Introduction

Smooth scouringrush is a deciduous rhizomatous perennial species in the genus Equisetum, which phylogenetically dates back more than 300 million years to the Carboniferous Period (Des Marais et al. Reference Des Marais, Smith, Britton and Pryer2003). Smooth scouringrush is endemic to North America (Hauke Reference Hauke1960) and primarily occurs east of the Cascade Mountains in Washington State (Palmer and Giblin Reference Palmer and Giblin2025). Management and control of smooth scouringrush in nonirrigated wheat-producing areas of the U.S. Pacific Northwest has been extremely difficult for farmers and land managers. Growers report that standard herbicide treatments associated with their wheat-based cropping systems are either ineffective at the time of application or they may provide some immediate burndown of aboveground stems, but control fails to extend into the following year (growers’ anecdotal observations). Previous research aligns with reports by growers on the lack of effective herbicide options. Rutz and Farrar (Reference Rutz and Farrar1984) reported that dense stands of Equisetum species in roadside ditches in Iowa were unaffected by heavy applications of herbicides, and the stands seemed to flourish from the lack of competition from the vegetation that the herbicides did control. Kerbs et al. (Reference Kerbs, Hulting and Lyon2019) found that nine of 10 herbicide treatments applied to smooth scouringrush during the summer fallow phase of a dryland wheat cropping rotation in eastern Washington had no effect on stem density 1 yr after treatment (YAT) compared with the nontreated check. Furthermore, growers report that smooth scouringrush has increased in their fields during the last 30 to 40 yr since no-till cropping systems were adopted. Dense stands of smooth scouringrush have been associated with reduced crop yields, interference with tillage or harvest operations, plugged drainage tiles, and seed coat staining of chickpea (Cicer arietinum L.) during harvest resulting in lower crop quality (conversations with growers).

Smooth scouringrush can root to depths greater than 2 m (Weaver Reference Weaver1958) and tends to occur in patches that can vary in size from a few square meters up to several hectares (personal observations). Reproduction occurs primarily through vegetative spreading of rhizomes but can sometimes occur sexually from spore germination if environmental conditions are favorable (Duckett and Duckett Reference Duckett and Duckett1980). Smooth scouringrush aboveground biomass consists of round hollow stems that are jointed and generally unbranched, and range in height from 20 to 150 cm with a spore-producing cone at the top (Hitchcock and Cronquist Reference Hitchcock and Cronquist1976). Nodes, or joints, on the stems are covered by a sheath with a single black band at the tip of the sheath. Stems have vertical ridges numbering 10 to 32 with stomates sunken between the ridges and occur in vertical rows near the base of each ridge (Cullen and Rudall Reference Cullen and Rudall2016; Palmer and Giblin Reference Palmer and Giblin2025). As stems mature during the growing season, they accumulate silica in the epidermis, which may have a structural role and may impede herbicide uptake (Lyon and Thorne Reference Lyon and Thorne2022; Sapei et al. Reference Sapei, Gierlinger, Hartmann, Nöske, Strauch and Paris2007).

Research into long-term control of smooth scouringrush in field crops is limited. Kerbs et al. (Reference Kerbs, Hulting and Lyon2019) found that chlorsulfuron + 2-methyl-4-chlorophenoxyacetic acid (MCPA) ester applied to smooth scouringrush stems in a chemical fallow phase of a dryland wheat cropping rotation near Reardan, Washington, resulted in 95% reduction of stem density 1 YAT; however, the effects of MCPA ester alone or tank mixed with other herbicides in the study were not effective or was not different from that of the nontreated check at 1 YAT. This would suggest that chlorsulfuron was primarily responsible for the herbicidal activity observed on smooth scouringrush in this research. Lyon and Thorne (Reference Lyon and Thorne2025) found that chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron applied to smooth scouringrush in chemical summer fallow maintained low stem density for 3 YAT at three sites in eastern Washington. In a similar and related species of scouringrush (Equisetum hyemale L.), Frasure and Bernards (Reference Frasure and Bernards2025) found that chlorsulfuron resulted in 100% control 1 yr after treatment in a greenhouse study; however, chlorsulfuron was applied at a high rate that damaged corn (Zea mays L.) and soybean [Glycine max (L.) Merr.] and would be above labeled rates for use on cereal crops.

Soil persistence of chlorsulfuron is variable depending on soil pH, and chlorsulfuron residues in soil can injure sensitive crops such as canola (Brassica napus L.) or pulse crops if planted back too soon following application. However, in the Pacific Northwest there are no plantback restrictions for wheat, rye (Secale cereale L.) or triticale (×Triticosecale Wittmack). The plantback interval is 24 and 36 mo for dry pea (Pisum sativum L.) and lentil (Lens culinaris Medik.), respectively, providing 889 and 1,270 mm of precipitation, respectively, has occurred since application (Hanson et al. Reference Hanson, Rauch and Thill2004). For sensitive crops such as canola or chickpea that are not listed on the label, a soil bioassay is required before planting.

Smooth scouringrush control using herbicides that contain chlorsulfuron could be an effective tool in wheat-based cropping systems that include chemical summer fallow; however, it is unknown how long control would last and when or whether growers would need to make follow-up applications to maintain control. In previous research, chlorsulfuron was applied during the chemical summer fallow phase because smooth scouringrush stems are more abundant and not competing with a wheat crop (Kerbs et al. Reference Kerbs, Hulting and Lyon2019; Lyon and Thorne Reference Lyon and Thorne2025). It is unknown whether applications of herbicides other than chlorsulfuron applied during the crop phases could extend smooth scouringrush control between chlorsulfuron applications in summer fallow. Triasulfuron is a sulfonylurea herbicide that can be applied during wheat crop phases and may be effective at controlling smooth scouringrush. Triasulfuron is of interest because it has similar molecular structure to chlorsulfuron but it does not persist as long in the soil (Hanson et al. Reference Hanson, Rauch and Thill2004). Objectives of this research were to 1) determine the efficacy of single and double applications of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron on long-term control of smooth scouringrush, and 2) evaluate the effects of applying triasulfuron during crop phases on the long-term control of smooth scouringrush.

