In a time of rapid global change, understanding connections between the places people live and the relationships they form with local ecosystems through time is important for enhancing conservation biology and human and environmental welfare. Landscapes help shape identity, subsistence and ecology, settlement and land use, and cultural and ritual systems. Archaeologists have long recognized the significance of persistent places—locations that have long-term occupations and that have played a special role in human settlement systems and cultural practices (Gamble Reference Gamble2017; Moore and Thompson Reference Moore and Thompson2012; Schlanger Reference Schlanger, Rossignol and Wandsnider1992; Thompson Reference Thompson, Thomas and Sangar2010). Building on earlier work on cultural keystone species (Garibaldi and Turner Reference Garibaldi and Turner2004), Cuerrier and colleagues (Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015; see Lepofsky et al. Reference Lepofsky, Armstrong, Greening, Jackley, Carpenter, Guernsey, Matthews and Turner2017:449) presented the term “cultural keystone places” (CKPs), which is defined as follows:

A given site or location with high cultural salience for one or more groups of people and which plays, or has played in the past, an exceptional role in a people's cultural identity, as reflected in their day to day living, food production and other resource based activities, land and resource management, language, stories, history, and social and ceremonial practices [Cuerrier et al. Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015:431].

CKPs and persistent places are related but distinct frameworks that emphasize the deep time links among place, culture, and ecology. Specifically, Cuerrier and colleagues (Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015:432) established 10 indicators of a CKP (Table 1). These indicators emphasize the important relationships and knowledge that Indigenous peoples have with the landscapes they inhabit. CKPs also emphasize that people actively shape and are shaped by the world around them. CKP designations are especially important because they highlight the connections between biological and cultural diversity that can aid in environmental conservation and cultural preservation (Cuerrier et al. Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015; Lepofsky et al. Reference Lepofsky, Armstrong, Greening, Jackley, Carpenter, Guernsey, Matthews and Turner2017).

Table 1. Ten Indicators of a Cultural Keystone Place Following Cuerrier and Colleagues (Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015:432) and the Correlates Identified at Kumqaq’.

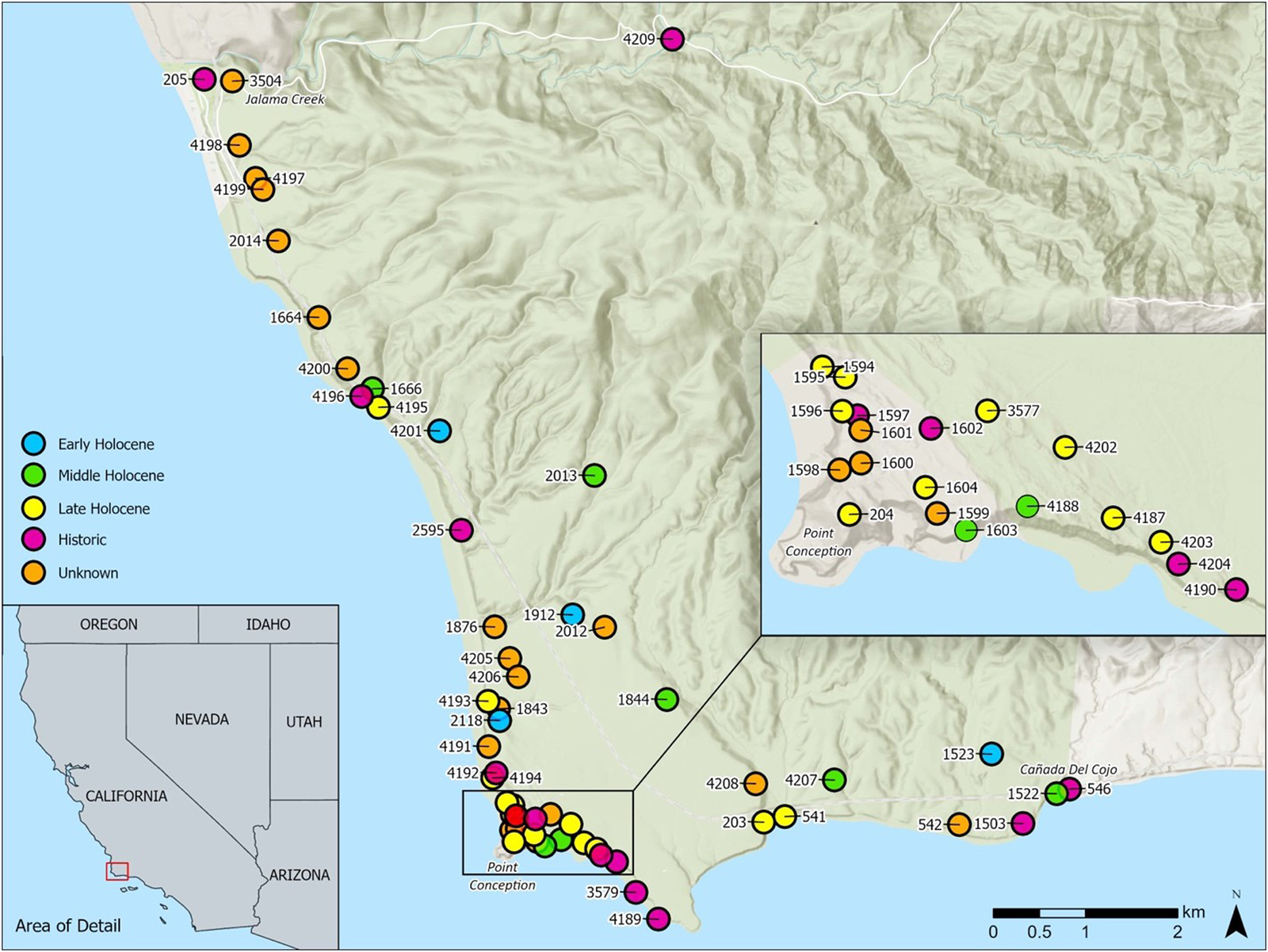

Although CKPs have been described for several locations in Canada, particularly the Pacific Northwest (Cuerrier et al. Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015; Lepofsky et al. Reference Lepofsky, Armstrong, Greening, Jackley, Carpenter, Guernsey, Matthews and Turner2017), the framework has received limited application in other areas in part because it is relatively new. Here, we draw on an archaeological survey, ethnohistoric data, and contemporary Chumash perspectives to document long-term patterns of coastal land use and settlement spanning at least 9,000 years near Kumqaq’, Point Conception, California (Figure 1).Footnote 1 Point Conception is a biogeographical boundary point for many coastal and marine species, it harbors unique biodiversity, and it has long been recognized as an area of conservation priority (Dawson Reference Dawson2001; Elsberry et al. Reference Elsberry, Fales and Bracken2018). Until recently, the land surrounding Kumqaq’ was a private ranch for over a century, and the point itself was owned by the US government. Moreover, few studies had been published about the archaeology of this coastline compared to areas to the north and east.

