1. Introduction

Stellarators offer a promising path to realising controlled thermonuclear fusion as steady-state magnetic plasma confinement schemes (Boozer Reference Boozer2021). Their benefits arise from the freedom in the three-dimensional shaping of the magnetic field, away from the constraining requirement of axisymmetry (Wesson & Campbell Reference Wesson and Campbell2011), which is at the heart of the tokamak concept. However, this increase in the complexity of the magnetic field shaping and the loss of symmetry require careful tailoring, in particular, to prevent prompt collisionless losses of particles. The latter is commonly achieved through numerical optimisation, by seeking properties such as quasisymmetry (Boozer Reference Boozer1983; Nührenberg & Zille Reference Nührenberg and Zille1988; Rodriguez et al. Reference Rodriguez, Helander and Bhattacharjee2020) or, more generally, omnigeneity (Hall & McNamara Reference Hall and McNamara1975; Bernardin, Moses & Tataronis Reference Bernardin, Moses and Tataronis1986; Cary & Shasharina Reference Cary and Shasharina1997; Landreman & Catto Reference Landreman and Catto2012; Dudt et al. Reference Dudt, Goodman, Conlin, Panici and Kolemen2024), alongside other additional requirements (aspect ratio, magnetohydrodynamic (MHD) stability, coil complexity, etc.). The problem of finding stellarator designs is therefore a multi-objective optimisation problem in a high-dimensional optimisation space, with multiple minima and in which evaluation of each point (i.e. computation of three-dimensional isotropic pressure, ideal magnetohydrostatic (MHS) equilibrium) is time consuming. While this method has been successfully applied to produce attractive stellarator designs (Nührenberg & Zille Reference Nührenberg and Zille1988; Anderson et al. Reference Anderson, Almagri, Anderson, Matthews, Talmadge and Shohet1995; Zarnstorff et al. Reference Zarnstorff2001; Ku & Boozer Reference Ku and Boozer2010; Landreman & Paul Reference Landreman and Paul2022), it is a daunting (if not impossible) task to conduct an exhaustive solution space scan (Landreman Reference Landreman2019; Giuliani, Rodríguez & Spivak Reference Giuliani, Rodríguez and Spivak2024).

To alleviate some of this burden, and gain additional insight into what that vast space of stellarators may look like, analytic insight can be gained through the near-axis expansion (NAE) (Mercier Reference Mercier1964; Solov’ev & Shafranov Reference Solov’ev and Shafranov1970; Lortz & Nührenberg Reference Lortz and Nührenberg1976; Garren & Boozer Reference Garren and Boozer1991b ; Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Plunk and Jorge2025). This is an asymptotic description of the field in the distance from its centre (the magnetic axis), which constitutes a simple consistent model of stellarator fields. This approach has the benefit of reducing the MHS equilibrium problem, alongside omnigeneity conditions, to a reduced set of parameters and functions (Garren & Boozer Reference Garren and Boozer1991a ; Landreman, Sengupta & Plunk Reference Landreman, Sengupta and Plunk2019; Plunk et al. Reference Plunk, Landreman and Helander2019; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Plunk and Jorge2025) related through algebraic and ordinary differential equations that may be numerically solved orders of magnitude faster than their global counterparts (Landreman et al. Reference Landreman, Sengupta and Plunk2019; Panici et al. Reference Panici, Conlin, Dudt, Unalmis and Kolemen2023). This has enabled more exhaustive exploration of the space of stellarators (Landreman Reference Landreman2022a; Rodriguez, Sengupta & Bhattacharjee Reference Rodriguez, Sengupta and Bhattacharjee2023; Giuliani et al. Reference Giuliani, Rodríguez and Spivak2024). Besides this practical difference, NAE theory has also been shown to be a natural lens through which to understand the space of optimised stellarators, particularly quasisymmetric ones (Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Sengupta and Bhattacharjee2022b , Reference Rodriguez, Sengupta and Bhattacharjee2023).

The NAE theory offers a sensible path to searching for candidate stellarator configurations with desirable confinement properties. However, the theory is still fundamentally an asymptotic theory: the solutions it finds are only valid in some volume near the axis. The further away, the less reliable the description becomes, and thus global MHS solutions are still required to fully characterise the stellarator equilibrium. It is natural, however, to employ the near-axis construction as a starting point for higher-fidelity field construction, and thus it is necessary to devise a way of connecting global equilibrium solutions to the near-axis ones. The current standard method evaluates the NAE field at a finite distance from the axis, constructs the corresponding flux surface and uses it as an input to conventional nested flux surface global (fixed-boundary) MHS codes (Hirshman & Whitson Reference Hirshman and Whitson1983; Dudt et al. Reference Dudt, Conlin, Panici, Unalmis, Kim and Kolemen2022; Hindenlang, Plunk & Maj Reference Hindenlang, Plunk and Maj2025). Although this procedure has proved effective, there is a blatant fault to it: the NAE is being used to inform the global solution at a point where it is least valid (far from the axis). The result is that many of the features curated into the NAE fields are lost when building the equilibria, especially at lower aspect ratios.

This paper introduces a new method of finding global three-dimensional (3-D) MHS equilibrium solutions, in the equilibrium solver DESC, which are intimately connected to NAE theory. We do so by constraining the global solution’s near-axis behaviour directly, using information from the NAE where it is most valid. This way of connecting the asymptotic behaviour to global equilibrium will preserve any near-axis property studied, understood or optimised for within the near-axis framework. While we do so, we leave freedom to the global MHS solver to mould the solution far from the axis, where the NAE loses accuracy. This results in global MHS solutions with near-axis behaviour consistent with the NAE, and far-from-axis behaviour consistent with solving the global MHS equilibrium equations.

The paper is organised as follows. Section 2 presents both formulations of the equilibrium problem as they are done in the NAE and DESC, in order to link them to each other. Section 3 will then use this connection to derive, order by order up to second order in the distance from the axis, the geometric constraints on the DESC equilibrium which enforce the NAE behaviour. Section 4.1 then presents some examples of the constrained equilibria, which are also used to verify the correct enforcement of the NAE behaviour in the global equilibrium.

2. Connecting the near-axis description

The goal of the paper is simple: we aim to construct global equilibria given some prescribed near-axis behaviour. To do so, we first need to understand how to deal with the equilibrium problem.

2.1. The equilibrium problem

We define an equilibrium solution as a magnetic field with nested flux surfaces that satisfies the MHS equilibrium equation

![]() $\boldsymbol{j}\times \boldsymbol{B}=\boldsymbol{\nabla }p$

, where

$\boldsymbol{j}\times \boldsymbol{B}=\boldsymbol{\nabla }p$

, where

![]() $\boldsymbol{j}=\mu _0^{-1}\boldsymbol{\nabla }\times \boldsymbol{B}$

is the plasma current density,

$\boldsymbol{j}=\mu _0^{-1}\boldsymbol{\nabla }\times \boldsymbol{B}$

is the plasma current density,

![]() $p$

is the plasma pressure, and

$p$

is the plasma pressure, and

![]() $\mu_0$

is the vacuum permeability. The magnetic field must, of course, be a solenoidal vector field,

$\mu_0$

is the vacuum permeability. The magnetic field must, of course, be a solenoidal vector field,

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{B}=0$

, and we define a toroidal magnetic flux

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{B}=0$

, and we define a toroidal magnetic flux

![]() $2\pi \psi$

whose level sets define nested flux surfaces satisfying

$2\pi \psi$

whose level sets define nested flux surfaces satisfying

![]() $\boldsymbol{B}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }\psi =0$

. Both the global equilibrium solver and the near-axis description attempt the construction of equilibrium fields of this form.

$\boldsymbol{B}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }\psi =0$

. Both the global equilibrium solver and the near-axis description attempt the construction of equilibrium fields of this form.

Within this set of equations, we confer on the latter two a more prominent role. That is, we prioritise the magnetic field being solenoidal and having nested flux surfaces, which we impose on the field in an exact form. This is done by adopting the inverse-coordinate form of the problem (Bauer, Betancourt & Garabedian Reference Bauer, Betancourt and Garabedian1978; Hirshman & Whitson Reference Hirshman and Whitson1983). Instead of describing the magnetic field

![]() $\boldsymbol{B}$

explicitly as a function of space, we instead focus on describing the magnetic flux surfaces on which the field lives, as well as the form in which field lines wrap over them.

$\boldsymbol{B}$

explicitly as a function of space, we instead focus on describing the magnetic flux surfaces on which the field lives, as well as the form in which field lines wrap over them.

To construct such a description, we start by writing the magnetic field in its Clebsch form (D’haeseleer et al. Reference D’haeseleer, Hitchon, Callen and Shohet2012)

where

![]() $\vartheta$

and

$\vartheta$

and

![]() $\varphi$

are poloidal and toroidal angles (in straight field line coordinates with non-vanishing Jacobian), and

$\varphi$

are poloidal and toroidal angles (in straight field line coordinates with non-vanishing Jacobian), and

![]() $\iota$

(a function of

$\iota$

(a function of

![]() $\psi$

) is the rotational transform. A field written in this form satisfies both field requirements exactly. Defining a position vector

$\psi$

) is the rotational transform. A field written in this form satisfies both field requirements exactly. Defining a position vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}=\boldsymbol{x}(\psi ,\vartheta ,\varphi )$

, and taking that set of straight field line coordinates as our set of independent coordinates, the magnetic field may then be expressed as

$\boldsymbol{x}=\boldsymbol{x}(\psi ,\vartheta ,\varphi )$

, and taking that set of straight field line coordinates as our set of independent coordinates, the magnetic field may then be expressed as

where

![]() $\mathcal{J}_\vartheta =\partial _\psi \boldsymbol{x}\times \partial _\vartheta \boldsymbol{x}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\partial _\varphi \boldsymbol{x}$

is the Jacobian of the straight field line coordinate system. Full knowledge of flux surfaces in straight field line coordinates (i.e.

$\mathcal{J}_\vartheta =\partial _\psi \boldsymbol{x}\times \partial _\vartheta \boldsymbol{x}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\partial _\varphi \boldsymbol{x}$

is the Jacobian of the straight field line coordinate system. Full knowledge of flux surfaces in straight field line coordinates (i.e.

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}$

), along with the rotational transform, uniquely defines the magnetic field. Alternatively, one could provide information about the average toroidal current rather than the rotational transform (see Appendix A).

$\boldsymbol{x}$

), along with the rotational transform, uniquely defines the magnetic field. Alternatively, one could provide information about the average toroidal current rather than the rotational transform (see Appendix A).

The central task is then to find a function

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}(\psi ,\vartheta ,\varphi )$

, which we may represent in a multitude of ways. The NAE, in its inverse-coordinate form pioneered by Garren & Boozer (Reference Garren and Boozer1991c

), takes as a reference of this

$\boldsymbol{x}(\psi ,\vartheta ,\varphi )$

, which we may represent in a multitude of ways. The NAE, in its inverse-coordinate form pioneered by Garren & Boozer (Reference Garren and Boozer1991c

), takes as a reference of this

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}$

the magnetic axis. This is a natural choice given that the NAE is concerned with providing a consistent asymptotic description of the field near the magnetic axis (i.e.

$\boldsymbol{x}$

the magnetic axis. This is a natural choice given that the NAE is concerned with providing a consistent asymptotic description of the field near the magnetic axis (i.e.

![]() $\psi =0$

). Explicitly,

$\psi =0$

). Explicitly,

where

![]() $\boldsymbol{r}_0$

describes the magnetic axis, and the vector triad

$\boldsymbol{r}_0$

describes the magnetic axis, and the vector triad

![]() $\{\hat {\boldsymbol \kappa },\hat {\boldsymbol \tau },\hat {\boldsymbol{t}}\}$

corresponds to the Frenet–Serret basis (Frenet Reference Frenet1852; Animov Reference Animov2001) (namely, the normal, binormal and tangent vectors defined with respect to the magnetic axis). Here, we specialise to regular magnetic axes with no, or only few, isolated flattening points (i.e. vanishing curvature points) in which such a frame (or its signed version (Carroll, Köse & Sterling Reference Carroll, Köse and Sterling2013; Plunk et al. Reference Plunk, Landreman and Helander2019; Camacho Mata & Plunk Reference Camacho Mata and Plunk2023; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Plunk and Jorge2025)) exists. This is enough to describe the asymptotic behaviour of all optimised configurations; namely, quasisymmetric and quasi-isodynamic ones (Gori, Lotz & Nührenberg Reference Gori, Lotz and Nührenberg1997; Plunk et al. Reference Plunk, Landreman and Helander2019). In the NAE, then, finding a magnetic field corresponds to finding an asymptotic form of the functions

$\{\hat {\boldsymbol \kappa },\hat {\boldsymbol \tau },\hat {\boldsymbol{t}}\}$

corresponds to the Frenet–Serret basis (Frenet Reference Frenet1852; Animov Reference Animov2001) (namely, the normal, binormal and tangent vectors defined with respect to the magnetic axis). Here, we specialise to regular magnetic axes with no, or only few, isolated flattening points (i.e. vanishing curvature points) in which such a frame (or its signed version (Carroll, Köse & Sterling Reference Carroll, Köse and Sterling2013; Plunk et al. Reference Plunk, Landreman and Helander2019; Camacho Mata & Plunk Reference Camacho Mata and Plunk2023; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Plunk and Jorge2025)) exists. This is enough to describe the asymptotic behaviour of all optimised configurations; namely, quasisymmetric and quasi-isodynamic ones (Gori, Lotz & Nührenberg Reference Gori, Lotz and Nührenberg1997; Plunk et al. Reference Plunk, Landreman and Helander2019). In the NAE, then, finding a magnetic field corresponds to finding an asymptotic form of the functions

![]() $X,\,Y$

and

$X,\,Y$

and

![]() $Z$

, which describe the shape of flux surfaces, alongside the rotational transform and the axis shape. This description is performed in a special class of straight field line coordinates, Boozer coordinates

$Z$

, which describe the shape of flux surfaces, alongside the rotational transform and the axis shape. This description is performed in a special class of straight field line coordinates, Boozer coordinates

![]() $\{\psi ,\vartheta _{B},\varphi _{B}\}$

, which eases the treatment of optimised stellarators due to the simple involvement of

$\{\psi ,\vartheta _{B},\varphi _{B}\}$

, which eases the treatment of optimised stellarators due to the simple involvement of

![]() $|\boldsymbol{B}|$

(Boozer Reference Boozer1981), which imposes additional constraints in the construction.

