Introduction

One quintessential goal of the slavery reparations movement is to secure formal state apologies from perpetrator states.Footnote 1 The Netherlands was the first European state to offer such an apology. Former Dutch Prime Minister Mark Rutte noted: ‘no government in the world, as far as we know, has done that [offered apologies for slavery]’.Footnote 2 Rutte’s observation is largely accurate but requires two clarifications. First, several non-European countries, most notably Benin, have publicly acknowledged and apologized for their historical involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. In particular, Benin’s president, Mathieu Kérékou, sought forgiveness in 1999 as part of a broader reconciliation initiative.Footnote 3 Second, and crucial to this article’s comparative analysis, no other European government had issued a sovereign, state-level apology for transatlantic slavery as of 3 September 2025. The Netherlands’ apology in December 2022 thus stands as the first officially issued executive and parliamentary apology by a European state, rather than a mere local government declaration or symbolic gesture.Footnote 4 This renders the Dutch case seemingly unique. Contemporary scholarship on state apologies, however, indicates that we are living in an ‘age of apology’, where states are increasingly acknowledging and expressing some form of remorse for historical human rights violations.Footnote 5

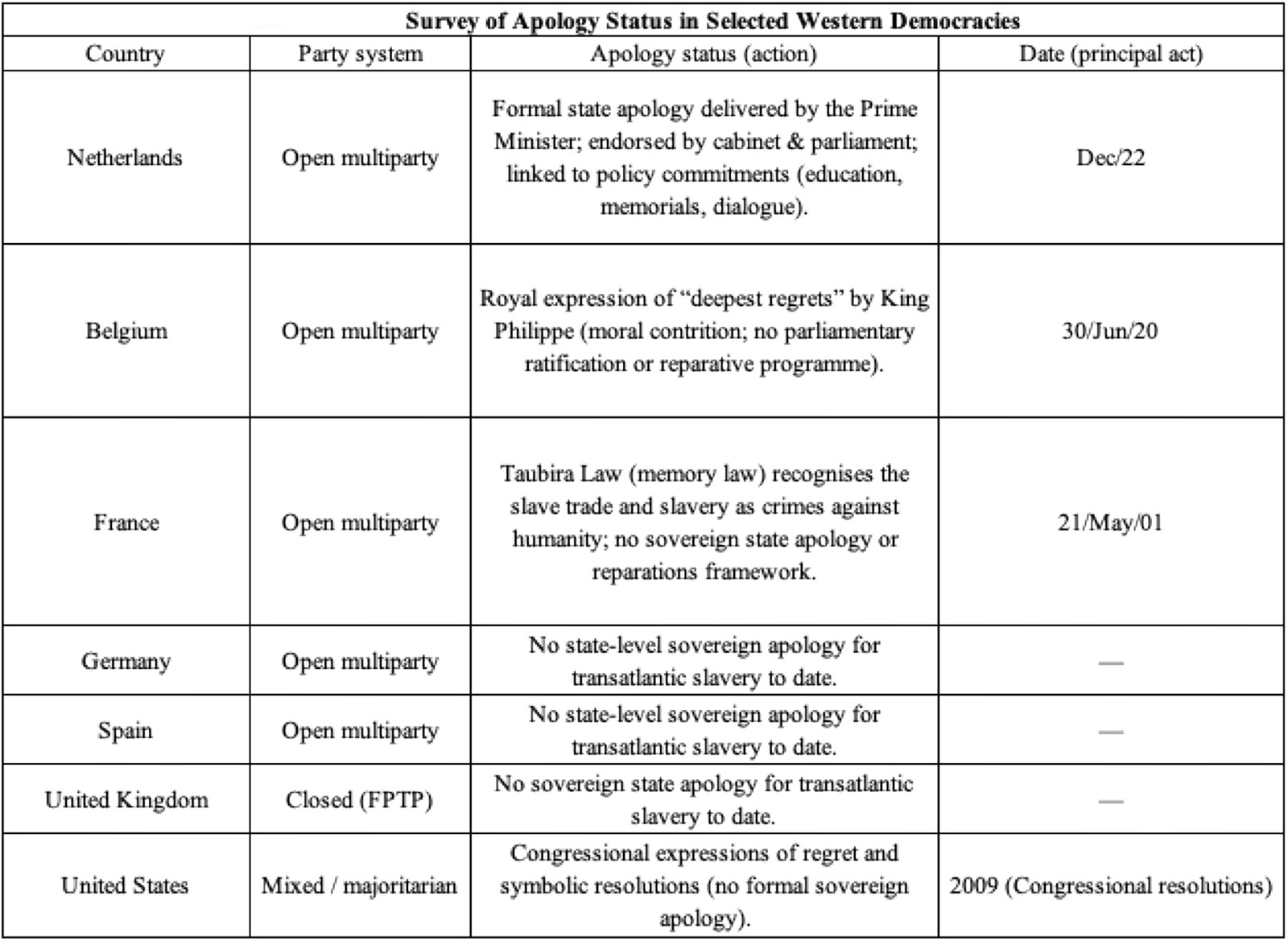

European states have shown varying levels of engagement with formal acknowledgements of slavery and colonialism (see appendix A). In contrast to the Netherlands, Belgium’s King Philippe, in June 2020, limited his response to a personal letter expressing ‘deepest regrets’ for colonial abuses in Congo, without parliamentary backing or concrete frameworks for reparative actions. Meanwhile, several French overseas assemblies have only extended local government apologies. Major European powers like the United Kingdom, Germany, and Spain have remained silent, despite CARICOM’s 2014 call for state-level redress and ongoing transnational advocacy.Footnote 6 Unlike Belgium’s symbolic royal regret, the Dutch apology was delivered as a formal speech by the Prime Minister, endorsed by both the cabinet and Parliament, and reiterated by the king as the highest state representative. This apology is explicitly tied to educational programs, memorialization efforts, and structured dialogue with descendant communities, making it unprecedented in Europe and uniquely capable of transforming symbolic acknowledgement into tangible institutional commitment.

This raises an important empirical and theoretical puzzle: why have most European states, including the UK, resisted apologizing for their role in slavery, despite the broader discursive trend of official contrition for past injustices? This article addresses this puzzle by examining why the Netherlands appears to be the only European state to have issued a formal apology for slavery. It contrasts the Dutch case with the United Kingdom, where the government has expressed ‘remorse’ and ‘sorrow’ but has repeatedly refused to offer an official apology despite sustained calls for one.Footnote 7 Thus, this article investigates how the anti-slavery norm – the emerging imperative that states publicly acknowledge and regret their participation in the transatlantic slave trade – takes root, and it analyzes the specific domestic coalitions and political opportunity structures that transform this moral expectation into a formal state apology. A state apology is a sovereign speech act in which a government formally acknowledges its institutional responsibility for past injustices and expresses public regret, thereby signaling official accountability in both domestic and international arenas. Unlike apologies issued by subnational authorities, corporations, or private entities, only a sovereign apology carries the weight of state commitment under international norms and can recalibrate inter-state relations and global expectations.

