Can culture help to explain prejudice? While negative out-group attitudes are often attributed to material concerns—such as job loss, relative income losses, competition for housing, or personal safety (e.g., Inglehart and Norris Reference Inglehart and Norris2017; Olzak Reference Olzak1992; Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001)—a substantial body of literature suggests that these attitudes stem from broader societal (i.e., sociotropic) concerns and cultural threats rather than individual experiences (e.g., Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010; Sniderman, Hagendoorn, and Prior Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Soroka, Iyengar, Aalberg, Duch, Fraile and Hahn2017). Yet whereas material drivers are well understood and measurable, identifying the cultural roots of negative out-group attitudes has remained largely elusive. Here we propose a new concept—cultural scripts—that allows us to precisely operationalize and measure how culture influences out-group attitudes. Our framework provides a way to anticipate when particular cultural stereotypes will surface and to identify the groups most receptive to them. We test our theory by examining a particularly revealing case: the resurgence of antisemitic attitudes in Germany during the COVID-19 pandemic, which we analyze through three interrelated studies.

We define cultural scripts as interconnected networks of meanings that exist in people’s minds and structure how they interpret the social world. Cultural scripts guide how individuals respond to particular cues (such as the pandemic), and which stereotypes and prejudices get activated. In the context of prejudice, cultural scripts link particular group identities with negative ideas or images, even when those ideas are not logically related. For example, in the Christian tradition, disease and the betrayal of Jesus are linked with Jews. When one of these ideas is triggered (in our case, exposure to the pandemic activating the concept of disease), other negative associations, such as the betrayal and Crucifixion of Jesus, can automatically come to mind and become intertwined with the idea of Judaism, thereby evoking the negative emotions and hardened attitudes associated with manifest antisemitic prejudice. While we develop our conceptual framework in a general way so that it may be used to study a wide range of cultural expressions, in this paper we focus on two specific cultural scripts: that of “traditional” antisemitism, rooted in Christian thought and myth, and that of “modern” antisemitism, based on race ideology (Brustein Reference Brustein2003; Perry and Schweitzer Reference Perry and Schweitzer2002).

Our conceptualization of cultural scripts means that we can operationalize them as networks of interconnected concepts, and measure them using natural language processing. In our first study, we therefore isolate and visualize the two scripts from a hand-collected corpus (n = 172) of antisemitic texts. Both scripts emerge as distinguishable networks of terms, distinct both from unrelated terms and from one another. In our second study, we then proceed to demonstrate that the observed increase in antisemitic attitudes during the COVID-19 pandemic originated in traditional, not modern, antisemitism. Using survey data (n = 17,800) collected during the first year of the pandemic, we show that antisemitism increased exclusively in Christian-heritage regions and among self-identified Christians, including both Catholics and Protestants, constituting approximately half of our sample. Effect sizes are substantial, with both affective and cognitive antisemitism increasing by around seven percentage points among Christian believers who contracted COVID-19. In contrast, the pandemic had no effect on antisemitism among non-Christians or among supporters of the radical Right. Similar patterns are observed when measuring exposure in terms of COVID-19 incidence rates at the county level.

To demonstrate that the crisis-induced rise in antisemitic attitudes stemmed from the pandemic activating anti-Jewish beliefs rooted in Christian or biblical thought, we draw on a series of additional tests and analyses. Using our survey, we show that the belief that “the Jews” were responsible for the death of Jesus Christ—a central element in the cultural script of traditional antisemitism—nearly doubled among individuals exposed to the pandemic. Using an instrumental variable strategy, we provide evidence that this belief shift contributed to increased antisemitic prejudice. We then rule out competing explanations such as place-based legacies or symbolic threat.

In addition, in our third study, we collected supplementary survey data (n = 2,000) with three measures explicitly designed to trace the cultural script of traditional antisemitism in respondents’ minds: a knowledge test, a concept association task, and two priming experiments. We find that Christian believers are more knowledgeable about tropes and narratives related to traditional antisemitism, more likely to associate Judaism with elements of that script, and more concerned about disease when primed with the betrayal of Jesus—findings consistent with our theory identifying cultural scripts as the structure underlying antisemitic stereotypes.

Alongside examining a particularly revealing case—the reactivation of antisemitic sentiment during the COVID-19 pandemic among Christian believers in Germany (cf. Allington, Hirsh, and Katz [Reference Allington, Hirsh and Katz2023] and Sundberg, Mitchell, and Levinson [Reference Sundberg, Mitchell and Levinson2023] for similar findings from other countries)—our paper makes two broader contributions, one theoretical and one methodological. We provide theoretical advancement by defining and operationalizing the concept of cultural script as a contribution to the literature on negative out-group stereotypes (e.g., Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010; Paluck and Green Reference Paluck and Green2009; Quillian Reference Quillian1995; Scacco and Warren Reference Scacco and Warren2018; Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Soroka, Iyengar, Aalberg, Duch, Fraile and Hahn2017). We situate our concept in the context of the literature on historical legacies, where we suggest that cultural scripts can provide an alternative channel for how political attitudes and behaviors can be passed on. Unlike place-based or socialization-based legacies, which are prominently discussed in this literature (e.g., Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018; Charnysh Reference Charnysh2015; Voigtländer and Voth Reference Voigtländer and Voth2012), our proposed cultural channel operates through the activation of latent cognitive scripts. Since such scripts likely can be triggered intentionally for political effect, our concept may also be useful to scholars of political communication, especially those studying racial priming and populist rhetoric (e.g., Busby, Gubler, and Hawkins Reference Busby, Gubler and Hawkins2019; Chong and Druckman Reference Chong and Druckman2007; Mendelberg Reference Mendelberg2008; Valentino, Neuner, and Vandenbroek Reference Valentino, Neuner and Vandenbroek2018). In terms of methods, we show that cultural scripts can be measured in a nonarbitrary manner using a combination of natural language processing and individual-level experimental and nonexperimental measures. Taken together, the theory and methods we propose provide a novel tool for studying the profound influence that culture can have on exclusionary out-group attitudes.

Theory: Material and Cultural Sources of Prejudice

As noted by Allport (Reference Allport1954), the sources of prejudice are manifold, and a single explanation is unlikely to account for the whole phenomenon. Here, we review key approaches to position our argument within the existing literature. We contend that none of the existing explanations provide a fully convincing account for our case. Instead, we argue that the rise in antisemitic sentiment during the COVID-19 pandemic can be shown to be plausibly rooted in culture. In making this argument, we aim to offer a complementary perspective on the origins of prejudice that may also help to address existing theoretical limitations.

Material Threat and Competition

A first strand of the literature explains negative out-group attitudes—particularly toward migrants—with “material” accounts that link prejudice to resource conflicts or immigration. One mechanism is labor market competition, which may foster resentment toward outsiders (Scheve and Slaughter Reference Scheve and Slaughter2001). Conversely, economic complementarity can generate more positive views (Jha Reference Jha2014). However, the evidence supporting this theory is mixed (Ersanilli and Präg Reference Ersanilli and Präg2021; Hainmueller and Hiscox Reference Hainmueller and Hiscox2010; Sniderman, Hagendoorn, and Prior Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004). By contrast, studies consistently link competition over scarce public goods such as welfare or housing to increased prejudice, especially in electoral contexts where politicians mobilize resource fears (Dancygier Reference Dancygier2010; Olzak Reference Olzak1992), when hostile discourse accompanies out-group arrivals (Koopmans and Olzak Reference Koopmans and Olzak2004), or when one group’s relative status rises (Abascal Reference Abascal2015; Bobo and Hutchings Reference Bobo and Hutchings1996; Hopkins Reference Hopkins2010).

Feelings of threat serve as another prominent explanation for negative stereotypes (Blalock Reference Blalock1967; LeVine and Campbell Reference LeVine and Campbell1972; Quillian Reference Quillian1995). Scholars within this tradition differentiate between realistic threat, which involves the expectation of physical harm resulting from interactions with the out-group, and symbolic threat, which pertains to threats against a community’s values, identity, or worldview (Canetti-Nisim, Ariely, and Halperin Reference Canetti-Nisim, Ariely and Halperin2008; Sniderman, Hagendoorn, and Prior Reference Sniderman, Hagendoorn and Prior2004). Similar to theories connecting negative out-group attitudes to competition, realistic threat theory offers a material explanation that hinges on the actual presence of an out-group. It posits that larger numbers of group members increase competition and threat perceptions, thereby fueling rejection of the out-group. However, as discussed below, none of these material explanations are likely to apply in our case, given the absence of a substantial Jewish community in Germany.

Symbolic Threat and Identity

A second strand of literature relates prejudice to “symbolic,” or immaterial, explanations that apply even when no out-group is physically present. One prominent theory invokes “racial animus,” which people experience when they perceive a threat to their value systems or worldviews from outsiders. Experimental studies across Europe, the United States, and Asia have shown heightened criticism of Muslim immigration, even when controlling for socioeconomic and demographic factors (e.g., Valentino et al. Reference Valentino, Soroka, Iyengar, Aalberg, Duch, Fraile and Hahn2017). Similarly, in the US, Latino immigration is met with stronger rejection compared with European immigration (Abrajano and Hajnal Reference Abrajano and Hajnal2015; Brader, Valentino, and Suhay Reference Brader, Valentino and Suhay2008). However, these theories yet again typically examine situations involving (simulated) inflows of outsiders, implying a “material” basis for the perceived threat. Additionally, this scholarship often overlooks the source of the animus. Instead, the typical analytic strategy consists of holding material threats constant, and attributing remaining negative attitudes to cultural factors.

A related perspective links negative out-group attitudes to identities, often grounded in social identity theory (Sumner Reference Sumner1906; Tajfel and Turner Reference Tajfel, Turner, Austin and Worchel1979). Social identity theory stipulates that out-group degradation derives from individuals’ tendency to elevate their own group above others to gain status from this superior position. It implies that in-group bias almost automatically leads to out-group degradation. While empirical support for individuals favoring their in-group is substantial, evidence of quasi-automatic concurrent out-group hostility is limited (Brewer Reference Brewer1999; Halevy, Weisel, and Bornstein Reference Halevy, Weisel and Bornstein2012).

However, in certain cases, “ethnocentrism,” defined as an exaggerated sense of in-group identity, has been found to contribute to negative out-group attitudes (Kam and Kinder Reference Kam and Kinder2007). The same authors demonstrate that negative external events, such as terrorist attacks, can amplify ethnocentrism and hence the rejection of out-groups. The challenge with this argument is that defining identity is notoriously difficult (cf. Laitin Reference Laitin1986). We suggest an alternative perspective where crises activate cultural scripts, which are more specific and easier to define, instead of solely emphasizing the exaggeration of in-group identity.

