1. Introduction

The ubiquity of unsteady phenomena in nature is well-established, particularly in the context of the accelerating motion of organisms within fluid environments. These organisms, such as flyers and swimmers, exhibit behaviours characterized by the acceleration and morphing of wings, fins and bodies (Mountcastle & Combes Reference Mountcastle and Combes2013; Lucas et al. Reference Lucas, Johnson, Beaulieu, Cathcart, Tirrell, Colin, Gemmell, Dabiri and Costello2014; Chin & Lentink Reference Chin and Lentink2016; Triantafyllou, Weymouth & Miao Reference Triantafyllou, Weymouth and Miao2016) and, particularly, morphing provides additional benefits. For example, insects enhance their flapping efficiency through the passive deformation of their wings (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Nassef, Pornsinsirirak, Tai and Ho2003; Kang et al. Reference Kang, Aono, Cesnik and Shyy2011; Kang & Shyy Reference Kang and Shyy2013), birds coordinate flight efficiency (Johansson, Wolf & Hedenström Reference Johansson, Wolf and Hedenström2010; Taylor et al. Reference Taylor, Carruthers, Hubel and Walker2012) and disturbance resistance (Reynolds, Thomas & Taylor Reference Reynolds, Thomas and Taylor2014; Harvey et al. Reference Harvey, Baliga, Lavoie and Altshuler2019; Cheney et al. Reference Cheney, Stevenson, Durston, Song, Usherwood, Bomphrey and Windsor2020) through active wing morphing, and marine swimmers utilize fin flexibility to enhance propulsion efficiency or to gain high acceleration during manoeuvres (Triantafyllou et al. Reference Triantafyllou, Weymouth and Miao2016; Hang et al. Reference Hang, Heydari, Costello and Kanso2022; Jimenez et al. Reference Jimenez, Lucas, Long and Tytell2023). Direct simulations or experiments provide detailed insights into these phenomena; however, due to the inherent complexity of modelling, the generality of the derived fluid dynamic laws remains limited (Ho et al. Reference Ho, Nassef, Pornsinsirirak, Tai and Ho2003; Kang et al. Reference Kang, Aono, Cesnik and Shyy2011; Ramananarivo, Godoy-Diana & Thiria Reference Ramananarivo, Godoy-Diana and Thiria2011; Kang & Shyy Reference Kang and Shyy2013). Therefore, researchers tend to abstract moving appendages as plates in model problems to reveal universal fluid dynamic laws (Kim & Gharib Reference Kim and Gharib2011b ; Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016b ; Reijtenbagh et al. Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023a ; Li et al. Reference Li, Chen, Xiang, Liu and Wang2024).

Considering that any unsteady motion (neglecting rotation) can be approximated by superposing small intervals of uniformly accelerated motions (Kaiser, Kriegseis & Rival Reference Kaiser, Kriegseis and Rival2020; Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022) and reconfigurable plates abstract the geometry of wings and fins (Kim & Gharib Reference Kim and Gharib2011a , Reference Kim and Gharibb ), accelerating reconfigurable circular plates, which incorporate both acceleration and shape deformation, are adopted as a fundamental model to investigate the unsteady fluid-dynamic forces and flow field for biological propulsion and disturbance resistance.

The influence of acceleration on the force evolution of rigid circular plates is first discussed, which has been extensively investigated (Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016b

; Reijtenbagh et al. Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023a

; Li et al. Reference Li, Chen, Xiang, Liu and Wang2024). The force evolution exhibits a distinct ‘peak-and-valley’ pattern: during the acceleration process, the force increases with velocity, peaks at the end of acceleration and then gradually decreases to a valley as acceleration ceases, before slowly rising until stabilizing. The instantaneous force decreasing to a minimum before increasing again to reach a steady value is known as the ‘drag trough’ phenomenon (Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016a

). Two dynamic parameters govern the force scaling for such plates: the Reynolds number,

![]() $ Re = \rho _{\!f} U_c D/\mu$

, and the acceleration number,

$ Re = \rho _{\!f} U_c D/\mu$

, and the acceleration number,

![]() $ a^* = a D/U_c^2$

, where

$ a^* = a D/U_c^2$

, where

![]() $ D$

,

$ D$

,

![]() $ a$

and

$ a$

and

![]() $ U_c$

are the characteristic length, acceleration and velocity of the translating plate, respectively, and

$ U_c$

are the characteristic length, acceleration and velocity of the translating plate, respectively, and

![]() $ \rho _{\!f}$

and

$ \rho _{\!f}$

and

![]() $ \mu$

are the density and dynamic viscosity of the fluid. For rigid circular plates, the force evolution exhibits Reynolds number independence within the range of

$ \mu$

are the density and dynamic viscosity of the fluid. For rigid circular plates, the force evolution exhibits Reynolds number independence within the range of

![]() $ 50\,000 \leqslant Re \leqslant 350\,000$

when the dimensionless travel distance is less than

$ 50\,000 \leqslant Re \leqslant 350\,000$

when the dimensionless travel distance is less than

![]() $6$

(Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016b

). Additionally, an

$6$

(Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016b

). Additionally, an

![]() $ a^*$

dependence exists, indicating that for the same

$ a^*$

dependence exists, indicating that for the same

![]() $ a^*$

conditions, the instantaneous force evolution follows a consistent pattern regardless of variations in actual characteristic acceleration

$ a^*$

conditions, the instantaneous force evolution follows a consistent pattern regardless of variations in actual characteristic acceleration

![]() $ a$

and velocity

$ a$

and velocity

![]() $ U_c$

(Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016b

; Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022).

$ U_c$

(Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016b

; Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022).

Two perspectives are commonly used to explain the unsteady mechanisms of force generation during the acceleration of a rigid flat plate from rest: the quasisteady view (Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016a , Reference Fernando and Rivalb ; Reijtenbagh et al. Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023a ; Liu & Sun Reference Liu and Sun2024; Li et al. Reference Li, Chen, Xiang, Liu and Wang2024) and the impulse-based view (Kim & Gharib Reference Kim and Gharib2011a ; Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022). The quasisteady view, which is primarily focused on predictive modelling, decomposes the instantaneous force into a steady-state force, added-mass force and history force (Stokes Reference Stokes1851; Basset Reference Basset1888; Oseen Reference Oseen1927; Odar & Hamilton Reference Odar and Hamilton1964). While powerful, accurately modelling these terms in viscous, separated flows is challenging, as simple potential-flow models often fail (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019; Fernando, Weymouth & Rival Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020; Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022). This has led to an ongoing debate about the best approach: some researchers propose a variable added-mass coefficient to account for real fluid effects (Odar & Hamilton Reference Odar and Hamilton1964; McPhaden & Rival Reference McPhaden and Rival2018; Galler, Weymouth & Rival Reference Galler, Weymouth and Rival2021), while others introduce a complex history force term to capture the history of the wake, with recent work proposing new scaling laws based on this concept (Reijtenbagh et al. Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023a ; Li et al. Reference Li, Chen, Xiang, Liu and Wang2024). In contrast, the impulse-based perspective offers a more direct link to the physical mechanisms by focusing on the evolution of the vorticity field, particularly through the vorticity moment theorem (Wu Reference Wu1981; Graham et al. Reference Graham, Pitt Ford and Babinsky2017; Kaiser et al. Reference Kaiser, Kriegseis and Rival2020). This approach posits that the force is governed by the growth of vorticity, which can be conceptually separated into added-mass vorticity and the shed vorticity that forms the wake (Corkery Reference Corkery2019). The dynamics of this shed vorticity, typically modelled as a growing vortex ring, are considered central to explaining the force history. For instance, the phenomenon of Reynolds number independence has been linked to the timing of vortex ring pinch-off (Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016b ), and recent models have successfully predicted instantaneous forces by tracking the details of vortex ring growth (Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022; Reijtenbagh et al. Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023a ). In essence, while the quasisteady framework provides a structure for force prediction, the impulse-based view excels at providing a mechanistic explanation rooted in the observable dynamics of the wake.

Another key characteristic of accelerating reconfigurable circular plates is reconfiguration. As a standard model for morphing problems, the study of reconfigurable flat plates has previously focused primarily on steady-state conditions, where the free stream velocity is kept constant. A well-known initial study in this area is Vogel’s work (Vogel Reference Vogel1989), in which he measured the drag of leaves in a steady wind field as a function of wind speed and found that, contrary to the commonly assumed quadratic force-speed relationship, deformable leaves exhibit a power law with an exponent of

![]() $4/3$

in the relationship between force and wind speed. This phenomenon inspired a series of subsequent studies, particularly scaling analyses of the exponent (De Langre Reference De Langre2008). Notable works include Alben et al. (Reference Alben, Shelley and Zhang2002, Reference Alben, Shelley and Zhang2004), who used soap film experiments in two-dimensional (2-D) flow fields to measure one-dimensional (1-D) fibres, modelled based on beam theory, and defined a dimensionless length that physically represents the ratio of fluid dynamics to elastic force. Schouveiler & Boudaoud (Reference Schouveiler and Boudaoud2006) investigated the plate reconfiguration based on cone shapes, Gosselin et al. (Reference Gosselin, De Langre and Machado-Almeida2010) analysed rectangular plates and, more recently, Baskaran, Hutin & Mulleners (Reference Baskaran, Hutin and Mulleners2023) studied bioinspired flexible disks, each discovering similar power law phenomena. However, in all these configurations, force decreases compared with rigid plates due to deformation-induced area reduction and streamlining (Gosselin et al. Reference Gosselin, De Langre and Machado-Almeida2010; Baskaran et al. Reference Baskaran, Hutin and Mulleners2023).

