The Maldives Heritage Survey is a collaboration between the Oxford Centre for Islamic Studies, the Earth Observatory of Singapore, SAIELab at Washington University in St Louis, and the National Center for Cultural Heritage under the Ministry of Arts, Culture and Heritage in the Maldives. The Maldives is an Indian Ocean archipelago of low-lying coral atolls that consists of 1192 islands, fewer than 200 of which are currently inhabited. The islands have been an important site on the historic maritime crossroads facilitating the circulation of peoples, goods and ideas across the Indian Ocean world—with significant commercial and cultural connections to Africa, Arabia, India, Sri Lanka, Indonesia and China. These islands have at various points been the location of Buddhist monastic communities, a Muslim sultanate beginning in the twelfth century (and visited by Ibn Battuta in the fourteenth), and a brief Portuguese occupation in the sixteenth, as well as in turns a Dutch and a British protectorate before the establishment of the modern state in 1968 (Feener Reference Feener, Fleet, Krämer, Matringe, Nawas and Rowson2021).

Beyond its broad outlines, the history of these islands is little known due to the lack of documentary sources available for its study. Since the pioneering work of Bell (Reference Bell1922), the ceramic sherd collection by Carswell (Reference Carswell1975), and the more systematic excavations done by Skjølsvold (Reference Skjølsvold1991) and Mikkelsen (Reference Mikkelsen1991, Reference Mikkelsen2000) following in the wake of Heyerdahl's (Reference Heyerdahl1986) ‘Maldive Expedition’, little archaeological work had been done until a recent wave of new activity in the field by Haour et al. (Reference Haour, Christie and Jaufar2016, Reference Haour, Christie, Jaufar and Vigoureux2017), Jameel (Reference Jameel2017), Pradines (Reference Pradines2018) and Jaufar (Reference Jaufar2019). An open-access library offering a fuller bibliography of publications is available on the Maldives Heritage Survey website. These excavations and architectural studies have produced a new level of detailed knowledge about several early Islamic sites. As a complement to these precision-focused investigations, our work provides the first ever comprehensive survey of the tangible cultural heritage of the Maldives. This enables us to map the spatial distributions of Buddhist, Islamic and other historic and archaeological sites across the entire country.

Completing this work is urgent as the low-lying islands of the Maldives face existential threats from climate change and other forms of environmental stress, as well as vulnerabilities to human acts of vandalism and destruction. These factors have motivated our work to locate, document and make an inventory of endangered tangible cultural heritage and to create an open-access and permanently archived record of the Maldivian past.

We conducted two years of full-time field survey from April 2018 until 2020. We surveyed 152 islands across six atolls (Figure 1) and documented over 292 sites with 1171 structures, 5761 small objects, in addition to digitising 410 manuscripts in Dhivehi and Arabic (Table 1). Sites were located using a combination of archival research, consultation with local communities and systematic field-walking. We documented each site with a combination of mapping and measurement, photography, field notes and oral histories. We used photogrammetry and a Faro Focus lidar station to record high-resolution 3D data for complex architectural features and select objects. The current condition of each site was evaluated and possible threats from environmental and other sources identified. Alongside the primary fieldwork, we also worked with institutions outside the Maldives to digitise relevant materials from their collections. Records for each site, structure and object, along with archives of digitised manuscripts, 3D visualisations and other resources, are open access on the project website. Full datasets for lidar scans of sites and structures are also made freely available through OpenHeritage3D. Project data are permanently archived within the Oxford Research Archive of the University of Oxford's Bodleian Library system.

Figure 1. Atolls in the Maldives included in the Maldives Heritage Survey (map by the Maldives Heritage Survey, courtesy of Google Earth).

Table 1. Database records created by the Maldives Heritage Survey, 2018–2020.

Our work has contributed significantly towards generating new knowledge about the history of the Maldives, contextualising the limited work that had been done previously at a small number of select sites by creating a new map that spatialises historical patterns of settlement and the establishment of Buddhist and Islamic ritual sites across the archipelago. For purposes of illustration in this brief note we present some of our key findings by atoll.

