1. Introduction

The Antarctic ice sheets contain about 70 % of the world’s freshwater (Fuoco et al. Reference Fuoco, Colombini, Ceccarini and Abete1996). As such, predictions of complete melting will correspond to a

![]() $58$

m sea-level rise (Shepherd et al. Reference Shepherd2018). Indeed, both observations and modelling show that the Antarctic ice sheet is losing mass at an alarming rate (Harig et al. Reference Harig, Lewis, Plattner and Simons2015; Paolo, Fricker & Padman Reference Paolo, Fricker and Padman2015; Rignot et al. Reference Rignot, Mouginot, Scheuchl, Van Den Broeke, Van Wessem and Morlighem2019). Understanding the mechanisms of ocean-driven melting of ice shelves is key to accurately predicting the mass loss of the Antarctic ice sheet (Rosevear et al. Reference Rosevear, Gayen, Vreugdenhil and Galton-Fenzi2024). Ice sheet melting initiates at the base or the grounding line, where the ice sheet leaves the ground and floats to come in contact with seawater. The melting is due to the difference in temperature and salinity of the ice sheet and seawater. This basal melting is the dominant mode of mass loss, particularly for the western Antarctic ice shelves (Rignot et al. Reference Rignot, Jacobs, Mouginot and Scheuchl2013) where most of the ice sheet is grounded beneath sea level. Ice-face melting is also an important process in the study of iceberg melting (e.g. Cenedese & Straneo Reference Cenedese and Straneo2023). Here, the melt-water forms a laminar boundary-layer (BL) plume adjacent to the ice sheet, which subsequently becomes turbulent. Although the large-scale melting of Antarctic ice is often governed by turbulent BL dynamics, it is important to note that laminar flow can persist over the first few tens of centimetres along a vertical ice face. For instance, Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) observed that the transition to turbulence typically occurs after a short vertical distance. The present study therefore focuses on this laminar regime to gain fundamental insight into BL development prior to the onset of turbulence, without the additional complexity of a fully developed turbulent flow.

$58$

m sea-level rise (Shepherd et al. Reference Shepherd2018). Indeed, both observations and modelling show that the Antarctic ice sheet is losing mass at an alarming rate (Harig et al. Reference Harig, Lewis, Plattner and Simons2015; Paolo, Fricker & Padman Reference Paolo, Fricker and Padman2015; Rignot et al. Reference Rignot, Mouginot, Scheuchl, Van Den Broeke, Van Wessem and Morlighem2019). Understanding the mechanisms of ocean-driven melting of ice shelves is key to accurately predicting the mass loss of the Antarctic ice sheet (Rosevear et al. Reference Rosevear, Gayen, Vreugdenhil and Galton-Fenzi2024). Ice sheet melting initiates at the base or the grounding line, where the ice sheet leaves the ground and floats to come in contact with seawater. The melting is due to the difference in temperature and salinity of the ice sheet and seawater. This basal melting is the dominant mode of mass loss, particularly for the western Antarctic ice shelves (Rignot et al. Reference Rignot, Jacobs, Mouginot and Scheuchl2013) where most of the ice sheet is grounded beneath sea level. Ice-face melting is also an important process in the study of iceberg melting (e.g. Cenedese & Straneo Reference Cenedese and Straneo2023). Here, the melt-water forms a laminar boundary-layer (BL) plume adjacent to the ice sheet, which subsequently becomes turbulent. Although the large-scale melting of Antarctic ice is often governed by turbulent BL dynamics, it is important to note that laminar flow can persist over the first few tens of centimetres along a vertical ice face. For instance, Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) observed that the transition to turbulence typically occurs after a short vertical distance. The present study therefore focuses on this laminar regime to gain fundamental insight into BL development prior to the onset of turbulence, without the additional complexity of a fully developed turbulent flow.

The focus of the present work is on the laminar (or quasi-laminar) regime of vertical ice-face melting (or dissolution/ablation) in ambient warmer water with and without salinity. This effort involves a combination of experiments and direct numerical simulation (DNS). Although there exists prior work where melting is driven by ambient temperature alone (i.e. freshwater), relatively less focus has been on ambient saline water – this is especially relevant to Antarctic conditions which are characterised by high salinity and low ambient temperatures. When considering early experimental works that investigated the laminar BL of a melting vertical ice face, Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) and Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982b ) are the leading studies. Here, they identified flow regimes based on ambient temperatures and salinities. Ice-face ablation and associated BL flow dynamics are further explored under different ice-face angles and ambient environments under turbulent flow conditions in various relatively recent studies (Kerr & McConnochie Reference Kerr and McConnochie2015; Gayen, Griffiths & Kerr Reference Gayen, Griffiths and Kerr2016; McConnochie & Kerr Reference McConnochie and Kerr2016a , Reference McConnochie and Kerrb ; McConnochie et al. Reference McConnochie2018; Mondal et al. Reference Mondal, Gayen, Griffiths and Kerr2019; Sweetman et al. Reference Sweetman, Shakespeare, Stewart and McConnochie2024). However, almost no measurements of the temperature and velocity profiles exist within the BL. These are key to understanding the dynamics of the flow and melt-rate scaling. Importantly, if the flow is driven solely by either temperature or salinity, the dynamics is simpler and the flow is uni-directional. Most studies have focused on this scenario (e.g. Ostrach Reference Ostrach1952). Herein we demonstrate that under realistic Antarctic conditions both temperature and salinity play significant roles, and can lead to a bi-directional flow (e.g. Josberger & Martin Reference Josberger and Martin1981; Nilson Reference Nilson1985). Here, a salinity-driven upward flow close to the ice sheet is accompanied by a temperature-driven downward flow away from the ice sheet (see figure 1 ai for uni- and 1 aii for bi-directional flow schematics). This bi-directional flow non-trivially affects the otherwise simpler scaling of the melt rate under laminar conditions.

Figure 1. (a) Boundary-layer structure adjacent to an ablating vertical ice face, with (i) uni-directional flow (where temperature and/or salinity forcing are in the same direction) and (ii) bi-directional or counter-current flow (with opposing buoyancy forcing). (b) Experimental cases (see table 1) on a T–S diagram (case 1 ![]() :

:

![]() $S_\infty =0$

g kg−1,

$S_\infty =0$

g kg−1,

![]() $T_\infty =20^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

; case 2

$T_\infty =20^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

; case 2 ![]() :

:

![]() $S_\infty =0$

g kg−1,

$S_\infty =0$

g kg−1,

![]() $T_\infty =15^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

; case 3

$T_\infty =15^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

; case 3 ![]() :

:

![]() $S_\infty =0$

g kg−1,

$S_\infty =0$

g kg−1,

![]() $T_\infty =10^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

; case 4

$T_\infty =10^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

; case 4 ![]() :

:

![]() $S_\infty =0$

g kg−1,

$S_\infty =0$

g kg−1,

![]() $T_\infty =4^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

; case 5

$T_\infty =4^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

; case 5 ![]() :

:

![]() $S_\infty =34$

g kg−1,

$S_\infty =34$

g kg−1,

![]() $T_\infty =4^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

; and case 6

$T_\infty =4^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

; and case 6 ![]() :

:

![]() $S_\infty =34$

g kg−1,

$S_\infty =34$

g kg−1,

![]() $T_\infty =2^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

), and flow regimes with region I (

$T_\infty =2^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

), and flow regimes with region I (

![]() ${\varLambda } \lt 0$

) and region II (

${\varLambda } \lt 0$

) and region II (

![]() ${\varLambda } \gt 0$

). Here,

${\varLambda } \gt 0$

). Here,

![]() $T_\textit{md}$

(blue solid line) and

$T_\textit{md}$

(blue solid line) and

![]() $T_\textit{fp}$

(black solid line) represent temperature corresponding to maximum density and freezing point temperature at different salinities, respectively. (c) Density variation of freshwater (

$T_\textit{fp}$

(black solid line) represent temperature corresponding to maximum density and freezing point temperature at different salinities, respectively. (c) Density variation of freshwater (

![]() $S=0$

) with temperature. Symbols represent cases 1, 2, 3 and 4 (these are also presented in table 1).

$S=0$

) with temperature. Symbols represent cases 1, 2, 3 and 4 (these are also presented in table 1).

