Elite interviewing has long been a valuable tool in political science, offering unique insights into political dynamics and providing rich, reliable data for understanding how politics operates. Since Fenno’s (Reference Fenno1978) landmark study, demonstrating how members of Congress engage with constituents and showing that elites are both accessible and insightful sources of knowledge, elite interviewing has become a cornerstone method in the field. This paper examines how elite interviewing is currently practiced and evaluates the extent to which researchers adhere to established reporting standards. Although several studies have explored elite interviewing (see Ellinas Reference Ellinas2023; Markiewicz Reference Markiewicz2024; Ntienjom Mbohou and Tomkinson Reference Mbohou, Félix and Tomkinson2022), the transparency of reporting—particularly how methodological decisions are documented—has received comparatively less attention. While theoretical frameworks and best-practice guidelines exist (Bleich and Pekkanen Reference Bleich, Pekkanen and Mosley2013; Kapiszewski and Karcher Reference Kapiszewski and Karcher2021b), we lack systematic and empirical assessments of how these standards are applied in published research. To address this gap, I draw on an original dataset of all journal articles published between 2000 and 2023 that employed elite interviewing in major political science journals. This study analyzes how elite interviewing is used in practice and how reporting standards have evolved over time.

Defining who qualifies as an “elite” remains a complex challenge in political science, as the term itself is elusive and context dependent. For the purposes of this study, I adopt a minimal definition of elites, characterizing them as “a group of individuals who hold or have held a privileged position in society and, as such, are likely to have had more influence on political outcomes than general members of the public” (Richards Reference Richards1996, 199). Despite elite interviewing’s central role in theory development and empirical research (Berry Reference Berry2002; Leech Reference Leech2002), we still know surprisingly little about who uses this method, in what regional contexts, and for what substantive topics. Are elite interviews predominantly used by comparativists, international relations scholars, or Americanists? What are the prevailing practices around transparency, sampling, and data sharing? And what formats are used to structure and report these methods?

My analysis finds that reporting practices in elite interviewing are often inconsistent. Many articles omit essential information about the identities of interviewees, recruitment strategies, and sampling decisions. However, when articles include supplementary materials, especially appendices, the quality and transparency of reporting improves significantly. These materials often detail ethical procedures, recruitment strategies, researcher reflexivity, and issues related to anonymity and data sharing. This article argues that enhancing reporting practices not only strengthens the credibility and rigor of elite interviewing but also offers clearer guidance for future scholars engaging with this method.

Elite interviews can strengthen political science research by diversifying methodological approaches, improving data quality, and enabling triangulation for more robust descriptive and causal analysis. However, to fully realize these benefits, researchers must provide clear information about their interview methodology, sampling strategies, and overall research design. This transparency allows readers to evaluate the credibility of the findings and the strength of the inferences. At the same time, elite interviewing presents unique challenges, such as defining who qualifies as an elite, selecting appropriate participants, and managing potential biases tied to institutional roles or personal agendas. Transparent reporting of how interviews are conducted and how such challenges are addressed is essential to mitigate these issues.

While promoting best practices in reporting—such as comprehensive documentation and transparency—is essential, we must also avoid overburdening researchers with excessively detailed requirements, particularly those with limited resources or under the pressure of rapid publication timelines (Closa Reference Closa2021). Thus, it is important to differentiate between conducting research in accordance with ethical standards and reporting the details of that research. Scholars routinely meet the ethical guidelines set by institutional review boards (IRBs) and publish their findings in reputable journals after thorough peer review. The issue lies not in the research itself, but in the varying levels of detail provided in the reporting of that research. Striking the right balance in reporting is crucial for advancing the field while respecting researchers’ time and resources.

This article is structured as follows. In the next section, I discuss reporting practices in elite interviewing, providing insights into areas for improvement in transparency and ethical rigor. Then I offer a detailed description of the dataset. Later, I will examine trends in elite interviews within the discipline, showing that it is a common tool across various substantive areas of political science research, but especially prevalent in comparative politics (hereafter CP). I then demonstrate that while there is significant room for improvement in current reporting practices, a promising trend has emerged in recent years. This trend reflects greater attention to ethical issues and increased transparency in the conduct of interviews, particularly through supplementary information. In the final section, I conclude by offering some practical solutions, recognizing the limitations of this analysis, and identifying ways forward. Overall, this article aims to contribute to ongoing qualitative and mixed-methods research efforts to improve reporting practices (for instance, Bleich and Pekkanen Reference Bleich, Pekkanen and Mosley2013; Kapiszewski and Karcher Reference Kapiszewski and Karcher2021b).

A Case for Reporting Practices in Elite Interviewing

Political scientists study a wide range of elites—tribal leaders, guerrilla commanders, lobbyists, representatives of nonstate organizations, rank-and-file parliamentary representatives, court judges, and heads of government—who all play pivotal roles in the political arena and provide key insights into the dynamics of politics. To understand these actors and their influence, we often turn to elite interviewing, which allows us to gather information directly from the individuals driving political action. Interviewing elites offers unique access to the inner workings of political institutions, such as the US Supreme Court (Clark Reference Clark2010), interest groups (Nownes Reference Nownes2006), the motivations and ambitions of political actors (Beckmann Reference Beckmann2010), the knowledge-building process of journalists and public opinion researchers (Cramer and Toff Reference Cramer and Toff2017), and internal deliberations shaping policy outcomes that are not available in public records (Carnegie and Carson Reference Carnegie and Carson2020).

Yet the value of insights gained from elite interviews and any interview-based research is only as strong as the transparency with which the research is reported. These practices ensure that readers can critically evaluate the inferences drawn from the interview data. Following Bleich and Pekkanen (Reference Bleich, Pekkanen and Mosley2013), I argue that transparency in how we identify, select, and interview respondents is essential for assessing the reliability and validity of our findings. Ongoing discussions in the qualitative and mixed-methods community note that the iterative process between data collection and analysis, particularly in qualitative interviewing, creates fragile conditions for assessing the data produced (Bleich and Pekkanen Reference Bleich, Pekkanen and Mosley2013; Small and Calarco Reference Small and Calarco2022). Because the researcher generates the data and can make “in-the-moment decisions,” it is important to pay close attention to the data generation process and how we report the findings in our writing (Small and Calarco Reference Small and Calarco2022).

