Introduction

Colleagues, congress participants! Look around you in this hall! You have already heard dozens of speakers from the colonial and semi-colonial countries of Africa, Asia, America and Oceania […] [This] shows the hope and confidence that the working masses of these countries place in our World Federation of Trade Unions, the great international organization of workers. Comrades of all countries, of all races and all religions, united by a common ideal – freedom, prosperity, and peace – I welcome you most warmly on behalf of the millions of workers in the oppressed countries of Africa. I welcome you on behalf of all those who want people to live as brothers in freedom and the working people to work for themselves and not for the capitalists.Footnote 1

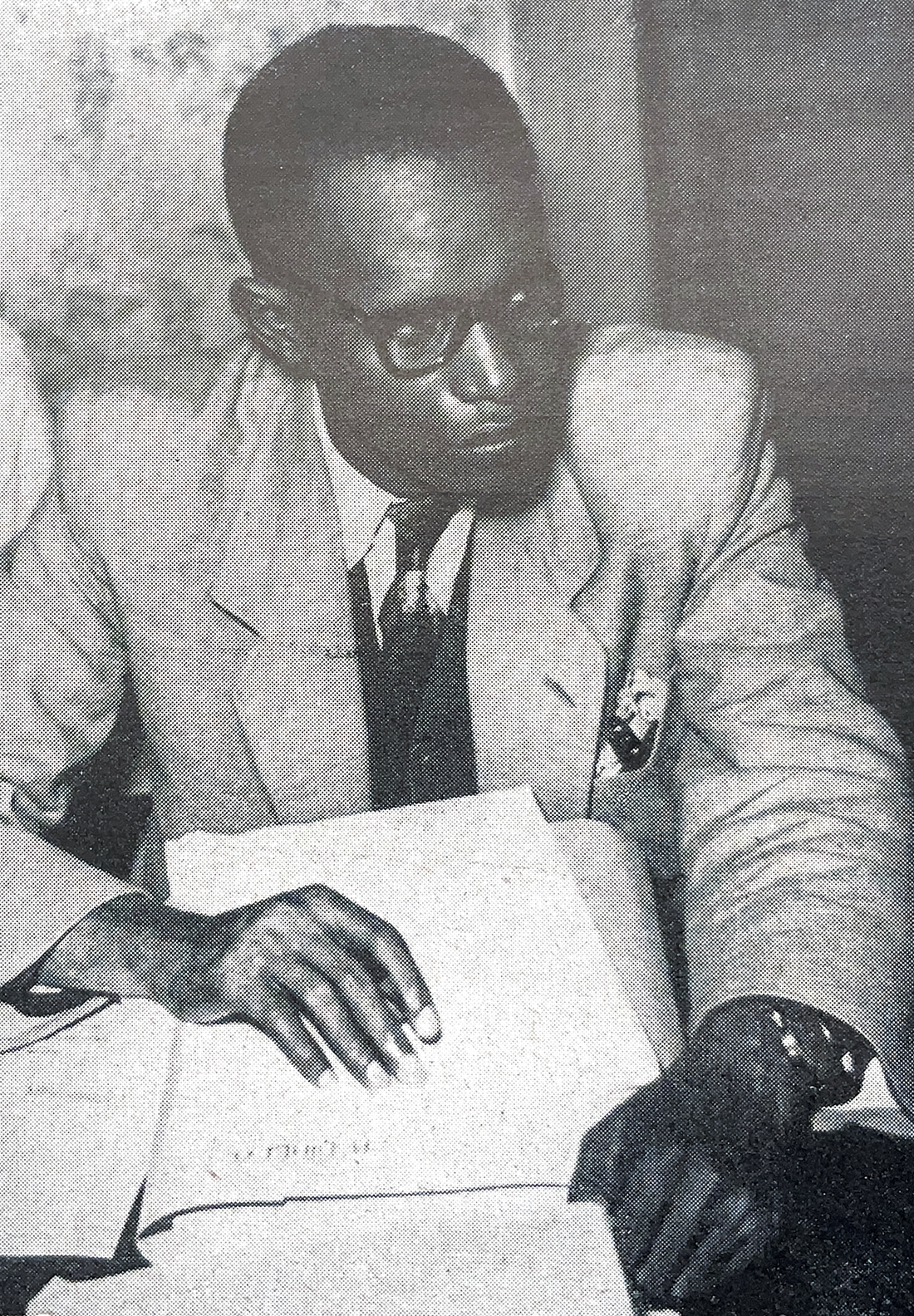

When Abdoulaye Diallo (Figure 1) delivered these opening words at the Third World Congress of the World Federation of Trade Unions (WFTU) in the Soviet-controlled zone of Vienna on 19 October 1953, he was in his thirties and a widely admired African trade union leader, at the height of his reputation within the international labour movement. Introduced in the East German film Lied der Ströme (“Song of the Streams”) as “the representative of African workers”,Footnote 2 Diallo was the most prominent African delegate at the congress. Born in 1917 into a Fulani family with links to both present-day Mali and Guinea, Diallo was educated at the government teachers’ college École normale supérieure William Ponty in Gorée, Senegal. After his studies, he went to work for the public company Poste-Télégraph-Téléphone, which brought him to Bamako in then French Sudan (present-day Mali).Footnote 3 Since 1895, French Sudan had been part of the federation Afrique-Occidentale française (French West Africa), a colonial entity administered from Dakar. In addition to French Sudan, the federation comprised seven other territories: Senegal; Mauritania; Niger; Upper Volta (Burkina Faso); Côte d’Ivoire; Guinea; and Dahomey (Benin).Footnote 4 In 1947, Diallo devoted himself full-time to trade unionism. He was appointed general secretary of the Union régionale des syndicats du Soudan (URSS), a local branch of the French Confédération générale du travail (CGT).Footnote 5 The CGT was founded in the French city of Limoges on 28 September 1895 by seventy-five delegates of various regional and national union federations. The CGT initially defined itself as a confederation of trade unions “outside of all political schools of thought”.Footnote 6 Following World War I, and with the influence of world communism, the labour movement had become heavily politicized, resulting in a split in the CGT and the formation of a separate organization by communist unions. However, in 1936, the CGT merged with the communist unions to form a popular anti-fascist front.Footnote 7 After the French Vichy regime outlawed trade unions, CGT unionists such as Louis Saillant, who would become the general secretary of the WFTU in 1945, actively joined the Résistance.Footnote 8 Towards the end of World War II, the communists gained the upper hand in the CGT.Footnote 9 When the WFTU was established in Paris in October 1945, the CGT was among its founding members. As the CGT had branches in Africa, African unionists were also part of the WFTU.Footnote 10 The CGT enjoyed widespread appeal in French West Africa, with more than half of all unionized workers holding membership between 1945 and 1955.Footnote 11

Figure 1. Portrait picture of Abdoulaye Diallo, taken at the WFTU’s third World Congress in Vienna, October 1953.

In this article, we trace Diallo’s trade union career trajectory from his appearance as a delegate at the pioneering 1947 Pan-African Trade Union Conference in Dakar to his role in the creation of a pan-West African trade union federation, the Union Générale des Travailleurs d’Afrique Noire (UGTAN) in 1957. During this period, Diallo served as a WFTU vice-president (1949–1957). He frequently travelled on behalf of the WFTU and was active in the executive bureau, playing a prominent role at the WFTU’s Third World Congress in Vienna in 1953 alongside campaigns in French West Africa. A fierce anti-colonialist and a vocal and unconditional supporter of the Soviet Union, French colonial officials considered Diallo to be “the most dangerous trade union agitator in French Black Africa”.Footnote 12 The UGTAN’s formation in 1957 precipitated West African unions’ break with the CGT – and, thus, the WFTU – marking a decisive caesura in both metropolitan and international labour politics.

Our research makes three contributions to the current literature. Firstly, our actor-centred approach restores Diallo to his place in the history of international organizations, tracing his speeches, organizing activities, and travels across various WFTU conferences and congresses as well as diplomatic forums.Footnote 13 While Diallo appears in the extensive scholarship on labour and politics in French West Africa,Footnote 14 there is no detailed study of his WFTU career – despite his singular position as the only African to be elected a WFTU vice-president in 1949.Footnote 15 Existing work has highlighted the UN’s Economic and Social Council (ECOSOC) as a stage where colonialism – for example, in Portuguese Africa and Asia – was effectively placed “on trial”. Historians Miguel Bandeira Jerónimo and José Pedro Monteiro have argued that, from the mid-1950s onwards, “the ‘internationalization’ of the Portuguese colonial question” relied on credible evidence and legitimate witnesses from subject populations.Footnote 16 Johanna Wolf has undertaken a detailed examination of the voices of African and Asian unionists at the WFTU’s preparatory founding conference in London in February 1945. Her article also briefly discusses the 1947 Dakar conference, as do studies by Frederick Cooper and Hakim Adi.Footnote 17 Building on and extending these insights, we reposition African trade union officials as strategic actors who navigated, shaped, and leveraged the infrastructures of Cold War internationalism. We draw on scholarship that combines social, labour, and diplomatic history to demonstrate how union leaders acted as “ambassadors of labour”.Footnote 18 This involved combining local mobilization (for example, strikes and organizational work) with a “diplomatic model of trade union internationalism” that presented labour’s demands to “global publics”.Footnote 19 By following Diallo’s institutional ascent and his interventions in transnational arenas, we show how African labour leaders translated local conflicts into global campaigns and thus open up new perspectives on the entangled histories of decolonization, communism, and labour politics.

