1. Introduction

The origin of high-energy emissions in the Universe is often a non-thermal power-law spectrum of relativistic particles. Therefore, to explain high-energy emissions, it is necessary to understand how power-law distributions of non-thermal particles are populated and sustained, with the former being the concern of injection studies and the latter being the concern of studies about non-thermal particle acceleration to high energies.

The question of how a power-law distribution of particles is populated may be decomposed into two questions: (i) Under what conditions are particles injected, i.e. eligible to participate in a continual, power-law-forming acceleration process? (ii) What physical mechanisms are responsible for injection?

Regarding the first question, the injection criterion has typically been expressed since Fermi (Reference Fermi1949) as an energy threshold

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

that a particle must surpass, so that particles with energy

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

that a particle must surpass, so that particles with energy

![]() $\gamma \gt \gamma _{\textrm { inj}}$

are ‘injected’ and can experience further Fermi acceleration to even higher energies, whereas those with

$\gamma \gt \gamma _{\textrm { inj}}$

are ‘injected’ and can experience further Fermi acceleration to even higher energies, whereas those with

![]() $\gamma \lt \gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

cannot. Physically, this may be owed to the relativistic gyroradius of particles scaling linearly with

$\gamma \lt \gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

cannot. Physically, this may be owed to the relativistic gyroradius of particles scaling linearly with

![]() $\gamma$

, which facilitates acceleration via stochastic scattering off of turbulent fluctuations (Lemoine & Malkov Reference Lemoine and Malkov2020). In this study, we also presuppose that

$\gamma$

, which facilitates acceleration via stochastic scattering off of turbulent fluctuations (Lemoine & Malkov Reference Lemoine and Malkov2020). In this study, we also presuppose that

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

exists and define it as the low-energy boundary of the non-thermal power-law segment of the downstream particle distribution function. Thus, the first question is recast as a problem of relating

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

exists and define it as the low-energy boundary of the non-thermal power-law segment of the downstream particle distribution function. Thus, the first question is recast as a problem of relating

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

to the system parameters and explaining the connection.

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

to the system parameters and explaining the connection.

Accordingly, the second question is also recast: it is to understand what ‘injection mechanisms’ – mechanisms that accelerate particles from a thermal upstream to or beyond the injection energy

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

that gates the non-thermal power-law spectrum – are active, how much work they do to each particle and upon how many particles they act.

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

that gates the non-thermal power-law spectrum – are active, how much work they do to each particle and upon how many particles they act.

These questions of particle injection have been largely unresolved across several processes that are thought to power high-energy emissions in relativistic astrophysical environments, such as jets from active galactic nuclei, pulsar wind nebulae, neutron star magnetospheres and accreting black hole coronae. These processes include relativistic turbulence (Chandran Reference Chandran2000; Zhdankin et al. Reference Zhdankin, Werner, Uzdensky and Begelman2017; Comisso & Sironi Reference Comisso and Sironi2018, Reference Comisso and Sironi2019; Zhdankin et al. Reference Zhdankin, Uzdensky, Werner and Begelman2018, Reference Zhdankin, Uzdensky, Werner and Begelman2019; Lemoine Reference Lemoine2019; Wong et al. Reference Wong, Zhdankin, Uzdensky, Werner and Begelman2020; Demidem, Lemoine & Casse Reference Demidem, Lemoine and Casse2020; Lemoine & Malkov Reference Lemoine and Malkov2020; Guo et al. Reference Guo, French, Zhang, Li and Seo2025; Mehlhaff, Zhou & Zhdankin Reference Mehlhaff, Zhou and Zhdankin2025), collisionless relativistic shocks (Blandford & Ostriker Reference Blandford and Ostriker1978; Blandford & Eichler Reference Blandford and Eichler1987; Spitkovsky Reference Spitkovsky2008; Sironi & Spitkovsky Reference Sironi and Spitkovsky2011; Caprioli & Spitkovsky Reference Caprioli and Spitkovsky2014; Parsons, Spitkovsky & Vanthieghem Reference Parsons, Spitkovsky and Vanthieghem2024) and relativistic magnetic reconnection (Bulanov & Sasorov Reference Bulanov and Sasorov1976; Blackman & Field Reference Blackman and Field1994; Zenitani & Hoshino Reference Zenitani and Hoshino2001; Jaroschek, Lesch & Treumann Reference Jaroschek, Lesch and Treumann2004; Giannios, Uzdensky & Begelman Reference Giannios, Uzdensky and Begelman2010; Cerutti et al. Reference Cerutti, Werner, Uzdensky and Begelman2013; Sironi & Spitkovsky Reference Sironi and Spitkovsky2014; Melzani et al. Reference Melzani, Walder, Folini, Winisdoerffer and Favre2014; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Li, Daughton and Liu2014, Reference Guo, Liu, Daughton and Li2015, Reference Guo, Li, Li, Daughton, Zhang, Lloyd-Ronning, Liu, Zhang and Deng2016, Reference Guo, Li, Daughton, Kilian, Li, Liu, Yan and Ma2019; Nalewajko et al. Reference Nalewajko, Uzdensky, Cerutti, Werner and Begelman2015; Werner et al. Reference Werner, Uzdensky, Cerutti, Nalewajko and Begelman2016; Rowan, Sironi & Narayan Reference Rowan, Sironi and Narayan2017; Werner & Uzdensky Reference Werner and Uzdensky2017; Petropoulou & Sironi Reference Petropoulou and Sironi2018; Werner et al. Reference Werner, Uzdensky, Begelman, Cerutti and Nalewajko2018; Schoeffler et al. Reference Schoeffler, Grismayer, Uzdensky, Fonseca and Silva2019; Kilian et al. Reference Kilian, Li, Guo and Zhang2020; Mehlhaff et al. Reference Mehlhaff, Werner, Uzdensky and Begelman2020; Hakobyan et al. Reference Hakobyan, Petropoulou, Spitkovsky and Sironi2021; Werner & Uzdensky Reference Werner and Uzdensky2021; Sironi Reference Sironi2022; Uzdensky Reference Uzdensky2022; French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023; Li et al. Reference Li, Guo, Liu and Li2023; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Sironi, Giannios and Petropoulou2023; Gupta, Sridhar & Sironi Reference Gupta, Sridhar and Sironi2025) (see Guo et al. Reference Guo, Liu, Zenitani and Hoshino2024; Sironi, Uzdensky & Giannios Reference Sironi, Uzdensky and Giannios2025, for recent reviews).

In the context of relativistic magnetic reconnection, several injection and high-energy acceleration mechanisms have been studied, both analytically and numerically via fully kinetic particle-in-cell (PIC) simulations: ‘direct’ acceleration by the parallel electric field with a finite guide magnetic field (i.e. a finite non-reversing, out-of-plane component of the magnetic field) near X-points (Larrabee, Lovelace & Romanova Reference Larrabee, Lovelace and Romanova2003; Zenitani & Hoshino Reference Zenitani and Hoshino2005, Reference Zenitani and Hoshino2008; Cerutti et al. Reference Cerutti, Werner, Uzdensky and Begelman2013, Reference Cerutti, Werner, Uzdensky and Begelman2014; Ball, Sironi & Özel Reference Ball, Sironi and Özel2019; Sironi Reference Sironi2022; Totorica et al. Reference Totorica, Zenitani, Matsukiyo, Machida, Sekiguchi and Bhattacharjee2023; Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Sridhar and Sironi2025), Speiser orbits in the case of zero guide field (Speiser Reference Speiser1965; Hoshino et al. Reference Hoshino, Mukai, Terasawa and Shinohara2001; Zenitani & Hoshino Reference Zenitani and Hoshino2001; Uzdensky, Cerutti & Begelman Reference Uzdensky, Cerutti and Begelman2011; Cerutti et al. Reference Cerutti, Uzdensky and Begelman2012, Reference Cerutti, Werner, Uzdensky and Begelman2013, Reference Cerutti, Werner, Uzdensky and Begelman2014; Nalewajko et al. Reference Nalewajko, Uzdensky, Cerutti, Werner and Begelman2015; Uzdensky Reference Uzdensky2022), Fermi acceleration (Fermi Reference Fermi1949; Drake et al. Reference Drake, Swisdak, Che and Shay2006; Giannios et al. Reference Giannios, Uzdensky and Begelman2010; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Li, Daughton and Liu2014, Reference Guo, Liu, Daughton and Li2015; Dahlin, Drake & Swisdak Reference Dahlin, Drake and Swisdak2014; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Guo, Daughton, Li and Li2021; French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Guo, Daughton, Li, Le, Phan and Desai2024), parallel electric field acceleration in the exhaust region (Egedal & Daughton Reference Egedal and Daughton2013; Zhang, Drake & Swisdak Reference Zhang, Drake and Swisdak2019) and acceleration by the pickup process in the exhaust region (Drake et al. Reference Drake, Cassak, Shay, Swisdak and Quataert2009; Sironi & Beloborodov Reference Sironi and Beloborodov2020; Chernoglazov, Hakobyan & Philippov Reference Chernoglazov, Hakobyan and Philippov2023; French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023). Previous work on particle injection in magnetic reconnection has included studies in the transrelativistic regime for a proton–electron plasma with a weak guide field (Ball et al. Reference Ball, Sironi and Özel2019; Kilian et al. Reference Kilian, Li, Guo and Zhang2020) and relativistic pair plasmas for various guide-field strengths (Sironi Reference Sironi2022; French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Li, French, Zhang, Daughton, Liu, Matthaeus, Kilian, Johnson and Li2023; Totorica et al. Reference Totorica, Zenitani, Matsukiyo, Machida, Sekiguchi and Bhattacharjee2023) and upstream magnetisations (Sironi Reference Sironi2022; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Li, French, Zhang, Daughton, Liu, Matthaeus, Kilian, Johnson and Li2023; Totorica et al. Reference Totorica, Zenitani, Matsukiyo, Machida, Sekiguchi and Bhattacharjee2023; Gupta et al. Reference Gupta, Sridhar and Sironi2025).

