Highlights

-

• Bilinguals shift gaze with audio language: L1 favors eyes, L2 splits time across face.

-

• Dual subtitles override facial cues, directing visual attention primarily to written input.

-

• Top-positioned subtitles receive more viewing time, regardless of language familiarity.

-

• Alignment of spatial and linguistic cues enhances processing efficiency.

1. Introduction

In today’s multimedia learning environments, videos play a pivotal role by integrating speech, text and imagery into a cohesive narrative stream (Brame, Reference Brame2016; Mayer, Reference Mayer and Mayer2014). For non-native speakers, this multimodal format introduces a number of challenges. Unlike native speakers, they must decode unfamiliar orthographic and phonological forms and syntactic patterns while integrating supportive visual and textual cues. This scenario increases demands on working memory and attentional control, raising questions about how they navigate second-language (L2) audiovisual content in real time (Ramezanali & Faez, Reference Ramezanali and Faez2019). The present study addresses these questions through two eye-tracking experiments that examine how viewers engage with audiovisual input presented with or without dual (also known as bilingual) subtitles – that is, the simultaneous presentation of L1 and L2 subtitlesFootnote 1 in the same script, stacked one above the other – and how gaze patterns and comprehension vary depending on language dominance and the spatial positioning of subtitles.

1.1. Theoretical framework

As L2 learners often face increased cognitive demands when engaging with complex audiovisual content (Matthew, Reference Matthew2024; Mayer, Reference Mayer and Mayer2014), insights from foundational models in cognitive psychology can help explain how such input is processed. One of the most influential frameworks, the Dual Coding Theory (Clark & Paivio, Reference Clark and Paivio1991; Paivio, Reference Paivio1986), proposes that verbal and nonverbal information are processed in distinct but interconnected systems. Building on these principles, the Cognitive Theory of Multimedia Learning (Mayer, Reference Mayer and Mayer2014, Reference Mayer2021) emphasizes that effective learning depends on the coherent coordination of visual and verbal inputs. When subtitles are poorly designed, overly detailed or redundant, they create extraneous cognitive load that taxes working memory and disrupts meaningful learning (Mayer & Moreno, Reference Mayer and Moreno2003; Sweller, Reference Sweller, Plass, Moreno and Brünken2010). Reducing this unnecessary burden enables learners to allocate more resources to essential processing. However, when attention is split across competing modalities, comprehension may be affected (Ayres & Sweller, Reference Ayres, Sweller and Mayer2014; Kalyuga & Sweller, Reference Kalyuga, Sweller, Mayer and Fiorella2014; Mayer & Moreno, Reference Mayer and Moreno2003).

This challenge is compounded by the need to regulate cross-linguistic activation in bilingual contexts. As proposed by the Inhibitory Control Model (Green, Reference Green1998), bilinguals must constantly monitor, shift, and suppress one language system to process the other efficiently. This is highly relevant for dual-subtitle processing, where viewers must rapidly shift gaze and selectively attend to one written stream while inhibiting the other, thereby increasing executive control demands.

In the present study, conducted with Spanish-English bilinguals, we treat the vertical placement of L1 and L2 subtitles as a manipulation of visual hierarchy, extending classic accounts of spatial contiguity beyond text–graphic proximity to competition between two written streams in the same script. The top line enjoys habitual reading priority (reflecting top-to-bottom parsing in left-to-right scripts) and therefore carries higher visual salience, potentially reducing search costs under load (Hudson et al., Reference Hudson, Pullen, Lane and Torgesen2009; Rayner, Reference Rayner1998; Rayner et al., Reference Rayner, Pollatsek, Ashby and Clifton2012). Since both Spanish and English follow left-to-right, top-to-bottom reading conventions, the upper line constitutes the natural entry point in either language. This shared convention makes position-based salience independent of linguistic dominance, thereby providing a critical test of whether display layout can compete with, or even override, L1 dominance during dual subtitle processing.

1.2. Subtitles research

While the above-cited models primarily address the integration of verbal (audio) and nonverbal (visual) content, their principles also apply to multimedia presentations involving two distinct written language streams presented alongside audio and visual information (e.g., spoken language accompanied by subtitles; see Mayer & Fiorella, Reference Mayer, Fiorella and Stull2020; Wissmath et al., Reference Wissmath, Weibel and Groner2009). Prior research has shown that L2 subtitles can support lexical segmentation (Mitterer & McQueen, Reference Mitterer and McQueen2009), vocabulary form recognition and acquisition (Montero Perez et al., Reference Montero Perez, Peters and Desmet2018; Peters, Reference Peters2019; Stæhr, Reference Stæhr2009) and overall comprehension (Gass et al., Reference Gass, Winke, Isbell and Ahn2019; Majuddin et al., Reference Majuddin, Siyanova-Chanturia and Boers2021). In this sense, L2 subtitles significantly improve comprehension, attention and memory for video content across all viewer groups, including L2 learners (Gernsbacher, Reference Gernsbacher2015). L2 subtitles in L2 videos, as opposed to no subtitles, have been consistently shown to ease content understanding, particularly for intermediate-level learners (e.g., Rodgers & Webb, Reference Rodgers and Webb2017); L2 subtitles improve comprehension by making the L2 input more salient and ease speech segmentation (Baranowska, Reference Baranowska2025). Furthermore, the print text counteracts the transient nature of spoken language, providing support even for advanced learners (Mayer et al., Reference Mayer, Fiorella and Stull2020).

Nevertheless, the benefits of L2 subtitles are modulated by learner proficiency and task type. The simultaneous processing of multiple modalities (images, audio and text) can overload the working memory of lower-proficiency learners (Hsieh, Reference Hsieh2019; Suárez & Gesa, Reference Suárez and Gesa2019) and may not sufficiently support deeper semantic processing required for meaning recall and inference (Pujadas & Muñoz, Reference Pujadas and Muñoz2024).

In contrast, L1 subtitles foster more immediate semantic access (Pujadas & Muñoz, Reference Pujadas and Muñoz2020), and studies using L1 subtitles in L2 audiovisuals often report higher immediate comprehension scores when participants rely on the L1 subtitles rather than the L2 audio channel (Pujadas & Muñoz, Reference Pujadas and Muñoz2024; Pujadas & Webb, Reference Pujadas and Webb2025). Precisely, L1 subtitles have been found particularly effective in reducing individual differences in working memory capacity and reading ability, reducing the cognitive burden associated with L2 comprehension (Gass et al., Reference Gass, Winke, Isbell and Ahn2019).

