1. Introduction

Circular-arc ribs are frequently used for enhancing turbulent transport of momentum and thermal energy for turbine blade cooling and heat exchangers. In this class of flows, periodically spaced ribs give rise to large flow separation regions that are sensitive to not only the surface curvature of the arc but also the pitch-to-height ratio of the ribs. Turbulent motions are inhomogeneous along the streamwise and vertical directions, featuring coherent vortices with various spatial and temporal scales. These physical features greatly complicate the turbulence energy transport processes associated with eddy motions of different scales, making the characteristic length scales of the turbulence structures fundamentally different from those of a smooth-wall plane-channel flow (Kim, Moin & Moser Reference Kim, Moin and Moser1987; Hoyas & Jiménez Reference Hoyas and Jiménez2006). The presence of transverse ribs typically triggers a strong internal shear layer (ISL) around the rib height and induces a large separation bubble on the lee of a rib (Leonardi et al. Reference Leonardi, Orlandi, Djenidi and Antonia2004; Ikeda & Durbin Reference Ikeda and Durbin2007; MacDonald et al. Reference MacDonald, Ooi, García-Mayoral, H. and Chung2018). The ISL features strong shear stresses and large mean velocity gradients, which further lead to an enhanced turbulent-production rate and high levels of turbulence kinetic energy (TKE). The presence of ISL is a characteristic of turbulent flows over a ribbed surface, and a thorough understanding of the energy transport processes across the ISL is critical for understanding the rib effects on the flow dynamics and structures.

1.1. Rib effects on turbulent motions

Turbulent flows over ribs have been investigated intensively through experimental and numerical studies in the current literature. For instance, Djenidi, Elavarasan & Antonia (Reference Djenidi, Elavarasan and Antonia1999) measured a turbulent boundary-layer flow over transverse square bars and cavities using laser-induced fluorescence (LIF) and a laser Doppler velocimeter (LDV), and observed a local maximum of Reynolds shear stress near the rib height. Volino et al. (Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2007, Reference Volino, Schultz and Flack2009) conducted water-channel experiments to compare zero-pressure-gradient (ZPG) boundary-layer flows over flat plates roughened with a wire mesh or transverse square bars using a LDV. They found that the characteristic scales of turbulence structures induced by transverse square bars were much larger than those induced by a wire mesh. Leonardi et al. (Reference Leonardi, Orlandi, Djenidi and Antonia2004) conducted direct numerical simulations (DNS) of a fully developed two-dimensional (2-D) turbulent channel flow over transverse square ribs mounted on one wall. They concluded that the coherency of streaky structures became decreased in the streamwise direction at a high pitch-to-height ratio as a result of flow ejections from cavities. Burattini et al. (Reference Burattini, Leonardi, Orlandi and Antonia2008) investigated turbulent channel flows over transverse square ribs using both hot-wire anemometers and DNS, and observed that the profiles of Reynolds normal stresses on the ribbed-wall side were almost independent of the Reynolds number when scaled by the outer coordinate of a turbulent boundary layer. Leonardi et al. (Reference Leonardi, Orlandi, Djenidi and Antonia2015) conducted DNS of a turbulent channel flow with square bars placed on one wall. By examining the spatial two-point auto-correlations of velocity fluctuations, they observed that the maximum streamwise scale of turbulence structures was 2.5 times the rib height. Lee, Kim & Lee (Reference Lee, Kim and Lee2016) conducted DNS of a turbulent boundary layer over square ribs, and observed that adjacent long flow structures often combined to form a longer structure through a spanwise merging process near the ribbed wall.

1.2. Physical analysis of TKE transport processes in rib-roughened flows

Owing to the disturbances from the ribs, turbulent flows become highly anisotropic in the separation and reattachment regions, which significantly complicates the transport process of TKE and leads to a great challenge for turbulence modelling of such flows. Accordingly, there are many reported experimental and numerical investigations into the transport equations of Reynolds stresses of turbulent flows over ribs, well presented by the works of Hirota, Ykosawa & Fujita (Reference Hirota, Ykosawa and Fujita1992), Nagano, Hattori & Houra (Reference Nagano, Hattori and Houra2004), Ikeda & Durbin (Reference Ikeda and Durbin2007) and Burattini et al. (Reference Burattini, Leonardi, Orlandi and Antonia2008). For instance, Nagano et al. (Reference Nagano, Hattori and Houra2004) conducted DNS of turbulent channel flows over transverse rectangular ribs. Based on an analysis of the budget balance of TKE, they observed that the turbulence production was trivial in the inter-rib region between two adjacent ribs where the TKE was maintained primarily by the turbulent-diffusion term. Ikeda & Durbin (Reference Ikeda and Durbin2007) performed DNS of turbulent channel flows with transverse square ribs placed on one wall, and observed a strong turbulence production rate of TKE slightly above the rib crest.

Clearly, the complex turbulence energy transport process under the rib effects involves energetic eddies of various characteristic length scales, which are also sensitive to the flow and geometry parameters such as the Reynolds number, blockage ratio and pitch-to-height ratio. It should be indicated that the previous studies of the budget balance of the transport equations of TKE and Reynolds stresses in ribbed channel or duct flows reviewed were conducted exclusively in the physical space. To develop a deeper understanding of the problem, the TKE transport process associated with turbulent motions of varying length scales can be further studied through the transport equation of Reynolds stresses in the spectral space, which is useful for precisely identifying the characteristic length scales of turbulence structures and understanding the TKE cascade across wavelengths.

1.3. Spectral analysis of TKE transport processes in smooth-wall flows

In his pioneering work, Lumley (Reference Lumley1964) derived the spectral energy equation to study the budget balance of TKE in the spectral space in the context of wall turbulence. Aulery et al. (Reference Aulery, Toutant, Bataille and Zhou2015, Reference Aulery, Dupuy, Toutant, Bataille and Zhou2017) performed spectral analysis of the TKE transport process in plane-channel flows, and observed the inverse energy cascade of TKE to turbulent motions with characteristic scales larger than the channel height. Mizuno (Reference Mizuno2016) conducted DNS of a plane-channel flow to study the transport of TKE in the spectral space, and observed that the dominant structures of different wavelengths were self-similar in the energy transport process. Lee & Moser (Reference Lee and Moser2019) conducted a spectral analysis of the budget balance of Reynolds stresses using DNS data of turbulent plane-channel flows, and observed that the large-scale streamwise-elongated flow structures played a significant role in the energy transport process. It should be indicated that the spectral studies of TKE transport processes have been limited to boundary-layer flows developing over smooth walls of simple domain geometry such as turbulent plane-channel flows. Spectral analysis of turbulent transport of TKE and Reynolds stresses in the context of ribbed-channel flows is still absent in the current literature.

1.4. Objectives

Notwithstanding the contributions of the remarkable works reviewed, it is noted that the number of studies on spectral analysis of turbulent energy transport processes is still relatively limited in the current literature, focusing exclusively on DNS of smooth-wall flows (Mizuno Reference Mizuno2016; Lee & Moser Reference Lee and Moser2019; Yang et al. Reference Yang, Deng, Wang and Shen2020) over the recent decade. Thus far, no high-fidelity DNS study on transport of Reynolds stresses and TKE in the spectral space has been reported in the context of a ribbed boundary-layer flow. In view of this knowledge gap, we aim at performing a comprehensive spectral analysis of the budget balance of the TKE transport equation based on high-fidelity DNS data of turbulent channel flows with circular-arc ribs mounted on one wall. This study focuses on the rib effects on the characteristic scales of the turbulent motions and structures. The present study is also a natural extension of our recent work (Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Xu, Wang and Mahmoodi-Jezeh2023) from a physical-space study to a spectral-space study on the turbulent flows in ribbed channels.

The remainder of this paper is organised as follows. In § 2, the test cases and numerical algorithm for performing DNS are introduced. Grid resolutions are also described in this section. In § 3, the main flow patterns are demonstrated and analysed briefly to present an overview of the physical features of this type of ribbed-channel flow. In § 4, the rib effects on the characteristic spanwise scales of turbulent structures are studied using the two-point auto-correlation coefficients and premultiplied energy spectra of TKE. In § 5, the energy transport processes of TKE at different spanwise scales are examined in detail through investigations into the distributions of the premultiplied budget terms of TKE in both physical and spectral spaces. In § 6, major findings and conclusions of this research are summarised.

2. Test cases and numerical algorithm

Figure 1 shows the schematic diagram of the computational domain of the ribbed channel and the coordinate system. Here,

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

and

$y$

and

![]() $z$

denote the streamwise, vertical and spanwise coordinates, respectively. The flow goes through the channel bounded by a top smooth wall and a bottom ribbed wall. The streamwise and spanwise domain sizes are set to

$z$

denote the streamwise, vertical and spanwise coordinates, respectively. The flow goes through the channel bounded by a top smooth wall and a bottom ribbed wall. The streamwise and spanwise domain sizes are set to

![]() $L_x=12\delta$

and

$L_x=12\delta$

and

![]() $L_z=2\pi \delta$

, respectively, where

$L_z=2\pi \delta$

, respectively, where

![]() $\delta =L_y/2$

is the half-channel height. The pitch and height of the circular-arc ribs are

$\delta =L_y/2$

is the half-channel height. The pitch and height of the circular-arc ribs are

![]() $P$

and

$P$

and

![]() $H$

, respectively.

$H$

, respectively.

Figure 1. Schematic diagram of the computational domain and coordinate system. The origin of the absolute coordinate system

![]() $[x,y,z]$

is located at the inner bottom corner of the inlet, and the origin of the relative streamwise coordinate

$[x,y,z]$

is located at the inner bottom corner of the inlet, and the origin of the relative streamwise coordinate

![]() $x'$

is located at the windward face of each rib, which is defined to facilitate the analysis within a rib period.

$x'$

is located at the windward face of each rib, which is defined to facilitate the analysis within a rib period.