However, these studies have not elucidated several important aspects of injection, such as how the injection stage in relativistic magnetic reconnection is influenced by the upstream magnetisation and three-dimensional (3-D) effects. Addressing this key question is the subject of this paper. We achieve this using analytical theory and fully kinetic 2-D and 3-D PIC simulations of relativistic magnetic reconnection in non-radiative collisionless pair plasmas. To uncover spectral quantities, most importantly the injection energy

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

, we run a spectral fitting procedure that is improved from our previous work (French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023). To uncover the relative contributions of different injection mechanisms, we employ a methodology similar to French et al. (Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023), wherein we consider several mechanisms, namely, parallel electric fields near X-points, Fermi kicks by the motional electric field and the pickup process.

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

, we run a spectral fitting procedure that is improved from our previous work (French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023). To uncover the relative contributions of different injection mechanisms, we employ a methodology similar to French et al. (Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023), wherein we consider several mechanisms, namely, parallel electric fields near X-points, Fermi kicks by the motional electric field and the pickup process.

Throughout this paper, we use the units

![]() $m_e = c = 1$

. That is, we normalise velocities to the speed of light

$m_e = c = 1$

. That is, we normalise velocities to the speed of light

![]() $c$

, momenta to

$c$

, momenta to

![]() $m_e c$

and energies to the electron rest energy

$m_e c$

and energies to the electron rest energy

![]() $m_e c^2$

. Furthermore, we denote

$m_e c^2$

. Furthermore, we denote

![]() $\gamma$

as the energy of a single particle,

$\gamma$

as the energy of a single particle,

![]() $E$

as the sum or integral of energies of multiple particles, and

$E$

as the sum or integral of energies of multiple particles, and

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}$

as the particle 3-velocity in the simulation frame. Primed vector quantities, such as the velocity

$\boldsymbol{v}$

as the particle 3-velocity in the simulation frame. Primed vector quantities, such as the velocity

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}'$

or the momentum

$\boldsymbol{v}'$

or the momentum

![]() $\boldsymbol{p}' \equiv \gamma ' \boldsymbol{v}'$

, denote a Lorentz boost to the

$\boldsymbol{p}' \equiv \gamma ' \boldsymbol{v}'$

, denote a Lorentz boost to the

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}_E \equiv \boldsymbol{E} \times \boldsymbol{B}/B^2$

drift-velocity frame, where

$\boldsymbol{v}_E \equiv \boldsymbol{E} \times \boldsymbol{B}/B^2$

drift-velocity frame, where

![]() $\boldsymbol{E}$

and

$\boldsymbol{E}$

and

![]() $\boldsymbol{B}$

respectively denote the electric and magnetic field vectors. This is done to eliminate the context of bulk plasma motions. Primed scalar quantities denote those whose vector inputs are primed, e.g.

$\boldsymbol{B}$

respectively denote the electric and magnetic field vectors. This is done to eliminate the context of bulk plasma motions. Primed scalar quantities denote those whose vector inputs are primed, e.g.

![]() $\gamma ' \equiv (1 - \boldsymbol{v}' \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v}')^{-1/2}$

. Subscripts

$\gamma ' \equiv (1 - \boldsymbol{v}' \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{v}')^{-1/2}$

. Subscripts

![]() $\parallel , \perp$

indicate components relative to the local magnetic field in the laboratory frame (

$\parallel , \perp$

indicate components relative to the local magnetic field in the laboratory frame (

![]() $E \times B$

drift-velocity frame) if the quantity is not primed (primed). Lastly, we reference four dimensionless quantities used throughout this paper: the cold upstream magnetisation

$E \times B$

drift-velocity frame) if the quantity is not primed (primed). Lastly, we reference four dimensionless quantities used throughout this paper: the cold upstream magnetisation

corresponding to the average magnetic energy per particle rest mass energy (where

![]() $B_0$

is the ambient upstream magnetic field and

$B_0$

is the ambient upstream magnetic field and

![]() $n \equiv n_i + n_e$

is the total upstream plasma density), the hot upstream magnetisation

$n \equiv n_i + n_e$

is the total upstream plasma density), the hot upstream magnetisation

where

![]() $h$

is the relativistic plasma enthalpy density, the ambient upstream temperature normalised by particle rest mass energy

$h$

is the relativistic plasma enthalpy density, the ambient upstream temperature normalised by particle rest mass energy

and the normalised guide-field strength

where

![]() $B_g$

is the `guide magnetic field,’ a uniform, non-reversing component of the magnetic field that orients out of plane.

$B_g$

is the `guide magnetic field,’ a uniform, non-reversing component of the magnetic field that orients out of plane.

The rest of this paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents our theoretical picture of particle injection. Section 3 describes the set-up for the simulations. Section 4 contains the analysis and results from each simulation. Section 5 discusses comparisons with previous work and outlooks for future work. Section 6 presents our main conclusions.

2. Theoretical picture of particle injection

In concordance with our overview in § 1, our picture of particle injection in relativistic magnetic reconnection has two components. The first is an analytical model for the injection energy

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

(§ 2.1). The second is a detailed description of each mechanism that injects particles (§ 2.2).

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

(§ 2.1). The second is a detailed description of each mechanism that injects particles (§ 2.2).

2.1. Injection criterion

Suppose the criterion for a particle to be ‘injected’, regardless of the mechanism of injection, is that its gyroradius

![]() $r_g$

exceeds the reconnection layer half-thickness at the X-point

$r_g$

exceeds the reconnection layer half-thickness at the X-point

![]() $\delta /2$

, i.e.

$\delta /2$

, i.e.

![]() $r_g \geqslant \delta /2 \implies \gamma \geqslant \gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

(Speiser Reference Speiser1965; Giannios et al. Reference Giannios, Uzdensky and Begelman2010). This criterion ensures that a gyrating particle centred on the X-point spends some fraction of each orbit outside the layer, which causes it to adopt a meandering Speiser trajectory. It follows that a newly injected particle will satisfy

$r_g \geqslant \delta /2 \implies \gamma \geqslant \gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

(Speiser Reference Speiser1965; Giannios et al. Reference Giannios, Uzdensky and Begelman2010). This criterion ensures that a gyrating particle centred on the X-point spends some fraction of each orbit outside the layer, which causes it to adopt a meandering Speiser trajectory. It follows that a newly injected particle will satisfy

where

![]() $\omega _{\textrm {ce}} \equiv eB_0/m_e c$

is the nominal electron gyrofrequency defined with the upstream magnetic field

$\omega _{\textrm {ce}} \equiv eB_0/m_e c$

is the nominal electron gyrofrequency defined with the upstream magnetic field

![]() $B_0$

and

$B_0$

and

![]() $\rho _0 \equiv c/\omega _{\textrm {ce}} = m_e c^2/eB_0$

is the corresponding nominal relativistic gyroradius. In (2.1) we have ignored pitch angle corrections and assumed

$\rho _0 \equiv c/\omega _{\textrm {ce}} = m_e c^2/eB_0$

is the corresponding nominal relativistic gyroradius. In (2.1) we have ignored pitch angle corrections and assumed

![]() $v_\perp \simeq c$

.

$v_\perp \simeq c$

.

Our next task is to estimate the layer thickness

![]() $\delta$

at the X-point. We shall take

$\delta$

at the X-point. We shall take

![]() $\delta \simeq d_{\textrm {e, rel}}$

, where

$\delta \simeq d_{\textrm {e, rel}}$

, where

![]() $d_{\textrm {e, rel}}$

is the relativistic collisionless electron skin depth inside the layer, and assume that the electron density in the layer is comparable to the ambient upstream electron density

$d_{\textrm {e, rel}}$

is the relativistic collisionless electron skin depth inside the layer, and assume that the electron density in the layer is comparable to the ambient upstream electron density

![]() $n_e$

. Additionally, we assume that the velocity distribution is isotropic in the layer. Then,

$n_e$

. Additionally, we assume that the velocity distribution is isotropic in the layer. Then,

where

![]() $\omega _{\textrm {pe}} \equiv [ 4\pi n_e e^2 / m_e ]^{1/2}$

is the corresponding electron plasma frequency and

$\omega _{\textrm {pe}} \equiv [ 4\pi n_e e^2 / m_e ]^{1/2}$

is the corresponding electron plasma frequency and

![]() $\varGamma$

is the mean Lorentz factor of electrons in the layer.

$\varGamma$

is the mean Lorentz factor of electrons in the layer.

Substituting (2.3) into (2.2), we obtain

where for a pair plasma

![]() $\sigma = \sigma _e/2 = \omega _{\textrm {ce}}^2/(2\omega _{\textrm {pe}}^2)$

is the upstream magnetisation.

$\sigma = \sigma _e/2 = \omega _{\textrm {ce}}^2/(2\omega _{\textrm {pe}}^2)$

is the upstream magnetisation.

The remaining task is to model

![]() $\varGamma$

, which can be represented as the sum of two contributions

$\varGamma$

, which can be represented as the sum of two contributions

where

![]() $\varGamma _{\textrm {up}}$

is the average Lorentz factor of particles arriving from the upstream and

$\varGamma _{\textrm {up}}$

is the average Lorentz factor of particles arriving from the upstream and

![]() $\langle W \rangle$

is the average work done to particles while they are in the layer. If the upstream particle distribution is thermal, then

$\langle W \rangle$

is the average work done to particles while they are in the layer. If the upstream particle distribution is thermal, then

![]() $\varGamma _{\textrm {up}} = \varGamma _{\textrm {th}} = K_3(1/\theta _0)/K_2(1/\theta _0)$

, where

$\varGamma _{\textrm {up}} = \varGamma _{\textrm {th}} = K_3(1/\theta _0)/K_2(1/\theta _0)$

, where

![]() $\varGamma _{\textrm {th}} = K_3(1/\theta _0)/K_2(1/\theta _0)$

is the ‘thermal Lorentz factor’, i.e. the average energy of electrons in a Maxwell–Jüttner distribution of upstream temperature

$\varGamma _{\textrm {th}} = K_3(1/\theta _0)/K_2(1/\theta _0)$

is the ‘thermal Lorentz factor’, i.e. the average energy of electrons in a Maxwell–Jüttner distribution of upstream temperature

![]() $\theta _0 \equiv k_B T_0/m_e c^2$

.

