1. Introduction

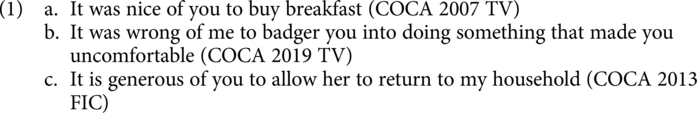

Understanding how grammatical form relates to meaning is central to linguistic theory, particularly in usage-based frameworks like Construction Grammar (CxG; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1995, Reference Goldberg2006). The syntactic patternFootnote 1 illustrated in (1), referred to in this study as the of-NP evaluation construction, exemplifies this complexity:

These sentences share a common structure, comprising the pronoun it in subject position, followed by copular be, an adjective, a prepositional phrase introduced by of containing a noun phrase (of + noun phrase) and an infinitival verb phrase. Each element in this syntactic pattern plays a specific grammatical role. In this construction, the subject it serves as a grammatical placeholder, allowing the construction to emphasize the evaluative adjective. The adjective (e.g., nice, wrong and generous) expresses an evaluative judgment, categorizing the agent in relation to the action described by the infinitival verb phrase (Quirk et al., Reference Quirk, Greenbaum, Leech and Svartvik1985; Stowell, Reference Stowell and Rothstein1991; Barker, Reference Barker2002; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2020). The of-noun phrase serves a dual role: It identifies the agent of the action denoted by the infinitival verb phrase while simultaneously marking this agent as the target of the evaluation expressed by the adjective. The infinitival verb phrase specifies the action that triggers the evaluation, grounding the entire construction in a particular context.

This syntactic pattern is not merely a collection of grammatical components but a unified construction that assigns a specific evaluative meaning to the agent, forming a distinct linguistic unit. This meaning emerges in ways not directly predictable from its individual components alone, making it an example of a construction whose specific syntactic pattern is considered a core part of constructions that possess inherent meaning. For instance, in (1a), nice describes you in light of the act of buying breakfast, highlighting the construction’s unique form-meaning pairing. This evaluative function, linking a personal attribute to an action via a specific syntactic configuration, is a key characteristic of this pattern. In this light, this study addresses the central question: What predictive signals does the of-NP evaluation construction leave in the processing stream, and how are these shaped by its construction-specific semantic constraints? The particular semantic role of the of-NP phrase, and the constraints on the types of adjectives that can felicitously occupy the adjective slot, suggests that the meaning of the whole construction is not entirely predictable from the sum of its parts in a purely compositional manner.

These observations raise questions about whether the ‘It + be + Adjective + of-NP + to-VP (verb phrase)’ pattern (termed of-NP evaluation construction) forms its own unique construction within the framework of CxG. What specific role does the of-noun phrase play in licensing the overall evaluative meaning of this construction? How do the adjective and noun slots in this construction interact with the overall constructional meaning and what constraints govern their usage? Can large language models (LLMs) capture the semantic compatibility required for this construction, and how might surprisal measures provide an empirical diagnostic for such compatibility?

To address these questions, this study adopts a CxG perspective, integrating both qualitative and quantitative methods. CxG views linguistic knowledge as a network of learned form-meaning pairings, where constructions range from morphemes to complex syntactic patterns (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1995, Reference Goldberg2006). Crucially, this framework rejects the strict separation between the lexicon and the syntactic component found in generative models, instead positing that grammatical rules themselves are stored constructions. This approach is particularly relevant to the present study because it allows us to treat the of-NP evaluation construction as a fully entrenched from–meaning pairing with its own semantic constraints. This perspective also aligns with the probabilistic learning mechanisms of LLMs, which encode linguistic knowledge as probabilistic associations across form and meaning, without compartmentalizing syntax and lexicon. By leveraging this parallel, the present study is positioned to test whether LLMs’ probabilistic expectations reflect the same semantic compatibility constraints observed in human language use.

A construction provides a template or slots, where lexical items fit into these slots. The meaning of these lexical items interacts with the meaning of the construction itself (called constructional meaning) to form the overall meaning of the sentence. For instance, the verb send can be used in a ditransitive construction (X sends Y Z) or a caused motion construction (X sends Z to Y). For a construction to function properly (in the process of semantic processing), the meaning of the lexical items that fill these slots must be compatible with the meaning of the construction, a principle known as semantic compatibility, one of the semantic constraints in CxG (Fillmore, Reference Fillmore1982, Reference Fillmore and Kay1999; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1995). This study proposes surprisal as a quantitative diagnostic of this principle, operationalizing semantic compatibility as the predictability of a slot filler given the constructional context. One of the goals of this study is to demonstrate that this semantic compatibility can be empirically supported through the surprisal analysis of LLMs, a quantitative analysis that uses prediction-based measures to assess the likelihood of particular lexical fillers in a given construction. Unlike frequency-based collostructional analysis, which captures static associations, surprisal analysis adds a dynamic, processing-oriented perspective, thereby enabling a more comprehensive account of construction–lexeme compatibility. Briefly, the LLM analysis allows us to predict which lexical items are permitted to be filled in these slots. By combining collostructional analysis and surprisal analysis, this study seeks to bridge distributional evidence and predictive processing evidence, providing converging support for the construction’s semantic constraints.

The ultimate goals of this study are twofold. First, it identifies the grammatical characteristics of this construction as a construction in CxG, including syntactic and semantic constraints, using collostructional analysis, a method developed by Stefanowitsch and Gries (Reference Stefanowitsch and Gries2003, Reference Stefanowitsch and Gries2005). Second, it explores the potential of LLMs for fine-grained linguistic analysis, asking whether these models can capture the semantic compatibility that underlies this construction.

To achieve this, the study follows four steps: (i) assembling a dataset of 934 naturally occurring sentences containing the of-NP evaluation construction from the COCA corpus; (ii) conducting collostructional analysis to determine the lexical items most strongly associated with the construction; (iii) performing surprisal analysis using GPT-2 to measure predictive processing difficulty for various slot fillers; and (iv) statistically evaluating the effects of three experimental manipulations – preposition alternation, NP agentivity and NP intentionality. This multi-method design allows for a systematic comparison between frequency-based association patterns and prediction-based processing measures.

Thus, the study not only tests the semantic compatibility principle rigorously but also shows how combining corpus-based and model-based analyses reveals deeper insights into constructional meaning and usage constraints.

2. Method

2.1. Data collection

The qualitative and quantitative analyses in this study primarily draw on examples from the Corpus of Contemporary American English (COCA)Footnote 2. The original dataset included 1,000 samples. After filtering out irrelevant examples – such as He should be ashamed of himself to be talking about it in that way or She’s much too frightened of him to do anything like that – the final sample size totaled 934 sentences. These exclusions were based on two main criteria: (i) structural deviation from the It + BE + ADJ + Of-NP + to-VP template and (ii) semantic mismatch with the evaluative function of the construction (e.g., idiomatic or metaphorical uses where the of-NP is not the agent of the infinitival clause). This refined dataset formed the empirical basis for all subsequent analyses, including (a) raw frequency counts, (b) collostructional analysis and (c) surprisal-based experiments.

2.2. Methodology adopted

One of the major goals of this study is to investigate whether the syntactic pattern of of-NP evaluation constitutes its own unique construction from the perspective of CxG. This pattern is expected to possess prototypical and constructional meanings that are not predictable from the meanings of its individual components. To explore these, the study adopts a multi-step corpus-based and model-based methodology.

First, a large set of naturally occurring instances of the It + BE + ADJ + of NP + to VP sequence is extracted from the COCA. The search is conducted using syntactic filters to ensure consistent structural patterns and to avoid noise from structurally ambiguous examples. Next, collostructional analysis (developed by Stefanowitsch & Gries, Reference Stefanowitsch and Gries2003, Reference Stefanowitsch and Gries2005) is applied to identify the strength of association between specific lexical items (e.g., adjectives and noun phrases) and the construction. Collostructional analysis was performed using standard tools in RFootnote 3. This quantifies how strongly adjectives and NPs are attracted to the construction, thus providing evidence for the construction’s conventionalized form–meaning pairing.

The second goal of this study is to assess the semantic compatibility of various lexical fillers that occupy key slots in the construction. A central assumption in CxG is that the lexical items filling constructional slots must conform to the principle of semantic compatibility (PSC) – that is, their meanings must align with the overall constructional meaning (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2006; Michaelis, Reference Michaelis, Boas and Sag2009).

To test this, the study employs surprisal analysis using LLMs, following recent methodologies in computational psycholinguistics (Futrell et al., Reference Futrell, Wilcox, Morita and Levy2020; Wilcox et al., Reference Wilcox, Qian, Futrell and Levy2022; Potts, Reference Potts2024). Surprisal values were computed using GPT-2 (Radford et al., Reference Radford, Wu, Child, Luan, Amodei and Sutskever2019), measuring the negative log-probability of target words given preceding context. Experimental sentences were constructed to reflect both prototypical and non-prototypical slot filters, allowing for a direct test of the semantic compatibility principle. By comparing the average surprisal scores across different NP types (e.g., pronouns, definite NPs and proper nouns), the study evaluates how expected or unexpected each filler is in the given constructional context. High surprisal values are interpreted as indicating lower compatibility with the construction, while lower surprisal values suggest semantic fit and conventionality. All surprisal values were statistically analyzed via analysis of variance (ANOVA) to test for significant differences between experimental conditions. Together, both methods clarify the construction’s structure and lexical constraints of the of-NP evaluation pattern.

3. English of-NP evaluation construction

Through the raw data and collostructional analyses, this study explores the syntactic and semantic characteristics of English of-NP evaluation construction. This section outlines the construction’s structural template, its grammatical roles and the semantic constraints that emerge from its usage patterns.

3.1. Syntactic form and grammatical roles of the construction

3.1.1. Syntactic template as a construction

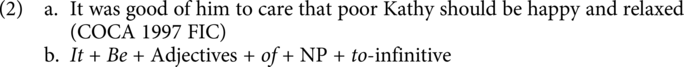

The structure in (2a) is schematically represented in traditional syntactic analyses in (2b). The pronoun it functions as a syntactic placeholder, followed by the copular be, an evaluative adjective and a prepositional phrase headed by of and followed by a noun phrase, which identifies the agent. The structure is completed by a to-infinitive verb phrase denoting the action being evaluated.

In (2a), the speaker is praising a man for his kindness or thoughtfulness because he cared about Kathy and wanted her to be happy and relaxed. Thus, this sentence can be paraphrased as ‘He was kind to concern about Kathy’s happiness and comfort’. From this interpretation, the of-NP segment functions as an evaluatee, even though the pronoun it occupies the subject position. The to-infinitival verb phrase expresses the action being evaluated.

The sentences in (3) illustrate the syntactic flexibility and structural constraints of the of-NP evaluation construction, providing evidence for identifying which elements function as fixed constituents and how they interact within the overall constructional template. Oshima (Reference Oshima2009) proposes the syntactic structure in (4a), advocating for an extraposition analysis in which to-infinitival verb phrase is treated as an extraposed subject. However, this structure cannot adequately account for the examples in (3a) and (3b), because in these cases, neither of NP nor Adj of NP syntactically combines with the infinitival clause as a single constituent.

Goldberg and Herbst (Reference Goldberg and Herbst2021) present a flat structural representation, as shown in (4b), which better captures certain surface features of the construction. Nonetheless, this structure still falls short in accounting for the examples in (3), because of NP to VP serves as a single constituent.

To address these issues, this study proposes an alternative structure, illustrated in (4c). This revised structure accommodates all examples in (3), though it remains theoretically unstable in some respects – particularly in how it treats the PP (prepositional phrase) and VP constituents. These constituents are better understood as adjuncts rather than arguments, since they are optional and provide elaborative evaluative information rather than fulfilling obligatory valence requirements of the adjective. For instance, adjectives such as kind or foolish may occur without these constituents (It was kind), indicating that the PP and VP function as modifiers that specify the scope or target of evaluation.

These limitations motivate a construction-based analysis in which the of-NP evaluation pattern is treated not merely as a surface arrangement but as a conventionalized form–meaning pairing. This perspective enables the integration of syntactic observations with semantic and pragmatic functions, aligning with the CxG framework adopted in this study.

Taken together, these observations suggest that traditional phrase structure representations – whether hierarchical or flat – are insufficient for capturing the syntactic and functional properties of the of-NP evaluation construction. This limitation motivates the analysis of the ‘It + BE + ADJ + of + NP + to VP’ sequence as a conventionalized form–meaning pairing – i.e., a fully established construction in the sense of CxG. Tree-based syntax overlooks the construction’s function. The inability of constituency trees to reflect the semantic integration of the of-NP and infinitival VP supports the treatment of this sequence as a construction in its own right. In this sense, the evaluative meaning is not derived from compositional semantics alone but arises from the pairing of this particular form with its conventionalized function.

