I. Introduction

In markets with asymmetric information, individuals rely on observable signals to infer quality (Akerlof, Reference Akerlof1970; Spence, Reference Spence1973). In wine, product attributes such as price, country of origin, collective regional reputation, and critic scores shape perceived quality and, in turn, choice; particularly when direct product experience is limited (Kaimann et al., Reference Kaimann, Bru and Frick2023; Menival and Charters, Reference Menival and Charters2014; Schamel, Reference Schamel2009; Schnabel and Storchmann, Reference Schnabel and Storchmann2010; Veale and Quester, Reference Veale and Quester2008). Beyond quality inferences, product attributes also function as vehicles for identity signaling: individuals use product choices to communicate who they are (Gal, Reference Gal2015). For instance, Sexton and Sexton (Reference Sexton and Sexton2014) find that some consumers pay a premium for the distinctively designed Toyota Prius to signal their commitment to the environment rather than to obtain superior product quality.

Wine is culturally loaded and often consumed in public settings, making it a natural means of signaling identity. Popular culture illustrates this potential: the movie Sideways portrays Merlot, and, implicitly, its drinkers, as ordinary, while Pinot Noir is presented as sophisticated (Payne, Reference Payne2004). Following the movie's release, demand shifted from Merlot towards Pinot Noir (Consoli et al., Reference Consoli, Fraysse, Slipchenko, Wang, Amirebrahimi, Qin, Yazma and Lybbert2022; Cuellar et al., Reference Cuellar, Karnowsky and Acosta2009), consistent with identity-signaling motives.

Building on identity economics, which maintains that individuals’ utility depends in part on acting in line with the norms of a salient identity (Akerlof and Kranton, Reference Akerlof and Kranton2000), and evidence that private and professional selves prioritize different values (LeBoeuf et al., Reference LeBoeuf, Shafir and Bayuk2010), we examine whether wine choices may signal value priorities. In professional settings, we anticipate conformity- or status-oriented signaling aligned with a professional identity, whereas in private settings, where signaling pressures diminish, choices reflect personal values and the private self. We conduct two choice experiments linking three wine cues—bottle appearance, short narratives, and tasting notes—to Schwartz's values and testing whether these cue-value links guide wine choices for private and professional contexts. Observed systematic differences would be consistent with individuals deriving context-dependent identity utility and signaling-based reputational utility, which would support context-specific targeting and price discrimination.

II. Theoretical background

When traits are hidden, individuals use observable actions to influence others’ beliefs. Classic signaling models explain education, conspicuous consumption, and prosocial behavior as signals of productivity, status, and reputation (Andreoni and Bernheim, Reference Andreoni and Bernheim2009; Bagwell and Bernheim, Reference Bagwell and Bernheim1996; Bénabou and Tirole, Reference Bénabou and Tirole2006; Spence, Reference Spence1973; Veblen, Reference Veblen1899). A signal is credible when it is less costly or more rewarding for true types, i.e., those who genuinely possess the signaled trait, than for imitators (Milgrom and Roberts, Reference Milgrom and Roberts1986). Education typically imposes lower costs on high-productivity workers, luxury purchases on the wealthy, and donations on genuinely prosocial individuals.

