Introduction

The educational proposals of R. Murray Schafer (Ontario, Canada, 1933–2021) fall within the so-called creative pedagogies or, following the periodisation of Hemsy de Gainza (Reference HEMSY DE GAINZA2004), in ‘generation’ of composer-pedagogues. Parallel to Schafer, John Paynter, George Self and Brian Dennis in the UK, Pierre Schaeffer and collaborators of the Groupe de Recherches Musicales in France, shared similar pedagogical-compositional approaches in the context of the 1960s. Schafer and his contemporaries paid special attention to sound as the main source for generating other processes linked to listening and sound experimentation, musical creation and performance. From Canada, Schafer contributed texts, musical works and pedagogical interventions oriented towards the search for a ‘sound education’ with the aim of forming individuals who were sensitive, creative and committed to their (sound) environment. His pedagogical principles regarding music education can be summarised in three key aspects, as he explained in a lecture at UNESCO:

1. To try to discover whatever creative potential children may have for making music of their own. 2. To introduce students of all ages to the sounds of the environment; to treat the world soundscape as a musical composition of which man is the principal composer; and to make critical judgments which would lead to its improvement. 3. To discover a nexus or gathering-place where all the arts may meet and develop together harmoniously (Schafer, Reference SCHAFER1986, p. 243).

Clearly, these ideas move away from a curriculum focused on musical language and the development of technical skills, and move closer to the search for a comprehensive music education, in line with the needs of education and society in the 21st century. The approach of a ‘holistic music education’ recognises that each part of the musical experience is flexibly connected as they are sustained by personal, social and environmental relationships and therefore addresses the cognitive, bodily and affective needs of the participants (Abril & Gault, Reference ABRIL, GAULT, Abril and Gault2022).

In this context, transversal competences are situated as common orientations of attributes and values for comprehensive training, and can be applicable in different situations beyond the disciplinary (Clanchy & Ballard, Reference CLANCHY and BALLARD1995; Aróstegui, Reference ARÓSTEGUI and Ortega-Sánchez2022). These competences then focus on digital, equity and sustainability and care for the environment, or ‘collaboration, critical reflection, communication and creativity’ (Jefferson & Anderson, Reference JEFFERSON and ANDERSON2021). In this sense, these competences seek to promote the creation of knowledge and new and good social relations among citizens in a hyper-technological society with growing environmental problems. This challenges educational institutions both in disciplinary and cultural terms (Magendzo, Reference MAGENDZO1998), as the consolidation of the daily use of technologies and the possibility of seeing through them the wide social and economic gaps refer to a complex and multidimensional scenario that must be explicitly addressed through new educational approaches and relationships.

Background: Schafer’s context

In contextual terms, Schafer’s ideas begin to be elaborated in the incipient post-industrial era, which had its symbolic beginning with the end of the Second World War. This period of time was characterised by an understanding of the economy based not only on the extraction of resources but also on the circulation and incipient creation of knowledge through the new technological means of the time (Bell, Reference BELL1973). In social terms, the masses are consolidated in the great metropolises born at the beginning of the 20th century (rural-urban migration), which are accompanied by new technologies (formerly television) that provide leisure spaces and generate an industrialisation of time (Apple, Reference APPLE1997). Hyperurbanisation and daily routine then implied a detachment, disconnection and capitalisation of nature and its products (Harvey, Reference HARVEY2012). In this space, already in the 80s of the last century, transnational agreements on environmental care and the incipient climate crisis began to be raised and installed, for example, through the Stockholm Conference (1972) and the Montreal Protocol (1987).

In what some call ‘socio-cultural revolution’ and ‘world modernity’ (Fazio, Reference FAZIO2009), Schafer’s ideas are articulated and highlighted by his interest in the sound environment from an interdisciplinary and socially engaged perspective. With the creation of the World Soundscape Project (WSP) and the conceptualisation of Soundscape, Schafer (Reference SCHAFER1970) sought to design a global acoustic ecology. In doing so, he sought both to investigate and preserve sounds in their diverse environments and to relate them on a global scale. The starting point was Vancouver, where Schafer and his collaborators at Simon Fraser University expanded these ideas to other places, as they set out in Europa Sound Diary (Reference SCHAFER1977). One of the contributions of this group was to unify independent areas interested in the study of sound – such as acoustics, ecology, health sciences, architecture, sound art, among others – linked to the notions of Soundscape (Schafer, Reference SCHAFER1970). These issues are reflected in the broad scope of Schafer’s literary output. For example, in fields such as composition, acoustic ecology and music pedagogy. Regarding the first two, his texts incite listening, creation and social interaction by stating: ‘A fascinating macrocosmic symphony is being played ceaselessly around us. It is the symphony of the world soundscape. And we are its composers’ (Schafer, Reference SCHAFER1970, p. 3). Meanwhile, his ideal of music was clearly expressed in his pedagogical writings, as Adams (Reference ADAMS1983) states in his biography: ‘Schafer’s commitment to music in society shows most clearly in his contributions to music education. Here, in simplified form, all his ideas come together’ (p. 50).