Materials and Methods

Field Sites

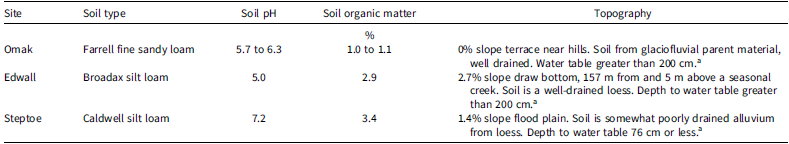

Field sites with infestations of smooth scouringrush were selected near Omak, Edwall, and Steptoe, Washington. Soil and topography differed at each site (Table 1). The Omak site was located on a relatively flat part of a field adjacent to steep hills with perennial vegetation being used for cattle (Bos taurus L.) grazing. Soil was a sandy loam that originated from glacial material with pH ranging between 5.7 and 6.3 and soil organic matter of 1%. The 30-yr average annual precipitation is 375 mm (NOAA 2025). The Edwall site was located near the bottom of a shallow draw that opens to a mostly level hay field approximately 160 m from a seasonal creek. The soil was a well-drained silt loam loess with pH of 5.9 and soil organic matter of 2.9%. The 30-yr average annual precipitation recorded at nearby Davenport, WA, is 353 mm (NOAA 2025). The Steptoe site was on a flood plain with somewhat poorly drained alluvium soil that originated from loess. The 30-yr average annual precipitation recorded at nearby St. John, WA, is 439 mm. At all three sites, about 65% of the annual precipitation occurs from October through March.

Table 1. Soil properties and topography at Omak, Edwall, and Steptoe, Washington, study sites comparing herbicide sequences for control of smooth scouringrush in wheat-based cropping systems.

a Source: USDA-NRCS (2019).

The Omak site was farmed using no-till management in a 2-yr cropping system of winter wheat followed by chemical summer fallow, subsequently referred to as just fallow. Normal field operations at Omak included herbicide applications in early spring and in summer prior to fall seeding, when needed, to control weeds and to preserve moisture during the fallow period. Winter wheat seeding occurred in late summer with a one-pass direct seed drill with shank-type openers on 30-cm spacing that applied liquid fertilizer near the seed. Seed was placed 5 to 10 cm deep into stored soil moisture. Liquid fertilizer was also applied in the spring as a top-dress application to the crop. The Edwall and Steptoe sites were farmed in 3-yr cropping systems with winter wheat followed by spring wheat followed by fallow. The Edwall site was farmed with no-till management with herbicides applied in spring of the fallow phase to control weeds that germinated through the winter, and twice during summer to control spring and summer germinating weeds prior to fall seeding in October. Winter and spring wheat were seeded 3 to 5 cm deep into moist soil and liquid fertilizer was applied near the seed with a one pass direct-seed drill with shank openers on 25-cm spacing. The Steptoe site was managed with a hybrid no-till system that used tillage in the fall following winter wheat to manage heavy straw residue and included a two-pass seeding system with fertilizer applied prior to seeding with a shank-type applicator. Winter and spring wheat were seeded into moisture using a direct seed drill 3 to 5 cm deep with double-disk openers on 25-cm spacing. At all three field sites, growers planted soft white or hard red winter wheat cultivars and soft white or dark northern spring wheat cultivars, depending on individual choices and strategies. At all three sites, a fallow year was included to increase and conserve soil moisture for the fall-seeded winter wheat crop because of the region’s semiarid climate (Schillinger and Papendick Reference Schillinger and Papendick2008).

Field Trials

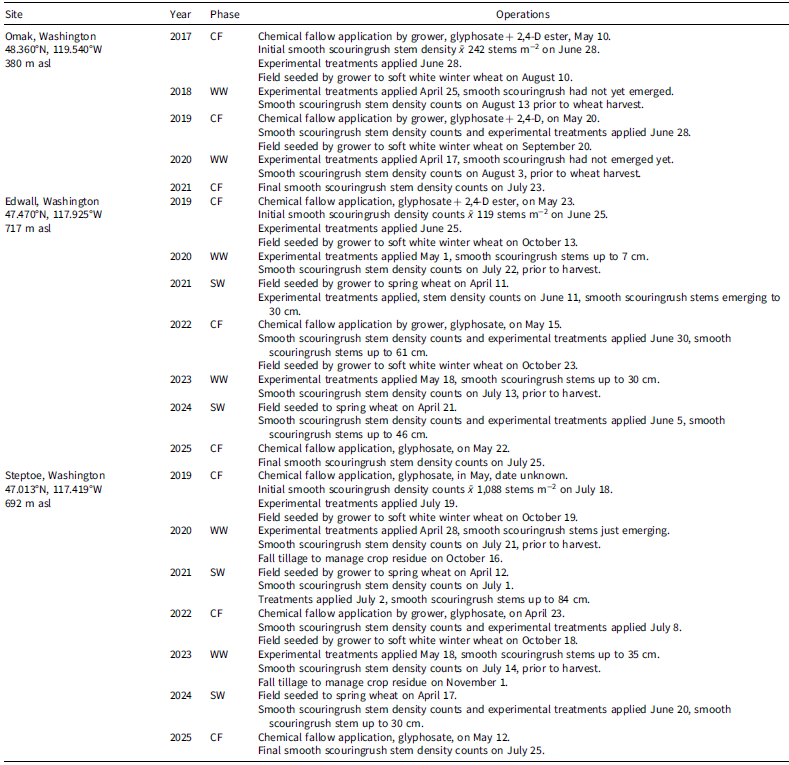

All three field trials were initiated during the fallow phase of each respective crop rotation. Each cooperator applied herbicides prior to trial initiation as part of their normal fallow management (Table 2). At Omak, our study included two cycles of the winter wheat/fallow rotation (2017–2018 and 2019–2020) and concluded with a final stem density evaluation in 2021. The Edwall and Steptoe studies included two crop cycles of the winter wheat/spring wheat/fallow rotation (2019–2021 and 2022–2024) and concluded with final stem density evaluations in 2025. The cooperating grower at each site applied glyphosate at rates between 866 and 945 g ha−1 in spring to control winter annual weeds and volunteer wheat prior to planting spring crops or for fallow weed control (Table 2). Glyphosate was applied before smooth scouringrush stems emerged, which generally occurred in late May, and would not have had any effect on smooth scouringrush density in the spring crops or the fallow.