Temperature and salinity affect the flow and melt rates differently. As discussed extensively (e.g. Woods Reference Woods1992; Kerr Reference Kerr1994a , Reference Kerrb ; Wells & Worster Reference Wells and Worster2011), in cases where the diffusion caused by temperature difference between ice and ambient water is the main driver, the process is termed ‘melting’, whereas salinity-difference-driven flow is referred to as ‘dissolution’. In both cases, however, when one neglects the heat and salt transfer into the ice, the ice and melt-water interface has to satisfy the continuity of heat and salinity flux:

In (1.1) and (1.2),

![]() $\rho _{\textit{ice}}$

and

$\rho _{\textit{ice}}$

and

![]() $\rho$

are the densities of ice and water,

$\rho$

are the densities of ice and water,

![]() $T$

(

$T$

(

![]() $^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

) and

$^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

) and

![]() $S$

(grams of salt per kilogram of water or ‰) are temperature and salinity with

$S$

(grams of salt per kilogram of water or ‰) are temperature and salinity with

![]() $x$

normal to the ice and pointing into the water,

$x$

normal to the ice and pointing into the water,

![]() $\kappa _T$

and

$\kappa _T$

and

![]() $\kappa _S$

are temperature and salinity diffusivity (

$\kappa _S$

are temperature and salinity diffusivity (

![]() $\rm m^2\,s^{- 1}$

),

$\rm m^2\,s^{- 1}$

),

![]() $c_w$

and

$c_w$

and

![]() $L$

are the specific heat (

$L$

are the specific heat (

![]() $\rm J\,(\rm kg\,^{\,\circ} \text{C})^{- 1}$

) and latent heat of water (

$\rm J\,(\rm kg\,^{\,\circ} \text{C})^{- 1}$

) and latent heat of water (

![]() $\rm J\,kg^{- 1}$

) and

$\rm J\,kg^{- 1}$

) and

![]() $V$

is the melt rate (

$V$

is the melt rate (

![]() $\rm m\,s^{- 1}$

). The effect of the conductive heat flux into the ice is discussed in Kerr & McConnochie (Reference Kerr and McConnochie2015) and is negligible for ice temperatures close to the interface temperature. (For the experiments in this study, heat transfer into the ice is estimated to be less than

$\rm m\,s^{- 1}$

). The effect of the conductive heat flux into the ice is discussed in Kerr & McConnochie (Reference Kerr and McConnochie2015) and is negligible for ice temperatures close to the interface temperature. (For the experiments in this study, heat transfer into the ice is estimated to be less than

![]() $4\,\%$

of the heat required for ice melting, which has a negligible impact on the interface temperature and ice melt-rate estimations.) Note also that, at the interface,

$4\,\%$

of the heat required for ice melting, which has a negligible impact on the interface temperature and ice melt-rate estimations.) Note also that, at the interface,

![]() $T=T_i$

and

$T=T_i$

and

![]() $S=S_i$

are connected by the freezing point depression equation of saltwater:

$S=S_i$

are connected by the freezing point depression equation of saltwater:

where

![]() $a_s\approx -6 \times 10^{-2}{\rm ^\circ\, C}\,$

‰−1 (Josberger & Martin Reference Josberger and Martin1981). As a consequence of the freezing point depression equation as well as (1.1) and (1.2), when an ice face dissolves in saline water, the salinity of the water adjacent to the interface remains non-zero, even though the ice block itself is made of freshwater. The governing equations for the flow field, expressing the conservation of momentum and mass and the transport of two scalars, along with (1.1) and (1.2) govern the melt-water BL dynamics.

$a_s\approx -6 \times 10^{-2}{\rm ^\circ\, C}\,$

‰−1 (Josberger & Martin Reference Josberger and Martin1981). As a consequence of the freezing point depression equation as well as (1.1) and (1.2), when an ice face dissolves in saline water, the salinity of the water adjacent to the interface remains non-zero, even though the ice block itself is made of freshwater. The governing equations for the flow field, expressing the conservation of momentum and mass and the transport of two scalars, along with (1.1) and (1.2) govern the melt-water BL dynamics.

For single-component flow, such as temperature- or salinity-driven flow, self-similar solutions of the BL equations exist (e.g. Ostrach Reference Ostrach1952; Nilson Reference Nilson1985; Wells & Worster Reference Wells and Worster2011) whereas Nilson (Reference Nilson1985) tried to obtain some non-self-similar solutions where both temperature and salinity effects are significant. Analytical works usually assume constant properties, such as

![]() $\kappa _T$

and

$\kappa _T$

and

![]() $\kappa _S$

, and a linear variation of density dependence on temperature and salinity, although exceptions exist (e.g. Gebhart & Mollendorf Reference Gebhart and Mollendorf1977) that take into consideration the density maxima at

$\kappa _S$

, and a linear variation of density dependence on temperature and salinity, although exceptions exist (e.g. Gebhart & Mollendorf Reference Gebhart and Mollendorf1977) that take into consideration the density maxima at

![]() $T\approx 4^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

for low salinity. Experimental progress, however, has been limited because of the difficulty in measuring temperature (and/or salinity) and velocity distribution in water adjacent to a melting ice face. Nevertheless, limited velocity measurements have been carried out. Wilson & Vyas (Reference Wilson and Vyas1979) adopted a technique that uses a pH indicator (thymol blue) that can work as a coloured marker to track the flow; Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982a

) and Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) estimated flow velocity using long-exposure photography of illuminated particles; and McConnochie & Kerr (Reference McConnochie and Kerr2016b

) used a shadowgraph turbulent eddy tracking technique to estimate maximum plume velocity. As far as BL temperature data are concerned, some of these studies provide ice–water interface and far-field temperatures measured using stationary thermistors or thermocouples (Bendell & Gebhart Reference Bendell and Gebhart1976; Josberger & Martin Reference Josberger and Martin1981; Carey & Gebhart Reference Carey and Gebhart1982a

; McConnochie & Kerr Reference McConnochie and Kerr2016b

; McConnochie et al. Reference McConnochie2018). However, temperature profiles across the BL flow are not available in previous studies. In all experimental studies that measured ice ablation rate, the position of the ice–water interface is obtained as a function of time, which has been used to estimate the melt rate (Josberger & Martin Reference Josberger and Martin1981; Kerr & McConnochie Reference Kerr and McConnochie2015). Obtaining velocity and temperature profile measurements within the BL has been a significant challenge because of the small measurement domain (

$T\approx 4^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

for low salinity. Experimental progress, however, has been limited because of the difficulty in measuring temperature (and/or salinity) and velocity distribution in water adjacent to a melting ice face. Nevertheless, limited velocity measurements have been carried out. Wilson & Vyas (Reference Wilson and Vyas1979) adopted a technique that uses a pH indicator (thymol blue) that can work as a coloured marker to track the flow; Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982a

) and Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) estimated flow velocity using long-exposure photography of illuminated particles; and McConnochie & Kerr (Reference McConnochie and Kerr2016b

) used a shadowgraph turbulent eddy tracking technique to estimate maximum plume velocity. As far as BL temperature data are concerned, some of these studies provide ice–water interface and far-field temperatures measured using stationary thermistors or thermocouples (Bendell & Gebhart Reference Bendell and Gebhart1976; Josberger & Martin Reference Josberger and Martin1981; Carey & Gebhart Reference Carey and Gebhart1982a

; McConnochie & Kerr Reference McConnochie and Kerr2016b

; McConnochie et al. Reference McConnochie2018). However, temperature profiles across the BL flow are not available in previous studies. In all experimental studies that measured ice ablation rate, the position of the ice–water interface is obtained as a function of time, which has been used to estimate the melt rate (Josberger & Martin Reference Josberger and Martin1981; Kerr & McConnochie Reference Kerr and McConnochie2015). Obtaining velocity and temperature profile measurements within the BL has been a significant challenge because of the small measurement domain (

![]() ${\approx}1$

mm salinity BL and

${\approx}1$

mm salinity BL and

![]() $1{-}2$

cm thermal and velocity BL), limited options for measuring temperature and the small velocity magnitudes adjacent to a receding ice interface. Here, we have adapted the techniques of molecular tagging velocimetry (MTV) and thermometry (MTT), respectively, for velocity and temperature measurements (Gendrich, Koochesfahani & Nocera Reference Gendrich, Koochesfahani and Nocera1997; Hu & Koochesfahani Reference Hu and Koochesfahani2006; Agrawal et al. Reference Agrawal, Ramesh, Zimmerman, Philip and Klewicki2021) across the BL to the present low-temperature and velocity situation (detailed in § 3) for both far-field salinity

$1{-}2$

cm thermal and velocity BL), limited options for measuring temperature and the small velocity magnitudes adjacent to a receding ice interface. Here, we have adapted the techniques of molecular tagging velocimetry (MTV) and thermometry (MTT), respectively, for velocity and temperature measurements (Gendrich, Koochesfahani & Nocera Reference Gendrich, Koochesfahani and Nocera1997; Hu & Koochesfahani Reference Hu and Koochesfahani2006; Agrawal et al. Reference Agrawal, Ramesh, Zimmerman, Philip and Klewicki2021) across the BL to the present low-temperature and velocity situation (detailed in § 3) for both far-field salinity

![]() $S_\infty =0$

and

$S_\infty =0$

and

![]() $S_\infty = 34$

‰ corresponding to seawater and different far-field temperatures (

$S_\infty = 34$

‰ corresponding to seawater and different far-field temperatures (

![]() $T_\infty$

).