Another relevant literature concerning racism in the US distinguishes between “old racism,” rooted in slave–slaveowner relations, and “new racism” or “symbolic racism.” This body of work posits that racism in the US has evolved from overt resentment and denigration of Black individuals into the belief that they are demanding and undeserving (Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981). The term “belief system” aligns closely with our concept of cultural script. However, critics have noted the strong correlation of these beliefs with political ideology, leading to ongoing debates about the boundary between “new racism” and traditional political ideology (cf. Enders Reference Enders2021; Tarman and Sears Reference Tarman and Sears2005). As will be shown, our approach allows us to more clearly isolate the cultural dimension of these processes, which, if applied to Black–white relations in the US, may help to inform the debate on new racism versus political ideology.

The Behavioral Immune System Theory

A theoretical perspective that has gained traction in political science is behavioral immune system (BIS) theory, which directly links negative out-group attitudes to infectious diseases (Aarøe, Petersen, and Arceneaux Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2017; Schaller and Park Reference Schaller and Park2011). The theory posits that humans have evolved a behavioral counterpart to the physiological immune system to reduce infection risks. This subconscious system triggers emotions of disgust when encountering potential disease threats, steering individuals away from them. Consequently, the BIS has been theorized to influence aversion toward unfamiliar-looking others, including immigrants, as unfamiliarity is associated with potential disease risks. Studies indicate that individuals high in BIS exhibit greater opposition to immigration, favor segregating immigrants, and associate foreigners with diseases (Aarøe, Petersen, and Arceneaux Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2017; Ferree et al. Reference Ferree, Dulani, Harris, Kao, Lust, Jansson and Metheney2023). However, at least two aspects of BIS theory make it incompatible with our case. First, BIS theory predicts a strong response to phenotypically unfamiliar individuals, which does not easily apply to Jews, who tend to be phenotypically indistinguishable from surrounding populations. Most importantly, the BIS reaction to outsiders would elicit a response to all unfamiliar individuals. However, we show that the effect we are describing is unique to antipathy toward Jews. Therefore, despite appearing relevant, BIS theory is unlikely to provide informative insights for our case.

Place-Based Legacies

Social scientists studying the origins of racism and antisemitism have uncovered significant spatial variations in the intensity of these attitudes. One early example of this literature relates the occurrence of pogroms against Jews in the Middle Ages to the increased hatred and violence toward Jews during the Nazi era (Voigtländer and Voth Reference Voigtländer and Voth2012). More recent work shows that during Germany’s Weimar Republic, border regions exhibited much higher levels of antisemitism, as evidenced by the presence of Jewish “bogeymen” (Kinderschreck) in children’s stories (Braun Reference Braun2022). Similarly, regions in Poland that experienced competition between Jews and non-Jews during the interwar period displayed higher levels of antisemitism, which could subsequently be activated by political entrepreneurs even after these sentiments lost their factual basis (Charnysh Reference Charnysh2015). Relatedly, regions in the US South where slavery was prevalent exhibit higher levels of racist attitudes (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016; Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018).

What these scholarly approaches have in common is that they establish connections between past events, which are “concluded” by typical understandings of the word, and contemporary attitudes. This raises the question of how attitudes that emerged under past circumstances are carried forward to the present. Most authors conclude that intergenerational socialization plays a vital role in this process, and some provide convincing evidence in this regard (Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016; Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018). Our paper contributes to this literature by showing in more depth what is transmitted between generations. We propose that racist and antisemitic attitudes are rooted in cultural scripts, wherein particular stereotypes are embedded within a broader network of interconnected meanings. Unlike place-based explanations, these cultural scripts are not tied to a specific location but rather to a particular subculture—in our case, Christian believers.

Our Argument: Cultural Scripts as a Source of Prejudice

Why should a pandemic increase antisemitism, and among whom in particular? Our claim is that the COVID-19 pandemic activated the cultural script of traditional antisemitism commonly shared among Christian believers.

Cultural Scripts

Borrowing from classic writings in anthropology, we define culture as “the fabric of meaning in terms of which human beings interpret their experience and guide their action” (Geertz Reference Geertz1973, 145). Culture links to political behavior by defining “the local possibilities of action” (Sewell Reference Sewell2005, 165), the set of acceptable courses of action to take in a given situation.Footnote 1 More recent definitions of culture typically pair the understanding of culture as a “system of significations” (i.e., the fabric of meanings) with an emphasis on the actions that maintain and challenge cultural forms (i.e., “practice”) and the actors that drive changes (Ricart-Huguet and Paluck Reference Ricart-Huguet and Paluck2023; Wedeen Reference Wedeen2002). We instead treat these two aspects—the system of signification and the practices that modify them—as analytically distinct, focusing on the former. Put differently, we seek to analyze “systems of signification,” which we term cultural scripts, in isolation. We deem this approach justified because we see the need to define our concept of cultural script in a way that makes it possible to test and falsify it empirically (cf. Laitin in Wedeen Reference Wedeen2002, 719). We reference political culture literature that highlights how meaning systems can change and vary across different groups or times (e.g., Paluck and Green Reference Paluck and Green2009). Important for our theory and reflecting recent understandings of cultures, several cultural scripts with overlapping meanings can coexist at any place and time. Our concept of “cultural script” aligns with what cultural sociologists call “cultural schemas” (DiMaggio Reference DiMaggio1997; Hunzaker and Valentino Reference Hunzaker and Valentino2019; Vaisey Reference Vaisey2009), defined as “networks of implicit associations accrued through experience” (Boutyline and Soter Reference Boutyline and Soter2021, 730). We favor “cultural script” because it emphasizes cultural content over experience and practice.

Borrowing further from sociological thought on cultural schemas, we conceive of cultural scripts as cognitive structures that are acquired by social learning (Boutyline and Soter Reference Boutyline and Soter2021; cf. Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981). The scripts are formed in interactions with the social and symbolic world: through conversations, explicit teaching, reading, watching movies, and so forth. Once established, scripts function as “automatic pattern completion” mechanisms, whereby new pieces of information are placed within the networks of meanings, filling gaps in understanding (Boutyline and Soter Reference Boutyline and Soter2021; DiMaggio Reference DiMaggio1997). Cultural scripts fall under “type 1”—“fast” cognition in dual-process theories of cognition—in the sense that they are quickly, automatically, and unconsciously invoked (Kahneman Reference Kahneman2011; Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge and Taber2013). This does not mean that they cannot be brought into consciousness and evaluated if an effort is made, but it does mean that they cannot be unlearned or easily suppressed as conscious, intentional, “type 2” processes can (Evans and Stanovich Reference Evans and Keith2013; Vaisey Reference Vaisey2009). As cognitive “knowledge structures” (DiMaggio Reference DiMaggio1997), cultural scripts will be activated when individuals encounter elements of the script in their lives. These triggers can be relatively benign, such as the experimental primes used below, or more sustained and intense, such as experiencing a nearby outbreak or falling ill. These real-world triggers serve as mental stimuli activating the corresponding mental representation. For example, falling ill with an infectious disease will activate the mental representation of “disease” in people’s minds. The activation of one element of a cultural script then cascades to other elements of that script—that is, it makes the entire network of interconnected meanings salient (Boutyline and Soter Reference Boutyline and Soter2021; DiMaggio Reference DiMaggio1997).

Once activated, cultural scripts can influence action through the above-outlined quasi-automatic pattern completion mechanism or by eliciting emotional responses. Depending on the stimulus, these may be positive (e.g., enthusiasm) or negative (e.g., fear or anger). For antisemitic scripts, whose constituent elements (disease, the death of Jesus, conspiracy) are negatively connoted, activation is likely to provoke negative emotions such as fear, anger, or disgust. Following similar arguments in the political psychology literature, we again stipulate that these emotional responses arise in a quasi-automatic, unconscious manner (cf. Aarøe, Petersen, and Arceneaux Reference Aarøe, Petersen and Arceneaux2017; Brader Reference Brader2006; Lodge and Taber Reference Lodge and Taber2013; Marcus, Neuman, and MacKuen Reference Marcus, Neuman and MacKuen2000; Schnakenberg and Wayne Reference Schnakenberg and Wayne2024).

Cultural scripts thus relate to prejudice by informing the belief networks and triggering the emotions that constitute the central elements of prejudice. The pandemic cued thoughts on diseases and their origins, along with triggering feelings of anxiety (Morisi et al. Reference Morisi, Cloléry, King and Schaub2021). By so doing, we argue, the pandemic activated the wider cultural script connecting diseases, suffering, and Judaism. Among individuals conversant in Christian (popular) thought, diseases are connected to ideas about plague, divine punishment, sin, betrayal, suffering, and ultimately Christ’s Crucifixion—for which “the Jews” are often blamed. However, we assert that cultural scripts should not be conceived of as directed chains, but rather as networks of closely interlinked concepts that do not need to be inherently semantically related. Thus, in people’s minds, thoughts of plague can quasi-simultaneously trigger images of punishment, Christ’s suffering, and the “guilty Jew,” as these images are intertwined within the cultural script of traditional antisemitism—even though these share no inherent logical link. Instead, the connection between these concepts is cultural, in the sense that they belong to the same cultural script of traditional antisemitism.

