1. Introduction

Drag reduction in turbulent flows can be achieved by introducing a thin lubricating layer near the wall, which reduces frictional losses (Joseph et al. Reference Joseph, Bai, Chen and Renardy1997). This strategy has been extensively studied through experiments and has found industrial applications, particularly in the transport of crude oil through pipelines (Isaac & Speed Reference Isaac and Speed1904; Looman Reference Looman1916; Joseph et al. Reference Joseph, Renardy and Renardy1984, Reference Joseph, Bai, Chen and Renardy1997; Hu & Joseph Reference Hu and Joseph1989). Another widely explored approach to drag reduction involves the addition of polymeric additives, which alter the rheological behaviour of the fluid and lead to significant friction reduction (Forrest & Grierson Reference Forrest and Grierson1931; Virk Reference Virk1975; White & Mungal Reference White and Mungal2008; Wang et al. Reference Wang, Yu, Zakin and Shi2011). In this study, we aim to combine these two mechanisms by employing a non-Newtonian lubricating layer to facilitate the flow of a Newtonian core fluid.

Beyond its industrial relevance, this configuration is also relevant in biomedical contexts, such as the human respiratory tract, where a thin mucus layer – characterised by viscoelastic and shear-thinning properties – modulates airflow resistance (Fontanari et al. Reference Fontanari, Zattara-Hartmann, Burnet and Jammes1997; Sue-Chu Reference Sue-Chu2012; Fazla et al. Reference Fazla, Erken, Izbassarov, Romanò, Grotberg and Muradoglu2024). While not the main focus of this study, such parallels highlight the broader relevance of understanding how non-Newtonian lubricating films interact with turbulent flows under the influence of surface tension.

Despite their practical importance, multiphase flows involving non-Newtonian fluids have received relatively limited attention. While a substantial body of work exists on single-phase non-Newtonian laminar and turbulent flows (Arosemena, Andersson & Solsvik Reference Arosemena, Andersson and Solsvik2021; Amor et al. Reference Amor, Soligo, Mazzino and Rosti2024; Serafini et al. Reference Serafini, Battista, Gualtieri and Casciola2024; Milocco et al. Reference Milocco, Giamagas, Zonta and Soldati2025; Rosti Reference Rosti2025; Xu et al. Reference Xu, Zhang, Brandt, Song and Shishkina2025), far fewer studies have addressed multiphase systems. Several works have focused on the motion of rigid particles – both spherical and non-spherical – in non-Newtonian fluids (D’Avino et al. Reference D’Avino, Greco and Maffettone2017; Lu et al. Reference Lu, Liu, Hu and Xuan2017; Datt & Elfring Reference Datt and Elfring2018; Zenit & Feng Reference Zenit and Feng2018; Hu et al. Reference Hu, Yu, Atomsa and Zhao2024; Habibi et al. Reference Habibi, Iqbal, Ardekani, Chaparian, Brandt and Tammisola2025). However, when gas–liquid or liquid–liquid systems are considered, the literature is sparse, particularly regarding interface-resolved simulations. Most studies in this area have examined the dynamics, deformation and interaction of drops and bubbles in non-Newtonian fluids, and vice versa (Oishi et al. Reference Oishi, Martins, Tomé and Alves2012; Yue & Feng Reference Yue and Feng2012; Wang, Do-Quang & Amberg Reference Wang, Do-Quang and Amberg2017; Amani et al. Reference Amani, Balcázar, Castro and Oliva2019; Balasubramanian et al. Reference Balasubramanian, Sanjay, Jalaal, Vinuesa and Tammisola2024), with only a small number investigating turbulent conditions using interface-resolved simulations (Rosti & Brandt Reference Rosti and Brandt2017; Del Gaudio et al. Reference Del Gaudio, Constantinescu, Di Cristo, De Paola and Vacca2024).

We address this problem through direct numerical simulations (DNS) of a turbulent channel flow at shear Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_\tau = 300$

, driven by a constant mean pressure gradient. The domain contains a thin lubricating layer near the bottom wall, separated from the Newtonian bulk by a deformable interface governed by surface tension, with a fixed Weber number

$\textit{Re}_\tau = 300$

, driven by a constant mean pressure gradient. The domain contains a thin lubricating layer near the bottom wall, separated from the Newtonian bulk by a deformable interface governed by surface tension, with a fixed Weber number

![]() $\textit{We} = 0.5$

. All cases assume density-matched fluids to isolate rheological effects from buoyancy or inertial stratification. We consider a reference single-phase Newtonian case, alongside four two-layer configurations in which the lubricating layer exhibits increasing rheological complexity: (i) Newtonian; (ii) shear-thinning described by a Carreau model; (iii) shear-thinning and viscoelasticity combined via a FENE-P model; and (iv) purely viscoelastic behaviour modelled by FENE-CR. In all cases, the zero-shear viscosity of the lubricating layer is matched to that of the core fluid to allow meaningful comparison. Such fluids occur in real-world applications and can also be engineered by incorporating micro-structures into light oils or other fluids (Ewoldt & Saengow Reference Ewoldt and Saengow2022). In line with previous findings for Newtonian–Newtonian fluids (Roccon, Zonta & Soldati Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2019), surface tension alone contributes substantially to drag reduction. However, the presence of shear-thinning behaviour without elasticity does not significantly enhance this effect: the Carreau fluid, despite its reduced apparent viscosity near the wall, yields drag reduction levels comparable to the Newtonian case. In contrast, viscoelastic effects play a decisive role, and both FENE-P and FENE-CR fluids lead to drag reduction, highlighting the importance of the elastic component in modifying interfacial dynamics and turbulence structure.

$\textit{We} = 0.5$

. All cases assume density-matched fluids to isolate rheological effects from buoyancy or inertial stratification. We consider a reference single-phase Newtonian case, alongside four two-layer configurations in which the lubricating layer exhibits increasing rheological complexity: (i) Newtonian; (ii) shear-thinning described by a Carreau model; (iii) shear-thinning and viscoelasticity combined via a FENE-P model; and (iv) purely viscoelastic behaviour modelled by FENE-CR. In all cases, the zero-shear viscosity of the lubricating layer is matched to that of the core fluid to allow meaningful comparison. Such fluids occur in real-world applications and can also be engineered by incorporating micro-structures into light oils or other fluids (Ewoldt & Saengow Reference Ewoldt and Saengow2022). In line with previous findings for Newtonian–Newtonian fluids (Roccon, Zonta & Soldati Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2019), surface tension alone contributes substantially to drag reduction. However, the presence of shear-thinning behaviour without elasticity does not significantly enhance this effect: the Carreau fluid, despite its reduced apparent viscosity near the wall, yields drag reduction levels comparable to the Newtonian case. In contrast, viscoelastic effects play a decisive role, and both FENE-P and FENE-CR fluids lead to drag reduction, highlighting the importance of the elastic component in modifying interfacial dynamics and turbulence structure.

2. Methodology

We consider a channel flow with a main Newtonian fluid layer (thickness

![]() $1.7h$

) lubricated by a thin non-Newtonian layer (thickness

$1.7h$

) lubricated by a thin non-Newtonian layer (thickness

![]() $0.3h$

), as depicted in figure 1. The channel has dimensions

$0.3h$

), as depicted in figure 1. The channel has dimensions

![]() $L_{x} \times L_{y} \times L_{z} = 4\pi h \times 2\pi h \times 2h$

, where

$L_{x} \times L_{y} \times L_{z} = 4\pi h \times 2\pi h \times 2h$

, where

![]() $h$

is the channel half-height, and

$h$

is the channel half-height, and

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

,

$y$

,

![]() $z$

are the streamwise, spanwise and wall-normal directions, respectively. The two fluids have equal density,

$z$

are the streamwise, spanwise and wall-normal directions, respectively. The two fluids have equal density,

![]() $\rho _m = \rho _l = \rho$

, and are separated by a deformable interface characterised by a constant surface tension

$\rho _m = \rho _l = \rho$

, and are separated by a deformable interface characterised by a constant surface tension

![]() $\sigma$

. The DNS of the Navier–Stokes equations coupled with a Cahn–Hilliard equation are used to describe the dynamics of the two-phase flow (Jacqmin Reference Jacqmin1999; Roccon, Zonta & Soldati Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2023). An additional transport equation for the conformation tensor is solved when viscoelastic fluids are considered.

$\sigma$

. The DNS of the Navier–Stokes equations coupled with a Cahn–Hilliard equation are used to describe the dynamics of the two-phase flow (Jacqmin Reference Jacqmin1999; Roccon, Zonta & Soldati Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2023). An additional transport equation for the conformation tensor is solved when viscoelastic fluids are considered.

Figure 1. Sketch of the simulation set-up considered. The flow of a main Newtonian layer having nominal thickness

![]() $1.7h$

is favoured by a non-Newtonian lubricating layer having nominal thickness

$1.7h$

is favoured by a non-Newtonian lubricating layer having nominal thickness

![]() $0.3h$

. The two fluids are immiscible and separated by a deformable interface; the flow is driven by a constant pressure gradient along the streamwise direction. The case shown refers to a FENE-CR lubricating layer and the colour map (yellow for low, violet for high) shows the

$0.3h$

. The two fluids are immiscible and separated by a deformable interface; the flow is driven by a constant pressure gradient along the streamwise direction. The case shown refers to a FENE-CR lubricating layer and the colour map (yellow for low, violet for high) shows the

![]() $x{-}z$

component of the polymer stress tensor.

$x{-}z$

component of the polymer stress tensor.