$\theta _0 \equiv k_B T_0/m_e c^2$

.

Meanwhile,

![]() $\langle W \rangle$

can generally be written

$\langle W \rangle$

can generally be written

![]() $\langle W \rangle = k\sigma m_ec^2$

, where one expects the dimensionless coefficient

$\langle W \rangle = k\sigma m_ec^2$

, where one expects the dimensionless coefficient

![]() $k\gt 0$

to be a constant independent of

$k\gt 0$

to be a constant independent of

![]() $\sigma$

. We may constrain

$\sigma$

. We may constrain

![]() $k$

as follows. First,

$k$

as follows. First,

![]() $U_B = B_0^2/8\pi$

implies that the available magnetic energy per particle is

$U_B = B_0^2/8\pi$

implies that the available magnetic energy per particle is

![]() $U_B/n = B_0^2/(8\pi n) = (\sigma /2) m_e c^2$

. Second, assuming that the efficiency of energy conversion is

$U_B/n = B_0^2/(8\pi n) = (\sigma /2) m_e c^2$

. Second, assuming that the efficiency of energy conversion is

![]() ${\sim} 50\,\%$

, the average dissipated magnetic energy per particle is

${\sim} 50\,\%$

, the average dissipated magnetic energy per particle is

![]() ${\simeq} (\sigma /4) m_ec^2$

. Third, since the particles are energised partially as they enter the current sheet and partially as they exit the current sheet (e.g. by magnetic tension release in the outwards-accelerating plasma), we may assume that the average dissipated magnetic energy per particle that exists in the current sheet is

${\simeq} (\sigma /4) m_ec^2$

. Third, since the particles are energised partially as they enter the current sheet and partially as they exit the current sheet (e.g. by magnetic tension release in the outwards-accelerating plasma), we may assume that the average dissipated magnetic energy per particle that exists in the current sheet is

![]() $\lesssim (\sigma /8) m_ec^2$

. This gives a constraint of

$\lesssim (\sigma /8) m_ec^2$

. This gives a constraint of

![]() $k \lesssim 1/8$

. We stress that, while the exact value of

$k \lesssim 1/8$

. We stress that, while the exact value of

![]() $k$

is uncertain, the above argument allows us to treat

$k$

is uncertain, the above argument allows us to treat

![]() $k$

as a small parameter. Accordingly, we shall retain

$k$

as a small parameter. Accordingly, we shall retain

![]() $k$

in the rest of this subsection.

$k$

in the rest of this subsection.

We can now write (2.5) as

where we approximate

![]() $\sigma _h \simeq \sigma /\varGamma _{\textrm {th}}$

. We see that there are two distinct relativistic (

$\sigma _h \simeq \sigma /\varGamma _{\textrm {th}}$

. We see that there are two distinct relativistic (

![]() $\sigma _h \gg 1$

) regimes based on which of the two terms in (2.6) dominates, i.e. how

$\sigma _h \gg 1$

) regimes based on which of the two terms in (2.6) dominates, i.e. how

![]() $\sigma _h$

compares with

$\sigma _h$

compares with

![]() $k^{-1}$

:

$k^{-1}$

:

-

(i) Thermally dominated regime

$1 \lesssim \sigma _h \lesssim k^{-1}$

. In this moderate-magnetisation case (covering

$1 \lesssim \sigma _h \lesssim k^{-1}$

. In this moderate-magnetisation case (covering

$\gtrsim 1$

decade in

$\gtrsim 1$

decade in

$\sigma _h$

), the average particle energy in layer is

$\sigma _h$

), the average particle energy in layer is

$\varGamma \simeq \varGamma _{\textrm {th}}$

, i.e. inherited from the thermal upstream and not controlled by

$\varGamma \simeq \varGamma _{\textrm {th}}$

, i.e. inherited from the thermal upstream and not controlled by

$\sigma$

or reconnection. In this regime, the upstream plasma conditions fully govern the layer thickness and partially govern the injection energy

$\sigma$

or reconnection. In this regime, the upstream plasma conditions fully govern the layer thickness and partially govern the injection energy

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

. In particular, the injection energy according to (2.4) becomes(2.7)In particular,

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

. In particular, the injection energy according to (2.4) becomes(2.7)In particular, \begin{equation} \gamma _{\textrm {inj}} \simeq \sigma \sqrt {\sigma _h^{-1} \, (1 + b_g^2)/2}. \end{equation}

(2.8)

\begin{equation} \gamma _{\textrm {inj}} \simeq \sigma \sqrt {\sigma _h^{-1} \, (1 + b_g^2)/2}. \end{equation}

(2.8) \begin{equation} \gamma _{\textrm {inj}} \simeq \begin{cases} \sqrt {\sigma (1 + b_g^2)/2}, & \theta \ll 1, \\ \sqrt {\varGamma _{\textrm {th}} \sigma (1 + b_g^2)/2}, & \theta \gg 1 .\end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \gamma _{\textrm {inj}} \simeq \begin{cases} \sqrt {\sigma (1 + b_g^2)/2}, & \theta \ll 1, \\ \sqrt {\varGamma _{\textrm {th}} \sigma (1 + b_g^2)/2}, & \theta \gg 1 .\end{cases} \end{equation}

-

(ii) Magnetically dominated regime

$\sigma _h \gg k^{-1}$

. In this case, the average particle energy in the layer

$\sigma _h \gg k^{-1}$

. In this case, the average particle energy in the layer

$\varGamma$

is dominated by

$\varGamma$

is dominated by

$\langle W \rangle /m_e c^2$

and upstream contributions can be ignored. Hence (2.4) becomes(2.9)

$\langle W \rangle /m_e c^2$

and upstream contributions can be ignored. Hence (2.4) becomes(2.9) \begin{equation} \gamma _{\textrm {inj}} \simeq \sigma \sqrt {k (1 + b_g^2)/2}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \gamma _{\textrm {inj}} \simeq \sigma \sqrt {k (1 + b_g^2)/2}. \end{equation}

There are several implications for the resulting dynamic range of the power-law spectrum. Assuming that

![]() $\gamma _c = C \sigma$

(Werner et al. Reference Werner, Uzdensky, Cerutti, Nalewajko and Begelman2016), one expects

$\gamma _c = C \sigma$

(Werner et al. Reference Werner, Uzdensky, Cerutti, Nalewajko and Begelman2016), one expects

\begin{equation} R \equiv \gamma _c/\gamma _{\textrm {inj}} \simeq \begin{cases} \sqrt {2}C \, \sigma _h^{1/2} \left [ 1 + b_g^2 \right ]^{-1/2} & 1 \lesssim \sigma _h \lesssim k^{-1} ,\\ \sqrt {2}C \, k^{-1/2} \left [ 1 + b_g^2 \right ]^{-1/2} & \sigma _h \gg k^{-1}. \\ \end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} R \equiv \gamma _c/\gamma _{\textrm {inj}} \simeq \begin{cases} \sqrt {2}C \, \sigma _h^{1/2} \left [ 1 + b_g^2 \right ]^{-1/2} & 1 \lesssim \sigma _h \lesssim k^{-1} ,\\ \sqrt {2}C \, k^{-1/2} \left [ 1 + b_g^2 \right ]^{-1/2} & \sigma _h \gg k^{-1}. \\ \end{cases} \end{equation}

In this model, the explicit guide-field dependence of

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}(b_g) \propto \sqrt {1 + b_g^2}$

is owed to stronger magnetic fields decreasing the particle gyroradius, resulting in a greater energy necessary to satisfy

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}(b_g) \propto \sqrt {1 + b_g^2}$

is owed to stronger magnetic fields decreasing the particle gyroradius, resulting in a greater energy necessary to satisfy

![]() $r_g \geqslant \delta /2$

. There could also be an implicit guide-field dependence if the layer thickness depends on guide-field strength. This is plausible because a strong guide field can prolong the duration over which particles remain in the X-point, causing

$r_g \geqslant \delta /2$

. There could also be an implicit guide-field dependence if the layer thickness depends on guide-field strength. This is plausible because a strong guide field can prolong the duration over which particles remain in the X-point, causing

![]() $k$

to increase. Nevertheless, as we shall find in § 5.1, the scaling

$k$

to increase. Nevertheless, as we shall find in § 5.1, the scaling

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}(b_g) \propto \sqrt {1 + b_g^2}$

is in rough agreement with French et al. (Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023).

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}(b_g) \propto \sqrt {1 + b_g^2}$

is in rough agreement with French et al. (Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023).

2.2. Injection mechanisms

In our first paper (French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023), we stipulated that particles can be injected only as they transition from upstream to downstream, i.e. as they cross or interact with the magnetic separatrix between these two regions. Applying this assumption in the context of a reconnection layer has led to the identification of the following three injection mechanisms (French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023), illustrated in figure 1.

Figure 1. Cartoons of several particle injection mechanisms, adapted from French et al. (Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023). In each panel,

![]() $B_0$

is the reconnecting magnetic field,

$B_0$

is the reconnecting magnetic field,

![]() $E_{\textrm {rec}}$

is the reconnection electric field and

$E_{\textrm {rec}}$

is the reconnection electric field and

![]() $v_{\textrm {out}}$

is the reconnection outflow speed. (a) Injection by direct acceleration from the reconnection electric field near an X-point. (b) Injection by a Fermi `kick.’ (c) Injection by the pickup process, wherein

$v_{\textrm {out}}$

is the reconnection outflow speed. (a) Injection by direct acceleration from the reconnection electric field near an X-point. (b) Injection by a Fermi `kick.’ (c) Injection by the pickup process, wherein

![]() $\lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\perp '\rvert$

suddenly increases upon crossing the separatrix and subsequent entry into the downstream region.

