Primary tic disorders are categorised in the DSM-5 by the presence and persistence of motor and/or vocal tics, 1 and include Tourette syndrome, provisional tic disorder, persistent motor tic disorder and persistent vocal tic disorder. Individuals with tic disorders often describe a premonitory urge as a sensation of building pressure, tension or needing to scratch an itch; completing the tic gives individuals a sense of relief. Reference Brandt, Essing, Jakubovski and Müller-Vahl2 Persistent tic disorders affect approximately 1% of children and adolescents. Reference Knight, Steeves, Day, Lowerison, Jette and Pringsheim3 Tics usually start at age 5–7 years, and their severity fluctuates throughout childhood; typically, tic severity is highest in early adolescence. Reference Kumar, Trescher and Byler4

Researchers have not discovered a direct cause or cure for tic disorders, although twin and family studies indicate a heritability of 60–80%, highlighting the strong influence of genetics. Reference Abdallah, Fernandez, Martino and Leckman5 Current treatment guidelines focus on reducing tic severity. Reference Pringsheim, Okun, Müller-Vahl, Martino, Jankovic and Cavanna6 Children and adolescents with severe tics may find them disruptive or distressing, as they often pose academic and social challenges. Reference Eapen and Usherwood7 To effectively mitigate the negative impacts of tic disorders, specific factors associated with worse tic severity have been explored. Known influences on tic severity include medical factors (i.e. the presence of comorbid disorders Reference Lebowitz, Motlagh, Katsovich, King, Lombroso and Grantz8,Reference Pringsheim9 ), biological factors (i.e. family history) Reference Mataix-Cols, Isomura, Brander, Brikell, Lichtenstein and Chang10,Reference Eysturoy, Skov and Debes11 and contextual factors (i.e. effects of environment or situation). Reference Himle, Capriotti, Hayes, Ramanujam, Scahill and Sukhodolsky12,Reference Barber, Ding, Espil, Woods, Specht and Bennett13

Most children can describe situational or environmental factors that trigger, reinforce or perpetuate their tics, suggesting that tics are influenced by environmental contingencies. Antecedents of tics can be internal or external to the individual. Internal antecedents include mood states, thoughts or premonitory sensations, whereas external antecedents include settings, activities or specific people. Consequences are outcomes contingent on tics that increase or decrease the likelihood of tics within a specific antecedent context. The most common internal consequence is temporary relief of premonitory sensations, whereas external consequences usually involve social reactions. Reference Himle, Capriotti, Hayes, Ramanujam, Scahill and Sukhodolsky12

This study aims to further our understanding of contextual factors influencing tic severity, by exploring if tic severity is influenced by calendar month. There is comparatively little research in this area. In the setting in which the population of the Canadian province of Alberta lives, there are large variations in outdoor temperatures, hours of daylight and environmental stressors based on calendar month. Personal communications with children and families suggest that tics worsen at the start of the school year (September) and improve during the summer school vacation (July and August). We aimed to expand on this clinical observation by using data collected systematically in our prospective longitudinal registry, with and without adjustment for other factors known to influence tic severity, including age, gender, comorbidity and treatment for tics. We hypothesised that tic severity would be lowest during the months of July and August, during which time children have a break from school, daylight hours are long (14–16 h) and temperatures are warm (mean temperature 16–17 °C).

Method

Calgary Child Tic Disorders Registry

Children with tic disorders clinically evaluated at the Calgary Tourette and Pediatric Movement Disorders Program are invited to participate in a longitudinal observational study at their first clinical visit. Baseline variables collected include date of assessment, gender, age at first clinical assessment, age at tic onset, tic severity measured using the Yale Global Tic Severity Scale-Revised (YGTSS-R), the presence of mental health comorbidities (attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder (ADHD), obsessive–compulsive disorder (OCD), generalised anxiety disorder and major depressive disorder), and medical and behavioural treatment. Medical treatments were categorised by drug class and included alpha agonists, antipsychotics, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitors and psychostimulants. All diagnoses were based on clinical assessment and fulfilment of DSM-5 diagnostic criteria. Follow-up assessments are performed after 6 and 12 months, and after the child reaches their 18th birthday. Follow-up assessment data collected included date of assessment, age, YGTSS-R score, and medical and behavioural treatment. For the present analysis, only participants with tic disorders (Tourette syndrome, persistent motor tic disorder, persistent vocal tic disorder and provisional tic disorder) were included.