The central argument posits that state apologies for slavery are driven more by domestic political conditions than by international norms or external pressure. Applying process-tracing through an analytically eclectic explanatory framework, this study identifies three critical factors that enabled the Netherlands’ apology but which were absent in the UK: (1) an open political system receptive to new parties and minoritized voices, (2) influential domestic allies supporting the apology movement, and (3) a well-defined victim group with strong domestic representation. These elements made an official apology politically viable in the Netherlands. The analysis also challenges the assumption that international allies always strengthen reparations movements, demonstrating that external support can sometimes complicate the process leading to an apology. This account is called the apology activation model (AAM), which explains the Netherlands’ 2022 sovereign apology as the result of three mutually reinforcing mechanisms: open institutional opportunities, convergence of elite and societal interests, and strategic localization of transnational pressure into forward-looking policy packages, which together transformed movement mobilization into parliamentary motions and executive action.

This article makes a significant contribution to the existing scholarship and public debates on state apologies and slavery reparations. It offers the most comprehensive analysis to date of the Netherlands’ formal apology for slavery, an event that has thus far received limited sustained attention in the apology literature. The article challenges the prevailing tendency to treat the study of state apologies as separate from reparations scholarship. By demonstrating that domestic political factors influence the likelihood of an apology, this work advocates for an integrated framework that situates apologies within broader reparative processes. Additionally, it presents a novel application of social movement theories to reparations politics, illustrating how grass-roots mobilization and elite alliances interact to effect state-level changes. Our analysis contributes to the literature on the politics of slavery reparations by explaining state behaviour in response to demands for historical justice and the conditions under which reparations movements succeed in securing formal apologies.

This intervention is necessary because dominant theories of state apologies are unable to fully account for the absence of European slavery apologies, despite the alleged broader ‘age of apology’.Footnote 8 The literature review here critically engages with these limitations, arguing that existing models, which often focused on post-conflict reconciliation or international relations, overlook the role of domestic contestations in shaping apology politics. In redress of this neglect, the following sections develop a theoretical framework that synthesizes insights from social movement theory, reparations literature, and comparative politics. The plausibility of this framework is then probed through a process-tracing analysis of the Dutch and British cases, assessing its explanatory power in accounting for divergent outcomes. The comparative analysis concludes by evaluating the framework’s strengths and limitations and outlining directions for future research on the intersection of apology, reparations, and historical justice.

In addition, it is essential to acknowledge the analytical scope and limitations of this study. The three key factors identified in the Netherlands’ apology – an open political system, influential domestic allies, and a well-defined victim group – are not claimed to be universally applicable as a blueprint for securing state apologies. Rather, these factors emerge as analytically useful categories abstracted from social movement theory and tested against the empirical realities of this illustrative case. The Dutch experience provides an important case for refining theoretical expectations, but further comparative research is needed to assess whether similar processes hold in other contexts. This study, therefore, is not making a universal claim about the conditions under which all states issue apologies for slavery; rather, it argues that existing theories require enhancement to better account for how domestic political dynamics interact with reparations movements. This calls for further empirical investigation across different cases, particularly in countries where similar movements have not yet succeeded in securing formal state apologies.

To sharpen our theoretical focus, it is crucial to define what constitutes an ‘apology’ in this context. Although scholars vary in their definitional rigour, an excessively rigid ideal-type may exclude cases that still offer valuable insights. A basic form of consensus, however, exists: most definitions recognize an apology as containing at least two core elements – an expression of regret and an admission of responsibility or guilt.Footnote 9 Expressions of regret alone are insufficient, as they can be delivered without meaningful accountability. What transforms a statement into an apology is the explicit admission of responsibility: an acknowledgement by the perpetrating entity that it was culpable for historical injustice.Footnote 10

This distinction is particularly salient in the case of slavery apologies. Many states have expressed regret, sorrow, or lament over the historical reality of slavery.Footnote 11 Yet these statements have been categorically rejected by affected communities as insufficient precisely because they stop short of admitting guilt.Footnote 12 The crucial act of assuming guilt distinguishes an apology as a performative speech act, one in which the very utterance constitutes an acceptance of responsibility.Footnote 13 The apologies analyzed in this study are those made at the state level, typically by the head of government or head of state. Since lower-ranking ministers also represent the government, a state apology can be delivered by a minister acting officially. We define a state apology as a speech act issued by the state that acknowledges responsibility for a historical wrongdoing and expresses regret.

The national debates on a slavery apology

The Dutch debate leading up to the apology has been traced back to the expression of remorse at the 2001 World conference against racism in Durban. Monetary reparations were not deemed a ‘proper’ solution though, the government instead preferring investments in awareness of the slavery past and the ‘active citizenship’ of affected groups.Footnote 14 As Nicole Immler points out, creating awareness and generally improving the relations between the minoritized descendants and the majority population has become the focus of the reparations debate within the Netherlands, de-emphasizing direct monetary reparations.Footnote 15 The Durban moment ran parallel to a descendent-led campaign for a national monument for the history of slavery, which was unveiled in 2002.Footnote 16 Since then, the slavery debate in the Netherlands has focused more on its manifestation in everyday occurrences of racism. As will be elaborated below, the Dutch debate around Zwarte Piet, a traditional character in St. Nicolas celebrations, and Black Lives Matter saw this view becoming more prominent in society. In quick succession, Dutch cities started apologizing in 2021 and 2022, with the Dutch PM following in December 2022 and the king in July 2023. The apology saw mixed reactions. In the Netherlands it was seen as a symbolically significant event but advocacy groups reiterated demands for more substantial reparations and critics had a ‘wait and see’ approach towards Rutte’s allusion to further government efforts to relate to the Dutch slavery past.Footnote 17 In the Caribbean parts of the kingdom and Suriname, the apology was received with a mixture of disinterest and scepticism.Footnote 18

In the UK the debate has a longer trajectory. Already back in 1993, MP Bernie Grant raised the issue of reparations for enslavement in Parliament.Footnote 19 In 1999 Liverpool became the first British city to apologize, two decades ahead of Amsterdam, the first Dutch city to do so. Jessica Moody in her analysis of this moment, explicitly links this event to the ‘wave of apologies’ during the 1990s. Consequently, it was an apology informed by both local and international influence and staged with a global audience in mind.Footnote 20 Its domestic impact seemed limited as it took until the bicentenary of the abolition of slavery in 2007 for other apologies to materialize.Footnote 21 At the national level, PM Tony Blair famously went no further than expressing ‘remorse’ at this occasion. While there has been broad and rising popular support for a full national apology, 56% in 2024 compared to 38% in 2021 in the Netherlands,Footnote 22 Blair’s statement has been the official government position ever since. Additionally, Britain also faces significantly more international voices calling for apologies. Most recently, at the 2024 Commonwealth summit, Prime Minister Starmer was faced with pressure to adjust his initial position that reparations in any form were ‘not on the agenda’ and accepted that there was a need for ‘meaningful, truthful and respectful conversation towards forging a common future based on equity’.Footnote 23 It highlights the observation by Evans and Wilkins that international actors play a particularly important role in the British debate.Footnote 24 The British case for slavery apologies thus enjoys both more popularity at home and more support internationally.