Schematic Overview

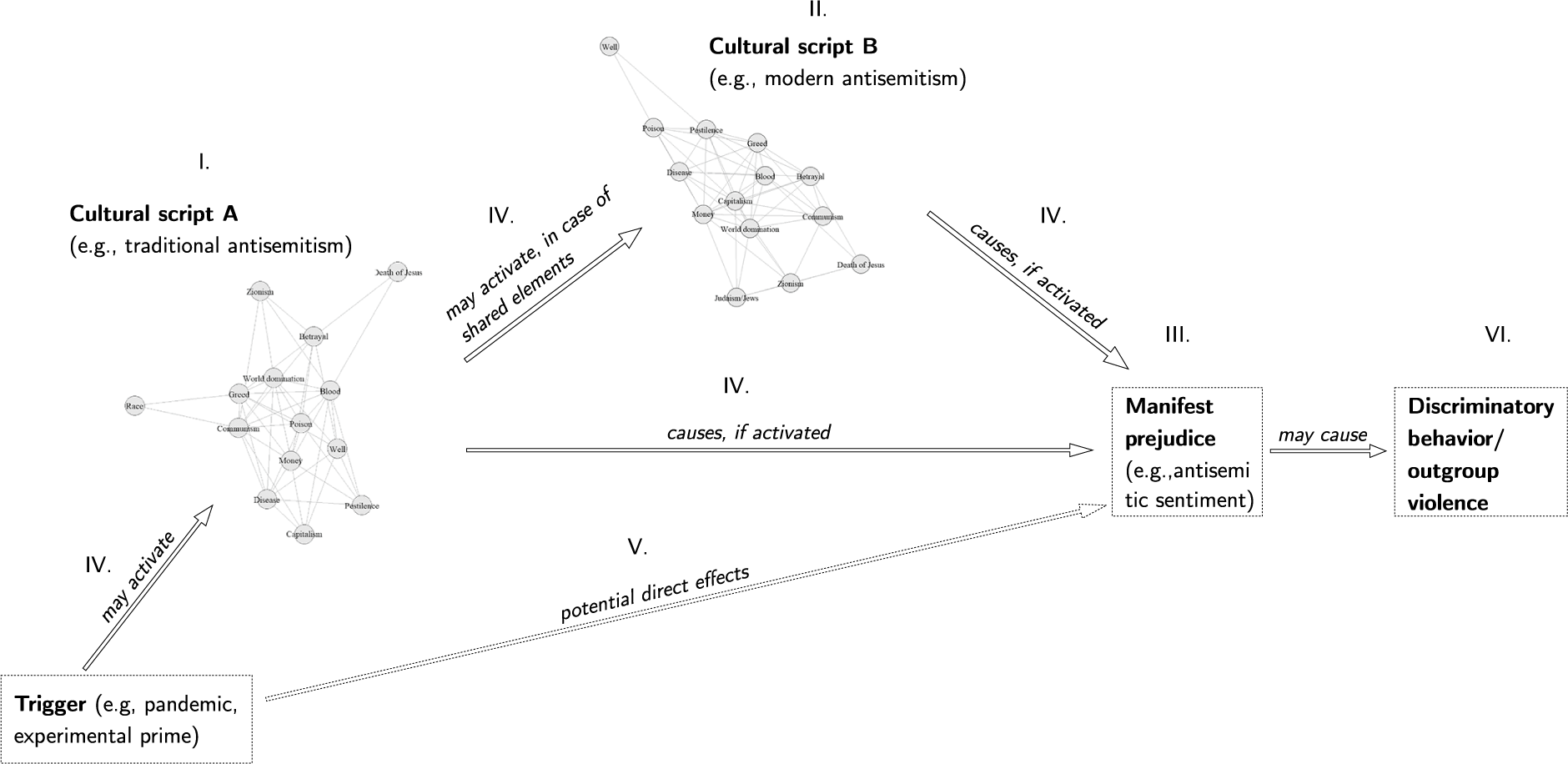

Our argument and theory consists of several separate elements that are connected in fairly complex ways. Figure 1 therefore seeks to illustrate the logic in a graphic way. Central to our argument are cultural scripts, defined above as networks of interrelated concepts that exist in people’s minds (elements I and II), and how these can lead to manifest prejudice, defined as hardened negative attitudes toward individuals based solely on their perceived membership of a particular social group (cf. Allport Reference Allport1954; Kinder and Sears Reference Kinder and Sears1981) (element III). We show two cultural scripts in the figure to underline the fact that several distinct scripts can coexist in a person’s mind at the same time—for example, the cultural scripts of modern and traditional antisemitism tested here. The arrows either signify activation or causation. As per our theory, cultural scripts can be activated by external triggers. These can be, as in our study, exogenous events such as the pandemic or an experimentally induced prime, but may also include elite rhetoric. As for these triggers, their effect can run through the cultural scripts (links IV), or they can have parallel direct effects (link V). The latter is particularly plausible for broad-scope triggers such as the pandemic, which not only activated cultural scripts, but also induced fear of unemployment, for example, which plausibly had a separate effect on prejudice.

Figure 1 Schematic Overview of Relationships between Cultural Scripts, Triggers, Prejudice, and Discriminatory Behavior

The arrow between cultural script A and cultural script B suggests that the activation of one script can trigger the activation of another script in case they share common elements. For instance, we argue that the activation of the script of traditional antisemitism in the minds of Christian believers also activated the script of modern antisemitism, because both scripts share the concept of “Judaism.” At the end of the causal chain stands discriminatory behavior, including out-group violence (element VI), which can be caused by prejudice. While this final link is arguably the ultimate reason why we care about prejudice, this relationship is already well established in the extant literature (e.g., Ivarsflaten Reference Ivarsflaten2005; Jardina and Piston Reference Jardina and Piston2023; Kinder and Sanders Reference Kinder and Sanders1996; Miller-Idriss Reference Miller-Idriss2020) and is beyond the scope of our paper. In the following, we instead first provide some background on the cultural scripts of traditional and modern antisemitism and then move on to demonstrate the above-discussed causal chain empirically.

Background: Traditional and Modern Roots of European Antisemitism

Traditional Antisemitism

There can be no doubt that antisemitism in Europe has deep cultural roots. Various narratives have long tied Judaism to ideas about disease, divine punishment, betrayal, and, ultimately, Christ’s Passion and Crucifixion. Together, we argue, these form the cultural script of traditional antisemitism, which has deeply embedded itself in the minds of individuals, especially Christian believers. Our perspective mirrors Nirenberg’s (Reference Nirenberg2013) view of anti-Judaism as a recurring cultural and conceptual resource in Western thought. He demonstrates how anti-Jewish ideas have historically served as tools for interpreting crises, contradictions, and moral disorder, highlighting their enduring role in shaping cultural meaning. This resonates with our argument that the cultural script of traditional antisemitism, as a set of meanings rooted in associations formed through Christian history and theology, is not only persistent, but also easily reactivated by external triggers.

While antisemitism is not exclusive to Christianity, it has found particularly fertile ground within this religious tradition. The portrayal of Jews in the New Testament, patristic writings, and later church teachings seems to have ignited widespread antisemitism and persecution of Jews in the Christian world (Middleton Reference Middleton1973, 34). Historical accounts link long-standing hostility and suspicion toward Jews to first-century gospel narratives that blame them for the death of Jesus (Carroll Reference Carroll2001). According to Stacey (Reference Stacey1998, 11), the idea “that Jews constitute a threat to the body of Christ is the oldest, and arguably the most unchanging, of all Christian perceptions of Jews and Judaism.” In the Gospels, particularly in the Passion story, Jews are labeled as “the Christ killers” and accused of “deicide” (Perry and Schweitzer Reference Perry and Schweitzer2002). Correspondingly, for centuries, the Good Friday service used language that suggested an antisemitic tone, calling Jews perfidis, meaning “treacherous” or “untrustworthy” (Pierce Reference Pierce2021). Changes to these terms by the Catholic Church occurred only in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Antisemitism also played a key role in the Paupers’ Crusade that resulted in the destruction of many Jewish communities in the episcopal cities on the Rhine in the early eleventh century (N. Cohn Reference Cohn1970). This set the precedent for later crusades marked by anti-Jewish agitation and violence. Blood libels—false allegations that Jews used the blood of Christian children in rituals—and other spurious claims that they had engaged in the desecration of hosts were cited as reasons for expelling Jews from medieval European cities (Menache Reference Menache1985; Müller Reference Müller and Cluse2004).

The mobilizing power of traditional antisemitic tropes showed itself at its most extreme during the Black Death (1346–53), which led to severe antisemitic violence that reshaped the Jewish population and its settlement patterns for centuries (Breuer Reference Breuer, Almog and Reisner1988; S. Cohn Reference Cohn2007; Jedwab, Johnson, and Koyama Reference Jedwab, Johnson and Koyama2019). As the plague spread to Western Europe, unfounded rumors blamed Jews for the outbreak, claiming they were poisoning wells to destroy Christianity, which greatly fueled the persecutions (Brustein Reference Brustein2003; Müller Reference Müller and Cluse2004; Prager and Telushkin Reference Prager and Telushkin2003). As we will show below, Christian believers today are still much more likely to associate the ideas of disease, blood, and wells with Judaism (see also Sundberg, Mitchell, and Levinson Reference Sundberg, Mitchell and Levinson2023).

The Protestant Reformation did not lead to a break with Christian antisemitism either (Brustein Reference Brustein2003). Conversely, Martin Luther, initially opposing the Catholic Church’s anti-Jewish practices, turned vehemently against “the Jews” upon realizing his efforts failed to convert them to Christianity (Prager and Telushkin Reference Prager and Telushkin2003). In his infamous 65,000-word treatise Von den Juden und Ihren Lügen (On the Jews and Their Lies), Luther characterizes Jews as burdens and pestilences, advocating their harm. Remnants of these depictions persist in German churches and cathedrals, such as the Judensau (German for “Jew’s sow”) in Wittenberg Church, underscoring the deep cultural roots of antisemitism in the Christian tradition. Taken together, these historical narratives form a pervasive network of concepts and meanings within Christian history that together constitute the cultural script of traditional antisemitism.Footnote 2

Modern Antisemitism

An arguably even more potent form of antisemitism, modern antisemitism, emerged during the eighteenth and nineteenth centuries, reaching its zenith during the Nazi regime in the early to mid-twentieth century. During this era, Jews were increasingly portrayed as being part of a distinct race rather than a distinct religious community (Brustein Reference Brustein2003). Practices of slavery, exploration, and imperialism in the eighteenth century increased contact between Europeans and non-Europeans, fostering concepts of racial superiority and inferiority (Efron Reference Efron1994). Social Darwinists misappropriated Darwin’s theories of natural selection and survival of the fittest and applied them to racial classification (Mosse Reference Mosse2020). Eugenicists similarly believed in inherited racial traits, advocating for the improvement of the “national stock” through selective breeding and discouraging reproduction among groups perceived as inferior, such as Jews (Kühl Reference Kühl1994). Increasingly aggressive nationalism intensified the othering and social exclusion of Jews. During the same period, the notion of a Jewish world conspiracy also gained adherents. Historians attribute the spread of these conspiracies to the emergence and rapid growth of an international socialist movement in which Jewish activists were disproportionately represented (Brustein Reference Brustein2003). Another significant contribution was the dissemination of the infamous Protocols of the Elders of Zion. This forged document originated in Tsarist Russia and purports to outline a plan for a Jewish world conspiracy in which Jews seek to control the world by subverting the existing sociopolitical order (N. Cohn [Reference Cohn1967] 2005). These manifestations of antisemitism were subsequently, and most prominently, embraced by the contemporary radical Right (Enstad Reference Enstad2021).Footnote 3

Important for our analyses, to which we turn now, the cultural script of modern antisemitism links Judaism to pseudo-scientific notions of racial hierarchy, socialism, Zionism, and world conspiracy—not to notions of Jews as the murderers of Jesus and the originators of disease, as in traditional antisemitism. This distinction allows us to empirically trace the activation of antisemitic prejudice during the COVID-19 pandemic to the cultural script of traditional antisemitism.