The YGTSS-R quantifies tic severity by using five different subcategories: the number of different tics, the frequency of tics, the intensity of tics (how forceful or loud a tic is), the complexity of the tics and the interference that the tics cause. A greater frequency of tics correlates to a higher numerical score; the same is true for the other subcategories (greater intensity means a higher score, and so on). Specialists, parents and patients work together to evaluate and rate tic severity in the previous week. All values from the five subcategories and a measure of impairment are summed to generate a final global severity score; the higher the number, the worse the global severity. Reference McGuire, Piacentini, Storch, Murphy, Ricketts and Woods14

To determine if calendar month of the year impacts tic severity, we evaluated the mean YGTSS-R total tic severity score based on the calendar month the data were collected. All YGTSS-R scores recorded in the registry were used, regardless of if captured at baseline, 6 months, 12 months or 18 years of age.

Statistical analysis

Categorical variables were summarised with the count and percentage. Measured variables were summarised with the mean and standard deviation. Outcomes were aggregated by month with the mean, standard deviation and 95% confidence interval calculated. Multivariable linear regression models with random intercepts per patient were fit to assess the individual months adjusted for age, gender, ADHD, OCD, major depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder and tic treatment variables. Tic treatment was defined as use of behaviour therapy, alpha agonists or antipsychotics. An analysis of variance test comparing nested models with and without the month variables was used as an omnibus test to determine whether there are statistically significant differences between months.

The authors assert that all procedures contributing to this work comply with the ethical standards of the relevant national and institutional committees on human experimentation and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2013. All procedures involving human patients were approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board (approval number REB16-1116). Parents provided written informed consent and children provided assent to study participation and publication of the study results.

Results

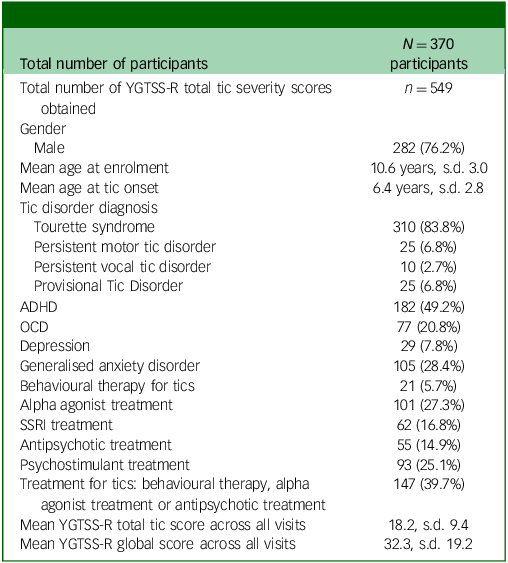

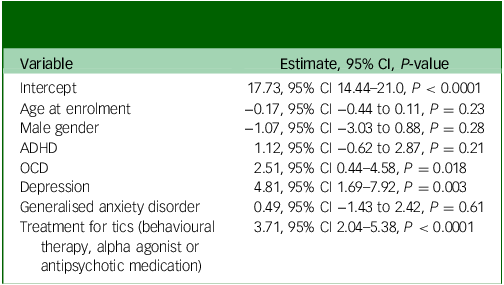

The study included 370 participants with tic disorders, with the majority diagnosed with Tourette syndrome (83.8%). Male participants predominated (76.2%), with a mean age at tic onset of 6.4 years and a mean age at enrolment of 10.6 years. The most diagnosed comorbid condition was ADHD in 49.2% of participants, and the most common medication class taken was alpha agonists (27.3%). Among the 370 participants, 549 assessments were performed over the course of the study: 352 at baseline, 96 at 6 months, 77 at 12 months and 24 after the 18th birthday. There was no difference in age, gender, diagnoses, comorbidity or tic severity on the YGTSS-R between those completing a single versus multiple assessments. See Table 1 for full description of study population demographics.