$|\boldsymbol{B}|$

(Boozer Reference Boozer1981), which imposes additional constraints in the construction.

In the case of the global equilibrium description, the numerical solver DESC, which we shall focus on, describes flux surfaces not with respect to the axis (unlike new developments (Hindenlang et al. Reference Hindenlang, Plunk and Maj2025)), but in cylindrical coordinates so that

It is then the task of the solver to find the appropriate

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $Z$

functions as a function of

$Z$

functions as a function of

![]() $\{\psi ,\,\vartheta ,\,\varphi \}$

. Given that the description is in cylindrical coordinates, the toroidal angle is naturally chosen to be the cylindrical one,

$\{\psi ,\,\vartheta ,\,\varphi \}$

. Given that the description is in cylindrical coordinates, the toroidal angle is naturally chosen to be the cylindrical one,

![]() $\phi$

.Footnote

1

Because we insist on this specific form of the toroidal angle, it requires a very particular choice of the poloidal angle

$\phi$

.Footnote

1

Because we insist on this specific form of the toroidal angle, it requires a very particular choice of the poloidal angle

![]() $\vartheta$

in order to guarantee the coordinate system to be a straight field line coordinate system. This coordinate system is known as PEST coordinates

$\vartheta$

in order to guarantee the coordinate system to be a straight field line coordinate system. This coordinate system is known as PEST coordinates

![]() $\{\psi ,\vartheta _{\mathrm{PEST}},\phi \}$

. However, the global solver does not know at the starting point what

$\{\psi ,\vartheta _{\mathrm{PEST}},\phi \}$

. However, the global solver does not know at the starting point what

![]() $\vartheta _{\mathrm{PEST}}$

is, as this depends on the final magnetic field solution. Hence, in practice, the solver must introduce a stream function

$\vartheta _{\mathrm{PEST}}$

is, as this depends on the final magnetic field solution. Hence, in practice, the solver must introduce a stream function

![]() $\lambda$

such that

$\lambda$

such that

![]() $\vartheta _{\mathrm{PEST}}=\theta +\lambda$

, where

$\vartheta _{\mathrm{PEST}}=\theta +\lambda$

, where

![]() $\theta$

can be any arbitrary poloidal angle used by the equilibrium solver. In that case, the magnetic field, as in (2.2) is written as

$\theta$

can be any arbitrary poloidal angle used by the equilibrium solver. In that case, the magnetic field, as in (2.2) is written as

Where now the Jacobian is of the computational coordinates

![]() $\mathcal{J}_\theta =\partial _\psi \boldsymbol{x}\times \partial _\theta \boldsymbol{x}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\partial _\varphi \boldsymbol{x}\!$

. In the case of the global solver then, a magnetic field is uniquely described by finding functions

$\mathcal{J}_\theta =\partial _\psi \boldsymbol{x}\times \partial _\theta \boldsymbol{x}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\partial _\varphi \boldsymbol{x}\!$

. In the case of the global solver then, a magnetic field is uniquely described by finding functions

![]() $R,\,Z$

and

$R,\,Z$

and

![]() $\lambda$

as a function of

$\lambda$

as a function of

![]() $\{\psi ,\,\theta ,\,\phi \}$

.

$\{\psi ,\,\theta ,\,\phi \}$

.

So far, we have only represented a magnetic field but have not yet solved the equilibrium. We must still find a consistent set of flux surfaces

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}$

(described in appropriate coordinates), such that the resulting magnetic field is in equilibrium. We must deform flux surfaces until the field comes to equilibrium; i.e. it minimises the force residual

$\boldsymbol{x}$

(described in appropriate coordinates), such that the resulting magnetic field is in equilibrium. We must deform flux surfaces until the field comes to equilibrium; i.e. it minimises the force residual

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}=\boldsymbol{j}\times \boldsymbol{B}-\boldsymbol{\nabla }p$

for a prescribed function

$\boldsymbol{F}=\boldsymbol{j}\times \boldsymbol{B}-\boldsymbol{\nabla }p$

for a prescribed function

![]() $p(\psi )$

. In the context of the NAE, the consistent construction of flux surfaces and Boozer coordinates can be carried out systematically by setting

$p(\psi )$

. In the context of the NAE, the consistent construction of flux surfaces and Boozer coordinates can be carried out systematically by setting

![]() $\boldsymbol{F} = \boldsymbol{0}$

order by order, and detailed descriptions of how to do this may be found in Landreman & Sengupta (Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019) and Rodríguez et al. (Reference Rodríguez, Plunk and Jorge2025). We content ourselves with knowing that, at the end of the day, we will be able to have an asymptotic form of a

$\boldsymbol{F} = \boldsymbol{0}$

order by order, and detailed descriptions of how to do this may be found in Landreman & Sengupta (Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019) and Rodríguez et al. (Reference Rodríguez, Plunk and Jorge2025). We content ourselves with knowing that, at the end of the day, we will be able to have an asymptotic form of a

![]() $X,Y,Z$

rotational transform and the axis shape.

$X,Y,Z$

rotational transform and the axis shape.

The equilibrium solver DESC seeks equilibria by numerically and iteratively minimising the force residual

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}$

directly. Note that this is not the only existing practical approach, with the important case of the VMEC code approaching the problem by minimising energy (Hirshman & Whitson Reference Hirshman and Whitson1983). To be more explicit about the force residual, consider first the covariant form of the magnetic field

$\boldsymbol{F}$

directly. Note that this is not the only existing practical approach, with the important case of the VMEC code approaching the problem by minimising energy (Hirshman & Whitson Reference Hirshman and Whitson1983). To be more explicit about the force residual, consider first the covariant form of the magnetic field

There might appear to be new information in the problem, but all of the covariant components in (2.6) can be directly computed from the geometry by simply leveraging the dual relations (D’haeseleer et al. Reference D’haeseleer, Hitchon, Callen and Shohet2012, (2.3.12)–(2.3.13))

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }q_i=\epsilon _{ijk}\partial _{q_j}\boldsymbol{x}\times \partial _{q_k}\boldsymbol{x}$

and (2.5a

). With this, the force residual is (see Panici et al. (Reference Panici, Conlin, Dudt, Unalmis and Kolemen2023) as well)

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }q_i=\epsilon _{ijk}\partial _{q_j}\boldsymbol{x}\times \partial _{q_k}\boldsymbol{x}$

and (2.5a

). With this, the force residual is (see Panici et al. (Reference Panici, Conlin, Dudt, Unalmis and Kolemen2023) as well)

The

![]() $\boldsymbol{\nabla }\psi$

component can be interpreted as the radial force balance equation, with the helical component representing

$\boldsymbol{\nabla }\psi$

component can be interpreted as the radial force balance equation, with the helical component representing

![]() $\boldsymbol{j}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }\psi$

. Thus, the global solver is set to find

$\boldsymbol{j}\boldsymbol{\cdot }\boldsymbol{\nabla }\psi$

. Thus, the global solver is set to find

![]() $\{R,\,Z,\,\lambda \}$

as a function of

$\{R,\,Z,\,\lambda \}$

as a function of

![]() $\{\psi ,\theta ,\phi \}$

that make (2.7) vanish.

$\{\psi ,\theta ,\phi \}$

that make (2.7) vanish.

The near-axis and global treatments of the problem thus have a key difference not only in the coordinate representation used, but also in their treatment of boundary conditions. One must provide certain inputs to the equilibrium problem to describe different equilibria. In the NAE case, this prescription occurs outwards; that is, one must provide the shape of the axis, and then, order by order, some features of the flux surfaces away from it. Which features must be provided depends on the type of stellarator under consideration, and the order of the expansion of interest (see Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Plunk and Jorge2025). The global solution fundamentally attempts the opposite: one specifies the shape of the boundary, and the solution is constructed inwards (what is known as a fixed-boundary solution). This is most straightforwardly understood by imagining a vacuum field in the form of Laplace’s equation. From this difference it should be clear that there is not a one-to-one correspondence between the two approaches. A finite truncated near-axis construction does not, in principle, uniquely describe a global field solution, but rather simply constrains its core behaviour. We are now in a position to connect both.

2.2. Near-axis expansion in DESC

In the NAE we learned that the description of flux surfaces

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}(\psi ,\vartheta _B,\varphi _B)$

is given by

$\boldsymbol{x}(\psi ,\vartheta _B,\varphi _B)$

is given by

![]() $\{X,Y,Z\}$

, (2.3). The forms of

$\{X,Y,Z\}$

, (2.3). The forms of

![]() $\{X,Y,Z\}$

are particularly simple, as may be directly appreciated by considering their Taylor–Fourier expansion (Garren & Boozer Reference Garren and Boozer1991c

; Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019)

$\{X,Y,Z\}$

are particularly simple, as may be directly appreciated by considering their Taylor–Fourier expansion (Garren & Boozer Reference Garren and Boozer1991c

; Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019)

\begin{equation} f(\psi ,\theta _{B},\varphi _{B})=\sum _{l=0}^\infty r^l\sum _{m=0}^l{}^{\prime }\left (f_{lm}^C(\varphi _{B})\cos m\vartheta _{B}+f_{lm}^S(\varphi _B)\sin m\vartheta _{B}\right )\!, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} f(\psi ,\theta _{B},\varphi _{B})=\sum _{l=0}^\infty r^l\sum _{m=0}^l{}^{\prime }\left (f_{lm}^C(\varphi _{B})\cos m\vartheta _{B}+f_{lm}^S(\varphi _B)\sin m\vartheta _{B}\right )\!, \end{equation}

where

![]() $r=\sqrt {2\psi /\bar {B}}$

is a pseudo-radial coordinate,

$r=\sqrt {2\psi /\bar {B}}$

is a pseudo-radial coordinate,

![]() $\bar {B}$

is a representative normalisation value of the magnetic field and the sum

$\bar {B}$

is a representative normalisation value of the magnetic field and the sum

![]() $\sum '$

denotes sum over even or odd orders depending on the parity of

$\sum '$

denotes sum over even or odd orders depending on the parity of

![]() $l$

. Because the poloidal dependence grows in a controlled manner linked to the powers of

$l$

. Because the poloidal dependence grows in a controlled manner linked to the powers of

![]() $r$

, the flux surfaces gain complexity order by order; they start by being elliptical, then acquire triangularity, and so on.

$r$

, the flux surfaces gain complexity order by order; they start by being elliptical, then acquire triangularity, and so on.

To impose this asymptotic form of the field on the global equilibrium solver, we must be able to relate this asymptotic description to the representation in DESC, and constrain the latter according to the former. The structure in (2.8) is a consequence of maintaining the field description singularity free close to the magnetic axis (

![]() $\psi =0$

) (Kuo-Petravic & Boozer Reference Kuo-Petravic and Boozer1987; Garren & Boozer Reference Garren and Boozer1991b

; Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2018). This requirement was indeed observed in the implementation of DESC, where the global solver employs a Zernike basis to represent

$\psi =0$

) (Kuo-Petravic & Boozer Reference Kuo-Petravic and Boozer1987; Garren & Boozer Reference Garren and Boozer1991b

; Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2018). This requirement was indeed observed in the implementation of DESC, where the global solver employs a Zernike basis to represent

![]() $\{R,Z,\lambda \}$

, crucially coupling the powers of DESC’s chosen pseudo-radial coordinate

$\{R,Z,\lambda \}$

, crucially coupling the powers of DESC’s chosen pseudo-radial coordinate

![]() $\rho =\sqrt {\psi /\psi _{\mathrm{edge}}}$

to the poloidal modes

$\rho =\sqrt {\psi /\psi _{\mathrm{edge}}}$

to the poloidal modes

![]() $\theta$

. This makes the treatment in DESC close to the form used in the near-axis description.

$\theta$

. This makes the treatment in DESC close to the form used in the near-axis description.

