In his 1849 annual report to the Brazilian parliament, Justice Minister Eusébio de Queiroz Mattoso da Camara observed that most of the workers employed in the construction of Rio de Janeiro's penitentiary, the Casa de Correção, were slaves, and he concluded that it would be less expensive for the government to hire free laborers to complete it. Queiroz's main concern was that, after nearly sixteen years of construction, the Casa de Correção was only halfway done. Only one of its planned four pavilions was near completion. Meanwhile, Rio's civil jail, the Aljube, stood as a “shameful anachronism” in the Brazilian capital, where convicted criminals shared cells with other detainees awaiting formal arraignment.Footnote 1 Queiroz emphasized the necessity to inaugurate the penitentiary to modernize Rio's penal system.

This article analyzes the utilization of a motley crew of slaves, convicts, liberated Africans, and free laborers to build the Casa de Correção between 1833 and 1850. It probes a crucial nexus point centered on Rio's significance as Brazil's preeminent commercial port city, where transformations in the labor regimes of the Atlantic from unfree to free labor reverberated. It argues that the deployment of slaves, convicts, liberated Africans, and unfree workers to build the Casa de Correção demonstrates that until the first half of the nineteenth century the boundaries between free and unfree labor were very porous in the Brazilian capital. The significance of slaves in the city's population and the availability of pauperized legally free workers allowed the authorities to constantly combine free and unfree laborers to clean Rio's streets and to build public infrastructures associated with social control and progress, such as repairing public fountains, aqueducts, and the seawall in the harbor. The permutation of labor arrangements in public works allowed legally free and enslaved laborers to interact daily in the capital. The abolition of the slave trade in 1850 engendered a politics to transform the Casa de Correção into a site for re-articulating the geography of free and unfree labor in Rio through a hardening of the distinctions between salaried slaves and legally free wage workers. Brazilian authorities intervened over time to restrict bonded labor to plantation agriculture and maintained various forms of free and unfree labor, including contract labor, apprenticeship, and prison reformatory work, on Brazil's coastline, particularly in Rio, the capital.

The penitentiary belongs to Brazil's postcolonial nation-building process, which rested on concretizing the country's aspiration to modernity through prison reforms and engendering a law-abiding free working-class citizenry to abate the dependency on slave labor.Footnote 2 In this way, Brazil participated in two interrelated ideological shifts in the Atlantic World that restricted freedom for unruly and criminal social elements of the poor through confinement while advocating the gradual abolition of slavery.Footnote 3 As Clare Anderson's contribution to this Special Issue argues, the abolition of slavery in the Atlantic engendered the spread of penal transportation and convictism in the Indian Ocean as part of the “circuit of repression and coerced labor extraction” that defined the global economy.Footnote 4 That Brazil was a major recipient of African slaves through the traffic rendered its reception and implementation of penal reform ideas and anti-slavery problematic. Brazilian port cities, foremost Rio de Janeiro, became the experimenting ground for the deployment of these concepts because of their significance as international ports of trade and urban centers with a cosmopolitan working class that included African slaves, free people of color, and sailors of multinational origins, foreign immigrants, soldiers, and skilled artisans. Rio shared this pattern with other port cities in the Americas and seaports in the Atlantic and Indian Ocean.Footnote 5

As an Atlantic port city, Rio de Janeiro connected Brazil's hinterland with commercial networks that integrated the African coast to the Americas through the slave trade and to Europe through export-driven agriculture (Figure 1). The city was in the center of the transformation of slavery in the Atlantic, a process that Dale Tomich conceptualized as a Second Slavery, evidenced by its “partial relocation” and the “invention of new forms of unfree labor” that saw the institution gaining ground in Brazil, Cuba, and the US South while disintegrating in the British and French Caribbean in the nineteenth century.Footnote 6 Between 1831 and 1855, an estimated 718,000 slaves entered Brazil, or equivalent to twenty per cent of the total slave traffic during its three centuries of existence.Footnote 7 The majority of the enslaved were destined to work in the prosperous coffee plantations of Brazil's central-south region, notably the Vale do Paraiba, or Paraiba Valley. The increased volume of the traffic through Rio transformed the city demographically, but also created a local economy around the port that provided the goods and services that transient sailors depended upon for survival. As Melina Teubner's contribution to this Special Issue highlights, food-selling women played an important role in the informal economy around Rio's port by feeding the multitude of workers, sailors, waged slaves, and fugitives who worked in the city or aboard the slave ships that tied Rio to other domestic seaports, the African coast, and Europe. Mule traders from Rio's hinterland depended on street commerce to sustain them while passing through the capital.Footnote 8 Police surveillance was particularly necessary to control the circulation of slaves and freedmen in the city, and the availability of prisons was a fundamental aspect of regulating Rio's economic and social life.Footnote 9 Following the abolition of the traffic in 1850, the internal slave trade relocated slaves from north-eastern sugar plantations to the coffee economy of the central-south region. Rio served as an important corridor from whence these slaves were distributed to the Paraiba Valley.Footnote 10

Figure 1. Some of the major port cities with which Rio de Janeiro was linked in the nineteenth century through the slave trade and commerce in colonial products.

The Casa de Correção was fundamental in regulating this process, whether through the imprisonment and flogging of fugitive slaves, the custody of enslaved men and women in the process of being sold out of the city, or the detention of vagrants and beggars who challenged the new geography of labor unfolding.Footnote 11 Most of Rio's slaves originated from Angola and the Congo in the nineteenth-century and the Casa de Correção housed a microcosm of that population as a result of the prohibition of the illegal slave trade. In early July 1834, the Casa de Correção received 249 emancipated Africans from the Duquesa de Bragança, and 118 liberated Africans from the Patacho Santo Antonio, two vessels which were condemned in July 1834. The police also sent illegally enslaved Africans from land seizures to the prison. Slaves aboard the Santo Antonio were all identified as from Gabon in Congo while the Duquesa de Bragança's Africans were a mixed ethnicity from Benguella and Angola. As a result, the Africans did not experience their confinement aboard the ship and the Casa de Correção in isolation, and could converse among themselves and with other slaves.

