1 Introduction

The field of ultra-high-power lasers is further developing at a fast pace and is specializing in different areas of investigation and applications. High-intensity, high-field studies are taking advantage of the ever-increasing high peak power, while applications in particle accelerators for secondary sources and biomedical applications are thriving thanks to the emergence of reliable systems with high average power.

The review paper ‘Petawatt class lasers worldwide’ published in 2015[ Reference Danson, Hillier, Hopps and Neely1] provided a comprehensive overview of the global state of ultra-high-power lasers at that time. In 2018, the Nobel Prize in Physics was awarded[ 2] for work in this area, which was predicated following the publication of the transformative paper in 1985 by Strickland and Mourou[ Reference Strickland and Mourou3].

In the later review paper ‘Petawatt and exawatt class lasers worldwide’ published in 2019[ Reference Danson, Haefner, Bromage, Butcher, Chanteloup, Chowdhury, Galvanauskas, Gizzi, Hein, Hillier, Hopps, Kato, Khazanov, Kodama, Korn, Li, Li, Limpert, Ma, Nam, Neely, Papadopoulos, Penman, Qian, Rocca, Shaykin, Siders, Spindloe, Szatmári, Raoul, Zhu, Zhu and Zuegel4], the original authors were joined by world experts from all corners of the globe. The resulting paper has become one of the standard references in the field. The paper was broken up into three sections:

-

• geographical overview of facilities;

-

• discussion of 50 years of ultra-high-power lasers;

-

• future technologies.

There have also been two excellent publications presenting overviews of the technology associated with petawatt lasers: Waxer et al. [ Reference Waxer, Kruschwitz and Bromage5] provide an introduction to the laser science and technology underpinning these systems, and Li et al. [ Reference Li, Leng and Li6] give a technology review providing a possible roadmap for the next-stage development of short-pulse petawatt lasers. In this editorial we want to highlight some of the new key developments in the community, facility capabilities and prospects since the paper was published.

2 Regional updates

2.1 United States

2.1.1 LaserNet US

LaserNet US[ 7] has grown since its early days and now encompasses all 11 of the high-power lasers in the United States and Canada. In the previous review we highlighted the nine facilities that made up LaserNet US at the time. Most of these have continued operations and have had productive user access programmes. The Advanced Laser Light Source (ALLS) at the University of Quebec, Canada, was reported separately in the previous review but is now within the LaserNet US family.

There are two facilities that have unfortunately ceased operations: the Texas Petawatt Laser Facility stopped operations and shut down in May 2025 due to funding cutback, and the Diocles laser at the Extreme Light Laboratory, University Nebraska-Lincoln has also ceased operations.

There are three new non-petawatt facilities within the LaserNet US family: iFAST, University of Central Florida; Laboratory for Laser Matter Interactions at the University of Maryland; and Phoenix Laboratory at UCLA.

