Free, fair, and accurate elections are a cornerstone of a healthy democracy. In the United States, states are primarily responsible for election administration, including the maintenance of voter registration lists. These lists require regular maintenance as voters move, become eligible to vote, or die. Accurate voter rolls increase trust in the electoral process by facilitating efficient elections, reducing the risk of fraud, and improving the voting experience. Similarly, high turnout in elections is viewed as critical to democratic governance. Broad participation strengthens democratic legitimacy and perceived government responsiveness (Hasen Reference Hasen1996, 2165–66; Verba and Nie Reference Verba and Nie1972). Indeed, the American government’s foundational principle of popular sovereignty fundamentally depends on the consent of the governed, expressed through broad citizen participation in regular elections (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1788).

In 2012, the Electronic Registration Information Center (ERIC) was founded to help states accomplish these goals. ERIC is a data-sharing tool for states to maintain the integrity of their voter registration rolls through regular list maintenance and to encourage voter participation. Originally founded by the Pew Charitable Trusts and seven states, ERIC expanded to a peak membership of 33 states. By matching voter lists to other administrative data, ERIC facilitates the cleaning of voter rolls and helps states identify citizens who appear eligible but unregistered (EBU).

In 2022, some Republicans began criticizing ERIC’s efforts to encourage EBUs to register and vote as a tool for left-wing electioneering (among other concerns). Criticism of ERIC eventually led to the withdrawal of nine Republican-led states, prompting concerns that the result would be less accurate voter registration databases and lower confidence in elections (Underhill Reference Underhill2023). Since withdrawing from ERIC, some states have admitted to erroneously purging thousands of voters from registration lists (Paviour Reference Paviour2023), suggesting that states’ withdrawal from ERIC could undermine the ability of some citizens to vote.

Using 2016 election data generated from field experiments in Pennsylvania and Nevada, this article assesses the validity of claims that ERIC voter registration efforts benefit one political party over another. In addition to providing evidence to inform an important controversy central to American democracy, our research informs ongoing scholarly debates regarding the potential partisan implications of mobilizing unregistered citizens.

…our research informs ongoing scholarly debates regarding the potential partisan implications of mobilizing unregistered citizens.

Across both states, our results indicate that ERIC did not benefit one political party over the other. We find small, electorally inconsequential, and statistically insignificant partisan differences. The estimated raw vote differences between parties in registrations and turnout range in the low thousands and do not consistently benefit either party.

…results indicate that ERIC did not benefit one political party over the other. We find small, electorally inconsequential, and statistically insignificant partisan differences.

BACKGROUND

In July 2023, Texas became the ninth Republican-led state to withdraw from ERIC in 18 months (Coronado and Cassidy Reference Coronado and Cassidy2023). Leaders in each state cited similar reasons for withdrawal, with most of the justifications including claims that participation in ERIC carried “partisan” implications. For instance, Florida’s Secretary of State cited “concerns about data privacy and blatant partisanship” (Shelton Reference Shelton2023). The Louisiana Secretary of State (2022) claimed that “possibly partisan actors may have access to ERIC network data for political purposes.” The Ohio Secretary of State cited concerns that ERIC “appears to favor only the interests of one political party” (National Public Radio 2023b).

The withdrawal of Republican-led states from ERIC was criticized as undermining efforts to maintain clean voter rolls, which is the primary purpose of ERIC and a goal that many Republicans support (Hicks et al. Reference Hicks, McKee, Sellers and Smith2015). Before leaving ERIC, many of these same political leaders praised the organization for maintaining election integrity. For example, the Ohio Secretary of State called ERIC “one of the best fraud-fighting tools that we have” (Kasler Reference Kasler2023), and Florida applauded ERIC for providing the data to identify hundreds who appeared to vote in multiple states (Florida Department of State 2024).

Journalists and the nonpartisan National Conference of State Legislators traced the decision to withdraw from ERIC to misinformation (Montellaro Reference Montellaro2023; Morse, Orey, and Bautista Reference Morse, Orey and Bautista2025; Underhill Reference Underhill2023). In early 2022, the right-wing website Gateway Pundit (2022) published a blog containing numerous criticisms of ERIC, including the accusation that ERIC was a “left-wing voter registration drive disguised as voter roll clean up.” As evidence, the blog argued that ERIC had been created largely by liberal donors, that ERIC had access to a vast amount of sensitive information collected by Department of Motor Vehicles offices in member states, and that there was little accountability regarding how the data could be used.

