Introduction

The last years of the 20th century were proclaimed as “the Age of Ecology” (Manes, Reference Manes1990, p. 31). The climatic events of this period positioned the environment at the heart of politics (Black, Reference Black2009), offering a powerful narrative tool (Fløttum & Gjerstad, Reference Fløttum and Gjerstad2017). The goal of this study is twofold. First, it seeks to identify the main climate change narratives that have emerged from the 1960s to the present. I argue that existing efforts to map climate narratives remain limited, as much of the academic literature is fragmented and centred on particular narratives rather than the broader context. Therefore, developing a comprehensive map of climate narratives is essential for two key reasons: 1) to place what the academic literature states on the subject and 2) to identify how these climate narratives justify and guide action. This brings me to my second objective, in which I analyse the extent to which climate change narratives have insufficiently integrated perspectives from territories and cultural contexts beyond the dominant Western geographies. To achieve these aims, this study integrates narrative analysis (Elliott, Reference Elliott2005; Ntinda, Reference Ntinda and Liamputtong2019; Polkinghorne, Reference Polkinghorne1988; Smith & Monforte, Reference Smith and Monforte2020) with a systematic literature review (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009; Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald and Moher2021) to construct a comprehensive map of climate change narratives.

Before proceeding, this study focuses on climate narratives that recognise climate change as an undeniable reality. This focus is essential not only due to the scope of the analysis but also because denialist narratives detract from efforts to address climate challenges by diverting attention and undermining progress (Shue, Reference Shue2023). Such narratives reject empirical evidence (Farmer & Cook, Reference Farmer, Cook, Farmer and Cook2013) and erode trust in scientific institutions (Mishra, Reference Mishra, Sarkar, Bandyopadhyay, Singh, Eds. and iski2024). While the influence of denialist narratives is widely acknowledged, this analysis aligns with the academic consensus (Oreskes, Reference Oreskes2004) that meaningful solutions must be grounded in the recognition of climate change and its impacts (Bretter & Schulz, Reference Bretter and Schulz2023; Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, van der Linden, Maibach and Leiserowitz2019).

In effect, my analysis begins in the 1970s. It is noteworthy that the 1970s are widely recognised as a “turning point” (Therborn et al., Reference Therborn, Eley, Kaelble, Chassaigne and Wirsching2011), a “time of crisis” (Ferguson et al., Reference Ferguson, Maier, Manela and Sargent2010) and a “period of détente” (Heymann, Reference Heymann2017, p. 4). The oil crises were described as “one of the few genuine economic calamities” (Schelling, Reference Schelling1979, p. 6), leading to skyrocketing inflation, an increase in prices beyond imagination, and significant economic and energy implications (Schelling, Reference Schelling1979; Häfele et al., Reference Häfele, Barnert, Messner, Strubegger and Anderer1986; Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2022). During these decades, scholars reported the negligent use and burning of fossil fuels (Cooper, Reference Cooper1978; Keeling, Reference Keeling1970; Schneider, Reference Schneider1975). Keeling (Reference Keeling1970) showed that CO2 levels from fossil fuels considerably impact the climate. Nordhaus (Reference Nordhaus1975) and Schneider (Reference Schneider1975) connected global warming and CO2 emissions, stating the need to maintain climate variations within 2°C or 3°C. The increasing trend of CO2 emissions started to become an alarming issue (Richards, Reference Richards1986), leading to the unprecedented “two-degree target time bomb” (Shaw, Reference Shaw2016, p. 4).

During this time and beyond, the “technological insurance” (Fulkerson et al., Reference Fulkerson, Judkins and Sanghvi1990) served as a unifying force for a sustainable and harmonious global future. Indeed, the blind optimism in technology was widely accepted (Peccei, Reference Peccei1979), along with the belief that significant capital investment would be necessary to develop new energy infrastructures (Hayes, Reference Hayes1977). Schelling (Reference Schelling1979) anticipated that technological advancements would transform and redefine the very nature and use of energy. Notably, energy efficiency was proposed as a solution to address “both global cooling (in the 1970s) and global warming (in the 1990s)” (Randalls, Reference Randalls, van Munster and Sylvest2016, p. 146). Technology has been characterised as “an index of capital accumulation, privileged resource consumption and the displacement of both work and environmental loads” (Malm & Hornborg, Reference Malm and Hornborg2014, p. 3).

The neoliberal framework, shaped by free-market fundamentalism, has demonstrated an inadequate capacity to address environmental challenges (Kovel, Reference Kovel1999; Vlachou, Reference Vlachou2004). The consequences of energy choices (Hayes, Reference Hayes1977, p. 25), the privatisation of water (Bakker, Reference Bakker2005), and the exploitation of common resources (Perkins, Reference Perkins2017) have resulted in significant ecological impacts. For the capitalist system, the “goods” of the world (Kovel, Reference Kovel1999, p. 7) served as instruments for profit, while within neoliberalism, natural resources were viewed as “elements of constant capital in capitalist production” (Vlachou, Reference Vlachou2004, p. 929). Unrestricted access to these resources facilitated their commodification and profit generation at the expense of resource depletion (Bumpus & Liverman, Reference Bumpus and Liverman2008). In that matter, climate change has emerged as a major “demand for innovation far more pervasive and powerful than any environmental programme” (Fri, Reference Fri2003, p. 72). Projections indicated that, indeed, by 2030, “fossil fuels would still be needed during the interim period” (Häfele et al., Reference Hafele, Anderer, McDonald and Nakicenovic1981, p. 28), a prediction substantiated by the continued rise of greenhouse gas emissions from 1990 to 2019 (UNEP, 2020).

This paper is structured as follows: Section 2 converges narrative analysis applied to climate change and systematic literature review methodology. Section 3 builds an initial mapping of climate narratives since the 1960s, and Section 4 provides a discussion and presents the conclusion.

Narrative analysis dynamics in climate change: a starting framework

“When people advocate for a policy, they tell a story, a narrative” (Laird, Reference Laird2022, p. 2). I agree with Smith and Monforte (Reference Smith and Monforte2020) that narrative is a helpful resource for providing a structure and a framework serving as a means to build cultural and social relations. It serves as a fundamental basis for connecting events, cycles, and phenomena, providing guidance or guidelines for action (van der Leeuw, Reference van der Leeuw2020). Indeed, “narratives are one of the primary ways in which cultural ideologies are taught, preserved and perpetuated” (Garcia Rodriguez, Reference Garcia Rodriguez, Tettegah and Garcia2016, p. 125). A narrative can be unpacked into three key elements that form the core of this resource. According to Ntinda (Reference Ntinda and Liamputtong2019), these are temporality, sociality, and place. Hence, the order of events (Connelly & Clandinin, Reference Connelly and Clandinin1990), their mutual influence (Elliott, Reference Elliott2005; Polkinghorne, Reference Polkinghorne1988) and the boundaries of the space, regardless of whether they are physical or not (Connelly & Clandinin, Reference Connelly and Clandinin1990), reflect the complex nature of a narrative. Thus, “through narrative, we learn to understand the meanings and significance of the past as incomplete, tentative and revisable according to contingencies of present life circumstances” (Ellis, Reference Ellis2004, p. 30).

The narratives about climate change since the 1970s are filled with complexities. They highlight a disruptive problem that challenges the established order. The growing academic literature has examined climate change narratives, focusing on power dynamics, their repercussions, and their influence on decision-making processes (Bäckstrand & Lövbrand, Reference Bäckstrand and Lövbrand2007; Barca, Reference Barca2011; Bergman & Janda, Reference Bergman and Janda2021; Bushell et al., Reference Bushell, Buisson, Workman and Colley2017; Hinkel et al., Reference Hinkel, Mangalagiu, Bisaro and Tàbara2020; Liverman, Reference Liverman2009). For instance, Liverman (Reference Liverman2009) identified the narrative of “climate change as an investment opportunity.” Bushell et al. (Reference Bushell, Buisson, Workman and Colley2017) structured climate narratives based on their effectiveness against climate change, i.e., “end of the world,” the “Al Gore narrative,” and “green living,” and those that impede such efforts, i.e., “debate and scam,” and the “carbon fuelled expansion.” Laird (Reference Laird2022) exposed the inefficiency of the “Save the Earth!” narrative by analysing its decarbonisation goal. Barca (Reference Barca2011) and Bergman and Janda (Reference Bergman and Janda2021) argued that the current “modern economic growth” narrative overshadows all other climate narratives. According to Barca (Reference Barca2011), two critical factors contribute to this: the establishment of private ownership and the energy transition. Here, liberalised markets and private sector involvement prioritise economic efficiency and growth over “planetary boundariesFootnote 1 ,” or social justice.