2.1. Phase-field method

The phase-field method employs a diffuse-interface formulation in which the sharp boundary between immiscible fluids is replaced by a thin transition layer, across which fluid properties vary continuously. This is achieved by introducing the phase-field variable

![]() $\phi$

, which is an indicator function:

$\phi$

, which is an indicator function:

![]() $\phi = 1$

in the main layer, and

$\phi = 1$

in the main layer, and

![]() $\phi = -1$

in the lubricating layer. The fluid interface is then represented by the region where

$\phi = -1$

in the lubricating layer. The fluid interface is then represented by the region where

![]() $\phi$

varies smoothly between these two values. The distribution and dynamics of

$\phi$

varies smoothly between these two values. The distribution and dynamics of

![]() $\phi$

are governed by the dimensionless Cahn–Hilliard equation:

$\phi$

are governed by the dimensionless Cahn–Hilliard equation:

where

![]() $\textit{Pe} = u_\tau h/\mathcal{M}\beta$

is the Péclet number, i.e. the ratio between the convective and diffusive time scales of the interface. Here,

$\textit{Pe} = u_\tau h/\mathcal{M}\beta$

is the Péclet number, i.e. the ratio between the convective and diffusive time scales of the interface. Here,

![]() $u_\tau$

denotes the friction velocity,

$u_\tau$

denotes the friction velocity,

![]() $h$

is the channel half-height,

$h$

is the channel half-height,

![]() $\mathcal{M}$

is the mobility, and

$\mathcal{M}$

is the mobility, and

![]() $\beta$

is a positive constant. The chemical potential

$\beta$

is a positive constant. The chemical potential

![]() $\mu _{\phi }$

is defined as the variational derivative of a Ginzburg–Landau free-energy functional:

$\mu _{\phi }$

is defined as the variational derivative of a Ginzburg–Landau free-energy functional:

We consider a system composed by two immiscible fluids, one of which is viscoelastic. The corresponding Ginzburg–Landau free-energy functional can be expressed as the sum of three different contributions, namely a bulk term, an interfacial (or mixing) term, and an elastic contribution (Yue et al. Reference Yue, Feng, Liu and Shen2004):

with

where

![]() $f_0$

represents the bulk free energy driving phase separation,

$f_0$

represents the bulk free energy driving phase separation,

![]() $f_{\textit{mix}}$

accounts for the interfacial energy, which is proportional to the Cahn number

$f_{\textit{mix}}$

accounts for the interfacial energy, which is proportional to the Cahn number

![]() $\textit{Ch}=\xi /h$

(ratio of interface thickness

$\textit{Ch}=\xi /h$

(ratio of interface thickness

![]() $\xi$

to channel half-height

$\xi$

to channel half-height

![]() $h$

), and

$h$

), and

![]() $f_e$

models the elastic contribution associated with polymer deformation. Here,

$f_e$

models the elastic contribution associated with polymer deformation. Here,

![]() $\psi$

denotes the normalised probability distribution function of the polymer end-to-end vector

$\psi$

denotes the normalised probability distribution function of the polymer end-to-end vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{q}$

(i.e.

$\boldsymbol{q}$

(i.e.

![]() $\int _{\mathbb{R}^3} \psi \, \textrm{d}\boldsymbol{q} =1$

) (Bird, Armstrong & Hassager Reference Bird, Armstrong and Hassager1987). The phase-field formulation implicitly captures topological changes of the interface, such as rupture events, while preserving smooth transitions. From (2.2), the chemical potential is obtained as

$\int _{\mathbb{R}^3} \psi \, \textrm{d}\boldsymbol{q} =1$

) (Bird, Armstrong & Hassager Reference Bird, Armstrong and Hassager1987). The phase-field formulation implicitly captures topological changes of the interface, such as rupture events, while preserving smooth transitions. From (2.2), the chemical potential is obtained as

Following Yue et al. (Reference Yue, Feng, Liu and Shen2004, Reference Yue, Feng, Liu and Shen2005), the elastic contribution

![]() $\delta f_e/\delta \phi$

becomes negligible in the sharp-interface limit. The governing Cahn–Hilliard equation then reduces to

$\delta f_e/\delta \phi$

becomes negligible in the sharp-interface limit. The governing Cahn–Hilliard equation then reduces to

2.2. Hydrodynamics

To describe the hydrodynamics of the two-phase system, the Cahn–Hilliard equation is coupled with the Navier–Stokes equations within the one-fluid formulation (Prosperetti & Tryggvason Reference Prosperetti and Tryggvason2007). The presence of a deformable interface is accounted for by an additional source term representing surface tension forces. This formulation ensures continuity of velocity and stresses across the interface (Landau & Lifshitz Reference Landau and Lifshitz1987; Panton Reference Panton2013). The resulting dimensionless governing equations read as

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{u}=(u,v,w)$

is the velocity vector and

$\boldsymbol{u}=(u,v,w)$

is the velocity vector and

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} p$

is the pressure gradient. The last term in (2.10) represents the contribution of the surface tension forces where the corresponding stress tensor is defined as

$\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} p$

is the pressure gradient. The last term in (2.10) represents the contribution of the surface tension forces where the corresponding stress tensor is defined as

![]() $\boldsymbol{\tau }_c=|\boldsymbol{\nabla }\phi |^2 \boldsymbol{I} - \boldsymbol{\nabla }\phi \otimes \boldsymbol{\nabla }\phi$

, in accordance with the Korteweg formulation (Korteweg Reference Korteweg1901). The dimensionless parameters are the shear Reynolds number

$\boldsymbol{\tau }_c=|\boldsymbol{\nabla }\phi |^2 \boldsymbol{I} - \boldsymbol{\nabla }\phi \otimes \boldsymbol{\nabla }\phi$

, in accordance with the Korteweg formulation (Korteweg Reference Korteweg1901). The dimensionless parameters are the shear Reynolds number

![]() $\textit{Re}_{\tau }= \rho u_\tau h/\mu _m$

, based on the Newtonian fluid viscosity, and the Weber number

$\textit{Re}_{\tau }= \rho u_\tau h/\mu _m$

, based on the Newtonian fluid viscosity, and the Weber number

![]() $\textit{We}=\rho u^2_\tau h /\sigma$

, i.e. the ratio between inertial and surface tension forces.

$\textit{We}=\rho u^2_\tau h /\sigma$

, i.e. the ratio between inertial and surface tension forces.

2.3. Non-Newtonian rheology

The rheological behaviour of the lubricating layer is controlled by the constitutive stress tensor,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\tau }_k$

. In addition to a reference Newtonian lubricating layer, we consider the following non-Newtonian models: (i) Carreau model, representative of a shear-thinning fluid; (ii) FENE-P model, a viscoelastic and shear-thinning fluid; and (iii) FENE-CR model, a viscoelastic fluid characterised by uniform viscosity. Hence for the different cases considered, the constitutive stress tensor

$\boldsymbol{\tau }_k$

. In addition to a reference Newtonian lubricating layer, we consider the following non-Newtonian models: (i) Carreau model, representative of a shear-thinning fluid; (ii) FENE-P model, a viscoelastic and shear-thinning fluid; and (iii) FENE-CR model, a viscoelastic fluid characterised by uniform viscosity. Hence for the different cases considered, the constitutive stress tensor

![]() $\boldsymbol{\tau }_k$

is defined as

$\boldsymbol{\tau }_k$

is defined as

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{\tau }_k = \begin{cases} \left (\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u}^{\mathrm{T}}\right ), & \text{Newtonian},\\[6pt] \left (1+\dfrac {1-\phi}{2}\left (\beta ( \dot {\gamma }) - 1\right )\right ) \left (\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u}^{\mathrm{T}}\right ), & \text{Carreau},\\[6pt] x_0 \left (1+\dfrac {(1/x_0-1)(\phi +1)}{2}\right ) \left (\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u}^{\mathrm{T}}\right ) + (1-x_0)\, \boldsymbol{\tau }_{\!p}, & \text{FENE-P and FENE-CR}. \end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \boldsymbol{\tau }_k = \begin{cases} \left (\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u}^{\mathrm{T}}\right ), & \text{Newtonian},\\[6pt] \left (1+\dfrac {1-\phi}{2}\left (\beta ( \dot {\gamma }) - 1\right )\right ) \left (\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u}^{\mathrm{T}}\right ), & \text{Carreau},\\[6pt] x_0 \left (1+\dfrac {(1/x_0-1)(\phi +1)}{2}\right ) \left (\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u}^{\mathrm{T}}\right ) + (1-x_0)\, \boldsymbol{\tau }_{\!p}, & \text{FENE-P and FENE-CR}. \end{cases} \end{equation}

For the shear-thinning Carreau model (Carreau Reference Carreau1972), the effective non-dimensional viscosity is expressed through the relation

where

![]() $\mu _\infty /\mu _0$

is the infinite-strain to zero-strain viscosity ratio,

$\mu _\infty /\mu _0$

is the infinite-strain to zero-strain viscosity ratio,

![]() $\mathit{Cu} = \varLambda u_\tau / h$

is the Carreau number, with

$\mathit{Cu} = \varLambda u_\tau / h$

is the Carreau number, with

![]() $\varLambda$

the fluid characteristic time scale,

$\varLambda$

the fluid characteristic time scale,

![]() $n$

is the flow behaviour index, and

$n$

is the flow behaviour index, and

![]() $\dot {\gamma }$

is the strain rate. The latter is defined as

$\dot {\gamma }$

is the strain rate. The latter is defined as

![]() $\dot {\gamma } = \sqrt {2\, \boldsymbol{S}\boldsymbol{S}}$

, with

$\dot {\gamma } = \sqrt {2\, \boldsymbol{S}\boldsymbol{S}}$

, with

![]() $\boldsymbol{S} = 1/2 (\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u}^{{\rm T}} )$

.