$\lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\perp '\rvert$

suddenly increases upon crossing the separatrix and subsequent entry into the downstream region.

-

(a) Direct acceleration: incoming particles are accelerated directly by the reconnection electric field

$E_{\textrm {rec}}$

in microscopic diffusion regions around magnetic X-points (figure 1

a). When immersed in

$E_{\textrm {rec}}$

in microscopic diffusion regions around magnetic X-points (figure 1

a). When immersed in

$E_{\textrm {rec}}$

, charged particles gain energy at a rate of

$E_{\textrm {rec}}$

, charged particles gain energy at a rate of

$\dot {W}_{\textrm {direct}} = ( \eta _{\textrm {rec}} \beta _A \omega _{\textrm {ce}}) m_e c^2$

, where

$\dot {W}_{\textrm {direct}} = ( \eta _{\textrm {rec}} \beta _A \omega _{\textrm {ce}}) m_e c^2$

, where

$\eta _{\textrm {rec}} \beta _A \equiv E_{\textrm {rec}}/B_0 \simeq 0.1$

(when the guide magnetic field is weak) is the reconnection rate normalised by the speed of light, where

$\eta _{\textrm {rec}} \beta _A \equiv E_{\textrm {rec}}/B_0 \simeq 0.1$

(when the guide magnetic field is weak) is the reconnection rate normalised by the speed of light, where

$\beta _A \equiv [ \sigma _h/(1+\sigma _h) ]^{1/2} \simeq [ \sigma /(1+\sigma ) ]^{1/2}$

is the dimensionless upstream Alfvén speed (provided the upstream plasma is relativistically cold, i.e.

$\beta _A \equiv [ \sigma _h/(1+\sigma _h) ]^{1/2} \simeq [ \sigma /(1+\sigma ) ]^{1/2}$

is the dimensionless upstream Alfvén speed (provided the upstream plasma is relativistically cold, i.e.

$\theta _0 \equiv k_B T_0 / m_e c^2 \ll 1$

) and

$\theta _0 \equiv k_B T_0 / m_e c^2 \ll 1$

) and

$\omega _{\textrm {ce}} \equiv eB_0/m_ec$

. Hence(2.11)If a guide field

$\omega _{\textrm {ce}} \equiv eB_0/m_ec$

. Hence(2.11)If a guide field \begin{equation} W_{\textrm {direct}}/m_ec^2 = \eta _{\textrm {rec}} \beta _A \big ( \omega _{\textrm {ce}} \Delta t\big ) \simeq 0.1 \, \omega _{\textrm {ce}} \Delta t. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} W_{\textrm {direct}}/m_ec^2 = \eta _{\textrm {rec}} \beta _A \big ( \omega _{\textrm {ce}} \Delta t\big ) \simeq 0.1 \, \omega _{\textrm {ce}} \Delta t. \end{equation}

$b_g \equiv B_g/B_0 \gtrsim \eta _{\textrm {rec}} \simeq 0.1$

is present, then

$b_g \equiv B_g/B_0 \gtrsim \eta _{\textrm {rec}} \simeq 0.1$

is present, then

$E_{\textrm {rec}}$

is well approximated by the parallel electric field

$E_{\textrm {rec}}$

is well approximated by the parallel electric field

$\lvert \boldsymbol{E}_\parallel \rvert \equiv (\boldsymbol{E} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{B}) /\lvert \boldsymbol{B} \rvert$

at the X-point where the in-plane magnetic field vanishes. In this case, particles gain significant parallel momentum

$\lvert \boldsymbol{E}_\parallel \rvert \equiv (\boldsymbol{E} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{B}) /\lvert \boldsymbol{B} \rvert$

at the X-point where the in-plane magnetic field vanishes. In this case, particles gain significant parallel momentum

$\boldsymbol{p}'_\parallel \equiv \gamma ' \boldsymbol{v}'_\parallel = \gamma \boldsymbol{v}_\parallel = \gamma (\boldsymbol{v} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{B}) \boldsymbol{B}/\lvert \boldsymbol{B} \rvert ^2$

.

$\boldsymbol{p}'_\parallel \equiv \gamma ' \boldsymbol{v}'_\parallel = \gamma \boldsymbol{v}_\parallel = \gamma (\boldsymbol{v} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{B}) \boldsymbol{B}/\lvert \boldsymbol{B} \rvert ^2$

.

-

(b) Fermi kick: the relaxation of freshly reconnected magnetic field-line tension gives rise to a Fermi acceleration process wherein the local curvature drift velocity

$\boldsymbol{v}_C$

of particles is aligned with the motional electric field of ideal magnetohydrodynamics (MHD)

$\boldsymbol{v}_C$

of particles is aligned with the motional electric field of ideal magnetohydrodynamics (MHD)

$\boldsymbol{E}_m = - \boldsymbol{u} \times \boldsymbol{B}$

associated with the rapid advection of the newly reconnected magnetic field lines (Drake et al. Reference Drake, Swisdak, Che and Shay2006; Dahlin et al. Reference Dahlin, Drake and Swisdak2014; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Li, Daughton and Liu2014; Li et al. Reference Li, Guo, Li and Li2018; Kilian et al. Reference Kilian, Li, Guo and Zhang2020; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Guo, Daughton, Li and Li2021; French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023; Majeski & Ji Reference Majeski and Ji2023; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Guo, Daughton, Li, Le, Phan and Desai2024). This mechanism is illustrated in figure 1(b).

$\boldsymbol{E}_m = - \boldsymbol{u} \times \boldsymbol{B}$

associated with the rapid advection of the newly reconnected magnetic field lines (Drake et al. Reference Drake, Swisdak, Che and Shay2006; Dahlin et al. Reference Dahlin, Drake and Swisdak2014; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Li, Daughton and Liu2014; Li et al. Reference Li, Guo, Li and Li2018; Kilian et al. Reference Kilian, Li, Guo and Zhang2020; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Guo, Daughton, Li and Li2021; French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023; Majeski & Ji Reference Majeski and Ji2023; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Guo, Daughton, Li, Le, Phan and Desai2024). This mechanism is illustrated in figure 1(b).Consequently, an incoming particle experiences one Fermi reflection (or ‘kick’, i.e. one half-cycle of a continual Fermi process) that flips its direction in the

$E \times B$

drift frame. If the Fermi kick is treated as a 1-D collision, then the net energy gain is obtained by considering the particle’s initial velocity in the outflow (i.e.

$E \times B$

drift frame. If the Fermi kick is treated as a 1-D collision, then the net energy gain is obtained by considering the particle’s initial velocity in the outflow (i.e.

$E \times B$

-drift) frame projected onto the outflow direction,

$E \times B$

-drift) frame projected onto the outflow direction,

$\beta _i'$

, negating it (i.e.

$\beta _i'$

, negating it (i.e.

$\beta _f' = -\beta _i'$

), and boosting back to the simulation frame. Assuming that the outflow speed is the in-plane Alfvén speed, the result is a velocity gain of(2.12)where

$\beta _f' = -\beta _i'$

), and boosting back to the simulation frame. Assuming that the outflow speed is the in-plane Alfvén speed, the result is a velocity gain of(2.12)where \begin{align} \Delta \beta \equiv \beta _f - \beta _i = \frac {2\beta _{\textrm {Ax}} \big [ 1 + \beta _i^2 \big ] - 2\beta _i \big [ 1 + \beta _{\textrm {Ax}}^2 \big ]}{ \big [ 1 + \beta _{\textrm {Ax}}^2 \big ] -2 \beta _i \beta _{\textrm {Ax}} }, \end{align}

\begin{align} \Delta \beta \equiv \beta _f - \beta _i = \frac {2\beta _{\textrm {Ax}} \big [ 1 + \beta _i^2 \big ] - 2\beta _i \big [ 1 + \beta _{\textrm {Ax}}^2 \big ]}{ \big [ 1 + \beta _{\textrm {Ax}}^2 \big ] -2 \beta _i \beta _{\textrm {Ax}} }, \end{align}

$\beta _j \equiv v_j/c$

for any subscript

$\beta _j \equiv v_j/c$

for any subscript

$j$

and

$j$

and

$\beta _{\textrm {Ax}}$

is the in-plane Alfvén speed

$\beta _{\textrm {Ax}}$

is the in-plane Alfvén speed

$\beta _{\textrm {Ax}} = [ \sigma /[1 + \sigma (1 + b_g^2)] ]^{1/2}$

. As

$\beta _{\textrm {Ax}} = [ \sigma /[1 + \sigma (1 + b_g^2)] ]^{1/2}$

. As

$\beta _i \to 0$

(i.e. for particles with initial velocity nearly perpendicular to the outflow), the resulting energy gain becomes(2.13)Hence a strong guide field (i.e.