Figure 1. Coastal archaeological sites in Point Conception and their age based on radiocarbon dates or artifact associations. Some dates have multiple components. See Supplemental Table 1 or Figure 4 for other site components. All site numbers should be preceded by CA-SBA-. Site numbers correspond to site descriptions in Table 2 and radiocarbon dates in Supplemental Table 1. Area in green corresponds to the JLDP boundaries. Dots are deliberately large to obscure precise site locations and should be considered as approximate locations. (Drafted by Lain Graham.)

Kumqaq’ is of great importance to the Chumash—particularly the Shmuwich and Samala Chumash—and it is known to some as the Western Gate, or where souls bathe prior to departing for the afterlife (Blackburn Reference Blackburn1975; Haley and Wilcoxon Reference Haley and Wilcoxon1997, Reference Haley and Wilcoxon1999). Flanking the point at the mouths of two large drainages are two historic period Chumash villages: Shilimaqshtush and Shisholop. These villages and a third closely related satellite settlement of Shisholop called ’Upop were described by early Euro-American explorers and in mission records, yielding a variety of ethnohistorical information on the Chumash who lived near Kumqaq’ (Gamble Reference Gamble2008; Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Blackburn, Curletti and Timbrook1977; Johnson Reference Johnson1988; King and Craig Reference King and Craig1978). In the 1970s, members of Chumash bands, activists, and other supporters occupied an area near Point Conception to protest a proposed liquefied natural gas plant, which was ultimately canceled. While working on a Traditional Cultural Property nomination (a formal National Register designation administered by the US National Park Service), Haley and Wilcoxon (Reference Haley and Wilcoxon1997, Reference Haley and Wilcoxon1999) revisited the ethnohistory of Kumqaq’ and argued that anthropologists had created much of the knowledge around the significance of the area and that the importance of Point Conception among some bands of the Chumash might not have been widespread until recent decades. The Traditional Cultural Property was not formalized, but the research and perspectives from this work generated considerable debate about the making of Chumash identity and traditional customs (see Erlandson et al. Reference Erlandson, King, Robles, Ruyle, Wilson, Winthrop, Wood, Haley and Wilcoxon1998; Haley and Wilcoxon Reference Haley and Wilcoxon1997), providing a foundation for our work and a means to explore the significance of Kumqaq’ over two decades later.

Largely missing from this discussion of the cultural significance of Kumqaq’ is an overview and assessment of the archaeology of the region. Several compliance and other archaeology projects have been conducted in and around Point Conception (Erlandson and Vellanoweth Reference Erlandson and Vellanoweth2002; Erlandson et al. Reference Erlandson, Carrico, Dugger, Santoro, Toren, Cooley and Hazeltine1993; Glassow Reference Glassow1978; Lathrap and Hoover Reference Lathrap and Hoover1975; Nocerino et al. Reference Nocerino, Lebow, Munns, Harro and McKim2016; Ruth Reference Ruth1936; Wilcoxon Reference Wilcoxon1990). However, the area between Jalama Creek and Cañada del Cojo generally appears blank on reviews of Santa Barbara Channel archaeology site maps (see Glassow et al. Reference Glassow, Gamble, Perry, Russell, Jones and Klar2007:Figure 1). Additionally, studies of fishing and shellfishing that explore the importance of the Point Conception biogeographic divide on human subsistence present no data from within this area (Glassow and Wilcoxon Reference Glassow and Wilcoxon1988; Gobalet Reference Gobalet2000). To help fill this void, we present the results of an archaeological survey and radiocarbon dating project focused on a 13 km stretch of coastline surrounding Kumqaq’, within an area now known as the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve (JLDP), owned and managed by the Nature Conservancy (TNC). Conducted in collaboration with TNC and the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians (SYBCI), our research is guided by two overarching questions:

(1) Where and when did people settle along the coast on either side of Kumqaq’?

(2) How do archaeological data on past settlement and land use potentially articulate with ethnohistoric and contemporary Chumash perspectives and the making of a CKP?

We place our work in the context of other collaborative approaches in archaeology and environmental conservation, demonstrating the value of integrating biological and cultural perspectives in an era of rapid environmental and climatic change (Douglass et al. Reference Douglass, Walz, Morales, Marcus, Myers and Pollini2019; Gonzalez et al. Reference Gonzalez, Kretzler and Edwards2018; Lepofsky et al. Reference Lepofsky, Armstrong, Greening, Jackley, Carpenter, Guernsey, Matthews and Turner2017; Lightfoot, Cuthrell, et al. Reference Lightfoot, Cuthrell, Striplen and Hylkema2013).

Context and Background

Point Conception and the JLDP are located on the southern California coast in Santa Barbara County. The JLDP is roughly 24,329 acres, with approximately 13 km of coastline and a mountainous interior. It is bounded by Vandenberg Air Force Base (VAFB) to the north and the Hollister Ranch, an area of private estates, to the east. A small (29.6 acres) parcel of land immediately surrounding Point Conception and its lighthouse is managed by VAFB. We use the term Kumqaq’ to refer to Point Conception and the 29.6 acres of land surrounding it. We use the terms Kumqaq’ Region or surrounding area to reference the JLDP, which is the larger coastline and interior associated with Kumqaq’ and the location of the major Chumash villages that were closest to the Point (Figure 1).