Importantly, for the purposes of this study, the Gateway Pundit also targeted ERIC’s policy of requiring states to contact EBUs, soliciting them to register, as an attempt to increase the number of Democrats on voter rolls. According to the blog, these efforts were tantamount to a “a left-wing voter registration drive all paid for by the States, not the Democrat Party” (Gateway Pundit 2022). In response, conservative activists began characterizing ERIC as “a covert method of registering targeted voters” (National Public Radio 2023a), and Donald Trump claimed that ERIC “‘pumps the rolls’ for Democrats and does nothing to clean them up” (Associated Press 2023). Missouri Secretary of State Jay Ashcroft bristled at the requirement that states contact EBUs, claiming that the mailings were going to people who “made the conscious decision to not be registered” (Montellaro and Fineout Reference Montellaro and Fineout2023). Similarly, a 2023 Heritage Foundation report argued that ERIC’s EBU outreach requirements were inappropriate because “voter registration efforts are handled most appropriately by political parties, candidates, and nonprofit associations, not the government” (von Spakovsky and Adams Reference von Spakovsky and Adams2023).

The perception that there are electoral consequences to state-initiated facilitation of electoral access is not new. Neither is support for or opposition to policies based on perceived political advantage. For instance, Biggers (Reference Biggers2019) showed that individuals are more likely to support electoral reforms when they are informed that the reforms will benefit their party. Similarly, Caron (Reference Caron2022) found that state legislators’ support (or opposition) to same-day registration is contingent on perceptions of an electoral advantage. Yet, the research on whether state-initiated registration and turnout efforts actually produce a partisan advantage is mixed and often challenging to conduct due to data limitations. The experimental data that this study contributes to the debate have numerous advantages over previous studies that largely draw on observational data.

In a study of Pennsylvania’s 2016 registration efforts, Bryant et al. (Reference Bryant, Hanmer, Safarpour and McDonald2022) found that state contact had a small but significant effect on registration, generating approximately 23,000 new registrants. The effects were strongest among young individuals who were voting in their first election. That these increases occurred during a contentious election in a hotly contested swing state suggests that state-led efforts can reach prospective voters who otherwise might abstain. Yet, no analysis has examined whether ERIC’s efforts produce a partisan electoral advantage, a central empirical criticism levied by ERIC’s conservative critics. Our investigation takes up this question.Footnote 1

THE PRESENT INVESTIGATION

Get Out the Vote (GOTV) campaigns are ubiquitous in American elections. Research has found that GOTV efforts increase turnout among those who are already registered to vote (Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2015; Michelson and Nickerson Reference Michelson, Nickerson, Druckman, Green, Kuklinski and Lupia2011). A smaller literature has examined attempts to encourage registration, often finding small but significant positive effects (Bennion and Nickerson Reference Bennion and Nickerson2016; Bryant et al. Reference Bryant, Hanmer, Safarpour and McDonald2022; Mann and Bryant Reference Mann and Bryant2020; Nickerson Reference Nickerson2015).

GOTV efforts often are conducted by candidates and parties with the goal of influencing election outcomes. However, nonpartisan organizations and state actors play a critical role by targeting hard-to-reach citizens who may be ignored by partisan organizations seeking only to mobilize friendly voters. The reputation of the messenger can affect how the message is received (Malhotra, Michelson, and Valenzuela Reference Malhotra, Michelson and Valenzuela2012); therefore, nonpartisan efforts may be especially effective (Herrnson, Hanmer, and Koh Reference Herrnson, Hanmer and Koh2019; Mann and Bryant Reference Mann and Bryant2020; Menger and Stein Reference Menger and Stein2018). Regardless of the nonpartisan goals of state-led registration efforts, could efforts to reach EBUs disproportionately benefit Democrats in elections, as some have speculated?