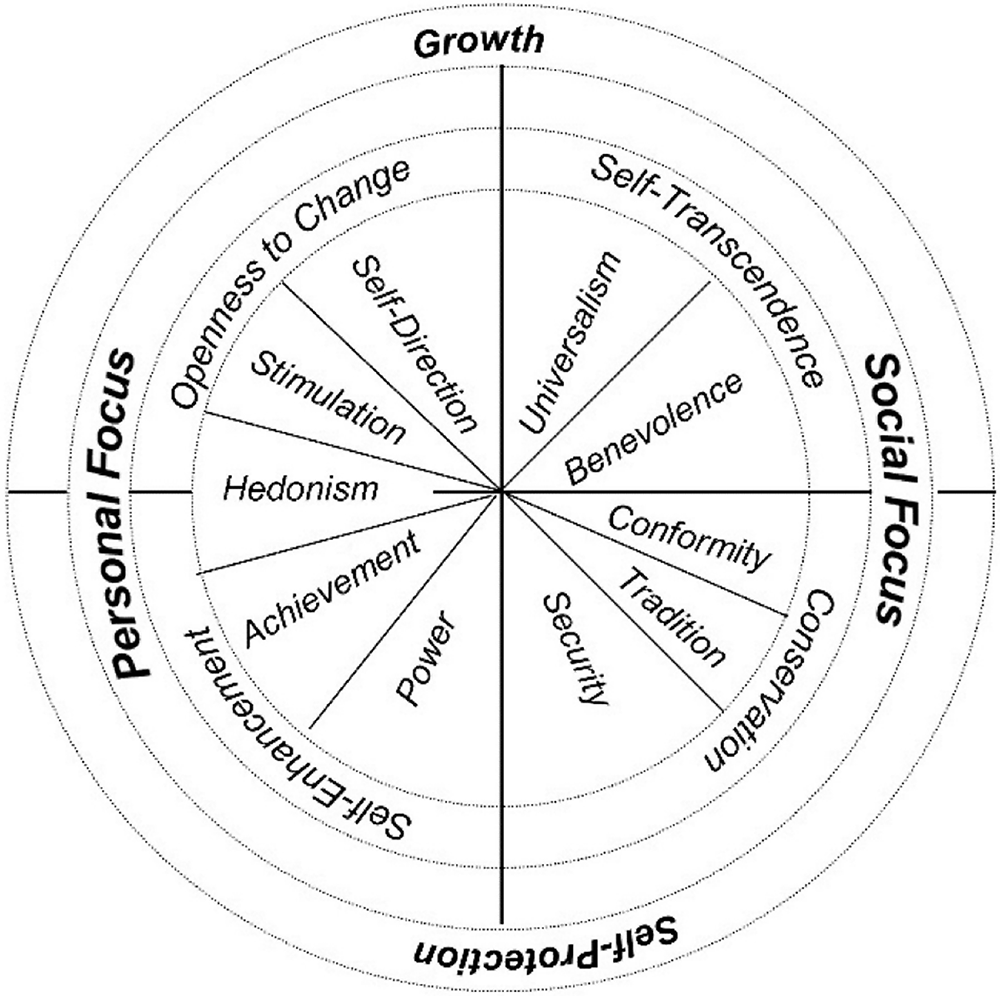

Extensive research in wine economics examines extrinsic product attributes as quality signals under asymmetric information; Storchmann and Cao (Reference Storchmann and Cao2025) provide a recent review. We extend this perspective by proposing that wine choices function as identity signals. Using Schwartz's framework, we operationalize identity as value priorities and treat product attributes as the signal vehicles from which observers infer those values, i.e., the signal content. Schwartz (Reference Schwartz1992) distinguishes 10 basic values, arranged in a circumplex with two higher-order dimensions: openness to change vs. conservation, and self-transcendence vs. self-enhancement; see Figure 1. Adjacent values are compatible, while opposing values conflict. The first dimension highlights the tension between valuing personal freedom and novelty (hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction) and upholding stability (conformity, tradition, and security). The second dimension highlights the tension between prioritizing the well-being of others (universalism and benevolence) and focusing on personal success (power and achievement). As stated, product attributes (“wine cues”) may act as signaling vehicles through which consumers convey their value priorities. We focus on cues observable at the point of sale and during consumption—bottle appearance, back-label narratives (“short stories”), and back-label tasting notes.

Figure 1. Circular structure of Schwartz value types.

III. Framework and research questions

For a signal to be effective, three conditions must hold: observability, interpretability, and type-dependent cost (Bénabou and Tirole, Reference Bénabou and Tirole2006; Spence, Reference Spence1973). Applied to wine as an identity signal, observability is satisfied in social settings: the receiver of the signal can observe wine choice; bottles are visible, and back-label text is often accessible. We contrast a professional context—high-stakes and observable—with a private context, defined as unobserved choice and consumption. Interpretability requires a shared codebook between senders and receivers. Receivers must reliably infer the same values from a given set of wine cues, and senders must be able to anticipate those inferences. We predict that this condition holds, and address it in our first research question:

RQ1 (Value attribution): Do individuals systematically attribute Schwartz values to wine cues, i.e., bottle appearance, short narratives, tasting notes?

Type-dependent costs follow from identity economics (Akerlof and Kranton, Reference Akerlof and Kranton2000): Adhering to the norms of a salient identity yields more identity utility for true types than for imitators. When expected reputational gains correlate with role norms—as arguably in professional contexts—conformity to the professional norm yields additional reputational utility via signaling. Thus, when the professional identity is salient and choices are visible, signals should credibly reveal the chooser's role values. When a private identity is salient and choices are unobserved, signaling pressures recede and utility is maximized by selecting wines that best match one's personal values. This leads to our second research question:

RQ2 (Context-dependent selection): Do individuals’ wine choices systematically differ between professional and private contexts, reflecting the value priorities activated by each identity?

Systematic professional–private differences would suggest that individuals hold multiple identities with distinct value priorities. Identity salience and observability shape utility by rewarding identity-consistent choices and, when choices are observed, adding reputational payoffs. We make this explicit with a simple utility framework (conceptual, not structural):

Here, ![]() $U\left( {w{\text{|C}}} \right)$ is the payoff from choosing wine w in context C (private or professional). PriFit(w) and ProFit(w) are the fit between the wine cue's value links and the chooser's private identity (i.e., personal values) and professional identity (i.e., values emphasized in the professional role).

$U\left( {w{\text{|C}}} \right)$ is the payoff from choosing wine w in context C (private or professional). PriFit(w) and ProFit(w) are the fit between the wine cue's value links and the chooser's private identity (i.e., personal values) and professional identity (i.e., values emphasized in the professional role). ![]() ${\text{Rep}}\left( {\text{w}} \right)$ measures expected reputation gains from observers’ inferences.

${\text{Rep}}\left( {\text{w}} \right)$ measures expected reputation gains from observers’ inferences. ![]() ${{{\lambda }}_1}$ = 1 in private contexts and 0 in professional ones, and

${{{\lambda }}_1}$ = 1 in private contexts and 0 in professional ones, and ![]() $\lambda_2$ = 1 in professional contexts and 0 in private ones. For completeness, wine preferences (e.g., preference for grape variety, region of origin, or color) and price could be added as +

$\lambda_2$ = 1 in professional contexts and 0 in private ones. For completeness, wine preferences (e.g., preference for grape variety, region of origin, or color) and price could be added as +![]() ${{\text{a}}_4}$Preferences(w) −

${{\text{a}}_4}$Preferences(w) − ![]() ${{\text{a}}_5}$Price(w);

${{\text{a}}_5}$Price(w); ![]() ${{\text{a}}_{i = 1,\ldots,5}}$ denote the weighting factors. In our experimental tasks, however, preferences and price are fixed (all wines are red Burgundy, Pinot Noir, at $28), so these components are constant and omitted from comparisons. Our framework assumes that expected reputational gains, Rep(w), are strongly correlated with professional-identity fit, ProFit(w). Consequently, observed choices in the professional setting credibly signal professional value priorities, whereas private choices reveal personal values.

${{\text{a}}_{i = 1,\ldots,5}}$ denote the weighting factors. In our experimental tasks, however, preferences and price are fixed (all wines are red Burgundy, Pinot Noir, at $28), so these components are constant and omitted from comparisons. Our framework assumes that expected reputational gains, Rep(w), are strongly correlated with professional-identity fit, ProFit(w). Consequently, observed choices in the professional setting credibly signal professional value priorities, whereas private choices reveal personal values.

To address our research questions, we ran two randomized choice experiments. Both studies received institutional ethics approval, and participants were compensated.

