Psychological attachment to political parties and related identities and values can bias information processing, belief and attitude formation, and group evaluations. Researchers have sought to apply self-affirmation theory (Steele, Reference Steele1988) to this problem. Self-affirmation theory proposes that the overall goal of the self is to protect one’s view of their own self-integrity. In response to threats to this view, people act to restore self-worth through defensive reactions. Alternatively, though, self-worth can be restored through an affirmation of other sources of self-integrity, such as one’s commitment to personally important values. This alternative route to protected self-integrity in the face of threatening information can reduce the need to rely on defensive biases

Several studies report promising results in explicitly partisan contexts (Badea et al. Reference Badea, Tavani, Rubin and Meyer2017; Badea et al. Reference Badea, Binning, Verlhiac and Sherman2018; Binning et al. Reference Binning, Sherman, Cohen and Heitland2010; Binning et al. Reference Binning, Brick, Cohen and Sherman2015; Carnahan et al. Reference Carnahan, Hao, Jiang and Lee2018; Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Sherman, Bastardi, Hsu, McGoey and Ross2007; Van Prooijen and Sparks, Reference van Prooijen and Sparks2014), which they interpret as demonstrating that affirming people’s self-worth in nonpolitical domains might serve to reduce defensive or biased behavior resulting from a perceived risk to one’s identity or self-concept. This general finding – that self-affirmation may ameliorate partisan biases – has since been canonized in reviews (Cohen and Sherman, Reference Cohen and Sherman2014; Sherman and Cohen, Reference Sherman and Cohen2006). While the broader self-affirmation literature in psychology is voluminous, recent studies have called into question the uniformity of its effects (e.g. Reavis et al. Reference Reavis, Ebbs, Onunkwo and Sage2017). Large-scale replications (Hanselman et al. Reference Hanselman, Rozek, Grigg and Borman2017; Protzko and Aronson, Reference Protzko and Aronson2016) suggest that self-affirmation interventions may be “fragile” in some domains of social psychology (but see Borman et al. Reference Borman, Grigg, Rozek, Hanselman and Dewey2018).

In this article, we report a series of studies conducted independently by separate research teams that examine self-affirmation in political contexts. We employ conceptual extensions of prior work applying self-affirmation to politics, rather than close replications. Indeed, our goal was to add more evidence about previous self-affirmation applications’ effectiveness in new, but theoretically related outcomes in politics. In other words, we apply self-affirmation procedures to new political outcomes of interest, and note how and if we depart from any prior work that found significant effects. Our results find that self-affirmation treatments consistently have a little effect across a range of samples and outcome measures (attitudes, factual beliefs, conspiracy beliefs, affective polarization, and evaluations of news sources).Footnote 1 Our hope is that these findings help unite evidence about the study of self-affirmation in political contexts. The studies we report suggest that self-affirmation may have more limited potential in political contexts than previously thought. We hope that future scholars considering using self-affirmation in a political context will consider the evidence about the prior literature we collect here, as well as the variety of interventions and designs we report, and that these results will be useful to future work considering self-affirmation’s potential to reduce partisan biases.

Self-affirmation theory

The theory of self-affirmation is based on the premise that people resist threats to their sense-of-self (e.g. processing counter-attitudinal political information in a biased manner) and that self-integrity can cross domains. In other words, defensive processing in one aspect of a person’s self-concept may be tempered by bolstering another (Steele, Reference Steele1988). According to this account, threats in one domain lose their potency when self-worth is affirmed in other core aspects of one’s self-worth, eliminating the need for ego protection. This elegant theoretical account explains a general problem (biased processing), a mechanism (ego-defending reactions in response to threat), and a potential solution (debiasing by affirming one’s sense-of-self in an unrelated domain). Self-affirmation is canonically induced by way of writing prompts that ask respondents to reflect on important values or characteristics they hold, and describe experiences in which these were exhibited or played an important role in their life.