Some prior research suggests that there are meaningful differences between the preferences of voters and nonvoters, such that higher turnout benefits Democrats (Fowler Reference Fowler2015; Piven and Cloward Reference Piven and Cloward1988). Medenica and Fowler (Reference Medenica and Fowler2021) examined preferences in the 2016 election and found that nonvoting benefited Donald Trump more than Hillary Clinton. There are Republican politicians who frequently oppose laws that would expand voter registration, assuming that increased registration (and turnout) would benefit Democrats (Knack and White Reference Knack and White1998). In reality, however, the results are mixed. Some registration programs (e.g., agency registration) boost Democratic Party registration whereas other programs (e.g., motor voter and mail-in ballots) produce insignificant effects (Knack and White Reference Knack and White1998). Similarly, Wolfinger and Rosenstone (Reference Wolfinger and Rosenstone1980) suggested that increased registration does not significantly alter the partisan composition of the electorate.

Studies examining election reforms that relax voting requirements also have produced mixed results. Some studies have found that same-day registration increases turnout among Democrats (Berinsky Reference Berinsky2005; Burden et al. Reference Burden, Canon, Mayer and Moynihan2017; Hanmer Reference Hanmer2009; Hansford and Gomez Reference Hansford and Gomez2010; Ritter and Tolbert Reference Ritter and Tolbert2020), whereas others have found that reforms such as early voting help Republicans (Burden et al. Reference Burden, Canon, Mayer and Moynihan2017). Research also has shown that differential turnout between elections does not consistently benefit one political party (Citrin, Schickler, and Sides Reference Citrin, Schickler and Sides2003; DeNardo Reference DeNardo1980; Martinez and Hill Reference Martinez and Hill2007). Taken together, the research focusing on the United States is consistent with research in the United Kingdom, which found that large-scale reforms expanding the electorate did not yield partisan advantages (Berlinski and Dewan Reference Berlinski and Dewan2011).

Similarly, studies that examine sociodemographic proxies of partisanship suggest that registration efforts do not produce differential partisan advantage. Nickerson (Reference Nickerson2015) found that, although citizens in poor neighborhoods (who tend to lean Democratic) were more likely to register in door-to-door registration drives, those in wealthy neighborhoods (who historically tend to lean Republican) were more likely to vote once registered, thereby increasing participation among both the poor and the rich—though in different ways. Highton (Reference Highton1997) found that younger people (who lean Democratic) and less-educated people (who today tend to lean Republican) benefit more from Election Day registration because they are less likely to anticipate the need to register ahead of deadlines (see also Grumbach and Hill Reference Grumbach and Hill2022; Hanmer Reference Hanmer2009). In recent cycles, the Republican Party increased its support among irregular voters (i.e., those voting in half or fewer of the past four elections), with only 48% of irregular voters supporting the Democratic presidential candidate in 2024 (Catalist 2024). These trends give further credence to the possibility that encouraging turnout is unlikely to yield a distinct advantage for the Democratic Party.

For this investigation, expectations about the differential partisan effect of registration efforts targeting EBUs depend on two factors: (1) the partisan composition of “marginal” EBUs who might be swayed to register and vote; and (2) the differential appeal of state government communications among EBUs friendly to one of the two major political parties.

To evaluate the first factor, it is misleading to examine the preferences of voters compared to nonvoters. Long before Election Day, some citizens already have decided against registering. Others would have registered regardless of the state contact. The individuals of special note are the marginals—that is, those who are open to participating but who might not without contact from state officials. We do not expect these marginals to disproportionately support one party. They represent a small and idiosyncratic portion of the electorate, and the most comprehensive efforts to identify the short-term benefits of turnout have failed to reveal a benefit for either party (Shaw and Petrocik Reference Shaw and Petrocik2020).

We have similarly weak expectations regarding the differential partisan appeal of state communications. By definition, EBUs remain unregistered until two months before an election, which itself reflects a lack of political engagement. Furthermore, the messages in mailers from election officials under examination here are informational and nonpartisan.