In accordance with the stated research objective, I contend that the integration of narrative analysis (Elliott, Reference Elliott2005; Kulaeva, Reference Kulaeva2025; Ntinda, Reference Ntinda and Liamputtong2019; Polkinghorne, Reference Polkinghorne1988; Smith & Monforte, Reference Smith and Monforte2020) and systematic literature review (Moher et al., Reference Moher, Liberati, Tetzlaff and Altman2009; Page et al., Reference Page, McKenzie, Bossuyt, Boutron, Hoffmann, Mulrow, Shamseer, Tetzlaff, Akl, Brennan, Chou, Glanville, Grimshaw, Hróbjartsson, Lalu, Li, Loder, Mayo-Wilson, McDonald and Moher2021) is essential for the construction of a comprehensive map of climate narratives. Notably, narrative is conceptualised both as a methodological instrument (Smith & Monforte, Reference Smith and Monforte2020), which enables a critical examination of the framing and understanding of climate change over time (Krauss et al., Reference Krauss, Bremer, Wardekker, Marschütz, Baztan and Charlotte2019). This methodological approach aids in the identification of recurring themes and situates these narratives within broader theoretical and historical contexts. On the other hand, the systematic literature review provides a structured and transparent framework for the identification, selection, and evaluation of relevant literature, thereby facilitating an assessment of what has been articulated regarding climate change and how it has been narrated. However, it is important to note that, in addition to the Web of Science database, other references cited in this paper were also consulted to ensure a broader and more comprehensive understanding of the field of climate change narratives. Accordingly, supplementary materials were examined, including review articles, project reports, policy documents, activist materials, and other original research publications from the 1960s to the present. This process contributed to the development of an evolutionary map of climate change narratives which, by complementing the systematic literature review (potentially limited in scope), highlighted that the study of climate change narratives is an emerging and inherently interdisciplinary field. The body of literature has only begun to consolidate in recent decades, reflecting the growing social and academic attention devoted to how climate change is framed, communicated, and understood.

In fact, the review followed a structured process comprising four key stages: identification, selection, eligibility, and inclusion. The primary database consulted was Web of Science, while Google Scholar was employed as a complementary source to enhance coverage and capture potentially overlooked publications. The initial Boolean search strategy utilised the terms “climate change” AND “narratives,” resulting in a total of 2,116 records published between 1990 and 2025. This initial corpus included a diverse array of studies addressing related themes such as denialism, climate anxiety, adaptation and mitigation strategies, disaster risk reduction, urbanisation, migration, and the gendered dimensions of climate change. All 2,116 records were screened for relevance to the study’s objective: to construct a comprehensive map of climate change narratives since the late 1960s from a narrative perspective (Ellis, Reference Ellis2004; Freeman, Reference Freeman2015; Ingram et al., Reference Ingram, Ingram and Lejano2019; Smith & Monforte, Reference Smith and Monforte2020). At this stage, duplicates and studies that did not substantively address climate change in narrative terms were excluded. A secondary Boolean search employing the more specific term “climate change narratives” identified just over 100 records.

The screening stage of both the first and second searches identified 118 articles, which were retained for further consideration. The studies were evaluated using strict inclusion criteria to ensure alignment with the research objective and the adoption of a narrative approach to climate change, thereby facilitating the mapping of the development and evolution of climate change narratives from a narrative perspective. Eligible works were required to (i) explicitly analyse climate change through a narrative framework, (ii) contribute to the mapping of the development and evolution of climate change narratives, and (iii) provide conceptual or empirical insights that are directly relevant to the research objective. Studies that focused solely on public perceptions, technical assessments, policy instruments, and similar topics without a narrative analytical lens were excluded. After applying these criteria, 34 articles were included in the final sample. These works provided the most direct, detailed, and conceptually relevant perspectives on climate narratives, thereby serving as the empirical basis for the analysis presented in this study. Although this review offers a substantial and structured mapping of climate change narratives (see Figure 1, p. 20), I acknowledge that it does not encompass all possible academic contributions – particularly those addressing climate change denial narratives – which should be explored further in future research.

Figure 1. Time diagram with the main identified climate narratives. Source: author’s own work.

Building on this corpus, a narrative analysis approach (Ellis, Reference Ellis2004; Arnold, Reference Arnold and Arnold2018; Ntinda, Reference Ntinda and Liamputtong2019; Smith & Monforte, Reference Smith and Monforte2020) employed in this study involved identifying narrative elements and thematic patterns across different time periods and socio-political contexts. Through this process, climate change narratives were mapped, contextualised historically and situated within the key categories that narrative analysis offers: temporality, sociality and place (Ntinda, Reference Ntinda and Liamputtong2019) through Figure 1 (p. 20). Following this, my historical reconstruction of climate narratives strengthens the usability of narrative analysis while providing an initial mapping of climate narratives and facilitating a critical examination of contemporary decision-making processes and practices, while highlighting the necessity for further narrative study of climate change.

Climate change narratives: compiling the history

This section undertakes the task of constructing a historical and evolutionary overview of the emergence of key narratives on climate change, specifically those that acknowledge it as an undeniable reality. This focus is essential not only due to the scope of the analysis but also because denialist narratives detract from efforts to address climate challenges by diverting attention and undermining progress (Shue, Reference Shue2023). Such narratives reject empirical evidence (Farmer et al., Reference Farmer, Cook, Farmer and Cook2013) and erode trust in scientific institutions (Mishra, Reference Mishra, Sarkar, Bandyopadhyay, Singh, Eds. and iski2024), among others. While the influence of denialist narratives is widely acknowledged, this analysis aligns with the academic consensus (Oreskes, Reference Oreskes2004) that meaningful solutions must be grounded in the recognition of climate change and its impacts (Bretter & Schulz, Reference Bretter and Schulz2023; Goldberg et al., Reference Goldberg, van der Linden, Maibach and Leiserowitz2019).

Here, I argue that having a map of narratives is essential for two key reasons: 1) to place what the academic literature states in this regard; and 2) to identify how these climate narratives justify and guide actions. This leads to my second goal. I analyse the extent to which climate change narratives have not sufficiently integrated perspectives from territories and cultural contexts beyond the dominant Western geographies. Notwithstanding the inherent complexity of addressing the full breadth of these narratives, the present study seeks to identify and examine the most significant climate narratives. In doing so, it aims to establish a foundational framework for academic inquiry into this subject since the 1960s. This framework is intended not only to inform and guide future research but also to serve as a resource upon which policymakers may ground more informed and effective decisions. Furthermore, by drawing attention to the two major shortcomings illustrated in the map (see Figure 1, P. 20), the study underscores the necessity of ensuring that such decisions are oriented towards greater climate justice.

The ongoing discourse surrounding climate change is intricately linked to the finite nature of Earth’s resources. This relationship was first articulated in the 1972 report by the Club of Rome, The Limits to Growth, which primarily examined the rapid depletion of natural resources and their limited availability. By employing systems thinking, The Limits to Growth illustrated how growth in one sector can instigate chain reactions throughout the entire system. The report underscored that human activities and natural resources exist within a closely interrelated framework, wherein interventions in one area may yield unintended consequences in another. In contrast to isolated analyses of population or industry, The Limits to Growth highlighted the necessity of considering the feedback mechanisms and interdependencies that govern global sustainability.

Nonetheless, years earlier, Neo-Malthusians were already arguing about the limited availability of these resources, linking them to food supply and growth. Paul R. Ehrlich’s (Reference Ehrlich1968) Population Bomb, as one of the classic examples of neo-Malthusian thought, opened a challenging discussion about the fear of overpopulation and its climatic consequences for securing food production. In the 1960s, two key works – Our Synthetic Environment and Silent Spring – profoundly influenced Western, particularly American, society, with the latter serving as a catalyst for the environmental movement (Zimmerman et al., Reference Zimmerman, Callicott, Sessions, Warren and Clarck2001). During this period, concerns arose about the use of chemicals (Bookchin, Reference Bookchin1962), agricultural chemical mutagens (Carson, Reference Carson1962), the impacts of nuclear weapons and radiation (Ayres, Reference Ayres1965), and the growing challenge of energy acquisition (Hardin, Reference Hardin1968), fostering a pervasive sense of impending catastrophe, or “the collapse is imminent” (Bevan et al., Reference Bevan, Colley and Workman2020). During this time, factors such as droughts, resource depletion, biodiversity loss, food shortages and industrial pollution were exacerbating the ecological crisis, where the sense of the “Looming Climate Catastrophe” (Moscato & Valencia, Reference Moscato and Valencia2023) or “apocalyptic environmentalism” (Kulaeva, Reference Kulaeva2024) started to emerge but became consolidated after the 2000s. Following the same line of argument, “claims in ecological disaster narratives that ‘time is running out’” (Fagan, Reference Fagan2017, p. 7), that we are approaching a ‘tipping point,’ and that we must ‘act now’ (Fagan, Reference Fagan2017, p. 7) invoked the urgency of climate change or the ‘eco-apocalypse’ narrative through The Day After Tomorrow in 2004 by Roland Emmerich (Joyce, Reference Joyce2024), and An Inconvenient Truth featured by former Vice-President Al Gore (Smith & Howe, Reference Smith and Howe2015).