IV. Study 1

Study 1 tests whether consumers associate Schwartz values with three wine cues—bottle appearance, short stories, and tasting notes—and first tests whether these cue-value links produce context-dependent shifts in choice across private vs. professional settings.

a. Participant recruitment and screening

We recruited US-based participants on Amazon Mechanical Turk. Eligibility required responsibility for household wine purchases and an intention to buy wine in the next month. To ensure data quality, we limited participation to workers with more than 100 approved human intelligence tasks and a minimum 95% approval rate and included two attention checks. The final sample comprised 985 participants (46% male). The age distribution was centered on the 35–44 bracket; men were slightly underrepresented relative to the US population (∼49% male; United States Census Bureau (2022)).

b. Experimental design

Each participant completed two choice tasks framed as distinct contexts: (1) Professional context: choose a red Burgundy, i.e., a Pinot Noir, for a workplace dinner with one's boss and colleagues (participants have no information about others’ tastes). (2) Private context: choose a red Burgundy for relaxed consumption alone at home. In each task, participants chose one option from a set of four alternatives, all priced at $28 and presented as available from the participant's preferred wine shop.

Participants were randomly assigned to one of three groups. The first group chose from a choice set of four randomly assigned wine bottles. The second and third groups chose from a similar set; however, each bottle was accompanied by a randomly assigned short story or tasting note. Bottle appearance was included in every condition because it is the most salient, universally observable attribute—both online and in person. Even when back-label stories or tasting notes go unread, the bottle remains visible in settings such as workplace dinners. Stimuli for bottle appearances in Table 1; stories and tasting notes in Table 2; see Appendix A for choice-set examples.

Table 1. Included stimuli—bottles (B) 1–12

Note. All the wine images were obtained using the Vivino platform. Reference: Vivino (n.d.).

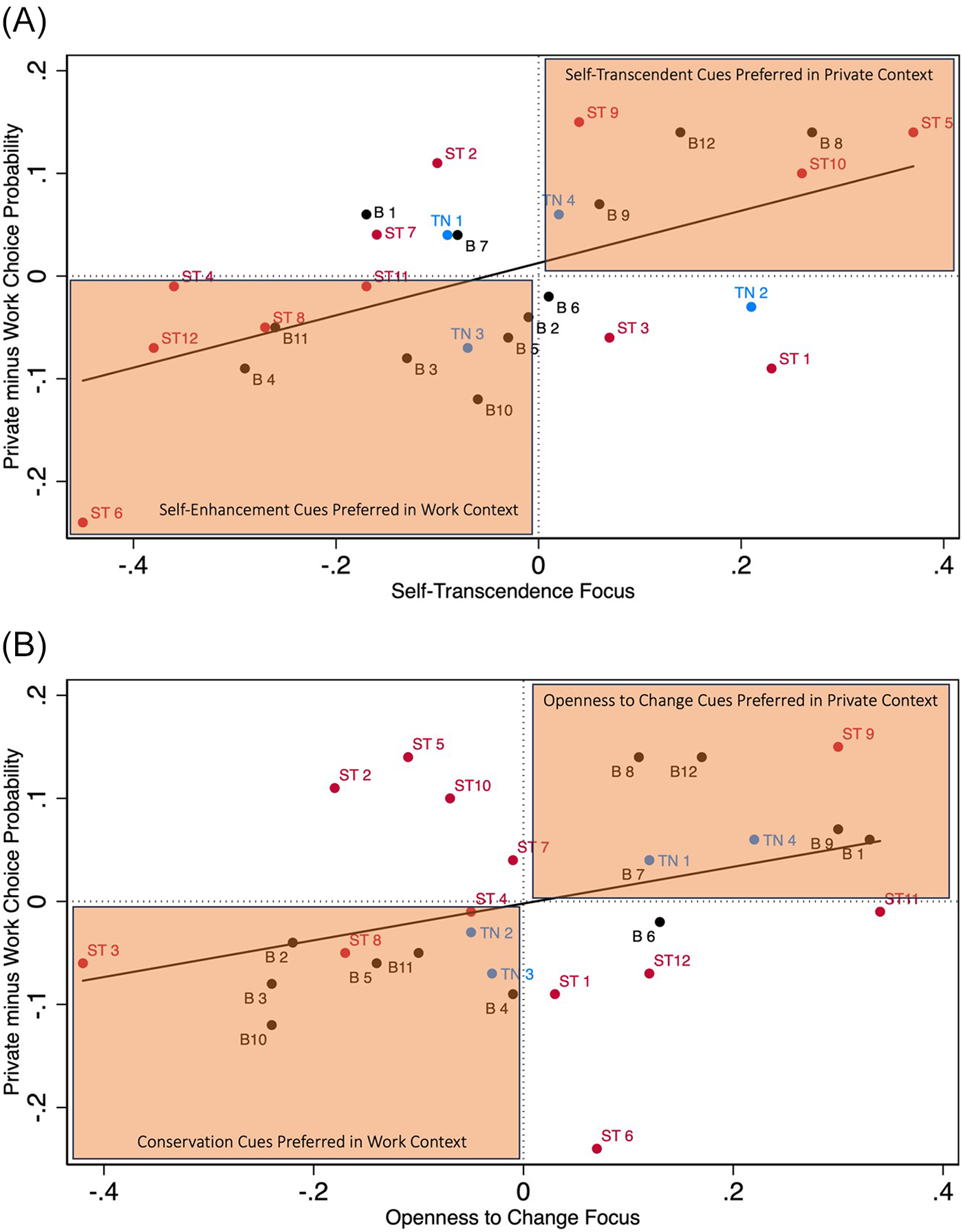

Table 2. Included stimuli: Short stories (ST) 1–12 and tasting notes (TN) 1–4

Note. Certain stories were adapted from online sources. References: Buvons Wine (n.d.); Domaine Mikulski (n.d.); Live Simple Wine (n.d.); Chavy-Chouet (n.d.); Liquor and Wine Outlets (n.d.); Moët and Chandon (n.d.).

Bottle appearances spanned traditional, modern, and non-conformist. Short stories covered the production or terroir ethos (e.g., respect for soil and vine), estate tradition (e.g., family heritage since 1859), third-party appreciation (e.g., consumer acclaim), or a note on philosophy (e.g., anti-materialist positioning). Tasting notes listed sensory descriptors (e.g., strawberry and nutmeg), reflecting typical Burgundy Pinot Noir profiles (red and black fruit, oak, spice, herbal facets). We expanded each pool until all co-authors agreed that additional items no longer added substantive variation, yielding 12 bottles, 12 stories, and 4 tasting notes.