The California coastline at Point Conception makes an abrupt shift to the east-west trending Transverse Range. The coastline north of Point Conception is dominated by surf-swept, sandy beaches flanked by kelp forest and rocky intertidal habitat. In contrast, areas to the east of it are considerably more sheltered, with the Northern Channel Islands oriented as a chain of four islands just offshore. This area marks a mixing of colder northern and warmer southern ocean currents and approximates a biogeographic dividing point for many coastal and marine organisms (Dawson Reference Dawson2001; Elsberry et al. Reference Elsberry, Fales and Bracken2018). Terrestrial plant communities in and around Point Conception also harbor unique biodiversity. This location is a biodiversity hotspot, with a high number of endemic species and biogeographic crossroads that serves as a “mixing” zone—or ecotone—between cooler, more maritime climate-adapted terrestrial and freshwater species of the Central Coast and species adapted to the warmer and drier South Coast and Northern Baja California region (Butterfield et al. Reference Butterfield, Reynolds, Gleason, Merrifield, Cohen, Heady and Cameron2019; Gatewood et al. Reference Gatewood, Davis, Gallo, Main, McIntyre, Olsen, Parker, Pearce, Windhager and Work2017).

Kumqaq’ and the larger Santa Barbara Channel region have been inhabited by the Chumash and their ancestors for at least 13,000 years (Erlandson et al. Reference Erlandson, Rick, Braje, Casperson, Culleton, Fulfrost and Garcia2011; Lebow et al. Reference Lebow, Harro, McKim, Hodges, Munns, Enright and Haslouer2015). Chumash refers to a language family with at least three branches (Northern, Central, and Island) and six different languages (Obispeño, Purismeño, Samala/Ineseño, Shmuwich/Barbareño, Isleño/Cruzeño, and Mitsqanaqan/Ventureño), corresponding to different Chumash tribal groups (Golla Reference Golla, Jones and Klar2007:80). The JLDP is in the southern part of Purismeño territory (Gamble Reference Gamble2008; Glassow Reference Glassow1978:6, Reference Glassow1996; Johnson Reference Johnson1988). Chumash villages north of Point Conception generally had smaller populations than those to the east along the Santa Barbara Channel (Glassow and Wilcoxon Reference Glassow and Wilcoxon1988; Johnson Reference Johnson1988). The Kumqaq’ area is home to three primary Chumash villages and one satellite village: Shilimaqshtush to the north of Point Conception, Shisholop and the satellite settlement of ’Upop to the southeast of the point, and Xalam in the interior (Gamble Reference Gamble2008; Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Blackburn, Curletti and Timbrook1977; Johnson Reference Johnson1988; King Reference King1975; Lathrap and Hoover Reference Lathrap and Hoover1975; Wilcoxon Reference Wilcoxon1994).

Ethnohistoric accounts provide insight into the Chumash people who lived at these villages, but especially Shisholop and Shilimaqshtush. Mission period baptism and census records provide estimates of the number of people living at these villages and direct genealogical ties to contemporary Chumash tribal members, particularly the SYBCI (Johnson Reference Johnson1989a). McLendon and Johnson (Reference McLendon and Johnson1999) noted that there were 106 baptisms associated with Shilimaqshtush and 197 with Shisholop, with population estimates for both villages between 150 and 250 individuals (Brown Reference Brown1967; Gamble Reference Gamble2008:74; Johnson Reference Johnson1988:113, 115). Shisholop is described as a capital village with at least one chief (Johnson Reference Johnson1988:120) and Crespí, a Franciscan missionary, noted 5–6 canoes and 38 grass houses at the site in AD 1770 (Gamble Reference Gamble2008:75). In addition to these villages, there was a mission period vineyard, olive and walnut orchards, and possibly a winery along Jalama Creek that were aligned with Mission La Purísima, which was located several kilometers to the north (Harrison Reference Harrison1960; Ruhge Reference Ruhge2009).

As with the biogeographic divisions, Point Conception marks the approximate location of a number of important cultural differences. It was a likely dividing point for the use of the tomol (redwood plank canoe)—a technology linked to maritime trade, offshore fishing, and the rise of sociopolitical complexity in the Santa Barbara Channel region. People to the north of the Point used tule reed canoes instead of plank boats, but groups to the east along the Santa Barbara Channel and Northern Channel Islands relied heavily on plank boats (Brown Reference Brown1967; Gamble Reference Gamble2002, Reference Gamble2008; Landberg Reference Landberg1965). Geographic variation in watercraft types needs further research, but it is supported by differences in archaeological finfish remains from sites to the north and east of Point Conception (Gobalet Reference Gobalet2000). The analysis of shellfish remains also demonstrates significant differences in the nearshore habitats that were utilized on either side of the point, although no data from the JLDP were available for either the finfish or shellfish studies (Glassow and Wilcoxon Reference Glassow and Wilcoxon1988). The offshore waters near Point Conception have produced a number of artifacts identified by local divers. These include net weights that may be from discarded fishing gear along with sandstone bowls and a charmstone that may be from ritual discard, suggesting that the waters off Point Conception are also culturally significant (Hudson Reference Hudson1976, Reference Hudson1979).

Methods and Approach

An important step toward understanding the Kumqaq’ region CKP is documenting where and when people lived at various localities and how long-term cultural landscapes were created. In 2019 and early 2020, we conducted a systematic pedestrian survey of the entire 13 km stretch of coastline of the JLDP from Jalama Creek in the north to Cañada del Cojo Creek and to the interior for 0.3–0.75 km, depending on terrain (Rick et al. Reference Rick, Braje, Easterday, Graham, Hofman, Holguin and Reeder-Myers2021). Our research was conducted in consultation with the SYBCI Elder's Council, Chumash archaeological consultants, and TNC's JLDP staff.

Survey transects consisted of people spaced out with gaps of 8–10 m between each individual, comparable to other surveys in the region (Perry et al. Reference Perry, Glassow, Neal, Joslin and Minas2019:584). Archaeological sites were identified through the presence of faunal remains, artifacts, dark soil, and architectural features on the surface with no subsurface testing. Dense vegetation, recent dune sand or other sediment, road construction, and other obstacles obstructed the identification of archaeological sites or site boundaries in some locations. In these areas, we looked for rodent tailings and other ground disturbances or exposures to help identify site boundaries. Nonetheless, vegetation cover, dune sand, and other sediments hindered our ability to define site boundaries precisely and may have precluded relocation of a few previously recorded or unidentified sites (Rick et al. Reference Rick, Braje, Easterday, Graham, Hofman, Holguin and Reeder-Myers2021). Given ongoing erosion and the dense vegetation (iceplant) and recent sand, we anticipate that additional undocumented sites within our survey area are buried or obscured and that additional sites will be identified in the coming years.

