger’s semantic analysis. For sentences like these, t-agreement was preferred over regular agreement in Study 1. The example in (17b) is an example of a pre-modified substance-denoting pc with t-agreement. Again this is unexpected under the syntactic analysis, and in our Study 1 regular agreement is preferred. The example in (17c) is an unmodified substance-denoting pc with regular agreement. In this case, t-agreement would have been expected under both analyses.

It is of course impossible to know whether the writers of these text snippets truly intended the predicative adjectives to have these forms (in these examples and others in the corpus), or whether they are mistakes. The mere existence of unexpected structures in a corpus does not in itself mean that the structures are acceptable. At the same time, if there are many such examples, they need to be accounted for.

Turning to the role of modality, we find it difficult to draw any strong conclusions, since modal verbs were overall rare in the corpus findings with a total of 250 hits (corresponding to 9.5% of the total number of hits). Certain clear tendencies can still be discerned however. Although the numbers are small for each noun, we can see that regular agreement is more common than t-agreement in substance-denoting pcs with a modal verb and vice versa in situation-denoting pcs. Notably, however, around half of the cases of substance-denoting pcs with a modal and regular agreement also contain a modifier, so the effect of the modals themselves is hard to tease apart from the effect of modification. Given the results from Study 1, it nevertheless seems likely to us that modal verbs in themselves have an effect on agreement preferences in substance-denoting pcs.

6 Concluding remarks

In this paper we have looked at what agreement patterns speakers prefer and produce in pcs in Swedish. The three studies we have conducted largely show the same results: t-agreement is preferred in bare pcs of both the substance-denoting and the situation-denoting type. With a pre-modifier in the subject, regular agreement in pcs is rated as more acceptable, to the point of actually being preferred in substance-denoting ones. The presence of a modal verb seems to have a similar effect.

Looking at these patterns in the light of previous analyses of pcs, we note that both the semantic approach in Haugen & Enger (Reference Haugen and Enger2014, Reference Haugen and Enger2019) and the syntactic approach in Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2009, Reference Josefsson2014a, in preparation) can explain some of the agreement patterns, while leaving others unexplained. On the semantic approach something should be said about the systematic difference between substance- and situation-denoting pcs in how they are affected by modification. A reviewer suggests that the difference in how the constructions, and thereby the subjects, relate to processes might be the key to the difference in how they are affected by modification. Whether this difference in how they relate to processes can also explain why the subjects of situation-denoting pcs can be followed by adverbials without violating V2 remains to be shown. Prima facie at least, it seems to be a problem for their claim that the subjects of pcs are of the same type, rather than being syntactically different (see Haugen & Enger Reference Haugen and Enger2014:174). This latter point falls out naturally from the syntactic analysis in Josefsson (Reference Josefsson2009, Reference Josefsson2014a). Josefsson’s analysis makes very clear predictions for what type of agreement should be syntactically possible in the different types of pc, but both acceptability judgements and corpus findings show a more blurred picture. This is perhaps as expected: after all, acceptability judgements reflect much more than syntactic well-formedness. Thus, the fact that judgement scores were overall quite high in Study 1 might be explained by the transparency in interpretation of pcs and their relative ease in processing – factors that are known to have a positive effect on acceptability. Crucially, the forms that should not be possible under the syntactic analysis were indeed always rated as less acceptable than the other ones. As for the corpus findings, it is particularly the occurrences of modified situation-denoting pcs with regular agreement that call for an explanation, on the syntactic approach.

All three studies indicated that the form of the verbal predicate itself also matters for agreement preferences. In this context, not only modality but also aspectual and temporal properties of the verbal predicate and how they interact with modification and possibly also negation should be looked into. Interactions between agreement form and these readings would tell us more about the interfaces between syntactic structure, semantic interpretation, and morphological form.

Acknowledgements

We are grateful to all our participants and for comments from three anonymous reviewers, Kari Kinn, Gunlög Josefsson, and the audiences at the Grammar seminar, Grammar in Focus 2023/24, ‘Microvariation and microchange in the Scandinavian languages’, and Gramino 4. The studies were funded by grants from Olle Engkvists stiftelse: (Dis)agreement in Swedish (227-0234) and Erik Wellanders fond (both to FH).

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Appendix

Figure A1. Study 1: ratings of situation-denoting and substance-denoting items with and without lär ‘is said/known to’.

Table A1. Statistical model for Study 1: fitted linear mixed effects model (using z-scores).

Formula: rating

![]() ${{\rm{\;}}_z}$

${{\rm{\;}}_z}$

![]() $\sim $

gender* modification* modal* constr + (gender

$\sim $

gender* modification* modal* constr + (gender

![]() $|$

item) + (gender

$|$

item) + (gender

![]() $|$

participant)

$|$

participant)

Signif. codes: 0 ‘***’ 0.001 ‘**’ 0.01 ‘*’ 0.05 ‘.’ 0.1 ‘ ’ 1