However, the primary limitation of L1 subtitles is that they may not directly support L2 speech segmentation or sound-script mapping, which could reduce a learner’s ability to notice L2 word forms (Montero Perez, Reference Montero Perez2020, Reference Montero Perez2022; Teng, Reference Teng2020, Reference Teng2022). This challenge of balancing the immediate comprehension benefit of L1 subtitles with the form-focusing benefit of L2 subtitles has led directly to the study of dual subtitles and sequential viewing strategies.

Dual (or bilingual) subtitles, which display L1 and L2 text simultaneously, are increasingly employed in informal (e.g., language-learning apps, streaming sites) and formal educational and entertainment settings (e.g., countries with two or more official languages, like Belgium, Switzerland, etc., employ dual subtitles when airing films in the cinema). Their increasing use stems from the complementary benefits of L1 subtitles, which provide immediate semantic access, and L2 subtitles, which reinforce form-meaning associations, making them particularly valuable for learners who struggle with L2-only materials (Nguyen et al., Reference Nguyen, Chik, Woodcock and Ehrich2024).

Results from previous research in second language acquisition suggest that dual subtitles enhance vocabulary retention, foster comprehension and encourage incidental language learning through naturalistic exposure to bilingual input (see García, Reference García2017; Wang & Pellicer-Sánchez, Reference Wang and Pellicer-Sánchez2023). For instance, García (Reference García2017) reported that engineering learners perceived dual subtitles as beneficial for developing L2 vocabulary across dimensions of form, meaning and use, whereas Li (Reference Li2016) found that dual subtitles led to superior vocabulary learning among Chinese university students, and this advantage persisted in both immediate and delayed post-tests over monolingual subtitles. In contrast, Lwo and Lin (Reference Lwo and Lin2012) found no overall advantage for dual subtitles in an experiment with Taiwanese eighth graders, suggesting that lower-proficiency learners may rely on selective processing strategies (e.g., drawing on graphics and animations to manage cognitive load and support comprehension) rather than fully engaging with the bilingual text.

Most behavioral studies on dual subtitles have focused on comprehension and vocabulary acquisition in between-subjects designs, typically comparing L1, L2 and dual subtitle conditions in English as a Foreign Language learners, particularly in Chinese (e.g., Chen, Reference Chen2025; Fang et al., Reference Fang, Zhang and Fang2019; Hao et al., Reference Hao, Sheng, Ardasheva and Wang2021; Hu & Deocampo, Reference Hu and Deocampo2024; Li & Hennebry-Leung, Reference Li and Hennebry-Leung2024) and Japanese speakers (Dizon & Thanyawatpokin, Reference Dizon and Thanyawatpokin2021, Reference Dizon and Thanyawatpokin2024). However, these studies relied exclusively on offline measures, failing to capture learners’ moment-to-moment attentional shifts during subtitle processing, an area where online, eye-tracking research remains surprisingly scarce (see Liao et al., Reference Liao, Kruger and Doherty2020; Wang & Pellicer-Sánchez, Reference Wang and Pellicer-Sánchez2023 for exceptions).

Eye-tracking research on dual subtitles has predominantly focused on cross-script pairs, making it difficult to generalize the findings to same-script pairs, such as English and Spanish. Nonetheless, recent work by Liao et al. (Reference Liao, Kruger and Doherty2020) and Wang and Pellicer-Sánchez (Reference Wang and Pellicer-Sánchez2023) on Chinese-English dual subtitles provides a valuable foundation. Liao et al. (Reference Liao, Kruger and Doherty2020) compared various subtitle configurations and found that viewers’ visual attention to Chinese-L1 subtitles was more stable than to English-L2 subtitles and less sensitive to the increased visual competition in the dual (bilingual: L1 + L2) condition, which they attributed to the dominance of the native language. Their results indicated that different dual subtitle configurations did not increase cognitive load relative to monolingual subtitles but were more beneficial than no subtitles for comprehension. Similarly, Wang and Pellicer-Sánchez (Reference Wang and Pellicer-Sánchez2023) showed that dual subtitles were as effective as Chinese-L1 subtitles for overall comprehension, both of which outperformed English-L2-only subtitles and no subtitles. Their eye-tracking data revealed that participants spent significantly more time fixating on the L1 line in the bilingual condition, suggesting that the L1 line attracts greater visual attention. This finding warrants further investigation into the effects of subtitle placement. However, since both studies used the same default configuration (L1 on top, L2 on the bottom), it remains unclear whether the observed attentional patterns were driven by language dominance, by the spatial positioning of subtitles or by an interaction between the two. At the same time, adding a second written stream risks redundancy and split attention (Mayer & Moreno, Reference Mayer and Moreno2003), making the layout of dual subtitles a theoretically and practically consequential choice.

1.3. The present study

To address these gaps, the present study integrates eye-tracking and comprehension measures to investigate the cognitive dynamics of dualsubtitle processing in same-script, sequential, subordinate bilinguals (Spanish as L1 and English as L2). Specifically, our within-participant manipulation of subtitle placement (L2 on top versus L1 on top) directly tests whether visual attention is primarily guided by linguistic dominance or by display layout. This design enables us to test the influence of visual hierarchy on reading behavior. While the Cognitive Load Theory has extensively demonstrated that the strategic placement of written information in proximity to relevant graphics can minimize extraneous load (the spatial contiguity principle), its application to the placement of two competing language streams remains unexplored. We test whether the principle of spatial contiguity extends to dual subtitles, where placing the L1 subtitle in a visually dominant top position can potentially streamline processing by aligning with habitual reading patterns. Furthermore, in line with the Bilingual Language Control Theory (Green, Reference Green1998), we hypothesize that participants will fixate longer on L1 subtitles due to reduced processing effort – note that this preference can interact with the spatial positioning of the subtitles.

Based on the theoretical frameworks and the identified research gaps, the present study addresses the following research questions: (1) How do visual attention and comprehension differ when viewing videos with dual subtitles compared to no subtitles? (2) When dual subtitles are presented, how does the positioning of the L1 and L2 lines (top versus bottom) influence visual attention, specifically the time spent fixating on each line? and (3) To what extent do the language of the audio (L1 versus L2) and the language of the subtitles interact to affect gaze patterns and, subsequently, overall comprehension?