Norm theory and state apologies: Dominant but lacking

We can now return to the question introduced above: why do states apologize? As has also been noted by Daase et al., there is a relative lacuna in theorizing on this question.Footnote 25 Most contributions instead engage with the question of what the effects of apologies are when given. Moreover, the contributions that do relate to the ‘why’ question provide answers that are meant to explain the ‘wave of apology’ that has been observed in the Western world. This has yielded explanations that tie apology to developments such as the third wave of democracy, a rise in progressive identity politics, a democratization of history, or a changing cultural acceptance of victimhood.Footnote 26 However, the most persistent are contributions that base themselves on constructivist norm theories.

The role of norms in state apology research can be traced to Nicholas Tavuchis’ book Mea Culpa, which explored apologies as expressions of the ‘normative principles of social life’.Footnote 27 In line with this, Bentley argues that the rise of international norms has encouraged states to ‘rummage through their pasts’ to reconcile themselves with historical norm violations.Footnote 28 There are various interpretations of how norms, which can be defined as ‘rules or normative principles that are somehow accepted in and by particular groups’, influence state behaviour in constructivist norm theory.Footnote 29 Some theorists argue that external ‘punishment’ for norm violations compels compliance.Footnote 30 Others suggest that norms influence state behaviour through self-interest, either by incentivizing conformity or by reshaping perceived self-interest.Footnote 31 A third position emphasizes norm internalization, where norms become part of a state’s identity.Footnote 32 As apologies for past violations became common, scholars argued that offering such apologies has itself become a norm.Footnote 33 Classic norm theory posits that states can act on normative principles with minimal domestic support, making it a parsimonious framework for explaining state behaviour.Footnote 34

Applications of the norm internalization model to political apologies, such as by Wolfe and Löwenheim, seek to explain why states apologize by emphasizing the different phases of norm adoption states find themselves in.Footnote 35 Turning to our cases we can indeed see that they both have some history with offering expressions of remorse and apologies. However, the UK offered apologies and other expressions of self-reproach more often, offering a total of 24 since 1997, while the Netherlands counts 16, starting only in 2001.Footnote 36 Importantly, slavery apologies are clearly not included in this trend yet. This is despite most Western states having ‘condemned’ and ‘regretted’ slavery as ‘massive human suffering’ or similar, such as during the 2001 World Conference against Racism.Footnote 37 What is more, international pressure on the UK to translate this norm into a form of reparations is arguably stronger than on any other state, certainly the Netherlands. This is because of its status as the former colonial ruler of a large number of both African and Caribbean states, thereby facing pressure from bodies such as CARICOM but also the Commonwealth.Footnote 38 Therefore, having a less extensive history with apologies than others and facing less intense international pressure to offer one for slavery, the theory thus formulated struggles to explain why the Netherlands stands alone in offering an apology for slavery.

Social movement theories: Reframing apology as reparations

An approach is needed that acknowledges state behaviour is not solely determined by the international sphere. Unlike norm theory, social movement theory highlights domestic opportunity structures and local actors, bringing attention to the agency of minoritized groups and their influence on decision-making. Social movements are described as ‘a collection of formal organizations, informal networks, and unaffiliated individuals engaged in a more or less coherent struggle for change’.Footnote 39 Through this perspective, slavery reparations emerge as a movement led by survivors or their descendants. Although these movements encounter reluctant states, social movement theories recognize the potential for change through grass-roots advocacy.Footnote 40

Howard-Hassmann and Lombardo’s (2008) book Reparations to Africa applies this theory to political apology from the social movement’s perspective. The authors analyze the reparations movement for historic human rights abuses in Africa and identify success criteria.Footnote 41 Their analysis emphasizes societal mobilization through legitimacy and resonance across moral, legal, and political dimensions. Key criteria include clear demands, influential allies, and an identifiable claimant group.Footnote 42 Their framework, however, focuses mainly on epistemic power and societal support, thereby leaving political structures underexamined. While society might be swayed by a movement’s narrative and moral righteousness, systemic constraints can hinder converting these pressures into action.Footnote 43 Despite higher public support for a slavery apology the UK has not apologized, suggesting societal mobilization alone struggles to achieve state apologies. The Dutch slavery apology poses two challenges: other states have internalized the anti-slavery norm and face more international pressure, and they have more public support. Why then did the Netherlands apologize while others did not?

Apology activation model: Theory and methods

This explanatory framework seeks to address these questions more effectively than existing models by integrating social movement and norm theories, thereby emphasizing a crucial insight from both: decisive processes occur at the local level. The AAM specifies a concise causal sequence for process tracing. First, transnational advocacy and persuasive frames are localized to fit national meanings.Footnote 44 Second, domestic allies and elites translate localized frames into policy proposals. Third, interest convergence aligns reputational or material gains with elite incentives and societal demands.Footnote 45 Finally, institutional openings (party access, coalition flexibility) provide the channel through which a sovereign apology becomes politically executable. The analysis traces these steps in sequence.

While Howard-Hassmann and Lombardo (2008) adopt a transnational perspective, social movement theory (SMT) has traditionally concentrated on the domestic arena. Classic norm theory highlighted international norms and advocacy networks. However, Amitav Acharya introduced the concept of ‘localization’ of international norms, illustrating how political elites tailor transnational norms to align with domestic priorities, thereby reshaping global expectations in terms that resonate locally.Footnote 46 Recognizing the significance of the local sphere, this framework uniquely merges insights from social movement theory with advancements in norm theory, theories of justice, and interest convergence theory to demonstrate how moral norms, material incentives, and strategic coalitions prompt sovereign apologies. Our framework reveals that when domestic opportunity structures – characterized by institutional openness, cohesive victim groups, and influential allies – align with elite interests and forward-looking framing, formal state apologies become politically feasible. This analytically eclectic framework synthesizes these elements – blending normative, strategic, and institutional perspectives – to elucidate how global moral demands translate into sovereign state action.Footnote 47 To fortify the theoretical foundation, this section expands on the literature review by refining key definitions, outlining theoretical background, and clarifying premises.