Challenges such as securing interview access, establishing rapport, conducting analysis, and maintaining ethics are essential to understanding interview-based research, and therefore require thorough documentation and reflection (Ellinas Reference Ellinas2023). Such documentation not only helps researchers to convey the strength of their work but also enables their audience to assess the quality of the evidence presented. Moreover, better reporting practices benefit the broader field of social science research. Qualitative and mixed-methods research training remains underdeveloped in contemporary graduate programs (particularly in the US), and without proper use and discussion of these practices, we lack the necessary know-how. One unwritten rule of scientific research is that we learn best from reading and mimicking others. If our reporting practices lack certain quality checks, we do an injustice to graduate students and junior faculty who rely on these examples to develop their skills and knowledge.

Existing methodological rigor and transparency debates push qualitative, quantitative, or mixed-methods scholars to be adamant in conducting and disseminating research. Adhering to rigorous methodological standards for interviewing—or any qualitative method—is essential to contribute robustly to political science research (Aberbach and Rockman Reference Aberbach and Rockman2002). These standards include selecting interview subjects carefully, determining appropriate sample sizes, transparently reporting sampling strategies, and clearly documenting the interview process. Researchers are also expected to report how they recruited participants, especially elites; describe the interview format; and address ethical considerations such as anonymity and data sharing, which is often documented in supplementary materials. Given these expectations, I emphasize such practices throughout this article. While these standards are crucial across various research traditions, I recognize that the importance of certain practices may vary depending on epistemological perspectives.

In addition, it should also be noted that the practices we adopt as political science researchers are not independent of those adopted and revered by journals and reviewers. Despite recent efforts by major political science journals to diversify their methodological outlook, a common misconception persists that interview research lacks the rigor and scientific value of quantitative research (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2010).Footnote 1 In part, this is because we lack standards against which we can assess quality in elite interviewing. Sometimes it is possible, ethical, and safe to mimic quantitative research practices like pre-analysis plans, replication files, and data-sharing practices (Bentancur, Rodríguez, and Rosenblatt Reference Bentancur, Rodríguez and Rosenblatt2021; Kapiszewski Reference Kapiszewski, Cyr and Goodman2024).Footnote 2

In other cases, however, mimicking quantitative research is not meaningful or can lead to unethical and dangerous practices for the researcher and human subjects involved. Therefore, treating qualitative research as inferior to quantitative research in reporting practices is misguided. We do have predecessors like Bleich and Pekkanen (Reference Bleich, Pekkanen and Mosley2013) to help us achieve solid transparency in reporting, but there needs to be an established understanding of reporting practices that ensures quality control. Responsibility lies largely with researchers themselves. However, the shortcomings of graduate training, particularly in qualitative methods, and the lack of enforcement by journals and reviewers also contribute to inconsistent reporting practices.Footnote 3

One proposed solution to improve reporting is the inclusion of appendices that provide further details on the design and conduct of elite interviews (Bleich and Pekkanen Reference Bleich, Pekkanen and Mosley2013; Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs, Büthe, Arjona, Arriola, Bellin, Bennett and Björkman2021; Kapiszewski and Karcher Reference Kapiszewski and Karcher2021b; Small and Calarco Reference Small and Calarco2022). For example, Bleich and Pekkanen (Reference Bleich, Pekkanen and Mosley2013) introduced the concept of an “Interview Methods Appendix” as a concrete solution by making the data and methodologies accessible for scrutiny. Appendices enable alternative explanations by allowing others to analyze the data and draw their conclusions. This openness mitigates the risks of cherry picking data to support a particular hypothesis. Additionally, online appendices establish standards that promote the reproducibility of findings by providing detailed documentation of the research process, which others can follow and replicate.Footnote 4

Another approach to improving transparency is archiving interview data in repositories such as the Qualitative Data Repository. When ethically and legally feasible, making interview transcripts, summaries, or coding frameworks available enhances the credibility of research and allows other scholars to engage more deeply with the data. However, archiving qualitative data presents challenges, particularly regarding confidentiality, consent, and the sensitivity of interviews. Researchers must carefully navigate these ethical and logistical concerns while balancing transparency with the protection of their interviewees. Encouraging researchers to adopt these practices—whether through detailed appendices or secure data repositories—can strengthen the field’s methodological rigor while fostering a culture of accountability and knowledge sharing.

While robust reporting practices benefit researchers, readers, and participants by ensuring that data are accessible, verifiable, and ethically handled, they also require careful planning, time, and resources. This is not to diminish their value but to acknowledge that transparency involves a careful balancing act. Therefore, advancing transparency in qualitative research should be seen as an ongoing process—one that thrives on collective support from journals, researchers, and the broader academic community.

The Dataset of Elite Interviewing Practices

Procedures and Coding Criteria

To better understand the use and reporting of elite interviewing, I constructed an original dataset of published peer-reviewed journal articles that use elite interviewing in political science. I used the following inclusion and exclusion criteria. First, I included only articles published in major political science journals, covering general journals and substantive area journals on international relations and CP. Including these substantive area journals is important as they are more likely to publish qualitative research, and scholars in these subfields tend to rely more on interviewing and other qualitative methods compared with publications that showcase novel and advanced quantitative methods in general journals. I excluded books, edited volumes, and research notes for practical reasons. While books and edited volumes certainly feature important qualitative fieldwork, including them would require considerable time and research efforts, making it impractical for this analysis. Within these journals, I focused on articles that used elite interviews as a primary form of interviewing.Footnote 5 I used different metrics to select these political science journals.Footnote 6 This procedure resulted in a sample of 13 journals: American Journal of Political Science, American Political Science Review, British Journal of Political Science, Comparative Political Studies, Comparative Politics, Democratization, International Organization, International Security, International Studies Quarterly, Journal of Peace Research, the Journal of Politics, Political Research Quarterly, and World Politics. Footnote 7

Second, my coverage spans from 2000 to 2023, a period in which the use of qualitative and mixed-methods research enjoyed renewed growth within our discipline (Bennett and Elman Reference Bennett and Elman2007).Footnote 8 I hand-coded each article, recording the journal name, author information, the year of publication, and the subfield of the research topic. In terms of interviewing practices, I coded relevant details on the sampling and recruitment procedures, descriptions of the interview subjects, whether the interviews were anonymized, approval information from an IRB or ethics committee, whether the interviews were conducted in person or online, and geographic coverage. For articles relying on multiple methods, I distinguished whether elite interviews were the primary evidence or complementary to another qualitative or quantitative approach. In most meta-analysis research, researchers often rely on the abstracts of journal articles for data coding. I refrained from relying solely on abstracts to determine the methodological approach and content of articles, as abstracts do not always indicate the method employed. To code the information I listed above, I carefully examined the article in full and, when available, the supplementary information or online appendices.