Table 1 Study population demographics

YGTSS-R, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale-Revised; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder; SSRI, selective serotonin reuptake inhibitor.

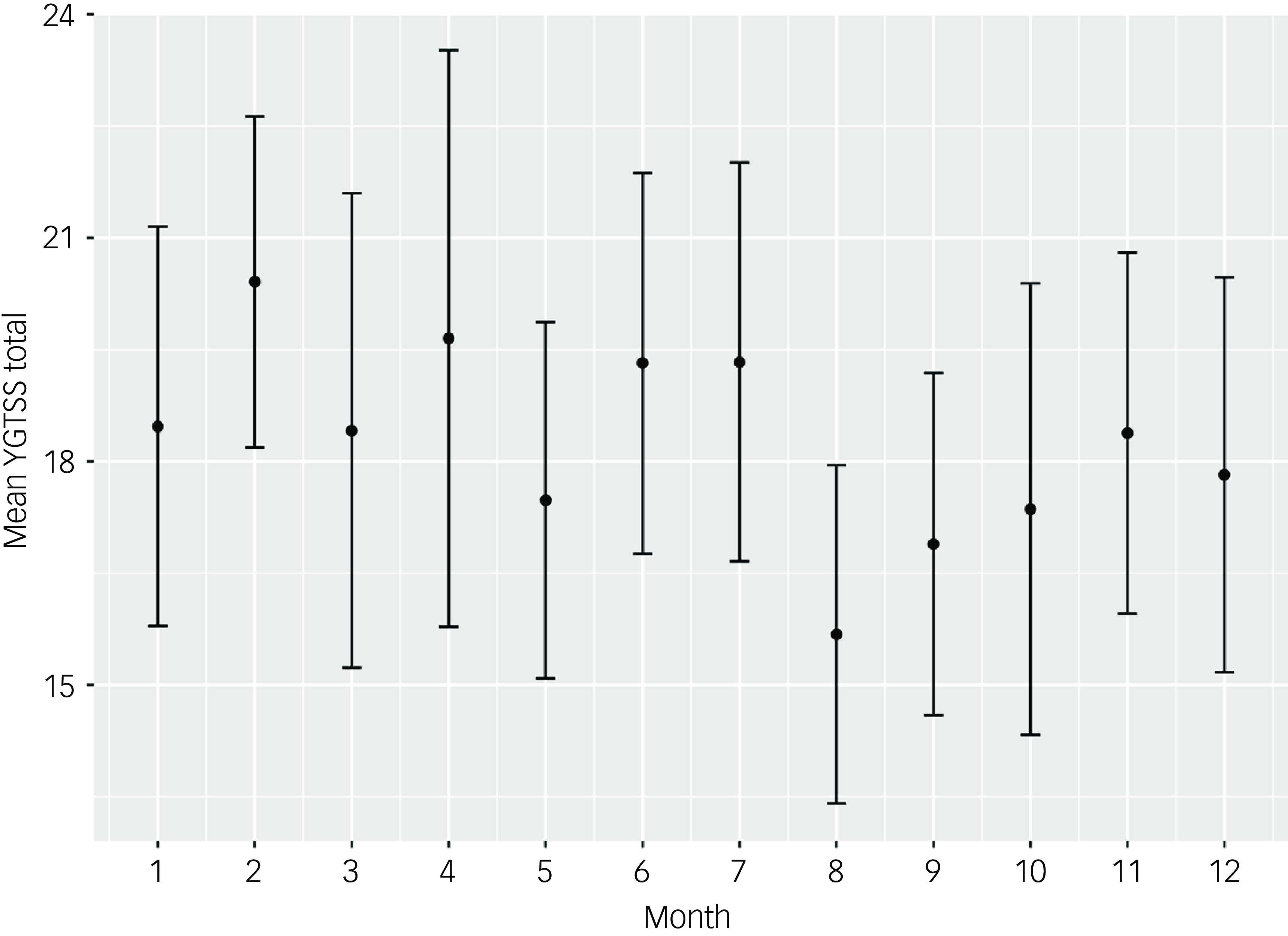

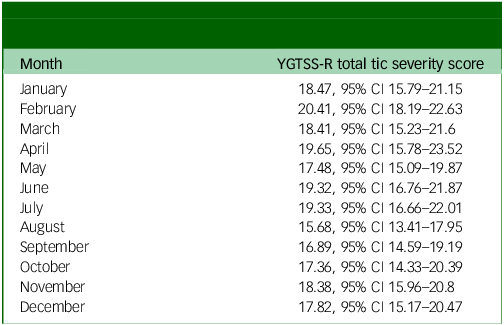

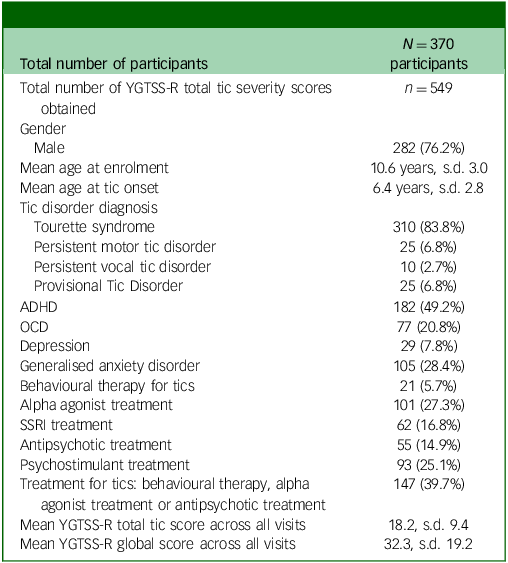

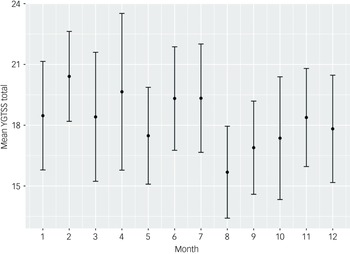

In the univariable analysis of tic severity measured using the YGTSS-R based on calendar month, August was the month with the lowest tic severity, with a mean YGTSS-R total tic severity score of 15.68 (95% CI 13.41–17.95). This was significantly lower than the month with the highest tic severity, February, with a mean score of 20.41 (95% CI 18.19–22.63). See Table 2 for full description of tic severity by month and depicted in Fig. 1.