Our second contribution concerns anti-colonialism in the WFTU both before and after the split. Previous studies have documented the role of US foreign policy goals and the powerful American Federation of Labor (AFL) in hastening the 1949 split and the establishment of a non-communist rival.Footnote 20 These studies prioritize debates on the Marshall Plan and “communist propaganda”, while playing down anti-colonialism. Anthony Carew’s influential account is a prime example of this tendency.Footnote 21 Oliver Pohrt’s German-language monograph on the international trade union movement (2000) is a notable exception, as it reconstructs committees, discussions, and conferences within the united WFTU that addressed the issue of colonialism. Pohrt’s work demonstrates the anxiety of Western labour leaders and diplomats – especially those from the UK, US, and the Netherlands – about WFTU platforms fostering solidarity with African and Asian activists.Footnote 22 More recently, Wolf has argued that the WFTU’s increasingly coordinated demands for self-determination were a key driver of Western withdrawal.Footnote 23 Building on this scholarship, we present new evidence in the form of Diallo’s contributions: at the Dakar conference in 1947, African delegates pressed the unified WFTU to prioritize the demands of colonial workers, while British, US, Belgian, and French officials prioritized curbing communist–colonial linkages over addressing labour coercion. Diallo’s contributions highlighted how colonial authorities and non-communist unionists exploited the concept of “apolitical” trade unionism to divert attention from imperialism. In contrast, communist-affiliated unions, which came to dominate the WFTU after 1949, had endorsed decolonization since the WFTU’s inception in 1945. By centring Diallo’s positions and activism, we re-evaluate explanations of the split, including anti-colonial contention as a structuring tension within the united WFTU that reshaped alignments and strategies across labour internationals.

Our third contribution centres around what the split in 1949 signified for the workers and unionists in “colonial and semi-colonial countries”. We argue that the WFTU’s second world congress in Milan in 1949 – the first congress held after the split – represented a significant opportunity for anti-colonial trade unionists from Africa, Asia, and Latin America. It was only after 1949 that Diallo attained a senior leadership position, as representatives from colonial and semi-colonial contexts assumed greater prominence within the communist-dominated federation. This trend was confirmed at the WFTU’s Vienna congress in 1953. The lack of accessible central WFTU archives has obscured these dynamics and discouraged in-depth study of initiatives from the early 1950s. By reconstructing Diallo’s activities and platforms, we demonstrate how the WFTU provided African leaders with infrastructure, legitimacy, and diplomatic reach at a pivotal moment, presenting the federation as not only a Cold War protagonist, but also a vehicle for decolonization and transcontinental labour diplomacy between 1947 and 1957.

Studying figures such as Diallo – that is, highly mobile trade union leaders from colonial territories who faced persecution – poses several challenges in terms of approach and sources. The multiple arenas, spaces, and organizations involved require careful contextualization and critical analysis. To better understand the WFTU, the labour question in colonial West Africa, and the debates about forced labour and colonial governments’ repression at ECOSOC meetings, we have drawn on (sometimes overlapping) English, French, and German literature on the international labour movement, African labour history, and the history of international organizations.Footnote 24 We also consulted official WFTU publications (mostly in German and English) as well as newspaper articles from the French and Austrian press.Footnote 25 The bulk of archival records stems from the “World Federation of Trade Unions Archives” collection at the International Institute of Social History in Amsterdam and the fonds of the “Confederal Commission of Overseas Territories, Marcel Dufriche Papers” at the CGT’s Institute of Social History (L’Institut CGT d’histoire sociale) in Paris.Footnote 26 We also obtained Diallo’s ECOSOC speeches from the United Nations Digital Library.Footnote 27 Unfortunately, Diallo did not publish a memoir or any other major works, and relatively little of his correspondence has survived (at least in the archives we consulted). Our knowledge of him is therefore mainly based on his speeches and scholarly accounts; we are aware of the limitations this imposes.

The article is structured as follows. First, it examines Diallo’s role at the WFTU’s first Pan-African Trade Union Conference in Dakar in 1947. It shows how the African delegates urged the WFTU, which was unified at the time, to be more inclusive of the demands of workers and unions in French and British colonies. The second section illustrates how Diallo only took on a leading role within the WFTU after its split in 1949, when trade unionists from Africa, Asia, and Latin America joined the communist-dominated federation in large numbers. As the sole African representative on the WFTU executive, Diallo published articles on Africa’s organized labour movement in WFTU publications. These articles are analysed with a view to their anti-colonial, anti-capitalist, and anti-US orientation. The third section examines Diallo’s speeches as the WFTU representative at the ECOSOC meetings in New York in 1950 and Geneva in 1953. It demonstrates how Diallo utilized debates on forced labour and infringements of workers’ and unions’ rights to deliver a broader anti-imperial critique. He argued for an interconnected understanding of colonial capitalism, oppression, and violence against colonized peoples, while uncritically praising the Soviet Union not only for its anti-colonialism but also for having allegedly achieved true economic and social freedom for the working classes. The fourth section examines Diallo’s role at the WFTU’s Third World Congress in Vienna in 1953, promoted as the largest labour congress at the time and attended by dozens of delegations from “colonial and semi-colonial” countries. The congress strongly emphasized the anti-colonial struggle, and the following months saw intense labour disputes and changes in French West Africa. Finally, the fifth section examines the contradictory role that Diallo played in establishing an autonomous trade union federation in French West Africa. His determination to keep African unions within the CGT and WFTU put him under increasing pressure from the Guinean union leader Sékou Touré. The French colonial administration prioritized anti-communist gains and supported Touré’s mission to break the CGT’s influence in French West Africa.

Overall, our research restores African trade unionists to their place in history as shapers of international organizations by reconstructing Diallo’s trajectory across WFTU congresses, ECOSOC forums, and his extensive travels in the period from 1947 to 1957. This fills a long-standing gap in the literature and draws attention to figures like Diallo who, as “ambassadors of labour”, connected local struggles with global audiences.

The United WFTU’s 1947 Pan-African Trade Union Conference in Dakar (French West Africa)

The founding of the WFTU in Paris in 1945 by union officials from around the globe was driven by a shared hope that a peaceful and just world order could be created. For the first time in history, this global federation united labour movements of all ideological persuasions under the banner of anti-fascism, global solidarity, and the elimination of social inequalities.Footnote 28 The fierce criticism of labour relations in the colonies by Africans, who spoke out against injustice and colonial oppression, was undoubtedly uncomfortable for European and North American trade union officials, often because of the African delegates’ unconditional enthusiasm for the Soviet Union.Footnote 29 From the WFTU’s founding congress onwards, British and US union leaders in particular were keen to keep the WFTU as an “apolitical” trade union organization, devoted solely to narrow workplace issues. Walter Citrine, the president of the British Trade Unions Congress (TUC) and first president of the WFTU, warned that if the WFTU were to “get into the maze of politics” then it would “perish”.Footnote 30 African (and Asian) labour leaders also came to realize early on that limiting debates to “non-political” issues was a convenient way for institutions and organizations embedded in the colonial empire not only to maintain unequal power structures, but also to stifle any critical thinking by branding it as “political”.Footnote 31 As a result, at the WFTU’s 1945 founding conference, African and Asian trade unionists almost exclusively sided with the communist/socialist trade union federations on this issue, arguing that if the WFTU were to have any advantage for colonized peoples it would necessarily have to enter into “politics”.Footnote 32

The emphasis on “apolitical” trade unionism also explains the active neglect and repression of debates on colonial issues by British labour organizations. British union officials obstructed a joint anti-colonial policy within the united WFTU.Footnote 33 The WFTU’s Colonial Department became operational only after a six-month delay, following pressure from the federation’s French general secretary Louis Saillant and the Soviet official Vasily Vasilyevich Kuznetsov.Footnote 34 The US Congress of Industrial Organizations (CIO) was allowed to appoint an official to head the department: Adolphe Germer. Pohrt characterizes his tenure as one of “low activity”, while Jon Kofas describes him as an “anti-communist”.Footnote 35