THE POLITICS OF BUILDING THE PENITENTIARY IN POSTCOLONIAL BRAZIL

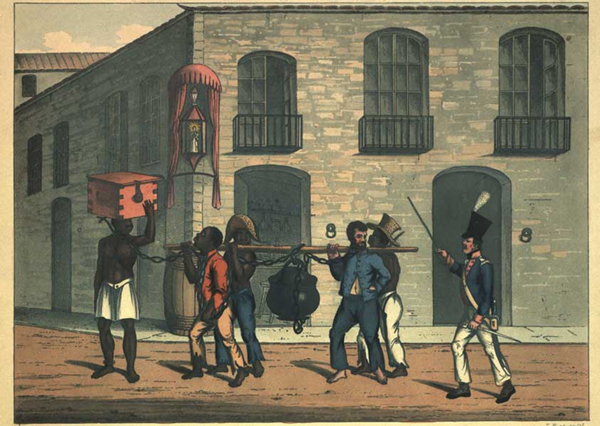

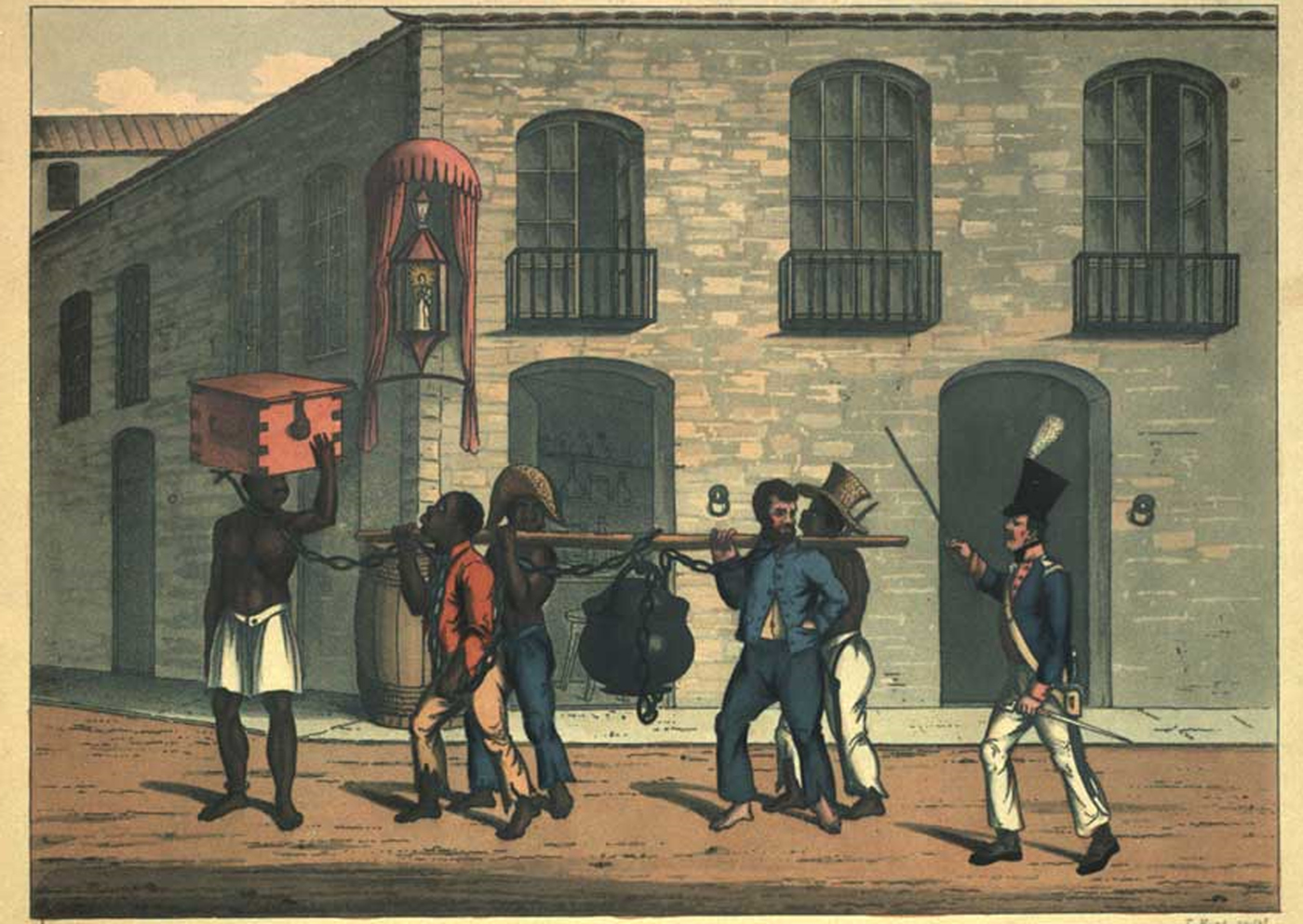

The impetus to build the Casa de Correção originated from Brazil's independence from Portugal in 1822 under a constitutional monarchy, followed by the adoption of a criminal code in 1830. The code called for prisons to be “hygienic, secure, and well-organized”, and established confinement as punishment for most crimes through “prison with work”, “simple imprisonment”, and galés, or hard labor in public works in fetters (Figure 2).Footnote 12 “Prison with work” reflected the influence of liberal penal ideas, which hinged on the view that confinement was a site to reform criminals through compulsory labor and silence. Through its adoption, Brazil embraced a positive view of work as having the capacity to reform criminals into citizens.

Figure 2. T. Hunt, “Criminals Carrying Provisions to the Prison”, London, 1822.

Biblioteca Nacional, Rio de Janeiro, available at: http://acervo.bndigital.bn.br/sophia/index.asp?codigo_sophia=2807; last accessed 26 October 2018.

Subsequent decrees and police regulations empowered local justices of the peace to investigate and issue sentences for “public crimes” such as vagrancy and the unlicensed carrying of pistols, daggers, and other perforating instruments. Participating in riots or the illegal assembly of groups of five or more could lead to a “prison with work” sentence of one to six months.Footnote 13 Justices of the peace such as João José da Cunha of the Sacramento district utilized this new authority to call on lawful citizens to aid the police to identify “vagrants and idlers” who had broken into various houses of the parish in 1832.Footnote 14 A year earlier, in 1831, a deputy justice of the peace calmed the public about the lack of repression against vagrants by assuring them that he had recently sentenced “eleven vagrants to 24 days of prison with labor” at the navy yard. He had also previously sent ten individuals to the army arsenal after they “approached him alleging that they could not find an occupation”.Footnote 15 “Prison with labor” sentences were applied to convicts who disturbed the peace, constituted a threat to private property, and committed homicide. They were individuals of free legal status in Brazilian society. For example, José Antonio da Conceição, born in Lisbon, was punished with two years and a month of “prison with labor” in 1838 for stealing slaves.Footnote 16 By contrast, Joaquim Mina, a West African slave from the Mina coast, was sentenced to 400 lashes for a similar offence.Footnote 17

Before the completion of the penitentiary, individuals who were sentenced to “prison with work” joined the pool of unfree workers whose labor power was utilized by public institutions in small- and large-scale work associated with modernizing the city, such as road building, constructing the seawall at Snakes Island, or repairing municipal fountains. The ethnic and racial profile of this dangerous class reflected Rio's importance as an international port city with slave and legally free workers of color as well as European immigrants. In late December 1833, a group of prisoners who escaped from their work site at the navy arsenal with the help of a prison guard included three Brazilians, a freed person of color – pardo – chastised with hard labor in perpetuity for murder, two other pardos – one an ex-soldier convicted of desertion and another sentenced for robbery – and a thirty-six-year-old Prussian skilled in saddlery who was sentenced to “prison with labor”. They were all reduced to unfreedom, despite their differing legal status outside of confinement and coerced labor.