$4/3$

in the relationship between force and wind speed. This phenomenon inspired a series of subsequent studies, particularly scaling analyses of the exponent (De Langre Reference De Langre2008). Notable works include Alben et al. (Reference Alben, Shelley and Zhang2002, Reference Alben, Shelley and Zhang2004), who used soap film experiments in two-dimensional (2-D) flow fields to measure one-dimensional (1-D) fibres, modelled based on beam theory, and defined a dimensionless length that physically represents the ratio of fluid dynamics to elastic force. Schouveiler & Boudaoud (Reference Schouveiler and Boudaoud2006) investigated the plate reconfiguration based on cone shapes, Gosselin et al. (Reference Gosselin, De Langre and Machado-Almeida2010) analysed rectangular plates and, more recently, Baskaran, Hutin & Mulleners (Reference Baskaran, Hutin and Mulleners2023) studied bioinspired flexible disks, each discovering similar power law phenomena. However, in all these configurations, force decreases compared with rigid plates due to deformation-induced area reduction and streamlining (Gosselin et al. Reference Gosselin, De Langre and Machado-Almeida2010; Baskaran et al. Reference Baskaran, Hutin and Mulleners2023).

Thus, an important question arises: Is the force exerted by an accelerating reconfigurable circular plate smaller than that of a rigid plate? If so, how can previous studies justify the benefits of flexibility in enhancing propulsion and manoeuvrability? If not, what is the underlying flow mechanism responsible for the force enhancement? Limited studies in this area include Kim & Gharib (Reference Kim and Gharib2011b ), who observed that a flexible plate generates lower forces after acceleration compared with a rigid plate but larger forces after the initial peak, attributing this behaviour to the slow development of the vortex structure. And, Joshi & Bhattacharya (Reference Joshi and Bhattacharya2022) investigated the unsteady force response of an accelerating flat plate with controlled spanwise bending and found that unsteady drag increased when the plate bent towards the incoming flow, as the growth of circulation was faster and the tip vortices remained closer to the plate during the bend-down motion. Nevertheless, while the hydrodynamics of rigid accelerating bodies (Lorite-Díez et al. Reference Lorite-Díez, Jiménez-González, Gutiérrez-Montes and Martínez-Bazán2018; Reijtenbagh et al. Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023a ; Liu & Sun Reference Liu and Sun2024) and flexible bodies in steady flow (Vogel Reference Vogel1989; Alben, Shelley & Zhang Reference Alben, Shelley and Zhang2002; Schouveiler & Eloy Reference Schouveiler and Eloy2013; Baskaran et al. Reference Baskaran, Hutin and Mulleners2023) are increasingly understood, a systematic understanding of the governing dimensionless parameters and the key flow mechanisms for passive reconfiguration, accelerating bodies remains elusive. This motivates a deeper investigation, particularly one that leverages an impulse-based view to connect the force evolution directly to the underlying vortex dynamics.

The purpose of this study is thus to investigate the temporal evolution of force to analyse dimensionless number dependence and explore the underlying mechanism using a vortex-based low-order force model within the Reynolds number range

![]() $ 3.12\times 10^4 \leqslant Re \leqslant 10.8\times 10^4$

and bending stiffness range

$ 3.12\times 10^4 \leqslant Re \leqslant 10.8\times 10^4$

and bending stiffness range

![]() $ 4.19\times 10^{-4} \leqslant EI \leqslant 26.8$

N m (defined in § 2.2). A high-resolution force transducer and time-resolved particle image velocimetry (PIV) are the primary research methods. The article is organized as follows: § 2 introduces the experimental methods; § 3 presents the force evolution laws; § 4 discusses the flow patterns; § 5 examines the mechanisms behind the force evolution. Concluding remarks are provided in § 6.

$ 4.19\times 10^{-4} \leqslant EI \leqslant 26.8$

N m (defined in § 2.2). A high-resolution force transducer and time-resolved particle image velocimetry (PIV) are the primary research methods. The article is organized as follows: § 2 introduces the experimental methods; § 3 presents the force evolution laws; § 4 discusses the flow patterns; § 5 examines the mechanisms behind the force evolution. Concluding remarks are provided in § 6.

2. Methods

2.1. Experimental set-up

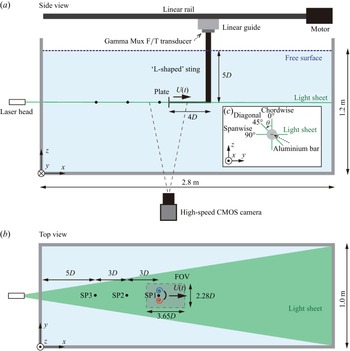

The experiments were conducted in a towing tank with a cross-sectional area of 1 m

![]() $\times$

1.3 m and a towing length of 2.8 m at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, as shown in figure 1 and also referenced in Li et al. (Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022, Reference Li, Chen, Xiang, Liu and Wang2024). The tank was filled with water (

$\times$

1.3 m and a towing length of 2.8 m at Shanghai Jiao Tong University, as shown in figure 1 and also referenced in Li et al. (Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022, Reference Li, Chen, Xiang, Liu and Wang2024). The tank was filled with water (

![]() $\rho _{\!f} = 1.0 \times 10^3$

kg m−

$\rho _{\!f} = 1.0 \times 10^3$

kg m−

![]() $^3$

) to a depth of 1.2 m. The plate with

$^3$

) to a depth of 1.2 m. The plate with

![]() $D = 0.10$

m was towed along the

$D = 0.10$

m was towed along the

![]() $x$

-axis by mounting it perpendicular to a horizontal cylindrical rod of the L-shaped sting, positioned

$x$

-axis by mounting it perpendicular to a horizontal cylindrical rod of the L-shaped sting, positioned

![]() $5D$

away from the free surface to minimize its influence (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019; Joshi & Bhattacharya Reference Joshi and Bhattacharya2022). An aluminium bar is attached to the plate through its centre to control the bending of the reconfigurable plates, resulting in symmetric deformation about the midplane. This set-up preserves left–right symmetry, mimicking the bilateral coordination seen in bird or insect wings and fish fins. The vertical strut of the sting has a streamlined,

$5D$

away from the free surface to minimize its influence (Grift et al. Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019; Joshi & Bhattacharya Reference Joshi and Bhattacharya2022). An aluminium bar is attached to the plate through its centre to control the bending of the reconfigurable plates, resulting in symmetric deformation about the midplane. This set-up preserves left–right symmetry, mimicking the bilateral coordination seen in bird or insect wings and fish fins. The vertical strut of the sting has a streamlined,

![]() $0.3D \times 0.05D$

rectangular cross-section with

$0.3D \times 0.05D$

rectangular cross-section with

![]() $0.02D$

rounded corners to minimize its wake influence. The horizontal rod, with a nominal length of

$0.02D$

rounded corners to minimize its wake influence. The horizontal rod, with a nominal length of

![]() $4D$

, has a square cross-section with a width of

$4D$

, has a square cross-section with a width of

![]() $0.1D$

and features

$0.1D$

and features

![]() $0.02D$

rounded edges to further reduce flow disturbance. The horizontal rod length was carefully selected to avoid both short and excessive lengths: a short rod length would cause the wake from the vertical part of the L-shaped sting to interfere with the vortex ring formation, while a long rod, acting as a cantilever beam, would result in strong mechanical vibrations. Further details on the influence of the L-shaped sting on the flow and force measurements are provided in Appendix A1. The motion of the plate is driven by a closed-loop stepper motor system, which consists of a stepper motor (Times Brilliant 110HCY220AL3S-TK0) and a servo driver (Just Motion Control 3HSS2208H-110). The blockage ratios for the plate (

$0.02D$

rounded edges to further reduce flow disturbance. The horizontal rod length was carefully selected to avoid both short and excessive lengths: a short rod length would cause the wake from the vertical part of the L-shaped sting to interfere with the vortex ring formation, while a long rod, acting as a cantilever beam, would result in strong mechanical vibrations. Further details on the influence of the L-shaped sting on the flow and force measurements are provided in Appendix A1. The motion of the plate is driven by a closed-loop stepper motor system, which consists of a stepper motor (Times Brilliant 110HCY220AL3S-TK0) and a servo driver (Just Motion Control 3HSS2208H-110). The blockage ratios for the plate (

![]() $0.8\,\%$

) and the L-shaped sting (

$0.8\,\%$

) and the L-shaped sting (

![]() $0.01\,\%$

) were sufficiently small to minimize wall effects (Gosselin et al. Reference Gosselin, De Langre and Machado-Almeida2010; Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016a

).

$0.01\,\%$

) were sufficiently small to minimize wall effects (Gosselin et al. Reference Gosselin, De Langre and Machado-Almeida2010; Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016a

).

