Departing the domus

Republican Rome pulsed with rhythmic commercial, political, and religious activity, rhythms determined by the fasti.Footnote 1 Urban spaces were shaped by these rhythms. Such spaces were ‘the realisations, inscriptions in the simultaneity of the external world of a series of times: the rhythms of life, the rhythms of the urban population’, to borrow Henri Lefebvre’s temporospatial aphorism on contemporary urbanism (Reference Lefebvre2001: 224). Where did Roman women feature in these spaces and rhythms? Was the domus their domain? Were female appearances in public ‘abnormal’ or ‘transgressive’?Footnote 2 Many scholars have adduced the lost inscription for a Claudia who managed the home and made wool (CIL 6.15346) as evidence for female domesticity and relative invisibility.Footnote 3 By contrast, others have recognised the highly visible sacerdotal (priestly) and non-sacerdotal roles that women played in regular religious rituals in the Republic, rituals which led them into numerous public and sacred spaces, and could include sacrifices pro populo.Footnote 4 Notably, I have argued that women’s public religious roles authorised and legitimated (some) female involvement in politics and public spaces.Footnote 5 This article offers a theoretical intervention in this discussion: an intersectional and temporospatial analysis of female visibility during religious activity in urban spaces in Republican Rome. My focus is on the regular religious activity of prominent female religious officials (Vestals, flaminica Dialis, regina sacrorum) and collectives of women of varying statuses (matronae, ancillae). Such an approach and focus, I argue, reshapes our understanding of the visibility of women in urban spaces. For if we turn our gaze away from the domus-bound Claudia, another vision emerges, in which a woman’s intersectional statuses and temporality are key dimensions differentiating her visibility.

Onwards to a few definitional and theoretical matters. Urban spaces are defined here as public, private, and sacred spaces within Rome, encompassing areas within the pomerium and one mile beyond it – everything domi, the sphere of civil law.Footnote 6 Visibility is conceptualised as a perceptive phenomenon, event, or act including the perceiving subject and the perceived, following the perspectives of Andrea Mubi Brighenti.Footnote 7 This definition is akin to Harriet Flower’s ‘seeing and being seen’.Footnote 8 Such visibility is not an uncomplicated good; rather, it is fundamentally ambivalent. For the perceived might be enabled or empowered through recognition, but, contrariwise, might be disabled or disempowered through control and surveillance. During visual spectacles – so common in the Republic – those on display might also face significant risks to their reputations and positions.Footnote 9 Thence visibility is not necessarily positive for the perceived. A fundamental theoretical premise of this article is that women’s lives and identities are not homogeneous or monolithic. Prompted by the intersectional scholarship of Kimberlé Crenshaw and others, I acknowledge that women’s experiences are shaped by multiple, intersecting dimensions beyond gender, including, for example, ethnicity, class, age, sexuality, and ability.Footnote 10 This intersectional premise is apropos to the Republic: Suzanne Dixon and Amy Richlin have underscored how various dimensions affected women’s lives and identities in the Republic, including gender and socio-economic, legal, ethnic, marital, and age status, and more.Footnote 11 This article thus adopts an intersectional approach, attending to the influence of multiple dimensions on female visibility in urban spaces, particularly status and temporality.

But why religion? Religious roles and activity were thought to empower some women, particularly elite women and priestesses. For example, in a letter to her younger son Gaius Sempronius Gracchus (RE 47, tr. pl. 123, 122 BCE),Footnote 12 Cornelia admonished him and aimed at dissuading him from his political goals in charged religious language that focused on her future divine status as one of the di parentes, Caius’ consequent worship of her at the Parentalia, and the divine authority of Jupiter (Nep. fr. 59 Marshall).Footnote 13 Similarly, during Marcus Fonteius’ (RE 12, pr. 75 BCE?) repetundae trial in c. 69 BCE, Cicero reminded the jurors of the necessity of the Vestal Virgins’ prayers for Rome, warning them of the religious consequences and peril that awaited them if they rejected the plea of Marcus’ sister the Vestal Fonteia (RE 31) (Cic. Font. 47–8).Footnote 14 Both Cornelia’s and Fonteia’s claims to authority were based on their religious roles (current and future), and regular religious activity and knowledge are assumed. Such activity could be political and hyper-visible, as attested in Polybius’ accounts of Pomponia (RE 28) and Tertia Aemilia (RE 179), mother and wife of Publius Cornelius Scipio Africanus (RE 336, cos. 205, 194 BCE) respectively, and of Papiria (RE 78), mother of Publius Cornelius Scipio Aemilianus (RE 336, cos. 147, 134 BCE). Pomponia famously visited numerous temples and sacrificed on behalf of her other son Lucius Cornelius Scipio Asiagenus (RE 337, cos. 190 BCE) during his aedilician electoral campaign (Polyb. 10.4.4–8),Footnote 15 while Aemilia and Papiria participated in conspicuous processions and public sacrifices in elaborate dress and a mule-driven four-wheeled vehicle, used gold and silver religious instruments, and were accompanied by muleteers and large retinues of enslaved persons. Notably, prior to receiving Aemilia’s equipment from Aemilianus, Papiria had refrained from such religious activity, as her appearance was not commensurate with her noble birth. After receipt of this gift, Papiria participated in these events, and other women saw and identified her vehicle, mules, and muleteers (Polyb. 31.26.3–8).Footnote 16 Clearly, when certain religious events occurred in Rome, some elite women were hyper-visible in urban spaces, and there were social expectations among the elite for them to conspicuously display their capital therein – to ‘keep up appearances’.Footnote 17

Cornelia, Cicero, and Polybius’ testimony reveals the fruitfulness of a focus on religious activity, hints at the utility of a temporospatial approach to female visibility, and prompts a range of questions. What were some of the temporospatial conditions of female visibility during religious activity? Were there gendered rhythms in the Urbs? This article develops a framework for tracing gendered rhythms (Re-visions), and seeks out some of the intersections between female visibility, religious activity, temporality, and urban spaces in Republican Rome, with a particular focus on the regular religious activity (Ritual rhythms) of prominent female religious officials and collectives of women. Ultimately, I aim to (re)assert time’s place in shaping urban spaces and female visibility therein.Footnote 18

Re-visions: female visibility, temporality, and gendered rhythms in the Urbs

How might we trace gendered rhythms in the Urbs? I begin with a brief reassessment of female visibility in Republican Rome and then turn to a temporospatial approach thereto.

Female visibility in Republican Rome

To be was to be seen in Republican Rome.Footnote 19 The Urbs was a city of spectacle and ‘specta(c)tors’, wherein much of urban life was conducted face-to-face, and where publicity and visibility were key characteristics of religion and politics.Footnote 20 Hence Plautus’ ‘those who see (qui vident), know it distinctly (plane sciunt)’ (Plaut. Truc. 490) and ‘look (specta), then you’ll know (tum scies)’ (Plaut. Bacch. 1023), the frequent use of the expressions palam (openly) and luci (before the light of day) in literature and statutes,Footnote 21 and the use of apud vos (before you, viz. an audience) in early inscriptions and oratory.Footnote 22 Indeed, concepts of visibility and publicity were linked with and became bywords for the Roman elite, and there were social expectations for this elite to engage in public, conspicuous displays before the wider community, as we saw with Aemilia and Papiria.Footnote 23 Despite these associations, earlier scholarship has tended to assert that women only became especially visible in Republican Rome and Italy during the first century BCE (due to civil crises),Footnote 24 and has drawn on a small selection of ancient sources – including the Claudia inscription – to allege female domesticity, exclusion (ideological or actual) from public space, and relative invisibility.Footnote 25 Yet, such a view is increasingly outdated. A rich body of recent scholarship indicates that women – from enslaved to elite – moved through public and sacred spaces throughout the city during regular activity on their way to religious festivals, houses, banquets, commercial activities, funerals, games, and more.Footnote 26 Notably, Amy Richlin’s new study on ‘the Woman in the Street’ has uncovered the visibility of women (enslaved to elite) already in the Middle Republic, in drama, in public religious activity, in various public reactions to conflicts, and more.Footnote 27 So, what to do with the old view of female invisibility?