$T_\infty$

).

As a complement to experiments, DNS can generally provide much greater details. Owing to the complexity of the problem, however, DNS studies addressing vertical ice-face melting are sparse. Studies such as Gayen et al. (Reference Gayen, Griffiths and Kerr2016), which investigated turbulent BLs along a vertical ice face, and Mondal et al. (Reference Mondal, Gayen, Griffiths and Kerr2019), which focused on inclined ice, have previously examined ice-face ablation driven by natural convection. These include a linear equation of state (EoS) and smaller Schmidt numbers. More recently, Yang et al. (Reference Yang, Howland, Liu, Verzicco and Lohse2023) performed DNS with ambient stratification, but relatively large ambient temperature (

![]() $20^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

) and low salinity (up to

$20^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

) and low salinity (up to

![]() $15$

‰). Ice melting under laminar natural convection at realistic Antarctic conditions remains largely unexplored, and the present DNS incorporating linear as well as nonlinear EoS and other realistic non-dimensional parameters aims to fill some of this gap.

$15$

‰). Ice melting under laminar natural convection at realistic Antarctic conditions remains largely unexplored, and the present DNS incorporating linear as well as nonlinear EoS and other realistic non-dimensional parameters aims to fill some of this gap.

The objectives of this study are twofold. The first is to obtain experimental velocity and temperature profiles along with simultaneous melt-rate measurements, and carry out DNS of the same physical domain. The second objective is to study the velocity and temperature profiles as well as the melt rates and their scaling with height for a range of ambient temperatures and salinities, and thus clarify the role of opposing buoyancy arising due to temperature and salinity in the BL dynamics. The rest of this paper is organised as follows: In § 2 the relevant non-dimensional numbers and the expected flow regimes for both uni- and bi-directional flow are discussed. We also present a method to evaluate the possible flow scenarios appropriate to Antarctic conditions with only the knowledge of far-field temperature and salinity. Next, the experimental set-up and modifications to previous MTV/MTT implementations are outlined in § 3. These modifications allow us to measure low velocities as well as temperatures within the melt BL. Details of the DNS that mimic our experimental set-up are discussed in § 4. In § 5 we present the velocity and temperature data from the experiments and simulations. Finally, the melt-rate data as well as expected scalings are discussed in § 6 before the summary and conclusions are presented in § 7.

2. Governing non-dimensional numbers and relevance to Antarctic conditions

2.1. Governing non-dimensional numbers

For a single-component flow, say, driven only by the difference between ambient and interface temperature (

![]() $T_\infty$

and

$T_\infty$

and

![]() $T_i$

, respectively), the relevant non-dimensional parameters are the Prandtl and Grashof numbers:

$T_i$

, respectively), the relevant non-dimensional parameters are the Prandtl and Grashof numbers:

where

![]() $\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid,

$\nu$

is the kinematic viscosity of the fluid,

![]() $z$

is the vertical distance with origin at the bottom (see figure 1

ai and 1

aii),

$z$

is the vertical distance with origin at the bottom (see figure 1

ai and 1

aii),

![]() $g$

is the gravitational acceleration and

$g$

is the gravitational acceleration and

![]() $\alpha \equiv -(1/\rho )(\partial \rho /\partial T)$

is the thermal expansion coefficient. It is also common to define

$\alpha \equiv -(1/\rho )(\partial \rho /\partial T)$

is the thermal expansion coefficient. It is also common to define

![]() $\textit{Gr}_H$

based on the total height of the ice face

$\textit{Gr}_H$

based on the total height of the ice face

![]() $H$

. Based on

$H$

. Based on

![]() $H=8.5$

cm for our set-up, we have

$H=8.5$

cm for our set-up, we have

![]() $ 3.6\times 10^6 \lessapprox \textit{Gr}_H \lessapprox 9.7\times 10^7$

and

$ 3.6\times 10^6 \lessapprox \textit{Gr}_H \lessapprox 9.7\times 10^7$

and

![]() $7 \lessapprox \textit{Pr} \lessapprox 13$

. Also, it is interesting to represent

$7 \lessapprox \textit{Pr} \lessapprox 13$

. Also, it is interesting to represent

![]() $\textit{Gr}_H$

as a ratio of viscous to buoyancy time scales:

$\textit{Gr}_H$

as a ratio of viscous to buoyancy time scales:

![]() $\sqrt {\textit{Gr}_H} = (H^2/\nu )/\sqrt {H/g'}$

, where reduced gravity

$\sqrt {\textit{Gr}_H} = (H^2/\nu )/\sqrt {H/g'}$

, where reduced gravity

![]() $g':=g\alpha (T_\infty -T_i)$

, and

$g':=g\alpha (T_\infty -T_i)$

, and

![]() $\sqrt [4]{\textit{Gr}_H} = H/\sqrt [4]{\nu ^2 H/g'}$

as a ratio of length scales (where the denominator is the viscous-gravity length scale

$\sqrt [4]{\textit{Gr}_H} = H/\sqrt [4]{\nu ^2 H/g'}$

as a ratio of length scales (where the denominator is the viscous-gravity length scale

![]() $l_T$

in (A6) without the numerical factor and

$l_T$

in (A6) without the numerical factor and

![]() $z \mapsto H$

). For example, in our case

$z \mapsto H$

). For example, in our case

![]() $1900\lessapprox \sqrt {\textit{Gr}_H} \lessapprox 9850$

and

$1900\lessapprox \sqrt {\textit{Gr}_H} \lessapprox 9850$

and

![]() $45 \lessapprox \sqrt [4]{\textit{Gr}_H} \lessapprox 100$

, which further highlights the importance of buoyancy.

$45 \lessapprox \sqrt [4]{\textit{Gr}_H} \lessapprox 100$

, which further highlights the importance of buoyancy.

Addition of a second component, say salinity, to the existing temperature adds two dimensional quatities:

![]() $S_\infty$

or the difference of far-field to interface salinity

$S_\infty$

or the difference of far-field to interface salinity

![]() $(S_\infty -S_i)$

and

$(S_\infty -S_i)$

and

![]() $\kappa _S$

, giving rise to two more non-dimensional groups:

$\kappa _S$

, giving rise to two more non-dimensional groups:

These are, respectively, the ratio of density changes owing to temperature and salinity, and Schmidt and Lewis numbers, where

![]() $\beta \equiv (1/\rho )(\partial \rho /\partial S)$

is the haline contraction coefficient and

$\beta \equiv (1/\rho )(\partial \rho /\partial S)$

is the haline contraction coefficient and

![]() $\rho _0$

is reference density. For our cases

$\rho _0$

is reference density. For our cases

![]() ${\varLambda }\approx 1/40$

,

${\varLambda }\approx 1/40$

,

![]() $\textit{Sc}\approx 2000$

and

$\textit{Sc}\approx 2000$

and

![]() $\textit{Le} \approx 200$

.

$\textit{Le} \approx 200$

.

For nonlinear density variations, Gebhart & Mollendorf (Reference Gebhart and Mollendorf1977) and Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982b ) introduced another non-dimensional number:

where

![]() $T_\textit{md}$

is the temperature where the maximum density occurs. Parameter

$T_\textit{md}$

is the temperature where the maximum density occurs. Parameter

![]() $R$

is a stronger function of salinity at lower

$R$

is a stronger function of salinity at lower

![]() $S$

(see figure 1

b and 1

c). This is because, at low

$S$

(see figure 1

b and 1

c). This is because, at low

![]() $S$

, the value of

$S$

, the value of

![]() $T_\textit{md}$

deviates significantly from

$T_\textit{md}$

deviates significantly from

![]() $T_i$

as

$T_i$

as

![]() $S$

decreases and it provides an indirect measure of how significant the nonlinear effects of temperature are on the density for a given

$S$

decreases and it provides an indirect measure of how significant the nonlinear effects of temperature are on the density for a given

![]() $T_i$

and

$T_i$

and

![]() $T_\infty$

. Further,

$T_\infty$

. Further,

![]() $R$

is useful to predict the direction of flow for different ambient conditions when interface conditions are known (Gebhart & Jaluria Reference Gebhart and Jaluria1988), especially for low-salinity cases. These flow regimes are now discussed.

$R$

is useful to predict the direction of flow for different ambient conditions when interface conditions are known (Gebhart & Jaluria Reference Gebhart and Jaluria1988), especially for low-salinity cases. These flow regimes are now discussed.