$\boldsymbol{S} = 1/2 (\boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u} + \boldsymbol{\nabla \!} \boldsymbol{u}^{{\rm T}} )$

.

For the viscoelastic cases (FENE-P and FENE-CR), the viscosity ratio

![]() $x_0 = \mu _s/(\mu _s + \mu _p)$

quantifies the solvent contribution to the total zero-strain viscosity

$x_0 = \mu _s/(\mu _s + \mu _p)$

quantifies the solvent contribution to the total zero-strain viscosity

![]() $\mu _0 = \mu _s+\mu _p=\mu _m$

, and has been set equal to the top Newtonian layer. The polymer stress tensor is defined as

$\mu _0 = \mu _s+\mu _p=\mu _m$

, and has been set equal to the top Newtonian layer. The polymer stress tensor is defined as

where

![]() $\mathit{Wi}_\tau = \rho \lambda u^2_\tau /\mu _0$

is the shear Weissenberg number, while

$\mathit{Wi}_\tau = \rho \lambda u^2_\tau /\mu _0$

is the shear Weissenberg number, while

![]() $\textit{Wi}= \mathit{Wi}_\tau /\textit{Re}_\tau$

is the Weissenberg number (coincident with the Deborah number), i.e. the ratio of elastic to flow time scale, and

$\textit{Wi}= \mathit{Wi}_\tau /\textit{Re}_\tau$

is the Weissenberg number (coincident with the Deborah number), i.e. the ratio of elastic to flow time scale, and

![]() $\lambda$

is the polymer relaxation time. The conformation tensor

$\lambda$

is the polymer relaxation time. The conformation tensor

![]() $\boldsymbol{C}$

describes the polymer microstructure and is described by the equation (Alves, Oliveira & Pinho Reference Alves, Oliveira and Pinho2021)

$\boldsymbol{C}$

describes the polymer microstructure and is described by the equation (Alves, Oliveira & Pinho Reference Alves, Oliveira and Pinho2021)

where

![]() $\mathit{Sc}_p = \mu _0/(\rho k)$

is the Schmidt number controlling the magnitude of the diffusive regularisation term for the polymer. The finite polymer extensibility is captured by

$\mathit{Sc}_p = \mu _0/(\rho k)$

is the Schmidt number controlling the magnitude of the diffusive regularisation term for the polymer. The finite polymer extensibility is captured by

![]() $f(\boldsymbol{C})=L^2/(L^2-\mathrm{tr}(\boldsymbol{C}))$

, with

$f(\boldsymbol{C})=L^2/(L^2-\mathrm{tr}(\boldsymbol{C}))$

, with

![]() $L$

the extensibility limit. The choice of

$L$

the extensibility limit. The choice of

![]() $g(\boldsymbol{C})$

distinguishes the models:

$g(\boldsymbol{C})$

distinguishes the models:

![]() $g=1$

gives the FENE-P model, which accounts also for shear-thinning effects (Bird et al. Reference Bird, Armstrong and Hassager1987), while

$g=1$

gives the FENE-P model, which accounts also for shear-thinning effects (Bird et al. Reference Bird, Armstrong and Hassager1987), while

![]() $g=f(\boldsymbol{C})$

yields the purely viscoelastic FENE-CR model (Chilcott & Rallison Reference Chilcott and Rallison1988). Notably, the formulation employed here ensures a consistent transition between different rheological behaviours. In the Newtonian region (

$g=f(\boldsymbol{C})$

yields the purely viscoelastic FENE-CR model (Chilcott & Rallison Reference Chilcott and Rallison1988). Notably, the formulation employed here ensures a consistent transition between different rheological behaviours. In the Newtonian region (

![]() $\phi \to 1$

), the effective Weissenberg number

$\phi \to 1$

), the effective Weissenberg number

![]() $\mathit{Wi}(\phi )=(1-\phi )/2\, \textit{Wi}$

tends to zero, the relaxation term vanishes, and the conformation tensor reduces to

$\mathit{Wi}(\phi )=(1-\phi )/2\, \textit{Wi}$

tends to zero, the relaxation term vanishes, and the conformation tensor reduces to

![]() $\boldsymbol{C} \approx \boldsymbol{I}$

. The polymer stress contribution therefore becomes negligible, and the standard Navier–Stokes equations are recovered. In contrast, in the viscoelastic region (

$\boldsymbol{C} \approx \boldsymbol{I}$

. The polymer stress contribution therefore becomes negligible, and the standard Navier–Stokes equations are recovered. In contrast, in the viscoelastic region (

![]() $\phi \to -1$

), the full polymer stress is active, introducing both elasticity and shear-thinning effects, depending on the chosen closure.

$\phi \to -1$

), the full polymer stress is active, introducing both elasticity and shear-thinning effects, depending on the chosen closure.

2.4. Numerical method

The governing equations (2.8), (2.9), (2.10) and (2.14) are solved using FLOW36, an open-source GPU-ready spectral solver (Roccon, Soligo & Soldati Reference Roccon, Soligo and Soldati2025). Spatial discretisation relies on Fourier expansions in the two homogeneous directions (

![]() $x$

,

$x$

,

![]() $y$

) and Chebyshev polynomials in the wall-normal direction (

$y$

) and Chebyshev polynomials in the wall-normal direction (

![]() $z$

).

$z$

).

The Navier–Stokes equations are solved in the wall-normal velocity–vorticity formulation (Kim, Moin & Moser Reference Kim, Moin and Moser1987; Speziale Reference Speziale1987), which yields a fourth-order equation for the wall-normal velocity

![]() $w$

, and a second-order equation for the wall-normal vorticity

$w$

, and a second-order equation for the wall-normal vorticity

![]() $\omega _z$

. The phase-field equation (2.8) is reformulated as two coupled second-order equations (Badalassi, Ceniceros & Banerjee Reference Badalassi, Ceniceros and Banerjee2003). Time advancement of both the momentum and phase-field equations employs an implicit–explicit scheme (Moin & Kim Reference Moin and Kim1980): linear terms are integrated implicitly (Crank–Nicolson for the Navier–Stokes equations, backward Euler for the phase-field; Yue et al. Reference Yue, Feng, Liu and Shen2004), while nonlinear terms are treated explicitly using a second-order Adams–Bashforth method.

$\omega _z$

. The phase-field equation (2.8) is reformulated as two coupled second-order equations (Badalassi, Ceniceros & Banerjee Reference Badalassi, Ceniceros and Banerjee2003). Time advancement of both the momentum and phase-field equations employs an implicit–explicit scheme (Moin & Kim Reference Moin and Kim1980): linear terms are integrated implicitly (Crank–Nicolson for the Navier–Stokes equations, backward Euler for the phase-field; Yue et al. Reference Yue, Feng, Liu and Shen2004), while nonlinear terms are treated explicitly using a second-order Adams–Bashforth method.

For viscoelastic simulations (FENE-P, FENE-CR), the conformation tensor equation is advanced in time simultaneously with the momentum and phase-field equations. The numerical treatment of the conformation tensor is particularly delicate, as the loss of positive-definiteness and the development of steep polymer stress gradients near the walls may trigger numerical instabilities. To alleviate these issues, a diffusive regularisation term for the polymer

![]() $(\mathit{Re}_{\tau }\, \mathit{\textit{Sc}_{\!p}})^{-1}\, {\nabla} ^2 \boldsymbol{C}$

is introduced following standard practice in pseudo-spectral simulations (Sureshkumar, Beris & Handler Reference Sureshkumar, Beris and Handler1997; Dimitropoulos, Sureshkumar & Beris Reference Dimitropoulos, Sureshkumar and Beris1998; Xi & Graham Reference Xi and Graham2010). The diffusive contribution in the conformation tensor equation is discretised implicitly via a Crank–Nicolson scheme, while the nonlinear terms are advanced explicitly with a second-order Adams–Bashforth scheme. To ensure the boundedness of the conformation tensor

$(\mathit{Re}_{\tau }\, \mathit{\textit{Sc}_{\!p}})^{-1}\, {\nabla} ^2 \boldsymbol{C}$

is introduced following standard practice in pseudo-spectral simulations (Sureshkumar, Beris & Handler Reference Sureshkumar, Beris and Handler1997; Dimitropoulos, Sureshkumar & Beris Reference Dimitropoulos, Sureshkumar and Beris1998; Xi & Graham Reference Xi and Graham2010). The diffusive contribution in the conformation tensor equation is discretised implicitly via a Crank–Nicolson scheme, while the nonlinear terms are advanced explicitly with a second-order Adams–Bashforth scheme. To ensure the boundedness of the conformation tensor

![]() $\boldsymbol{C}$

, i.e.

$\boldsymbol{C}$

, i.e.

![]() $\operatorname {tr}(\boldsymbol{C}) \lt L^2$

, we adopt the stabilisation technique proposed by Vaithianathan & Collins (Reference Vaithianathan and Collins2003) and later refined by Dubief et al. (Reference Dubief, Terrapon, White, Shaqfeh, Moin and Lele2005) and Richter, Iaccarino & Shaqfeh (Reference Richter, Iaccarino and Shaqfeh2010). This method enforces the boundedness of

$\operatorname {tr}(\boldsymbol{C}) \lt L^2$

, we adopt the stabilisation technique proposed by Vaithianathan & Collins (Reference Vaithianathan and Collins2003) and later refined by Dubief et al. (Reference Dubief, Terrapon, White, Shaqfeh, Moin and Lele2005) and Richter, Iaccarino & Shaqfeh (Reference Richter, Iaccarino and Shaqfeh2010). This method enforces the boundedness of

![]() $\operatorname {tr}(\boldsymbol{C})$

by evolving an auxiliary variable

$\operatorname {tr}(\boldsymbol{C})$

by evolving an auxiliary variable

![]() $f^{-1} = 1 - \operatorname {tr}(\boldsymbol{C})/L^2$

for the FENE-P model (or

$f^{-1} = 1 - \operatorname {tr}(\boldsymbol{C})/L^2$

for the FENE-P model (or

![]() $f$

in the FENE-CR case) instead of

$f$

in the FENE-CR case) instead of

![]() $\boldsymbol{C}$

directly. In both formulations, the resulting value of

$\boldsymbol{C}$

directly. In both formulations, the resulting value of

![]() $f^{-1}$

(or

$f^{-1}$

(or

![]() $f$

) is held fixed while the nonlinear terms of conformation tensor

$f$

) is held fixed while the nonlinear terms of conformation tensor

![]() $\boldsymbol{C}$

are computed, ensuring that

$\boldsymbol{C}$

are computed, ensuring that

![]() $\operatorname {tr}(\boldsymbol{C}) \leqslant L^2$

at all times, and maintaining numerical stability.