It may be best simply to discard such a view and begin anew,Footnote 28 especially as the (in)famous Claudia inscription might be inauthentic, and is hardly representative for all women.Footnote 29 Now, I concede that other Republican evidence exists that locates some famous elite women in the domus, but it does not support their invisibility or segregation from public spaces.Footnote 30 More than a decade ago, Mary Boatwright drew on similar evidence to argue for the ideological exclusion of women from the public, political Forum Romanum.Footnote 31 Roman regulations offer a salutary corrective. There are simply no (surviving) long-term legal restrictions that confined women to the domus or imposed a form of gendered spatial segregation, although, again, I concede that individual men and custom might have constrained some women from public actions and entering some spaces. Some caution is warranted here, as two regulations and some (probable) customs imposed some spatial constraints. A senatorial decree of 216 BCE temporarily compelled married women to keep away from public space and to be confined within their homes, but this decree was part of a broader set of restrictions on mourning after the crisis at Cannae and had funerary implications.Footnote 32 One form of female mobility (the use of the two-wheeled carpentum for secular activities) was temporarily restricted by the lex Oppia of 215–195 BCE.Footnote 33 The first indicates the atypical nature of domestic confinement for (free) women, while the latter was repealed after (elite) women publicly lobbied their male relatives and magistrates, decidedly testifying to their lack of confinement. Regarding customs, there is some late evidence from Valerius Maximus and Gellius that women were socially discouraged from attending contiones (public meetings) and comitia, and from speaking in the Forum and iudicia (trials), although this evidence may be anachronistic and there are counterexamples.Footnote 34 Admittedly, women spent significant time in the domus – as did men –, but no regulation appears to have confined them there. Rather, women appeared regularly throughout Rome during their religious activity, as we will see.Footnote 35

We can go even further. Amy Russell has convincingly demonstrated how public, private, and sacred spaces intersected and overlapped in Rome, the associated impossibility of the total exclusion of women from public spaces, and the significant impact of a person’s varying status – particularly socio-economic statusFootnote 36 – on gendered spatial experiences.Footnote 37 While some ancient sources might suggest the exclusion of women from some public spaces in Rome (in some instances), there is no reason to suppose this held true for all women or at all times. Moreover, surviving ancient literary sources – typically male-authored – are particularly unreliable witnesses to gendered spatial experiences or segregation, as they frequently disregard or suppress details about women, or present them in a stereotypical fashion.Footnote 38 Even with these problems, our sources offer a far more complex vision of female visibility in urban spaces in Rome than earlier scholarship has allowed, as my earlier examples from the works of Cicero and Polybius indicate, and Russell’s scholarship underscores. Gendered spatial segregation appears to have been fairly limited and socio-economic status far more influential than gender in differentiating spatial experiences. Perhaps, then, we should simply start from the position that most spaces were accessible to women in Rome (in the absence of strong opposing evidence), and that some women like Pomponia, Aemilia, Papiria, and Fonteia could be as visible as their male relatives, or perhaps even more so at certain times of the year.

A temporospatial approach

Attention to both time and space – a temporospatial approach – is vital for any (re)assessment of female visibility and spatial usage in cities, ancient or modern. Here, I build on the efflorescence of recent work by urban theorists, feminist scholars, and cultural geographers on ‘timespace’, the relationships between, and mutual entanglement of, time and space.Footnote 39 Henri Lefebvre’s final works began to touch on these interrelations and on urban rhythms, especially his essay with Catherine Régulier on the rhythmanalysis of Mediterranean cities and his posthumously published final volume Éléments de rythmanalyse: Introduction à la connaissance des rythmes (Reference Lefebvre1992).Footnote 40 Lefebvre focused on the rhythms and temporalities of daily life in cities, notions of localised time and temporalised place, and the variabilities of cyclical (e.g. days, nights, hours, months, seasons, years, rituals, etc.) and linear (consecutive, repeated, regular activity, e.g. work) rhythms.Footnote 41 Both he and Régulier also underscored the connection between rituals (sacred, profane, political) and the rhythms of Mediterranean cities, especially the ways in which rituals intervene in daily life and connect a person’s body, tongue, speech, and gestures with specific places.Footnote 42 Mediterranean cities are, for them, not characterised by a singular rhythm, but instead by polyrhythmia, plural rhythms existing in interaction and conflict.Footnote 43 For them, urban space in Mediterranean cities is the site of a vast staging of such rhythms; there, rites, codes, and relations are made visible – there, they are acted out.Footnote 44 Urban theorists and cultural geographers have moved away from Lefebvre’s antinomic cyclical and linear rhythms, but continue to take inspiration from the concept of temporalised place (or space) and polyrhythmia.Footnote 45 Notably, Mike Crang and Kirsten Simonsen understand cities as polychronic with plural rhythms, namely as sites where different temporalities and spatialities collide.Footnote 46 Crang stresses that these rhythms are not always harmonic, but rather ‘tangles of people’s lives with their different points of intersection with different times and other people, marching to different beats’ (Reference Crang, May and Thrift2001: 192). Both Crang and Simonsen find that people’s intersectional differences (e.g. gender, status, ethnicity, etc.) and bodies shape their spatial experiences and, in turn, shape urban spaces.Footnote 47 Simonsen envisions the ‘embodied city as a ceaseless spatio-temporal process of construction’ (Reference Simonsen, Bærenholdt and Simonsen2016: n.p.), in which the city is gendered by bodily ascribed identities. These studies open up the possibility of investigating gendered rhythms in the Urbs.

What characterises female temporospatial experiences – their gendered rhythms – in urban spaces? Simonsen has drawn on the foundational work of the feminist theorist Iris Marion Young to suggest that women in contemporary cultures tend to ‘live their bodies simultaneously as subjects and objects’ – they experience their bodies as both a ‘background and means’ for their own activities and as being seen as ‘potential object[s] of others’ intentions’ – and that this ambiguous existence tends to keep a woman in ‘her place’, restricting her forms of movement, her spatial relationships, and her appropriation of space (Simonsen Reference Simonsen, Bærenholdt and Simonsen2016: n.p. after Young Reference Young1980). In this view, female spatiality involves ‘an experience of spatial constitution’ and one of ‘being “positioned” in space’, whereby ‘feminine existence tends to posit an enclosure between itself and the space surrounding it, such that the space belonging to it is constricted but is also a defence against bodily invasion’. Thence, women may take particular care in ‘not frequenting the city at specific times or in specific places’ and ‘not wearing specific clothes’ (Reference Simonsen, Bærenholdt and Simonsen2016: n.p.). The existence of such gendered rhythms is evidenced in various studies of past and present societies by feminist scholars, urban theorists, and feminist geographers. These have collectively indicated the key place of time (of day, week, month, season) in mediating gendered spatial segregation (inclusion, exclusion, presence) and female movement in urban spaces.Footnote 48 Case studies of contemporary, modern, and premodern cities offer further insights. For example, analyses of the gendered usage of urban spaces in contemporary Kolkata, Mumbai, and Riyadh have indicated that women in these cities regulate the times of day they travel (avoiding night-time in particular) and the types of places they access and use for reasons of safety and respectability (to reduce the risk of violence and social stigmatisation), monitor themselves in these spaces (keeping alert to risks and modifying their movement), and often seek female companions and male protectors. Women in these cities also wear types of dress to maintain respectability and are aware of annual events where it is deemed respectable for women to be visible.Footnote 49 Feminist geographers’ studies of various European and North American cities (including London and Boston in the modern era) have indicated comparable phenomena.Footnote 50 Indeed, Wilson views these as cross-cultural and transhistorical phenomena, at least to some degree, although modernity has altered female visibility. For Wilson, women’s premodern experiences of the city have been ‘to live in it, but hidden; to emerge on sufferance, veiled’, but with modernity, ‘cities of veiled women have ceded to cities of spectacle and voyeurism, in which women, while seeking and sometimes finding the freedom of anonymity, are often all too visible … a part of the spectacle’ (Reference Wilson1991: 16). Even so, ‘men and the state continue their attempts to confine them [women] to the private sphere or to the safety of certain zones’, indicating their ‘underlying disquiet that women are roaming the streets’ (Wilson Reference Wilson1991: 16). We might perhaps question whether there was such a radical shift from cities of veiled to unveiled women, but it is clear that time can significantly impact female visibility and spatial usage in a city, and that companions, codes of dress, and ‘respectable’ events can help women navigate urban space.

But how similar were gendered rhythms in premodern cities like Rome in the Republic? Of particular comparative relevance is Elizabeth Cohen’s study on women in Roman streets in the sixteenth and seventeenth centuries. Her study draws on a rich body of visual, regulatory, and judicial evidence to indicate that religion and work legitimated many women’s ventures into urban space.Footnote 51 ‘Practices of dress’ distinguished women by status – ‘nuns and widows from wives and nubile girls’ (Cohen Reference Cohen2008: 302) – that is, the presence or absence of status symbols marked out women and their status in the streets. For example, the veil (lenzuolo) distinguished between ‘respectable women’ (veiled) and sex workers (unveiled).Footnote 52 A rich vision of female temporospatial experiences in early modern Rome emerges from her study, particularly of working-class women, who ventured out of their homes into neighbourhood spaces for work, commercial activity, and community life (including everything from socialising to conflicts to community welfare), but also left their neighbourhoods to view ‘special religious and civic events or to visit suburban gardens for recreation or work’ (Cohen Reference Cohen2008: 310–11). Perhaps, then, we should expect an array of gendered rhythms in past cities, rhythms shaped, in part, by roles and socio-economic status. Monika Trümper has already proposed that time of day and month may have played a role in a gender-differentiated use of space in ancient Mediterranean cities.Footnote 53 Key studies by scholars of Roman religion(s) have moreover indicated the presence of women of varying statuses in public religious activity throughout urban spaces in Republican Rome, notably during religious festivals, and that women could be distinguished by their status symbols at these events.Footnote 54 More recently, Esther Eidinow, Lisa Maurizio, and their contributors in Narratives of Time and Gender in Antiquity (Reference Eidinow and Maurizio2020) have considered the ways in which time is gendered in various Greek and Roman narratives, and encouraged further investigation of the intersections of gender and time. Collectively, these studies suggest that temporality, religious activity, and status symbols influenced female visibility in urban spaces in Republican Rome.