It is a literary production scattered in some twenty books (published mainly in English and translated into numerous languages). Some of these texts were first published as individual booklets and then compiled into explanatory volumes, some offer experiences and exercises that Schafer himself has done in experimental music courses, for example: The Composer in the Classroom (1965), Ear Cleaning: Notes for an Experimental Music Course (Reference SCHAFER1967), The New Soundscape: a handbook for the modern music teacher (1969), When Words Sing (1970), The Rhinoceros in the Classroom (Reference SCHAFER1975), all compiled in Creative Music Education: a handbook for the modern music teacher (Reference SCHAFER1976). Others have a more philosophical orientation to his musical and pedagogical ideas: The Tuning of the World (1977) – reprinted as The Soundscape: Our Sonic Environment and the Tuning of the World (Reference SCHAFER1993) – The Thinking Ear: Complete writings on Music Education (Reference SCHAFER1986). In the latter, it offers various practical exercises that promote listening, improvisation and a creative relationship with the sound environment: A Sound Education: 100 Exercises in Listening and Soundmaking (1992), HearSing: 75 Exercises in Listening and Creating Music (2005). These lectures and various writings express his main rationale for music in education and society, presenting music teachers as active agents:

‘Music is, after all, nothing more than a collection of the most exciting sounds conceived and produced by successive generations of men with good ears. The compelling world of sounds around us today has already been investigated and incorporated into the music produced by today’s composers. The task of the music educator is now to study and theoretically comprehend what is happening everywhere along the frontier of the world soundscape’ (Schafer, Reference SCHAFER1969, p. 57).

In summary, his extensive literary output develops the concept of music based on listening and recognising the soundscape and the links between human beings of all cultures and eras and the soundscape.

Aims

Previous studies draw attention to Schafer’s influence on the development of a philosophy of experiential music education (Boucher & Moisey, Reference BOUCHER and MOISEY2019) project his pedagogical reach into the 21st century (Rutherford, Reference RUTHERFORD2014). However, there are no systematic studies that provide insight into the scope of Schafer’s pedagogical ideas in the scholarly literature. In this sense, this work would not only help to organise and examine his ideas in academia but also inspire music educators through creative, innovative and interdisciplinary music education that is linked to cross-disciplinary approaches. The latter requires linking what happens in the music classroom with broader elements that transcend the discipline and organically integrate other languages and seek to solve other problems, not only those of musical language. Taking into account these foundations, the purpose of this work is to know and understand the different conceptual representations of Schafer’s ideas on music education in the international scholarly literature and their current relevance in the framework of transversal competences as an expression of education in the 21st century. Specifically, the following research questions have been raised:

RQ1: How have Schafer’s ideas been researched and in what fields of action have they been described?

RQ2: Which of Schafer’s concepts have been developed and researched and what have been their representations in the scholarly literature, specifically in the field of music education?

Method

This work was approached from a qualitative perspective as the data were analysed, organised and interpreted as results of the subjectivity of the scientific experience and gaze (Stake, Reference STAKE1995). In the search for a precise and deep understanding of the representations developed by international researchers on the work of Schafer, a systematic review of the scientific literature was carried out. Systematic review consists of identifying, selecting, evaluating and synthesising evidence in high-impact research in a transparent and accessible way (Sánchez-Serrano et al., Reference SÁNCHEZ-SERRANO, PEDRAZA-NAVARRO and DONOSO-GONZÁLEZ2022). Specifically, this work has followed the PRISMA guidelines for the development of a coherent, systematic and rigorous literature review. In this way, we attempt to transparently report each step in the literature review (Moher et al., Reference MOHER, LIBERATI, TETZLAFF and ALTMAN2009).

