The genus Zaglossus is known only from the island of New Guinea. On the IUCN Red List the eastern long-beaked echidna Zaglossus bartoni is categorized as Vulnerable and Attenborough’s long-beaked echidna Zaglossus attenboroughi and the western long-beaked echidna Zaglossus bruijnii are categorized as Critically Endangered. The western long-beaked echidna prehistorically also occurred in Australia, and it has been proposed that a small population may persist in Australia’s West Kimberley (Helgen et al., Reference Helgen, Miguez, James and Lauren2012). Because of their unique evolutionary history and threatened status, all three species of Zaglossus are recognized as priorities for global mammal conservation by the Zoological Society of London’s EDGE of Existence programme (EDGE of Existence, 2024).

Although hunting of relatively large mammals including Zaglossus species has occurred for millennia in New Guinea (Mack, Reference Mack2015), > 40% of non-flying mammal species now have a declining population trend as a result of unsustainable exploitation (Woinarski & Fisher, Reference Woinarski, Fisher, Cáceres and Dickman2023). The greatest threat to long-beaked echidnas is probably hunting for food (Pattiselanno, Reference Pattiselanno2006; Baillie et al., Reference Baillie, Turvey and Waterman2009; Leary et al., Reference Leary, Seri, Flannery, Wright, Hamilton and Helgen2016). Additionally, habitat loss from mining, logging, industrial plantations and agriculture probably poses a serious threat (Baillie et al., Reference Baillie, Turvey and Waterman2009; Leary et al., Reference Leary, Seri, Flannery, Wright, Hamilton and Helgen2016; Pattiselanno & Koibur, Reference Pattiselanno and Koibur2018). The Red List account of the western long-beaked echidna (last updated in 2015, and published in 2016) concords with information from the 1980s and 1990s (Menzies, Reference Menzies1991, Lavery & Flannery, Reference Menzies2023) that the species has only been recorded on the Vogelkop Peninsula (north-west New Guinea) and the adjacent land-bridge island of Salawati (it is probably now extinct on the latter). The Vogelkop Peninsula has a high diversity of vertebrates, and high mammal endemism (Lavery et al., Reference Lavery, Fisher, Flannery and Leung2013). However, prior to this study, there were only 11 records of western long-beaked echidnas on the Vogelkop Peninsula, and only six verified records (all captures) since the 1980s (Table 1).

Table 1 Details of all known observations of the western long-beaked echidna Zaglossus bruijnii, on the Vogelkop Peninsula, New Guinea, Indonesia (Fig. 1). We have not included records on the islands of Waigeo and Supiori (Menzies, Reference Menzies1991), as the basis of these is unknown and reliability is doubtful (Lavery & Flannery, Reference Lavery and Flannery1993).

During 24–30 July 2023, following reports of the species, we surveyed the forests around Klalik Village in Sorong Regency, together with local villagers (a team of eight people). We did not locate the western long-beaked echidna, although we found nose pokes (imprints in moist ground created during Zaglossus foraging; Plate 1). In July 2023 conditions were dry, so it was difficult for the survey team and villagers to find nose pokes or tracks. Returning in the first week of October 2023, a team of 10 researchers from the University of Papua and Fauna & Flora Indonesia, accompanied by villagers from Klalik, revisited the Klalik forests. Members of the team individually interviewed 17 active or retired hunters who identified themselves as knowledgeable about local plants and animals. We located these people through chain referral sampling in Klalik village (ASA, 2011).

Plate 1 Imprint of a western long-beaked echidna Zaglossus bruijnii nose poke near Klalik Village, with a pen for scale.

We asked the active and retired hunters, in Bahasa Indonesia, about their knowledge of the western long-beaked echidna. We asked them to describe the species, its behaviour, signs, locations where they had seen echidnas, and any other information they thought was pertinent. Nine of the 17 interviewees were familiar with the species and described recent sightings in the Klalik region. In the local Papuan dialect this species is called babi duri. When we showed them a photograph of the western long-beaked echidna, the interviewees stated that the species occurs in hilly forest areas with slopes of 30–45o, close to streams in open areas, where the forest floor is densely covered with damp soil and rocks, leaf litter and broken and decaying tree trunks. Common tree species in these forests include the argus pheasant-tree Dracontomelon edule, merbau Instsia palembanica, matoa Pometia pinnata, Spothiostemon javensis, milkwood Alstonia scholaris, gnemon Gnetum gnemon and tropical chestnut Sterculia parkinsonii (Plate 2).

Plate 2 Typical forest near Klalik Village where we sighted two western long-beaked echidnas.

We first saw a western long-beaked echidna in the Klalik forests in October 2023. In the same month, Darwis et al. (Reference Darwis, Hormes, Mohamad, Reza, Nita and Aksamina2023) observed a western long-beaked echidna in South Sorong Regency (Fig. 1). The two echidnas we observed had dark brown to black fur with spines on the flanks and back, a long downward curving nose, and feet with three claws, similar to the description in Flannery (Reference Flannery1995). We located these echidnas at a walking distance of c. 30 minutes from Klalik village. Three teams of guides searching with spotlights detected imprints of nose pokes before locating an echidna at 23.32 in an area of dense vegetation close to a stream, at 75 m altitude. This contrasts with the habitat of the western long-beaked echidna we sighted in Bintuni in 2018, which was muddy, with numerous fallen and decaying trees and forest floor covered by scrub, leaf litter and hollow logs, at 1,500–2,500 m (Pattiselanno et al., Reference Pattiselanno, Iriansul, Barnes and Arobaya2021; Table 1). During the following night, three groups of observers followed tracks and one group located an echidna (Plate 3), at 21.12. This echidna was c. 125 m from limestone caves, moving uphill on a slope of 30–45o (similar hilly habitat as that described by Opiang, Reference Opiang2009, for the eastern long-beaked echidna Z. bartoni).