How can a temporospatial approach reshape our understanding of female visibility in urban spaces in Republican Rome? For Simonsen, ‘thinking in rhythms of the city opens up a path to an understanding of urban life through alternating successions of interactive bodies during day and night’ (2016: n.p.), while for Crang ‘thinking of the rhythms of particular locales begins to offer a better grasp on the linking of space and time’ and ‘the temporalisation of place removes a sense of self-contained moments and acts linked by external logics to open possibilities of immanent and emergent orders’ (Reference Crang, May and Thrift2001: 206). Essentially, such approaches allow for more diverse conceptions of urban life, past and present: as rich palimpsests of ‘experiences and encounters between different bodies in lived, perceived and conceived space’ (Simonsen Reference Simonsen, Bærenholdt and Simonsen2016: n.p.). In the case of Republican Rome, there exist long-standing and resilient misconceptions about female (in)visibility and domestic confinement: an attention to the intersections of time and space allows us to advance alternative visions of women’s lives, to re-envision their presence in the Urbs.

If we revisit Cicero’s image of the Vestal Fonteia in the Pro Fonteio, attending in particular to temporospatial elements, we can recognise that he locates her body and actions in temporalised places: daily lamentations (cotidianae lamentationes) at the altars of the gods and mother Vesta (arae deorum immortalium Vestaeque matris), labours (labores) through the watches of the night (nocturnae vigiliae) (in the temple of Vesta), and hands (manus) she is accustomed (consuescere) to extend to the gods in supplication (at their temples) and that are now extended to the jurors (presumably during the trial in the Forum Romanum).Footnote 55 Now, Cicero clearly expected the jurors to accept (some) of his claims about Fonteia’s regular religious activity, and he thus offers valuable insight into elite male perceptions of one woman’s life. Fonteia was represented as a regular, visible presence in the Urbs, as assumedly were other Vestals and female religious officials more generally. Similarly, Polybius attests to the conspicuous presence of Aemilia and Papiria at regular processions and sacrifices, and many other women like them. These examples encourage further enquiry into the regular religious activity of female religious officials and other women, and prompt a keen attention to the temporospatial dimensions thereof.

Ritual rhythms: regular female religious activity in Republican Rome

We move now to the gendered rhythms of Republican Rome, the ritual ones in particular. Festivals (feriae) and other events on the annual calendar regularly included female religious officials and collectives of women of various statuses. Granular details about the time of day for such events are rarely available, but evidence for time of month and year exists in surviving calendars and other ancient evidence. This evidence often includes a time and location(s), so a temporospatial analysis is possible.Footnote 56 During these rituals, as we will see, women and their status could be distinguished by their dress and other status symbols. We will see that women of varying roles and statuses appeared throughout urban spaces at regular intervals in the year, and, accordingly, they shaped these spaces.

Manus supplices: Vestals, flaminica Dialis, regina sacrorum, and their regular religious activity

The Vestal Fonteia was one among many female religious officials, and a familiar sight in the Urbs. Women occupied many sacerdotal public offices in the Republic, particularly elite women.Footnote 57 Principal among these priestesses were the six patrician and plebeian Vestal Virgins, the patrician flaminica Dialis (priestess of Jupiter), and the patrician regina sacrorum (queen of the sacred rites), all prominent and prestigious priesthoods and putative members of the pontifical college.Footnote 58 Various other female priesthoods are known (e.g. other major and minor flaminicae, sacerdos Fortunae Muliebris, sacerdotes Liberi, and sacerdos Cereris). The Vestals and the flaminica Dialis are of particular interest as they functioned as role models during their lifetimes.Footnote 59 Their religious authority and capacity within Rome is clear: along with a few other priestesses, they could offer sacrifices on behalf of the People (pro populo), and were thus responsible for the maintenance of human–divine relations for their community.Footnote 60 The Vestals, flaminica Dialis, and regina sacrorum had particularly prominent roles during public festivals and other religious events, and were themselves from elite families, probably senatorial or equestrian.Footnote 61 My focus will be on these three prominent priesthoods, for substantial evidence for their regular religious activity and its locations survives.Footnote 62

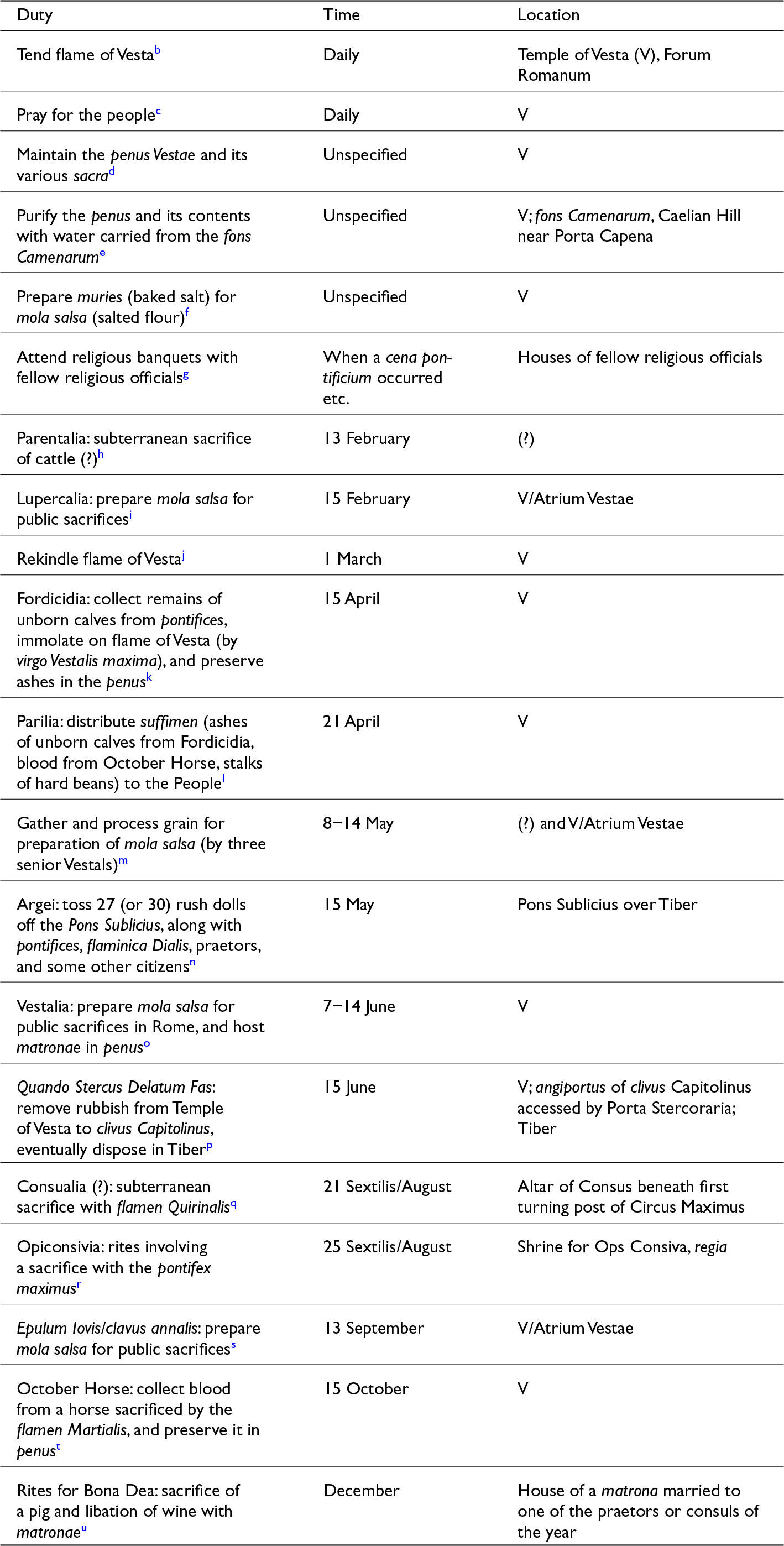

Vestals like Fonteia had regular religious duties all through the year and participated in numerous festivals. The most well-attested are detailed in Table 1.Footnote 63