Elite Interviewing Coverage in Political Science Journals

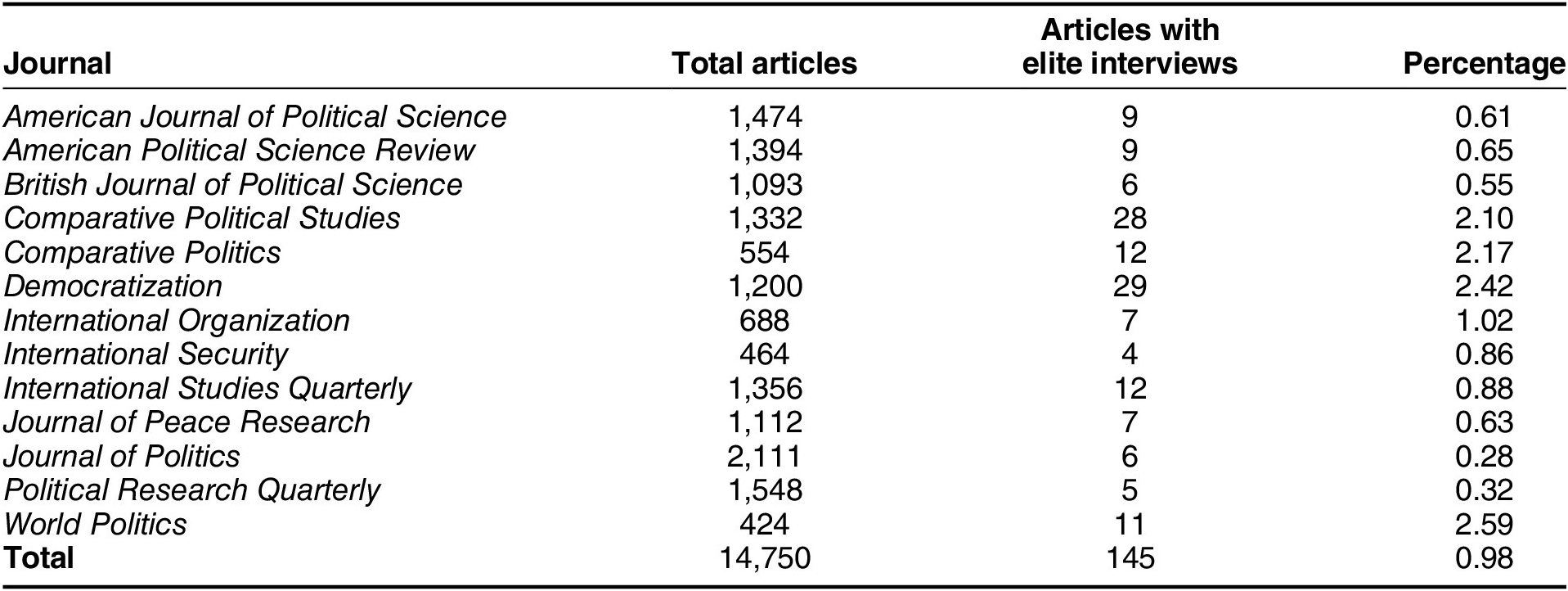

The resulting dataset covers 23 years, 13 journals, and 145 unique articles, of which 91 (around 63%) are single authored, and 54 (around 37%) are coauthored. Out of the 14,750 journal articles published in these journals between 2000 and 2023, around 1% of them use elite interviews. While this might seem like a small proportion, it is significant given that only 12% of all articles in these journals use purely qualitative methods, and just 3% incorporate mixed methods. Although relatively uncommon, elite interviewing plays a critical role in generating context-rich, process-oriented insights that are often inaccessible through other methods. However, its prevalence varies across journals. As shown in table 1, no journal exceeds 3% in its use of elite interviews. World Politics has the highest percentage (2.59%) of articles using elite interviews, whereas the Journal of Politics and Political Research Quarterly have the lowest (0.28% and 0.32%, respectively).

Table 1 Number of Interviews in Journals (2000–23)

The presence of articles that use elite interviews varies substantially across journals, as seen in table 1. Compared with other substantive areas since 2000, CP journals have featured articles that use elite interviews substantially more than other journals. Almost 48% of the articles with elite interviewing have been published by three CP journals: Comparative Political Studies, Comparative Politics, and Democratization. Regarding the three main substantive areas identified by my coding, 71% of the articles were from CP, 22% were from international relations, and 7% were from American politics. In cases where elite interviewing was the sole evidence, all articles came from CP journals.Footnote 9

Descriptive findings from this dataset highlight several interesting insights. As shown in figure 1, the number of articles on elite interviewing published in mainstream political science journals has increased substantially in the past 20 years. While there has been an increase in the use of elite interviews, research relying on elite interviews takes only a small portion of the total articles published in these journals. This disparity suggests that elite interviewing is a specialized yet essential tool for researchers focused on political elites and their influence on key issues.

Figure 1 Distribution of Articles Using Elite Interviews over the Years

Approximately 57% of the articles in my sample employed a qualitative approach, often in combination with other qualitative research designs. The remaining articles adopted a mixed-methods strategy, combining elite interviewing with quantitative methods. Among those using only qualitative methods, 10% relied exclusively on elite interviews. In the mixed-methods group, elite interviewing was the primary qualitative method in another 10% of cases. In 6% of the articles, elite interviews were included but not used as the main form of evidence. In most cases, elite interviews were accompanied by other kinds of qualitative evidence (e.g., case studies, ethnographic work, media analysis, content analysis) and quantitative evidence (e.g., experiments, quasi-experimental settings, panel data analysis, text analysis).Footnote 10