3.1.2. Referential function of it

The of-NP evaluation construction in (1) includes the pronoun it in the subject position as a fixed element, as if it were a type of it-extraposition construction or an expletive construction (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson1970, Reference Wilkinson1976; Jackendoff, Reference Jackendoff1972; Oshima, Reference Oshima2009; Goldberg & Herbst, Reference Goldberg and Herbst2021). When we treat this pattern as the it-extraposition construction, the pronoun is not referential but merely fills the subject position to satisfy syntactic requirements.

However, unlike the canonical it-extraposition construction, this construction contains sentences like those in (5), where the pronoun it can be replaced by the pronouns that or this, even though it remains the most frequently used pronoun in this context. This substitution possibility is theoretically significant, as it implies that it cannot be unequivocally classified as nonreferential in this construction.

The two points weaken the claim that this construction is a type of it-extraposition. The first is that the pronoun it in this construction can alternate with demonstrative pronouns (this and that), which suggests it has referential potential rather than functioning purely as an expletive. Corpus evidence confirms that such alternations occur in the same structural environment and that this substitution is incompatible with a purely expletive reading. Demonstrative pronouns are inherently referential, pointing to specific discourse entities or situations. Their substitution for it suggests that it too has referential potential in this construction. Rather than merely filling a grammatical slot, it refers anaphorically or cataphorically to the propositional content of the infinitival verb phrase or the evaluative judgment expressed by the adjective phrase. This discourse-linking property becomes especially salient in interactional contexts, where that often refers to a previously mentioned action or claim, and this highlights a more immediate or contextually salient proposition.

Another point is that Wilkinson (Reference Wilkinson1976) suggests that the sentence in (6a) can be paraphrased as those in (6b)–(6d). This implies that the of-NP evaluation construction is difficult to treat as a type of it-extraposition construction. Specifically, the original form of the sentence in (6a) cannot be considered as *Of John to leave early was wise but may instead correspond to the sentences in (6b) or (6c). The sentence in (6d) would be one in which extraposition has been applied to the subject.

In this light, it in the of-NP evaluation construction is better analyzed as a referential pronoun, functioning to anchor an abstract proposition or event evaluation, rather than as an expletive devoid of semantic content. Accordingly, this study treats the of-NP evaluation construction as a distinct construction in its own right, rather than as a subtype of it-extraposition.

3.2. Grammatical functions and semantic constraints

3.2.1. Transitory and restrained evaluative adjectives

3.2.1.1. Raw frequency analysis

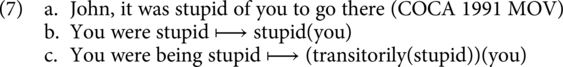

To understand the semantic behavior of adjectives in the of-NP evaluation construction, it is essential to identify the types of meanings they contribute. Prior descriptions indicate two core properties: evaluative force and transitoriness (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson1976; Oshima, Reference Oshima2009; Goldberg & Herbst, Reference Goldberg and Herbst2021). Oshima (Reference Oshima2009) analyzes the pattern as conveying an epistemic conditional, which naturally yields a transitory reading of the predicated quality rather than a stable trait. For example, the sentence in (7a) can be interpreted as ‘You went there, and given that you went there, you must have been being stupid.’ Thus, the adjective in this pattern expresses a transitory evaluation, as shown in (7c), rather than a stable property, as in (7b).

Adjectives in this construction are typically evaluative – they assess the agent in relation to the action denoted by the infinitival clause (Goldberg & Herbst, Reference Goldberg and Herbst2021). Even items like typical and characteristic, which carry weaker evaluative force, still pattern as stance-taking in many tokens, as illustrated in (8a-b); exceptions such as (8c) show non-agentive descriptions, and coordination with an overtly evaluative adjective (8d) strengthens an evaluative reading:

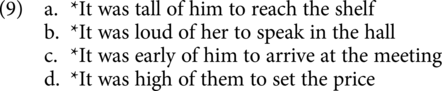

Furthermore, the adjectives in (9) – tall, loud, early and high – are not compatible with this construction. Their use results in ungrammatical or pragmatically infelicitous sentences, as they fail to convey an evaluative judgment of the referent introduced by the of-NP phrase. These adjectives typically describe physical or temporal properties of events or entities rather than attributing a judgmental stance toward the agent. As a result, they violate the construction’s evaluative requirement.

Corpus counts (see Supplementary Table 1 for the full list) show that nice, good and sweet account for nearly half of all tokens, suggesting a frequent use for socially positive, polite evaluation. However, raw frequency alone does not tell us whether such adjectives are construction-specifically associated. In Section 3.2.1.2., collostructional analysis refines this picture by highlighting moderately critical or socially restrained evaluatives (e.g., non-dickish, remiss, ungracious and presumptuous) as prototypical for the construction, thereby aligning the frequency patterns with a more precise statement of the construction’s evaluative profile. This distributional profile motivates our prediction that adjectives satisfying the evaluative requirement will be more predictable (lower surprisal) than adjectives that merely describe physical or temporal properties; Section 4.2 tests this prediction.

3.2.1.2. Collostructional analysis

In CxG, simple frequency analysis offers only a partial picture of how words function within a construction. While it reveals how often a word appears, it does not indicate whether the word is uniquely or strongly associated with that particular construction. High-frequency words may appear often simply because they are common across various contexts in the language. Collostructional analysis addresses this limitation by statistically measuring the degree to which a lexical item is strongly attracted to – or repelled from – the construction, relative to its overall frequency in the corpus. This method offers more reliable evidence for identifying construction-specific lexical patterns and allows for a more precise understanding of a construction’s conventionalized meaning.

To identify the degree of attraction between specific lexical items and the of-NP evaluation construction, this study employs collexeme analysis, a type of collostructional analysis. Collexeme analysis quantifies how strongly particular words are associated with a specific construction compared to what would be expected by chance, given their overall frequency in the corpus. This method is particularly effective in uncovering the lexical preferences that characterize a construction and in distinguishing the prototypical collexemes that contribute to its constructional meaning. Specifically, this approach enables the identification of prototypical lexical items and facilitates the interpretation of a construction’s conventionalized meaning. In this study, collexeme analysis is applied to the of-NP evaluation pattern, with a particular focus on the lexical items that fill the adjective and verb slots. The results offer empirical support for the construction’s semantic compatibility and help delineate its lexical constraints.

Supplementary Table 2 displays the distribution of adjectives ranked by collostruction strength in the of-NP evaluation construction. This table includes the top 30 adjectives, extracted from the results of the collostructional analysis.

The adjective with the strongest collostruction strength is non-dickish. The use of this adjective in of-NP evaluation construction highlights the construction’s prototypical meaning: The individual who is evaluated is perceived as not acting in a selfish or inconsiderate manner. Specifically, the adjective non-dickish can be regarded as a prototypical adjective within the category of socially considerate evaluation adjectives. These adjectives assess an individual’s behavior in terms of how well it aligns with socially acceptable, respectful or cooperative norms. Rather than expressing a strongly positive trait (e.g., generous and noble) or a strongly negative one (e.g., rude and cruel), non-dickish represents a moderately positive evaluation – one that highlights the absence of selfish, inconsiderate or disruptive behavior.

The next most strongly associated adjectives – ungracious, presumptuous and remiss – express more negatively biased evaluations, as shown in (10). Based on this distributional tendency, this study suggests that the of-NP evaluation construction frequently encodes negative or critical evaluations rather than explicitly positive ones. That is, this construction is more likely to serve as a conventionalized device for expressing criticism or negative evaluation in a mitigated and socially appropriate manner, rather than delivering overt praise, where frequent positive evaluatives reflect the construction’s polite usage. Adjectives such as non-dickish, remiss, obliging and politic do not trigger strong emotional reactions; instead, they convey restrained judgments or evaluations.

From the processing perspective, adjectives with high collostruction strength are expected to have lower surprisal values when predicted by a language model in this slot, since their usage is both conventionalized and semantically compatible. Section 4.2 tests this prediction by comparing surprisal distributions for high-strength versus low-strength collexemes.

3.2.2. Evaluative and agentive roles of of-NP

As mentioned in the previous sections, this construction includes a prepositional phrase consisting of a preposition of followed by a noun phrase, as illustrated in (11).

The of-NP segment functions as a fixed constituent within this construction and should be analyzed as a conventionalized phrasal unit governed by an agentivity constraint. Within this construction, the of-NP serves a dual function: It identifies the agent responsible for the action expressed by the infinitival verb and simultaneously denotes the individual who is evaluated as the adjective in relation to that action. For instance, in (12a), the of-NP clearly functions as the agent of the action, whereas (12b) is ungrammatical because the of-NP (the building) fails to meet the semantic requirement of agency, thereby violating the semantic compatibility in this construction.

The agentive interpretation of the of-NP is further supported by the possibility of transforming these sentences into structures where the agent occupies the subject position. In (13), the sentence with the of-NP in (13a) can be paraphrased into a construction with a canonical subject in (13b), confirming that the of-NP functions as the agent of the infinitival verb phrase.

Similarly, the examples in (14) reinforce this analysis. The of-NP in (14a) corresponds referentially with the subject in (14b), showing that it not only denotes the evaluator’s target but also the initiator of the action described by the infinitival verb phrase.

From the perspective of CxG, this agentivity constraint is integral to the form-meaning pairing: The syntactic configuration inherently presupposes an agent capable of intentional action, and the adjective evaluates that agent in light of the described event.

Because agentive NPs align with the construction’s semantic requirements, they are expected to yield lower surprisal values in predictive models. In contrast, non-agentive NPs (e.g., the building) violate the compatibility constraint and should produce higher surprisal, reflecting their reduced predictability in this slot. Section 4.3 tests this hypothesis through targeted manipulations of NP agentivity.

3.2.3. Infinitival verb phrase as the evaluated action

This study investigates the lexical items that occupy the infinitival verb slot of the construction. These verbs not only denote the actions attributed to the agent introduced by the of-NP phrase but also serve as a basis for evaluative judgments expressed by the adjective. The analysis aims to determine whether any conventionalized or construction-specific meanings emerge from the recurrent use of particular infinitival verbs.

First, Supplementary Table 3 exhibits the distribution of the lexical items found in the infinitival verb phrase slot in this construction. The raw frequency data indicate that the three verbs – come, say and join – collectively account for nearly 25% of all occurrences. However, no single verb appears to be uniquely prominent in this construction based solely on frequency.

Secondly, to further investigate whether there are any specific verbs that can determine the conventionalized meanings of this construction, this study additionally conducts the collostructional analysis (specifically collexeme analysis). Supplementary Table 4 displays the top 30 verbs most attracted to this construction, ranked by their collostruction strength.

The results demonstrate that two verbs – strong-arm and demo – are most strongly associated with the of-NP evaluation construction and best characterize its prototypical usage. This result allows us to distinguish the prototypical verbs that contribute to the constructional meaning.

First of all, the verb strong-arm implies force, threats or aggressive pressure to make someone do something and the verb demo involves making something explicitly visible, either to persuade or demand change. Thus, these two verbs entail actions involving explicit, forceful or demonstrative strategies to exert influence or control. Both verbs are agentive and action-oriented, aiming to alter the world or influence others whether by pressure (strong-arm) or by visibility (demo). They both go beyond passive communication and instead actively intervene in a situation to shape outcomes, either by pressure or by making something visible and clear.

Therefore, both verbs imply purposeful action intended to affect others directly. For instance, the sentence in (15a) expresses that the speaker is evaluating his own past behavior as unwise, precisely because they used coercion (i.e., strong-armed) to influence others.

In (15b), the verb demo carries the meaning of showing something publicly, possibly without proper caution. The adjective brash evaluates the agent’s (they) action as bold to the point of imprudence. Thus, the sentence evaluates the action of publicly demonstrating something on the road as potentially bold to the point of being reckless, thus expressing a mild criticism of the agent’s judgment in choosing to act that way. On the other hand, the sentence in (15c) conveys a positive evaluation of the addressee’s action of responding to an invitation. The adjective nice attributes social politeness to the agent (you) for fulfilling a basic but appreciated social obligation.

Thirdly, let us consider the semantic constraint imposed on the to-infinitival verb phrase. As mentioned in the preceding section, the noun phrase following the preposition of functions as the actor who performs the action expressed by the to-infinitival verb phrase. This actor role is typically realized by personal pronouns, which generally carry volitional intention. This necessarily implies that the to-infinitival verbs should express volitional actions and that these verbs are usually dynamic, though they may occasionally be stative, as shown in (16).

The verbs in (16a) and (16b) are dynamic verbs denoting intentional acts. By contrast, although the sentences in (16c) and (16d) are grammatical, the one in (16e) is ungrammatical, despite all involving stative verbs. This indicates that the verbs used in the of-NP evaluation construction must denote volition, whether they are dynamic or stative, which constitutes a clear semantic constraint of this construction. The sentences in (17) and (18) further support this observation.