In the face of opposition from powerful players such as the TUC, the CIO, and the US government, it is remarkable that the first Pan-African Trade Union Conference of the united WFTU was held in Dakar, the capital of French West Africa, from 10 to 13 April 1947.Footnote 36 According to Babacar Fall, delegates from eighteen trade union organizations attended, representing 763,000 African workers in Belgian-, French-, and British-ruled Africa.Footnote 37 As the archival records show, delegates came from Morocco, Senegal, the Ivory Coast, Mauritania, the Belgian Congo, Togo, Guinea, Cameroon, Sierra Leone, and Nigeria, and from both European and non-European unions in South Africa.Footnote 38

White European and North American labour leaders prepared the conference and oversaw the proceedings. The conference was chaired by CIO delegate Adolphe Germer, with other leading functionaries including H.B. Kemmis of the British TUC’s Colonial Committee, Mikhail Faline of the Soviet Union’s national trade union federation, the All-Union Central Council of Trade Unions (ACCTU), and André Tollet and Albert Bouzanquet of the CGT. Walter Schevenels, introduced as a “Belgian delegate”, who had been a key figure in the International Federation of Trade Unions (IFTU) in the interwar period,Footnote 39 played an important role as moderator and translator between French and English.Footnote 40 Germer’s cautious opening statement excluded the fundamentally “political” question of colonial rule. He dampened the aspirations of the African delegates by making it clear that the conference was a “fact-finding mission” about labour conditions across the African continent under the auspices of the WFTU and had “no decision-making power”.Footnote 41

At the beginning of his speech, Diallo, representing the CGT unions in French Sudan, greeted the WFTU delegates and singled out the Soviet delegate, Faline, saying that he was “all the more pleased by his presence as our Soviet comrades have no colonies”.Footnote 42 We assume that, in addition to depicting the Soviet Union as a country without any colonies, the decision to mention Faline by name was related to his important role in organizing the Dakar conference. Faline worked alongside Germer in the WFTU’s Colonial Department. Since Germer did not speak French, Faline was responsible for acting as the main contact person in the conference preparations.Footnote 43 Diallo’s speech also demonstrates his strong support for the Soviet Union in 1947. The same line of argument was continued in his later speeches as a WFTU delegate at UN ECOSOC meetings, as we shall see later.

At the Dakar conference in 1947, Diallo further emphasized how entrenched colonial rule was in Africa, arguing that “the African continent is the only continent in the world that consists only of colonies” and is therefore “open to exploitation”.Footnote 44 The French Sudanese trade union leader then provided an overview of early trade union activity in his territory, describing how the “terrible experiences” of World War II had accelerated the desire to organize and mobilize.Footnote 45 Diallo highlighted the strike of 8 July 1946 in Bamako, which began among government workers and then spread to the rest of the country, as a “landmark date for workers”, since the colonial administration was pushed into making “many concessions”.Footnote 46

As historians have shown, the immediate post-war period in French West Africa was marked by an upsurge in union activity linked to financial demands by workers for higher wages, family allowances, and better housing. Persistent shortages and overpopulation in the capital cities put pressure on both jobs and workers’ purchasing power.Footnote 47 Faced with this situation, workers in French West Africa responded with general strikes, the first of which was organized by commercial workers in Dakar in January and February 1946.Footnote 48 This dynamic extended not only to the French Sudan through the movement of July 1946, as mentioned by Diallo, but also to the whole of French West Africa through the railway workers’ strike, which lasted from 10 October 1947 until 19 March 1948. Involving almost 20,000 strikers from all the territories of the federation and lasting 170 days, Fall characterizes the strike as “the most memorable event in the collective memory of French-speaking West Africa after World War II”.Footnote 49 The strike wave caused widespread surprise: “Obviously, this [strike] movement surprised the bosses, surprised the administration, and surprised our comrades in the French CGT, who are not indifferent to the welfare of African workers.”Footnote 50 As Jean Suret-Canale has noted, it was effectively through and during the strikes of 1945 and 1946 that the communist CGT gained much popularity among African workers in French West Africa and that closer connections were forged between French and African union leaders.Footnote 51 As the French Communist Party was still part of the governing coalition in France (until May 1947), the CGT was able to invite African trade union leaders to its congresses and training sessions with the government’s approval. Gédéon Bangali has argued that this strategy fostered the emergence of African trade union leaders within the CGT, who went on to become highly influential figures throughout French West and Equatorial Africa. These CGT-trained leaders included Diallo in the French Sudan, Touré, future president of independent Guinea, and Bakary Djibo in Niger. Following their training in France, these leaders played a pivotal role in increasing CGT membership across French West and Equatorial Africa, mobilizing and organizing workers through speeches and publications advocating for workers’ rights and later the anti-colonial struggle.Footnote 52 However, as discussed below, by 1949 Diallo had surpassed both Touré and Djibo on the international stage, as he was the only African among the vice-presidents of the WFTU. Diallo’s background of involvement in workers’ struggles across French West Africa and training with the CGT in France explains not only his emphasis on coordinated action, but also the focus on wage discrimination that can be observed in his speech at the 1947 conference in Dakar. He considered the lack of collective agreements in the private sector a huge challenge, critically noting that “the highest-paid African worker earns less than the lowest paid European worker, and this constitutes a barrier”.Footnote 53 As Cooper has shown, “citizenship talk” that emphasized equal rights and opportunities for all citizens of the French empire, regardless of their origin and skin colour, gained popularity in French West Africa during the 1940s. In 1945, for example, the Senegalese politician Lamine Guèye called for “the equality of races and peoples” as well as for “the accession of all Africans to citizenship”.Footnote 54 Workers, including civil servants such as teachers but also blue-collar workers on the railways and docks, rallied behind the slogan “Equal pay for equal work” in the strike wave that started in Senegal in December 1945.Footnote 55 Building on the then prevalent discourse emphasizing equality and anti-racism within the French empire, Diallo rejected racialized ideas of productivity in his 1947 speech in Dakar:

Well, comrades, I offer you this testimony before the whole world, before the WFTU, that everywhere workers, whether they are white, black, or yellow, have the same output, depending on the circumstances, the training, the laws they are given. Here we have black chief accountants of commercial organizations who are doing very well, and they earn three or four times less than the white accountants. We sometimes have Africans in offices who do the same work as the Europeans who are the bosses.Footnote 56

As Bandeira Jerónimo and Pedro Monteiro have argued with regard to anti-colonial activism in the Portuguese empire, African activists were increasingly able to present themselves as “legitimate interlocutors in international discussions” over labour rights and human rights in the colonies from the mid-1950s onwards.Footnote 57 In French West Africa, as Cooper has shown, these trends set in much earlier. At the 1947 Dakar conference, Diallo asked for support from the “global union”, by which he meant the WFTU, as well as from the CGT, to publicize these struggles by African workers and unionists.Footnote 58 His reference to “the whole world, in front of the WFTU” clearly shows how Africans understood the Pan-African Trade Union Conference, which had been organized by the united WFTU, as an event for “global publics”, with the expectation that it would reach audiences and associations across Africa, Europe, Asia, and the Americas.Footnote 59 Diallo strove to use this international stage to “put on trial” the unequal pay of white and black workers and employees, and to express his fundamentally anti-racist stance.Footnote 60

Consequently, media outreach and coverage were a hotly debated issue between the (white) organizers and chairpersons and the African delegates both during and after the conference. Wynant (first name unknown), a union official from the Belgian Congo, expressed surprise that the conference had received so little press coverage and urged the WFTU to aim for “maximum publicity”. Schevenels replied that the low profile was a strategy of the conference’s (mostly European) organizers to “protect the African trade union delegates from subsequent reprisals”.Footnote 61 However one analyses these explanations, they contain uncomfortable truths for union officials from colonial metropoles. If Schevenels’s statement is accepted at face value, it would suggest that colonial rule was oppressive for African workers and unionists. Conversely, if this was a deliberate strategy to circumvent the widespread dissemination of African union officials’ testimonies, it serves as a compelling indication of how the organizing union officials from the colonial metropoles sought to shift the focus from the “global publics” anticipated by African officials to a more localized audience. The African delegates were unimpressed by these explanations and, after consultation, “unanimously decided to admit the press”. Wynant argued that the aim of the conference was “to enlighten public opinion about the miserable conditions of African workers and to show the urgency of finding a remedy for them”.Footnote 62

The conference resolutions demanded “immediate action” on several issues, such as a guarantee of trade union rights in line with the UN’s ECOSOC resolution, the establishment of a system of social security, and improvements in the overall standard of living and access to education. It was suggested that special WFTU representatives should work with the governments of the UK, France, Belgium, and South Africa as well as within ECOSOC on the implementation of these demands.Footnote 63

In the aftermath of the Pan-African Trade Union Conference, many African delegates were disappointed that it was the European WFTU leaders who discussed which of the conference’s resolutions would be forwarded to ECOSOC and the International Labour Organization (ILO). Mikhail Tarasov, a Soviet member of the WFTU’s Colonial Department, complained that African members were not involved in these decisions, and suggested that an African delegate should be hired in the Colonial Department.Footnote 64 This clearly shows that, in the early days of the united WFTU, decision-making was the exclusive preserve of white trade union leaders from North America, Europe, and the Soviet Union. The hopes of African delegates such as Diallo to “educate public opinion” about Africa being “open to exploitation” and to put pressure on colonial governments through global outreach and international organizations such as the UN were not fulfilled within the united WFTU. This was to change after the split in 1949, as we highlight in the next section.