$\operatorname {tr}(\boldsymbol{C}) \leqslant L^2$

at all times, and maintaining numerical stability.

2.5. Boundary conditions

Periodic boundary conditions are applied along the two homogeneous directions (

![]() $x$

and

$x$

and

![]() $y$

), where Fourier transforms are employed. At the walls (

$y$

), where Fourier transforms are employed. At the walls (

![]() $z/h = \pm 1$

), no-slip boundary conditions are enforced for the velocity field:

$z/h = \pm 1$

), no-slip boundary conditions are enforced for the velocity field:

Using the wall-normal velocity–vorticity formulation, the corresponding conditions for the wall-normal velocity

![]() $w$

and vorticity

$w$

and vorticity

![]() $\omega _z$

can be derived by combining the no-slip condition with the continuity equation. Specifically, for the wall-normal velocity we have

$\omega _z$

can be derived by combining the no-slip condition with the continuity equation. Specifically, for the wall-normal velocity we have

and for the wall-normal vorticity we have

The Cahn–Hilliard equation is solved by imposing no-flux conditions for the phase-field variable and the chemical potential at the two walls:

From a mathematical point of view, this is equivalent to imposing the boundary conditions (Jacqmin Reference Jacqmin1999; Yue et al. Reference Yue, Feng, Liu and Shen2004)

These conditions ensure global conservation of the phase field:

where

![]() $\varOmega$

is the computational domain. While this guarantees mass conservation of the entire system, it does not strictly enforce mass conservation of each phase (

$\varOmega$

is the computational domain. While this guarantees mass conservation of the entire system, it does not strictly enforce mass conservation of each phase (

![]() $\phi = +1$

and

$\phi = +1$

and

![]() $\phi = -1$

), and small leakages between phases may occur (Yue, Zhou & Feng Reference Yue, Zhou and Feng2007; Soligo, Roccon & Soldati Reference Soligo, Roccon and Soldati2019). In the present simulations, mass leakage is always below 1 %. For the conformation tensor, the boundary conditions are set according to the rheological properties of the respective layer. At the top wall (

$\phi = -1$

), and small leakages between phases may occur (Yue, Zhou & Feng Reference Yue, Zhou and Feng2007; Soligo, Roccon & Soldati Reference Soligo, Roccon and Soldati2019). In the present simulations, mass leakage is always below 1 %. For the conformation tensor, the boundary conditions are set according to the rheological properties of the respective layer. At the top wall (

![]() $z/h=1$

), where the fluid is Newtonian, a Dirichlet condition corresponding to the coiled state of the polymers is imposed:

$z/h=1$

), where the fluid is Newtonian, a Dirichlet condition corresponding to the coiled state of the polymers is imposed:

At the bottom wall (

![]() $z/h=-1$

), when a viscoelastic fluid layer is present (FENE-P or FENE-CR), zero artificial diffusivity is assumed (

$z/h=-1$

), when a viscoelastic fluid layer is present (FENE-P or FENE-CR), zero artificial diffusivity is assumed (

![]() $Sc \to \infty$

), making the conformation tensor equation explicit at the wall (Dimitropoulos et al. Reference Dimitropoulos, Sureshkumar and Beris1998):

$Sc \to \infty$

), making the conformation tensor equation explicit at the wall (Dimitropoulos et al. Reference Dimitropoulos, Sureshkumar and Beris1998):

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{S}_c$

contains all nonlinear terms of the conformation tensor transport (2.14). This treatment ensures that the conformation tensor and the associated polymeric stress naturally follow the interface evolution and remain confined to the respective fluid layer.

$\boldsymbol{S}_c$

contains all nonlinear terms of the conformation tensor transport (2.14). This treatment ensures that the conformation tensor and the associated polymeric stress naturally follow the interface evolution and remain confined to the respective fluid layer.

2.6. Simulation set-up

We perform five sets of DNS of a turbulent channel flow. First, a precursor single-phase (SP) simulation at

![]() $\textit{Re}_\tau = 300$

is executed to reach a statistically steady state. The resulting flow field is then used to initialise the Newtonian simulation. All multiphase simulations are subsequently initialised from this stratified Newtonian configuration. The time step is maintained at

$\textit{Re}_\tau = 300$

is executed to reach a statistically steady state. The resulting flow field is then used to initialise the Newtonian simulation. All multiphase simulations are subsequently initialised from this stratified Newtonian configuration. The time step is maintained at

![]() $\Delta t^- = 0.25 \times 10^{-4}$

for all simulations.

$\Delta t^- = 0.25 \times 10^{-4}$

for all simulations.

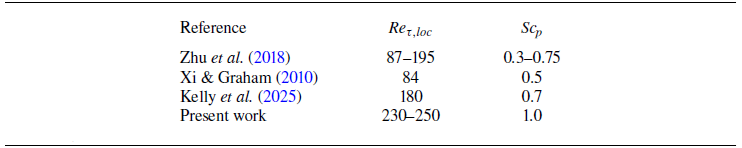

The multiphase cases consider a main Newtonian layer above a thin lubricating layer, as illustrated in figure 1. The lubricating layer exhibits different rheological behaviour in each simulation: Newtonian, shear-thinning (Carreau model), viscoelastic and shear-thinning (FENE-P model), and purely viscoelastic (FENE-CR model). In all viscoelastic simulations, the Schmidt number is set to

![]() $\textit{Sc}_{\!p} = 1$

, chosen as a compromise to stabilise the numerical solution of the conformation tensor without significantly compromising physical fidelity (Sureshkumar & Beris Reference Sureshkumar and Beris1995). The chosen Schmidt number conforms to previous numerical studies (Xi & Graham Reference Xi and Graham2010; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Schrobsdorff, Schneider and Xi2018; Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Goldstein, Burtsev, Suryanarayanan, Handler and Sonmez2025), and a sensitivity analysis of its effect is reported in Appendix A. For both viscoelastic simulations, the Weissenberg number is set to

$\textit{Sc}_{\!p} = 1$

, chosen as a compromise to stabilise the numerical solution of the conformation tensor without significantly compromising physical fidelity (Sureshkumar & Beris Reference Sureshkumar and Beris1995). The chosen Schmidt number conforms to previous numerical studies (Xi & Graham Reference Xi and Graham2010; Zhu et al. Reference Zhu, Schrobsdorff, Schneider and Xi2018; Kelly et al. Reference Kelly, Goldstein, Burtsev, Suryanarayanan, Handler and Sonmez2025), and a sensitivity analysis of its effect is reported in Appendix A. For both viscoelastic simulations, the Weissenberg number is set to

![]() $\mathit{Wi}_\tau = 50$

, and the viscosity ratio is set to

$\mathit{Wi}_\tau = 50$

, and the viscosity ratio is set to

![]() $x_0 = 0.9$

. In all cases, the zero-strain-rate viscosity of the lubricating layer is matched to that of the Newtonian upper layer,

$x_0 = 0.9$

. In all cases, the zero-strain-rate viscosity of the lubricating layer is matched to that of the Newtonian upper layer,

![]() $\mu _0 = \mu _m$

. The Carreau model parameters are tuned to reproduce the same degree of shear-thinning observed in the FENE-P simulation at

$\mu _0 = \mu _m$

. The Carreau model parameters are tuned to reproduce the same degree of shear-thinning observed in the FENE-P simulation at

![]() $\mathit{Wi}_\tau = 50$

and

$\mathit{Wi}_\tau = 50$

and

![]() $L = 30$

, using the known rheological response

$L = 30$

, using the known rheological response

![]() $\mu _l/\mu _0(\dot {\gamma }, x_0, \mathit{Wi}, L)$

as a reference (Tamano et al. Reference Tamano, Itoh, Hotta, Yokota and Morinishi2009), yielding

$\mu _l/\mu _0(\dot {\gamma }, x_0, \mathit{Wi}, L)$

as a reference (Tamano et al. Reference Tamano, Itoh, Hotta, Yokota and Morinishi2009), yielding

![]() $\mu _\infty /\mu _0 = 0.9$

,

$\mu _\infty /\mu _0 = 0.9$

,

![]() $\mathit{Cu} = 4$

and

$\mathit{Cu} = 4$

and

![]() $n = 0.45$

.

$n = 0.45$

.