2.2. Flow regimes

When an ice face is in contact with saline water, the water adjacent to the ice–water interface is subjected to cooling and dilution. Cooling induces a thermal BL within which the temperature varies from the freezing point temperature

![]() $T_\textit{fp}(S_i)$

(shown in figure 1

b) to the ambient water temperature (

$T_\textit{fp}(S_i)$

(shown in figure 1

b) to the ambient water temperature (

![]() $T_\infty$

). Owing to dilution, a salinity BL forms where water gets less saline closer to the ice due to freshwater released from the melting ice. These thermal and saline BLs are depicted in figure 1(ai) and 1(aii). Importantly, since salt has very low diffusivity compared with heat (

$T_\infty$

). Owing to dilution, a salinity BL forms where water gets less saline closer to the ice due to freshwater released from the melting ice. These thermal and saline BLs are depicted in figure 1(ai) and 1(aii). Importantly, since salt has very low diffusivity compared with heat (

![]() $\textit{Le} =\kappa _T/\kappa _S \approx 200$

), the saline BL thickness (

$\textit{Le} =\kappa _T/\kappa _S \approx 200$

), the saline BL thickness (

![]() $\delta _S$

) is about 14 times smaller (assuming

$\delta _S$

) is about 14 times smaller (assuming

![]() $\delta _S/\delta _T\approx \textit{Le}^{-1/2}$

, which is discussed in § 6) compared with the thickness of the thermal BL (

$\delta _S/\delta _T\approx \textit{Le}^{-1/2}$

, which is discussed in § 6) compared with the thickness of the thermal BL (

![]() $\delta _T$

). Although the contribution of salinity to the change in density is large compared with the temperature (

$\delta _T$

). Although the contribution of salinity to the change in density is large compared with the temperature (

![]() ${\varLambda }\approx 1/40$

), owing to the low diffusivity of salt, density variations due to salt only affect a very thin layer of water closest to the interface. On the other hand, despite having a relatively small contribution to the density variation, the thermal BL affects density variations across a broader domain than the salinity BL.

${\varLambda }\approx 1/40$

), owing to the low diffusivity of salt, density variations due to salt only affect a very thin layer of water closest to the interface. On the other hand, despite having a relatively small contribution to the density variation, the thermal BL affects density variations across a broader domain than the salinity BL.

Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) used experiments and existing similarity solutions to map the BL forming next to a melting vertical ice face. The mapping was carried out on a temperature–salinity (

![]() $T_\infty ,\,S_\infty$

) diagram like that shown in figure 1(b). Although the map was prepared mostly for turbulent flows, as discussed later, some features are relevant for laminar flows. Importantly, we draw connections between this map on the (

$T_\infty ,\,S_\infty$

) diagram like that shown in figure 1(b). Although the map was prepared mostly for turbulent flows, as discussed later, some features are relevant for laminar flows. Importantly, we draw connections between this map on the (

![]() $T_\infty ,\,S_\infty )$

plane and the more informative non-dimensional

$T_\infty ,\,S_\infty )$

plane and the more informative non-dimensional

![]() $({\varLambda },\,\textit{Le})$

plane description of Nilson (Reference Nilson1985).

$({\varLambda },\,\textit{Le})$

plane description of Nilson (Reference Nilson1985).

In figure 1(b), the temperature at maximum density for each salinity is the line

![]() $T_\textit{md}$

(in blue colour, where

$T_\textit{md}$

(in blue colour, where

![]() $R=0$

; equation (2.3)) and the freezing point temperature line is

$R=0$

; equation (2.3)) and the freezing point temperature line is

![]() $T_\textit{fp}$

(in black colour) that separates the ice and water states. Depending on where

$T_\textit{fp}$

(in black colour) that separates the ice and water states. Depending on where

![]() $T_\infty$

and

$T_\infty$

and

![]() $S_\infty$

lie on the T–S diagram, Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) report different BL regimes. When the ambient conditions are in region I, enclosed by

$S_\infty$

lie on the T–S diagram, Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) report different BL regimes. When the ambient conditions are in region I, enclosed by

![]() $T_\textit{md}$

and

$T_\textit{md}$

and

![]() $T_\textit{fp}$

,

$T_\textit{fp}$

,

![]() $\varLambda$

is negative. This is because

$\varLambda$

is negative. This is because

![]() $\Delta \rho _T := \alpha \rho _0 (T_\infty -T)$

is negative as

$\Delta \rho _T := \alpha \rho _0 (T_\infty -T)$

is negative as

![]() $\alpha$

is negative in this region, and

$\alpha$

is negative in this region, and

![]() $\Delta \rho _S:= {\beta } \rho _0 (S_\infty -S)$

is always positive because freshwater is always less dense relative to saltwater at the same temperature. That is, both salt and temperature produce less dense water, favouring an upward uni-directional BL flow. Due to this uniformity of the flow, similarity solutions exist for the laminar BL equations in this region (see (A1a

) and (A1b

)).

$\Delta \rho _S:= {\beta } \rho _0 (S_\infty -S)$

is always positive because freshwater is always less dense relative to saltwater at the same temperature. That is, both salt and temperature produce less dense water, favouring an upward uni-directional BL flow. Due to this uniformity of the flow, similarity solutions exist for the laminar BL equations in this region (see (A1a

) and (A1b

)).

Figure 2. (a) Relative buoyancy–diffusivity diagram (

![]() $\varLambda {-}\textit{Le}$

) showing flow regimes. Here (

$\varLambda {-}\textit{Le}$

) showing flow regimes. Here (![]() )

)

![]() $\varLambda \textit{Le}= 1$

, (

$\varLambda \textit{Le}= 1$

, (![]() )

)

![]() $\varLambda \textit{Le}^{1/2} = 1$

and (

$\varLambda \textit{Le}^{1/2} = 1$

and (![]() )

)

![]() $\varLambda \textit{Le}^{1/3} = 1$

. Contours represent

$\varLambda \textit{Le}^{1/3} = 1$

. Contours represent

![]() $\varLambda \textit{Le}^{1/2}$

. Symbols: filled

$\varLambda \textit{Le}^{1/2}$

. Symbols: filled

![]() $\diamond$

and filled

$\diamond$

and filled

![]() $\vartriangleleft$

show experimental data for cases 5 and 6, respectively. Also shown are laminar bi-directional experimental results of Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) in filled yellow

$\vartriangleleft$

show experimental data for cases 5 and 6, respectively. Also shown are laminar bi-directional experimental results of Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) in filled yellow

![]() $\triangledown$

and of Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982a

) in filled green

$\triangledown$

and of Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982a

) in filled green

![]() $\triangle$

for comparison. Analytical values of

$\triangle$

for comparison. Analytical values of

![]() $\varLambda$

obtained using (2.6) are shown in the colour bar for ambient temperatures

$\varLambda$

obtained using (2.6) are shown in the colour bar for ambient temperatures

![]() $T_\infty =-2^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

to

$T_\infty =-2^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

to

![]() $4^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

(blue to red colour) expected in the context of Antarctic ice melting with higher (lower) temperatures in red (blue). (b) Zoomed-in view of (a). (c) Temperature

$4^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

(blue to red colour) expected in the context of Antarctic ice melting with higher (lower) temperatures in red (blue). (b) Zoomed-in view of (a). (c) Temperature

![]() $T_i$

obtained from solving (2.6) for different ambient conditions (labels on the curves denote salinity). Also shown are the experimental results of Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982a

) (filled green

$T_i$

obtained from solving (2.6) for different ambient conditions (labels on the curves denote salinity). Also shown are the experimental results of Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982a

) (filled green

![]() $\triangle$

) and numerical results of Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982b

) (open green

$\triangle$

) and numerical results of Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982b

) (open green

![]() $\triangle$

) for

$\triangle$

) for

![]() $S_\infty = 10$

g kg−1. The experimental data of Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) are indicated by filled yellow

$S_\infty = 10$

g kg−1. The experimental data of Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) are indicated by filled yellow

![]() $\triangledown$

(for

$\triangledown$

(for

![]() $S_\infty = 34.4$

g kg−1). The DNS results of this study for case 5 and case 6 are shown as open

$S_\infty = 34.4$

g kg−1). The DNS results of this study for case 5 and case 6 are shown as open

![]() $\diamond$

and

$\diamond$

and

![]() $\vartriangleleft$

, respectively (both for

$\vartriangleleft$

, respectively (both for

![]() $S_\infty = 34$

g kg−1).

$S_\infty = 34$

g kg−1).

