Introduction

The diplomatic profession has for some time been experiencing two parallel transformations. On the one hand, along with the evolution of diplomacy, understood broadly as the institution and practiceFootnote 1 of managing international relations without recourse to war,Footnote 2 the nature, scope, and salience of diplomatic work, that is, the activities and responsibilities of diplomats formally employed in ministries of foreign affairs (MFAs), has been changing. With the rise of summit diplomacy since the 1950s, diplomats have gradually relinquished their high-profile roles in the actual conduct of strategic negotiations to chief executivesFootnote 3 and resigned themselves to backroom roles in preparation, networking, and agenda-setting. This decline in the authority and visibility of diplomats was compensated with the expanding number of multilateral organisations to which all member states appointed diplomatic representatives. With multilateralism, international diplomacy expanded into many issues of functional cooperation, such as trade, environment, and arms control, where diplomatic work required greater technical expertise.Footnote 4

The rise of public diplomacy, which was spearheaded by the democratisation of political systems,Footnote 5 also shaped diplomatic work. Diplomats, who are accustomed to the highly insular, elitist, and secretive world of diplomatic work, have been increasingly called upon to conduct public relations, communication, and outreach activities with non-diplomatic actors, such as business groups, diasporic organisations, civil society groups, and the broader public.Footnote 6 The pluralisation of diplomatic actors in this fashion has encroached upon and thus limited professional diplomats’ roles and authority.Footnote 7 The most current challenge that diplomatic work is facing is also arising from domestic political changes: populism. In many countries, MFAs are increasingly having to contend with political executives, who are publicly challenging their relevance, skills, and authority and weakening their institutional resources.Footnote 8

On the other hand, a parallel transformation, which we refer to as the feminisation of diplomatic work, has been ongoing in the gender composition of diplomatic professionals. Instituted as an exclusively male profession in the latter half of the nineteenth century, diplomatic work has witnessed the entry of a growing number of women professionals into its ranks, especially after the elimination of various formal obstacles in the 1970s, largely owing to the pressure exerted by the transnational feminist movement. The percentage of women ambassadors rose from less than 1 per cent in 1968 to 5.9 per cent in 1998 to 15.3 percent in 2014 and to 23.4 per cent in 2024 globally, and up to 50 per cent in some leading countries, such as Australia, Canada, Finland, New Zealand, and the United States.Footnote 9 Consequently, albeit more gradually, the masculinity norms of the diplomatic profession also began to be undermined. The inclusion of women in diplomacy assumed a greater significance beyond meeting goals of gender equality, fuelling expectations that it will pave the way for more peaceful and cooperative international relations. In that spirit, a number of states have declared an explicit adherence to feminist foreign policy, which is defined around the principles of inclusion, peace, and gender equality.Footnote 10

These two concurrent transformations have largely been studied in separate literatures. A very wide literature has examined the historic evolution of diplomacy and assessed the repercussions of trends, such as the rise of public diplomacy,Footnote 11 digitalisation,Footnote 12 and new diplomatic actors on diplomatic work.Footnote 13 Similarly, a new research agenda on gender and diplomacy has documented the rise of women in diplomatic work,Footnote 14 continuing, mostly informal, restrictions on women’s advancement in MFAsFootnote 15 and the varied gender enactments of diplomats.Footnote 16 However, the question of whether and how these parallel transformations are interconnected and potentially influencing one another has been neglected.

Recently, Stephenson has identified a troubling connection in the Australian Department of Foreign Affairs and Trade (DAFTA).Footnote 17 She has noted that the increasing representation of women has coincided with the decline in the power, status, and influence of this diplomatic institution relative to more militaristic agencies carrying out Australian foreign policy. As we will explain later, these findings validate the foundational thesis of the literature on occupational feminisation, which posits that the entry of women into traditionally male dominated professions brings about a devaluation of those professions in terms of prestige and pay.Footnote 18 Such a possibility of devaluation is troubling to say the least because it upends the prevailing expectations about feminisation, meaning increasing share of women, leading to progressive transformations in diplomatic work, diplomacy, and the management of relations between states in general. Scholars and practitioners increasingly expect that greater representation of women in diplomatic work will transform the masculinity norms of diplomatic work and reshape diplomacy as a more inclusive, less combative, and more public practice in service of a more principled and peaceful foreign policy. The concurrent devaluation of diplomatic work would offset these positive effects by simultaneously shifting the locus of diplomacy away from diplomats to political leaders, unauthorised individuals, and non-institutional channels and exalting more confrontational and violent means of managing relations between states above diplomatic ones. That is why we contend that the possibility that feminisation may be driving a devaluation of diplomatic work deserves further exploration in terms of its underlying causal mechanisms, scope conditions, and generalisability.

In the next section of the article, we first delve into the literature on occupational feminisation and highlight recent studies where feminisation has been found not to lead to devaluation in high status occupations and in occupations where ‘feminine’ skills,Footnote 19 and consequently female labour, are highly valued. Then, focusing on these two scope conditions as safeguards against devaluation, we identify the factors that affect the status of diplomatic work and shape the valuation of female labour in diplomatic work. Subsequently, in the third section, we trace how these factors have varied over time and interacted with feminisation, as diplomacy has evolved from the classical to polylateral mode and are likely to vary with the rise of populism. This structured temporal analysis suggests that a mono-causal relationship between feminisation and devaluation of diplomatic work does not exist. In fact, we find that feminisation in its incipient stages coincided with an increase in the status of diplomatic work and reinforced an increase in the value of female labour in diplomacy. However, the current decline in the status of diplomacy and diplomatic work due to rise of populism may instigate a vicious cycle where it reinforces and is further reinforced by feminisation.

Then, in the fourth section of the article, we analyse how the increasing representation of women in the Turkish Ministry of Foreign Affairs (TMFA) has interacted with Turkey’s evolving foreign policy priorities, institutional changes in foreign policy bureaucracy, and the populist–authoritarian turn. We find that in the course of Turkish diplomacy’s specific transformations, the status of diplomatic work and value of female labour followed the patterns identified in our historical sketch. In the 2000s, along with Turkey’s rising diplomatic ambitions and adoption of soft power strategies, the status of diplomatic work remained high, and the value of female labour increased and supported the growing presence of women in Turkish diplomacy. However, since the mid-2010s, the centralisation of foreign policy-making under the increasingly populist and authoritarian government undermined the status of diplomatic work and set a conducive context for feminisation to be a contributing factor to devaluation. In conclusion, we summarise our argument and discuss its implications for the future of diplomacy.

Feminisation: Transformation or devaluation?