Participants were instructed to use all available information when making each choice. An attention check followed each selection task to ensure engagement, requiring participants to recall the context of their recent choices. After the two choices, we displayed the attributes from the participant's choice sets individually. For each cue (bottle, story, note), participants indicated which of the 10 Schwartz values (if any) they associated with that cue.

c. Study 1 results

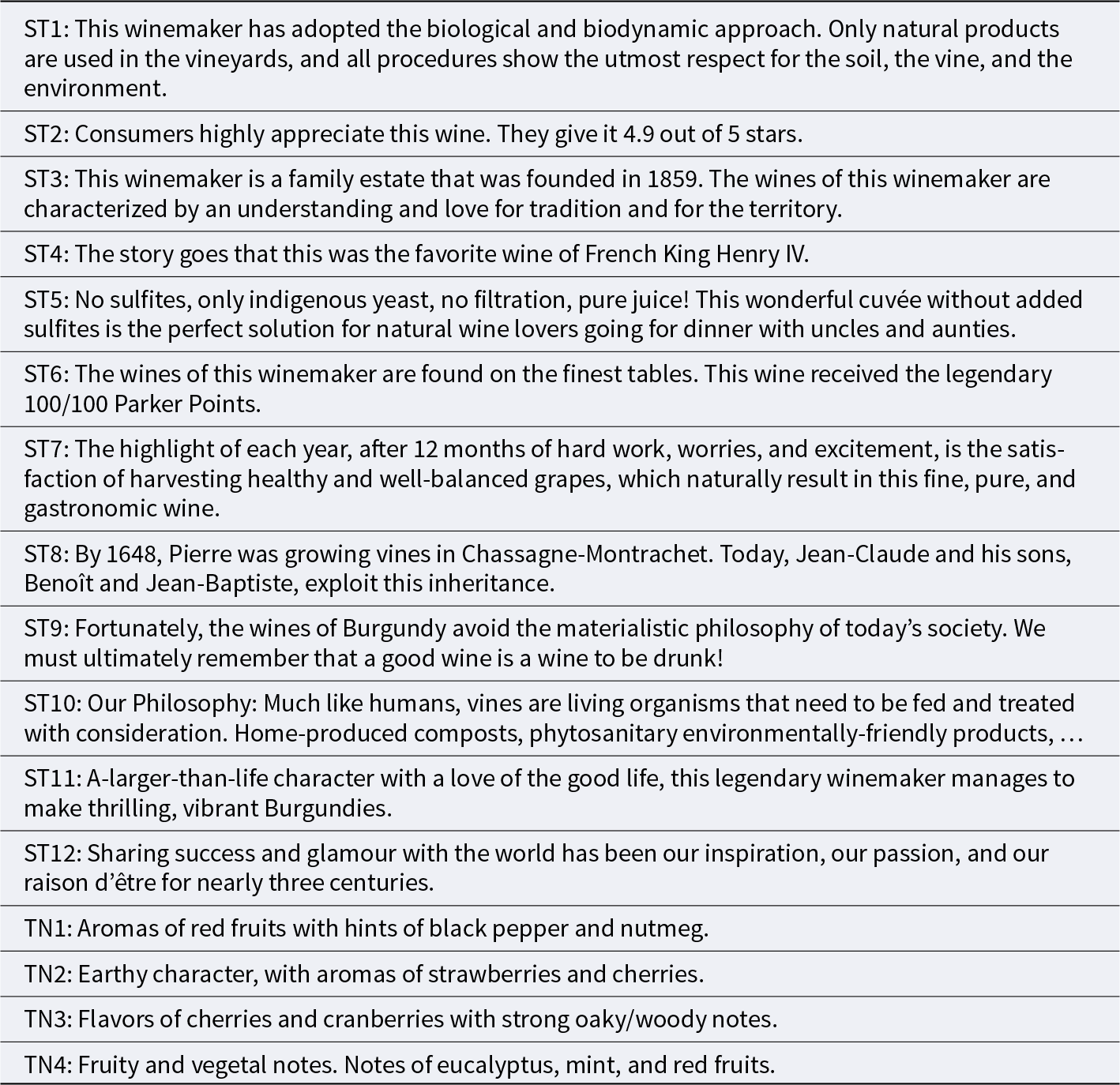

Participants reliably associated Schwartz values with wine cues, yielding a clear cue-value map (Table 3). For illustration, Bottle 10 was most strongly associated with tradition (by 65% of participants); Short Story 6 (“The wines of this winemaker are found on the finest tables. This wine received the legendary 100/100 Parker Points”) with achievement (77%); and Tasting Note 4 (“Fruity and vegetal notes. Notes of eucalyptus, mint, and red fruits”) with stimulation (48%). Overall, the findings suggest that attributes are value-laden and can function as signal vehicles to convey values, addressing RQ1.

Table 3. Share of participants associating each stimulus with each Schwartz value (Study 1)

Note. The share of participants who associated the bottles (B1–B12), short stories (ST1–ST12), and tasting notes (TN1–TN4) with the corresponding value. UN: universalism; BE: benevolence; TR: tradition; CO: conformity; SE: security; PO: power; AC: achievement; HE: hedonism; ST: stimulation; SD: self-direction