Figure 1. Schematic representation of the experimental configuration. (a) Side view of the set-up, with the L-shaped sting holding the plate, moving from left to right at the set velocity

![]() $U(t)$

. The complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) cameras are positioned at the bottom, and the horizontal laser light sheet is illuminated from the left-hand side. (b) Top view illustrating the field of view (FOV) of

$U(t)$

. The complementary metal-oxide-semiconductor (CMOS) cameras are positioned at the bottom, and the horizontal laser light sheet is illuminated from the left-hand side. (b) Top view illustrating the field of view (FOV) of

![]() $3.65D \times 2.28D$

for PIV, see later in § 2.4. To measure the flow field structure corresponding to different formation times, the starting point (SP) of the plate’s motion is varied, with a spacing of

$3.65D \times 2.28D$

for PIV, see later in § 2.4. To measure the flow field structure corresponding to different formation times, the starting point (SP) of the plate’s motion is varied, with a spacing of

![]() $3D$

between SPs, and SP3 located

$3D$

between SPs, and SP3 located

![]() $5D$

from the wall. (c) A zoomed-in view of PIV. An aluminium bar is attached to the plate passing through its centre, controlling the bending. The bending direction is defined as the chordwise direction (

$5D$

from the wall. (c) A zoomed-in view of PIV. An aluminium bar is attached to the plate passing through its centre, controlling the bending. The bending direction is defined as the chordwise direction (

![]() $\theta = 0^\circ$

), the perpendicular direction as the spanwise direction (

$\theta = 0^\circ$

), the perpendicular direction as the spanwise direction (

![]() $\theta = 90^\circ$

) and the intermediate direction as the diagonal direction (

$\theta = 90^\circ$

) and the intermediate direction as the diagonal direction (

![]() $\theta = 45^\circ$

).

$\theta = 45^\circ$

).

2.2. Experimental parameters

The primary features of the accelerating reconfigurable circular plates lie in their acceleration, reconfiguration and circular geometry. Correspondingly, the key parameters include the plate’s kinematics, flexibility and shape. To simplify the problem while maintaining the focus of this study, the plate shape was fixed as a circular plate, while the kinematic and flexibility parameters were systematically varied. This section introduces the configurations of kinematic settings and flexibility parameters.

Each plate was rectilinearly accelerated from rest at a constant acceleration

![]() $ a$

to a final towing velocity

$ a$

to a final towing velocity

![]() $ U_c$

. The corresponding dimensionless kinematic parameters are the acceleration number,

$ U_c$

. The corresponding dimensionless kinematic parameters are the acceleration number,

![]() $ a^*$

, and the Reynolds number,

$ a^*$

, and the Reynolds number,

![]() $ Re$

. The kinematic set-ups in previous studies are summarized in table 1. For this study, considering the dynamic viscosity of water,

$ Re$

. The kinematic set-ups in previous studies are summarized in table 1. For this study, considering the dynamic viscosity of water,

![]() $ \mu = 1.002 \times 10^{-3} \, \mathrm{Pa \boldsymbol\,s}$

and the characteristic velocity

$ \mu = 1.002 \times 10^{-3} \, \mathrm{Pa \boldsymbol\,s}$

and the characteristic velocity

![]() $U_c$

as the maximum translating velocity of the plate, we kept

$U_c$

as the maximum translating velocity of the plate, we kept

![]() $ a^* = 0.25$

constant and varied

$ a^* = 0.25$

constant and varied

![]() $ Re$

from

$ Re$

from

![]() $ 3.12 \times 10^4$

to

$ 3.12 \times 10^4$

to

![]() $ 10.8 \times 10^4$

. To facilitate the analysis, we introduced the dimensionless travel distance, also known as the formation time (Gharib, Rambod & Shariff Reference Gharib, Rambod and Shariff1998; Yang, Jia & Yin Reference Yang, Jia and Yin2012), defined as

$ 10.8 \times 10^4$

. To facilitate the analysis, we introduced the dimensionless travel distance, also known as the formation time (Gharib, Rambod & Shariff Reference Gharib, Rambod and Shariff1998; Yang, Jia & Yin Reference Yang, Jia and Yin2012), defined as

![]() $t^* = ({1}/{D}) \int _0^t U(t) \, \mathrm{d}t$

, where

$t^* = ({1}/{D}) \int _0^t U(t) \, \mathrm{d}t$

, where

![]() $ U(t)$

is the instantaneous velocity. Formation time has been verified as a suitable parameter for describing the evolution of forces and flow fields during the acceleration phase (Kim & Gharib Reference Kim and Gharib2011b

; Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016b

; Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022; Reijtenbagh et al. Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023a

). To provide a temporal reference for the acceleration phase, we define the dimensionless acceleration time,

$ U(t)$

is the instantaneous velocity. Formation time has been verified as a suitable parameter for describing the evolution of forces and flow fields during the acceleration phase (Kim & Gharib Reference Kim and Gharib2011b

; Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016b

; Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022; Reijtenbagh et al. Reference Reijtenbagh, Tummers and Westerweel2023a

). To provide a temporal reference for the acceleration phase, we define the dimensionless acceleration time,

![]() $t_a^*$

, as the formation number at the moment acceleration ceases (

$t_a^*$

, as the formation number at the moment acceleration ceases (

![]() $t_a$

). For the constant acceleration profile used in this study,

$t_a$

). For the constant acceleration profile used in this study,

![]() $t_a^*$

simplifies to a direct function of the acceleration number,

$t_a^*$

simplifies to a direct function of the acceleration number,

![]() $a^*=aD/U_c^2$

:

$a^*=aD/U_c^2$

:

This value is reported in the captions of the relevant figures to denote the duration of the acceleration phase.

Table 1. Summary of previous investigations into the accelerating plates. Note that the shorter side of the rectangle was used as the characteristic length in Kim & Gharib (Reference Kim and Gharib2011b ), whereas the longer side was used in Reynolds et al. (Reference Reynolds, Thomas and Taylor2014) and Grift et al. (Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019).

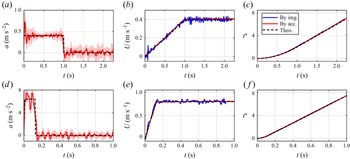

The actual kinematics were verified using two independent methods. First, a nine-axis offline accelerometer data logger (WT901SDCL) mounted on the linear guide was employed, and velocity and displacement profiles were obtained by integrating the recorded acceleration data. Second, a high-speed CMOS camera captured the positions of the plate and the L-shaped sting connection point (i.e. the centre of the circular plate) at various time instants, and differential analysis of these positions was conducted to derive the velocity. Each method was repeated 10 times to ensure reliability. A comparative analysis of the conformity between theoretical and actual velocity profiles under two distinct conditions,

![]() $ a^* = 0.25, Re = 4 \times 10^4$

and

$ a^* = 0.25, Re = 4 \times 10^4$

and

![]() $ a^* = 2.0, Re = 8 \times 10^4$

, is shown in figure 2. For measurements based on image data, displacement serves as the raw data, while velocity is derived through differentiation. However, acceleration is not further calculated by differentiation due to the typically unacceptable errors introduced by double differentiation, where Rick Chartrand’s algorithm for numerical differentiation of noisy data will be considered in future research (Chartrand Reference Chartrand2011). The uncertainty associated with the instantaneous velocity is 1.2 % for the accelerometer and 4.6 % for image acquisition under

$ a^* = 2.0, Re = 8 \times 10^4$

, is shown in figure 2. For measurements based on image data, displacement serves as the raw data, while velocity is derived through differentiation. However, acceleration is not further calculated by differentiation due to the typically unacceptable errors introduced by double differentiation, where Rick Chartrand’s algorithm for numerical differentiation of noisy data will be considered in future research (Chartrand Reference Chartrand2011). The uncertainty associated with the instantaneous velocity is 1.2 % for the accelerometer and 4.6 % for image acquisition under

![]() $ a^* = 0.25, Re = 4 \times 10^4$

, and 0.7 % and 5.3 %, respectively, under

$ a^* = 0.25, Re = 4 \times 10^4$

, and 0.7 % and 5.3 %, respectively, under

![]() $ a^* = 1.0, Re = 8 \times 10^4$

during the constant velocity stage. The larger error in the image-based measurements is attributed to more pronounced oscillations of the plate mounted at the bottom. In contrast, the accelerometer, mounted on the linear guider (as shown in figure 1), is unaffected by oscillations of the cantilever beam caused by the L-shaped sting.

$ a^* = 1.0, Re = 8 \times 10^4$

during the constant velocity stage. The larger error in the image-based measurements is attributed to more pronounced oscillations of the plate mounted at the bottom. In contrast, the accelerometer, mounted on the linear guider (as shown in figure 1), is unaffected by oscillations of the cantilever beam caused by the L-shaped sting.

Figure 2. The kinematics validation under the conditions of

![]() $ a^* = 0.25, \, Re = 4 \times 10^4$

in (a–c) and

$ a^* = 0.25, \, Re = 4 \times 10^4$

in (a–c) and

![]() $ a^* = 1.0, \, Re = 8 \times 10^4$

in (d–f) is presented. The acceleration calibration is shown in (a) and (d), the velocity calibration in (b) and (e), and the displacement calibration in (c) and (f). The black dashed lines represent the theoretical values, the red solid lines are based on accelerometer data and the blue solid lines are based on image data.

$ a^* = 1.0, \, Re = 8 \times 10^4$

in (d–f) is presented. The acceleration calibration is shown in (a) and (d), the velocity calibration in (b) and (e), and the displacement calibration in (c) and (f). The black dashed lines represent the theoretical values, the red solid lines are based on accelerometer data and the blue solid lines are based on image data.