Building on the literature review, this section reiterates the definition of a state apology as a speech act uttered in the name of a state which both accepts responsibility for a wrongdoing and expresses regret for it. The subject of this apology is the European history of transatlantic slavery, involving the trade in and forced labor of African people between the 16th and 19th centuries. It is the combination of these elements: the utterance of both regret and responsibility on the highest state level for slavery which makes the Dutch case unique. Only the apology by Benin checks all these boxes, but no European state, or indeed any other state, can say the same. An apology can be conceptualized as a form of reparations, aligning with reparations literature and introducing analytical methods from this field. Reparations, broadly defined, refer to measures taken by states or institutions to acknowledge, redress, and compensate for historical injustices and harms.Footnote 48 While reparations often include material compensation, such as financial restitution or legal reforms, symbolic gestures like apologies constitute the minimum form of redress, serving as official recognition of wrongdoing and a foundation for broader reparative efforts. By embedding apology within reparations discourse, we situate it not as a mere performative act but as a crucial component of transitional justice and historical accountability.

Political opportunity structures

Building on the ideas from Howard-Hassmann and Lombardo,Footnote 49 who adopted a bottom-up social movement perspective, this study challenges their claim that strong social movements alone secure reparations. As seen in the UK, widespread public support does not always translate into political action.Footnote 50 Insights from Sidney Tarrow’s Power in Movement refine this perspective by emphasizing the importance of political opportunity structures, external conditions that shape a movement’s success beyond mass mobilization.Footnote 51 Specifically, we highlight the importance of political openness. This variable assesses a system’s receptiveness to new parties, ideas, and social movements. Its key indicators include: the entry of new parties into Parliament, shifts in government coalitions, and the extent of policy innovation within parties.Footnote 52 A more open system facilitates a movement’s access to decision-making, while in a closed system, even a strong reparations movement may fail to secure an apology.Footnote 53

Strategic domestic allies

The second variable, influential allies, is closely related to political openness but whereas the previous variable operates more on a structural level, this variable explicitly takes agents into view. In line with Acharya’s model of localization, local allies within government and broader societal institutions can act to diffuse norms and accommodate local sensibilities even pressuring legislators or advocating for the movement.Footnote 54 The Dutch case saw issue-owners like political party BIJ1 slowly gathering support from influential actors that initially stood further away from the cause. For actors that are not as deeply integrated with the victim community like BIJ1, Regilme’s interest convergence theory grants us a powerful tool to understand these actors and not only signal their presence or absence but also generate some insight into what motivated them to support an apology.Footnote 55 This theory, as applied in the analysis of foreign aid and human rights, argues that states comply with international norms only when influential domestic and transnational elites – and their allied civil‐society and multi-stakeholder coalitions – perceive overlapping normative and material gains.Footnote 56 In reference to Acharya, Regilme develops the key mechanism of strategic localization. Applied to apologies, this means that local actors and elite coalitions strategically customize and reframe transnational demands for reparations and historical justice, consequently presenting formal acknowledgements of wrongdoing in terms that effectively resonate not only with domestic identity and norms but also material interests to transform them into effective instruments of elite buy-in and political legitimacy. This thus adds a materialist dimension to Acharya’s theory,Footnote 57 for example, by mobilizing voting blocs to sway political action as will be developed in the next variable.

Cohesive and mobilized victim group

Thirdly, there is the victim group itself. This variable too cannot be fully separated from the others in this framework. An actor like the BIJ1 party represents the victim group as an ‘ally’ but its members are often part of the victim group itself and use this to add personal insights and illustration in their push for an apology. The importance of a coherent and politically mobilized victim group is stressed both in social movement theory and later iterations of norm theory like Acharya’s.Footnote 58 Howard-Hassmann and Lombardo stress the need for a clearly and coherently defined perpetrator, harm, claim, and victim group.Footnote 59 If any of these are unclear or tenuously related to the other elements, opponents can undermine the reparations claim.Footnote 60 From the perspective of norm localization, a similar importance is granted to victim groups.Footnote 61 A victim group that is both large and politically relevant is better positioned to achieve a framing of the apology as an act that is coherent with the contemporary normative and identity framework of the society in question. Regilme’s interest convergence theory adds a dimension to this. When a victim group represents a significant voting bloc or exerts notable societal influence this can sway politicians’ interest calculations. This is especially true when this group is able to promote a coherent claim and make it resonate in society, which will be addressed in the next variable. Therefore, if a group is large enough to matter as a voting bloc and united enough to speak with an identifiable voice, they are more likely to attain an apology for slavery.

Framing and forward-looking claims

Both Regilme (2021) and Acharya’s (2004) localization theory place special emphasis on the power of framing.Footnote 62 Similarly, Antje Wiener’s theory of norm contestation stresses that norms are not self-evident mandates but are continuously renegotiated through discursive battles over their meaning and scope.Footnote 63 As discussed, this comes down to framing the international norm in such a way that it is in line with local norms, identities, and general sensibilities. We can refine this with insights from the transnational justice literature. Recognizing that retrospective blame often stalls state action, forward-looking justice theorists reconceptualize apologies as instruments for remedying ongoing structural harms. Leif Wenar’s compensation model (2006) argues that reparative gestures should secure today’s victims’ rights by channeling resources into institutions that redress inequality, thereby transforming apology into a pragmatic investment in social repair.Footnote 64 Catherine Lu’s reconciliation framework complements this by emphasizing apologies as foundational steps in rebuilding trust and shared citizenship, thereby framing regret not as fault‐finding but as a commitment to preventing present and future injustices.Footnote 65 Together, these perspectives shift the apology’s logic from assigning historic blame to mobilizing collective responsibility for the enduring legacies of past wrongs.

From this we can draw two key insights. First, the problem of slavery has to be framed as a current issue, not solely an event in history books but a human rights violation with ongoing detrimental impacts. This can be done through what Howard-Hassmann and Lombardo call condensation symbols: concrete events or figures illustrating (continuing) historical injustices.Footnote 66 Think of George Floyd and the Black Lives Matter movement, or the emerging movement against the systemic labor exploitation and environmental damages caused by the artificial intelligence industry.Footnote 67 Second, the reparations in question, the apology in this case, has to be framed as a future-oriented solution to these ongoing negative effects. For example, in the Dutch case we see that reparations are explicitly framed as strengthening the victims’ position as full and equal citizens in a constitutional democracy. This is something which resonates heavily with key values which are widely shared in Dutch society and form part of its self-image.