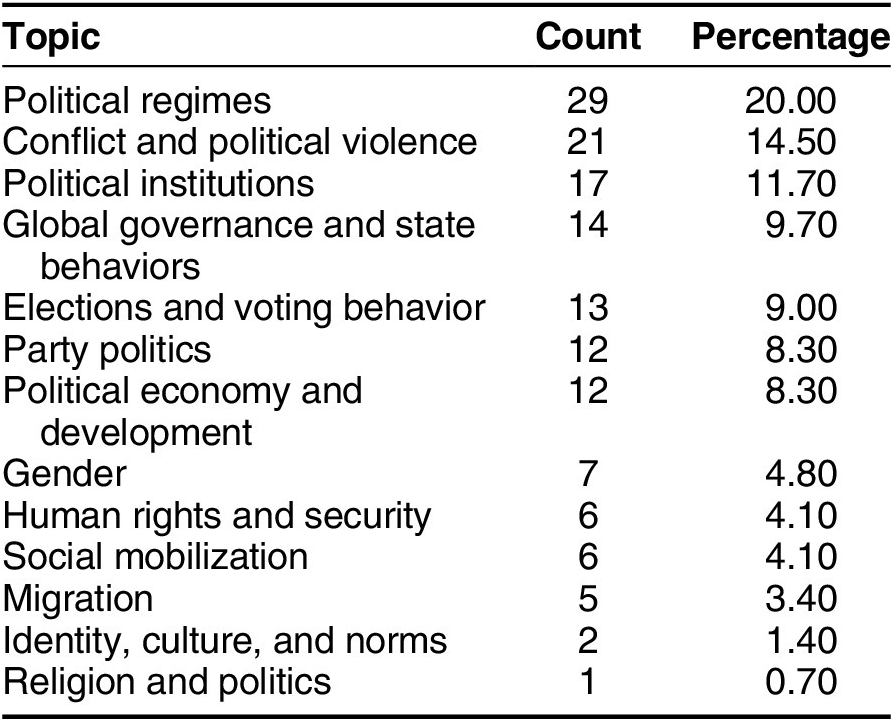

I also explored the main topics covered in scholarship using elite interviews. In identifying these topics, I adapted the categories developed by Cammett and Kendall (Reference Cammett and Kendall2021)Footnote 11 and coded 13 different topics covering different substantive areas of political science research: political regimes, which include regime transitions, autocracies, and democratization; inter- and intrastate conflict and political violence; political institutions; global governance and state behaviors; elections and voting behavior; party politics; political economy and development, which includes research on clientelism and the international economy; gender; human rights and security; social mobilization; migration; identity, culture, and norms; and religion and politics. Table 2 shows the distribution of topics covered in these articles. Research on political regimes and conflict accounts for the largest share, in which political elites, government officials, policy makers, and bureaucrats are interviewed. Research on institutions, global governance, electoral politics, and party politics accounts for 39% of the articles. The rest of the topics have infrequent distribution. The least amount of attention is devoted to religion and identity.

Table 2 Topics Covered in Elite Interviews

Geographically, most elite interviews in this dataset focus on single-country studies (66%). This is not surprising, as conducting interviews requires linguistic skills, deep knowledge of the political context, and significant time and monetary resources, making single-country research more feasible. These interviews also span diverse regions (as shown in figure 2), with nearly half conducted in African and European countries. This concentration reflects regional research priorities and distinctive political contexts. African countries often serve as key sites for studying democratization, governance, and conflict resolution, while European countries attract attention due to their diverse political systems and long-standing traditions of elite engagement.

Figure 2 Regional Distribution of Elite Interviewing

Notes: “Global” refers to cases where the research topic involved several countries in different continents.

Assessment of Reporting Practices in Elite Interview Research

Apart from journal-level trends, I also examined reporting practices in elite interviewing. I evaluated reporting in these articles based on nine key dimensions: sample size, recruitment strategies, modes of conducting interviews, interview structure, sample description, anonymity, ethical considerations, data sharing, and the inclusion of supplementary appendices. These categories were determined using an inductive-deductive approach, ensuring a balance between analytical expectations and the insights gained from this data.

Certain categories, such as sample size, interview structure, and interview modes, represent fundamental aspects of interview research that have garnered significant attention in the literature. These elements are vital in evaluating the rigor and reproducibility of qualitative research involving elites since they represent an “overlap between interpretivist and positivist interview research” (Mosley Reference Mosley and Mosley2013, 11). However, beyond these foundational categories, my analysis also incorporated additional variables, like data sharing, the provision of supplementary information, and the use of appendices based on trends observed within the articles themselves. By documenting how frequently authors disclose critical information such as interview protocols, anonymization practices, and IRB information, this analysis provides a deeper understanding of the current state of transparency in elite interviewing.

Sample Size

Determining an appropriate sample size in interview research is challenging due to ongoing debates about the best conceptual approaches and the lack of clear, practical guidelines. While some researchers implicitly suggest that larger sample sizes can improve research quality (King, Keohane, and Verba Reference King, Keohane and Verba1994), the relationship between sample size and research quality remains contested. Recently, Gonzalez-Ocantos and Masullo (Reference Gonzalez-Ocantos and Masullo2024) offered a crucial critique, arguing that the relevance of the sample, rather than its size, is what truly matters. I do not argue that a specific number of interviews is inherently necessary, minimally acceptable, or better; instead, I emphasize the importance of reporting and justifying the sample size in light of the research question and objectives, regardless of methodological and epistemological traditions. The nature of the topic, the theoretical model, and the research question being explored should guide the determination of the population and, by extension, the sample size.

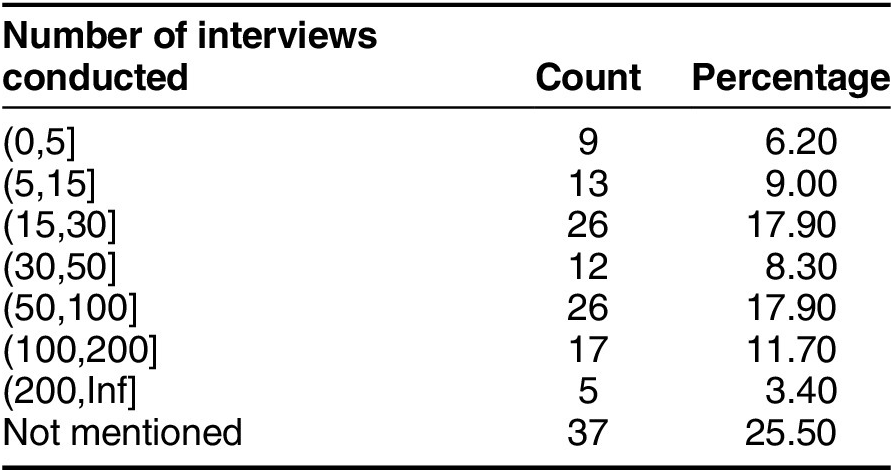

I examined whether and how scholars report their sample size in my analysis. In the articles analyzed, the sample size varies widely, ranging from two to 513 interviewees (see table 3). Yet surprisingly, 37 articles (around 26%) did not disclose their sample size, either in the main text or in the supplementary materials. This omission is particularly concerning as it undermines transparency and hinders readers’ ability to evaluate the rigor and validity of the research. It also reflects broader challenges within the field, where editorial and peer review standards for qualitative methodological reporting may be inconsistently applied. These omissions, spanning from 2000 to 2023, suggest that reporting sample size has not been a consistently adopted practice. This is neither a recent development nor a relic of the past but rather a persistent issue in scholarly reporting.