Although the weight of prior research suggests that ERIC’s efforts should have helped Democrats and Republicans equally, the potential for differential effects remains an empirical question. The withdrawal of ERIC member states in the aftermath of partisan criticism prompts us to reanalyze data from 2016 field experiments to evaluate the merits of this question.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

To assess whether state-led efforts to register EBUs resulted in a partisan advantage for either political party, we analyze data from two 2016 randomized field experiments originally conducted to evaluate the effectiveness of ERIC states’ registration efforts: one in Pennsylvania and one in Nevada. The electorates of both of these ERIC member states were highly similar to the average ERIC member state on important dimensions, including age, sex, education, and income (see the online appendix for additional details on case selection). Both states also collect party registration data, which enables an analysis of whether the efforts produced a differential partisan advantage. Although party registration is distinct from partisanship, they are closely related (Thornburg Reference Thornburg2014). Moreover, this measure is suitable for this study concerning new registrations in the months immediately preceding an election because we would expect new registrants to select the party of the presidential candidate they support. This section reviews the 2016 field experiments and outlines our approach for estimating differential partisan effects (McDonald et al. Reference McDonald, Safarpour, Hanmer and Bryant2026).

PennsylvaniaFootnote 2

The 2016 Pennsylvania experiment began with 2,397,384 EBUs in data received from the Pennsylvania Department of Transportation. As an ERIC member, the state was required to contact 95% of EBUs; therefore, a random subset of 5% was assigned to a control condition. The 95% of EBUs who received a postcard informed them of their ability to register to vote. To enhance statistical precision (Nickerson Reference Nickerson2005), the randomization process was conducted in four blocks: (1) Philadelphia County (N=277,110); (2) Lehigh County (N=70,873); (3) Berks County (N=89,176); and (4) all remaining counties (N=1,960,225). The results present findings within each of these four regions (Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2015). Within each block, researchers grouped individuals by household and then randomly assigned them to either the control group or one of the four treatment groups.

The postcards informed recipients that they may not be registered to vote, emphasized the approaching deadline, noted that registration was “quick and easy,” provided a website to register online, and listed the eligibility criteria. The experiment varied content on the back of the postcards although all were politically neutral. In addition to the different postcards, subjects in the treatment group were randomized into two mailing waves to assess the importance of timing.

The results revealed low rates of voter registration among EBUs—slightly more than 8%Footnote 3; however, those in the treatment conditions registered at a rate approximately 1 percentage point higher than those in the control. The study further found a high vote yield—that is, for every additional new registrant created by the treatment conditions, there were 0.85 new votes cast. The treatment effect did not change based on variations in the postcard or the wave to which a participant was assigned; therefore, we differentiate participants in the following sections only by whether they were treated or not.

Nevada

The Nevada study followed a similar design to the Pennsylvania experiment and occurred contemporaneously. The study began with 206,722 EBUs from the Nevada Department of Motor Vehicles. Researchers grouped individuals by household and then randomly assigned them to either the control group or one of two treatment groups. Treated subjects received one of two versions of the postcard. Both versions included information about registration, and one provided a QR code to facilitate registration.

The results of the study mimic the Pennsylvania results. Overall registration rates were low (~5%), although the treatment significantly increased registration by approximately 0.8 to 0.9 percentage points and increased turnout by a similar margin of 0.8 percentage points. Treatment effects did not significantly differ based on variations in the postcard; therefore, we pool treatment conditions in the following analyses.

Analytical Approach for the Present Investigation

This investigation analyzes the 2016 experiments to determine whether efforts by these ERIC member states to reach EBUs provided a differential partisan advantage. First, we examine the partisan composition of new registrants in the treatment conditions relative to the control group. To evaluate whether ERIC’s efforts benefit Democrats to the detriment of Republicans, our analysis focuses on partisan registrants, excluding third parties and unaffiliated registrants.Footnote 4 If critics’ claims are true, we should find more Democrats than Republicans registered due to outreach efforts. Within strata (i.e., the regional unit in Pennsylvania and the entire state in Nevada), we calculate a treatment effect for the creation of new Republican registrants and assess whether we can statistically differentiate the effect from zero. To examine substantive significance, we also estimate how many new Republican and Democratic registrants were produced by outreach efforts. First, we compute the percentage of individuals in the control condition who registered with each political party. Second, we use those percentages to simulate how many Democrats or Republicans would have registered if control percentages held true among treated respondents. Third, for each party, we calculate the difference between the result in the second step and the observed number of new registrants in the treatment condition to obtain the estimated boost in voter registration for each political party. These analyses are summarized herein and detailed calculation tables are presented in the online appendix.Footnote 5