Polycarbonate sheets are utilized to fabricate plates with varying degrees of flexibility. These sheets have a density of

![]() $ \rho _m = 1.194 \times 10^3 \, \mathrm{kg\,m^{- 3}}$

, a Young’s modulus

$ \rho _m = 1.194 \times 10^3 \, \mathrm{kg\,m^{- 3}}$

, a Young’s modulus

![]() $ E = 2220 \, \mathrm{MPa}$

, and a Poisson’s ratio

$ E = 2220 \, \mathrm{MPa}$

, and a Poisson’s ratio

![]() $ \hat {\nu } = 0.370$

. The plates differ in thickness

$ \hat {\nu } = 0.370$

. The plates differ in thickness

![]() $ h$

, and assuming 1-D deformation of a beam-type plate, the bending stiffness is calculated using the formula (Landau et al. Reference Landau, Pitaevskii, Kosevich and Lifshitz2012)

$ h$

, and assuming 1-D deformation of a beam-type plate, the bending stiffness is calculated using the formula (Landau et al. Reference Landau, Pitaevskii, Kosevich and Lifshitz2012)

The flexibility parameters are summarized in table 2. An uncertainty analysis for the bending stiffness,

![]() ${\textit{EI}}$

, was conducted. The uncertainty arises primarily from Young’s Modulus (

${\textit{EI}}$

, was conducted. The uncertainty arises primarily from Young’s Modulus (

![]() $E$

) and plate thickness (

$E$

) and plate thickness (

![]() $h$

) (2.2). A conservative relative uncertainty of

$h$

) (2.2). A conservative relative uncertainty of

![]() $\sigma _E / E = 5.0\,\%$

was adopted for

$\sigma _E / E = 5.0\,\%$

was adopted for

![]() $E$

to account for batch-to-batch variations in the commercial-grade polycarbonate (Callister & Rethwisch Reference Callister and Rethwisch1999). To quantify thickness variability, each plate was measured at 16 points in a radial and azimuthal pattern using a thickness gauge (SANLIANG 325-308, 0.001 mm resolution). The results (table 2) show excellent material uniformity, with thickness variability (

$E$

to account for batch-to-batch variations in the commercial-grade polycarbonate (Callister & Rethwisch Reference Callister and Rethwisch1999). To quantify thickness variability, each plate was measured at 16 points in a radial and azimuthal pattern using a thickness gauge (SANLIANG 325-308, 0.001 mm resolution). The results (table 2) show excellent material uniformity, with thickness variability (

![]() $\sigma _h / h_{\textit{avg}}$

) below 2 %. Subsequent calculations used the measured mean thickness,

$\sigma _h / h_{\textit{avg}}$

) below 2 %. Subsequent calculations used the measured mean thickness,

![]() $h_{\textit{avg}}$

, for improved accuracy. The total relative uncertainty in

$h_{\textit{avg}}$

, for improved accuracy. The total relative uncertainty in

![]() ${\textit{EI}}$

was estimated via error propagation (Taylor Reference Taylor2022):

${\textit{EI}}$

was estimated via error propagation (Taylor Reference Taylor2022):

This yields a maximum uncertainty of approximately 7.1 % for the thinnest plate, which has the largest thickness variability (1.7 %). The uncertainty from Young’s modulus (5.0 %) is a primary contributor, being comparable to or greater than the contribution from thickness (

![]() $0.23\,\% \leqslant 3\sigma _h/h_{\textit{avg}} \leqslant 5.1\,\%$

). Henceforth, plates are referred to by their nominal thickness,

$0.23\,\% \leqslant 3\sigma _h/h_{\textit{avg}} \leqslant 5.1\,\%$

). Henceforth, plates are referred to by their nominal thickness,

![]() $h_{\textit{nom}}$

(e.g. ‘the 0.30 mm plate’), for brevity. All calculations, however, use the measured mean thickness,

$h_{\textit{nom}}$

(e.g. ‘the 0.30 mm plate’), for brevity. All calculations, however, use the measured mean thickness,

![]() $h_{\textit{avg}}$

, from table 2.

$h_{\textit{avg}}$

, from table 2.

Table 2. Flexibility parameters of the polycarbonate plates. Here

![]() $h_{\textit{nom}}$

is the nominal thickness, while the mean thickness (

$h_{\textit{nom}}$

is the nominal thickness, while the mean thickness (

![]() $h_{\textit{avg}}$

) and its relative variability (

$h_{\textit{avg}}$

) and its relative variability (

![]() $\sigma _h/h_{\textit{avg}}$

) were determined from 16-point measurements. The bending stiffness (

$\sigma _h/h_{\textit{avg}}$

) were determined from 16-point measurements. The bending stiffness (

![]() ${\textit{EI}}$

) was calculated using the measured

${\textit{EI}}$

) was calculated using the measured

![]() $h_{\textit{avg}}$

. The total relative uncertainty shown in the final column,

$h_{\textit{avg}}$

. The total relative uncertainty shown in the final column,

![]() $\sigma _{\textit{EI}}/EI$

, results from propagating the uncertainties from two sources: the estimated uncertainty in Young’s Modulus and the measured variability in thickness, as detailed in (2.3).

$\sigma _{\textit{EI}}/EI$

, results from propagating the uncertainties from two sources: the estimated uncertainty in Young’s Modulus and the measured variability in thickness, as detailed in (2.3).

The flexible plate undergoes deformation due to its inability to resist the hydrodynamic forces during translation. To track this deformation, the chordwise plane crossing the centre of the circular plate was illuminated by the laser sheet. The deformation was recorded using the high-speed CMOS camera. A threshold-based image segmentation method (Suzuki et al. Reference Suzuki1985) was employed to extract the plate deformation. Due to the deformation, the projected area of the plate is given by

\begin{equation} S_p = 2 \int _0^{D/2} 2 \sqrt {\left (\frac {D}{2}\right )^2 - l^2} \cos \theta \, \mathrm{d}l, \end{equation}

\begin{equation} S_p = 2 \int _0^{D/2} 2 \sqrt {\left (\frac {D}{2}\right )^2 - l^2} \cos \theta \, \mathrm{d}l, \end{equation}

where

![]() $ l$

is the curvilinear coordinate along the radius from the centre towards the tip in the chordwise plane and can be expressed as

$ l$

is the curvilinear coordinate along the radius from the centre towards the tip in the chordwise plane and can be expressed as

and

![]() $ \theta$

is the angle between the plate and the vertical

$ \theta$

is the angle between the plate and the vertical

![]() $z$

axis. The cosine of the angle is defined as

$z$

axis. The cosine of the angle is defined as

where

![]() $ k$

is the slope of the curvilinear line. The dimensionless projected area is defined as

$ k$

is the slope of the curvilinear line. The dimensionless projected area is defined as

where

![]() $S = \pi D^2/4$

is considered the wetted area of the plate.

$S = \pi D^2/4$

is considered the wetted area of the plate.

Furthermore, the velocities of the plate centre

![]() $U_{{\textit{centre}}}$

and tip

$U_{{\textit{centre}}}$

and tip

![]() $U_{{\textit{tip}}}$

can be determined based on the displacement differences of the corresponding points at successive time frames.

$U_{{\textit{tip}}}$

can be determined based on the displacement differences of the corresponding points at successive time frames.

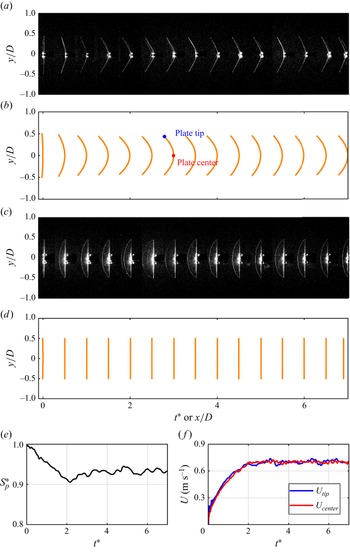

Figure 3. Shape tracing and kinematics of the flexible plate (

![]() $h_{\textit{nom}}=0.30\,\mathrm{mm}$

) for

$h_{\textit{nom}}=0.30\,\mathrm{mm}$

) for

![]() $a^*=0.25$

(

$a^*=0.25$

(

![]() $t_a^*=2.0$

) and

$t_a^*=2.0$

) and

![]() ${\textit{Re}}=7\times 10^4$

. (a,c) Raw images of the plate deformation in the chordwise and spanwise planes, respectively. In these images, the thick bright line is the plate’s centreline directly illuminated by the laser, while the thinner lines are the illuminated contours of the plate. The non-smooth appearance of the contour is an artefact of the multi-sub-FOV method used for image acquisition (§ 2.4), but it does not affect the accurate extraction of the centreline profile. (b,d) Corresponding traced profiles, showing a C-shaped deformation chordwise while the spanwise profile remains straight. (e) Evolution of the dimensionless projected area,

${\textit{Re}}=7\times 10^4$

. (a,c) Raw images of the plate deformation in the chordwise and spanwise planes, respectively. In these images, the thick bright line is the plate’s centreline directly illuminated by the laser, while the thinner lines are the illuminated contours of the plate. The non-smooth appearance of the contour is an artefact of the multi-sub-FOV method used for image acquisition (§ 2.4), but it does not affect the accurate extraction of the centreline profile. (b,d) Corresponding traced profiles, showing a C-shaped deformation chordwise while the spanwise profile remains straight. (e) Evolution of the dimensionless projected area,

![]() $S_p^*$

, with formation time. (f) Instantaneous velocities of the plate centre (

$S_p^*$

, with formation time. (f) Instantaneous velocities of the plate centre (

![]() $U_{{\textit{centre}}}$

) and tip (

$U_{{\textit{centre}}}$

) and tip (

![]() $U_{{\textit{tip}}}$

).

$U_{{\textit{tip}}}$

).