To make that connection, however, we must consider the differences carefully. One is the use of different re-scaled pseudo-radial coordinates; we may relate

![]() $\rho$

to the NAE

$\rho$

to the NAE

![]() $r$

by

$r$

by

![]() $\rho =r\sqrt {\bar {B}/2\psi _{\mathrm{edge}}}$

. The second point of difference is the use of a different poloidal angle. While the near-axis description uses the poloidal Boozer angle,

$\rho =r\sqrt {\bar {B}/2\psi _{\mathrm{edge}}}$

. The second point of difference is the use of a different poloidal angle. While the near-axis description uses the poloidal Boozer angle,

![]() $\vartheta _{B}$

, the global equilibrium is described in a general poloidal angle

$\vartheta _{B}$

, the global equilibrium is described in a general poloidal angle

![]() $\theta$

. The simplest comparison between the two descriptions is then made when

$\theta$

. The simplest comparison between the two descriptions is then made when

![]() $\theta$

is forced to match the Boozer angle, at least to leading order near the axis. When imposing the near-axis constraints on

$\theta$

is forced to match the Boozer angle, at least to leading order near the axis. When imposing the near-axis constraints on

![]() $\theta$

as if it were Boozer coordinates, the solver is forced to use a very particular form of

$\theta$

as if it were Boozer coordinates, the solver is forced to use a very particular form of

![]() $\lambda$

, and thus can be overly constraining. Defining

$\lambda$

, and thus can be overly constraining. Defining

![]() $\nu =\varphi _{B}-\phi$

as the function that maps the Boozer toroidal angle to the cylindrical one, our choice of

$\nu =\varphi _{B}-\phi$

as the function that maps the Boozer toroidal angle to the cylindrical one, our choice of

![]() $\theta$

dictates that

$\theta$

dictates that

This simplest choice of poloidal angle could be modified to accommodate a more general and efficient

![]() $\theta$

. Details about how this would be incorporated are shown in Appendix B, but we shall nevertheless consider the simplest scenario in the main body of the paper, which should suffice as a proof of principle.

$\theta$

. Details about how this would be incorporated are shown in Appendix B, but we shall nevertheless consider the simplest scenario in the main body of the paper, which should suffice as a proof of principle.

With the coordinates in place, what remains from the comparison is the different radial–poloidal structure of the NAE expansion and the Zernike basis. In the equilibrium solver a generic function is written as (ignoring the toroidal coordinate for now)

\begin{equation} f(\rho ,\theta )=\sum _{l=0}^\infty \sum _{m=-l}^l{}^{\prime }f_{lm}\mathcal{Z}_l^m(\rho ,\theta ), \end{equation}

\begin{equation} f(\rho ,\theta )=\sum _{l=0}^\infty \sum _{m=-l}^l{}^{\prime }f_{lm}\mathcal{Z}_l^m(\rho ,\theta ), \end{equation}

where the

![]() $\sum ^{\prime }$

again denotes a sum over the same parity as

$\sum ^{\prime }$

again denotes a sum over the same parity as

![]() $l$

, and the Zernike polynomials are

$l$

, and the Zernike polynomials are

where the radial parts are the shifted Jacobi polynomials, given as

\begin{equation} \mathcal{R}_l^{|m|}=\sum _{k=0}^{(l-|m|)/2}\frac {(-1)^k(l-k)!}{k!\left ((({l+m})/{2})-k\right )!\left ((({l-m})/{2})-k\right )!}\rho ^{l-2k}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \mathcal{R}_l^{|m|}=\sum _{k=0}^{(l-|m|)/2}\frac {(-1)^k(l-k)!}{k!\left ((({l+m})/{2})-k\right )!\left ((({l-m})/{2})-k\right )!}\rho ^{l-2k}. \end{equation}

The coefficients

![]() $\{f_{lm}\}$

for

$\{f_{lm}\}$

for

![]() $\{R,Z,\lambda \}$

are the set which DESC solves for in order to construct the equilibrium field. To make a one-to-one connection to the NAE, (2.8), we need to unravel this sum and pick the different powers of

$\{R,Z,\lambda \}$

are the set which DESC solves for in order to construct the equilibrium field. To make a one-to-one connection to the NAE, (2.8), we need to unravel this sum and pick the different powers of

![]() $\rho$

. Generally, a function

$\rho$

. Generally, a function

![]() $f$

defined by

$f$

defined by

![]() $f_{lm}$

coefficients can be written in terms of the equivalent near-axis coefficients as

$f_{lm}$

coefficients can be written in terms of the equivalent near-axis coefficients as

\begin{equation} f_{l|m|}^{C/S}=\left (\frac {\rho }{r}\right )^l\times \begin{cases} \begin{aligned} &(-1)^{l/2}\sum _{k=l/2}^\infty \Bigg [ (-1)^k\binom {k+l/2}{l}\\&\hspace {1in} \times \binom {l}{(l-|m|)/2}f_{2k,m}\Bigg ]\quad |m| \mathrm{\,is\,even} ,\\ &(-1)^{(l+1)/2}\sum _{k=(l+1)/2}^\infty \Bigg [(-1)^k\binom {k+(l-1)/2}{l}\\&\hspace {1in}\times \binom {l}{(l-|m|)/2}f_{2k-1,m}\Bigg ] \quad |m| \mathrm{\,is\,odd}, \\ \end{aligned} \end{cases} \end{equation}

\begin{equation} f_{l|m|}^{C/S}=\left (\frac {\rho }{r}\right )^l\times \begin{cases} \begin{aligned} &(-1)^{l/2}\sum _{k=l/2}^\infty \Bigg [ (-1)^k\binom {k+l/2}{l}\\&\hspace {1in} \times \binom {l}{(l-|m|)/2}f_{2k,m}\Bigg ]\quad |m| \mathrm{\,is\,even} ,\\ &(-1)^{(l+1)/2}\sum _{k=(l+1)/2}^\infty \Bigg [(-1)^k\binom {k+(l-1)/2}{l}\\&\hspace {1in}\times \binom {l}{(l-|m|)/2}f_{2k-1,m}\Bigg ] \quad |m| \mathrm{\,is\,odd}, \\ \end{aligned} \end{cases} \end{equation}

and the sign of

![]() $m$

has been taken to represent, as is the case in the DESC notation, the sine or cosine terms

$m$

has been taken to represent, as is the case in the DESC notation, the sine or cosine terms

![]() $S/C$

(negative and positive respectively).Footnote

2

The above only holds for

$S/C$

(negative and positive respectively).Footnote

2

The above only holds for

![]() $l\geqslant |m|$

, and

$l\geqslant |m|$

, and

![]() $m$

sharing the same parity as

$m$

sharing the same parity as

![]() $l$

. Otherwise, the contribution will be zero. Note how, for large

$l$

. Otherwise, the contribution will be zero. Note how, for large

![]() $k$

at constant

$k$

at constant

![]() $l$

and

$l$

and

![]() $m$

, the factor in front of the Zernike components goes like

$m$

, the factor in front of the Zernike components goes like

![]() $\sim k^l$

. This shows the exponential contribution from the higher-order Zernike modes, which must therefore be conveniently truncated. See details on the derivation in Appendix C. Thus, imposing the near-axis behaviour constitutes imposing constraints on linear combinations of the DESC degrees of freedom.

$\sim k^l$

. This shows the exponential contribution from the higher-order Zernike modes, which must therefore be conveniently truncated. See details on the derivation in Appendix C. Thus, imposing the near-axis behaviour constitutes imposing constraints on linear combinations of the DESC degrees of freedom.

As a final remark, we note that what have been referred to as coefficients

![]() $f_{lm}$

so far are generally functions of

$f_{lm}$

so far are generally functions of

![]() $\phi$

. In the pseudo-spectral representation of DESC, we may then treat the toroidal dependence with a Fourier series in

$\phi$

. In the pseudo-spectral representation of DESC, we may then treat the toroidal dependence with a Fourier series in

![]() $\phi$

, with the

$\phi$

, with the

![]() $n$

Fourier components corresponding to

$n$

Fourier components corresponding to

![]() $f_{lmn}$

, with

$f_{lmn}$

, with

![]() $n\geqslant 0$

representing cosines, and

$n\geqslant 0$

representing cosines, and

![]() $n\lt 0$

sines.

$n\lt 0$

sines.

3. Constraining the global equilibrium

Equations (2.13) define a linear mapping between the Zernike and the NAE basis. If the latter is specified, then, the above constitutes a constraint on a linear combination of Zernike components. It might thus seem that there is nothing else that needs to be done in order to bridge the NAE and the global equilibrium solver. However, it is not the full story.

As discussed earlier, the description of flux surfaces, the central element in the description of the field, assumed a different form in the standard near-axis approach to equilibrium versus how the solver DESC treats the problem, (2.3) and (2.4). The latter employs a cylindrical geometry in real space

![]() $R(\rho ,\theta ,\phi )$

and

$R(\rho ,\theta ,\phi )$

and

![]() $Z(\rho ,\theta ,\phi )$

, where

$Z(\rho ,\theta ,\phi )$

, where

![]() $\phi$

must be the geometric cylindrical angle. This we may refer to as a description in the ‘laboratory frame’ (independent of the field). The description in the NAE, instead, is intimately linked to the form of the field itself, as surfaces are described with respect to the magnetic axis in its Frenet–Serret frame, and in Boozer coordinates. This implies that shapes described in the NAE need to be appropriately transformed into the ‘laboratory frame’ in order to impose the constraint on the field appropriately.

$\phi$

must be the geometric cylindrical angle. This we may refer to as a description in the ‘laboratory frame’ (independent of the field). The description in the NAE, instead, is intimately linked to the form of the field itself, as surfaces are described with respect to the magnetic axis in its Frenet–Serret frame, and in Boozer coordinates. This implies that shapes described in the NAE need to be appropriately transformed into the ‘laboratory frame’ in order to impose the constraint on the field appropriately.

3.1. Zeroth order: the magnetic axis

To leading order in the near-axis description, flux surfaces reduce to a single closed curve at the origin (

![]() $\psi =0$

):Footnote

3

the magnetic axis. In practice, such a closed curve is described as a set of Fourier harmonics (in

$\psi =0$

):Footnote

3

the magnetic axis. In practice, such a closed curve is described as a set of Fourier harmonics (in

![]() $\phi$

) in cylindrical coordinates

$\phi$

) in cylindrical coordinates

![]() $\{R,\,Z\}$

. That is,

$\{R,\,Z\}$

. That is,

\begin{align} R(\phi ) & =R_0+\sum _{n=1}^N \left(R_{n}^C\cos n\phi +R_{n}^S\sin n\phi \right)\!,\\[-12pt]\nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} R(\phi ) & =R_0+\sum _{n=1}^N \left(R_{n}^C\cos n\phi +R_{n}^S\sin n\phi \right)\!,\\[-12pt]\nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} Z(\phi ) & =\sum _{n=1}^N \left(Z_{n}^C\cos n\phi +Z_n^S\sin n\phi \right)\!,\end{align}

\begin{align} Z(\phi ) & =\sum _{n=1}^N \left(Z_{n}^C\cos n\phi +Z_n^S\sin n\phi \right)\!,\end{align}

where the Fourier coefficients are constant. This form of describing the axis is natural to NAE codes (such as pyQSC), and equilibrium codes (such as DESC). Following the discussion on the Zernike basis, using (C2), the relevant constraints for the Zernike modes are then

\begin{align} R_{n}^{C/S}=\sum _{k=0}^\infty (-1)^k R_{2k,0,\pm |n|},\\[-10pt]\nonumber\end{align}

\begin{align} R_{n}^{C/S}=\sum _{k=0}^\infty (-1)^k R_{2k,0,\pm |n|},\\[-10pt]\nonumber\end{align}

\begin{align} Z_{n}^{C/S}=\sum _{k=0}^\infty (-1)^k Z_{2k,0,\pm |n|}.\end{align}

\begin{align} Z_{n}^{C/S}=\sum _{k=0}^\infty (-1)^k Z_{2k,0,\pm |n|}.\end{align}

We shall thus have

![]() $2(2N+1)$

constraints to impose onto the Zernike harmonics in order to constrain the magnetic axis to match that of the NAE. No further geometric consideration is needed here.

$2(2N+1)$

constraints to impose onto the Zernike harmonics in order to constrain the magnetic axis to match that of the NAE. No further geometric consideration is needed here.

3.2. First order: elliptical surfaces

At first order things start to become more interesting, and we need to explicitly transform the constraints into cylindrical coordinates (the language of DESC) using the information in our magnetic-axis frame. This includes transforming the Boozer toroidal angle to the cylindrical angle

![]() $\phi$

. This transformation is routinely performed numerically by codes like pyQSC to represent near-axis magnetic fields in the laboratory frame, and was previously explored in Landreman & Sengupta (Reference Landreman and Sengupta2018). Here, we present an alternative simple geometric treatment of the problem.

$\phi$

. This transformation is routinely performed numerically by codes like pyQSC to represent near-axis magnetic fields in the laboratory frame, and was previously explored in Landreman & Sengupta (Reference Landreman and Sengupta2018). Here, we present an alternative simple geometric treatment of the problem.