Experiment 1 establishes a baseline by examining gaze patterns with no subtitles, contrasting L1 and L2 audio. We expect viewers to focus primarily on key facial areas—particularly the speaker’s eyes – when processing speech in their L1 (Võ et al., Reference Võ, Smith, Mital and Henderson2012; Wass & Smith, Reference Wass and Smith2014), but to allocate more attention to the speaker’s mouth during L2 input, as they rely more heavily on articulatory cues (Birulés et al., Reference Birulés, Bosch, Brieke, Pons and Lewkowicz2019; Grüter et al., Reference Grüter, Kim, Nishizawa, Wang, Alzahrani, Chang and Yusa2023). In line with these attentional shifts, we expect comprehension to be higher in the L1 audio condition, reflecting lower cognitive load and more efficient speech processing. This baseline serves as a control condition, helping to contextualize the effects of dual subtitles introduced later.

Experiment 2, the critical experiment, investigates participants’ gaze behavior when viewing same-script dual subtitles alongside L1 or L2 audio. Based on both theoretical accounts (the Inhibitory Control Model: Green, Reference Green1998) and previous findings (Liao et al., Reference Liao, Kruger and Doherty2020; Wang & Pellicer-Sánchez, Reference Wang and Pellicer-Sánchez2023), we hypothesize that participants will fixate longer on L1 subtitles when paired with L2 audio, as the L1 text becomes the preferred and most accessible source of semantic information, a strategy that helps manage cognitive load. Conversely, when L1 audio is present, we expect participants to rely less on the subtitles as they understand the audio stream, leading to shorter fixations on the subtitles area as visual attention is freed up to shift toward facial cues (as seen in videos with L1 audio and subtitles: d’Ydewalle & Gielen, Reference d’Ydewalle and Gielen1992; Liao et al., Reference Liao, Yu, Kruger and Reichle2021). The L1 audio becomes the dominant information source, enabling viewers to process the subtitles more superficially and distribute their attention more freely between the text and the video content (Liao et al., Reference Liao, Yu, Kruger and Reichle2021).

However, we also expect this linguistic preference to be influenced by subtitle placement, an issue that previous studies have not addressed. To test this, we manipulate subtitle positioning (L2 on top versus L1 on top) and predict that learners will shift their attention between subtitle streams and facial cues depending on language alignment and spatial layout. For example, when listening to L2 audio, participants may rely more on visual speech cues by directing gaze toward the speaker’s mouth (Birulés et al., Reference Birulés, Bosch, Brieke, Pons and Lewkowicz2019; Grüter et al., Reference Grüter, Kim, Nishizawa, Wang, Alzahrani, Chang and Yusa2023), whereas L1 audio should lessen this reliance. Ultimately, we expect dual subtitles to enhance comprehension, particularly when L1 subtitles occupy the visually dominant top position. These findings will shed light on bilingual processing and carry implications for second-language education, media design, and accessibility.

2. General method

Experiments 1 and 2 were conducted within the same session, allowing participants to complete both procedures sequentially while maintaining consistency in set-up and conditions. Therefore, each participant viewed each video exactly once, with the six videos assigned to the six conditions (two in Experiment 1, four in Experiment 2) in a Latin-square counterbalanced manner.

2.1. Participants

A total of 42 native Spanish speakers (14 men), aged 18–31 years (M = 22.4, SD = 2.7), from the University of Valencia (Spain) participated in the experiments. All had normal or corrected-to-normal vision and reported no language-related disorders. All participants were sequential subordinate bilinguals, as defined by psycholinguistic theories that emphasize the functional use of two languages (Abutalebi & Weekes, Reference Abutalebi and Weekes2014; Del Maschio et al., Reference Del Maschio, Bellini, Abutalebi and Sulpizio2025). They had studied English as a foreign language since primary school, with at least 10 years of formal instruction. Participants’ English proficiency was assessed as intermediate-to-advanced (B1 to C2) based on their latest language certificates, aligned with the Common European Framework of Reference for Languages (Council of Europe, 2001, 2020).

To ensure adequate power for detecting the critical interactions (Experiment 1: Area of Interest × Audio Language [2 × 2]; Experiment 2: Subtitle Position × Audio Language [2 × 2] and Area of Interest × Audio Language [4 × 2]), we conducted a priori power analysis using G*Power (Faul et al., Reference Faul, Erdfelder, Lang and Buchner2007) for a 2 × 2 within-subjects repeated-measures ANOVA. Assuming a medium effect size (f = .25, η2 = .06), an alpha level of .05, and a correlation of 0.5 between repeated measures, the required sample size was 34 participants. Note that this estimate is conservative for the 4 × 2 within-subjects interaction in Experiment 2: the required sample size for this interaction was 24 participants. Thus, with 42 participants, our sample exceeds this threshold, providing sufficient power to detect all the critical interactions even if the true effect size is slightly smaller than anticipated.

Participants provided informed consent and received a small amount of monetary compensation upon completion. All procedures complied with the ethical standards of the Ethics Committee of the University of Valencia and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2008.

2.2. Materials

The experiment utilized a set of six short, self-contained educational videos on diverse geographical and cultural topics. Each video had a consistent duration of approximately 2 minutes and 20 seconds. These videos were designed to require no previous knowledge, as all necessary information was provided within the segment, and covered geographically diverse locations: Belize, Comoros, Djibouti, Kyrgyzstan, Lesotho and Tonga. The six locations were chosen to minimize prior knowledge among a Spanish-based sample and to ensure broad geographic diversity (Central America, East Africa, Central Asia and the South Pacific). We selected five interesting facts about each place, the location and an initial question that captured individuals’ curiosity.

The videos featured two AI-generated, human-like avatars rather than real actors to maintain experimental control and minimize variability in speech characteristics, tone, lip movements and gaze behavior. Both avatars were female, aged 30–40 years, professionally dressed, ensuring uniformity across video content. The avatars were generated using Synthesia® (2023), a tool that allows consistent stimulus similarity. Each avatar took turns speaking while the other remained visible, enabling natural gaze shifts between them. Each avatar spoke in a consistent voice across videos (English: U.S. accent; Spanish: Castilian accent). Figure 1 illustrates the screen distribution for the no-subtitles condition of Experiment 1, and Figure 2 illustrates the screen distribution for Experiment 2.

Figure 1. Representation of the distribution on screen for the no-subtitles condition.

Figure 2. Representation of the distribution on screen for the dual-subtitles condition.

For Experiment 2, subtitles were created in Adobe Premiere Pro® (2024) in accordance with standard subtitling guidelines (Díaz-Cintas, Reference Díaz-Cintas2019; Díaz-Cintas & Anderman, Reference Díaz-Cintas and Anderman2009; Díaz-Cintas & Orero, Reference Díaz-Cintas, Orero, Gambier and van Doorslaer2010). A professional audiovisual translator reviewed all subtitle versions for quality control. Subtitles were displayed in Roboto Regular, 45-point, with a black shadow and yellow (upper-line subtitles) or white (lower-line subtitles). They were synchronized with audio, stacked in the lower third of the screen, and limited to 42 characters per line for readability. The average speed for the subtitles was 165.64 words per minute (WPM range: 156.23–180.89, SD = 7.16), ensuring a natural and consistent pace. Appendix A presents Table A1, which contains, for each subtitle and video, the WPM, number of words, and time in seconds.