Sources, keywords and inclusion criteria

This review started with a discussion among the researchers about the search criteria that would lead to the fulfilment of the objectives. After examining a number of databases on an individual and exploratory basis, a meeting was held to share impressions on the themes observed in a preliminary way, the search criteria and keywords, and the databases to be used. Thus, it became clear that a search in, for example, Google Scholar, which offers too broad parameters, might yield results not directly related to Murray Schafer and his ideas in the field of music education. In this sense and in relation to the review criteria, it was decided to carry out the search only in scholarly articles published in the 21st century (until 31 August 2024), in multidisciplinary databases such as WOS, Scopus, ERIH Plus, Proquest, DOAJ and Dialnet Plus, and in three languages: English, Spanish and Portuguese. With regard to the keywords, the search was oriented to delimit general concepts related to Schafer’s ideas and not limited to specific concepts of his intellectual production. For this reason, it was decided to search with the following descriptors: ‘M. Schafer’ OR ‘Raymond Murray Schafer’ AND ‘music education’ OR music AND education. These words were applied only in the fields of Title, Abstract and Keywords, as we sought to delimit by means of the relevance given to the ideas of Schafer within these fields of academic publications. Once the words were applied in this order, they were searched again, but with the words in a different order, which in some databases produced one or two new results. This procedure went some way to ensuring that the search was as complete as possible.

After exporting the lists of articles from each database to a shared online template, duplicate articles were checked. After that, the general review began with the aim of confirming the inclusion or exclusion of papers not related to the subject to be investigated. To this end, the following exclusion criteria were established:

-

1. Anecdotal treatment of Schafer’s ideas.

-

2. The articles were not related to education at any level (early childhood, primary, secondary, university or non-formal education).

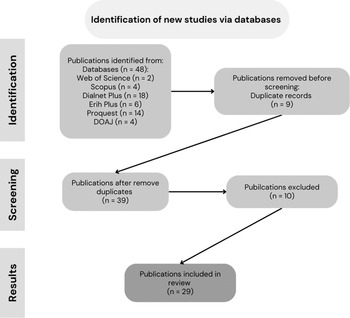

The inclusion/exclusion process involved a parallel general reading of the articles, which allowed the initial themes, research perspectives and areas of application to be observed. In this sense, the researchers met again to discuss some of the ideas that emerged from the general review. In summary, the following Figure 1 shows the process that took place:

Figure 1. PRISMA-based systematic review process flowchart.

Table 1. Articles included in the systematic review

Categorisation and analysis

Once the articles had been selected, an in-depth reading began, which allowed for an emergent categorisation of the themes found. Content analysis was applied to the works included, focusing not only on the concepts developed by the authors but also on the structure, work methodology and examples incorporated in the texts (Flick, Reference FLICK2015). Subsequently, we sought to represent the different themes of the literature in an organised and critical manner, which in some way implied intellectual growth around the concepts (Peña & Pirela, Reference PEÑA and PIRELA2007).

Findings

This section presents the findings obtained from the selected academic publications (N = 29) and attempts to answer the research questions. The following categories of analysis emerge after discussion among the researchers, seeking to organise knowledge and recreate new representations in a delimited theoretical body.

RQ1: How have Schafer’s ideas been researched and in what fields of action have they been described?

The works that address Schafer’s ideas reflect a diversity of countries, areas of knowledge, ways of being addressed and educational levels or approaches. Firstly, it can be seen that Schafer’s ideas are valued in different countries, either where the researchers come from or where they work, being present in four continents (America, Europe, Oceania and Asia). The country with the highest number of papers is Brazil (N = 13), followed by Canada (N = 7; one of the texts is shared with Brazil), Spain (N = 5), Portugal (N = 2, both shared with Brazil). The remaining countries presenting papers are Australia (N = 2), Colombia (N = 1), USA (N = 1) and Taiwan (N = 1). This would show a global interest in Schafer’s ideas, with the number of papers in the South American country being particularly interesting.

Secondly, Schafer’s ideas are dealt with in journals from different areas of knowledge, which mainly belong to the area of Music (N = 15), on the one hand, and Education (N = 11), on the other, followed by works in Multidisciplinary journals (N = 3). Beyond the general, it is observed that the predominant sub-areas are Music Education (N = 8), for example, with the journal The Canadian Music Educator, and General Education (N = 8). These are followed by papers in interdisciplinary journals in the field of the Arts (N = 5), for example, with the journals Cuadernos de Música, Artes Visuales y Artes Escénicas. In addition, it is interesting that Schafer finds space both in the multidisciplinary field from the sub-area of sound (N = 1) and urban studies and environmental technology (N = 1), as well as in Education journals linked to Philosophy and Ethics (N = 1), and specific Didactics in Science (N = 1). This would initially imply the transversality of their ideas and the impact on other areas of knowledge beyond music.