In (17), the stative verb reside can carry either a volitional meaning, as in (17a), or a non-volitional meaning, as in (17b). However, only the volitional use is permitted in the of-NP evaluation construction, and using the non-volitional sense, as in (17c), results in an ungrammatical sentence. Similarly, the verb weigh can be used both as an intentional action, as in (18a), and as a purely stative property, as in (18b). However, only the intentional meaning fits into the construction, making (18c) ungrammatical.

Taken together, this study reveals that the infinitival verb phrases in the of-NP evaluation construction serve a dual function: It denotes the specific action attributed to the agent while simultaneously acting as the evaluative focus for the adjective. Although raw frequency data show no single verb as uniquely dominant, collostructional analysis identifies certain verbs – most notably strong-arm and demo – as strongly attracted to this construction, reflecting meanings tied to forceful or demonstrative actions intended to influence others. Furthermore, a semantic constraint emerges whereby only volitional readings of both dynamic and stative verbs are permissible in this construction, as the of-NP constituent inherently denotes an agent capable of intentional action. Instances where verbs lack volitional interpretation result in ungrammaticality, highlighting that the construction fundamentally encodes the evaluation of deliberate, agentive behavior. Thus, the lexical and semantic properties of the infinitival verb phrase are crucial in shaping the construction’s meaning and in distinguishing acceptable from unacceptable instances.

Processing prediction: In surprisal analysis, volitional verbs should have lower surprisal values when paired with agentive NPs in this construction, whereas non-volitional verbs are expected to produce higher surprisal due to their incompatibility with the construction’s meaning. Section 4.4 evaluates this prediction using controlled manipulations of verb volitionality. Thus, the lexical and semantic properties of the infinitival verb phrase are crucial in shaping the construction’s meaning, enforcing the evaluation of deliberate, agentive behavior and distinguishing acceptable from unacceptable instances.

3.2.4. Conventionalized and constructional meanings

The distributional data and collostructional analysis presented earlier suggest that the of-NP evaluation construction shows conventionalization in both form and meaning, which is also called a conventionalized form and meaning pairing, as summarized in (19).

First of all, adjectives such as non-dickish, ungracious and remiss are not only statistically associated with this pattern but also embody a specific evaluative stance that reflects a prototypical function of the construction. These adjectives tend to index moderated or socially negotiated judgments, rather than extreme praise or condemnation, reinforcing the idea that this construction serves to encode socially appropriate, restrained evaluation. In other words, this construction is typically used when the speaker wishes to convey a judgment in a restrained and socially appropriate manner. This ensures that the evaluation does not come across as impolite or overly confrontational.

Taken together, this study suggests that the constructional meaning of the of-NP evaluation construction lies in its function as a conventionalized strategy for expressing moderately negative or socially restrained evaluations of an agent’s coercive or persuasive intent. Speakers systematically employ this construction to encode moderately negative or socially restrained stances, rather than extreme emotional responses. The pattern’s grammatical form is closely associated with this evaluative function, reflecting a stable form–meaning pairing characteristic of constructions in CxG.

Prototypically, this construction is used to deliver indirect criticism or socially mediated moral judgment. Adjectives such as ungracious, remiss or even mildly humorous ones like non-dickish are most strongly associated in this slot, signaling that the speaker is evaluating the agent’s action without overt confrontation. This construction is especially useful in morally or socially sensitive situations, where direct blame or praise might be inappropriate. Instead, it allows for the articulation of minimal behavioral expectations or polite disapproval in a mitigated and socially acceptable way.

From a constructional perspective, the three slot constraints – evaluative, agentive and volitional – interact to form a coherent constructional compatibility profile. Fillers that satisfy all three constraints are semantically and pragmatically optimal for the construction, resulting in entrenched associations detectable in collostructional analysis.

Processing prediction: In surprisal terms, constraint-satisfying fillers (e.g., an evaluative adjective + agentive NP + volitional VP) should be more predictable and thus yield lower surprisal values, whereas constraint-violating fillers are less predictable and yield higher surprisal. This prediction directly links the construction’s conventionalized form–meaning pairing to models of prediction-based language processing.

4. Large language models

This study uses surprisal analysis with LLMs to clarify whether the semantic compatibility principle genuinely operates in language processing and to demonstrate the utility of LLMs for linguistic analysis. The following explains how LLM-based surprisal analysis supports the PSC. This principle, widely discussed in CxG (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1995, Reference Goldberg2006), posits that the meaning of a lexical item must be compatible with the meaning contributed by the construction it appears in. In other words, for a lexical item to appropriately occur in a construction, its inherent semantics must align with the construction’s conventionalized meaning. For instance, in the It is ADJ of-NP to-VP pattern from of-NP evaluation construction, the adjectives that appear (e.g., wise, considerate and foolish) typically express an evaluative judgment regarding the agent’s action. Adjectives that fail to semantically fit (e.g., tall and high) are strongly dispreferred or ungrammatical in this construction. This selectivity reflects semantic compatibility constraints, which LLM-based surprisal analysis can empirically evaluate.

LLM-based surprisal analysis offers a computational method for operationalizing and empirically testing PSC. Under PSC, a lexical item’s meaning must align with the constructional meaning it appears in (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg1995, Reference Goldberg2006). LLMs, which encode distributional semantic knowledge acquired from massive language exposure (Devlin et al., Reference Devlin, Chang, Lee and Toutanova2019; Mikolov et al., Reference Mikolov, Chen, Corrado and Dean2013), estimate the probability of a word given its context. If a word is semantically compatible with the constructional frame, it is assigned a higher probability and thus lower surprisal; conversely, semantically incompatible words receive lower probabilities and higher surprisal values (Piantadosi et al., Reference Piantadosi, Tily and Gibson2011; Wilcox et al., Reference Wilcox, Futrell, Qian, Ballesteros and Levy2020). This enables surprisal to serve as a probabilistic indicator of semantic compatibility, detecting graded differences rather than merely binary grammaticality. For instance, adjectives such as non-dickish or remiss may show moderately low surprisal, indicating strong compatibility, while less typical candidates exhibit intermediate surprisal levels. Let us consider the following examples in (20) within the of-NP evaluation construction.

LLM-based surprisal analysis yields higher surprisal values for tall because the model rarely or never encounters this adjective in evaluative contexts, reflecting its semantic incompatibility.

Therefore, surprisal serves as a probabilistic index of semantic compatibility, directly operationalizing the PSC by quantifying how expected a lexical item is within a construction. This provides empirical, corpus-driven evidence for one of the central theoretical assumptions in CxG, grounding abstract compatibility constraints in observable language data.

4.1. Models

This study used the GPT-2 language model (Radford et al., Reference Radford, Wu, Child, Luan, Amodei and Sutskever2019) for surprisal analysis. The model was accessed via the Hugging Face transformers library (Wolf et al., Reference Wolf, Debut, Sanh, Chaumond, Delangue, Moi and Rush2020) and executed within a Google Colab environment. Several factors motivated the selection of GPT-2 as the computational model for surprisal analysis. First, GPT-2 was chosen for surprisal analysis due to its autoregressive architecture, which predicts each word based on prior context and aligns directly with surprisal computation (Hale, Reference Hale2001; Levy, Reference Levy2008). Trained on WebText(~40GB), it captures extensive syntactic and semantic patterns relevant for CxG research (Radford et al., Reference Radford, Wu, Child, Luan, Amodei and Sutskever2019; Wilcox et al., Reference Wilcox, Futrell, Qian, Ballesteros and Levy2020). Unlike large models such as GPT-3 or GPT-4, GPT-2 publicly releases its weights and probability outputs, ensuring transparency and reproducibility essential for surprisal studies (Merkx & Frank, Reference Merkx and Frank2021). While smaller than newer models, GPT-2 balances linguistic sensitivity with computational efficiency, making it well-suited for this analysis.

Surprisal values for each token were extracted by computing the negative log-probability of the target word conditioned on its preceding tokens, following established procedures in surprisal-based language processing research (Hale, Reference Hale2001; Levy, Reference Levy2008). By leveraging GPT-2’s predictive distribution, word-level surprisal values were obtained as negative log-probabilities:

These surprisal values serve as a proxy for estimating the model’s expectation or processing difficulty for specific constructions.

4.2. Experimental test of the evaluative role of adjectives

The first experiment examines whether LLMs process adjectives in the of-NP evaluation construction as evaluative elements. In particular, this experiment aims to test whether LLMs are sensitive to the evaluative function that certain adjectives carry in the of-NP evaluation construction. Since the evaluative nature of adjectives constitutes a crucial semantic feature of this construction, surprisal values computed by LLMs provide insight into whether the models have internalized these functional properties.

4.2.1. DesignFootnote 4

To determine whether adjectives in this construction perform an evaluative function, this study first extracts all adjectives occurring immediately before a to-infinitival verb phrase. These adjectives are then classified into five semantic categories: evaluation, emotion, difficulty, obligation and perception. The evaluative category – kind, rude and generous – comprises adjectives that directly express judgment (e.g., It was rude of him to say that). The emotional category – including afraid, sorry, hesitant and proud – indicates the subject’s psychological or emotional state (e.g., Bob is afraid to fail). The difficulty (or tough) category – including hard, easy and ready – denotes the degree of difficulty or feasibility of the action (e.g., The book is hard to read). The obligation category – important, necessary and essential – conveys general statements of value, necessity or importance (e.g., It is important to be accurate). The perceptual category – including aware, conscious and mindful – reflects the agent’s state of awareness or cognition (e.g., He is mindful to do it properly).

By comparing surprisal values across these five categories, it is possible to identify which type of adjective the construction favors in performing its evaluative function. This experiment tests the hypothesis that evaluative adjectives yield significantly lower surprisal values in the of-NP evaluation construction than adjectives from the other four categories. Such a result would demonstrate the construction’s conventionalized evaluative function.