Comprehension was assessed using a true/false test for consistency across videos. The test included 60 statements, with 10 questions per video (1 point per correct answer). To minimize extraneous cognitive load during the test itself and ensure that comprehension scores reflected the video content rather than reading ability, the test was presented in a bilingual format (e.g., Belice es un paraíso de los buceadores/Belize is a scuba diving paradise). The questions were equated for difficulty by basing them on idea units, using the same vocabulary employed on the videos, and by having answers directly related to the content. The materials can be accessed through OSF (https://osf.io/4ngst/?view_only=1051d038ae88471c92292b6d16eed79f), to ensure transparency and reproducibility. Additional video files are available on request from the authors.

2.3. Apparatus

The experiment was implemented using Experiment Builder (SR Research Ltd, Canada) on a Windows 11 computer connected to an EyeLink® 1000 Plus eye-tracker (SR Research Ltd, Canada), with a sampling rate of 1000 Hz. It was presented on a 24″ Asus VG248 LCD monitor (144 Hz, resolution 1280 × 1024). Participants wore a high-definition headset (Hercules HDP DJ60) to standardize audio quality. EyeLink® Data Viewer (SR Research Ltd, Canada) was used to process the recorded data.

2.4. Procedure

Experiment 1 (no-subtitles) and Experiment 2 (dual-subtitles) were conducted in the same session. After participants had signed the consent form, the experiment was conducted in a quiet laboratory room. They were encouraged to ask questions if they did not understand any aspect of the procedure before proceeding.

Participants were seated at a Windows 11 computer connected to a video-based eye-tracker, and audio was delivered at a comfortable listening level. Before starting, written instructions appeared on the computer screen, guiding participants through the procedure. They were seated 60 cm from the monitor, using a chin-and-forehead mount to minimize movement. The experiment included a 9-point calibration phase with validation, ensuring accurate tracking of eye movements. Data were collected from the participant’s right eye, and calibration was accepted when the average error was <0.5°.

To quantify gaze behavior, we created areas of interest (AOI) around the eyes, the mouth and the subtitles. Through Data Viewer, we transformed the data into area-of-interest reports with the following variables: dwell time, or the time spent in each area of interest (in seconds), and total trial dwell time.

Participants first watched a 30-second instructional video, followed by a practice video with the same format as the first trial video. Each of the six videos was presented under different subtitles/audio conditions, counterbalanced across participants in a Latin-square design. The L1-audio and L2-audio blocks were counterbalanced across participants (half L1 → L2; half L2 → L1) with a 5-minute break between blocks. After each video, participants answered comprehension questions on a Microsoft Surface Go 10+, ensuring consistency in response collection.

2.5. Data analysis preparation

To examine visual attention allocation, we computed cumulative dwell time (in seconds) for each AOI under two conditions for Experiment 1: L2 original audio and L1 original audio; and four conditions for Experiment 2: L2 audio with dual subtitles with L1 on top, L2 audio with dual subtitles with L2 on top, L1 audio with dual subtitles with L1 on top and L1 audio with dual subtitles with L2 on top.

We computed dwell time for the eyes and mouth of both avatars. In addition, two AOIs were defined for the subtitle lines (L1 and L2). Each AOI corresponded to the bounding box of the text line on screen and was updated frame by frame according to subtitle onset and offset times. Because subtitles were always presented as two stacked lines, we defined two non-overlapping rectangular AOIs – one for the upper line and one for the lower line – covering only the subtitle text. The total dwell time for each AOI (eyes, mouth, L1 subtitles and L2 subtitles) was then normalized relative to total trial duration, yielding relative dwell times (AOI dwell time/total trial duration). As an alternative metric, proportional dwell time could also be calculated relative to the total on-screen duration of the subtitles – note that this approach yields essentially the same pattern of results as using total trial duration, which we adopt here. For analyses involving the four-level Area of Interest factor in Experiment 2, we applied the Greenhouse–Geisser correction to the degrees of freedom. For comprehension, each participant’s accuracy score (number of correct responses for the video in that condition) was calculated and analyzed using repeated-measures ANOVAs, separately from the gaze measures.

The data processing and statistical analysis described above – which is consistent with methods used in prior studies of bilingual eye-tracking (Barenholtz et al., Reference Barenholtz, Mavica and Lewkowicz2016; Birulés et al., Reference Birulés, Bosch, Brieke, Pons and Lewkowicz2019; Lusk & Mitchel, Reference Lusk and Mitchel2016) – were conducted using JASP (version 0.19.3.0) (Wagenmakers et al., Reference Wagenmakers, Love, Marsman, Jamil, A., Verhagen and Meerhoff2018).