The Vestals had a full ritual schedule: their hands were frequently extended to the immortal gods on behalf of the People. Given their daily presence at the Temple of Vesta – tending the goddess’ flame – and their regular movement through the Forum Romanum – perhaps especially their transportation of water from the fons Camenarum – the Vestals shaped and gendered the political heart of Rome. Additionally, their roles in the Parilia and Vestalia connected them temporally, spatially, and materially to other festivals, all public sacrifices, and households throughout Rome. Firstly, the suffimen distributed to the People by the Vestals at the Parilia was composed from the remnants of sacrifices of at least two festivals and from another unknown religious event (ashes of unborn calves from Fordicidia, blood from the October Horse, and stalks of hard beans). This assemblage of materials, used for fumigation during purification rites in the Parilia, thus connected these temporally distant religious events, perhaps the seasons themselves, the Vestals, and Roman households.Footnote 64 Secondly, the mola salsa (salted flour) – a mixture of ground far (spelt) and baked salt prepared during the Lupercalia, Vestalia, and the epulum Iovis/clavus annalis – was used by religious officials in every public sacrifice (sprinkled over the victim during the immolatio).Footnote 65 The grain was gathered and processed in May by the three senior Vestals, and the salt prepared at an unknown time.Footnote 66 The penus of the Temple of Vesta contained these various ingredients and products, and was thus a sacred storeroom for all Rome.Footnote 67 In a way, the suffimen and mola salsa were a distributed, material manifestation of the Vestals, moving throughout the city. The Vestals and their ritual products unified all public religious activity: they were the threads that bound a seemingly disparate calendar of festivals and other religious events.Footnote 68 The Vestals’ ritual programme marked the passage of the year and connected all public religious activity to Vesta’s temple in the heart of Rome. The Vestals were temporospatial conductors.

Table 1. Vestals and their religious duties (uncertainty denoted by ‘(?)’)a

Notes:

a Cf. similar table in Webb (2024) 53–5.

b E.g. Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom. 1.38.3; 2.67.3, 5; Plut. Vit. Num. 9.5–6, 10.4 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 189–91.

c As suggested by Cic. Font. 46–48; Hor. Carm. 1.2.26–8 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 191–2; Webb (Reference Webb, Burden-Strevens and Frolov2022) 163–7.

d Ov. Fast. 3.11–12; Plin. HN 28.7.39; Plut. Vit. Cam. 20.3; Vit. Num. 13.2; Festus 296L with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 192–5.

e Ov. Fast. 3.11–12; Plut. Vit. Num. 13.2; Festus 152L with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 194; (Reference DiLuzio and Blakely2017) 219–21.

f Festus 152L with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 196.

g E.g. the elaborate cena pontificium (pontifical banquet) for the inauguration of the new flamen Martialis Lucius Cornelius Lentulus Niger (RE 234, pr. before 60) and flaminica Martialis Publicia (RE 27) in c. 69 BCE, which included the Vestals Arruntia (RE 27), Licinia (RE 185), Perpennia (RE 8), and Popillia (RE 34): Macrob. Sat. 3.13.11 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 186.

h CIL 12, p. 258 (Fasti Philocali); Prud. C. Symm. 2.1107–8 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 214.

i Serv. Auct. ad Ecl. 8.82 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 196.

j Ov. Fast. 3.135–40; Macrob. Sat. 1.12.6 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 25.

k Inscr. Ital. 13.2.1 (Fasti Antiates Maiores); 13.2.17 (Fasti Praenestini); Ov. Fast. 4.629–40, 721–34 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 201–2.

l Ibid.

m Serv. Auct. ad Ecl. 8.82 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 195–6.

n Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom. 1.38.3; Ov. Fast. 5.621–2; Plut. Quaest. Rom. 86; Festus 14L (Paulus) with Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 106; DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 203–5.

o Inscr. Ital. 13.2.1 (Fasti Antiates Maiores); Ov. Fast. 6.310–18, 395–7; Festus 296L; CIL 12, p. 266 (Fasti Philocali); Serv. Auct. ad Ecl. 8.82 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 205–8.

p Inscr. Ital. 13.2.1 (Fasti Antiates Maiores); Varro, Ling. 6.32; Ov. Fast. 6.713–14; Festus 466L with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 208–9.

q Inscr. Ital. 13.2.1 (Fasti Antiates Maiores); Tert. De spect. 5.7 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 209–10. Cf. Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom. 2.31.2.

r Varro, Ling. 9.21; Festus 292L with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 210–11.

s Serv. Auct. ad Ecl. 8.82 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 196.

t Ov. Fast. 4.721–734; Prop. 4.1.17–20 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 211. Cf. Festus 246L (Paulus).

u Cic. Att. 1.13.3; Har. resp. 12–13, 37; Plut. Quaest. Rom. 20; Vit. Caes. 9.4–10.11; Vit. Cic. 19.4–5; 20.1–3; Cass. Dio 37.45.1–2 with Brouwer (Reference Brouwer1989) 270–1; Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 142–3; DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 212–13; Webb (Reference Webb, Damon and Pieper2019b) 258; (Reference Webb, Burden-Strevens and Frolov2022) 164–5. Sacrifice: Macrob. Sat. 1.12.23, 25 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 212–13.

The Vestals’ costume and religious instruments distinguished them during their regular religious activity. They donned or bore the following: the seni crines hairstyle (six-tressed braids), which was also worn by brides; woollen infula (band) and vittae (fillets/bands); a white praetextate suffibulum (a kind of veil); a palla (mantle); a tunica (tunic); soft shoes; the secespita (an iron sacrificial knife with an ivory handle, and silver, bronze, and gold decorations); the culigna (one-handled vessel for libations); the futtile (a special vase for water); and the urceus (a one-handled jug).Footnote 69 The Tabula Heracleensis indicates that the Vestals, rex sacrorum, and flamines were also entitled to be conveyed in plaustra (vehicles) for sacra publica (public religious activity) throughout Rome by c. 45 BCE.Footnote 70 By 42 BCE, Vestals could also be attended by a lictor curiatus, an attendant who indicated both the priestesses’ high status and membership of the pontifical college.Footnote 71 The Vestals’ vehicles and lictors enhanced their prestige and visibility beyond that of many other elite men and women. Only senior priests and magistrates were as visible. We might imagine male activity at iudicia, contiones, and the comitium as central to the rhythms of the Forum, but the Vestals were equally if not more central and visually prominent therein and beyond. The Vestals ensured that many public and sacred spaces were not gendered ‘male’ per se. How could they be when an essential element of public sacrifices (mola salsa) was made by the Vestals? When these priestesses’ nightly activity and prayers were thought to preserve Rome? Hence Horace’s evocative image of the tacita virgo (silent virgin) and pontifex ascending the Capitoline Hill (Carm. 3.30.7–9): a metonym for the Urbs and its temporal longevity.

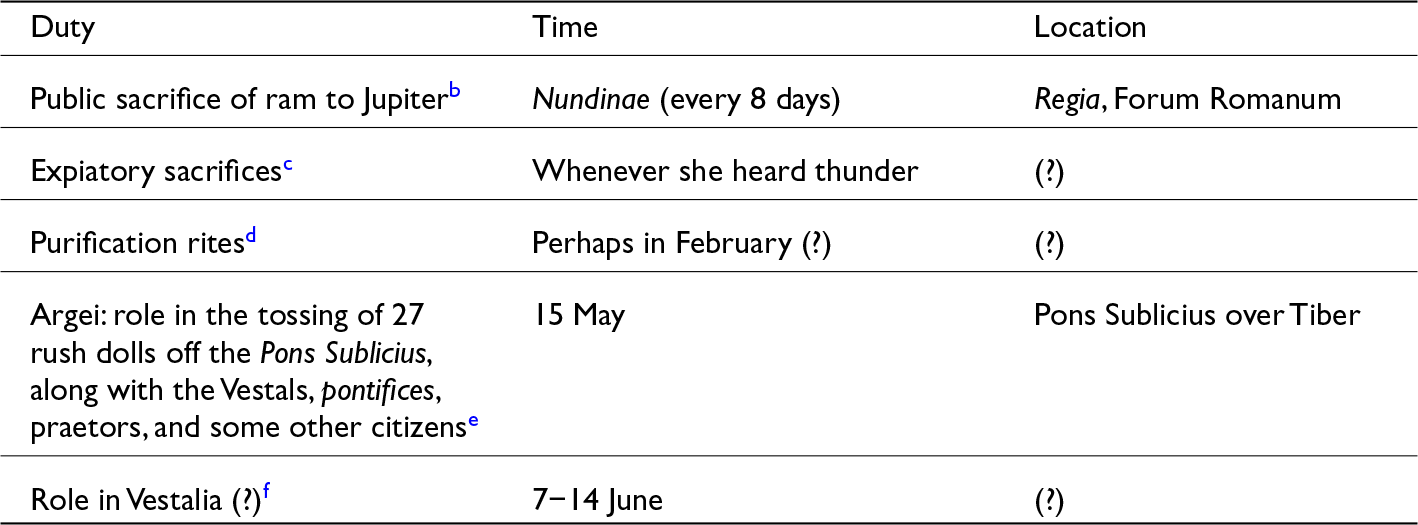

Akin to the priestesses of Vesta, the flaminica Dialis, wife of the flamen Dialis, had regular religious duties every month, for Jupiter and perhaps other gods, as detailed in Table 2.