When the ambient condition shifts into region II, having a high salinity and relatively low temperature,

![]() $\Delta \rho _T$

gradually becomes negative, resulting in

$\Delta \rho _T$

gradually becomes negative, resulting in

![]() ${\varLambda } \gt 0$

. In this region, buoyancy forces from salinity (closer to the wall) and temperature (farther from the wall) oppose each other. This can result in bi-directional or counter-current flows. However, Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982b

) showed through numerical calculations that even with opposing buoyancy forces, uni-directional upward flow can exist for some cases within the region where the salinity buoyancy force dominates over the thermal buoyancy force. This shows that the limits of counter-current flow are less apparent on a

${\varLambda } \gt 0$

. In this region, buoyancy forces from salinity (closer to the wall) and temperature (farther from the wall) oppose each other. This can result in bi-directional or counter-current flows. However, Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982b

) showed through numerical calculations that even with opposing buoyancy forces, uni-directional upward flow can exist for some cases within the region where the salinity buoyancy force dominates over the thermal buoyancy force. This shows that the limits of counter-current flow are less apparent on a

![]() $T_\infty {-} S_\infty$

diagram. Nilson (Reference Nilson1985) obtained these limits on the

$T_\infty {-} S_\infty$

diagram. Nilson (Reference Nilson1985) obtained these limits on the

![]() $({\varLambda },\,\textit{Le})$

plane as shown in figure 2(a). Starting with a dominant upwards salinity-driven flow, an incipient temperature-driven downward flow (i.e. an overall bi-directional flow) appears when

$({\varLambda },\,\textit{Le})$

plane as shown in figure 2(a). Starting with a dominant upwards salinity-driven flow, an incipient temperature-driven downward flow (i.e. an overall bi-directional flow) appears when

![]() ${\varLambda } \textit{Le}\approx 1$

. If, however, there is a dominant temperature-driven downward flow an incipient salinity-driven upward flow adjacent to the wall will result when

${\varLambda } \textit{Le}\approx 1$

. If, however, there is a dominant temperature-driven downward flow an incipient salinity-driven upward flow adjacent to the wall will result when

![]() ${\varLambda } \textit{Le}^{1/3} \approx 1$

. Appendix A provides a derivation of these limits starting from the BL equations. These limits of upward and downward flows are presented in figure 2(a). They divide the

${\varLambda } \textit{Le}^{1/3} \approx 1$

. Appendix A provides a derivation of these limits starting from the BL equations. These limits of upward and downward flows are presented in figure 2(a). They divide the

![]() $({\varLambda },\,\textit{Le})$

plane into three regions: up-flow; counter-flow or bi-directional flow; and down-flow.

$({\varLambda },\,\textit{Le})$

plane into three regions: up-flow; counter-flow or bi-directional flow; and down-flow.

An estimate of the demarcating line between the upward saline-buoyancy-dominated and the downward thermal-buoyancy-dominated regimes can be obtained quite straightforwardly by evaluating the relative buoyancy strengths. Net buoyancy is not governed only by

![]() $\Delta \rho _T$

and

$\Delta \rho _T$

and

![]() $\Delta \rho _S$

, i.e.

$\Delta \rho _S$

, i.e.

![]() $\varLambda$

, rather by the density difference acting over the respective BL thickness

$\varLambda$

, rather by the density difference acting over the respective BL thickness

![]() $\delta _T$

and

$\delta _T$

and

![]() $\delta _S$

. Therefore, it is the ratio

$\delta _S$

. Therefore, it is the ratio

that determines the relative strength of temperature and salinity within the BL. Not surprisingly, the line

![]() ${\varLambda } \textit{Le}^{1/2}$

bisects the bi-directional flow region in figure 2(a) as shown in the blue dashed line. In figure 2(a), we compare the experimental results of Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) and Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982a

), where laminar bi-directional or marginally bi-directional flows were observed, in the

${\varLambda } \textit{Le}^{1/2}$

bisects the bi-directional flow region in figure 2(a) as shown in the blue dashed line. In figure 2(a), we compare the experimental results of Josberger & Martin (Reference Josberger and Martin1981) and Carey & Gebhart (Reference Carey and Gebhart1982a

), where laminar bi-directional or marginally bi-directional flows were observed, in the

![]() $\varLambda$

–

$\varLambda$

–

![]() $\textit{Le}$

plane. As shown in the figure, these data fall within the region corresponding to counter-flow, providing confidence in the validity of the formulation.

$\textit{Le}$

plane. As shown in the figure, these data fall within the region corresponding to counter-flow, providing confidence in the validity of the formulation.

Since natural convection adjacent to Antarctic ice shelves is one of the motivations of the present work, in the following we estimate the locations of Antarctic data within the

![]() $({\varLambda },\,\textit{Le})$

plane in figure 2(a).

$({\varLambda },\,\textit{Le})$

plane in figure 2(a).

2.3. Laminar flow at Antarctic conditions

Only

![]() $T_\infty$

and

$T_\infty$

and

![]() $S_\infty$

conditions are known for Antarctic conditions. If, however, one can estimate

$S_\infty$

conditions are known for Antarctic conditions. If, however, one can estimate

![]() $T_i$

and

$T_i$

and

![]() $S_i$

,

$S_i$

,

![]() $\varLambda$

and

$\varLambda$

and

![]() $\textit{Le}$

can be estimated. Towards this end, we assume that within the laminar BL both temperature and salinity vary linearly across the respective BLs, and, therefore, (1.1) and (1.2) can be written in terms of interface and far-field conditions:

$\textit{Le}$

can be estimated. Towards this end, we assume that within the laminar BL both temperature and salinity vary linearly across the respective BLs, and, therefore, (1.1) and (1.2) can be written in terms of interface and far-field conditions:

Dividing the above two equations, substituting

![]() $({\delta _T}/{\delta _S})^2 = {\kappa _T}/{\kappa _S}$

and replacing

$({\delta _T}/{\delta _S})^2 = {\kappa _T}/{\kappa _S}$

and replacing

![]() $S_i$

with freezing point depression

$S_i$

with freezing point depression

![]() $T_i/a_s$

results in

$T_i/a_s$

results in

\begin{equation} T_i^2\left (\frac {\textit{Le}^{1/2} c_w}{a_s L}\right ) -T_i\! \left (\frac {1}{a_s} +\frac {\textit{Le}^{1/2} c_w T_\infty }{a_s L}\right ) + S_\infty =0. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} T_i^2\left (\frac {\textit{Le}^{1/2} c_w}{a_s L}\right ) -T_i\! \left (\frac {1}{a_s} +\frac {\textit{Le}^{1/2} c_w T_\infty }{a_s L}\right ) + S_\infty =0. \end{equation}

The above quadratic equation can be solved for

![]() $T_i$

(and hence

$T_i$

(and hence

![]() $S_i$

) by knowing the other quantities. In passing we note that a quadratic equation for

$S_i$

) by knowing the other quantities. In passing we note that a quadratic equation for

![]() $S_i$

for turbulent flow (using different assumptions) is obtained by McPhee, Morison & Nilsen (Reference McPhee, Morison and Nilsen2008). The approximate values of

$S_i$

for turbulent flow (using different assumptions) is obtained by McPhee, Morison & Nilsen (Reference McPhee, Morison and Nilsen2008). The approximate values of

![]() $\kappa _T=1.4\times 10^{-7}$

(Nayar et al. Reference Nayar, Panchanathan, McKinley and Lienhard2014) and

$\kappa _T=1.4\times 10^{-7}$

(Nayar et al. Reference Nayar, Panchanathan, McKinley and Lienhard2014) and

![]() $\kappa _S=7\times 10^{-10}$

(Caldwell Reference Caldwell1974) give

$\kappa _S=7\times 10^{-10}$

(Caldwell Reference Caldwell1974) give

![]() $\textit{Le}=200$

. The roots of (2.6) between

$\textit{Le}=200$

. The roots of (2.6) between

![]() $0$

and

$0$

and

![]() $a_s S_\infty$

are plotted in figure 2(c) along with some existing data for different salinities (Josberger & Martin Reference Josberger and Martin1981; Carey & Gebhart Reference Carey and Gebhart1982a

,

Reference Carey and Gebhartb

). These show a reasonable agreement between the solution of (2.6) and the data. Note that this root is always zero for the freshwater case (

$a_s S_\infty$

are plotted in figure 2(c) along with some existing data for different salinities (Josberger & Martin Reference Josberger and Martin1981; Carey & Gebhart Reference Carey and Gebhart1982a

,

Reference Carey and Gebhartb

). These show a reasonable agreement between the solution of (2.6) and the data. Note that this root is always zero for the freshwater case (

![]() $S_\infty =0$

). For saltwater,

$S_\infty =0$

). For saltwater,

![]() $T_i$

increases with increasing

$T_i$

increases with increasing

![]() $T_\infty$

. Further, for a given

$T_\infty$

. Further, for a given

![]() $T_\infty$

,

$T_\infty$

,

![]() $T_i$

decreases with increasing

$T_i$

decreases with increasing

![]() $S_\infty$

. We should mention that the validity of the assumption

$S_\infty$

. We should mention that the validity of the assumption

![]() $\delta _T / \delta _S = \textit{Le}^{1/2}$

leading to (2.6) may not be theoretically accurate under certain ambient conditions where the flow becomes bi-directional resulting in two distinct velocity scales within the BL, as discussed further in § 6. However, as shown in figure 2(c), the formulation in (2.6) is able to reproduce both numerical and experimental observations, even when the flow becomes bi-directional (because the two aforementioned velocity scales are of similar magnitude; see § 6).