The view that women’s participation promotes a progressive transformation in diplomacy and more peaceful international relations underpins much advocacy for their inclusion. Research in peace studies shows that women are generally less militaristicFootnote 20 and improve peaceful outcomes when involved in negotiations.Footnote 21 Thus, greater participation of women in foreign affairs bureaucracies is expected to transform diplomacy in the direction of a more inclusive, less combative,Footnote 22 and more public practice, and in service of a more principled and peaceful foreign policy.

Feminist institutionalism, on the other hand, underscores that diplomacy has been constituted as a ‘gendered institution’ shaped by masculinity normsFootnote 23 and thus is likely to resist change despite increasing female participation. However, feminist institutionalism also underlines the possibility that incremental, layered shifts – driven by women’s agency and growing representation – can gradually challenge these norms and transform institutional practices over time.Footnote 24

Focused thus on the question of transformation, the relevant literatures in IR have neglected the risk of devaluation, which has been the main concern of the literature on occupational feminisation. This largely empirical literature has focused on demonstrating and explaining the correlation between the entry of women in previously male-dominated occupations and the decline of average wages in those occupations.Footnote 25 It is argued that male-dominant occupations experiencing a large inflow of female workers experience devaluation because of occupational gender stereotypes and cultural norms that attribute more economic value to the work done by men than to the work done by women.Footnote 26 While mostly manifest in terms of a decline in pay, it has also been demonstrated that the prestige and perceived potency of an occupation declines when it is stereotyped as femaleFootnote 27 and that the nature of work changes towards more routine tasks or tighter managerial control.

The literature has highlighted two main causal mechanisms through which feminisation leads to devaluation: First, the increasing share of women in an occupation leads to the (trans)formation of occupational gender stereotypes, which are beliefs about different occupations and tasks requiring ‘masculine’ or ‘feminine’ traits and skills and hence being better suited for women or men.Footnote 28 In other words, the increasing share of women in an occupation generates beliefs about the occupation being better suited for women. Second, gender stereotypes interact with a cultural bias against the value of the female labour, leading to devaluation. Hence, devaluation occurs if the perception of an occupation to be is paired with the judgement that women’s work is worth less than men’s work. As England et al. put it: ‘somehow, the low status of women “rubs off” on employers’ evaluation of the occupation’.Footnote 29 The factors underlying these causal mechanisms, namely occupational stereotypes and cultural bias against female labour, operate mostly implicitly and are thus hard to ascertain empirically. While some scholars have noted that stereotypes are becoming less significant with changes in gender composition and advances in gender equality,Footnote 30 others have found that gender stereotypes attached to occupations remain sFootnote table 31 and continue to generate value judgementsFootnote 32 even as people are more reluctant to publicly express them.Footnote 33

Recent research in the occupational feminisation literature has also specified some conditions under which occupational devaluation does not occur or is mitigated. Felix BuschFootnote 34 has found that the devaluation effect has been restricted to the bottom 80 per cent of occupations in terms of pay in the United States. Numerous studies have shown that devaluation impact is limited in high-skilled professions because high returns to education conceal the devaluation dynamics.Footnote 35 Feminisation does not lead to devaluation in occupations that simultaneously gain prestige for other reasons.Footnote 36 Additionally, male and female workers in a feminising occupation may also experience a reverse revaluation impact under certain conditions.Footnote 37 Remaining male workers in a feminised occupation may disproportionately benefit from gender stereotypes about male competence and leadership qualities and be promoted to supervisory and managerial positions. At the same time, feminisation may enhance the value of female work if it drives changes in stereotypes about an occupation as specifically requiring ‘feminine’ skills.Footnote 38 Such changes occur when gender-essentialist attitudes towards occupational tasks and skills intersect with increased demand for female-typed tasks and skills in those occupations. According to Li, the positive effect of feminisation on wages materialises due to the increasing demand for ‘people skills’ in higher-skilled occupations and the association of these skills with women.Footnote 39 In sum, newer scholarship has moved away from broad generalisations about the effects of feminisation and supports evaluating the risk of devaluation in relation to occupation-specific dynamics.

Surprisingly, the risk of devaluation has not attracted the interest of the growing literature on gender and diplomacy, until Stephenson’s study of the Australian context.Footnote 40 However, findings that are relevant for the mechanisms and conditions of occupational devaluation are amply present. For example, relevant for our understanding of diplomacy’s gender stereotyping is Ann Towns’s finding that, despite being a male-dominant institution, diplomacy and the figure of the diplomat have traditionally been the target of various feminising depictions, which have been used to delegitimise diplomatic policy options and to discredit the diplomats.Footnote 41 Similarly, studies that have analysed the assignment of male and female diplomats to tasks of differing prestige and powerFootnote 42 indicate that male labour continues to be more highly valued in diplomatic work. On the other hand, analyses of gender practices and performances have found especially newer generations of female diplomats to be alternating between ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ behaviours depending on situational demands.Footnote 43 This shows that ‘feminine’ skills are becoming more highly valued in some types of diplomatic work.

Thus, it cannot be assumed that feminisation is driving the devaluation of diplomatic work because such a correlation has been found in other occupations. The question requires an analysis of whether the conditions for (or safeguards against) devaluation are present in diplomatic work and empirically demonstrating that the underlying causal mechanisms are at play. In this article, we primarily focus on the conditions. In the following, we start by applying the conditions identified in the occupational feminisation to diplomatic work to conceptually specify the factors that prevent (or reinforce) the devaluation of diplomatic work in the course of feminisation.

The first condition stipulated by the literature on occupational feminisation is that devaluation is less common in high status occupations and rendered more complex with the evolving prestige of occupations. Assessing the status of diplomatic work requires going beyond an analysis of market conditions, such as average pay and skill level, and focusing on political factors at the systemic, state, and domestic levels affecting the overall status of diplomacy. At the systemic and state levels, the status of diplomacy and diplomatic work is affected by factors such as the salience of international issues, preferences for militarised versus diplomatic solutions to disputes, level of institutionalisation in the international system, and scope and ambition of foreign policies. The status of diplomacy and diplomatic work is enhanced in systemic and state contexts where international issues are salient, international influence is sought, international order is highly institutionalised, and diplomatic solutions are preferred.

At the domestic level, the status of diplomacy and diplomatic work is contingent on its positioning vis-à-vis political authority and other bureaucracies. Centralisation of foreign policy-making around the executive diminishes the status of diplomatic work by limiting the authority and autonomy of diplomats and relegating them to operational tasks. The bureaucratic organisation of foreign policy and external relations is also an important domestic factor. The creation of specialised bureaucracies outside of MFAs that are responsible for policies with an external dimension, such as migration or public diplomacy, reduces diplomats to a coordinating role. Additionally, populist leadership and discourse diminish the status of diplomatic work by forging a moral hierarchy between the bureaucratic elite and the real people.