Four test cases (P1, P2, P3 and P3R) of ribbed-channel flows and two smooth-channel-flow cases (SC and SCR) are considered in our comparative study. The design of these six test cases is not arbitrary, which facilitates a comparative study of rib effects on the flow field under the influences of two parameters, i.e. the pitch-to-height ratio (

![]() $P/H$

) and Reynolds number. In the four ribbed-channel-flow cases, the radius of the rib arc is kept constant, i.e.

$P/H$

) and Reynolds number. In the four ribbed-channel-flow cases, the radius of the rib arc is kept constant, i.e.

![]() $R=H=0.2\delta$

. Cases P1, P2 and P3 are compared to investigate the effects of the pitch-to-height ratio (of

$R=H=0.2\delta$

. Cases P1, P2 and P3 are compared to investigate the effects of the pitch-to-height ratio (of

![]() $P/H=3.0$

, 5.0 and 7.5, respectively) on the flow field based on a common blockage ratio of

$P/H=3.0$

, 5.0 and 7.5, respectively) on the flow field based on a common blockage ratio of

![]() ${\textit{Br}}=H/2\delta =0.1$

. The nominal Reynolds number is fixed at

${\textit{Br}}=H/2\delta =0.1$

. The nominal Reynolds number is fixed at

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=2\delta U_b/\nu =5600$

in cases P1, P2 and P3 to maintain a constant mass flow rate, where

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=2\delta U_b/\nu =5600$

in cases P1, P2 and P3 to maintain a constant mass flow rate, where

![]() $U_b$

denotes the bulk mean streamwise velocity at the inlet of the channel and

$U_b$

denotes the bulk mean streamwise velocity at the inlet of the channel and

![]() $\nu$

denotes the kinematic viscosity of the fluid. In addition, the Reynolds number effect on the ribbed turbulent channel flow is examined by including case P3R, which shares the same geometry as case P3, but has a moderately high nominal Reynolds number of

$\nu$

denotes the kinematic viscosity of the fluid. In addition, the Reynolds number effect on the ribbed turbulent channel flow is examined by including case P3R, which shares the same geometry as case P3, but has a moderately high nominal Reynolds number of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=14\,600$

. Given the fixed domain size, cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R consist of 20, 12, 8 and 8 periods, respectively. In order to identify the rib effects, two additional cases of smooth-channel flows of different nominal Reynolds numbers (

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=14\,600$

. Given the fixed domain size, cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R consist of 20, 12, 8 and 8 periods, respectively. In order to identify the rib effects, two additional cases of smooth-channel flows of different nominal Reynolds numbers (

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

for case SC and 14 600 for case SCR) have been considered. The choice of the lower Reynolds number of

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

for case SC and 14 600 for case SCR) have been considered. The choice of the lower Reynolds number of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

follows the classical work of Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Moin and Moser1987), who pioneered the DNS study of turbulent plane-channel flows. The flow field is fully developed, and periodic boundary conditions are applied in the streamwise and spanwise directions. A no-slip boundary condition is imposed on all solid surfaces.

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

follows the classical work of Kim et al. (Reference Kim, Moin and Moser1987), who pioneered the DNS study of turbulent plane-channel flows. The flow field is fully developed, and periodic boundary conditions are applied in the streamwise and spanwise directions. A no-slip boundary condition is imposed on all solid surfaces.

The continuity and momentum equations that govern the motion of an incompressible flow are written as

where

![]() $u_i$

,

$u_i$

,

![]() $\rho$

,

$\rho$

,

![]() $p$

and

$p$

and

![]() $\delta _{\textit{ij}}$

represent the velocity, density, pressure, and Kronecker delta, respectively. In addition,

$\delta _{\textit{ij}}$

represent the velocity, density, pressure, and Kronecker delta, respectively. In addition,

![]() $\varPi$

is an imposed constant mean streamwise pressure gradient that drives the flow. Tensor notation is used in governing equations (2.1) and (2.2) with which the streamwise, vertical and spanwise coordinates are denoted as

$\varPi$

is an imposed constant mean streamwise pressure gradient that drives the flow. Tensor notation is used in governing equations (2.1) and (2.2) with which the streamwise, vertical and spanwise coordinates are denoted as

![]() $x_i$

for

$x_i$

for

![]() $i=1$

, 2 and 3, respectively. Correspondingly, the velocity components

$i=1$

, 2 and 3, respectively. Correspondingly, the velocity components

![]() $u$

,

$u$

,

![]() $v$

and

$v$

and

![]() $w$

are denoted using

$w$

are denoted using

![]() $u_1$

,

$u_1$

,

![]() $u_2$

and

$u_2$

and

![]() $u_3$

, respectively. To make it convenient for statistical analysis of the flow field within a repeated rib period, a relative streamwise coordinate

$u_3$

, respectively. To make it convenient for statistical analysis of the flow field within a repeated rib period, a relative streamwise coordinate

![]() $x'$

is defined with its origin located at the windward corner of each rib as shown in figure 1.

$x'$

is defined with its origin located at the windward corner of each rib as shown in figure 1.

The DNS is performed using a spectral-element code so-called ‘Semtex’ contributed by Blackburn & Sherwin (Reference Blackburn and Sherwin2004). This code is developed using C++ and FORTRAN programming languages, and parallelised using message passing interface (MPI) libraries. A second-order time-splitting scheme with three substeps developed by Karniadakis, Israeli & Orszag (Reference Karniadakis, Israeli and Orszag1991) is used for time integration. Specifically, an intermediate velocity is obtained in the first substep by advancing the convection and body-force (

![]() $\varPi$

) terms using a second-order backward time-differencing scheme. Subsequently, the intermediate velocity is used in the second time substep to determine the pressure field in order to satisfy the continuity equation. In the third substep, the viscous term of the momentum equation is implicitly integrated with the prescribed boundary conditions. The last two time substeps rely on solving the 2-D Helmholtz equations in the spectral space based on a static condensation technique introduced by Karniadakis & Sherwin (Reference Karniadakis and Sherwin2005).

$\varPi$

) terms using a second-order backward time-differencing scheme. Subsequently, the intermediate velocity is used in the second time substep to determine the pressure field in order to satisfy the continuity equation. In the third substep, the viscous term of the momentum equation is implicitly integrated with the prescribed boundary conditions. The last two time substeps rely on solving the 2-D Helmholtz equations in the spectral space based on a static condensation technique introduced by Karniadakis & Sherwin (Reference Karniadakis and Sherwin2005).

Quadrilateral spectral-elements are used for discretisation in the streamwise and vertical directions. The mesh for the finite-element nodes was determined by solving an elliptic partial differential equation following the approach of Thompson, Frank & Mastin (Reference Thompson, Frank and Mastin1977). In each finite element in the

![]() $x$

-

$x$

-

![]() $y$

plane, a fourth-order Gauss–Lobatto–Legendre Lagrange (GLLL) polynomial was used for further interpolation of flow variables. To demonstrate, figure 2 shows a partial mesh used for performing DNS of case P3. Given that the GLLL polynomial interpolants are non-uniform within each finite element, the mesh is non-uniform in figure 2. Further using case P3 as the example, there are 15 360 (

$y$

plane, a fourth-order Gauss–Lobatto–Legendre Lagrange (GLLL) polynomial was used for further interpolation of flow variables. To demonstrate, figure 2 shows a partial mesh used for performing DNS of case P3. Given that the GLLL polynomial interpolants are non-uniform within each finite element, the mesh is non-uniform in figure 2. Further using case P3 as the example, there are 15 360 (

![]() $384\times40$

) quadrilateral-structural elements over the

$384\times40$

) quadrilateral-structural elements over the

![]() $x$

-

$x$

-

![]() $y$

plane. In each finite element, there are

$y$

plane. In each finite element, there are

![]() $5\times 5$

GLLL points, and so there are 247 457 (i.e.

$5\times 5$

GLLL points, and so there are 247 457 (i.e.

![]() $N_x\times N_y=1537\times 161$

) GLLL points in the

$N_x\times N_y=1537\times 161$

) GLLL points in the

![]() $x$

-

$x$

-

![]() $y$

plane (overlapped points on the shared edges of adjacent elements are excluded). In the spanwise (

$y$

plane (overlapped points on the shared edges of adjacent elements are excluded). In the spanwise (

![]() $z$

) direction, all physical quantities are expanded into Fourier series in the spectral space. In total, the number of Fourier modes

$z$

) direction, all physical quantities are expanded into Fourier series in the spectral space. In total, the number of Fourier modes

![]() $N_z$

used is 160 in case SC, 240 in cases P1, P2 and P3, 320 in case SCR, and 512 in case P3R. Table 1 summarises the grid resolutions of all six test cases, where

$N_z$

used is 160 in case SC, 240 in cases P1, P2 and P3, 320 in case SCR, and 512 in case P3R. Table 1 summarises the grid resolutions of all six test cases, where

![]() $(\boldsymbol{\cdot })_s^+$

is a quantity scaled by wall units based on the friction velocity of the top smooth wall

$(\boldsymbol{\cdot })_s^+$

is a quantity scaled by wall units based on the friction velocity of the top smooth wall

![]() $u_{\tau S}$

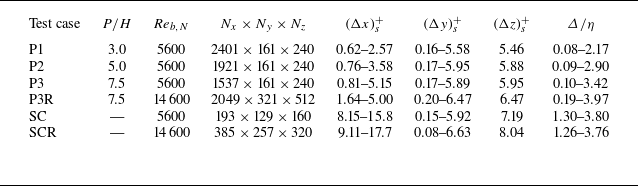

. The mesh is refined near all solid surfaces. As seen in table 1, for the four ribbed test cases, the grid resolutions along the streamwise, vertical and spanwise directions vary within

$u_{\tau S}$

. The mesh is refined near all solid surfaces. As seen in table 1, for the four ribbed test cases, the grid resolutions along the streamwise, vertical and spanwise directions vary within