$\delta _T / \delta _S = \textit{Le}^{1/2}$

leading to (2.6) may not be theoretically accurate under certain ambient conditions where the flow becomes bi-directional resulting in two distinct velocity scales within the BL, as discussed further in § 6. However, as shown in figure 2(c), the formulation in (2.6) is able to reproduce both numerical and experimental observations, even when the flow becomes bi-directional (because the two aforementioned velocity scales are of similar magnitude; see § 6).

At Antarctic ice shelves, the water temperature can range from approximately

![]() $2 ^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

to

$2 ^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

to

![]() $-2^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

(Jenkins et al. Reference Jenkins, Dutrieux, Jacobs, McPhail, Perrett, Webb and White2010; Boehme & Rosso Reference Boehme and Rosso2021). The values of

$-2^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

(Jenkins et al. Reference Jenkins, Dutrieux, Jacobs, McPhail, Perrett, Webb and White2010; Boehme & Rosso Reference Boehme and Rosso2021). The values of

![]() $\varLambda$

estimated for this condition are plotted in figure 2(a) using colour ranging from blue to red corresponding to

$\varLambda$

estimated for this condition are plotted in figure 2(a) using colour ranging from blue to red corresponding to

![]() $T_\infty =-2^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

to

$T_\infty =-2^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

to

![]() $4 ^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

. A zoomed-in view is given in figure 2(b). The values lie in the inner-dominated bi-directional or counter-flow region for this entire temperature range. Also, as

$4 ^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

. A zoomed-in view is given in figure 2(b). The values lie in the inner-dominated bi-directional or counter-flow region for this entire temperature range. Also, as

![]() $T_\infty$

decreases, the data deviate from the

$T_\infty$

decreases, the data deviate from the

![]() ${\varLambda } \textit{Le}^{1/2}$

line and become more inner-dominated. Note that figure 2(a) also shows two of our laboratory experimental data in symbols (see table 1, cases 5 and 6).

${\varLambda } \textit{Le}^{1/2}$

line and become more inner-dominated. Note that figure 2(a) also shows two of our laboratory experimental data in symbols (see table 1, cases 5 and 6).

We now proceed to present these laboratory experiments, and especially the modifications made to the MTV/MTT technique allowing us to measure temperature and velocity in the ice-melt BL.

3. Experimental set-up and adaptation of MTV/MTT technique

3.1. Experimental set-up

The experiments are performed in a small water tank with

![]() $9$

cm depth and a square base of

$9$

cm depth and a square base of

![]() $18$

cm in length and width (figure 3

a). One sidewall of the tank consists of a fused silica window to allow the ultraviolet (UV) laser beam needed for MTV to enter the tank. At the beginning of the experiments, an 85 mm high and 35 mm thick ice block spanning the width of the tank is placed at one end of the tank (figure 3

b), and magnets are used to secure the ice block to the endwall.

$18$

cm in length and width (figure 3

a). One sidewall of the tank consists of a fused silica window to allow the ultraviolet (UV) laser beam needed for MTV to enter the tank. At the beginning of the experiments, an 85 mm high and 35 mm thick ice block spanning the width of the tank is placed at one end of the tank (figure 3

b), and magnets are used to secure the ice block to the endwall.

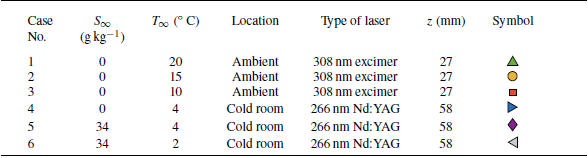

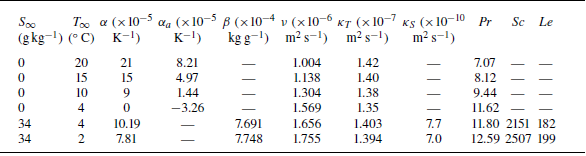

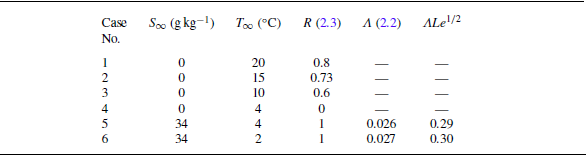

Table 1. Experimental cases. The far-field conditions (

![]() $T_\infty$

and

$T_\infty$

and

![]() $S_\infty$

) and environments for which these experiments are performed, as well as symbols used for each case.

$S_\infty$

) and environments for which these experiments are performed, as well as symbols used for each case.

Figure 3. (a) Schematic diagram of the experimental set-up and the arrangement of its components. (b) Schematic of the water tank and ice block.

As schematically shown in figure 3(a), the full experimental set-up mainly consists of the water tank, a pulsed UV laser and an intensified gated camera. A digital delay generator is used to synchronise the camera and the laser. The laser beam is guided to the fused silica window using an optics arrangement consisting of UV mirrors, and a pinhole arrangement is used to obtain a thin laser line. Images captured by the camera are logged using a host computer. Experiments with low-temperature conditions (below

![]() $4^\circ\, \textrm{C}$

) are performed in a temperature-controlled room (not shown here) where temperature can be maintained at a constant value ranging from

$4^\circ\, \textrm{C}$

) are performed in a temperature-controlled room (not shown here) where temperature can be maintained at a constant value ranging from

![]() $-15^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

to

$-15^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

to

![]() $25^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

.

$25^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

.

3.2. Flow measurement techniques

Measuring the velocity and temperature in the BL flow that forms next to the phase-change ice–water interface with high resolution is challenging for several reasons. Firstly, the thickness of this BL flow is small (of the order of a millimetre), and measurements have to be within (and adjacent to) this BL. Secondly, this BL flow is formed as a result of a free convection process, and, consequently, the velocities are small, about a few mm s−1. This enforces stringent requirements on the measurement system if we acknowledge that simultaneous velocity and temperature measurements are required.

Figure 4. (ai) An image pair captured by the camera with

![]() $11$

ms interframe delay. First image with 1 ms and second image with 2 ms camera exposure. (aii) Timing chart for phosphorescence intensity (

$11$

ms interframe delay. First image with 1 ms and second image with 2 ms camera exposure. (aii) Timing chart for phosphorescence intensity (

![]() $I$

) decay and image pair acquisition. Here,

$I$

) decay and image pair acquisition. Here,

![]() $t_0$

is the time between the laser pulse and first image acquisition,

$t_0$

is the time between the laser pulse and first image acquisition,

![]() $\Delta t$

is interframe delay,

$\Delta t$

is interframe delay,

![]() $\delta t_1$

is first image exposure and

$\delta t_1$

is first image exposure and

![]() $\delta t_2$

is second image exposure with

$\delta t_2$

is second image exposure with

![]() $t_0 \ll \Delta t$

. (b) Molecular tagging melt-rate measurements – tagged line intensities.

$t_0 \ll \Delta t$

. (b) Molecular tagging melt-rate measurements – tagged line intensities.

Considering the above requirements in this study, MTV and MTT are selected. The main advantage of these molecular tagging techniques is that they use molecules as tracers (e.g. Hu & Koochesfahani Reference Hu and Koochesfahani2006), enabling them to be used to obtain measurements close to the interface with high resolution. Furthermore, in this study, the standard MTV/MTT technique is modified to obtain temperature profiles in the BL flow for simultaneously measuring small velocities. Modifications to the standard MTV/MTT implementation adopted in this study are presented later in this section.

Briefly, MTV uses phosphorescent molecules excited by a UV laser as a Lagrangian tracer, and velocities are determined by two images separated by a specified delay time as acquired by a gated intensified camera. On the other hand, MTT leverages the fact that the decay rate of the phosphorescence is uniquely temperature-dependent. In this study for both MTV and MTT, a phosphorescent supramolecular complex is used as a molecular tracer. This complex consists of 1-bromonaphthalene (1-BrNp), a certain alcohol (cyclohexanol) and an aqueous solution of maltosyl-β-cyclodextrin (Mβ-CD). In this triplex, 1-BrNp acts as the luminophore while cyclohexanol and cyclodextrin insulate the luminophore from oxygen quenching and thus generating long-lived phosphorescence (Gendrich et al. Reference Gendrich, Koochesfahani and Nocera1997). For the present study,

![]() $1 \times 10^{-5}\,\rm M$

molar concentration of 1-BrNp is used while the molar concentrations of cyclohexanol and cyclodextrin are

$1 \times 10^{-5}\,\rm M$

molar concentration of 1-BrNp is used while the molar concentrations of cyclohexanol and cyclodextrin are

![]() $0.05 \,\rm M$

and

$0.05 \,\rm M$

and

![]() $3 \times 10^{-4}\,\rm M$

, respectively. A 308 nm excimer laser is used for excitation for the higher-temperature cases, and a 266 nm Nd:YAG laser for temperatures of

$3 \times 10^{-4}\,\rm M$

, respectively. A 308 nm excimer laser is used for excitation for the higher-temperature cases, and a 266 nm Nd:YAG laser for temperatures of

![]() $4^\circ$

C or below for the cold-room experiments. The choice is merely due to convenience; and although a 308 nm excimer laser was preferred owing to higher power, it is not portable and could not be located closer to the cold room. A Princeton Instruments PI-max4 1024i intensified gated camera that captures five frames per second (2.5 image pairs per second) with an image resolution of

$4^\circ$

C or below for the cold-room experiments. The choice is merely due to convenience; and although a 308 nm excimer laser was preferred owing to higher power, it is not portable and could not be located closer to the cold room. A Princeton Instruments PI-max4 1024i intensified gated camera that captures five frames per second (2.5 image pairs per second) with an image resolution of

![]() $1024\times 1024$

pixels is used for image acquisition.