3. Experiment 1

3.1. Results

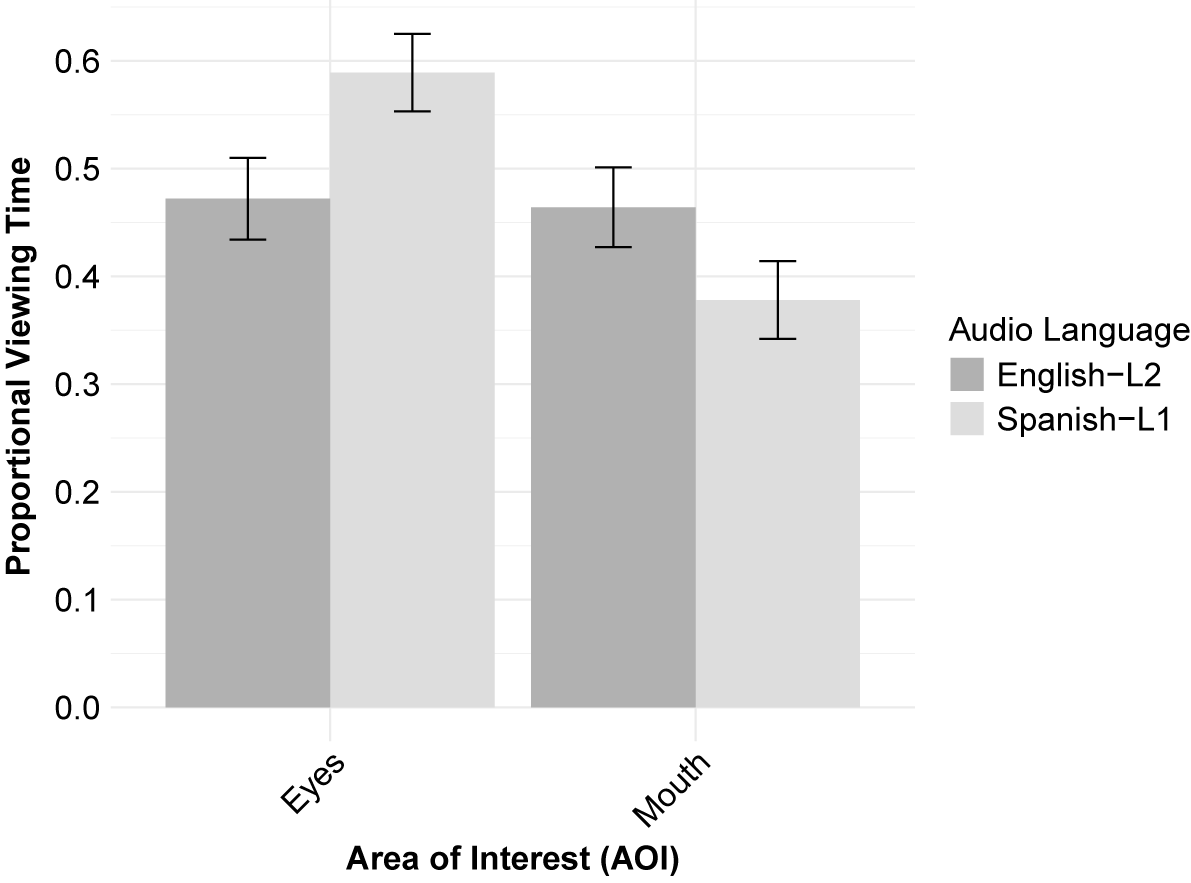

We first report the results of the gaze behavior analysis, followed by the comprehension scores. We assessed whether the audio language (L1 versus L2) influenced participants’ gaze allocation to the speaker’s eyes and mouth. To investigate this, we conducted a 2 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA, with Area of Interest (eyes versus mouth) and Audio Language (L1 versus L2) as within-subjects factors on the mean proportional AOI dwell times. Figure 3 shows the mean proportional dwell time for each AOI across both languages.

Figure 3. Proportional dwell time for eyes and mouth in the L1 and L2 audio versions. The bars represent the standard error of the mean.

While neither the language of the audio (L1 versus L2) nor the AOI (eyes versus mouth) dwell time yielded significant main effects ([F(1, 41) = 1.65, p = .206, ηₚ2 = .04], and [F(1, 41) = 2.44, p = .126, ηₚ2 = .06], respectively), we found a significant interaction between the two factors [F(1, 41) = 34.66, p < .001, ηₚ2 = .46]. Simple effect analyses revealed that, under L1 audio, participants looked longer at the eyes than the mouth, F(1, 41) = 8.57, p = .006; under L2 audio, the two regions did not differ, F(1, 41) = .01, p = .916. Thus, the pattern of gaze allocation to the eyes and mouth differed substantially across audio languages.

In terms of comprehension, scores were significantly higher for L1 audio than for L2 audio, t(41) = −2.20, p = .033, d = .34. This small but significant difference confirms that L2 audio imposed a measurable processing demand. Table 1 shows the means and standard errors for each AOI and for the comprehension results.

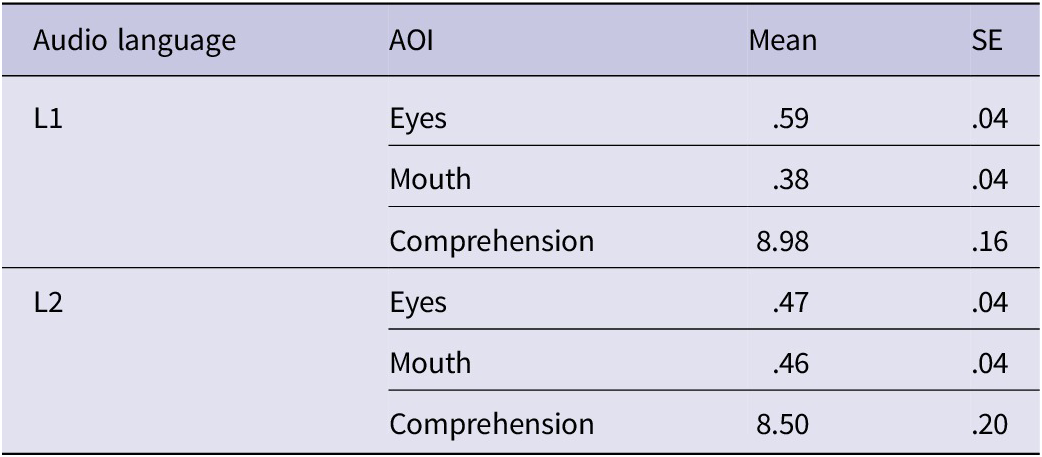

Table 1. Descriptive statistics for Experiment 1. Relative dwell time (proportion of trial duration) is shown for each area of interest (AOI), and comprehension scores are reported as mean test scores. Values are means (M) with standard errors (SE)

3.2. Discussion

The present experiment demonstrated that participants’ visual attention to a speaker’s face differed significantly depending on whether the auditory input was in their L1 or L2. The finding that gaze was more focused on the speaker’s eyes in the L1 video is consistent with previous research on naturalistic conversation, where direct eye contact is a key social cue (Võ et al., Reference Võ, Smith, Mital and Henderson2012; Wass & Smith, Reference Wass and Smith2014). This suggests that during low load, L1 processing, attention is primarily allocated to socially informative regions of the face.

In contrast, when listening to English (L2), participants’ gaze was more evenly distributed between the eyes and the mouth. This shift in gaze allocation likely serves as a compensatory strategy to support speech decoding under higher cognitive load. Attending to the mouth provides crucial phonetic information (e.g., lip movements) that can aid in the recognition of unfamiliar sounds and words, a process particularly relevant for L2 listening comprehension. This interpretation is consistent with previous findings in single-speaker contexts (Birulés et al., Reference Birulés, Bosch, Brieke, Pons and Lewkowicz2019; Grüter et al., Reference Grüter, Kim, Nishizawa, Wang, Alzahrani, Chang and Yusa2023), and our results extend this pattern to a multi-speaker, instructional video format.