Hard-labor sentences were designed to chastise slave criminals, especially those who committed mastercide or fomented rebellion.Footnote 18 Galés – hard labor in public works in fetters – also applied to free people who committed property crimes such as slave thefts and counterfeiting, activities which attacked the economic basis of society. In 1833, a list of galé convicts who had completed their sentences included three free individuals, one of whom was punished for theft. Another convict was chastised with two years of galés for stealing slaves, while the last one was punished to four years of hard labor for highway robbery.Footnote 19 In February 1834, from among ten galé convicts who had escaped from the dungeon at Snakes Island, four were white, including two Portuguese immigrants, two were pardos, and one of the fugitives was a West Central African slave named João Benguella, who had been condemned to ten years of forced labor at the dike for homicide.Footnote 20 The convicts originated from the north-east and south-east of Brazil. Soldiers like Manoel Gomes Pimenta, a white man from north-east Brazil, and Paulino dos Santos, a free person of color from Rio, often found themselves among galé convicts for desertion and insubordination in the army or the navy, which were important social control institutions that thrived on the recruitment of coerced workers, especially free people of color.Footnote 21 Galé inmates were therefore a heterogeneous group that included mostly slaves but also some free offenders. They included Brazilian, European, and African-born, as well as legally enslaved and free persons. Convicts worked manacled to one another at their ankle or neck, which was the condition under which chained gangs of slaves carried water to various venues in Rio. If one were not a slave, to be chastised to galés and to “prison with work” before the advent of the penitentiary constituted a reduction to the status of a judicial slave.

URBAN SLAVERY AND PRISON LABOR IN NINETEENTH-CENTURY RIO

The prison population reflected Rio's multi-ethnic inhabitants and its significance as Brazil's preeminent commercial seaport in the nineteenth century. With a significant urban slave population and an extensive harbor that linked its agrarian hinterland to European commercial centers and the African Slave Coast, Rio was a city marked by the interaction of slave and free workers. As other port cities in the Atlantic and Indian Ocean, Rio had been “a crucial component of European expansion” since the sixteenth century and a “fulcrum of European activity” by the nineteenth century.Footnote 22 Its economic life depended on the manual labor performed by thousands of Brazilian and African slaves, enslaved female domestic workers, laundresses, cooks, sailors, Portuguese cashiers, porters as well as white civil servants, impoverished policemen, and soldiers.

Rio became a center of the Lusophone Empire between 1763 and 1808, when gold and diamond mines were discovered in its interior and the Portuguese crown relocated to Brazil. Thousands of impoverished Portuguese immigrants and Brazilian north-easterners flocked to the mining region through Rio's harbor.Footnote 23 The volume of the traffic increased, resulting in the slave population as a proportion of the total population increasing from 34.6 per cent in 1799 to 45.6 per cent in 1821 (Table 1). Fifty per cent of enslaved Africans sold to Brazil between 1808 and 1821 passed through Rio's port.Footnote 24 In 1808, an estimated 15,000 Portuguese courtiers migrated to the city, which created a housing crisis and a boom in construction. The crown liberated Rio's port for free trade, leading to hundreds of British commercial agents establishing residences in the city, along with Frenchmen and Germans. French tailors owned fashionable boutiques on Ouvidor Street. Portuguese artisans and small businessmen established their shops in St Peter's Street.Footnote 25 Much more diluted in the population were the Germans, Chinese, Prussians, South Americans, and North Americans who passed through the city. Foreigners represented 9.5 per cent of the city's population by 1838, which undercounted their presence in the city. Historian Mary Karasch estimated that Rio's slaves likely represented 56.7 per cent of the city's total population in 1834 and 51.6 per cent in 1838 based on studies of estimated numbers of slaves owned per household.Footnote 26 The drop in the slave population in 1849 reflected the increase in the number of European immigrants in the city. The city's diverse population was well represented in jail records, and after 1850 the number of foreigners in the central police station jail regularly surpassed the number of Brazilian nationals there.Footnote 27

Table 1. Composition of the population of Rio de Janeiro, 1799–1849 (%).

Sources: Karasch, Slave Life in Rio de Janeiro, pp. 62–66, and Yedda Linhares and Barbara Lévy, “Aspectors da história demográfica e social do Rio de Janeiro (1808–1889)”, in L'Histoire Quantitative du Brésil de 1800 à 1930. Colloques Internationaux du Centre National de la Recherche Scientifique, no. 543 (Paris, 1973), pp. 128–130. The 1821 censuses included free people and freed persons as a single group. The 1834 and 1838 censuses undercounted the city's slave population as well as the number of foreigners.

Rio's slaves operated in a wage labor market that was inserted in a slave society. There were two kinds of wage-earning slaves in the city: slaves-for-hire – escravos ao ganho – who, in agreement with their owner, sold their services after fulfilling their obligation to their masters, to whom they paid an agreed portion of their earnings, and leased slaves – escravo de aluguel – whose services were rented out by their owners to an employer.Footnote 28 Slaves-for-hire worked on short-term commissions and exerted more control over their meager earnings, while leased slaves did not directly participate in the exchange between their employers and their owner. Slaves toiled as seamstresses, porters, peddlers, barbers, carpenters, masons, and were the bedrock of Rio's economic life. Many leased slaves were owned or hired by foreign skilled artisans, who possessed twenty per cent of the city's slave population.Footnote 29 Rio's slaves were ethnically diverse and divided between Brazilian-born slaves known as Crioulo and African-born slaves, who represented sixty-five per cent of the urban slave population. The majority originated from West Central Africa.Footnote 30

Rio also disposed of a substantial free poor class who constituted a “reserve labor force”.Footnote 31 They were a subset of the “Atlantic proletariat”, which were temporarily employed and often did the work of slaves.Footnote 32 The city's free poor were manumitted slaves, mixed-race descendants of Portuguese and Africans, and poor Portuguese immigrants. In a racially stratified society where landownership and slaveholding were markers of wealth and status, the free poor, especially those who did not possess at least one slave, remained on the margins of society.Footnote 33 Liberal reformers identified them as the object of penal discipline to engender a law-abiding working class. Known as the desprotegidos or the dishonorable poor, they were targeted by the police for recruitment in the navy and army for vagrancy and disorder because of their vulnerable position in the social hierarchy that unfolded from an economy based on slave labor. This was part of the apparatus of security and racialization that characterized port cities, as Brandon has argued in his studies on Paramaribo.Footnote 34

In 1833, sixty galé convicts were relocated from the São José fortress at Snakes Island to Catumby to work on the construction of the Casa de Correção. Given the racial, ethnic, regional, and national diversity of convicts in the 1830s, the sixty convicts were probably a very heterogeneous group that included mostly slaves but also free people of color, poor white Brazilians, and foreigners.Footnote 35 In the following years, they were joined by prisoners from other worksites. In February 1834, the Director of the Navy Arsenal dispatched convict José da Silva to be employed “in the construction of the Casa de Correção”.Footnote 36 It is quite possible that the official was disposing of a troublesome inmate by relocating da Silva from the navy yard in Rio's harbor to Catumby, which was situated at the edge of the city. The convicts would have walked for one hour, chained to one another and under heavy supervision, from the harbor to Catumby. The government had purchased a farm in Catumby that included a two-storied house that served as a jail for the convicts. Catumby was selected owing to its relative distance from the city center and its location at the foot of a hill – Catumby Mountain – which the authorities believed would provide the stone and gravel to build the prison.Footnote 37

The utilization of enslaved and legally free prisoners to build the Casa de Correção strategically relocated convicts from Rio's commercial and artisan-owned shop area, where they routinely evaded their dungeons, to the rustic Catumby region. Rio's prisons were notoriously overcrowded and galé convicts were kept aboard hulks in the city's harbor. Aside from the dungeon at Snakes Island and the prison ships, there were three other main jails in the capital: the Aljube, a civil prison; the Calabouço, a dungeon for slaves in custody; and a reformed prison on Santa Barbara Island (Figure 3).