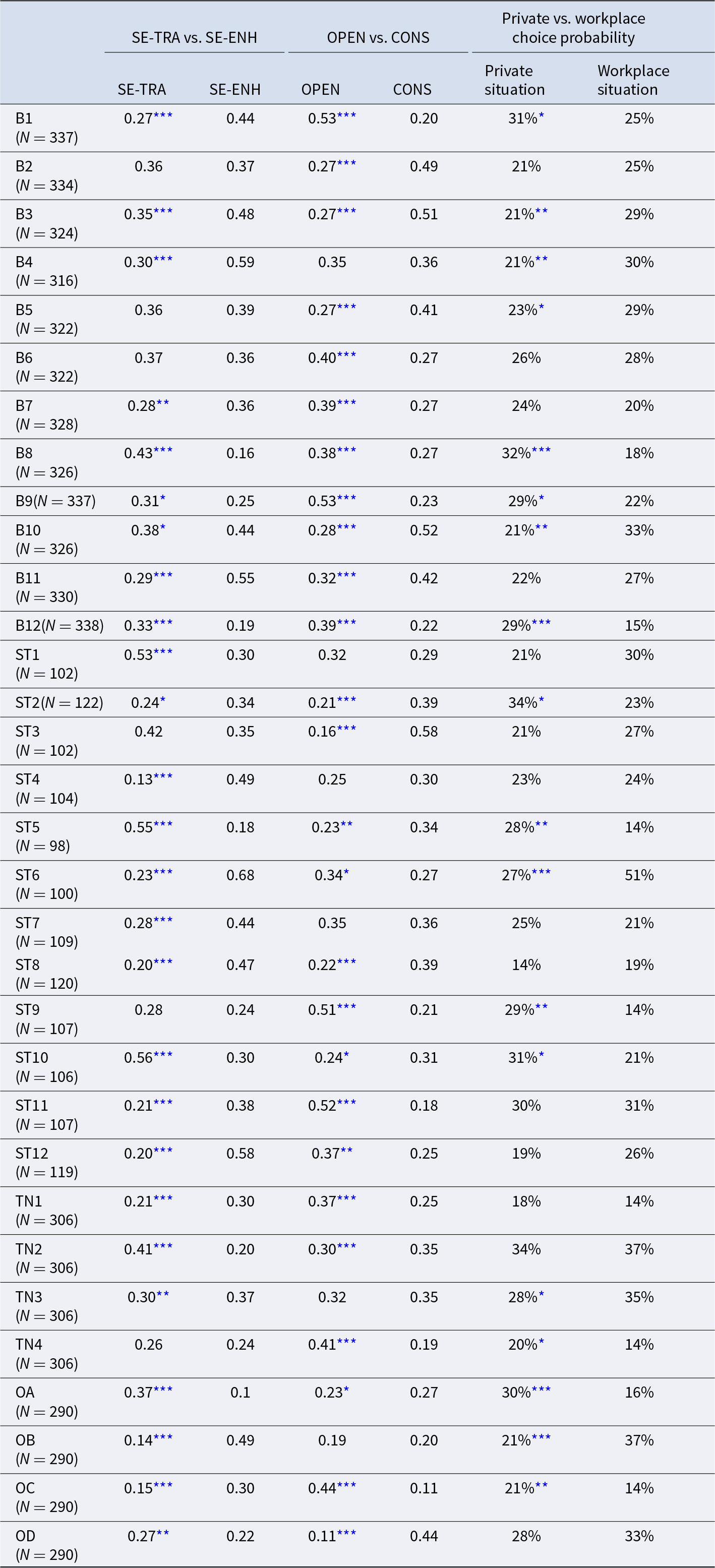

For each stimulus ![]() $j$, we convert the shares of participants who associated that stimulus with each Schwartz value into the four higher-order value orientations as follows:

$j$, we convert the shares of participants who associated that stimulus with each Schwartz value into the four higher-order value orientations as follows:

\begin{equation}SETR{A_j}\, = \,\left( {U{N_j} + B{E_j}} \right)/2\end{equation}

\begin{equation}SETR{A_j}\, = \,\left( {U{N_j} + B{E_j}} \right)/2\end{equation} \begin{equation}SEEN{H_j}\, = \,\left( {A{C_j} + P{O_j}} \right)/2\end{equation}

\begin{equation}SEEN{H_j}\, = \,\left( {A{C_j} + P{O_j}} \right)/2\end{equation} \begin{equation}OPE{N_j}\, = \,\left( {H{E_j} + S{T_j} + S{D_j}} \right)/3\end{equation}

\begin{equation}OPE{N_j}\, = \,\left( {H{E_j} + S{T_j} + S{D_j}} \right)/3\end{equation} \begin{equation}CON{S_j}\, = \,\left( {C{O_j} + T{R_j} + S{E_j}} \right)/3\end{equation}

\begin{equation}CON{S_j}\, = \,\left( {C{O_j} + T{R_j} + S{E_j}} \right)/3\end{equation}where SETRA = self-transcendence, SEENH = self-enhancement, OPEN = openness to change, CONS = conservation, UN = universalism, BE = benevolence, TR = tradition, CO = conformity, SE = security, PO = power, AC = achievement, HE = hedonism, ST = stimulation, and SD = self-direction. Each term denotes the share of participants who associated that value orientation or that basic Schwartz value with stimulus j. Full stimulus-level results are reported in Appendix B. To assess whether stimuli lean toward one pole of each higher-order dimension, we then form value focus indices:

where SETRAFO denotes the self-transcendence focus and OPENFO the openness to change focus. Positive values indicate that stimulus j is more closely associated with self-transcendence than self-enhancement, and with openness to change than conservation; negative values indicate the reverse.