After Our Synthetic Environment, Murray Bookchin not only criticised the capitalism of his time but also advanced the idea of post-scarcity as “not a cheap abundance of affluence that blunts our sensibility to rational needs” (Bookchin, Reference Bookchin1978, p. 90). He further emphasised the intrinsic link between ecological community and social life, i.e., social ecology, envisioning that “if the ecological community is ever achieved in practice, social life will yield a sensitive development of human and natural diversity, falling together into a well-balanced harmonious whole” (Bookchin, Reference Bookchin1978, p. 98). Interestingly, Silent Spring by Rachel Carson (Reference Carson1962) focused on the dangers of pesticides, particularly DDT.Footnote 2 Carson highlighted not only the extent to which human activity disrupts natural systems but also the importance of preventing ecological harm in everyday environments where humans, animals and plants coexist.

Going back to the late 1960s, ecofascismFootnote 3 as a political orientation gained momentum during this period (Camus, Reference Camus and Sedgwick2019) and also embraced the idea of an ecological crisis. For instance, the Groupement de Recherche et d’Études pour la Civilisation Européenne (GRECE) emerged during this time, in 1969 (Taguieff, Reference Taguieff1993). Nonetheless, even earlier, Nazi Germany’s naturalism and nationalism sharply delineated who was deemed worthy of inhabiting the planet. Similarly, Mussolini’s initiative to ruralise Italy through pro-countryside rhetoric, termed “internal colonialism” (Caprotti, Reference Caprotti2014), exemplified foundational ecofascist ideologies. During the late 1970s, Bookchin (Reference Bookchin1978, p. 90) stated that “to utilize ecological dislocations as a means for reverting to an “ethics” of crass egotism, to build a “strategy” of self-sustenance on the myth of a stingy nature that faces depletion of its bounty, to elicit a meanness of spirit on the presumption of “scarcity” is a horrendous mockery of ethics, nature and even the traditional concept of scarcity as a stimulus to techological progress …[…]… Eco-fascism absolutizes the existing sensibility and concept of need all the more to preserve an ethics based on self-preservation and interest, a sensibility it ironically shares with Mam’s own notion of the “expansion of needs.” Nonetheless, the rhetoric of ecofascism persisted and was later incorporated into what scholars identify as “authoritarian environmentalism”Footnote 4 (Beeson, Reference Beeson2010; Gverdtsiteli, Reference Gverdtsiteli2023), reflecting the potential legacy of totalitarian regimes. According to Gverdtsiteli (Reference Gverdtsiteli2023), this phenomenon poses a serious threat to Western democracies in light of the “tragedy of the commons” (Hardin, Reference Hardin1968).

During those years, the scientific community intensified its efforts to monitor environmental changes, elevating environmental issues to a prominent position on the political agenda. These changes were not only the result of natural forces but were significantly influenced by human activities (Nordhaus, Reference Nordhaus1975; Schneider, Reference Schneider1975). It was the time when 1969’s Making of a Counter Culture by Theodore Roszak (Reference Roszak1995) inspired Schumacher’s Small is Beautiful in Reference Schumacher1973, contextualised within the 1970s oil shocks and the relentless exploitation of natural resources. Indeed, the oil crises were described as “one of the few genuine economic calamities” (Schelling, Reference Schelling1979, p. 6), leading to skyrocketing inflation, an increase in prices beyond imagination, and economic and energy implications (Schelling, Reference Schelling1979; Häfele et al., Reference Häfele, Barnert, Messner, Strubegger and Anderer1986; Jacobs, Reference Jacobs2022). Scholars reported the negligent use and burning of fossil fuels (Cooper, Reference Cooper1978; Keeling, Reference Keeling1970; Schneider, Reference Schneider1975). These decades are often perceived as a moment of rupture, where modern capitalism, significant historical events, and economic transformations clashed with societal perceptions of sociocultural and political developments. Scholars measured these dynamics, identifying an incipient crisis of values by the early 1980s (Inglehart & Baker, Reference Inglehart and Baker2000).

Demands to reconsider the neoliberal framework emerged from the 1972 “Save the Earth” mission and the “Deep Ecology”Footnote 5 (Naess, Reference Naess1973), influenced by the 1962 Silent Spring and the Gaia Hypothesis Footnote 6 coined by James Lovelock and by Lynn Margulis in the late 1970s. Scholars claimed that the neoliberal framework, shaped by free-market fundamentalism, lacked the capacity to address environmental challenges (Vlachou, Reference Vlachou2004). The “consequences of energy choices” (Hayes, Reference Hayes1977, p. 25), the privatisation of water (Bakker, Reference Bakker2005), and the exploitation of common resources (Perkins, Reference Perkins2017) have come at the cost of ecological impacts. If, for the capitalist system, “the ‘goods’ of the world” (Kovel, Reference Kovel1999, p. 7) were an instrument for profit, for neoliberalism, natural resources were the “elements of constant capital in capitalist production” (Vlachou, Reference Vlachou2004, p. 929). Unrestricted access to them enabled their commodification and profit at the cost of resource depletion (Bumpus & Liverman, Reference Bumpus and Liverman2008). It has become essential to preserve the environment and to counteract the effects of burning fossil fuels (Hafele et al., Reference Hafele, Anderer, McDonald and Nakicenovic1981). Even though the 1972 Stockholm Conference already emphasised the importance of preserving natural resources and the environment “for the benefit of present and future generations” (Sohn, Reference Sohn1973, p. 456). During this time, Keeling (Reference Keeling1970) showed that CO2 levels from fossil fuels considerably impact the climate. Nordhaus, Reference Nordhaus1975) and Schneider (Reference Schneider1975) connected global warming and CO2 emissions, stating that to maintain climate variations within 2°C or 3°C (Nordhaus, Reference Nordhaus1975). Contrarily, global warming will surpass the natural climate variability level (Cooper, Reference Cooper1978). The increasing trend of CO2 emissions has started to be an alarming issue (Richards, Reference Richards1986), leading to the unprecedented “two-degree target time bomb” (Shaw, Reference Shaw2016, p. 4). Climate change emerged as a major “demand for innovation far more pervasive and powerful than any environmental program” (Fri, Reference Fri2003, p. 72). Projections indicated that even in 2030 “fossil fuels would still be needed during the interim period” (Häfele et al., Reference Hafele, Anderer, McDonald and Nakicenovic1981, p. 28), and in fact, GHGs continued to rise from 1990 to 2019 (UNEP, 2020).

Nevertheless, the technocratic perspective perceived technology as a progressive and modern tool. Technology became part of the solution – the way to be inside the Technocene – but outside nature itself. The same logic that Jackson (Reference Jackson2015, p. 481) found with the “glacier-ruins narrative,” which normalises “landscapes without glaciers and dominates the ice with metaphors of loss and ruin over previous narratives such as wild and sublime. This narrative narrows the range of unknowable, limitless futures into a certain tomorrow without ice and perpetuates overall fatalism – that is, reductionism – in the face of climatic changes.” Nonetheless, returning to the “technological insurance” (Fulkerson et al., Reference Fulkerson, Judkins and Sanghvi1990), it served as a unifying force for a sustainable and harmonious global future. Indeed, the blind optimism in technology was widely accepted (Peccei, Reference Peccei1979), along with the belief that significant capital investment would be necessary to develop new energy infrastructures (Hayes, Reference Hayes1977). Schelling (Reference Schelling1979) anticipated that technological advancements would transform and redefine the very nature and use of energy.