$\beta _i \to 0$

(i.e. for particles with initial velocity nearly perpendicular to the outflow), the resulting energy gain becomes(2.13)Hence a strong guide field (i.e. \begin{equation} W_{\textrm {Fermi}}/m_ec^2 = \lim _{\beta _i \to 0} \big ( 1 - (\Delta \beta )^2 \big )^{-1/2} - 1 = \frac {1 + \beta _{\textrm {Ax}}^2}{1 - \beta _{\textrm {Ax}}^2} - 1 = \frac {2\sigma }{1 + \sigma b_g^2}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} W_{\textrm {Fermi}}/m_ec^2 = \lim _{\beta _i \to 0} \big ( 1 - (\Delta \beta )^2 \big )^{-1/2} - 1 = \frac {1 + \beta _{\textrm {Ax}}^2}{1 - \beta _{\textrm {Ax}}^2} - 1 = \frac {2\sigma }{1 + \sigma b_g^2}. \end{equation}

$b_g \gg \sigma ^{-1/2}$

) significantly damps Fermi kicks, resulting in an energisation of

$b_g \gg \sigma ^{-1/2}$

) significantly damps Fermi kicks, resulting in an energisation of

$W_{\textrm {Fermi}} \simeq 2 b_g^{-2} \ll 2\sigma$

. Conversely, a weak guide field (

$W_{\textrm {Fermi}} \simeq 2 b_g^{-2} \ll 2\sigma$

. Conversely, a weak guide field (

$b_g \ll \sigma ^{-1/2}$

) allows efficient energisation with

$b_g \ll \sigma ^{-1/2}$

) allows efficient energisation with

$W_{\textrm {Fermi}} \simeq 2\sigma$

.

$W_{\textrm {Fermi}} \simeq 2\sigma$

.

-

(c) Pickup acceleration: an incoming upstream particle crosses the reconnection separatrix suddenly and thus (i) the particle’s magnetic moment in the outflow frame

$\mu ' \equiv \gamma ' \lvert \boldsymbol{p}'_\perp \rvert ^2 / 2 \lvert \boldsymbol{B}' \rvert$

is no longer constant, resulting in a greater perpendicular momentum

$\mu ' \equiv \gamma ' \lvert \boldsymbol{p}'_\perp \rvert ^2 / 2 \lvert \boldsymbol{B}' \rvert$

is no longer constant, resulting in a greater perpendicular momentum

$\lvert \boldsymbol{p}'_\perp \rvert$

and (ii) the particle becomes immersed in a reconnection outflow with bulk (

$\lvert \boldsymbol{p}'_\perp \rvert$

and (ii) the particle becomes immersed in a reconnection outflow with bulk (

$E\times B$

-drift) velocity of

$E\times B$

-drift) velocity of

$v_{\textrm {out}} \sim v_{\textrm {Ax}}$

. The ideal-MHD (i.e. motional) electric field

$v_{\textrm {out}} \sim v_{\textrm {Ax}}$

. The ideal-MHD (i.e. motional) electric field

$\boldsymbol{E}_m \equiv - \boldsymbol{u} \times \boldsymbol{B}$

subsequently accelerates the particle until its perpendicular guiding-centre velocity matches the

$\boldsymbol{E}_m \equiv - \boldsymbol{u} \times \boldsymbol{B}$

subsequently accelerates the particle until its perpendicular guiding-centre velocity matches the

$E \times B$

-drift velocity of the outflow (figure 1

c) (Drake et al. Reference Drake, Cassak, Shay, Swisdak and Quataert2009; Chernoglazov et al. Reference Chernoglazov, Hakobyan and Philippov2023; French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023). Thus the total work done by this pickup mechanism on a particle of initial energy

$E \times B$

-drift velocity of the outflow (figure 1

c) (Drake et al. Reference Drake, Cassak, Shay, Swisdak and Quataert2009; Chernoglazov et al. Reference Chernoglazov, Hakobyan and Philippov2023; French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023). Thus the total work done by this pickup mechanism on a particle of initial energy

$\gamma _0$

is(2.14)where

$\gamma _0$

is(2.14)where \begin{equation} W_{\textrm {pickup}}/m_ec^2 \equiv \gamma _{\textrm {Ax}} - \gamma _0 = \sqrt {1 + \frac {\sigma }{1 + \sigma b_g^2}} - \gamma _0, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} W_{\textrm {pickup}}/m_ec^2 \equiv \gamma _{\textrm {Ax}} - \gamma _0 = \sqrt {1 + \frac {\sigma }{1 + \sigma b_g^2}} - \gamma _0, \end{equation}

$\gamma _{\textrm {Ax}} = ( 1 - \beta _{\textrm {Ax}}^2)^{-1/2}$

.

$\gamma _{\textrm {Ax}} = ( 1 - \beta _{\textrm {Ax}}^2)^{-1/2}$

.

Several strategies have been employed in the literature to disentangle the energetic contribution of each mechanism to particle energisation. One common approach utilises the motional (i.e. ideal) electric field

![]() $\boldsymbol{E}_m$

and the non-ideal electric field

$\boldsymbol{E}_m$

and the non-ideal electric field

![]() $\boldsymbol{E}_n \equiv \boldsymbol{E} - \boldsymbol{E}_m$

by approximating

$\boldsymbol{E}_n \equiv \boldsymbol{E} - \boldsymbol{E}_m$

by approximating

![]() $\boldsymbol{E}_n$

as the electric field component parallel to the local magnetic field,

$\boldsymbol{E}_n$

as the electric field component parallel to the local magnetic field,

![]() $\boldsymbol{E}_n \simeq \boldsymbol{E}_\parallel \equiv (\boldsymbol{E} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{B})\boldsymbol{B}/\lvert \boldsymbol{B} \rvert ^2$

, and

$\boldsymbol{E}_n \simeq \boldsymbol{E}_\parallel \equiv (\boldsymbol{E} \boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{B})\boldsymbol{B}/\lvert \boldsymbol{B} \rvert ^2$

, and

![]() $\boldsymbol{E}_m$

as the perpendicular component,

$\boldsymbol{E}_m$

as the perpendicular component,

![]() $\boldsymbol{E}_m \simeq \boldsymbol{E}_\perp \equiv \boldsymbol{E} - \boldsymbol{E}_\parallel$

; one then compares the works

$\boldsymbol{E}_m \simeq \boldsymbol{E}_\perp \equiv \boldsymbol{E} - \boldsymbol{E}_\parallel$

; one then compares the works

![]() $W_\parallel$

and

$W_\parallel$

and

![]() $W_\perp$

done by these electric-field components over a statistically large ensemble of tracer particles (Comisso & Sironi Reference Comisso and Sironi2019; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Li, Daughton, Kilian, Li, Liu, Yan and Ma2019; Kilian et al. Reference Kilian, Li, Guo and Zhang2020; French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023). Since the value of the normalised guide-field strength adopted in our present study,

$W_\perp$

done by these electric-field components over a statistically large ensemble of tracer particles (Comisso & Sironi Reference Comisso and Sironi2019; Guo et al. Reference Guo, Li, Daughton, Kilian, Li, Liu, Yan and Ma2019; Kilian et al. Reference Kilian, Li, Guo and Zhang2020; French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023). Since the value of the normalised guide-field strength adopted in our present study,

![]() $b_g = 0.3$

, exceeds the dimensionless reconnection rate

$b_g = 0.3$

, exceeds the dimensionless reconnection rate

![]() $\eta _{\textrm {rec}} \simeq 0.1$

(Guo et al. Reference Guo, Liu, Daughton and Li2015; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Guo, Daughton, Li and Hesse2015, Reference Liu, Hesse, Guo, Daughton, Li, Cassak and Shay2017; Werner et al. Reference Werner, Uzdensky, Begelman, Cerutti and Nalewajko2018; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Lin, Hesse, Guo, Li, Zhang and Peery2020; Goodbred & Liu Reference Goodbred and Liu2022; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Sironi, Giannios and Petropoulou2023), which quantifies the typical strength of the downstream reconnected in-plane magnetic field relative to the upstream reconnecting magnetic field, we shall proceed with this approximation.

$\eta _{\textrm {rec}} \simeq 0.1$

(Guo et al. Reference Guo, Liu, Daughton and Li2015; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Guo, Daughton, Li and Hesse2015, Reference Liu, Hesse, Guo, Daughton, Li, Cassak and Shay2017; Werner et al. Reference Werner, Uzdensky, Begelman, Cerutti and Nalewajko2018; Liu et al. Reference Liu, Lin, Hesse, Guo, Li, Zhang and Peery2020; Goodbred & Liu Reference Goodbred and Liu2022; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Sironi, Giannios and Petropoulou2023), which quantifies the typical strength of the downstream reconnected in-plane magnetic field relative to the upstream reconnecting magnetic field, we shall proceed with this approximation.

Thus, in this work we compute the relative contributions of each mechanism to the total injected particle population (i.e. ‘injection shares’) by subjecting each tracer particle in the ensemble to the following scheme (French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023). Upon reaching

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

(i.e. when the particle is ‘injected’), the particle is endowed with its ‘injection time’

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

(i.e. when the particle is ‘injected’), the particle is endowed with its ‘injection time’

![]() $t_{\textrm {inj}} \equiv W^{-1}(\gamma _{\textrm {inj}})$

, where

$t_{\textrm {inj}} \equiv W^{-1}(\gamma _{\textrm {inj}})$

, where

![]() $W(t)$

is the total time-evolved work done to the particle and

$W(t)$

is the total time-evolved work done to the particle and

![]() $W^{-1}(\gamma )$

is its inverse function. Then the particle is assigned to a single mechanism according to whichever of the following conditions is true at

$W^{-1}(\gamma )$

is its inverse function. Then the particle is assigned to a single mechanism according to whichever of the following conditions is true at

![]() $t = t_{\textrm {inj}}$

:

$t = t_{\textrm {inj}}$

:

\begin{equation} \begin{gathered} (W_\parallel \gt W_\perp ) \ \& \ (\lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\parallel \rvert \gt \lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\perp ' \rvert ) \implies \ \text{$E_{\textrm {rec}}$ acceleration}, \\ (W_\perp \gt W_\parallel ) \ \& \ (\lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\parallel \rvert \gt \lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\perp ' \rvert ) \implies \ \text{Fermi kick(s)} ,\\ (W_\perp \gt W_\parallel ) \ \& \ (\lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\perp ' \rvert \gt \lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\parallel \rvert ) \implies \ \text{Pickup process}, \end{gathered} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \begin{gathered} (W_\parallel \gt W_\perp ) \ \& \ (\lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\parallel \rvert \gt \lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\perp ' \rvert ) \implies \ \text{$E_{\textrm {rec}}$ acceleration}, \\ (W_\perp \gt W_\parallel ) \ \& \ (\lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\parallel \rvert \gt \lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\perp ' \rvert ) \implies \ \text{Fermi kick(s)} ,\\ (W_\perp \gt W_\parallel ) \ \& \ (\lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\perp ' \rvert \gt \lvert \boldsymbol{p}_\parallel \rvert ) \implies \ \text{Pickup process}, \end{gathered} \end{equation}

with the remaining possibility categorised as `other.’ Each

![]() $\boldsymbol{p}_\parallel$

is left unprimed because boosting to the

$\boldsymbol{p}_\parallel$

is left unprimed because boosting to the

![]() $E\times B$

-drift frame makes no change to momenta parallel to the local magnetic field.