![]() $0.62\leqslant (\Delta x)^+_s\leqslant 5.15$

,

$0.62\leqslant (\Delta x)^+_s\leqslant 5.15$

,

![]() $0.16\leqslant (\Delta y)^+_s\leqslant 6.47$

and

$0.16\leqslant (\Delta y)^+_s\leqslant 6.47$

and

![]() $5.46\leqslant (\Delta z)^+_s\leqslant 6.47$

, respectively. For the two smooth-channel-flow cases, the grid resolutions are similar to those used by Moser, Kim & Mansour (Reference Moser, Kim and Mansour1999). To satisfy the demanding requirement of DNS on grid resolutions, the ratio of the grid size over the Kolmogorov scale

$5.46\leqslant (\Delta z)^+_s\leqslant 6.47$

, respectively. For the two smooth-channel-flow cases, the grid resolutions are similar to those used by Moser, Kim & Mansour (Reference Moser, Kim and Mansour1999). To satisfy the demanding requirement of DNS on grid resolutions, the ratio of the grid size over the Kolmogorov scale

![]() $\eta$

is given in table 1, which varies within range

$\eta$

is given in table 1, which varies within range

![]() $0.08\leqslant \varDelta /\eta \leqslant 3.97$

in all six test cases. Here, the averaged grid size

$0.08\leqslant \varDelta /\eta \leqslant 3.97$

in all six test cases. Here, the averaged grid size

![]() $\varDelta$

and Kolmogorov length scale

$\varDelta$

and Kolmogorov length scale

![]() $\eta$

are calculated as

$\eta$

are calculated as

![]() $\varDelta =\sqrt [3]{\varDelta _x\varDelta _y\varDelta _z}$

and

$\varDelta =\sqrt [3]{\varDelta _x\varDelta _y\varDelta _z}$

and

![]() $\eta = (\nu ^3/\varepsilon _k)^{1/4}$

, respectively, and

$\eta = (\nu ^3/\varepsilon _k)^{1/4}$

, respectively, and

![]() $\varepsilon _k$

is the local dissipation rate defined as

$\varepsilon _k$

is the local dissipation rate defined as

![]() $\varepsilon _k=\nu \langle ({\partial u^{\prime}_i}/{\partial x_{\!j}})({\partial u^{\prime}_i}/{\partial x_{\!j}})\rangle$

. Symbol

$\varepsilon _k=\nu \langle ({\partial u^{\prime}_i}/{\partial x_{\!j}})({\partial u^{\prime}_i}/{\partial x_{\!j}})\rangle$

. Symbol

![]() $\langle\cdot\rangle$

denotes averaging over time and the homogeneous spanwise direction, and, additionally, over all rib periods (in the ribbed-channel-flow cases) or over the homogeneous streamwise direction (in the smooth-channel-flow cases). In turbulence decomposition,

$\langle\cdot\rangle$

denotes averaging over time and the homogeneous spanwise direction, and, additionally, over all rib periods (in the ribbed-channel-flow cases) or over the homogeneous streamwise direction (in the smooth-channel-flow cases). In turbulence decomposition,

![]() $(\cdot)'$

denotes an instantaneous fluctuation with respect to the averaged value, i.e.

$(\cdot)'$

denotes an instantaneous fluctuation with respect to the averaged value, i.e.

![]() $(\cdot)'=(\cdot)-\langle\cdot\rangle$

. Overall, the discrete solution to the governing equations based on the Semtex code is highly accurate, and the DNS results are of a spectral accuracy. The computer code has been used by our group for conducting DNS studies of rotating elliptical pipe flows (Rosas, Zhang & Wang Reference Rosas, Zhang and Wang2021), rotating and non-rotating circular pipe flows (Zhang & Wang Reference Zhang and Wang2019, Reference Zhang and Wang2024), spanwise-rotating turbulent square duct flows (Fang et al. Reference Fang, Yang, Wang and Bergstrom2017), and turbulent channel flow and heat convection with circular-arc ribs mounted on one wall (Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Xu, Wang and Mahmoodi-Jezeh2023, Reference Xiong, Xu, Wang and Mahmoodi-Jezeh2024).

$(\cdot)'=(\cdot)-\langle\cdot\rangle$

. Overall, the discrete solution to the governing equations based on the Semtex code is highly accurate, and the DNS results are of a spectral accuracy. The computer code has been used by our group for conducting DNS studies of rotating elliptical pipe flows (Rosas, Zhang & Wang Reference Rosas, Zhang and Wang2021), rotating and non-rotating circular pipe flows (Zhang & Wang Reference Zhang and Wang2019, Reference Zhang and Wang2024), spanwise-rotating turbulent square duct flows (Fang et al. Reference Fang, Yang, Wang and Bergstrom2017), and turbulent channel flow and heat convection with circular-arc ribs mounted on one wall (Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Xu, Wang and Mahmoodi-Jezeh2023, Reference Xiong, Xu, Wang and Mahmoodi-Jezeh2024).

Figure 2. Partial mesh of finite elements for case P3 in a streamwise-vertical (

![]() $x$

-

$x$

-

![]() $y$

) plane. For clarity, only two rib periods of the mesh are shown. Over the entire

$y$

) plane. For clarity, only two rib periods of the mesh are shown. Over the entire

![]() $x$

-

$x$

-

![]() $y$

plane, there are 15 360 finite elements with each element further discretised using a 4th-order GLLL polynomial (shown as blue mesh in the inset). In the spanwise (

$y$

plane, there are 15 360 finite elements with each element further discretised using a 4th-order GLLL polynomial (shown as blue mesh in the inset). In the spanwise (

![]() $z$

) direction (not shown), Fourier expansion of 240 modes is used for spatial discretisation.

$z$

) direction (not shown), Fourier expansion of 240 modes is used for spatial discretisation.

Table 1. Summary of six test cases and grid resolutions. The wall units are defined based on the friction velocity of the top smooth wall

![]() $u_{\tau S}$

.

$u_{\tau S}$

.

For each simulated case, 600 instantaneous flow fields over 35 large-eddy turnover times (LETOTs, defined as

![]() $\delta /u_{\tau R}$

) were used for collecting statistics once the flow became fully developed and statistically stationary after a precursor simulation. Here,

$\delta /u_{\tau R}$

) were used for collecting statistics once the flow became fully developed and statistically stationary after a precursor simulation. Here,

![]() $u_{\tau R}$

denotes the average friction velocity over the bottom ribbed wall. The simulations were conducted using the GREX supercomputers located at the University of Manitoba, Canada. Approximately 20 TB of data have been generated for the six simulated cases. For each test case of the ribbed-channel flow, approximately

$u_{\tau R}$

denotes the average friction velocity over the bottom ribbed wall. The simulations were conducted using the GREX supercomputers located at the University of Manitoba, Canada. Approximately 20 TB of data have been generated for the six simulated cases. For each test case of the ribbed-channel flow, approximately

![]() $20\,0000$

CPU hours were spent for solving the velocity field and for collecting the flow statistics.

$20\,0000$

CPU hours were spent for solving the velocity field and for collecting the flow statistics.

3. Key characteristics and parameters of the flow

In this section, key features of turbulent channel flows over circular-arc ribs are described briefly in the physical space, which are fundamental for the follow-up spectral analysis of turbulent motions and energy transport processes. The mean flow structures of the four ribbed cases are shown in figure 3 based on the streamlines and contours of TKE (defined as

![]() $k=\langle u_i^{\prime}u_i^{\prime}\rangle /2$

) non-dimensionalised by

$k=\langle u_i^{\prime}u_i^{\prime}\rangle /2$

) non-dimensionalised by

![]() $U_b^2$

. Strictly speaking, the relative streamwise coordinate resets (

$U_b^2$

. Strictly speaking, the relative streamwise coordinate resets (

![]() $x'= 0$

) at the windward corner of each rib, and reaches its maximum value of

$x'= 0$

) at the windward corner of each rib, and reaches its maximum value of

![]() $x'= P$

at the windward corner of the next (downstream) rib. To facilitate a direct comparison of the mean flow patterns of the four different ribbed-channel-flow cases over the same streamwise domain length, the value of

$x'= P$

at the windward corner of the next (downstream) rib. To facilitate a direct comparison of the mean flow patterns of the four different ribbed-channel-flow cases over the same streamwise domain length, the value of

![]() $x'/\delta$

is allowed to extend continuously and scales identically in figure 3(a–d). A similar method is used for displaying the contour plots of spectral budget terms later in § 5.

$x'/\delta$

is allowed to extend continuously and scales identically in figure 3(a–d). A similar method is used for displaying the contour plots of spectral budget terms later in § 5.

Figure 3. Mean streamlines with contours of non-dimensional TKE

![]() $k/U_b^2$

for all four ribbed cases. Panels (a)–(d) correspond to cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R, respectively. The dot-dashed line demarcates the isopleth of

$k/U_b^2$

for all four ribbed cases. Panels (a)–(d) correspond to cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R, respectively. The dot-dashed line demarcates the isopleth of

![]() $k=0.9\max (k)$

for each case. The red dashed line demarcates the isopleth of

$k=0.9\max (k)$

for each case. The red dashed line demarcates the isopleth of

![]() $\langle u\rangle =0$

.

$\langle u\rangle =0$

.