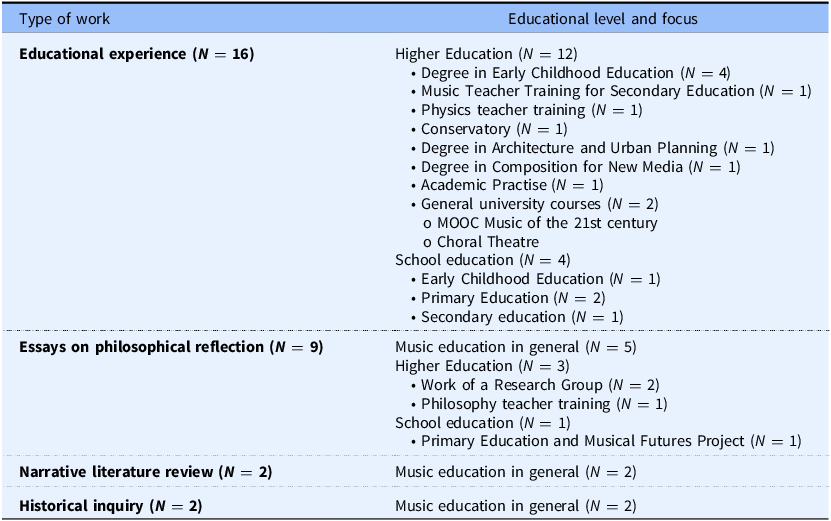

In terms of the types of work presented, two research approaches can be observed, on the one hand, empirical, reflected in Educational Experiences (N = 16) and, on the other, essays on philosophical reflection (N = 9), documentary narrative (N = 2) and biographical and autobiographical themes (N = 2). This could demonstrate the interest in portraying, explaining and exemplifying Schafer’s proposals in the field of educational experience. Finally, in educational terms, the researchers put Schafer’s ideas into play at different levels and disciplines, ranging from early childhood education to university education. If we take the categorisation of types of work, we can see in Table 2 below the different educational levels and focuses of interest:

Table 2. Relationship between types of work, educational levels and focus of the works analysed

Schafer’s ideas are strongly diversified in disciplinary terms, although they predominate in music-related teaching, both in school music education and in university music education. In this area, proposals outside music education also stand out, such as the training of Physics and Philosophy teachers and in Architecture and Urbanism courses.

In summary, it can be seen that the ideas of the Canadian pedagogue are valued by a diverse group of researchers, whose representations are found in journals of different areas of knowledge, ranging from musical to multidisciplinary. Here, researchers mainly inquire about educational experiences at different educational levels. This could be interpreted as a certain flexibility of Schafer’s ideas that, rather than being situated in delimited musical spaces, they are capable of being thought from multiple corners of education.

RQ2: Which of Schafer’s concepts have been developed and researched and what have been their representations in the scholarly literature, specifically in the field of music education?

The figure of Schafer is inextricably associated with the new concepts of music in the post-war period and throughout the second half of the last century. His innovative approaches to sound, silence, noise, ways of listening and sound creation, among other subjects, are refracted in his pedagogical ideas and, in this way, have an impact on the scholarly literature analysed in this work. Thus, Listening as a critical attitude, Creative Music Education as a series of procedures and Soundscape as an interdisciplinary resource are addressed transversally from music and sound literacy and the reading of social issues.

Listening as a disposition

The disposition or attitude of listening with different characterisations (deep, active, intelligent, holistic, selective or conscious) is installed as a point that can connect the concepts of soundscape and creative music education. Listening to silence, to noise, to the other (as a social being), to musical repertoires and the soundscape are placed as primordial sources for the beginning of enquiry, creation and reflection activities.

Firstly, noise and silence are installed as basic resources to initiate listening and understanding of the natural environment and its cultural, economic and social implications. For example, the attentive listening and significance of silence and noise seek to unravel the problems of the post-industrial era. Thus, noise pollution is situated as a reality that must be consciously and intelligently listened to and promoted by music teachers in the face of different environmental problems (da Silva, 2011). Therefore, it is that attentive listening is placed at the level of, for example, critical reflection, but from a sound perspective (Leal, 2020), which will help to unravel and rethink our relationship with the environment and move from a visual to a sound culture (Oliveira Costa et al., 2019).