$1024\times 1024$

pixels is used for image acquisition.

Figure 4(ai) shows a sample phosphorescent image pair used to acquire velocity and temperature. The laser enters from the right of the image and stops after impinging on the ice surface close to the left edge. The vertical pixel displacement of the maximum intensity pixels along the line is used to calculate the Lagrangian displacement of the tracer molecules. From the knowledge of displacement and time delay, the vertical velocity profile is obtained.

Once phosphorescent molecules are excited by the UV laser beam, phosphorescent intensity decays exponentially with time, as shown in figure 4(aii). This decay can be characterised by the time constant of the decay, i.e. phosphorescent lifetime

![]() $(\tau )$

, which depends on the temperature. In the standard MTT technique

$(\tau )$

, which depends on the temperature. In the standard MTT technique

![]() $\tau$

is calculated from phosphorescence signals collected from the two images taken a time

$\tau$

is calculated from phosphorescence signals collected from the two images taken a time

![]() $\Delta t$

apart:

$\Delta t$

apart:

![]() $\tau = \Delta t/(\ln (S_1/S_2))$

, where

$\tau = \Delta t/(\ln (S_1/S_2))$

, where

![]() $S_1$

and

$S_1$

and

![]() $S_2$

are image 1 and 2 intensities taken with the same exposure time

$S_2$

are image 1 and 2 intensities taken with the same exposure time

![]() $\delta t$

. In our case, where velocities are small (

$\delta t$

. In our case, where velocities are small (

![]() $\lessapprox 8$

mm s−1), we require larger

$\lessapprox 8$

mm s−1), we require larger

![]() $\Delta t$

for sufficient pixel displacement (at least 5 pixels) to obtain velocity in MTV. This implies that the second image intensity

$\Delta t$

for sufficient pixel displacement (at least 5 pixels) to obtain velocity in MTV. This implies that the second image intensity

![]() $S_2$

will be too small (within the noise) to be useful as the phosphorescence intensity decays exponentially. To overcome this, the

$S_2$

will be too small (within the noise) to be useful as the phosphorescence intensity decays exponentially. To overcome this, the

![]() $S_2$

camera exposure time (

$S_2$

camera exposure time (

![]() $\delta t_2$

) is increased compared with the

$\delta t_2$

) is increased compared with the

![]() $S_1$

exposure time (

$S_1$

exposure time (

![]() $\delta t_1$

) needed to obtain velocities. This, however, implies that we cannot use the standard MTT methodology, because

$\delta t_1$

) needed to obtain velocities. This, however, implies that we cannot use the standard MTT methodology, because

![]() $\delta t_1 \neq \delta t_2$

. Thus, the MTT equation is modified as follows. A phosphorescence signal

$\delta t_1 \neq \delta t_2$

. Thus, the MTT equation is modified as follows. A phosphorescence signal

![]() $S$

, collected by a camera for a shutter opening at time

$S$

, collected by a camera for a shutter opening at time

![]() $t_0$

(after the laser is fired), is exposed for a time

$t_0$

(after the laser is fired), is exposed for a time

![]() $\delta t$

given by

$\delta t$

given by

![]() $S=\int _{t_0}^{t_0+\delta t} I_0 {\rm e}^{-t/\tau } \,$

d

$S=\int _{t_0}^{t_0+\delta t} I_0 {\rm e}^{-t/\tau } \,$

d

![]() $t$

, where

$t$

, where

![]() $I_0$

is the initial light intensity at time

$I_0$

is the initial light intensity at time

![]() $t_0$

. This yields

$t_0$

. This yields

![]() $S= I_0 \tau (1-{\rm e}^{-\delta t/\tau }){\rm e}^{-t_0/\tau }$

. Using the two signals (

$S= I_0 \tau (1-{\rm e}^{-\delta t/\tau }){\rm e}^{-t_0/\tau }$

. Using the two signals (

![]() $S_1$

and

$S_1$

and

![]() $S_2$

) from the two images separated by the interframe delay,

$S_2$

) from the two images separated by the interframe delay,

![]() $\Delta t$

, the phosphorescent lifetime (

$\Delta t$

, the phosphorescent lifetime (

![]() $\tau$

) is then obtained using

$\tau$

) is then obtained using

See also figure 4(aii), where

![]() $t_0$

is the time between the laser pulse and first image acquisition,

$t_0$

is the time between the laser pulse and first image acquisition,

![]() $\Delta t$

is interframe delay,

$\Delta t$

is interframe delay,

![]() $\delta t_1$

is first image exposure and

$\delta t_1$

is first image exposure and

![]() $\delta t_2$

is second image exposure with

$\delta t_2$

is second image exposure with

![]() $t_0 \ll \Delta t$

. Note that when

$t_0 \ll \Delta t$

. Note that when

![]() $\delta t_2 = \delta t_1$

, (3.1) reverts to the standard MTT equation discussed above. Equation (3.1) is numerically solved to determine

$\delta t_2 = \delta t_1$

, (3.1) reverts to the standard MTT equation discussed above. Equation (3.1) is numerically solved to determine

![]() $\tau$

. These

$\tau$

. These

![]() $\tau$

values are then converted to the temperature profile using a calibration curve, where MTT images are obtained across a range of known temperatures. This calibration procedure is described in Appendix C.

$\tau$

values are then converted to the temperature profile using a calibration curve, where MTT images are obtained across a range of known temperatures. This calibration procedure is described in Appendix C.

3.3. Making bubble-free ice

The ice is created in an acrylic mould using slightly heated water (of approximately

![]() $70^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

to reduce bubble formation) and keeping it in a freezer typically overnight. Once the ice is frozen, small layers of sufficiently diluted phosphorescent chemical solution are poured on the ice face (where melting happens) and allowed to freeze again. This ensures that when the ice melts, the melt plume solution emits sufficiently strong MTV and MTT signals during the experiments. Since the MTV chemical molecules can lower the freezing point of ice, a freezing point depression calculation is carried out as detailed in Appendix B. This shows that the MTV chemicals do not cause freezing point depression of more than

$70^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

to reduce bubble formation) and keeping it in a freezer typically overnight. Once the ice is frozen, small layers of sufficiently diluted phosphorescent chemical solution are poured on the ice face (where melting happens) and allowed to freeze again. This ensures that when the ice melts, the melt plume solution emits sufficiently strong MTV and MTT signals during the experiments. Since the MTV chemical molecules can lower the freezing point of ice, a freezing point depression calculation is carried out as detailed in Appendix B. This shows that the MTV chemicals do not cause freezing point depression of more than

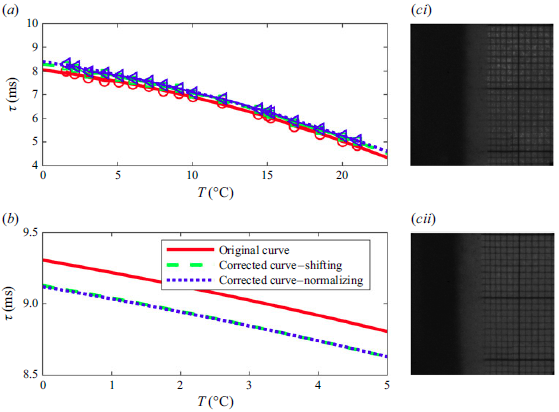

![]() $0.1^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

. Furthermore, freezing thin layers of water reduces the chances of entrapped air bubbles as the freezing predominantly takes place from the bottom and the thickness of the layers cannot accommodate large bubbles. However, introducing these layers with MTV chemicals makes the ice block slightly opaque as can be seen in figure 12(ci) and 12(cii). After removing the ice block from the mould, a slightly warm (approximately

$0.1^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

. Furthermore, freezing thin layers of water reduces the chances of entrapped air bubbles as the freezing predominantly takes place from the bottom and the thickness of the layers cannot accommodate large bubbles. However, introducing these layers with MTV chemicals makes the ice block slightly opaque as can be seen in figure 12(ci) and 12(cii). After removing the ice block from the mould, a slightly warm (approximately

![]() $50^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

) metal plate is used as a planer to obtain a smooth ice face by melting off irregularities.