Table 2. Field operations in each rotational phase at the study sites. a

a Abbreviations: asl, above sea level; CF, chemical fallow; SW, spring wheat; WW, winter wheat.

The Omak trial was initiated on June 28, 2017, the Edwall trial on June 25, 2019, and the Steptoe trial on July 18, 2019 (Table 2). The experimental design at each site was a randomized complete block with 3.0- by 9.1-m plots and each treatment was replicated four times. At the time of initial application, smooth scouringrush appeared green and healthy and ranged in stem height from 30 to 76 cm with most stems having a spore-bearing cone at the top of the stem. Initial stem densities averaged 242, 119, and 1,088 stems m−2 at Omak, Edwall, and Steptoe, respectively. All experimental herbicides were applied with a CO2-pressurized backpack sprayer and a 3-m hand-held spray boom with six nozzles on 51-cm spacing and 1.3 m s−1 groundspeed. Nozzles used in applications from 2017 to 2021 were XR11002 (TeeJet Technologies, Glendale Heights, IL) at 172 kPa application pressure, while treatments applied 2022–2024 used TeeJet AIXR110015 nozzles at 276 kPa application pressure for improved drift control. All treatments were applied at a spray volume of 140 L ha−1.

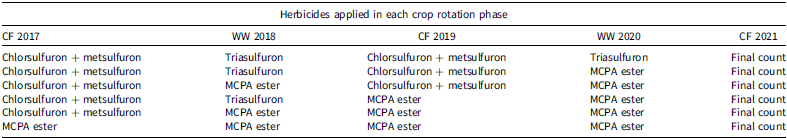

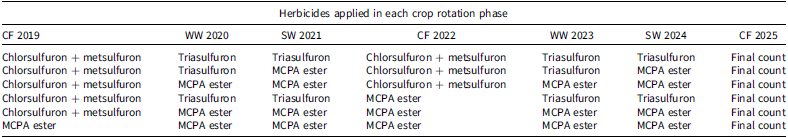

Experimental treatments included chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron (Finesse Cereal and Fallow Herbicide; FMC Corporation, Philadelphia, PA) at 26.3 g ai ha−1 (21.9 g ai ha−1 chlorsulfuron + 4.4 g ai ha−1 metsulfuron), triasulfuron (Amber; Syngenta Crop Protection, Greensboro, NC) at 29.5 g ai ha−1, and MCPA ester (Rhonox; Nufarm, Inc., Burr Ridge, IL) at 780 g ae ha−1 when applied in crop and 1,122 g ha−1 when applied in fallow. MCPA ester was applied as a chemical check treatment for control of weeds other than smooth scouringrush. Kerbs et al. (Reference Kerbs, Hulting and Lyon2019) found that MCPA ester initially burns down smooth scouringrush stems following application but does not reduce density in subsequent years. All experimental treatments included a nonionic surfactant (M-90; The McGregor Company, Colfax, WA) at 3.3 mL L−1. Maintenance treatments, when needed, included glyphosate (RT 3; Bayer CropScience, St. Louis, MO) and 2,4-D ester (2,4-D LV6; Albaugh Inc., Ankeny, IA). Herbicide treatments at Omak (Table 3), and Edwall and Steptoe (Table 4), consisted of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron applied initially in fallow to all plots except the MCPA ester check plots, and then only in half of the plots in the second fallow phase.

Table 3. Herbicide treatment sequences in a long-term smooth scouringrush control study in a winter wheat/chemical fallow rotation study near Omak, Washington. a, b

a Abbreviations: CF, chemical fallow; WW, winter wheat.

b Chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron was applied at 21.9 + 4.4 g ai ha−1; triasulfuron was applied at 29.5 g ai ha−1; MCPA ester was applied at 1,122 g ae ha−1 in chemical fallow and 780 g ae ha−1 in crop. All treatments included a nonionic surfactant at 3.3 mL L−1 concentration.

Table 4. Herbicide treatment sequences in a long-term smooth scouringrush control in a winter wheat/spring wheat/chemical fallow rotation study near Edwall and Steptoe, Washington. a, b

a Abbreviations: CF, chemical fallow; SW, spring wheat; WW, winter wheat.

b Chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron was applied at 21.9 + 4.4 g ai ha−1; triasulfuron was applied at 29.5 g ai ha−1; MCPA ester was applied at 1,122 g ae ha−1 in chemical fallow and 780 g ae ha−1 in crop. All treatments included a nonionic surfactant at 3.3 mL L−1 concentration.

Data Collection

Treatments were evaluated by counting stem density in each plot each year following initial applications. Stems were counted in two 1-m2 subsamples per plot. In the crop phases, stems were counted prior to harvest, while in fallow phases, stems were counted in mid-July. In crop phases, plots were harvested using a small-plot combine and samples were bagged, cleaned, and analyzed for weight, test weight, and moisture content. Yields were calculated on a 12% moisture basis and reported as kilograms per hectare (kg ha−1).