After the Split in 1949: A West African Union Leader as WFTU Vice-President

The remaining twenty or so months between the Pan-African Trade Union Conference in April 1947 and the split of the WFTU in January 1949 brought far-reaching changes in France, its colonies, and the international labour movement. In Paris, amidst massive workers’ unrest, the French Communist Party was ousted from the governing coalition and went into opposition in May 1947.Footnote 65 Immediately, the CGT and its political ally in the colonies, the African Democratic Assembly,Footnote 66 were subjected to numerous police and administrative harassments.Footnote 67 A massive wave of strikes also swept across French West Africa, culminating in the aforementioned 170-day strike between 1947 and 1948.

In June 1947, the US government announced the European Recovery Program (Marshall Plan) for Europe’s post-war reconstruction, which was intensely debated across Western and Eastern Europe. Part of the money included in the Marshall Plan was intended to weaken communist influence in the labour movement. The US government and the AFL, which did not join the WFTU, sought to destroy the unity between communists and non-communists both on the national level and within the WFTU.Footnote 68 In France, with financial and logistical support from the AFL, the CIA, and the US State Department, socialist union leaders of the CGT decided to break away to form the CGT-Force Ouvrière.Footnote 69 The new trade union federation tried to compete with the CGT in French West Africa for African workers, but was largely unsuccessful.Footnote 70 At the international level, differences over the Marshall Plan, the colonial question, and the strong influence of communist-leaning officials on WFTU publications seemed irreconcilable by January 1949. Feeling that they could no longer adequately control the WFTU, the British TUC, the American CIO, Scandinavian union organizations, and soon the remaining non-communist unions left the federation to form a new one, the International Confederation of Free Trade Unions (ICFTU).Footnote 71

How did the WFTU’s policy and structural orientation towards the colonies in Africa and Asia change after the split in 1949? Labour historian Bob Reinalda has proposed several dimensions for describing the structure of an international trade union federation: firstly, the extent of its internationalist structure; secondly, the purpose of its overall strategy and strategic consciousness; and thirdly, its structural inclusiveness (referring to whether the movement is sensitive to the dimensions of gender, race, and regional balance).Footnote 72 In 1949, the WFTU’s two leading governing bodies, the general council and executive bureau, (re-)elected two white male European communists as leaders: Louis Saillant from the French CGT as general secretary and Guiseppe di Vittorio from the Italian General Confederation of Labour (CGIL) as president. While the two leading positions were thus firmly in the hands of European communist parties, the executive bureau also elected non-European leaders. Out of the eleven vice-presidents, six hailed from Africa, Asia, and Latin America: Vincente Lombardo Toledano (Mexico); Liu Chao Chin (China); Shripad A. Dange (India); Lázaro Peña (Cuba); and Abdoulaye Diallo (French Sudan).Footnote 73 More in-depth comparative research is needed, but looking at the list of leading functionaries within the ICFTU at the same time, we can already see a stark difference in terms of origin. After its London congress in November/December 1949, the new federation was led exclusively by white male union leaders from Western Europe and North America.Footnote 74 While neither the WFTU nor the ICFTU had any female officials in their leading bodies at the time, and so could not be considered gender-inclusive, the WFTU underscored its desire to open up beyond Eurasia by appointing vice-presidents from Africa, Asia, and Latin America.Footnote 75

Diallo’s new position as vice-president provided authority and access to the WFTU’s publication outlets. Soon after his appointment, he published his views on the African trade union movement in a lengthy article in the WFTU bulletin Weltgewerkschaftsbewegung (“World Trade Union Movement”).Footnote 76 Diallo noted Africans’ support for the fight against fascism and the goals of anti-racism, freedom, and self-determination, as set out in the Atlantic Charter. He emphasized the contribution of workers, including unorganized workers, who had mounted strikes against the colonial administrations on plantations, in workshops, and in mines, as well as the importance of the 1947 Dakar conference (as discussed above) in highlighting “the excessive exploitation of the natives by the imperialist mother countries, as well as racial discrimination, the absence or restriction of trade union freedoms, the lack of education, the low standard of living, and the misery of the peasants”.Footnote 77

Diallo called on African trade unionists and workers not to sit back and wait for the WFTU to solve their problems as a “central organ”, but to take action themselves: to organize, mobilize, and struggle. It is noteworthy that, as early as 1949, Diallo pointed to inter-African unity and trade union cooperation as a way “to derive greater benefit from the experience of struggle acquired together”. However, it is important to stress that he opposed an “isolationist” view, arguing that the African labour movement must not allow its struggle to be diverted from the right path by isolating itself from the working class in the mother countries and other countries of the world. Their struggle would not be a race war between blacks and whites, or of Africans against Europeans and Asians, but rather a united front against imperialism and colonial oppression.Footnote 78

The statement must be read as a clear commitment to waging African struggles as part of the CGT and WFTU. As a “labour ambassador”, who had been elected to the WFTU leadership to write and speak about the African labour movement from the perspective of an active trade unionist, and someone who had experienced and was still experiencing colonial rule, Diallo was also firmly committed to a materialist approach to the colonial (labour) question. This included a strong commitment to class analysis and communist labour internationalism, which sidelined the importance of race by emphasizing that “blacks and whites” could work together in a “united front against imperialism and colonial oppression”. Scholars have shown that African workers and trade unionists in Francophone Africa were more receptive to Marxist ideology and materialist analysis than their counterparts in British-ruled Africa. Several factors can explain this. From 1943 onwards, Communist Study Groups (Groupes d’études communistes, GEC) had been founded in Dakar, Conakry, and Abidjan to disseminate Marxist thought.Footnote 79 Furthermore, after World War II, the French Communist Party had a greater influence in France’s colonies than the British Communist Party did in Britain’s. As mentioned above, trade unionists such as Touré from Guinea, Diallo from Sudan, and Djibo from Niger had been invited to CGT congresses in France and received training under the auspices of the CGT and the French Communist Party.Footnote 80 However, Diallo’s position increasingly came into conflict with that of Touré, who pushed for the autonomy (and disaffiliation) of African unions from French and international federations. We will return to these conflicts in the final section.

The purpose of Diallo’s article in Weltgewerkschaftsbewegung was not limited to exploring the African labour movement, however. Carew has described how the WFTU’s Information Bulletin and other publications emerged as a key battleground for campaigning for or against the US government’s Marshall Plan in 1947 to 1948. The Bulletin of the then united WFTU, Carew found, “was used in ever more blatantly partisan fashion” by communist-leaning officials from different trade unions to mobilize support against the Marshall Plan.Footnote 81

Following the split in 1949, when the Western non-communist federations left the WFTU, it is not surprising that anti-Western and, in particular, anti-US positions continued to be very pronounced in WFTU publications. The articles in the WFTU’s Weltgewerkschaftsbewegung bulletin highlight this orientation. Diallo’s article on the African labour movement, for example, includes a headline, “The increasing influence of American monopolies is aggravating the misery of the peoples of Africa”, which is in the same font size and is almost the same length as the main headline on Africa’s organized labour movement. Mirroring the battle lines of the intensifying Cold War, the article focuses on the strategies of “imperialist monopolies to gain dominance over Africa’s economy”. Diallo argues that US “trusts and monopolies” were gradually taking over market positions from their British, French, and Belgian competitors, although he only mentions Firestone and US Steel by name. However, to illustrate “intruding American capital”, he provides detailed examples of recent US investments in several African colonies. According to Diallo, these aimed at exploiting the continent’s rich resources, such as copper, cobalt, zinc, lead, uranium, bauxite, gold, and diamonds.Footnote 82

Diallo’s article was clearly considered a powerful intellectual weapon in the Cold War by the WFTU’s Publications Department. Considerable space was devoted to criticizing Western imperial powers, particularly the US, for exploiting Africa’s strategic resources, while the Soviet Union was praised. The US government followed these publications closely. CIA reports from the 1950s noted that the responsible secretary in charge of the WFTU Press and Information Department was typically a Soviet functionary overseeing the final output.Footnote 83 Given the ACCTU’s dominant position within the WFTU in terms of membership and financial contributions, we can also assume that high-ranking Soviet trade union leaders, in coordination with the Soviet regime, oversaw these publications. However, more research is needed to better understand these processes.Footnote 84 We know from recent research that, in addition to African leaders such as Diallo, Western communists from Britain and France, such as Jack Woddis, T. McWhinnie, Paul Delanoue, and Maurice Gastaud, played an important role in collecting and disseminating knowledge about the African labour movement within their respective communist parties, trade union organizations, and/or the WFTU. Insight into the labour situation in Africa was often gained through trips to Africa or discussions with/training of African colleagues.Footnote 85 Following Stalin’s purges and persecution of many leading (Soviet) internationalists and academics who had gathered knowledge about and built networks with the colonial world, Soviet knowledge of Africa, and in particular its labour movement, was very limited during the 1950s, and access for its scholars to conduct fieldwork very difficult.Footnote 86 In any case, more in-depth research into the WFTU’s publishing nexus would be needed to better understand how articles such as Diallo’s were (co-)produced, who was involved, and how a final version was agreed.