Table 2. Flaminica Dialis and her regular religious duties (uncertainty denoted by ‘(?)’)a

Notes:

a Cf. similar table in Webb (Reference Webb2024) 55–6.

b Macrob. Sat. 1.16.30 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 27.

c Macrob. Sat. 1.16.8 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 27.

d Suggested by Ov. Fast. 2.27–8. Cf. Scullard (Reference Scullard1981) 70; Robinson (Reference Robinson2011) 76; DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 29.

e Plut. Quaest. Rom. 86 with Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 106; DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 30.

f Ov. Fast. 6.226–34 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 30–1.

The flaminica Dialis was a temporospatial conductor like the Vestals. Every month on nundinae, market days, she sacrificed a ram to Jupiter in the regia. The flaminica thus marked the passage of time in each month, and the changing rhythms of the city, heralding the arrival of farmers and craftsmen in Rome, a surge of commercial activity, and the cessation of some political meetings (perhaps after the lex Hortensia of 287 BCE).Footnote 72 Additionally, from the early first century BCE, legislation was publicised for a minimum of three successive nundinae (the trinundinum) before voting thereon (after the lex Caecilia Didia of 98 BCE), so her sacrifice could also gesture towards encroaching legal change.Footnote 73 The fact that she had to hold an expiatory sacrifice whenever she heard thunder also intimately connected her with the changing weather and seasons of the city: she was a weather reporter avant la lettre. Footnote 74 Her vibrant costume could also have temporal implications. The flaminica Dialis’ costume included: a tutulus hairstyle (hair braided into six plaits and drawn up into a bun), which was worn also by matronae; purple vittae (fillets/bands); the purple rica (a small veil); the arculum (a pomegranate wreath); the (probably) orange-yellow flammeum (a large voluminous veil), which was worn also by brides; some kind of dress, perhaps a vestis longa (long dress) or stola; a cinctus (belt); a pinea virga (pine twig); and the secespita.Footnote 75 Her costume went through some changes over the course of the year. She left her hair uncombed and unadorned and may not have worn her flammeum on certain days in March when the salii danced, in the Argei, and in the Vestalia. These days were inauspicious for weddings.Footnote 76 Her shifting appearance, visible during her regular religious activity, (ostensibly) shaped social rhythms and marital possibilities for men and women throughout Rome, and her tutulus and emblematic flammeum reminded all onlookers of both matronae and brides. As with the Vestals, her regular duties occurred in the political heart of the city, at the regia near the Temple of Vesta, and were irrevocably associated with nundinae and thus the commercial, political, and legislative rhythms of the Urbs, while her expiatory sacrifices heralded changing weather patterns and seasons.

While the evidence is slimmer than for the Vestals and flaminica Dialis, it appears the regina sacrorum, wife of the rex sacrorum, was also involved in monthly religious activity: on kalendae, first days of the month, she sacrificed a sow to Juno in the regia,Footnote 77 and she may have assisted the rex sacrorum in other activities.Footnote 78 All that is known about her costume is that it included an arculum,Footnote 79 but it may have been as recognisable as those for the aforementioned priestesses. By virtue of her sacrifices on kalendae in the regia – again in the Forum Romanum – the regina sacrorum was associated with the opening of each month.

From the little information on them that survives, it is clear the Vestals, flaminica Dialis, and regina sacrorum were prominent and visible in Rome at regular intervals throughout the year. They had daily, monthly, or annual duties in the Forum Romanum itself, and the Temple of Vesta and the regia were hubs for their religious activity, and spatially adjacent to iudicia, contiones, and the comitium. The costume of the Vestals and flaminica Dialis would have rendered them instantly recognisable, and the shifting appearance of the flaminica Dialis had significant effects on social rhythms. Presumably, the regina sacrorum and other priestesses had similarly recognisable costumes, although less evidence survives. Of note are the vital connections between Vestals and all public sacrifices, between the flaminica Dialis and nundinae, thunderstorms, and days inauspicious for weddings, and between the regina sacrorum and kalendae. The regular activity of these female religious officials, their gendered rhythms, significantly impacted or heralded other rhythms (religious, commercial, political, legislative, social) within the city.

Semper supplicat: collectives of women and their regular religious activity

Priestesses were not alone in their regular religious activity or visibility: collectives of women of differing statuses engaged in regular non-sacerdotal religious activity throughout Rome, as we saw with Aemilia and Papiria.Footnote 80 Their collective activity was often done within status groups, whose members were typically distinguished by particular status symbols.Footnote 81 Now, this activity had differing levels of inclusion and exclusion based on a woman’s intersectional identities.Footnote 82 Indeed, status differences (marital, socio-economic, and legal) were reified and made visible through such activity. While evidence for the collective religious activity of numerous status groups exists (e.g. matronae, libertinae, meretrices, ancillae), I will focus on elite patrician and plebeian matronae (married women) and ancillae (enslaved women), as temporospatial data for them is particularly rich.Footnote 83

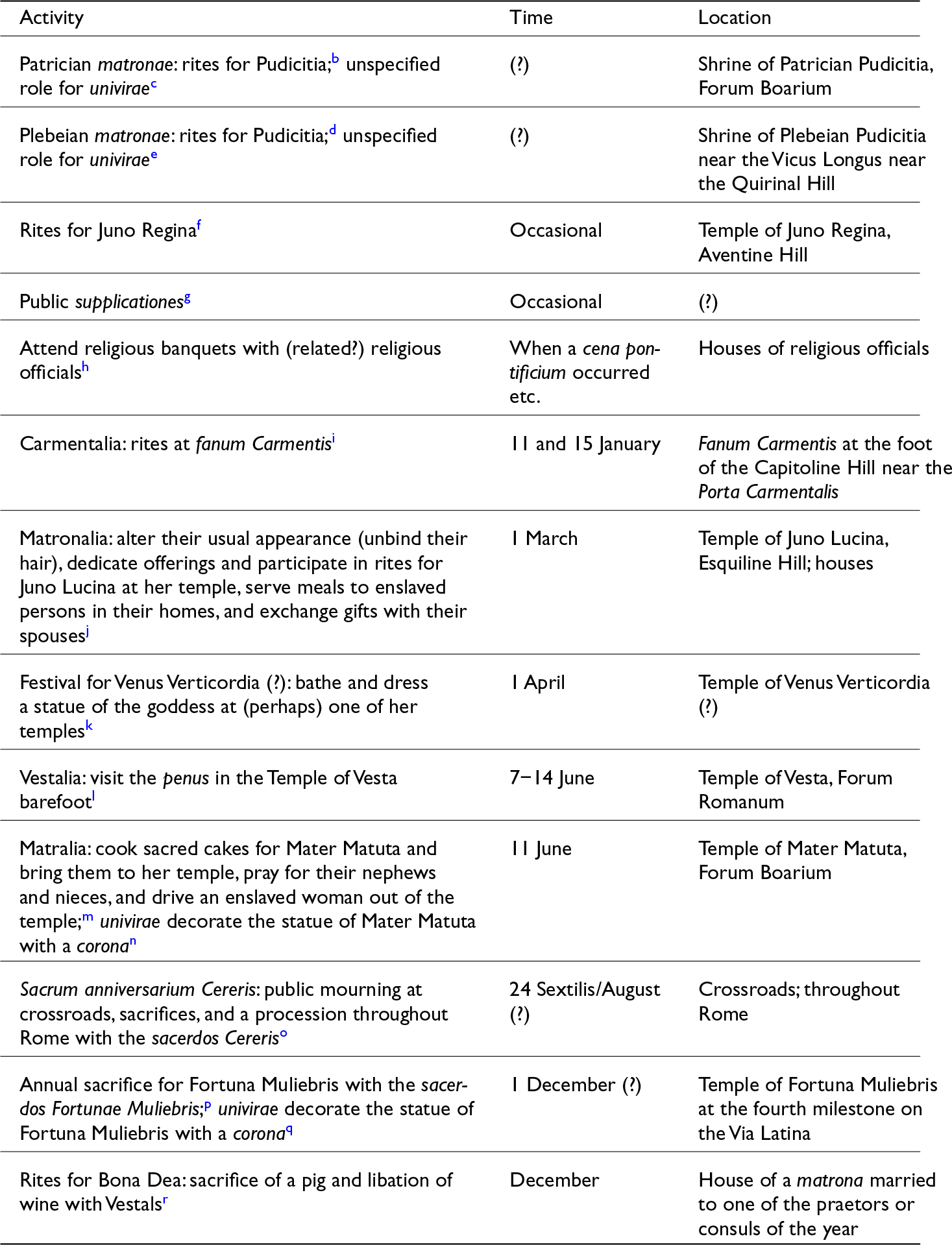

Elite matronae Footnote 84 like Aemilia and CorneliaFootnote 85 were putative members of the ordo matronarum (order of married women), a corporate body of wealthy, high-status married women.Footnote 86 These women – wealthy and visible – played central roles in the political, religious, and social life of Rome. Their opportunities for religious activity were vast. The most well-known ones are detailed in Table 3.Footnote 87