Notably, energy efficiency was proposed as a solution to address “both global cooling (in the 1970s) and global warming (in the 1990s)” (Randalls, Reference Randalls, van Munster and Sylvest2016, p. 146). Technology has been characterised as “an index of capital accumulation, privileged resource consumption, the displacement of both work and environmental loads” (Malm & Hornborg, Reference Malm and Hornborg2014, p. 3). Interestingly, the technocene turned out to be the complete redefinition of the anthropic perimeter (Cera, Reference Cera2017, p. 243). Here, the voices of eco-feminism and eco-Marxism were overshadowed by the eco-modernisation (EM) narrative (Kreikebaum, Reference Kreikebaum, Kreikebaum, Seidel and Zabel1994; Jänicke, Reference Jänicke2008; Mol et al., Reference Mol, Spaargaren and Sonnenfeld2013), and the overarching “sustainable development” emerged within the 1987 Brundtland Report, where “a new era of economic growth – growth that is forceful and at the same time socially and environmentally sustainable” (UN General Assembly, 1987, p. 14) was imperative. As Barca (Reference Barca2011, p. 1309) identified, sustainable development was depicted as the shift “from the constraints of ‘natural’ conditions, thanks to new technologies and social values.”

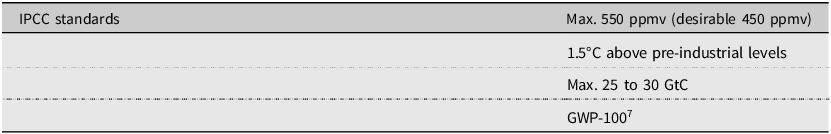

Climate change has been framed through the lens of technical assessment (IPCC, Reference Houghton, Meira Filho, Callander, Harris, Kattenberg and Maskell1995). Efforts to reduce global emissions and “keeping atmospheric concentrations below 500 ppmv” (IPCC, Reference Houghton, Meira Filho, Callander, Harris, Kattenberg and Maskell1995, p. 13) or within a range of 25 to 30 GtC (IPCC, Reference Shukla, Skea, Calvo Buendia, Masson-Delmotte, Pörtner, Roberts and van Diemen2019) emerged as the “technical solution” (Hardin, Reference Hardin1968) to “guide limitation and reduction efforts” (FCCC, 1996, p. 10). UNFCCC Articles 2 and 3 have etched a significant chapter in these efforts. The recurring IPCC reports highlighted the anthropogenic nature of global warming, and the unyielding imperatives were to cap the temperature by 1.5°C to 2°C (Sanford et al., Reference Sanford, Frumhoff, Luers and Gulledge2014) and to stabilise CO2 emissions at 550 ppmv (see Table 1). Measuring the impact of carbon footprints in ppmv or in terms of atmospheric temperature has become standard practice for setting climate benchmarks and defining the steps to reach net zero emissions by 2050 (Waisman et al., Reference Waisman, Bataille, Winkler, Jotzo, Shukla, Colombier, Buira, Criqui, Fischedick, Kainuma, La Rovere, Pye, Safonov, Siagian, Teng, Virdis, Williams, Young, Anandarajah and Trollip2019). What Table 1 shows in the following is the extent to which IPCC standards may set numerical limits that can shape and promote climate action on a global scale. These benchmarks are undoubtedly valuable for setting internationally recognised targets. However, by maximising these limits, climate action becomes generalised, which risks obscuring two crucial dimensions. First, it fails to fully consider the impact on regions most severely affected by climate change, where vulnerabilities are often greatest. Second, it overlooks the historical responsibility that underpins the persistent asymmetries between the Global North and the Global South. Therefore, while global standards are necessary for coordination, they must be critically examined to ensure that they do not inadvertently reinforce existing inequalities in the distribution of both climate burdens and responsibilities.

Table 1. IPCC’s measurement standards

Source: Author’s own work.

This prevailing trend of economic growth, coupled with technological advancements, was critically examined through an ecofeminist perspective to address social inequalities that contribute to ecological degradation (McMahon, Reference McMahon1997). Through the logic of the ecofeminist perspective, it was widely acknowledged that:

“Practically everybody knows that today the two most immediate threats to survival are overpopulation and the destruction of our resources; fewer recognise the complete responsibility of the male System, in so far as it is male (and not capitalist or socialist) in these two dangers; but even fewer still have discovered that each of the two threats is the logical outcome of one of the two parallel discoveries which gave men their power over fifty centuries ago: their ability to plant the seed in the earth as in women, and their participation in the act of reproduction” (d’Eaubonne, Reference d’Eaubonne, Marks and de Courtivron1980, p. 66)

In Barbara Gates’s (Reference Gates1996, p. 8) words, “this excerpt, the one most quoted from d’Eaubonne, directly joins women and the environment, in this case through reproduction. D’Eaubonne, as all acknowledge, also coined the word ecoféminisme.” What is remarkable is the extent to which eco-feminism and eco-Marxist perspectives examine the extent to which “women’s societal roles – such as caregiving for children and other dependents, domestic labour and low-paid or low-status employment – are shaped by existing social and economic structures” (Buckingham, Reference Buckingham2004, p. 147). These same structures simultaneously constrain women’s opportunities and expose them to environmental harms. From an eco-Marxist perspective, the endless growth driven by the demand for raw materials was seen as a “barrier posed by capitalist social relations that prevent society from taking full advantage of its natural resource base” (Perelman, Reference Perelman1979, p. 84). Further, the idea of progress based on technological advancement resulted in “the global displacement of work and environmental burdens to social categories with less purchasing power” (Hornborg, Reference Hornborg2015, p. 65).

EM was understood as one of the preventive solutions for “end-of-pipe treatment.” Within the context of economic expansion and market systems, it started to be seen as a viable response to the climate threat intended to be “the socialization of environmental governance within neoliberal market logic” (Low & Boettcher, Reference Low and Boettcher2020, p. 2). The strong version of EM was oriented toward risk society and risk assessment strategic planning (Beck, Reference Beck1992), personifying the “politics of hazards” (Winner, Reference Winner1986). This approach emphasised the “green interpretation of governmentality” (Bäckstrand & Lövbrand, Reference Bäckstrand and Lövbrand2007, p. 127) and the need to address environmental risks through technological advancements. Climate change converged to be “a vehicle for its very innovation” (Hajer, Reference Hajer1995, p. 35). The redefinition of the state’s role within the EM perspective (Jänicke, Reference Jänicke2008; Mol et al., Reference Mol, Spaargaren and Sonnenfeld2013) displayed neoliberal practices, environmentally friendly technologies, and the move towards trade liberalisation to address environmental issues (Grist, Reference Grist2008).

The idea of resource efficiency linked to waste optimisation and economic growth began to shape the technocratic transformation. It is no coincidence that during the emergence of the EM, the features that it appealed to were addressed to encompass “(1) Humankind’s shared economic destiny; (2) The new globalisation and diplomacy; (3) The looming climate catastrophe” (Moscato & Valencia, Reference Moscato and Valencia2023, p. 1). The “accumulation by dispossession” (Bumpus & Liverman, Reference Bumpus and Liverman2008) of the “carbon-fuel expansionism” (Bushell et al., Reference Bushell, Buisson, Workman and Colley2017) advocated for economic growth. Hence, emissions, resource use and energy efficiency “have themselves become big business” (Hajer, Reference Hajer1995, p. 32). No wonder why Beck (Reference Beck2010, p. 263) categorised carbon emissions as “the measure of all things.” Climate parameter metrics started to use carbon dioxide reference (CO2e). The time horizon of global warming potential (GWP) over 100 years (Lashof, Reference Lashof2000) was converted to the international standard for the GHGs after the 1994 IPCC Special Report and was used to meet the 1997 Kyoto Protocol targets. Nordhaus’s (Reference Nordhaus1991) analysis of the economic impact of CO2 under a 3°C global warming scenario highlighted the need to moderate the strategies to address climate change due to the economic costs that may undermine positive environmental outcomes.

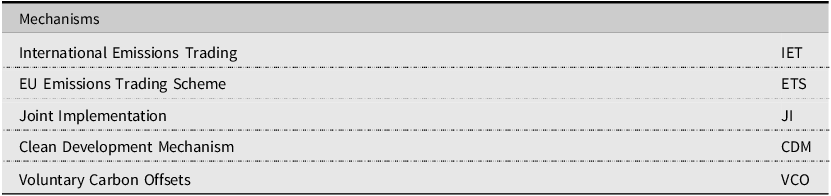

By treating GHGs as a tradable commodity, environmental protection was redefined as “a management problem that can be addressed by ‘modernizing’ the economy” (Taylor, Reference Taylor2013, p. 27). The climate became no longer “a free good” (Christoff, Reference Christoff1996, p. 482) but “a public good” (Hajer, Reference Hajer1995, p. 28). The market-oriented approach gained significance through the commodification of CO2 emissions, which were regarded as a flexible and cost-effective market solution (see Table 2) under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. This facilitated climate change mitigation and adaptation strategies. Additionally, the 1997 Kyoto Protocol explicitly operationalised the UNFCCC framework by establishing binding emission reduction targets for developed countries. In this context, the UNFCCC in 1992 at the Earth Summit in Rio de Janeiro introduced the principle of “common but differentiated responsibilities” (implemented through various mechanisms of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol), acknowledging that the responsibilities of industrialised countries differ based on their historical contributions to emissions and levels of economic development.