From figure 3, it is seen that the mean flow detaches and reattaches on the circular-arc ribs. At the detachment (D) and reattachment (R) points, the local mean wall shear stress vanishes . In the four ribbed-channel-flow cases, the streamwise position of the detachment point D occurs on the rib leeward surface at

![]() $x'\!_D/\delta =0.278$

, 0.276, 0.263 and 0.251, while the reattachment point R occurs on the rib windward surface at

$x'\!_D/\delta =0.278$

, 0.276, 0.263 and 0.251, while the reattachment point R occurs on the rib windward surface at

![]() $x'\!_R/\delta =0.083$

, 0.046, 0.014 and 0.014 for cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R, respectively. The characteristic mean flow vortices are marked with A, B and C, which represent the large recirculation bubbles behind the ribs (A), and the small secondary vortices located at the corners of the leeward and windward sides of the ribs (B and C, respectively). Due to the geometric constraints, recirculation bubble A expands with an increasing value of

$x'\!_R/\delta =0.083$

, 0.046, 0.014 and 0.014 for cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R, respectively. The characteristic mean flow vortices are marked with A, B and C, which represent the large recirculation bubbles behind the ribs (A), and the small secondary vortices located at the corners of the leeward and windward sides of the ribs (B and C, respectively). Due to the geometric constraints, recirculation bubble A expands with an increasing value of

![]() $P/H$

, which leads to a reduction in the viscous friction drag on the ribbed wall (as a result of the extension of the reverse flow region). Simultaneously, the secondary corner vortices B and C tend to grow in size as the rib pitch

$P/H$

, which leads to a reduction in the viscous friction drag on the ribbed wall (as a result of the extension of the reverse flow region). Simultaneously, the secondary corner vortices B and C tend to grow in size as the rib pitch

![]() $P$

increases. According to Perry, Schofield & Joubert (Reference Perry, Schofield and Joubert1969), Bandyopadhyay (Reference Bandyopadhyay1987) and Jiménez (Reference Jiménez2004), the type of roughness of a ribbed wall typically switches from a

$P$

increases. According to Perry, Schofield & Joubert (Reference Perry, Schofield and Joubert1969), Bandyopadhyay (Reference Bandyopadhyay1987) and Jiménez (Reference Jiménez2004), the type of roughness of a ribbed wall typically switches from a

![]() $k$

- to a

$k$

- to a

![]() $d$

-type when the gap-to-height ratio becomes less than three (i.e.

$d$

-type when the gap-to-height ratio becomes less than three (i.e.

![]() $W/H\leqslant 3$

, where

$W/H\leqslant 3$

, where

![]() $W=P-2R$

is the width of the gap between two adjacent ribs). In cases P1 and P2 (

$W=P-2R$

is the width of the gap between two adjacent ribs). In cases P1 and P2 (

![]() $W/H=1.0$

and 3.0, respectively), the mean flow skims over the ribs and the large recirculation bubble fills the whole cavity between two adjacent ribs, which is typical of a

$W/H=1.0$

and 3.0, respectively), the mean flow skims over the ribs and the large recirculation bubble fills the whole cavity between two adjacent ribs, which is typical of a

![]() $d$

-type rough-wall flow. By contrast, in cases P3 and P3R (

$d$

-type rough-wall flow. By contrast, in cases P3 and P3R (

![]() $W/H=5.5$

), the mean flow patterns are typical of a

$W/H=5.5$

), the mean flow patterns are typical of a

![]() $k$

-type rough-wall flow, with the outermost mean streamline of recirculation bubble A (initiated from upstream rib crest) reattaching on the bottom wall at approximately

$k$

-type rough-wall flow, with the outermost mean streamline of recirculation bubble A (initiated from upstream rib crest) reattaching on the bottom wall at approximately

![]() $x'/\delta =1.25$

in the interval between two adjacent ribs.

$x'/\delta =1.25$

in the interval between two adjacent ribs.

Due to the flow separation induced by ribs, a strong ISL is generated slightly above recirculation bubble A around the rib height, featuring a strong mean velocity gradient

![]() $\partial \langle u\rangle /\partial y$

(Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Xu, Wang and Mahmoodi-Jezeh2023). The strong shear of the mean flow is typically associated with an intensive production of TKE in turbulent flows, further leading to a high level of TKE. The contours of TKE in figure 3 show that turbulent motions are enhanced dramatically in the ISL. Specifically, for all four ribbed cases, the magnitude of TKE in the ISL can be over 90 % of its maximum at the midspan between two adjacent ribs (

$\partial \langle u\rangle /\partial y$

(Xiong et al. Reference Xiong, Xu, Wang and Mahmoodi-Jezeh2023). The strong shear of the mean flow is typically associated with an intensive production of TKE in turbulent flows, further leading to a high level of TKE. The contours of TKE in figure 3 show that turbulent motions are enhanced dramatically in the ISL. Specifically, for all four ribbed cases, the magnitude of TKE in the ISL can be over 90 % of its maximum at the midspan between two adjacent ribs (

![]() $x'/\delta =0.5$

, 0.7, 0.95 and 0.95 for cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R, respectively). Figure 4 further compares the vertical profiles of TKE at the rib centre (

$x'/\delta =0.5$

, 0.7, 0.95 and 0.95 for cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R, respectively). Figure 4 further compares the vertical profiles of TKE at the rib centre (

![]() $x'/\delta =0.2$

), at the rib leeward (

$x'/\delta =0.2$

), at the rib leeward (

![]() $x'/\delta =0.4$

) and at the midspan between two adjacent ribs. As shown in figure 4, it is evident that turbulent motions near the ribbed bottom wall enhance drastically compared with those in smooth-channel flows, and the TKE magnitude increases monotonically as the value of

$x'/\delta =0.4$

) and at the midspan between two adjacent ribs. As shown in figure 4, it is evident that turbulent motions near the ribbed bottom wall enhance drastically compared with those in smooth-channel flows, and the TKE magnitude increases monotonically as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases. From figures 3 and 4, it is interesting to observe that both the mean flow structures and profile of the non-dimensional TKE

$P/H$

increases. From figures 3 and 4, it is interesting to observe that both the mean flow structures and profile of the non-dimensional TKE

![]() $k/U_b^2$

of case P3R are qualitatively similar to those of case P3, showing an independence of

$k/U_b^2$

of case P3R are qualitatively similar to those of case P3, showing an independence of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_b$

which is consistent with the observation of Burattini et al. (Reference Burattini, Leonardi, Orlandi and Antonia2008) in their DNS study of turbulent plane-channel flows with transverse square ribs placed on one wall. Among these three streamwise positions, it is apparent that TKE reaches its highest level at the midspan between two adjacent ribs in all four ribbed cases. In view of this, in the remainder of our analysis, we pay close attention to this special streamwise position (

${\textit{Re}}_b$

which is consistent with the observation of Burattini et al. (Reference Burattini, Leonardi, Orlandi and Antonia2008) in their DNS study of turbulent plane-channel flows with transverse square ribs placed on one wall. Among these three streamwise positions, it is apparent that TKE reaches its highest level at the midspan between two adjacent ribs in all four ribbed cases. In view of this, in the remainder of our analysis, we pay close attention to this special streamwise position (

![]() $x'/\delta =0.5$

, 0.7, 0.95 and 0.95 for cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R, respectively) in our investigation into the characteristics of the most energetic turbulence structures.

$x'/\delta =0.5$

, 0.7, 0.95 and 0.95 for cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R, respectively) in our investigation into the characteristics of the most energetic turbulence structures.

Figure 4. Vertical profiles of non-dimensional TKE at the rib centre (

![]() $x'/\delta =0.2$

), the rib leeward corner (

$x'/\delta =0.2$

), the rib leeward corner (

![]() $x'/\delta =0.4$

) and the midspan between two adjacent ribs (

$x'/\delta =0.4$

) and the midspan between two adjacent ribs (

![]() $x'/\delta =0.5$

, 0.7, 0.95 and 0.95 for cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R, respectively). The vertical pink dashed line demarcates the rib top.

$x'/\delta =0.5$

, 0.7, 0.95 and 0.95 for cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R, respectively). The vertical pink dashed line demarcates the rib top.

Figure 5 further compares the vertical profiles of three normal components of the Reynolds stress tensor at the midspan between two adjacent ribs. As shown in figure 5, the dominance of

![]() $\langle u'u'\rangle$

among these three normal stress components is evident in both smooth and ribbed flows. For the smooth-channel flow, the peak of

$\langle u'u'\rangle$

among these three normal stress components is evident in both smooth and ribbed flows. For the smooth-channel flow, the peak of

![]() $\langle u'u'\rangle$

occurs approximately at

$\langle u'u'\rangle$

occurs approximately at

![]() $y^+=15$

(or at

$y^+=15$

(or at

![]() $y/\delta =0.079$

and 0.036 for cases SC and SCR, respectively) in the near-wall region. However, with the presence of ribs, all components of Reynolds normal stresses increase dramatically (monotonically as the value of

$y/\delta =0.079$

and 0.036 for cases SC and SCR, respectively) in the near-wall region. However, with the presence of ribs, all components of Reynolds normal stresses increase dramatically (monotonically as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases), and reach their maxima in the ISL around the rib height. Specifically, the peak value of

$P/H$

increases), and reach their maxima in the ISL around the rib height. Specifically, the peak value of

![]() $\langle u'u'\rangle$

is located at

$\langle u'u'\rangle$

is located at

![]() $y/\delta =0.23$

in all four ribbed cases, slightly above the rib crest, while the peaks of

$y/\delta =0.23$

in all four ribbed cases, slightly above the rib crest, while the peaks of

![]() $\langle v'v'\rangle$

and

$\langle v'v'\rangle$

and

![]() $\langle w'w'\rangle$

move downwards as the value of

$\langle w'w'\rangle$

move downwards as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases.

$P/H$

increases.

Figure 5. Vertical profiles of non-dimensional Reynolds normal stresses at the midspan between two adjacent ribs (

![]() $x'/\delta =0.5$

, 0.7, 0.95 and 0.95 for cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R, respectively). Arrow points to the direction of an increasing value of

$x'/\delta =0.5$

, 0.7, 0.95 and 0.95 for cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R, respectively). Arrow points to the direction of an increasing value of

![]() $P/H$

for cases of

$P/H$

for cases of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

. The vertical pink dashed line demarcates the rib top.

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

. The vertical pink dashed line demarcates the rib top.