In terms of comprehension, in line with our baseline hypothesis, participants performed better in their L1 than in their L2, indicating that L2 listening is more demanding. This finding aligns with previous research showing that L2 listening, even among advanced learners, increases cognitive load and reduces processing efficiency (e.g., Mayer, Reference Ayres, Sweller and Mayer2014). While the numerical difference was small, this outcome is considered a positive indication of participant engagement and the effectiveness of their underlying cognitive strategies. The comprehension test was designed to confirm that participants maintained sufficient attention to the video content across all conditions, and the high overall scores (means of 8.98 and 8.50 out of 10) confirm this.

4. Experiment 2

Building on the findings from Experiment 1, which revealed distinct gaze patterns during L1 and L2 listening, the present experiment examines how viewers engage with dual subtitles. Specifically, we test how subtitle positioning (L1 on top versus L2 on top) influences the distribution of visual attention between the speaker’s face and the subtitles and how these patterns vary with the audio language.

4.1. Results

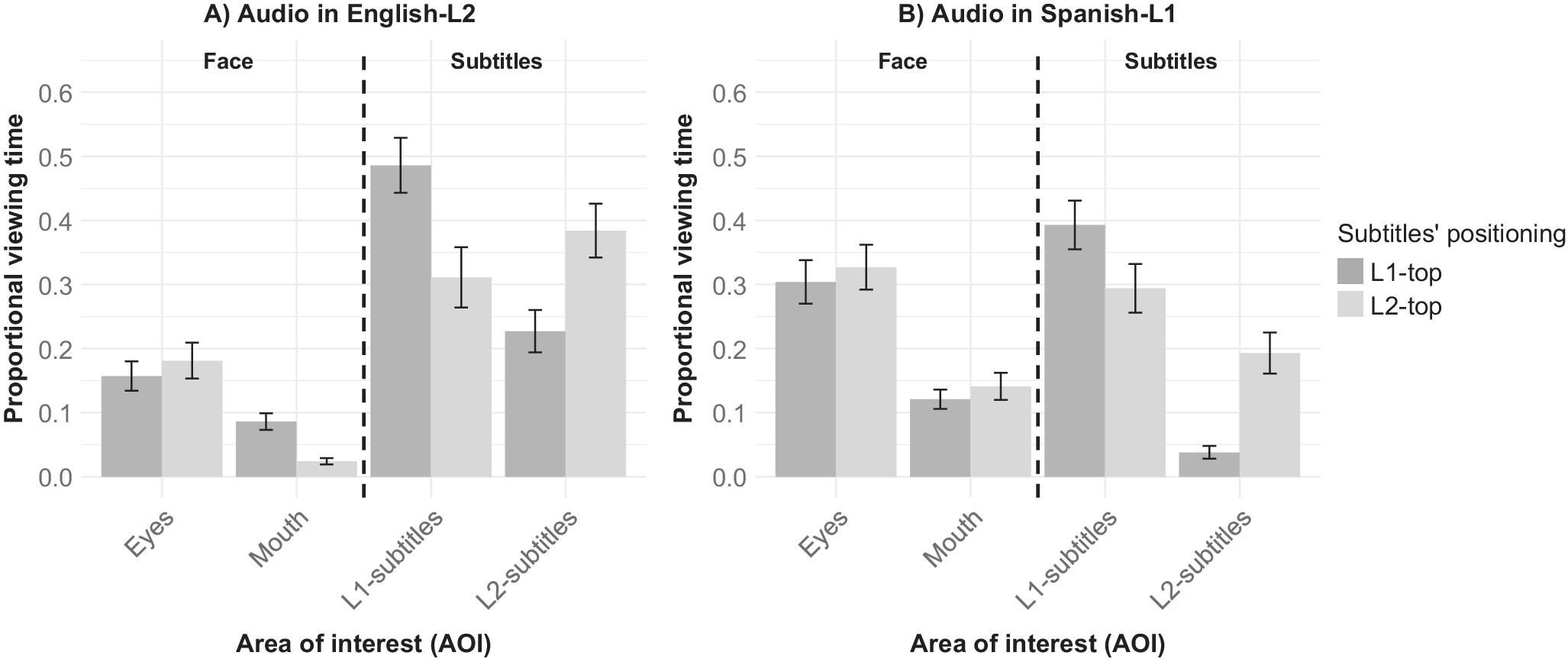

We first report the results of the gaze behavior analysis, followed by the comprehension scores. We examined whether the spatial positioning of the subtitles – placing English above Spanish or Spanish above English – influenced participants’ visual attention to the speaker’s eyes, mouth and subtitles, as a function of the audio language (Spanish–L1 versus English–L2). To this end, a 4 × 2 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA was conducted on mean proportional dwell times, with AOI (eyes, mouth, L2 subtitles, L1 subtitles), audio language (L1 versus L2), and subtitle position (L2-top versus L1-top) as within-subjects factors. The mean relative dwell times for each condition are presented in Figure 4.

Figure 4. Proportional dwell time for eyes, mouth, and subtitles (L2 vs L1), considering the position of subtitles (top versus bottom) in the L2 and L1 audio videos. The bars represent the standard error of the mean.

Results showed no main effects for audio language (F(1, 41) = 1.98, p = .167, ηp2 = .046) or subtitle positioning (F(1, 41) = 2.18, p = .147, ηp2 = .05). In contrast, participants’ gaze patterns varied across AOIs, F(2.05, 84.06) = 18.27, p < .001, ηp2 = .31. The three-way interaction did not approach significance, F(2.28, 93.63) = 1.41, p = .250, ηp2 = .03. Table 2 presents the means and standard errors for each Area of Interest (AOI) according to the four specific within-subjects conditions (2 Audio Languages × 2 Subtitle Positions), allowing direct comparison of fixation times and comprehension across the full experimental design.

Table 2. Descriptive statistics for Experiment 2: Mean relative dwell time (proportion of trial duration) and comprehension scores are reported for the four within-subjects conditions (2 Audio Languages × 2 Subtitle Positions: L1-Top/L2-Bottom versus L2-Top/L1-Bottom). Values are means (M) with standard errors (SE)

In addition, three significant two-way interactions emerged. First, the interaction between audio language and AOI was significant, F(2.32, 95.03) = 17.12, p < .001, ηp2 = .29. A Holm–Bonferroni post-hoc analysis revealed that participants’ gaze patterns to the face and subtitles differed based on the audio language. While participants consistently spent more time looking at the speaker’s eyes than on the speaker’s mouth across both languages (t(41) = 5.11, p < .001), they preferentially attended to the subtitles that matched the spoken language. With L2 audio, participants looked longer at L2-subtitles (M = .38) than at L1-subtitles (M = .23), t(41) = −5.14, p < .001, d = −0.94. With L1 audio, the reverse was true; participants focused more on L1-subtitles (M = .39) than on L2-subtitles (M = .29), t(41) = 5.35, p < .001, d = 1.13.