Method

This study utilizes process tracing to systematically identify the sequence of macro-processes leading to an outcome.Footnote 68 The theoretical framework examines the factors hypothesized to have prompted the Dutch state to apologize for slavery. To operationalize this framework and clarify our process-tracing tests, we concentrate on four proximate causal variables that collectively establish the political conditions for a sovereign apology: (1) political opportunity structures (openness) – the institutional receptiveness of the party system to new parties, ideas, and minority voices; (2) strategic domestic allies – high-capacity actors within state institutions (MPs, ministers, municipal leaders) and influential societal elites who can translate mobilization into policy; (3) cohesive, mobilized victim constituency – a clearly identifiable claimant group with domestic representation and organizational capacity; and (4) framing and forward-looking claims – persuasive narratives that reframe apology as a future-oriented instrument for addressing present structural harms. Each variable is associated with clear, observable indicators (below) that our process-tracing follows through parliamentary records, public statements, policy initiatives, and organizational activity. These indicators enable a falsifiable test: the hypothesized mechanisms should be present and sequenced in the Netherlands (where an apology occurred) and weak or absent in the United Kingdom (where it did not). (See Figure 1 below for a concise summary of indicators and where evidence is discussed in the manuscript.) Process tracing evaluates the AAM by requiring empirical evidence that strategic localization of norms is followed by elite convergence, which triggers coalition activation and culminates in institutional enactment, and it accepts the mechanism only when that ordered sequence rather than mere co-occurrence is observed.

Figure 1. Summary of observable indicators - apology activation model.

To evaluate our framework and explore the inferences, we incorporate process tracing within a most-likely/least-likely case design.Footnote 69 The Netherlands serves as a ‘most-likely’ case for an anti-slavery apology due to its open, multi-party system, a cohesive Surinamese-Caribbean constituency, and domestic allies that include both issue-owner parties and mainstream actors. In contrast, the United Kingdom represents a ‘least-likely’ case, characterized by a first-past-the-post political system, fragmented victim groups, and a lack of allies with political decision-making power, which, according to our theory, should prevent a formal apology. Both countries share a similar colonial history in the Atlantic slave trade, maintaining a constant moral claim for reparations. By selecting these two extremes concerning the relevant variables, we create a rigorous test: if our comparative analysis of party politics, civil society dynamics, and framing mechanisms can explain divergence in these cases, they hold strong explanatory power for broader European contexts.

Cases

The Netherlands and the United Kingdom both have extensive histories in the transatlantic slave trade, making them directly comparable on the moral demand for apology. Dutch ships transported over half a million enslaved people globally.Footnote 70 Slavery under Dutch control covered Suriname, Guyana, Aruba, Curaçao, Bonaire, East Asia, and South Africa and was formally abolished in 1873.Footnote 71 The British history of slavery involved the trade and dehumanization of over 3.25 million people between 1501 and 1807.Footnote 72 Its plantation economy spanned North America and the Caribbean, including Jamaica, Grenada, and Guyana, abolishing it in 1833.Footnote 73 Despite this shared legacy, the Netherlands became the first European state to issue a formal slavery apology in 2022, while the UK has consistently refused to do so despite persistent advocacy. This divergence makes the pair a strong candidate for a most‐likely/least‐likely case design.

Findings

The openness of the political system

The openness of a political system is crucial for social movements seeking state apologies. In the Netherlands, small parties advocating reparations entered politics and kept the issue on the agenda. The UK’s first-past-the-post system and party discipline concentrate power in dominant parties, making it difficult for minor formations to gain parliamentary representation – a structural obstacle for reparations politics. The Dutch multi-party system enables representation of minoritized voices, with 16 parties in Parliament after 2023 elections, thereby exceeding the European average despite having 150 seats.Footnote 74 Among Western states with a slave trading history, only France has more parties. Notably, Peter Mair concludes that the Dutch system is ‘exceptionally open to new parties’,Footnote 75 based on innovative government formulae and electoral design. Although major parties often remain in governing coalitions,Footnote 76 the Dutch system remains particularly open to new voices.

This openness facilitated the entry of parties like DENK and BIJ1, which played key roles in advocating for a slavery apology. DENK, founded in 2015 after a split from the Labour Party (PvdA), called for a state apology as early as 2017.Footnote 77 BIJ1, founded by former DENK member Sylvana Simons in 2016, centred its platform on anti-racism and decolonization, demanding government apologies and restitution.Footnote 78 Both parties gained seats in the Tweede Kamer, DENK in 2017 and BIJ1 in 2021, using their platforms to amplify demands. Established parties also joined: Groenlinks (Greens) already called for an apology in its 2017 election-manifesto,Footnote 79 and by 2021 most major left-wing parties supported one.

The quick uptake of the apology demand into manifestos shows the system’s openness. From its introduction by two parties in 2017 it became mainstream on the left in the next election five years later. This was followed by an apology one and a half years later after rapid developments in the government coalition, as elaborated under the next variable. In contrast, the UK’s first-past-the-post system limits opportunities for new parties. With two dominant parties, it discourages niche or minoritized interests. Casal Bértoa and Enyedi rank the UK the third most closed system in Europe.Footnote 80 Mair’s indicators highlight its closedness.Footnote 81 Between 1975 and 2003, only one new party entered Parliament, compared to six in the Netherlands.Footnote 82 Internal party innovation is limited: while 45% of MPs occasionally disagree with the party line,Footnote 83 mean deviations per bill are close to zero.Footnote 84 This British discipline may be lower than in the Netherlands, where only 29% vote against the party line, but dissent within dominant parties is a main way new ideas can be advocated. Without it, the party must change course for a new idea to gain credible presence in politics. This closedness is reflected in the treatment of demands for a slavery apology and reparations. Most telling is David Lammy’s case: once a backbench Labour MP who called for reparations, but as Foreign Secretary his earlier stance was dismissed as ‘that was David Lammy long before he became Foreign Secretary. Now he speaks on behalf of the Labour Government’.Footnote 85 This shows a clear divide between the fringes and power centre regarding openness to minoritized voices. As elaborated below, this relates to the wording of Lammy’s reparations demand.

Identifying victims

The identification of victims is a critical factor in shaping the success of reparations movements according to Howard-Hassmann and Lombardo. In the Dutch case, the reparations movement benefited from a well-defined and largely domestic victim group which made the claim. By contrast, the UK’s movement faced challenges due to a more dispersed and diverse claimant base.

The Dutch movement has focused on victims of plantation slavery in Suriname, and on the Dutch Caribbean islands.Footnote 86 Victims of Dutch slavery in Indonesia and South Africa remain ignored.Footnote 87 This emphasis on plantation slavery created a clear, homogenous victim group. Many descendants of these victims are Dutch citizens. About 400,000 individuals with Surinamese roots live in the Netherlands, compared to Suriname’s population of 600,000.Footnote 88 These communities influence political decision-making through parties like DENK and BIJ1. Their presence in Dutch society, through NGOs and interest groups, helps shape national debate and memories of slavery. International victims lack direct representation and, like Suriname, struggle to be identified as stakeholders. Since ‘slavery’ is equated with ‘plantation slavery’, Dutch victims are mainly domestic groups except for those represented by Suriname. The British case shows more diffuse victim identification. While the Caribbean remains the primary reference point,Footnote 89 group representation differs. Unlike Dutch descendants who are domestic citizens with political presence, Britain’s claimant community consists mainly of sovereign states. It includes descendants from former Caribbean colonies like Jamaica, Barbados, and Guyana. Amongst the CARICOM members, twelve of fifteen are former British colonies, advancing the CARICOM 10-Point Plan for Reparatory Justice, targeting all slave-trading powers but especially Britain.Footnote 90 This unified set of regional and international demands complicates UK mobilization: external articulation makes it harder to generate the cohesion Howard-Hassmann considers critical for reparations movements domestically.