Matronal festivals punctuated the year (Carmentalia, Matronalia, Matralia), and before the start of the civil year was moved to 1 January in 153 BCE,Footnote 88 the Matronalia opened the year itself on 1 March. Indeed, this date involved several rituals of renewal, including the replacement of laurel garlands at the homes of the flamines and flaminicae, the regia, and the Temple of Vesta, and, importantly, the rekindling of the flame of Vesta in her temple.Footnote 89 Matronal religious activities were also interwoven with the religious activities of religious officials, notably in their participation in religious

Table 3. Matronae and their regular religious activity (uncertainty denoted by ‘(?)’)a

Notes:

a Cf. similar table in Webb (Reference Webb2024) 60–2.

b Livy 10.23.1–10 with Nathan (Reference Nathan and Deroux2003); Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 42–3, 139, 147–8; Webb (Reference Webb, Damon and Pieper2019b) 270.

c Livy 10.23.3–10; Festus 282L; 283L (Paulus) with Nathan (Reference Nathan and Deroux2003); Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 42–3, 139, 147–8; Webb (Reference Webb, Damon and Pieper2019b) 270.

d Livy 10.23.1–10 with Nathan (Reference Nathan and Deroux2003); Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 42–3, 139, 147–8.

e Livy 10.23.3–10; Festus 282L; 283L (Paulus) with Nathan (Reference Nathan and Deroux2003); Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 42–3, 139, 147–8; Webb (Reference Webb, Damon and Pieper2019b) 270.

f E.g. Livy 21.62.8; 22.1.18; 27.37.5–15 with Hänninen (Reference Hänninen, Setälä and Savunen1999); Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 33–7; Webb (Reference Webb, Damon and Pieper2019b) 269.

g E.g. Livy 10.23.1–2; 22.10.8; 25.12.15; 27.51.8; Macrob. Sat. 1.6.13 with Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 28–33.

h E.g. Sempronia (RE 101) who attended the aforementioned cena pontificium in c. 69 BCE with her daughter Publicia: Macrob. Sat. 3.13.11 with DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 186.

i Inscr. Ital. 13.2.1 (Fasti Antiates Maiores); 13.2.17 (Fasti Praenestini); Ov. Fast. 1.617–28; Plut. Quaest. Rom. 56; Vit. Rom. 21.1–2 with Takács (Reference Takács2008) 28–9, 31–3.

j Plaut. Mil. 690–691; Inscr. Ital. 13.2.17 (Fasti Praenestini); Ov. Fast. 3.245–258; Plut. Vit. Rom. 21.1; Suet. Vesp. 19; Festus 131L; Tert. De idol. 14.6; Ps.-Acron. ad Hor. Carm. 3.8.1; Macrob. Sat. 1.12.7; Serv. ad Aen. 8.638 with Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 57, 147; Takács (Reference Takács2008) 38, 41–2, Webb (Reference Webb, Damon and Pieper2019b) 270.

k Inscr. Ital. 13.2.17 (Fasti Praenestini); Ov. Fast. 4.133–64; Macrob. Sat. 1.12.15; Lydus, De mens. 4.65 with Pasco-Pranger (Reference Pasco-Pranger2006) 144–52; Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 148. Cf. Plut. Vit. Num. 19.2.

l Ov. Fast. 6.310–18, 395–416 with Takács (Reference Takács2008) 38, 48–9; DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 205–8.

m Inscr. Ital. 13.2.1 (Fasti Antiates Maiores); Ov. Fast. 6.473–568; Plut. Quaest. Rom. 16 with Takács (Reference Takács2008) 48–51; Webb (Reference Webb, Damon and Pieper2019b) 270.

n Tert. De monog. 17.4 with Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 147.

o Livy 22.56.4; Val. Max. 1.1.15; Plut. Vit. Fab. Max. 18.1–2; Festus 86L with Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 72, 75–9; DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 107–14.

p Dion. Hal. Ant. Rom. 8.39–56, esp. 55.2–56.4; Livy 2.40.1–13, esp. 13; Val. Max. 1.8.4; 5.2.1; Plut. De fort. Rom. 5; Vit. Cor. 33–37, esp. 37.2–3 with Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 37–46; Takács (Reference Takács2008) 23; DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 85–8; Webb (Reference Webb, Damon and Pieper2019b) 270.

q Dion. Hal. 8.56.4; Festus 282L; 283L (Paulus); Serv. Auct. ad Aen. 4.19; Tert. De monog. 17.4 with Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 147.

r Cic. Att. 1.13.3; Har. resp. 12–13, 37; Plut. Quaest. Rom. 20; Vit. Caes. 9.4–10.11; Vit. Cic. 19.4–5; 20.1–3; Cass. Dio 37.45.1–2 with Brouwer (Reference Brouwer1989) 270–1; Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 142–3; Takács (Reference Takács2008) 45–6, 101, 109–11; DiLuzio (Reference DiLuzio2016) 212–13; Webb (Reference Webb, Damon and Pieper2019b) 258; (Reference Webb, Burden-Strevens and Frolov2022) 164–5.

banquets with male and female religious officials, in their barefooted procession to the penus of the Temple of Vesta for the Vestalia, in their public mourning at crossroads, sacrifices, and procession throughout Rome with the sacerdos Cereris for the sacrum anniversarium Cereris, in their sacrifice with the sacerdos Fortunae Muliebris at the Temple of Fortuna Muliebris on the Via Latina, and in their secret December rites for Bona Dea with the Vestals in the home of a matrona married to one of the praetors or consuls for the year. These matronal rituals could be deemed vital to the stability of the community, and lapses concerned male authorities. Notably, it was the lapse in the sacrum anniversarium Cereris due to matronal mourning after Cannae in 216 BCE that prompted the Senate to issue a senatorial decree limiting this mourning to thirty days; this same mourning led to the official domestic confinement of women.Footnote 90 Matronae also played significant roles in public supplicationes, indicating that their religious movement through the city could be connected with the preservation of the community during crises.Footnote 91

Matronal religious activity could also serve to reify and visualise status differences among themselves and other women. A subgroup of matronae, the univirae, one-man-women, held special roles in religious rites, namely unspecified roles in those for Patrician and Plebeian Pudicitia, and primary roles in the Matralia and annual sacrifice for Fortuna Muliebris wherein they decorated the statues of Mater Matuta and Fortuna Muliebris with a corona. Aemilia and Cornelia were themselves patrician univirae, and feasibly held some of these special roles. Additionally, matronae served meals to enslaved persons in their homes during the Matronalia, but ritually drove out an enslaved woman from the Temple of Mater Matuta during the Matralia. So, while their activity could mark major changes in the year, involve (elite) religious officials, and serve to preserve the whole community, it also visibility facilitated the hierarchisation of society.