Table 2. The organisation of carbon credits under the 1997 Kyoto Protocol

Source: Author’s own work.

The mechanisms that emerged from this market-oriented approach – including international emissions trading, the EU Emissions Trading Scheme, joint implementation, the clean development mechanism, and voluntary carbon offsets – embody the same tensions highlighted in Table 1. While these instruments were designed to provide flexible and cost-effective tools for mitigation and adaptation, their emphasis on efficiency and commodification risks reproducing the limitations of universal technical solutions. In particular, they often fail to address issues of climate justice and historical responsibility, as their global application tends to obscure the disproportionate vulnerabilities of certain regions and marginalise non-Western narratives that remain underrepresented in the literature. By privileging economic instruments over socio-cultural and political specificities, these mechanisms illustrate how the pursuit of planetary-scale objectives can inadvertently reinforce existing asymmetries between the Global North and the Global South.

The initial distinction between mitigation and adaptation strategies was largely based on a country’s level of development (Schipper, Reference Schipper2006; Swart & Raes, Reference Swart and Raes2007). Mitigation efforts primarily targeted reducing GHG and methane emissions (Ayers & Huq, Reference Ayers and Huq2009), improving air quality (Bernauer & Koubi, Reference Bernauer and Koubi2009), adopting renewable energy (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Chou and Zhang2019) and advancing decarbonisation (Lechtenböhmer & Luhmann, Reference Lechtenböhmer and Luhmann2013). In contrast, adaptation strategies emphasised water management (Richter et al., Reference Richter, Mathews, Harrison and Wigington2003), coastal adaptation planning (Nalau et al., Reference Nalau, Preston and Maloney2015), biodiversity protection (Halpin, Reference Halpin1997), and agricultural resilience (Diallo et al., Reference Diallo, Emmanuel and Owusu2020). However, scholars have noted that the polarisation between these approaches often hampers cohesive climate action (Schipper, Reference Schipper2006; Ayers & Huq, Reference Ayers and Huq2009; Swart & Raes, Reference Swart and Raes2007). After the 1997 Kyoto Protocol’s “top-down” approach, during the 2011 Durban negotiations,“it was agreed that a new framework for action would be adopted in 2015” (Ciplet & Roberts, Reference Ciplet and Roberts2017, p. 153).

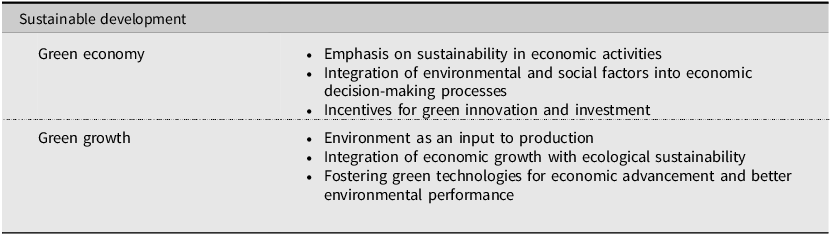

During this time, the emergence of the AnthropoceneFootnote 8 (Crutzen & Stoermer, Reference Crutzen and Stoermer2000) paved the way for forming the Anthropocene Working Group; first, to determine a “crossed epoch-scale boundary” (Zalasiewicz et al., Reference Zalasiewicz, Williams, Haywood and Ellis2011) and, second, to trace an “unapologetically anthropocentric” (LeCain, Reference LeCain2015) view of the human impact on the Earth. In parallel, two emerging trends remained; since the 1987 Brundtland Report, there has been an emphasis on eradicating poverty and promoting sustainable living, along with the fact that “future CO2 emission levels will depend primarily on the total energy consumption and the structure of the energy supply” (Nakicenovic et al., Reference Nakicenovic, Alcamo, Davis, de Vries, Fenhann, Gaffin, Kermeth, Griibler, Yong Jung, Kram, Lebre La Rover, Michaelis, Mori, Morita, Pepper, Pitcher, Price, Riahi, Roehrl and Dadi2000, p. 243). Amidst the peak of the 2008 financial crisis, on the one hand, the concept of the green economy emerged (Georgeson, Maslin & Poessinouw Reference Georgeson, Maslin and Poessinouw2017) through a Global Green New Deal report commissioned by the UNEP in 2009, while on the other hand, The Stern Review was gaining momentum. The Economics of Climate Change: The Stern Review was commissioned to produce a report for Prime Minister Tony Blair and the Chancellor by autumn 2006. Stern (Reference Stern2008) focused on three main areas: (1) the economic implications of transitioning to a low-carbon economy, with attention to medium- and long-term effects on policy design, institutional frameworks and action timelines; (2) the effectiveness of adaptation strategies in mitigating climate impacts; and (3) the specific consequences for the United Kingdom in relation to its existing climate policies and objectives.

All in all, this encapsulates the intrinsic dynamic of the Anthropocene, which “proposes an epic planetary agency for humanity that is material, symbolic and virtual” (Yusoff, Reference Yusoff2013, p. 781). Concurrently, the annual Ministerial Council of the Organisation for Economic Co-operation and Development (OECD) in 2009 adopted a Declaration on Green Growth (Park, Reference Park2013). The notion of a green economy and the concept of green growth gained widespread acceptance. While a green economy, with an emphasis on the low-carbon economy (Xu et al., Reference Xu, Chou and Zhang2019), was thought to contribute to economic recovery (OECD, 2009) and the reduction of poverty (Barbier, Reference Barbier2016), green growth emerged as a more feasible solution for “eco-efficient technical progress” (Jänicke, 2012, p. 20), indeed proposed for technological innovation (Choi & Han, Reference Choi and Han2018), emission reduction processes through green finance and carbon taxes (see Table 3). It was conceived as the only way (The World Bank, 2012) to reconcile economic growth processes with “environmental sustainability at low cost” (Toman, Reference Toman2012, p. 2), achieving it “without large sacrifices of economic growth” (Smulders et al., Reference Smulders, Toman and Withagen2014, p. 424) and making it “resource-efficient, cleaner and more resilient” (Hallegatte et al., Reference Hallegatte, Heal, Fay and Treguer2012, p. 3). This meant fostering the concept of sustainable development that had become insufficient for global goals (Park, Reference Park2013).

Table 3. Outlining some main aspects of green economy and green growth

Source: Author’s own work.

For many scholars, the green economy was nothing more than an anachronism (Barbier, Reference Barbier2012), an oxymoron (Brand, Reference Brand2012), and a missed opportunity for a paradigm shift. The overlap of both concepts and the lack of differentiation (Brand, Reference Brand2012) were “left deliberately imprecise” (Georgeson et al., Reference Georgeson, Maslin and Poessinouw2017, p. 7). Further, “the resuscitation of the (green economy) concept” (Benson et al., Reference Benson, Fairbrass, Lorenzoni, O’Riordan and Russel2021, p. 14) was related to the 1970 Limits to Growth, the ideas of circular economy, and the concept of sustainable development. The green economy perspective was problematised with the re-emergence of degrowth, which questioned the traditional economic path of constant growth (Demaria et al., Reference Demaria, Schneider, Sekulova and Martinez-Alier2013). DegrowthFootnote 9 (“décroissance” in French, coined by social philosopher André GorzFootnote 10 ) has been widely known since the 1970s and has become more popular within socio-political movements since 2008 (Demaria et al., Reference Demaria, Schneider, Sekulova and Martinez-Alier2013; Fournier, Reference Fournier2008), even though Serge Latouche (Reference Latouche2010; Reference Latouche2016), for instance, considered as a foundational thinker of degrowth, was already exploring the intersection of economics, anthropology, and decolonisation studies to dismantle the idea of growth since the late 1980s. Subsequently, it acquired a wider diffusion after various international conferences. Indeed, degrowth criticises the role of states that “gave away important national decisions (e.g., money supply) to markets and independent bodies (e.g., central banks), removing them from the realm of democratic choice” (Kallis et al., Reference Kallis, Kerschner and Martinez-Alier2012, p. 173), and the economic growth that is irreconcilable with sustainability principles (Hickel & Kallis, Reference Hickel and Kallis2019). At the same time, it considers the inclusion of citizens as a part of socio-political and environmental justice. It is a question of “replacing the consumer with the citizen” (Fournier, Reference Fournier2008), sustained by the deconstructing idea of worshipping the GDP (Latouche, Reference Latouche2010).