For the SP, Newtonian and Carreau cases, a grid of

![]() $512 \times 256 \times 257$

points is used, whereas the viscoelastic simulations employ a finer grid of

$512 \times 256 \times 257$

points is used, whereas the viscoelastic simulations employ a finer grid of

![]() $512 \times 512 \times 513$

points to ensure numerical stability. To verify that this resolution is sufficient for the viscoelastic cases, we also performed additional simulations using a grid refined by a factor of 2 in all directions, and observed no appreciable differences. The surface tension of the liquid–liquid interface is constant for all cases and set via the Weber number

$512 \times 512 \times 513$

points to ensure numerical stability. To verify that this resolution is sufficient for the viscoelastic cases, we also performed additional simulations using a grid refined by a factor of 2 in all directions, and observed no appreciable differences. The surface tension of the liquid–liquid interface is constant for all cases and set via the Weber number

![]() $\textit{We} = 0.5$

. This value is consistent with our previous multiphase DNS database, and ensures that the interface remains compliant yet stable under turbulent forcing, in line with earlier studies on drag-reduced flows (Roccon et al. Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2019, Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2021, Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2024). The Cahn number is set to

$\textit{We} = 0.5$

. This value is consistent with our previous multiphase DNS database, and ensures that the interface remains compliant yet stable under turbulent forcing, in line with earlier studies on drag-reduced flows (Roccon et al. Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2019, Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2021, Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2024). The Cahn number is set to

![]() $\textit{Ch} = 0.02$

, and the Péclet number is computed as

$\textit{Ch} = 0.02$

, and the Péclet number is computed as

![]() $\textit{Pe} = 3/\textit{Ch}$

(Magaletti et al. Reference Magaletti, Picano, Chinappi, Marino and Casciola2013) to achieve asymptotic convergence to the sharp-interface limit. The interface is initially flat and located at

$\textit{Pe} = 3/\textit{Ch}$

(Magaletti et al. Reference Magaletti, Picano, Chinappi, Marino and Casciola2013) to achieve asymptotic convergence to the sharp-interface limit. The interface is initially flat and located at

![]() $h_l = 0.3h$

from the bottom wall. Specifically, the initial phase-field condition is

$h_l = 0.3h$

from the bottom wall. Specifically, the initial phase-field condition is

On the other hand, viscoelastic simulations are initialised with zero polymer stress,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\tau }_{\!p}=0$

, i.e.

$\boldsymbol{\tau }_{\!p}=0$

, i.e.

![]() $\boldsymbol{C}= \boldsymbol{I}$

in the entire domain. Given the prescribed boundaries condition on the conformation tensor, and because advective or stretching contributions in the Newtonian region do not develop due to the mild gradients of the conformation tensor, the latter remains constant over time.

$\boldsymbol{C}= \boldsymbol{I}$

in the entire domain. Given the prescribed boundaries condition on the conformation tensor, and because advective or stretching contributions in the Newtonian region do not develop due to the mild gradients of the conformation tensor, the latter remains constant over time.

3. Results

The drag reduction performance obtained from the different cases is first evaluated by looking at macroscopic flow parameters. Then the mean shear stress budget is used to obtain useful insights on the mechanisms leading to drag reduction, and in particular on the interplay between capillary action, shear-thinning and viscoelasticity. The statistics presented below have been computed once a new statistically steady-state configuration is attained for all configurations. All simulations exhibit an initial transient, whose duration depends on the specific case considered, where the flow adapts to the rheological properties of the lubricating layer. Once this new steady-state configuration is attained, statistics are computed using time window

![]() $\Delta t^+ = 4000$

.

$\Delta t^+ = 4000$

.

3.1. Mean flow and rheological features

Figure 2(

![]() $a$

) shows the rheology map of the lubricating fluids employed, where the dimensionless viscosity

$a$

) shows the rheology map of the lubricating fluids employed, where the dimensionless viscosity

![]() $\mu _l(\dot {\gamma })/\mu _0$

is shown as a function of the strain rate

$\mu _l(\dot {\gamma })/\mu _0$

is shown as a function of the strain rate

![]() $\dot {\gamma }$

. The shear-thinning region – where viscosity decreases with increasing strain rate – is the shaded grey area. The Carreau (green solid line) and FENE-P (green dashed line) models have the same zero strain rate viscosity

$\dot {\gamma }$

. The shear-thinning region – where viscosity decreases with increasing strain rate – is the shaded grey area. The Carreau (green solid line) and FENE-P (green dashed line) models have the same zero strain rate viscosity

![]() $\mu _0$

, and exhibit identical shear-thinning behaviour, asymptotically approaching a viscosity plateau

$\mu _0$

, and exhibit identical shear-thinning behaviour, asymptotically approaching a viscosity plateau

![]() $\mu (\dot {\gamma })/\mu _0 \approx 0.9$

at high strain rates. In contrast, the FENE-CR model (purple dashed line) maintains a constant viscosity over the entire strain-rate range, overlapping with the Newtonian reference (purple solid line), thus isolating the effects of viscoelasticity from those of shear-thinning. On the other hand, viscoelasticity – the ability of a fluid to exhibit both viscous and elastic behaviour under deformation – stems from the polymer stress contribution. This represents the memory effect of polymer chains, which store and release elastic energy depending on whether they are stretched or relaxed (Xi Reference Xi2019).

$\mu (\dot {\gamma })/\mu _0 \approx 0.9$

at high strain rates. In contrast, the FENE-CR model (purple dashed line) maintains a constant viscosity over the entire strain-rate range, overlapping with the Newtonian reference (purple solid line), thus isolating the effects of viscoelasticity from those of shear-thinning. On the other hand, viscoelasticity – the ability of a fluid to exhibit both viscous and elastic behaviour under deformation – stems from the polymer stress contribution. This represents the memory effect of polymer chains, which store and release elastic energy depending on whether they are stretched or relaxed (Xi Reference Xi2019).

Figure 2. (

![]() $a$

) The rheology map of the different lubricating fluids. The dimensionless viscosity

$a$

) The rheology map of the different lubricating fluids. The dimensionless viscosity

![]() $ \mu _l(\dot {\gamma }) / \mu _{0}$

, with zero-strain viscosity

$ \mu _l(\dot {\gamma }) / \mu _{0}$

, with zero-strain viscosity

![]() $\mu _0$

set constant among all cases, is reported as a function of the strain rate

$\mu _0$

set constant among all cases, is reported as a function of the strain rate

![]() $\dot {\gamma }$

. Carreau and FENE-P models exhibit the same shear-thinning behaviour (green). (

$\dot {\gamma }$

. Carreau and FENE-P models exhibit the same shear-thinning behaviour (green). (

![]() $b$

) The mean velocity profiles along the wall-normal direction. The nominal position of the interface (

$b$

) The mean velocity profiles along the wall-normal direction. The nominal position of the interface (

![]() $z/h=-0.7$

) is highlighted using a grey dashed line. The inset illustrates the resulting mean viscosity distribution

$z/h=-0.7$

) is highlighted using a grey dashed line. The inset illustrates the resulting mean viscosity distribution

![]() $\overline {\mu }/\mu _0$

along the wall-normal direction near the non-Newtonian lubricating layer.

$\overline {\mu }/\mu _0$

along the wall-normal direction near the non-Newtonian lubricating layer.

Figure 2(

![]() $b$

) shows the mean streamwise velocity profiles

$b$

) shows the mean streamwise velocity profiles

![]() $\overline {u}$

as a function of the wall-normal coordinate. For the SP case, the velocity profile is symmetric, whereas in the multiphase configurations, the introduction of a lubricating layer, whose nominal position is indicated by the grey dashed line at

$\overline {u}$

as a function of the wall-normal coordinate. For the SP case, the velocity profile is symmetric, whereas in the multiphase configurations, the introduction of a lubricating layer, whose nominal position is indicated by the grey dashed line at

![]() $z/h=-0.7$

, breaks this symmetry, promoting an overall increase in mean flow velocity, especially in the main layer. The extent of this enhancement, however, depends on the rheological properties of the lubricating layer. For the Newtonian case, we observe an increase of the velocity in the main layer, with values larger than the SP case as well as an increase of the derivative of the mean velocity near the top wall. In contrast, close to the bottom wall, the derivative is smaller, with respect to the SP case. For the Carreau case (green solid line), the introduction of a shear-thinning behaviour induces only marginal changes compared to the Newtonian configuration. This suggests that shear-thinning alone has a limited influence on the mean flow. In contrast, the addition of viscoelasticity (dashed lines, FENE-P and FENE-CR cases) leads to a substantial increase in mean velocity. This increase is particularly pronounced in the main layer, and can be traced back to the presence of viscoelastic turbulence in the lubricating layer. This enhancement is purely due to viscoelastic effects: comparing FENE-P (viscoelastic shear-thinning) and FENE-CR (pure viscoelastic), no differences are visible. To better evaluate the role played by shear-thinning phenomena, we analyse the inset of figure 2(

$z/h=-0.7$

, breaks this symmetry, promoting an overall increase in mean flow velocity, especially in the main layer. The extent of this enhancement, however, depends on the rheological properties of the lubricating layer. For the Newtonian case, we observe an increase of the velocity in the main layer, with values larger than the SP case as well as an increase of the derivative of the mean velocity near the top wall. In contrast, close to the bottom wall, the derivative is smaller, with respect to the SP case. For the Carreau case (green solid line), the introduction of a shear-thinning behaviour induces only marginal changes compared to the Newtonian configuration. This suggests that shear-thinning alone has a limited influence on the mean flow. In contrast, the addition of viscoelasticity (dashed lines, FENE-P and FENE-CR cases) leads to a substantial increase in mean velocity. This increase is particularly pronounced in the main layer, and can be traced back to the presence of viscoelastic turbulence in the lubricating layer. This enhancement is purely due to viscoelastic effects: comparing FENE-P (viscoelastic shear-thinning) and FENE-CR (pure viscoelastic), no differences are visible. To better evaluate the role played by shear-thinning phenomena, we analyse the inset of figure 2(

![]() $b$

), which shows the normalised mean viscosity distribution

$b$

), which shows the normalised mean viscosity distribution

![]() $\overline {\mu }/\mu _0$

along the wall-normal direction, highlighting its dependence on the chosen rheology and local flow field. In the shear-thinning cases, the viscosity progressively decreases from the Newtonian bulk value