$E\times B$

-drift frame makes no change to momenta parallel to the local magnetic field.

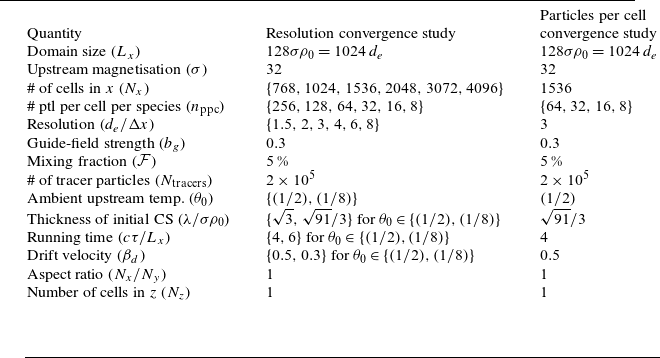

3. Simulation set-up

To study particle injection and acceleration by relativistic magnetic reconnection, we perform an array of fully kinetic simulations of a relativistic collisionless pair plasma using the Zeltron code, which solves the relativistic Vlasov–Maxwell equations (Cerutti et al. Reference Cerutti, Werner, Uzdensky and Begelman2013) in 2-D and 3-D rectangular domains. All of our simulations are initialised with a force-free current sheet (CS) with the associated initial magnetic field

where

![]() $\lambda = \sqrt {3} \, \sigma \rho _0$

is the half-thickness of the initial CS and

$\lambda = \sqrt {3} \, \sigma \rho _0$

is the half-thickness of the initial CS and

![]() $\rho _0 \equiv c/\omega _{\textrm {ce}} = m_e c^2/e B_0$

is the nominal relativistic gyroradius.

$\rho _0 \equiv c/\omega _{\textrm {ce}} = m_e c^2/e B_0$

is the nominal relativistic gyroradius.

The pair mass ratio is

![]() $m_i/m_e = 1$

. The initial plasma density

$m_i/m_e = 1$

. The initial plasma density

![]() $n_0 = n_e + n_i$

is uniform and represented by

$n_0 = n_e + n_i$

is uniform and represented by

![]() $8$

(

$8$

(

![]() $32$

) positron–electron pairs per computational grid cell in three dimensions (two dimensions), as justified in Appendix A. Currents are normalised by

$32$

) positron–electron pairs per computational grid cell in three dimensions (two dimensions), as justified in Appendix A. Currents are normalised by

![]() $J_0 \equiv en_0c/2$

. The initial plasma is thermal with a uniform temperature

$J_0 \equiv en_0c/2$

. The initial plasma is thermal with a uniform temperature

![]() $\theta _0 \equiv T_0/m_ec^2 = 0.3$

. The guide-field strength is set to

$\theta _0 \equiv T_0/m_ec^2 = 0.3$

. The guide-field strength is set to

![]() $b_g = 0.3$

.

$b_g = 0.3$

.

To examine the effects of magnetisation and dimensionality, our simulations vary these quantities independently. In particular, we scan the cold upstream magnetisation parameter over eight values:

![]() $\sigma \in \{8, 12, 16, 24, 32, 48, 64, 96\}$

, where the latter three values are exclusive to two dimensions due to limited computational resources. Since

$\sigma \in \{8, 12, 16, 24, 32, 48, 64, 96\}$

, where the latter three values are exclusive to two dimensions due to limited computational resources. Since

![]() $\theta _0$

is sub-relativistic, these

$\theta _0$

is sub-relativistic, these

![]() $\sigma$

values are close to their corresponding ‘hot’ upstream magnetisations

$\sigma$

values are close to their corresponding ‘hot’ upstream magnetisations

![]() $\sigma _h \simeq \sigma /\varGamma _{\textrm {th}}$

. To examine the effect of dimensionality we compare 2-D and 3-D simulations that are otherwise identical.

$\sigma _h \simeq \sigma /\varGamma _{\textrm {th}}$

. To examine the effect of dimensionality we compare 2-D and 3-D simulations that are otherwise identical.

In this study, we characterise system sizes by the dimensionless measure

![]() $\ell \equiv L/\sigma \rho _0$

, where

$\ell \equiv L/\sigma \rho _0$

, where

![]() $L$

is the system size. The spatial domains of our simulations are rectilinear boxes with

$L$

is the system size. The spatial domains of our simulations are rectilinear boxes with

![]() $x \in [0, \ell _x]$

and

$x \in [0, \ell _x]$

and

![]() $y \in [-\ell _y/2, \ell _y/2]$

, and in three dimensions also with

$y \in [-\ell _y/2, \ell _y/2]$

, and in three dimensions also with

![]() $z \in [0, \ell _z]$

. The aspect ratio is fixed to

$z \in [0, \ell _z]$

. The aspect ratio is fixed to

![]() $\ell _x = \ell _y = 2\ell _z$

(

$\ell _x = \ell _y = 2\ell _z$

(

![]() $\ell _x = \ell _y$

) in three dimensions (two dimensions). To resolve kinetic scales, the spatial resolution is set to

$\ell _x = \ell _y$

) in three dimensions (two dimensions). To resolve kinetic scales, the spatial resolution is set to

![]() $\Delta x = d_e/2$

, as justified in Appendix A (where

$\Delta x = d_e/2$

, as justified in Appendix A (where

![]() $d_e \equiv c/\omega _{\textrm {pe}} = \sqrt {2\sigma } \rho _0$

is the relativistic collisionless electron skin depth). The temporal resolution is set to

$d_e \equiv c/\omega _{\textrm {pe}} = \sqrt {2\sigma } \rho _0$

is the relativistic collisionless electron skin depth). The temporal resolution is set to

![]() $\Delta t = \omega _{\textrm {pe}}^{-1}/6$

. In the

$\Delta t = \omega _{\textrm {pe}}^{-1}/6$

. In the

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $z$

-directions, periodic boundary conditions are set for fields and particles, whereas in the

$z$

-directions, periodic boundary conditions are set for fields and particles, whereas in the

![]() $y$

-direction conducting boundaries are set for fields and reflecting boundaries are set for particles. Instead of adding a small perturbation to trigger magnetic reconnection, we instead wait for the CS to start reconnecting spontaneously.Footnote

1

$y$

-direction conducting boundaries are set for fields and reflecting boundaries are set for particles. Instead of adding a small perturbation to trigger magnetic reconnection, we instead wait for the CS to start reconnecting spontaneously.Footnote

1

The simulation domain size is fixed to

![]() $\ell _x = 256 = 128 \sqrt {2\sigma } \, d_e/\sigma \rho _0 \simeq 148 \, \lambda /\sigma \rho _0$

, to yield results that are converged in large-system-size limit (informed by our previous work; cf. French et al. (Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023)). Correspondingly, we use

$\ell _x = 256 = 128 \sqrt {2\sigma } \, d_e/\sigma \rho _0 \simeq 148 \, \lambda /\sigma \rho _0$

, to yield results that are converged in large-system-size limit (informed by our previous work; cf. French et al. (Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023)). Correspondingly, we use

![]() $N_x \in$

$N_x \in$

![]() $\{ 1024,$

$\{ 1024,$

![]() $1280,$

$1280,$

![]() $1440,$

$1440,$

![]() $1792,$

$1792,$

![]() $2048,$

$2048,$

![]() $2560,$

$2560,$

![]() $2880,$

$2880,$

![]() $3584 \}$

computational grid cells in the

$3584 \}$

computational grid cells in the

![]() $x$

-direction across the

$x$

-direction across the

![]() $\sigma$

scan, where accordingly the latter three values are exclusive to two dimensions. The running time varies for each simulation, but is set to allow enough time for the plasma to (a) reconnect and (b) evolve for

$\sigma$

scan, where accordingly the latter three values are exclusive to two dimensions. The running time varies for each simulation, but is set to allow enough time for the plasma to (a) reconnect and (b) evolve for

![]() $\geqslant 3\, L_x/c = 768 \, \sigma \omega _{\textrm {ce}}^{-1} \simeq 543 \, \sqrt {\sigma } \omega _{\textrm {pe}}^{-1}$

after reconnection onsets. This duration is sufficient for evolving quantities to saturate or otherwise reach steady-state evolution.

$\geqslant 3\, L_x/c = 768 \, \sigma \omega _{\textrm {ce}}^{-1} \simeq 543 \, \sqrt {\sigma } \omega _{\textrm {pe}}^{-1}$

after reconnection onsets. This duration is sufficient for evolving quantities to saturate or otherwise reach steady-state evolution.