Statistical Analysis

Count and crop harvest data were analyzed using generalized linear mixed models (the GLIMMIX procedure) with SAS/STAT software (v.9.4; SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC). Count data from the Omak site were analyzed separately from the Edwall and Steptoe sites because the Omak site was in a 2-yr winter wheat/fallow rotation and the Edwall and Steptoe sites were both in a 3-yr winter wheat/spring wheat/fallow rotation. Fixed effects were site (SITE), year (Year), and herbicide treatment (TRT). Random effects for count data were subsample (SUB) and replication (REP). The random effect for yield data was REP. Stem density counts were square root transformed and analyzed using the GLIMMIX procedure as a normal distribution with the LaPlace method of maximum likelihood estimation and the containment method for assigning degrees of freedom. Assumption of normality was verified for each analysis by visually examining residual histograms of studentized residuals produced in GLIMMIX and confirming that skewness and kurtosis values of studentized residuals were within 2± and 7±, respectively (Curran et al. Reference Curran, West and Finch1996). Differences between least squares means were identified using pair-wise comparisons produced by the SLICEDIFF option (P ≤ 0.05) within the GLIMMIX procedure. Multiple comparisons were adjusted using the Tukey-Kramer adjustment. Least squares means were back-transformed for presentation. The SLICEDIFF option in the GLIMMIX procedure performs pairwise comparison of simple effects (SAS/STAT 2020). The full model for analyzing the Omak count data was YEAR*TRT with a random statement of Random Intercept/Subject SUB(REP). Least squares means were compared for Omak using the statement LSMEANS YEAR*TRT/SLICEDIFF=YEAR adjust=Tukey, or LSMEANS YEAR*TRT/SLICEDIFF=TRT adjust=Tukey. The full model for the Edwall and Steptoe count data was YEAR*SITE*TRT with a random statement of Random Intercept SITE/Subject SUB(REP). Least squares means were compared for Edwall and Steptoe using the statement LSMEANS YEAR*SITE*TRT/SLICEDIFF=YEAR*SITE adjust=Tukey, or LSMEANS YEAR*SITE*TRT/SLICEDIFF=SITE*TRT adjust=Tukey. Full model test of fixed effects for Omak, and for Edwall and Steptoe, were significant (P < 0.001) for each effect, therefore, treatments were assessed using simple effects.

Crop yield data for Omak were analyzed separately from Edwall and Steptoe because of the rotational differences but with the same models used for count data without the SUB random effect. Yield data were not transformed because they were following the normality assumption based on studentized residual histograms and skewness and kurtosis. Fixed effects for the Omak data were not significant for YEAR*TRT (P = 0.914) or TRT (P = 0.443); however, YEAR was significant (P < 0.001). The Edwall and Steptoe fixed effects were significant for SITE*TRT (P = 0.033), therefore, overall TRT differences were analyzed for each SITE using SLICEDIFF=SITE or for TRT using SLICEDIFF=TRT in the GLIMMIX LSMEANS statement. The SITE*YEAR effect was also significant (P = 0.002) and was analyzed using the SLICEDIFF=SITE option in the GLIMMIX LSMEANS statement. Figures were prepared using SigmaPlot software (v.15; Grafiti LLC, Palo Alto, CA).

Results and Discussion

At all three sites, treatment sequences with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron followed by triasulfuron were not different (P > 0.05) from sequences with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron followed by MCPA ester (data not shown), therefore, sequences with a single application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron and MCPA ester were used to determine the long-term efficacy of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron.

Smooth Scouringrush Stem Densities at Omak

Chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron. At Omak, the interaction between YEAR and TRT was significant (P < 0.001), thus smooth scouringrush stem density could be assessed by comparing simple effects.

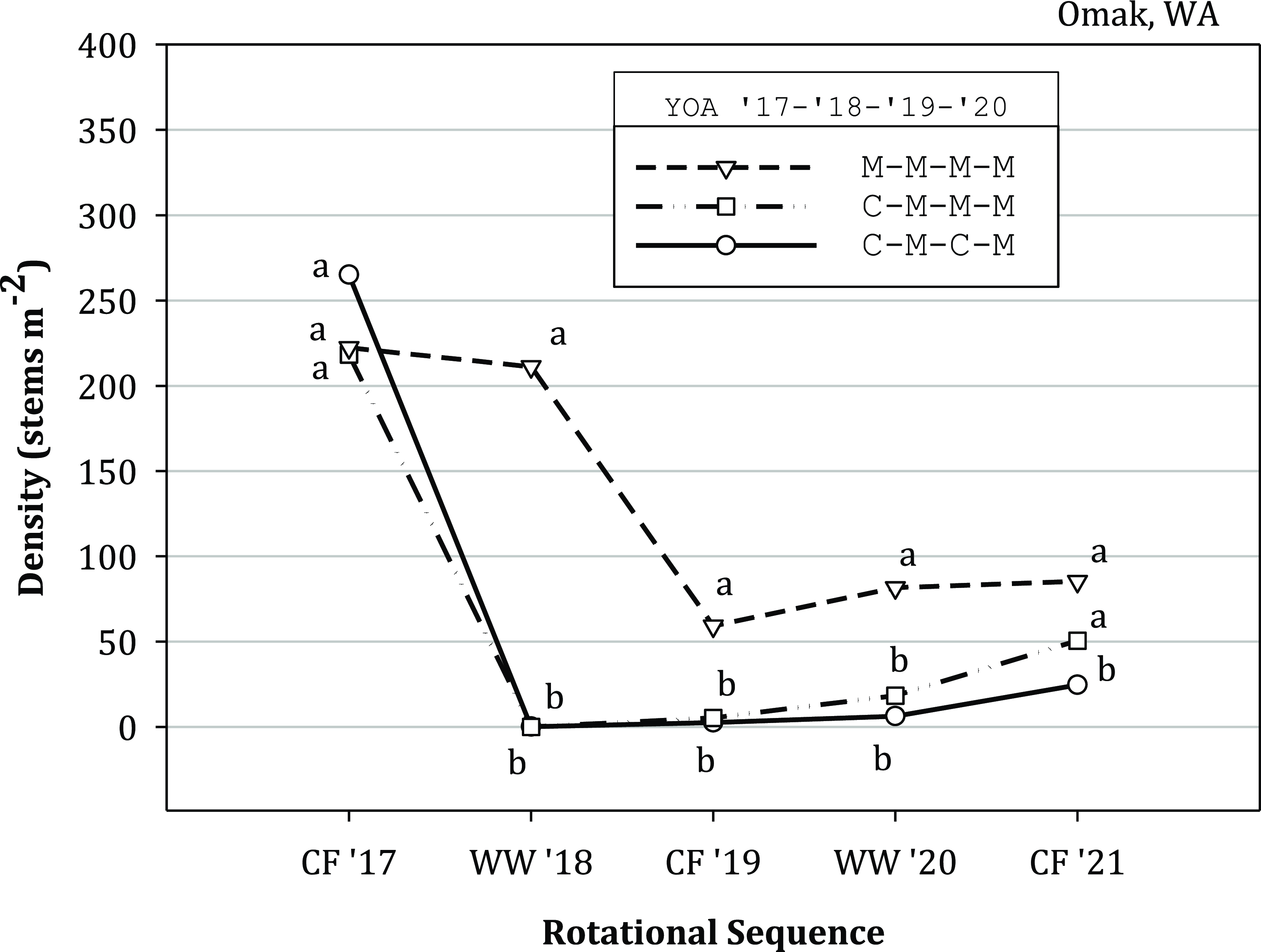

In 2018, 1 YAT, smooth scouringrush density was reduced to 0 stems m−2 after treatments with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron smooth scouringrush, which was substantially less than the MCPA ester check sequence that averaged 211 stems m−2 (Figure 1). This result is consistent with findings by Kerbs et al. (Reference Kerbs, Hulting and Lyon2019) who reported that smooth scouringrush stem density was near zero 1 YAT following a chlorsulfuron application in chemical fallow.