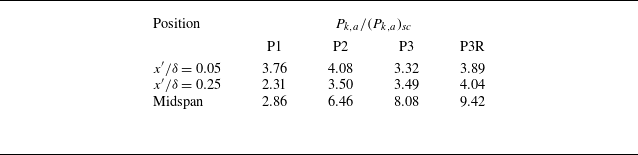

Table 2 summarises the key flow parameters of the six test cases. Here, two friction Reynolds numbers (

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{\tau R}=\delta u_{\tau R}/\nu$

and

${\textit{Re}}_{\tau R}=\delta u_{\tau R}/\nu$

and

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{\tau S}=\delta u_{\tau S}/\nu$

) are defined based on the mean streamwise wall friction velocities on the ribbed bottom wall (

${\textit{Re}}_{\tau S}=\delta u_{\tau S}/\nu$

) are defined based on the mean streamwise wall friction velocities on the ribbed bottom wall (

![]() $u_{\tau R}$

) and smooth top wall (

$u_{\tau R}$

) and smooth top wall (

![]() $u_{\tau S}$

), respectively. In the simulations, the value of the mean streamwise pressure gradient

$u_{\tau S}$

), respectively. In the simulations, the value of the mean streamwise pressure gradient

![]() $\varPi$

of (2.2) was carefully adjusted through test runs to ensure that the bulk Reynolds number calculated from DNS converged to its nominal value of either

$\varPi$

of (2.2) was carefully adjusted through test runs to ensure that the bulk Reynolds number calculated from DNS converged to its nominal value of either

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

or 14 600. The method for calculating the values of friction velocities follows the approaches of Napoli, Armenio & De Marchis (Reference Napoli, Armenio and De Marchis2008), Xiong et al. (Reference Xiong, Xu, Wang and Mahmoodi-Jezeh2023) and Opperman, Xiong & Wang (Reference Opperman, Xiong and Wang2025), viz.

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

or 14 600. The method for calculating the values of friction velocities follows the approaches of Napoli, Armenio & De Marchis (Reference Napoli, Armenio and De Marchis2008), Xiong et al. (Reference Xiong, Xu, Wang and Mahmoodi-Jezeh2023) and Opperman, Xiong & Wang (Reference Opperman, Xiong and Wang2025), viz.

![]() $ u^2_{\tau R} = (D_{\textit{pR}} +D_{\nu R})/\rho$

and

$ u^2_{\tau R} = (D_{\textit{pR}} +D_{\nu R})/\rho$

and

![]() $u^2_{\tau S} = D_{\nu S}/\rho$

. Here,

$u^2_{\tau S} = D_{\nu S}/\rho$

. Here,

![]() $D_{\textit{pR}}$

,

$D_{\textit{pR}}$

,

![]() $D_{\nu R}$

and

$D_{\nu R}$

and

![]() $D_{\nu S}$

are the mean pressure and viscous drags per unit area on the ribbed wall, and the mean viscous drag per unit area on the smooth wall, respectively, determined as

$D_{\nu S}$

are the mean pressure and viscous drags per unit area on the ribbed wall, and the mean viscous drag per unit area on the smooth wall, respectively, determined as

and

where

![]() $\mu=\rho\nu$

is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid, and subscripts ‘

$\mu=\rho\nu$

is the dynamic viscosity of the fluid, and subscripts ‘

![]() $R$

’ and ‘

$R$

’ and ‘

![]() $S$

’ indicate the integration of local wall values over the curved ribbed bottom and smooth top walls, respectively.

$S$

’ indicate the integration of local wall values over the curved ribbed bottom and smooth top walls, respectively.

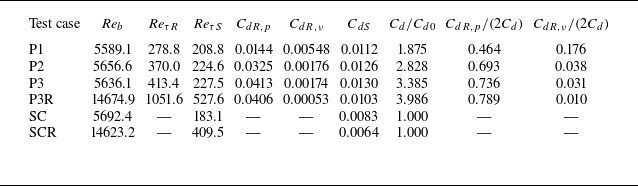

Table 2. Key parameters of the mean flow fields of the six test cases. Here,

![]() $C_{d0}$

denotes the drag coefficient of a smooth turbulent plane-channel flow at

$C_{d0}$

denotes the drag coefficient of a smooth turbulent plane-channel flow at

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

(for cases P1, P2, P3 and SC) or at

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

(for cases P1, P2, P3 and SC) or at

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=14\,600$

(for cases P3R and SCR).

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=14\,600$

(for cases P3R and SCR).

The pressure and viscous drag coefficients on the ribbed wall are defined as

![]() $C_{dR,p} = D_{\textit{pR}}/( \rho U_b^2/2)$

and

$C_{dR,p} = D_{\textit{pR}}/( \rho U_b^2/2)$

and

![]() $C_{dR,\nu } = D_{\nu R}/(\rho U_b^2/2)$

, respectively. Similarly,

$C_{dR,\nu } = D_{\nu R}/(\rho U_b^2/2)$

, respectively. Similarly,

![]() $C_{dS}=D_{\nu S}/(\rho U_b^2/2)$

is the drag coefficient on the smooth wall. In addition, the total drag coefficient of the ribbed channel is calculated by

$C_{dS}=D_{\nu S}/(\rho U_b^2/2)$

is the drag coefficient on the smooth wall. In addition, the total drag coefficient of the ribbed channel is calculated by

![]() $C_{d}=(C_{dR,p}+C_{dR,\nu }+C_{dS})/2$

. Table 2 clearly shows that in the presence of the ribs, the drag augments drastically compared with that in a smooth channel, and the drag coefficient

$C_{d}=(C_{dR,p}+C_{dR,\nu }+C_{dS})/2$

. Table 2 clearly shows that in the presence of the ribs, the drag augments drastically compared with that in a smooth channel, and the drag coefficient

![]() $C_d$

increases monotonically with an increasing value of

$C_d$

increases monotonically with an increasing value of

![]() $P/H$

. By comparing cases P3 and P3R, it is seen that as the Reynolds number increases, the drag coefficient decreases in both ribbed- and smooth-channel flows; however, the ratio

$P/H$

. By comparing cases P3 and P3R, it is seen that as the Reynolds number increases, the drag coefficient decreases in both ribbed- and smooth-channel flows; however, the ratio

![]() $C_d/C_{d0}$

increases from 3.385 to 3.986. Here,

$C_d/C_{d0}$

increases from 3.385 to 3.986. Here,

![]() $C_{d0}$

denotes the total drag coefficient of a smooth turbulent plane-channel flow of the corresponding Reynolds number (i.e.

$C_{d0}$

denotes the total drag coefficient of a smooth turbulent plane-channel flow of the corresponding Reynolds number (i.e.

![]() $C_{d0}=C_{dS}$

for case SC or SCR). It is clear that as the value of

$C_{d0}=C_{dS}$

for case SC or SCR). It is clear that as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases, the drag on both top and bottom walls increases. Accordingly, both values of

$P/H$

increases, the drag on both top and bottom walls increases. Accordingly, both values of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{\tau R}$

and

${\textit{Re}}_{\tau R}$

and

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{\tau S}$

increase as the value of

${\textit{Re}}_{\tau S}$

increase as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases. By comparing the values of

$P/H$

increases. By comparing the values of

![]() $C_{dR,p}$

,

$C_{dR,p}$

,

![]() $C_{dR,\nu }$

and

$C_{dR,\nu }$

and

![]() $C_{dS}$

listed in table 2, it is evident that the pressure drag contributes the most to the total drag in all four ribbed channels due to the large boundary-layer separation regions induced by ribs. As the value of

$C_{dS}$

listed in table 2, it is evident that the pressure drag contributes the most to the total drag in all four ribbed channels due to the large boundary-layer separation regions induced by ribs. As the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases (from case P1 to P3), the pressure drag becomes increasingly predominant and the viscous drag on the ribbed walls becomes trivial, as a result of the expansion of the relatively high-pressure region on the windward surface of a rib (associated with the evolutions of vortices A and C shown previously in figure 3). By comparing cases P3 and P3R, it is clear that as the Reynolds number increases from

$P/H$

increases (from case P1 to P3), the pressure drag becomes increasingly predominant and the viscous drag on the ribbed walls becomes trivial, as a result of the expansion of the relatively high-pressure region on the windward surface of a rib (associated with the evolutions of vortices A and C shown previously in figure 3). By comparing cases P3 and P3R, it is clear that as the Reynolds number increases from

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

to 14 600, the contribution of the pressure drag to the total drag (

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

to 14 600, the contribution of the pressure drag to the total drag (

![]() $C_{dR,p}/(2C_d)$

) further increases from 73.6 % to 77.2 % in the ribbed channel. Leonardi, Orlandi & Antonia (Reference Leonardi, Orlandi and Antonia2007) conducted DNS of turbulent channel flows over square bars, and observed that the viscous drag coefficient on the ribbed wall became negative if

$C_{dR,p}/(2C_d)$

) further increases from 73.6 % to 77.2 % in the ribbed channel. Leonardi, Orlandi & Antonia (Reference Leonardi, Orlandi and Antonia2007) conducted DNS of turbulent channel flows over square bars, and observed that the viscous drag coefficient on the ribbed wall became negative if

![]() $P/H\gt 4$

. By contrast, negatively valued

$P/H\gt 4$

. By contrast, negatively valued

![]() $C_{dR,\nu }$

is not observed in cases P2, P3 and P3R here, although it decreases with an increasing value of

$C_{dR,\nu }$

is not observed in cases P2, P3 and P3R here, although it decreases with an increasing value of

![]() $P/H$

. In turbulent flows over circular-arc ribs, the mean reattachment point R moves upwards as the value of

$P/H$

. In turbulent flows over circular-arc ribs, the mean reattachment point R moves upwards as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases such that the region with positively valued local skin friction coefficient extends, contributing positively to the viscous drag over the ribbed wall.

$P/H$

increases such that the region with positively valued local skin friction coefficient extends, contributing positively to the viscous drag over the ribbed wall.