Graham built a platform for recording site information in Esri's Collector and Survey123 mobile platforms. This allowed us to record information digitally in the field on a tablet enabled by external Bluetooth GPS, with accuracy of around 1 m. The information recorded in the field was then output into the California Department of Parks and Recreation (DPR) site record format. This required some trial and error to establish proper protocols but proved an important means for digital collection of data that should be instrumental for future surveys and monitoring at JLDP and beyond. Archaeologists are increasingly using Esri's Collector, Survey123, and other GIS mobile applications to record information on handheld devices in the field (Lindsay and Kong Reference Lindsay and Kong2020). To our knowledge, this is the first project in California to integrate this information digitally into state DPR forms.

In discussion with Chumash consultants, we collected marine shells from eroding deposits or from small probes at sites that had not been previously excavated to obtain in situ samples for radiocarbon dating. Although a few sites contain beads, projectile points, or other objects that can be used to determine approximate ages of a given site, radiocarbon dates provide a means to understand the general chronology of a site and associated activities of people. For the few sites in the area that have been excavated, we also dated materials housed in the repository at the University of California Santa Barbara (UCSB) or synthesized previously reported radiocarbon dates.

All radiocarbon samples were from single California mussel (Mytilus californianus) or black abalone (Haliotis cracherodii) shells analyzed using accelerator mass spectrometry (AMS) at the NOSAMS radiocarbon facility at Woods Hole Oceanographic Institute. Marine samples were calibrated in OxCal 4.4 using the Marine20 calibration curve and applying a local Santa Barbara Channel reservoir correction of 128 ± 104 (Bronk Ramsey Reference Bronk Ramsey2009; Heaton et al. Reference Heaton, Köhler, Butzin, Bard, Reimer, Austin and Ramsey2020). The reservoir correction was obtained from the 14Chrono database and is based on the Marine20 curve applied to three known-age samples from Ingram and Southon (Reference Ingram and Southon1996) that were used to calculate the updated ΔR value for a previous value that was long used in the Santa Barbara Channel region (225 ± 35; Erlandson Reference Erlandson, Erlandson and Glassow1997; Glassow Reference Glassow, Erlandson and Glassow1997). When necessary (Supplemental Table 1), we used a sequence to produce modeled dates/posteriors that take into account a likely end of occupation at AD 1835 ± 5, roughly corresponding to the end of the mission period. We used OxCal to estimate the boundaries of phases and their durations (Supplemental Table 2). For sites with more than one radiocarbon date, we estimated the span of occupancy, including boundary start and end dates. We evaluated support for the presence of two phases/a gap in occupancy based on our radiocarbon dating and grouped 13 dates into the Early Holocene and 37 into the Middle and Late Holocene (including the historic period; Supplemental Table 3).

We used the R package rcarbon (Crema and Bevan Reference Crema and Bevan2020; Crema et al. Reference Crema, Bevan and Shennan2017) to generate a summed probability distribution (SPD) of radiocarbon dates. Although our data are limited by a small number of dates—or even a single date—from many of the sites, the SPD helps visualize general patterns and identify gaps and priorities for future sampling to refine the phase patterns identified in OxCal. We used the function spd() to aggregate calibrated radiocarbon dates using Marine20 and our marine reservoir correction, with a cutoff window of 115 cal BP to exclude the post–mission period. Given the coarseness of our sampling, we display a rolling average of 500 and 1,000 years for smoothing to explore general patterns and avoid overinterpreting the data.

Coastal Settlement through Time

Our survey draws on 57 archaeological sites that document the long-term Chumash landscapes of the Kumqaq’ region (Table 2). Although our focus is on sites along the immediate coastline, we also discuss a few sites that are further to the interior. Archaeological sites attest to diverse cultural land use across the coastline, including small and large sites (lithic scatters, shell middens, and villages) exposed in sea cliffs, on high coastal hilltops, and in dunes/blowouts (Figures 2 and 3). Fifty radiocarbon dates from 33 sites establish a chronology from approximately 9000 cal BP to the early nineteenth century (Supplemental Table 1; Figures 4 and 5).

Table 2. Archaeological Sites Discussed in the Article, Including Site Type and Chronology.

a 2σ age ranges are presented with detailed radiocarbon data provided in Supplemental Table 1. Some sites list general chronological information based on artifact associations. H = Historic, LH = Late Holocene, TP = terminal Pleistocene, and EH = Early Holocene. “Historics” refers to historical artifact and debris scatters that postdate the mission period. Future research is needed at SBA-1597 and -4190 to determine if the date on the shellfish is actually associated with the shell midden.

b Historic artifacts likely associated with later Euro-American occupation.

Figure 2. Early and Middle Holocene sites and current landscapes: (left) an approximately 8,600-year-old hilltop site at CA-SBA-4201 looking out toward Point Conception in the distance; (top right) a 6,800-year-old hilltop site at CA-SBA-4207, which contained California mussel and Washington clam; (bottom right) under the iceplant in the foreground is an approximately 8,300-year-old site at CA-SBA-2118, with interior mountains visible in the background; (bottom left inset) a mano/groundstone found on the surface near CA-SBA-4207. (Photos by Torben Rick. Figure prepared by Todd Braje.)

Figure 3. Late Holocene and historical sites and current landscapes on the JLDP coastline: (left) a dense midden exposure dated from 1340 to 280 cal BP at CA-SBA-203/541, with midden present in the entire unvegetated exposure; (top right) a lithic scatter and early twentieth-century historical debris scatter is present in the patches of bare sand overlooking Point Conception and lighthouse just visible in the center left of the photo; (bottom right) a dense midden and village site at CA-SBA-203 dated to 1690–1090 cal BP and overlooking a sandy beach and the mountains in the distance on the eastern end of the JLDP; (bottom left inset) a close-up of a dense midden exposure (~40 cm thick) at CA-SBA-4194 dated to 900–220 cal BP. (Photos by Torben Rick. Figure prepared by Todd Braje.)