Design and Data

Our analysis proceeds through three separate but interrelated studies, each providing a distinct test of the theoretical model outlined above (cf. figure 1). Drawing on a hand-collected corpus of antisemitic texts and using natural language processing, study 1 sets the stage by demonstrating how the cultural scripts of modern and traditional antisemitism emerge from a corpus of antisemitic texts. Study 2 uses survey data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic and various regression techniques to explore several of the hypothesized relations in our theoretical model. These include the effect of pandemic exposure on antisemitic prejudice, detectable exclusively among Christians; the activation of the belief that “the Jews” killed Jesus, a prominent element of the cultural script of traditional antisemitism; and the effect of changes in this belief due to COVID-19 infections on antisemitism—a direct test of the cultural roots of antisemitic stereotypes.

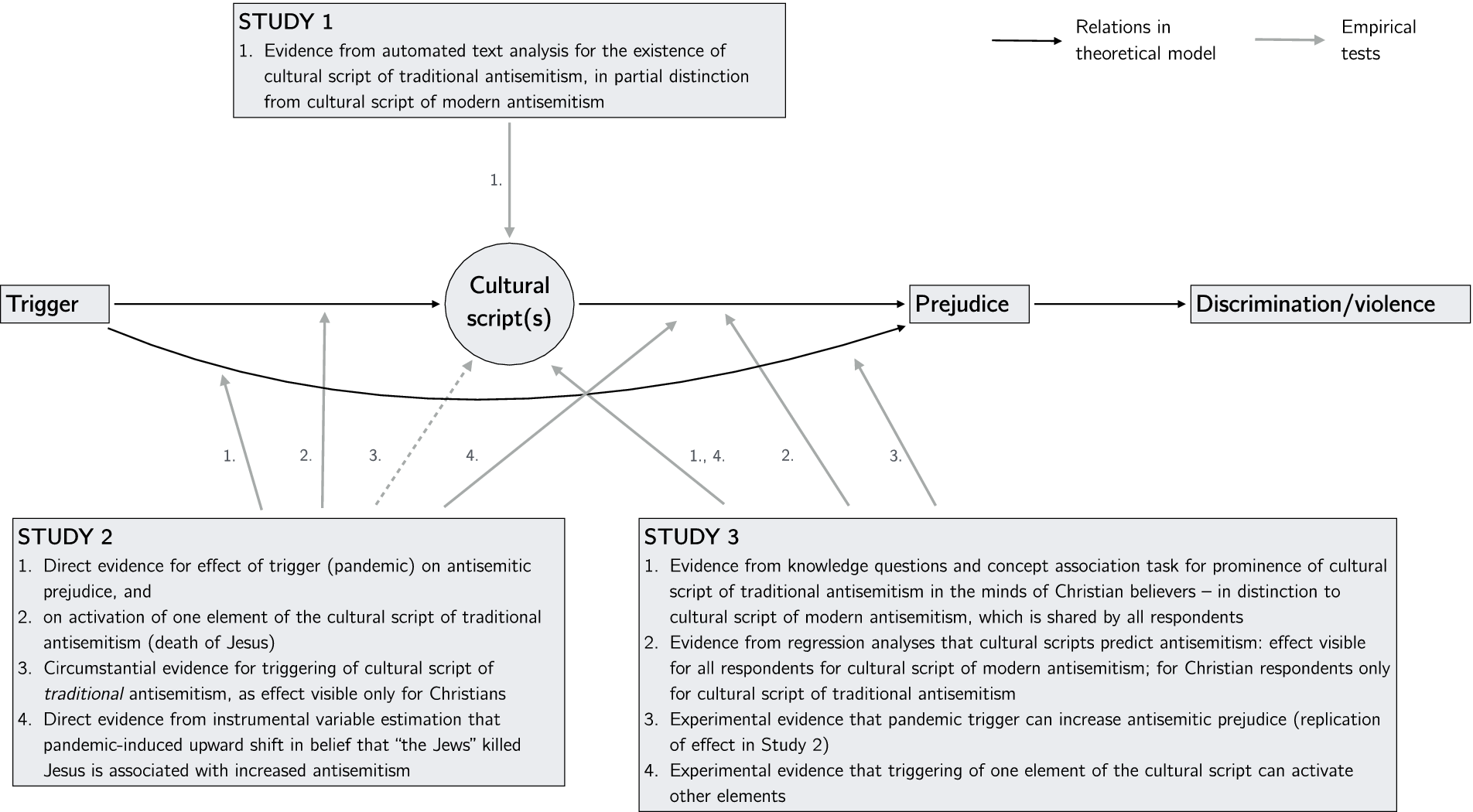

Finally, study 3 draws on a concept association task and survey experiments to further explore the concept of cultural script and its relation to prejudice. Among other aspects, we demonstrate that the cultural script of traditional antisemitism is detectable only among Christian believers, and provide observational evidence that cultural scripts predict prejudice. In two experimental studies, we further replicate the overall relationship between external triggers and prejudice, and provide experimental evidence on the inner workings of the cultural script by demonstrating that triggering one element of the script can activate another. A graphical overview of the role of each of the included tests is provided in figure 2. While none of these studies alone offers definitive proof of our theoretical model, we invite readers to consider the cumulative weight of evidence, and encourage future research to build on and refine our analytical approach.

Figure 2 Overview of Studies and Empirical Tests

Study 1: Cultural Scripts of Modern and Traditional Antisemitism in Antisemitic Texts

Above, we defined cultural scripts as networks of interconnected meanings that can be operationalized as networks of concepts. The purpose of this first study is to actually derive these networks by means of natural language processing. The main input in this process is a corpus of texts discussing and defining the meanings inherent to a given cultural script. We selected texts ostensibly dealing with the cultural scripts under consideration—in our case, traditional and modern antisemitism—but cast the net widely to avoid restricting potential networks from emerging ex ante.

Two comprehensive bibliographies of antisemitic writings formed the basis of our text corpus. The first source, Robert Singerman’s (Reference Singerman1982) Antisemitic Propaganda: An Annotated Bibliography and Research Guide, comprises over 1,900 entries, including numerous highly obscure ones. To manage the workload, we randomly sampled 210 texts from the compilation, of which we could locate 139. As a second source, we consulted the Radicalism Collection, an archive housed at the Michigan State University Library. This collection covers a range of antisemitic writings from various time periods. We focused on 84 titles with religious connotations, of which we could access 28. We further expanded our text corpus with two prominent antisemitic works: Adolf Hitler’s Mein Kampf, and The Protocols of the Elders of Zion. Additionally, we included two works by Martin Luther, the key figure of the German Reformation: Vom Schem Hamphoras and Von den Juden und Ihren Lügen. These works provide important historical insights into Luther’s views on Jews. Finally, we included the King James Version of the New Testament of the Holy Bible, recognizing that certain passages within this version contain antisemitic elements. The complete bibliography of the 172 antisemitic texts can be found in section F of the online appendix.

Our primary analysis method relies on word embeddings implemented by the GloVe algorithm (Pennington, Socher, and Manning Reference Pennington, Socher, Manning, Moschitti, Pang and Daelemans2014; Rodriguez and Spirling Reference Rodriguez and Spirling2022). GloVe models global co-occurrence patterns of words across the entire corpus by mapping words into a high-dimensional vector space, such that geometric relationships between vectors reflect semantic relationships between the corresponding words. GloVe learns these word vectors by factorizing a matrix of global word–word co-occurrence counts

![]() $ X $

, where each entry

$ X $

, where each entry

![]() $ {X}_{ij} $

reflects how often word

$ {X}_{ij} $

reflects how often word

![]() $ j $

appears in the context of word

$ j $

appears in the context of word

![]() $ i $

within a fixed window. The resulting vectors encode statistical information about how each word is used across the corpus.Footnote

4 This enables us to identify terms that are semantically or associatively linked to our target concepts. We visualize these relationships by applying the UMAP algorithm for dimensionality reduction (McInnes et al. Reference McInnes, Healy, Saul and Großberger2018) and plotting the connections between concepts in a two-dimensional space (figure 3). The distance between terms reflects the semantic similarity based on the co-occurrence patterns learned by GloVe.

$ i $

within a fixed window. The resulting vectors encode statistical information about how each word is used across the corpus.Footnote

4 This enables us to identify terms that are semantically or associatively linked to our target concepts. We visualize these relationships by applying the UMAP algorithm for dimensionality reduction (McInnes et al. Reference McInnes, Healy, Saul and Großberger2018) and plotting the connections between concepts in a two-dimensional space (figure 3). The distance between terms reflects the semantic similarity based on the co-occurrence patterns learned by GloVe.

Figure 3 Map of Word Embeddings for Terms Related to Cultural Scripts of Modern and Traditional Antisemitism in Corpus of Antisemitic Texts

Note: Figure visualizing the semantic relationships between selected word embeddings associated with the cultural scripts of modern and traditional antisemitism, as well as neutral reference terms (e.g., chair, together, table). The word embeddings are derived using the GloVe algorithm, and the high-dimensional embeddings are then projected into two dimensions using UMAP. The axes in the plot are abstract dimensions without a specific interpretation. Proximity in the plot reflects semantic similarity based on the co-occurrence patterns learned by GloVe.

In the upper half of figure 3, unrelated terms such as “chair,” “together,” and “table” (in brown) seem closely related in the texts, but have no connection to our target words “Jew” and “Jewish.” These target words instead cluster tightly with the terms “Zionist,” “race,” “world,” “communist,” and “capitalist” (in purple). We interpret this word cluster as capturing the cultural script of modern antisemitism, combining a racialized view of Judaism with accusations that Jews are plotting a global conspiracy. At some distance from our target terms, we observe another word cluster including the terms “blood,” “murder,” “libel,” “poison,” “plagu” (plague or plagues), and “diseas” (disease or diseases) (in blue).Footnote 5 We interpret this cluster as capturing the cultural script of traditional antisemitism linking Judaism to the betrayal and murder of Christ, and blaming Jews for the bubonic plague and other diseases.