Table 3 Number of Interviews Conducted

Note: n = 145.

Researchers may omit the sample size for various reasons, including a belief in its irrelevance or a lack of enforcement by journal editors and reviewers. While scholars from a positivist tradition often view sample size as a key indicator of methodological rigor, emphasizing diversity and representativeness, interpretivist researchers tend to prioritize the depth and contextual richness of interviews over numerical thresholds. In some cases, when a study yields rich and meaningful data, disclosing sample size or saturation details may be considered unnecessary (Collett Reference Collett2024). However, as the field increasingly embraces mixed-methods approaches, greater transparency in methodological choices remains essential. Clearly articulating research decisions enables readers to evaluate the credibility of findings and draw their own informed conclusions.

Sampling Strategies

Explicit reporting of sampling strategies and the sample frame enhances research transparency and strengthens readers’ confidence in the findings (Bleich and Pekkanen Reference Bleich, Pekkanen and Mosley2013). In my sample, approximately 71% of the articles did not discuss recruitment procedures in the main text or supplementary materials. This lack of emphasis on recruitment is a significant concern, particularly given that these interviewees were elites, an often hard-to-reach population (Goldstein Reference Goldstein2002). Among those studies that reported this information, half of the articles used purposive sampling (i.e., nonrandom sampling). Specifically, these articles relied on snowball sampling, while other cases employed either other forms of purposive sampling or alternative sampling strategies. In the remaining cases, researchers adapted their sampling approaches to fit their specific needs or the political context. For example, researchers often relied on lists of possible participants, cold calls, and other recruitment strategies to generate a pool of potential interviewees.

In elite interviewing, the inability to speak with certain elites is often as important as the conversations that do occur. Those we cannot interview offer important data points that could reveal more about the research topic and the position of those elites on the topic. Therefore, reporting these limitations is particularly relevant. While most articles offered only brief descriptions of their sampling process, a few provided detailed accounts in supplementary appendices, including how interviewees were contacted, response rates, and reasons for nonresponses. Notably, some studies offered exemplary transparency. For instance, Bush, Donno, and Zetterberg (Reference Bush, Donno and Zetterberg2024) and Mir (Reference Mir2018) explicitly referenced Bleich and Pekkanen’s (Reference Bleich, Pekkanen and Mosley2013) guidelines and thoroughly discussed their sampling frames, nonresponse rates, and the challenges involved in accessing certain elites.

Sample Description

Given the elusiveness of the concept of “elite,” reporting who researchers are trying to interview is crucial, providing clarity and context for the study’s findings. While some scholars argue that sample representativeness is an important aspect of interview research (Leech Reference Leech2002), a detailed description of the interviewees can enhance transparency and improve the accumulation of knowledge for the field (Kertzer and Renshon Reference Kertzer and Renshon2022). From the researcher’s perspective, it aids in the recruitment process and the study’s design, as the type of elite one has access to influences the methodological decisions, such as recruitment strategies.

To assess reporting practices, I focused on two aspects: (1) whether researchers define who they are trying to interview and (2) whether they provide a list of interviewees. The definition of elites remained ambiguous in most of the studies in my sample. In approximately 82% of the articles, no list of interviewees (including details such as occupation or role) was provided. While 7% of the articles failed to describe the elites they interviewed altogether, there was notable diversity in how elites were characterized. In many cases, elites were vaguely referred to as “political elites,” “local elites,” or “politicians.” When identified more specifically, interviewees were typically described by their occupation, including government officials, members of political parties, leaders of nongovernmental organizations, academics, or actors in state and nonstate organizations. This variation underscores the importance of clarifying the intended subjects of elite interviews rather than relying solely on ambiguous labels. Online appendix C reports a word cloud and frequency table showing the diverse ways to report elites in this sample. All data and code used to generate these materials are accessible in the replication files (Tuncel Reference Tuncel2025).

Modes of Conducting Interviews

In-person interviews are no longer considered the gold standard in the field. Advances in videoconferencing, logistical and budgetary considerations, and the potential of digital fieldwork to capture insights that traditional methods may overlook have expanded the range of interview practices (Kapiszewski, MacLean, and Smith Reference Kapiszewski, MacLean, Smith, Cyr and Goodman2024). Despite these developments, in-person interviews remain dominant in the articles analyzed, accounting for 80% of cases. Digital fieldwork methods—though increasingly recognized—were rarely used. Only 7% of studies employed alternative formats, including phone interviews (3%), phone and email (1%), online interviews (2%), and a combination of online and phone interviews (1%). Traditional fieldwork thus continues to be the prevailing mode in this dataset.

Although I expected digital fieldwork practices to dominate in recent years, my analysis did not identify a clear trend solely attributable to technological developments or the COVID-19 pandemic. Over the past few years, there has been a noticeable shift in fieldwork and publishing habits due to the pandemic.Footnote 12 However, the overall impact of these changes was not fully observable in this sample, as it only covers three postpandemic years.Footnote 13 Notably, all articles that solely relied on digital fieldwork practices were from 2023.Footnote 14

Interview Format

Interviews are typically categorized into three main formats: structured, semistructured, and unstructured, each with distinct advantages and limitations (Brinkmann Reference Brinkmann and Leavy2014). Reporting the interview format affects the depth, comparability, and nature of the information collected, ultimately shaping how findings are interpreted. About 40% of the articles explicitly specified whether their interviews were structured, semistructured, unstructured, or had any other format.

Among those that did report this information, semistructured interviews were the most common, appearing in 32% of cases. This format, which balances structure with flexibility, allows researchers to use predefined questions while also probing deeper based on interviewee responses, making it particularly useful across different subfields. In contrast, only 9% of articles employed open-ended, unstructured, or in-depth interviews, which prioritize exploratory insights over standardization. Beyond interview structure, transparency regarding interview questions was even less common. Only 10% of the articles explicitly reported the questions asked during interviews, and in each of these cases the questions were disclosed in the appendix. Notably, nearly all of these articles were published in 2018 or later, indicating a relatively recent trend toward greater methodological transparency. The widespread use of semistructured interviews reflects their adaptability in political research, where balancing consistency with the need for rich, contextual understanding is essential. However, the lack of reporting on interview format in the majority of articles raises concerns about transparency, as this methodological choice significantly impacts how data are gathered and interpreted.