4.2.2. Results

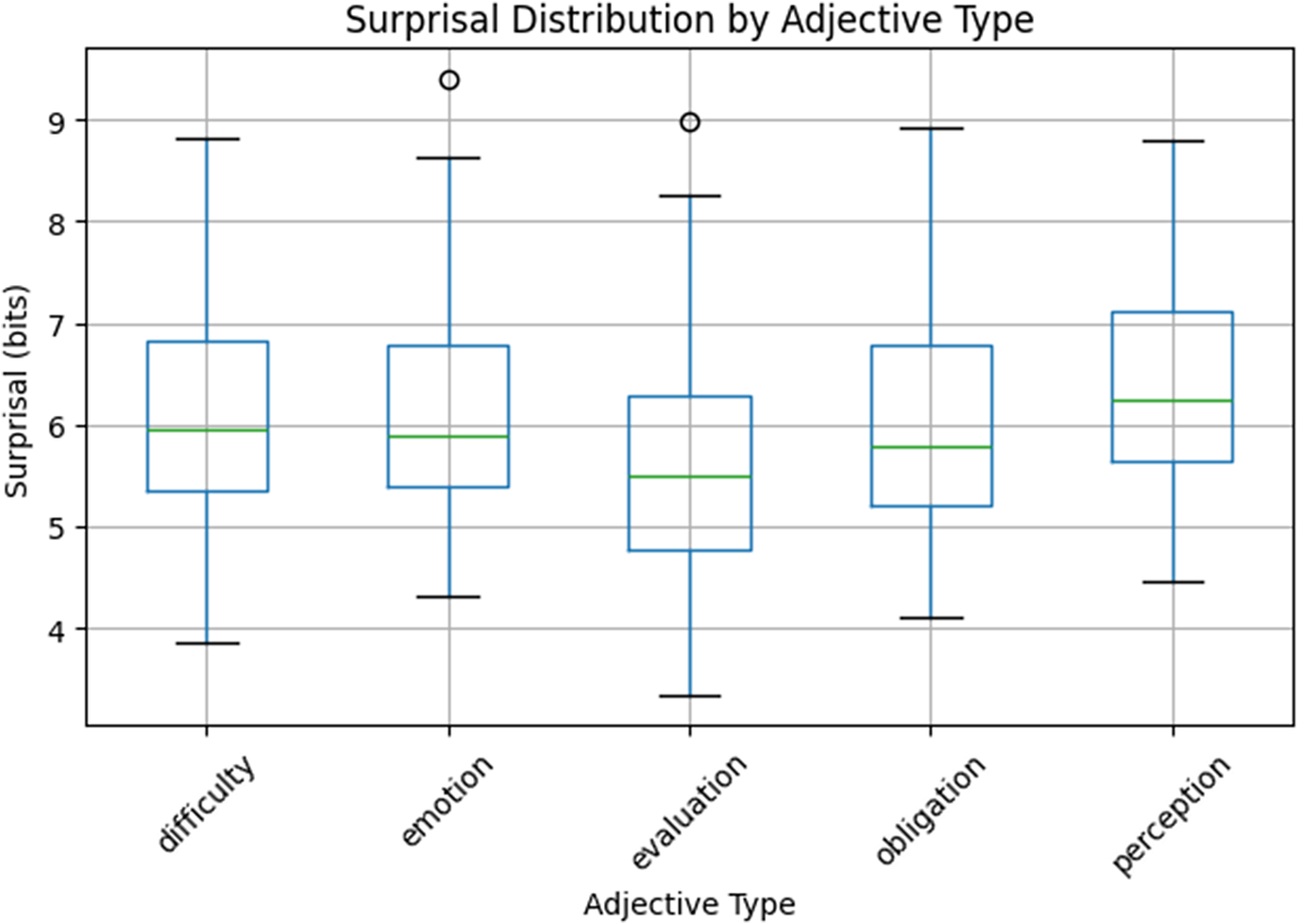

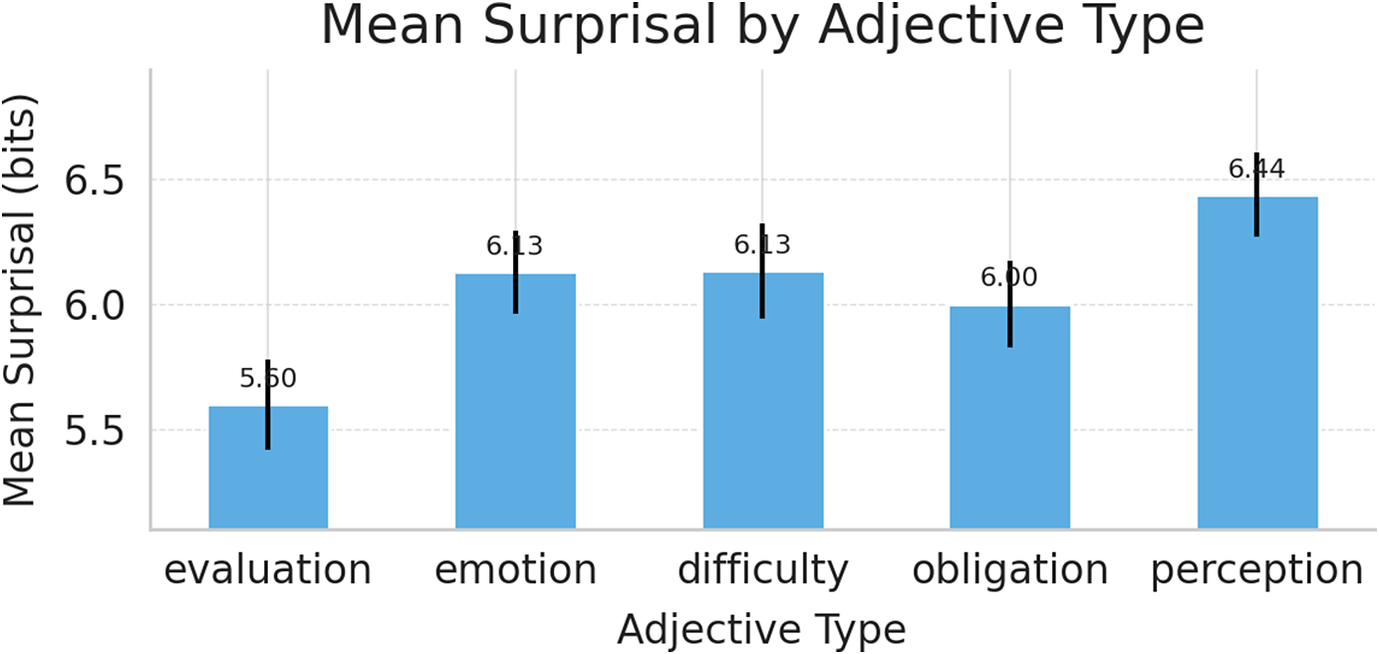

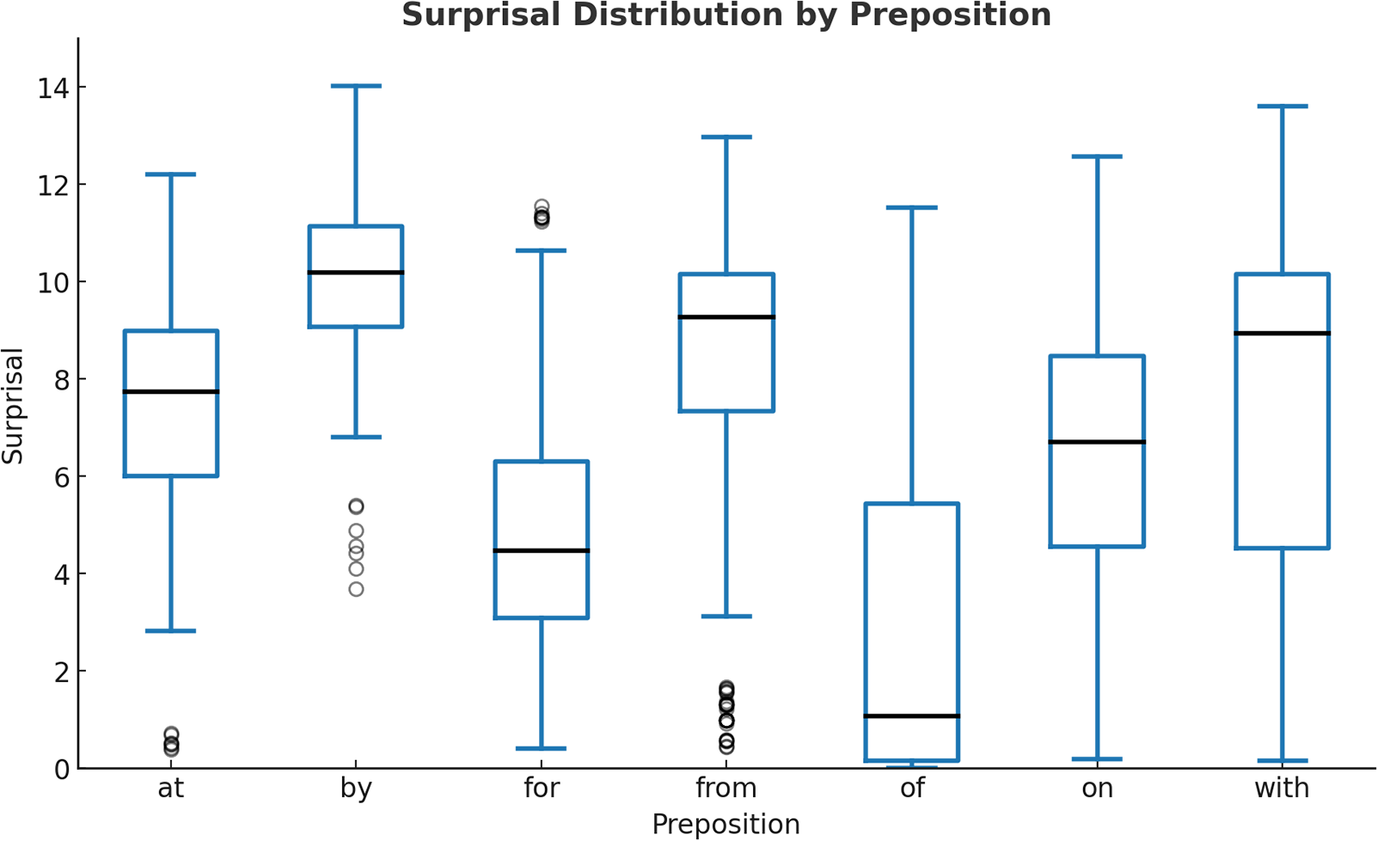

Figure 1 shows variation ranges and outliers among adjective types. Each box shows the surprisal distribution (median, interquartile and outliers). Figure 2 indicates the mean surprisal by adjective types.

Figure 1. Surprisal distribution by adjective type.

Figure 2. Mean surprisal by adjective type.

The result in Figure 1 demonstrates that the evaluative category has the lowest median surprisal and the narrowest interquartile range, indicating that GPT-2 most confidently predicts evaluative adjectives in of-NP evaluation construction. In contrast, perception adjectives exhibit the highest median and the widest spread, suggesting that they are the least expected. Emotion, difficulty and obligation types fall in between, with medians around 6 bits but somewhat broader variance than the evaluative group. In Figure 2, the mean surprisal for evaluative adjectives is substantially lower than for the other four categories, with perception adjectives showing the highest mean surprisal. This demonstrates that the of-NP evaluation construction strongly favors evaluative adjectives, yielding a lower processing cost (surprisal).

To examine whether surprisal values vary across semantic adjective types in this construction, a one-way ANOVA was conducted. Results showed a significant effect of adjective type, F(4, 694) = 11.42, p < .001. Descriptive statistics revealed that evaluation adjectives exhibited the lowest surprisal values (M = 5.60 and standard deviation [SD] = 1.09), while perception adjectives showed the highest surprisal (M = 6.44 and SD = 1.02). Post hoc Tukey’s honestly significant difference (HSD) tests indicated significant differences between evaluation and other types such as perception (p < .001), obligation (p = .014) and emotion (p = .0003). No significant differences emerged between difficulty and emotion types. These findings suggest that evaluative adjectives are more predictable and possibly more conventionalized in this construction than other semantic categories.

From a CxG perspective, these results imply that evaluative adjectives are semantically compatible with the of-NP construction and that LLMs have learned that adjectives in this construction directly express judgment. Specifically, these surprisal patterns mirror the conventionalized function of this construction as an evaluative strategy: When the model knows it is in this construction, it most confidently predicts adjectives that directly express judgment. Adjectives marking emotion, necessity, difficulty or awareness are less predictable, reflecting their lower conventional status in this construction.

4.3. Experimental test of prepositional alternation

4.3.1. Design

As noted in previous sections, the preposition of in the of-NP evaluation construction specifies a relationship of belonging or responsibility between the adjective evaluation and the agent following this preposition. To test whether of functions as an agentive marker, this study selected seven alternative prepositions – for, of, on, with, from, at and by – to replace of in the construction. Specifically, for introduces a beneficiary reading; on highlights a target; with implies accompaniment; from indicates source; at denotes a goal or target; and by explicitly marks the agent. Thus, this study hypothesizes that only of properly maintains the agentive relationship required for this construction, while substituting other prepositions would significantly distort its intended meaning. A dataset of 980 sample sentences was created, comprising 140 sentences for each preposition, by systematically replacing of with six alternatives. Word-level surprisal values were computed for each sentence using the GPT-2 language model.