Figure 4. Archaeological site locations by time period based on radiocarbon dates and artifact associations (four maps in upper left). Distribution of radiocarbon-dated components through time (bottom and right panel; see also Supplemental Figure 1). All site numbers should be preceded by CA-SBA-. Site numbers correspond with site descriptions in Table 1 and radiocarbon dates in Supplemental Table 1. Area in green corresponds to the JLDP boundaries. Dots are deliberately large to obscure precise site locations and should be considered as approximate locations. Date distributions produced using R package rcarbon. See Supplemental Figure 1 for an alternative view of date distribution through time with sites labeled; see Supplemental Table 2 for the data used to create the date distribution. (Maps drafted by Lain Graham. Radiocarbon distribution by Alexis Mychajliw.)

Figure 5. Summed probability model of radiocarbon dates from the JLDP produced using the R package rcarbon. The solid black line is a 1,000-year running average and the dotted line is a 500-year running average. (Prepared by Alexis Mychajliw.)

Three sites on the JLDP produced radiocarbon dates in excess of 8000 cal BP. CA-SBA-1523 and CA-SBA-4201 are both hilltop sites overlooking the ocean, and CA-SBA-2118 is located at the mouth of a small canyon (Table 2; Supplemental Table 1; Supplemental Figure 1; Figure 4). All three contain mostly California mussel shell, with a few chert flakes and trace amounts of barnacle. Erlandson (Reference Erlandson1994; Erlandson et al. Reference Erlandson, Carrico, Dugger, Santoro, Toren, Cooley and Hazeltine1993) reported a chipped stone eccentric crescent obtained during excavations at CA-SBA-1912. Although previously obtained radiocarbon dates from the site were Late Holocene in age—likely from bird activity or a later cultural component—eccentric crescents date to between 12,000 and 7500 cal BP in coastal California, indicating an Early Holocene occupation for this site (Erlandson Reference Erlandson1994; Erlandson et al. Reference Erlandson, Rick, Braje, Casperson, Culleton, Fulfrost and Garcia2011).

Following a small gap in dated components between 8050 and 7890 cal BP, seven sites contain components dated to the Middle Holocene (8000–4000 cal BP; Supplemental Table 1; Figure 4). This includes shell midden sites such as CA-SBA-1666 (Erlandson and Vellanoweth Reference Erlandson and Vellanoweth2002); CA-SBA-1844, located on a canyon rim; CA-SBA-2013 and CA-SBA-4207, located on hilltops; and CA-SBA-4188, located in a dune field. The Middle Holocene occupation contains the largest gap in the trans-Holocene sequence between 6050 and 4520 cal BP. This roughly 1,500-year gap is around the time of the Altithermal and apparent drying conditions (Erlandson Reference Erlandson, Erlandson and Glassow1997; Glassow Reference Glassow, Erlandson and Glassow1997; Rick et al. Reference Rick, Ontiveros, Jerardino, Mariotti, Méndez and Williams2020), but future dating and excavation at JLDP could help fill this chronological gap. Excavated data from CA-SBA-1666 (Erlandson and Vellanoweth Reference Erlandson and Vellanoweth2002), CA-SBA-1522 (Erlandson et al. Reference Erlandson, Carrico, Dugger, Santoro, Toren, Cooley and Hazeltine1993), and surface observations at the other sites demonstrate that, like the Early Holocene sites, most are dominated by rocky intertidal California mussels. Two sites contain estuarine shellfish (CA-SBA-1844 and CA-SBA-4207), suggesting that, similar to other areas of the western Santa Barbara coast, people took advantage of newly formed estuaries following postglacial sea-level rise (see Erlandson Reference Erlandson1994, Reference Erlandson, Erlandson and Glassow1997).

Like most other areas of the Santa Barbara coast and northern Channel Islands, the number of archaeological sites dramatically increases during the Late Holocene (4000 cal BP–present; Erlandson and Rick Reference Erlandson, Rick, Erlandson and Jones2002; Glassow Reference Glassow, Erlandson and Jones2002). Fourteen sites contain components dated between 3900 and 400 cal BP (Table 2; Figure 4). A few sites have age ranges that extend from the Late Holocene into the historic period and vice versa. We have grouped these sites in the figures depending on where the majority of the age range falls. Late Holocene sites are found throughout the JLDP in sand dunes, sea cliff exposures, and along creek banks, but no Late Holocene sites have yet to be identified on hilltops. However, we caution that the vast majority of the interior of the JLDP has not been surveyed. There are a few small gaps in the Late Holocene radiocarbon sequence (e.g., 2940–2790 and 2140–2040 cal BP), but we suspect that many of these may result from the lack of additional sampling.

Nine sites have radiocarbon dates in the protohistoric and historic periods between about 400 and 110 cal BP (Table 2). Four other sites produced historical artifacts (e.g., CA-SBA-546), but at three of these (CA-SBA-1602, -3579, -4204), those objects appear to be from a later Euro-American occupation (Figure 4). Badly eroding and remnant shell middens at CA-SBA-2595, CA-SBA-4192, and CA-SBA-4195 might be seasonal or satellite localities where people processed shellfish, made tools, and engaged in other activities. This is a pattern noted during the latter half of the Late Holocene, where a variety of smaller shell middens are found alongside large village sites such as CA-SBA-203/541. Our work and other studies confirm the location of Shilimaqshtush at CA-SBA-205 and Shisholop/’Upop at the complex of sites that includes CA-SBA-546, CA-SBA-1503, CA-SBA-1522, and CA-SBA-203/541. Finally, we recorded one new site about 4 km to the interior on Jalama Creek that contains a dense midden dated to the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries and that may be part of the village of Xalam and perhaps associated with adjacent CA-SBA-206. There have long been questions about the location of Xalam, which has not received as much attention as Shilimaqshtush or Shisholop. Johnson (Reference Johnson1988:97, 99) raised the possibility that CA-SBA-1190 at Salsipuedes Creek farther to the interior—rather than Jalama Creek—may have been the location of Xalam. Our radiocarbon dating of CA-SBA-4209, the site location along Jalama Creek, and the diverse contents of the midden suggest that CA-SBA-4209 may be the location of Xalam. Future research is needed to evaluate this assertion and investigate the linkages to the Jalama vineyards and orchards (Harrison Reference Harrison1960; Ruhge Reference Ruhge2009).