Figure 1. Smooth scouringrush control at Omak, Washington, with three different herbicide sequences over two cycles of a winter wheat/chemical fallow rotation. Years of application (YOA) include 2017–2020. Control was measured in stem density per square meter. Crop rotation sequences included chemical fallow phases in 2017 (CF’17) and 2019 (CF’19), winter wheat in 2018 (WW’18) and 2020 (WW’20). Final evaluations were carried out during chemical fallow in 2021 (CF’21). Herbicides in each sequence included MCPA ester (M) at 780 g ae ha−1 applied to wheat and 1,122 g ae ha−1 during chemical fallow, or chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron (C) applied at 21.9 + 4.4 g ai ha−1. All applications included a nonionic surfactant at 3.3 mL L−1. Stem densities per square meter are compared between herbicide sequences for each year using pair-wise comparison of LSMEANS using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS software. LSMEANS with the same letter for each year are not different (P ≤ 0.05). Comparisons of LSMEANS between years are stated in the text where appropriate.

In 2019, only 2 stems m−2 were present in the sequence that received a second chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron application; however, this density was not different from that of the sequence with a single application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron applied in 2017, which averaged 5 stems m−2 (Figure 1). These densities were substantially lower than the initial site average densities of 242 stems m−2 in 2017. Smooth scouringrush density in the MCPA ester check sequence averaged 59 stems m−2, which was also less than in 2017 or 2018 (P < 0.001) but greater than all other treatments in 2019.

In 2020, the single application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron in 2017 resulted in an average of 18 stems m−2, which was not different from 5 stems m−2 in 2019 (P = 0.198) (Figure 1). The sequence with chlorsulfuron applied in both chemical fallow phases averaged 6 stems m−2 and was also not different from 2019 when 2 stems m−2 were recorded (P = 0.323). The density after both sequences with chlorsulfuron were not different from each other but were lower than the MCPA ester check sequence, which averaged 82 stems m−2. The lack of difference between sequences with chlorsulfuron would indicate that control had lasted 3 YAT for that sequence treated in 2017. This is consistent with findings reported by Lyon and Thorne (Reference Lyon and Thorne2025) who observed control 3 YAT in wheat-based cropping systems in eastern Washington.

In 2021, 4 yr after the initial applications, the greatest densities were counted in the MCPA ester check sequence, which averaged 85 stems m−2, and the sequence with a single application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron in 2017, which averaged 50 stems m−2. The sequence with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron applied in both 2017 and 2019 resulted in the lowest density, which averaged 25 stems m−2; however, this stem density, 2 YAT in the second rotation cycle, was greater than the density 2 YAT in the first rotation cycle, which averaged 0 stems m−2 (P = 0.003). This outcome suggests that low stem density at the time of application, as was observed in the second fallow phase, could result in reduced control in the years following application. Furthermore, the reduced efficacy following the second application would suggest that root uptake was not an important factor. Leys and Slife (Reference Leys and Slife1988) found that both chlorsulfuron and metsulfuron were less effective in controlling wild garlic when applied only to soil than when applied to foliage or foliage and soil.

In the Omak trial, one application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron was effective for reducing stem density for at least 3 YAT and an application in the second fallow year helped maintain lower density but was not as effective as the first application.

Triasulfuron. Final stem density counts in 2021 found no difference between treatment sequences with triasulfuron, which averaged 31 stems m−2, and treatment sequences with no triasulfuron, which averaged 37 stems m−2 (data not shown). However, the greatest density, 85 stems m−2, occurred after application of the MCPA ester check sequence. Note that in both 2018 and 2020, triasulfuron was applied to winter wheat before the smooth scouringrush had emerged, so there would have been no chance for foliar uptake to occur.