Figure 3. The evolution of Rio de Janeiro from the port region towards its hinterland, with the location of various prison sites.

The city's prisons were entrenched in its export economy and in the web of power relations and a social hierarchy that was deeply connected to the plantation and mining economy of its hinterland. Snakes Island, where a dungeon filled with galé convicts was located, served as a station for commercial boats and the prison-hulks.Footnote 38 The Calabouço was situated in a fortress atop Castello Hill at the entrance to the city. The Aljube was imbedded in Rio's slave market in Santa Rita parish in the Valongo, where African slaves first set foot on land after the traumatic voyage across the Atlantic. The Aljube was located in the center of Rio's slave markets, which until 1831 was at Praia do Valongo. The streets and alleys that spread from the harbor were under close police surveillance because of the economic activities that abounded around the port. Before the construction of the Casa de Correção (in Rua do Conde, Catumby Hill on the map, Figure 3) prisoners were held at the Aljube, the Calabouço, the São José Fortress at Snakes Island, and the Santa Barbara jail located in the Santa Barbara island off of the Morro da Saúde. The Navy Arsenal near the customhouse was an important cog in the carceral ring around the port because of its use of conscripted labor, mostly free people of color and liberated Africans. In the 1830s, there were at least two prison hulks – pressiganga – filled with galé convicts, named the Animo Grande and the Não Pedro II. Although the traffic had been abolished in 1831, there were still warehouses in the Valongo where enslaved African men, women, and children were stored before they were sold to the interior. Walking through the straight and narrow streets that extended from the harbor to Catumby and beyond, a foreign visitor to Rio would “continuously encounter convoys of mules which intersected and succeeded one another”.Footnote 39 These chains of people and commodities linked the capital to the provinces of Minas Gerais, São Paulo, Goyaz, and Curitiba among others.

The government deployed the need for compulsory labor at the penitentiary to reform its most decrepit dungeons by relieving them of excess residents. Galé inmates were not only sent to work in Catumby, many had their sentences commuted to banishment and were transported to Fernando de Noronha, a penal colony in the north-east, which a mixed slave and legally free convict workforce had built.Footnote 40 In December 1834, the African-born slave convicts José Moçambique and João Congo were included in a list of ten prisoners whose sentence to galé was commuted to banishment to Fernando de Noronha. The decision aimed to reduce the “great number of inmates who had accumulated in Rio's prisons at great cost to public finances”.Footnote 41 In June 1834, the African-born slaves João Cabinda and José Grande, each sentenced to twenty years of galés, were sent to the Casa de Correção by Rio's Police Chief, along with João Feitor, who had been condemned to thirteen years of “prison with labor”.Footnote 42 On 25 June 1834, Eusébio de Queiroz, who served as Police Chief, requested the Commander of the Animo Grande, a prison hulk, to send twenty-four galé convicts to work at the Casa de Correção.Footnote 43

Inmates from the city's jails preferred to be sent to the Casa de Correção because conditions there were much better than at the Aljube or at Santa Barbara Island, which was too distant from the city and afforded them little contact with the mainland, and especially few opportunities for escape. Preference was given to detainees skilled in masonry, carpentry, ditch digging, and others who had demonstrated good behavior. The government considered paying select exemplary inmates a daily wage as an incentive and as a means of control. Other punitive forms of control were necessary. Galés and criminals sentenced to “prison with labor” worked in chains, which controversially blurred the lines between the two groups. The police dispatched prison guards to prevent escapes.Footnote 44 Still, it was not impossible to escape the Casa de Correção. In 1834, Luciano Lira, a convict of free legal status, fled from the worksite.Footnote 45

The relocation of Rio's inmates to the penitentiary also applied to enslaved detainees in custody at the Calabouço. In 1837, 188 slaves in custody were transferred from the Calabouço at Castello Hill to the Casa de Correção, where they were incarcerated in a new reformed jail, also called Calabouço.Footnote 46 In June 1830, the justice of the peace of Lagoa, a rural parish to the south of the harbor, ordered the detention of the slave woman Theodora at the Calabouço after she was arrested on a farm near Rodrigo de Freitas Lake.Footnote 47 Slave owners regularly brought their bondsmen to the Calabouço to be flogged for a fee and detained as punishment for disobedience, routine flights, and rebellion.Footnote 48

Slaveholders utilized the Calabouço, before and after its transfer to the Casa de Correção, as a warehouse to contain and correct unruly slaves while negotiating for their sale outside of Rio. It was common to find notices in the city's gazette advertising the sale of slaves like Joaquim, an African from Benguella in West Central Africa, which encouraged interested buyers to visit the Calabouço to inspect them. Joaquim was a skilled blacksmith and compelled his owner to sell him by “refusing to work”.Footnote 49 Joaquim Antonio Insua, a petty slave owner who lived in Rio's Valongo, advertised the sale of his Brazilian-born slave, Manoel, a carpenter, under the condition that he was sold “outside of the province”.Footnote 50

Owners of Calabouço slaves often resided in the city's commercial districts in streets such as Rua do Carmo, where Januario, an enslaved master goldsmith, lived; Castello Street, where the owner of a slave identified as a “good cook” resided; or Fishermen's Street, where the owner of a master tailor, a Brazilian-born slave, resided.Footnote 51 These notices identified the enslaved by skills, such as cooks, master gilder, apprentice tailors, master tailors, sailors, master goldsmith, carpenters, and barbers. A substantial segment of enslaved detainees were therefore skilled urban slaves. The relocation of the Calabouço to Catumby gave the Casa de Correção access to an enslaved workforce that comprised skilled artisans and semi-skilled slaves, including female slave detainees who worked as cooks and washerwomen. Slave detainees surpassed the number of convicts because they originated from routine police actions and from slave owners who confined them at the Calabouço. The convict population was divided into two groups: minors – fourteen years or younger – who were under a correctional regime for vagrancy-related charges, and adult criminals.