Start by defining the flux surface as

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}=\boldsymbol{r}_0+\boldsymbol{x}_1$

, where

$\boldsymbol{x}=\boldsymbol{r}_0+\boldsymbol{x}_1$

, where

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_1\propto \rho$

and thus is in the asymptotic sense small. That is, we construct flux surfaces near the axis through a small displacement

$\boldsymbol{x}_1\propto \rho$

and thus is in the asymptotic sense small. That is, we construct flux surfaces near the axis through a small displacement

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_1$

from it, which is a function of

$\boldsymbol{x}_1$

from it, which is a function of

![]() $\rho ,\,\theta$

and

$\rho ,\,\theta$

and

![]() $\phi$

. Our task is to find

$\phi$

. Our task is to find

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $Z$

corresponding to these points. Start with

$Z$

corresponding to these points. Start with

![]() $R$

, the major radius, and consider the projection of the problem to a constant

$R$

, the major radius, and consider the projection of the problem to a constant

![]() $Z$

plane, which we define as the

$Z$

plane, which we define as the

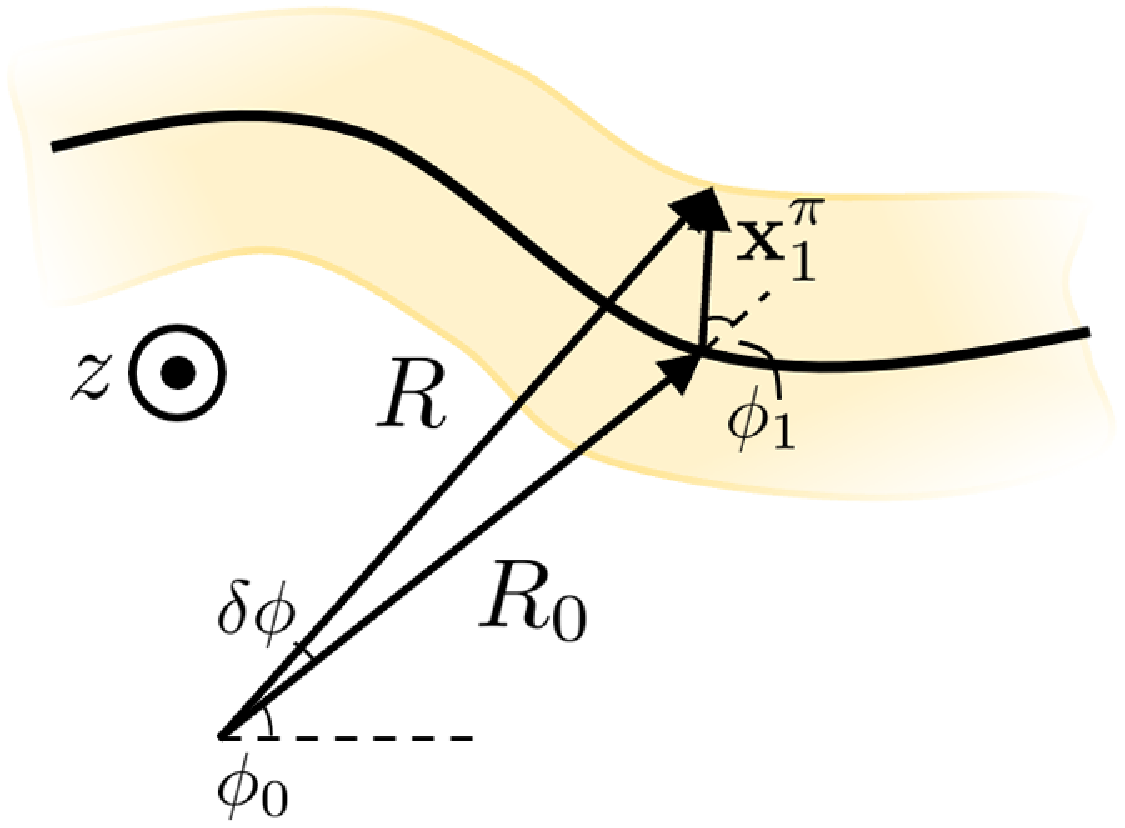

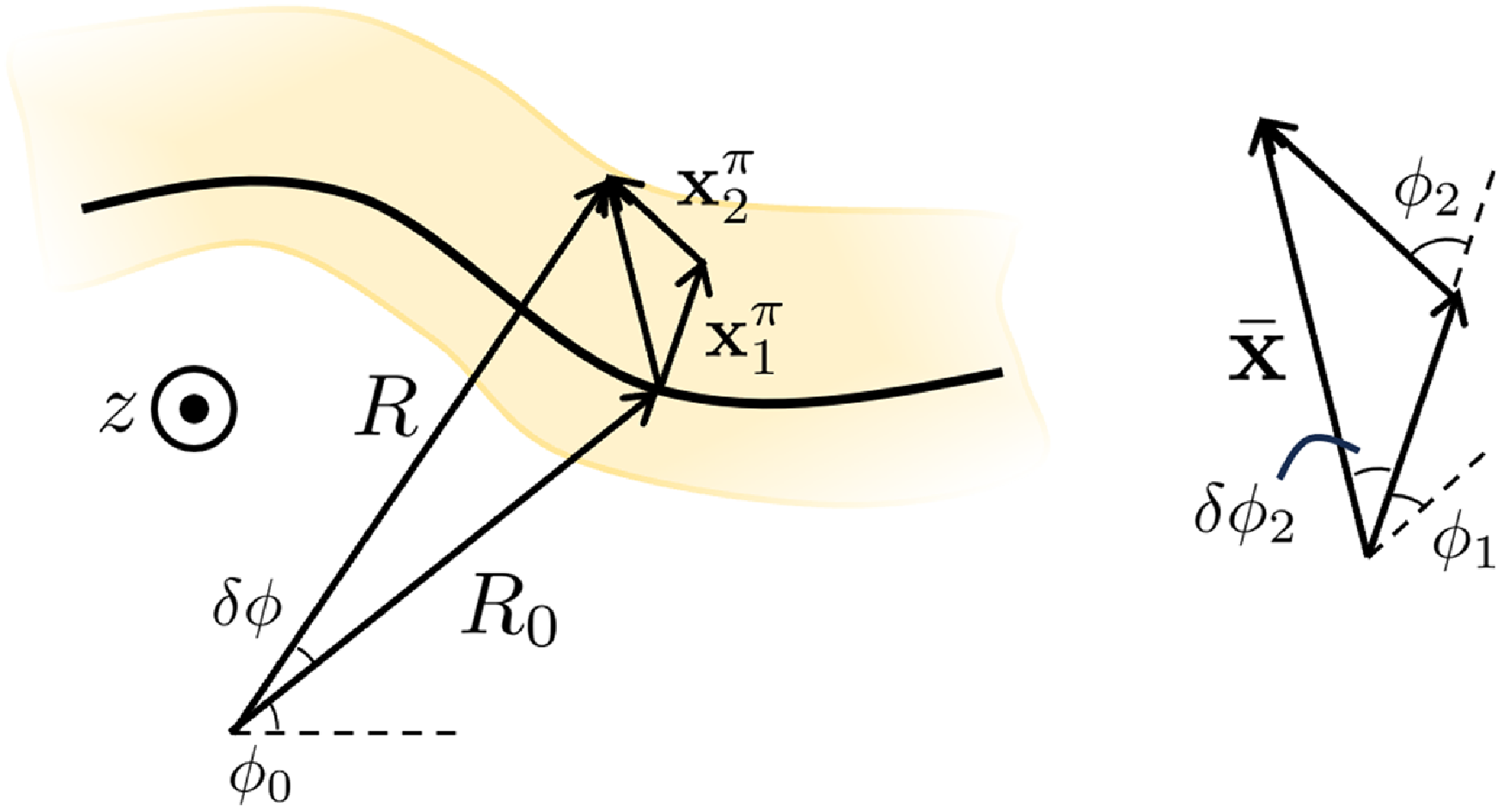

![]() $\pi$

plane (see the diagram in figure 1). Define a point on the magnetic axis by

$\pi$

plane (see the diagram in figure 1). Define a point on the magnetic axis by

![]() $R_0$

(the radial distance to a point along the axis), and

$R_0$

(the radial distance to a point along the axis), and

![]() $\phi _0$

(the cylindrical angle of said point). The displacement

$\phi _0$

(the cylindrical angle of said point). The displacement

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_1$

is then a function of that point (see figure 1), whose projection normal to

$\boldsymbol{x}_1$

is then a function of that point (see figure 1), whose projection normal to

![]() $z$

we define to be

$z$

we define to be

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_1^\pi$

. Define

$\boldsymbol{x}_1^\pi$

. Define

![]() $\phi _1$

to be the angle that

$\phi _1$

to be the angle that

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_1^\pi$

makes with

$\boldsymbol{x}_1^\pi$

makes with

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{R}}_0$

, which satisfies

$\hat {\boldsymbol{R}}_0$

, which satisfies

![]() $\cos \phi _1=\hat {\boldsymbol{R}}_0\times\boldsymbol{x}_1^\pi /|\boldsymbol{x}_1^\pi |$

. Here,

$\cos \phi _1=\hat {\boldsymbol{R}}_0\times\boldsymbol{x}_1^\pi /|\boldsymbol{x}_1^\pi |$

. Here,

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{R}}_0$

corresponds to the radial vector direction evaluated at the axis; that is,

$\hat {\boldsymbol{R}}_0$

corresponds to the radial vector direction evaluated at the axis; that is,

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol{R}}_0=\hat {\boldsymbol{R}}(\phi =\phi _0$

). We then define

$\hat {\boldsymbol{R}}_0=\hat {\boldsymbol{R}}(\phi =\phi _0$

). We then define

![]() $\delta \phi$

to be the angle which, when added to

$\delta \phi$

to be the angle which, when added to

![]() $\phi _0$

, results in the cylindrical toroidal angle of the point on the flux surface

$\phi _0$

, results in the cylindrical toroidal angle of the point on the flux surface

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_0+\boldsymbol{x}_1$

.

$\boldsymbol{x}_0+\boldsymbol{x}_1$

.

Figure 1. Diagram illustrating the key element for the geometric transformation at first order. Schematic diagram showing the position of a point on the surface (at radial distance

![]() $R$

and angle

$R$

and angle

![]() $\phi _0+\delta \phi$

), in reference to other quantities. These include the position along the magnetic axis (radial position

$\phi _0+\delta \phi$

), in reference to other quantities. These include the position along the magnetic axis (radial position

![]() $R_0$

and angle

$R_0$

and angle

![]() $\phi _0$

), and

$\phi _0$

), and

![]() $\rho \boldsymbol{x}_1$

from the axis to the point, projected onto the

$\rho \boldsymbol{x}_1$

from the axis to the point, projected onto the

![]() $R,\,\phi _c$

plane (superindex

$R,\,\phi _c$

plane (superindex

![]() $\pi$

).

$\pi$

).

Application of the sine rule gives

where

![]() $x_1^\phi =|\boldsymbol{x}_1^\pi |\sin \phi _1$

and only the leading piece in

$x_1^\phi =|\boldsymbol{x}_1^\pi |\sin \phi _1$

and only the leading piece in

![]() $\rho$

is being kept (so,

$\rho$

is being kept (so,

![]() $R \approx R_0$

) and

$R \approx R_0$

) and

![]() $\delta \phi \ll 1$

has been assumed. We define

$\delta \phi \ll 1$

has been assumed. We define

![]() $x_1^j=\boldsymbol{x}_1\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {j}$

for

$x_1^j=\boldsymbol{x}_1\boldsymbol{\cdot }\hat {j}$

for

![]() $j=R,\,\phi ,\,z$

as the projections of

$j=R,\,\phi ,\,z$

as the projections of

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_1$

along the cylindrical basis vectors, which when expressed in terms of the Frenet–Serret frame of the axis will involve various projections of the triad

$\boldsymbol{x}_1$

along the cylindrical basis vectors, which when expressed in terms of the Frenet–Serret frame of the axis will involve various projections of the triad

![]() $\{\hat {\boldsymbol \kappa },\hat {\boldsymbol \tau },\hat {\boldsymbol{t}}\}$

.

$\{\hat {\boldsymbol \kappa },\hat {\boldsymbol \tau },\hat {\boldsymbol{t}}\}$

.

Applying the cosine rule, and defining

![]() $R-R_0=\delta R$

, we find that to leading order in

$R-R_0=\delta R$

, we find that to leading order in

![]() $\rho$

$\rho$

Therefore, the radial position as a function of the geometric angle at the point on the surface,Footnote 4 is given as

where all the quantities in brackets are evaluated at

![]() $\phi$

, and

$\phi$

, and

![]() $R_0$

is a known function (from the shape of the magnetic axis). The quantity in square brackets is what will become the constraint on the Zernike basis, and in the asymptotic sense is correct to

$R_0$

is a known function (from the shape of the magnetic axis). The quantity in square brackets is what will become the constraint on the Zernike basis, and in the asymptotic sense is correct to

![]() $O(\rho )$

.

$O(\rho )$

.