This hierarchisation was apparent through matronal costume, vehicles, and retinues. While individual matronae must have varied their costume for religious events, typical elements included: the tutulus like the flaminica Dialis; vittae; a palla; probably a vestis longa (long dress, and stola by first century BCE); gold jewellery (e.g. diadems, earrings, wreaths); purple and/or white clothing; and religious instruments like the canistra (baskets) and paterae (libation dishes).Footnote 92 Most strikingly, they were conveyed to many of these events in elaborate horse or mule-drawn vehicula (vehicles), including the two-wheeled carpentum for all purposes and the four-wheeled pilentum only for sacra (religious rites),Footnote 93 and were accompanied by elaborate retinues of enslaved men and women,Footnote 94 as were elite men.Footnote 95 In his acid diatribe against wealthy matronae in Plautus’ Aulularia, the old man Megadorus makes particular reference to their elaborate ivory-decorated vehicles (eburata vehicla) (Aul. 168), matronal demands for female and male enslaved attendants (ancillae, pedisequi, salutigeruli pueri), mules, muleteers (muliones), and vehicles (vehicla) (Aul. 501–2), and of the many plaustra (vehicles) in front of houses in the city (in aedibus) (Aul. 505–6). While clearly humorous hyperbole, Plautus’ inclusion of such a diatribe indicates how visible such matronal vehicles and retinues were in Rome, and how they regularly filled up urban spaces. As is evident for Aemilia and Papiria, matronal religious activity was hardly discreet. The frequency with which matronae, their vehicles, and enslaved retinues punctuated urban spaces must have significantly gendered the Urbs. We may imagine crowds of supporters and clients regularly following elite men to the Forum in the Republic, but we must also consider the matronal entourage on its way to temples and more. Akin to the flaminica Dialis, matronae also altered their appearance during certain rites by wearing garlands or unbinding their hair.Footnote 96 Status differences and hierarchies among matronae were marked out by the quality and quantity of their status symbols displayed during these rites, presumably according to a matrona’s wealth and social position, and the dictates of the ordo.Footnote 97 This is not unexpected, given the acute status consciousness of the Roman elite. The religious activity of matronae was clearly notable during festivals in January, March, June, and December, and could take them across the Aventine, Quirinal, Capitoline, and Esquiline Hills, through the Forum Boarium and Forum Romanum, and out of the Urbs to the fourth milestone of the Via Latina. The regular movement of women, vehicles, and retinues from houses to temples and shrines would have been a sight to behold.

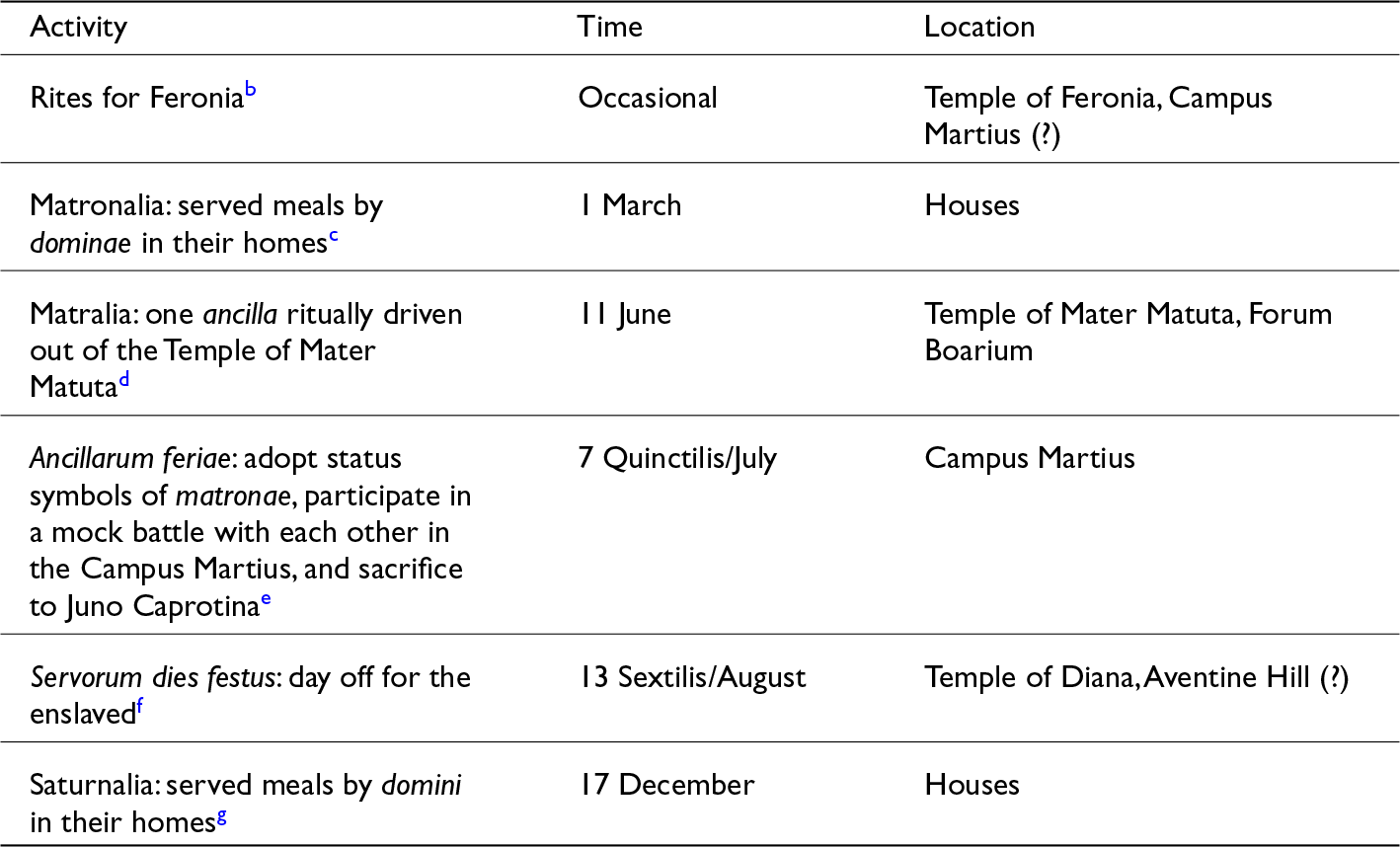

Enslaved women, ancillae, had a rich religious life as well. Not only would they accompany and support wealthy matronae like Aemilia and Papiria in their religious activity, but they had other key religious roles. They participated in various religious festivals and events, as detailed in Table 4.

Table 4. Enslaved women and their regular religious activity (uncertainty denoted by ‘(?)’)a

Notes:

a Cf. similar table in Webb (Reference Webb2024) 63.

b Suggested by CIL 6.147; Livy 22.1.18; Serv. ad Aen. 8.564.

c Macrob. Sat. 1.12.7.

d Ov. Fast. 6.473–568; Plut. Quaest. Rom. 16; Vit. Cam. 5.2 with Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 147; Takács (Reference Takács2008) 50.

e Plut. Vit. Cam. 33.2–6; Vit. Rom. 29.3–6; Macrob. Sat. 1.11.35–40 with Schultz (Reference Schultz2006) 147; Olson (Reference Olson2008) 44; Takács (Reference Takács2008) 52.

f Plut. Quaest. Rom. 100; Festus 460L.

g Assumed by Cato fr. 77 ORF 4; Acc. fr. 3 Morel; Livy 22.1.19–20; Sen. Ep. 47.14; Just. Epit. 43.1.4; Festus 432L; Macrob. Sat. 1.10.3; 1.11.1; 1.7.26; 1.24.23. Macrob. 1.12.7 suggests that only domini served enslaved people at the Saturnalia.

Later epigraphic evidence indicates that ancillae (and freedwomen) worshipped Bona Dea and held key roles as ministrae (assistants) and magistrae (officials) in her cult, presumably attesting to their presence at the Temple of Bona Dea on the Aventine Hill, and suggesting we are missing servile (and libertine) rhythms in our literary sources.Footnote 98 Given the omnipresence of slavery in the Republic, we must consider the numerous enslaved women who regularly attended religious events throughout Rome, either with their domini/ae or on their own (e.g. for the ancillarum feriae and servorum dies festus). Their clothing depended on their dominus/a and was not distinctive per se. However, while ancillae could not usually wear the status symbols of a matrona, they could be adorned richly.Footnote 99 Their gendered bodies and religious labour – visible and at the same invisible – pervaded Rome. Their annual assumption of matronal status symbols for the ancillarum feriae inverted and reified female hierarchies, and at the same time regularly reminded Rome of the religious importance of ancillae.

Visions and rhythms

This survey of female religious officials and women in Rome is in no way comprehensive. Yet, it offers an arresting vision of the regularity of collective female religious activity in Rome, and of the participation of women of highly variable roles and statuses in public religious activity in urban spaces throughout the city. The status symbols of these women or the lack thereof marked them out to onlookers. Particularly spectacular were the emblematic flaminica Dialis and the Vestals and matronae with their elaborate vehicles and entourages. But ancillae were visible too. We lack sufficient information about enslaved women to judge the extent and visibility of their activity, although the tantalising epigraphic evidence for servile involvement in the cult of Bona Dea gestures towards a far wider participation than the literary sources allow. This religious activity visualised and reified status and social hierarchies. While some of the events would have been more exclusive and less publicly visible (e.g. activity in the regia, Temple of Vesta, shrines of Pudicitia, the house of a consul or praetor’s wife, and at religious banquets), non-participants could have been aware of their occurrence and (some of their) significance and have observed participants moving to and from these spaces.Footnote 100 Ritual inclusion or exclusion was a significant, visible form of status differentiation.