Laamu

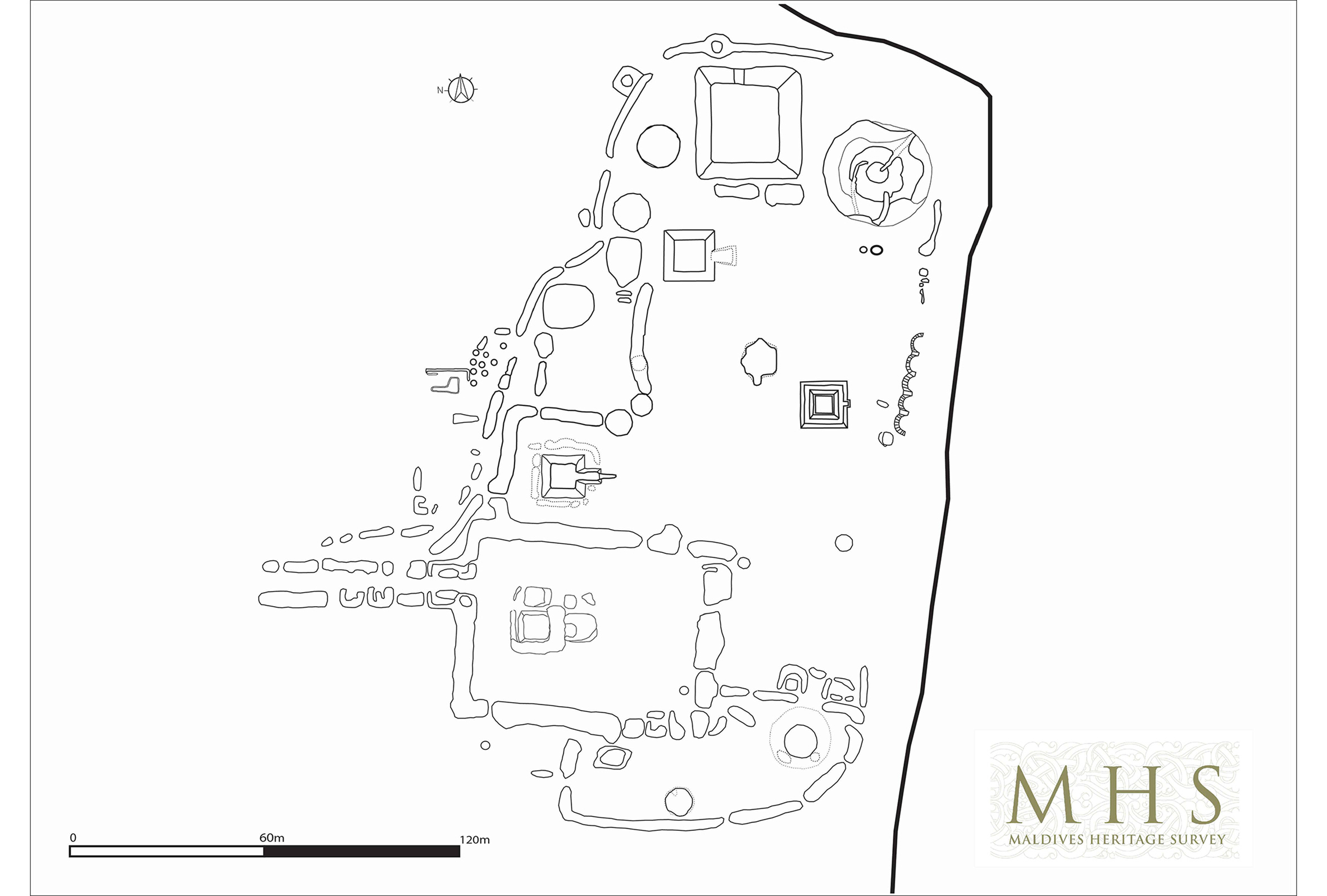

On the island of Gan a large artificial mound site had been documented by Bell (Reference Bell1922) in one of the rare earlier archaeological explorations of the Maldives. While Bell and his team identified nine structures on this site (Figure 2), our work there documented the ruins of dozens of additional structures and earthworks, allowing us to map the actual extent and spatial organisation of this major Buddhist ritual complex for the first time (Figure 3).