As a representative example, figure 3 shows the deformation of a flexible plate (

![]() $h_{\textit{nom}}=0.30\,\mathrm{mm}$

at

$h_{\textit{nom}}=0.30\,\mathrm{mm}$

at

![]() $a^* = 0.25$

and

$a^* = 0.25$

and

![]() ${\textit{Re}} = 7 \times 10^4$

). The plate exhibits a symmetric, C-shaped bending profile in the chordwise direction (figure 3

a), which contrasts with the multifold patterns reported by Schouveiler & Eloy (Reference Schouveiler and Eloy2013). This confirms that the central support constrains deformation to the intended beam-like mode (§ 2.1). The quantified profiles further show a clear C-shape chordwise while the spanwise section remains straight, confirming the suppression of multifold deformation (figure 3

b,d). Based on the traced geometries, the dimensionless projected area

${\textit{Re}} = 7 \times 10^4$

). The plate exhibits a symmetric, C-shaped bending profile in the chordwise direction (figure 3

a), which contrasts with the multifold patterns reported by Schouveiler & Eloy (Reference Schouveiler and Eloy2013). This confirms that the central support constrains deformation to the intended beam-like mode (§ 2.1). The quantified profiles further show a clear C-shape chordwise while the spanwise section remains straight, confirming the suppression of multifold deformation (figure 3

b,d). Based on the traced geometries, the dimensionless projected area

![]() $ S_p^*$

(figure 3

e), as well as the velocities of the plate centre and tip (figure 3

f), are calculated. To assess the run-to-run variability of the deformation, the shape tracking experiment was repeated five times. For this representative case, the run-to-run relative standard deviation of the projected area (

$ S_p^*$

(figure 3

e), as well as the velocities of the plate centre and tip (figure 3

f), are calculated. To assess the run-to-run variability of the deformation, the shape tracking experiment was repeated five times. For this representative case, the run-to-run relative standard deviation of the projected area (

![]() $S_p^*$

) is less than

$S_p^*$

) is less than

![]() $0.01\,\%$

, while for the centre and tip velocities it is

$0.01\,\%$

, while for the centre and tip velocities it is

![]() $0.8\,\%$

and

$0.8\,\%$

and

![]() $1.9\,\%$

, respectively. The low variability in

$1.9\,\%$

, respectively. The low variability in

![]() $S_p^*$

is expected, as its integral calculation smooths noise from the position data. Conversely, the higher velocity variability results from numerical differentiation, which is known to amplify noise. The slightly greater variation at the tip is attributed to its unconstrained free-end condition. These low deviations confirm the high repeatability of the measurements. Across all cases considered (table 3), the maximum relative standard deviation for

$S_p^*$

is expected, as its integral calculation smooths noise from the position data. Conversely, the higher velocity variability results from numerical differentiation, which is known to amplify noise. The slightly greater variation at the tip is attributed to its unconstrained free-end condition. These low deviations confirm the high repeatability of the measurements. Across all cases considered (table 3), the maximum relative standard deviation for

![]() $S_p^*$

did not exceed 0.13 %. This quantitative evidence of low standard deviation confirms that the plate’s motion is repeatable, dominated by large-scale fluid–structure reconfiguration rather than random vibrations.

$S_p^*$

did not exceed 0.13 %. This quantitative evidence of low standard deviation confirms that the plate’s motion is repeatable, dominated by large-scale fluid–structure reconfiguration rather than random vibrations.

Table 3. Nomenclature used in the study. ‘R-’ denotes rigid plates with

![]() ${\textit{EI}}^* = 2.66 \times 10^{-1}$

, ‘F-’ represents flexible plates with

${\textit{EI}}^* = 2.66 \times 10^{-1}$

, ‘F-’ represents flexible plates with

![]() ${\textit{EI}}^* = 1.16 \times 10^{-2}$

and ‘EF-’ indicates extra-flexible plates with

${\textit{EI}}^* = 1.16 \times 10^{-2}$

and ‘EF-’ indicates extra-flexible plates with

![]() ${\textit{EI}}^* = 1.19 \times 10^{-2}$

. The number following each letter specifies the corresponding Reynolds number. All cases were conducted under the conditions of

${\textit{EI}}^* = 1.19 \times 10^{-2}$

. The number following each letter specifies the corresponding Reynolds number. All cases were conducted under the conditions of

![]() $a^*=0.25$

(

$a^*=0.25$

(

![]() $t_{a}^*=2.0$

).

$t_{a}^*=2.0$

).

2.3. Force data acquisition

The hydrodynamic force measurement scheme was adapted from the work of Reynolds et al. (Reference Reynolds, Thomas and Taylor2014), Grift et al. (Reference Grift, Vijayaragavan, Tummers and Westerweel2019) and Fernando & Rival (Reference Fernando and Rival2016a

). A force/torque transducer (ATI Gamma F/T Mux SI-130-10) was installed between the linear guide and the L-shaped sting, as shown in figure 1. The Gamma F/T Mux force transducer has a force range of

![]() $\pm 130$

N with a resolution of 0.025 N. Data were recorded at a sampling frequency of 7000 Hz in this study. Under static conditions, the natural frequency of the system was approximately

$\pm 130$

N with a resolution of 0.025 N. Data were recorded at a sampling frequency of 7000 Hz in this study. Under static conditions, the natural frequency of the system was approximately

![]() $48.7 \pm 3.3$

Hz in air and

$48.7 \pm 3.3$

Hz in air and

![]() $46.7\pm 3.3$

Hz in water. Under dynamic conditions as listed in table 1, the natural frequency was approximately

$46.7\pm 3.3$

Hz in water. Under dynamic conditions as listed in table 1, the natural frequency was approximately

![]() $50.3 \pm 1.4$

Hz in air and

$50.3 \pm 1.4$

Hz in air and

![]() $48.0 \pm 1.1$

Hz in water. Based on the kinematics of the plate in this study as mentioned in § 2.2, the time interval corresponding to the plate’s acceleration is

$48.0 \pm 1.1$

Hz in water. Based on the kinematics of the plate in this study as mentioned in § 2.2, the time interval corresponding to the plate’s acceleration is

![]() $[0.0625\, \mathrm{s} , 1.0\, \mathrm{s} ]$

or

$[0.0625\, \mathrm{s} , 1.0\, \mathrm{s} ]$

or

![]() $[1\, \mathrm{Hz} , 16\, \mathrm{Hz}]$

, different from the natural frequency to avoid resonance. A low-pass filter with a 40 Hz cutoff frequency was first applied to remove high-frequency noise. Subsequently, a second-order Savitzky–Golay filter (Savitzky & Golay Reference Savitzky and Golay1964) with a filter window width of

$[1\, \mathrm{Hz} , 16\, \mathrm{Hz}]$

, different from the natural frequency to avoid resonance. A low-pass filter with a 40 Hz cutoff frequency was first applied to remove high-frequency noise. Subsequently, a second-order Savitzky–Golay filter (Savitzky & Golay Reference Savitzky and Golay1964) with a filter window width of

![]() $\Delta t^* = 0.1$

was used to reduce noise. This window corresponds to an absolute time range of

$\Delta t^* = 0.1$

was used to reduce noise. This window corresponds to an absolute time range of

![]() $[0.015\, \mathrm{s}, 0.055\, \mathrm{s}]$

, allowing for 6–20 filter windows during the acceleration phase to retain as much instantaneous force information as possible. The sensitivity of the filter window is quantified in Appendix A2.

$[0.015\, \mathrm{s}, 0.055\, \mathrm{s}]$

, allowing for 6–20 filter windows during the acceleration phase to retain as much instantaneous force information as possible. The sensitivity of the filter window is quantified in Appendix A2.

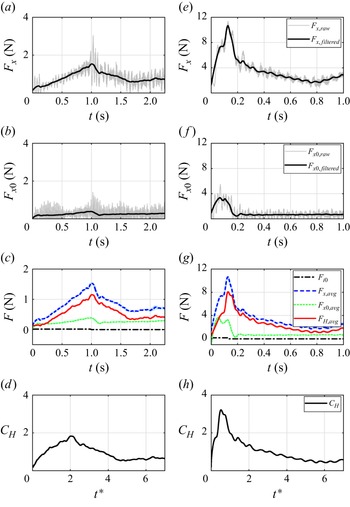

Figure 4. Force data acquisition for a 3.00 mm-thick plate was conducted under the conditions of

![]() $ a^* = 0.25$

(

$ a^* = 0.25$

(

![]() $t_a^*=2.0$

),

$t_a^*=2.0$

),

![]() ${\textit{Re}} = 4 \times 10^4$

in panels (a–d), and under the conditions of

${\textit{Re}} = 4 \times 10^4$

in panels (a–d), and under the conditions of

![]() $ a^* = 1.0$

(

$ a^* = 1.0$

(

![]() $t_a^*=0.5$

),

$t_a^*=0.5$

),

![]() ${\textit{Re}} = 8 \times 10^4$

in panels (e–h). Panels (a) and (e) illustrate the raw force

${\textit{Re}} = 8 \times 10^4$

in panels (e–h). Panels (a) and (e) illustrate the raw force

![]() $ F_{x,{raw}}$

(grey thin solid lines) obtained from a single measurement on the plate, along with its filtered results

$ F_{x,{raw}}$

(grey thin solid lines) obtained from a single measurement on the plate, along with its filtered results

![]() $ F_{x,{filtered}}$

(black thin solid lines) as a function of time

$ F_{x,{filtered}}$

(black thin solid lines) as a function of time

![]() $ t$

. The force measurements without the plate are depicted in panels (b) and (f). The relative standard deviations of

$ t$

. The force measurements without the plate are depicted in panels (b) and (f). The relative standard deviations of

![]() $ F_{x,{avg}}$

and

$ F_{x,{avg}}$

and

![]() $ F_{x0,{avg}}$

are 1.0 % and 1.3 %, respectively, relative to the maximum value in panel (c), and 0.9 % and 0.4 % in panel (g) over 10 measurements, indicating excellent repeatability of the data. The resultant hydrodynamic forces

$ F_{x0,{avg}}$

are 1.0 % and 1.3 %, respectively, relative to the maximum value in panel (c), and 0.9 % and 0.4 % in panel (g) over 10 measurements, indicating excellent repeatability of the data. The resultant hydrodynamic forces

![]() $ F_H$

(red solid line) in panels (c) and (g) are obtained by subtracting

$ F_H$

(red solid line) in panels (c) and (g) are obtained by subtracting

![]() $ F_{x,{avg}}$

(blue dashed line) from

$ F_{x,{avg}}$

(blue dashed line) from

![]() $ F_{x0,{avg}}$

(green dotted line) and the inertial force

$ F_{x0,{avg}}$

(green dotted line) and the inertial force

![]() $ F_{i_0}$

(black dashed–dotted line, accounts for less than 0.1 % of

$ F_{i_0}$

(black dashed–dotted line, accounts for less than 0.1 % of

![]() $ F_H$

) in both panels (c) and (g). Lastly, the hydrodynamic force coefficients

$ F_H$

) in both panels (c) and (g). Lastly, the hydrodynamic force coefficients

![]() $ C_H$

are plotted against the dimensionless time

$ C_H$

are plotted against the dimensionless time

![]() $ t^*$

in panels (d) and (h).