The second condition concerns the valuation of female labour in an occupation: if the value of female labour increases, then the feminisation of an occupation does not lead its devaluation. While the lower valuation of female labour is ultimately rooted in social and cultural biases against women, it has been argued that devaluation is less common when feminisation also drives changes in perceptions about occupations as specifically requiring ‘feminine’ skills and abilities. This claim assumes, firstly, that gender-essentialist attitudes, marking specific tasks, roles, and functions alternatively as ‘masculine’ versus ‘feminine’ and associating them respectively with male and female bodies, persist at the institutional and societal levels. Secondly, it draws the controversial implication that these gender-essentialist attitudes may advantage female workers if the perceived value of ‘feminine’ tasks, roles, and functions in an occupation increases relative to ‘masculine’ ones. Thus, feminisation may not lead to devaluation if it intersects with transformations that enhance the weight and salience of ‘feminine’ tasks and roles, relative to ‘masculine’ ones, and consequently enhance the value of female labour in an occupation. In diplomacy, tasks and roles such as communication, organisation, and care are constructed as ‘feminine’, while, for example, bargaining is considered ‘masculine’. While this potentially positive effect of gender essentialism ought to be acknowledged and studied, it should also be stressed that gender essentialism cuts both ways. Its persistence, while the weight and salience of ‘masculine’ tasks and roles are increasing in an occupation, would drive devaluation of female labour and, along with it, the devaluation of the feminised occupation. In fact, this article shows this reverse scenario materialising in diplomatic work.

In sum, our conceptual application of the occupational feminisation framework to diplomatic work indicates that broader developments and transformations in diplomacy impinge in at least two ways on the relationship between feminisation and devaluation: firstly, by affecting the status of diplomacy and diplomatic work, and secondly, by changing the balance between ‘masculine’ and ‘feminine’ tasks in diplomatic work. This supports the initiating premise of this article that gender in diplomacy ought to be studied in tandem with other transformations in diplomacy. Thus, in the next section, we present a three-stage sketch of the evolution of diplomacy in tandem with feminisation, focusing on how the status of diplomatic work and valuation of female labour in diplomatic work have varied over time.

Feminisation and the evolution of diplomacy

Diplomacy along with the factors that we have identified above as affecting the status and value of female labour in diplomatic work are in continuous evolution at the systemic and state levels. In this section, we use the construct ‘mode of diplomacy’ to refer to specific constellations of these factors. Employing terminology widely used in the literature to describe the evolution of diplomacy, we discuss below how these factors have coalesced in distinct ways in classical and polylateral modes of diplomacy and currently are shifting under the rise of populism.

Initially, diplomacy, as formalised and institutionalised in the Congress of Vienna in 1815, was exclusively based on a state-centric conception of relations, maintained around the Westphalian principle of sovereign equality of states, focused on concepts such as reciprocity, hard power, and non-interference in the internal affairs of other states. In this classical mode of diplomacy, foreign ministries and diplomats are the primary agents through which states interact with one another.Footnote 44 The status of diplomatic work is high; as diplomats guided political elites in the conduct of foreign policy, their skills were considered critical in shaping diplomatic outcomes.Footnote 45 Career diplomats also enjoy exclusivity, with negotiations held in secrecy, away from the involvement of other public actors.Footnote 46

The classical mode of diplomacy supported the male dominance in the profession and was in turn reinforced by it. Men were perceived to naturally possess the necessary skills to conduct classical diplomacy, such as rationality, status, hard bargaining, the ability to keep secrets, and project status.Footnote 47 Male diplomats, in turn, reinforced the masculine codes of honour and the realist principles that dominated inter-state relations.Footnote 48 Even as formal barriers against women in diplomacy began to be lifted, implicit stereotypes continued to discriminate against women as they were assigned to ‘feminine’ tasks such as consulates or functional units as well as less prestigious posts as ambassadors.Footnote 49

According to most studies, even as new practices were introduced, classical diplomacy remained dominant until the 1990s. Starting with the 1970s, diplomats’ roles have started to expand significantlyFootnote 50 with the dramatic increase in multilateral organisations, tackling global problems such as climate change, proliferation of weapons of mass destruction, international migration, trade, sustainable development, and humanitarian assistance.Footnote 51 Career diplomats had to share this growing diplomatic terrain with new diplomatic actors, such as NGOs, multinational corporations, individuals, celebrities, activists, diaspora groups, and local administrators. In characterising this new mode of diplomacy, we use the term ‘polylateral’, introduced by Wiseman to capture the intensification of systematic relations between not only states but also state and non-state actors in diplomacy.Footnote 52 In the polylateral mode of diplomacy, the status of diplomatic work remained high. While the exclusivity of MFAs in the conduct of diplomacy was diminished, career diplomats retained their central role in leading the negotiations between these diverse actors.Footnote 53

Parallel to these developments, significant changes in the gender make-up of diplomacy were observed. The United Nation’s (UN) efforts through organisation of specialised women conferences since 1975 as well as the adoption of the Beijing Platform for Action (BPfA) in 1995 and the Women, Peace and Security (WPS) agenda in 2000 led MFAs to remove formal barriers to women’s representation.Footnote 54 The percentage of women ambassadors rose from 5.9 per cent in 1998 to 15.3 per cent in 2014,Footnote 55 even though postings to prestigious positions remained limited.

In the context of these transformations, several factors enhanced the value of female labour in diplomacy. Security-focused, hard power–based foreign policy, which had reinforced male dominance in the diplomatic profession through their cultural association with masculinity, lost its dominance.Footnote 56 Instead, states became more interested in projecting soft power through exercising leadership on global normative issues, such as protection of human rights, promotion of human development, and environmental protection. With the growing concentration of diplomatic work in multilateral fora, issue-based expertise, agenda-setting, and the ability to lead positive sum cooperation assumed greater value as diplomatic skills.Footnote 57 The pluralisation of diplomatic actors increased the relative weight of administrative and communication tasks in daily diplomatic work. Care work, in the form of delivery of humanitarian aid, addressing specific concerns of women and other vulnerable groups, and providing services to citizens abroad, became diplomatic priorities. Sweden and, following it, ten other countries declared themselves to be specifically pursuing a ‘feminist foreign policy’, prioritising women’s rights, resources, and representation in international affairs.Footnote 58 Studies have shown that many women diplomats, entering the profession in greater numbers, chose to capitalise on these empowering transformations in diplomacy by presenting attributes and skills that are traditionally associated with femininity, such as empathy, sensitivity, and organisational and communication skills and care, as granting them a comparative advantage in the profession.Footnote 59