If we shift our focus to those victims who are British citizens, we see a divergence with the Dutch case as well. Only 1% of the British population has ‘Black Caribbean’ roots.Footnote 91 In the Netherlands the population with roots on one of the six Dutch Caribbean isles is 1.1 percent, while 2.1 percent have family ties with Suriname.Footnote 92 The large Surinamese population means that there is a significant group in the Netherlands that, despite internal cultural diversity, share a similar history and cultural connection and is internationally mostly represented by just one state (while the Caribbean islands are nations within the Dutch kingdom). The ‘Black Caribbean’ population in the UK is proportionally smaller and significantly more diverse with more than 10 former Caribbean colonies which are now independent.

The British victim identification includes a larger, more diverse group, resulting in more diverse narratives, memories, and demands that are harder to unify. This contrasts with Dutch victims, who are comparatively more homogenous and numerically better represented in domestic society. In line with Howard-Hassmann and Lombardo’s claim that a diverse claimant group hinders a successful reparations movement, we see how the British case is disadvantaged.Footnote 93

Presence of influential domestic allies

An open political system combined with a coherent and politically salient victim group forms the necessary foundation for an apology to enter the national political agenda. Domestic allies are the powerful actors that amplify the call from the community and transform it into action. Starting from organizations close to the victim group to bigger political parties and government entities, the Netherlands saw a clear accumulation of influential actors supporting an apology which kicked off and carried the chain of events that led to the eventual apology. While the UK has seen important institutions offer apologies themselves, there is a lack of uptake by actors in the highest level of government.

Advocacy for a Dutch apology has a long history, but momentum towards the 2022 speech built once influential allies took ownership of the issue. By 2017, two parliamentary parties supported an apology, together holding around 11.5% of seats. While initially fringe, Groenlinks’ endorsement gave the idea legitimacy beyond advocacy organizations. Local governments then proved decisive. In 2018, Rotterdam mayor Ahmed Aboutaleb became the first high-profile official to call for a national apology,Footnote 94 triggering DENK leader Tunahan Kuzu to press the demand in Parliament.Footnote 95 A year later, Minister for Interior Affairs Kajsa Ollongren responded to this by committing the government to a national dialogue on slavery’s legacy.Footnote 96 This was followed by the creation of the Adviescollege Dialooggroep Slavernijverleden (Advisory Board Dialogue-Group Slavery History) in 2020, tasked with examining historical injustices and proposing policy recommendations.Footnote 97 Its report, Chains of the Past, called for an apology and reparations.Footnote 98 The same year, Amsterdam issued its own apology after calls from DENK,Footnote 99 further pressuring the national government. These local and parliamentary allies leveraged institutional influence to push the issue onto the national agenda, showing how domestic allies can drive state apologies even without strong public support.

By 2020, most left-wing parties had adopted the call. In a parliamentary debate convened in response to the Black Lives Matter protests, coalition partners Christenunie and D66 emerged as advocates and added to the pressure that made the PM state that he would be open to re-evaluating the government’s position on apologies if the Chains of the Past recommended such a step.Footnote 100 However, after the publication of the report, the more conservative parties in government and PM Rutte remained apprehensive at the thought of apologies.Footnote 101 However, Rutte’s stance shifted quickly. BIJ1 MP Sylvana Simons punctured his objection that ‘too much time had passed’ by juxtaposing it with his own Holocaust apology and by sharing her family’s direct experiences of slavery and exclusion, thereby transforming abstract debate into personal moral urgency.Footnote 102 The powerful report and stories like those of Simons, amplified by parliamentary allies, domestic and international advocacy groups, made it politically untenable to dismiss the apology as mere symbolism. Another key ally was Franc Weerwind, Minister for Legal Protection and a descendant of enslaved people, who publicly signaled the government’s evolving stance at the 2022 Slavery Remembrance Day.Footnote 103 His role as both a government representative and a member of the affected community reinforced the moral and political urgency of an apology.Footnote 104 This all culminated in the apology in December 2022. Rutte later thanked the many advocates for their ‘unrelenting efforts’ to keep this issue ‘on the agenda’.Footnote 105

In contrast, the British reparations movement lacks strong parliamentary champions. While the All-Party Parliamentary Group for Afrikan Reparations (APPG-AR) advocates for policy change, it comprises only 13 out of 650 MPs, with minimal support from major parties.Footnote 106 Even within the Labour Party, which hosts most APPG-AR members, reparations remain off the agenda, as former leader Tony Blair’s expression of regret is deemed sufficient.Footnote 107 The Starmer government has similarly avoided the issue.Footnote 108 There is a long history of motions and contributions to Parliament calling for action and attention on the issue of reparations. However, these initiatives have always been met with rebuttals from government officials, showing little development in the thinking of the majority of Parliament.

Outside Parliament, the number of influential allies has been increasing over time. The city of Liverpool can be seen as an important example of a lower government offering an apology. However, at the same time this has not resulted in effective requests from Liverpool to the national government like in the case of Rotterdam in the Netherlands. Similarly, the Church of England pledged £100 million toward reparations, with plans to expand it to £1 billion, taking more concrete steps than the government.Footnote 109 However, here too, the Church has not (openly) put pressure on the government to do the same. So, while society sees major developments on the issue of reparations, the explicit connection to the higher levels of government is not actualized.Footnote 110

Ultimately, Dutch domestic allies – advocacy groups from minoritized communities, local governments, and MPs from immigrant backgrounds – translated grass-roots demands into high-level political action. Their presence in Parliament was crucial in overcoming limited public support and securing a formal apology. In the UK, the absence of such institutional ambition and strong parliamentary representation has hindered the movement’s ability to influence government policy. This stark contrast underscores the decisive role of domestic allies in shaping the political viability of reparations.

Framing and forward-looking claims

So far, we have pointed to structural factors and the power of agents to shape policy. The final element of our framework is the framing of the demand for apology, which concerns the discourses employed by the victim group and allied agents to sway people in power. Effective framing emphasizes that slavery is a current problem and frames the demand as a future-oriented solution, using symbols to resonate emotionally and politically.