Then, plugging in our expressions for

![]() $\delta \phi$

and

$\delta \phi$

and

![]() $\delta R$

, the first-order

$\delta R$

, the first-order

![]() $\rho$

terms in

$\rho$

terms in

![]() $R$

are

$R$

are

This form preserves the simple

![]() $\theta$

-harmonic content of

$\theta$

-harmonic content of

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_1$

, which from the near axis has the simple form

$\boldsymbol{x}_1$

, which from the near axis has the simple form

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_1=\cos \theta (X_1^c\hat {\boldsymbol \kappa }+Y_1^c\hat {\boldsymbol \tau })+\sin \theta (X_1^s \hat {\boldsymbol \kappa } + Y_1^s\hat {\boldsymbol \tau } )$

. Thus, (3.6) can be written as

$\boldsymbol{x}_1=\cos \theta (X_1^c\hat {\boldsymbol \kappa }+Y_1^c\hat {\boldsymbol \tau })+\sin \theta (X_1^s \hat {\boldsymbol \kappa } + Y_1^s\hat {\boldsymbol \tau } )$

. Thus, (3.6) can be written as

![]() $R_1=\mathcal{R}_{1,1}(\phi )\cos \theta +\mathcal{R}_{1,-1}(\phi )\sin \theta$

, where the form of the coefficients follows directly from (3.6) and the form of

$R_1=\mathcal{R}_{1,1}(\phi )\cos \theta +\mathcal{R}_{1,-1}(\phi )\sin \theta$

, where the form of the coefficients follows directly from (3.6) and the form of

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_1$

(these are derived explicitly in Appendix D). The subscripts in

$\boldsymbol{x}_1$

(these are derived explicitly in Appendix D). The subscripts in

![]() $\mathcal{R}_{nm}$

refer to the radial and poloidal orders of the term, respectively. To evaluate these we need the projections of the axis normal and binormal onto the cylindrical basis, information which is known in the context of the NAE (numerically calculated by codes like pyQSC).

$\mathcal{R}_{nm}$

refer to the radial and poloidal orders of the term, respectively. To evaluate these we need the projections of the axis normal and binormal onto the cylindrical basis, information which is known in the context of the NAE (numerically calculated by codes like pyQSC).

For

![]() $Z$

, analogously, we get

$Z$

, analogously, we get

where

![]() $Z_0(\phi )$

is the

$Z_0(\phi )$

is the

![]() $Z$

of the magnetic axis that is known fully as a function of

$Z$

of the magnetic axis that is known fully as a function of

![]() $\phi$

. Once again, one may collect terms to construct

$\phi$

. Once again, one may collect terms to construct

![]() $Z_1=\mathcal{Z}_{1,1}(\phi )\cos \theta +\mathcal{Z}_{1,-1}(\phi )\sin \theta$

.

$Z_1=\mathcal{Z}_{1,1}(\phi )\cos \theta +\mathcal{Z}_{1,-1}(\phi )\sin \theta$

.

Using (C4), we may (using DESC notation) write

\begin{align} \frac {r}{\rho }\mathcal{R}_{1,1,n} &= -\sum _{k=1}^M(-1)^kkR_{2k-1,1,n},\\[-10pt]\nonumber\end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {r}{\rho }\mathcal{R}_{1,1,n} &= -\sum _{k=1}^M(-1)^kkR_{2k-1,1,n},\\[-10pt]\nonumber\end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {r}{\rho }\mathcal{R}_{1,-1,n} & = -\sum _{k=1}^M(-1)^kkR_{2k-1,-1,n},\end{align}

\begin{align} \frac {r}{\rho }\mathcal{R}_{1,-1,n} & = -\sum _{k=1}^M(-1)^kkR_{2k-1,-1,n},\end{align}

for all

![]() $n\in [-N,N]$

representing Fourier components in

$n\in [-N,N]$

representing Fourier components in

![]() $\phi$

, and the negative sign corresponds to the sine

$\phi$

, and the negative sign corresponds to the sine

![]() $\phi$

components. The left-hand sides represent the NAE components, which may be obtained through the NAE, and thus serve as constraints on the DESC Fourier–Zernike mode amplitudes, which appear on the right-hand side. The constraints for

$\phi$

components. The left-hand sides represent the NAE components, which may be obtained through the NAE, and thus serve as constraints on the DESC Fourier–Zernike mode amplitudes, which appear on the right-hand side. The constraints for

![]() $Z$

have exactly the same form but with

$Z$

have exactly the same form but with

![]() $\mathcal{Z}$

.

$\mathcal{Z}$

.

3.2.1. Straight field line angle

Recall that, in order to complete the description of a field in DESC, it is important to find the streamfunction

![]() $\lambda$

that transforms the angle

$\lambda$

that transforms the angle

![]() $\theta$

to the PEST poloidal coordinate. In the approach here, and given that the near-axis expressions in Boozer coordinates are being used as constraints, we have (at least asymptotically)

$\theta$

to the PEST poloidal coordinate. In the approach here, and given that the near-axis expressions in Boozer coordinates are being used as constraints, we have (at least asymptotically)

![]() $\theta =\vartheta _B$

, and thus

$\theta =\vartheta _B$

, and thus

![]() $\lambda =-\iota \nu$

, (2.9). Hence, by constraining

$\lambda =-\iota \nu$

, (2.9). Hence, by constraining

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $Z$

as above, and in order for DESC to find an equilibrium,

$Z$

as above, and in order for DESC to find an equilibrium,

![]() $\lambda$

is in practice constrained.

$\lambda$

is in practice constrained.

To find what this

![]() $\lambda$

is expected to be, we need to find

$\lambda$

is expected to be, we need to find

![]() $\phi$

, the cylindrical angle, as a function of

$\phi$

, the cylindrical angle, as a function of

![]() $\phi _{B}$

and

$\phi _{B}$

and

![]() $\vartheta _{B}$

within the NAE. We may write

$\vartheta _{B}$

within the NAE. We may write

![]() $\phi =\phi ^{(0)}(\varphi _B)+r\phi ^{(1)}(\vartheta _B,\varphi _B)+\cdots$

, in which the leading-order expression is (Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019 (A20))

$\phi =\phi ^{(0)}(\varphi _B)+r\phi ^{(1)}(\vartheta _B,\varphi _B)+\cdots$

, in which the leading-order expression is (Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019 (A20))

where

![]() $\ell$

is the length along the magnetic axis,

$\ell$

is the length along the magnetic axis,

![]() $B_0$

the magnetic field magnitude,

$B_0$

the magnetic field magnitude,

![]() $G_0$

the poloidal Boozer current and

$G_0$

the poloidal Boozer current and

![]() $\iota _0$

the rotational transform, all the zero subscripts indicating evaluation on axis.

$\iota _0$

the rotational transform, all the zero subscripts indicating evaluation on axis.

The first correction

![]() $\phi ^{(1)}$

is directly related to

$\phi ^{(1)}$

is directly related to

![]() $\delta \phi$

in (3.3), so that

$\delta \phi$

in (3.3), so that

![]() $\nu ^{(1)}=-\delta \phi _1=-x_1^\phi /R_0$

, parametrised with the cylindrical angle on axis. Parametrised in terms of the standard cylindrical angle it would read

$\nu ^{(1)}=-\delta \phi _1=-x_1^\phi /R_0$

, parametrised with the cylindrical angle on axis. Parametrised in terms of the standard cylindrical angle it would read

where the prime denotes a toroidal derivative.

3.2.2. Interpretation of the first-order transformation

The above might appear to be a purely formal artefact resulting from the change of frame, but it has a straightforward geometric interpretation. The expressions in (3.6) and (3.7) show the difference in describing the shape of cross-sections in the near-axis frame (cutting flux surfaces normal to the magnetic axis) and the ‘laboratory frame’ (where the cuts are made at constant cylindrical toroidal angle). The elliptical cross-sections that live in the plane normal to the axis will generally have some inclination with respect to the cylindrical basis, by virtue of the axis being non-planar. Hence, a cut in the laboratory frame introduces an additional projection.

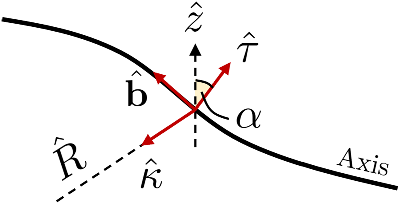

Figure 2. Definition of the slant angle

![]() $\alpha$

. Diagram showing the definition of the angle

$\alpha$

. Diagram showing the definition of the angle

![]() $\alpha$

measuring the inclination of the magnetic axis at the origin (

$\alpha$

measuring the inclination of the magnetic axis at the origin (

![]() $\phi =0$

) with the ‘laboratory’ cylindrical coordinate system. The symbols have their usual meaning.

$\phi =0$

) with the ‘laboratory’ cylindrical coordinate system. The symbols have their usual meaning.

Take as an illustrating example the cross-section at a stellarator-symmetric point (Dewar & Hudson Reference Dewar and Hudson1998), which corresponds to an up–down-symmetric ellipse in the plane normal to the magnetic axis. Because under the map

![]() $(\phi ,\theta )\rightarrow (-\phi ,-\theta )$

it must be the case that

$(\phi ,\theta )\rightarrow (-\phi ,-\theta )$

it must be the case that

![]() $R,Z\rightarrow R,-Z$

, it follows that

$R,Z\rightarrow R,-Z$

, it follows that

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $Z$

must be even and odd functions, respectively. In particular, this means that

$Z$

must be even and odd functions, respectively. In particular, this means that

![]() $\partial _\phi R_0=0=\partial _\phi ^2 Z_0$

at

$\partial _\phi R_0=0=\partial _\phi ^2 Z_0$

at

![]() $\phi =0$

. Define a slant angle

$\phi =0$

. Define a slant angle

![]() $\alpha$

as the angle that the plane normal to the magnetic axis makes with respect to the cylindrical toroidal angle; i.e. the magnetic axis is rotated about

$\alpha$

as the angle that the plane normal to the magnetic axis makes with respect to the cylindrical toroidal angle; i.e. the magnetic axis is rotated about

![]() $\hat {R}$

by an angle

$\hat {R}$

by an angle

![]() $\alpha$

(see figure 2). Then we may write the components of

$\alpha$

(see figure 2). Then we may write the components of

![]() $\hat {\boldsymbol \tau }$

as

$\hat {\boldsymbol \tau }$

as

![]() $\tau ^z=\cos \alpha$

and

$\tau ^z=\cos \alpha$

and

![]() $\tau ^\phi =\sin \alpha$

, and because of the symmetry,

$\tau ^\phi =\sin \alpha$

, and because of the symmetry,

![]() $\hat {\kappa }=-\hat {R}$

. The transformation in (3.6) and (3.7) then reduces to a scaling of the ellipse in the binormal (

$\hat {\kappa }=-\hat {R}$

. The transformation in (3.6) and (3.7) then reduces to a scaling of the ellipse in the binormal (

![]() $Y$

) direction

$Y$

) direction

\begin{align} \bar {Y}_1=Y_{1}\bigg (\tau ^z-\underbrace {\frac {\partial _\phi Z_0}{R_0}}_{-\tau ^\phi /\tau ^z}\tau ^\phi \bigg )=\frac {Y_{1}}{\cos \alpha }. \end{align}

\begin{align} \bar {Y}_1=Y_{1}\bigg (\tau ^z-\underbrace {\frac {\partial _\phi Z_0}{R_0}}_{-\tau ^\phi /\tau ^z}\tau ^\phi \bigg )=\frac {Y_{1}}{\cos \alpha }. \end{align}