2.1.2 University of Michigan

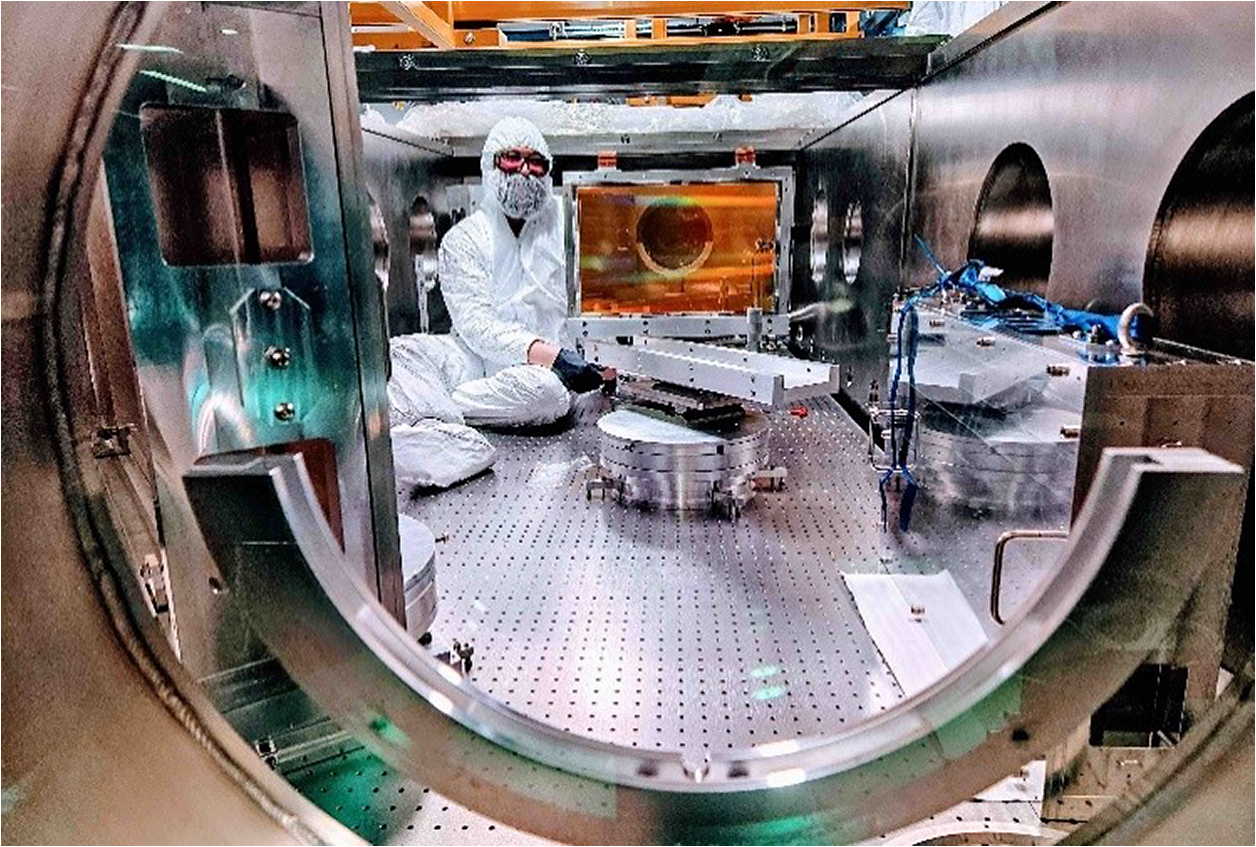

The University of Michigan is now home to the NSF (National Science Foundation) ZEUS (Zettawatt Equivalent Ultrashort pulse laser System) user facility in the Gérard Mourou Center for Ultrafast Optical Science (CUOS)[ 8], which has replaced the Hercules laser. At 3 PW it is the highest power laser in the United States. The laser facility is based on Ti:sapphire technology operating at 800 nm. Its output can be delivered to two compressors: one producing 3 PW (75 J in 25 fs) compressed pulses, shown in Figure 1; and the second 500 TW (12.5 J in 25 fs) compressed pulses[ Reference Maksimchuk, Nees, Hou, Anthony, Bae, Bayer, Burger, Campbell, Cardarelli, Contreras, Ernst, Falcoz, Fitzgarrald, Jovanovic, Kalinchenko, Kuranz, Latham, Ma, McKelvey, Nutting, Qian, Russell, Sucha, Thomas, Van Camp, Viges, Willingale, Young, Zhang and Krushelnick9]. These outputs can be directed to three target halls. An upgrade is planned to accommodate the 3 PW beam in 2026.

Figure 1 Engineer Richard Anthony aligning the diffraction gratings in the ZEUS 3 petawatt compressor chamber (Copyright: Anatoly Maksimchuk, University of Michigan).

2.1.3 Colorado State University

Colorado State University (CSU) in partnership with Marvel Fusion (see Section 4) is building a new ultra-high-power laser facility, called ATLAS, that will be part of CSU’s Advanced Lasers for Extreme Photonics Center (L-ALEPH)[ 10]. ATLAS will house three high-repetition-rate PW lasers. CSU’s ALEPH Ti:sapphire laser will be upgraded to 2 PW using diode-pumped frequency doubled pump lasers. As the current laser it will operate both at 800 nm and at 400 nm wavelengths with ultra-high contrast. Marvel Fusion will provide two additional 100-J-class, 100-fs PW laser systems with up to 10 Hz pulse repetition rate. The systems are based on OPCPA (optical parametric chirped pulse amplification) for bandwidth and contrast control, use face-cooled diode-pumped Nd:glass amplifiers as power stages and implement second-harmonic generation for further contrast improvements. Pulses from up to three ATLAS laser systems will be synchronized at the target chambers for experimental flexibility. The facility will be completed in 2027 and will be accessible to users through LaserNet US[ 11].

2.2 Asia

2.2.1 China

The recent ultra-high-power facility development in China has been extraordinary and is highlighted in the review paper by Li et al., 2025[ Reference Li, Chen, Chen, Liu, Gu, Guo, Hua, Huang, Leng, Li, Li, Li, Lin, Lu, Lyu, Ma, Ning, Peng, Wan, Wang, Wang, Wei, Yan, Zhang, Zhao, Zhao, Zhou, Zhou, Zhou, Zhu and Zhu12]. A summary of the developments in PW-class lasers since the 2019 review, which have either been commissioned or under construction, is given below.