The core tenet of the self-affirmation approach is that threats to highly central or salient social identities could result in significant “costs,” which promotes defensive responses absent alternative sources of self-integrity (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Sherman, Bastardi, Hsu, McGoey and Ross2007; Sherman and Cohen, Reference Sherman and Cohen2006, p. 218). Previous literature suggests that threats to social identity (such as one’s political affiliation) can be buffered through affirmation, which could lead to less anchoring of group evaluations in one’s self-concept and thereby allowing individuals to evaluate groups independent of their self-evaluation (Cohen et al. Reference Cohen, Aronson and Steele2000). The importance of the domain, or particular social group, is supposed to condition the degree of self-threat and therefore the effectiveness of affirmation (Boninger et al. Reference Boninger, Krosnick and Berent1995). Consequently, any given self-affirmation intervention is not predicted to affect everyone equally. Rather, the effect should be conditional or contingent for those who are being confronted with a threat to their identity. Consequently, each of the studies we present here examines the effect of self-affirmation on the appropriate target population.

An important qualifying condition for the relevance of the self-affirmation approach is to establish that political identities are available to people. Klar (Reference Klar2013) shows that partisan identity can be made salient through mere mention. Asking questions about respondents’ feelings toward their own party and the opposing party, as would commonly occur in a survey about political topics, makes partisan identity salient. Threat is an even more powerful means of raising salience (Klar, Reference Klar2013). For strong partisans or those with strong prior attitudes, many of the experimental setups themselves constitute a threat. For example, those with strong beliefs against the scientific consensus on climate change view contrary information as a threat (Ma et al. Reference Ma, Dixon and Hmielowski2019). Partisans sometimes see the opposing party as a threat to their way of life (Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019). Mason (Reference Mason2018) compellingly shows the centrality of partisanship to identity and the extent to which this generates powerful negative affect towards political outgroups, creating clear opportunities to experience the type of threat that self-affirmation is theorized to protect against. In sum, for strong partisans, questions about political beliefs and feelings toward political groups themselves generate reactance and negative emotion. Under these conditions, former work predicts we should see self-affirmation reduce negative attitudes or group conformity (see, e.g. Van Prooijen and Sparks, Reference van Prooijen and Sparks2014).

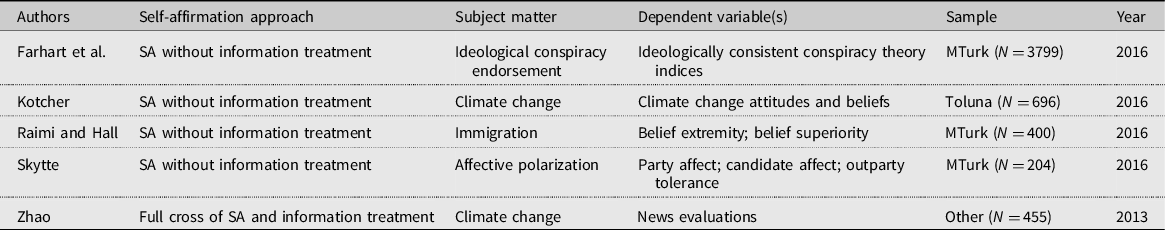

A summary of each study’s approach can be found in Tables 1a and 1b. Further details can be found in the Supplementary Materials.

Table 1a Summary of Unpublished Studies

Table 1b Summary of Studies Published During Project

Selection of studies

The corresponding author solicited “file drawer” studies examining self-affirmation and political behavior, regardless of findings, in March 2018. No studies nominated in the process were excluded. All the authors then shared data allowing for a parallel analysis, as described below. Over the course of the project, three research teams published articles based on the data provided to the corresponding author. (We report all findings from the different research teams using the same analytic strategy. The results we report here for studies that were accepted during this process are substantively consistent with the published version, but the model specifications and point estimates are different.) To aid the reader, we have created separate tables to distinguish between published and unpublished studies.

We report results from a number of studies that examine various outcomes in which political identity may drive biases. Specifically, we look at self-affirmation’s potential to mitigate conspiracy beliefs (e.g. Miller, Saunders, and Farhart, Reference Miller, Saunders and Farhart2016; Oliver and Wood, Reference Oliver and Wood2014), affective polarization (e.g. Iyengar et al. Reference Iyengar, Lelkes, Levendusky, Malhotra and Westwood2019; Mason, Reference Mason2018), belief superiority (e.g. Saucier and Webster, Reference Saucier and Webster2010), news evaluations (e.g. Pingree et al. Reference Pingree, Brossard and McLeod2014), and various forms of party-aligned factual beliefs (e.g. Kahan and Braman, Reference Kahan and Braman2006; Taber and Lodge, Reference Taber and Lodge2006).