Fig. 1 YGTSS-R total tic severity by month of the year (all visits, n = 549). YGTSS-R, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale-Revised.

Table 2 YGTSS-R total tic severity by month of the year (all visits, n = 549)

YGTSS-R, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale-Revised.

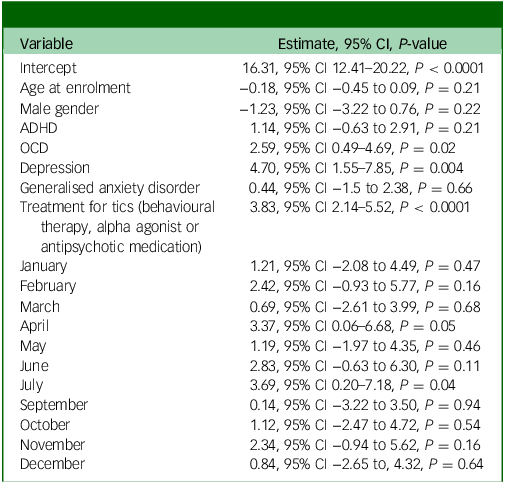

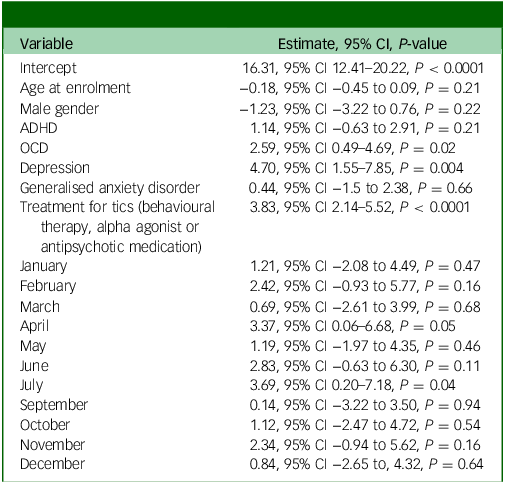

In multivariable models adjusted for age, gender, ADHD, OCD, major depressive disorder, generalised anxiety disorder and treatment for tics, the omnibus test for whether month contributes to a better fit were not significant (YGTSS-R total tic score P-value: 0.4951). This indicates that the month of the measurement was not a meaningful predictor of outcomes, after adjustment. For this analysis, all months were compared relative to August, which had the lowest tic severity score in the univariate analysis (see Table 3).