Diallo’s election as WFTU vice-president also boosted his international mobility and prestige, as he travelled extensively around the world and was at the forefront of all the latest trade union and political developments from the late 1940s onwards. In November and December 1949, he was part of a WFTU delegation to Beijing, together with General Secretary Louis Saillant, the Soviet delegate Leonid Nikolaievich Soloviev, Vincente Lombardo Toledano (Confederation of Latin American Workers), and Ali Mardjono (Central All-Indonesian Workers Organization, SOBSI).Footnote 87 The capital of the new People’s Republic of China hosted the Pan-Asian Trade Union Conference between 15 November and 8 December 1949, with delegates from countries including Indonesia, India, Iran, Vietnam, Korea, and Mongolia.Footnote 88 Saillant, Diallo, and the other WFTU vice-presidents delivered speeches and met with Chairman Mao Zedong for discussions.Footnote 89 The rise of communist China was of great importance to the WFTU, and Diallo was clearly impressed by China’s example. At the WFTU’s Third World Congress in Vienna four years later, which will be discussed below, Diallo highlighted China as a leading example of a nation that had liberated itself from the yoke of colonialism and offered hope and inspiration to Africans.Footnote 90 In addition to delegation visits within the communist camp, which also saw Diallo travelling to the newly founded East Germany (officially the German Democratic Republic), he emphasized his role as communist ambassador of Africa’s labour movement at UN meetings in Geneva and New York.

Diallo as WFTU Representative at Meetings of the United Nations’ Economic and Social Council

At the WFTU preparatory conference in London in February 1945, trade union leaders demanded that the federation be given an advisory role at the UN founding conference, which would take place in San Francisco on 26 June that year.Footnote 91 The Soviet proposal was renewed at the WFTU’s founding congress in Paris in October 1945, calling for the federation’s participation in ECOSOC with voting rights.Footnote 92

The ECOSOC was established on 26 June 1945 as one of the six main organs of the UN, with the remit to coordinate its economic and social fields. The forum continues to function as the UN’s principal platform for deliberating on international economic and social issues.Footnote 93 ECOSOC was designed with eighteen council members, with Africa and Asia “grossly underrepresented” in council membership (since no colonies were allowed a seat).Footnote 94 After much debate, the united WFTU was granted, alongside other organizations such as the AFL, consultative status for non-governmental organizations within ECOSOC.Footnote 95 After the split of the WFTU in 1949, the US government and the AFL unsuccessfully tried to revoke the WFTU’s consultative status.Footnote 96

For communist labour leaders from colonial territories, such as Diallo, the WFTU seat in ECOSOC was a great opportunity to bring African anti-colonial perspectives to the world forum. As Cooper has noted, international organizations could “become embarrassing sites for questioning the seriousness of the modernizing project”.Footnote 97

The debate in New York in 1950 focused on forced labour. It developed into a confrontation, with blame alternately assigned to the Soviet Union and the colonial powers, particularly France. In 1947, the AFL urged ECOSOC to commission the ILO to undertake a detailed examination of “new systems of forced labour”; this was primarily intended to target the Soviet gulags.Footnote 98 Quenby Olmsted Hughes has given a detailed account of the AFL’s campaign to expose forced labour in the Soviet Union at ECOSOC.Footnote 99 AFL delegate Toni Sender accused the Soviet Union of a “system of forced labour” and argued that, in view of mass “arrests and deportations in the Baltic States”, from where prisoners were being “sent to slave labour camps”, it “was not exaggerated to speak of the crime of genocide”.Footnote 100 From a comparative perspective, it is important to note that Sender was not interrupted once during her lengthy speech and that the president of the session, the Chilean Hernán Santa Cruz,Footnote 101 “thanked Miss Sender for her statement”.Footnote 102

When Diallo took the floor as WFTU representative, he critically noted that despite having been eliminated on paper in the French empire in 1946, forced labour was on the rise in the “non-self-governing territories” (that is, the colonies). He added that due to resistance by workers, “police methods” had been used by regimes to impose forced labour in the colonies. He gave the example of the French government, which he criticized for its repression of people in Vietnam, strikers in Tunisia, and trade unionists in Morocco and the Ivory Coast.Footnote 103 Without hesitation, Mr Boris, the French government’s designated representative, was granted the opportunity to interject, as Diallo had expanded the discussion beyond the topic of forced labour. The session president, Santa Cruz, agreed with Boris. He understood that it was difficult to avoid making reference to repression when talking about forced labour but felt that “the consultant from the World Federation of Trade Unions” – that is, Diallo – “seemed to have overstepped reasonable limits”. Santa Cruz urged Diallo to deal exclusively with “facts relating to the question of forced labour”.Footnote 104 This shows how the French delegate, Boris, supported by the session’s president, sought to divide the issue of forced labour from that of colonial rule and political repression by colonial governments.

However, Diallo did not agree with this narrow perspective. He claimed that the WFTU “wished to denounce before the Council all the violations of freedom which were contrary to the principles set forth in the United Nations Charter”.Footnote 105 Unimpressed, he provided a detailed explanation for why a number of measures, such as “institution of the compulsory labour card, punitive sanctions, imprisonment for failure to pay taxes, labour in prisons […], mass recruitment by special agents or tribal chiefs”, were very similar in effect to “former laws on forced labour”. As a result, he argued, despite the abolition of forced labour in the aftermath of World War II, these illegal practices persisted in Francophone Africa for public infrastructure works as well as in British colonies such as Tanganyika, Kenya, and Nigeria. Diallo invoked the UN’s charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights of 1948 to oppose this inhumane treatment of people in the colonies.Footnote 106 When he argued that colonial governments sometimes used “cynical or hypocritical arguments”Footnote 107 to justify forced labour of their subjects, Diallo was again “called to order” by Santa Cruz.

Seemingly undeterred by Santa Cruz’s interventions during the session calling on him to refrain from direct attacks, Diallo continued. He argued that the Western “trusts and monopolies” were the real cause of forced labour. “Above all,” Diallo went on, “it was essential to abolish the colonial system, which ran counter to the principles of the United Nations Charter.”Footnote 108 Diallo was again interrupted by Santa Cruz, called to order, and warned that “if he did not confine his remarks to the question on the agenda and spoke on general political issues, his right to speak would be withdrawn”.Footnote 109 However, Diallo was able to continue, and, in the remaining part of his speech, he offered uncritical praise of the Soviet Union. He believed that the AFL’s campaign against forced labour in the Soviet Union comprised “lying accusations […] against the great socialist country”. Due to the institutionalized racism in the US, the AFL’s “attacks” were hypocritical and “merely intended to counteract the attraction exerted by the USSR on colonial and semi-colonial workers”.Footnote 110 Certainly unaware of the extent of forced labour under Stalin, Diallo uncritically praised the Soviet Union as a place where “workers enjoyed true economic and social freedom” and ultimately a “harmonious society”.Footnote 111 The French delegate, Boris, argued at the end of the debate that if communist representatives were unaware of forced labour in the Soviet Union “either because they had not asked or had not been told, theirs was a clear case of monastic obedience and fanaticism”.Footnote 112

Three years later, Diallo served as the WFTU’s representative at the July 1953 ECOSOC meeting in Geneva. As vice-president of the WFTU, he fiercely criticized the harassment and imprisonment of trade union leaders in both metropolitan France and the African colonies. He was particularly concerned that “it was quite common for trade union publications, particularly those of WFTU, to be declared illegal. Trade union meetings were subject to prior authorization, while trade union funds were subject to State control.”Footnote 113 Since Diallo’s first speech to ECOSOC in 1950, as discussed above, the climate had become increasingly repressive for the WFTU and especially for the CGT, the French communist trade union federation. In 1950, the now communist-oriented WFTU sought to hold a second Pan-African Trade Union Conference in Douala, Cameroon, as a follow-up to the 1947 Dakar conference discussed earlier. The French high commissioner in Cameroon refused Diallo’s request to hold a conference in October 1950.Footnote 114 In late January 1951, the Journal officiel de la République française published the decree that the WFTU was banned in France, and some of its leaders had to flee the country.Footnote 115 The WFTU headquarters were moved to the Soviet-occupied zone in Vienna.Footnote 116 The French government also banned the WFTU from any activities in French West Africa, and British colonial authorities, including those in Nigeria and Northern Rhodesia, banned the import of WFTU publications.Footnote 117