Discussion: Kumqaq’ as a Cultural Keystone Place

Our work focused on two overarching questions:

(1) Where and when did people settle along the coast on either side of Kumqaq’?

(2) How do archaeological data on past settlement and land use potentially articulate with ethnohistoric and contemporary Chumash perspectives and the making of a CKP?

When placed in the context of ethnohistoric accounts and contemporary Chumash communities, our archaeological survey and radiocarbon data provide a comprehensive picture of coastal settlement and land use, the creation of trans-Holocene Chumash landscapes, and the Kumqaq’ region as a CKP. This is a story of the region's historical ecology and the long-term persistence and renewal of Chumash peoples at a CKP. Collectively, these archaeological and ethnohistoric data demonstrate that the Kumqaq’ region satisfies all 10 cultural indicators for a CKP (Table 1).

The archaeological sites of the Kumqaq’ region document an archaeological record that attests to diverse Chumash landscapes created over 9,000 years, including the dense villages and satellite sites of the Late Holocene that persist into the historic period communities described in ethnohistoric accounts (Craig et al. Reference Craig and King1978; Gamble Reference Gamble2008; Johnson Reference Johnson1988; King and Craig Reference King and Craig1978). The Sudden Flats Site (CA-SBA-1547), located on VAFB near Point Arguello about 12 km northwest of the JLDP, produced a series of radiocarbon dates and a chipped stone crescent dating to 10,700 cal BP (Lebow et al. Reference Lebow, Harro, McKim, Hodges, Munns, Enright and Haslouer2015). The proximity of the Sudden Flats Site to the JLDP suggests that people were likely at Kumqaq’ in excess of 10,000 years as well. The trans-Holocene Chumash landscapes around the Kumqaq’ coastline contain shell middens, lithic scatters, villages, and a range of other sites. When extended to the interior, there are lithic quarries and workshops, rock art localities, and other sites that represent a diverse range of activities from hunting to plant gathering to ritual and ceremony.

The Chumash villages documented in the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries integrate coastal and interior landscapes at two major drainages, including Shisholop, Shilimaqshtush, and Xalam. Population estimates based on mission census and baptismal data suggest that together these villages were home to approximately 500 people during the mission period (Brown Reference Brown1967; Johnson Reference Johnson1988; McLendon and Johnson Reference McLendon and Johnson1999). These villages were important locations that connected to other villages in the area in complex social networks that included ceremony, ritual, exchange, and intermarriage (see Gamble Reference Gamble2008; Johnson Reference Johnson1988; McLendon and Johnson Reference McLendon and Johnson1999). Kumqaq’ was also a distinct sacred site, especially to Shmuwich and Samala Chumash community members (Erlandson et al. Reference Erlandson, King, Robles, Ruyle, Wilson, Winthrop, Wood, Haley and Wilcoxon1998; Haley and Wilcoxon Reference Haley and Wilcoxon1997, Reference Haley and Wilcoxon1999). People engaged in a broad swath of activities—from fishing, shellfishing, and tomol construction to feasting, ritual, and ceremony—that shaped the cultural landscapes and persistent places of the area (Gamble Reference Gamble2017; Schlanger Reference Schlanger, Rossignol and Wandsnider1992). The complex of sites near the mouth of Cañada del Cojo with some 8,000 years of occupation through to Shisholop, the roughly 6,000 years of occupation at Point Conception proper, and likely other areas that remain to be fully explored also fit the definition of a persistent place (Schlanger Reference Schlanger, Rossignol and Wandsnider1992; Thompson Reference Thompson, Thomas and Sangar2010).

On Santa Cruz Island, El Montón has been documented as a Chumash persistent place, where for 4,000 years people built a mounded landscape complete with a dance floor and cemetery, and there is evidence of feasting and a wide variety of other activities (Gamble Reference Gamble2017). Similar to other discussions of shell middens in the southeastern United States, of Puebloan sites in the American Southwest, and of Paleolithic Europe, these persistent places and the archaeological sites that characterize them are far more than just ancient refuse. They are the physical remains of the social, cultural, political, and ecological activities of the people who left them behind (Gamble Reference Gamble2017; Moore and Thompson Reference Moore and Thompson2012; Schlanger Reference Schlanger, Rossignol and Wandsnider1992; Shaw et al. Reference Shaw, Bates, Conneller, Gamble, Julien, McNabb, Pope and Scott2016; Thompson Reference Thompson, Thomas and Sangar2010). They are places of memory and meaning making that are imbued with deep cultural importance. The villages of the Kumqaq’ area at Shilimaqshtush and Shisholop document this dense and sustained occupation of daily activities, ritual, ceremony, and all facets of social life, but they cannot be removed from the context of the broader landscape, changing environmental conditions, and the numerous diverse sites in the area that reflect a wide range of human activities. Smaller shell middens and lithic scatters attest to the seasonal and other movements of people around the landscape that were actively shaping, managing, and influencing the Point Conception area as part of everyday life and broader ritual and ceremony. Collectively, these activities and the sites or persistent places that represent them create the Chumash landscapes of the area and the making of the CKP.