Currently, the rise of populism is driving a decline in the status of diplomatic work and in the valuation of female labour in diplomatic work. Populism has been defined in alternative ways,Footnote 60 and we acknowledge that conceptual variants recently introduced to the literature, such as liberal populism and anti-populism, make it especially difficult to draw broad conclusions about populism’s unique detrimental effects.Footnote 61 While populism cannot be reduced to a single, unified notion, it continues to offer an indispensable vantage point for interpreting current shifts in domestic politics, identifying general patterns amid significant contextual variation. In analysing the effects of the rise of populism on diplomatic work, we focus on what varied definitions take to be its core characteristic: governing through constructing antagonism between the people and the elite. This core aspect of populism allows populist leaders to frame bureaucracies, including the MFAs, as elements of the ‘corrupt’ elite, obstacles to the will of the people, and to delegitimise their expert knowledge.Footnote 62 Claiming, instead, to be the ‘champion’ of the ‘good’ people, populist leaders assume bilateral and multilateral diplomatic roles rather than delegating such tasks to MFAs and adopt a performative style that disrupts traditional diplomatic norms, characterised by coarse language, public display of emotions, and direct and public communication with counterparts through social media.Footnote 63 Additionally, they create new agencies composed of ‘loyal’ bureaucrats to reduce the influence of MFAs in foreign policy-making.Footnote 64

Populism as a style of governing manifests itself differently across political and ideological contexts, and its adverse impact on the status of diplomatic work is more pronounced in some contexts than in others. When coupled with authoritarianism, populism reinforces and legitimises the executive’s attempts to gain exclusive control over foreign policy-making and to constrain the autonomy of professional diplomatic corps. When coupled with nationalist and anti-globalist ideological stances, populism foments distrust of international cooperation and institutions by projecting the people versus elite antagonism also externally. Depicted most clearly in Trump’s ‘America First’ slogan, the egoistic pursuit of short-term national interest at the expense of institutional commitments and global and humanitarian concerns has become the cornerstone of populist foreign policies.Footnote 65 This undermines the liberal internationalist and globalist visions upon which the polylateral mode of diplomacy has been builtFootnote 66 and, along with it, the status that diplomats have gained in championing such visions. Additionally, the shift to nationalist, protectionist, militarist foreign policies has the general effect of undermining the value of female labour in diplomacy by demoting the significance of priorities and skills, such as soft power, communication, and care, which were considered as unique assets of women diplomats previously.

In some far-right ideological contexts, the ‘opportunistic’ synergy that has developed between anti-gender advocacy and populismFootnote 67 directly affects the valuation of female labour in diplomatic work. As populist executives mobilise the polarising potential of gender for domestic and international political gain, they reinforce convictions about natural differences and hierarchy between men and women. This sets a suitable context for the devaluation of the diplomatic work undertaken by the highly feminised MFAs along with their feminist priorities. The liberal-right government of Sweden, for example, retracted its feminist foreign policy in 2022 on the same day it took office.Footnote 68

In approaching populism as a style of governing, we do not isolate its effects to leaders, parties, and regimes that we prima facie identify as populist, and we consider the presence and prevalence of a populist style of governing in different political and ideological contexts as an empirical question. On the one hand, certain effects that we associate with the rise of populism, such as the centralisation of foreign policy-making around the executive and the shift to a geopolitical outlook and the pursuit of autonomy in international affairs, are developing into general trends impacting diplomacy and diplomatic work. On the other hand, the purported effects of populism on diplomacy and diplomatic work are being actively resisted and counteracted by MFAs and diplomatic practiceFootnote 69 as well as liberal and globalist actors. Thus, while the effects of the rise of populism on diplomatic work are increasingly visible, we characterise the current mode of diplomacy as populist–polylateral to capture these contingencies.

Most notably for our purposes, the rise of populism and its effects on diplomatic work have coincided with the peak point of women’s representation in foreign affairs bureaucracies. The percentage of women ambassadors rose from 15.3 per cent in 2014 to 23.4 per cent in 2024 globally. Moreover, it is becoming increasingly common for states to appoint women ambassadors to critical and visible posts such as Washington – not only in more gender-equal countries such as Sweden and the UK but also in states seeking to cultivate such an image, such as Saudi Arabia.Footnote 70 Feminised figurations of the diplomatFootnote 71 have also become more common. This coincidence creates a context where feminisation can also be used to reinforce the devaluation of diplomatic work. Feminisation allows populist leaders to use gender stereotypes and hierarchies to further weaken the MFAs. Within a broader masculinist discourse, populist leaders can also use feminised MFAs to construct a gendered division of labour where they assume ‘masculine’ roles like crisis management and competitive bargaining while assigning ‘feminine’ tasks, like administrative or coordination work, to MFAs.

In sum, the rise of populism is expected to bring about a decline in the status of diplomatic work and in the value ascribed to female labour in diplomatic work, thus undermining the two conditions that the literature has identified as safeguards against devaluation in feminising occupations. The coincidence between feminisation and populism also allows populist leaders to use gendered stereotypes to disempower the MFAs.

Table 1 summarises the claims of this section on how the increasing representation of women in diplomacy has occurred in tandem with the evolution of diplomacy as an institution. We have found that during the transition from the classical to the polylateral mode of diplomacy, there was not a context suitable for feminisation to lead to devaluation. This is because the entry of women into the diplomatic profession in greater numbers occurred while the status of diplomatic work remained high and the value of female labour in diplomatic work was enhanced as diplomacy shifted to issues and skills, such as soft power, communication, and care, that are culturally associated with femininity. Conversely, however, we have pointed out that currently, under the influence of populism, the status of diplomatic work as well as the value of female labour in diplomatic work is in decline, setting a context conducive for feminisation to lead to devaluation.

Table 1. Feminisation and evolution of diplomacy.

In the next section, we show how feminisation has interacted with broader changes affecting the status of diplomatic work and the value of female labour in diplomatic work in the case of Turkey. The case study allows us to apply the systemic patterns we have identified in this section and to evaluate the pertinence of Stephenson’s findingsFootnote 72 in a different political and cultural context. Turkey is a case of high-status foreign service undergoing rapid feminisation.Footnote 73 With the expansion of its foreign policy agenda, Turkey made a belated transition to a polylateral mode of diplomacy in the early 2000s, and also, in the past ten years, the Turkish political regime has experienced a slide into populist authoritarianism.