In this paper, we wish to investigate particle spectra in the ‘downstream,’ i.e. the region between the two separatrices. To isolate the downstream region, we apply the particle-mixing approach (Daughton et al. Reference Daughton, Nakamura, Karimabadi, Roytershteyn and Loring2014) as follows. Each computational grid cell is assigned a mixing fraction

![]() $\mathcal{F}_e \equiv (n_e^{\textrm {bot}} - n_e^{\textrm {top}}) / (n_e^{\textrm {bot}} + n_e^{\textrm {top}})$

, where

$\mathcal{F}_e \equiv (n_e^{\textrm {bot}} - n_e^{\textrm {top}}) / (n_e^{\textrm {bot}} + n_e^{\textrm {top}})$

, where

![]() $n_e^{\textrm {bot}}$

and

$n_e^{\textrm {bot}}$

and

![]() $n_e^{\textrm {top}}$

are the number densities of electrons that start at

$n_e^{\textrm {top}}$

are the number densities of electrons that start at

![]() $y \lt 0$

and

$y \lt 0$

and

![]() $y \gt 0$

, respectively. Then, we consider cells which satisfy

$y \gt 0$

, respectively. Then, we consider cells which satisfy

![]() $\lvert \mathcal{F}_e \rvert \leqslant 70\,\% (96\,\%)$

to be sufficiently well mixed to be regarded as ‘downstream’ in three dimensions (two dimensions) and the remaining cells are considered ‘upstream’ in three dimensions (two dimensions).Footnote

2

$\lvert \mathcal{F}_e \rvert \leqslant 70\,\% (96\,\%)$

to be sufficiently well mixed to be regarded as ‘downstream’ in three dimensions (two dimensions) and the remaining cells are considered ‘upstream’ in three dimensions (two dimensions).Footnote

2

When evaluating the contributions of each injection mechanism (see § 4.4), we randomly select

![]() $10^6$

particles at the beginning of each simulation and track relevant physical quantities associated with them at each time step, including velocities and electric and magnetic fields. With this information, we study the acceleration mechanisms of particles statistically (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Li, Li, Daughton, Zhang, Lloyd-Ronning, Liu, Zhang and Deng2016, Reference Guo, Li, Daughton, Kilian, Li, Liu, Yan and Ma2019; Li et al., Reference Li, Guo and Li2019a

,

Reference Li, Guo, Li, Stanier and Kilianb

; Kilian et al. Reference Kilian, Li, Guo and Zhang2020; French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023). We exclude the initial current-carrying (i.e. drifting) particles from our tracer particle analysis.

$10^6$

particles at the beginning of each simulation and track relevant physical quantities associated with them at each time step, including velocities and electric and magnetic fields. With this information, we study the acceleration mechanisms of particles statistically (Guo et al. Reference Guo, Li, Li, Daughton, Zhang, Lloyd-Ronning, Liu, Zhang and Deng2016, Reference Guo, Li, Daughton, Kilian, Li, Liu, Yan and Ma2019; Li et al., Reference Li, Guo and Li2019a

,

Reference Li, Guo, Li, Stanier and Kilianb

; Kilian et al. Reference Kilian, Li, Guo and Zhang2020; French et al. Reference French, Guo, Zhang and Uzdensky2023). We exclude the initial current-carrying (i.e. drifting) particles from our tracer particle analysis.

4. Results

First, to illustrate the reconnection process, we show several snapshots of absolute current density

![]() $\lvert J/J_0 \rvert$

(where

$\lvert J/J_0 \rvert$

(where

![]() $J_0 \equiv en_0c/2$

and

$J_0 \equiv en_0c/2$

and

![]() $J$

is the total current density) of two simulations with

$J$

is the total current density) of two simulations with

![]() $\sigma = 8$

(figure 2). The left-hand panels display a 2-D simulation and the right-hand panels display an otherwise identical 3-D simulation. To make the downstream visible in three dimensions, we apply a linear ramp of increasing opacity for

$\sigma = 8$

(figure 2). The left-hand panels display a 2-D simulation and the right-hand panels display an otherwise identical 3-D simulation. To make the downstream visible in three dimensions, we apply a linear ramp of increasing opacity for

![]() $J \geqslant J_0/2$

(opacity = 50 % at

$J \geqslant J_0/2$

(opacity = 50 % at

![]() $J = J_0/2$

and opacity = 100 % at

$J = J_0/2$

and opacity = 100 % at

![]() $J = 2 \, J_0$

) and set opacity = 0 for

$J = 2 \, J_0$

) and set opacity = 0 for

![]() $J \lt J_0/2$

.

$J \lt J_0/2$

.

Figure 2. Absolute current density

![]() $\lvert J/J_0 \rvert$

at different times after the time of reconnection onset

$\lvert J/J_0 \rvert$

at different times after the time of reconnection onset

![]() $t_{\textrm {onset}}$

. Panels on the left display a 2-D simulation (

$t_{\textrm {onset}}$

. Panels on the left display a 2-D simulation (

![]() $\sigma = 8$

) and the panels on the right display an otherwise identical 3-D simulation.

$\sigma = 8$

) and the panels on the right display an otherwise identical 3-D simulation.

The earliest time displayed is the reconnection onset time

![]() $t_{\textrm {onset}}$

, defined as when the magnetic energy drops to

$t_{\textrm {onset}}$

, defined as when the magnetic energy drops to

![]() $99.99\,\%$

of its initial value. This threshold is sufficient for

$99.99\,\%$

of its initial value. This threshold is sufficient for

![]() $t_{\textrm {onset}}$

to demarcate the very first X-point collapse. Henceforth we will shift to this time for time-dependent results.

$t_{\textrm {onset}}$

to demarcate the very first X-point collapse. Henceforth we will shift to this time for time-dependent results.

Accordingly, initial X-point collapse in two dimensions is shown to coincide with

![]() $t_{\textrm {onset}}$

in the top-left panel of figure 2. Soon thereafter, plasmoids are advected downstream (

$t_{\textrm {onset}}$

in the top-left panel of figure 2. Soon thereafter, plasmoids are advected downstream (

![]() $t_{\textrm {onset}} + 0.5 \,L_x/c$

), merge with other plasmoids (

$t_{\textrm {onset}} + 0.5 \,L_x/c$

), merge with other plasmoids (

![]() $t_{\textrm {onset}} + 1.0 \,L_x/c$

) and retain their structural integrity throughout (

$t_{\textrm {onset}} + 1.0 \,L_x/c$

) and retain their structural integrity throughout (

![]() $t_{\textrm {onset}} + 2.0 \,L_x/c$

). By contrast, in three dimensions the flux-rope kink instability dismantles plasmoids, allowing particles to escape from them (Dahlin et al. Reference Dahlin, Drake and Swisdak2014; Werner & Uzdensky Reference Werner and Uzdensky2021; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Guo, Daughton, Li and Li2021).

$t_{\textrm {onset}} + 2.0 \,L_x/c$

). By contrast, in three dimensions the flux-rope kink instability dismantles plasmoids, allowing particles to escape from them (Dahlin et al. Reference Dahlin, Drake and Swisdak2014; Werner & Uzdensky Reference Werner and Uzdensky2021; Zhang et al. Reference Zhang, Guo, Daughton, Li and Li2021).

4.1. Reconnection rate

We define the dimensionless time-dependent reconnection rate

![]() $\eta _{\textrm {rec}}(t)$

as the rate at which the unreconnected (i.e. upstream) magnetic flux

$\eta _{\textrm {rec}}(t)$

as the rate at which the unreconnected (i.e. upstream) magnetic flux

![]() $\psi _{\textrm {up}}$

decays with time, normalised by

$\psi _{\textrm {up}}$

decays with time, normalised by

![]() $v_{\textrm {A0}} B_0$

$v_{\textrm {A0}} B_0$

where

![]() $\langle {}\rangle$

is the time averaging performed every

$\langle {}\rangle$

is the time averaging performed every

![]() $(1/32) \, L_x/c$

and the upstream region is defined by cells with a mixing fraction

$(1/32) \, L_x/c$

and the upstream region is defined by cells with a mixing fraction

![]() $\lvert \mathcal{F}_e \rvert \gt 70\,\%$

(

$\lvert \mathcal{F}_e \rvert \gt 70\,\%$

(

![]() $96\,\%$

) in three dimensions (two dimensions). The peak reconnection rate is defined simply as

$96\,\%$

) in three dimensions (two dimensions). The peak reconnection rate is defined simply as

![]() $\text{max}[\eta _{\textrm {rec}}(t)]$

.

$\text{max}[\eta _{\textrm {rec}}(t)]$

.

In accordance with (4.1), we compute the time-dependent and peak reconnection rates for several values of

![]() $\sigma$

, as shown in figure 3. We find that the reconnection rate in three dimensions is consistently somewhat lower than each 2-D counterpart for every tested value of

$\sigma$

, as shown in figure 3. We find that the reconnection rate in three dimensions is consistently somewhat lower than each 2-D counterpart for every tested value of

![]() $\sigma$

, and adheres quite closely to the canonical value of

$\sigma$

, and adheres quite closely to the canonical value of

![]() $0.1$

. As for

$0.1$

. As for

![]() $\sigma$

-dependence, the peak reconnection rate

$\sigma$

-dependence, the peak reconnection rate

![]() $\text{max}[\eta _{\textrm {rec}}(t)]$

increases gradually with increasing

$\text{max}[\eta _{\textrm {rec}}(t)]$

increases gradually with increasing

![]() $\sigma$

, from

$\sigma$

, from

![]() ${\simeq} 0.1$

to

${\simeq} 0.1$

to

![]() $0.2$

in two dimensions as

$0.2$

in two dimensions as

![]() $\sigma$

varies from

$\sigma$

varies from

![]() $8$

to

$8$

to

![]() $96$

and from

$96$

and from

![]() ${\simeq} 0.08$

to

${\simeq} 0.08$

to

![]() $0.12$

in three dimensions as

$0.12$

in three dimensions as

![]() $\sigma$

varies from

$\sigma$

varies from

![]() $8$

to

$8$

to

![]() $32$

.

$32$

.

Figure 3. Reconnection rates for various

![]() $\sigma$

. (a) Time-dependent reconnection rates of 3-D (solid) and a few 2-D (dashed) simulations. (b) Peak reconnection rates, with green squares representing three dimensions and red triangles representing two dimensions.