Listening also refers to an attitude in the music classroom that seeks to include, on the one hand, diverse repertoires and, on the other, the ideas of the students. Regarding the former, referring to repertoires, we speak of non-traditional literacy that values holistic listening more than musical appreciation as a curricular concept (Recharte, 2019). In this way, listening allows the development of a personal view of what music means through classical and contemporary repertoires (Lopes da Silva & Vasconcelos, 2017). In this space, reflections are proposed on listening and the culture industry, in Adorno’s terms, and its relationship with the social environment and the environment (da Silva & Leonido, 2019, 2020; Oliveira Costa et al., 2019) and the free listening of a wide repertoire of music, but aware of the implications of mass media in students’ habits. Listening then comes into play together with ‘habit’ as a concept and technique developed by Gaston Bachelard where there is systematic, but always novel, listening (Pohlmann & Gava, 2014). On the second, listening is revealed as a willingness to work on the basis of the inclusion of students’ ideas and experiences, for example, both in their socialisation processes and in their musical literacy and creation in an intercultural framework (Uriarte & Baggio, 2018). Still in the field of music, listening is highlighted from an instrumental perspective as access to the aesthetic experience. This process is situated in specific contexts with their ‘cultural’ meanings. Here, sound education enters into dialogue with Gaztambide-Fernández’s notions of ‘cultural production’ and with ‘acoustemology’, following Steve Feld’s anthropological corpus (Recharte, 2019). Within the framework of these two concepts, listening, on the one hand, must be accompanied by a critical understanding of sounds as symbolic productions specific to human beings and their spaces. And, on the other hand, it must analyse how and in what framework of relations between the various sources (human, natural or artificial) sounds are produced.

Leaving the field of music, the attitude of listening attentively with open ears is useful in research on, for example, urban projects linked to memory and cultural heritage, where a relationship between citizens and public space is hidden (de Souza Soares & Queiroz Rego) or projects related to the training of physics teachers through the problematisation proposed by Paulo Freire (Oliveira Costa et al., 2019). Next, the attitude of attentive listening begins to be related to ‘enquiry’ (Friesen & Simons, 2021), since in the field of reflection it is linked to the experience of philosophising as a rational and sensitive openness to everyday and social issues. In this way, listening comes into play with the ideas of Michel Foucault and the philosopher Paula Cristina Pereira once it is conceived as a ‘hermeneutic’ experience capable of being a means to feel, reflect and philosophise about music and the soundscape, taking into account each context (Marton, 2017). So, beyond the disciplinary, be it music, urban planning or philosophy, this disposition or attitude allows us to recreate and imagine responses under (inter)disciplinary concepts with certain contexts and social representations.

In summary, listening is represented as a gateway to the understanding of the environment and the issues that underlie territories (space and body), i.e. for the development of conscious listening (both in the environmental field and in the cultural industry); and as a strategy for an inclusive approach to music through diverse repertoires.

Creative music education: processes for inclusive literacy

Other ideas of Schafer identified in the literature are grouped around the area we call ‘Creative Music Education’. This theme is shown as a pedagogical foundation where Schafer’s ideas serve as a starting point to develop educational and artistic proposals or to generate historical-documental and aesthetic revision essays. This term coincides with one of Schafer’s compilation volumes (1976): Creative music education: a handbook for the Modern Music Teacher.

Different works explore democratic approaches to teaching and music literacy based on the ideas of Schafer. Friesen & Simon (2021) describe a critical literacy experience around listening practices, sound enquiry, artistic interaction between sound and body, and the use of silence. Based on an artistic-enquiry approach, connections are drawn between literature and sound, where Schafer’s notions are used to read and interpret the dystopian novel Fahrenheit 451 by Ray Bradburry (1953). In this experience, the literary text takes on new dimensions through sound: the vibrations in the body through reading, the sound representations of words, the invocation of sounds and the reflection of the sound environments evoked throughout the novel. The intersection between literature and sound creation reflects in this work an interdisciplinary approach that emphasises student involvement, the development of sensory and communicative skills and a commitment to creative listening. In this way, the search for new forms of music literacy reveals a paradigm shift in teaching and, in Schafer’s case, focuses on the valorisation of sound as a source of approach to music. Giving greater importance to sound promotes the development of inclusive and democratic practices in music teaching-learning processes and is contextualised within current educational paradigms (Malaquias & Vieira, 2016).