$ t^*$

in panels (d) and (h).

In actual measurements, the force with the plate attached in the

![]() $x$

-direction

$x$

-direction

![]() $F_x$

was first measured and filtered as exemplified in figure 4(a,e). Subsequently, the force without the flexible plate in the

$F_x$

was first measured and filtered as exemplified in figure 4(a,e). Subsequently, the force without the flexible plate in the

![]() $x$

-direction

$x$

-direction

![]() $F_{x0}$

was measured and filtered as shown in figure 4(b,f). Considering the inertial force

$F_{x0}$

was measured and filtered as shown in figure 4(b,f). Considering the inertial force

![]() $F_i(t)$

due to the acceleration of the plate itself, the hydrodynamic force can be expressed as

$F_i(t)$

due to the acceleration of the plate itself, the hydrodynamic force can be expressed as

where, due to the bending deformation, the acceleration at different parts of the plate varies. Specifically, since the flexible deformation is directed backwards, during the acceleration phase, the acceleration of each part of the plate is less than that of the plate centre, i.e.

![]() $\partial U_i / \partial t \leqslant a$

. Therefore, the actual inertial force of the flexible plate is less than its inertial force in the undeformed state, i.e.

$\partial U_i / \partial t \leqslant a$

. Therefore, the actual inertial force of the flexible plate is less than its inertial force in the undeformed state, i.e.

\begin{equation} F_i(t) = 2 \sum _{i=0}^{N} m_i \frac {\partial U_i}{\partial t} \leqslant F_{i0}(t) = 2 \sum _{i=0}^{N} m_i a(t) = \rho _m S h a(t), \end{equation}

\begin{equation} F_i(t) = 2 \sum _{i=0}^{N} m_i \frac {\partial U_i}{\partial t} \leqslant F_{i0}(t) = 2 \sum _{i=0}^{N} m_i a(t) = \rho _m S h a(t), \end{equation}

where, the deformation of different segments with mass

![]() $ m_i$

of the plate was obtained, allowing us to determine the displacement

$ m_i$

of the plate was obtained, allowing us to determine the displacement

![]() $ x_i$

, velocity

$ x_i$

, velocity

![]() $ U_i$

and acceleration

$ U_i$

and acceleration

![]() $ \partial U_i/\partial t$

for each segment;

$ \partial U_i/\partial t$

for each segment;

![]() $i=0$

is the segment through the centre of the plate and

$i=0$

is the segment through the centre of the plate and

![]() $i=N$

is the segment of the tip of the plate. As shown in figure 4(c,g),

$i=N$

is the segment of the tip of the plate. As shown in figure 4(c,g),

![]() $F_{i0}(t)$

accounts for less than 0.1 % of the hydrodynamic force. Thus,

$F_{i0}(t)$

accounts for less than 0.1 % of the hydrodynamic force. Thus,

![]() $F_{i0}(t)$

can be neglected and the calculation of

$F_{i0}(t)$

can be neglected and the calculation of

![]() $F_H(t)$

can be approximated as

$F_H(t)$

can be approximated as

The resulting hydrodynamic force is shown in figure 4(c,g). All data sets were averaged over 10 runs. The relative standard deviation of the hydrodynamic force for each plate is less than 1.3 %. Based on the hydrodynamic force, the classical hydrodynamic force coefficient is defined as

\begin{equation} C_H = \frac {F_H}{\dfrac {1}{2} \rho _{\!f} U_c^2 S}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} C_H = \frac {F_H}{\dfrac {1}{2} \rho _{\!f} U_c^2 S}. \end{equation}

The resulting force coefficient

![]() $C_H$

is shown in figure 4(d,h). The uncertainty in the hydrodynamic force coefficient,

$C_H$

is shown in figure 4(d,h). The uncertainty in the hydrodynamic force coefficient,

![]() $C_H$

, was quantified using error propagation. The worst-case scenario was selected based on the physical acceleration (

$C_H$

, was quantified using error propagation. The worst-case scenario was selected based on the physical acceleration (

![]() $a = a^* U_c^2 / D$

), which is the primary driver of vibrational noise in the measurements. The high-acceleration kinematics validation case (

$a = a^* U_c^2 / D$

), which is the primary driver of vibrational noise in the measurements. The high-acceleration kinematics validation case (

![]() $a^*=1.0, Re=8 \times 10^4$

), with

$a^*=1.0, Re=8 \times 10^4$

), with

![]() $a \approx 6.43\,{\rm m\,s}^{-2}$

, was therefore chosen as the most conservative benchmark. Assuming uncorrelated errors, the uncertainty in

$a \approx 6.43\,{\rm m\,s}^{-2}$

, was therefore chosen as the most conservative benchmark. Assuming uncorrelated errors, the uncertainty in

![]() $C_H$

is propagated from the standard deviations of the measured forces (

$C_H$

is propagated from the standard deviations of the measured forces (

![]() $\sigma _{F_x}$

and

$\sigma _{F_x}$

and

![]() $\sigma _{F_{x0}}$

) as

$\sigma _{F_{x0}}$

) as

\begin{equation} \sigma _{C_H} = \frac {\sqrt {\sigma _{F_x}^2 + \sigma _{F_{x0}}^2}}{\dfrac {1}{2}\rho _{\!f} U_c^2 S}. \end{equation}

\begin{equation} \sigma _{C_H} = \frac {\sqrt {\sigma _{F_x}^2 + \sigma _{F_{x0}}^2}}{\dfrac {1}{2}\rho _{\!f} U_c^2 S}. \end{equation}

Using data from this high-acceleration benchmark case (figure 4), the propagated uncertainty was estimated to be approximately 2.9 %, which confirms the high precision of the force measurements.

Further, the instantaneous force coefficient normalized by the projected area can be defined as

The

![]() $C_H$

of the 3.00 mm-thick plate at

$C_H$

of the 3.00 mm-thick plate at

![]() $a^* = 0.50$

,

$a^* = 0.50$

,

![]() $1.0$

and

$1.0$

and

![]() $2.0$

, and

$2.0$

, and

![]() ${\textit{Re}} = 8 \times 10^4$

was used to compare with results from the previous literature, as shown in figure 5. Within

${\textit{Re}} = 8 \times 10^4$

was used to compare with results from the previous literature, as shown in figure 5. Within

![]() $t^* \in [0,7]$

, the deviation between the force measurement results of this study and Li et al. (Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022) is 1.1 %, and Fernando et al. (Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020) is 4.6 %.

$t^* \in [0,7]$

, the deviation between the force measurement results of this study and Li et al. (Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022) is 1.1 %, and Fernando et al. (Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020) is 4.6 %.

Figure 5. The force data acquisition was validated by comparing the results with previously published data for a rigid plate (

![]() $h_{\textit{nom}}=3.00 \, \mathrm{mm}$

): (a)

$h_{\textit{nom}}=3.00 \, \mathrm{mm}$

): (a)

![]() $a^* = 0.5$

(

$a^* = 0.5$

(

![]() $t_a^*=1.0$

),

$t_a^*=1.0$

),

![]() ${\textit{Re}}=8\times 10^4$

; (b)

${\textit{Re}}=8\times 10^4$

; (b)

![]() $a^* = 1.0$

(

$a^* = 1.0$

(

![]() $t_a^*=0.5$

),

$t_a^*=0.5$

),

![]() ${\textit{Re}}=8\times 10^4$

; (c)

${\textit{Re}}=8\times 10^4$

; (c)

![]() $a^* = 2.0$

(

$a^* = 2.0$

(

![]() $t_a^*=0.25$

),

$t_a^*=0.25$

),

![]() ${\textit{Re}}=8\times 10^4$

. The green solid lines are adopted from the Fernando et al. (Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020), blue solid lines are adopted from Li et al. (Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022) and the red solid lines are the force coefficient measured by current set-up. It is important to note that the definition of the drag coefficient in Fernando et al. (Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020) differs from the definition of the hydrodynamic coefficient used in this study by a factor of

${\textit{Re}}=8\times 10^4$

. The green solid lines are adopted from the Fernando et al. (Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020), blue solid lines are adopted from Li et al. (Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022) and the red solid lines are the force coefficient measured by current set-up. It is important to note that the definition of the drag coefficient in Fernando et al. (Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020) differs from the definition of the hydrodynamic coefficient used in this study by a factor of

![]() $\pi /8$

, and to ensure a fair comparison, the data from Fernando et al. (Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020) have been adjusted accordingly.