The WFTU filed a complaint with ECOSOC against the French government’s repression of the CGT, the WFTU, and trade unionists in both France and the colonies. It argued that these measures violated the “democratic rights” and “freedom of association” of trade unionists.Footnote 118 Similar to the 1950 meeting, the session’s president, the Belgian Raymond Scheyven, opted for a “technical” approach as a prophylactic measure, warning Diallo that speakers should “confine themselves to the technical approach” and asked representatives of international organizations to recognize the “unanimous wish of the Council that politics should not be allowed to intrude into the discussion”.Footnote 119 It was precisely the allegedly neutral and apolitical “technical” approach that Diallo went on to criticize in his speech. He felt that the ILO’s investigation had handled the issue of infringement of trade union rights unsatisfactorily, since Western governments’ overt repression was exonerated on the grounds that it targeted “subversive activities” in the “interest of public order”.Footnote 120 Diallo’s criticism requires more contextualization. As the historian Daniel Maul has shown, the 1953 ILO report found British and French colonial policy “‘not guilty’ of forced labour”. The report “only criticized France and Britain for occasionally using the terms ‘state of emergency’ and ‘civic duties’ too freely in their justification of continuing forms of coercion”.Footnote 121

In the name of the WFTU, Diallo demanded that the allegations of infringements of trade union rights be widely publicized and that Western influence within the ILO be reduced.Footnote 122 As Maul has convincingly shown, the influence of Western governments and an attitude of maintaining the colonial status quo was strong within ILO bodies, and so it is understandable that more radical figures from the colonies did not trust the ILO to handle these issues to their advantage.Footnote 123

Overall, our research shows how African “labour ambassadors”, such as Diallo, used their speeches at ECOSOC meetings to criticize the exploitation and labour policies of the colonial empires. While praising the Soviet Union, Diallo presented the communist labour movement and, above all, the WFTU that functioned as its umbrella organization as defenders of democratic rights and freedom of association in both France and the African colonies at international forums such as the UN. In doing so, he challenged the Western anti-communist discourse that sought to discredit the WFTU on the basis that its bedrock was trade union federations in Eastern Europe and the Soviet Union, which served as a “transmission belt” between the ruling communist parties and the working classes and peasants.

The WFTU’s Third World Congress in Vienna, 1953, and Diallo’s Arrest in French West Africa

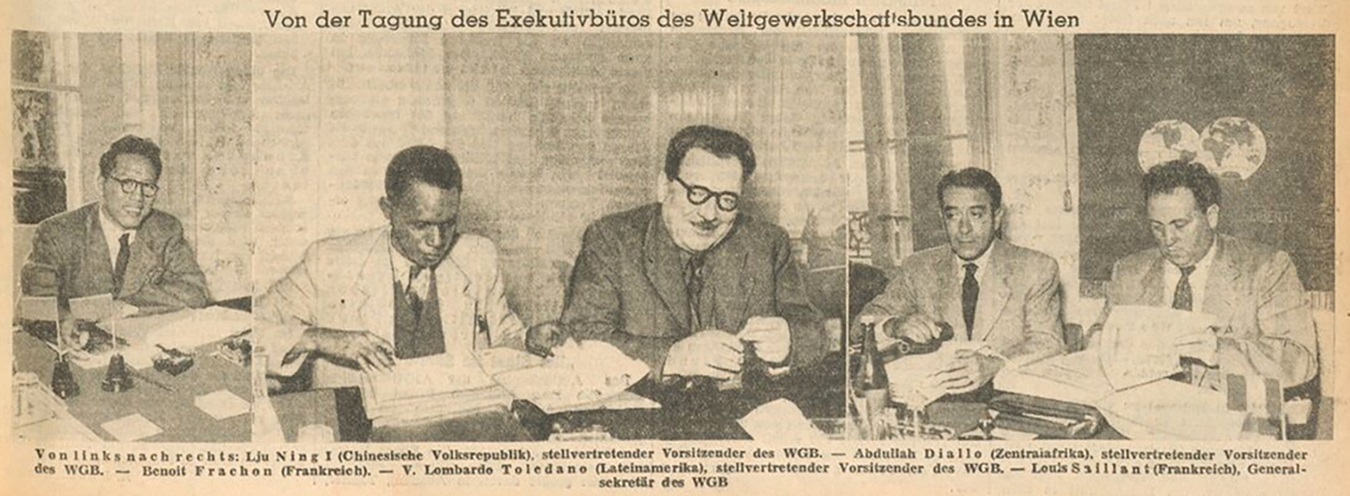

Following its expulsion from Paris in 1951, the WFTU moved its headquarters to the Soviet-occupied zone in Vienna. This development was not welcomed by the Austrian anti-communist press. The Wiener Kurier lamented in 1951 that the WFTU’s presence regularly brought “prominent communists” from the WFTU – such as Saillant, Toledano, Benoît Frachon, di Vittorio, Lju Ning, and Diallo – to executive bureau meetings in Vienna and that the city had become a “conference hotspot for the communist front organization” (Figure 2).Footnote 124

Figure 2. Diallo and other WFTU leaders at the executive bureau meeting in Vienna, July 1951. Left to right: Lju Ning I (People’s Republic of China), Abdoulaye Diallo (French Sudan), Benoît Frachon (France), V. Lombardo Toledano (Latin America), all WFTU Vice Presidents; Louis Saillant, WFTU General Secretary.

In April 1953, the WFTU executive bureau, including Diallo, met in Vienna and announced that the Third World Congress of the WFTU would be held in Vienna from 10 to 21 October of that year. Three key agenda items were announced: 1) a report on the activities of the WFTU and other tasks of trade unions in the struggle for unity of action and peace; 2) the tasks of trade unions in the field of economic and social development and democratic rights in capitalist and colonial countries; 3) the development of the trade union movement in colonial and semi-colonial countries.Footnote 125 The conference call declared the aim “to put an end to colonial slavery, to the oppression of millions of people who yearn for freedom, progress, and national independence”.Footnote 126

Scholarship on the WFTU has rarely recognized that the WFTU’s decidedly anti-colonial stance developed as early as the late 1940s and early 1950s. Almost half of the congress was devoted to workers and trade unions in “colonial and semi-colonial” countries. The diversity and aim of achieving inclusivity beyond Europe is also represented by the list of speakers reporting on the development of trade unions in colonial and semi-colonial countries. Of the twenty-nine speakers, except for one speaker each from France, Belgium, and East Germany, as well as one white South African, it was exclusively colonized people from colonial and semi-colonial countries who shared their experiences on this world stage.Footnote 127

The 1953 Vienna congress was promoted as the largest labour congress of the time. The film Lied der Ströme, directed by Joris Ivens and produced by the East German film studio DEFA in 1954, boasted that there had “never before been such a powerful, comprehensive congress”, with representatives from five continents, seventy-nine countries, and more than eighty million workers.Footnote 128 In view of workers being automatically enlisted into unions in the Soviet Union and the state socialist countries of Eastern Europe, the self-declared membership of the attending delegations should be treated with caution. Furthermore, many delegations from Africa, Asia, and Latin America were present as observers and were not affiliated with the WFTU. Yet, for comparison: the ICFTU’s world congress in Vienna two years later hosted delegates from only fifty-two countries.Footnote 129

In his speech, Diallo lamented that Africa was the only continent still largely in the hands of colonialists. He argued that the recent successes of Asian decolonization – in particular, he praised China as a model for Africans – had led “the French, English, Belgian, Portuguese, and Spanish imperialists” to increase their rate of exploitation, citing the massacres committed by the British in Kenya and the French in Madagascar.Footnote 130 Racial discrimination was widespread “in wages, in career opportunities, in public and private life, in ‘social’ legislation”.Footnote 131 He emphasized the important role of the trade union movement in combatting these injustices, and noted that trade unions had developed rapidly across the African continent since 1945 – a trend confirmed by scholars.Footnote 132

Diallo praised the second WFTU world congress, which (as explained above) had taken place in Milan in 1949 following the withdrawal of the Western liberal-reformist trade union federations, as a turning point. With “genuine representatives of the workers of the colonial and semi-colonial countries in its leadership”, the WFTU had, in his view, made its anti-colonialist position even clearer and documented its firm determination to support the organizations representing working people in colonial countries in their struggle for freedom against oppression and exploitation.Footnote 133 According to Diallo, it was a great sign of trust by European WFTU leaders: “Although they [leaders from Africa, Asia, and Latin America] had little experience in the international trade union movement, they were at least firmly determined to work for the development of their organizations in order to put an end to the rule of injustice.”Footnote 134