Anonymization of Interviewees

An essential consideration in any research with human subjects is safeguarding respondent confidentiality. In elite interviewing, researchers often face a tension between protecting the anonymity of respondents and providing rich, detailed accounts of elites’ roles (Saunders, Kitzinger, and Kitzinger Reference Saunders, Kitzinger and Kitzinger2015). In 70% of the cases, authors anonymized interviewees by using pseudonyms. In 23% of the cases, elites’ names were revealed. In cases where the elites’ names were used, the authors rarely explain whether they got permission to do so. In one instance, Brooks (Reference Brooks and Mosley2013) justified their approach to using elites’ names on the grounds that that the interviewees were public figures and thus did not require confidentiality. As shown in figure 3, explaining anonymity decisions is not a common practice. Yet having an online appendix specific to elite interviewing correlates positively with explaining the anonymity decision (p < 0.01). In 7% of the cases, both full anonymity and using the names of the interviewees were adopted depending on the author’s ability to get permission from the interviewee. In around 88% of the papers, the authors did not openly discuss why certain decisions were made in terms of anonymity. In the rest of the cases, protecting interviewees from undue harm, interviewees’ requests to remain anonymous, maximizing the participation rate, or IRB protocol decisions were the primary reasons for anonymizing interviews.

Figure 3 Appendix Use, Anonymity Decisions, and Reporting IRB Information over the Years

Ethical Considerations

Protecting human research participants is crucial in elite interviewing (Brooks Reference Brooks and Mosley2013; Jacobs et al. Reference Jacobs, Büthe, Arjona, Arriola, Bellin, Bennett and Björkman2021). To reflect ethical concerns, I mainly looked for information about informed consent (either written or expressed orally) and ethics committees or IRBs. Informed consent was received from the participants in 17% of the cases, and this information is mainly identified in the appendix (around 90%). My analysis reveals that scholarly work in this sample rarely mentioned IRB or equivalent ethics committee information. Only 17% of the studies included IRB details. Moreover, the type of IRB information provided varied greatly; some researchers shared details about the granting institution, while others provided information about IRB approval or exemptions. Interestingly, half of the articles containing IRB information were published in 2023 and the earliest was from 2014, indicating that sharing ethical considerations is a relatively recent trend. As shown in figure 3, online appendices and the reporting of IRB information have become more common in recent years.

Among studies using qualitative methods exclusively, only two articles—one from 2021 and another from 2023—reported IRB or ethics committee approval. In these cases, approval was obtained both from a US-based institution and from institutions in the country where research was conducted. A few articles also noted that IRB details were shared with interviewees. While elite interviews are often exempt from formal IRB review, this does not diminish the importance of ethical transparency. Additionally, my analysis reveals a growing emphasis on ethical and methodological transparency in recent years (see figure 3). Notably, some mixed-methods articles reported IRB details for their quantitative components while omitting ethics information related to their qualitative interviews. Encouragingly, the inclusion of online appendices is positively associated with improved ethics reporting: articles with appendices are significantly more likely to include details on informed consent, IRB approval, or other ethical review processes (p < 0.01).

Data-Sharing Practices

Over the past decade, qualitative and mixed-methods scholars have gained unprecedented opportunities to make their data accessible through online repositories and data-archiving tools (Elman, Kapiszewski, and Vinuela Reference Elman, Kapiszewski and Vinuela2010; Jacobs, Kapiszewski, and Karcher Reference Jacobs, Kapiszewski and Karcher2022; Kapiszewski and Wood Reference Kapiszewski and Wood2022). The “replication crisis,” which has deeply affected disciplines in the social sciences as well as psychology and medicine (Ioannidis Reference Ioannidis2005), has reshaped expectations around replication and reproducibility (King Reference King1995). While data sharing is well established in quantitative political science, its role in qualitative research is more complex due to ethical and practical considerations. Nevertheless, practices such as active citation, in which we can link specific claims in a text to underlying evidence via annotations (Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2010); the Annotation for Transparent Inquiry (ATI) approach, which embeds these annotations into digital publications to provide context and source material (Kapiszewski and Karcher Reference Kapiszewski and Karcher2021a); and repository-based data sharing have emerged as key strategies for increasing transparency in qualitative research.

Despite these advancements, data sharing remains rare in this sample. Notable exceptions include Mangonnet and Murillo (Reference Mangonnet and Murillo2020), who employed active citation by linking to resources on the primary author’s website, and Mayka (Reference Mayka2021), who used the Qualitative Data Repository to provide annotated materials for readers. While such efforts enhance transparency, qualitative researchers must carefully navigate ethical challenges, particularly in fieldwork settings (Fujii Reference Fujii2012). When possible, sharing qualitative data offers multiple benefits: it not only clarifies the research process from design to publication but also aids novice scholars in understanding qualitative methodologies. This is particularly relevant in the US context, where qualitative research education and ethics training often fail to meet current demands (Emmons and Moravcsik Reference Emmons and Moravcsik2020; Knott Reference Knott2019). By making data collection processes more transparent, scholars can contribute to the development of methodological skills among graduate students and early-career researchers.

Data sharing in qualitative research presents significant challenges. Preparing interview transcripts or audio recordings for archiving is time consuming and involves multiple steps, including securing consent, anonymizing sensitive content, and formatting materials for accessibility. These logistical and ethical demands can be especially taxing for solo researchers or those without strong institutional support. Despite these barriers, discussion of data sharing remains rare in the articles I analyzed, and making interview data available continues to be the exception rather than the norm. Only two articles, by Buckley (Reference Buckley2016) and Weeks (Reference Weeks2018), stated in their appendices that transcripts or recordings were available upon request. Three others, by Jones (Reference Jones2019), Mir (Reference Mir2018), and Shesterinina (Reference Shesterinina2016), explicitly noted that sharing was not possible due to IRB restrictions or topic sensitivity. Notably, all five articles were published in recent years, suggesting a gradually emerging attention to the ethics and logistics of qualitative data sharing.