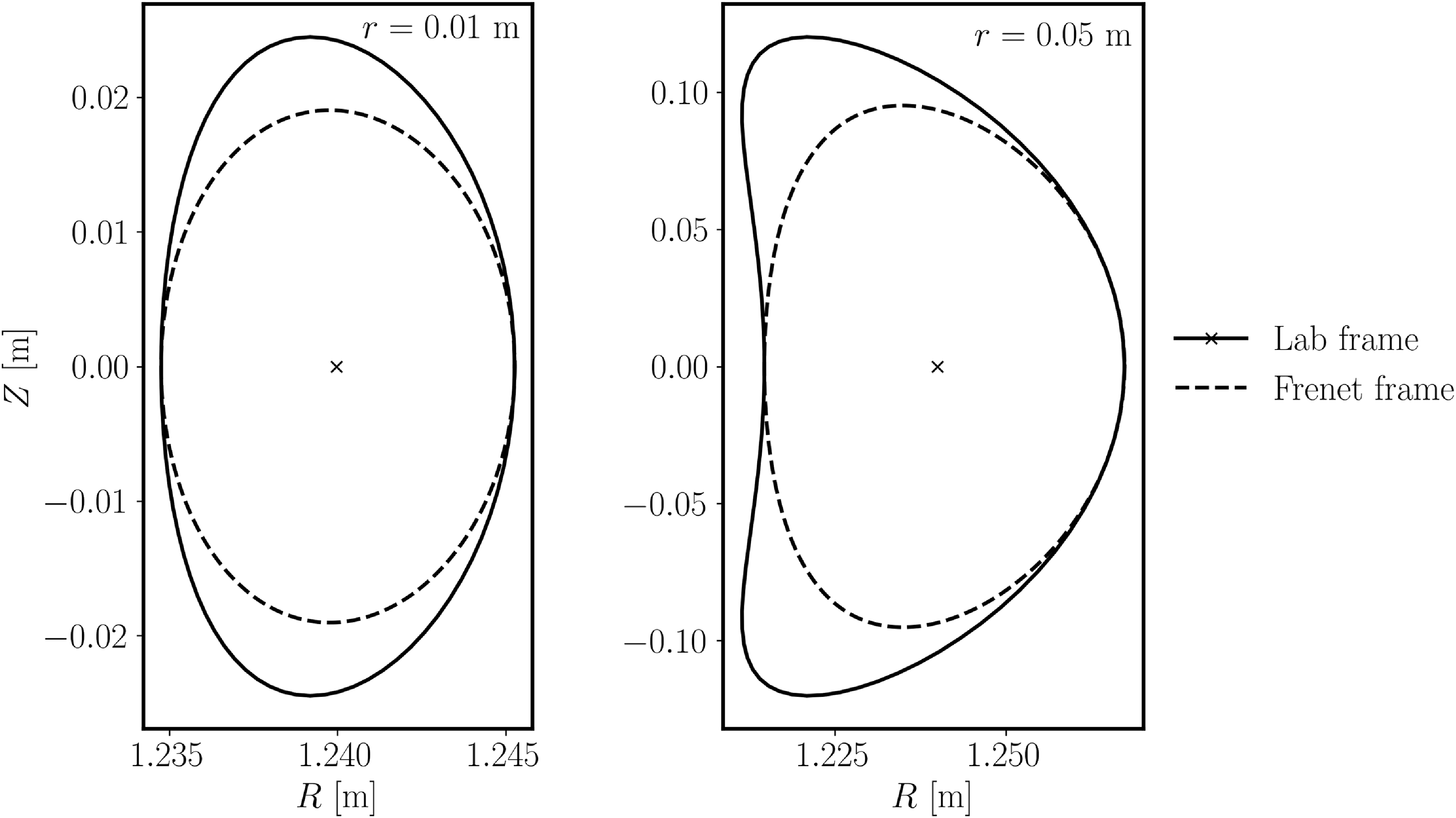

Due to the inclination of the axis, the ellipticity of the cross-section changes (see an example in figure 3), becoming stretched in the binormal direction. Away from this point of stellarator symmetry, the axis also presents an inclination with respect to the radial coordinate, leading to an additional reshaping of the elliptical shape.

Figure 3. Geometric deformation of cross-sections from the near-axis to the laboratory frame. Example of the change in the cross-sections due to the geometric effects of going from the frame of the axis (broken lines) to the laboratory frame (solid line). These correspond to the cross-sections of the ‘precise QH’ stellarator configuration from Landreman & Paul (Reference Landreman and Paul2022) at one of its stellarator-symmetric points. The left corresponds to the cross-section evaluated at

![]() $r=0.01$

, while the shape to the right is at

$r=0.01$

, while the shape to the right is at

![]() $r=0.05$

. The shape to the left shows the enhancement of elongation in the vertical direction due to the inclination of the axis, and the right the change of triangularity but immutability of the centre of the cross-section.

$r=0.05$

. The shape to the left shows the enhancement of elongation in the vertical direction due to the inclination of the axis, and the right the change of triangularity but immutability of the centre of the cross-section.

3.3. Second order: triangular surfaces

The same approach detailed in the previous section for the first order can be extended to higher orders following the same geometric construction as that in figure 1. The details of how to proceed to second order are presented in Appendix E. Second order is perhaps the highest order of interest, given that near-axis constructions are hardly performed beyond it (Garren & Boozer Reference Garren and Boozer1991a ; Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019; Rodríguez et al. Reference Rodríguez, Plunk and Jorge2025).

The derivation at second order proceeds by writing

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}=\boldsymbol{r}_0+\rho \boldsymbol{x}_1+\rho ^2\boldsymbol{x}_2$

, where

$\boldsymbol{x}=\boldsymbol{r}_0+\rho \boldsymbol{x}_1+\rho ^2\boldsymbol{x}_2$

, where

![]() $\boldsymbol{x}_2=X_2\hat {\boldsymbol \kappa }+Y_2\hat {\boldsymbol \tau }+Z_2\hat {\boldsymbol{t}}$

. Using the same considerations as in figure 1

$\boldsymbol{x}_2=X_2\hat {\boldsymbol \kappa }+Y_2\hat {\boldsymbol \tau }+Z_2\hat {\boldsymbol{t}}$

. Using the same considerations as in figure 1

\begin{align} R_2 & =-\frac {1}{2}\partial _\phi ^2R_0\left (\frac {x_1^\phi }{R_0}\right )^2-\left (\frac {x_2^\phi }{R_0}-\frac {x_1^Rx_1^\phi }{R_0^2}\right )\partial _\phi R_0\nonumber \\[5pt]& \quad -\frac {x_1^\phi }{R_0}\partial _\phi \left (x_1^R-\frac {x_1^\phi }{R_0}\partial _\phi R_0\right ) +\left (x_2^R+\frac {(x_1^\phi )^2}{2R_0}\right )\!,\\[-5pt]\nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} R_2 & =-\frac {1}{2}\partial _\phi ^2R_0\left (\frac {x_1^\phi }{R_0}\right )^2-\left (\frac {x_2^\phi }{R_0}-\frac {x_1^Rx_1^\phi }{R_0^2}\right )\partial _\phi R_0\nonumber \\[5pt]& \quad -\frac {x_1^\phi }{R_0}\partial _\phi \left (x_1^R-\frac {x_1^\phi }{R_0}\partial _\phi R_0\right ) +\left (x_2^R+\frac {(x_1^\phi )^2}{2R_0}\right )\!,\\[-5pt]\nonumber \end{align}

\begin{align} Z_2 &=-\frac {1}{2}\partial _\phi ^2 Z_0\left (\frac {x_1^\phi }{R_0}\right )^2-\left (\frac {x_2^\phi }{R_0}-\frac {x_1^Rx_1^\phi }{R_0^2}\right )\partial _\phi Z_0-\frac {x_1^\phi }{R_0}\partial _\phi \left ( x_1^z-\frac {x_1^{\phi }}{R_0}\partial _\phi Z_0\right )+x_2^z,\end{align}

\begin{align} Z_2 &=-\frac {1}{2}\partial _\phi ^2 Z_0\left (\frac {x_1^\phi }{R_0}\right )^2-\left (\frac {x_2^\phi }{R_0}-\frac {x_1^Rx_1^\phi }{R_0^2}\right )\partial _\phi Z_0-\frac {x_1^\phi }{R_0}\partial _\phi \left ( x_1^z-\frac {x_1^{\phi }}{R_0}\partial _\phi Z_0\right )+x_2^z,\end{align}

where we may express their poloidal harmonic content

![]() $R_2=R_{2,0}+R_2^c\cos 2\theta +R_2^s\sin 2\theta$

(and similarly for

$R_2=R_{2,0}+R_2^c\cos 2\theta +R_2^s\sin 2\theta$

(and similarly for

![]() $Z$

) by appropriate use of multiple angle formulae. Note that the complexity has significantly increased in going to higher order, which will tend to make higher harmonic toroidal content proliferate.

$Z$

) by appropriate use of multiple angle formulae. Note that the complexity has significantly increased in going to higher order, which will tend to make higher harmonic toroidal content proliferate.

Once we have these geometric transformations, we may then impose them as constraints on the Zernike basis, by simply considering the general expression in (2.13) to write

\begin{align} f_{2,0}^{\mathrm{NAE}}=-\left (\frac {\rho }{r}\right )^2\sum _{k=1}^\infty (-1)^kk(k+1)f_{2k,0}, \end{align}

\begin{align} f_{2,0}^{\mathrm{NAE}}=-\left (\frac {\rho }{r}\right )^2\sum _{k=1}^\infty (-1)^kk(k+1)f_{2k,0}, \end{align}

\begin{align} f_{2,\pm 2}^{\mathrm{NAE}}=-\left (\frac {\rho }{r}\right )^2\frac {1}{2}\sum _{k=1}^\infty (-1)^kk(k+1)f_{2k,\pm 2}, \end{align}

\begin{align} f_{2,\pm 2}^{\mathrm{NAE}}=-\left (\frac {\rho }{r}\right )^2\frac {1}{2}\sum _{k=1}^\infty (-1)^kk(k+1)f_{2k,\pm 2}, \end{align}

where the latter corresponds to the cosine piece for the + sign and the sine for −.

3.3.1. Interpretation of the second-order transformation

To illustrate the geometric meaning of this transformation, let us consider again the shape of the cross-section at the stellarator-symmetric point. At second order, the cross-section gains shaping beyond ellipticity (Landreman Reference Landreman2021; Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2023). First, it acquires some level of triangularity,

![]() $\delta$

, a measure of left–right asymmetry of the cross-section, defined as the distance between the vertical turning points of the cross-section with respect to the centre along the symmetry line of the cross-section. In the near-axis description

$\delta$

, a measure of left–right asymmetry of the cross-section, defined as the distance between the vertical turning points of the cross-section with respect to the centre along the symmetry line of the cross-section. In the near-axis description

where

![]() $Y$

and

$Y$

and

![]() $X$

are along the normal and binormal, but an equivalent definition could be adapted to the shape with respect to the laboratory frame, with

$X$

are along the normal and binormal, but an equivalent definition could be adapted to the shape with respect to the laboratory frame, with

![]() $Z$

instead of

$Z$

instead of

![]() $Y$

and

$Y$

and

![]() $R$

instead of

$R$

instead of

![]() $X$

.

$X$

.

The other important ingredient is the Shafranov shift, the relative displacement of the centres of the cross-sections from one surface to the next. Following Rodríguez (Reference Rodríguez2023), in the normal direction (in this case the radial one as well)

The transformations in (3.12a ) and (3.12b ) for the stellarator-symmetric cross-section read

where

![]() $\tilde {\tau }=1/\tau ^z$

and

$\tilde {\tau }=1/\tau ^z$

and

![]() $\varLambda =Y_{1s}^2\tau ^\phi [R_0(\tau ^\phi -2\tau _R')+\tau ^zR_0'']/4R_0^2$

. From the top equation, we may read the Shafranov shift

$\varLambda =Y_{1s}^2\tau ^\phi [R_0(\tau ^\phi -2\tau _R')+\tau ^zR_0'']/4R_0^2$

. From the top equation, we may read the Shafranov shift

![]() $\Delta _R$

, which the transformation leaves unchanged, i.e.

$\Delta _R$

, which the transformation leaves unchanged, i.e.

![]() $\Delta _X=\Delta _R$

. The triangularity, however, does change (see Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2024) provided

$\Delta _X=\Delta _R$

. The triangularity, however, does change (see Rodríguez Reference Rodríguez2024) provided

![]() $\alpha \neq 0$

and there is a rotation of the elliptical cross-section about the axis and across the stellarator-symmetric point. An example of this is illustrated in figure 3. There is as a result an offset in the value of triangularity when going from the axis to the laboratory frame. However, changing triangularity in the Frenet frame at second order directly affects triangularity in the laboratory frame linearly.

$\alpha \neq 0$

and there is a rotation of the elliptical cross-section about the axis and across the stellarator-symmetric point. An example of this is illustrated in figure 3. There is as a result an offset in the value of triangularity when going from the axis to the laboratory frame. However, changing triangularity in the Frenet frame at second order directly affects triangularity in the laboratory frame linearly.

4. Implementation of near-axis constraints

From the previous section, we know the constraints the Fourier–Zernike coefficients representing the equilibrium in DESC must be subject to in order to match a prescribed near-axis behaviour. We now detail how such constraints are enforced during an equilibrium solve. To do so, we must start by being more precise with how DESC treats the typical fixed-boundary equilibrium problem. Using the Fourier–Zernike coefficients

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}=(R_{lmn}, Z_{lmn}, \lambda _{lmn})$

as degrees of freedom, it treats the problem as a constrained optimisation problem in which the cost function is the MHS force balance error, (2.7),

$\boldsymbol{y}=(R_{lmn}, Z_{lmn}, \lambda _{lmn})$

as degrees of freedom, it treats the problem as a constrained optimisation problem in which the cost function is the MHS force balance error, (2.7),

subject to some imposed linear constraints

![]() $\boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{y} = \boldsymbol{b}$

. Let us take

$\boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{y} = \boldsymbol{b}$

. Let us take

![]() $N_c$

to be the number of coefficients,

$N_c$

to be the number of coefficients,

![]() $M_c$

the number of truly independent constraints and take the function

$M_c$

the number of truly independent constraints and take the function

![]() $\boldsymbol{F}$

to be evaluated on a

$\boldsymbol{F}$

to be evaluated on a

![]() $\{\rho ,\theta ,\phi \}$

grid.

$\{\rho ,\theta ,\phi \}$

grid.