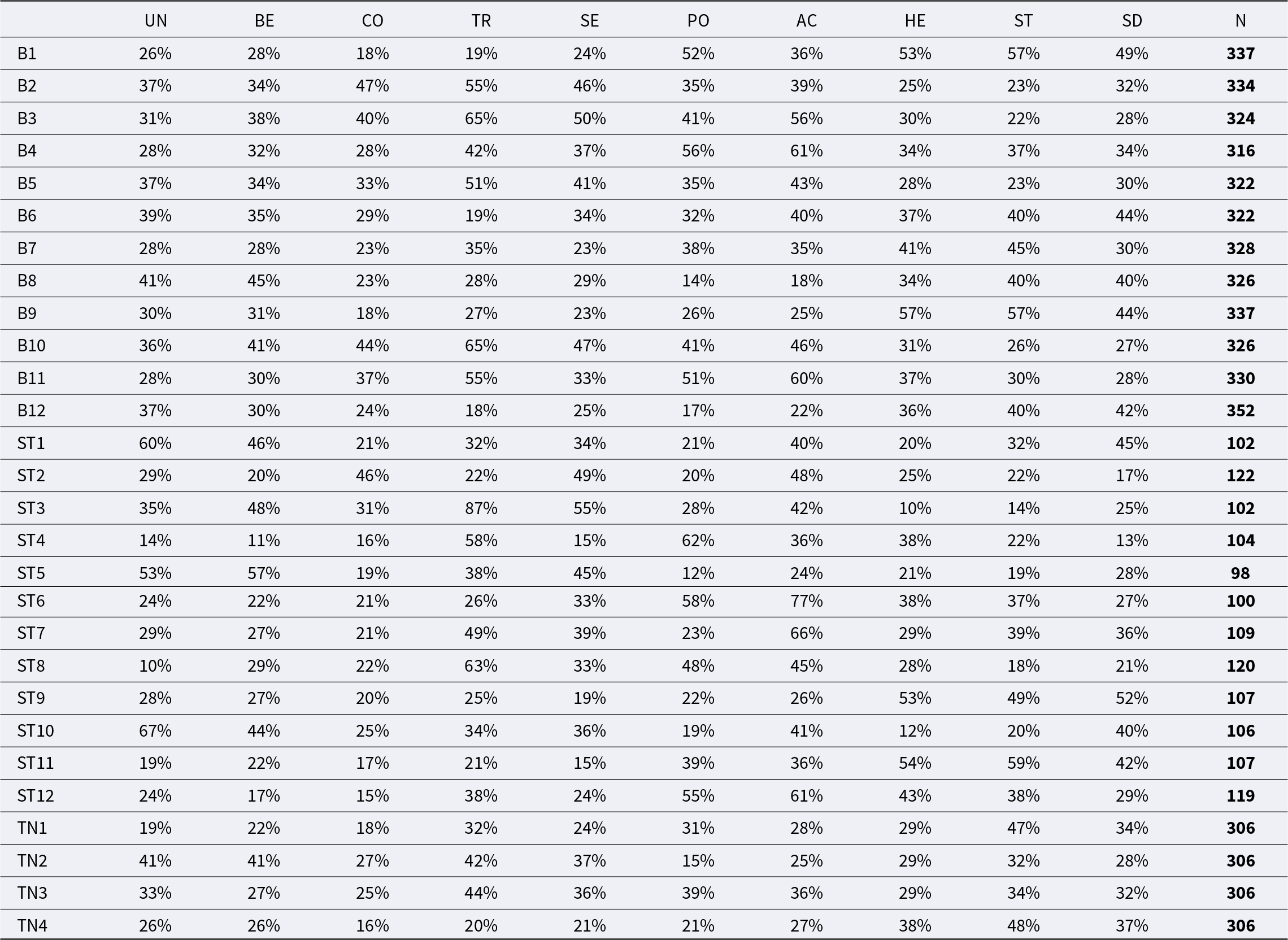

Figures 2A and 2B plot for each stimulus j (bottles in black, stories in red, notes in blue), the difference in choice probability between private and professional context on the y-axis (Pr(choose∣private)- Pr(choose∣work)) against ![]() $SETRAF{O_j}$ in Figure 2A and

$SETRAF{O_j}$ in Figure 2A and ![]() $OPENF{O_j}$ in Figure 2B on the x-axis. We find positive associations in both panels (r 2 = 0.32 for self-transcendence focus and r 2 = 0.13 for openness to change focus): stimuli leaning toward self-transcendence and openness to change are chosen relatively more in private settings, whereas stimuli leaning toward self-enhancement and conservation are chosen relatively more for professional settings. This pattern suggests that individuals gain context-dependent identity utility, as well as reputational utility through signaling. Individuals may prefer to project stability, reliability, and performance in professional settings, opting for wines that represent those values at work, whereas, in more personal environments, they may seek personal fulfillment and self-determination.

$OPENF{O_j}$ in Figure 2B on the x-axis. We find positive associations in both panels (r 2 = 0.32 for self-transcendence focus and r 2 = 0.13 for openness to change focus): stimuli leaning toward self-transcendence and openness to change are chosen relatively more in private settings, whereas stimuli leaning toward self-enhancement and conservation are chosen relatively more for professional settings. This pattern suggests that individuals gain context-dependent identity utility, as well as reputational utility through signaling. Individuals may prefer to project stability, reliability, and performance in professional settings, opting for wines that represent those values at work, whereas, in more personal environments, they may seek personal fulfillment and self-determination.

Figure 2. (A) Relationship between self-transcendence focus and context-dependent selection probability. (B) Relationship between openness to change focus and context-dependent selection probability.