Degrowth dismantles EM related to technocratic management and criticises the green economy and growth (Demaria et al., Reference Demaria, Schneider, Sekulova and Martinez-Alier2013). Despite this, as was pointed out by Hinkel et al. (Reference Hinkel, Mangalagiu, Bisaro and Tàbara2020, p. 498), “both proponents of the green growth and degrowth narratives run the risk of “reducing the sustainability discussion to a question of metrics.” Additionally, the emergence of many different terms, such as “a-growth”Footnote 11 (Van den Bergh, Reference van den Bergh2017; van den Bergh & Kallis, Reference van den Bergh and Kallis2012) or “post-growth”Footnote 12 (Schulz & Bailey, Reference Schulz and Bailey2014; van Woerden et al., Reference van Woerden, van de Pas and Curtain2023), means that there is no consensus on how to define alternatives, if any, recognising the current stagnation and the need to seek those approaches that will incorporate non-Western voices and represent marginalised territories.

Nevertheless, in light of the pressing need to reduce consumption, endless growth and reliance on fossil fuels, the degrowth narrative presents a counter-narrative to green growth (and the green economy), thereby underscoring a conflict of ideologies (Kulaeva, Reference Kulaeva2024). In this context, Naomi Klein’s This Changes Everything (2014) emerges as a significant critique of capitalism while stressing the necessity for climate justice. The book addresses the limited progress of international climate negotiations, particularly the shortcomings of the Kyoto Protocol and and the limited outcomes of the UNFCCC Conference of the Parties meetings in Copenhagen in 2009 and Durban in 2011, where expectations for decisive global action largely went unmet. As she aptly points out, “the influence wielded by the fossil fuel lobby goes a long way toward explaining why the sector is so very unconcerned about the non-binding commitments made by politicians at U.N. climate summits to keep temperatures below 2 degrees Celsius. Indeed, the day the Copenhagen summit concluded – when the target was made official – the share prices of some of the largest fossil fuel companies hardly reacted at all” (Klein, Reference Klein2015, p. 131). Naomi Klein contends that the structural imperatives of neoliberal capitalism – continuous growth, reliance on fossil fuels, and deregulated markets – present considerable challenges to the formulation of effective climate policy. She frames the climate crisis as inextricably linked to broader struggles for economic and social transformation.

One year later, the 2015 Paris Agreement’s “bottom-up” approach initiated the implementation of Nationally Determined Contributions (NDC) mechanisms and continued to reinforce the idea of keeping global warming preferably at 1.5°C and not striving to exceed 2°C, a principal that has been stressed since the 1970s. It appeared to be a synergy that became apparent with the introduction of the Sustainable Development Goals. The urgent need to reduce GHGs was declared the ‘battle for our lives’ (UNFCCC, 2019), while the emergence of the “Anthropocene” during the early 2000s (Crutzen & Stoermer, Reference Crutzen and Stoermer2000) was flagged as a race of utmost climatic urgency. Notwithstanding the longstanding urgency and increasingly severe consequences of climate change, it was not until COP28 in 2023 that fossil fuels were explicitly mentioned in the outcome text (Decision-/CMA.5) for the first time in the history of the United Nations Framework Convention on Climate Change (2023) negotiations:Footnote 13

“28. Further recognises the need for deep, rapid and sustained reductions in greenhouse gas emissions in line with 1.5°C pathways and calls on Parties to contribute to the following global efforts, in a nationally determined manner, taking into account the Paris Agreement and their different national circumstances, pathways and approaches:

d) Transitioning away from fossil fuels in energy systems, in a just, orderly and equitable manner, accelerating action in this critical decade, so as to achieve net zero by 2050 in keeping with the science.”

Indeed, the COP28 decision, reached by nearly 200 nations, calls for “transitioning away from fossil fuels,” marking a symbolic shift: fossil fuels, long the unacknowledged “elephant in the room,” have now been formally recognised as central to the climate crisis. However, it is important to note that the adopted language does not commit to a binding “phase-out” of oil, gas, and coal, which remains a contentious issue for many states and environmental observers. Thus, while “transitioning away from fossil fuels” has emerged as a key slogan influencing future public policy agendas, the implementation of this commitment will heavily depend on how national policies, financial flows, and regulatory frameworks interpret and enact the agreed wording.

The missing map of climate change narrative. Climate change, “The Measure of All Things”

Indeed, based on this historical analysis of the last sixty years of climate change narratives, I followed Cortazzi’s (Reference Cortazzi2001, p. 384) consideration, where narratives refer to this “social process or performance in action” that builds structures of knowledge and storied ways of knowing. The historical framework (see Figure 1, p. 20) I developed here allowed me to present the main narratives for each decade and assign an overarching paradigm to each of them. These narratives and their encompassing paradigms reflect three key aspects that are not clearly addressed in the academic literature:

First, each narrative has inherent limitations. Climate narratives function within the boundaries of their theoretical frameworks, shaped by their distinct perspectives, which render them incomplete in guiding action. No single narrative can fully capture the complexity of climate change; therefore, each must adapt to the evolving realities of the climate. Second, climate narratives are inherently limited by their own theoretical frameworks yet remain deeply interconnected. New narratives often emerge from earlier ones (see Figure 1, p. 20), forming a historical continuum that links them across time. This process reflects the three dimensions of narrative analysis identified by Ntinda (Reference Ntinda and Liamputtong2019): temporality, which traces the unfolding of narratives through time; sociability, which emphasises their relational nature; and space, which situates them within specific geographic and cultural contexts. Within Ntinda’s framework, the narrative map functions as an analytical tool that clarifies relationships among climate change narratives and reveals how representations of climate change have evolved over the past six decades. This analysis helps illuminate the structures and conditions that shape both responses and silences around climate action, thereby connecting directly to the study’s third observation.

Third, the “missing map of climate narratives” provides clear evidence of the extent to which existing climate narratives built through the academic literature have insufficiently incorporated perspectives from territories and sociocultural contexts outside dominant Western frameworks. This absence has resulted in the marginalisation of voices and experiences from non-Western geographies. As a consequence, the cultural and socio-political conditions that shape responses to climate change remain only partially represented, limiting the comprehensiveness and inclusivity of these narratives. Moreover, as Simon (Reference Simon2020, p. 188) observes, “the challenge lies in coming to grips with how the stories we can (but not necessarily should) tell in the Anthropocene relate to the radical novelty of the Anthropocene condition, about which no stories can be told.”

This provocation underscores the necessity of critically reassessing not only what constitutes a climate narrative but also the ways in which such narratives are constructed, circulated, and applied under diverse circumstances. Addressing this challenge requires expanding the narrative scope to include plural epistemologies, cultural contexts, and lived experiences, thereby ensuring that climate narratives more accurately reflect the complexity of a world profoundly shaped by climate change. These findings also correlate with the Blaxekjær & Nielsen (Reference Blaxekjær and Nielsen2015, p. 11), where they analyse “the narrative positions of the new political groups,” which “are aligned to the extent where they only represent two meta-narratives: bridge-building or upholding the North–South divide, which illustrates a less complex map or scenario.” I argue that the climate change narratives framed from the academic space reviewed in this manuscript undervalue, or more often ignore altogether, narratives that do not pertain to non-Western spaces. I suggest that the implementation of, for example, climate policies is hampered by the use of Western-made, Western-localised, and Western-owned narrative frameworks, particularly if the main umbrella narratives are “economistic techno-optimism, green capitalism, Green New Deal and degrowth,” identified by García-Olivares & López (Reference García-Olivares and López2021).

In this sense, my main claim is that narratives not created within Western topographies lack temporality, spatial context and, above all, sociability, following Ntinda’s (Reference Ntinda and Liamputtong2019) narrative definition. Further, I agree with Rodrigo-Alsina (Reference Rodrigo-Alsina2019, p. 108), claiming that “there is a struggle of opposing stories. However, this discursive war is not about big battles, but rather it is a guerrilla war of the alternative narratives against the hegemonic narratives.” This indicates that many climate change narratives may not be structured along a continuous timeline, are not anchored in identifiable locations, and are disconnected from the narratives surrounding them within Western frameworks. These findings are consistent with Rucavado Rojas and Postigo (Reference Rucavado Rojas and Postigo2025), whose main results identify “institutional and structural factors” that limit authors from the Global South from being nominated, selected, and thus contributing to the IPCC reports. Further, it is not a coincidence that even “the UN discourse on climate change portrays global warming as an external antagonistic force that coincides with human limitations, so defining mankind as a homogeneous social space” (Ivic, Reference Ivic2023, p. 22).