Analytic approach

Social psychology experiments that examine the role that self-affirmation may have in reducing bias or extremity typically fall into three types. The first type of study looks at the effect of self-affirmation for relevant versus nonrelevant groups (Binning et al. Reference Binning, Sherman, Cohen and Heitland2010; Correll et al. Reference Correll, Spencer and Zanna2004; Harris and Napper, Reference Harris and Napper2005; Sherman et al. Reference Sherman, Nelson and Steele2000; Van Koningsbruggen et al. Reference Van Koningsbruggen, Das and Roskos-Ewoldsen2009). For example, a message detailing coffee’s health effects may be shown to drinkers and nondrinkers. A typical study would randomly assign subjects to a self-affirmation task (vs. a placebo task), and then show all participants the same stimulus. Analysis would then focus on the effects of self-affirmation for relevant versus nonrelevant groups. The Lyons studies follow this approach.

The second type of study examines the effect of self-affirmation on attitudes and extreme beliefs without an information treatment. These studies randomize assignment to a self-affirmation task (vs. a placebo task), and then measure outcomes of interest (e.g. Lehmiller et al. Reference Lehmiller, Law and Tormala2010). While not always framed in this way, from a political science perspective, one can see these studies as assessing whether self-affirmation makes people more amenable to considering counter-attitudinal information already encoded when constructing a survey response, a la Zaller (Reference Zaller1992). The Farhart et. al., Kotcher, Levendusky, Raimi and Hall, and Skytte studies follow this approach.

Finally, some researchers examine how self-affirmation influences information processing in the face of a threat by concurrently manipulating both self-affirmation and information treatments. For example, Reavis et al. (Reference Reavis, Ebbs, Onunkwo and Sage2017) examine how affirmation moderates the effect of a threatening article correcting the MMR autism link (vs. a placebo article) on intent to vaccinate. Some of our studies follow this route (Nyhan and Reifler and Zhao studies).

As a result, we take two approaches to analysis. First, we look at each study as a two-cell experiment in which participants were randomly assigned to self-affirmation or a control treatment. We construct our analyses so that stimuli were either uniform across all participants or absent. While this approach easily incorporates studies that only manipulate self-affirmation, we need to take an extra step to incorporate studies that also manipulate information. When participants were shown one of the two information treatments (Zhao; Nyhan and Reifler Study 3), we split the study into two analyses – one for each information treatment. Thus, the analyses examine the effect of receiving being self-affirmed versus not being self-affirmed for those who received an information treatment. When the control group received no information (Nyhan and Reifler Studies 1 and 2), we only include cells where participants received the information treatment;Footnote 2 again comparing the effect of being self-affirmed versus not being self-affirmed for those who receive an information treatment. (The supplementary analyses include reanalyses of self-affirmation X information full crosses when excluded given the approach above.)

We use OLS regression with robust standard errors to estimate the effect of self-affirmation in each study. In each model, we estimate the effect of the affirmation treatment as an indicator variable, as well as a relevant moderator – such as party identity or strength of partisanship – and the corresponding interaction term identified by the authors. Interaction terms are constructed such that in most cases, they test the effect of self-affirmation in attenuating the effects of partisanship or ideology on a “negative” outcome.Footnote 3 To compare effects directly, we rescale all dependent variables to range from 0 to 1.

Treatment of multiple outcome measures

Some studies collected multiple relevant dependent variables. We deal with this in two ways. In the Kotcher, Skytte, and Zhao analyses, we create a composite item due to high internal consistency among measures, which also reduces measurement error and improves power (Ansolabehere, Rodden, and Snyder, Reference Ansolabehere, Rodden and Snyder2008). In cases where dependent variables are potentially orthogonal to one another, we analyze the effects of the self-affirmation treatment on each dependent variable separately.