Fig. 1 Locations of all known records of the western long-beaked echidna Zaglossus bruinjii (Table 1) in New Guinea.

Plate 3 One of the two western long-beaked echidnas sighted in forest near Klalik Village in October 2023.

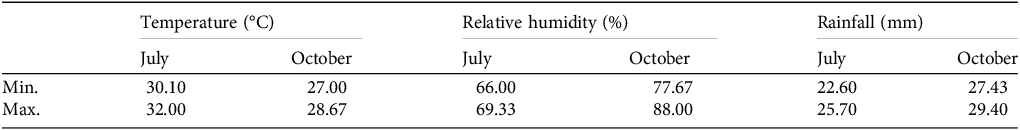

During the week before our survey, there was heavy rain in Sorong Regency and Klalik village, which made the forest floor wet and muddy, and the water flow in the stream was high. In our earlier survey in July 2023, when we did not locate echidnas, conditions were drier (Table 2); there had been no rain in the previous 2 weeks, and a strong southerly wind had resulted in dry leaves covering the forest floor, making it hard to detect nose poke signs or tracks. The detection of older tracks (c. 1 week old) in Klalik forest, during the second night of our July survey, indicates that echidnas may be less active in drier weather.

Table 2 Mean minimum and maximum temperature, humidity and rainfall in the forests of Klalik Village, recorded during our July and October 2023 surveys for the western long-beaked echidna. Data were recorded three times a day, at 6.00, 12.00, and 18.00, using a portable weather meter.

Based on studies in captivity, Grigg et al. (Reference Grigg, Beard, Barnes, Perry, Fry and Hawkins2003) suggested that Zaglossus species have periods of inactivity lasting > 24 h, when their body temperature drops. Our observations suggest that the echidna is less active when the forest floor is dry, as this impedes foraging. Zaglossus species prefer relatively wet and humid places in which to search for earthworms by poking their long snout into damp soil (Flannery, Reference Flannery1995). Most of our observations of the species have been in damp conditions after rain.

According to Ronsumbre (Reference Ronsumbre2007), Z. bruijnii was sighted in Pegunungan Arfak Regency at 1,000–1,380 m. Flannery & Groves (Reference Flannery and Groves1998) stated that western long-beaked echidnas have an elevational range from the lowland forest of Salawati Island (113–118 m; Darwis et al., Reference Darwis, Hormes, Mohamad, Reza, Nita and Aksamina2023) to 2,250 m in Pegunungan Arfak. In the latter, the temperature at the time of the sightings was 17–24 °C and the humidity 77–94% (Ronsumbre, Reference Ronsumbre2007), slightly cooler and drier than conditions in South Sorong Regency at the time of sightings (23–28 °C, 98% humidity; Darwis et al., Reference Darwis, Hormes, Mohamad, Reza, Nita and Aksamina2023).

In our study in northern Sorong Regency, all individuals were observed outside protected areas in established forest near streams rather than in disturbed marginal habitats. This suggests that the species may be widespread in the largely intact forest of the Vogelkop Peninsula (Fisher Reference Fisher2011). In Tembuni, Bintuni Regency, hunting of the species is considered taboo (Pattiselanno et al., Reference Pattiselanno, Iriansul, Barnes and Arobaya2021), but in Klalik, people acknowledged during the interviews that this echidna is consumed by local people. Echidnas in general, and Zaglossus species in particular, grow and reproduce slowly for a mammal of their size (Flannery, Reference Flannery1995; EDGE of Existence, 2017), so they are particularly susceptible to exploitation, as they cannot readily compensate for excess mortality (Fisher & Owens, Reference Fisher and Owens2004).

These records of the western long-beaked echidna are the first confirmed sightings in Sorong Regency, and suggest, along with information from the interviews, that the species persists there. An ecotourism initiative has begun in the Klalik forest in which local people take visitors on spotlighting tours to observe and photograph western long-beaked echidnas. The presence of this species in these forests may therefore provide an incentive to local communities not to place snares in the forest, in favour of ecotourism.

The new records and other recent sightings confirm that this Critically Endangered and evolutionary distinct species still occurs at multiple locations on the Vogelkop Peninsula. Further surveys are required to document its current distribution, and to examine local perceptions of the conservation of this species and, potentially, to involve the local community in the monitoring of this poorly-known, threatened monotreme.

Author contributions

Fieldwork: FP, OP, AL, AYS, MJ, NA, FD, MR; project planning: FP, DOF; writing: FP, AYS, DOF.

Acknowledgements

We thank the local government and people from Klasow District of Sorong Regency for granting us permission to conduct our study; and the interviewees in Klalik, clan of Malak, Sorong Regency, for their participation and permission to identify and measure the echidnas. We acknowledge the support of the Darwin Initiative, the IUCN Species Survival Commission Australasian Marsupial and Monotreme Specialist Group, two Species Survival Commission Internal Grants and a Species Survival Commission EDGE Internal Grant.

Conflicts of interest

None.

Ethical standards

This research followed the ethical guidelines of the Association of Social Anthropologists of the UK and Commonwealth (ASA, 2011), and abided by the Oryx guidelines on ethical standards. No animal or human ethics permits from the principal investigator’s institution (Universitas Papua) were required for this study.

Data availability

Data sharing is not applicable to this article.