4.3.2. Results

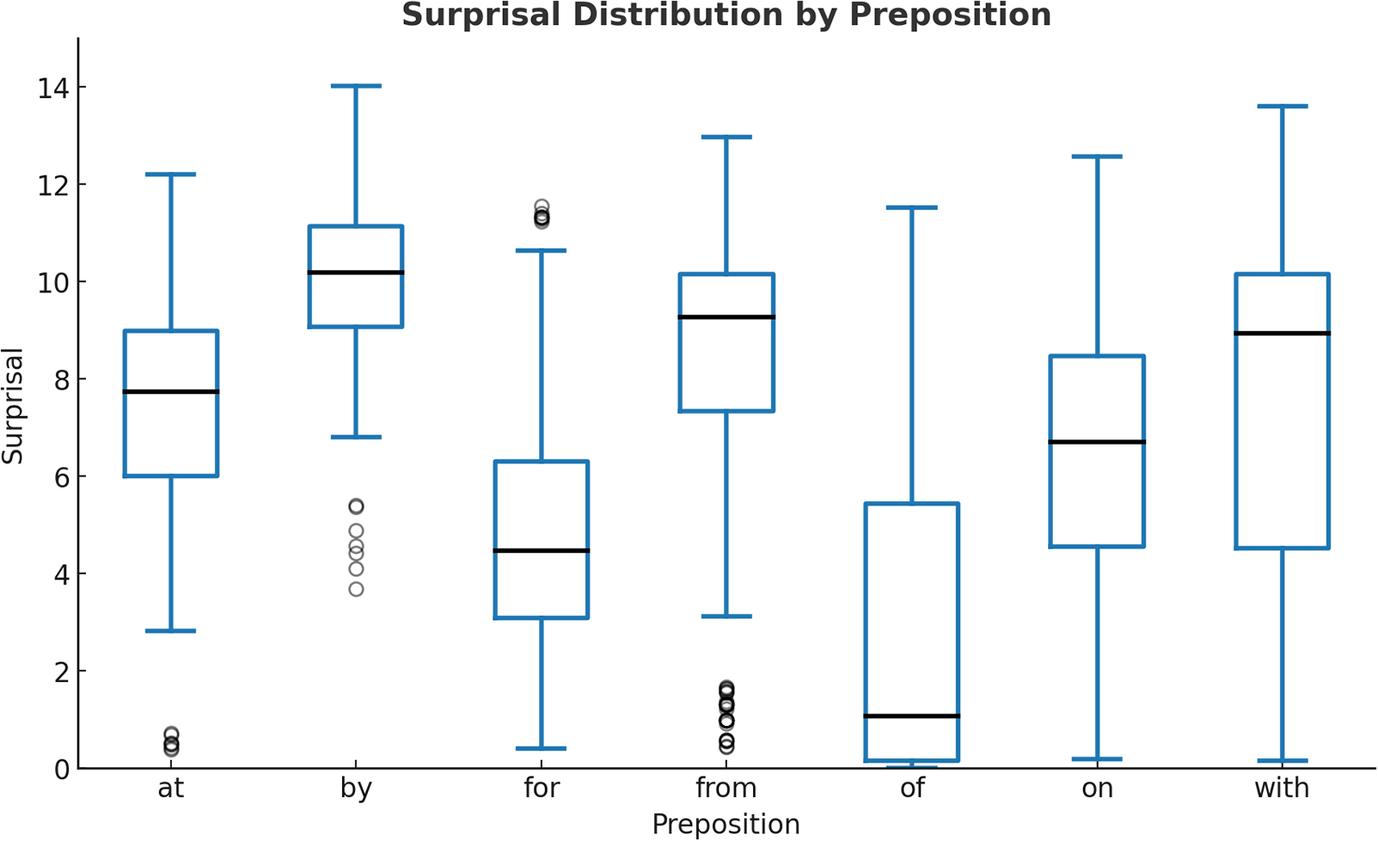

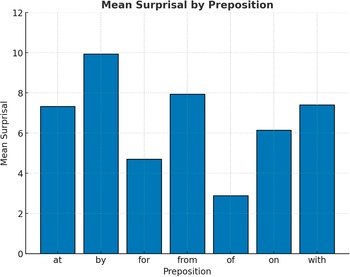

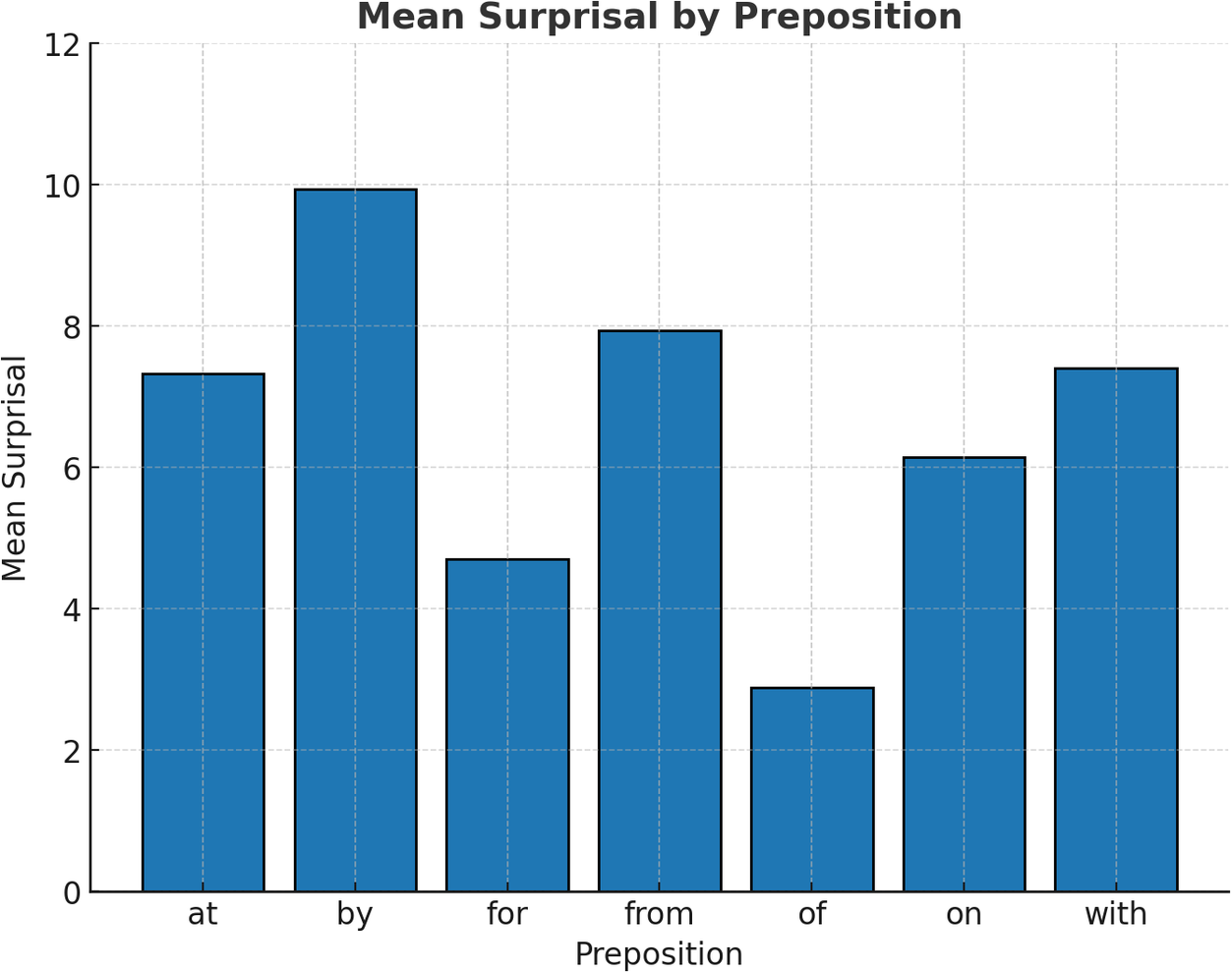

Figures 3 and 4 present the surprisal distributions across prepositions, showing variation ranges, outliers and mean values.

Figure 3. Surprisal distribution by preposition.

Figure 4. Mean surprisal by preposition.

These results provide empirical support for the constructional entrenchment of the of-NP evaluation construction. Among the seven prepositions, of consistently yields the lowest surprisal values, indicating that the language model expects this form as the agentive marker within the construction. This strongly implies that the preposition of is best compatible with this construction, thus following PSC.

In contrast, the six alternative prepositions yield higher surprisal values, reflecting varying degrees of semantic incongruity. Specifically, the preposition for shows slightly higher surprisal, suggesting partial compatibility due to its occasional use in introducing beneficiaries. Prepositions such as from, on and at show intermediate surprisal levels, while by and with triggered the highest surprisal scores, signaling severe constructional violations. By conflicts with the subtle agentive marking of of, introducing explicit agency typical of passive constructions, while with disrupts the argument structure by introducing a comitative reading incompatible with the evaluative function.

A one-way ANOVA was conducted to examine whether surprisal scores differed significantly across the seven prepositions tested in this construction. The analysis revealed a highly significant main effect of preposition on surprisal, F(6, 1401) = 126.41, p < .0001. The mean surprisal values varied substantially among prepositions, with of exhibiting the lowest mean surprisal (M = 2.88), reflecting its entrenched status as the conventional agentive marker in this construction. In contrast, alternative prepositions, including for (M = 4.71), on (M = 6.14), at (M = 7.33), with (M = 7.40), from (M = 7.93) and particularly by (M = 9.93), produced progressively higher surprisal scores, indicating increasing semantic incongruity and constructional violation. These results provide compelling computational evidence that the of-NP evaluation construction is not merely a syntactic sequence but a highly conventionalized form–meaning pairing, in which of plays a critical role in establishing an agentive relationship between the adjective’s evaluation and the NP referent. The statistically significant differences in surprisal across prepositions substantiate the hypothesis that substituting of disrupts the construction’s semantic compatibility, leading to elevated surprisal as the language model encounters unexpected or ill-formed structures.

Overall, these surprisal results confirm that of is semantically compatible as the agentive marker in this construction, while substitutions increase surprisal values, indicating the violation of semantic compatibility.

4.4. Experimental test of the of-NP slot

4.4.1. Design

As discussed in Section 3, the noun phrase following the preposition of serves dual functions: It is both the target of evaluation and the agent responsible for the action expressed by the to-infinitival verb phrase. To empirically validate this dual role, this study conducted a surprisal analysis using the GPT-2 language model, focusing on word-level surprisal values for the noun phrase immediately following the preposition of. A total of 560 test sentences were constructed, each conforming to the structure It + Be + ADJ + of-NP + to-VP, where the noun phrase slot was systematically varied across three semantic types: human, nonhuman animate and inanimate. For each category, prototypical noun phrases were selected (e.g., you, them, the teacher and the people for human; the dog and the animal for nonhuman animate; and the car and the idea for inanimate). This semantic classification enables an assessment of whether the noun phrases in the of-NP slot merely require agentive features or also involve volitional features.

A statistical comparison was planned to determine whether surprisal distributions differ significantly across noun phrase types. This would provide empirical evidence as to whether the construction more strongly favors human agents, as theoretically predicted by the construction’s evaluative and agentive constraints.