Smooth Scouringrush Stem Densities at Steptoe

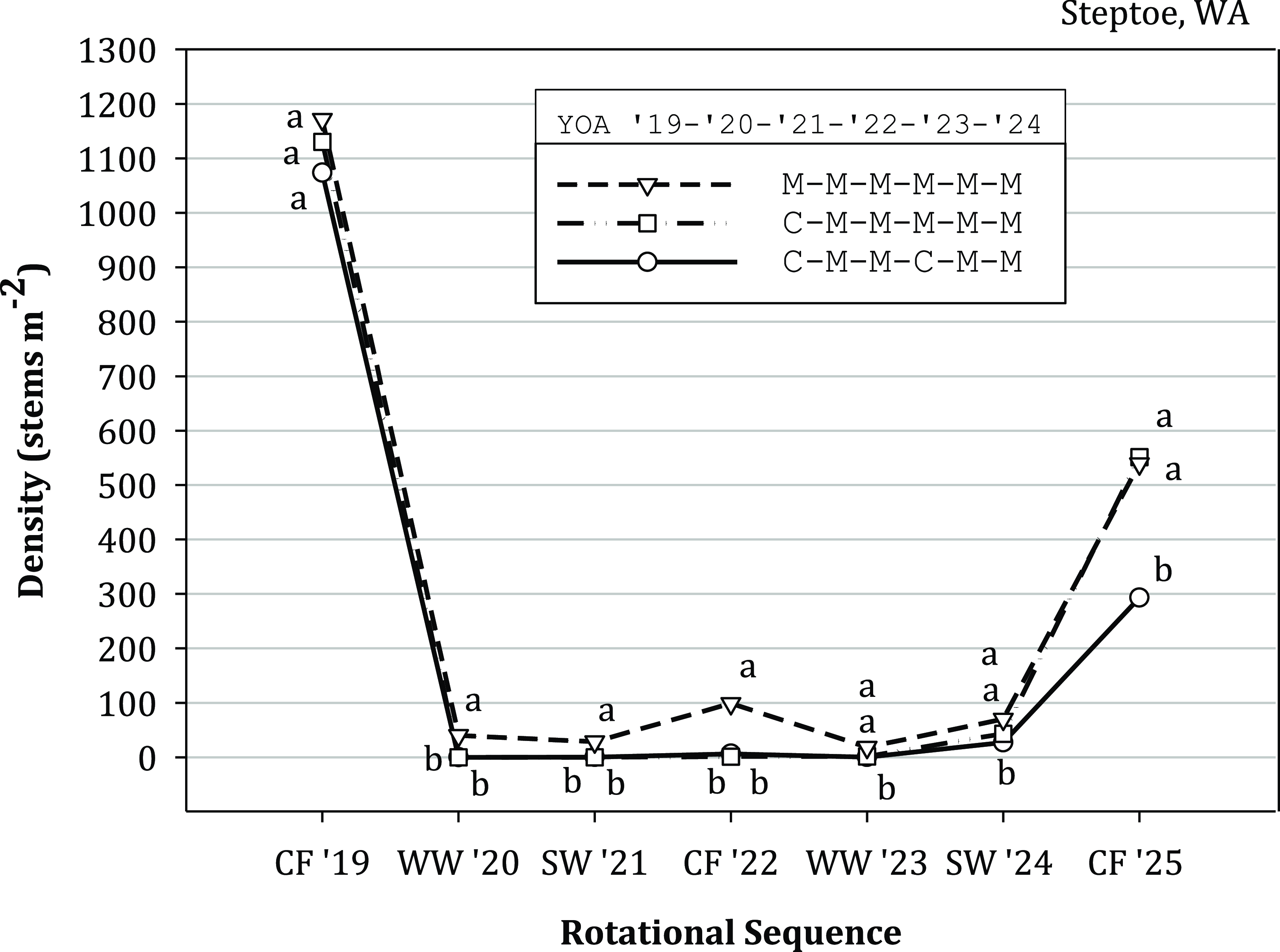

Chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron. Although the Edwall and Steptoe trials were both in a 3-yr winter wheat/spring wheat/fallow rotation, several key differences stood out. Initial smooth scouringrush density at Steptoe averaged 1,088 stems m−2 compared with 119 stems m−2 at Edwall (data not shown). Additionally, the interaction YEAR*SITE*TRT was highly significant (P < 0.001); therefore, comparisons could be made between simple effects for each SITE. At Steptoe, treatment sequences with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron applied in 2019 maintained low stem density through the first crop rotation cycle (2019–2021) and into the second fallow phase in 2022 (Figure 2).

Figure 2. Smooth scouringrush control at Steptoe, Washington, with three different herbicide sequences over two cycles of a winter wheat/spring wheat/chemical fallow rotation. Years of application (YOA) include 2019–2024. Control was assessed in stem density per square meter. Crop rotation sequences included chemical fallow phases in 2019 (CF’19) and 2022 (CF’22), winter wheat in 2020 (WW’20) and 2023 (WW’23), and spring wheat in 2021 (SW’21) and 2024 (SW’24). Final evaluations were conducted during chemical fallow in 2025 (CF’25). Herbicides in each sequence included MCPA ester (M) applied at 780 g ae ha−1 to wheat and 1,122 g ae ha−1 during chemical fallow, or chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron (C) applied at 21.9 + 4.4 g ai ha−1. All applications included a nonionic surfactant at 3.3 mL L−1. Stem densities per square meter are compared between herbicide sequences for each year using pair-wise comparison (P ≤ 0.05) of LSMEANS using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS software. LSMEANS with the same letter for each year are not different (P ≤ 0.05). Comparisons of LSMEANS between years are stated in the text where appropriate.

In 2020, 40 stems m−2 of smooth scouringrush were counted after the MCPA ester check sequence, which was substantially less than the initial density of 1,172 stems m−2 (P < 0.001) but still greater than sequences with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron (Figure 2). It is unclear whether MCPA ester was controlling smooth scouringrush or whether winter wheat competition in 2020 had diminished the stem density. Kerbs et al (Reference Kerbs, Hulting and Lyon2019) found that MCPA ester applied to smooth scouringrush in chemical fallow had no effect on stem density 1 YAT.

In 2021, no differences in outcomes were observed compared with 2020. However, in 2022, chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron was applied to 6 stems m−2 in the sequence that received a second application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron, which was much less that the 1,074 stems m−2 at the initial application in 2019. In the sequence with no second application, density in 2022 averaged only 1 stem m−2 (Figure 2). Stem density for the MCPA ester check sequence averaged 99 stems m−2 and was greater than both sequences with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron. This outcome is similar to that in Omak where chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron was applied to a much lower stem density during the second fallow phase because stem density had not increased following the initial chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron application.

Smooth scouringrush density in the 2023 winter wheat crop was low in all sequences, which may have been due to winter wheat competition; however, density in the MCPA ester check sequence averaged 18 stems m−2 and was not greater than the sequences with a single application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron in 2019, which averaged 2 stems m−2 (Figure 2). Smooth scouringrush density in the sequence where chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron had been applied in 2019 and 2022 averaged 0 stems m−2, which was lower than the single-application sequence or the MCPA ester check sequence. At this point, the single application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron in 2019 was not demonstrating control of smooth scouringrush better than the MCPA ester check.

Smooth scouringrush density in the 2024 spring wheat crop averaged 43 stems m−2 in the sequences with a single application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron in 2019, which was not different from 70 stems m−2 in the MCPA ester check sequence (Figure 2). Both were greater than the sequence with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron applied twice, which averaged 27 stems m−2. However, smooth scouringrush in both sequences with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron had increased from 2023 (P < 0.01). This suggests that control from chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron, whether applied only in 2019 or in 2019 and 2022, was beginning to decline, and the re-application in 2022 was less effective 2 YAT than the 2019 application was 2 YAT.