We emphasize that these clusters are not chosen but instead emerge from the corpus of texts. This type of text analysis can be used to isolate cultural concepts from texts, thus offering a somewhat objective measure of culture, or, more specifically, cultural scripts. This is important from a scientific standpoint as our method is fully replicable with the provided corpus of texts and analysis code. Moreover, it can be readily expanded to different text corpora to derive additional cultural scripts. We believe that combining the concept of cultural script with natural language processing holds great promise for identifying culturally rooted theoretical constructs relevant to political science.Footnote 6

Study 2: Increased Antisemitism among Christian Believers upon Exposure to the COVID-19 Pandemic

Our second study uses data collected during the COVID-19 pandemic in Germany to demonstrate how the pandemic activated antisemitic sentiments related to the cultural script of traditional antisemitism among Christian believers, as per our theoretical argument. Between March 2020 and February 2021, we fielded 23 rounds of a repeated cross-sectional survey on the attitudinal correlates of the COVID-19 crisis. The survey was administered by a reputable survey institute that maintains an online access panel in Germany. By means of quota sampling, the sample was made representative for the German resident population in terms of age, gender, educational background, and migration background. Item categories included demographic background information, detailed questions on exposure to the COVID-19 pandemic, and outcome indicators to capture antisemitism and other out-group attitudes. In total, we collected 17,700 responses, which we can connect to contextual measures and COVID-19 incidence rates through the zip code of the respondents’ place of residence.Footnote 7

To capture antisemitism, we measured both cognitive and affective antisemitism (Kovács Reference Kovács2010). Cognitive antisemitism was measured with three survey items, one asking for the alleged undue influence of Jews on the economy, another on the misuse of the memory of the Holocaust by Jews, and a third linking opposition to policies of the state of Israel to antisemitic attitudes.Footnote 8 To obscure the purpose of the question battery, the items were presented alongside items on attitudes toward migration. Affective antisemitism was measured using a feeling thermometer (Nelson Reference Nelson and Lavrakas2008), where respondents were asked how positive they feel toward various groups. These groups included Germans and Jews as well as Americans, Turks, Muslims, and asylum seekers. To avoid capturing differences between individuals that are due to an alternate usage of the thermometer scale, we use the adjusted feeling thermometer score.Footnote 9 As described in our pre-analysis plan, the adjusted measure is the difference between the item measuring antisemitism and the average of all other items. This score provides a purer measure of antisemitism as it is not biased by a general tendency to dislike people. To generate a summary index, we calculate the average of (1) the mean of the standardized responses to the three cognitive antisemitism items and (2) the inverted standardized score of the adjusted feeling-thermometer item for Jews (Cronbach’s alpha = 0.71).

To measure the impact of the pandemic at the individual level, we asked respondents whether they had contracted the coronavirus as confirmed by a test. A total of 410 respondents (2.3%) reported a positive test. To operationalize the contextual effect of the pandemic, we use county-level, seven-day incidence rates of COVID-19 infections provided by the Robert Koch Institute (2021), Germany’s official public health body. The seven-day incidence rate is an epidemiological measure that is defined as the number of new cases of COVID-19 infections within the past week per 100,000 inhabitants. Each observation in our sample was matched with the respective incidence rate on the date of the administration of the survey at the reported county of the respondent. The county-level seven-day incidence rates varied between zero and 706.6. To ease the interpretation of the results, we rescale the incidence rate to range from zero to one hundred.

Empirical Strategy and Analyses

Our identifying assumption is that individuals who caught the disease or lived in heavily affected areas were just as prone to antisemitism as individuals who escaped the disease or lived in less affected areas. To support this claim, we employ a variety of methods and model specifications. In the regression analyses, we control for a range of pretreatment demographic and situational factors that are known to increase the risk of contracting and falling ill from the disease, on the off chance that these are also correlated with antisemitic attitudes. These include the respondent’s gender, education, occupation, option to work from home, housing conditions, the person’s health status, and the nationality of the respondents and their parents. Additionally, we include control variables that may explicitly confound the relationship between disease exposure and antisemitism—that is, variables that affect both the susceptibility for contracting the disease and antisemitic beliefs. These variables include the respondents’ age, church attendance, and political orientation, and a battery of questions on compliance behavior with containment measures during the pandemic. In section C of the online appendix we discuss in detail why we control for these variables and how we operationalize them, and present summary statistics.

In terms of contextual effects, we include common predictors that make areas vulnerable to the spread of diseases, including population density, foreign population share, the number of asylum seekers, population proportions older than 60 and 75, and indicators of poverty and precariousness such as the share of individuals without a school degree, the local gross domestic product per capita, and monthly unemployment rates. Finally, to flexibly account for time trends in the development of the pandemic, our model controls for the interview date and includes fixed effects for the interview month and year. Further specifications include local-area-level (zip code) fixed effects.

Overall Effect of Exposure to the Pandemic

Table 1 shows the overall effect of having contracted COVID-19 (panel A) and living in areas heavily affected by the pandemic (panel B) on antisemitic attitudes. We present several specifications: model 1 includes individual-level and context-level controls, model 2 uses entropy balancing (Hainmueller Reference Hainmueller2012) to prebalance covariates (see table A4 in the online appendix for balance statistics), and model 3 adds zip code area and county fixed effects—that is, it calculates the effect of an infection for individuals residing in the same zip code area or county.

Table 1 Antisemitism and Disease Exposure

Note: Effect of individual COVID-19 infection (panel A) and county-level incidence rate (panel B) on the antisemitism scale. Full regression outputs in tables A6 and A7 in the online appendix. Differences between overall and Christians-only effects significant at the 5% level (cf. table A17 in the online appendix). Ordinary least squares (OLS) regression. Standard errors in parentheses. Models 1–3 show effects for the whole sample, models 4–6 for Christian believers only. Models 1 and 4: full controls. Models 2 and 5: entropy balanced. Models 3 and 6: zip code/county-level fixed effects. a p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Contracting the coronavirus is associated with a five percentage-point increase in the antisemitism index (panel A, model 1). Balancing the sample leaves the estimate virtually unchanged (panel A, model 2), while including zip code-level fixed effects (n = 5,097) reduces the estimated effect by one percentage point (panel A, model 3). A similar pattern can be observed when considering the impact of the county-level seven-day incidence rate on antisemitic attitudes. Overall, a one percentage-point increase in the country-level seven-day incidence rate corresponds to a 0.6 percentage-point increase on the antisemitic attitudes scale (panel B, model 1). The effect increases slightly in magnitude upon prebalancing covariates (panel B, model 2) but disappears upon the introduction of county-level fixed effects (n = 389). This latest specification (panel B, model 3) is important because it corresponds to a quasi-panel of counties over time, since incidence rates are measured on the county level. In other words, the fixed-effects specification picks up the effect of dynamic changes in the incidence rate on deviations from the county-level averages in antisemitism during the first year of the pandemic. As shown, there seems to be no overall association between the dynamics of the spread of COVID-19 and changes in antisemitism.

Effect among Christian Believers Only

Next, we analyze whether the impact of the pandemic depends on the religious denomination of the respondents. If the heightened negative attitudes toward Jews were rooted in the cultural script of traditional antisemitism, we should see stronger effects among Christian believers. Models 4–6 in table 1 replicate the analyses introduced above, but restrict the sample to Christian believers only. As shown in the bottom row of the panels, baseline scores are similar to those in the full sample, indicating that Christian believers’ levels of antisemitism are near the average. This said, effects differ starkly. Among Christians, exposure to the pandemic is associated with higher levels of antisemitism across all models. Contracting the virus results in a seven-point increase in the antisemitism index (panel A, models 4–6), and a one percentage-point increase in the county-level incidence rates is associated with a one to 1.5 percentage-point increase in the antisemitism index (panel B, models 4–6).

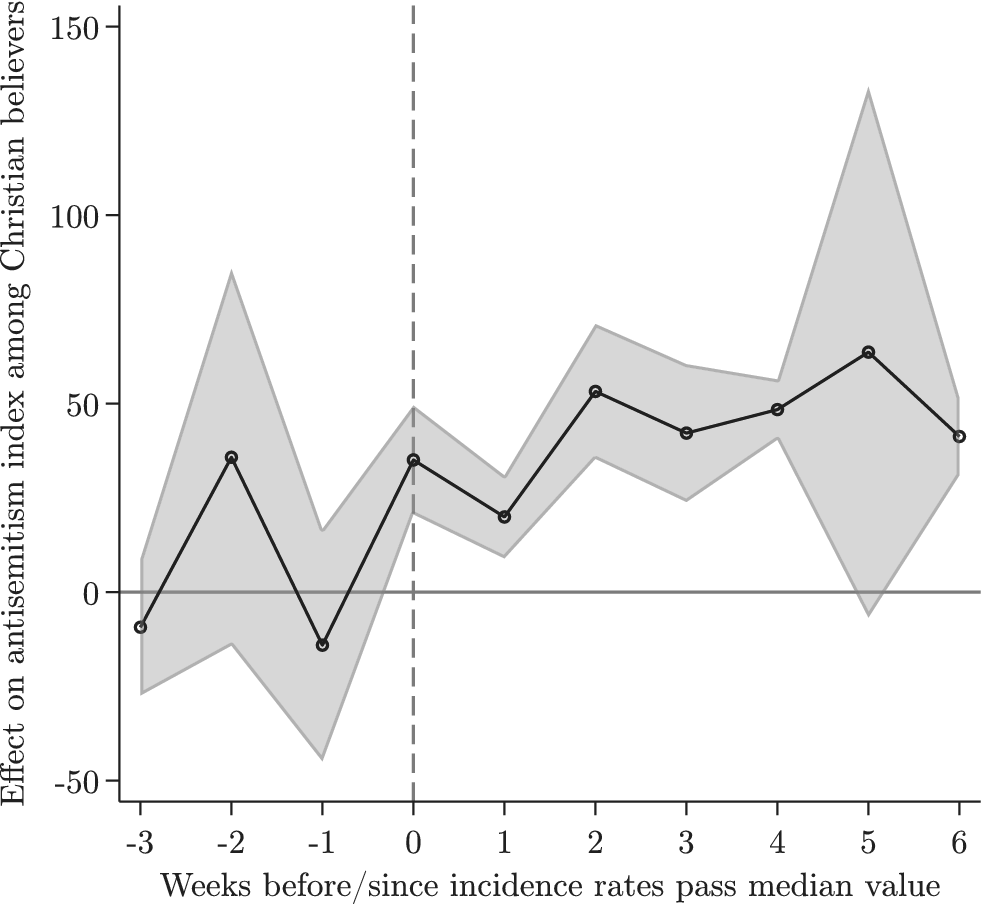

The quasi-panel structure of the county-level fixed-effects specification allows us to use a staggered differences-in-differences model—as introduced by Callaway and Sant’Anna (2021) and Sant’Anna and Zhao (Reference Sant’Anna and Zhao2020)—with our data. This model compares changes in antisemitism among Christian believers in heavily affected (i.e., treated) counties to changes in antisemitism in comparable unaffected or not-yet-affected counties. We define the treatment condition as incidence rates that are greater than the median value for the period of consideration, and the control condition as incidence rates below this threshold.Footnote 10 As shown in figure 4, in weeks prior to a county experiencing above-median incidence rates, levels of antisemitism are indistinguishable from those in counties in the control condition. However, upon passing the threshold, levels increase steeply and remain elevated throughout the observable period (six weeks after passing the threshold).