2.2.2 Shanghai

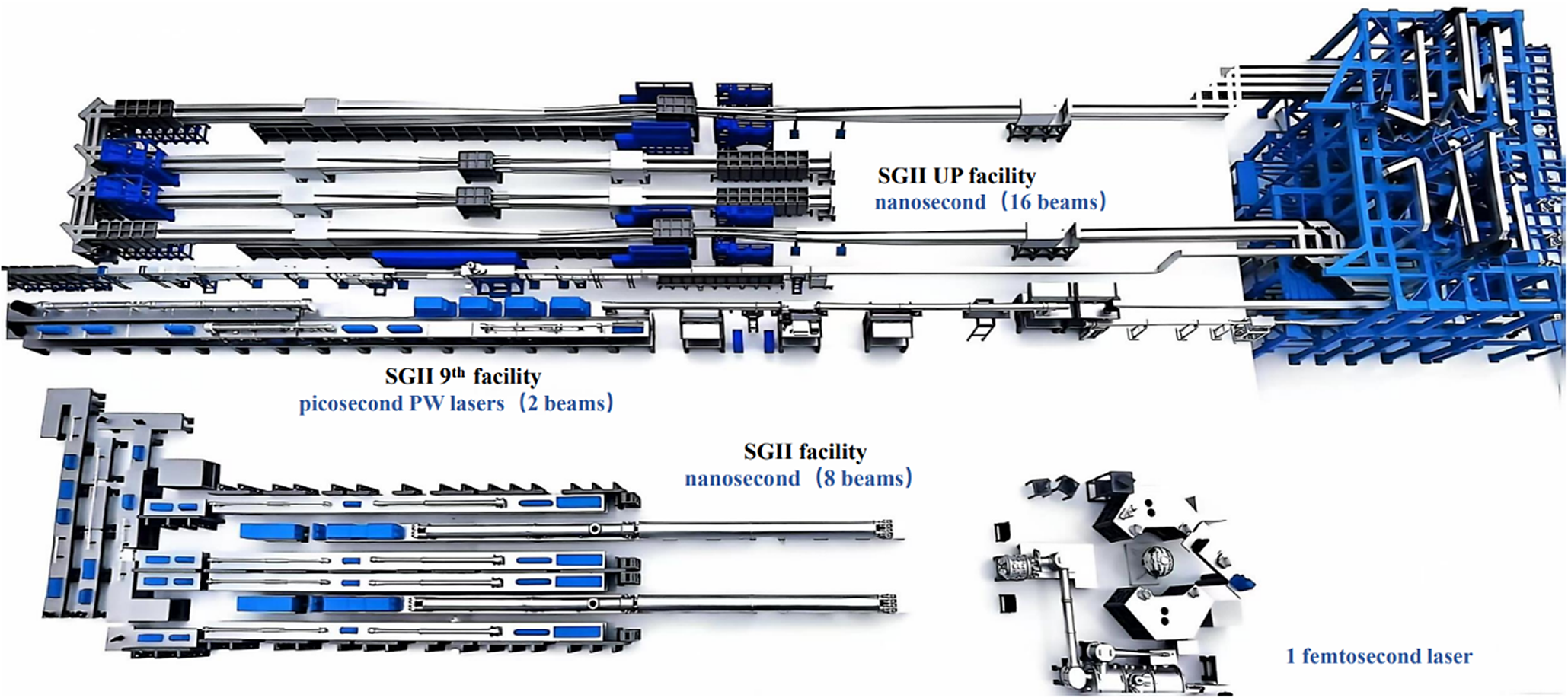

SIOM (Shanghai Institute of Optics and Fine Mechanics) – the SG-II UP facility’s output has been upgraded twice since the publication of the review paper, including the provision of 16 ns beams and two PW/ps laser beamlines[ 13]. The current capabilities of the facility are therefore as follows:

-

• SG-II UP facility (nanosecond) – 16 beamlines with total maximum energy of 50 kJ/5 ns/3ω;

-

• SG-II picosecond PW beams – two PW beams: 700 J/10 ps/1ω and 800 J/10 ps/1ω;

-

• SG-II facility (nanosecond) – eight beamlines with total maximum energy of 3 kJ/3 ns/3ω, 6 kJ/3 ns/1ω;

-

• SG-II 5 PW system (femtosecond) – 150 J/30 fs/808 nm (currently operating at >1 PW).

An overview of the SG-II facility is shown in Figure 2.

Figure 2 Overview layout of the SG-II multifunctional high-power laser experiment platform (image courtesy of SIOM).

ShanghaiTech University/SIOM, State Key Laboratory of High-Field Laser Physics (LHFLP): SULF facility – the 1 PW beamline is operational and the 10 PW beamline continues to be commissioned, with a demonstration of performance at 12.8 PW.

SJTU (Shanghai Jiao Tong University) Key Laboratory for Laser Plasmas (LLP) – LLP has upgraded its original 200 TW laser system to a dual-beam laser platform, at powers of 200 and 300 TW, respectively, with high spatiotemporal synchronization (~7 fs·10 μm) and focused power of more than 1021 W/cm2. The new laser facility is named ‘Chongming’, after a mythical bird in ancient Chinese legend with two pupils in each eye – an emblem that symbolizes the 200 TW laser system. The primary objectives of the Chongming facility are the research on quantum electrodynamics (QED) plasma physics, staged laser wake-field acceleration and intense laser-based axion dark matter research.