Table 3 YGTSS-R total tic score multivariable modelling – all visits

YGTSS-R, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale-Revised; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder.

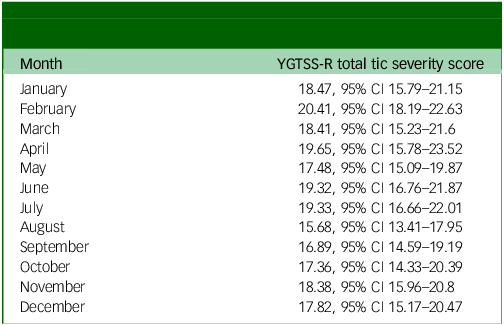

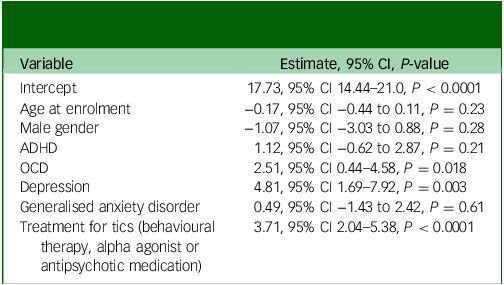

Coefficients for the adjusted variables without the month variables are reported in Table 4. The only significant predictors of increased tic severity on the YGTSS-R were treatment for tics (P < 0.0001), diagnosis of depression (P = 0.003) and diagnosis of OCD (P = 0.02).

Table 4 YGTSS-R total tic score multivariable modelling, months removed – all visits

YGTSS-R, Yale Global Tic Severity Scale-Revised; ADHD, attention-deficit hyperactivity disorder; OCD, obsessive–compulsive disorder.

Discussion

Our univariate analysis confirmed our clinical observation that tic severity is lower in the summer (August) compared with the middle of winter (February). However, when adjusting for age, gender and other variables that are known to impact tic severity, this association was not significant. The strongest predictors of tic severity identified in our population was the presence of comorbid internalising disorders (major depressive disorder, OCD) and the use of treatment for tics. Limitations of this study include our inability to adjust for other factors that are known to impact tic severity, including family history of tic disorders and the presence of known concurrent psychosocial stressors.

There is very limited data on the effect of calendar month on tic severity. Lamanna and colleagues performed a 15-month prospective observational study of 24 children and adults with tic-related OCD living in Milan, Italy. Reference Lamanna, Mazzoleni, Farina, Ferro, Galentino and Porta15 They assessed tics and OCD symptom severity at six time points, with local environmental data. Although data for individual calendar months were not provided, tics were more severe in spring and summer compared with winter and autumn, with a significant positive correlation between ambient temperature and YGTSS-R scores (r = 0.525). Although this study contained considerably fewer observations than our present work, their results are discordant with our finding that tic severity was lowest in the summer month of August. August is one of the hottest months in Calgary, with an average daily temperature of 17 °C, but this is still considerably cooler than the average daily temperature of 25°C in Milan. Another explanation for our different results could be patient population: individuals with tic-related OCD may have different environmental sensitivities compared with those with tic disorders without comorbid OCD.

In a previous study by the same group from Milian, Vitale and colleagues investigated whether tics and obsessive–compulsive symptoms exhibited a circannual rhythm and whether chronotype influenced symptom severity throughout the year. Reference Vitale, Briguglio, Galentino, Dell’Osso, Malgaroli and Banfi16 Thirty-seven participants, aged 7–39 years, with tic-related OCD were evaluated four times, once in each of the four seasons: Winter, Spring, Summer and Autumn. Participants were identified as having morning, evening or neither/intermediate chronotypes, and had their symptom severity measured with the YGTSS-R and Yale–Brown Obsessive Compulsive Symptom scale (Y-BOCS) at all four visits. A minority of participants, 16.2%, exhibited a circannual rhythm in tic symptoms and obsessive–compulsive symptoms. Tic severity did not vary significantly throughout the year, but obsessive–compulsive symptoms did, with severity being lower in Summer compared with Winter and Autumn. Similarly, chronotype did not significantly impact YGTSS-R scores, but evening types had significantly higher Y-BOCS scores compared with morning types, especially in the summer.