If so, here I introduce an additional layer of complexity; it is no wonder that my mapping (refer to Figure 1, p. 20) indicates that virtually all climate narratives are situated within Western geographies while claiming to encompass the entire globe. However, can this perspective genuinely represent spaces and places whose needs vary significantly and are shaped by unequal historical dynamics between the Global North and South? I observe a consistent trend of naturalising or treating the needs of the Global South as self-evident based on assumptions originating from the Global North. How can we address climate change if most of the world is not even represented in the narratives we narrate about climate change? For instance, if the world is constrained to two basic, standardised and overarching narratives (i.e., greening capitalism and degrowth), as reflected in Kulaeva (Reference Kulaeva2024), for example, and the rest of the world is not even represented, then how can we even think of aspiring to common climate governance, let alone solving the climate crisis?

I agree with Moore (Reference Moore2016, p. 164) that “we should attempt to respect the complex historical trajectories and shifting relations of the words and phenomena that fall under the broad term “cultural fix”: culture, society, ideology, hegemony, identity, generation, etc.,” meaning that if for the Anthropocene, it is the antropo – the substance that conforms the main cause of climate change – we may be overlooking the materiality that contains this antropo. I refer to the bonds between humans and nature that are eroded by the environment’s pervasive structural commodification, where, for instance, the Anthropocene narrative may potentially overlook the “dynamism of the social landscape” (Ingram et al., Reference Ingram, Ingram and Lejano2019). Hence, the starting point is the underlying assumption of nature being ontologically separated from humanity and subordinate to the imperatives of modernity or the “Westernocene” (San Román & Molinero-Gerbeau, Reference San Román and Molinero-Gerbeau2023). No wonder then why “traditional knowledge” (Williams & Hardison, Reference Williams and Hardison2013), Indigenous knowledge systems (Dorji et al., Reference Dorji, Rinchen, Morrison-Saunders, Blake, Banham and Pelden2024), Pacific Islands climate vulnerabilities (Farbotko & Lazrus, Reference Farbotko and Lazrus2012), and agricultural resilience to climate shocks in Africa (Ayinde et al., Reference Ayinde, Oyedeji, Miranda, Olarewaju and Ayinde2024), among others, have largely been overlooked under the dominant voices of Western climate narratives. As Krauß and Bremer (Reference Krauß and Bremer2020, p. 4) argue, “narratives about extreme weather events and changes in seasons, about droughts, floods, or biodiversity loss give a detailed insight into climate-related changes that are culturally meaningful.” Unsurprisingly, the dominance of Westernised perspectives in climate change narratives has marginalised other narrative forms. These alternative narratives – often deeply rooted in local knowledge systems and lived experience – hold significant potential for enriching our understanding of climate change (Alexander et al., Reference Alexander, Bynum, Johnson, King, Mustonen, Neofotis, Oettlé, Rosenzweig, Sakakibara, Shadrin, Vicarelli, Waterhouse and Weeks2011; Lejano, Tavares-Reager & Berkes, Reference Lejano, Tavares-Reager and Berkes2013; Rojas, Reference Rojas2016). However, their value is frequently obscured by the prevailing influence of the Anthropocene and Technocene frameworks, both of which are primarily shaped by the “investment opportunity” or the overwhelming paradigm of “Fossil Capitalism,” which continues the legacy of the “Great Acceleration” (Angus, Reference Angus2016).

Here, I do not intend to suggest that non-Western narratives are unrecognised; instead, I assert that the dominant climate narratives tend to focus more on broad guidelines for action than on the specificities of individual contexts. For instance, consider the case of the Inuit people of Eastern Baffin Island in the Arctic Ocean, as discussed in Lejano et al. (Reference Lejano, Tavares-Reager and Berkes2013); the case of the Indigenous minority communities, Basongora, in the Kasese district of Western Uganda, by Nsibambi and Akiiki (Reference Nsibambi and Akiiki2024); or the Māori indigenous perspectives and knowledge integrated through the Enviroschools Programme across Aotearoa New Zealand, analysed by White et al. (Reference White, Ardoin, Eames and Monroe2024). Nevertheless, this framework also refers to the scientific literature that advocates for decolonising climate change rhetorics, discourses, and narratives (Deranger et al., Reference Deranger, Sinclair, Gray, McGregor and Gobby2022; Plambeck, Reference Plambeck2020; Reed et al., Reference Reed, Alook and McGregor2024). The canonisation of certain narratives, such as green growth, has only obfuscated and displaced climate change’s vulnerability and inescapable influence on the most affected communities while remaining rooted in sustainable development paradigms (Kasztelan, Reference Kasztelan2017) that prioritise economic growth and technological solutions (Barbier, Reference Barbier2012; Brand, Reference Brand2012).

To illustrate these claims, I chose to delve into this aspect through a climate narrative of the UNFCCC regarding “common but differentiated responsibility.” This narrative embodies, at the very least, the need to represent non-Western topographies through the purpose of historical responsibility. Although the primary goal is to reduce GHGs, this climate narrative emphasises the historical responsibilities of developed countries and the future opportunities of developing countries. Furthermore, the “common but differentiated responsibility” narrative advocates for the distribution of climate burdens based on the principles of climate justice (Gajevic Sayegh, Reference Gajevic Sayegh2018), whose foundational principles (Caney, Reference Caney2012) are guided either by the “principle of equal sacrifices” or the “principle of equal emissions per capita,” where “developing countries are the victims of developed countries’ historic emissions. Their responsibility is to pull their people out of poverty and must therefore receive financial and technical support for their differentiated responsibility” (Blaxekjær & Nielsen, Reference Blaxekjær and Nielsen2015, p. 11). However, for both instances or principles, key factors such as equity and historical context influence the degree of responsibility for GHGs. For instance, the disparities between the Global North and South, particularly concerning resource use and allocation, intensify the challenge of how we treat equity and historical responsibility. This complexity is encapsulated in the narrative of ‘climate change as an investment opportunity’ (Liverman, Reference Liverman2009), where the market-based approach to trading carbon started to be seen as a crucial component “of a promising new ‘green economy’” (Böhm et al., Reference Böhm, Misoczky and Moog2012, p. 1618).

Despite the emphasis of the “common but differentiated responsibility” on equity and historical responsibility, which is essential in acknowledging historical disparities between the Global North and South, it operates within the parameters of the 1997 Kyoto Protocol. While the Kyoto Protocol laid the groundwork for differentiated commitments, it primarily focused on mitigation efforts through a top-down approach and market-based mechanisms such as emissions trading and the Clean Development Mechanism. These mechanisms, however, have often reinforced existing power imbalances by allowing developed nations to offset their emissions rather than fundamentally restructuring their economies or addressing more profound systemic inequalities. Furthermore, these agreements have reinforced specific geopolitical and economic disparities while advancing climate responsibility.

For instance, implementing market-based mechanisms, such as the EU Emissions Trading System (EU-ETS), has favoured industrialised nations with established economic infrastructures, reinforcing disparities rather than mitigating them (Böhm et al., Reference Böhm, Misoczky and Moog2012). I argue this through the Anthropocene narrative that Simon (Reference Simon2020) already stressed, indicating that the narratives we tell and relate about the Anthropocene are shaped by a modern Western way of conceiving history as a continuous, evolutionary process over time, where “historical understanding and modern historical time underlie Anthropocene narratives of all scales” (Simon, Reference Simon2020, p. 192). Importantly, the marginalisation of non-dominant and excluded narratives can be seen per se as “a symptom of ecological crisis” (Adams, Reference Adams2019). In the same vein, I argue that “acknowledging human impacts on the environment and the colonising practices that continue to contribute to contemporary socio-ecological issues exemplifies a critical approach…[…]… Such an approach problematises the meaning of place, connections to nature and, in some countries, colonial practices that have led to immense gains for some people, but often at the expense of other people, other species and ecosystems” (White et al., Reference White, Ardoin, Eames and Monroe2023, p. 15). For instance, “questions of indigeneity are much more complicated and demand a careful, long term, grounded and ethno-graphic engagement in post-colonial contexts” (Kumar, Reference Kumar2022, p. 7).