$\pi /8$

, and to ensure a fair comparison, the data from Fernando et al. (Reference Fernando, Weymouth and Rival2020) have been adjusted accordingly.

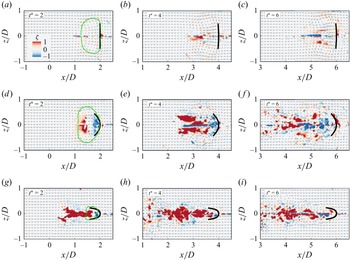

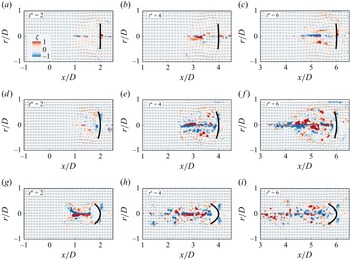

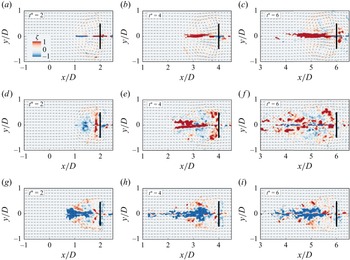

2.4. Flow field measurement

Two-dimensional, two-velocity-component (2D2C) time-resolved planar PIV was employed to quantitatively capture the flow fields. The 2D2C PIV configuration was deemed sufficient for this study’s primary goal: to uncover the physical mechanisms behind the load-shifting phenomenon. While vortex rings are inherently three-dimensional (3-D), a multislice measurement strategy was implemented to capture the critical wake features. This planar approach is directly compatible with the vorticity moment theorem used for force estimation, which requires only 2-D velocity and vorticity data (§ 5.1).

Multislice measurements were conducted in three representative cross-sectional planes relative to the plate: the chordwise (

![]() $\theta = 0^\circ$

), diagonal (

$\theta = 0^\circ$

), diagonal (

![]() $\theta = 45^\circ$

) and spanwise (

$\theta = 45^\circ$

) and spanwise (

![]() $\theta = 90^\circ$

) sections. In each case, the laser sheet was projected from the left-hand side of the water tank across the plate’s centre, as illustrated in figure 1. A high-speed CMOS camera (Phantom VEO-640) positioned perpendicular to the laser sheet recorded the particle field images. To capture the flow fields of different cross-sections, the plate’s orientation was altered while the laser and camera positions remained fixed. This was accomplished using three separate horizontal rods, each fabricated with a mounting slot milled at a distinct angle (

$\theta = 90^\circ$

) sections. In each case, the laser sheet was projected from the left-hand side of the water tank across the plate’s centre, as illustrated in figure 1. A high-speed CMOS camera (Phantom VEO-640) positioned perpendicular to the laser sheet recorded the particle field images. To capture the flow fields of different cross-sections, the plate’s orientation was altered while the laser and camera positions remained fixed. This was accomplished using three separate horizontal rods, each fabricated with a mounting slot milled at a distinct angle (

![]() $0^\circ$

,

$0^\circ$

,

![]() $45^\circ$

or

$45^\circ$

or

![]() $90^\circ$

). Appendix A3 validates its effectiveness for consistently characterizing the different cross-sections of the wake. Hollow glass beads (spherical, density

$90^\circ$

). Appendix A3 validates its effectiveness for consistently characterizing the different cross-sections of the wake. Hollow glass beads (spherical, density

![]() $\rho _g = 1.03$

–

$\rho _g = 1.03$

–

![]() $1.05$

g cm−

$1.05$

g cm−

![]() $^3$

, diameter

$^3$

, diameter

![]() $d_g = 20$

–

$d_g = 20$

–

![]() $60 \, {\unicode{x03BC}} \mathrm{m}$

) served as tracer particles, illuminated by a double-pulsed 527 nm Nd-YLF laser (Beamtech Vlite-Hi-527,

$60 \, {\unicode{x03BC}} \mathrm{m}$

) served as tracer particles, illuminated by a double-pulsed 527 nm Nd-YLF laser (Beamtech Vlite-Hi-527,

![]() $\geqslant$

30 mJ at 1 kHz).

$\geqslant$

30 mJ at 1 kHz).

To maximize spatial resolution, theoretically, the FOV of over

![]() $7D$

was divided into three sub-FOVs along the

$7D$

was divided into three sub-FOVs along the

![]() $x$

-axis: sub-FOV1 (

$x$

-axis: sub-FOV1 (

![]() $-1D$

to

$-1D$

to

![]() $2D$

), sub-FOV2 (

$2D$

), sub-FOV2 (

![]() $2D$

to

$2D$

to

![]() $5D$

) and sub-FOV3 (

$5D$

) and sub-FOV3 (

![]() $5D$

to

$5D$

to

![]() $8D$

), where each sub-FOV was designed to have a theoretical size of

$8D$

), where each sub-FOV was designed to have a theoretical size of

![]() $3D \times 2D$

. The sub-FOVs were captured by fixing the camera and laser while altering the plate’s SP: SP1 for sub-FOV1, SP2 for sub-FOV2 and SP3 for sub-FOV3. Each sub-FOV was measured five times, with a 60 s interval between runs to avoid flow interference from prior tests. The distance between SP3 and the wall was

$3D \times 2D$

. The sub-FOVs were captured by fixing the camera and laser while altering the plate’s SP: SP1 for sub-FOV1, SP2 for sub-FOV2 and SP3 for sub-FOV3. Each sub-FOV was measured five times, with a 60 s interval between runs to avoid flow interference from prior tests. The distance between SP3 and the wall was

![]() $5D$

, sufficient to minimize wall effects. This distance was chosen also based on the laser beam waist, which was approximately 1 m from the laser head. As the deviation from this distance increases, the laser sheet thickness also increases, potentially introducing larger PIV errors. In this experiment, the distance between the centre of captured FOV to the laser head was 1.35 m, ensuring good imaging results while maintaining acceptable laser sheet thickness.

$5D$

, sufficient to minimize wall effects. This distance was chosen also based on the laser beam waist, which was approximately 1 m from the laser head. As the deviation from this distance increases, the laser sheet thickness also increases, potentially introducing larger PIV errors. In this experiment, the distance between the centre of captured FOV to the laser head was 1.35 m, ensuring good imaging results while maintaining acceptable laser sheet thickness.

In practice, each sub-FOV spanned

![]() $3.65D \times 2.28D$

by recorded with 2560

$3.65D \times 2.28D$

by recorded with 2560

![]() $\times$

1600 pixels (figure 1) and the adjacent windows overlapped and were stitched using interpolation (Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022). The sampling frequency for PIV data was 800 Hz, ensuring high temporal resolution. To ensure an optimal time delay (

$\times$

1600 pixels (figure 1) and the adjacent windows overlapped and were stitched using interpolation (Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022). The sampling frequency for PIV data was 800 Hz, ensuring high temporal resolution. To ensure an optimal time delay (

![]() $\Delta t$

) between frames, the maximum particle displacement was restricted to

$\Delta t$

) between frames, the maximum particle displacement was restricted to

![]() $0.25S_{{IS}}$

, where

$0.25S_{{IS}}$

, where

![]() $S_{{IS}}$

is the size of the interrogation spot. Using characteristic velocity

$S_{{IS}}$

is the size of the interrogation spot. Using characteristic velocity

![]() $U_c$

,

$U_c$

,

![]() $\Delta t$

was computed as

$\Delta t$

was computed as

![]() $\Delta t = 0.25 S_{{IS}}/2U_c$

, considering the maximum flow velocity magnitude to be approximately twice the plate’s translation velocity (Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022).

$\Delta t = 0.25 S_{{IS}}/2U_c$

, considering the maximum flow velocity magnitude to be approximately twice the plate’s translation velocity (Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022).

Figure 6. Effect of Reynolds number

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

on transient force evolution for plates with

${\textit{Re}}$

on transient force evolution for plates with

![]() $a^*=0.25$

(

$a^*=0.25$

(

![]() $t_a^*=2.0$

) and varying bending stiffness: (a)

$t_a^*=2.0$

) and varying bending stiffness: (a)

![]() $h = 2.00 \, \mathrm{mm}, EI = 1.72\, \mathrm{Nm}$

; (b)

$h = 2.00 \, \mathrm{mm}, EI = 1.72\, \mathrm{Nm}$

; (b)

![]() $h = 0.30 \, \mathrm{mm}, EI = 5.79\times 10^{-3} \, \mathrm{Nm}$

; (c)

$h = 0.30 \, \mathrm{mm}, EI = 5.79\times 10^{-3} \, \mathrm{Nm}$

; (c)

![]() $h = 0.125 \, \mathrm{mm}, EI = 4.19\times 10^{-4} \, \mathrm{Nm}$

.

$h = 0.125 \, \mathrm{mm}, EI = 4.19\times 10^{-4} \, \mathrm{Nm}$

.

Image processing was performed using TSI Insight 4G software, following PIV analysis guidelines (Keane & Adrian Reference Keane and Adrian1989). Background subtraction and light intensity normalization (10

![]() $\times$

10 pixel window) were applied to mitigate measurement bias caused by particle brightness and laser intensity variations. The multipass method was applied with interrogation spot sizes of

$\times$

10 pixel window) were applied to mitigate measurement bias caused by particle brightness and laser intensity variations. The multipass method was applied with interrogation spot sizes of

![]() $64 \times 64$

pixels (initial pass) and

$64 \times 64$

pixels (initial pass) and

![]() $32 \times 32$

pixels (final pass), with a 50 % overlap. This yielded

$32 \times 32$

pixels (final pass), with a 50 % overlap. This yielded

![]() $159 \times 99$

velocity vectors per sub-FOV with a vector spacing of 2.31 mm. Vorticity fields were calculated using second-order finite differences on velocity data from eight neighbouring points.