Second, we recognize that the treatments may encourage greater turnout conditional on registration. That is, individuals who register after receiving a postcard may be more likely to vote than individuals who register for other reasons. To investigate this possibility, we generate estimates of differential turnout among both Democrats and Republicans by comparing turnout in the control versus treatment groups for Democrats and Republicans, respectively. We regress a binary variable capturing turnout in the 2016 election (1=voted, 0=otherwise) on assignment to treatment (1) or control (0); Republican (1) or Democratic (0) partisanship; and an interaction between the two. The interaction represents the differential effect of the treatment on turnout for Republicans relative to Democrats. We also calculate the percentage of Republicans and Democrats in the control condition who voted to simulate how many Democrats or Republicans would have voted if those percentages held true in the treatment conditions. Regressions for Pennsylvania account for block randomization by including binary variables indicating each of the randomization blocks (Green and Gerber Reference Green and Gerber2015). For both states, we cluster standard errors by household to account for household-level randomization.

RESULTS

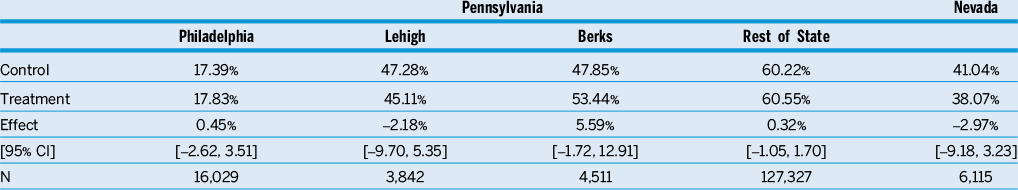

In both states, we find no significant difference in the percentage of new Republican registrants (table 1). Across the regions in Pennsylvania, estimated differences in Republican voter registration range from -2.18% to 5.59%, and none approach statistical significance. We find similar null results in Nevada. Among new major-party registrants in the control group, 41.04% registered as Republicans compared to 38.07% in the treatment group. This difference does not approach conventional levels of statistical significance.

Table 1 Percentage of Republican Registration by Treatment and Control (Two-Party Registration)

Note: CI = Confidence Interval.

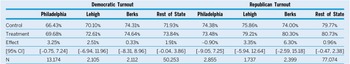

The registration results suggest that efforts by election officials did not have an appreciable effect on the partisan composition of the electorate in either state. With regard to turnout, in Pennsylvania, we find that both Democratic and Republican registrants in the treatment conditions are more likely to vote than those in the control. Democrats in the treatment conditions turned out at higher rates than Democrats in the control conditions across all four regions (table 2). Yet, none of these differences achieve conventional levels of statistical significance. Republicans in three of the four regions in Pennsylvania were more likely to turn out to vote if they registered after state contact; however, none of these differences is statistically significant (see table 2).

Table 2 Turnout Among New Registrants by Assignment to Condition and Strata in Pennsylvania (Two-Party Registration)

Note: CI = Confidence Interval.

Statistical tests revealed no evidence that the boost in turnout, conditional on registration, was stronger for Democrats than Republicans. This interaction was indistinguishable from zero (p=0.54), which suggests that both Democratic and Republican registrants behaved similarly.Footnote 6