$\overline {\mu }/\mu _0$

along the wall-normal direction, highlighting its dependence on the chosen rheology and local flow field. In the shear-thinning cases, the viscosity progressively decreases from the Newtonian bulk value

![]() $\mu _m=\mu _0$

, with the Carreau and FENE-P models achieving approximately a

$\mu _m=\mu _0$

, with the Carreau and FENE-P models achieving approximately a

![]() $10\,\%$

reduction at the bottom wall, as they share the same rheology map. This behaviour reflects the mean velocity profile behaviour: higher shear rates near the wall lead to a smaller viscosity. This reduction is rather steep across the interfacial region (

$10\,\%$

reduction at the bottom wall, as they share the same rheology map. This behaviour reflects the mean velocity profile behaviour: higher shear rates near the wall lead to a smaller viscosity. This reduction is rather steep across the interfacial region (

![]() $-0.65 \lt z/h \lt -0.75$

), while moving towards the bottom wall (

$-0.65 \lt z/h \lt -0.75$

), while moving towards the bottom wall (

![]() $z/h \gt -0.75$

), the viscosity profile gradually flattens, reaching a near-constant value of approximately

$z/h \gt -0.75$

), the viscosity profile gradually flattens, reaching a near-constant value of approximately

![]() $0.9$

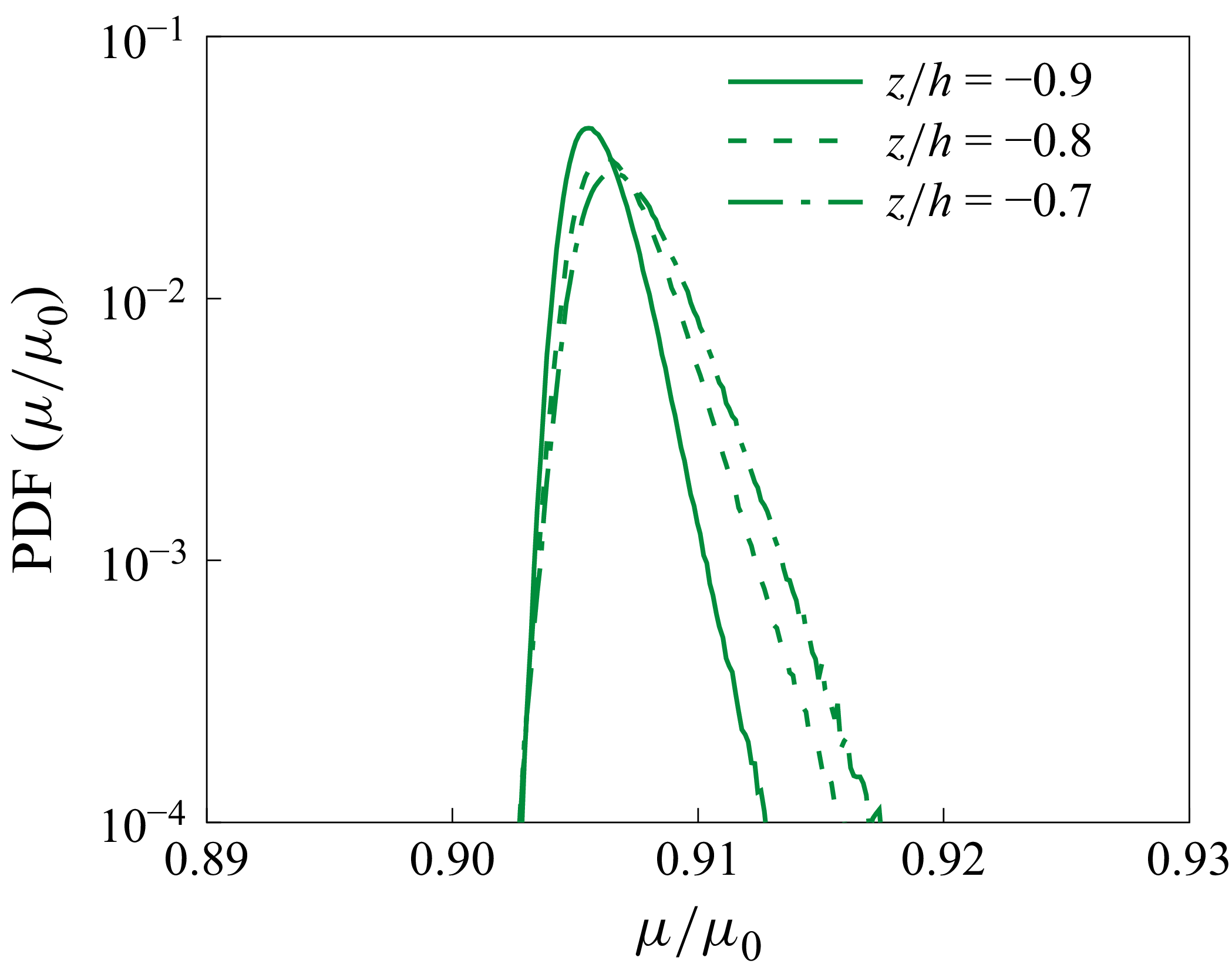

. Interestingly, the fluctuations of the actual viscosity in the lubricating layer are small, remaining within

$0.9$

. Interestingly, the fluctuations of the actual viscosity in the lubricating layer are small, remaining within

![]() $\pm 2\,\%$

of the mean value (see Appendix B for further details). Overall, for the present flow configuration, this behaviour can be interpreted as an equivalent viscosity ratio only slightly above

$\pm 2\,\%$

of the mean value (see Appendix B for further details). Overall, for the present flow configuration, this behaviour can be interpreted as an equivalent viscosity ratio only slightly above

![]() $x_0$

in the lubricating layer.

$x_0$

in the lubricating layer.

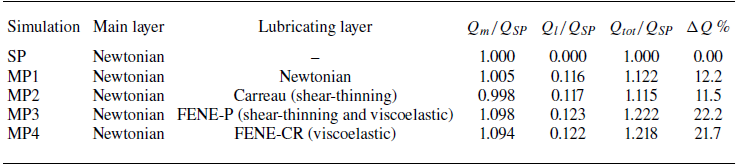

To quantify the drag reduction performance, we report in table 1 the flow rates of the main and lubricating layers,

![]() $Q_m$

and

$Q_m$

and

![]() $Q_l$

, together with the total flow rate

$Q_l$

, together with the total flow rate

![]() $Q_{\textit{tot}}$

, normalised by the SP reference value

$Q_{\textit{tot}}$

, normalised by the SP reference value

![]() $Q_{\textit{SP}}$

. For the Newtonian case,

$Q_{\textit{SP}}$

. For the Newtonian case,

![]() $Q_m$

matches the SP one despite one part of the channel being occupied by the lubricating layer. As a result, the total flow rate is approximately

$Q_m$

matches the SP one despite one part of the channel being occupied by the lubricating layer. As a result, the total flow rate is approximately

![]() $\sim 12\,\%$

larger than in the SP case. A comparable level of drag reduction is observed for the Carreau case (MP2). Here, shear-thinning does not induce significant modifications in

$\sim 12\,\%$

larger than in the SP case. A comparable level of drag reduction is observed for the Carreau case (MP2). Here, shear-thinning does not induce significant modifications in

![]() $Q_m$

, while

$Q_m$

, while

![]() $Q_l$

increases due to the lower mean wall viscosity

$Q_l$

increases due to the lower mean wall viscosity

![]() $\overline {\mu }_w$

; see inset of figure 2(

$\overline {\mu }_w$

; see inset of figure 2(

![]() $b$

). A notably different trend can be appreciated for the viscoelastic cases (MP3 and MP4), where a remarkable increase in both

$b$

). A notably different trend can be appreciated for the viscoelastic cases (MP3 and MP4), where a remarkable increase in both

![]() $Q_m$

and

$Q_m$

and

![]() $Q_l$

can be observed. With respect to the SP case, the total flow rate is approximately

$Q_l$

can be observed. With respect to the SP case, the total flow rate is approximately

![]() $\sim 22\,\%$

larger. This indicates that the presence of viscoelasticity introduces an additional and effective drag reduction mechanism, enhancing the volumetric flow rate beyond the gains associated with the interfacial dynamic alone. It can be observed that shear-thinning has a marginal effect on the resulting flow-rate: the FENE-CR case – purely viscoelastic – exhibits a similar increase in the flow rate.

$\sim 22\,\%$

larger. This indicates that the presence of viscoelasticity introduces an additional and effective drag reduction mechanism, enhancing the volumetric flow rate beyond the gains associated with the interfacial dynamic alone. It can be observed that shear-thinning has a marginal effect on the resulting flow-rate: the FENE-CR case – purely viscoelastic – exhibits a similar increase in the flow rate.

Table 1. Flow rates from simulations:

![]() $Q_m$

(main layer),

$Q_m$

(main layer),

![]() $Q_l$

(lubricating layer), and

$Q_l$

(lubricating layer), and

![]() $Q_{\textit{tot}}$

(total flow rate);

$Q_{\textit{tot}}$

(total flow rate);

![]() $Q_{\textit{SP}}$

is the single-phase flow rate. The percentage increase in flow rate relative to the SP case,

$Q_{\textit{SP}}$

is the single-phase flow rate. The percentage increase in flow rate relative to the SP case,

![]() $\Delta Q\,\%$

, directly reflects the amount of drag reduction obtained.

$\Delta Q\,\%$

, directly reflects the amount of drag reduction obtained.