$159 \times 99$

velocity vectors per sub-FOV with a vector spacing of 2.31 mm. Vorticity fields were calculated using second-order finite differences on velocity data from eight neighbouring points.

Uncertainty in flow measurements was estimated using the peak ratio method (Charonko & Vlachos Reference Charonko and Vlachos2013), incorporated in the Insight 4G software. This global method accounts for errors such as particle density, pixel displacement and preprocessing. For this study, velocity field uncertainty across all runs was less than 1.2 %.

To ensure statistical robustness, five independent runs were conducted for each representative case. The run-to-run variability of the derived flow metrics (discussed in §§ 4 and 5) proved to be minimal, with relative standard deviations for key integral quantities remaining below 4.9 %. Consequently,

![]() $\pm 1\sigma$

confidence intervals are included in the subsequent time-evolution plots to demonstrate the deterministic nature of the observed flow features. Furthermore, to calculate time derivatives for force estimation (§ 5), the same second-order Savitzky–Golay filter (

$\pm 1\sigma$

confidence intervals are included in the subsequent time-evolution plots to demonstrate the deterministic nature of the observed flow features. Furthermore, to calculate time derivatives for force estimation (§ 5), the same second-order Savitzky–Golay filter (

![]() $\Delta t^*=0.1$

, consistent with the force filter in Appendix A2) was applied to the PIV-derived time series.

$\Delta t^*=0.1$

, consistent with the force filter in Appendix A2) was applied to the PIV-derived time series.

3. Force

3.1.

Force evolution across different

${\textit{Re}}$

and

${\textit{Re}}$

and

${\textit{EI}}$

${\textit{EI}}$

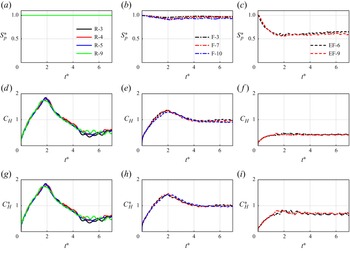

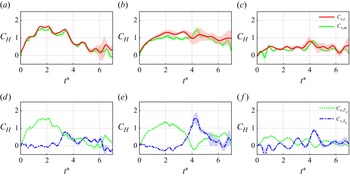

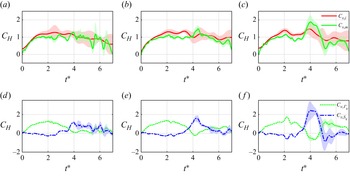

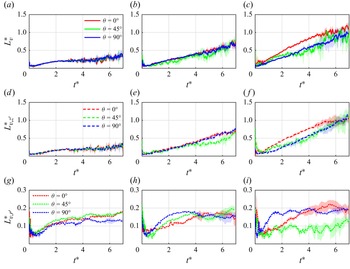

The transient hydrodynamic force coefficients for circular plates with three orders of magnitude in bending stiffness,

![]() ${\textit{EI}} = 1.72\, \mathrm{Nm}$

,

${\textit{EI}} = 1.72\, \mathrm{Nm}$

,

![]() $5.79\times 10^{-3} \, \mathrm{Nm}$

and

$5.79\times 10^{-3} \, \mathrm{Nm}$

and

![]() $4.19\times 10^{-4} \, \mathrm{Nm}$

, under varying Reynolds numbers

$4.19\times 10^{-4} \, \mathrm{Nm}$

, under varying Reynolds numbers

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

are shown in figure 6.

${\textit{Re}}$

are shown in figure 6.

For the plate with bending stiffness

![]() ${\textit{EI}} = 1.72\, \mathrm{Nm}$

(corresponding to a thickness of

${\textit{EI}} = 1.72\, \mathrm{Nm}$

(corresponding to a thickness of

![]() $h = 2.00 \, \mathrm{mm}$

), which behaves as a rigid plate with negligible deformation, the force curves collapse well across different Reynolds numbers, confirming a clear Reynolds number independence (Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016b

; Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022). Furthermore, the force evolution exhibits a distinct peak-and-valley pattern (figure 6

a). During acceleration, the force increases rapidly with

$h = 2.00 \, \mathrm{mm}$

), which behaves as a rigid plate with negligible deformation, the force curves collapse well across different Reynolds numbers, confirming a clear Reynolds number independence (Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016b

; Li et al. Reference Li, Xiang, Qin, Liu and Wang2022). Furthermore, the force evolution exhibits a distinct peak-and-valley pattern (figure 6

a). During acceleration, the force increases rapidly with

![]() $t^*$

, reaching a peak at

$t^*$

, reaching a peak at

![]() $t^* = 2$

, followed by a decrease to a minimum at

$t^* = 2$

, followed by a decrease to a minimum at

![]() $t^* \approx 5.5$

– the so-called ‘drag trough’ (Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016a

) – before rising again.

$t^* \approx 5.5$

– the so-called ‘drag trough’ (Fernando & Rival Reference Fernando and Rival2016a

) – before rising again.

As the bending stiffness decreases to

![]() ${\textit{EI}} = 5.79\times 10^{-3} \, \mathrm{Nm}$

(corresponding to a plate thickness of

${\textit{EI}} = 5.79\times 10^{-3} \, \mathrm{Nm}$

(corresponding to a plate thickness of

![]() $h = 0.30 \, \mathrm{mm}$

), the force response exhibits significant changes with increasing Reynolds number, leading to a breakdown of Reynolds number independence (figure 6

b). At

$h = 0.30 \, \mathrm{mm}$

), the force response exhibits significant changes with increasing Reynolds number, leading to a breakdown of Reynolds number independence (figure 6

b). At

![]() ${\textit{Re}} = 4 \times 10^4$

, the characteristic peak-and-valley pattern persists, with a distinct force peak at

${\textit{Re}} = 4 \times 10^4$

, the characteristic peak-and-valley pattern persists, with a distinct force peak at

![]() $t^* = 2$

and a trough at

$t^* = 2$

and a trough at

![]() $t^* \approx 5.5$

. However, compared with the rigid plate, the peak force is reduced, while the trough force is elevated. As

$t^* \approx 5.5$

. However, compared with the rigid plate, the peak force is reduced, while the trough force is elevated. As

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

increases, the force peak gradually flattens, and the trough becomes less pronounced. At

${\textit{Re}}$

increases, the force peak gradually flattens, and the trough becomes less pronounced. At

![]() ${\textit{Re}} = 10 \times 10^4$

, the peak-and-valley pattern disappears entirely, resulting in a smooth and uniform force evolution with no discernible extrema. Notably, the force coefficient at

${\textit{Re}} = 10 \times 10^4$

, the peak-and-valley pattern disappears entirely, resulting in a smooth and uniform force evolution with no discernible extrema. Notably, the force coefficient at

![]() $t^* \approx 5.5$

initially increases with

$t^* \approx 5.5$

initially increases with

![]() ${\textit{Re}}$

before declining at higher values. These results indicate that, as the bending stiffness decreases, the unsteady force dynamics lose their Reynolds number independence, underscoring the coupled effects of flexibility and Reynolds number on force evolution.

${\textit{Re}}$

before declining at higher values. These results indicate that, as the bending stiffness decreases, the unsteady force dynamics lose their Reynolds number independence, underscoring the coupled effects of flexibility and Reynolds number on force evolution.

For plates with further reduced bending stiffness to

![]() ${\textit{EI}} = 4.19\times 10^{-4} \, \mathrm{Nm}$

(corresponding to a thickness of

${\textit{EI}} = 4.19\times 10^{-4} \, \mathrm{Nm}$

(corresponding to a thickness of

![]() $h = 0.125 \, \mathrm{mm}$

), the force curves remain non-collapsing across Reynolds numbers but exhibit consistent trends: a rapid rise during acceleration followed by stabilization with negligible fluctuations. The peak-and-valley pattern disappears entirely.

$h = 0.125 \, \mathrm{mm}$

), the force curves remain non-collapsing across Reynolds numbers but exhibit consistent trends: a rapid rise during acceleration followed by stabilization with negligible fluctuations. The peak-and-valley pattern disappears entirely.

Overall, these results emphasize the coupled effects of Reynolds number and flexibility on unsteady force dynamics, causing the force evolution on reconfigurable plates to deviate from the Reynolds number independence and peak-and-valley pattern observed in rigid plates.

3.2.

Non-dimensional bending stiffness

${\textit{EI}}^*$

independence of force evolution

${\textit{EI}}^*$

independence of force evolution

The breakdown of Reynolds number scaling stems from its primary focus on fluid dynamics, whereas the reconfigurable plate in this study undergoes deformation that modifies the surrounding flow, resulting in a coupled fluid–structure interaction. To characterize this interaction, a non-dimensional bending stiffness,

![]() ${\textit{EI}}^*$

, is employed as

${\textit{EI}}^*$

, is employed as

The physical significance of

![]() ${\textit{EI}}^*$

has been interpreted differently across various studies. From an energy perspective, Schouveiler & Boudaoud (Reference Schouveiler and Boudaoud2006) defined the elastohydrodynamical number, expressed as

${\textit{EI}}^*$

has been interpreted differently across various studies. From an energy perspective, Schouveiler & Boudaoud (Reference Schouveiler and Boudaoud2006) defined the elastohydrodynamical number, expressed as

![]() $ 1/{\textit{EI}}^*$