SJTU Tsung-Dao Lee Institute (TDLI)/State Key Laboratory of Dark Matter Physics – Laboratory Astrophysics Platform (LAP): the 3 PW beam line has been constructed, with an intensity (at focus) reaching 1023 W/cm2, plus two nanosecond beam lines with a total energy of over 700 J and a high-quality electron beam line with a maximum energy of 90 MeV. Currently, the construction of these four beam lines is nearing completion and is to be commissioned by the end of 2025 for cutting edge research on laboratory astrophysics. Figure 3 shows an image of the target area of the LAP at TDLI.

Figure 3 Image of the target area of the LAP at TDLI (image courtesy of TDLI).

2.2.3 Beijing

Institute of Physics (IOP), Chinese Academy of Sciences (CAS) – in addition to the existing XL-III facility the IOP has been developing the Synergetic Extreme Condition User Facility (SECUF) in the Huairou District of Beijing, a 1 PW laser facility.

Peking University – the 2 PW CLAPA-II (Compact LAser-Plasma Accelerator) laser for proton acceleration that was proposed in the original review is now constructed and is being commissioned.

Tsinghua University – in collaboration with the Beijing Academy of Quantum Information Sciences (BAQIS) and IOP – has developed compact PW-class lasers: the first is a 1 PW laser used in conjunction with an electron/positron linac; the second is a 300 TW laser to drive an inverse Compton scattering source for nuclear photonics research.

2.2.4 Others

Shenzhen Technology University (SZTU) – currently a 200 TW laser is under construction to be coupled with a linear electron accelerator for high-energy-density physics (HEDP) studies.

National University of Defence Technology (NUDT) – with the recently established, 2023, Hunan Key Laboratory of Extreme Matter and Applications, they are commissioning a 200 TW laser for HEDP studies.

2.2.5 India

In India there are two PW lasers: a Thales system at the Raja Ramanna Center for Laser Technology, Indore (1 PW, 0.1 Hz, 30 fs), installed a few years ago, and a second system about to be installed by Amplitude at the ‘TRISHUL’ Petawatt Laser Science Facility at the Hyderabad campus of the Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR) (1 PW, 25 fs, 1 Hz).

2.3 Europe

Laserlab-Europe has grown to encompass 48 partners and transformed to become an AISBL (Association Internationale Sans But Lucratif), an international non-profit organization under Belgian law[ 14]. The association’s fundamental aims remain unchanged, that is, facilitating the development of advanced lasers and laser-based technologies in Europe. It achieves this through offering facility access through Lasers4EU, networking activities and technology development projects.

The ELI-ERIC (Extreme Light Infrastructure – European Research Infrastructure Consortium)[ 15] was established in 2021 and brings together the ELI facilities in the Czech Republic (ELI Beamlines), the Attosecond Light Pulse Source (ELI ALPS) and the facility in Romania (ELI Nuclear Physics). The facilities have now all come online and opened to users. The 10 PW beamline at Extreme Light Infrastructure – Nuclear Physics (ELI-NP) has been online since 2020[ Reference Lureau, Matras, Chalus, Derycke, Morbieu, Radier, Casagrande, Laux, Ricaud, Rey, Pellegrina, Richard, Boudjemaa, Simon-Boisson, Baleanu, Banici, Gradinariu, Caldararu, De Boisdeffre, Ghenuche, Naziru, Kolliopoulos, Neagu, Dabu, Dancus and Ursescu16]. Figure 4 shows a photo of the ELI-NP control room firing the first 10 PW laser shot broadcast live online on 19 August 2020. The beamline has recently been upgraded to improve its temporal contrast. A remarkable statistic is that on 1 November 2024, the facility delivered 274 shots at 10 PW output[ 17]. At ELI Beamlines the L3-HAPLS beamline is operating at 0.7 PW (20 J, <29 fs, 0.2 Hz) with a plan to reach 1 PW, 10 Hz in 2028. The L4f-ATON laser is being commissioned; at present it is generating 5.1 PW (786 J in 154 fs) with a plan to reach 10 PW (1.5 kJ, 150 fs, 1 shot/min) in 2026[ 18].

Figure 4 Image of the ELI-NP control room firing the first 10 PW laser shot broadcast live online on 19 August 2020 (picture courtesy of ELI-NP).