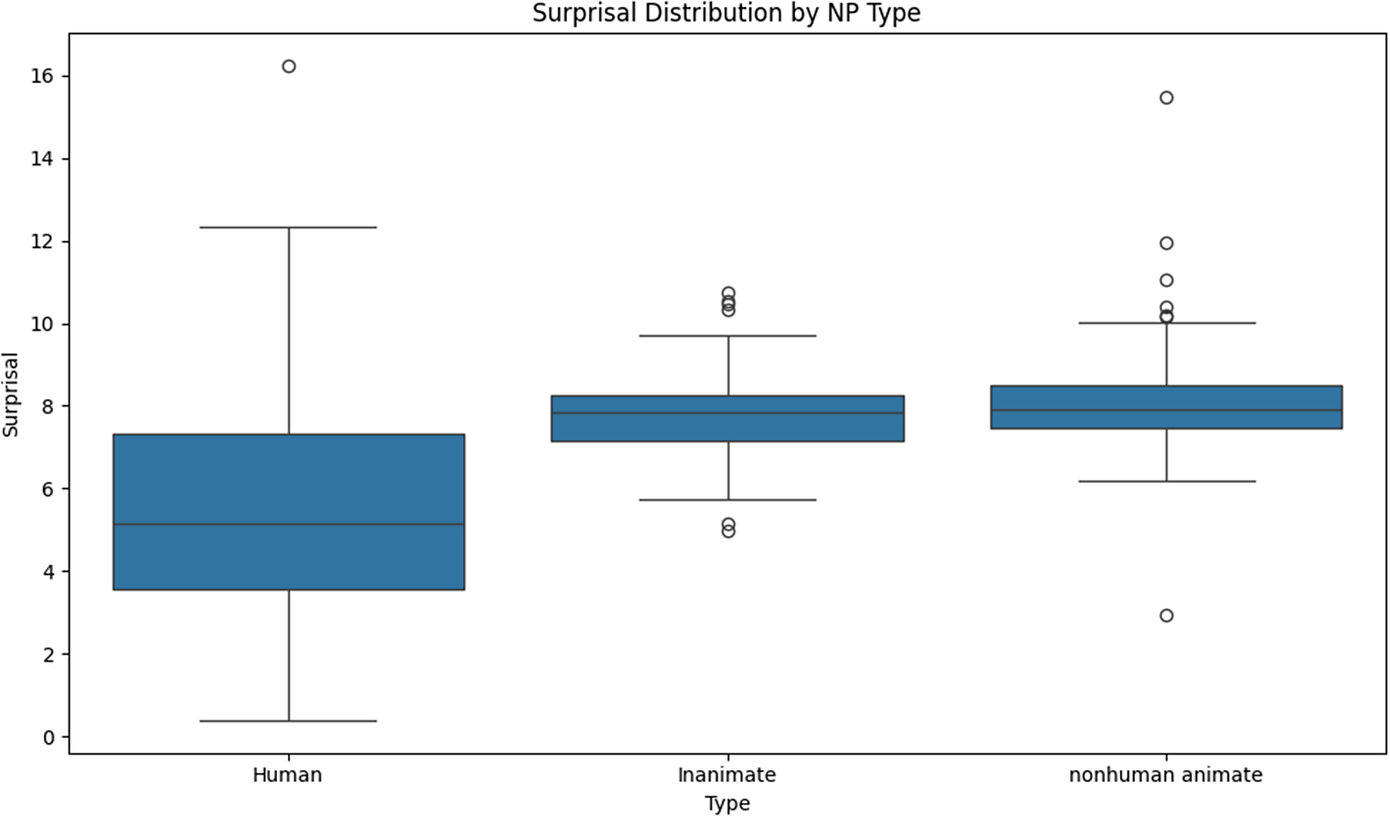

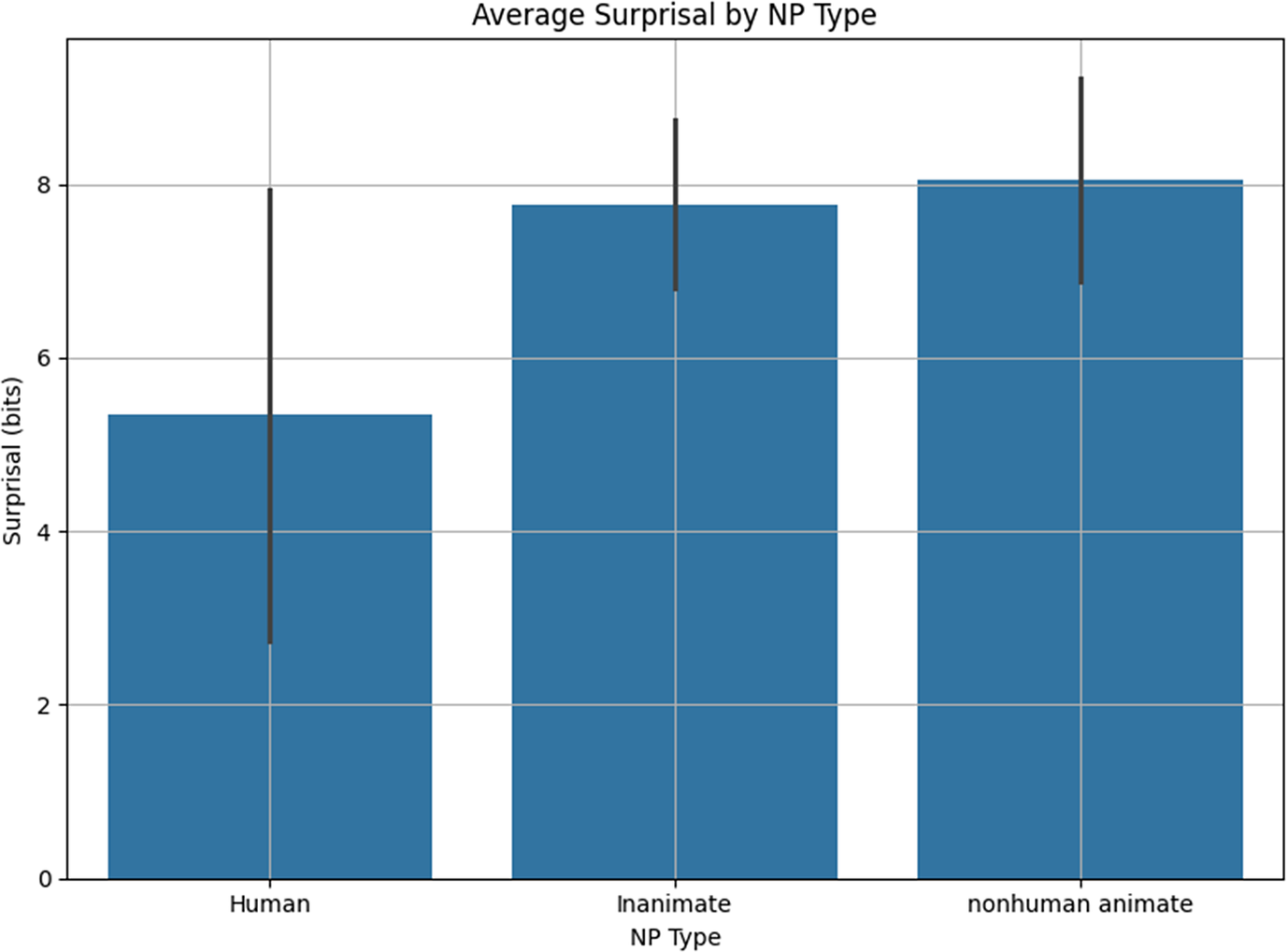

4.4.2. Results

Figure 5 displays the surprisal distribution by referent type, while Figure 6 presents mean surprisal values for each category. Human referents yield the lowest average surprisal (5.25 bits), followed by inanimate (7.77 bits), while nonhuman animate referents show the highest surprisal (8.05 bits). Human referents show the lowest and most variable surprisal. Nonhuman animate and inanimate referents yield higher median surprisal and narrower spread, indicating these categories are generally less predictable in this construction. This confirms that human noun phrases are the most expected, while nonhuman animate and inanimate noun phrases entail a higher processing cost.

Figure 5. Surprisal distribution by referent type.

Figure 6. Mean surprisal by referent type.

To investigate whether surprisal values differ across noun types in this construction, a one-way ANOVA was conducted. The analysis showed a significant effect of noun type on surprisal values, F(2, 554) = 116.34, p < .001. Descriptive statistics revealed that human nouns yielded the lowest surprisal values (M = 5.34 and SD = 2.60), whereas inanimate nouns (M = 7.77 and SD = 0.97) and nonhuman animate nouns (M = 8.05 and SD = 1.17) exhibited higher surprisal values. Post hoc Tukey’s HSD tests confirmed significant differences between human nouns and both inanimate and nonhuman animate nouns (both p < .001), while the difference between inanimate and nonhuman animate nouns was not significant (p = .48). These results suggest that noun animacy significantly influences the surprisal associated with the construction, with human nouns being more predictable than nonhuman entities.

These results indicate that the model finds human noun phrases to be the most predictable in this syntactic slot. In contrast, nonhuman animate and inanimate referents are less expected, with higher surprisal indicating lower compatibility. The greater variability in the human category indicates that some human noun phrases are highly expected (very low surprisal), while others are less so, possibly depending on lexical or contextual features. Nonhuman referents, on the other hand, are most uniformly treated as unexpected in this construction by the model.

In summary, these results demonstrate that human referents are more congruent with the of-NP evaluation construction, in terms of both mean surprisal and distribution. This supports the idea that this construction is conventionally used to evaluate human agents, aligning with social or moral expectations encoded in the adjectives. These results support the hypothesis that the of-NP slot is semantically constrained to agentive, volitional and typically human entities, making human referents more prototypical in this context.

4.5. Experimental test of the to-infinitival verb slot

4.5.1. Design

The verbs occupying the to-infinitival verb phrase slot serve as the semantic source of the action being evaluated. However, the semantic constraints governing verb selection in this slot are not immediately clear, particularly regarding which verb types are disallowed and why. A key to understanding these constraints lies in the semantic properties of the of-NP phrase, which typically encodes agentivity and volitionality. Based on this observation, this study classifies verbs into four types, according to their compatibility with agentive and volitional features: agentive dynamic verbs, volitional stative verbs, non-volitional dynamic verbs and non-volitional stative verbs. Agentive subjects generally co-occur with dynamic verbs, while stative verbs can appear in this construction only when they encode a sense of volition (e.g., It is courageous of you to be so honest). Agentive dynamic verbs involve intentional, goal-directed action. Volitional stative verbs reflect volitional states or attitudes. In contrast, non-volitional dynamic verbs describe events occurring without agency, while non-volitional stative verbs denote inherent states often lacking intentionality.

In contrast, non-volitional dynamic verbs and non-volitional stative verbs are expected to present a semantic mismatch with the of-NP evaluation construction. These verbs describe actions or states that occur without the subject’s intentional control or volition. Since the of-NP phrase presupposes an agentive participant, the inclusion of such non-volitional predicates (i.e., rain, manifest, sprawl, occur versus weigh, cost, suit, exhibit) undermines the evaluative function. In other words, it would be pragmatically incoherent to attribute praise or blame to an agent for an action or state over which they had no intentional control. For this reason, these verb types are typically dispreferred in the to-infinitival verb phrase slot.

4.5.2. Results

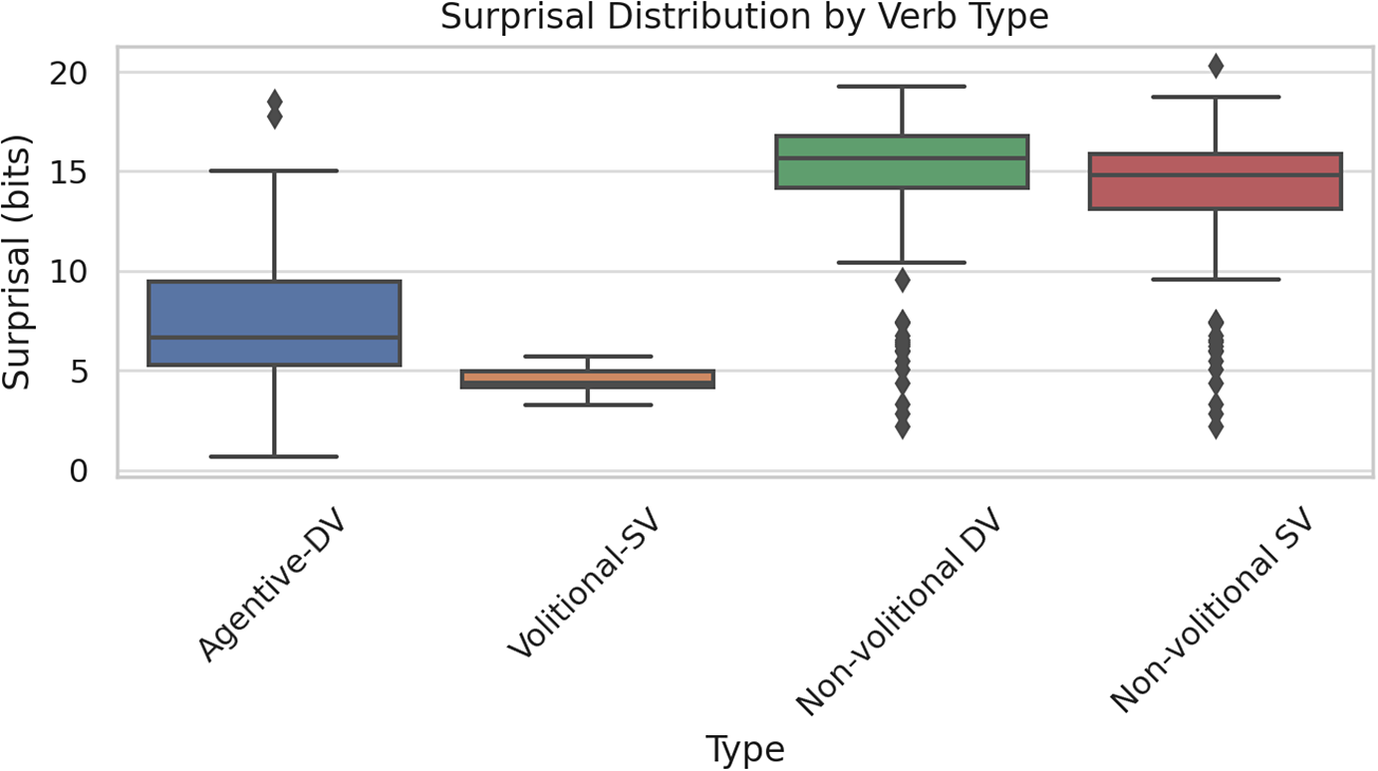

This study investigates how different verb types affect the surprisal values at the verb slot in this construction. By measuring word-level surprisal using LLMs, we attempt to identify the construction’s semantic constraints and its preference for particular verb classes, conforming to PSC.