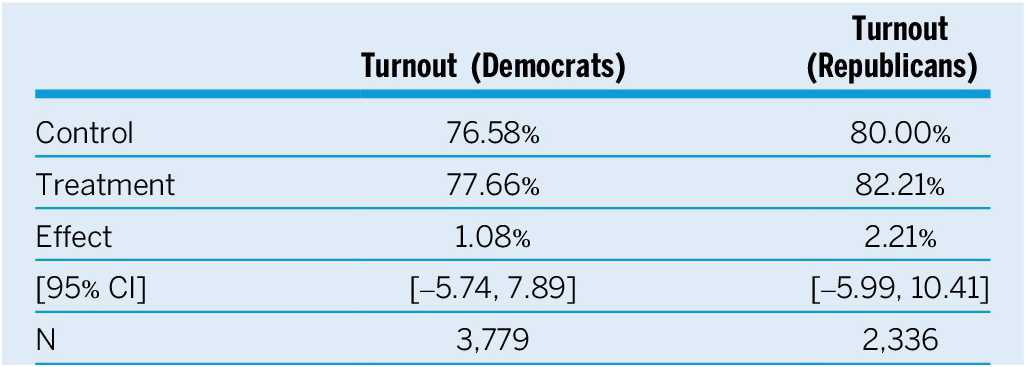

In Nevada, we find modest increases in turnout among both Democrats and Republicans, yielding little partisan advantage (table 3). Democrats in the treatment conditions voted at higher rates than Democrats in the control group by 1.1 percentage points. Republicans in the treatment conditions also voted at higher rates than Republicans in the control group by 2.2 percentage points. The effect, although slightly higher for Republicans than Democrats, was not statistically significant (p=0.84).Footnote 7

Table 3 Turnout Among New Registrants by Condition in Nevada (Two-Party Registration)

Note: CI = Confidence Interval.

Summary of Differential Partisan Effects

Although the results show statistically insignificant differences between Democrats and Republicans, skeptics may note that a failure to reject the null hypothesis of no difference is not the same as confirming the null.

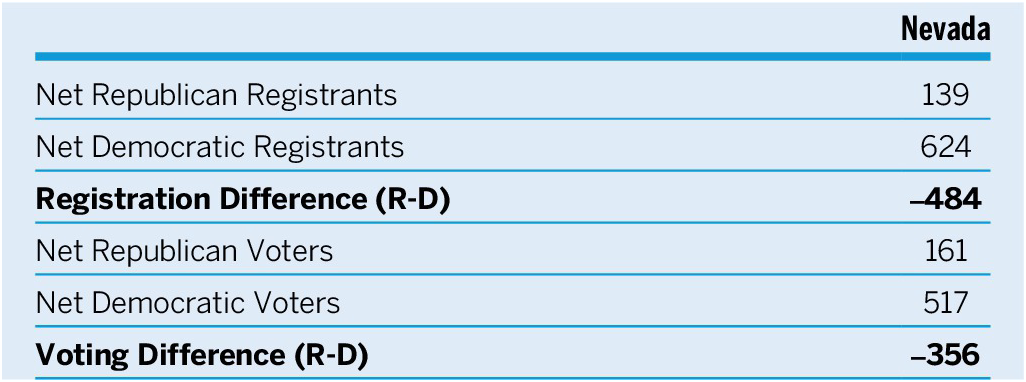

To contextualize these findings, tables 4 and 5 present the estimated number of new registrants and voters for both parties and demonstrate that—even ignoring statistical significance—the number of new registrants and voters would not have changed the 2016 outcome in either state.

Table 4 Summary of Differential Partisan Advantage in Pennsylvania

Table 5 Summary of Differential Partisan Advantage in Nevada

In Pennsylvania, the treatments boosted Republicans more than Democrats (see table 4). The estimates show that Republicans gained 11,445 registrants and 9,962 voters, whereas Democrats gained 8,308 registrants and 7,252 voters. Although this suggests a slight Republican advantage, it is noteworthy that there were approximately 2.4 million subjects in this study, statistical analyses suggest the mailers did not significantly interact with recipients’ partisanship, and Donald Trump won Pennsylvania by more than 44,000 votes. Altogether, the net difference of approximately 2,700 additional Republican voters is substantively and statistically inconsequential. The race for Attorney General was decided by a difference of 165,776 votes, with Democrat Josh Shapiro winning the election, and other statewide elections were decided by even wider margins.

Differences in Nevada are especially modest (see table 5). We estimate that Republicans gained 139 registrants and 161 voters whereas Democrats gained 624 registrants and 517 voters. Viewed in the context of the more than 27,000-vote margin for Hillary Clinton, there is little evidence that the mailers affected the election outcome.