Within the UK the Central Laser Facility is undergoing a major upgrade. EPAC (Extreme Photonics Applications Centre), a 10 Hz dual-beamline petawatt facility, is being commissioned and is due to come online in 2026. The Vulcan laser closed in 2023, and the facility is being rebuilt to hold Vulcan 20-20, which will be a 20 PW beamline (400 J, 20 fs) supported by a range of other short- and long-pulse beamlines[ Reference Hernandez-Gomez, Collier, Armstrong, Aleksandrov, Booth, Butcher, Carrol, Clarke, Crespo, Pinto, De-vido, Glize, Green, Heathcote, Oliveira, Oliver, Mason, Pattathil, Quinn, Spindloe, Stuart, Symes and Winstone19].

In France the Apollon facility is open with 3 PW (70 J, 22 fs) and 1 PW beamlines available for users[ Reference Yao, Lelièvre, Cohen, Waltenspiel, Allaoua, Antici, Ayoul, Beck, Beluze, Blancard, Cavanna, Chabanis, Chen, Cohen, Cossé, Ducasse, Dumergue, Hai, Evrard, Filippov, Freneaux, Gautier, Gobert, Goupille, Grech, Gremillet, Heller, d'Humières, Lahmar, Lancia, Lebas, Lecherbourg, Marchand, Mataja, Meyniel, Michaeli, Papadopoulos, Perez, Pikuz, Pomerantz, Renaudin, Romagnani, Trompier, Veuillot, Vinchon, Mathieu and Fuchs20]. The main beamline is planned to be upgraded to 6–7 PW in 2026. A full specification can be found on the Apollon website[ 21]. At LOA (France), LAPLACE-HC[ 22] is under development with a Ti:sapphire amplifier targeting 100 Hz, approximately 200 mJ, less than 25 fs, with plans to scale to approximately 1 J at 100–200 Hz. The ‘HE’ arm (high energy) aims at GeV-scale electron acceleration using a 350 TW Ti:sapphire system. The LAPLACE infrastructure is being built in synergy with the HERACLES3[ 23] joint laboratory (CNRS/IP Paris/Thales) to develop new laser and optical technologies tailored for intense, repeatable operation.

In Italy, CNR-INO/ILIL Pisa is building an additional beamline featuring a 100 Hz, 1 J, approximately 25 fs laser and a new underground target area as part of the IPHOQS and EUAPS/EuPRAXIA[ 24] effort and dedicated to biomedical applications. I-LUCE (INFN Laser indUCEd radiation production) is a new high-power laser facility under construction at INFN–LNS in Catania, Italy, part of the EuAPS/EuPRAXIA programme. It will feature two arms: a 50 TW, 10 Hz beamline for moderate-intensity studies and a 500 TW, 1 Hz beamline for high-energy laser–plasma acceleration, particle sources and nuclear applications.

In Germany, DESY’s KALDERA[ 25] project aims to produce 100 TW peak power pulses (≈3 J, 30 fs) at up to 1 kHz, that is, in the kW average power class, using Ti:sapphire chirped pulse amplification (CPA) architecture. In its first milestone, KALDERA has already driven its MAGMA plasma accelerator at 100 electron bunches per second (100 Hz), demonstrating the potential for active stabilization of beam properties via feedback loops.

In Russia the PEARL laser has integrated the CafCA (compression after compressor approach) to reduce its pulse duration from 45 to 11–10 fs using a 5 mm thick silica plate or 4 mm thick potassium dihydrogen phosphate (KDP) crystal to increase the bandwidth, which is then compressed using chirped mirrors[ Reference Ginzburg, Yakovlev, Kochetkov, Kuzmin, Mironov, Shaikin, Shaykin and Khazanov26]. The FEMTA laser at Sarov has been decommissioned but work continues on the XCELS project (see Section 3.1).

In Sweden the Light Wave Synthesizer at the University of Umeå is now operational, generating 100 TW in a 4.3 fs pulse[ Reference Veisz, Fischer, Vardast, Schnur, Muschet, De Andres, Kaniyeri, Li, Salh, Ferencz, Nagy and Kahaly27]. These pulses are directly amplified and compressed (in bulk media rather than a grating-based compressor), generating the highest peak powers available in a few-cycle laser.

3 Advances in future technologies

3.1 Multi-petawatt/exawatt systems

XCELS (eXawatt Center for Extreme Light Studies): the enhanced design performance of the XCELS facility at the Institute of Applied Physics of the Russian Academy of Sciences in Nizhny Novgorod, Russia, is detailed in a review paper[ Reference Khazanov, Shaykin, Kostyukov, Ginzburg, Mukhin, Yakovlev, Soloviev, Kuznetsov, Mironov, Korzhimanov, Bulanov, Shaikin, Kochetkov, Kuzmin, Martyanov, Lozhkarev, Starodubtsev, Litvak and Sergeev28], with a summary of other proposed multi-PW facilities. The XCELS laser will have 12 identical channels, each generating a pulse with power of 50 PW and maximum focal intensity of 0.44 × 1025 W/cm2. All 12 beams are directed to the main target chamber, in which they are focused in a dipole geometry with the focal intensity of almost 1026 W/cm2.