The Use of Online Appendices

The use of methodological appendices in qualitative research is essential for enhancing rigor and transparency (Bleich and Pekkanen Reference Bleich, Pekkanen and Mosley2013). Some journals, including those analyzed in this study, have explicitly encouraged authors to provide supplementary materials detailing their qualitative methods. For instance, the submission guidelines for Comparative Political Studies recommend that researchers include additional documentation, “particularly if they employ qualitative analysis” (Comparative Political Studies 2025). Similarly, in 2022, the editors of American Political Science Review (APSR) acknowledged the constraints imposed by word limits, which had become increasingly problematic with the rise in qualitative submissions. To address this, they proposed using Harvard’s Dataverse for online appendices (APSR Editors 2022). Additionally, APSR editors announced the removal of word-count limits, a change aimed at facilitating the publication of qualitative and mixed-methods research articles, which tend to be longer (APSR Editors 2024).Footnote 15

Given these constraints, qualitative researchers have turned to methodological appendices to provide additional details about the content and conduct of elite interviews. As shown in figure 3, supplementary materials are becoming increasingly common. However, while half of the articles included a quantitative appendix, only 30% had an appendix specifically addressing qualitative elite interviewing. The content of these qualitative appendices varied widely. Some provided only minimal details, while others offered extensive documentation on the elite interviewing approach. One exemplary case is Bush, Donno, and Zetterberg’s (Reference Bush, Donno and Zetterberg2024) appendix, which outlines their compliance with the APSA Council’s Principles and Guidance for Human Subjects Research. Their supplementary materials address key ethical considerations, including power dynamics, consent, deception, harm, trauma, confidentiality, impact, IRB protocols, compensation, and shared responsibility. Additionally, they include details about the interview guide, sample frame, response rate, saturation, interview format, recording method, and a list of interviewees, demonstrating a best-practice model for transparency in qualitative research.

More importantly, the presence of an online appendix was positively and significantly correlated with the disclosure of interviewee lists, informed consent procedures (written or oral), anonymity decisions, and IRB information (p < 0.01). The inclusion of detailed supplementary materials enhances the transparency and reproducibility of qualitative research by providing comprehensive insights into the research process and ethical considerations. By fostering greater trust and credibility, methodological appendices play a crucial role in upholding rigorous academic standards in qualitative political science.

Data Transparency Expectations of Journals

The variation in reporting practices raises an important question: to what extent do journal policies shape transparency in qualitative research? To explore this, I examined the submission guidelines of the journals included in this meta-analysis to determine whether they provide specific instructions on qualitative data reporting and sharing. As of November 2024, nearly all the journals (nine out of 13) had explicit expectations regarding the use of appendices. Additionally, these journals outlined general policies for research involving human subjects, covering key aspects such as informed consent, confidentiality, data access, and adherence to ethical review board requirements.

However, only three of the 13 journals provided specific guidance on handling qualitative data. For instance, the Journal of Peace Research asks authors to include a detailed account of “data collection, ethics, and analysis” within their articles. Furthermore, when legally and ethically feasible, the journal encourages authors to create an online archive of interview transcripts, oral histories, or other hard-to-access materials to enhance research transparency (Journal of Peace Research 2025). The Journal of Politics similarly emphasizes reproducibility and replicability, requiring that both qualitative and quantitative analyses be replicable for a paper to be accepted (Journal of Politics 2025). Comparative Political Studies explicitly instructs authors to provide online-only appendices detailing their qualitative data-gathering process (Comparative Political Studies 2025).Footnote 16 Notably, the few articles in my dataset that explicitly mentioned data availability (Buckley Reference Buckley2016; Weeks Reference Weeks2018) or used active citation (Mangonnet and Murillo Reference Mangonnet and Murillo2020) were published in Comparative Political Studies. This suggests that journal policies may play a role in encouraging transparency, though broader adoption of such guidelines across political science journals remains an ongoing challenge.

Concluding Remarks

This article provides a comprehensive analysis of elite interviewing within the field of political science, shedding light on its prevalence, methodologies, and reporting practices. Elite interviews have long been a vital tool for uncovering insights into political processes, yet their use in academic research has not been systematically explored. Through an original dataset that includes studies published in major political science journals, this article assesses current trends in elite interviewing and examines how well these studies adhere to established reporting standards.

I found that elite interviewing research is commonly featured in subfield journals, often as part of a mixed-methods approach.Footnote 17 While less pronounced in international relations and American politics, CP scholars heavily rely on elite interviewing. Researchers using elite interviews employ various sampling strategies and interview methods, reflecting the diverse definitions of elites within the field. Although only a small subset of articles rely exclusively on elite interviews, which is unlikely to change given broader methodological trends, there are encouraging signs of progress. However, despite its significance, elite interviewing remains an area where methodological reporting practices vary considerably. Expectations across journals for how interview-based research should be presented are not always consistent, and authors may devote limited space to explaining decisions around interview design and implementation. This may reflect, in part, enduring perceptions that place greater value on quantitative rigor, which can shape how qualitative work is evaluated and reported. Although this study does not compare elite interview reporting with other qualitative methods, the lack of consistency across articles raises concerns about the future of transparency in political science (Elman, Kapiszewski, and Lupia Reference Elman, Kapiszewski and Lupia2018). Key details, such as sampling decisions, ethical protocols, and interview procedures, are often underreported, leaving readers unable to fully assess the credibility or replicability of the research.

These issues undermine the value of elite interviewing as a rigorous methodological approach. However, in recent years, a growing number of studies have included detailed online appendices that disclose interview protocols, sampling strategies, and ethical considerations. Articles that include online appendices are significantly more likely to report on anonymity decisions, ethics, and other transparency practices. Some journals have also begun to encourage or require qualitative data supplements, signaling a broader cultural shift toward greater transparency. That said, the field still struggles with consistently reporting core elements of the interview process. The improvements observed are uneven and often depend on individual authors, subfield norms, and journal expectations. Thus, while the overall trend points toward more openness, much work remains to be done.

These findings suggest that better documentation, particularly through supplementary materials, can address concerns over methodological rigor (Bleich and Pekkanen Reference Bleich, Pekkanen and Mosley2013; Kapiszewski and Karcher Reference Kapiszewski and Karcher2021b). More broadly, the increased use of transparency tools and greater attention to ethics reflect a slow but meaningful shift toward higher standards in qualitative research. Still, persistent gaps, such as omitted sample sizes or vague methodological descriptions, highlight the uneven adoption of these evolving norms. Elite interviewing thus offers a valuable insight into how the discipline is navigating growing demands for transparency, accountability, and best practices in qualitative inquiry.