The establishment of the vineyards and orchards in Jalama Canyon during the mission period and the persistent effects of colonialism and mission activities at Kumqaq’ began a new era of change—one that resulted in the dramatic alteration of local and regional ecosystems and removed many of the original Chumash inhabitants and stewards from the system they had shaped for the entire Holocene (Dartt-Newton and Erlandson Reference Dartt-Newton and Erlandson2013; Gamble Reference Gamble2008; Harrison Reference Harrison1960; Johnson Reference Johnson and Thomas1989b). The ensuing Mexican and American periods ushered in a century of ranching, agriculture, lighthouse construction and activities, and the effects of the Southern Pacific Railroad. Despite disenfranchisement of the Chumash by the missions and dramatic changes to Chumash lifeways due to disease, missionization, and alteration, Chumash descendants continued to visit, live, and work in the area. Fernando Librado Kitsepawit, a well-known Chumash tribal member who was born at the Santa Buenaventura Mission, had Chumash parents from Santa Cruz Island. He was a Mitsqanaqan (Ventureño) and Isleño/Cruzeño speaker, worked on ranches near Point Conception, had broad knowledge of the area, and met extensively with ethnographer John Harrington in the early 1900s (Haley and Wilcoxon Reference Haley and Wilcoxon1999:216; Hudson et al. Reference Hudson, Blackburn, Curletti and Timbrook1977; Johnson Reference Johnson1982). Similarly, Maria Solares, a Samala Chumash tribal member who also worked with Harrington, visited Point Conception at least twice as a midwife for the lighthouse caretaker's wife and on a family camping trip, and she provided great insight into the sacred nature of Kumqaq’ (Haley and Wilcoxon Reference Haley and Wilcoxon1997, Reference Haley and Wilcoxon1999). Fast-forward to the late 1970s, Chumash tribal members again asserted the importance of Kumqaq’ and the area to Chumash life and culture by protesting and successfully preventing the construction of a liquefied natural gas pipeline in the area (Erlandson et al. Reference Erlandson, King, Robles, Ruyle, Wilson, Winthrop, Wood, Haley and Wilcoxon1998; Haley and Wilcoxon Reference Haley and Wilcoxon1997). Today, several Chumash tribal members, particularly from the SYBCI, are direct descendants of Maria Solares or people who lived at Shisholop and have other deep ties to the cultural landscapes and legacies of the Kumqaq’ region. The Chumash ties to the Kumqaq’ region are woven into the shell middens and lithic scatters of the past 9,000 years or more through the villages of the mssion era and into present-day communities. The broader landscapes of Kumqaq’ offer a testament to Chumash persistence and renewal over roughly 10,000 years, a story that is key to the persistence of other California tribes and Indigenous peoples throughout the Americas and beyond (Lightfoot, Panich, et al. Reference Lightfoot, Panich, Schneider, Gonzalez, Russell, Modzelewski, Molino and Blair2013; Panich Reference Panich2016; Schneider Reference Schneider2015).

The story of cultural persistence and connection to the Kumqaq’ region is deeply intertwined with the ecology of Point Conception. As colonialism has worked to remove Indigenous peoples, their histories, and their culture from the landscape, the CKP designation offers a way to further build or rebuild those linkages and to show the deep connections between people and place and between cultural and biological diversity (Cuerrier et al. Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015). An important first step in this work and more effectively managing and preserving the ecosystems and organisms of Point Conception is recognizing the long-term links to the Chumash people, their legacies on the landscapes and coastal ecosystems, and the changes that ensued during the mission, ranching, and modern periods. The CKP framework demonstrates the connections between the area's landscapes and ecosystems and the importance of the area to the Chumash from Shisholop to Shilimaqshtush and Xalam throughout the past 9,000 years (Cuerrier et al. Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015; Lepofsky et al. Reference Lepofsky, Armstrong, Greening, Jackley, Carpenter, Guernsey, Matthews and Turner2017). Whereas we have focused on archaeological sites as physical manifestations of the Chumash landscapes of Kumqaq’, Lepofsky and colleagues (Reference Lepofsky, Armstrong, Greening, Jackley, Carpenter, Guernsey, Matthews and Turner2017) noted that the contemporary plants, animals, and geological features are also crucial to the Pacific Northwest CKPs. This is true for the Kumqaq’ region as well, and it will be a crucial component of work documenting the area's historical ecology through collaboration among the Chumash, TNC, researchers, and other community members in the coming years and decades.

CKPs are an informal designation (i.e., not sanctioned by governments), and some may ask why this designation matters, especially if more formal governmental or other constructs exist. For instance, the 26 acres at Point Conception itself, including the archaeological sites, are an Archaeological District on the National Register of Historic Places (Glassow Reference Glassow1978). That same area was also proposed as a Traditional Cultural Property, another federal designation, but was never formalized (Haley and Wilcoxon Reference Haley and Wilcoxon1997; Wilcoxon Reference Wilcoxon1994). We argue that the less formal CKP designation allows for the recognition of the importance of the larger coastline at Point Conception, including the sacred nature of Kumqaq’, but also the major nearby villages and the cultural landscapes left behind that manifest in the stone tools and other artifacts, faunal remains, plants, animals, and natural features that blanket the landscape of the area. CKP is also a designation that is not static, that recognizes that the past provides a framework with which to understand how we arrived at the present and that can help shape the future, and that does not preclude other more formal governmental designations such as Traditional Cultural Properties (Cuerrier et al. Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015; Lepofsky et al. Reference Lepofsky, Armstrong, Greening, Jackley, Carpenter, Guernsey, Matthews and Turner2017). In this sense, the Kumqaq’ region CKP recognizes, promotes, and celebrates the continued cultural and environmental renewal by contemporary Chumash peoples and ensuing generations. This perspective can also help overturn centuries of erasure of Chumash and other Indigenous peoples from the landscapes of their traditional homelands (see Tonielo et al. Reference Tonielo, Lepofsky, Lertzman-Lepofsky, Salomon and Rowell2019).

Finally, as Lepofsky and colleagues (Reference Lepofsky, Armstrong, Greening, Jackley, Carpenter, Guernsey, Matthews and Turner2017; see also Cuerrier et al. Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015) discuss for CKPs of the Pacific Northwest, recognizing the Kumqaq’ region as a CKP does not mean that it is the only CKP in Chumash territory or that other parts of the area are also not significant. There are likely many others, which should be explored for their significance to California's historical ecology and the legacies of the Chumash past, present, and future written in the landscape.