Figure 2. Site plan by Bell (Reference Bell1922), rotated for north orientation.

Figure 3. Site plan of the pre-Islamic mound site on Laamu Gan (LAM-GAN-2) by the Maldives Heritage Survey (2018).

On the same island a coral stone boulder carved with a kala head on one face (Figure 4) and Sanskrit inscription of a Buddhist mantra on its reverse (Figure 5) was recovered for the Maldives National Museum.

Figure 4. Face of the coral stone head from Laamu Gan (LAM-GAN-1-SO1; photograph by the Maldives Heritage Survey).

Figure 5. Reverse of the coral stone head from Laamu Gan (LAM-GAN-1-SO1) with Sanskrit inscription (photograph by the Maldives Heritage Survey).

An interactive 3D model of this piece can be accessed on the project website.

Gnaviyani

On Fuvamulak we documented another large Buddhist sanctuary comprised of stupas and other ruins in the vicinity of a large artificial mound. We also mapped early mosques and Muslim burial grounds around the Buddhist site, thus revealing a topography of religious change on the island.

Seenu

On the island of Hulhumeedhoo we surveyed Koagaanu—the largest historic cemetery in the Maldives. It contains 1535 carved coral gravestones, five mosques and numerous other structures, including the shrine mausoleum of a saint traditionally credited with the Islamisation of the island in the twelfth century.

Haa Alifu

In the northernmost atoll of the country the ruins of saints’ shrines and recital halls for Islamic devotional texts read to celebrate the birth of the Prophet were documented. The ritual activities that defined these sites were once widespread across the Maldives and the broader Indian Ocean world, but have almost completely disappeared in the country since the last quarter of the twentieth century.

Kaafu

New field-survey work in this atoll was combined with the enhancement of existing documentation and integration of that data into our open-access online archive. This has allowed us to build upon Mikkelsen's (Reference Mikkelsen2000) work at the Buddhist site on Kaashidhoo. In Malé we integrated heritage documentation produced by teams from the Maldives National Defence Ministry and Water Solutions Ltd for the great Friday Mosque into our database and provided additional contextual information on this and other sites in the nation's capital.

Discussion

Our work in the Maldives has furthered knowledge of the spatiality of historical religious transformations in the Maldives, and has provided the most comprehensive documentation yet of structures at a number of Buddhist ritual mound complexes. Another major contribution of the project has been the recording of vanishing traces of sites and structures associated with earlier forms of Islamic religious practice in the country. Tomb shrines and dedicated halls for the ritual recitation of devotional texts were once common across these islands and much of the broader Indian Ocean world, but have been largely abandoned over the past half century in the face of new visions of Islamic reform.

Beyond specifically religious sites, our survey also recorded vernacular architecture and related aspects of material culture to provide an invaluable resource documenting the changing dynamics of daily life and local cultural practices through to the present day.

Over the past three years we have made considerable progress towards our goal, but much work remains to be done. Between 2020 and 2025 we will complete our survey of the Maldives and begin to expand operations to Sri Lanka, Indonesia, Brunei and Vietnam under the new rubric of the Maritime Asia Heritage Survey, with continuing support from the Arcadia Fund. This will allow us to produce a comprehensive archive of the rich cultural heritage of interconnectivity across Maritime Asia, which will be made freely available online and permanently archived in secure digital repositories.

Acknowledgements

This work comprises Earth Observatory of Singapore contribution 346. We are grateful to Jost Gippert and Arlo Griffiths for deciphering the Sanskrit inscription in Figure 5.

Funding statement

The Maldives Heritage Survey was supported by the Arcadia Fund, a charitable fund of Lisbet Rausing and Peter Baldwin (project 3984).