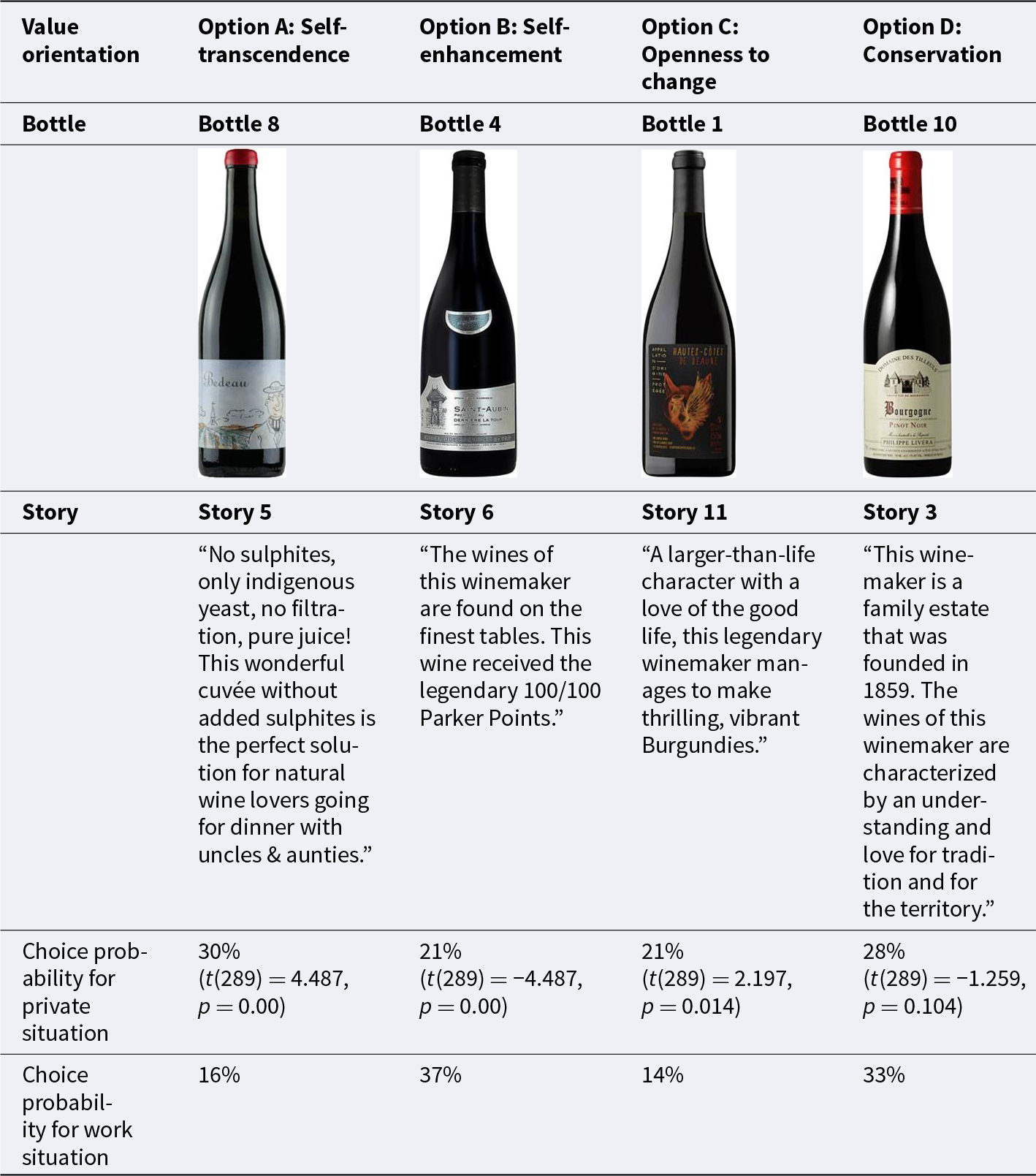

The results serve as guidelines for constructing a choice set for Study 2. Using the value focus indices, we assemble four value orientation-maximizing stimulus bundles (one bottle + one text, i.e., a story or a tasting note) that maximize self-transcendence, self-enhancement, openness to change, and conservation (Table 4). A ranking based on absolute association yields the same bundles except for a marginal swap within self-transcendence (Appendix B). Study 2 then assesses whether choice patterns vary by context when these bundles are presented.

Table 4. Study 2 choice set: Bottle–text bundles maximizing each value orientation

Note. Options combine the bottle and text (story or tasting note) that maximize each value orientation. Entries are choice probabilities. Private vs. work choice probabilities are tested with paired t-tests (two-tailed).

V. Study 2

Study 2 tests whether value associations embedded in wine cues influence context-dependent choices. Based on Study 1, we constructed four choice options that maximize each higher-order value orientation—self-transcendence, self-enhancement, openness to change, and conservation—by pairing a bottle with the story or tasting note that most strongly evokes the same orientation.

a. Participant recruitment and screening

We recruited US wine drinkers on Prolific using platform filters and included two attention checks. The final sample consisted of 290 participants (24% male; median age 37; median household income $70,000–$79,999; education: 19% high school, 58% college, 21% graduate studies). Age and household income approximated US benchmarks (US Census Bureau, 2022). Males were underrepresented relative to the adult population (∼49% male), and educational attainment was higher than national figures for individuals older than 25 (26% high school, 50% some college/bachelor's, 14% graduate/professional, 10% less than high school).

b. Experimental design

As in Study 1, each participant completed two choice tasks—one for a workplace dinner and one for a private at-home occasion. In Study 2, all participants chose from the same four options (Table 4); all framing matched Study 1.

As a robustness check, we directly measured personal and work values. Personal values were assessed with the 21-item Portrait Values Questionnaire (PVQ; Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2012; 1–6 scale). Work values were measured by appending, after each PVQ item, “How important is it for you to be seen as resembling this person in your professional environment?” (Hossli et al., Reference Hossli, Natter and Algesheimer2024; same 1–6 scale). These measures yield the same four higher-order orientations used in our design and allow a survey-based comparison of personal vs. professional value priorities.

c. Study 2 results

Mirroring Study 1, we first verified that each option was most strongly associated with its target orientation. Using the same aggregation procedure, we computed value focus indices for Options A–D. As intended, participants most often associated Option A with self-transcendence, B with self-enhancement, C with openness to change, and D with conservation (Appendix B), validating the construction of the choice set.

Replicating Study 1, participants preferred options aligned with self-transcendence and openness to change values more in private than in professional settings, and preferred options aligned with self-enhancement and conservation values more in professional than in private settings (Table 4). For example, 30% chose Option A (self-transcendence) in the private context vs. 16% in the workplace (Δ = 14 percentage points (pp)), t(289) = 4.487, p < 0.001. Conversely, 21% chose Option B (self-enhancement) in private vs. 37% at work (Δ = 16 pp), t(289) = −4.487, p < 0.001.

A robustness check using traditional value surveys yielded the same pattern. Self-transcendence was rated higher personally than at work (personal M = 5.08; work M = 4.83), t(289) = 13.311, p < 0.001; so was openness to change (personal M = 4.31; work M = 4.18), t(289) = 6.524, p < 0.001. Self-enhancement was rated slightly higher at work than personally (personal M = 3.85; work M = 3.90), t(289) = −3.052, p < 0.01. Conservation did not differ (personal M = 4.31; work M = 4.32), t(289) = −0.904, p = 0.18.