It is worth noting that “colonial logics of extractivism continue through neocolonial and development interventions post-WWII. The ecologically unequal exchange between the Global South and Global North, ongoing extractive capitalism, the imperial structures of global trade and domination in setting policies and ideologies – all work to maintain climate coloniality” (Sultana, Reference Sultana2022, p. 4). Colonialism, the extractivism inherent in Fossil Capitalism (Angus, Reference Angus2016), the emergence of “greening capitalism,” and the persistent legacy of imperialism are interlinked dynamics that continue to influence the global political economy of climate change. These processes are not merely remnants of history; they actively perpetuate systems of domination and dependency. They sustain global reliance on extractive industries and carbon-intensive infrastructures while legitimising these practices under the guise of progress, innovation and sustainability.

As Roos & Reccius (Reference Roos and Reccius2024, p. 313) observe, “the narrative has relevance and functions in a social context.” Within the realm of climate narratives, this statement is particularly salient, given that dominant climate change narratives framed within market-based logics – whether through technological solutions, neoliberal policy frameworks, eco-modernisation discourses, or market-oriented mitigation strategies (as illustrated in Figure 1) – are constructed and mobilised in ways that promise efficiency and growth while simultaneously obscuring the structural inequalities between the Global North and the Global South that underpin ecological breakdown. These discursive formations are situated within historically produced and persistently unequal socio-political and economic contexts, where systemic asymmetries entrench hierarchies of power, labour, and ecological exploitation. For instance, the results of Böhm et al., (Reference Böhm, Misoczky and Moog2012, p. 1617) confirm that “the role that carbon markets play in exacerbating uneven development within the Global South, as elites in emerging economies leverage carbon market financing to pursue new strategies of sub-imperial expansion.”

In effect, these climate change narratives may function to legitimise the continuation of extractive and exploitative practices under the guise of sustainability, green growth, or the green economy, thereby perpetuating what Sultana (Reference Sultana2022) describes as the coloniality of climate governance. This brings us back to my question: to what extent can we adequately represent spaces and places whose needs vary significantly and are shaped by unequal historical dynamics between the Global North and the Global South? Moreover, how can meaningful global climate action be envisioned if vast regions of the world remain excluded from the dominant narratives through which climate change is conceptualised and addressed? The omission of these perspectives is not a matter of oversight but reflects the structural power imbalances that shape knowledge production and circulation.

If narratives situated beyond Westernised epistemologies, places and territories are not incorporated, there is a substantial risk of overlooking forms of local knowledge and community-based approaches that have long demonstrated effectiveness in responding to climate impacts on the ground (Farbotko & Lazrus, Reference Farbotko and Lazrus2012). Such exclusions are not only epistemic but also political; they limit the scope of climate governance by privileging technocratic, market-based, and universalising solutions over place-specific strategies rooted in historical, cultural, and ecological contexts. This limitation underscores the urgent need for more inclusive, equitable, and context-sensitive approaches to climate action – ones that actively seek to dismantle epistemic hierarchies and valorise diverse ways of knowing.

However, we must also acknowledge that “although climate justice is by now a concept and term used and evoked in various settings around the globe, the dominant interpretations of its meaning-in-use have developed in the Western academy” (Wilkens & Datchoua-Tirvaudey, Reference Wilkens and Datchoua-Tirvaudey2022, p. 132). This implies that the task at hand is not limited to the decolonisation of climate narratives themselves but must also extend to the very academic spaces and epistemic frameworks from which such narratives are produced (refer to Figure 1, p. 20). If the concept of climate justice is to be meaningful and transformative, it cannot merely serve as a normative aspiration articulated from within “Eurocentric hegemony” (Sultana, Reference Sultana2022) or Global North epistemologies, for instance, by “decolonizing meanings of the climate crisis” as suggested by Datta et al., (Reference Datta, Chapola, Waucaush-Warn, Subroto and Hurlbert2024, p. 1).

In this context, achieving meaningful climate justice requires more than just the symbolic inclusion of diverse voices; it demands a fundamental restructuring of how knowledge about climate change is produced, disseminated, and legitimised. The prevailing narratives, which are rooted in Western epistemologies, fail to engage in narrative interaction with the knowledge systems of the Global South. Firstly, narratives from the Global South are insufficiently represented on the map I have developed to illustrate the diversity of climate narratives within academic literature. Secondly, these narratives are overshadowed by dominant climate narratives that exert greater control over climate narrative spaces. By excluding these perspectives, conventional climate narratives not only limit viable strategies but also perpetuate epistemic violence, thereby reinforcing the very inequalities that climate justice aims to dismantle.

Decolonising climate narratives – and, crucially, the academic spaces that generate them – is essential. This process requires recognising, for instance, the Inuit people of Eastern Baffin Island in the Arctic Ocean (Lejano et al., Reference Lejano, Tavares-Reager and Berkes2013), Māori indigenous perspectives (White et al., Reference White, Ardoin, Eames and Monroe2024), Pacific Islands climate vulnerabilities (Farbotko & Lazrus, Reference Farbotko and Lazrus2012), and climate shocks in Africa (Ayinde et al., Reference Ayinde, Oyedeji, Miranda, Olarewaju and Ayinde2024). Among others, these contributions help to integrate their practices into policy and governance frameworks and to question the normative assumptions embedded in Western-dominated climate discourse (Datta et al., Reference Datta, Chapola, Waucaush-Warn, Subroto and Hurlbert2024; Sultana, Reference Sultana2022; Wilkens & Datchoua-Tirvaudey, Reference Wilkens and Datchoua-Tirvaudey2022). In this context, narratives are not neutral; they influence what is seen as possible, legitimate, and actionable. Only by critically examining whose stories are told, how they are expressed, and who is empowered to narrate them can climate governance move towards a truly equitable, and sustainable future. By doing so, climate action can move beyond rhetorical commitment and towards transformative, equitable and context-sensitive solutions that genuinely reflect the interconnected realities of the global climate crisis.

In brief, the “missing” map of climate change narratives highlights three largely unresolved shortcomings. First, the idea is that each climate narrative has inherent limitations. They are shaped and constrained by their unique perspectives. What this means is that no single climate narrative can holistically and adequately deal with the vastly multifaceted challenges posed by climate change.

Second, climate narratives, although conditioned by their inherent limitations, are interrelated. New narratives may often emerge from earlier ones (see Figure 1, p. 20), creating a continuum that interconnects them across time. This dynamic aligns closely with the three dimensions of narrative analysis identified by Ntinda (Reference Ntinda and Liamputtong2019): temporality (which highlights the unfolding of narratives across time), sociability (which emphasises the relational aspect of narratives), and space (which draws attention to the geographic and contextual settings in which narratives are situated). Such an examination not only illuminates the dynamics of climate action or inaction but also enhances our understanding of the structures and conditions underpinning these responses, thereby reinforcing the significance of the third observation.

Third, the “missing map of climate narratives” provides clear evidence of the extent to which existing climate narratives built through the academic literature have insufficiently incorporated perspectives from territories and sociocultural contexts outside dominant Western frameworks. This absence has resulted in the marginalisation of voices and experiences from non-Western geographies. Addressing this challenge requires expanding the narrative scope to include plural epistemologies, cultural contexts, and lived experiences, thereby ensuring that climate narratives more accurately reflect the complexity of a world profoundly shaped by climate change. I state that the climate change narratives framed from the academic space reviewed in this manuscript undervalue, or more often ignore altogether, narratives that do not pertain to non-Western spaces. I suggest that the implementation of, for example, climate policies is hampered by the use of Western-made, Western-localised, and Western-owned narrative frameworks, particularly if the main umbrella narratives are “economistic techno-optimism, green capitalism, Green New Deal and degrowth,” identified as well by García-Olivares and López (2021). This exclusion undermines the ability of climate narratives to represent the uniqueness of the geographical conditions of the place, its cultural particularities, and socio-political conditions. I claim that climate narratives influence the range of possible responses to climate change, enabling or excluding certain guiding actions and determining the degree of influence and power that stakeholders, states, international organisations, and civil society, among others, may have in addressing the problem.

In this sense, the “missing map of climate narratives” provides a framework that can inform future studies and offer a valuable historical overview of the evolution of climate narratives within a particular time and context, i.e., within the Western historical context. Here, I encourage future research to explore further the field of climate narratives in Western and non-Western settings, which exhibit unique sociocultural, economic, and political characteristics that must influence the mapping of climate narratives in relation to climate justice, climate education, or decolonisation processes. In this matter, my study establishes a significant foundation for further exploration of climate narratives and invites ongoing discussion on the complexities of these issues.

Acknowledgements

I am sincerely grateful to the anonymous reviewers for their insightful comments and feedback, and to the Editorial Team of the Australian Journal of Environmental Education for their guidance on an earlier version of this article.

Financial support

This article is based on research originally funded by the Doctoral School Scholarship Program of the Open University of Catalonia.

Ethical standard

Nothing to note.

Author Biography