Second, the interaction between Audio Language and Subtitle position was also significant (F(1, 41) = 26.74, p < .001, ηp2 = .39). This finding indicates that the vertical spatial positioning of the subtitles significantly modulated attention. Holm–Bonferroni post hoc comparisons revealed a strong preference for the top-line subtitle, regardless of language. In L2 audio, participants looked longer at the subtitles on the top line (M = .384) than on the bottom line (M = .227), t(41) = 4.21, p < .001, d = .07. A similar pattern emerged for L1 audio, participants looked more at the top line (M = .39) than the bottom line (M = .29), t(41) = 3.74, p = .002, d = .12.

Finally, the interaction between AOI and subtitle position was significant, F(2.37, 97.02) = 29.55, p < .001, ηp2 = .419. Gaze distribution varied depending on the vertical placement of the subtitles. Across both subtitle configurations, participants consistently looked more at the speaker’s eyes than the mouth (e.g., Eyes versus Mouth in L2-top: t(41) = 5.59, p < .001, d = .85). Additionally, a clear pattern emerged: participants’ gaze was overwhelmingly directed to the top subtitle line, regardless of language, compared to the bottom line (Mtop = .39 versus Mbottom = .18). This preference was strongest when the L1 subtitles appeared at the top (ML1 − top = .39 versus ML2 − bottom = .04), t(41) = 6.32, p < .001, d = 1.53.

Finally, to analyze the role of subtitle positioning and audio language on comprehension, we conducted a 2 × 2 repeated-measures ANOVA on comprehension scores, with Audio Language (L1 versus L2) and Subtitle Position (L1-top versus L2-top) as within-subjects factors (see Table 2 for the descriptive statistics). Results showed significantly higher comprehension with L1-top subtitles than with L2-top subtitles (F(1, 41) = 7.44, p = .009, ηp2 = .15). In addition, we found no main effect of audio language (F(1, 41) = 1.41, p = .242, ηp2 = .03) and no interaction between audio language and subtitle position (F(1, 41) = .71, p = .405, ηp2 = .02).

For completeness, we also conducted a supplementary analysis comparing comprehension scores from the subtitled conditions in Experiment 2 to the non-subtitled conditions in Experiment 1. For L2 videos, participants showed significantly higher comprehension with subtitles (M = 8.92) compared to without subtitles (M = 8.50; t(41) = −2.14, p = .039). In contrast, for L1 videos, comprehension remained unchanged whether subtitles were present or not (M = 9.10 versus M = 8.98; t(41) = −0.55, p = .582). These findings highlight subtitles as a valuable aid for L2 learners, with little effect on L1 comprehension.

4.2. Discussion

This experiment examined how dual subtitles and their spatial positioning shape visual attention and comprehension. Extending Experiment 1, which revealed a natural gaze shift toward the speaker’s mouth during L2 listening, the results show that the introduction of subtitles fundamentally reshapes this allocation strategy. Consistent with our hypotheses, subtitles strongly captured attention, often at the expense of facial features, reflecting the competition between written and visual speech cues when foreign-language processing increases cognitive load. This effect aligns with the Inhibitory Control Model (Green, Reference Green1998), which predicts reduced effort for the L1, but the robust top-line advantage further demonstrates that layout can rival, and in some cases, outweigh, linguistic dominance. Subtitle position influenced both gaze and comprehension: participants consistently prioritized the upper line, and comprehension was higher when L1 subtitles appeared on top and L2 subtitles below. Subtitles also increased comprehension in the L2 audio condition relative to no subtitles, while offering no benefit in L1, where performance was already near ceiling, underlining their compensatory role under greater processing load. Taken together, these findings refine previous accounts by showing that not only the presence but also the placement and language of subtitles measurably shape both attention and comprehension. In conclusion, spatial positioning exerts a powerful influence, with an advantage for L1-top subtitles.

5. General discussion

The present experiments investigated how audio language and subtitle configuration jointly shape gaze behavior and comprehension in bilinguals viewing instructional videos. To our knowledge, this is the first eye-tracking study on same-script dual subtitles that systematically manipulates vertical placement, thereby isolating spatial-layout effects from linguistic dominance (cf. Liao et al., Reference Liao, Kruger and Doherty2020; Wang & Pellicer-Sánchez, Reference Wang and Pellicer-Sánchez2023). Beyond bilingual processing, the findings inform multimedia learning by showing how written input modulates audiovisual comprehension, offering practical guidance for instructional design.

Experiment 1 showed that audio language modulates visual attention. When watching videos in their native language (L1: Spanish), participants focused more on the speaker’s eyes, supporting the view that L1 processing facilitates attention to socially meaningful cues (Võ et al., Reference Võ, Smith, Mital and Henderson2012; Wass & Smith, Reference Wass and Smith2014). In contrast, L2 (English) input led to a more balanced distribution of gaze between the eyes and the mouth, consistent with greater reliance on articulatory cues during non-native speech decoding (Birulés et al., Reference Birulés, Bosch, Brieke, Pons and Lewkowicz2019; Grüter et al., Reference Grüter, Kim, Nishizawa, Wang, Alzahrani, Chang and Yusa2023). Comprehension outcomes mirrored these attentional shifts, reinforcing the view that L1 processing affords more efficient access to meaning.

Experiment 2 introduced dual subtitles and manipulated their vertical placement. This led to marked changes in gaze behavior: subtitles redirected attention away from the speaker’s face, especially the mouth, confirming the dominance of written input under higher cognitive load (Liao et al., Reference Liao, Kruger and Doherty2020; Montero Perez et al., Reference Montero Perez, Peters and Desmet2018; Wang & Pellicer-Sánchez, Reference Wang and Pellicer-Sánchez2023). Participants consistently prioritized the top subtitle line, regardless of the language it displayed, likely reflecting habitual reading direction. Although L1 subtitles attracted more dwell time overall, vertical position had a stronger effect than language familiarity, reinforcing the role of visual salience in shaping attention (see Rayner, Reference Rayner1998). This robust top-line advantage partially contrasts with the language dominance finding reported by Wang and Pellicer-Sánchez (Reference Wang and Pellicer-Sánchez2023), where L1 subtitles were always presented on the top line, suggesting that in same-script contexts visual salience (position) may be a stronger determinant of immediate attention than language familiarity. From a multimedia-learning perspective, introducing a second written stream can induce redundancy and split attention unless layout effectively signals where to look (see Mayer & Moreno, Reference Mayer and Moreno2003). The strong pull toward the upper subtitle line suggests that layout conventions can serve as signaling cues in dual subtitle displays, directing attention and easing cognitive load. Moreover, we conducted an exploratory analysis to examine whether the initial fixation on the top subtitle line was followed by a shift to the bottom line, depending on which language occupied that line. When the bottom line was in L1, viewers typically moved down after the initial top-line fixation; when the bottom line was in L2, this top-to-bottom shift was much less frequent. In short, the top line attracts the first fixation, whereas language (in particular, L1) guides subsequent fixation locations. Further research should examine this pattern in additional experimentsFootnote 2.