Further research is needed to contextualise our study; specifically, longitudinal studies in various climates could help us identify the impact of weather phenomena such as temperature, daylight, and humidity. Research performed in locations with moderate climates could provide insight into whether tics are triggered by climate extremes, such as winters below 0 °C in Calgary and summers reaching above 25 °C in Milan. More work is needed to understand the impact of and interplay between changes in physical activity, socialisation and psychological stress during children’s summer vacation compared with the school year, and how these factors may impact tic severity. Previous studies have shown that an acute bout of aerobic exercise can decrease tic severity, Reference Nixon, Glazebrook, Hollis and Jackson17 and that there is a significant negative correlation between the amount of physical activity over a 1-week period and tic severity on the YGTSS-R. Reference Pringsheim, Nosratmirshekarlou, Doja and Martino18 Children report that holidays, playing sports and leisure activities are more often associated with a decrease than an increase in tics, although 50% report no influence of these factors on tic severity. Reference Caurín, Serrano, Fernández-Alvarez, Campistol and Pérez-Dueñas19 Finally, morning light therapy in adults with tics was associated with small but significant decreases in tic severity and impairment. Reference Ricketts, Burgess, Montalbano, Coles, McGuire and Thamrin20 These factors could be potentially related to the decrease in tics during the month of August in children living in Calgary, where the vacation from school and long days allow more time to participate in sport and leisure activities and greater exposure to daylight.

The effects of co-occurring internalising and externalising disorders on tic severity in children and adolescents

Previous studies have shown that internalising disorders are strongly associated with increased tic severity. Lebowitz et al Reference Lebowitz, Motlagh, Katsovich, King, Lombroso and Grantz8 studied the impact of OCD on tic severity by comparing children with tic disorders and OCD to children with only tic disorders. Within the sample of 158 children, 53.8% met the diagnostic criteria for OCD; these children had significantly higher tic severity than children with tic disorders only. Having an OCD diagnosis was also strongly associated with higher levels of psychosocial stress, depression and anxiety. Marwitz and Pringsheim Reference Marwitz and Pringsheim21 found that having a diagnosis of anxiety or depression is strongly associated with increased tic severity. In their sample of 126 children with tic disorders, there were significant positive correlations between anxiety and depressive symptoms and tic severity. Depressive symptoms had a stronger correlation to tic severity than anxiety. Depressive symptoms have also been shown to influence quality of life in youth with tic disorders. A study of 50 youth with tics by Eddy et al found that depressive symptoms on the Child Depression Inventory had the highest correlation with quality of life on a youth-rated instrument. Reference Eddy, Cavanna, Gulisano, Agodi, Barchitta and Calì22

In contrast, although the presence of externalising disorders may negatively impact children with tic disorders, they do not show a strong association with increased tic severity. In a study of 114 children with tic disorders, Pringsheim found a non-significant increase in tic severity in children with ADHD, but that children with ADHD are significantly more likely to be treated for their tics within the first 2 years of tic onset. Reference Pringsheim9 Similarly, in the above-mentioned study, Lebowitz et al Reference Lebowitz, Motlagh, Katsovich, King, Lombroso and Grantz8 found no significant increase in tic severity in children with co-occurring ADHD, but observed higher psychosocial stress in children with ADHD.

The effects of stress on tic severity in children and adolescents

Although stressful events significantly increase tic severity, the long-term impact of stress on tic severity is inconclusive. Tan et al Reference Tan, Chiu, Zeng, Huang, Tzang and Chen23 performed a longitudinal study to analyse the relationship between psychological stress and tic severity. The researchers found that family-related stress, personal relationship stress and school-related stress were all individually associated with increased tic severity. A sample of 375 children with tic disorders had their tic severity measured with the YGTSS-R and reported any relevant stressful events occurring in the preceding week. Compared with the YGTSS-R global severity scores of children who had not experienced stressful events, children scored 4.33 points higher with school-related stress, 4.81 points higher with personal relationship stress and 4.92 points higher with family-related stress. The absence of school-related stress during the summer holiday months is a possible explanation for the lower mean tic severity scores in August in our study.