3.2. Cross-section of channel flow

To gain further insights into the behaviour of the drag-reduced flows, we examine qualitative maps of the flow field in a cross-section of the channel. Figure 3 shows the instantaneous streamwise velocity distribution in a cross-section of the channel (

![]() $y$

–

$y$

–

![]() $z$

plane) located at

$z$

plane) located at

![]() $x/h=L_x/2=2\pi$

. Figure 3(

$x/h=L_x/2=2\pi$

. Figure 3(

![]() $a$

) corresponds to the SP case, while the drag-reduced cases are shown in the subsequent panels: Newtonian lubricating layer (figure 3

$a$

) corresponds to the SP case, while the drag-reduced cases are shown in the subsequent panels: Newtonian lubricating layer (figure 3

![]() $b$

), Carreau (figure 3

$b$

), Carreau (figure 3

![]() $c$

), FENE-P (figure 3

$c$

), FENE-P (figure 3

![]() $d$

) and FENE-CR (figure 3

$d$

) and FENE-CR (figure 3

![]() $e$

) lubricants. The position of the liquid–liquid interface (iso-level

$e$

) lubricants. The position of the liquid–liquid interface (iso-level

![]() $\phi =0$

) is also highlighted with a coloured line.

$\phi =0$

) is also highlighted with a coloured line.

Figure 3. Instantaneous distribution of the streamwise velocity

![]() $u^+$

in a wall-normal section (

$u^+$

in a wall-normal section (

![]() $y{-}z$

plane) located at

$y{-}z$

plane) located at

![]() $x/h=2\pi$

. (a) Single-phase case. (b–e) Multiphase cases with increasingly complex rheology. The position of the interface is reported with a coloured line. The images in (b,c) refer to the Newtonian and Carreau stratified cases, while (d,e) refer to the viscoelastic cases (FENE-P and FENE-CR).

$x/h=2\pi$

. (a) Single-phase case. (b–e) Multiphase cases with increasingly complex rheology. The position of the interface is reported with a coloured line. The images in (b,c) refer to the Newtonian and Carreau stratified cases, while (d,e) refer to the viscoelastic cases (FENE-P and FENE-CR).

For the SP case (figure 3

![]() $a$

), the familiar near-wall turbulence structures are recovered. For the Newtonian and Carreau cases (figures 3

b,c), the structure of the turbulence in the main layer is similar to that in the SP case, albeit with enhanced intensity. Here, turbulence is still present in the lubricating layer since its thickness is sufficient to sustain fluctuations; however, its magnitude is clearly weaker than in the main flow (Roccon et al. Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2019). This indicates that the interface hinders vertical momentum exchange, effectively decoupling the self-sustaining cycle of the lubricating region from turbulence in the main layer. On the other hand, the Carreau case introduces no significant changes compared to the Newtonian case. The reduction in mean viscosity (see inset of figure 2

$a$

), the familiar near-wall turbulence structures are recovered. For the Newtonian and Carreau cases (figures 3

b,c), the structure of the turbulence in the main layer is similar to that in the SP case, albeit with enhanced intensity. Here, turbulence is still present in the lubricating layer since its thickness is sufficient to sustain fluctuations; however, its magnitude is clearly weaker than in the main flow (Roccon et al. Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2019). This indicates that the interface hinders vertical momentum exchange, effectively decoupling the self-sustaining cycle of the lubricating region from turbulence in the main layer. On the other hand, the Carreau case introduces no significant changes compared to the Newtonian case. The reduction in mean viscosity (see inset of figure 2

![]() $b$

) slightly enhances turbulence intensity inside the lubricating layer, but the two cases exhibit similar behaviour.

$b$

) slightly enhances turbulence intensity inside the lubricating layer, but the two cases exhibit similar behaviour.

A more pronounced asymmetry emerges for the viscoelastic cases. Figures 3(d,e) (FENE-P and FENE-CR, respectively) show a notable attenuation of turbulent activity in the lubricating layer, although turbulence remains sustained given that the layer is sufficiently thick. This suppression results from the combined effect of the interface and the onset of viscoelastic turbulence. Here, polymer stresses actively modify near-wall dynamics: the altered flow field exhibits an increased spanwise spacing of velocity streaks together with a reduced frequency of burst events, in line with previous experimental observations of drag-reduced SP flows (Wei & Willmarth Reference Wei and Willmarth1992; White, Somandepalli & Mungal Reference White, Somandepalli and Mungal2004). By contrast, the main layer shows an increased turbulent kinetic energy production, consistent with the modifications observed in the mean velocity profiles. Again, no appreciable differences are observed when comparing FENE-P and FENE-CR.

An additional element of distinction among the cases can be identified in the behaviour of the liquid–liquid interface. In the Newtonian and Carreau cases, the interface undergoes significant perturbations, with frequent upward and downward motions that correlate with turbulent structures in the adjacent flow. In contrast, in the viscoelastic cases, the interface appears much less deformed, with both upward and downward displacements mitigated. As will be shown later, this reduced interfacial motion can be linked to the damping effect of viscoelastic stresses, which suppress wall-normal momentum transport and stabilise the interface.

3.3. Mean shear stress budget

To obtain a quantitative indication of previous observations, we analyse the mean shear stress budget along the wall-normal direction. We begin by applying Reynolds decomposition to the Navier–Stokes equations. Averaging over the homogeneous directions and assuming a steady-state flow, we obtain a one-dimensional momentum balance in the wall-normal coordinate:

where the first contribution results from the constitutive stress tensor, the second from the Reynolds stress tensor, and the last from the capillary stress tensor. For non-Newtonian fluids, the constitutive stress tensor contribution can be further divided into two contributions:

where the first part accounts for the stress induced by the mean velocity gradient, and the second accounts for additional non-Newtonian stresses. Thus the stress budget becomes

For a Newtonian fluid, the contribution

![]() $\tau _{\textit{nn}}$

vanishes, and the first contribution reduces to the classical viscous stress due to the mean shear:

$\tau _{\textit{nn}}$

vanishes, and the first contribution reduces to the classical viscous stress due to the mean shear:

Moving to non-Newtonian fluids, for a Carreau model, the viscous stress and non-Newtonian contributions are given by

and for the viscoelastic models (FENE-P or FENE-CR), these two contributions can be expressed as

For all non-Newtonian models, the sum of

![]() $\tau _v$

and

$\tau _v$

and

![]() $\tau _{\textit{nn}}$

represents the total wall stress, denoted as

$\tau _{\textit{nn}}$

represents the total wall stress, denoted as

![]() $\tau _w$

. As the pressure gradient driving the flow is kept constant in all configurations, in our dimensionless notation, the sum of the wall shear stress at the two walls is

$\tau _w$

. As the pressure gradient driving the flow is kept constant in all configurations, in our dimensionless notation, the sum of the wall shear stress at the two walls is

![]() $|\tau _{w}^m| + |\tau _{w}^l| = 2$

.

$|\tau _{w}^m| + |\tau _{w}^l| = 2$

.

Finally, the Reynolds stress and capillary stress contributions are defined as

where

![]() $u'$

and

$u'$

and

![]() $w'$

are the velocity fluctuations.

$w'$

are the velocity fluctuations.

Figure 4 shows the mean stress budget as a function of the wall-normal direction, and each plot shows a different contribution: viscous stress (figure 4

a), turbulent stress (figure 4

b), capillary stress (figure 4

c) and non-Newtonian stress (figure 4

d). First, we consider figure 4(a), which shows the wall-normal behaviour of the viscous stress

![]() $\tau _v$

. As expected,

$\tau _v$

. As expected,

![]() $\tau _v$

dominates in the near-wall regions, and decreases monotonically towards the channel centre. In the SP case, the profile is symmetric around the centreline. In contrast, in the lubricated cases, the presence of a moving interface induces a pronounced asymmetry. A clear reduction (and respectively an increase) in

$\tau _v$

dominates in the near-wall regions, and decreases monotonically towards the channel centre. In the SP case, the profile is symmetric around the centreline. In contrast, in the lubricated cases, the presence of a moving interface induces a pronounced asymmetry. A clear reduction (and respectively an increase) in

![]() $\tau _v$

is observed near the bottom (and top) wall as the rheological complexity of the lubricating layer increases, as can be appreciated in the two insets. In particular, a reduction in

$\tau _v$

is observed near the bottom (and top) wall as the rheological complexity of the lubricating layer increases, as can be appreciated in the two insets. In particular, a reduction in

![]() $\tau _v$

is already noticeable in the Carreau case, resulting from the combined effect of lower local viscosity and wall shear rates within the lubricating layer. This trend becomes more pronounced when viscoelastic effects are introduced: the decrease in

$\tau _v$

is already noticeable in the Carreau case, resulting from the combined effect of lower local viscosity and wall shear rates within the lubricating layer. This trend becomes more pronounced when viscoelastic effects are introduced: the decrease in

![]() $\tau _v$

near the bottom wall is stronger. This is due to a reduction in wall shear rates (see figure 2

b) and, secondarily, to a slight reduction in viscosity (FENE-P). Figure 4(b) shows the turbulent stress

$\tau _v$

near the bottom wall is stronger. This is due to a reduction in wall shear rates (see figure 2

b) and, secondarily, to a slight reduction in viscosity (FENE-P). Figure 4(b) shows the turbulent stress

![]() $\tau _t$

. Also in this case, a clear asymmetry is observed, closely mimicking the viscous stress, resulting in a distinct minimum in

$\tau _t$

. Also in this case, a clear asymmetry is observed, closely mimicking the viscous stress, resulting in a distinct minimum in

![]() $\tau _t$

near the average interface location (

$\tau _t$

near the average interface location (

![]() $z/h=-0.7$

). This leads to an increase in turbulence production in the main layer, and diminished turbulence activity within the lubricating layer. For the Carreau case, the mild reduction in viscous stress

$z/h=-0.7$

). This leads to an increase in turbulence production in the main layer, and diminished turbulence activity within the lubricating layer. For the Carreau case, the mild reduction in viscous stress

![]() $\tau _v$

near the bottom wall induces a slight increase in

$\tau _v$

near the bottom wall induces a slight increase in

![]() $\tau _t$

, due to the lower local viscosity. Upon the introduction of viscoelastic effects (dashed lines), the asymmetry in the turbulent stress distribution becomes more marked. Consequently, turbulence activity within the lubricating layer is strongly suppressed compared to the Newtonian and Carreau cases, thus the minimum in

$\tau _t$

, due to the lower local viscosity. Upon the introduction of viscoelastic effects (dashed lines), the asymmetry in the turbulent stress distribution becomes more marked. Consequently, turbulence activity within the lubricating layer is strongly suppressed compared to the Newtonian and Carreau cases, thus the minimum in

![]() $\tau _t$

becomes less pronounced. This behaviour seems to suggest that viscoelasticity produces a decoupling between streamwise and wall-normal velocity fluctuations (Ptasinski et al. Reference Ptasinski, Nieuwstadt, van den Brule and Hulsen2001), effectively leading to a decrease in the turbulent shear stress.