Summary of results

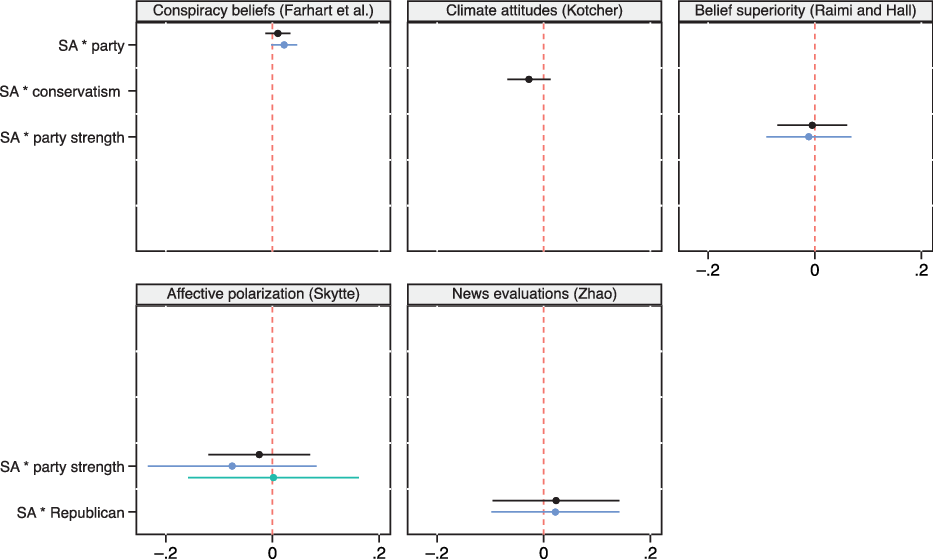

We find no main effects across the studies. However, the theory of self-affirmation expects that effects should be limited to specific (threatened or counter-attitudinal) subgroups. Therefore, we relegate these analyses to the appendix. Our focus now is on the interaction between self-affirmation and an indicator variable identifying the relevant (threatened or counter-attitudinal) subgroups. In Figure 1, we plot regression coefficients for all interactions of the unpublished studies. We present interaction terms across both published and unpublished studies in Tables 2a and 2b.

Table 2a Coefficients for Self-Affirmation X Subgroup Indicator Interaction (unpublished)

Table 2b Coefficients for Self-Affirmation X Subgroup Indicator Interaction (published)

The interaction term of the pooled unpublished studies is b = 0.01, SE = 0.006 (95% CI: −0.004, 0.020) (using a random-effects model and formula provided in Neyeloff et al. Reference Neyeloff, Fuchs and Moreira2012), though we urge caution due to the differing outcome measures across these studies (Carpenter, Reference Carpenter2020). We employ a random-effects model as we allow that the true effect size might differ from study to study, especially given the range of outcome measures. The interaction term when using all of the studies in the present manuscript (including those published) is b = 0.00, SE = 0.004 (95% CI: −0.011, 0.006).

Finally, when reanalyzing the full cross in experiments that included information treatments (Nyhan and Reifler Studies 1–3, and Zhao), we find effects similar to those above (see Tables A8–A9).

Discussion

Can self-affirmation mitigate the psychological effects of partisanship and polarization? This article pools a number of studies undertaken by independent research teams to test this claim. Across studies, contexts, and outcomes of interests, we found little evidence that self-affirmation manipulations have ameliorative effects.

Prior work in the self-affirmation literature reveals that such effects may be contingent on a number of factors (e.g. Borman et al. Reference Borman, Grigg, Rozek, Hanselman and Dewey2018; Ferrer and Cohen, Reference Ferrer and Cohen2019). For this reason, our analyses focus on moderation effects, as self-affirmation effects should be found for those who care more about politics and/or those most threatened by inconvenient claims or by interactions with their political opponents. In this collection of studies, we offer evidence of a number of scenarios in which self-affirmation does not seem to improve outcomes, even among these subgroups.

These findings should be understood in the context of their limitations. The previously unpublished studies we report draw on samples of varying size – though some are large (N = 3,799) others instead rely on sample sizes resembling those in the existing self-affirmation literature, which are underpowered to detect interaction effects (Blake and Gangestad, Reference Blake and Gangestad2020). In other words, these findings should also be considered in the context of prior work that motivated these studies. While all teams were excited by the potential of self-affirmation to address phenomena with strong normative implications – misperceptions, conspiracy belief, and polarization among them – the relatively limited evidentiary value provided by the small sample sizes of and inconsistent methods of prior studies (Table 3) is clearer in hindsight. These prior studies often show contingent effects, though little work has directly replicated the specific contingencies, which vary from study to study. At the same time, the studies presented here may be missing key features necessary for self-affirmation to work. If the work presented here can help clarify the limits of self-affirmation, we believe that would be a valuable contribution.Footnote 4

Table 3 Summary of Prior Studies Testing Self-Affirmation in Political Contexts

Note: Van Prooijen et al. Reference Van Prooijen, Sparks and Jessop2013 find significant, polarizing effects of SA, causing “more constructive pro-environmental motives among participants with positive ecological worldviews but led to less constructive pro-environmental motives among participants with negative ecological worldviews.”