OPAL[ Reference Bromage, Bahk, Begishev, Dorrer, Guardalben, Hoffman, Oliver, Roides, Schiesser, Shoup, Spilatro, Webb, Weiner and Zuegel29]: a significant development is LLE University of Rochester, United States, now working on developing 25 PW (NSF midscale) and eventually 75 PW EP-OPAL (optical parametric amplifier line)[ 30]. Some funding has already been made available for preliminary design. They have already demonstrated a joule-class OPCPA based on the old glass 700 fs multi-terawatt (MTW) system to make MTW OPAL[ Reference Begishev, Bagnoud, Bahk, Bittle, Brent, Cuffney, Dorrer, Froula, Haberberger, Mileham, Nilson, Okishev, Shaw, Shoup, Stillman, Stoeckl, Turnbull, Wager, Zuegel and Bromage31], at about 15 fs, with a centre wavelength of around 900 nm.

SEL: the SEL (Station of Extreme Light), SIOM/ ShanghaiTech University, Shanghai, China, 100 PW facility will be commissioned at the 50 PW level by the end of 2027[ 32].

3.2 Towards an ultra-high repetition rate

Recent achievements in high average power, ultrashort lasers are emerging from the development of two promising platforms based on thulium doped gain media, aiming at kHz-rate, 2-μm, high-efficiency systems.

In the United States, at the Lawrence Livermore’s BAT (Big Aperture Thulium) programme using thulium-doped yttrium lithium fluoride (Tm:YLF), Tamer et al. [ Reference Tamer, Reagan, Galvin, Batysta, Sistrunk, Willard, Church, Neurath, Galbraith, Huete and Spinka33] have demonstrated diode-pumped Tm:YLF amplification reaching 1 GW peak power and more than 100 J pulse energy in a multi-pulse extraction regime, as well as a compact Tm:YLF CPA yielding joule-class, compressible pulses[ Reference Tamer, Hubka, Kiani, Owens, Church, Batysta, Galvin, Willard, Yandow, Galbraith, Alessi, Harthcock, Hickman, Jackson, Nissen, Tardiff, Nguyen, Sistrunk, Spinka and Reagan34]. The BAT architecture emphasizes high average power via continuous pumping and multi-pulse extraction to maintain high efficiency in the 2-μm band, with direct relevance also to next-generation lithography where high-repetition-rate, high-average-power drivers are required.

In Italy, the CNR-INO/ILIL initiative is based on Tm:Lu2O3 ceramics and is developing an edge-pumped, fibre-coupled amplifier chain using Tm:Lu2O3 ceramics. A key enabling study by Palla et al. [ Reference Palla, Labate, Baffigi, Cellamare and Gizzi35] provides a detailed thermal and pump absorption model to guide disk geometry, cooling and diode layout. More recently, Fregosi et al. [ Reference Fregosi, Brandi, Labate, Baffigi, Cellamare, Ezzat, Palla, Toci, Whitehead and Gizzi36] report measured slope efficiencies of approximately 73% and extract a cross-relaxation coefficient of approximately 1.9 in 4% (atomic fraction) Tm:Lu2O3 ceramics.

4 Fusion ignition – benefits to high-power laser development

The demonstration of an igniting plasma on NIF, LLNL in August 2021 produced the world’s first burning plasma. This was followed in December 2022 by a demonstration of gain, getting more fusion energy out than laser energy delivered. This was a major milestone and the culmination of decades of effort. This was not only a major milestone for the scientific community but kickstarted the pursuit of fusion energy as an alternative future green energy contender.

4.1 Companies

Many fusion energy companies have appeared globally, largely funded through private investment. Included in these are several companies utilizing high-power laser technology attracting significant private finance.

-

• Anubal Fusion (India)

Anubal Fusion was formed in 2024 using the inertial confinement fusion (ICF) approach, using high-energy lasers to heat up proton-boron fuel pellets. They use scientific expertise from TIFR Hyderabad and IIT Madras.

-

• Blue Laser Fusion (United States/Japan)

Blue Laser Fusion was formed in 2022. Their approach uses a MJ-class output from an optical enhancement cavity laser with a fast repetition rate hydrogen-boron fuel, ‘HB11’[ 37].

-

• EX-Fusion (Japan/Australia)

EX-Fusion uses the fast ignition approach developed at the University of Osaka, Japan, together with a fuel target accelerated to a velocity of 100 m/s injected towards the centre of the reactor[ 38].

-

• Focused Energy (Germany/United States)

The Focused Energy ignition system plans to demonstrate the feasibility of proton fast ignition to pave the way in a subsequent facility to reliably provide fusion energy. They are building a purpose built facility in the California Bay area, United States[ 39].