Figure 4 Differences-in-Differences Effect of High Incidence Rates on Antisemitism

Note: Effect of passing incidence-level threshold on antisemitism index among Christian believers. Markers are week-by-week point estimates, shaded areas are 95% confidence intervals.

In section E.5 of the online appendix we further disaggregate our results by religious affiliation and religiosity. Contracting COVID-19 has an effect among Catholic and Protestant Christian respondents only, while the effect is positive but statistically insignificant among Orthodox Christians, negative and insignificant among Muslims, and precisely null among nonbelievers—a pattern consistent with the prediction that the cultural script of traditional antisemitism should be activated only among the subgroup of individuals who putatively share it: Christian believers.

In line with our findings on the individual level, the contextual effects of the pandemic only appear in Christian-majority regions. As shown in figure A5 in the online appendix, the effect of the seven-day incidence rate on antisemitism increases with the share of Christians in a municipality, only becoming statistically significant in (western German) municipalities where the share of Christians exceeds 50%.

Disease Exposure and Belief that “the Jews” Killed Jesus

As a further test to demonstrate that what we are observing is indeed the activation of the cultural script of traditional antisemitism, we examine another central element of this script: the belief that Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus. As shown in our word-embedding analysis (figure 3), the word “murder” (of Christ) formed part of the word cluster that identified traditional antisemitism in our antisemitic texts corpus. The belief that Jews were responsible for the death of Christ has embittered relations between Christianity and Judaism for nearly two millennia, with the principal source of this accusation being Matthew 27:17–25 (Brustein Reference Brustein2003).

This said, content-wise, there is no clear reason why this belief should relate to the idea that Jews spread diseases, other than both beliefs forming part of the same cultural script. Examining if the belief that Jews murdered Jesus is activated at the same time as the association between Judaism and diseases thus serves as a test of the interconnection between these concepts in Christian believers’ minds. Accordingly, our survey included a question asking participants to identify who was responsible for Jesus’s death, providing as answer options “the Romans,” “the Jews,” “his followers,” “someone else,” and “don’t know.”Footnote 11

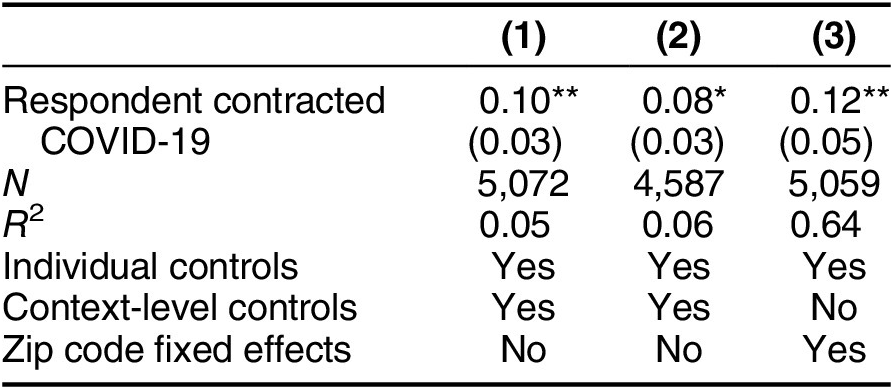

Table 2 shows regression results, with a dependent variable that equals one if respondents identified “the Jews” as responsible for Jesus’s death, and zero otherwise. The estimates reveal a strong correlation between contracting COVID-19 and the belief that “the Jews” killed Jesus among Christians; there is no effect for non-Christians. Christian believers who contracted COVID-19 were eight to 12 percentage points more likely to hold this belief than those who did not. In summary, not only did exposure to the pandemic increase general antisemitic sentiment, but it also appears to have triggered beliefs about Jews as the murderers of Jesus—a core element of the cultural script of traditional antisemitism.

Table 2 Belief that “the Jews” Killed Jesus and Disease Exposure among Christian Respondents

Note: Effect of contracting COVID-19 on the belief that “the Jews” killed Jesus. OLS estimates. Model 1: full controls. Model 2: entropy balanced. Model 3: zip code fixed effects. a p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

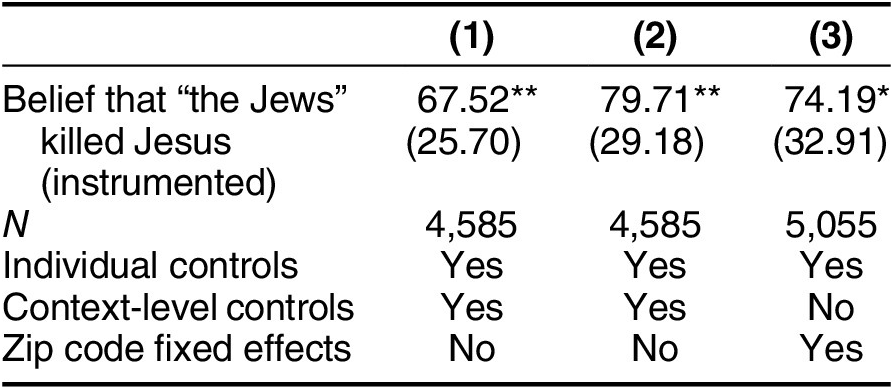

Instrumental Variable Analysis Linking Belief Activation to Antisemitic Prejudice

As a final step in the analysis, we assess whether the pandemic-induced shift in traditional antisemitic beliefs translated into higher levels of manifest antisemitic prejudice, as measured by our antisemitism index. A naive approach would regress the index directly on the belief that “the Jews” killed Jesus. However, this relationship is likely confounded: individuals predisposed to antisemitism may be both more likely to hold such beliefs and to score higher on the prejudice index. To address this endogeneity, we exploit the plausibly exogenous variation in traditional antisemitic beliefs induced by the COVID-19 pandemic, using a two-stage least-squares instrumental variable strategy.

The first-stage results—the effect of contracting COVID-19 on the belief that Jews were responsible for the death of Jesus—were already shown in table 2. The corresponding F-statistic is 11.74, confirming instrument relevance (Stock, Wright, and Yogo Reference Stock, Wright and Yogo2002). Table 3 presents the second-stage results, where we regress the antisemitism index on the variation in traditional antisemitic belief caused by COVID-19 infection, thus estimating the complier average treatment effect. Effect sizes are statistically significant and substantively strong. In other words, individuals in whom the cultural script of traditional antisemitism was activated by exposure to the pandemic display markedly higher levels of antisemitic sentiment, consistent with theoretical expectations. While this approach uses only one element of the cultural script of traditional antisemitism—rather than a summary indicator for the script as a whole, as attempted below—it nonetheless provides direct evidence that activation of a culturally rooted belief may contribute to manifest antisemitic prejudice.

Table 3 Second-Stage Estimates for Effect of Pandemic-Induced Shift in Traditional Antisemitic Beliefs on Antisemitism Index

Note: Second-stage effect for pandemic-induced shift in traditional antisemitic beliefs on the antisemitism index. OLS estimates with standard errors adjusted for the two-stage least-squares procedure. Model 1: full controls. Model 2: entropy balanced. Model 3: zip code fixed effects. a p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Ruling Out Alternative Explanations

In the theory section, we discussed various potential explanations for increasing out-group hostility. We now show that none of these explanations are likely to account for our finding that exposure to the pandemic went along with increased antisemitism among Christian respondents.

Activation of Modern Antisemitism

First, the rise in antisemitism following the COVID-19 pandemic could be attributed to modern, right-wing antisemitism rather than the cultural script of traditional antisemitism. To rule out this explanation, we examine the pandemic’s effects based on support for far-right parties. As shown in figure A8 in the online appendix, contracting COVID-19 affected antisemitism among mainstream center-right (Christian Democratic Union/Christian Social Union, CDU/CSU) and center-left (Social Democratic Party, SPD) party supporters. Remarkably, however, COVID-19 infections had no effect on far-right Alternative for Germany (AfD) supporters’ antisemitic attitudes.Footnote 12 This finding is supported by figure A9 in the online appendix, showing that the seven-day incidence rate’s impact on antisemitism is not moderated by the share of AfD votes in the 2017 elections. Consequently, we rule out the possibility that the pandemic’s impact on antisemitic attitudes can be attributed to modern, far-right antisemitism as indicated by electoral support for the AfD.

Material Threat and Competition

Second, research often traces negative out-group attitudes to rising numbers of perceived out-groups and heightened competition over economic opportunities or public goods (e.g., Dancygier Reference Dancygier2010; Olzak Reference Olzak1992). By this logic, prejudice against Jews in Germany should reflect material threats and resource competition. Yet Germany’s Jewish community is small and declining (ZWST 2022). Still, local Jewish congregations might be perceived as an out-group threat. Contrary to this expectation, however, COVID-19 infections have virtually no effect on antisemitic attitudes among respondents living near a Jewish congregation (figure A10 in the online appendix).

We also examine the effect of COVID-19-related unemployment risk on antisemitic attitudes. Figure A11 in the online appendix shows a positive correlation between unemployment risk and antisemitism across all religious groups, including nonbelievers. While unemployment risk thus seems to shape antisemitic sentiments, it is not moderated by respondents’ religious affiliations. Importantly, our main results on the effect of COVID-19 infection remain robust after accounting for both individual- and context-level unemployment measures (table 1) as well as pandemic-related dismissal risk (table A18 in the online appendix). Given these results and the small, declining Jewish population in Germany, material and competition-based explanations appear unlikely in this context.

Place-Based Legacies

Third, prior research shows that racism and antisemitism vary with regional history (e.g., Acharya, Blackwell, and Sen Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2016; Reference Acharya, Blackwell and Sen2018; Charnysh Reference Charnysh2015; Kopstein and Wittenberg Reference Kopstein and Wittenberg2018; Voigtländer and Voth Reference Voigtländer and Voth2012). To rule out such legacies as drivers of our findings, we test whether the effect of contracting COVID-19 on antisemitic attitudes is shaped by historical features of respondents’ places of residence identified in prior literature. Drawing on data from Falter and Hänisch (Reference Falter and Hänisch1990) and Voigtländer and Voth (Reference Voigtländer and Voth2012), we examine the moderating effect of six contextual characteristics: the Jewish population share in 1925, the prevalence of medieval Jewish settlements (1238–1350), NSDAP (Nazi Party) vote shares in 1928 and 1933, and two pogroms (the Black Death pogrom of 1349 and one in the 1920s; see figures A12 and A13 in the online appendix). Our analyses show that COVID-19 infection increases antisemitic attitudes irrespective of these factors, supporting our argument that we are examining cultural rather than place-based legacies.