4. Rib effects on the characteristic spanwise scale of turbulence structures

4.1. Streak-like structures in the ISL

The high- and low-speed streaks associated with turbulent coherent motions play an important role in the transport of momentum and TKE in near-wall turbulence, which has been well studied in the context of 2-D turbulent boundary layers over flat plates (Smith & Metzler Reference Smith and Metzler1983; Chernyshenko & Baig Reference Chernyshenko and Baig2005; Adrian Reference Adrian2007). In the current study of ribbed channels, the energetic turbulence structures occur in the ISL and are affected strongly by the ribs. Consequently, the streak-like structures in the ISL are essentially different from those in the canonical 2-D turbulent boundary layers. To demonstrate, figure 6 compares the streak-like structures in smooth- and ribbed-channel flows using the contours of non-dimensional instantaneous streamwise velocity fluctuations

![]() $u'/U_b$

in the

$u'/U_b$

in the

![]() $x$

-

$x$

-

![]() $z$

plane. In figure 6, the vertical elevations of the

$z$

plane. In figure 6, the vertical elevations of the

![]() $x$

-

$x$

-

![]() $z$

planes are chosen at the peak position of

$z$

planes are chosen at the peak position of

![]() $\langle u'u'\rangle$

shown in figure 5(a), i.e. at

$\langle u'u'\rangle$

shown in figure 5(a), i.e. at

![]() $y^+=15$

for the smooth-channel-flow case SC in the buffer layer where the high- and low-speed streaks are typical (Smith & Metzler Reference Smith and Metzler1983; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Moin and Moser1987), and at

$y^+=15$

for the smooth-channel-flow case SC in the buffer layer where the high- and low-speed streaks are typical (Smith & Metzler Reference Smith and Metzler1983; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Moin and Moser1987), and at

![]() $y/\delta =0.23$

for the ribbed-channel-flow cases. As shown in figure 6, the presence of streak-like structures is evident in the ISL. It is apparent that the streak-like structures in the ribbed channels become more intense compared with those in a smooth-channel flow, as a result of the enhanced turbulent motions in the ISL. The strength of streak-like structures further increases as the value of

$y/\delta =0.23$

for the ribbed-channel-flow cases. As shown in figure 6, the presence of streak-like structures is evident in the ISL. It is apparent that the streak-like structures in the ribbed channels become more intense compared with those in a smooth-channel flow, as a result of the enhanced turbulent motions in the ISL. The strength of streak-like structures further increases as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases. Moreover, owing to the presence of ribs, the streak-like structures become shortened dramatically along the streamwise direction in the ribbed channels. Furthermore, the spanwise spacing between high- and low-speed streak-like structures reflects the characteristic spanwise scales of the quasi-streamwise vortices (i.e. the hairpin legs), which are the dominant flow structures in the buffer layer of wall-bounded turbulent flows (Robinson Reference Robinson1991; Adrian, Meinhart & Tomkins Reference Adrian, Meinhart and Tomkins2000). From figures 6(b) and 6(c), it is apparent that the spanwise spacing between high- and low-speed streak-like structures increases slightly as the value of

$P/H$

increases. Moreover, owing to the presence of ribs, the streak-like structures become shortened dramatically along the streamwise direction in the ribbed channels. Furthermore, the spanwise spacing between high- and low-speed streak-like structures reflects the characteristic spanwise scales of the quasi-streamwise vortices (i.e. the hairpin legs), which are the dominant flow structures in the buffer layer of wall-bounded turbulent flows (Robinson Reference Robinson1991; Adrian, Meinhart & Tomkins Reference Adrian, Meinhart and Tomkins2000). From figures 6(b) and 6(c), it is apparent that the spanwise spacing between high- and low-speed streak-like structures increases slightly as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases, showing a larger spanwise scale of turbulent motions in the ISL. Moreover, it is interesting to see that in case P3R, the streak-like structures become fragmented and the presence of small-scale spotty structures is evident in the

$P/H$

increases, showing a larger spanwise scale of turbulent motions in the ISL. Moreover, it is interesting to see that in case P3R, the streak-like structures become fragmented and the presence of small-scale spotty structures is evident in the

![]() $x$

-

$x$

-

![]() $z$

plane of figure 6(d), indicating an enhancement in the small-scale turbulent motions at a higher Reynolds number.

$z$

plane of figure 6(d), indicating an enhancement in the small-scale turbulent motions at a higher Reynolds number.

Figure 6. Contours of non-dimensional instantaneous streamwise velocity fluctuations

![]() $u'/U_b$

in the

$u'/U_b$

in the

![]() $x$

-

$x$

-

![]() $z$

planes, located at the peak position of

$z$

planes, located at the peak position of

![]() $\langle u'u'\rangle$

, i.e. at

$\langle u'u'\rangle$

, i.e. at

![]() $y^+=15$

for the smooth-channel case SC and at

$y^+=15$

for the smooth-channel case SC and at

![]() $y/\delta =0.23$

for the ribbed-channel cases P1, P3 and P3R.

$y/\delta =0.23$

for the ribbed-channel cases P1, P3 and P3R.

4.2. Spectral analysis of turbulent motions in the ISL

Owing to the spanwise homogeneity of the test cases, the premultiplied energy spectrum

![]() $k_3\varPhi _k$

of TKE is a useful tool for analysing the characteristic spanwise scale of the turbulence structures, where

$k_3\varPhi _k$

of TKE is a useful tool for analysing the characteristic spanwise scale of the turbulence structures, where

![]() $\varPhi _k={\textit{Re}}\{\overline {\widehat {u^{\prime}_i}^*\widehat {u^{\prime}_i}}\}/2$

is the spanwise energy spectrum of TKE. Here, an overline

$\varPhi _k={\textit{Re}}\{\overline {\widehat {u^{\prime}_i}^*\widehat {u^{\prime}_i}}\}/2$

is the spanwise energy spectrum of TKE. Here, an overline

![]() $\overline {(\boldsymbol{\cdot })}$

denotes averaging over time

$\overline {(\boldsymbol{\cdot })}$

denotes averaging over time

![]() $t$

, and, additionally, over all rib periods (for cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R) or the homogeneous streamwise direction for the two smooth-channel-flow cases SC and SCR. Subscript ‘

$t$

, and, additionally, over all rib periods (for cases P1, P2, P3 and P3R) or the homogeneous streamwise direction for the two smooth-channel-flow cases SC and SCR. Subscript ‘

![]() $k$

’ is used to denote TKE. Superscript ‘*’ and operator

$k$

’ is used to denote TKE. Superscript ‘*’ and operator

![]() ${\textit{Re}}\{\boldsymbol{\cdot }\}$

denote the conjugate and the real part of a complex number, respectively. A hat

${\textit{Re}}\{\boldsymbol{\cdot }\}$

denote the conjugate and the real part of a complex number, respectively. A hat

![]() $\widehat {(\boldsymbol{\cdot })}$

denotes the Fourier transform of an arbitrary variable in the spanwise direction. As such,

$\widehat {(\boldsymbol{\cdot })}$

denotes the Fourier transform of an arbitrary variable in the spanwise direction. As such,

![]() $\widehat {u^{\prime}_i}=\widehat {u^{\prime}_i}(x_1,x_2,k_3,t)$

is the Fourier transform of velocity fluctuations

$\widehat {u^{\prime}_i}=\widehat {u^{\prime}_i}(x_1,x_2,k_3,t)$

is the Fourier transform of velocity fluctuations

![]() $u^{\prime}_i$

, where

$u^{\prime}_i$

, where

![]() $k_3=n_3k_{03}$

is the spanwise wavenumber with

$k_3=n_3k_{03}$

is the spanwise wavenumber with

![]() $n_3\in [0,N_z/2]$

being an integer and

$n_3\in [0,N_z/2]$

being an integer and

![]() $k_{03}=2\pi /L_z$

being the lowest positive wavenumber in the spanwise direction.

$k_{03}=2\pi /L_z$

being the lowest positive wavenumber in the spanwise direction.

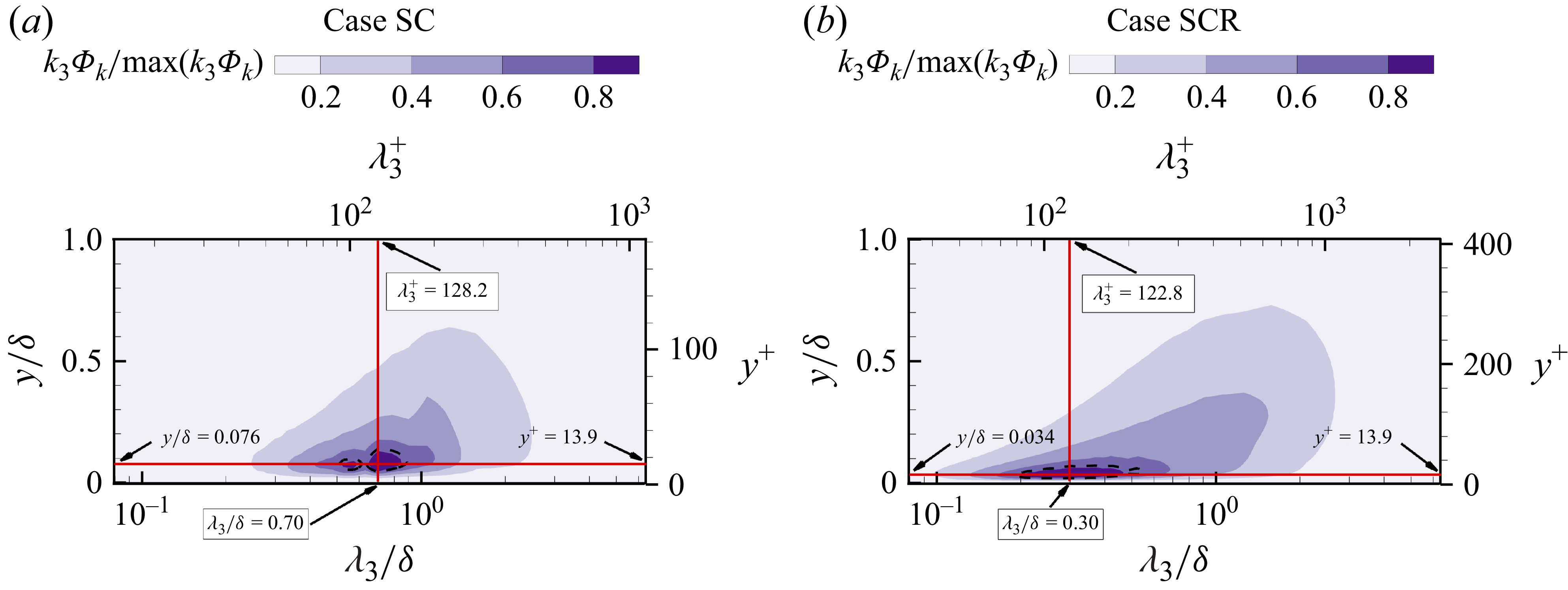

Figure 7 shows the contours of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _k$