$50^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

) metal plate is used as a planer to obtain a smooth ice face by melting off irregularities.

3.4. Flow measurement procedure

Experiments are conducted under six different ambient water temperatures

![]() $T_\infty$

and salinity

$T_\infty$

and salinity

![]() $S_\infty$

conditions as listed in table 1. This table also contains information about the lasers used and the environments in which experiments were performed, as well as the symbols for the plots in later sections. The temperature and salinity of the water everywhere in the tank are maintained at these specific values before placing the ice block inside the water. A pinhole of diameter

$S_\infty$

conditions as listed in table 1. This table also contains information about the lasers used and the environments in which experiments were performed, as well as the symbols for the plots in later sections. The temperature and salinity of the water everywhere in the tank are maintained at these specific values before placing the ice block inside the water. A pinhole of diameter

![]() $0.3$

mm is used to obtain a thin laser line (see figure 3

a). The vertical location of the tagged line from the bottom of the tank is also listed in table 1 for each case (see figure 4

ai). These locations are chosen such that the measurement location is nominally two-thirds of the total ice–water interface height (85 mm) in the flow direction. Note that for

$0.3$

mm is used to obtain a thin laser line (see figure 3

a). The vertical location of the tagged line from the bottom of the tank is also listed in table 1 for each case (see figure 4

ai). These locations are chosen such that the measurement location is nominally two-thirds of the total ice–water interface height (85 mm) in the flow direction. Note that for

![]() $S_\infty =0$

and

$S_\infty =0$

and

![]() $T_\infty \gt 4^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

, the flow is downwards. For all other cases the flow is more complicated but there is an upward flow close to the melting ice surface.

$T_\infty \gt 4^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

, the flow is downwards. For all other cases the flow is more complicated but there is an upward flow close to the melting ice surface.

Experimental cases 1, 2 and 3 are performed under relatively higher temperature conditions (see table 1), and the data are acquired after 60 s from the time the ice block was placed in the water tank. This initial time allows for any disturbances caused during the placement of the ice block in the water to settle, and ensures that the BL velocity and ice ablation velocity reach a steady state. The DNS findings of Gayen et al. (Reference Gayen, Griffiths and Kerr2016) indicate that the ice ablation velocity achieves a statistically steady state after

![]() ${\approx} 20$

s. Furthermore, even at the lowest BL velocity (of

${\approx} 20$

s. Furthermore, even at the lowest BL velocity (of

![]() $\approx$

0.2 cm s−1), the BL flow can traverse more than the entire height of the ice block within the initial 60 s period, demonstrating that this time is sufficient for the flow to stabilise. It was observed that the ice block temperature was approximately

$\approx$

0.2 cm s−1), the BL flow can traverse more than the entire height of the ice block within the initial 60 s period, demonstrating that this time is sufficient for the flow to stabilise. It was observed that the ice block temperature was approximately

![]() $-8^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

before being placed in water, and it dropped further to

$-8^{\,\circ} \text{C}$

before being placed in water, and it dropped further to

![]() $-6^\circ \, \text{C}$

before data acquisition began. The sampling frequency of data acquisition is 2.5 image pairs per second (5 f.p.s.). This means that after the initial period, velocity and temperature profiles are acquired every 0.4 s for about 3 minutes. During the experiment, ambient water temperatures are recorded using two thermistors placed 15 and 100 mm from the interface to verify that the ambient water temperature was approximately constant at the specified value everywhere in the tank. In this study, the reported velocity and temperature profiles were obtained between 60 and 120 s after placing the ice block in water.

$-6^\circ \, \text{C}$

before data acquisition began. The sampling frequency of data acquisition is 2.5 image pairs per second (5 f.p.s.). This means that after the initial period, velocity and temperature profiles are acquired every 0.4 s for about 3 minutes. During the experiment, ambient water temperatures are recorded using two thermistors placed 15 and 100 mm from the interface to verify that the ambient water temperature was approximately constant at the specified value everywhere in the tank. In this study, the reported velocity and temperature profiles were obtained between 60 and 120 s after placing the ice block in water.

The procedure just described is followed for the low-temperature cases (cases 4, 5 and 6) but the data acquisition interval is 120–240 s. Note that in the low-temperature cases the establishment of a steady BL flow takes longer, and the temperature in the tank remains approximately constant at specified temperatures for a longer period. We note that, since most of these experiments are conducted below the dew point of air, condensation occurs whenever the water tank and optics inside the cold room are exposed to the outside air. This significantly disrupts the experiments, as the presence of condensation on the cold-room window, water tank or any optics leads to an unacceptable degradation in the quality of measurements. This presented a major challenge that is mitigated by scheduling the experiments on days with very low dew points and minimising the number of times the cold-room door is opened.

Before and after conducting the ice block experiments, in situ pre-calibration and post-calibration image pairs are obtained for the specified temperature values. This is done because the calibration curve may have shifted slightly from the original calibration due to the ageing of the solution. These post- and pre-calibration points enable us to obtain temperature measurements from a normalised calibration curve that is immune to ageing effects as described in Hu & Koochesfahani (Reference Hu and Koochesfahani2006). See Appendix C for further details of the MTT calibration procedure.

Once obtained, the phosphorescent images are processed using Matlab. The image pre-processing procedure is outlined in Appendix D. In the phosphorescent images (as shown in figure 4 ai), the MTV/MTT tagged line is parallel to horizontal lines of image pixels. The pixel with maximum intensity in each vertical pixel line is considered for obtaining the vertical location of undeformed and deformed tagged lines. In order to obtain the location of the line with subpixel accuracy, a second-order polynomial is fitted in the neighbourhood of the maximum intensity pixel, and the location of the peak of that polynomial is taken as the vertical location of the tagged line in the image. Once the location of the tagged line is found in both images of the image pair, the pixel displacement of the tagged line is obtained. This is then converted to actual displacement using the pixel-to-length ratio obtained during the experiments using a ruler placed in the water tank. Since the timing parameters of imaging are known, flow velocity is calculated from displacement.

In MTT, the pixel with maximum intensity in each vertical pixel line is considered in both images of the image pair and the intensity ratio is obtained along the tagged line. Once the intensity ratio is obtained, (3.1) is used to obtain phosphorescent lifetime (

![]() $\tau$

), and then a calibration curve (as explained in Appendix C) is used to obtain temperature profiles.

$\tau$

), and then a calibration curve (as explained in Appendix C) is used to obtain temperature profiles.

3.5. Melt-rate measurements

Separate experiments are carried out to measure the ice melting rate for high-ambient-water-temperature cases (cases 1, 2 and 3) that have significantly higher melt rates compared with low-temperature cases. This involved the same set-up used for the velocity and temperature measurements, but no laser is used. Rather, an intense white light source is used to illuminate the melting ice face. A grid paper is placed on the back wall, and the camera image depth of field is increased to obtain images where the ice face and the grid paper are visible. Images of melting ice are obtained at a frame rate of 5 Hz for about 5 min. The receding position of the ice–water interface is therefore obtained as a function of time (using image analysis), and the ice melt rate (reduction of the ice-face thickness per unit time) is estimated. In accordance with the MTV/MTT experiments, the melt-rate data are also obtained within the

![]() $60{-}120$

s window to ensure steady-state melting. The melt-rate measurements for the low-temperature cases could not, however, be obtained with sufficient accuracy using this method because the melt rates are very small, and interface movement was difficult to detect.

$60{-}120$

s window to ensure steady-state melting. The melt-rate measurements for the low-temperature cases could not, however, be obtained with sufficient accuracy using this method because the melt rates are very small, and interface movement was difficult to detect.

To address this challenge, a different method that enables melt-rate measurements simultaneously with velocity and temperature measurements is developed. Here, the first image of each phosphorescent image pair is used, and the location of the tagged line is obtained. The ice–water interface is detected from the large gradient of phosphorescent intensity observed when the tagged line passes from water to ice, as shown in figure 4(ai). Once the interface location is known in each image, the ice melt rate is calculated with the timing information, i.e. slope of the black line in figure 4(b). Further details of melt-rate measurements using both methods are presented in Appendix E.

4. Direct numerical simulation set-up

The DNS used herein solves the three-dimensional and non-hydrostatic Navier–Stokes equations to simulate the ice melting and BL formation process in the water tank (Gayen et al. Reference Gayen, Griffiths and Kerr2016). The DNS data are compared with the experimental results and employed to understand the underlying physics. The number of grid points in the DNS was

![]() $257\times 32\times 1153$

(

$257\times 32\times 1153$

(

![]() ${\approx}9.48\times 10^{6}$

) in the wall-normal, spanwise and vertical directions, respectively. The grid spacing is non-uniform in

${\approx}9.48\times 10^{6}$