Conclusions

Identification of 57 archaeological sites and an occupation history spanning 9,000 years or more documents the long-term Chumash histories at Point Conception and the continuum from the deep past, the historic and mission periods, and the present day. The Chumash landscapes of Point Conception manifest in the rich archaeological record of the region and attest to a landscape filled with history, memory, and meaning that coalesce in a CKP (Gamble Reference Gamble2017; Lepofsky et al. Reference Lepofsky, Armstrong, Greening, Jackley, Carpenter, Guernsey, Matthews and Turner2017; Thompson Reference Thompson, Thomas and Sangar2010). The Kumqaq’ region and indeed much of the world are a complex web of human and natural processes that create long-term landscapes that are a mix of cultural and natural processes. Recent global mapping demonstrates that people affected roughly 75% of terrestrial ecosystems around the world by at least 12,000 years ago, and that a key to more effective management is integrating historical ecology and traditional knowledge (Bliege Bird and Nimmo Reference Bliege Bird and Nimmo2018; Ellis et al. Reference Ellis, Gauthier, Goldewijk, Bird, Boivin, Díaz and Fuller2021). Archaeologists continue to emphasize the importance of archaeological research to conservation science and practice and a wide variety of other issues in the Age of Humans, or Anthropocene (Armstrong and Veteto Reference Armstrong and Veteto2015; Armstrong et al. Reference Armstrong, Shoemaker, McKechnie, Ekblom, Szabó, Lane and McAlvay2017; Boivin and Crowther Reference Boivin and Crowther2021; Braje Reference Braje2015; Lightfoot, Cuthrell et al. Reference Lightfoot, Cuthrell, Striplen and Hylkema2013). Meanwhile, we are working to preserve the cultural heritage (archaeology, ethnohistory, contemporary knowledge) that is central to this endeavor but threatened by climate change, development, acculturation, and a myriad of other processes (Erlandson Reference Erlandson2008; McGovern Reference McGovern2018). The CKP framework offers an important means to link cultural and biological diversity, demonstrate the power of archaeology to help understand place, and help Indigenous communities assert their heritage, stewardship, and cultures in a postcolonial world (Cuerrier et al. Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015; Lepofsky et al. Reference Lepofsky, Armstrong, Greening, Jackley, Carpenter, Guernsey, Matthews and Turner2017).

Earlier, we noted that CKPs have received relatively limited attention outside of Canada, a factor due in part to the relatively recent development of the concept (Cuerrier et al. Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015). Our work at Kumqaq’ expands the relevance of CKPs for Native American peoples in California and provides a framework for collaboration that allows Indigenous peoples, archaeologists, anthropologists, and others to assert the cultural and ecological significance of particular places and highlight that significance to the public, governments, and other groups. CKPs can be used in tandem with other designations such as Traditional Cultural Property and Historic Register nominations, but it is also a stand-alone concept that offers fluidity to link the past and present and allow for building histories on the landscape into the future. We hope that others will explore the CKP concept as a tool for linking the long-term cultural and environmental significance of particular places around the world and providing a framework that can empower Indigenous peoples to assert their sovereignty and deep ties to their ancestral homelands. Although CKPs have been used to describe places of significance to Indigenous peoples of North America, Cuerrier and colleagues’ (Reference Cuerrier, Turner, Gomes, Garibaldi and Downing2015) definition is open ended and does not preclude using CKP for other contexts. Future studies could seek to explore an even broader use of CKPs as they apply to a wide range of culturally and environmentally significant places.

Our own work at the JLDP is just beginning, and we anticipate future collaboration among the Chumash, archaeologists, biologists, and others to help restore the long-term natural and cultural environmental links at Point Conception. This collaboration will enhance stewardship and management strategies of the JLDP in an era of rapid change and uncertainty. Point Conception and the JLDP are rich in biodiversity and ecosystems, with bears, mountain lions, bobcats, coyotes, deer, oak woodlands, kelp forests, and rocky intertidal and sandy beaches all playing a pivotal role in the biogeography and ecology of California and the eastern Pacific Coast. The area is also alive with people's history and tradition—from the Chumash to the ranching period to the JLDP. The legacy of Chumash land use, spanning the Holocene, persists throughout the region and continues today with contemporary Chumash communities. The key moving forward is integrating these perspectives to help preserve the ecosystems and Chumash legacies of the Kumqaq’ CKP.

Acknowledgments

We thank the Santa Ynez Band of Chumash Indians Elders’ Council for its help, guidance, and collaboration throughout this research. We are particularly grateful to Elise Tripp for detailed comments and thoughtful guidance. We appreciate the support of the Jack and Laura Dangermond Preserve (JLDP) and the Point Conception Institute. At the Nature Conservancy, we thank Michael Bell, Jay Carlson, Bill Leahy, Moses Katkowski, Karin Lin, Amy Parks, and Laura Riege. Emma Elliott Smith, Elysia Petras, and Hugh Radde provided invaluable help with some of the survey. We also thank Chumash consultants Andrew Mendoza (January survey) and Richard Palato (October survey) for all of their help in the survey. Brian Barbier, Jon Erlandson, Mike Glassow, Brian Haley, John Johnson, Chris Ryan, David Stone, and Larry Wilcoxon provided important insight into past work at the JLDP. Mike Glassow, in particular, was instrumental in locating key documents related to past archaeological research. We thank Erin Sears for help with the Spanish translation of the abstract and keywords. Finally, we thank Lynn Gamble, John Johnson, two anonymous reviewers, and the editorial staff of American Antiquity.

Data Availability Statement

All of the survey data for this article, including radiocarbon dates, are presented in the article, tables, or supplementary materials. A more detailed confidential report (Rick et al. Reference Rick, Braje, Easterday, Graham, Hofman, Holguin and Reeder-Myers2021) and California Department of Recreation site records are available at the Central Coast Information Center, Santa Barbara Museum of Natural History.

Supplemental Material

For supplemental material accompanying this article, visit https://doi.org/10.1017/aaq.2021.154.

Supplemental Table 1. Trans-Holocene Radiocarbon Data for Point Conception Sites.

Supplemental Table 2. Estimates of Site Occupation Spans Using OxCal Boundary Function for Sites with More than One Radiocarbon Date.

Supplemental Table 3. Modeled Interval Gap between the Early and Middle Holocene and the Middle and Late Holocene.

Supplemental Figure 1. Site Spans for all radiocarbon dates at the JLDP grouped by Early, Middle, Late Holocene, and historic periods (produced using the R Package ggplot2).