normalised by its maximum in a

$k_3\varPhi _k$

normalised by its maximum in a

![]() $\lambda _3$

-

$\lambda _3$

-

![]() $y$

plane for the two smooth-channel cases, where

$y$

plane for the two smooth-channel cases, where

![]() $\lambda _3=2\pi /k_3$

is the spanwise wavelength. The spanwise wavelength

$\lambda _3=2\pi /k_3$

is the spanwise wavelength. The spanwise wavelength

![]() $\lambda _3$

is shown in a logarithmic coordinate, given the large range of the spanwise wavelengths of turbulence structures. From figure 7, it is clear that

$\lambda _3$

is shown in a logarithmic coordinate, given the large range of the spanwise wavelengths of turbulence structures. From figure 7, it is clear that

![]() $k_3\varPhi _k$

peaks near the wall around

$k_3\varPhi _k$

peaks near the wall around

![]() $[\lambda _3^+,y^+]\approx [125,13.9]$

for both cases SC and SCR. Clearly, the peak of

$[\lambda _3^+,y^+]\approx [125,13.9]$

for both cases SC and SCR. Clearly, the peak of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _k$

in the smooth-channel flow results from the canonical near-wall streaky structures in the buffer layer shown previously in figure 6(a), which typically possess a mean spanwise spacing of

$k_3\varPhi _k$

in the smooth-channel flow results from the canonical near-wall streaky structures in the buffer layer shown previously in figure 6(a), which typically possess a mean spanwise spacing of

![]() $\lambda _z^+\approx 100$

(Smith & Metzler Reference Smith and Metzler1983; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Moin and Moser1987). Figure 8 shows the isosurfaces of normalised premultiplied energy spectra

$\lambda _z^+\approx 100$

(Smith & Metzler Reference Smith and Metzler1983; Kim et al. Reference Kim, Moin and Moser1987). Figure 8 shows the isosurfaces of normalised premultiplied energy spectra

![]() $(k_3\varPhi _k)/\max (k_3\varPhi _k)$

of the four ribbed-channel cases. From figure 8, it is apparent that the region with high levels of TKE is primarily concentrated in the ISL, especially in the inter-rib region where the isosurface of

$(k_3\varPhi _k)/\max (k_3\varPhi _k)$

of the four ribbed-channel cases. From figure 8, it is apparent that the region with high levels of TKE is primarily concentrated in the ISL, especially in the inter-rib region where the isosurface of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _k=0.9\max (k_3\varPhi _k)$

is located. It is seen that the cross-stream plane at the midspan between two adjacent ribs intersects with the isosurface of

$k_3\varPhi _k=0.9\max (k_3\varPhi _k)$

is located. It is seen that the cross-stream plane at the midspan between two adjacent ribs intersects with the isosurface of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _k=0.9\max (k_3\varPhi _k)$

in all four ribbed-channel cases, signifying the presence of energetic turbulence eddies at this streamwise position. As is evident in figure 8,

$k_3\varPhi _k=0.9\max (k_3\varPhi _k)$

in all four ribbed-channel cases, signifying the presence of energetic turbulence eddies at this streamwise position. As is evident in figure 8,

![]() $k_3\varPhi _k$

peaks near the ribbed bottom wall at the midspan between two adjacent ribs in the ISL around the rib height. Specifically, as the value of

$k_3\varPhi _k$

peaks near the ribbed bottom wall at the midspan between two adjacent ribs in the ISL around the rib height. Specifically, as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases from 3.0 to 5.0 and 7.5, the vertical position of this peak moves downwards from

$P/H$

increases from 3.0 to 5.0 and 7.5, the vertical position of this peak moves downwards from

![]() $y/\delta =0.239$

to 0.203 and 0.184, corresponding to the downward movement of the peak vertical positions of

$y/\delta =0.239$

to 0.203 and 0.184, corresponding to the downward movement of the peak vertical positions of

![]() $\langle v'v'\rangle$

and

$\langle v'v'\rangle$

and

![]() $\langle w'w'\rangle$

shown previously in figure 5. At the midspan between two adjacent ribs as shown in figure 8, the characteristic spanwise wavelength

$\langle w'w'\rangle$

shown previously in figure 5. At the midspan between two adjacent ribs as shown in figure 8, the characteristic spanwise wavelength

![]() $\lambda _3^+$

increases from 158.9 to 260.4 as the value of

$\lambda _3^+$

increases from 158.9 to 260.4 as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases from case P1 to P3 (at

$P/H$

increases from case P1 to P3 (at

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

), and further increases to 595.3 in case P3R (at a higher Reynolds number of

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

), and further increases to 595.3 in case P3R (at a higher Reynolds number of

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=14\,600$

). This range of characteristic spanwise wavelengths of ribbed-channel flows is considerably larger than that of a smooth plane-channel flow. Given that

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=14\,600$

). This range of characteristic spanwise wavelengths of ribbed-channel flows is considerably larger than that of a smooth plane-channel flow. Given that

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{\tau R}$

increases with the pitch-to-height ratio (table 2), it is clear that the magnitude of characteristic spanwise wavelength

${\textit{Re}}_{\tau R}$

increases with the pitch-to-height ratio (table 2), it is clear that the magnitude of characteristic spanwise wavelength

![]() $\lambda _3^+$

is sensitive to the (friction) Reynolds number. By contrast, the characteristic spanwise wavelength scaled by

$\lambda _3^+$

is sensitive to the (friction) Reynolds number. By contrast, the characteristic spanwise wavelength scaled by

![]() $\delta$

is less sensitive to changes in

$\delta$

is less sensitive to changes in

![]() $P/H$

and

$P/H$

and

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_b$

, which varies slightly from

${\textit{Re}}_b$

, which varies slightly from

![]() $\lambda _3/\delta =0.57$

to 0.63 as the value of

$\lambda _3/\delta =0.57$

to 0.63 as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases from case P1 to P3 (at

$P/H$

increases from case P1 to P3 (at

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

), and to

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=5600$

), and to

![]() $\lambda _3/\delta =0.57$

in case P3R (at

$\lambda _3/\delta =0.57$

in case P3R (at

![]() ${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=14\,600$

). Clearly, in the ISL of ribbed-channel flows, it is more proper to use

${\textit{Re}}_{b,N}=14\,600$

). Clearly, in the ISL of ribbed-channel flows, it is more proper to use

![]() $\delta$

to scale the characteristic spanwise wavelengths of energy-containing eddies instead of using wall units. Because of the relatively large height (or blockage ratio) of the ribs, it is more adequate to treat the rib geometries of this research as flow boundary conditions rather than roughness effects.

$\delta$

to scale the characteristic spanwise wavelengths of energy-containing eddies instead of using wall units. Because of the relatively large height (or blockage ratio) of the ribs, it is more adequate to treat the rib geometries of this research as flow boundary conditions rather than roughness effects.

Figure 7. Contours of premultiplied energy spectrum of TKE (

![]() $k_3\varPhi _k$

) normalised by its maximum in the

$k_3\varPhi _k$

) normalised by its maximum in the

![]() $\lambda _3$

-

$\lambda _3$

-

![]() $y$

plane for smooth-channel-flow cases SC and SCR. The black dashed isopleth corresponds to

$y$

plane for smooth-channel-flow cases SC and SCR. The black dashed isopleth corresponds to

![]() $k_3\varPhi _k=0.75\max (k_3\varPhi _k)$

. The red solid lines demarcate the peak position of

$k_3\varPhi _k=0.75\max (k_3\varPhi _k)$

. The red solid lines demarcate the peak position of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _k$

.

$k_3\varPhi _k$

.

Figure 8. Isosurfaces of the normalised premultiplied energy spectra of TKE

![]() $(k_3\varPhi _k)/\max {(k_3\varPhi _k)}$

of the four ribbed-channel-flow cases plotted with respect to

$(k_3\varPhi _k)/\max {(k_3\varPhi _k)}$

of the four ribbed-channel-flow cases plotted with respect to

![]() $\lambda _3/\delta$

. For clarity, only isosurfaces of

$\lambda _3/\delta$

. For clarity, only isosurfaces of

![]() $(k_3\varPhi _k)/\max {(k_3\varPhi _k)}=0.75$

, 0.825 and 0.9 are shown. Contours of

$(k_3\varPhi _k)/\max {(k_3\varPhi _k)}=0.75$

, 0.825 and 0.9 are shown. Contours of

![]() $(k_3\varPhi _k)/\max {(k_3\varPhi _k)}$

are further plotted against

$(k_3\varPhi _k)/\max {(k_3\varPhi _k)}$

are further plotted against

![]() $\lambda _3^+$

(based on

$\lambda _3^+$

(based on

![]() $\nu /u_{\tau R}$

) in a cross-stream plane located streamwise at the midspan between two adjacent ribs, where a red isopleth corresponds to

$\nu /u_{\tau R}$

) in a cross-stream plane located streamwise at the midspan between two adjacent ribs, where a red isopleth corresponds to

![]() $(k_3\varPhi _k)/\max {(k_3\varPhi _k)}=0.75$

, and blue solid lines are used to delineate the peak position of

$(k_3\varPhi _k)/\max {(k_3\varPhi _k)}=0.75$

, and blue solid lines are used to delineate the peak position of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _k$

. Values scaled by

$k_3\varPhi _k$

. Values scaled by

![]() $\delta$

(i.e.