$\sigma$

. (a) Time-dependent reconnection rates of 3-D (solid) and a few 2-D (dashed) simulations. (b) Peak reconnection rates, with green squares representing three dimensions and red triangles representing two dimensions.

4.2. Injection energies

To fit particle spectra, we perform a spectral fitting procedure described in Appendix B. To illustrate the process for acquiring the characteristic spectral parameters, we show a time-evolved downstream particle spectrum

![]() $f_{\textrm {ds}}(\gamma - 1, t)$

in figure 4(a). The downstream particle population is continuously fed by upstream particles crossing over the separatrix.

$f_{\textrm {ds}}(\gamma - 1, t)$

in figure 4(a). The downstream particle population is continuously fed by upstream particles crossing over the separatrix.

Figure 4. Downstream particle spectra from 3-D simulations. (a) Evolving downstream particle spectrum from a

![]() $\sigma =32$

3-D simulation fitted at the final time step. The vertical dashed green line indicates the measured injection energy

$\sigma =32$

3-D simulation fitted at the final time step. The vertical dashed green line indicates the measured injection energy

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

, the vertical dashed red line the measured cutoff energy

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}$

, the vertical dashed red line the measured cutoff energy

![]() $\gamma _c$

, and the dashed black line is

$\gamma _c$

, and the dashed black line is

![]() $\gamma ^{-p}$

with measured power-law index

$\gamma ^{-p}$

with measured power-law index

![]() $p$

. Solid colour lines show particle spectra taken every

$p$

. Solid colour lines show particle spectra taken every

![]() $(1/8) \, L_x/c$

, from

$(1/8) \, L_x/c$

, from

![]() $t = t_{\textrm {onset}}$

to

$t = t_{\textrm {onset}}$

to

![]() $t = t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\, L_x/c$

. (b) Downstream particle spectra of 3-D simulations at times

$t = t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\, L_x/c$

. (b) Downstream particle spectra of 3-D simulations at times

![]() $t = t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\, L_x/c$

for various initial upstream magnetisations

$t = t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\, L_x/c$

for various initial upstream magnetisations

![]() $\sigma$

. Dashed black lines show

$\sigma$

. Dashed black lines show

![]() $\gamma ^{-p}$

for

$\gamma ^{-p}$

for

![]() $\gamma \in [\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}, \gamma _c]$

using the measured values of

$\gamma \in [\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}, \gamma _c]$

using the measured values of

![]() $p, \gamma _{\textrm {inj}}, \gamma _c$

and dotted vertical lines are coloured and positioned at

$p, \gamma _{\textrm {inj}}, \gamma _c$

and dotted vertical lines are coloured and positioned at

![]() $\sigma$

values.

$\sigma$

values.

Measuring the characteristic parameters

![]() $p, \gamma _{\textrm {inj}}, \gamma _c$

helps glean their dependencies on system parameters. In figure 4(b), we show several downstream particle spectra of 3-D simulations at the time

$p, \gamma _{\textrm {inj}}, \gamma _c$

helps glean their dependencies on system parameters. In figure 4(b), we show several downstream particle spectra of 3-D simulations at the time

![]() $t = t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\, L_x/c$

for various values of

$t = t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\, L_x/c$

for various values of

![]() $\sigma$

, as well as power-law fits that extend from the injection energy to the cutoff energy. This figure highlights the precision of measurement that is afforded by implementing the spectral fitting procedure described in Appendix B.

$\sigma$

, as well as power-law fits that extend from the injection energy to the cutoff energy. This figure highlights the precision of measurement that is afforded by implementing the spectral fitting procedure described in Appendix B.

In the left-hand panels of figure 5 we show the evolved characteristic parameters of the power-law particle spectra (

![]() $p, \gamma _{\textrm {inj}}, \gamma _c$

) for various values of

$p, \gamma _{\textrm {inj}}, \gamma _c$

) for various values of

![]() $\sigma$

represented by curves of different colour. Data points are obtained every

$\sigma$

represented by curves of different colour. Data points are obtained every

![]() $(1/32) \, L_x/c$

using the fitting procedure described in Appendix B and we smooth the data with a moving time average of window size

$(1/32) \, L_x/c$

using the fitting procedure described in Appendix B and we smooth the data with a moving time average of window size

![]() $(3/32) \, L_x/c$

, i.e. where each value is replaced by the average of itself, its predecessor and its successor. In the right-hand panels of figure 5 we plot each measured parameter evaluated at

$(3/32) \, L_x/c$

, i.e. where each value is replaced by the average of itself, its predecessor and its successor. In the right-hand panels of figure 5 we plot each measured parameter evaluated at

![]() $t = t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3 \, L_x/c$

against

$t = t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3 \, L_x/c$

against

![]() $\sigma$

.

$\sigma$

.

Figure 5. Spectral parameters measured via fitting procedure (described in Appendix B) for various

![]() $\sigma$

at each time step for 3-D simulations (a, c, e) and at

$\sigma$

at each time step for 3-D simulations (a, c, e) and at

![]() $t = t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\, L_x/c$

for all simulations (b, d, f). Dotted coloured lines in (a, c, e) indicate time steps where the power-law extent is short, i.e.

$t = t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\, L_x/c$

for all simulations (b, d, f). Dotted coloured lines in (a, c, e) indicate time steps where the power-law extent is short, i.e.

![]() $\gamma _c/\gamma _{\textrm {inj}} \lt 10$

. In (b, d, f), red triangles are 2-D runs and green squares are 3-D runs. (a, b) Power-law indices

$\gamma _c/\gamma _{\textrm {inj}} \lt 10$

. In (b, d, f), red triangles are 2-D runs and green squares are 3-D runs. (a, b) Power-law indices

![]() $p(t)$

and

$p(t)$

and

![]() $p(t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\,L_x/c)$

. (c, d): Injection energies

$p(t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\,L_x/c)$

. (c, d): Injection energies

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}(t)$

and

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}(t)$

and

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}(t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\,L_x/c)$

. The dashed black line in (d) shows linear scaling, assuming

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}(t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\,L_x/c)$

. The dashed black line in (d) shows linear scaling, assuming

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}} = 1 + \sigma /4$

and the dashed purple line shows

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}} = 1 + \sigma /4$

and the dashed purple line shows

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}} \simeq \sigma [ \sigma _h^{-1} \, (1 + b_g^2)/2 ]^{1/2}$

(i.e. (2.7)), derived in § 2.1. (e, f) High-energy cutoffs

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}} \simeq \sigma [ \sigma _h^{-1} \, (1 + b_g^2)/2 ]^{1/2}$

(i.e. (2.7)), derived in § 2.1. (e, f) High-energy cutoffs

![]() $\gamma _c(t)$

and

$\gamma _c(t)$

and

![]() $\gamma _c(t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\,L_x/c)$

. The semi-transparent dashed coloured lines in (e) show the fit from (4.2) and the green (red) dashed line in (f) shows it evaluated at

$\gamma _c(t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\,L_x/c)$

. The semi-transparent dashed coloured lines in (e) show the fit from (4.2) and the green (red) dashed line in (f) shows it evaluated at

![]() $t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\,L_x/c$

, i.e.

$t_{\textrm {onset}} + 3\,L_x/c$

, i.e.

![]() $\gamma _c(\sigma ) = 6\sqrt {3}\sigma$

in three dimensions (

$\gamma _c(\sigma ) = 6\sqrt {3}\sigma$

in three dimensions (

![]() $\gamma _c(\sigma ) = 4\sqrt {3}\sigma$

in two dimensions).

$\gamma _c(\sigma ) = 4\sqrt {3}\sigma$

in two dimensions).

We find that power-law indices

![]() $p(t)$

(top row of figure 5) rapidly harden during the transient phase (

$p(t)$

(top row of figure 5) rapidly harden during the transient phase (

![]() $t \lt t_1$

), followed by a longer period whereupon they gradually soften, achieving stability

$t \lt t_1$

), followed by a longer period whereupon they gradually soften, achieving stability

![]() ${\sim} 2$

light-crossing times after

${\sim} 2$

light-crossing times after

![]() $t_{\textrm {onset}}$

(panel a). Power-law spectra harden with increasing

$t_{\textrm {onset}}$

(panel a). Power-law spectra harden with increasing

![]() $\sigma$

and are harder in two dimensions than in three dimensions by

$\sigma$

and are harder in two dimensions than in three dimensions by

![]() ${\sim} 0.2$

–

${\sim} 0.2$

–

![]() $0.3$

for any given value of

$0.3$

for any given value of

![]() $\sigma$

(panel b).

$\sigma$

(panel b).

The injection energy

![]() $\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}(t)$

(middle row of figure 5) quickly adopts an initial (i.e. at

$\gamma _{\textrm {inj}}(t)$

(middle row of figure 5) quickly adopts an initial (i.e. at

![]() $t = t_{\textrm {onset}}$

) value of

$t = t_{\textrm {onset}}$

) value of

![]() ${\sim} 6 \pm 2$

without a clear dependence on

${\sim} 6 \pm 2$

without a clear dependence on

![]() $\sigma$

. While erratic, the injection energy remains roughly within this range during the transient reconnection phase (

$\sigma$

. While erratic, the injection energy remains roughly within this range during the transient reconnection phase (

![]() $0 \leqslant t - t_{\textrm {onset}} \lt (3/8) \, L_x/c \simeq 100 \, \sigma \omega _{\textrm {ce}}^{-1}$

). Once steady state is reached (e.g. after

$0 \leqslant t - t_{\textrm {onset}} \lt (3/8) \, L_x/c \simeq 100 \, \sigma \omega _{\textrm {ce}}^{-1}$

). Once steady state is reached (e.g. after

![]() $1.5 \, L_x/c \simeq 400 \, \sigma \omega _{\textrm {ce}}^{-1}$