Spatially, it is clear that regular religious activity could take women across Rome, especially female religious officials and matronae, to numerous temples and shrines, and through prominent public spaces like the Forum Boarium and Romanum. The Aventine Hill emerges as an important sacral location for women of various statuses, while the Caelian Hill is closely associated with Vestals, the Capitoline, Esquiline, and Quirinal Hills with matronae, the Forum Romanum with Vestals, the flaminica Dialis, regina sacrorum, and matronae, and the Pons Sublicius with Vestals and the flaminica Dialis, and the Campus Martius with ancillae. The religious activity of female religious officials and matronae in the Forum Romanum was physically proximate to key political sites and meetings, including iudicia, contiones, and the comitium, and cannot have been wholly divorced from politics.Footnote 101

Temporally, the discussed female religious activity was concentrated on specific days of the month (nundinae, kalendae) and in the months of March–June and December, although it extended beyond all of these. June, with the Vestalia and Matralia, appears to have been the most gendered month in terms of religious activity, while January, March, June, and December contained prominent matronal festivals or events. Interestingly, the seemingly high concentration of female religious activity in the warmer spring and summer months of March to June aligns with the pre-Sullan absence of consuls and their armies from Rome on campaign.Footnote 102 Conceivably, women’s religious activity in the sphere domi could have been a counterpart or complement to the concurrent male military activity in the sphere militiae.Footnote 103 The duties of female religious officials had significant implications for the commercial, legal, political, religious, and social rhythms of Rome. Significantly, all public sacrifices required the mola salsa of the Vestals, marriages depended on the appearance of the flaminica Dialis, sacrifices of the regina sacrorum and flaminica Dialis marked the opening and nundinal cycle of each month respectively, the flaminica Dialis was a living storm gauge, and the prayers of the Vestals were thought to keep Rome safe. But matronal activity was also deemed vital, hence the Senate’s concern about the lapsed rites for Ceres in 216 BCE. We have moved very far from domum servavit, lanam fecit.

Time’s place

The political scientist Joan Tronto has encouraged feminists ‘to make questions about time central to their analyses of social and political structures’ (Reference Tronto2003: 125). Almost two millennia earlier, an allusive line in the Severan Acta for the ludi saeculares of 204 CE – which famously included the Vestals, 109 matronae, and the femina princeps Julia Augusta (Julia Domna) herself – speaks to the demands of time: ‘temporis ratione poscente’ (Severan Acta LS 22 [Schnegg]). These Acta record a prayer performed on the second day of the ludi by these same women to Juno Regina before her cella at the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the Capitoline Hill,Footnote 104 wherein they asked the goddess to increase the imperium (power, empire) and maiestas (majesty) of the Roman People duelli domique (in war and peace) and for sempiterna victoria (everlasting victory) and valetudo (good health) for the Roman People (Severan Acta LS 185–186 [Schnegg]). While removed in time – but not space – from the examples in this article, the Acta attest to time’s centrality in Roman religion, to the perceived necessity of women’s religious activity, and the profound connections between women and the future security of Rome. It is this sense of futurity that ripples through Cornelia’s letter to Gaius, Cicero’s invocation of the Vestal Fonteia and her prayers in the Pro Fonteio, and Horace’s dum Capitolium | scandet cum tacita virgine pontifex (Carm. 3.30.8–9). Women were expected to continue their regular religious activity pro populo, to assure the preservation and expansion of Rome. Their gendered rhythms were not marginal, but central.

Attention to the temporospatial dimensions of female visibility in the Republic offers a serious challenge to the view of the invisible, domestically confined Roman woman. Claudia fades, and in her place appears an Aemilia and a Fonteia, or any number of female religious officials, matronae, and ancillae who regularly served the gods. We have seen that women of various roles and statuses could be visible in a wide array of urban spaces throughout Rome. Women could be distinguished and differentiated by the presence or absence of status symbols, including those for female religious officials (like Fonteia) and matronae (like Aemilia) and the conspicuous absence of most of these for ancillae. Notable are the vehicular privileges of Vestals and matronae, which would have elevated them above the average male and female citizen, physically and symbolically. Similarly, the Vestals’ lictors and the matronal entourages of enslaved people mirrored the retinues following elite men into the Forum. Women frequently moved throughout the city for regular religious activity, even in public spaces like the Forum Boarium and Forum Romanum. There were peaks of this activity on nundinae and kalendae and during the months of March to June and of December. This activity may have been a kind of religious complement domi to concurrent male military campaigns. The later prayer of the Vestals and the 110 matronae to Juno Regina in the Severan Acta reveals how female religious activity directly impacted matters duelli domique, and how futurity lay at its core.

As has become evident, women were visibly present throughout Rome, moving through an array of urban spaces – public, private, and sacred. To echo Russell’s earlier findings, there is limited evidence for spatial segregation by gender. Along with socio-economic status, already highlighted by Russell, marital and legal status, and temporality were key dimensions differentiating spatial usage and female visibility, at least as represented in our surviving literary sources. The various statuses and hierarchies among women were also visualised and reified through their religious activity, especially through exclusion or inclusion in rites. Thus, the Vestal Fonteia or elite women like Pomponia, Aemilia, and Cornelia were more likely to be visible during most religious festivals – or to be recorded as such – than ancillae. But ancillae were part of matronal entourages and were on display for the ancillarum feriae. The absence of servile rhythms in our literary sources is clear from the epigraphic evidence for their roles in the cult of Bona Dea. These and other absences have produced an incomplete vision of the extent of female visibility in urban spaces. We are left with merely a glimpse, but a transformative one.

Features of gendered spatial segregation and female visibility found in contemporary Kolkata, Mumbai, and Riyadh and in early modern Rome were apparent in Republican Rome too, particularly modes of dress, companions and attendants, respectable annual events, religion’s legitimation of women’s use of urban space, and status differentiation via status symbols. In the Urbs, dress and other status symbols varied according to a woman’s status and roles. Companions were present too: Vestals with their lictors and matronae with their enslaved entourages. As to respectability, given the perceived preservative role of women’s public religious activity, evident in the prayers of Fonteia and those to Juno Regina in the Acta, their visibility therein was not just respectable but necessary. Female domestic confinement and invisibility would thus have been highly injurious, disrupting the relationship between the Roman People and their gods, hence the temporary nature of female domestic confinement after Cannae in 216 BCE, and the limitations on matronal mourning aimed at redressing ritual lapses and returning to normalcy. Hence we must understand this activity as religious and political in practice and in its effects, and integral to the res publica.

A temporospatial frame disorients: multiple temporalities and spatialities collided in urban spaces in Republican Rome. There was no singular rhythm for female religious activity, but instead plural rhythms in interaction and conflict. Clearly, female religious officials and matronae had consonant rhythms that occasionally intersected with those for ancillae, but there were also dissonant rhythms (e.g. different sacerdotal, matronal, and servile rites). Some festivals performatively separated or inverted these rhythms (e.g. Matronalia, Matralia, and the ancillarum feriae). Yet there would have been numerous encounters and shared religious experiences across status groups, even where roles differed. The ritual products of the Vestals – suffimen and mola salsa – moved throughout the city, enmeshing the Vestals with the People, other religious officials, rituals, and domestic and sacred spaces, and bringing harmony to a seemingly chaotic calendar. Collectively, the Vestals, flaminica Dialis, and regina sacrorum were temporospatial conductors: they directed the rhythms of the city. Similarly, matronal religious movement protected the community. In consonant and dissonant rhythms, women and their bodies were regularly inscribed into the city. One strain emerges forcefully from the sacerdotal and matronal rhythms in particular: in women’s hands, frequently and visibly extended to the gods, lay the preservation of Rome’s future.

Time’s place, then, appears pivotal. By attending to the polychronicity and polyrhythmicity of ancient cities, we can discern with fresh eyes the times when, and ways in which, various peoples shaped the spaces around them. This article charts one possible temporospatial re-visioning of female visibility and religion in urban spaces, and productively moves women out of the domus and towards the shrines and temples. But much more could be done. What would a re-visioned and temporalised domus look like? A reconsideration of women’s involvement in salutationes, consilia, and other meetings in the domus? Of their time in the atrium? Harriet Flower and Susan Treggiari have already shown how central elite women were to consilia in the Late Republic, and how political the domus could be.Footnote 105 Perhaps it is worth breaking down the very idea of female domesticity qua private in the Republic.Footnote 106

Acknowledgements

My research was funded by the Swedish Research Council (2019-06370; 2022-02444). Many thanks to Maxine Lewis and Amy Russell for their invaluable editorial comments, to the anonymous reviewers, and to Lea Beness, Harriet Flower, Tom Hillard, Josiah Osgood, Irene Selsvold, and Kathryn Welch for their reflections on Webb (Reference Webb2024) and this article. NB: Webb (Reference Webb2024) contains some similar data, arguments, and findings but has different foci: here the focus is on the use and value of an intersectional and temporospatial analysis.