In 2025, the sequence with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron applied in both fallow phases averaged 296 stems m−2, which was less than the sequence with the single application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron in 2019, which averaged 551 stem m−2 or the MCPA ester check sequence that averaged 539 stems m−2 (Figure 2). Even though stem density was lower when chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron was applied in consecutive fallow phases, control 3 YAT in the second rotation cycle was less effective than control 3 YAT in the first rotation cycle (P < 0.001). It may have been more effective to wait until the third rotation cycle to apply chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron, when stem density may have been greater and there would likely have been more foliar uptake.

Smooth Scouringrush Stem Densities at Edwall

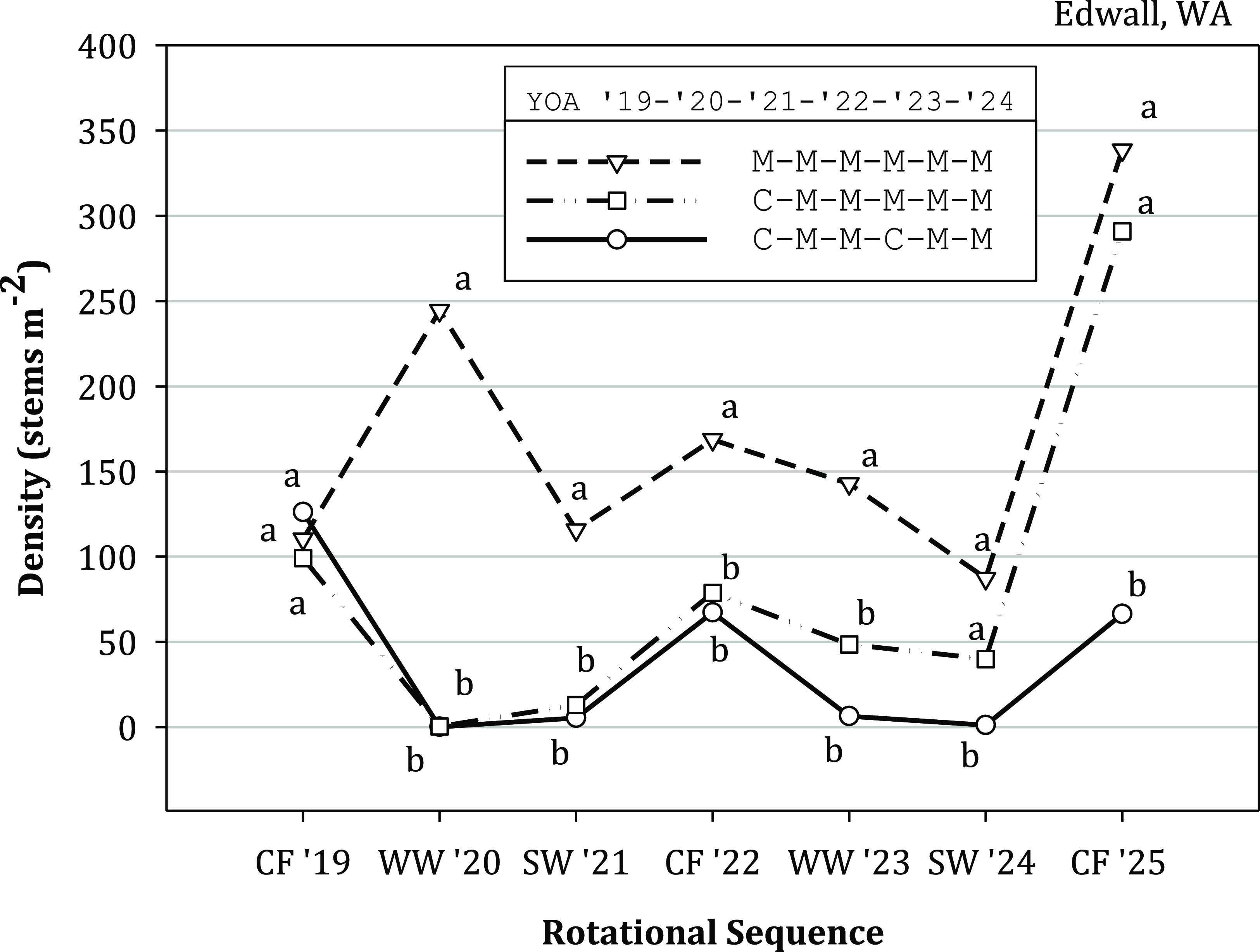

Chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron. During the first rotation cycle, treatment sequences with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron applied in 2019 resulted in zero smooth scouringrush density in 2020 compared with an average of 244 stems m−2 in the MCPA ester check sequence (Figure 3). This outcome was similar to the results observed in Omak and Steptoe, and that described by Kerbs et al. (Reference Kerbs, Hulting and Lyon2019). However, a slight increase in density occurred in both sequences with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron by 2022 (Figure 3). This was different from what was observed at Omak and Steptoe where density remained near zero for 3 YAT.

Figure 3. Smooth scouringrush control at Edwall, Washington, with three different herbicide sequences over two cycles of a winter wheat/spring wheat/chemical fallow rotation. Years of application (YOA) include 2019–2024. Control assessed in stem density per square meter. Crop rotation sequences included chemical fallow phases in 2019 (CF’19) and 2022 (CF’22), winter wheat in 2020 (WW’20) and 2023 (WW’23), and spring wheat in 2021 (SW’21) and 2024 (SW’24). Final evaluations were carried out during chemical fallow in 2025 (CF’25). Herbicides in each sequence included MCPA ester (M) applied at 780 g ae ha−1 to wheat and 1,122 g ae ha−1 during chemical fallow, or chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron (C) applied at 21.9 + 4.4 g ai ha−1. All applications included a nonionic surfactant at 3.3 mL L−1. Stem densities per square meter are compared between herbicide sequences for each year using pair-wise comparison (P ≤ 0.05) of LSMEANS using the GLIMMIX procedure in SAS software. LSMEANS with the same letter for each year are not different (P ≤ 0.05). Comparisons of LSMEANS between years are stated in the text where appropriate.