$\delta$

(i.e.

![]() $y/\delta$

and

$y/\delta$

and

![]() $\lambda _3/\delta$

) are in black colour, while values scaled by wall units (i.e.

$\lambda _3/\delta$

) are in black colour, while values scaled by wall units (i.e.

![]() $\lambda _3^+$

) are in green colour.

$\lambda _3^+$

) are in green colour.

Figure 9 further compares the premultiplied streamwise, vertical and spanwise velocity spectra

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{11}$

,

$k_3\varPhi _{11}$

,

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{22}$

and

$k_3\varPhi _{22}$

and

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{33}$

scaled by

$k_3\varPhi _{33}$

scaled by

![]() $U_b^2$

at the midspan between two adjacent ribs. Here,

$U_b^2$

at the midspan between two adjacent ribs. Here,

![]() $\Phi_{ii}$

is the energy spectrum of velocity fluctuations for

$\Phi_{ii}$

is the energy spectrum of velocity fluctuations for

![]() $i=1$

, 2 or 3 (summation convention is not applied). The vertical position chosen for extracting the profiles of

$i=1$

, 2 or 3 (summation convention is not applied). The vertical position chosen for extracting the profiles of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{ii}$

is at

$k_3\varPhi _{ii}$

is at

![]() $y/\delta =0.23$

in the ISL, where

$y/\delta =0.23$

in the ISL, where

![]() $\langle u'u'\rangle$

peaks in all four ribbed cases. By comparing figure 9(a–c), it is interesting to observe that the profiles of

$\langle u'u'\rangle$

peaks in all four ribbed cases. By comparing figure 9(a–c), it is interesting to observe that the profiles of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{11}$

from cases P1, P2 and P3 collapse at small spanwise wavelengths for

$k_3\varPhi _{11}$

from cases P1, P2 and P3 collapse at small spanwise wavelengths for

![]() $\lambda _3/\delta \lt 0.3$

; however, the magnitudes of

$\lambda _3/\delta \lt 0.3$

; however, the magnitudes of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{22}$

and

$k_3\varPhi _{22}$

and

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{33}$

increase considerably with an increasing value of

$k_3\varPhi _{33}$

increase considerably with an increasing value of

![]() $P/H$

at all wavelengths. It is understood that for small-scale turbulent motions of

$P/H$

at all wavelengths. It is understood that for small-scale turbulent motions of

![]() $\lambda _3/\delta \lt 0.3$

, only the vertical and spanwise velocity fluctuations are intensified at the selected elevation (

$\lambda _3/\delta \lt 0.3$

, only the vertical and spanwise velocity fluctuations are intensified at the selected elevation (

![]() $y/\delta =0.23$

) in the ISL as the value of

$y/\delta =0.23$

) in the ISL as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases. Moreover, it is observed that the characteristic wavelength corresponding to the peak of

$P/H$

increases. Moreover, it is observed that the characteristic wavelength corresponding to the peak of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{11}$

increases from

$k_3\varPhi _{11}$

increases from

![]() $\lambda _3/\delta =0.57$

to 0.63 and 0.78 as the value of

$\lambda _3/\delta =0.57$

to 0.63 and 0.78 as the value of

![]() $P/H$

increases from 3.0 to 5.0 and 7.5, whereas those of

$P/H$

increases from 3.0 to 5.0 and 7.5, whereas those of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{22}$

and

$k_3\varPhi _{22}$

and

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{33}$

are insensitive to the pitch-to-height ratio. The constant modal wavelengths are

$k_3\varPhi _{33}$

are insensitive to the pitch-to-height ratio. The constant modal wavelengths are

![]() $\lambda _3/\delta =0.39$

for

$\lambda _3/\delta =0.39$

for

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{22}$

and 0.63 for

$k_3\varPhi _{22}$

and 0.63 for

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{33}$

, delineated using two vertical dashed lines in figures 9(b) and 9(c), respectively. It is worth noting that these two characteristic wavelengths of

$k_3\varPhi _{33}$

, delineated using two vertical dashed lines in figures 9(b) and 9(c), respectively. It is worth noting that these two characteristic wavelengths of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{22}$

and

$k_3\varPhi _{22}$

and

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{33}$

are approximately

$k_3\varPhi _{33}$

are approximately

![]() $2H$

and

$2H$

and

![]() $3H$

, respectively. These results are similar to those of Mahmoodi-Jezeh & Wang (Reference Mahmoodi-Jezeh and Wang2020), who performed a DNS study of ribbed duct flows and examined the spanwise spacing of streaky structures in the central region of the duct. By comparing cases P3 and P3R, it is observed that at a higher Reynolds number, the characteristic wavelength of

$3H$

, respectively. These results are similar to those of Mahmoodi-Jezeh & Wang (Reference Mahmoodi-Jezeh and Wang2020), who performed a DNS study of ribbed duct flows and examined the spanwise spacing of streaky structures in the central region of the duct. By comparing cases P3 and P3R, it is observed that at a higher Reynolds number, the characteristic wavelength of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{11}$

decreases to

$k_3\varPhi _{11}$

decreases to

![]() $\lambda _3/\delta =0.70$

, while those of

$\lambda _3/\delta =0.70$

, while those of

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{22}$

and

$k_3\varPhi _{22}$

and

![]() $k_3\varPhi _{33}$

remain unchanged corresponding to

$k_3\varPhi _{33}$

remain unchanged corresponding to

![]() $\lambda _3/\delta =0.39$

and 0.63, respectively. Furthermore, it is noticed that as the Reynolds number increases, the intensities of all three velocity fluctuations

$\lambda _3/\delta =0.39$

and 0.63, respectively. Furthermore, it is noticed that as the Reynolds number increases, the intensities of all three velocity fluctuations

![]() $u'$

,

$u'$

,

![]() $v'$

and

$v'$

and

![]() $w'$

enhance at small wavelengths of

$w'$

enhance at small wavelengths of

![]() $\lambda _3/\delta \lt 0.3$

and weaken at larger wavelengths of

$\lambda _3/\delta \lt 0.3$

and weaken at larger wavelengths of

![]() $0.3\lt \lambda _3/\delta \lt 2.0$

(when scaled by

$0.3\lt \lambda _3/\delta \lt 2.0$

(when scaled by

![]() $U_b$

). As such, it is clear that as the Reynolds number increases, the contribution from fragmented smaller-scale eddies (shown vividly in figure 6

d) to TKE increases considerably.

$U_b$

). As such, it is clear that as the Reynolds number increases, the contribution from fragmented smaller-scale eddies (shown vividly in figure 6

d) to TKE increases considerably.

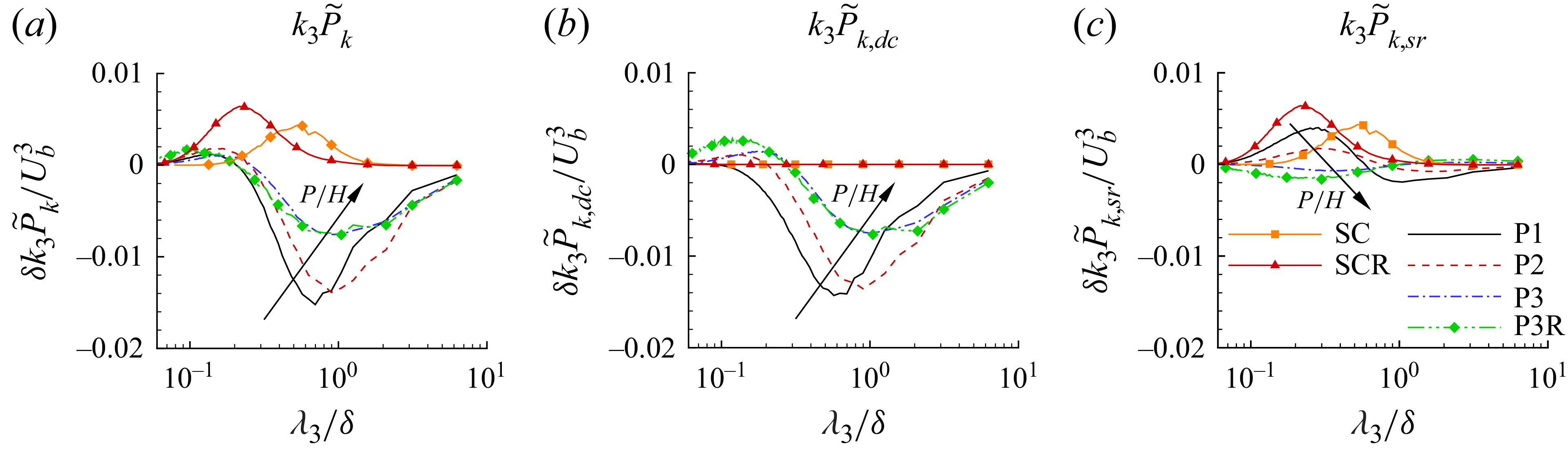

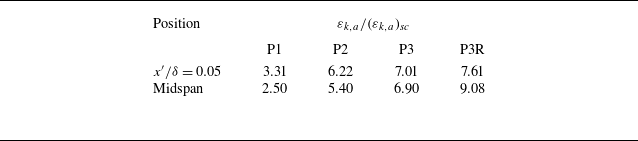

Figure 9. Profiles of premultiplied energy spectra