Depending on the chosen constraints, the equilibrium problem solved addresses different formulations of the problem (Conlin et al. Reference Conlin, Kim, Dudt, Panici and Kolemen2024). In the traditional fixed-boundary formulation, one constrains linear combinations of

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $Z$

coefficients to match the shape of a boundary at

$Z$

coefficients to match the shape of a boundary at

![]() $\rho =1$

. In the near-axis scenario, we constrain a different combination of coefficients to enforce a particular form of the solution near the axis, as described in the previous sections. Once the linear

$\rho =1$

. In the near-axis scenario, we constrain a different combination of coefficients to enforce a particular form of the solution near the axis, as described in the previous sections. Once the linear

![]() $M_c\times N_c$

constraint matrix

$M_c\times N_c$

constraint matrix

![]() $\boldsymbol{A}$

is in place, a

$\boldsymbol{A}$

is in place, a

![]() $N_c\times (N_c-M_c)$

auxiliary matrix

$N_c\times (N_c-M_c)$

auxiliary matrix

![]() $\boldsymbol{Z}$

is defined such that

$\boldsymbol{Z}$

is defined such that

![]() $\boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{Z}\boldsymbol{v}=0\,\forall \,\boldsymbol{v}\in \mathbb{R}^{N_c-M_c}$

. Any coefficient vector

$\boldsymbol{A} \boldsymbol{Z}\boldsymbol{v}=0\,\forall \,\boldsymbol{v}\in \mathbb{R}^{N_c-M_c}$

. Any coefficient vector

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}$

that satisfies the constraint may then be written as

$\boldsymbol{y}$

that satisfies the constraint may then be written as

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}_{\mathrm{opt}} = \boldsymbol{y}_p +\boldsymbol{Z}\boldsymbol{v}$

, where

$\boldsymbol{y}_{\mathrm{opt}} = \boldsymbol{y}_p +\boldsymbol{Z}\boldsymbol{v}$

, where

![]() $\boldsymbol{y}_p$

is a particular solution of

$\boldsymbol{y}_p$

is a particular solution of

![]() $\boldsymbol{A}\boldsymbol{y}_p=\boldsymbol{b}$

. This way, optimisation may be performed unconstrained in the

$\boldsymbol{A}\boldsymbol{y}_p=\boldsymbol{b}$

. This way, optimisation may be performed unconstrained in the

![]() $N_c-M_c$

-dimensional space of

$N_c-M_c$

-dimensional space of

![]() $\boldsymbol{v}$

. This method is known as the feasible direction method (Nocedal & Wright Reference Nocedal and Wright1999, § 12), and is used in DESC to impose constraints.

$\boldsymbol{v}$

. This method is known as the feasible direction method (Nocedal & Wright Reference Nocedal and Wright1999, § 12), and is used in DESC to impose constraints.

We thus know how to impose the constraints within DESC. We use the pyQSC (Landreman Reference Landreman2022b

) and pyQIC (Jorge et al. Reference Jorge, Plunk, Drevlak, Landreman, Lobsien, Camacho Mata and Helander2022) codes to feed the pertinent near-axis information into (3.8) and (3.13). We shall choose to impose constraints on

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $Z$

(and potentially also

$Z$

(and potentially also

![]() $\lambda$

) to the wanted order in

$\lambda$

) to the wanted order in

![]() $\rho$

. We shall consider the implications of imposing different combinations in the following section. Alongside these near-axis constraints additional ones may also be imposed to regularise the solution, including the total enclosed toroidal flux (to limit the aspect ratio of the equilibrium), plasma pressure and net toroidal current, which we shall take to vanish for simplicity in the remainder of the text (this is in no way necessary, and the discussion below holds for arbitrary profiles).

$\rho$

. We shall consider the implications of imposing different combinations in the following section. Alongside these near-axis constraints additional ones may also be imposed to regularise the solution, including the total enclosed toroidal flux (to limit the aspect ratio of the equilibrium), plasma pressure and net toroidal current, which we shall take to vanish for simplicity in the remainder of the text (this is in no way necessary, and the discussion below holds for arbitrary profiles).

In addition to the constraints, we also use the near-axis solution to provide an initial guess of the equilibrium to DESC by evaluating the near-axis field at a finite radius (Landreman & Sengupta Reference Landreman and Sengupta2019) (appropriately translated into the Fourier–Zernike basis). As formulated, DESC is then run to solve for the NAE-constrained equilibrium, by minimising force balance under the mentioned constraints. As a final sanity check, the near-axis constraints are relaxed at a final step and the equilibrium re-solved as a fixed-surface solve. We do so to check that the resulting field is truly an equilibrium.

It is interesting to note that the NAE-constrained method imposes fewer constraints on the problem than the fixed-boundary method, thus leading the resulting equilibrium problem to be ‘under-constrained’ in this sense. The conventional fixed-boundary condition yields

![]() $2(2M+1)(2N+1)$

constraints on the problem (where

$2(2M+1)(2N+1)$

constraints on the problem (where

![]() $M$

and

$M$

and

![]() $N$

are the maximum poloidal and toroidal resolutions of the equilibrium). The near-axis constraints on

$N$

are the maximum poloidal and toroidal resolutions of the equilibrium). The near-axis constraints on

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $Z$

up to first order (i.e. including the axis and

$Z$

up to first order (i.e. including the axis and

![]() $\mathcal{O}(\rho )$

) yield only

$\mathcal{O}(\rho )$

) yield only

![]() $12N+6$

constraints, while constraining

$12N+6$

constraints, while constraining

![]() $R$

and

$R$

and

![]() $Z$

up to second order (i.e. including the axis and

$Z$

up to second order (i.e. including the axis and

![]() $\mathcal{O}(\rho )$

and

$\mathcal{O}(\rho )$

and

![]() $\mathcal{O}(\rho ^2)$

) yields only

$\mathcal{O}(\rho ^2)$

) yields only

![]() $24N+12$

constraints.Footnote

5

Clearly, for any realistic resolution (

$24N+12$

constraints.Footnote

5

Clearly, for any realistic resolution (

![]() $M=N\geqslant 2$

) the NAE-constrained problem has less constraints (and thus, more degrees of freedom) than the corresponding fixed-boundary problem. At the resolutions used in this work, the

$M=N\geqslant 2$

) the NAE-constrained problem has less constraints (and thus, more degrees of freedom) than the corresponding fixed-boundary problem. At the resolutions used in this work, the