-

• GenF Fusion Generated Energy (France)

GenF aims at using ICF using deuterium–tritium (D-T) compressed targets. Launched as a spin-off from Thales, GenF has already gathered extensive nuclear expertise through its collaboration with the Thales, CNRS’LULI and CELIA laboratories, and the CEA[ 40, Reference Ribeyre, Chesneau, Besaucèle, Néauport and Casner41].

-

• HB11 Energy (Australia)

HB11 Energy uses laser-driven proton fast ignition to ignite hydrogen-boron fuel. They are constructing a new laser in Adelaide, Australia[ 42].

-

• Inertia (United States)

Inertia builds on the work at the LLNL on NIF. They were founded in 2025 with architecture that is a 10 megajoule (MJ) diode-pumped, solid-state laser driving an indirect drive target with D-T fuel[ 43].

-

• LaserFusionX (United States)

Founded in 2022, LaserFusionX’s approach is based on advances in argon-fluoride (ArF) laser technology and high-gain target designs conducted at the US Naval Research Laboratory (NRL), United States.

-

• Longview Fusion Energy Systems (United States)

Longview builds on the success of the experiments on NIF by combining laser-driven fusion physics with commercial laser systems, fusion fuel, fusion engine technologies, conventional construction materials and techniques and a modular, grid-ready power plant design[ 44].

-

• Marvel Fusion (Germany/United States)

Marvel Fusion was founded in Munich, Germany, in 2019, and has established a subsidiary in Fort Collins, Colorado, working with CSU to use nano-rod technology to couple the laser energy to drive fusion reactions. They are working with CSU to build the ATLAS facility, housing three synchronized high-repetition-rate PW lasers[ 45]. The design concept of CSU’s ATLAS facility building is shown in Figure 5, with an inset showing the construction activities in 2025.

-

• Xcimer Energy Corporation (United States)

Xcimer Energy uses 10 MJ krypton fluoride excimer laser technology to use the proven inertial approach using D-T fuel and molten salt coolant to fully protect the chamber structural wall from fusion output[ 46].

Figure 5 Design concept of Colorado State University’s Advanced Lasers for Extreme Photonics Center, the ATLAS facility (picture courtesy of Colorado State University).

A summary of all 42 fusion companies affiliated to the FIA (Fusion Industry Association) can be found in their 2025 report ‘The global fusion industry in 2025’[ 47].

4.2 Government and international initiatives

In addition to the above there have been several government and international initiatives.

-

United States

Building on the NIF scientific achievements, the Department of Energy (DOE) has launched targeted inertial fusion energy (IFE)-related programmes, including a US$42 million, 4-year ‘Inertial Fusion Energy Science and Technology Accelerated Research’ effort, as well as a broader US$107 million ‘Fusion Innovative Research Engine (FIRE) Collaboratives’ initiative that connects LLNL’s IFE Institutional Initiative with private and academic partners. In addition, Congress has supported the ICF mission through a substantial appropriation of US$690 million (a US$60 million increase over 2023) for ICF research via the National Nuclear Security Administration. Meanwhile, the DOE’s Milestone-Based Fusion Development Program is guiding commercialization by awarding US$46 million to eight private fusion companies – including some pursuing inertial confinement approaches – for pilot plant design and research. In 2025 the DOE Office of Science published the ‘Fusion Science & Technology Roadmap’[ 48]. The Roadmap targets actions and milestones up to the mid-2030s, providing the scientific and technological foundation to support a competitive US fusion energy industry.

-

China

At SIOM North Campus a new laser facility for double-cone direct drive ICF studies is under construction. Provisionally called the Shenguang X Laser Facility (SG-X), this new laser facility is going to have several tens of kJ-class ns long-pulse laser beams for compression coupled with multiple kJ-class ps short-pulse beams. It is expected to be completed in 2027. Indirect drive ICF continues to be carried out in the CAEP facilities in Mianyang with a new facility coming online in 2027[ 49].

-

Germany

In December 2024, the German Federal Ministry of Education and Research (BMBF) launched the ‘Fusion 2040’ programme – an initiative backed with over €1 billion in funding – to support foundational technologies for IFE. As part of this, the IFE Targetry HUB consortium – led by Fraunhofer IAF and Focused Energy GmbH alongside 15 research and industrial partners – was established to develop and scale the production of high-precision targets essential for laser-driven fusion experiments.

In October 2025 the German government launched its ‘Fusion Action Plan’[ 50], a strategy to accelerate commercial fusion deployment. With this new plan, Germany is shifting from a focus on basic research to a more industry-driven approach to lead globally in building the world’s first fusion power plant. An international review panel, led by Professor Constantin Haefner, also issued a ‘Memorandum – Laser Inertial Fusion Energy’[ 51].