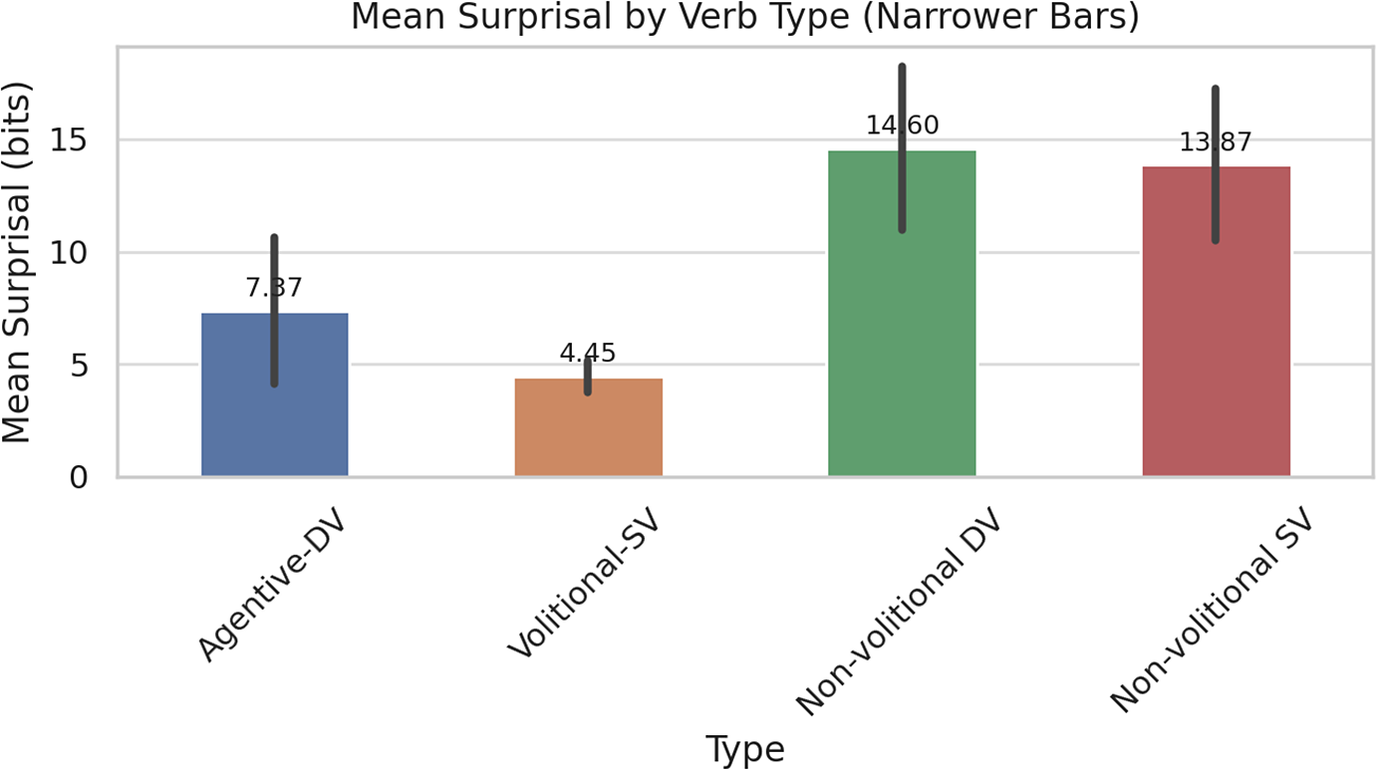

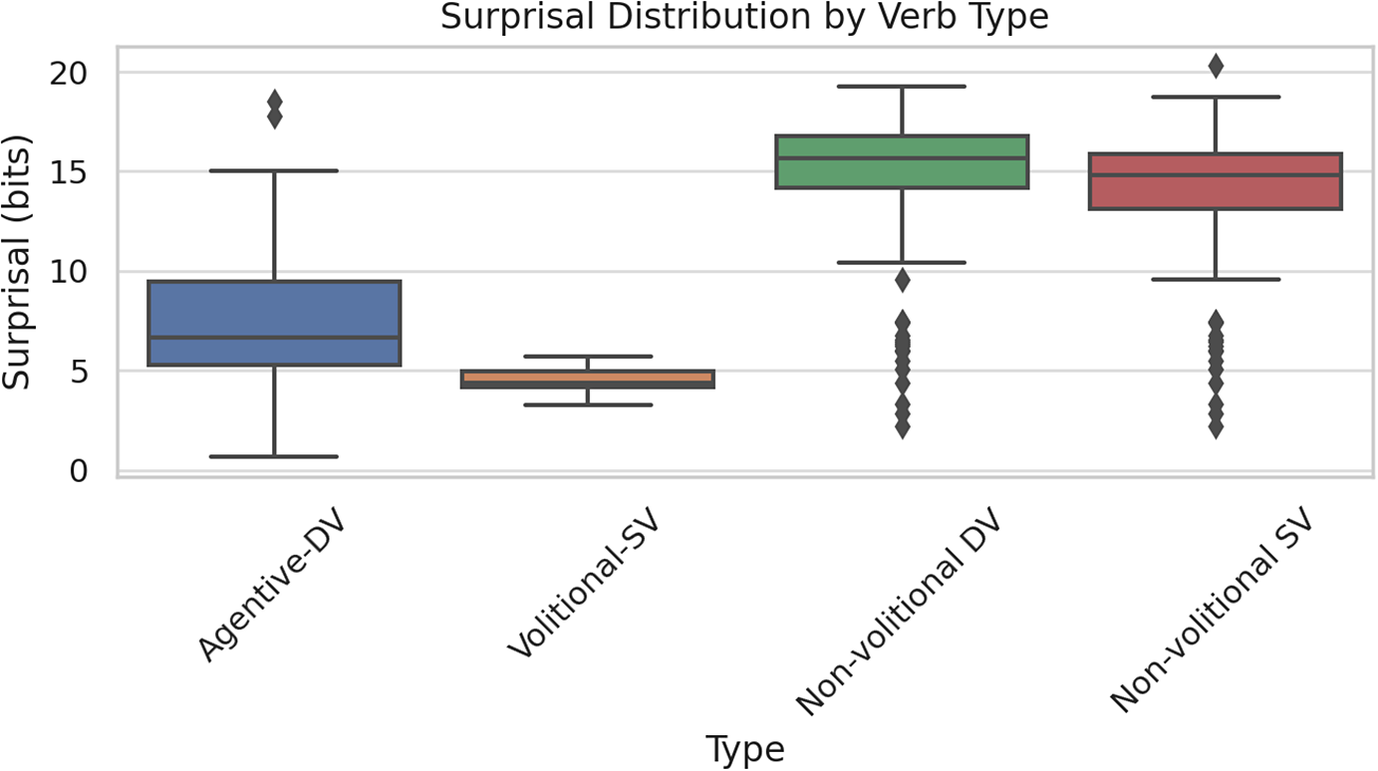

Figure 7 shows that the volitional stative verbs yield the lowest surprisal values and the agentive dynamic verbs also show relatively low surprisal compared to the non-volitional verbs. The difference in mean surprisal clearly reflects the construction’s bias toward volitional agency. The significantly higher surprisal of non-volitional verbs supports the claim that this construction is ill-suited for expressing evaluations of non-intentional states or events. Figure 8 indicates that the volitional stative verbs show the lowest surprisal values with tight distributions and the agentive dynamic verbs also show relatively low surprisal, with moderate variability. The non-volitional verbs show consistently high surprisal, with broader distributions and numerous outliers.

Figure 7. Mean surprisal by verb type.

Figure 8. Surprisal distribution by verb type.

To examine whether surprisal values differ across verb types in this construction, a one-way ANOVA was conducted. Results showed a significant effect of verb type, F(3, 416) = 136.32, p < .001. Descriptive analyses revealed that non-volitional dynamic verbs exhibited the highest surprisal values (M = 14.60 and SD = 3.64), followed by non-volitional stative verbs (M = 13.87 and SD = 3.37). In contrast, volitional stative verbs showed the lowest surprisal values (M = 4.45 and SD = 0.75). These findings suggest that surprisal values vary systematically across semantic verb types, potentially reflecting differences in predictability and cognitive processing demands associated with each verb class.

The LLM treats volitional and agentive verbs as more predictable and semantically compatible with this construction. In contrast, non-volitional verbs are perceived as less fitting, due to a mismatch with the construction’s inherent evaluative function, assuming an intentional agent. Therefore, this construction requires the to-infinitival verb phrase to be semantically compatible with volitional or agentive behavior, resisting verbs that describe involuntary or purely existential events, which violate its evaluative and semantic constraints. More specifically, the surprisal results provide evidence that this construction strongly favors verbs that denote volitional or agentive actions, aligning with its function as a linguistic strategy for social evaluation of intentional behavior. Non-volitional verbs produce higher surprisal because they undermine the construction’s functional coherence.

5. Constructional constraints and repelled items: a surprisal-based perspective on unusualness and unacceptability

5.1. Analytical method

Goldberg (Reference Goldberg2020) insightfully distinguishes between unusualness and unacceptability, emphasizing that not all departures from a constructional prototype are equally problematic. While unusual expressions may be infrequent or stylistically marked, they can still be acceptable if they conform to the construction’s core meaning and coverage. By contrast, unacceptability arises when an expression violates constructional licensing conditions or is blocked by a preempting construction. This view is central to the explain-me-this puzzle, where expressions such as The dinosaur swam his friends to the shore are judged creative yet grammatical, whereas She explained me the problem is rejected due to competition with the prepositional dative construction.

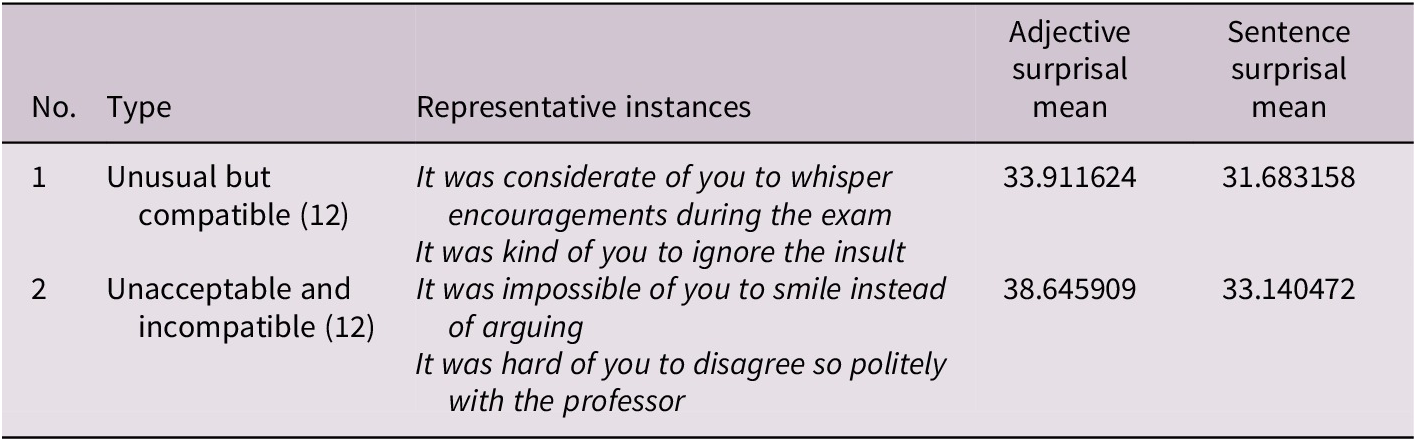

This section attempts to show that this theoretical distinction is examined through the English It-be-ADJ-of-NP-to-VP evaluation construction, using surprisal modeling as an empirical probe of constructional compatibility. The surprisal analysis was designed to examine how lexical and constructional cues interact in shaping acceptability.

(A) The adjective variation experiment manipulated semantic compatibility while keeping the of-you-to-VP frame constant (e.g., It was kind/difficult of you to help with the report).

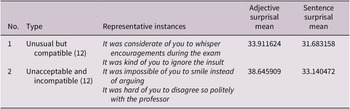

This analysis computed surprisal values at the adjective token and the entire sentence level using GPT-2. These measures operationalize three cognitive dimensions: semantic fit (compatibility), lexical rarity (coverage) and competition between near-synonymous constructions (preemption), as shown in Table 1.

Table 1. Mean surprisal by type a

a An independent-samples t-test indicated that adjectives classified as incompatible yielded significantly higher surprisal values (M = 38.65 and SD = 3.84) than compatible ones (M = 33.91 and SD = 3.27), t (22) = 2.74, p < .05, and Cohen’s d = 0.87. This confirms that surprisal values reflect semantic incompatibility rather than mere infrequency.

As summarized in Table 1, the surprisal distribution provides an empirical basis for distinguishing unusualness from unacceptability in constructional processing. Sentences containing repelled but semantically incompatible adjectives (e.g., It was impossible of you to smile instead of arguing) show higher surprisal at both the adjective and sentence levels, reflecting a clear mismatch between lexical semantics and the evaluative meaning of the It-be-ADJ-of-NP-to-VP construction. By contrast, repelled but semantically compatible items (e.g., It was kind of you to ignore the insult) exhibit moderately lower surprisal, suggesting that semantic fit can mitigate statistical rarity.

In Goldberg’s (Reference Goldberg2020) terms, these compatible–repelled items occupy the outer periphery of the construction’s coverage cloud: They are conceptually licensed but statistically underrepresented. Their relatively high surprisal indicates that the model perceives them as low-frequency but interpretable combinations, not as outright violations. At the same time, statistical preemption operates here: The more frequent use of for-you variants in overlapping evaluative contexts suppresses the productivity of of-you combinations, reinforcing their ‘repelled’ status within the grammar. Surprisal, in this sense, quantitatively traces the gradient competition between near-synonymous constructions, revealing the probabilistic asymmetry that Goldberg’s coverage–preemption model predicts.

Collectively, these results provide empirical support for the usage-based view of grammar, suggesting that constructional acceptability is not categorical but gradient – a phenomenon shaped jointly by distributional frequency and semantic fit. Surprisal thus emerges as a quantitative lens on constructional expectations, linking probabilistic learning with human judgments of acceptability.

6. General discussion

This study investigated the English of-NP evaluation construction through an integrated approach combining corpus analyses and LLM-based surprisal measures. The findings confirm that this construction functions as a conventionalized form–meaning pairing in CxG (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2006, Reference Goldberg2020), serving as a linguistic strategy for socially mediated evaluation. Surprisal analyses further demonstrate systematic semantic constraints on adjectives, noun phrases and infinitival verbs, with strong alignment between human linguistic intuitions and computational modeling (Futrell et al., Reference Futrell, Wilcox, Morita and Levy2020; Wilcox et al., Reference Wilcox, Futrell, Qian, Ballesteros and Levy2020). These results offer significant theoretical implications for CxG and the application of computational methods in linguistic research.

6.1. Integration of corpus-based and LLM-based findings

The study demonstrates how corpus-based analyses and LLM-based surprisal analyses complement each other in elucidating the of-NP evaluation construction. Corpus data revealed lexical preferences linked to evaluative functions, while surprisal analyses confirmed that these preferences reflect entrenched semantic constraints rather than arbitrary patterns (Futrell et al., Reference Futrell, Wilcox, Morita and Levy2020; Wilcox et al., Reference Wilcox, Futrell, Qian, Ballesteros and Levy2020). This integration provides a robust basis for understanding how constructions operate as conventionalized form-meaning pairings (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2020).