During the second rotation cycle (2022–2024), chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron was re-applied in fallow in 2022 to 67 stems m−2 in the sequence that included a second application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron, which had increased from 5 stems m−2 in 2021 (P = 0.021) (Figure 3). In the sequence with only a single chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron application, density averaged 79 stems m−2 but it was not different from 13 stems m−2 in 2021 (P = 0.057). However, both sequences with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron resulted in lower density than the MCPA ester check sequence, which averaged 169 stems m−2.

In 2023, the second application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron in 2022 led to a reduction in density from 67 stems m−2 to 6 stems m−2 (P = 0.015) (Figure 3). The sequence with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron applied only in 2019 averaged 48 stems m−2 in 2023 and was not different from the density in 2022 (P = 0.920). The sequence with a single application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron in 2019 was not different from the sequence with a second application in 2022 but it was different from the MCPA ester check, which averaged 143 stems m−2. This outcome differs from that in Steptoe where the single application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron exhibited no control of smooth scouringrush 4 YAT compared with the MCPA ester check.

In 2024, smooth scouringrush density averaged 1 stem m−2 in the sequence with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron applied twice, which was lower in density than the sequence with only one application, which averaged 40 stems m−2 (Figure 3). Both sequences with chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron had lower density than the MCPA ester check sequence, which averaged 87 stems m−2. This outcome was similar to that in Steptoe where a second application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron improved long-term control and that a single application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron was not different from the MCPA ester check sequence. The lower density in 2024 in the sequence with two applications of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron was likely due to greater foliar uptake from greater stem density at the time of the second application in 2022 at the Edwall site compared with the Steptoe site.

In 2025, smooth scouringrush density where chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron was applied in both chemical fallow phases had the lowest density, averaging 66 stems m−2 but was an increase from 1 stem m−2 in 2024 (P < 0.001) (Figure 3). The sequence of a single application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron in 2019 averaged 291 stems m−2 and was not different from the MCPA ester check sequence, which averaged 339 stems m−2. Density in the sequence with only one chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron application increased 628% from 2024, which would indicate that control was lost and that environmental conditions were favorable for stem emergence; therefore, the second chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron application was necessary to maintain long-term control. However, the chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron application in the second rotation cycle that resulted in 66 stems m−2 3 YAT was not different from the density 3 YAT in the first rotation cycle, which averaged 67 stems m−2 (P = 1.000). Chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron did maintain relatively low smooth scouringrush density for at least 3 YAT at all three sites. This is consistent with previous research by Lyon and Thorne (Reference Lyon and Thorne2025); however, results from Edwall indicate that control can extend to 4 YAT in some situations. Efficacy of the initial application may vary, but efficacy of the second application may depend on the number of stems present at the time of herbicide application.

Triasulfuron. As observed at the Omak site, triasulfuron did not control smooth scouringrush at Steptoe or Edwall compared with the MCPA ester check. However, unlike Omak, treatments with triasulfuron at both Steptoe and Edwall were applied to emerged stems that were at least 30 cm tall. This would suggest that foliar uptake of triasulfuron was limited at the time of application or at the rate applied.

Crop Yields

Differences in winter wheat yield at Omak were significant for YEAR (P < 0.001) and averaged 1,940 and 4,180 kg ha−1 in 2018 and 2020, respectively; however, there was no TRT effect (P = 0.443) or YEAR*TRT interaction (P = 0.914) (data not shown).

At Edwall and Steptoe, the three-way interaction of YEAR*SITE*TRT for crop yield was not significant (P = 0.949); however, the SITE*TRT interaction (P = 0.033) was significant, therefore, yields were combined over years to analyze the SITE*TRT interaction. At Steptoe, there was no difference in yield between TRT, which ranged from 5,030 to 5,330 kg ha−1 between TRT and averaged 5,220 kg ha−1 overall. However, at Edwall, the MCPA ester check sequence yielded less than all other sequences with an average of 3,580 kg ha−1 compared with all other sequences combined, which averaged 4,340 kg ha−1 and ranged from 4,210 to 4,530 kg ha−1.

The difference in yield with relation to TRT between Edwall and Steptoe was likely that the smooth scouringrush at Edwall in the MCPA ester check sequence tended to be greater in density (Figure 2 vs. Figure 3) and more competitive compared with the density at Steptoe. Lack of TRT effect at Steptoe was likely due to competition from wheat in addition to low smooth scouringrush density at each crop harvest (Figure 2). Smooth scouringrush interference with wheat is variable but can result in lower yields if smooth scouringrush stem densities are high or crop competition is low, or more likely, a combination of both.

Practical Implications

Growers who have trouble controlling smooth scouringrush in their wheat cropping systems can benefit from chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron applied to stems of the weed in chemical fallow. During fallow, smooth scouringrush stems persist because they are not competing with crops and have not been controlled with herbicides commonly used in chemical fallow. Results from these long-term, multisite studies in wheat cropping systems support previous studies demonstrating that chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron can control smooth scouringrush for at least 3 YAT. Furthermore, this research found that a reduction in smooth scouringrush stem density can extend up to 4 YAT when compared to herbicide sequences that do not contain chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron. A second application of chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron in a subsequent fallow year can extend control, but control is greater when more stems are present at the time of the second application. If few stems are present in a subsequent fallow year, it may be more effective to wait until the next fallow year to apply chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron. Triasulfuron was not able to control smooth scouringrush when it was applied in-crop and should not be applied with the intent of providing smooth scouringrush control between chemical fallow phases. While smooth scouringrush has inconsistent effects on wheat yield, it can cause other issues such as interfering with farming operations and plugging tile drainage systems; therefore, reducing its impact would be an overall benefit. Growers also need to keep in mind that if they apply chlorsulfuron + metsulfuron and plan to plant crops other than wheat, they need to check plantback intervals before seeding those crops.

Acknowledgments

We thank Edd Townsend, Jennifer and Justin Camp, and Mark Hall for being great cooperators and providing field sites for our long-term research.

Funding

This research was partially funded by an endowment from the Washington Grain Commission and by the U.S. Department of Agriculture–National Institute of Food and Agriculture, Hatch project 7003737.

Competing interests

The authors declare they have no competing interests.