In the Netherlands, the memory of slavery has not always been given space.Footnote 111 Sustained activism and visibility of the victim group gradually created this space, prompting government recognition of slavery’s enduring effects. For example, Minister Kajsa Ollongren commissioned the Chains of the Past report in 2020, stating: ‘Traces of the slavery past continue to have an impact on society to this day’.Footnote 112 This problem definition was linked to citizenship, equality, and inclusion, central topics in political discourse. Ollongren argued in 2018 that ‘slavery is antithetical to the values of our Constitution […] antithetical to what we aspire to be as a country’,Footnote 113 and the Chains of the Past report connected recognition of historic injustice to combating racism, proposing an apology as a step ‘to achieve recovery, so that a shared future becomes possible’.Footnote 114 In this line we should also understand the explicit and persistent leveraging of the Dutch government’s Holocaust apology in order to strengthen arguments for apology. Indeed, the above-cited discussion between BIJ1 MP Simons and PM Rutte was on this very point.Footnote 115 Namely, how do these two cases relate – is the ‘passage of time’ a qualitative difference foregoing direct comparison?

Societal events highlighted slavery’s modern-day effects, reinforcing the urgency of an apology. Protests against the Black Pete character and the Black Lives Matter movement following George Floyd’s death powerfully illustrated ongoing racism, despite the deeply rooted self-image built around tolerance and equality.Footnote 116 The shift in societal narratives created political opening. A debate was requested and both long-time advocates and new supporters of a slavery apology such as D66 and Christenunie were quick to present an apology as an appropriate reply to these calls for action.Footnote 117

The sudden shift in societal sentiment thus created relevance of the apology as a political issue. On this basis, left-wing parties translated the anti-slavery norm into domestic policy imperatives, showing that a formal apology was foundational for legislative reforms addressing racial inequalities. Confronted with both moral and electoral incentives, the government framed the apology as forward-looking, committing to redress lasting social and economic legacies.

In the UK, the official stance remains a rejection of slavery reparations and apologies. Government discourse treats slavery largely as historical, disconnected from present inequalities. Remembrance events and statements by officials such as Tony Blair exist alongside repeated assertions that slavery is not relevant to current societal problems. Rishi Sunak recently stated that ‘trying to unpick our history is not the right way forward’.Footnote 118 While the Black Lives Matter protests initially seemed to create political momentum – prompting the government to commission a report on racial inequality – the final report largely dismissed systemic racism,Footnote 119 arguing that Britain’s system was no longer ‘deliberately rigged against ethnic minorities’.Footnote 120 Its only explicit reference to slavery framed it not as a historical injustice requiring redress, but as a cultural transformation that shaped Afro-Caribbean identity in Britain.Footnote 121 This framing actively obscured slavery’s enduring structural impacts,Footnote 122 precluding the very premise that the history of slavery is worth processing at all.

While both the Netherlands and the UK have a history of remembering slavery as something distant in both time and space,Footnote 123 and racism as alien to their societies,Footnote 124 the UK has a unique and powerful memory as the first nation to abolish slavery.Footnote 125 This is a particularly difficult obstacle in efforts to fit any request for apology or other reparations to British sensitivities. In the Dutch case one of the major challenges was to break the ‘deafening silence’ that surrounded the Dutch history of slavery,Footnote 126 to generate knowledge of its very existence. The nuance in the UK is that slavery has been visible but that the painful memory of the victim groups has to challenge an existing positive self-image.

Lastly, the framing of the claim is not conducive to persuade politicians to a state apology. The UK debate is centred around the broad concept of ‘reparations’, often explicitly explained as monetary payments. Internationally, bodies such as CARICOM in conjunction with government officials continuously press the government on the issue of monetary reparations.Footnote 127 While international actors in the Dutch debate similarly frame the claim in financial terms,Footnote 128 the big difference between the cases lies in the framing of the demand in the domestic debate. This is illustrated by broadly publicized comments made by future foreign secretary, then Labour backbencher, David Lammy in 2018: ‘I’m afraid as Caribbean people we are not going to forget our history – we don’t just want to hear an apology, we want reparation’.Footnote 129 This emphasis on monetary compensation is reinforced by high-profile commitments such as the Church of England’s proposed £1 billion fund and by widely publicized estimates of aggregate reparations put forward by judges and scholars.Footnote 130 Several advocates – including MP Bell Ribeiro-Addy – have warned that the circulation of large, headline figures tends to generate public alarm rather than deliberative support, producing a political backlash that narrows rather than broadens the space for reform.Footnote 131 This explains why financial framings struggle to gain traction in Westminster: without localization linking compensation to concrete, constituency-sensitive policies, monetary claims risk alienating allies and stalling recognition. This is not to say monetary claims are unjustified or advocates should forego reparations beyond an apology. Rather, this suggests the UK debates’ focus on financial compensation, rather than localized approaches resonating with domestic actors, has limited the claim’s political momentum toward an official apology.

Discussion

Our analysis confirms that robust domestic coalitions, receptive political opportunity structures, and resonant framing are essential for state apologies. In the Netherlands, the apology emerged through advocacy by high-profile actors such as the Mayor of Rotterdam and national political parties. Momentum was amplified by the broader context of Black Lives Matter protests and by framing the apology as a future-oriented solution to persistent inequalities. This framing offered political parties a practical ‘formula’ to translate moral acknowledgement into concrete policy measures. Left-wing parties swiftly incorporated the call for apology into their manifestos, pressuring the government, which, after initial hesitation, was persuaded by the framing.

The UK illustrates the consequences of limited opportunity structures and less effective framing. High-profile advocates exist but their influence has not translated into government action. The evolution of Foreign Secretary David Lammy’s public stance demonstrates how the British system handles reparations claims: while there is some openness to advocacy on the fringes, these voices rarely penetrate the centre of power, and initiatives appear ignored or suppressed at higher levels. The significance of condensation symbols underscores the importance of political openness. In the Netherlands, controversies over Black Pete and the BLM movement shaped parliamentary debate on slavery reparations, sustaining public and institutional pressure. In the UK, despite widespread BLM protests, political responses remained dismissive. Even during peak BLM mobilization, the UK’s opportunity structure remained largely closed, constraining institutional impact.Footnote 132

Framing in the UK further constrains prospects for an apology. The government does not fully recognize slavery’s contemporary effects, diminishing the perceived urgency. This is compounded by the British abolition memory, which resists integrating narratives of historical injustice. Moreover, the claimant discourse is dominated by international actors, drowning out domestically mobilized voices. This has produced a fragmented narrative often centred on monetary claims. While these claims are not inherently unjustified, their prominence highlights the misalignment between advocacy and domestic political receptivity. By contrast, the Dutch apology was paired with a €200 million fund framed as a forward-looking measure addressing inequality and inclusion. Because policies must align with both local sensitivities and decision-makers’ cost-benefit considerations, demands that are perceived as a strain on state finances without directly serving politicians’ constituents are unlikely to gain traction.