Barber et al Reference Barber, Ding, Espil, Woods, Specht and Bennett13 examined the effects of stress on tic severity from adolescence to early adulthood in a retrospective study of 74 individuals with tic disorders. Barber et al found stress was the most commonly reported trigger for increased tic severity, with 63.5% of participants agreeing that stress worsened their tics throughout adolescence. YGTSS-R scores during the periods of reported stress were not recorded. Although there is compelling evidence to suggest that stress increases tic severity, the overall significance of stress remains to be determined.

Effects of situation on tic severity in children and adolescents

Situations preceding a tic can temporarily affect severity. Himle et al Reference Himle, Capriotti, Hayes, Ramanujam, Scahill and Sukhodolsky12 surveyed 51 children to understand which antecedent variables (events occurring before a tic) increase tic severity. All participants agreed that at least two antecedent variables increased tic severity. The most frequently reported antecedent variables increasing tic severity were watching television or playing video games (92.2%), being at home (88.2%), doing homework (80.45%), being in class (78.4%) and being in a public place/social environment (78.4%). In the same study, Himle et al Reference Himle, Capriotti, Hayes, Ramanujam, Scahill and Sukhodolsky12 also examined how consequential variables (outcomes the child predicts to occur after a tic) affect tic severity. Himle et al found that almost all 51 children agreed that at least one consequence variable increased tic severity. The most commonly reported consequence variables increasing tic severity were being told to stop tics (72.5%) and receiving comfort for tics (58.8%). After isolating for co-occurring disorders, Himle et al discovered that children with co-occurring internalising disorders reported more triggers for their tics compared with children without co-occurring disorders. Children with internalising disorders had their tic severity increased by a wider variety of events.

In conclusion, although our univariate analysis of tic severity by calendar month supported significantly lower tic severity in August compared with February, this association was no longer statistically significant when controlling for other variables known to impact tic severity. Comorbid major depressive disorder had the largest association with tic severity scores in our sample. Further research is required to better understand the nature and direction of this relationship. Clinicians may need to more actively promote treatment while tic symptoms are mild to prevent the development of depressive symptoms, or conversely, treat depression to help decrease tic severity. This study provides additional data on the possible effect of contextual factors on tic severity.

Data availability

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, T.P. The data are not publicly available due to privacy or ethical restrictions.

Author contributions

I.D. was involved in carrying out the study, analysing data and writing the article. B.C.L. was involved in designing the study, analysing the data and revising the article. C.D. and D.M. were involved in carrying out the study and revising the article. T.P. was involved in formulating the research question, designing the study, carrying it out, analysing the data and writing the article.

Funding

This work was supported by the University of Calgary Owerko Centre for Neurodevelopment and Child Mental Health and the Tourette OCD Alberta Network.

Declaration of interest

D.M. has received consultancies from Roche; is on the advisory board of Merz Pharmaceuticals; has received honoraria from the Dystonia Medical Research Foundation Canada, Movement Disorders Society and Canadian Movement Disorders Society; and has received royalties from Springer-Verlag and Oxford University Press. They have also received grants from the Weston Family Foundation, New Frontiers in Research (Exploration), Government of Canada, Neuroscience, Rehabilitation and Vision Strategic Clinical Network of the Alberta Health Services, Owerko Foundation, Dystonia Medical Research Foundation (DMRF) USA, DMRF Canada, National Spasmodic Torticollis Association (NSTA) Sacramento Chapter in Memory of Howard Thiel, Parkinson Canada, The Canadian Institutes of Health Research and Michael P. Smith Family. All other authors have no competing interests to declare.

Ethical standards

All procedures involving human patients were approved by the University of Calgary Conjoint Health Research Ethics Board, approval number REB16-1116. Parents provided written informed consent and children provided assent to study participation and publication of the study results.

eLetters

No eLetters have been published for this article.