In our analysis, we trace how, since the 1970s, the priorities of Turkish foreign policy, political developments affecting the status of the TMFA, and the valuation of female labour in Turkish diplomacy have varied alongside the growing representation of women in the TMFA. We draw on a diverse set of sources, including secondary literature, interviews with former and currently serving diplomats, published interviews with and memoirs of diplomats, data – both personally obtained from and publicly reported by TMFA – regarding the changing gender composition of the Turkish diplomatic corps, and public data about the budget allocation of the TMFA and other agencies conducting foreign policy. A longitudinal perspective enables us to capture the dynamic, multifaceted relationship between feminisation and other factors affecting the status of diplomatic work rather than relying solely on patterns observed at present.

‘Oral history interviews’,Footnote 74 conducted with five male and nine female career diplomats who have formerly served or are currently serving in ambassadorial, senior, or mid-career positions, are a key pillar of our research for assessing the (changing) valuation of women’s labour in diplomatic work. Interviewees were approached in three phases (2016, 2019, and 2022) using snowball sampling, a purposeful strategy well suited for accessing closed elite institutions such as the TMFA. Interviews were conducted either face-to-face, most often in exclusive diplomatic clubs, or via secure online communication. Interviews ranged from forty-five to ninety minutes and followed a semi-structured format, guiding the respondents to reflect on the changing nature of diplomatic work and the shifting attitudes towards gender in diplomacy on the basis of their personal experience.

Feminisation and the evolution of TMFA

Until the 2000s, Turkish foreign policy focused almost exclusively on what were considered as existential security concerns of Turkey arising from regional rivalries, such as Cyprus and relations with Greece, Syria, Armenia, and Iran.Footnote 75 Turkish national interests were rigidly defined and the defence of those interests, through hard bargaining and, if necessary, the threat of force, were the top priorities. Even as diplomacy evolved into a polylateral mode at the global level, a state-centric conception of world politics and distrust of international institutions and non-state actors in the defence of Turkey’s sovereignty and territorial integrity persisted. Diplomacy was considered an elite profession, with TMFA recruiting only graduates of a highly select set of universities in Turkey.Footnote 76 Diplomats enjoyed a considerable degree of autonomy, operating within a foreign policy bureaucracy long shaped by military and bureaucratic tutelage, particularly through the dominance of the National Security Council (MGK) and the Office of General Staff in security-related decision-making.Footnote 77

This earlier period in Turkish diplomacy was also characterised by male dominance. Women constituted only 13.4 per cent of the career employees in 1990. In 1982, Turkey had its first and only female ambassador, Filiz Dinçmen, in The Hague. The country wouldn’t appoint another woman to the role until 1992. Occupational gender stereotypes characterising women as emotional and unable to keep secrets were common, and these stereotypical attributes were considered as constraining factors for women in diplomacy and liabilities in the defence of Turkish interests. In fact, the only notable mention of a woman diplomat in the published memoirs of male diplomats about this period is an anecdote about a female Turkish diplomat breaking down in tears when confronted by a Greek-Cypriot diplomat in 1975. In response, the author of the memoirs, her male superior, steps in as the masculine saviour to protect the honour and national interest of the Turkish state.

[I was informed that]: ‘In the Sub-Committee on the Protection of the Environment, the Greek Cypriot representative … claimed that Turks had burned all the forests in the region they had occupied and made very serious accusations against our country. The Turkish representative, on the other hand, was unable to respond to these charges and cried on the spot.’ I went to the Sub-Commission in question. Our representative lady was really crying and sobbing. The Greek Cypriot was silent. I had the power to take the floor in every committee due to my position as charge d’affaires. Our representative told the lady to sit somewhere in the back row, I sat at the table in a place allocated to our country, and as soon as I sat down, I asked the President about the ‘procedure’.Footnote 78

That emotional sensitivity, a prevalent gender stereotype about women, was not considered an asset in the profession in this period was also stressed by one of our male interviewees: ‘I do not recall that someone is praised for being a sensitive person. On the contrary, it is perceived as a sign of weakness’ (Interview 5). Consequently, women diplomats who entered the profession during this period recall being actively discouraged:

The Foreign Minister of the time was our neighbor when I entered the TMFA and he told me that ‘you have chosen a very difficult profession, this is not a woman’s profession, but a male profession’. I heard this with my own ears (Interview 6).

In this period, women diplomats faced difficulties in being promoted to the rank of ambassador and were generally assigned to consular services and administrative units as those tasks were perceived to be more suitable for women. In fact, in 1990, women constituted 23.25 per cent of the consulate and expert officers category, while they made up only 13.4 per cent of diplomatic staff. Rumours about women’s carelessness and failures were propagated to exclude women from important tasks. For example, only male diplomats were trusted to be diplomatic couriers, as a result of a circulating rumour that once a female diplomat went to the toilet and lost the courier bag. According to one of our interviewees, this unconfirmed incident that no one seemed to have first-hand knowledge about circulated as a rumour until 2003 and justified the exclusion of women from this task, which was considered to be a very prestigious one for young diplomats in the first two years of their profession (Interview 13).

Starting in the 2000s, Turkish foreign policy began to replace its reactive, unilateral, and coercive tactics with a more proactive diplomacy seeking peaceful and multilateral solutions to its problems. With the EU’s granting Turkey candidacy status in December 1999, Turkish foreign policy elite began to acknowledge the necessity as well the value of seeking diplomatic solutions to Turkey’s bilateral disputes, starting with Greece and Cyprus.Footnote 79 Recognising the need for specialised technical expertise to guide Turkey’s EU accession process, a new foreign policy bureaucracy, the General Secretariat for EU Affairs (EUGS), was created in 2000. Additionally, following the election of the Justice and Development Party (AKP) to power in 2002, especially during Ahmet Davutoglu’s tenure as advisor (2002–9) and foreign minister (2009–14) gaining recognition as a ‘soft power’Footnote 80 and expanding the scope of Turkish foreign policy to new regions such as Africa, the Middle East, Latin America, Asia, and the Pacific became priorities. From 2000 to 2012, TMFA opened forty-eight new overseas missions, mostly in African countries.Footnote 81 Turkish foreign policy began to encompass humanitarian, diaspora, public diplomacy, and nation branding initiatives.Footnote 82 Turkey also dramatically increased its humanitarian aid and official development assistance (ODA), from 71 million USD in 2003 to 785 million in 2011 and to almost 9 billion USD in 2020,Footnote 83 and became a leading donor country.Footnote 84 Thus, the salience and status of diplomatic work remained high as these changes were seen as necessary to buttress Turkey’s influence and status in international affairs.