VI. Discussion and conclusion

The purpose of our two studies was to examine whether wine selection can function as an identity signal, conveying value priorities. Effective signaling requires three conditions: observability, interpretability, and type-dependent costs. We therefore contrast an observable, social setting—specifically a professional context, which is arguably high-stakes for many individuals—with a private consumption context, where choices are unobserved by others and thus create no incentive to signal. Interpretability further requires a shared code: individuals must ascribe the same meaning to observable cues, allowing senders and receivers to interpret the signal consistently. To address RQ1, Study 1 provides evidence that individuals reliably ascribe the four higher-order value orientations—self-enhancement, self-transcendence, openness to change, and conservation—to 28 wine cues spanning bottle appearance, short narratives, and tasting notes. Type-dependent costs follow from identity economics, which holds that individuals’ utility depends on conforming to the norms of a salient identity. Accordingly, wine choices in professional contexts may be interpreted as signals of professional identity. Addressing RQ2, we find that wine choices are strongly context-dependent, arguably reflecting the value priorities activated by the salient identity. In private settings, individuals favor wines associated with self-transcendence and openness to change; in professional settings, selections shift toward wines associated with self-enhancement and conservation. The private-context pattern mirrors evidence from value surveys conducted on representative samples and confirmed through large-scale replications: benevolence and universalism (self-transcendence) and self-direction (openness to change) consistently rank at the top of personal value priorities (Schwartz, Reference Schwartz2012; Schwartz and Bardi, Reference Schwartz and Bardi2001), a result replicated in our robustness check using the traditional Schwartz Value Survey. Conversely, the work-context pattern mirrors research that finds that conservation (e.g., order, rule-following, stability) and self-enhancement (e.g., achievement, performance, competence, status-seeking) values are often both commonly internalized as part of one's professional identity and externally reinforced through workplace expectations (Bolino et al., Reference Bolino, Long and Turnley2016; Leary and Kowalski, Reference Leary and Kowalski1990). Taken together, results support our utility framework: in private contexts, choices align with personal values; in professional contexts, choices align with values central to the professional identity.

Our findings suggest that wine choices can serve as a choice-based proxy for both personal and work-related values. This links our approach to revealed-preference theory (Samuelson, Reference Samuelson1948; Varian, Reference Varian2006), which infers individual preferences from observed choices. Our data suggest that choices reflect not only taste preference but also value priorities, contingent on identity salience. Such choice-based measures—ideally triangulated across additional product categories—can supplement traditional Schwartz surveys for the measurement of personal values and the Hossli et al. (Reference Hossli, Natter and Algesheimer2024) adaptation of work values, which essentially captures the values individuals aim to signal in professional settings.

Context-specific choice variation also suggests that the private self is, on average, not fully congruent with the professional self. Such divergence may undermine job satisfaction, as greater value congruence is associated with higher job satisfaction (e.g., Edwards and Cable, Reference Edwards and Cable2009; Kristof, Reference Kristof1996), and even life satisfaction (Hossli et al., Reference Hossli, Natter and Algesheimer2024). Arguably, the ideal scenario is congruence between private and professional selves. For example, an employee who values self-transcendence works at an environmental organization and brings an organic wine with a sustainability narrative to a work dinner. It aligns with the private self, reflecting the employee's personal values, whilst simultaneously fitting with the professional self, adhering to professional identity norms. At the same time, it enhances the reputation, as colleagues may interpret the choice as a signal of commitment to sustainability.

The signaling potential of wine also has market consequences. Context-specific choices enable identity-based segmentation. Retailers, restaurants, and wineries may even extract signaling premiums by framing certain wines as signals of reliability or status, much like business attire commands higher prices relative to casual wear. Wineries could also implement third-degree price discrimination by charging different prices to different consumer segments for essentially the same product by offering the same wine with varied packaging or cues tailored to professional vs. private contexts.

Although this study provides valuable insights, it also has some limitations. The sample, although representative of the US population in certain aspects, had an underrepresentation of men (only Study 2) and higher educational attainment than the general population. Future research should examine whether results hold in more gender-balanced populations. It is known, for example, that women, on average, value self-transcendence more than men (e.g., Lechner et al., Reference Lechner, Beierlein, Davidov and Schwartz2024), which may affect results. Furthermore, because this study focused on the US population, our findings may not apply to other cultures with different work practices. Hence, exploring additional aspects, such as cultural background, could further enrich our understanding of the relationship between wine cues, values, and context-specific choices. Future studies could also explore these questions in real-world settings with a wider range of cues.

Acknowledgements

We thank the anonymous reviewers and the editor, Karl Storchmann, for their constructive guidance throughout the review process and for suggestions that greatly improved the paper. This research was supported by the University Research Priority Program “Social Networks” at the University of Zurich.

Declarations of interest

None.

Appendix A.1. Example of choice set for Group 1 (stimuli: wine bottle only)

Appendix A.2. Example of choice set for Group 2 (stimuli: wine bottle accompanied by short story).

Appendix A.3. Example of choice set for Group 3 (stimuli: wine bottle accompanied by tasting note).

Appendix B. Stimuli, value orientation, and context-specific choice probability

Note. Strength of association in Study 1 between the bottles (B1–B12), short stories (ST1–ST12) and tasting notes (TN1–TN4), and in Study 2 between the options (OA-OD) and the corresponding value orientation: Association with self-transcendence (calculated as the average share of participants who associated the values universalism and benevolence with the wine cue), self-enhancement (calculated as the average share of participants who associated the values power and achievement with the wine cue), openness to change (calculated as the averages share of participants who associated the values of hedonism, stimulation, and self-direction with the wine cue), and conservation (calculated as the average share of participants who associated values of conformity, tradition, and security with the wine cue). Choice probabilities reflect the probability that the wine cue or option was chosen for the private as well as the work situation if it was in the choice set. Significant differences, according to t-tests, between self-transcendence and self-enhancement, openness to change and conservation, as well as private and work choice probabilities, are marked.

* p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, and ***p < 0.001