Evaluated against our theoretical framework, two decisive variables explain why the Netherlands, unlike the UK, pioneered a state apology: an open multi-party system receptive to minoritized-led advocacy, and cohesive domestic allies capable of localizing and framing the norm. These conditions are underpinned by a mobilized, politically relevant victim group. International pressure does not automatically accelerate the realization of state apologies. In the UK, the internationalized claimant group complicates consensus-building and drowns out domestic voices, even though these are best positioned to shape their own government’s response. Extensive international attention can therefore complicate, rather than facilitate, an apology. This aligns with postcolonial scholarship emphasizing the limited leverage of global majority nations over Western states on historical justice issues.Footnote 133 International allies can enhance legitimacy but cannot substitute for strong domestic political advocacy.

Our findings underscore the limits of bottom-up mobilization and the need for a framework where political openness, strategic allies, cohesive victim groups, and resonant framing converge. Howard-Hassmann and Lombardo’s emphasis on identifiable victim groups and resonant claims is confirmed, but institutional receptiveness is crucial.Footnote 134 In the UK, despite allies and public support, claimants could not overcome a closed political system, showing that open opportunity structures are essential for state action. Strategic domestic allies are decisive. Dutch elites reframed the slavery apology demand into a nationally resonant inclusion project, aligned with Acharya’s localization framework. Regilme’s interest convergence theory explains their motivation: linking reparations to mainstream politics enhanced legitimacy.Footnote 135 In the UK, elite incentives pointed oppositely, neutralizing claims. A cohesive, politically relevant victim group is indispensable. Dutch descendants organized through BIJ1 and DENK maintained pressure; UK claimants, dispersed internationally, lacked similar influence. Finally, framing links moral claims to feasibility: Dutch advocates presented the apology as forward-looking, whereas UK discourse remains constrained by abolitionist pride and financial concerns. The findings suggest that Howard-Hassmann and Lombardo’s focus on framing must be supplemented with the insights from Tarrow, Acharya, and Regilme.Footnote 136 Sovereign apologies require more than compelling frames: they depend on open institutions, elite allies who localize norms, and convergence between moral demands and political interests.

While this study highlights the decisive role of political openness and a mobilized, coherent claimant group, these conditions should not be read as deterministic. They enable apologies but do not guarantee them, as outcomes also depend on contingent political dynamics. Moreover, ‘unity’ within victim groups is always partial: claimants are diverse communities, and coherence is often strategically constructed rather than naturally given. Finally, while international actors rarely substitute for domestic mobilization, they can still amplify local voices and shape the broader legitimacy of reparations claims, as is stressed in literature on transnational advocacy networks.Footnote 137 A potential critique is that the Dutch case may be an outlier rather than a model. While this is a valid concern, the findings suggest the Netherlands’ experience provides transferable lessons – particularly regarding political openness, framing, and coalition-building. These conditions are not unique to the Netherlands and could be leveraged in other national contexts. What is key at all times, however, is that adaptations are necessary to account for domestic political environments, normative contexts, and national identity frameworks.

This comparative analysis shows that state apology viability depends less on international advocacy alone than on how global demands embed within domestic political contexts. In the Netherlands, an open multi-party system allowed minoritized-led parties to enter politics, while allies reframed reparations claims to resonate with national identity and democratic values. In contrast, the UK’s closed party system, fragmented claimant community, and lack of elite interest convergence prevented momentum, despite higher public support and international advocacy. These findings suggest reparations movements succeed not merely through compelling frames or grass-roots mobilization, as Howard-Hassmann and Lombardo stress, but through three factors: open opportunity structures,Footnote 138 strategic localization of global norms,Footnote 139 and interest convergence between moral claims and elite interests.Footnote 140 The Dutch case demonstrates a possible replicable model for translating global moral demands into domestic policy agendas. Although our analysis centres on transatlantic slavery, a similar combination of open political systems, unified domestic coalitions, and strategic framing could produce sovereign apologies for other colonial injustices. Future research should examine how these dynamics combine in other contexts of historical injustice, and under what conditions symbolic recognition translates into durable postcolonial justice.

Conclusion

This article explained why the Netherlands remains the only European state to date to issue an official apology for slavery. Through process-tracing analysis, the analysis identified three decisive factors: the openness of the Dutch political system, parliamentary representatives advocating for reparations, and a unified domestic victim group. In contrast, the UK’s winner-take-all system blunted diverse pro-reparations voices, while dispersed international claimants complicated demands. The study found that external pressure was largely ineffective alone, reaffirming that international pressures must work with favourable domestic political structures and elite allies in shaping state responses to historical injustices. The comparative evidence confirms that political opportunity structures and domestic allies impact how international pressure or public mobilization produce formal state apologies. While social movements raise awareness, their success depends on embedding demands within institutional channels of power. The Netherlands’ apology was possible due to political receptiveness within its state and non-state institutions and key politicians, whereas the UK’s closed system stifled momentum despite considerable public mobilization. This supports Tarrow’s social movement theory while challenging approaches that overstate framing and global advocacy.Footnote 141

Despite the significance of domestic factors as demonstrated by the case of the Netherlands, global and national dynamics do not operate in a strict binary. Indeed, what matters is the specific alignment of these forces. Understanding it through the AAM, the Dutch case shows how strategic localization and elite interest-alignment, when channeled through open institutions, convert global justice claims into sovereign apology – a sequence future studies should test across different institutional types. Looking ahead, future research should test the framework developed here in other European states and further examine how shifting global power dynamics affect reparations politics. The weakening Euro-American alliance and the global majority’s growing influence present new structural opportunities for reparations movements. As former colonial powers lose dominance, emerging global majority coalitions could exert greater diplomatic and economic pressure while providing support for local actors in European states. Rather than relying on voluntary state action, reparations advocates must leverage these geopolitical shifts, forge stronger transnational alliances, and use alternative diplomatic and legal platforms to push for historical justice. In a changing world order, the global reparations movement has a rare opportunity to redefine the terms of accountability. In a world shaped by deep socio-economic inequalities, a formal state apology is not the end of historical justice but the first crucial step – an acknowledgement of both historic culpability and ongoing participation in historically induced stratifications, which must be followed by concrete efforts to dismantle slavery’s enduring legacies.

Video Abstract

To view the online video abstract, please visit: https://doi.org/10.1017/S0260210525101629.

Acknowledgements

We thank the editors of Review of International Studies and the anonymous reviewers for their careful, rigorous, and generous critiques, which materially improved the clarity, argument, and evidentiary basis of this manuscript. We also appreciate the editorial team’s guidance during revision and the reviewers’ incisive suggestions, which strengthened the theoretical framework and the process-tracing analysis.

Appendix A