Diallo’s words emphasize the WFTU’s attempts towards more inclusivity and broader geographical representation, as discussed by Reinalda (quoted above). However, while the WFTU was important in reaffirming these goals, it was Africans themselves who were responsible for defining and following the exact means to achieve freedom and prosperity, since “as the saying goes, no-one knows better than the sick person himself where he hurts and how much he hurts”.Footnote 135

Diallo played a central role at the Vienna congress. In Lied der Ströme, he is introduced to viewers as “the representative of African workers”.Footnote 136 As vice-president and a member of the WFTU executive bureau, Diallo sat on the raised platform above the hundreds of delegates in the hall, with the WFTU’s general secretary, Saillant, on his right and the president of the ACCTU, Nikolai Schvernik, on his left. Representing the WFTU leadership, Diallo was honoured to receive a large banner from the Central Labour Organization of the Republic of Indonesia (SOBRI) to celebrate the affiliation of another Indonesian national federation to the WFTU.Footnote 137 The election at the end of the congress confirmed Diallo (representing French West Africa) as one of the vice-presidents in the WFTU executive bureau.Footnote 138

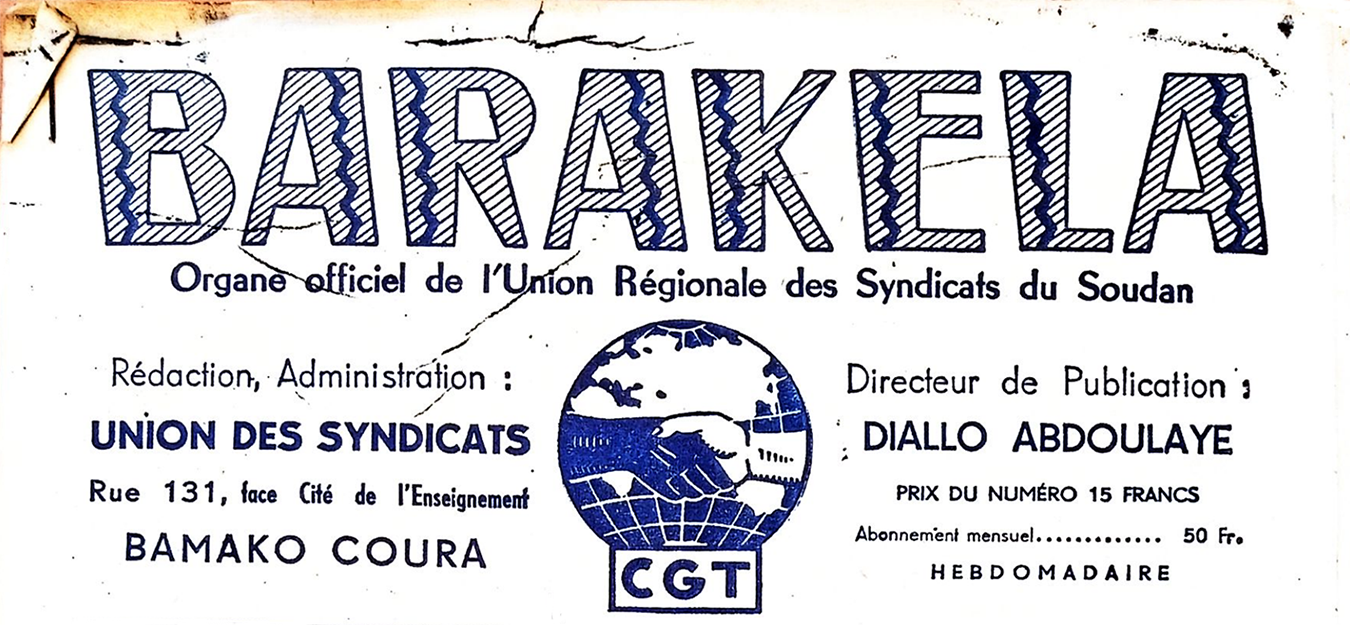

In spring 1954, at the height of his fame within the WFTU, French colonial officials were convinced that Diallo was the “most dangerous trade union agitator in French Black Africa”.Footnote 139 As general secretary of the Sudanese CGT unions and editor of the union magazine Barakela (Figure 3), Diallo had also mobilized opinion in other territories of French West Africa against low prices for farmers. In his speech to the world congress in 1953, he protested that “African peasants and plantation workers produce rice, millet, peanuts, cocoa, and coffee, but the representatives of the colonial trading companies set the prices”.Footnote 140

Figure 3. Barakela, the trade union magazine published by the French Sudanese CGT under the editorship of Abdoulaye Diallo, May 1954.

On 16 March 1954, Diallo was summoned to appear before the criminal court in Bamako, charged with “insulting and defaming the governor and the Chamber of Commerce”.Footnote 141 French and African CGT union leaders, such as Jaques N’gom, general secretary of the CGT unions in Cameroon, petitioned the judge of the upcoming trial in Bamako. N’gom emphasized Diallo’s stature:

[A] labour activist known and respected not only by French Sudanese workers, but also by workers throughout French West Africa, Cameroon, French Equatorial Africa, and all of Africa, French workers, and the international working class. He is a man who, in defence of workers’ interests, did not hesitate to sacrifice himself, his position, and his large family.Footnote 142

The anti-colonial press saw Diallo’s trial as a pretext for a wider wave of repression against the trade union movement throughout French West Africa and the trade unionists’ struggles to implement the Labour Code passed by the French parliament in 1952.Footnote 143 The WFTU leadership immediately announced that it would report the case to the UN’s ECOSOC – where Diallo himself had spoken in 1953 about the violation of trade union rights in the French colonies, as we saw earlier. Together with the CGT, the WFTU declared 16 March a day of “struggle for the defence of trade union rights and solidarity with the activists being prosecuted” and called upon “all workers and trade union organizations to demonstrate, in unity, their solidarity with African workers and one of their leaders, Abdoulaye Diallo”.Footnote 144 Workers in French Sudan followed this call and protested “en masse” for the acquittal of Diallo.Footnote 145 On Labour Day on 1 May 1954, Soviet-run newspapers in Austria celebrated the acquittal of Diallo amid “mass meetings and protest strikes”.Footnote 146 The article contained a decidedly anti-colonial report on conditions in French-ruled West Africa and the significance of the recent wave of strikes, and heroized Diallo, who had made it straight from his acquittal to Vienna in time for the meeting of the WFTU executive bureau at the end of March 1954.

Disaffiliation from the CGT and the WFTU? Dissenting Views among West African Labour Leaders

The development of a type of trade unionism in West Africa that sought to emancipate itself from the French national federations with their competing political ideologies, culminating in the creation of the autonomous pan-West African federation UGTAN in January 1957, has been thoroughly researched.Footnote 147 This section will focus on Diallo’s role in this process, showing his importance in keeping the trade unions in French Africa within the CGT and, by extension, the WFTU for as long as he deemed it possible.

Despite the French government’s repressive policy towards the CGT and the French Communist Party, by the early 1950s, more than half of all union members in French West Africa belonged to CGT-affiliated unions.Footnote 148 However, this orientation was increasingly put on the defensive by a new group of union leaders, mostly from Guinea. Following the African Democratic Assembly’s break with the French Communist Party in 1951, the Guinean unionist Touré sought greater autonomy for the African labour movement. At the CGT’s Bamako conference in 1951, Diallo managed to persuade the majority of delegates to maintain links with the metropolitan CGT and hence also with the WFTU.Footnote 149 Diallo argued that continued affiliation would bring organizational and material benefits, such as international travel, facilities and capacity for trade union education and training, office equipment, and material support, for example in the event of strikes.Footnote 150 As we saw above, at the 1953 congress in Vienna he urged African workers and unionists not to isolate their struggles from the WFTU.