![]() $\mathcal{O}(\rho )$

NAE constraints number

$\mathcal{O}(\rho )$

NAE constraints number

![]() ${\sim}7$

times less than the fixed boundary, while the

${\sim}7$

times less than the fixed boundary, while the

![]() $\mathcal{O}(\rho ^2)$

constraints number

$\mathcal{O}(\rho ^2)$

constraints number

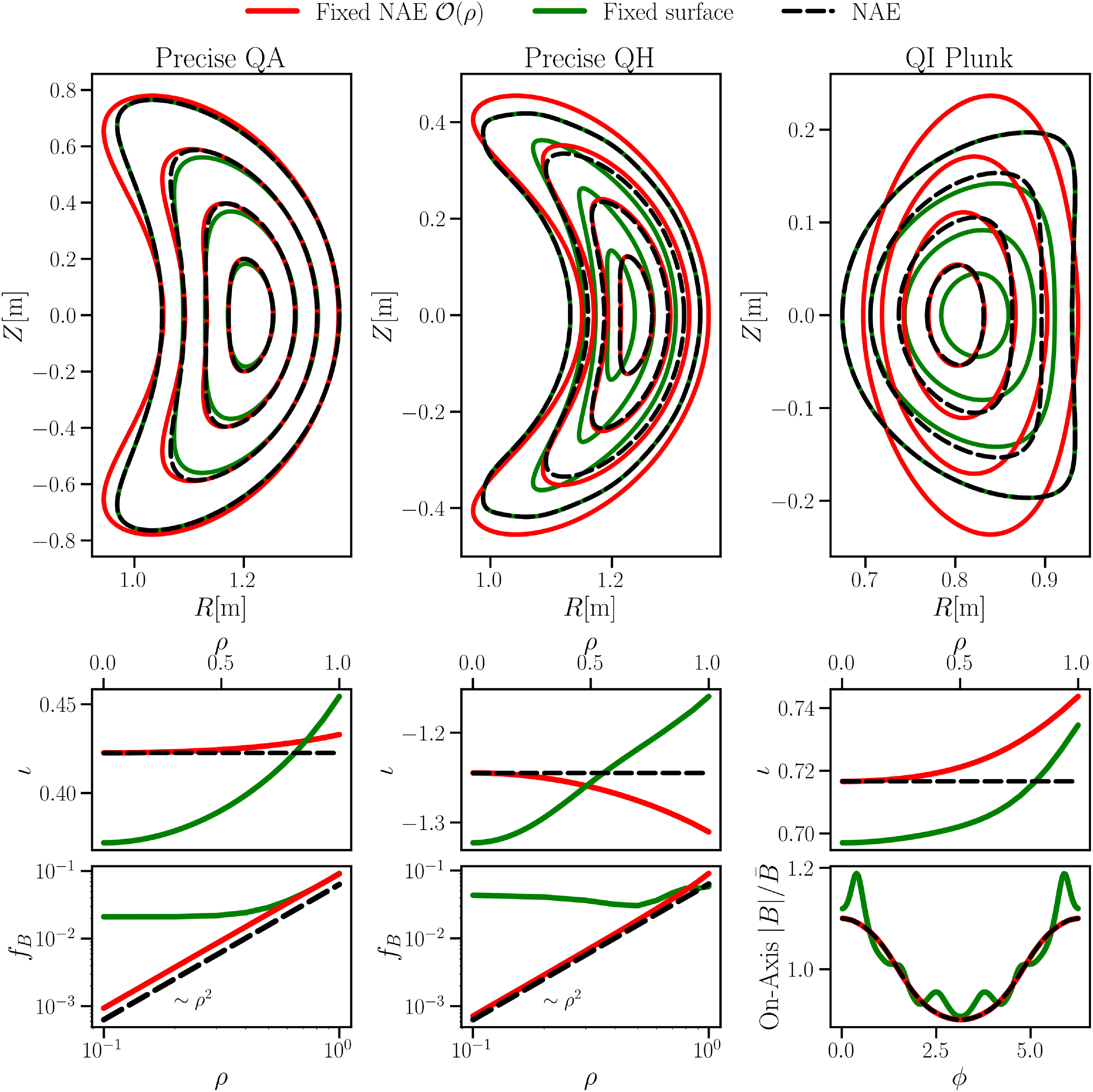

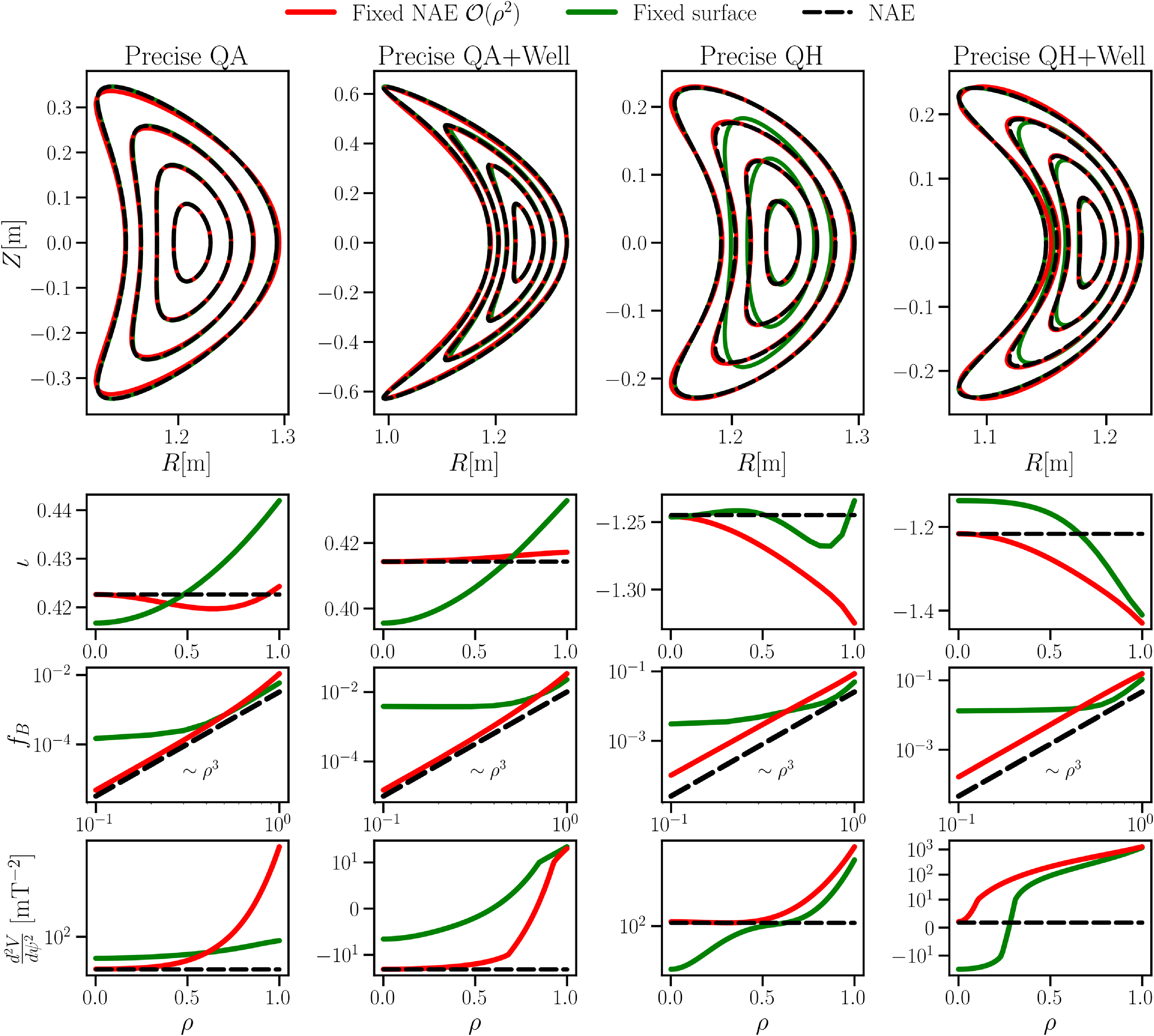

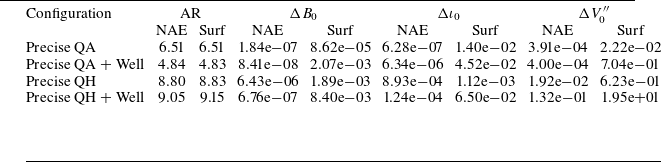

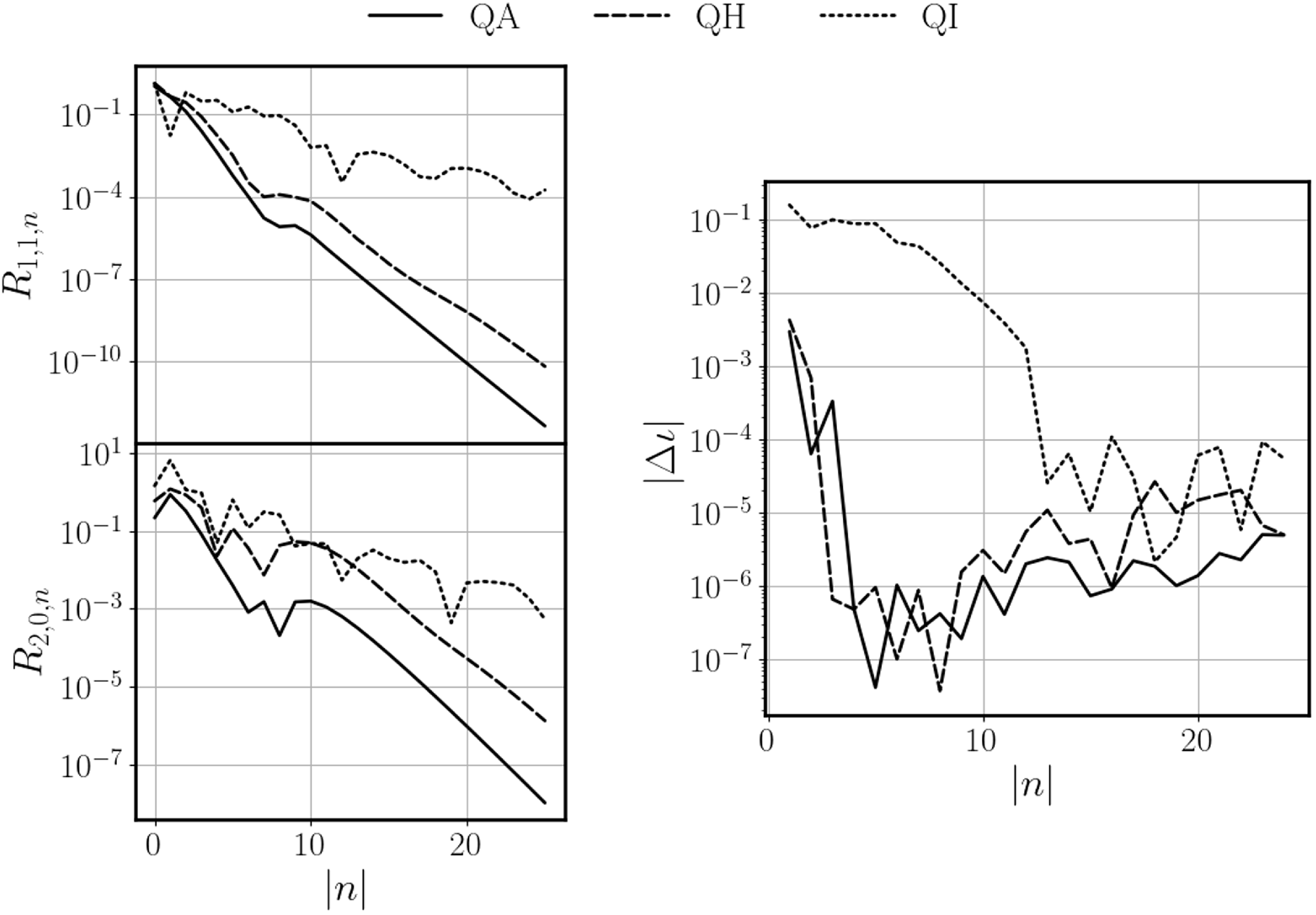

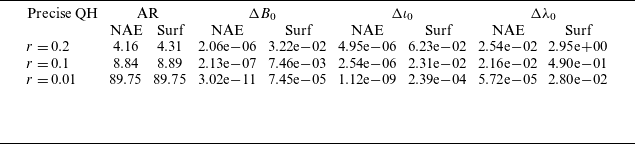

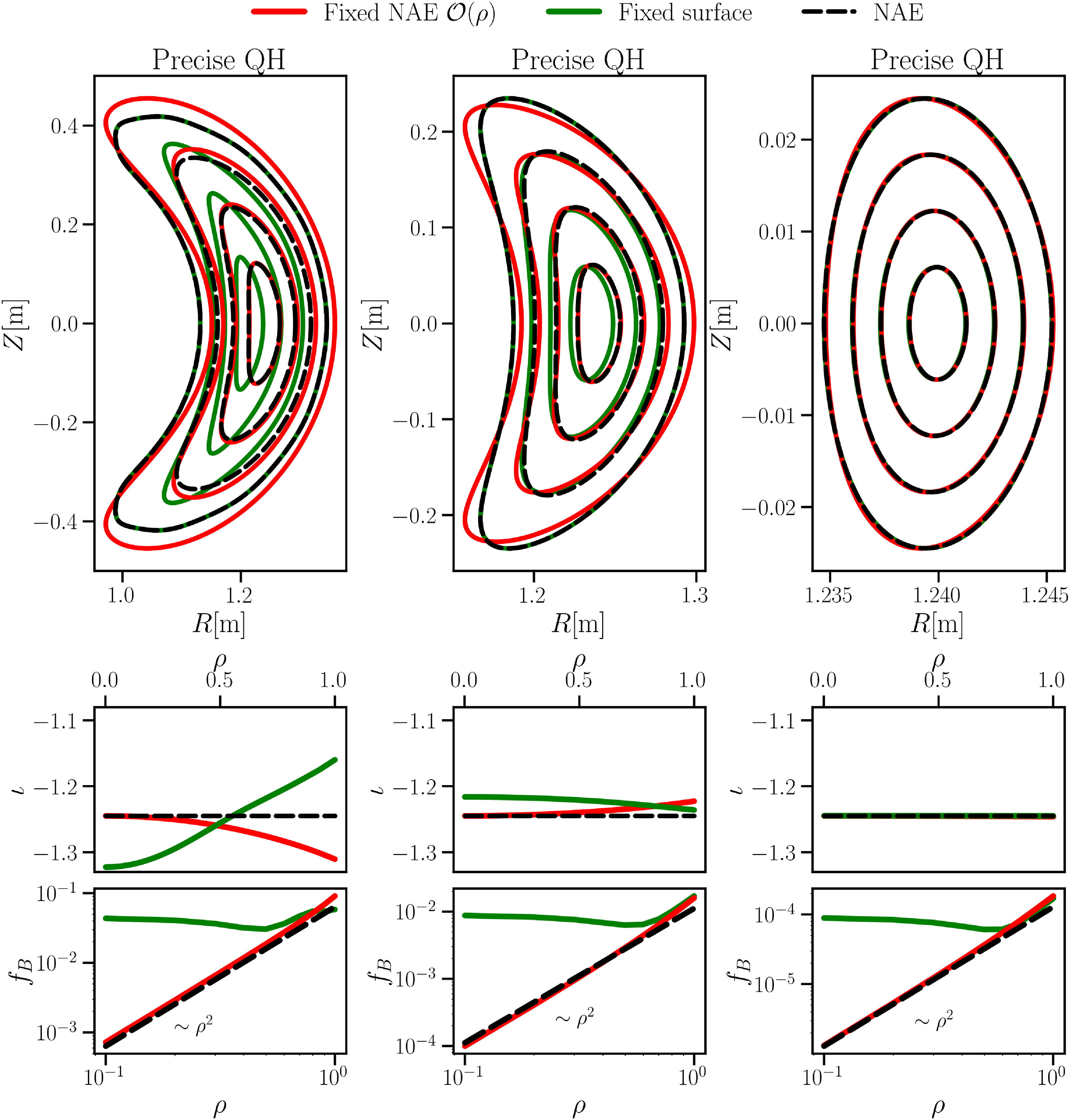

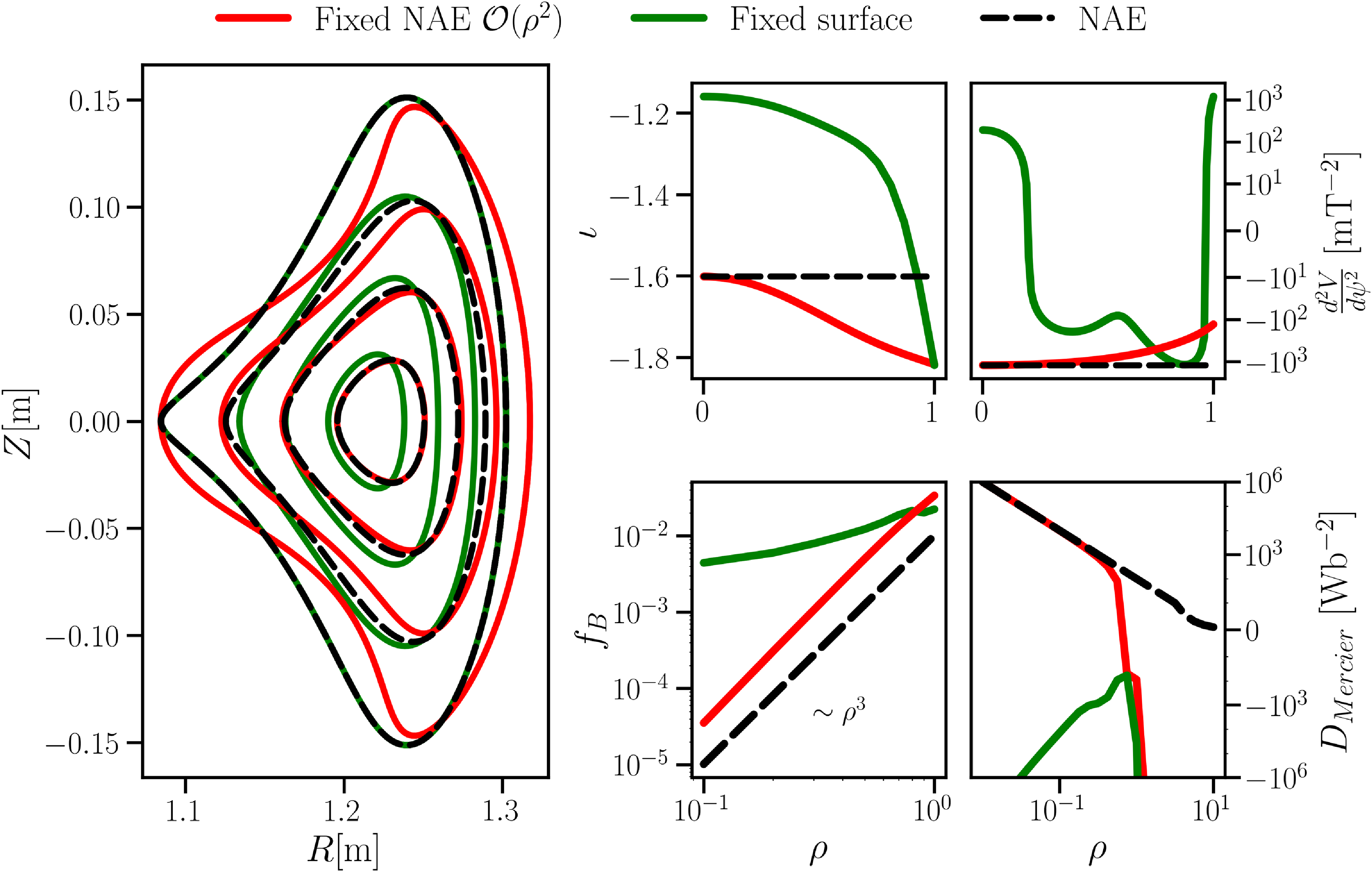

![]() ${\sim}3$