However, the election of AKP to power in 2002 also spawned strong tensions between government and the old military/foreign policy elite, who suspected the former to be following an Islamist ideological agenda to dismantle Turkey’s pro-Western identity and foreign policy orientation and manipulating Turkey’s EU accession and reform process for its political advantage. As it consolidated power in the 2007 and 2011 elections, the AKP governments undertook various institutional measures to pluralise the foreign policy actors, empower independent specialised agencies relative to TMFA, reform the TMFA, and incrementally increase the role of the executive in foreign policy-making. For example, the EUGS was granted greater authority over the TMFA in leading Turkey’s EU accession process, and the scope of another independent agency, initially established in 1992, the Directorate for Economic, Cultural, and Technical Cooperation (TIKA), was expanded to the Middle East and North Africa, reflecting the diversification of Turkey’s foreign policy agenda.Footnote 85 In 2007, the Yunus Emre Institute was established to conduct cultural diplomacy.Footnote 86 In 2009, another specialised agency, Presidency for Turks Abroad and Related Communities (YTB) was established to govern relations with the Turkish diaspora and thereby to contribute to the ‘foreign policy, soft power, and public diplomacy’ activities of Turkey.Footnote 87 In July 2010, far-reaching reforms in the TMFA changed the organisational structure and the recruitment policies, allowing the entry of diplomats from more diverse educational and socio-economic backgroundsFootnote 88 and the appointment of non-career diplomats. Even as Turkey’s accession prospects waned, the EUGS was transformed into a separate ministry, Ministry for EU Affairs, in 2011, headed by AKP-affiliated bureaucrats.Footnote 89 In the same year, TIKA was reorganised through an executive order that increased its organisational and financial capabilities.Footnote 90

In the context of the tensions concerning the direction of Turkish foreign policy, President Erdoğan, like other populist leaders, sought to undermine the legitimacy of TMFA with a moral discourse that framed the diplomats as distant from and acting against the interests of the Turkish people. He frequently referred to diplomats as ‘mon chers’, a phrase that was so over-used by French-inspired late Ottoman elites in the nineteenth century that it acquired a derogatory connotation in the Turkish language as degenerately Westernised, alienated, snobbish, spoiled, and effeminate. For example, when retired diplomats criticised his spat at President Shimon Peres during the World Economic Forum meeting in 2009, Erdoğan angrily retorted, ‘I came from politics; I don’t know about the ways mon chers behave. And I don’t want to know.’Footnote 92

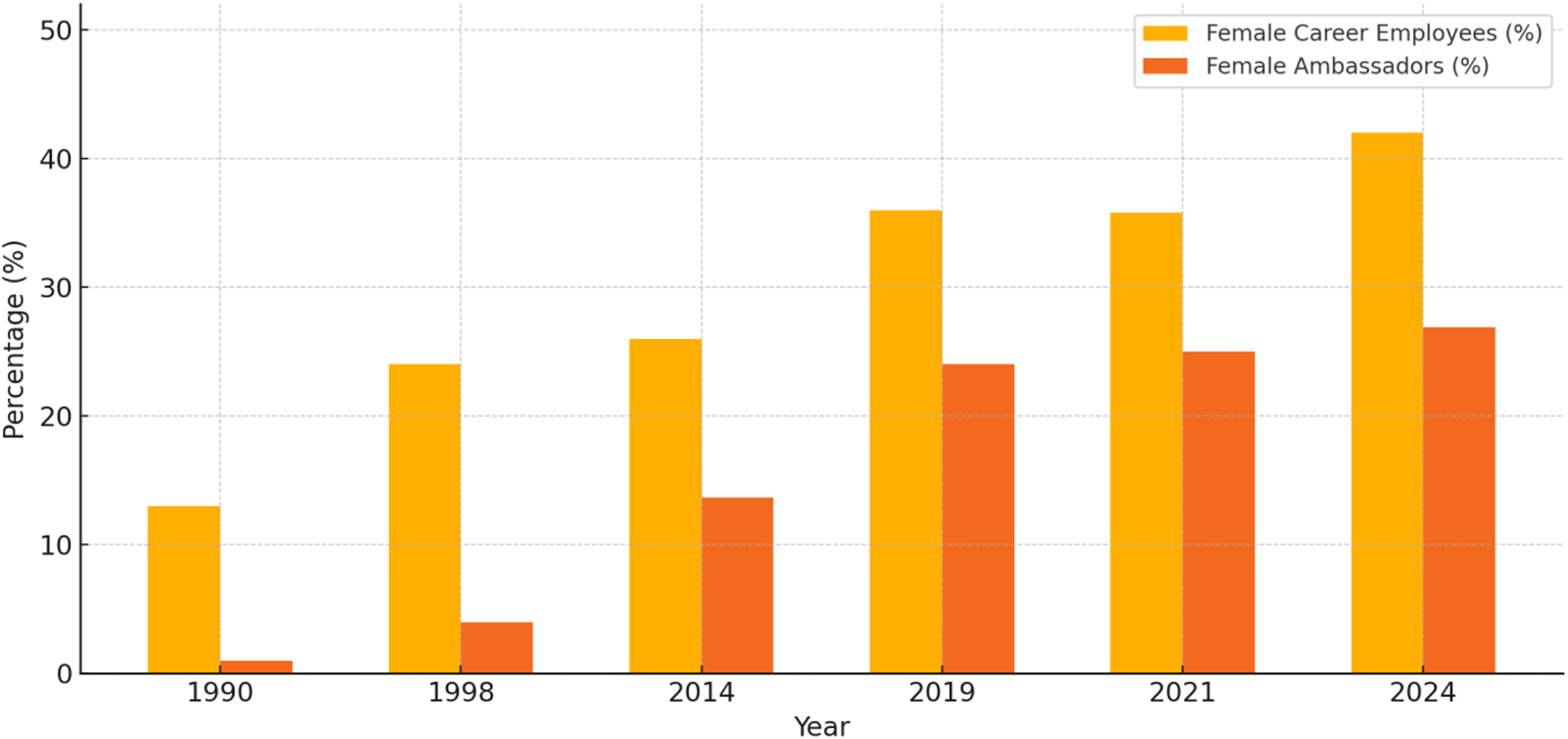

In the meantime, parallel to world trends, the gender make-up of TMFA started to change. TMFA adapted to the demands from the UN and the feminist movement in Turkey to encourage the recruitment of women into the profession, improve the gender make-up of Turkish diplomatic delegations (Interviews 2 and 3), and abolish policies that hindered women’s professional advancement, such as the ban on the appointment of diplomatic couples to the same city, in 1998. Consequently, as indicated in Figure 1, the proportion of women diplomats in diplomatic staff improved, rapidly rising from 13 per cent in 1990 to 24 per cent in 1998, and after remaining in that range in the 2000s and early 2010s, rose to 31 per cent in 2017,Footnote 93 to 36 per cent in 2019, and to 42 per cent in 2024. The gendered division of labour caused by the relatively higher representation of women diplomats in consular services also diminished and was eliminated by 2019. The proportion of women increased in every rank, including Head of Mission (ambassador or consul general), Directors General, or Deputy Directors General.Footnote 94 While women constituted only 9.6 per cent of all ambassadors in 2009, this ratio increased to 24 per cent in 2019 and to 27 per cent in 2024.