DISCUSSION

This study assessed the potential for partisan advantage in state-led EBU voter registration efforts, yielding two important findings. First, efforts by Pennsylvania and Nevada to contact EBUs ahead of the presidential election increased registration but did not disproportionately benefit either major political party. The differences across party registration between experimental conditions were statistically insignificant and substantively small. Second, turnout among registrants did not significantly differ by partisanship. Our best estimates suggest that ERIC’s efforts did not consistently favor either party or affect the election outcome in either state. These findings are inconsistent with the partisan criticism leveled against ERIC and its member states.

This study complements research suggesting that marginal voters who could be persuaded to vote are similar to more habitual voters (Shaw and Petrocik Reference Shaw and Petrocik2020). In presidential elections, the campaigns and political parties are likely to contact friendly voters and persuade them to turn out, but state election officials are contacting new or relatively unengaged voters who do not consistently favor one party.

Although this study explored voter registration and turnout in two competitive swing states in a major election, some limitations merit attention. Because we explored results in only two states in a single election, we cannot predict how state-run registration efforts would operate in other contexts. Results may differ in uncompetitive states where political parties are less active. Additionally, we only examined states with party registration, and we did not directly observe voting behavior; therefore, we had to infer the choice of new registrants based on party registration.

Finally, some may still view the efforts of ERIC member states to reach EBUs as not meriting the costs associated with such outreach. Prior research on these efforts (Bryant et al. Reference Bryant, Hanmer, Safarpour and McDonald2022) estimated that the postcards cost between $0.20 and $0.50 per EBU, suggesting a price tag of $19.19 to $47.97 per additional registrant and $22.56 to $56.39 per additional voter. These costs are significantly less expensive than the $91 cost-per-voter via direct mail estimates by Green and Gerber (Reference Green and Gerber2015). Whether these costs are justified is a normative rather than empirical question, and our focus has been to assess whether outreach efforts disproportionately benefit one party over another.Footnote 8 However, as stated at the outset of this article, high civic engagement increases perceptions of democratic legitimacy—a cause well worth the cost in our opinion. This view is consistent with the opinion of many other political scientists (e.g., Verba and Nie Reference Verba and Nie1972) and consistent with the notion that legitimacy rests on the consent of the governed as expressed through regular elections. Indeed, the Constitution’s framers characterized the central feature of government as constraint through elections, noting, “The elective mode of obtaining rulers is the characteristic policy of republican government,” with leaders selected by “the great body of the people of the United States” (Hamilton Reference Hamilton1788).

Taken together, our results reaffirm the value of state-led efforts to reach unengaged citizens who might be willing to participate in the civic process if they are invited. Although these efforts may be vulnerable to criticism, assessing the validity of such criticism is paramount. Our evidence indicates that this criticism lacks basis. Government officials serve a unique role in the GOTV effort because they have the means to target those who lack a voting history and may be more trusted than partisan organizations. Proponents of clean voter registration lists and higher turnout would argue that ERIC has a crucial role to play in registration efforts, serving as a model for how to assist states in maintaining the integrity of the voter rolls (Morse, Orey, and Bautista Reference Morse, Orey and Bautista2025) and aiding in the identification of people who are eligible but have not registered to vote.

Government officials serve a unique role in the GOTV effort because they have the means to target those who lack a voting history and may be more trusted than partisan organizations.

SUPPLEMENTARY MATERIAL

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1049096525101819.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

Research documentation and data that support the findings of this study are openly available at the PS: Political Science & Politics Harvard Dataverse at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/YDQ7WH.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

Support for the original project was provided by The Pew Charitable Trusts (Grant No. 29785). The views expressed herein are those of the authors and do not necessarily reflect the views of The Pew Charitable Trusts, the states in the study, or ERIC; neither was this analysis requested or approved by any of those entities. Data for the original project were provided by the states of Pennsylvania and Nevada. No additional funding or data were provided for this article. Any errors are our own.

CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Authors McDonald, Safarpour, and Hanmer do not have any competing interests relevant to this research. Author Bryant is currently on the research advisory board of ERIC; however, she did not hold this position when the original experiments analyzed in this article were conducted.