The government also deployed the Casa de Correção's construction to reform vagrants and beggars, including delinquent minors under the authority of local justices of the peace. In 1831, the Aurora Fluminense commented on a communication from the navy arsenal for mechanics and other skilled workers to present themselves at the armory in order to be hired. The invitation was especially extended to “free or emancipated (liberto) officer technicians”, which suggests that free people of color were particularly targeted as the recipients of this policy.Footnote 52 The program “would produce good results by decreasing the number of vagrants who passed through the streets” by disciplining them in the “habit of work”.Footnote 53 In 1836, the legislature discussed how to liberate the streets from the “high number of beggars” who harassed residents and considered employing them in their home so that they could provide for themselves.Footnote 54 A citizen's letter emphasized that small shops and vendors’ stalls maintained by slaves and which specialized in selling groceries and cooked food “provided to the lower classes their means of honest subsistence”. However, these places of commerce were unregulated and constituted points of conglomeration for “idlers, drunkards, thieves, gamblers, and ruffians of all caste”.Footnote 55 These preoccupations with vagrancy coalesced in a vigorous police campaign in 1838 to deliver the city of the “infestation” of vagrants, beggars, and their “harmful effects” on society.Footnote 56 The police paid duty officers for each pauper brought to the Casa de Correção, where they were compelled to work on the construction of the prison. A total of 170 vagrants were sent to work at the penitentiary; forty others were sent to the navy. The policy backfired because the Casa de Correção was unable to absorb this surplus labor, which tasked the government's ability to control the prison population.Footnote 57

CONFINEMENT AND THE CHANGING LABOR REGIME OF THE ATLANTIC

What made the labor arrangement at the Casa de Correção novel compared with previous employment practices in Brazil was its utilization of liberated Africans as involuntary “apprentice” laborers and their distribution to other public institutions and private employers. Convict laborers were an important pillar in Portuguese colonial expansion in Asia, Africa, and Brazil.Footnote 58 European empires traditionally relieved the streets of the burden that a free flowing, unattached vagrant population represented in metropolitan and colonial port cities.Footnote 59 In the Lusophone world, colonial armies and troop regiments were filled with the unattached and unprotected poor, who expanded the colonial and postcolonial frontier in Brazil. The Casa de Correção's labor scheme therefore constituted an extension of the traditional imperial practice of dragooning unfree people – through the justice system and enslavement – into public work tasks around Rio. The prison's labor scheme was a response to the ripple effects of the changing labor regimes of the Atlantic, from slavery to free labor, by contracting the labor power of liberated Africans for the prison's own use and consigning this commodity to privileged landowners and other public institutions.

“Liberated Africans”, known as emancipados in Cuba and “recaptives” in other Atlantic shores, refers to the estimated 11,000 men, women, and children that the Mixed Commission Court in Rio emancipated between 1821 and 1845.Footnote 60 A subset of that population, 150 on average, was employed at the Casa de Correção after 1834, when the government authorized the penitentiary to utilize liberated Africans “giving preference to those who were already learning a trade and had shown a love of work”.Footnote 61 As salaried apprentice laborers, liberated Africans represented a significant segment of the prison's workers. Their wages were paid to the government, which acted as a corporate employer when it consigned emancipated Africans to public institutions and to slaveholders. Liberated Africans who worked at the Casa de Correção received a vintém, or ten per cent of their wage, which they could use to buy tobacco and other necessities. The government retained the remainder of their wage for food, clothing, and the cost of confinement. Liberated Africans were also employed at the city's Our Lady of Mercy Charity, the telegraph service, the ironsmith factory in São Paulo province, the light company, and a gunpowder workshop. They were utilized in the repair of Rio's roads, aqueducts, and public fountains, where they worked in a racially mixed workforce of salaried enslaved laborers and legally free workers with skills in carpentry, ditch digging, and masonry. After 1850 liberated Africans employed at the Casa de Correção laid the railroad tracks that connected Rio's harbor to the rural parishes where coffee plantations thrived. The new railroad system symbolized the city's modernization and booming coffee economy.

The legal status of liberated Africans was circumscribed by British and Brazilian laws and the anti-slavery discourse about freedom that linked the Atlantic and the Indian Ocean in the politics of labor exploitation that was inherent to the process of the formation and consolidation of capitalism in the nineteenth century.Footnote 62 Evelyn Jennings's study of road building in nineteenth-century Havana in this volume demonstrates the local and diasporic connections among various systems of regulating unfree labor through apprenticeship which articulated both a liberating labor policy and a recasting of slavery.Footnote 63 The Anglo-Portuguese Treaty of 28 July 1817 instituted the Mixed Commission Court on the African coast and in Rio to adjudicate the legality of slave vessels. The court provided certificates of emancipation to enslaved Africans captured aboard slave vessels and turned the freedmen to local authorities for guardianship to be “employed as servants or free laborers” for fourteen years before being declared “fully free”.Footnote 64 The Portuguese crown promulgated a royal decree in 1818 that incorporated into Brazilian laws the guidelines of the Mixed Commission and clarified the legal position of liberated Africans in the slave society, including the fourteen-year apprenticeship requirement.Footnote 65

Port cities like Rio were crucial nodal points for articulating and circumscribing the meaning of freedom for liberated Africans due to their significance as doorways for enslaved Africans from the slave trade and the residence of the Mixed Commission courts. The introduction of coffee in the Paraiba Valley had a profound effect on Rio's economy and demography. Coffee cultivation required little technological innovation, but like sugar it thrived on enslaved labor. Enslaved Africans fueled coffee's ascent in Brazil's economy between 1831 and 1850 (Figure 4).Footnote 66 Coffee cultivation gave rise to a powerful slaveholding aristocracy whose influence extended to all levels of the Brazilian administrative state, especially after 1837, when the rise to power of the Conservative Party marked the end of the liberal era (1831–1837).Footnote 67

Figure 4. Brazilian Coffee Exports and the Traffic in Slaves, 1822–1850.

Corrected statistics for the volume of commodity exports from Brazil are taken from Christopher David Absell, “Brazilian Export Growth and Divergence in the Tropics during the Nineteenth-Century”, IFCS – Working Papers in Economic History, WH, May 2015, pp. 1–41. Data on the volume of the slave trade originate from the Trans-Atlantic Slave Trade Database, available at: ; last accessed 26 October 2018.

Eusébio de Queiroz, who called for the discontinuation of slave labor at the Casa de Correção in 1849, was an influential member of the Conservative Party. He was well connected to the coffee elite through marriage and was directly in charge of the allocation of “liberated Africans” as free coerced laborers to socially privileged individuals. Queiroz was at the helm of the policy to confine and compel vagrants to work in city projects. He implemented the policy that led to the routine incarceration of free people of color suspected of being fugitive slaves at the Calabouço.Footnote 68 Queiroz's role in the distribution of liberated Africans was an extension of the conservative strategy to identify people of color – enslaved and free – as slaves unless proven free, but also part of a broader process of statecraft that involved establishing the rule of law in the policing of the illegal slave trade.Footnote 69 Coffee's rise as Brazil's chief agrarian export corresponded with the expansion of the illegal traffic and a crucial period of postcolonial state formation. A 7 November 1831 law abolished the traffic, branded traffickers as pirates, and criminalized their activities. The law recommended repatriating liberated Africans to their homeland, which represented an important legal departure from British abolitionist policies because it did not envision incorporating emancipated Africans as “apprentices of freedom” in Brazilian society.Footnote 70 Liberal legislators who supported the 1831 law viewed the slave trade as a problem for postcolonial nation-building and advocated slavery's gradual abolition while building the penitentiary to discipline the free poor into workers. They viewed the entry of new Africans as introducing an “internal enemy” into Brazil that was incompatible with progress.Footnote 71

Figure 5. Slaves, Convicts, Liberated Africans, and Skilled Workers at the Casa de Correção, 1835–1840.

Compiled from the monthly reports on the prison's workforce. “Relatório dos Trabalhadores e Operários Empregados nas Obras da Casa de Correção”, in Diário do Rio de Janeiro, O Despertador, Correio Official, 1835 – 1840.