The non-conventional ways of representing musical signs are another of the proposals in which Schafer challenges some of the barriers of musical practices. In this line of accessible music education, Moisey (2020) reminds us that music learning in the formal sphere is not a reality within everyone’s reach, but reflects areas of emptiness and disparity, especially in rural or peripheral regions. Thus, based on the notions of Schafer, the children of Old Crown, Yukon Territory, in Canada, are the protagonists of an experience based on the creation of unconventional scores where Schafer’s proposals presented in Ear Cleaning: Notes for an Experimental Music Course (Reference SCHAFER1967), The New Soundscape: A Handbook for the Modern Music Teacher (1969), The Rhinoceros in the Classroom (Reference SCHAFER1975) or The Tuning of the World (Reference SCHAFER1993) are revalued: new ways of teaching, expressing and enjoying the musical experience (Moisey, 2020).

The Creative Music Education approach brings ideas that are presented as catalysts for self-determination and inclusion, against the authority that undermines the inventiveness of participants in the musical experience. The Wolf project questions musical authority within a group that goes out into the forest to create music for months at a time (Flusser, 2000). This experience aims to think about the violence of the musical expert, hierarchies and new ways of making music both in the school context and in music teacher training. To this end, the same author develops a dialogue between the ideas of Hannah Arendt, Janusz Korczak and Schafer with the aim of reflecting on other ways of creating music that, on the one hand, attend to the teacher-pupil educational relationship and, on the other, encourage thought, commitment and ethical and aesthetic attitudes as needs for change in music education.

Schafer’s pedagogical ideas inspire greater flexibility, therefore, they could be related to the development of innovative methodologies. The literature gathers teaching experiences that, given the ductility that Schafer’s notions suggest, are adaptable to all educational levels and to different settings, formal and non-formal. For teachers, the creative notions related to listening, soundscape and musical composition serve as a reference for applying approaches that promote a more horizontal and participatory teaching in music education. In other words, promoting these creative provisions offers the opportunity to recognise students’ different identities and abilities and ensure participation in music lessons. In this sense, experiences are documented where cooperative and collaborative work methodologies (Uriarte & Baggio, 2018), project-based learning (Botella & Adell, 2016), student-based learning (Rodríguez Lorenzo, 2015) and multicultural perspective (Rodríguez Lorenzo, 2017) are applied as strategies to optimise emotional management, communication, creativity and the development of transversal skills in the classroom. One experience worth highlighting is the implementation in the secondary classroom of the ‘cooperative method by projects’, which takes ideas from Schafer, Paynter and the French François Delalande and Guy Reibel. Unlike the ‘master class’, its application yielded better results in the areas of student motivation and protagonism, and the transfer of learning to other situations and the experiential value (Botella & Adell, 2016).

Schafer’s influence is also reflected in the shaping of educational curricula in different countries, such as Australia, Canada and the United States. Southcott & Burke (2012) analyse Schafer’s impact on Australian music educators after his visit to the country in the 1970s. Although in line with the ideas of Peter Maxwell Davies, John Paynter and George Self, Schafer’s name is defined as ‘revelatory’ for teachers and students who engage with his innovative proposals and his ideas as ‘catalysts’ for a new approach to music. While these ideas are framed in a context of changing music in the school curriculum, the strong conviction of the active role that students can and should play in sound creation was embedded in Schafer’s proposals (Southcott & Burke, 2012). For example, in Canada, Schafer’s ‘unorthodox’ ideas gradually spread to the country’s schools, sometimes accepted by innovative music educators, sometimes convincing more traditionalist teachers of his strategies contained in The Music Box (Schafer, Reference SCHAFER1965). In the United States, Schafer’s influence also significantly affected music education approaches, as did Orff. However, his proposals for creative music education received a real boost with the advent of digital technology (Kennedy, Reference KENNEDY2000). In this sense, although Schafer’s creative ideas have a disparate currency in different contexts, they are currently strongly present in the Canadian context, for example, through non-formal music education projects such as Musical Futures (Heckel, 2017), creative experiences in rural spaces (Moisey, 2020) and dissemination of his pedagogical principles (Rutherford, Reference RUTHERFORD2014).

In short, Schafer’s pedagogical proposals are in line with very current and relevant approaches to the challenges of education in a global society. His questioning of environmental pollution brings him closer to a committed and critical citizenship education; his reflections on philosophical and aesthetic topics that affect integral education are inserted within critical thinking and metacognition and inquiry-based learning; likewise, his proposals give everyone a voice to create, listen and compose. In short, it summarises and raises the voice of the main approaches of creative pedagogies. According to Rutherford (Reference RUTHERFORD2014), ‘the driving forces behind Schafer’s methods are a fundamental respect for each individual, as well as a conviction to self-determination and inclusion’ (p. 20).