Crucially, a comparison of both experiments reveals a clear functional shift. In the absence of subtitles, auditory language guides gaze differently depending on familiarity: toward the eyes in L1, and more evenly across facial features in L2. With subtitles, however, written input dominates and neutralizes L1–L2 differences. Thus, subtitles function as an attentional equalizer, overriding natural face-directed strategies and redirecting gaze toward visually anchored linguistic input.

These findings align with multimedia learning frameworks that emphasize modality integration and cognitive load management (Mayer, Reference Mayer and Mayer2014, Reference Mayer2021; Sweller, Reference Sweller, Plass, Moreno and Brünken2010). They also support the Dual Coding Theory (Paivio, Reference Paivio1986), which illustrates how auditory and written input facilitate comprehension through parallel processing channels. However, this benefit hinges on attentional economy; excessive competition between modalities can overload the system. Our eye movement and comprehension data indicate that bilingual viewers mitigate this risk by selectively prioritizing the more accessible subtitle line, typically the one in their native language (L1), and placing it in the upper position. This strategy directly optimizes cognitive efficiency and enhances comprehension, in line with bilingual language control theories (Green, Reference Green1998). The overall high comprehension scores observed across all conditions (including the L2 conditions of Experiment 1, despite higher cognitive load) provide evidence that viewers successfully deployed these cognitive and visual strategies to achieve strong learning outcomes.

From an applied standpoint, our findings highlight the need to tailor subtitle formats to learners’ attentional tendencies, cognitive load and pedagogical goals. In instructional design, placing L1 subtitles at the top line is not just a visual preference; our results demonstrate that it also improves comprehension compared to placing L2 subtitles at the top (p = .009). Although the benefits of L1 subtitles are well established, our novel finding is that the vertical layout itself serves as a powerful attentional signaling cue: the top line captures processing priority and yields a reliable gain for whichever language occupies it. This provides novel evidence for the utility of spatial layout as a signaling cue in dual subtitle learning. Still, the most effective configuration may depend on the learning objective, whether the goal is comprehension, form-meaning mapping or vocabulary acquisition. Notably, viewers tend to focus on the more cognitively accessible stream, meaning that subtitle format – not just presence – shapes how bilinguals engage with audiovisual content. These principles extend beyond education: optimizing subtitle layout could improve accessibility for hearing-impaired viewers, support multilingual media use and enhance content delivery across global platforms.

Some limitations should be acknowledged. Participants were exclusively university-level Spanish–English bilinguals with intermediate-to-advanced proficiency in English. Future research should explore how these effects generalize to other age groups, language pairs, and proficiency levels. Additionally, while eye-tracking captures fine-grained attentional dynamics, it cannot measure higher-order cognitive variables (e.g., working memory, attentional control) that are likely to interact with gaze behavior. Examining these interactions and the role of additional visual elements (e.g., illustrations or animations) could yield deeper insights into multimodal learning. Furthermore, future studies could conduct more detailed analyses of reading patterns within subtitles by examining other measures, such as word skipping, saccade length, regression rates and word-frequency effects, to provide a finer-grained account of subtitle processing depth. Given that our materials consisted of relatively short instructional clips, future work should investigate whether these patterns persist in more naturalistic viewing contexts (e.g., longer-form videos, entertainment media). In addition, because our design included only one video per condition, we relied on repeated-measures ANOVAs; future research with more stimulus items could employ mixed-effects models to better capture random effects of participants and materials. Finally, comprehension scores were consistently high across conditions with dual subtitles, reflecting our decision to use relatively accessible L2 videos that resemble everyday viewing situations. However, this ceiling effect may have limited our ability to detect subtle differences in comprehension between subtitle configurations. A targeted follow-up study could assess the durability of the observed top-line advantage, use difficulty-calibrated materials and include measures of delayed recall and recognition at 24–48 hours, along with transfer and confidence metrics. These would allow us to determine whether the initial performance gains translate into longer-term memory benefits and to clarify the relationship between eye-tracking indices and enduring learning outcomes.

To conclude, the present experiments offer new evidence on how bilingual viewers process instructional video content, modulating their attention in response to language familiarity, subtitle placement and cognitive load. These findings speak to bilingual language processing and multimedia learning models, showing how the interaction of modality, structure and linguistic context shapes visual attention. At the same time, they offer practical guidance: optimizing subtitle placement is not just an issue of visual design; it directly affects how viewers attend to and comprehend information. As multimodal learning environments expand, adaptive subtitle systems (e.g., customizable positioning or real-time synchronization) may help align media design with the cognitive demands of diverse learner populations.

Data availability statement

The data, scripts and output files are available at the following OSF link: https://osf.io/4ngst/?view_only=1051d038ae88471c92292b6d16eed79f

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank all participants in this study and the reviewers for their time and comments.

Funding statement

This work was partially supported by grants of the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation PID2024-161331NB-I00 (MCIN/AEI/10.13039/501100011033) (Jon Andoni Duñabeitia) and PID2023-152078NB-I00 (Manuel Perea) and by grant CIAICO/2024/198 from the Valencian Government (Manuel Perea).

Competing interests

The authors reported no potential conflict of interest.

Ethics approval statement

The authors state that they do not have any known competing financial interests or personal ties that may have influenced the work disclosed in this study. All procedures were carried out in conformity with the Helsinki Declaration’s ethical norms. The study received ethical approval from the Ethics Committee of the Universitat de València (Valencia, Spain). All participants in this study were required to provide informed consent.

Appendix A

Table A1. Subtitle file characteristics by language and video: total words, duration (s), and words per minute (WPM; computed as total words ÷ duration in minutes). VO = original L1 video; OV = original L2 video; EN/ES = subtitle language (English/Spanish). The names of the video files correspond to the materials in OSF