The general consensus among liberals and conservatives was that Brazil constituted a territory of slavery for Africans.Footnote 72 At best, radical politicians believed that it was dangerous for liberated Africans to remain in Brazil because they would be immediately re-enslaved and sold to the interior.Footnote 73 Indeed, gangs of thieves often attacked the slave vessels which were anchored in Rio's harbor, filled with enslaved Africans during the adjudication process.Footnote 74 Studies on the Emilia and the Brilhante, two slave vessels captured in 1821 and 1842 respectively, show that confinement aboard these ships and at the Casa de Correção constituted an important period of identity formation for the captives and transfer of diasporic knowledge about slavery and freedom. Slaves aboard the Brilhante primarily spoke Kimbundu – forty per cent of the captives – and could therefore converse with one another about the trauma of enslavement, the middle passage, and the emancipation process. The other slaves spoke Bantu languages but were not isolated. Likewise, slaves from the Emilia were of Congo-Angolan origins and were able to establish close, interpersonal relationships that allowed them to make sense of the social, economic, and political underpinnings of Rio's port society and to deploy strategies of resistance and survival. The records of the Brilhante and other captured slave ships in Cuba and Freetown reveal that families often experienced the traffic, adjudication, and confinement together, though they were eventually separated once distributed to private employers.Footnote 75 The mortality rate among enslaved Africans who awaited the decision of the Mixed Commission was very high. The necessity to prevent their re-enslavement, reduce their mortality, and ultimately the failure to repatriate them led to their confinement at the Casa de Correção in depósito or under legal guardianship.Footnote 76 Confinement became a formative regulatory aspect of the emancipation process for liberated Africans, while also entrenching slavery through the incarceration of rebellious slave detainees.

Liberated Africans were held at the Casa de Correção because they were a symbolically dangerous group in the slave society. In 1834, Manoel Alves Branco, a government minister, admitted that “it was still not possible to re-export any of the liberated Africans out of the empire”. As a result, he argued, the government “was forced to distribute” them to privileged employers based on the 1818 decree which authorized utilizing them in public works.Footnote 77 It was inconceivable that liberated Africans could be released into the Brazilian population as “free men” as Branco acknowledged that “even their distribution did not satisfy the great purpose of ridding the country of an ever dangerous population”.Footnote 78 Branco's statements expressed the ambivalence of the Brazilian authorities about the politics of regulating the presence of liberated Africans. Even as the government distributed liberated Africans to politically connected civil servants, officials expressed the fear that this population could introduce subversive ideas among the slave population, a great number of whom were illegally enslaved after 1831. The authorities feared that the consignment of liberated Africans could “become unbearable after they have become acculturated and circulating with the opinion of free men among slaves”.Footnote 79 In the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution and the Malê/Muslim slave rebellion in Bahia, liberated Africans appeared as a particularly incendiary group. In 1835, Paulino Limpo de Abreu, another government minister, published a letter in which he raised the specter that the Bahian insurgency would expand to Rio due to its “territorial proximity” to Salvador and “the size of its slave population”. Abreu understood that it was Rio's standing as a seaport which made it susceptible to the spread of the rebellion from the north-east. In the 1830s, mutinies by troop regiments in the north-east spread through Rio from the sea through navy sailors and mariners who traveled between the two cities and carried the wind of insurgency with them. Abreu argued that it was the “impolitic conservation of liberated Africans among us” that raised the alarm. There existed “secret societies”, he continued, “which worked systematically to foment slave insurrections by preaching the Haitian doctrine of a mass slave uprising”.Footnote 80 The idea of freedom that liberated Africans and Haiti symbolized was regarded as a colossal threat to the expansion of slavery in the coffee region.

Small-scale slave owners and Rio residents also expressed a fear of the ideological powder keg that liberated Africans represented on the streets. A resident who identified as a “victim” implored Police Chief Eusébio de Queiroz to continue the “wise measures to cleanse the city” of liberated Africans. The author argued that liberated Africans were “harmful” to the slave order and concluded that most emancipated Africans were “corrupt and seduced slaves” into freedom “by taking them to their residences”.Footnote 81 The persistence of the Brazilian authorities in referring to liberated Africans as “Africanos livres”, which literally translates as “free Africans”, offers an interesting window onto the ambivalence of slavery's expansion in the nineteenth century. The term “Africanos livres” distinguished liberated Africans from other African-born slaves who had been manumitted by their owners or freed through self-purchase and were known as “Africanos libertos”, or emancipated Africans. The persistence of the term “Africanos livres” in Brazil, where the “second slavery” expanded most massively in the nineteenth century, points to the conflicting politics of liberation and unfreedom that defined the labor landscape of the Atlantic. The Casa de Correção was a key site for articulating this process because of its significance as employer and distributor of liberated Africans as well as its significance as a penitentiary.

THE MOTLEY CREW

In total, 450 to 700 slave detainees, free prisoners, leased slaves and free craftsmen, vagrants, and liberated Africans built the original pavilion of the Casa de Correção between 1834 and 1850. Workers carried the stone to erect the tall walls that sealed the prison from the city and dug into the hard clay ground of Catumby Hill to build the penitentiary's foundations. It was grueling work. The government hired a company to provide the food and clothing for the prison's residents and builders. Though most prisoners were men, there were many women who contributed to the prison's construction as cooks and seamstresses after 1850.

The authorities established a hierarchy among the workers according to skills and legal status. Skilled workers were recorded separately in monthly reports on the prison's workforce. There were on average 54 stonemasons, 15 carpenters, 4 cart pushers, 17 stone cutters, 1 to 2 cooks, 1 overseer, and 6 or 7 foremen among the skilled laborers. Skilled craftsmen were a mixture of leased slaves, Calabouço slaves, convicts of legally free status, and hired skilled craftsmen of Portuguese descent. Skilled craftsmen included individuals like Manoel José Soares, an immigrant from Trás-os-Montes in north-eastern Portugal who arrived in Rio de Janeiro in May 1836. By 1838, he was employed as a stonemason at the Casa de Correção. He lived in Conde Street, in the immediate proximity of the prison. In 1835, 101 laborers identified as “craftsmen and apprentices of various trade” worked at the prison without clarification of their legal status, which suggests that this information was not important to the authorities in categorizing the workforce. But in 1849, when Eusébio de Queiroz became concerned with reforming the prison's labor force, he observed that salaried day workers “were almost all slaves, especially in the class of stonemasons”.Footnote 82 He calculated that nineteen out of twenty stonemasons and sixteen out of twenty-seven ditch diggers were slaves.

Skilled workers also included liberated Africans as apprentices and as experienced craftsmen. It is possible that liberated Africans were already skilled artisans when they arrived in Brazil, and that they were transferring manual skillsets to the new environment. But the discourse of “apprentices of freedom” that regimented the lives of liberated Africans at the Casa de Correção shaped official perceptions of emancipados as unskilled workers who “showed more devotion and skills” than other laborers at the penitentiary.Footnote 83 Prison administrators highlighted the docility of liberated Africans and their eagerness to be trained as craftsmen to indicate the success of apprenticeship. By claiming that liberated Africans were dutifully learning a trade, the authorities could justify the benefits of utilizing them to build the prison while implicitly comparing them with the idle Brazilian vagrants.