Symbolic Threat and Identity

Finally, symbolic threat theory holds that individuals will develop an exaggerated in-group identity and reject ethnic or racial outsiders if they perceive their value systems or worldviews to be threatened by outside forces. Importantly, this effect should apply to all groups considered outsiders. We therefore examine whether contracting COVID-19 also influenced attitudes toward two other salient out-groups, namely Muslims—a religious out-group—and asylum seekers—a status and ethnic out-group. As shown in figures A14 and A17 in the online appendix, neither attitudes toward asylum seekers nor toward Muslims are impacted, and this finding holds independent of religious affiliation or strength of religious conviction. In other words, contracting the virus uniquely influenced attitudes toward Jews among Christian believers, making it unlikely that general racial animus is driving our results.

Study 3: Functioning and Effects of Antisemitic Cultural Scripts among Christian Believers

The tests above provide circumstantial evidence that exposure to the disease activated the script of traditional antisemitism among Christian believers. In study 3, we delve deeper into the cognitive associations related to cultural scripts among individuals and demonstrate the existence of the proposed cultural script of traditional antisemitism among Christian believers and how it shapes their beliefs. To this end, we designed a second individual-level survey (n = 2,000). Our participants were recruited online by a reputable research firm in December 2023, and our sample was made representative for the larger German population in terms of age and sex by quota sampling. Given our focus on the attitudes of Christian believers, we oversampled this group at a 70:30 ratio, with around 70% of our sample comprising self-declared Christians from diverse denominations. Our main measures of interest are a set of knowledge questions, a concept association task, and two priming experiments. Alongside these measures, we collected demographic data and information regarding respondents’ places of residence, enabling us to include a similar set of individual and structural control variables in our models as in study 2.Footnote 13

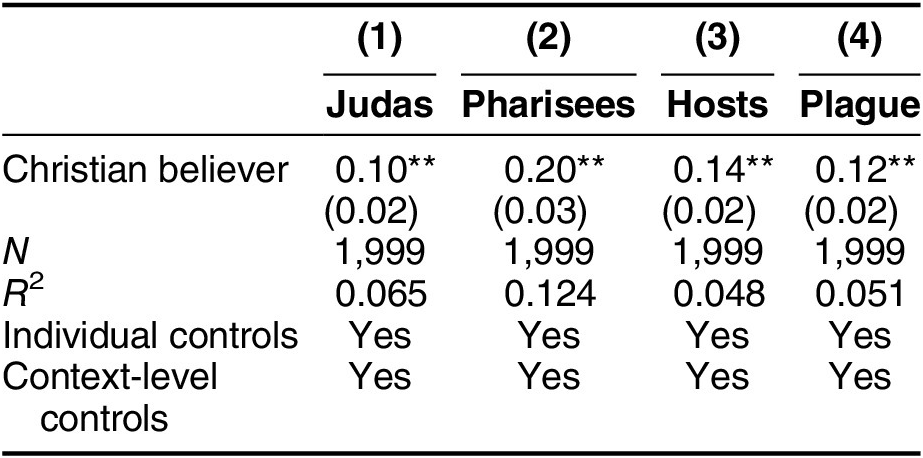

Knowledge Questions

To assess the presence of the cultural script of traditional antisemitism among Christian believers, we included a set of four knowledge questions concerning familiarity with elements related to this cultural script. For each question, we offered two false answers, one correct answer, and a “don’t know” option. We asked respondents if they knew about Judas Iscariot’s infamous act according to the New Testament (he betrayed Jesus for 30 pieces of silver), who the Pharisees were (a religious and political movement in ancient Judaism), what was meant by the so-called desecration of the host in the Middle Ages (the accusation that Jews defiled consecrated bread used in the Christian Eucharist), and how the spread of the bubonic plague was explained in the Middle Ages (“by poisoned wells”). We assigned a value of one to correct answers and zero to all other answers, and regressed this measure on our indicator for being Christian along with all control variables. We expect Christians to be more knowledgeable about these questions, which are closely related to the cultural script of traditional antisemitism. In line with our expectations, Christians are consistently more likely to provide the correct answer across all four knowledge questions (table 4), indicating that Christian believers are indeed more versed in concepts that constitute parts of the cultural script of traditional antisemitism.

Table 4 Differences in Share of Correct Answers in Knowledge Test among Christians and Non-Christians

Note: Differences in share of correct answers between Christians and non-Christians in the four questions inquiring about cultural knowledge related to traditional antisemitism. OLS regression. Standard errors in parentheses. a p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Concept Association Task

As a core measure of interest, we included a concept association task in our survey. In the concept association task developed by Hunzaker and Valentino (Reference Hunzaker and Valentino2019), respondents are shown pairs of concepts and asked to indicate quickly and instinctively whether they are associated. This procedure yields a map of how concepts are linked in respondents’ minds. Because we define cultural scripts as belief networks that can be represented by such concept associations, the concept association task provides a way to capture the cultural scripts present in respondents’ minds.

Alongside the terms “Judaism/Jew,” “Christianity/Christians,” and “Islam/Muslims” (the latter two included to make our interests in concepts associated with Judaism less obvious) we included concepts related to traditional antisemitism, notably blood, poison, disease, pestilence, well, the death of Jesus, and betrayal. We also included concepts related to modern antisemitism, notably race, money, world domination, capitalism, communism, Zionism, and greed. Every respondent was shown all

![]() $ C\left(\mathrm{17,2}\right)=\frac{17!}{2!\left(17-2\right)!}=136 $

possible pairs of concepts (in fully randomized order), and was asked to indicate whether there was a connection in their mind between each pair of concepts. Our hypothesis was that Christian believers would connect Judaism with concepts rooted in both traditional and modern antisemitism, but that the former association would be absent among non-Christians.

$ C\left(\mathrm{17,2}\right)=\frac{17!}{2!\left(17-2\right)!}=136 $

possible pairs of concepts (in fully randomized order), and was asked to indicate whether there was a connection in their mind between each pair of concepts. Our hypothesis was that Christian believers would connect Judaism with concepts rooted in both traditional and modern antisemitism, but that the former association would be absent among non-Christians.

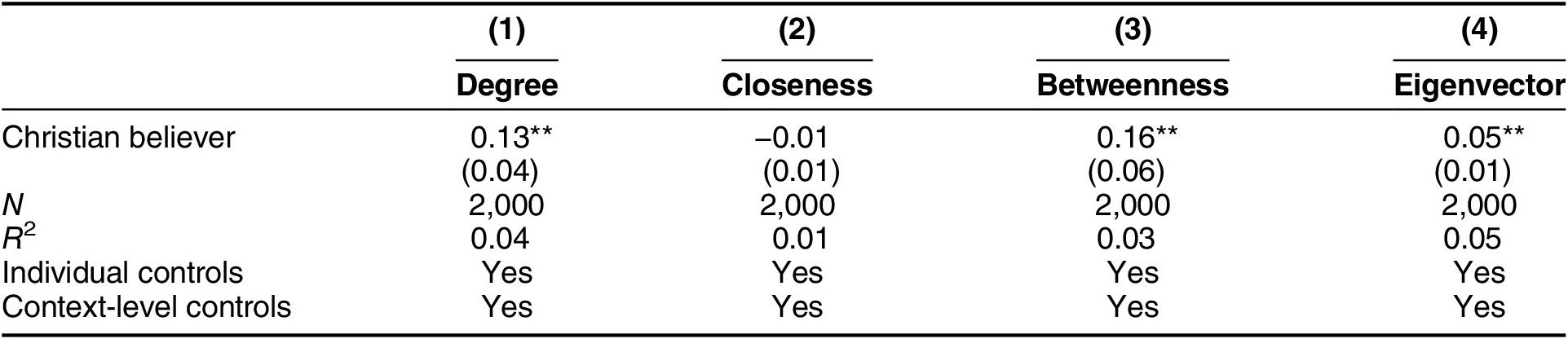

We analyze the data obtained from the concept association task in two ways: graphically, and by means of network analysis. Figure 5 shows examples from a random sample of individual-level concept association networks among Christians and non-Christians. While there is considerable heterogeneity regarding where individuals perceive connections, three observations stand out, all in line with our hypothesis: First, Christian concept association networks tend to be denser than those of non-Christians, indicating a greater number of overall connections. Second, there seems to be a higher number of network nodes originating from Judaism. Third, concepts related to traditional antisemitism tend to be more closely linked to Judaism.

Figure 5 Sample of Individual-Level Concept Association Networks among Non-Christians and Christians

To formalize these intuitions, we first calculate indicators of network centrality of Judaism in each concept association network. Here, we expect Judaism to be more central in networks of Christians as compared with non-Christians. The results are presented in table 5. As can be seen, Judaism clearly takes a more central place in the concept association network among Christians. Second, we calculate the network distance—the length of the shortest path between two nodes—between the concept of Judaism or Jew and concepts relating to the elements of the cultural scripts of (1) traditional antisemitism (like blood, poison, or well), and (2) modern antisemitism (like money, race, and capitalism). We then regress these distances on the indicator for being a Christian believer. Here, we expect to see negative coefficients for Christians. As shown in table 6, this is indeed what we find. Network distances between Judaism and concepts relating antisemitism are clearly shorter for Christians as compared with non-Christians.

Table 5 Differences in Network Centrality of Judaism/Jew in the Concept Association Networks of Christians and Non-Christians

Note: Differences in network centrality of Judaism/Jew in concept association networks of Christians versus non-Christians. OLS regression. Standard errors in parentheses. a p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

Table 6 Difference in Network Distance between Judaism/Jew and Elements of the Cultural Scripts of Traditional and Modern Antisemitism for Christians and Non-Christians

Note: Network distance in individual-level concept association networks including Judaism and concepts relating to traditional (panel A) and modern (panel B) antisemitism, regressed on the indicator for being a Christian believer. Full regression output in tables A12 and A13 in the online appendix. OLS regression. Standard errors in parentheses. a p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

This difference is driven by the partial networks including terms relating to traditional antisemitism, where distances are around 0.7 edges shorter (panel A). As expected by the theory, differences are smaller (and often not statistically significant) for the partial network including concepts belonging to modern antisemitism (panel B). In other words, Christians seem to systematically associate Judaism with concepts belonging to the cultural script of traditional antisemitism, the triggering of which plausibly led to an increase in expressed antisemitic sentiment.