Soundscape as an educational resource and social construction

Closely linked to listening, soundscape is represented in the literature from different dimensions: as a sound source to be discovered, as an interdisciplinary educational resource and as a social and cultural construction. This means that the soundscape can be transformed and we can participate in it, whether individually or collectively, whether in the space of the music classroom, the neighbourhood or the world.

Almost half of the selected texts (N = 12) refer to the soundscape, which is represented as an interdisciplinary resource and a starting point for the development of educational projects. Through the soundscape, musical compositions and/or reflections on the environment are realised. For example, in terms of composition and performance, we can highlight the multidisciplinary choral theatre proposal in a Taiwanese university, where local soundscapes in their sounds, environment and meaning were represented with audiovisual and human means (Wang, 2023). In this space, it is interesting that most of the interdisciplinary educational experiences take certain technological media as a means for the realisation of their projects, both centrally and in a complementary way. First, technology is installed as a medium for the recording of different sound sources and composition. On the one hand, sounds are recorded with analogue technologies for the reflection of the immediate environment for primary school children (Deans et al., 2005) and digital technologies, such as Audacity, are used for the composition of soundscapes for a general university course on 21st-century music (Chao-Fernández et al., 2020). On the other hand, different software is used for remixing, looping and sound creation using platforms such as GarageBand, Audacity, LoopyHD and MadPad (Heckel, 2017). Finally, digital and analogue technologies seek to expand both the possibilities of recording outdoors and working in the studio by taking the soundscape as a device for the composition of sound ‘narratives’ (Walzer, 2020).

Moving on to interpretations of the soundscape, some works approach it from the perspective of acoustic ecology (Deans et al., 2005; Leal, 2020). Here, noise and silence become relevant as elements determined by the economic context and progress. Sound education as an understanding and emancipation of these sounds is therefore necessary in order to reflect on and become aware of the process of creation as a social practice. The soundscape finds spaces in concert halls with Cage and outside of traditional Western music as a starting point for creation. In this line of creative possibilities offered by the soundscape, the notions of music are broadened towards a more diverse and inclusive approach as a ‘sound fact’. On the other hand, works appear where the soundscape is decoded sonically from social and aesthetic codes, which depend on the culture and identity of the subjects (Cárdenas-Soler & Martínez-Chaparro, 2015). Thus, it reflects on the relationship between the subjects and the environment and its constant transformation in relation to meanings. The soundscape is revealed as materiality, movement and space, which can be re-created by humans (Recharte, 2019). As an example, but outside formal education, the soundscape is used as a resource for listening and creation from a social and musical perspective. Taking the proposals of Schafer and Lucy Green, the aim is to describe and reflect on the commonalities and potentialities of the soundscape in a non-formal music education project in Canada such as Musical Futures (Heckel, 2017).

Finally, from a process-product perspective, some authors highlight the idea of soundscape as art, on the one hand, capable of stirring students’ senses and emotions, an issue that teachers should be responsible for (Botella, 2020) and, on the other, in connection with the ideas of composers such as Pauline Oliveros and the themes of conflict and violence in the world and listening to Cage’s silence. At the same time, the problem of noise pollution and the need to become aware as authors of this situation is highlighted once the sounds that surround us are human compositions and we must develop a certain personal social responsibility (Rutherford, Reference RUTHERFORD2014). In other words, music education cannot be thought of and represented without an awareness of noise and environmental pollution. This refers, then, to the multiple possibilities of thought and action that working with the sound environment provides.

Conclusions

It seems that the reality shows a music education in decline (Aróstegui, Reference ARÓSTEGUI2016), which undervalues music in school curricula and in the allocation of the necessary material and human resources. This situation is the consequence of an extensive debate on the place that music should occupy in school and society and where to direct actions for change. In light of the present study, it is considered that Schafer’s innovative and transversal pedagogical ideas can contribute to a natural integration of music in school curricula and thus enrich this debate by providing creative, inclusive and transdisciplinary approaches. Although some of his proposals need to be adapted to today’s more complex, technological, globalised and uncertain context, Schafer’s pedagogical and artistic-musical foundations have a place in today’s education. If we think about education in the 21st century and the framework of transversal competences, it seems that Schafer’s ideas make sense and can guide us along different lines. One of these lines refers, following Reimer (Reference REIMER2022), to the human dimension that should characterise music education. In this framework, Schafer’s ideas are echoed by self-determination and the relationship with the environment as inherent principles of education.