Portuguese nationals were employed in managerial positions as foremen and overseers. Slave plantations routinely utilized Portuguese men as overseers, which allowed planters to deflect the violence of the slave regime to those who enforced the power of the whip. Portuguese overseers were known to be particularly violent. They often received the brunt of slaves’ violence against enslavement.Footnote 84 By hiring Portuguese men as overseers, prison administrators recreated the racial and ethnic dynamic of the plantation at the Casa de Correção. Still, by having Portuguese supervisors and foremen work alongside other skilled workers, leased slaves, Brazilian nationals, convicts, and other Portuguese craftsmen, administrators deftly identified them as one undifferentiated group (Table 2). This strategy reinforced hierarchies of control through the manipulation of ethnic difference, legal status, and the infamous tensions between Brazilians and Portuguese subjects.

Table 2. Casa de Correção's workforce by skills and status, March 1838.

Sources: “Relação dos Trabalhadores e Operários Empregados nas Obras da Casa de Correção em o mez de Março 1838”, in Correio Official, 6 June 1835. The administrative staff are not listed in this table. They included a surgeon, a nurse, a clerk, a guarda de obra (general supervisor), a chief administrator, a prison warden, a doorman at the main gate, and a supply collector or arrecadador.

Tensions between Portuguese overseers and enslaved Africans exploded in the most famous case of resistance at the Casa de Correção, which involved a Congo-born liberated African, Bonifácio, who killed a Portuguese supervisor, Joaquim Lucas Ribeiro, in 1846. Ribeiro was scheduled to publicly chastise Bonifácio with a palmatória, a flat wooden instrument traditionally utilized to castigate domestic slaves. The authorities usually flogged Calabouço slaves between noon and 2.00 pm in the presence of their masters, who paid the government for the service. Bonifácio would have understood the lashing in the presence of slave owners as particularly degrading. When Ribeiro approached Bonifácio, the latter repeatedly struck the supervisor in the chest with a compass. At his trial, Bonifácio argued that “he had lost his mind” “because of the punishments that he had received and would still suffer” from Ribeiro. Surprisingly, Bonifácio was sentenced to only a year of “prison with labor”, which suggests that the jurors did not really sympathize with Ribeiro. Despite the overseer's authority over the liberated African, he was still a disposable worker.Footnote 85

Resistance at the prison took the form of grievances to improve treatment of workers and convicts but did not challenge its labor arrangement, as is apparent from an 1841 petition that legally free prisoners and liberated Africans wrote to the emperor.Footnote 86 The petition was divided into two sections that addressed the complaints of each group separately; this suggests that convicts and liberated Africans recognized their common experience as a confined population whose labor was vital for building the penitentiary despite their different legal status. Legally free prisoners pleaded with the emperor to “listen with compassion to their complaints and sufferings”. They argued that the construction of the penitentiary, the navy arsenal, and “all other public works” in the city were important nation-building projects to which they contributed. They denounced the unequal treatment in the quality of food and clothing of convict workers at the Casa de Correção and at the navy arsenal. Their discussion of unjust treatment in the distribution and the quality of food and clothing articulated claims of citizenship that were based on the language of imperial paternalism. The letter denounced rampant corruption among prison administrators. Convicts criticized the administrative staff as primarily Portuguese and the prison population as mostly Brazilians. The petition reminded the emperor, who was born in Brazil, of the well-known “bitter rivalry between Portuguese and Brazilians” and argued that the predominance of Portuguese in the administrative staffs would eventually “lead to violence”.Footnote 87 Bonifácio's killing of the overseer in 1846 dramatically fulfilled this prediction.

Liberated Africans took turns to beseech the emperor to look toward the “poor black Africans”, who labored in public works in the city and sought “relief” from their sufferings at the Casa de Correção. They referred to themselves as “slaves”, but it was a strategic identification to gain the emperor's sympathy because slave detainees from the Calabouço were not included in the petition. The petitioners deployed the term to qualify their real lived experience and treatment at the prison and to alert the emperor to their plight. Liberated Africans also identified themselves as contributing members of society who supported the larger project of modernizing Brazil through their labor. They argued that prison administrators deprived them of some basic privileges – customary rights – that distinguished them from slave detainees at the Casa de Correção, such as the privilege to walk around the small garden plot at the prison on Sundays and saints’ days. They were forced to live in the Calabouço with slave detainees and were kept in their cells on holy days. Even their vintém – partial wage – was withheld at times as punishment. The emancipados were therefore arguing that they were treated no better than slaves and convicts. They expected the emperor to know that they were neither slaves nor convicts but apprenticed laborers and freedmen. The petition also addressed the suffering of liberated African women – and one might imagine children – at the Casa de Correção. One liberated African woman was “castigated so vigorously” that her clothes ripped apart. She was subsequently sent to work in the chained water gang despite her wounds. The emancipated Africans asked the emperor to remove their “iron chains” and to relocate them to the navy arsenal. Their request is significant because in the 1840s naval officers began reforming the navy arsenal's workforce by replacing slave workers with free wage laborers, part of the politics to discipline the growing free black population in the city by impressing them into the navy, where corporal punishment was applied to sailors until the first decade of the twentieth century.Footnote 88 In November 1840, the administrator of the navy arsenal published a notice stating that the office would hire only “legally free craftsmen”.Footnote 89 In September 1840, the armory “dismissed all slave craftsmen” and decided to “admit only free artisans”, including those as sailors and operators of machinery.Footnote 90 Liberated Africans knew that the law had declared them free, and those who worked at the Casa de Correção were well cognizant of labor conditions at the arsenal. It is therefore possible that their request to be relocated to the navy arsenal was an attempt to claim “full freedom” as free blacks despite the precariousness of that position.Footnote 91

FROM SLAVERY TO FREE LABOR

On 7 July 1850, the Casa de Correção was inaugurated after sixteen years of construction under Eusébio de Queiroz's leadership. Queiroz hoped that inaugurating the penitentiary would finalize the process of sanitizing the city's prisons, especially following a devastating epidemic of yellow fever in 1849 that many linked to the city's crowded jails and the presence of slave vessels in its harbor. Queiroz observed that there was a “superabundance of labor” at the Casa de Correção and suggested discontinuing the utilization of enslaved workers and replacing the penitentiary's mixed slave and legally free workforce with free wage workers.Footnote 92 Effectively, in January 1849, Queiroz fired all wage-earning slaves and sent a call to hire only legally free workers to work at the penitentiary. He justified this decision by arguing that free workers “competed in more than sufficient numbers” for work in the city.Footnote 93 Queiroz concluded that the labor of leased slaves was inferior to that of legally free wage laborers and asserted that the difference between legally free workers and leased slaves was the “contrast between one who toiled for himself” and “one who labored for others”. Queiroz's assessment was based on his knowledge that it was the masters of the leased slaves who pocketed their wages. Leased slaves therefore had no incentive to improve their performance and productivity.