Figure 1. Female career employees and ambassadors in TMFA.Footnote 91

Our foreign policy has evolved towards a humanitarian and developmental foreign policy. In this context, it was understood that women could contribute more, and it turned out that they could be more successful (Interview 6).

As indicated in the above statement made by a female ambassador, both female and male diplomats we interviewed have underlined that a changed attitude towards women in diplomacy is dictated by the evolution of diplomacy and the new priorities of Turkish foreign policy. They consider that the rise of multilateralism has opened a wider space for women diplomats to excel on the basis of issue-based expertise on global issues, as opposed to bilateral diplomacy, where diplomats only transmit messages to the other party based on the instructions given to them. On the basis of gender-essentialist assumptions associating women diplomats with ‘feminine’ skills, both male and female interviewees have highlighted that women’s sensitivity, ‘humanist nature’, care for vulnerable groups such as women and children (Interviews 1, 2, and 3), and ‘integrity’ (Interview 11) facilitate better implementation of the responsibility to protect doctrine and effective management of humanitarian and public diplomacy, and foster greater responsiveness to global challenges, such as human trafficking, drugs trafficking, and combating corruption (Interview 3). It is recognised that women’s empathy, patience, and problem-solving skills allow them to better serve citizens abroad and conduct public diplomacy and nation branding initiatives. In contrast, male diplomats are characterised as less capable in conducting such tasks as they are less emotional.

Our interviewees have also characterised women diplomats as more ‘communicative’, ‘able to consider multiple dimensions of an issue’, ‘better at multi-tasking and handling multi-dimensional challenges’, ‘masters of problem solving’ (Interview 6), and better at networking and dealing with diverse audiences. Characteristics such as ‘flexibility’ and ‘mild temperament’ that are associated with female diplomats are considered as assets in reaching ‘win–win solutions’,Footnote 95 while ‘toughness’ and ‘rigidity’ are found to be limiting. It is also recognised that women diplomats benefit from gender-essentialising stereotypes in negotiation contexts, as they are treated more kindly and generously by their male colleagues. Male diplomats think twice before saying ‘no’ to a proposal from women, we were told (Interview 2).

In the words of a male diplomat interviewee:

… As women approach all issues in a more subtle and indirect way, they do not elicit confrontation. Especially if it is a large mission and a difficult task, women diplomats are preferred because men can get harsher reactions from their counterparts (male) (Interview 5).

This viewpoint is also endorsed by several other participants (Interviews 2 and 3) and the TMFA. This can be seen in their official communication of the ratio of the female personnel in the Ministry with the message ‘our ministry is stronger with women personnel’.Footnote 96

Thus, until roughly the mid-2010s, the AKP government’s incremental steps towards undermining the status of TMFA were largely offset by the growing ambition of Turkish foreign policy. The extension of Turkish foreign policy into humanitarianism, soft-power projection, and multilateral influence raised the value of female labour, preventing feminisation from leading to devaluation. However, subsequently, as the TMFA became much more gender-equal, Turkish politics became growingly authoritarian and foreign policy-making increasingly centralised around the Erdoğan presidency and his closed circle of advisors, starting with the forceful repression of Gezi protests in 2013, intensifying after the botched coup attempt in July 2016, and consolidating in the transition to a presidential system in 2017. Under the institutional structure of the presidential system, key foreign policy functions were absorbed by the presidency’s advisory bodies, the National Intelligence Organization (MIT), transferred from the Office of Prime Ministry, and the newly established Directorate of Communications. As President Erdoğan’s political confidantes assume the critical roles in advising and policy-making, the exclusive authority of the TMFA in the making of Turkish foreign policy diminished. This is recognised by a diplomat we interviewed:

There is the Presidential Foreign Affairs Chief Advisory. It is a department within the Ministry of Foreign Affairs. There is also the Presidential International Relations department. This includes various advisors close to Mr. Tayyip Erdoğan, whom he trusts. For example, a Presidential visit file is being prepared. Foreign Policy Chief Advisory is preparing but his advisor is also preparing. And both files are presented to our President. Such a duality still exists (Interview 11).

Also in his recently published memoirs, retired Ambassador Volkan Vural, who served in the TMFA from 1964 to 2006, laments that TMFA is no longer the ‘school of diplomacy’ that it was once widely regarded as:

The value of diplomacy depends on its power to influence political authority and its weight in decision-making processes. Institutions that merely implement decisions taken solely by political authorities, or that lack the power to influence and shape those decisions, cannot serve as schools of diplomacy.Footnote 97

As Figure 2 indicates, the decline in the status of TMFA is also reflected in its eroding budget allocation since 2010. Despite the rapid increase in the number of overseas missions, reflecting Turkey’s growing international ambition, the Ministry’s budget has remained stagnant, outpaced by inflation, especially when viewed alongside the significant budgetary growth of the Ministries of National Defense and Interior.

Figure 2. Budget of TMFA (2010–2024) compared to the Ministries of Interior and National Defense.Footnote 98

Meanwhile, Turkish foreign policy became increasingly unilateral, militaristic, and erratic. In the turbulent regional context caused by the Syrian civil war, the National Intelligence Agency (MIT) assumed critical foreign policy functions.Footnote 99 These trends overshadowed the prominence of those aspects of diplomatic work where ‘feminine’ skills are most appreciated, such as multilateral organisations and humanitarian diplomacy, even though they remain an important component of Turkish foreign policy. President Erdoğan fuelled a populist anti-Western discourse at home to legitimise Turkey’s growing alienation from traditional Western allies. In January 2020, an incident clearly demonstrated how far the government was ready to go to suppress any objections from diplomats. In reaction to President Erdoğan’s re-statement of his intention to construct a canal in Istanbul to divert the dangerous maritime traffic along the Bosphorus, 126 retired ambassadors issued a joint statement, warning the government that such a canal would violate the 1936 Montreux Convention, which gave Turkey control over the Straits and guards the delicate geopolitical balance in the Black Sea. This joint statement, even though issued by retired diplomats, was framed by high-ranking governmental officials as an attempt to re-institute bureaucratic tutelage and thus a threat to democratic order, an accusation that, in turn, prompted the Ankara Chief Public Prosecutor’s Office to launch of an ex officio investigation.Footnote 100