In the field of technologies, his ideas could be framed in a new relationship between technologies (digital and analogue), the sound environment and creation. Probably, the relationship between software and recording and creation devices, together with instruments and sound sources (of all kinds and from any environment), could show us the overcoming of the digital era and the passage to the ‘post-digital’, which implies an extensive commitment to the challenges that they imply (Clements, Reference CLEMENTS2018). On the other hand, their proposals with flexible boundaries in listening and creation are strongly linked to the participation of all in the educational experience, i.e. they seek to include rather than exclude students’ voices (identities), for example, in the reflection and creation on and in the soundscape. For their part, in the socio-environmental field, their ideas are relevant, as they seek to dimension sound as a source of culture, history and identity and to raise awareness of the human relationship with the sound environment and to promote a legislative framework for dealing with noise pollution.

In relation to notions of sound, noise and silence, his pedagogical proposals offer opportunities beyond music, linked to disciplines such as ecology, physics, acoustics, geography, and heritage. These ideas are related to other interdisciplinary approaches that are currently gaining strength. The articulation between transversal competences, interdisciplinarity and Project Based Learning gives the opportunity to revive the longing for an education that understands reality as a space of complex (and interconnected) epistemologies and that enjoys credibility in the face of the needs of today’s labour market: the formation of creative human capital. Derived from the above, when sources and media diversify in their use and social problems find space in the school, the search for committed and responsible solutions becomes necessary (Giroux, Reference GIROUX2003; Allsup, Reference ALLSUP2022). Thus, the development of creativity as a working foundation of Schafer is transferred to a provision of the educational framework of the 21st century.

We agree with Rutherford (Reference RUTHERFORD2014) on the continued relevance of Schafer’s proposals in the current context. However, this review has shown the low presence of research in the context of specialist music teacher education, which should be an area where Schafer’s ideas could have greater exploration and pedagogical application. This refers to the fact that experimental pedagogies may not be sufficiently systematised and developed in initial and life-long music teacher education, unlike other methods such as Orff, Kodaly and Dalcroze (Oriol, Reference ORIOL2005). Therefore, for the real implementation of his ideas, a paradigm shift in music education seems to be necessary, starting from reflections that delve into the need or not to include his ideas in the curricula and in the relationships with our students. The questions raised by Schafer (Reference SCHAFER1975) about what the pedagogical foundations of music should be (what music to teach, who should teach it, how to teach music) question the more traditional music education processes and move towards the search for more practical, innovative and interdisciplinary methods that encourage musical experience and creativity in the classroom. Their ideas are evidence of a much more flexible music education, outside the frameworks of the academicist tradition and with the awareness of developing a global mentality in relation to participation, care for the environment and sustainable development. This implies that its concepts are installed as catalysts for a ‘new’ curriculum, that is, for new ways of learning-teaching music, relating it to the disciplinary and the social, and decentring the aesthetic function. Its epistemology leads us to relate to and construct knowledge in other ways, together with the teaching staff, the sound environment and music. Precisely, this study offers a more detailed view of Schafer’s pedagogical principles through a review of the scientific literature of this century, which should be followed up with comprehensive reviews of his ideas in school music curricula, university and non-formal contexts.

In short, like his contemporaries (Paynter, Self, Dennis and others), Schafer’s ideas lead to reflection on the stagnation of curricula in terms of music teaching, the centrality or marginality of creativity and forms of music literacy. According to Paynter (Reference PAYNTER1992), even if traditions try to resist, there will always be a perhaps minority group that will make efforts for change. These efforts will seek to reflect on other ways of making and learning music in its broad definition and with its diverse sources. In this space, emphasis is placed on the disruptive nuance that their ideas acquire, if we put them in perspective with the active methodologies of the 20th century, which partially appear in primary education and in the training of music teachers. Schafer’s ideas are framed within the search for a musical pedagogy that is more open and receptive to other languages and problems, that is to say, they are connected with the needs of an inclusive, multicultural, interdisciplinary, ecological and, in short, transversal society and education. According to Schafer (Reference SCHAFER1965), ‘our system of music education is one in which creative music is progressively vilified and stifled’ (p. 33). It will then be necessary for music teachers to move towards it, quickly grasping the needs of today’s school and listening to their pupils, their environment and their desire to create.

Funding statement

This work was supported by grant PID2021-128645OB-I00 funded by Ministerio de Ciencia, Innovación y Universidades del Gobierno de España/AEI/10.13039/501100011033 and by ERDF, EU, Una manera de hacer Europa. R&D project: Transversality, Creativity and Inclusion in School Music Projects: An Evaluative Research (TCIEM).