Queiroz's opportunistically timely appreciation of free wage laborers was the result of his involvement in managing the “abolition crisis” that resulted from the cessation of the traffic between 1848 and 1850.Footnote 94 In 1845, the British Parliament passed the Aberdeen Act, which empowered cruisers to confiscate Brazilian ships to curtail the slave trade. The act challenged Brazilian sovereignty and culminated in the abolition of the traffic in 1850 with the passage of the Eusébio de Queiroz Law. The Brazilian government actively policed its coasts to enforce the law and a few slave ships were captured as late as 1856.Footnote 95 Reflecting on the events leading to the 1850 law, one justice minister argued that the illegal entry of millions of Africans into Brazil demonstrated that the country had failed to “execute effectively its laws” and “the imperial government” had to “bring about the complete extinction of the traffic as a measure of social convenience, civilization, national honor, and even of public security”.Footnote 96 The reference to public security was an allusion to the problem that the expansion of slavery represented in Brazil, while it was ideologically challenged in the aftermath of the Haitian Revolution.Footnote 97 Brazilian slave owners had fashioned the postcolonial state to protect the continuation of the traffic through draconian laws that inflicted severe punishment on slave rebels, including the death penalty.Footnote 98 Politicians continuously feared the implications of the predominance of Africans in the slave population, even as they asserted the necessity of slaves for national economic production. Seaports like Rio were under particular vigilance because, as one minister argued regarding the challenge of controlling urban slaves, “one does not guard this property, it walks through the streets”.Footnote 99 Salvador's Police Chief established an 8.00 pm curfew to restrict the circulation of slaves and freed persons in the city after the 1835 Muslim uprising.Footnote 100 Powerful police forces were created in Rio, Salvador, and São Paulo to control their expanding urban slave population and acted as the “coercive power of the owner class” in these settings.Footnote 101 Queiroz oversaw the formation of Rio's police between 1833 and 1840. As Justice Minister in 1848, he administered the maintenance of public security in the empire and was at the heart of the diplomatic firestorm occasioned by the Aberdeen Act. On 4 September 1850, two months after the opening of the Casa de Correção, he promulgated the Eusébio de Queiroz Law, which authorized Brazilian authorities to apprehend all vessels caught with slaves aboard or with signs of involvement in the traffic.Footnote 102 The law stipulated that Africans freed from the traffic would be repatriated to their ports of origin on the African coast or “anywhere outside the Empire”. The 1850 law closed a loophole in the 1831 regulation by specifying that liberated Africans who were not repatriated would be put to work under the “guardianship of the government” but not consigned to private employers. However, the utilization of liberated Africans as involuntary free laborers continued until their emancipation in 1864. By then, the government had already lost count of how many liberated Africans had been distributed, and to whom.

As the author of the 1850 law and the person in charge of public security in the empire, Queiroz had a keen understanding of the implications of the regulation for the continuation of slavery in Brazil. Without the continuous entry of African slaves, the production of coffee and sugar, the basis of national wealth, would decline. Queiroz, a slaveholder and a politician, contextualized his call to cease hiring leased slaves at the Casa de Correção as part of a policy to redirect slaves to plantation agriculture in rural zones for the preservation of slavery. He justified his forceful intervention in the Casa de Correção's workforce by arguing that “national interests called for the need to protect colonization and reduce the criminal introduction of slaves”. Queiroz's reference to the traffic as “criminal” expressed the consensus among politicians in Brazil's important port cities, Rio, Salvador, São Paulo, that the significance of African slaves in the Brazilian population occasioned by the traffic posed a constant threat of violent slave uprisings. They were ever conscious of the reality that the slave vessel was the “material infrastructure” that renewed slave labor in Brazil while serving as the vehicle of “revolutionary antislavery”.Footnote 103 In 1848, the provincial assembly of Bahia in the north-east passed a law which prohibited African slaves and freedmen from being employed as sailors, a recognition that the seaport was the seedbed for the entry of subversive ideas. The city's merchants went so far as to purchase 185 boats, which they offered to legally free Bahians to replace the African sailors.Footnote 104

Queiroz understood that the abolition of the traffic necessitated a shift in the geography of slavery from coastal towns and busy port cities to the country's agrarian hinterland, where slave labor was most needed. He initiated that process at the Casa de Correção, not necessarily as a precursor of a foreordained abolition of slavery but as part of the politics of permutations of free and unfree labor from which Brazilian colonization and postcolonial state formation unfolded. Effectively after 1849, there were numerous calls to hire skilled artisans to work at the Casa de Correção, such as a call for ax carpenters, two master blacksmith, two shoemakers, and a tinsmith.Footnote 105 These new employees worked as instructors in the prison's workshops, initiating its transition into a reformatory penal institution to produce a disciplined citizenry. Liberated Africans continued to contribute to build the second pavilion of the penitentiary, which was completed in 1860. However, waged slaves disappeared from the prison's workforce, a fact which signified their exclusion from the city's labor market.

Slaves continued to shape Rio's economic life, but their numbers dwindled from thirty-eight per cent in 1849 to less than seventeen per cent of the city's residents by 1872. Most of the shift occurred among male slaves, the number of whom diminished by sixty-two per cent. The city's slaves, especially enslaved male workers, were being sold into Rio's hinterland to work in agriculture. The redistribution of the slave population from the north-east to the central-south region, and from coastal cities to the agrarian hinterlands, was a political process of managing the ripple effects of the cessation of the traffic to preserve slave labor for as long as possible in Brazil. The drop in Rio's male slaves corresponded with an upsurge of 113.3 per cent in the number of male Portuguese immigrants, an increase that started in 1849 and that facilitated the displacement of slaves as wage laborers from Rio's market to the countryside.Footnote 106 Portuguese immigration led to an expansion of free and foreign-born workers in the city and became associated with free wage labor. Lusophone immigrants eventually eclipsed slaves-for-hire in Rio's free-market economy.Footnote 107 Foreigners who joined the ranks of the free poor began taking occupations previously held by wage-earning slaves, such as carrying water in the city. The government modernized the business of carrying weights by encouraging immigrants to utilize wheeled carts, which were more efficient. The cessation of salaried slave labor at the Casa de Correção was, therefore, consistent with a broader process in which free wage workers began to substitute salaried slave laborers in Rio de Janeiro.

CONCLUSION

This story of the utilization of a mixed labor force to build the Casa de Correção between 1834 and 1850 demonstrates that port cities such as Rio were key nodal points from which to examine the relations between free and unfree labor in the Age of Abolitionism globally and postcolonial state formation in Latin America specifically. As Brazil's capital city and its most significant seaport, Rio became the experimenting ground for modernizing institutions of social control which were vital for securing the flow of people – slaves and immigrants – as labor commodities of the Atlantic to and from its hinterland. The government organized a labor force from the city's enslaved and legally free population to build the prison. Legally free individuals were also reduced to unfreedom through imprisonment and coerced labor, including navy and military labor, as Megan Thomas has argued, to erect the penitentiary and maintain order on the streets. The flexibility and opportunism that this labor practice evidenced highlights the underbelly of global capitalism and postcolonial state formation during a crucial period in which anti-slavery currents challenged chattel slavery in the Atlantic while convictism mobilized mass labor in the Indian Ocean.Footnote 108 The reorganization of the Casa de Correção's labor force after 1850 did not signify a termination of slave labor in Brazil, but rather its entrenchment in the coffee plantations of the hinterland until abolition in 1888. Slaves continued to inhabit the penitentiary's cells – notably at the Calabouço – for disobedience or for flight while legally free vagrants and criminals toiled in its workshops to inculcate in them the appreciation of work.