-

United Kingdom

The UK Inertial Fusion Consortium[ 52] has been established to foster collaboration and coordination within UK inertial fusion research. It is composed of ∼100 members from all UK groups with research interests in inertial fusion. The UPLiFT project (UK Project of Laser Inertial Fusion Technology for energy), composed of a consortium of seven UK institutions led by Robbie Scott at the STFC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory Central Laser Facility, exemplifies this trend. Phase 1 of UPLiFT has a budget of £10 million over 4 years, focusing on IFE laser design, prototype construction, implosion capsule target manufacturing, high-gain physics and extensive development of the hydrodynamic code ‘Odin’.

-

France

A consortium comprising Thales, the CEA, CNRS and the French investment bank (BPI) has established the TARANIS project, funded by the French government, aiming to develop IFE as a commercial energy source. The project has secured Phase 1 funding spanning 36 months from April 2024. Phase 2 is projected to receive 200 million euros in 2027, followed by an additional 600 million euros to establish a demonstration plant. The consortium has also formed a new private entity called GenF.

-

Italy

A key milestone came in 2025, when RSE (Ricerca sul Sistema Energetico) and the National Research Council’s Institute of Optics (CNR-INO) signed a strategic agreement to leverage photonics research infrastructures funded under the National Recovery and Resilience Plan – for advanced high-power laser experimentation in IFE. Italy also plays a prominent role in international fusion diplomacy: it hosted the G7 working group on fusion energy in Frascati in late 2024 and co-organized the inaugural IAEA World Fusion Energy Group ministerial meeting in Rome, signalling its strategic commitment to fostering global collaboration in fusion – including laser-driven approaches.

-

HiPER+

HiPER+ is a pan European consortium aiming to explore the feasibility of IFE and associated technology. Their plan is to build a high gain laser-fusion European programme building on the previous HiPER project[ 53, Reference Le Garrec, Atzeni, Batani, Gizzi, Ribeyre, Schurtz, Schiavi, Ertel, Collier, Edwards, Perlado, Honrubia and Rus54]. In 2023 it published a roadmap for IFE in Europe[ Reference Batani, Colaïtis, Consoli, Danson, Gizzi, Honrubia, Kühl, Le Pape, Miquel, Perlado, Scott, Tatarakis, Tikhonchuk and Volpe55]. A Conceptual Design for a European High Power Laser Fusion Research Facility (HiPER+RF) involving 12 European countries and 146 researchers was recently established within the Eurofusion programme of the EU.

-

Laserlab-Europe AISBL ICF/IFE Expert Group

Membership of the Laserlab-Europe AISBL Expert Group[ 56] is open to all relevant institutes across Europe. There are currently 16 Laserlab-Europe AISBL member institutes participating in the Expert Group. Much of the expertise in this area lies in institutes who are not Laserlab-Europe AISBL members. It was therefore appropriate to open the membership up to other European groups. The aims of the Expert Group are to strengthen the collaboration between research groups in Europe in ICF/IFE and to discuss potential future advances relevant to ICF/IFE.

5 Summary

Advances in ultra-high-power lasers emerge at a great pace. There continues to be scientific drivers such as fundamental physics and basic research, but increasingly there are application-driven motivations. These include laser-driven ICF and medical and industrial applications of high-repetition rate lasers using secondary source generation.

Acknowledgements

The authors would like to thank the following researchers who have significantly contributed to providing detailed information for this editorial: Yutong Li, Institute of Physics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Beijing, China; Jie Zhang, Shanghai Jiao Tong University, Shanghai, China; Jianqiang Zhu and Ping Zhu, Shanghai Institute of Optics and Fine Mechanics, Chinese Academy of Sciences, Shanghai, China; Alessio Morace, Institute of Laser Engineering, Osaka University, Suita, Japan; G. Ravindra Kumar, Tata Institute of Fundamental Research (TIFR), Mumbai, India; Karl Krushelnick and Louise Willingale, Gérard Mourou Center for Ultrafast Optical Science, University of Michigan, Michigan, United States; Jorge Rocca, Colorado State University, Fort Collins, Colorado, United States; Enam Chowdhury, Department of Physics, The Ohio State University, Columbus, United States; Phillip Bradford, STFC Rutherford Appleton Laboratory, Chilton, Didcot, Oxon, UK; Efim Khazanov, Institute of Applied Physics, Russian Academy of Sciences, Nizhny Novgorod, Russia; Dimitri Batani, CELIA, University of Bordeaux, France; Daniele Margarone, ELI Beamlines, Prague; Ioan Dancus, Extreme Light Infrastructure – Nuclear Physics/Horia Hulubei National Institute for Physics and Nuclear Engineering, Romania; Sergey Pikuz, HB11 Energy, Laser Boron Fusion, Sydney, Australia; and Paula Rosen, AWE Nuclear Security Technologies, Aldermaston, Reading, Berkshire, UK.