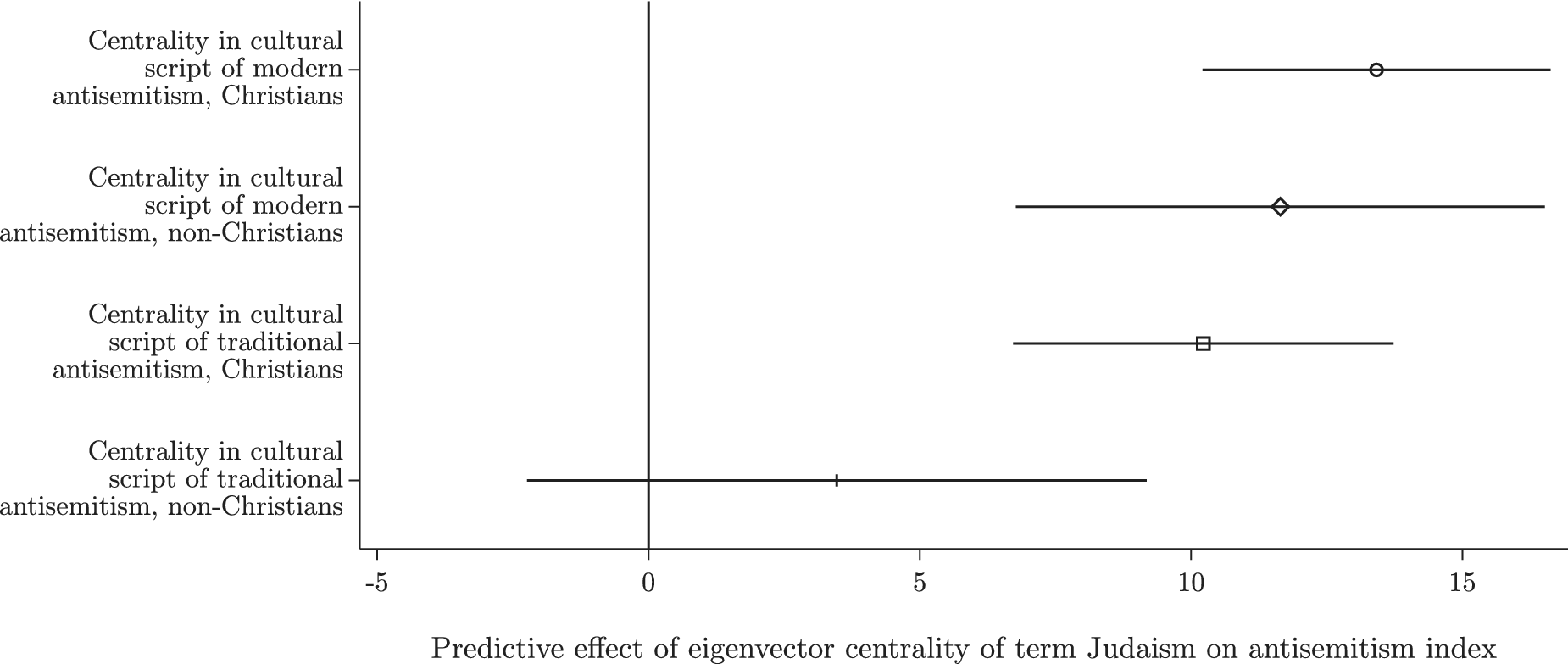

Predictive Effects of Centrality Measures on Prejudice

As further explained below, our survey included the same antisemitism item as used in study 2, capturing cognitive and affective antisemitism. In combination with the centrality and distance measures, this allows us to explore the relationship between cultural scripts and prejudice. Our preferred specification uses the eigenvector network centrality of Judaism in the concept association tasks—as the single best individual measure of the degree to which cultural scripts are present in respondents’ minds—as a predictor for the antisemitism index, measuring antisemitic prejudice. As per our theory, we expect there to be a positive correlation between these two measures, especially among Christians. For this test, we calculated two centrality measures for Judaism for the subnetworks of concepts associated with either traditional or modern antisemitism (i.e., the concepts listed in table 6, panels A and B). We then regressed the antisemitism index on these centrality measures, including our full set of controls, including self-placement on the left–right scale and voting intentions.

Core results are shown in figure 6, and full regression output is shown in table A14 in the online appendix. Overall, network centrality is an extraordinarily strong predictor of antisemitic prejudice, similar to or larger in size (as measured by the beta coefficient) than political orientation, the otherwise strongest predictor by far. The next aspect to note is that for modern antisemitism, this is true for all respondents, Christian or not. This contrasts with results for network centrality in the cultural script of traditional antisemitism. Here, the relationship with antisemitic prejudice is only visible for Christians, for whom it is almost as strong a predictor as centrality in the cultural script of modern antisemitism. In contrast, there is no relationship for non-Christians. This analysis thus provides correlational, but substantively strong, evidence for a close relation between the cultural scripts and manifest antisemitic prejudice.

Figure 6 Predictive Effect of Network Centrality Measures on Antisemitism

Note: Predictive effect of the eigenvector centrality of the term “Judaism” in the concept association networks for modern and traditional antisemitism on antisemitic prejudice among Christian and non-Christian respondents.

Priming Experiments

As a final measure we included two priming experiments in our survey, which we will discuss in turn. These experiments were added a few days into the data collection, so we can only draw on reduced sample sizes (n = 1,600 and n = 1,400, respectively). In our first priming experiment, we sought to reconstruct the overall effect of exposure to the pandemic on antisemitism.

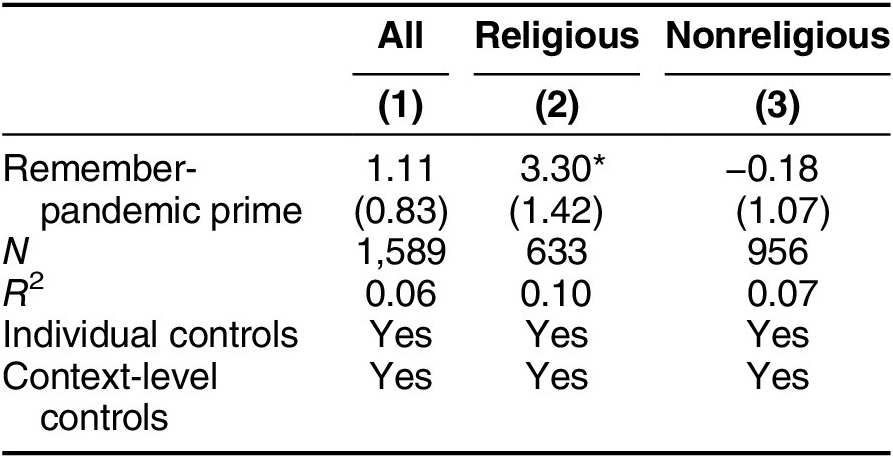

To this end, we asked a randomly assigned half of the respondents to recall the early phase of the pandemic. Those in this group were asked to recall their feelings when the first images of people falling ill and dying from COVID-19 arrived in Germany. The other half was assigned to the control group and asked to reflect on the poor state of Germany’s transportation infrastructure. After the priming, both groups were asked the same antisemitism questions used in the large-N survey. Table 7 presents the results of a regression of the outcome on the treatment indicator, plus our standard set of controls. While the coefficient is positive, with treated individuals scoring about one point higher on the antisemitism index, it remains short of being significant. Examining heterogeneity, we see that there was no treatment effect among the nonreligious. However, the prime increased antisemitism among the religious, where the index rose by three points among the treated (p < 0.05).Footnote 14 The results demonstrate that even a relatively mild disease-related trigger can activate antisemitic stereotypes, albeit only among the religious.

Table 7 Effect of Priming Memories of the Pandemic on Antisemitism

Note: Effect of remembering the early stages of the pandemic versus the bad state of German transport infrastructure on antisemitism, for different groups of respondents. OLS regression. Standard errors in parentheses. a p < 0.1; * p < 0.05; ** p < 0.01.

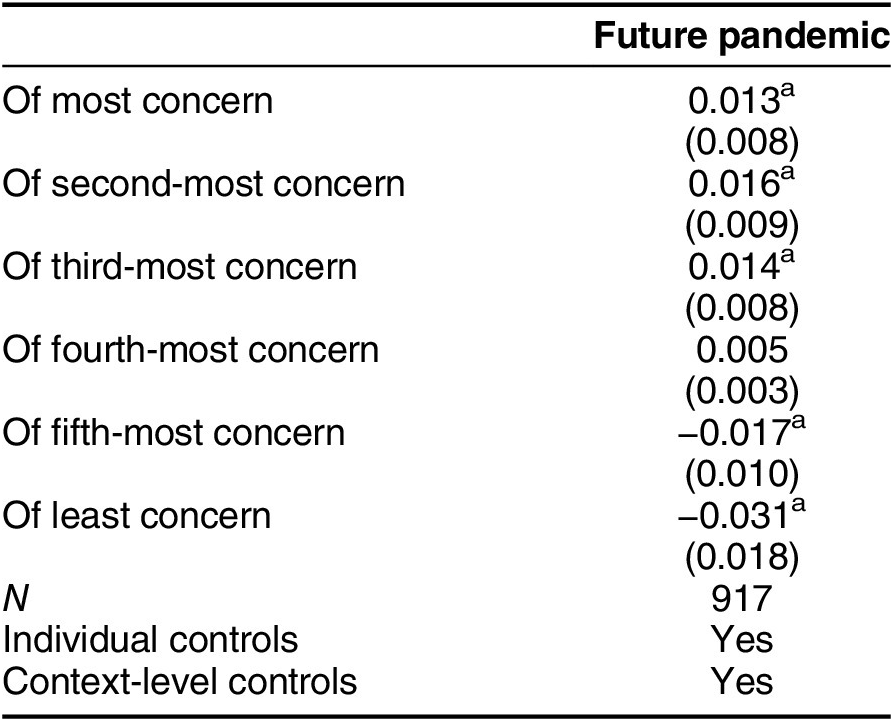

This first experiment thus provides additional support for the effect of pandemic exposure on antisemitism. Our second priming experiment was designed to provide evidence for the internal dynamics of cultural scripts, particularly the notion that they are networks of interconnected yet not necessarily semantically related meanings. A central claim of our theory is that activating one element of the cultural script can activate another, as long as the latter is part of the same cultural script. To test this claim, we exposed the treatment group to an illustration of Jesus’s betrayal by Judas, and tested whether this prime could activate concerns with diseases—the logic being that both “betrayal” and “disease” are part of the cultural script of traditional antisemitism, so triggering one element should activate the other. We randomly assigned participants to view either of the two pictures displayed in figure 7. The treatment group was exposed to a picture of Jesus’s betrayal by Judas, whereas the control group was exposed to an angel appearing to the shepherds on the night Jesus was born.Footnote 15

Figure 7 Treatment and Control Pictures of the Experiment Priming the Betrayal of Jesus