One significant finding from this meta-analysis, which extends beyond elite interviewing research, is that using appendices significantly enhances the depth of information researchers provide. Journal submission guidelines and recent developments, such as ATI, have heightened our awareness of best practices for conveying research findings. Given this evolving landscape, it is clear that the responsibility for robust reporting practices is shared by researchers, journals, and the broader academic community. Drawing from the insights in this meta-analysis, I offer two interlinked practical recommendations aimed at benefiting researchers, reviewers, and journal editors in enhancing reporting practices for both elite interviewing and qualitative research more broadly. The first recommendation is not new but builds on Bleich and Pekkanen’s (Reference Bleich, Pekkanen and Mosley2013) work by advocating the use of appendices to provide detailed information about the interview process. These can improve transparency, enabling readers to assess the quality and depth of the evidence. To support greater consistency across the discipline, I also propose a set of minimum reporting standards that should be included in the appendices of all studies relying on elite interviews: (1) justification for the sample size sampling and recruitment strategies in relation to research goals, (2) the structure and mode of interviews, (3) informed consent procedures and ethical review (e.g., via IRB), and (4) any measures for confidentiality and anonymization. These baseline practices do not require a particular epistemological orientation, yet their inclusion greatly enhances the clarity, rigor, and credibility of qualitative work. While I do not advocate for mandatory detailed appendices, I emphasize that such documentation—particularly when addressing the above elements—can be especially valuable for graduate students, journal reviewers, and scholars new to elite interviewing.

My second suggestion is to adopt ATI and active citation when it is feasible (Kapiszewski and Karcher Reference Kapiszewski and Karcher2021a; Moravcsik Reference Moravcsik2010). These practices go beyond creating appendices by embedding transparency directly into the research process. ATI makes the research process more transparent by allowing researchers to annotate their qualitative data, providing context and explanations.Footnote 18 The active citation system enables readers to verify and understand research findings by linking citations to the underlying data and analysis. These methods can significantly enhance reporting practices by making the research process more accessible and verifiable. The contributions of these practices to elite interview research include enhanced transparency, improved verifiability, and the facilitating of replication. However, implementing ATI and active citation can be resource intensive and require significant effort from researchers. Additionally, there may be ethical and practical constraints on sharing certain types of data, particularly in elite interview research where confidentiality and anonymity are paramount. While these methods significantly enhance transparency and verifiability, balancing these advancements with practical and ethical considerations is crucial.

I also encourage qualitative scholars to engage more actively with ethics committees or IRBs, as doing so can support better planning for transparency and facilitate the inclusion of methodological details in online appendices (Tuncel Reference Tuncel2024). However, IRB approval should be considered a baseline, not a comprehensive ethical safeguard. As Fujii (Reference Fujii2012) emphasizes, ethical responsibilities in qualitative research extend beyond formal review and must be negotiated throughout the research process. This includes treating informed consent as ongoing, being attentive to power dynamics, and responding adaptively to emerging dilemmas in the field. Engaging with ethics committees early in the research process is particularly beneficial, as it encourages thoughtful planning for consent, data storage, and anonymization. These committees can provide a structured approach to anticipating ethical challenges and ensuring responsible research practices. Nevertheless, their effectiveness hinges on a deep understanding of the unique needs of qualitative fieldwork. Researchers should be transparent about the methodological nuances of their projects, such as the iterative nature of semistructured interviews or the challenges of anonymizing elite data, to receive the most relevant and tailored guidance. At the same time, not all scholars have access to robust ethics infrastructure, and committees may lack expertise in qualitative fieldwork. Addressing these institutional and disciplinary gaps is crucial for fostering ethical and transparent research practices.

While this study provides valuable insights into the practice of elite interviewing in political science, it has several limitations. First, the analysis does not compare elite interviewing with other forms of qualitative data collection—such as non-elite interviews, focus groups, or participant observation—which may yield different results and offer additional context for understanding the role of elite interviewing in the field. Many of the recommendations offered here may be broadly applicable to qualitative interviews, yet elite interviewing poses unique challenges, such as restricted access to participants and heightened confidentiality concerns, that warrant special attention in reporting practices and ethical concerns. Unlike non-elite interviews, where rapport and disclosure may be more easily established, elite interviews often require more strategic preparation. These dynamics not only shape the interview process itself but also have important implications for how findings are reported.

Second, my dataset excludes books and regional journals, meaning it misses part of the academic production that incorporates elite interviewing. As such, claiming comprehensive coverage of elite interviewing practices would be premature. These limitations may reduce the generalizability of the findings. However, the scope of this study is broad and, in many ways, the most comprehensive to date, providing valuable insights despite the challenges of covering the entire field within the constraints of time and resources.

Third, the impact of COVID-19 on publishing trends remains inconclusive. While the pandemic likely influenced research practices and publication patterns, the current dataset does not offer enough evidence to draw definitive conclusions regarding its impact on elite interviewing specifically. It is worth noting, however, that the data presented here extend through 2023, a period during which research practices and publication trends appear to have stabilized in a positive direction, as evidenced by the growing adoption of data sharing and appendices. Future research should continue to explore these areas to offer a more comprehensive understanding of the broader context in which elite interviewing operates. Further studies on qualitative interviewing trends should examine how data decisions, topics, and approaches are prioritized in this field. Understanding whether these research programs focus on questions and issues distinct from those commonly featured in mainstream, US-based political science journals will help to determine if unique perspectives and contributions are being overlooked in the broader academic discourse.

Supplementary material

To view supplementary material for this article, please visit http://doi.org/10.1017/S1537592725104040.

Data replication

Data replication sets are available in Harvard Dataverse at: https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/CDXO5O

Acknowledgments

For valuable feedback on previous versions of this article, I express my sincere gratitude to the Emerging Methodologists Workshop and my workshop mentor, Juan Masullo. I am deeply grateful to Diana Kapiszewski and Hillel David Soifer for organizing this workshop and to Erik Bleich for providing extensive feedback. I also thank the participants at the APSA 2024 preconference for their thoughtful contributions, particularly the other presenters Eun-A Park, Irene Morse, Shagun Gupta, Salih Noor, and Ulaș Erdoğdu; mentors Agustina Giraudy, Danielle Lupton, Erik Bleich, Lauren M. MacLean, and Michelle Jurkovich; and participant Marcus Walton. This work benefited from insightful discussions and support provided during these events. Finally, I would like to thank the three anonymous reviewers for their exceptionally detailed engagement with the article.