$\tau _t$

becomes less pronounced. This behaviour seems to suggest that viscoelasticity produces a decoupling between streamwise and wall-normal velocity fluctuations (Ptasinski et al. Reference Ptasinski, Nieuwstadt, van den Brule and Hulsen2001), effectively leading to a decrease in the turbulent shear stress.

Figure 4. Wall-normal distribution of the mean shear stress budget. (a) The viscous shear stress

![]() $\tau _v$

profiles, with insets zooming in to the regions near the top wall (

$\tau _v$

profiles, with insets zooming in to the regions near the top wall (

![]() $z/h \gt 0.94$

) and bottom wall (

$z/h \gt 0.94$

) and bottom wall (

![]() $z/h \lt -0.94$

). (b) The turbulent shear stress

$z/h \lt -0.94$

). (b) The turbulent shear stress

![]() $\tau _t$

. (

$\tau _t$

. (

![]() $c$

) The capillary stress

$c$

) The capillary stress

![]() $\tau _c$

profiles for the different multiphase cases, with an inset focusing on the interface region around

$\tau _c$

profiles for the different multiphase cases, with an inset focusing on the interface region around

![]() $z/h = -0.7$

. (

$z/h = -0.7$

. (

![]() $d$

) The non-Newtonian stress

$d$

) The non-Newtonian stress

![]() $\tau _{\mathit{nn}}$

profiles for the shear-thinning and viscoelastic cases, with an inset providing a close-up view of the lubricating layer region (

$\tau _{\mathit{nn}}$

profiles for the shear-thinning and viscoelastic cases, with an inset providing a close-up view of the lubricating layer region (

![]() $z/h\lt -0.6$

).

$z/h\lt -0.6$

).

Figure 4(c) shows the capillary stress

![]() $\tau _c$

. This stress peaks near the average interface position, and decays away from it, acting as a barrier to wall-normal momentum transport (see the corresponding minimum in

$\tau _c$

. This stress peaks near the average interface position, and decays away from it, acting as a barrier to wall-normal momentum transport (see the corresponding minimum in

![]() $\tau _t$

in figure 4

b). The inset shows the region

$\tau _t$

in figure 4

b). The inset shows the region

![]() $-1 \leqslant z/h \leqslant -0.4$

, highlighting how the capillary stress contributes to decoupling the dynamics of the two layers. As viscoelastic effects are introduced, both the intensity and spatial extent of

$-1 \leqslant z/h \leqslant -0.4$

, highlighting how the capillary stress contributes to decoupling the dynamics of the two layers. As viscoelastic effects are introduced, both the intensity and spatial extent of

![]() $\tau _c$

decrease, reflecting reduced interfacial fluctuations (thus lower interfacial area), and a diminished role of surface tension forces in regulating the wall-normal momentum exchange (Verschoof et al. Reference Verschoof, van der Veen, Sun and Lohse2016; Roccon et al. Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2019).

$\tau _c$

decrease, reflecting reduced interfacial fluctuations (thus lower interfacial area), and a diminished role of surface tension forces in regulating the wall-normal momentum exchange (Verschoof et al. Reference Verschoof, van der Veen, Sun and Lohse2016; Roccon et al. Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2019).

Finally, figure 4(d) shows the non-Newtonian stress

![]() $\tau _{\textit{nn}}$

. This stress is negligible for the Carreau case (see Appendix B) but becomes important when viscoelastic effects are introduced (dashed lines). In these configurations,

$\tau _{\textit{nn}}$

. This stress is negligible for the Carreau case (see Appendix B) but becomes important when viscoelastic effects are introduced (dashed lines). In these configurations,

![]() $\tau _{\textit{nn}}$

is non-zero at the wall and slightly increases moving away from the wall, reaches a maximum at approximately

$\tau _{\textit{nn}}$

is non-zero at the wall and slightly increases moving away from the wall, reaches a maximum at approximately

![]() $z/h = -0.95$

, then decreases monotonically towards the mean interface position. The presence of

$z/h = -0.95$

, then decreases monotonically towards the mean interface position. The presence of

![]() $\tau _{\textit{nn}}$

serves a twofold purpose. First, it promotes the development of viscoelastic turbulence within the lubricating layer, characterised by decorrelated streamwise and wall-normal velocity fluctuations, effectively leading to a decrease in the turbulent shear stress, as previously observed. Second, the non-Newtonian stresses contribute in damping the interface wavy motion, a phenomenon qualitatively similar to the observations of Rosti & Brandt (Reference Rosti and Brandt2017). To maintain the shear stress budget along the wall-normal direction, an increase in

$\tau _{\textit{nn}}$

serves a twofold purpose. First, it promotes the development of viscoelastic turbulence within the lubricating layer, characterised by decorrelated streamwise and wall-normal velocity fluctuations, effectively leading to a decrease in the turbulent shear stress, as previously observed. Second, the non-Newtonian stresses contribute in damping the interface wavy motion, a phenomenon qualitatively similar to the observations of Rosti & Brandt (Reference Rosti and Brandt2017). To maintain the shear stress budget along the wall-normal direction, an increase in

![]() $\tau _{\textit{nn}}$

is accompanied by a reduction of the turbulent and capillary stresses. The reduced turbulent stresses lead to a reduction of the momentum exchange along the wall-normal direction (Verschoof et al. Reference Verschoof, van der Veen, Sun and Lohse2016; Roccon et al. Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2019). Likewise, the reduction in the capillary stresses reflects the interface stabilisation induced by viscoelasticity and thus the corresponding reduced wave amplitude.

$\tau _{\textit{nn}}$

is accompanied by a reduction of the turbulent and capillary stresses. The reduced turbulent stresses lead to a reduction of the momentum exchange along the wall-normal direction (Verschoof et al. Reference Verschoof, van der Veen, Sun and Lohse2016; Roccon et al. Reference Roccon, Zonta and Soldati2019). Likewise, the reduction in the capillary stresses reflects the interface stabilisation induced by viscoelasticity and thus the corresponding reduced wave amplitude.

3.4. Quadrant analysis

To better understand the mean shear stress budget results and the physical mechanisms driving drag reduction, we now examine the quadrant contributions to the turbulent shear stress (Wallace, Eckelmann & Brodkey Reference Wallace, Eckelmann and Brodkey1972). This approach decomposes the Reynolds stresses

![]() $\tau _t = -\overline { u'w'}$

into contributions associated with four types of events: (i) outward interactions of high-speed fluid (Q1,

$\tau _t = -\overline { u'w'}$

into contributions associated with four types of events: (i) outward interactions of high-speed fluid (Q1,

![]() $u'\gt 0,\ w'\gt 0$

); (ii) ejections of low-speed fluid (Q2,

$u'\gt 0,\ w'\gt 0$

); (ii) ejections of low-speed fluid (Q2,

![]() $u'\lt 0,\ w'\gt 0$

); (iii) inward interactions of low-speed fluid (Q3,

$u'\lt 0,\ w'\gt 0$

); (iii) inward interactions of low-speed fluid (Q3,

![]() $u'\lt 0,\ w'\lt 0$

) and (iv) sweeps of high-speed fluid towards the wall (Q4,

$u'\lt 0,\ w'\lt 0$

) and (iv) sweeps of high-speed fluid towards the wall (Q4,

![]() $u'\gt 0,\ w'\lt 0$

). Figure 5 shows the averaged quadrant contributions to

$u'\gt 0,\ w'\lt 0$

). Figure 5 shows the averaged quadrant contributions to

![]() $\tau _t$

in the lower portion of the channel (

$\tau _t$

in the lower portion of the channel (

![]() $z/h\lt -0.4$

), where the lubricating layer is located. Colours are used to identify the different cases: SP (black thin line), Newtonian (violet solid line), Carreau (green solid line), FENE-P (green dashed line) and FENE-CR (violet dashed line). Symbols are used to distinguish among Q1 (positive), Q2 (negative), Q3 (positive) and Q4 (negative) events.

$z/h\lt -0.4$

), where the lubricating layer is located. Colours are used to identify the different cases: SP (black thin line), Newtonian (violet solid line), Carreau (green solid line), FENE-P (green dashed line) and FENE-CR (violet dashed line). Symbols are used to distinguish among Q1 (positive), Q2 (negative), Q3 (positive) and Q4 (negative) events.

Figure 5. Quadrant contributions to the turbulent shear stress in the lubricating layer (

![]() $z/h \lt -0.7$