Kotcher (Reference Kotcher2016, p. 68–69) provides a potential empirical explanation for the self-affirmation method’s inconsistent effects:

“self-affirmation not only can activate multiple psychological processes, but […] it may activate both productive and counter-productive processes simultaneously… This suggests that self-affirmation is at the same time both more complex than previously understood […] and less precise as a potential intervention than one might hope.”

Given this richness and complexity, self-affirmation may remain a topic worthy of study for its own sake. At the same time, self-affirmation interventions may not be precise enough to allow researchers to produce normatively desirable outcomes without the danger of concurrently eliciting negative responses. Or, the true effects of self-affirming people may be null or artifactual. Indeed, there is evidence of publication bias in other literatures applying the self-affirmation framework (Weisz et al. Reference Weisz, Lawner, Quinn and Johnson2016; see also Protzko and Aronson, Reference Protzko and Aronson2016). We hope the findings presented here help form a more complete picture of self-affirmation effects on an assortment of identity-driven cognitive and affective phenomena.

With these null results, we also offer a number of research design suggestions for those who wish to continue exploring whether self-affirmation interventions can produce normatively desirable outcomes related to politics. We encourage researchers to use preregistered designs that employ samples large enough to detect the interaction effects that this theory proposes (Blake and Gangestad, Reference Blake and Gangestad2020) or to precisely estimate null results. The results we report rely on conceptual replications. Direct replications (with samples large enough to reliably detect interaction effects) may help identify whether the eight separate research teams whose work is presented here simply erred in how they applied self-affirmation, or whether the approach is less useful than previously thought.

Others might wish to advance work summarized in Tables 1a, 1b and 3 by manipulating identity salience or threat directly. The experimental manipulation of threat may be key to uncovering self-affirmation effects (Ferrer and Cohen, Reference Ferrer and Cohen2019). Indeed, we see this as an unclear proposition given the present state of the literature. While Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Sherman, Bastardi, Hsu, McGoey and Ross2007) manipulate salience, other prior studies (Binning et al., Badea et al., van Prooijen et al., and Carnahan et al.) do not. Moreover, our view is that none of these studies manipulate threat to identity. Consequently, it is hard to establish that any positive effects of a self-affirmation intervention are contingent on salience or threat manipulations. Cohen et al. (Reference Cohen, Sherman, Bastardi, Hsu, McGoey and Ross2007) complicate matters by comparing self-affirmation not to a control, but to a “self-threat” condition where participants report a time they failed to live up to an important value. Experimental paradigms that can reliably induce identity threat may help identify when and where self-affirmation interventions outside the lab may be effective.

Typically, self-affirmation research does not employ manipulation checks for the same reason studies manipulating self-esteem do not: the manipulation check itself may prime the intended state (McQueen and Klein, Reference McQueen and Klein2006). The development of manipulation checks that can evaluate whether a self-affirmation treatment is working as intended (without doubly treating respondents) would be a significant advance. Without manipulation checks, it is hard to know whether it is one’s theory that has failed, or simply one’s procedures that have failed (though see Fayant et al. Reference Fayant, Sigall, Lemonnier, Retsin and Alexopoulos2017 and Hauser et al. Reference Hauser, Ellsworth and Gonzalez2018 on the limitations of manipulation checks more generally).

Conclusion

In this paper, we present a number of studies that attempted to apply the self-affirmation paradigm to political topics. We bring together the work of 8 separate research teams who conducted 11 separate experiments. These different research teams were all motivated by the promising results of studies presented in Table 3 to use self-affirmation as a tool to, for lack a better word, improve politics in some way. Unfortunately, self-affirmation did not generate results consistent with the theory in any of the 11 different experiments.

Supplementary Material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit https://doi.org/10.1017/XPS.2020.46.