However, as anti-colonial nationalist forces gained ground worldwide, the pressure on Diallo’s internationalist perspective grew. In 1955, Touré put forward his concept of an “African personality” more forcefully, arguing that African workers needed a trade union organization that was not affiliated to any of the French trade union federations and that put the nationalist anti-colonial struggle first, ahead of class struggle.Footnote 151 A new trade union organization, the CGT-Africaine,Footnote 152 was founded in January 1956, competing with the “orthodox” CGT for membership among workers. While the “orthodox” or “internationalist” leaders such as Diallo, Djibo, and Alioune Cissé managed to retain their influence, in concession to growing “autonomist” pressures they did convene an “African trade union conference to create an independent African confederation that will enable us to achieve African trade union unity”.Footnote 153 At the time, Diallo was still very much part of the WFTU leadership, so he was caught between two stools. For example, in January 1956 Diallo was part of a high-level WFTU delegation to the ILO, which met with the ILO’s director-general, David Morse.Footnote 154 Diallo’s prestige within the WFTU and his conviction that the organized labour movement in French West Africa was not “developed” enough in terms of a solid financial base, education and training, and organizational capacity explains why he “did not altogether reject a centrale that was specifically African, as long as it was linked to the international proletarian movement via the WFTU”.Footnote 155

By April 1956, the CGT-Africaine had 55,000 members, only 5,000 less than the CGT.Footnote 156 Touré used the labour movement as a “launching pad for his political career”, which required an expansion of his follower base beyond the rather small segment of salaried workers. With his emphasis on African nationalism and rejection of the class struggle, he mobilized among the rural population against all forms of foreign influence – and Marxist–Leninist internationalism of the variety represented by Diallo, as WFTU vice-president, was branded as “foreign”.Footnote 157 Diallo did not agree with Touré’s views, as he was convinced that the establishment of an autonomous trade union federation was premature given French West Africa’s relatively low grade of industrialization and small segment of salaried workers (who made up around five per cent of the workforce).Footnote 158 Because of its anti-communist strategy, the French colonial administration was determined to support Touré’s mission to break the influence of the CGT, and by extension the WFTU, on the labour movements in French West Africa.Footnote 159

The founding congress of the new autonomous African federation was held in Cotonou, Benin, from 16 to 20 January. The “orthodox” or “internationalist” leaders, such as Diallo, arrived in Cotonou without having asked to be disaffiliated from the CGT. However, after heated debates during the conference, this group was forced to disaffiliate, and Diallo symbolically sent his resignation to the CGT and WFTU. According to Philippe Dewitte, “with the last obstacles to the creation of the new union federation removed, the UGTAN was born”.Footnote 160

In January 1957, after a decade of struggle and serving as a respected ambassador of Africa’s labour movement at international labour congresses in the WFTU’s orbit and on the UN stage, Diallo stepped down as WFTU vice-president and was elected as one of the UGTAN’s general secretaries.Footnote 161 Diallo’s attention soon focused on French Sudan, as he was appointed Sudan’s Minister of Labour by Modibo Keïta in June 1957.Footnote 162 Since he was serving in this capacity and no longer had any official function within the WFTU, Diallo was not part of the UGTAN’s observer delegation to the WFTU’s fourth world congress in Leipzig in October 1957.Footnote 163 In the years that followed, he focused his energies on expanding the African trade union movement, working with Ghana’s President Kwame Nkrumah as general secretary of the All-African People’s Conference and playing a key role in the preparations for the establishment of the All-African Trade Union Federation in Casablanca in May 1961.Footnote 164 While his subsequent career as a prominent trade union leader in Guinea, diplomat in various countries, and later as an ILO official at the organization’s headquarters in Geneva deserves attention,Footnote 165 it is also worth asking what lessons we can learn from Diallo’s role as an anti-colonial trade union official and communist ambassador of labour within the CGT and WFTU from the late 1940s to 1957.

Conclusion

This article has traced Diallo’s union career trajectory from the WFTU’s 1947 Pan-African Trade Union Conference in Dakar to the establishment of the UGTAN in 1957, offering a fresh perspective on the role of African unionists in shaping international labour politics. The 1947 conference revealed both the potential and the limitations of the united WFTU. African delegates, including Diallo, used the forum to advocate for equal pay and anti-racism, and envisioned a global audience and international associations as their publics. However, “apolitical” trade unionism, overseen by officials from the metropole, limited the scope of action and reduced publicity, foreshadowing a key conflict between anti-colonial demands and Western guardianship of procedure and key positions in the united WFTU. Decentring this moment shifts the narrative from metropolitan initiative to African agenda-setting, clarifying why the colonial question became structurally unavoidable in post-war labour internationalism. This analysis complicates the established narrative centred on Marshall aid and anti-communism. Anti-colonial contention not only accompanied the rupture, but also helped organize the field of positions within which unions and states realigned.

Following the split of 1949, the reconfigured leadership of the WFTU opened up new opportunities for anti-colonial actors. Diallo’s election as vice-president signalled a shift towards greater inclusivity beyond Europe and a clearer commitment to decolonization. Through his publications, official visits, and speeches he reframed Africa’s workers as a key element of anti-imperial struggles against “Western monopolies”, insisting that inter-African cooperation should flourish within the communist world trade union movement rather than apart from it. Diallo’s trajectory shows how communist-led internationalism served as a vehicle for amplifying the voices of the colonized and elevating them to agenda-setting roles.

A close reading of Diallo’s speeches at the ECOSOC meetings in 1950 (New York) and 1953 (Geneva) demonstrates the dual role of WFTU representatives as communist labour ambassadors in the early 1950s: presenting evidence as affected witnesses from the colonies and connecting their struggles to broader anti-imperialist themes. The speeches criticized the Western colonial powers and the US, while unreservedly praising the Soviet Union. The representatives of the colonial powers and the presidents of the ECOSOC sessions repeatedly called for the debate to be narrowed and made less political, but this did not stop Diallo from sharing his perspective. The supposedly “apolitical” approach favoured by the colonial representatives was meant to prevent systemic criticism: conceptualizing forced labour, capitalist exploitation, and colonial oppression as connected and intertwined went beyond the limits of what could be said. As the intervention of the French government representative shows, there were repeated attempts to silence fierce anti-colonial, anti-capitalist criticism. Overall, this sheds light on the potential as well as the limitations of the UN as a platform for anti-colonial and anti-imperial projects. Consultative status provided WFTU representatives with visibility, while the UN Charter and the Universal Declaration of Human Rights furnished a legal-normative vocabulary that enabled criticism of forced labour and repression. However, these arenas were subject to specific conventions, such as a requirement that evidence be presented in isolation from broader aspects of society and politics. The presidents and delegates of colonial empires consistently policed the boundary between “technical” labour issues and “political” critique. This contradicted the more holistic approach of political economy and curtailed systemic arguments, as illustrated by Diallo’s case.

The WFTU’s Vienna congress (1953) promoted the federation’s efforts to open itself up to Africa, Asia, and Latin America. Although it still had a French general secretary and Italian president, eleven vice-presidents were appointed from different parts of the world. With Diallo prominent on the rostrum, nearly half of the congress’s agenda was devoted to unions from “colonial and semi-colonial countries”, and the WFTU explicitly framed decolonization as a trade union task. Recognizing Milan 1949 and Vienna 1953 as turning points sheds light on two historiographical issues. Firstly, post-World War II communist-led labour internationalism did not discover anti-colonialism belatedly; rather, the WFTU sought to give recognition to African representatives and circulate their opinions to mass audiences via newspapers and WFTU publications. Secondly, this visibility led to pushback from the colonial authorities in the French empire – the trial of Diallo in Bamako highlighted how international stature could lead to domestic repression, even as it mobilized transnational solidarity.

Ultimately, the West African debates that culminated in the UGTAN conference of 1957 redefined “internationalism” as a strategic choice rather than a fixed identity. Diallo’s decision to remain within the CGT/WFTU at several key moments during the 1950s was motivated by a desire to secure resources, training, and transcontinental leverage, whereas Touré’s autonomist approach prioritized nationalist mobilization and an expansion of the social base beyond salaried workers. A close reading of Diallo’s speeches and articles reveals that the positions they expressed were not necessarily denying the importance of Pan-African regionalism, but rather competing evaluations of timing, the local labour movement’s estimated capacity, and risk in a rapidly changing context, with colonial authorities supporting Touré’s autonomous tendencies because they wanted to reduce communist influence.

A note of caution is required. The absence of personal correspondence from this period makes it challenging to determine the degree to which Diallo’s personal beliefs aligned with his speeches and newspaper articles during his tenure as WFTU vice-president. In her work on Latin American labour leaders’ relations with the AFL, Magaly Rodríguez García has found that “a heavy dose of opportunism” was an important motive.Footnote 166 This presents a challenging question for our case study. Based on our sources and the assessments of his contemporaries, we believe that Diallo as a political individual remained a committed communist until the mid-1950s, only reluctantly agreeing to sever West African unions’ ties with the CGT and WFTU. As we have shown, the outcome in early 1957 – disaffiliation from the CGT and WFTU and the founding of the UGTAN – did not negate Diallo’s internationalism; rather, it marked a reorientation towards Pan-African labour regionalism after a decade within the communist-oriented WFTU.

Overall, Diallo’s appointment as the first African WFTU vice-president challenges our preconceived notions about the so-called “Soviet front organizations”. Trade union leaders such as Diallo leveraged the infrastructure of international organizations such as the WFTU, including travel, publishing outlets, conferences, and UN seats, to advance their own agendas and gain experience within globally active organizations.