However, as the authority and responsibilities of the TMFA were thus curtailed, the ratio of women diplomats and ambassadors continued to grow. As we indicated in Figure 1, by 2021, women constituted 36 per cent of career diplomats and occupied 25 per cent of the 257 ambassadorial posts.Footnote 101 In 2024, the number of ambassadors further increased to 305, and the ratio of female ambassadors to 27 per cent.Footnote 102 Paradoxically, these improvements in gender representation occurred in the context of serious anti-gender interventions and the adoption of a conservative discourse advocating complementarity rather than equality between men and women by the AKP government.Footnote 103 Most notably, Turkey announced in 2021 that it is withdrawing from the Istanbul Convention, an international accord on the prevention of domestic violence that Turkey itself had pioneered in 2011. However, apart from the feminising connotations of the phrase ‘mon cher’, we have not identified in President Erdoğan’s discourse an explicit use of gendered stereotypes to disempower the TMFA.

In sum, the patterns we have identified in our historical sketch of the evolution of diplomacy in tandem with feminisation in the earlier section were largely manifest in the case of TMFA. Although Turkey’s transition from a classical to a polylateral mode of diplomacy was delayed to the 2000s, in line with our expectations, it supported the growing presence of women in Turkish diplomacy. In this period, feminisation did not lead to devaluation of diplomatic work. Despite incremental steps taken by the AKP governments towards constraining the authority of the TMFA, the growing diversification and ambition of Turkish foreign policy ensured that the status of diplomatic work remained high and, as clearly indicated by our interviewees, enhanced the value of female labour in diplomatic work. However, following the mid-2010s, a much more gender equal TMFA began to operate in a populist–authoritarian political context where its authority and autonomy are significantly curtailed and in a more unilateralist and militarist foreign policy context where ‘feminine’ diplomatic skills are less relevant. Thus, the two conditions that prevent feminisation from leading to devaluation – the high status of diplomatic work and high value of female labour in diplomatic work – are no longer as present.

Conclusion

The literature has studied the growing representation of women largely independently from other ongoing transformations in diplomacy and celebrated its progressive effects on diplomacy and global politics. Prompted by StephensonFootnote 104 and building on the large literature on occupational feminisation, in this article, we asked if the growing number of women in diplomacy could also have a negative consequence: the devaluation of diplomatic work itself. Applying the occupational feminisation literature to diplomatic work, we identified two conditions that inhibit devaluation: the overall status of diplomatic work and the value of female labour within it. We then analysed how the feminisation of diplomatic work has intersected with other transformations in diplomacy that affect these two conditions.

Our findings guard against a wholesale pessimistic conclusion that the greater representation of women in MFAs paves the way for the devaluation of diplomatic work. Any association between feminisation and devaluation is contingent on the presence of other factors influencing the status of diplomatic work. When the status of diplomatic work is high and/or rising, as it was in the evolution from classical to polylateral diplomacy, a virtuous cycle maintains the high status of diplomatic work and enhances the value of female labour, and consequently the entry of women in diplomacy in greater numbers did not trigger a devaluation. However, we caution that developments that reduce the status of diplomatic work, such as the current rise of populism, may set a context conducive for feminisation to reinforce the devaluation of diplomatic work. Populist discourse on MFAs as elitist institutions that hinder the will of the people and foreign policies that promote a deep distrust of international cooperation and institutions are bound to undermine the status of diplomatic work. Moreover, feminisation of MFAs allows populist executives to employ gendered discourse and hierarchies to diminish diplomatic work as ‘feminine’, while portraying their own unilateral and combative approach as ‘masculine’.

We have subsequently analysed how this pattern that we have postulated was manifested in TMFA. We found that the expanding scope and ambition of Turkish foreign policy in the 2000s supported a significant rise in women’s representation in TMFA and prevented devaluation even in the context of the government’s encroachments on TMFA’s authority. However, since the mid-2010s, a more gender-equal TMFA operates in a populist–authoritarian context where the status of diplomatic work and value of female labour are being eroded. While there is no direct evidence – in neither our interviews nor public discourse – of increased presence of women being perceived as independently devaluing diplomatic work, the safeguards identified in the occupational feminisation literature have definitely weakened.

In this respect, the re-election of Donald Trump to the US presidency is highly problematic for the future of increasingly feminised diplomatic work, given his distrust of bureaucratic expertise and shameless promotion of gender stereotypes. The steps that Donald Trump is likely to take towards diminishing the status and undermining the value of female labour in the US State DepartmentFootnote 105 will legitimise similar moves and rhetoric in other countries, and possibly drive a transition towards a populist mode of diplomacy at the systemic level. Under these conditions, it is incumbent upon scholars of gender and diplomacy to take the risk of devaluation seriously. Doing so does not implicate scholars in conservative arguments that gender-equality reforms should be halted or that the growing presence of women in diplomatic roles constitutes a liability. To the contrary, systematic theorisation of the scope conditions under which feminisation leads to devaluation and analysis of how these conditions materialise within diplomatic institutions operating in different political and cultural contexts would guard against letting untested assumptions crystallise into misguided policy prescriptions. In this respect, the primary policy lesson to be derived from this article is that gender equality in diplomacy should not be pursued as a stand-alone objective. Efforts to increase women’s representation must proceed alongside strategies that safeguard and strengthen the status of diplomatic work itself.

List of interviews

Interview 1: Male ambassador, 6 June 2016

Interview 2: Retired female ambassador, 16 May 2019

Interview 3: Retired female ambassador, 20 May 2019

Interview 4: Retired male ambassador, 22 May 2019

Interview 5: Retired male ambassador, 24 May 2019

Interview 6: Female ambassador, 11 June 2019

Interview 7: Retired female ambassador, 13 June 2019

Interview 8: Retired ambassador, 13 June 2019

Interview 9: Retired male ambassador, 20 November 2019

Interview 10: Retired female ambassador, 13 November 2019

Interview 11: Female undersecretary, 13 October 2019

Interview 12: Female ambassador, 12 May 2022

Interview 13: Female diplomat (former Consul-General), 22 May 2022

Interview 14: Female ambassador, 2 June 2022

Video Abstract

To view the online video abstract, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210525101708.

Acknowledgements

Earlier versions of this article were presented at the 2022 Gender and Diplomacy Workshop at the University of Gothenburg and at the 2025 Annual Convention of the International Studies Association. We thank the reviewers and editors of the journal for their detailed and constructive feedback.