6.2. Implications for Construction Grammar

These findings have significant implications for CxG. Traditional syntactic analyses, such as extraposition accounts (Wilkinson, Reference Wilkinson1976; Oshima, Reference Oshima2009), prove insufficient to explain the unique combination of syntactic and semantic features in the of-NP evaluation construction. The evidence supports treating this construction as an independent form–meaning pairing, consistent with the CxG view that linguistic knowledge consists of stored constructions (Croft, Reference Croft2001; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2006). The prominent role of certain adjectives and verbs suggests that constructional meaning arises not only from grammatical structures but also from specific lexical associations (Stefanowitsch & Gries, Reference Stefanowitsch and Gries2003, Reference Stefanowitsch and Gries2005). Moreover, the capacity for referential pronouns such as this or that to replace it underscores how discourse context dynamically shapes constructional meaning (Jackendoff, Reference Jackendoff1972; Goldberg & Herbst Reference Goldberg and Herbst2021). Overall, the study illustrates how the of-NP evaluation construction exemplifies the type of conventionalized, usage-based pattern central to CxG.

The construction examined here corresponds to what Goldberg and Herbst (Reference Goldberg and Herbst2021) termed the nice-of-you construction. While their research documented the construction’s semantic profile and collocational tendencies, the present study extends this inquiry by revealing – through surprisal- and collostruction-based evidence – that constructional meaning emerges as a gradient expectation pattern in LLMs. This result substantiates a central CxG assumption: that linguistic knowledge is probabilistic and usage-sensitive, grounded in the speaker’s and hearer’s expectations shaped by experience.

6.3. Constructional meaning and multidimensional evaluation

A central finding concerns the semantic constraints inherent to the of-NP evaluation construction. Evaluative adjectives are strongly favored, while purely descriptive adjectives such as tall or loud are excluded due to semantic incompatibility. Human noun phrases yield the lowest surprisal values, reflecting referents show higher surprisal. Likewise, verbs in the infinitival verb phrase must denote volitional actions; non-volitional verbs are largely inadmissible unless interpretable as intentional. These semantic constraints highlight that the construction’s primary function is not merely syntactic but deeply tied to its role as a device for socially mediated evaluation, allowing speakers to express judgments about intentional human actions in a polite or mitigated manner.

While the preceding analyses have identified the evaluative, agentive and volitional constraints of the of-NP evaluation construction, a fuller theoretical account requires clarifying how these constraints map onto the broader semantics–pragmatics interface and recent multidimensional approaches to constructional meaning.

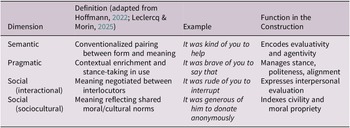

From a semantics–pragmatics perspective, the present study adopts the conventionality-based distinction (Leclercq, Reference Leclercq2020), according to which semantic meaning refers to conventionalized pairings between form and interpretation, whereas pragmatic meaning arises from contextually inferred or interactionally negotiated uses of those pairings. In this sense, the evaluative meaning of the It is ADJ of NP to VP construction is partly semantic, as in (17a), where It was kind of you to help her expresses a conventionalized association between kind and prosocial agency. Yet it is also pragmatic, as in (17b), where It was brave of you to say that conveys not just evaluation but also a stance toward social risk and politeness management. This dual status supports the idea that constructional meaning arises from the interface between semantic conventions and pragmatic inference (Boas et al., Reference Boas, Ziem and Allen2024; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2019).

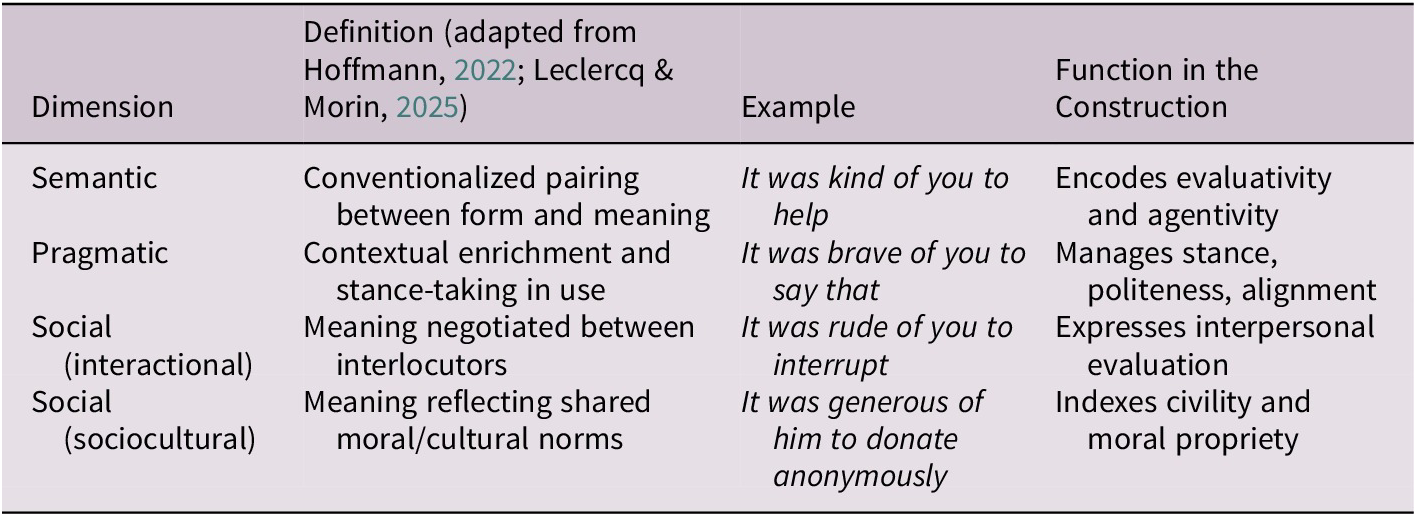

Recent multidimensional models of constructional meaning (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2022; Leclercq & Morin, Reference Leclercq and Morin2025) further expand this interface by distinguishing semantic, pragmatic and social dimensions, the last of which can be subdivided into interactional and sociocultural layers. Viewed through this lens, the of-NP construction primarily encodes social meaning. It functions as an interactional resource for affiliative stance-taking – e.g., It was rude of you to interrupt – and simultaneously as a sociocultural signal indexing civility or moral judgment – e.g., It was generous of him to donate anonymously. Such uses demonstrate that evaluation in this construction is not truth-conditional but socially mediated, reflecting relational norms between speaker and addressee, as shown in Table 2 (Morin et al., Reference Morin, Leclercq and Tellier2024; Ungerer & Hartmann, Reference Ungerer and Hartmann2023).

Table 2. Dimensions of constructional meaning in the of-NP evaluation construction

The surprisal patterns observed in Section 4 provide empirical support for this multidimensional interpretation. Adjectives that are semantically compatible with the constructional meaning (kind, rude and generous) yielded low surprisal values, reflecting strong conventional associations at the semantic level. In contrast, adjectives that violate evaluative or social compatibility (tall, heavy and cold) showed sharp surprisal increases at subsequent constructional anchors (of and to), suggesting that the model detects misalignment not merely at a truth-conditional level but at the level of socially mediated expectation. This indicates that surprisal can serve as a quantitative index of constructional meaning, bridging semantic regularity with pragmatic and social inference.

Integrating these perspectives refines the account of constructional meaning advanced here. The of-NP evaluation construction exemplifies a multidimensional form–meaning pairing in which (i) semantic constraints enforce evaluativity, agentivity and volitionality; (ii) pragmatic functions manage stance and politeness; and (iii) social functions encode culturally shared norms of moral and affiliative behavior.

This multidimensional view situates the present analysis within current debates on how constructions encode meaning across interconnected representational layers (Hoffmann, Reference Hoffmann2022; Leclercq & Morin, Reference Leclercq and Morin2025), thereby strengthening the theoretical contribution of this study to CxG’s ongoing ‘social turn’.

6.4. Large Language models as tools for constructional analysis

This study also underscores the methodological contributions of LLMs to linguistic analysis. The surprisal analyses conducted here demonstrate that LLMs can capture subtle semantic constraints associated with specific constructions, providing quantitative evidence that aligns closely with human linguistic intuitions (Futrell et al., Reference Futrell, Wilcox, Morita and Levy2020; Wilcox et al., Reference Wilcox, Futrell, Qian, Ballesteros and Levy2020). In particular, the lower surprisal values for evaluative adjectives and human referents, and the higher surprisal values for semantically incompatible elements, suggest that LLMs have internalized not only syntactic patterns but also construction-specific meaning associations. However, while LLMs offer powerful tools for exploring linguistic phenomena, certain limitations remain. These include difficulties in handling discourse-level context and challenges in predicting rare or novel lexical combinations. Nonetheless, the results highlight the potential of LLM-based surprisal analysis as a promising method for future studies in computational CxG and suggest that further developments in LLM architectures could enhance their ability to model linguistic constructions with even greater precision.

6.5. Limitations and future directions

Despite its contributions, this study has several limitations that suggest directions for future research. First, the current analysis relies on the COCA corpus, which may introduce genre bias. Expanding the dataset to include more conversational and cross-register corpora such as Global Web-Based English Corpus (GloWbE) or British National Corpus (BNC) would help enhance the generalizability of the findings. In addition, although the of-NP evaluation construction is assumed to be relatively productive, only about 1,000 tokens were retrieved from COCA. While this dataset was sufficient for the purposes of statistical analysis, a larger and more diverse corpus would enable a finer-grained examination of constructional variation. Second, LLMs still face challenges in modeling broader discourse context, which is crucial for capturing how evaluative meaning interacts with pragmatic and social factors (Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2020; Michaelis, Reference Michaelis, Boas and Sag2009). Addressing this limitation would require models that incorporate discourse-level information or multimodal input reflecting actual communicative contexts. Finally, cross-linguistic extensions of this research would be valuable. Investigating whether comparable evaluative constructions exist in other languages could reveal both universal tendencies and language-specific realizations (Croft, Reference Croft2001; Goldberg, Reference Goldberg2006). Future studies might also test whether the of-NP evaluation construction consists of distinct sub-constructions characterized by particular adjective–verb pairings, thereby refining our understanding of its internal structure and semantic diversity.

7. Conclusion

This study has examined the of-NP evaluation construction (e.g., It’s really nice of you to help me plan this wedding) with two main goals: first, to provide a detailed construction-based analysis of its syntactic and semantic properties from the perspective of CxG; and second, to demonstrate the potential of LLMs as tools for fine-grained linguistic analysis, confirming the construction’s unique status as a conventionalized form-meaning pairing.

Integrating corpus-based analysis with LLM-based surprisal analysis, this study reveals that the of-NP evaluation construction functions as a conventionalized linguistic strategy for socially mediated evaluation, rather than as a purely syntactic pattern. Corpus findings show that evaluative adjectives and certain infinitival verbs are strongly associated with this construction, reflecting specific lexical and semantic constraints. Collostructional analysis has clarified how adjectives like non-dickish and verbs like strong-arm contribute to the construction’s evaluative nuance and social functions.

LLM-based surprisal analyses further corroborate these patterns, demonstrating that language models internalize conventionalized semantic compatibility and provide quantitative evidence supporting theoretical assumptions in CxG. Notably, surprisal measures differentiate between adjectives, prepositions and verb types in ways that mirror human linguistic intuitions.

Overall, the findings underscore how constructional meaning is intimately linked to semantic constraints, particularly the preference for evaluative adjectives, human agentive NPs and volitional verbs. This study offers one of the first validations that LLMs can reflect such constraints, suggesting promising avenues for computational approaches to CxG and for exploring how models encode form–meaning pairings and lexical restrictions. Future research could extend this work to conversational data or examine cross-linguistic parallels, further refining our understanding of evaluative constructions in human language.

The study thereby contributes to multidimensional approaches to constructional meaning by empirically demonstrating that social evaluation constitutes an inherent layer of constructional semantics, bridging conventional meaning, pragmatic inference and sociocultural alignment.

Supplementary material

The supplementary material for this article can be found at http://doi.org/10.1017/langcog.2025.10045.

Data availability statement

Due to copyright restrictions, raw corpus data from COCA cannot be shared publicly. However, all derived datasets (including annotated examples, surprisal outputs and statistical results), as well as the complete Python scripts used for surprisal computation and statistical analysis, are publicly available at Zenodo (DOI: http://doi.org/10.5281/zenodo.17504372).

Acknowledgements

I would like to express my sincere gratitude to the anonymous reviewers of Language and Cognition for their insightful and constructive comments. Their valuable suggestions have significantly deepened the theoretical perspective and improved the clarity of this paper.

Author contribution

The author solely conducted the research, analysis and writing of the manuscript.

Funding statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests

The author declare none.